Submitted:

19 December 2023

Posted:

19 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

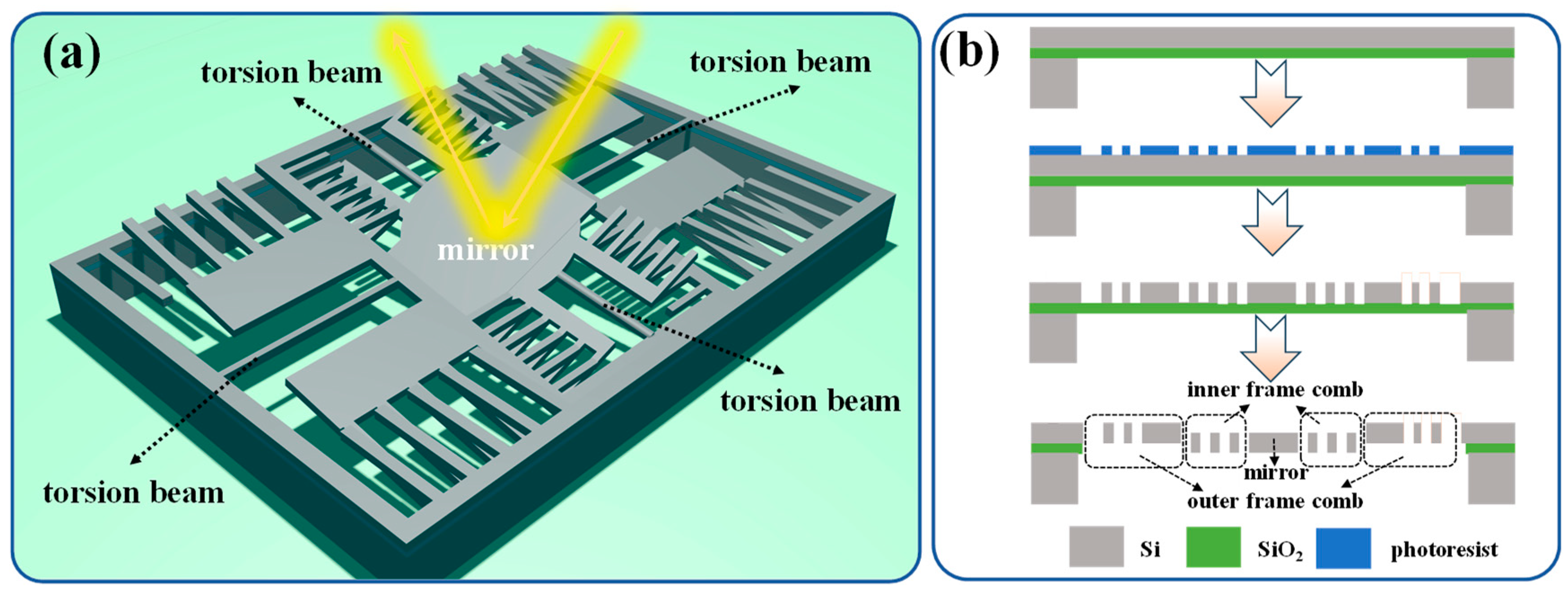

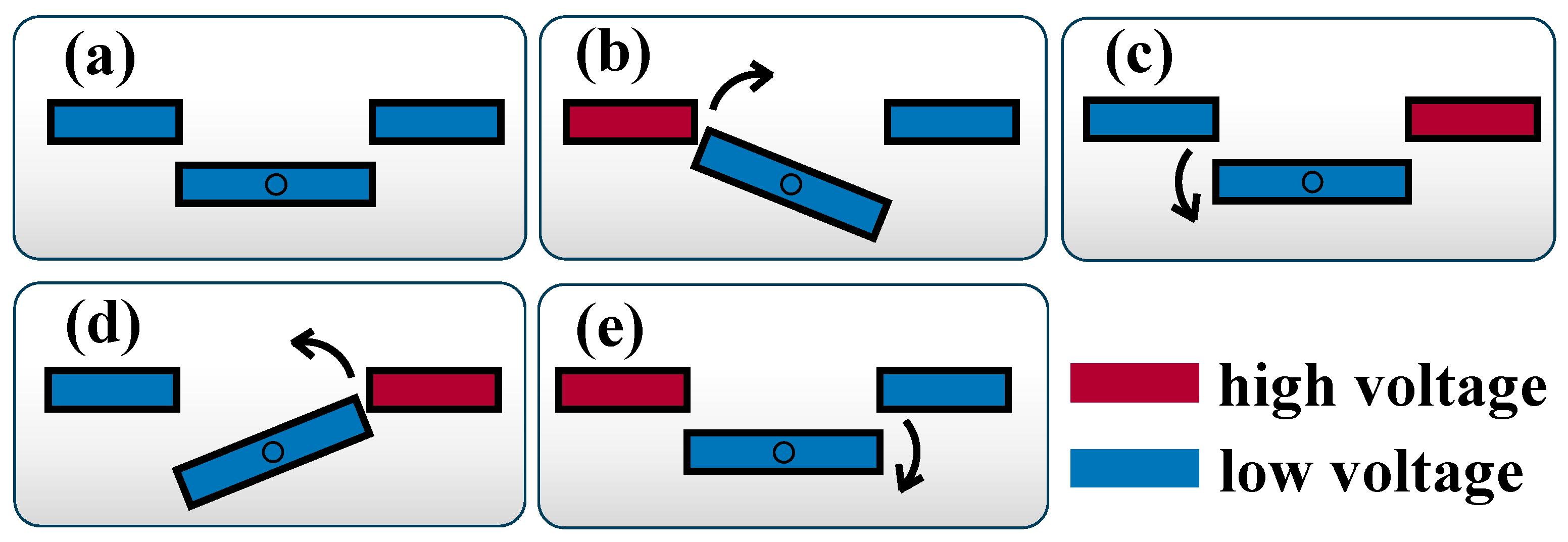

2. Design and method

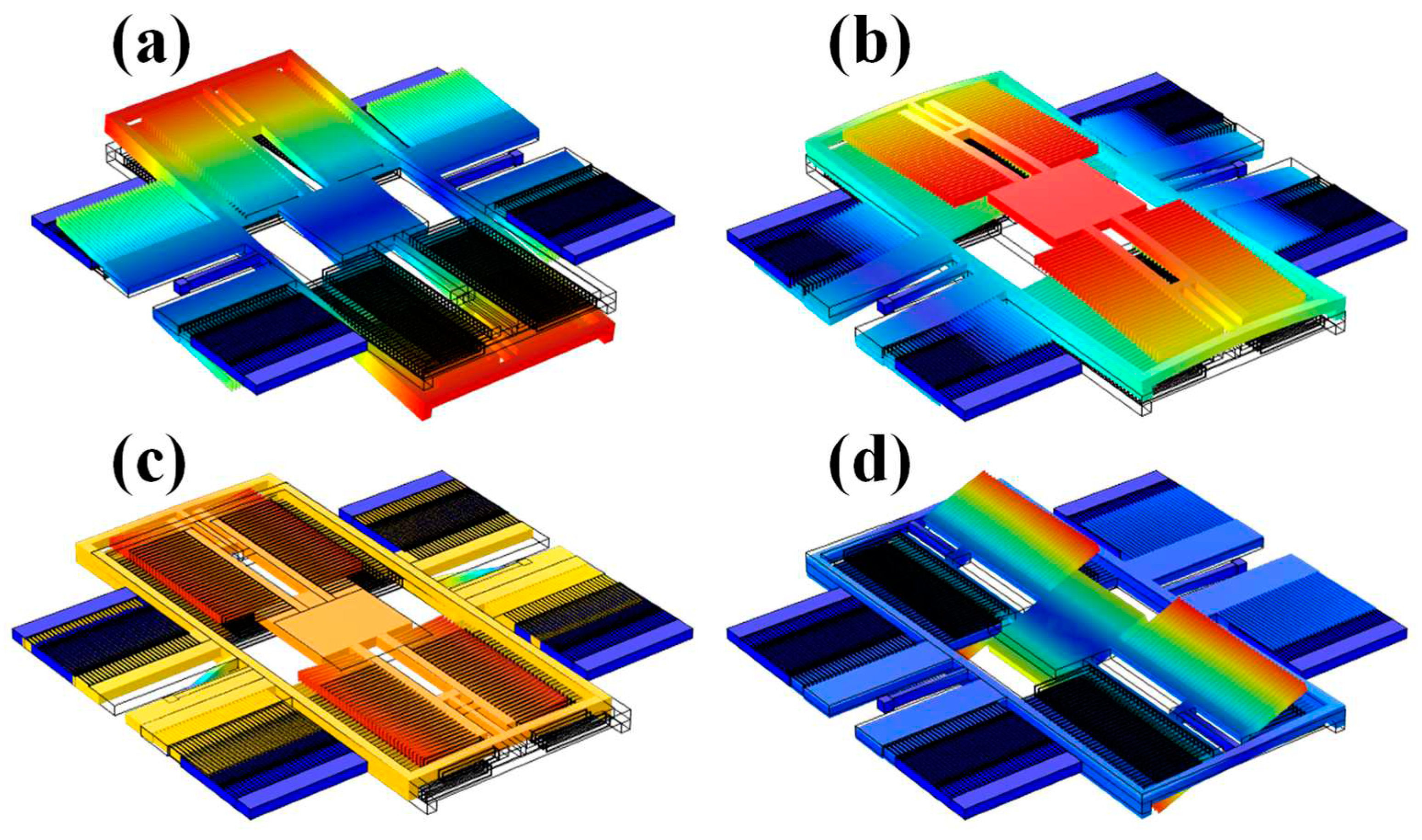

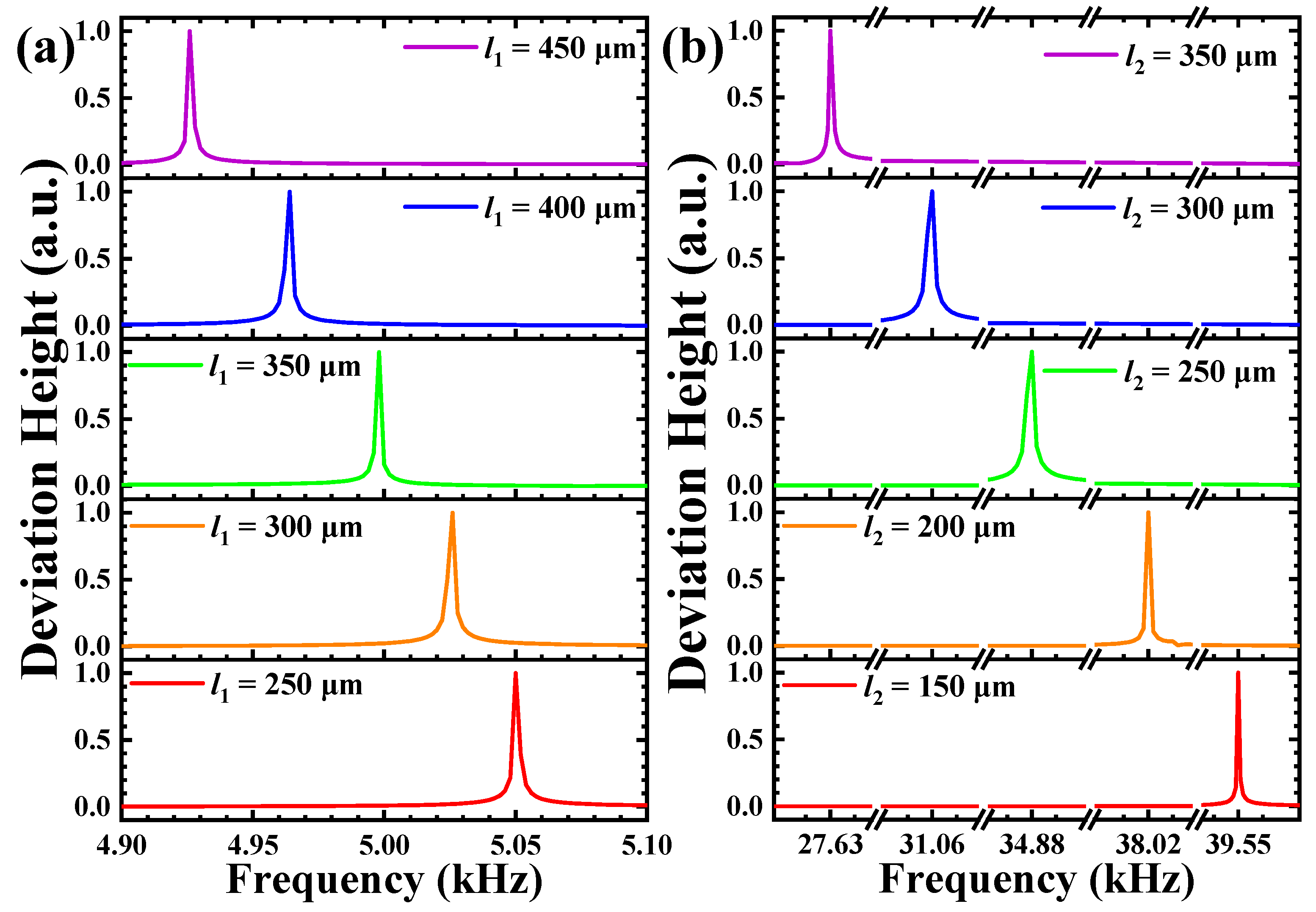

3. Results and discussions

4. Conclusion

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

References

- W. M. Miller, “Reliability: A Hidden Barrier to Successful Commercialization of MEMS”, Micromachine Devices, 1-4 (1997).

- Y. Hu, X. Shen, Y. Zhang, Z. Wang, and X. Chen, “Research Reviews and Prospects of MEMS Reliability”, Integrated Ferroelectrics, 152(1), 8-21 (2014). [CrossRef]

- F. Mohd-Yasin, D. J. Nagel, and C. E. Korman, “Noise in MEMS”, Measurement Science and Technology, 21(1), 012001 (2010). [CrossRef]

- X. Y. Fang, C. C. Liu, X. Y. Li, J. H. Wu, K. M. Hu, and W. M. Zhang, “Evaluation of Residual Stress in MEMS Micromirror Die Surface Mounting Process and Shock Destructive Reliability Test”, IEEE Sensors Journal, 23(14), 15461-15468 (2023). [CrossRef]

- X. Y. Fang, X. Y. Li, K. M. Hu, G. Yan, J. H. Wu, and W. M. Zhang, “Destructive Reliability Analysis of Electromagnetic MEMS Micromirror Under Vibration Environment”, IEEE Journal of Quantum Electronics, 28(5), 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. An, E. E. Langas, and A. S. Gill, “Effect of Scanning Speed, Scanning Pattern, and Tip Size on the Accuracy of Intraoral Digital Scans”, The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 2022. [CrossRef]

- U. Hofmann, S. Muehlmann, M. Witt, K. Doerschel, R. Schuetz, and B. Wagner, “Electrostatically Driven Micromirrors for A Miniaturized Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope”, Proceedings of SPIE, 29-38 (1999). [CrossRef]

- U. Hofmann, J. Janes, and H.-J. Quenzer, “High-Q MEMS Resonators for Laser Beam Scanning Displays”, Micromachines, 3, 509-528 (2012). [CrossRef]

- B. G. Cho, H. S. Tae, D. H. Lee, and S. Chein, “A new overlap-scan circuit for high speed and low data voltage in plasma-TV”, IEEE Transaction on Consumer Electronics, 51(4), 1218-1222 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Y.-H. Seo, K. Hwang, H. Kim, and K.-H. Jeong, “Scanning MEMS Mirror for High Definition and High Frame Rate Lissajous Patterns”, Micromachines, 10(1), 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Yang, Y. Liu, Q. Chen, M. Chen, S. Zhan, N.-K. Cheung, H.-Y. Chan, Z. Wang, and W. J. Li, “Development of the High Angular Resolution 360° LiDAR based on Scanning MEMS Mirror”, Scientific Reports, 13, 1540 (2023). [CrossRef]

- W. C. Stone, M. Juberts, N. Dagalakis, J. A. Stone Jr., and J. J. Gorman, “Performance Analysis of Next-Generation LADAR for Manufacturing, Construction, and Mobility”, NIST Interagency or Internal Reports, 7117 (2004). [CrossRef]

- F. Xu, D. Qiao, C. Xia, X. Song, and Y. He, “Fast Synchronization Method of Comb-Actuated MEMS Mirror Pair for LiDAR Application”, Micromachines, 12(11), 2021. [CrossRef]

- Q. Li, Y. Zhang, R. Fan, Y. Wang, Y. Wang, and C. Wang, “MEMS mirror based omnidirectional scanning for LiDAR optical systems”, Optics and Lasers in Engineering, 158, 10178 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Z. Ren, Y. Chang, Y. Ma, K. Shih, B. Dong, and C. Lee, “Leveraging of MEMS Technologies for Optical Metamaterials Applications”, Advanced Optical Materials, 8(3) (2020). [CrossRef]

- W. M. Zhu, A. Q. Liu, X. M. Zhang, D. P. Tsai, T. Bourouina, J. H. Teng, X. H. Zhang, H. C. Guo, H. Tanoto, T. Mei, G. Q. Lo, and D. L. Kwong, “Switchable Magnetic Metamaterials Using Micromachining Processes”, Advanced Materials, 23(15), 1792-1796 (2011). [CrossRef]

- S. Chen, S. F. Tan, H. Singh, L. Liu, M. Etienne, and P. S. Lee, “Functionalized MXene Films with Substantially Improved Low-voltage Actuation”, Advanced Materials, e2307045 (2023). [CrossRef]

- H. Tao, A. C. Strikwerda, K. Fan, W. J. Padilla, X. Zhang, and R. D. Averitt, “Reconfigurable Terahertz Metamaterials”, Physical Review Letters, 103, 147401 (2009). [CrossRef]

- P. F. McManamon, P. J. Bos, M. J. Escuti, J. Heikenfeld, S. Serati, H. K. Xie, and E. A. Watson, “A Review of Phased Array Steering for Narrow-Band Electrooptical Systems”, Proceedings of the IEEE, 97(6), 1078-1096 (2009). [CrossRef]

- X. Hu, G. Q. Xu, L. Wen, H. C. Wang, Y. C. Zhao, Y. X. Zhang D.R.S. Cumming, and Q. Chen, “Metamaterial Absorber Integrated Microfluidic Terahertz Sensors”, Laser & Photonics Reviews, 10(6), 962-969 (2016). [CrossRef]

- B. Appasani, A. Srinivasulu, and C. Ravariu, “A high Q terahertz metamaterial absorber using concentric elliptical ring resonators for harmful gas sensing applications”, Defence Technology, 22, 69-73 (2023). [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, D. Zheng, and Y.-S. Lin, “Electric Split-Ring Metamaterial Based Microfluidic Chip with Multi-Resonances for Microparticle Trapping and Chemical Sensing Applications”, Journal of Colloid Interface Science, 642, 462-469 (2023). [CrossRef]

- D. Wang, C. Watkins, and H. Xie, “MEMS Mirrors for LiDAR: A Review”, Micromachines, 11, 456 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, G. Zhang, and Z. You, “Improved Sampling Scheme for LiDAR in Lissajous Scanning Mode”, Microsystems & Nanoengineering, 8(1), 64 (2022). [CrossRef]

- J. Raj, F. H. Hashim, A. B. Huddin, M. F. Ibrahim, and A. Hussain, “A Survey on LiDAR Scanning Mechanisms”, Electronics, 9(5), 741 (2020). [CrossRef]

- T. Iseki, M. Okumura, and T. Sugawara, “Two-Dimensionally Deflecting Mirror Using Electromagnetic Actuation”, Optical Review, 13, 189-194 (2006). [CrossRef]

- C. Ataman, S. Lani, W. Noell, and N. De Rooij, “A Dual-Axis Pointing Mirror with Moving-Magnet Actuation”, Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering, 23, 25002 (2012). [CrossRef]

- J. Yunas, B. Mulyanti, I. Hamidah, M. Mohd Said, R. E. Pawinanto, W. A. F. W. Ali, A. Subandi, A. A. Hamzah, R. Latif, and B. Yeop Majlis, “Polymer-Based MEMS Electromagnetic Actuator for Biomedical Application: A Review”, Polymers, 12(5), 1184 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu, W. Liu, K. Jia, W. Liao, and H. Xie, “A Piezoelectric Unimorph Actuator Based Tip-Tilt-Piston Micromirror with High Fill Factor and Small Tilt and Lateral Shift”, Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 167, 495-501 (2011). [CrossRef]

- W. Liu, Y. Zhu, K. Jia, W. Liao, Y. Tang, B. Wang, and H. Xie, “A Tip-Tilt-Piston Micromirror with a Double S-shaped Unimorph Piezoelectric Actuator”, Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 193, 121-128 (2013). [CrossRef]

- S. Mohith, A. R. Upadhya, K. P. Navin, S. M. Kulkarni, and M. Rao, “Recent Trends in Piezoelectric Actuators for Precision Motion and Their Applications: A Review”, Smart Materials and Structures, 30(1), 013002 (2021). [CrossRef]

- H. Tao, A. C. Strikwerda, K. Fan, W. J. Padilla, X. Zhang, and R. D. Averitt, “Reconfigurable Terahertz Metamaterials”, Physical Review Letters, 103, 147401 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Y. Tang, J. H. Li, L. X. Xu, J. B. Lee, and H. K. Xie, “Review of Electrothermal Micromirrors”, Micromachines, 13(3), 429 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Potekhina, and C. Wang, “Review of Electrothermal Actuators and Applications”, Actuators, 8(4), 69 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J. Tsai, and M. C. Wu, “Design, Fabrication, and Characterization of a High Fill-Factor, Large Scan-Angle, Two-Axis Scanner Array Driven by a Leverage Mechanism”, Journal of Microelectromechanical System, 15(5), 1209-1213 (2006). [CrossRef]

- B. Sargent, R. Harbourne, N. G. Moreau, T. Sukal-Moulton, M. Tovin, J. L. Cameron, R. D. Stevenson, I. Novak, and J. Heathcock, “Research Summit V: Optimizing Transitions from Infancy to Early Adulthood in Children with Neuromotor Conditions”, Pediatric Physical Therapy, 34(3), 411-417 (2022). [CrossRef]

- D. Hah, P. R. Patterson, H. D. Nguyen, H. Toshiyoshi, and M. C. Wu, “Theory and Experiments of Angular Vertical Comb-Drive Actuators for Scanning Micro-mirrors”, IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, 10 (3), 505-513 (2004). [CrossRef]

- T. Izawa, T. Sasaki, and K. Hane, “Scanning Micro-Mirror with an Electrostatic Spring for Compensation of Hard-Spring Nonlinearity”, Micromachines, 8(8), (2017). [CrossRef]

- D. Brunner, H. W. Yoo, and G. Schitter, “Linear Modeling and Control of Comb-Actuated Resonant MEMS Mirror With Nonlinear Dynamics”, IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 68(4), 3315-3323 (2021). [CrossRef]

- T. Tsuchiya, “Tensile testing of silicon thin films”, Deep Underground Science and Engineering, 665-674 (2005). [CrossRef]

| parameter | value |

|---|---|

| mirror size | 500 μm × 500 μm |

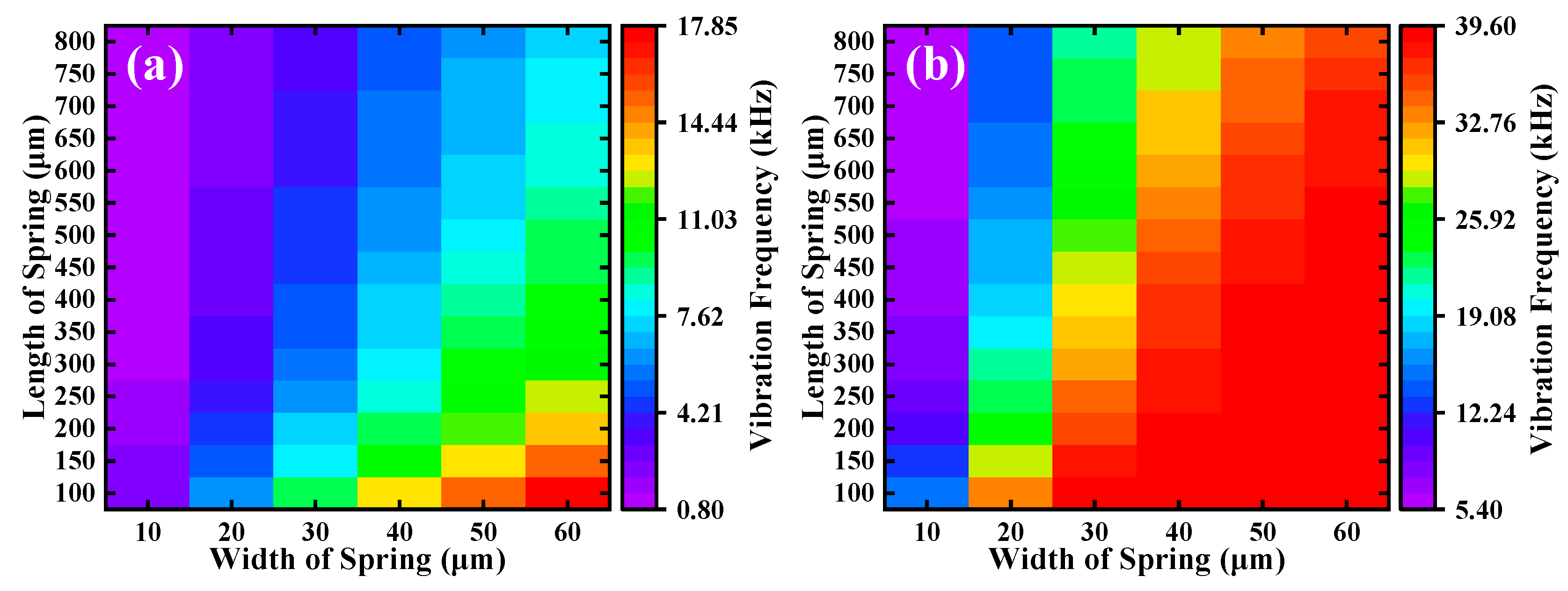

| length of torsion beam in slow axis, lt1 | 400 μm |

| width of torsion beam in slow axis, wt1 | 30 μm |

| length of torsion beam in fast axis, lt2 | 350 μm |

| Width of torsion beam in fast axis, lt2 | 30 μm |

| length of fingers in slow axis, l1 | 400 μm |

| width of fingers in slow axis, w1 | 5 μm |

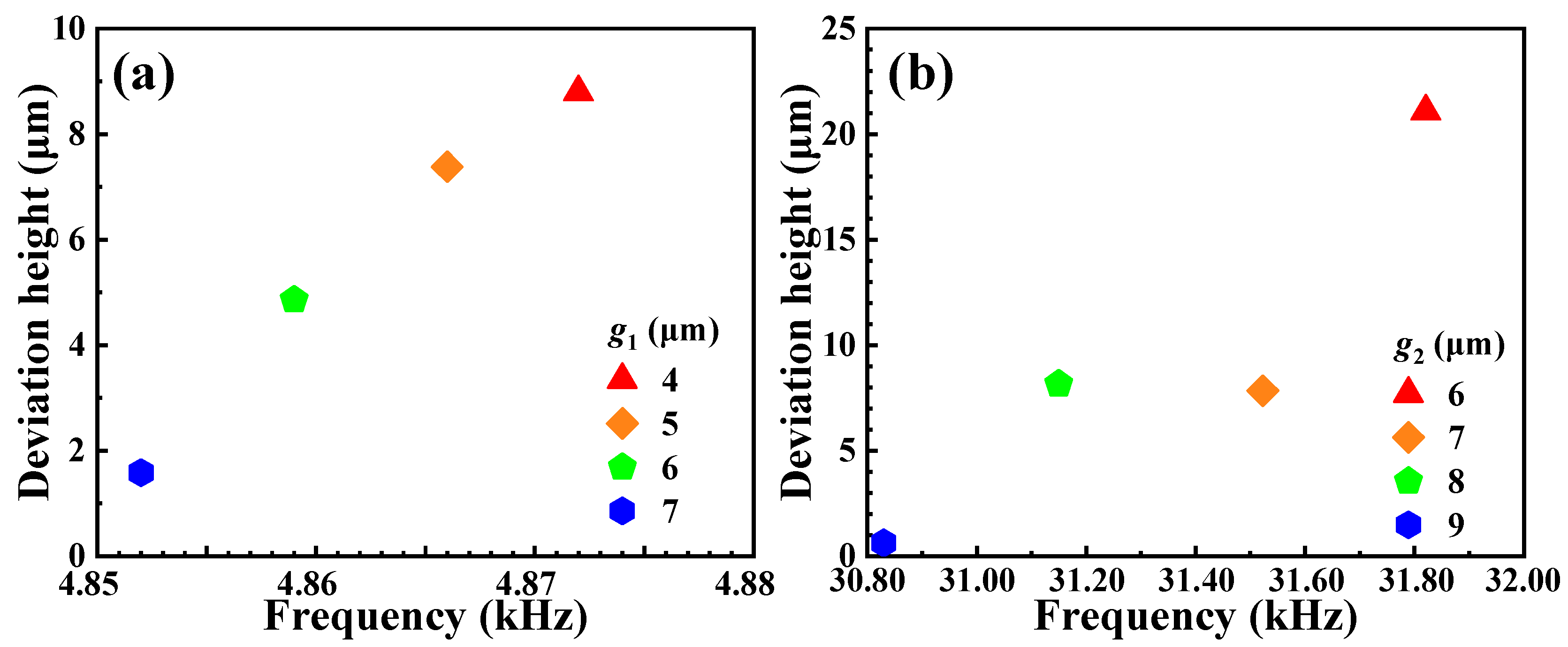

| gap between fingers in slow axis, g1 | 5 μm |

| overlapping length of slow axis, lo1 | 300 μm |

| number of fingers in slow axis, n1 | 30 × 4 |

| length of fingers in fast axis, l2 | 300 μm |

| width of fingers in fast axis, w2 | 5 μm |

| gap between fingers in fast axis, g2 | 8 μm |

| overlapping length of fast axis, lo2 | 250 μm |

| number of fingers in fast axis, n2 | 34 × 4 |

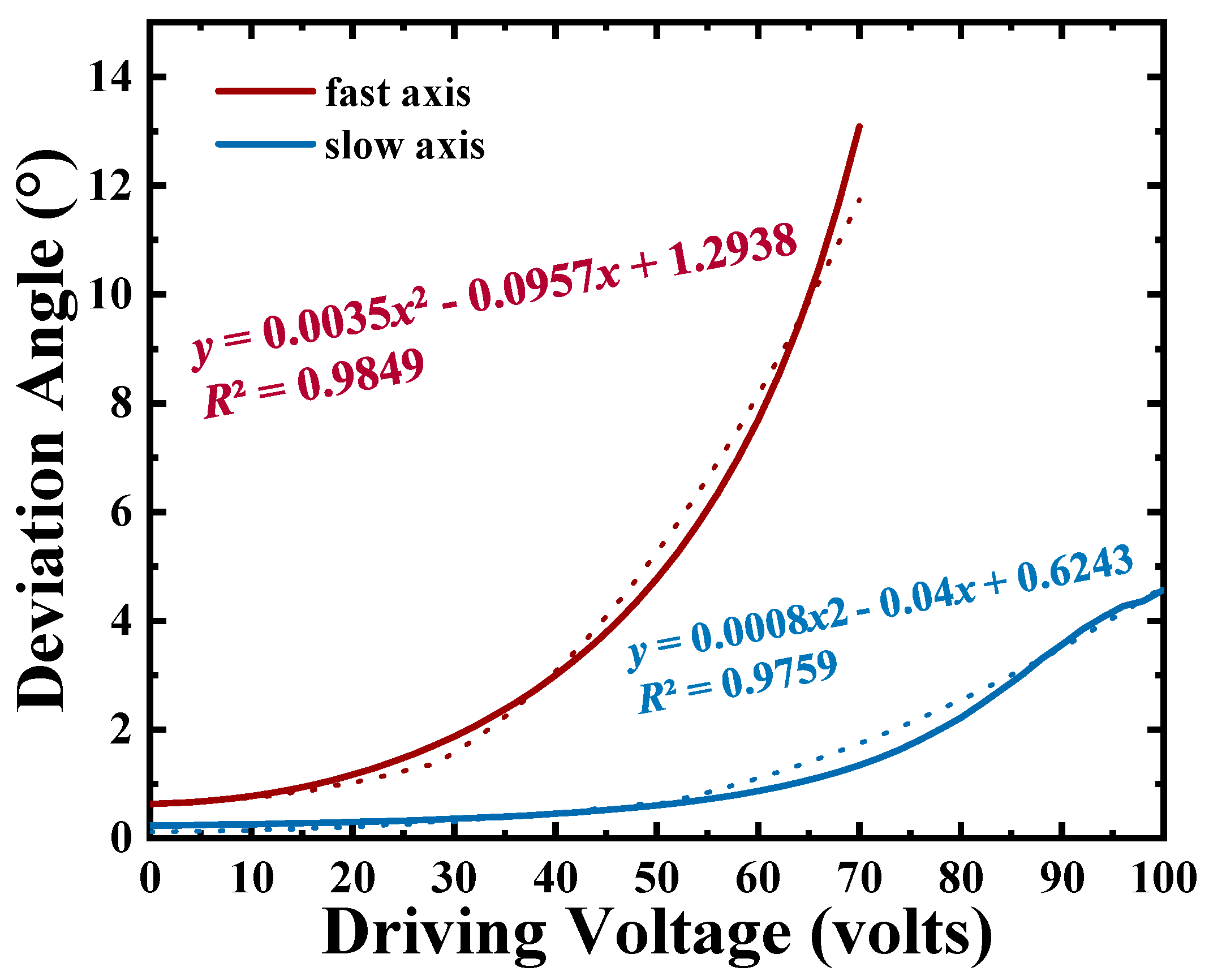

| voltage potential difference between slow combs, V 1 | 70 volts |

| voltage potential difference between fast combs, V 2 | 30 volts |

| thickness of the scanning micromirror, t | 50 μm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).