Submitted:

18 December 2023

Posted:

19 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Iron-Sulfur Clusters as Essential Cofactors in Cells from Bacteria to Human

2. Viral Genome Evolution: Harnessing the Host Machinery and FeS Clusters

3. FeS Clusters in Virally Encoded Proteins of Five Distinct Virus Families

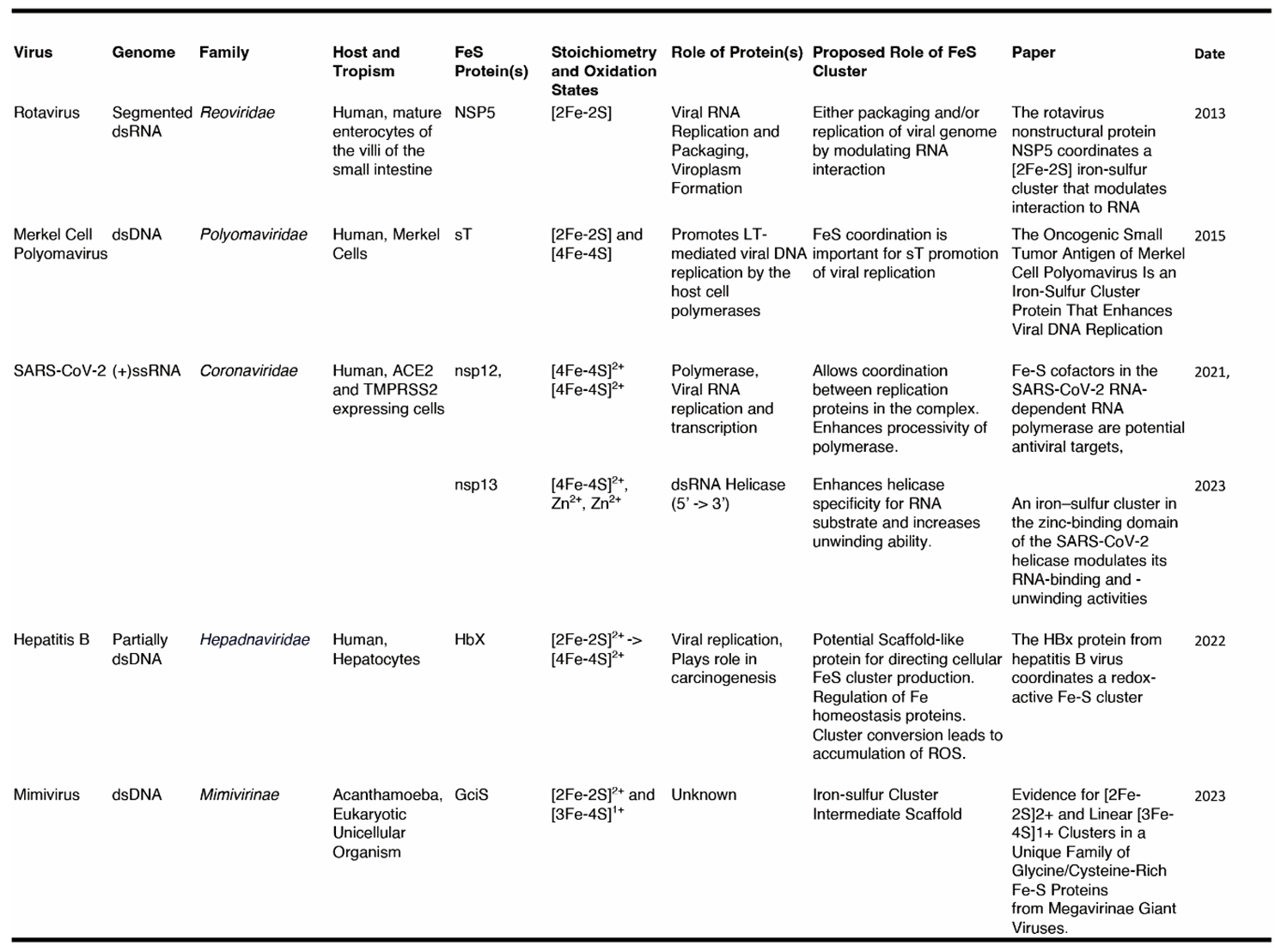

3.1. The Rotavirus Nonstructural Protein 5, NSP5

3.2. The Merkel Cell Polyomavirus small T antigen (sT)

3.3. The SARS-CoV-2 nsp12 and nsp13

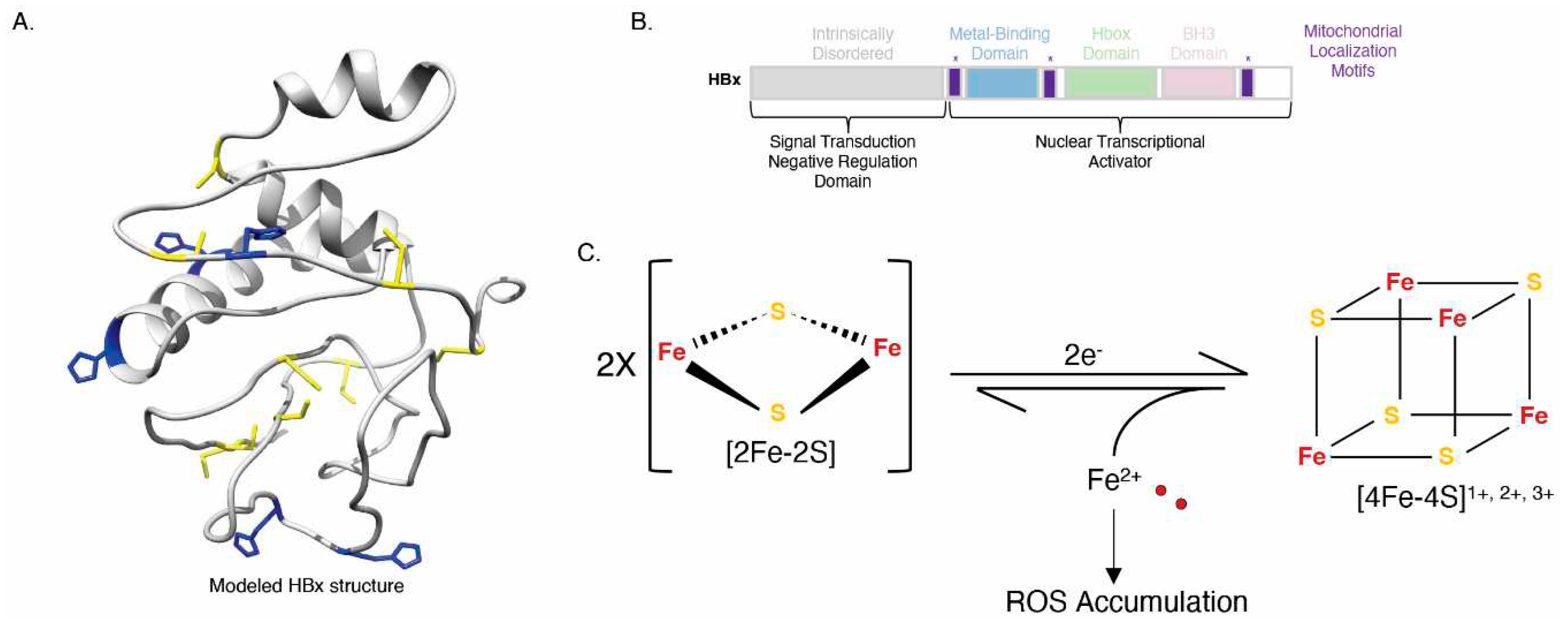

3.4. The Hepatitis B HBx Protein

3.5. The Mimivirus GciS Protein

4. Conclusion and Perspectives

4.1. Drawing Similarities

4.2. So Why Do Viruses Utilize FeS Clusters?

4.3. A Note on Importance

Acknowledgments

References

- Beinert, H.; Holm, R. H.; Munck, E. Iron-Sulfur Clusters: Nature’s Modular, Multipurpose Structures. Science 1997, 277(5326), 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, M.; Sabio, L.; Galvez, N.; Capdevila, M.; Dominguez-Vera, J. M. Iron chemistry at the service of life. IUBMB Life 2017, 69(6), 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartels, P. L.; Stodola, J. L.; Burgers, P. M. J.; Barton, J. K. A Redox Role for the [4Fe4S] Cluster of Yeast DNA Polymerase delta. J Am Chem Soc 2017, 139(50), 18339–18348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, J. K.; Silva, R. M. B.; O'Brien, E. Redox Chemistry in the Genome: Emergence of the [4Fe4S] Cofactor in Repair and Replication. Annu Rev Biochem 2019, 88, 163–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Brien, E.; Holt, M. E.; Thompson, M. K.; Salay, L. E.; Ehlinger, A. C.; Chazin, W. J.; Barton, J. K. The [4Fe4S] cluster of human DNA primase functions as a redox switch using DNA charge transport. Science 2017, 355 (6327). [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M. N.; Ter Beek, J.; Ekanger, L. A.; Johansson, E.; Barton, J. K. The [4Fe4S] Cluster of Yeast DNA Polymerase epsilon Is Redox Active and Can Undergo DNA-Mediated Signaling. J Am Chem Soc 2021, 143(39), 16147–16153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letts, J. A.; Sazanov, L. A. Clarifying the supercomplex: the higher-order organization of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2017, 24(10), 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sickerman, N. S.; Ribbe, M. W.; Hu, Y. Nitrogenase Cofactor Assembly: An Elemental Inventory. Acc Chem Res 2017, 50(11), 2834–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosorev, A. Y. Walking around Ribosomal Small Subunit: A Possible "Tourist Map" for Electron Holes. Molecules 2021, 26 (18).

- Lill, R.; Freibert, S. A. Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Iron-Sulfur Protein Biogenesis. Annu Rev Biochem 2020, 89, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, R. H.; Lo, W. Structural Conversions of Synthetic and Protein-Bound Iron-Sulfur Clusters. Chem Rev 2016, 116(22), 13685–13713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromberg, Y.; Aptekmann, A. A.; Mahlich, Y.; Cook, L.; Senn, S.; Miller, M.; Nanda, V.; Ferreiro, D.; Falkowski, P. Quantifying structural relationships of metal-binding sites suggests origins of biological electron transfer. Science Advances 2022, 8(3984), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imlay, J. A. Iron-sulphur clusters and the problem with oxygen. Mol Microbiol 2006, 59(4), 1073–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, S. R. Defining normoxia, physoxia and hypoxia in tumours-implications for treatment response. Br J Radiol 2014, 87(1035), 20130676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K. A. Angiogenesis. In Encyclopedia of Cell Biology, 2016; pp 102-116.

- Maio, N.; Rouault, T. A. Outlining the Complex Pathway of Mammalian Fe-S Cluster Biogenesis. Trends Biochem Sci 2020, 45(5), 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genova, M. L.; Lenaz, G. Functional role of mitochondrial respiratory supercomplexes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1837(4), 427–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, B. L.; Zahn, K. E.; Hanley, J. P.; Wallace, S. S.; Dragon, J. A.; Doublie, S. Caught in motion: human NTHL1 undergoes interdomain rearrangement necessary for catalysis. Nucleic Acids Res 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maio, N.; Rouault, T. A. Mammalian iron sulfur cluster biogenesis: From assembly to delivery to recipient proteins with a focus on novel targets of the chaperone and co-chaperone proteins. IUBMB Life 2022, 74(7), 684–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciesielski, S. J.; Schilke, B. A.; Osipiuk, J.; Bigelow, L.; Mulligan, R.; Majewska, J.; Joachimiak, A.; Marszalek, J.; Craig, E. A.; Dutkiewicz, R. Interaction of J-protein co-chaperone Jac1 with Fe-S scaffold Isu is indispensable in vivo and conserved in evolution. J Mol Biol 2012, 417 (1-2), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Chakrabbarti, M.; Lindahl, P. A. The utility of Mossbauer spectroscopy in eukaryotic cell biology and animal physiology. In Iron-sulfur clusters in chemistry and Biology, Rouault, T. A., Ed. Walter de Gruyter: Berlin/Boston, 2014; pp 49-71. [CrossRef]

- Maio, N.; Rouault, T. A. Iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis in mammalian cells: New insights into the molecular mechanisms of cluster delivery. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015, 1853(6), 1493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Tong, W.-H.; Hughes, R. M.; Rouault, T. A. Roles of the Mammalian Cytosolic Cysteine Desulfurase, ISCS, and Scaffold Protein, ISCU, in Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2006, 281(18), 12344–12351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, W. H.; Rouault, T. A. Distinct iron-sulfur cluster assembly complexes exist in the cytosol and mitochondria of human cells. EMBO 2000, 19(21), 5692–5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W. H.; Rouault, T. A. Functions of mitochondrial ISCU and cytosolic ISCU in mammalian iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis and iron homeostasis. Cell Metab 2006, 3(3), 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Proteau, A.; Villarroya, M.; Moukadiri, I.; Zhang, L.; Trempe, J. F.; Matte, A.; Armengod, M. E.; Cygler, M. Structural basis for Fe-S cluster assembly and tRNA thiolation mediated by IscS protein-protein interactions. PLoS Biol 2010, 8(4), e1000354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A. C.; Bornhovd, C.; Prokisch, H.; Neupert, W.; Hell, K. The Nfs1 interacting protein Isd11 has an essential role in Fe/S cluster biogenesis in mitochondria. EMBO J 2006, 25(1), 174–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Ghosh, M. C.; Tong, W. H.; Rouault, T. A. Human ISD11 is essential for both iron-sulfur cluster assembly and maintenance of normal cellular iron homeostasis. Hum Mol Genet 2009, 18(16), 3014–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terali, K.; Beavil, R. L.; Pickersgill, R. W.; van der Giezen, M. The effect of the adaptor protein Isd11 on the quaternary structure of the eukaryotic cysteine desulphurase Nfs1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2013, 440(2), 235–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. J.; Frey, A. G.; Palenchar, D. J.; Achar, S.; Bullough, K. Z.; Vashisht, A.; Wohlschlegel, J. A.; Philpott, C. C. A PCBP1-BolA2 chaperone complex delivers iron for cytosolic [2Fe-2S] cluster assembly. Nat Chem Biol 2019, 15(9), 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Bencze, K. Z.; Stemmler, T. L.; Philpott, C. C. A cytosolic iron chaperone that delivers iron to ferritin. Science 2008, 320(5880), 1207–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandal, A.; Ruiz, J. C.; Subramanian, P.; Ghimire-Rijal, S.; Sinnamon, R. A.; Stemmler, T. L.; Bruick, R. K.; Philpott, C. C. Activation of the HIF prolyl hydroxylase by the iron chaperones PCBP1 and PCBP2. Cell Metab 2011, 14(5), 647–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leidgens, S.; Bullough, K. Z.; Shi, H.; Li, F.; Shakoury-Elizeh, M.; Yabe, T.; Subramanian, P.; Hsu, E.; Natarajan, N.; Nandal, A.; Stemmler, T. L.; Philpott, C. C. Each member of the poly-r(C)-binding protein 1 (PCBP) family exhibits iron chaperone activity toward ferritin. J Biol Chem 2013, 288(24), 17791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, A. G.; Nandal, A.; Park, J. H.; Smith, P. M.; Yabe, T.; Ryu, M. S.; Ghosh, M. C.; Lee, J.; Rouault, T. A.; Park, M. H.; Philpott, C. C. Iron chaperones PCBP1 and PCBP2 mediate the metallation of the dinuclear iron enzyme deoxyhypusine hydroxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111(22), 8031–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boniecki, M. T.; Freibert, S. A.; Muhlenhoff, U.; Lill, R.; Cygler, M. Structure and functional dynamics of the mitochondrial Fe/S cluster synthesis complex. Nat Commun 2017, 8(1), 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, K.; Tonelli, M.; Frederick, R. O.; Markley, J. L. Human Mitochondrial Ferredoxin 1 (FDX1) and Ferredoxin 2 (FDX2) Both Bind Cysteine Desulfurase and Donate Electrons for Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biosynthesis. Biochemistry 2017, 56(3), 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandramouli, K.; Unciuleac, M. C.; Naik, S.; Dean, D. R.; Huynh, B. H.; Johnson, M. K. Formation and properties of [4Fe-4S] clusters on the IscU scaffold protein. Biochemistry 2007, 46(23), 6804–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, E. C. M.; Zwang, T. J.; Barton, J. K. The Oxidation State of [4Fe4S] Clusters Modulates the DNA-Binding Affinity of DNA Repair Proteins. J Am Chem Soc 2017, 139(36), 12784–12792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandelia, M. E.; Lanz, N. D.; Booker, S. J.; Krebs, C. Mossbauer spectroscopy of Fe/S proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015, 1853(6), 1395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voisine, C.; Cheng, Y. C.; Ohlson, M.; Schilke, B.; Hoff, K.; Beinert, H.; Marszalek, J.; Craig, E. A. Jac1, a mitochondrial J-type chaperone, is involved in the biogenesis of Fe/S clusters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98(4), 1483–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cupp-Vickery, J. R.; Peterson, J. C.; Ta, D. T.; Vickery, L. E. Crystal structure of the molecular chaperone HscA substrate binding domain complexed with the IscU recognition peptide ELPPVKIHC. J Mol Biol 2004, 342(4), 1265–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maio, N.; Singh, A.; Uhrigshardt, H.; Saxena, N.; Tong, W. H.; Rouault, T. A. Cochaperone binding to LYR motifs confers specificity of iron sulfur cluster delivery. Cell Metab 2014, 19(3), 445–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marszalek, J.; Craig, E. A. Interaction of client-the scaffold on which FeS clusters are build-with J-domain protein Hsc20 and its evolving Hsp70 partners. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 9, 1034453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maio, N.; Kim, K. S.; Singh, A.; Rouault, T. A. A Single Adaptable Cochaperone-Scaffold Complex Delivers Nascent Iron-Sulfur Clusters to Mammalian Respiratory Chain Complexes I-III. Cell Metab 2017, 25 (4), 945-953 e6. [CrossRef]

- Kampinga, H. H.; Craig, E. A. The HSP70 chaperone machinery: J proteins as drivers of functional specificity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010, 11(8), 579–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahi, C.; Craig, E. A. Network of general and specialty J protein chaperones of the yeast cytosol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104(17), 7163–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomi, F.; Iametti, S.; Morleo, A.; Ta, D.; Vickery, L. E. Facilitated transfer of IscU-[2Fe2S] clusters by chaperone-mediated ligand exchange. Biochemistry 2011, 50(44), 9641–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkiewicz, R.; Schilke, B.; Cheng, S.; Knieszner, H.; Craig, E. A.; Marszalek, J. Sequence-specific interaction between mitochondrial Fe-S scaffold protein Isu and Hsp70 Ssq1 is essential for their in vivo function. J Biol Chem 2004, 279(28), 29167–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, K. G.; Cupp-Vickery, J. R.; Vickery, L. E. Contributions of the LPPVK motif of the iron-sulfur template protein IscU to interactions with the Hsc66-Hsc20 chaperone system. J Biol Chem 2003, 278(39), 37582–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouault, T. A. Mammalian iron-sulphur proteins: novel insights into biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2015, 16(1), 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gari, K.; Ortiz, A. M. L.; Borel, V.; Flynn, H.; Skehel, J. M.; Boulton, S. J. MMS19 links cytoplasmic iron-sulfur cluster assembly to DNA metabolism. Science 2012, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stehling, O.; Vashisht, A. A.; Mascarenhas, J.; Jonsson, Z. O.; Sharma, T.; Netz, D. J.; Pierik, A. J.; Wohlschlegel, J. A.; Lill, R. MMS19 assembles iron-sulfur proteins required for DNA metabolism and genomic integrity. Science 2012, 337(6091), 195–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K. S.; Maio, N.; Singh, A.; Rouault, T. A. Cytosolic HSC20 integrates de novo iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis with the CIAO1-mediated transfer to recipients. Hum Mol Genet 2018, 27(5), 837–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassube, S. A.; Thoma, N. H. Structural insights into Fe-S protein biogenesis by the CIA targeting complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2020, 27(8), 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, H.; Rouault, T. A. Human iron-sulfur cluster assembly, cellular iron homeostasis, and disease. Biochemistry 2010, 49(24), 4945–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crick, F. H. C.; Watson, J. D. Structure of Small Viruses. Nature 1956, 177, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, Y. I.; Kazlauskas, D.; Iranzo, J.; Lucia-Sanz, A.; Kuhn, J. H.; Krupovic, M.; Dolja, V. V.; Koonin, E. V. Origins and Evolution of the Global RNA Virome. mBio 2018, 9 (6). [CrossRef]

- Twarock, R.; Luque, A. Structural puzzles in virology solved with an overarching icosahedral design principle. Nat Commun 2019, 10(1), 4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colson, P.; De Lamballerie, X.; Yutin, N.; Asgari, S.; Bigot, Y.; Bideshi, D. K.; Cheng, X. W.; Federici, B. A.; Van Etten, J. L.; Koonin, E. V.; La Scola, B.; Raoult, D. "Megavirales", a proposed new order for eukaryotic nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses. Arch Virol 2013, 158(12), 2517–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raoult, D.; Audic, S.; Robert, C.; Abergel, C.; Renesto, P.; Ogata, H.; Scola, B.; Suzan, M.; Claverie, J. The 1.2-Mb Genome Sequence of Mimivirus. Science 2004, 306, 1344 - 1350. [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Charpilienne, A.; Parent, A.; Boussac, A.; D'Autreaux, B.; Poupon, J.; Poncet, D. The rotavirus nonstructural protein NSP5 coordinates a [2Fe-2S] iron-sulfur cluster that modulates interaction to RNA. FASEB J 2013, 27(3), 1074–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozsari, T.; Bora, G.; Kaya, B.; Yakut, K. The Prevalence of Rotavirus and Adenovirus in the Childhood Gastroenteritis. Jundishapur J Microbiol 2016, 9(6), e34867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papa, G.; Borodavka, A.; Desselberger, U. Viroplasms: Assembly and Functions of Rotavirus Replication Factories. Viruses 2021, 13 (7). [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Ouldali, M.; Menetrey, J.; Poncet, D. Structural organisation of the rotavirus nonstructural protein NSP5. J Mol Biol 2011, 413(1), 209–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbretti, E.; Afrikanova, I.; Vascotto, F.; Burrone, O. R. Two non-structural rotavirus proteins, NSP2 and NSP5, form viroplasm-like structures in vivo. Journal of General Virology 1999, 80, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, G.; Venditti, L.; Arnoldi, F.; Schraner, E. M.; Potgieter, C.; Borodavka, A.; Eichwald, C.; Burrone, O. R. Recombinant Rotaviruses Rescued by Reverse Genetics Reveal the Role of NSP5 Hyperphosphorylation in the Assembly of Viral Factories. J Virol 2019, 94 (1). [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S. H.; Wang, R.; Nakamaru-Ogiso, E.; Knight, S. A.; Buck, C. B.; You, J. The Oncogenic Small Tumor Antigen of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Is an Iron-Sulfur Cluster Protein That Enhances Viral DNA Replication. J Virol 2016, 90(3), 1544–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendzicki, J. A.; Moore, P. S.; Chang, Y. Large T and small T antigens of Merkel cell polyomavirus. Curr Opin Virol 2015, 11, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwun, H. J.; Guastafierro, A.; Shuda, M.; Meinke, G.; Bohm, A.; Moore, P. S.; Chang, Y. The minimum replication origin of merkel cell polyomavirus has a unique large T-antigen loading architecture and requires small T-antigen expression for optimal replication. J Virol 2009, 83(23), 12118–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J. C.; Stang, A.; DeCaprio, J. A.; Cerroni, L.; Lebbe, C.; Veness, M.; Nghiem, P. Merkel cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017, 3, 17077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Shuda, M.; Chang, Y.; Moore, P. S. Clonal Integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science 2008, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapchak, K.; Yagobian, S. D.; Moore, J.; Khattri, M.; Shuda, M. Merkel cell polyomavirus small T antigen is a viral transcription activator that is essential for viral genome maintenance. PLoS Pathog 2022, 18(12), e1011039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwun, H. J.; Shuda, M.; Feng, H.; Camacho, C. J.; Moore, P. S.; Chang, Y. Merkel cell polyomavirus small T antigen controls viral replication and oncoprotein expression by targeting the cellular ubiquitin ligase SCFFbw7. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14(2), 125–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, N.; Lafont, B. A. P.; Sil, D.; Li, Y.; Bollinger, J. M., Jr.; Krebs, C.; Pierson, T. C.; Linehan, W. M.; Rouault, T. A. Fe-S cofactors in the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase are potential antiviral targets. Science 2021, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, N.; Raza, M. K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D.; Bollinger, J. M., Jr.; Krebs, C.; Rouault, T. A. An iron-sulfur cluster in zinc-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 helicase modulates its RNA binding and unwinding activities. PNAS 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, B.; Campbell, E. A.; Darst, S. A. CoV-er all the bases: Structural perspectives of SARS-CoV-2 RNA synthesis. Enzymes 2021, 49, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, P. C.; Lau, S. K.; Huang, Y.; Yuen, K. Y. Coronavirus diversity, phylogeny and interspecies jumping. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2009, 234(10), 1117–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, F.; Khan, K. S.; Le, T. K.; Paris, C.; Demirbag, S.; Barfuss, P.; Rocchi, P.; Ng, W. L. Coronavirus RNA Proofreading: Molecular Basis and Therapeutic Targeting. Mol Cell 2020, 79(5), 710–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribble, J.; Stevens, L. J.; Agostini, M. L.; Anderson-Daniels, J.; Chappell, J. D.; Lu, X.; Pruijssers, A. J.; Routh, A. L.; Denison, M. R. The coronavirus proofreading exoribonuclease mediates extensive viral recombination. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17(1), e1009226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brant, A. C.; Tian, W.; Majerciak, V.; Yang, W.; Zheng, Z. M. SARS-CoV-2: from its discovery to genome structure, transcription, and replication. Cell Biosci 2021, 11(1), 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Ge, J.; Huang, Y. C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, T.; Gao, S.; Zhang, R.; Huang, Y. Y.; Guddat, L. W.; Gao, Y.; Rao, Z.; Lou, Z. Coupling of N7-methyltransferase and 3'-5' exoribonuclease with SARS-CoV-2 polymerase reveals mechanisms for capping and proofreading. Cell 2021, 184 (13), 3474-3485 e11.

- Dos Ramos, F.; Carrasco, M.; Doyle, T.; Brierley, I. Programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting in the SARS coronavirus. Biochem Soc Trans 2004, 32, 1081–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, V.; Ivanov, K. A.; Putics, A.; Hertzig, T.; Schelle, B.; Bayer, S.; Weissbrich, B.; Snijder, E. J.; Rabenau, H.; Doerr, H. W.; Gorbalenya, A. E.; Ziebuhr, J. Mechanisms and enzymes involved in SARS coronavirus genome expression. J Gen Virol 2003, 84 (Pt 9), 2305–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillen, H. S.; Kokic, G.; Farnung, L.; Dienemann, C.; Tegunov, D.; Cramer, P. Structure of replicating SARS-CoV-2 polymerase. Nature 2020, 584(7819), 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, K.; Lokugamage, K. G.; Makino, S. Viral and Cellular mRNA Translation in Coronavirus-Infected Cells. Adv Virus Res 2016, 96, 165–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchdoerfer, R. N.; Ward, A. B. Structure of the SARS-CoV nsp12 polymerase bound to nsp7 and nsp8 co-factors. Nat Commun 2019, 10(1), 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saikrishnan, K.; Powell, B.; Cook, N. J.; Webb, M. R.; Wigley, D. B. Mechanistic basis of 5'-3' translocation in SF1B helicases. Cell 2009, 137(5), 849–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Ge, J.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, T.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Gao, S.; Li, M.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guddat, L. W.; Wang, Q.; Rao, Z.; Lou, Z. Cryo-EM Structure of an Extended SARS-CoV-2 Replication and Transcription Complex Reveals an Intermediate State in Cap Synthesis. Cell 2021, 184 (1), 184-193 e10.

- Chen, J.; Wang, Q.; Malone, B.; Llewellyn, E.; Pechersky, Y.; Maruthi, K.; Eng, E. T.; Perry, J. K.; Campbell, E. A.; Shaw, D. E.; Darst, S. A. Ensemble cryo-EM reveals conformational states of the nsp13 helicase in the SARS-CoV-2 helicase replication-transcription complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2022, 29(3), 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, M. R.; Dillingham, M. S.; Wigley, D. B. Structure and mechanism of helicases and nucleic acid translocases. Annu Rev Biochem 2007, 76, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mickolajczyk, K. J.; Shelton, P. M. M.; Grasso, M.; Cao, X.; Warrington, S. E.; Aher, A.; Liu, S.; Kapoor, T. M. Force-dependent stimulation of RNA unwinding by SARS-CoV-2 nsp13 helicase. Biophys J 2021, 120(6), 1020–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K. J.; Jeong, S.; Kang, D. Y.; Sp, N.; Yang, Y. M.; Kim, D. E. A high ATP concentration enhances the cooperative translocation of the SARS coronavirus helicase nsP13 in the unwinding of duplex RNA. Sci Rep 2020, 10(1), 4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, J. A.; Loftus, L. N.; Jones, M. P., 3rd; Lee, R. A.; Haren, C. E.; Dumm, A. J.; Brosh, R. M., Jr. Biochemical analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Nsp13 helicase implicated in COVID-19 and factors that regulate its catalytic functions. J Biol Chem 2023, 299(3), 102980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimberg, G. D.; Michalek, J. L.; Oluyadi, A. A.; Rodrigues, A. V.; Zucconi, B. E.; Neu, H. M.; Ghosh, S.; Sureschandra, K.; Wilson, G. M.; Stemmler, T. L.; Michel, S. L. Cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor 30: An RNA-binding zinc-finger protein with an unexpected 2Fe-2S cluster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113(17), 4700–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.; Murdoch, C. C.; Edmonds, K. A.; Jordan, M. R.; Monteith, A. J.; Perera, Y. R.; Rodriguez Nassif, A. M.; Petoletti, A. M.; Beavers, W. N.; Munneke, M. J.; Drury, S. L.; Krystofiak, E. S.; Thalluri, K.; Wu, H.; Kruse, A. R. S.; DiMarchi, R. D.; Caprioli, R. M.; Spraggins, J. M.; Chazin, W. J.; Giedroc, D. P.; Skaar, E. P. Zn-regulated GTPase metalloprotein activator 1 modulates vertebrate zinc homeostasis. Cell 2022, 185 (12), 2148-2163 e27. [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, A.; Stein, M. Distal [FeS]-Cluster Coordination in [NiFe]-Hydrogenase Facilitates Intermolecular Electron Transfer. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18 (1). [CrossRef]

- Bak, D. W.; Elliott, S. J. Alternative FeS cluster ligands: tuning redox potentials and chemistry. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2014, 19, 50–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, G. S.; Thompson, A. J. Viral hepatitis B: clinical and epidemiological characteristics. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2014, 4(12), a024935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schollmeier, A.; Glitscher, M.; Hildt, E. Relevance of HBx for Hepatitis B Virus-Associated Pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24 (5). [CrossRef]

- Brechot, C. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Hepatology 1987, 4, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H. Y.; Guy, J. S.; Yoo, D.; Vlasak, R.; Urbach, E.; Brian, D. A. Common RNA replication signals exist among group 2 coronaviruses: evidence for in vivo recombination between animal and human coronavirus molecules. Virology 2003, 315(1), 174–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, S. G.; Milich, D. R.; McLachlan, A. Hepatitis B virus core antigen has two nuclear localization sequences in the Arginine-rich carboxyl terminus. J Virol 1991, 65, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukuda, S.; Watashi, K. Hepatitis B virus biology and life cycle. Antiviral Res 2020, 182, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Ploss, A. Hepatitis B virus cccDNA is formed through distinct repair processes of each strand. Nat Commun 2021, 12(1), 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dane, D. S.; H. C. C., Virus-like particles in serum of patients with Australia-antigen associated hepatitis. The Lancet 1970, 295(7649), 649–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hemert, F. J.; van de Klundert, M. A.; Lukashov, V. V.; Kootstra, N. A.; Berkhout, B.; Zaaijer, H. L. Protein X of hepatitis B virus: origin and structure similarity with the central domain of DNA glycosylase. PLoS One 2011, 6(8), e23392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, J. M.; Lim, S. O.; Oh, S. J.; Yoon, S. M.; Seong, J. K.; Jung, G. HBx modulates iron regulatory protein 1-mediated iron metabolism via reactive oxygen species. Virus Res 2008, 133(2), 167–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettany, A. J.; Eisenstein, R. S.; Munro, H. N. Mutagenesis of the iron-regulatory element further defines a role for RNA secondary structure in the regulation of ferritin and transferrin receptor expression. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1992, 267(23), 16531–16537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.; Munro, H. N. Iron regulates ferritin mRNA translation through a segment of its 5’ untranslated region. PNAS 1987, 84, 8478–8482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouault, T. A. The role of iron regulatory proteins in mammalian iron homeostasis and disease. Nat Chem Biol 2006, 2(8), 406–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, C.; Langton, M.; Chen, J.; Pandelia, M. E. The HBx protein from Hepatitis B Virus coordinates a redox-active Fe-S cluster. J Biol Chem 2022, 101698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monttinen, H. A. M.; Bicep, C.; Williams, T. A.; Hirt, R. P. The genomes of nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses: viral evolution writ large. Microb Genom 2021, 7 (9). [CrossRef]

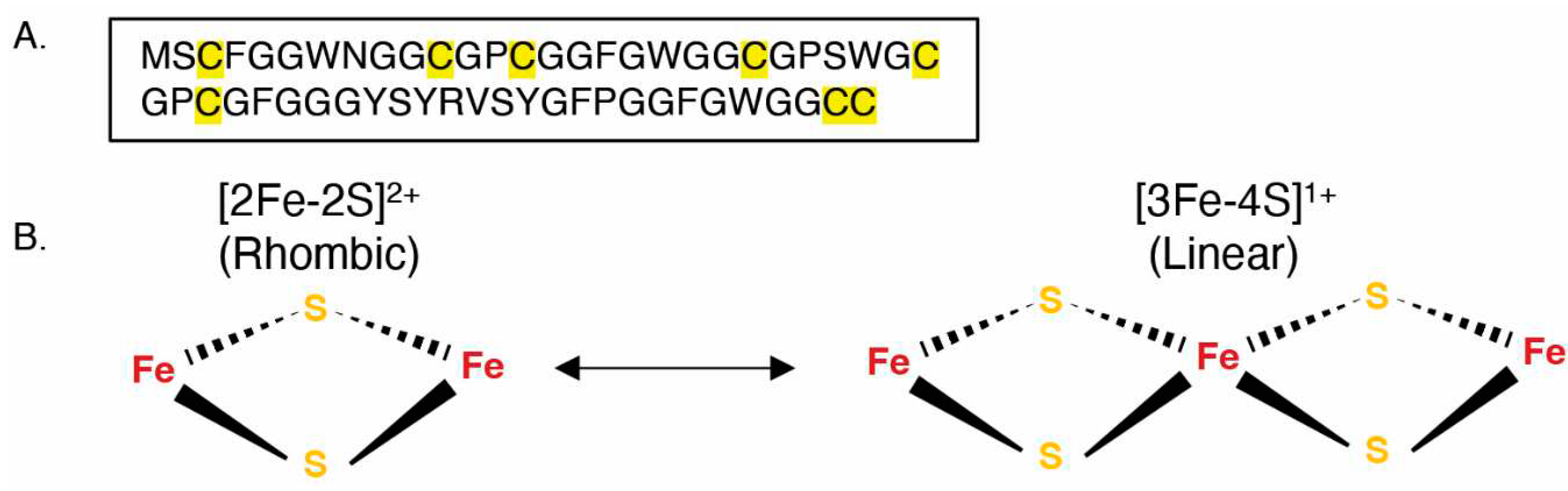

- Villalta, A.; Srour, B.; Lartigue, A.; Clemancey, M.; Byrne, D.; Chaspoul, F.; Loquet, A.; Guigliarelli, B.; Blondin, G.; Abergel, C.; Burlat, B. Evidence for [2Fe-2S](2+) and Linear [3Fe-4S](1+) Clusters in a Unique Family of Glycine/Cysteine-Rich Fe-S Proteins from Megavirinae Giant Viruses. J Am Chem Soc 2023, 145(5), 2733–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Shakamuri, P.; Naik, S. G.; Huynh, B. H.; Couturier, J.; Rouhier, N.; Johnson, M. K. Monothiol glutaredoxins can bind linear [Fe3S4]+ and [Fe4S4]2+ clusters in addition to [Fe2S2]2+ clusters: spectroscopic characterization and functional implications. J Am Chem Soc 2013, 135(40), 15153–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E. V.; Krupovic, M.; Agol, V. I. The Baltimore Classification of Viruses 50 Years Later: How Does It Stand in the Light of Virus Evolution? Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2021, 85(3), e0005321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peersen, O. B. A Comprehensive Superposition of Viral Polymerase Structures. Viruses 2019, 11 (8). [CrossRef]

- de Farias, S. T.; Dos Santos Junior, A. P.; Rego, T. G.; Jose, M. V. Origin and Evolution of RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase. Front Genet 2017, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez-Arias, L.; Sebastian-Martin, A.; Alvarez, M. Viral reverse transcriptases. Virus Res 2017, 234, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessions, A. L.; Doughty, D. M.; Welander, P. V.; Summons, R. E.; Newman, D. K. The continuing puzzle of the great oxidation event. Curr Biol 2009, 19(14), R567–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maio, N.; Cherry, S.; Schultz, D. C.; Hurst, B. L.; Linehan, W. M.; Rouault, T. A. TEMPOL inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication and development of lung disease in the Syrian hamster model. iScience 2022, 25(10), 105074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, S. SARS-CoV-2 Subgenomic RNAs: Characterization, Utility, and Perspectives. Viruses 2021, 13 (10). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).