1. Introduction

The construction of infrastructure, such as bored cast-in-place piles, underground continuous walls, and slurry shield tunnels, generates a substantial amount of waste mud [

1,

2]. However, the treatment and disposal of waste mud is a difficult problem in engineering construction [

3,

4]. If waste mud is not properly treated, it will occupy a large area of land for disposal and could cause serious pollution to the environment [

5,

6]. To actively respond to the relevant indicators of “carbon peak” and “carbon neutrality,” China has implemented a “dual control” policy on energy consumption. This has resulted in an imbalance in the power supply, impacting the production and processing of sand and gravel enterprises [

7]. Consequently, there has been a shortage of sand and gravel in many areas of China, and this insufficient volume of traditional roadbed filling materials is becoming increasingly serious [

8]. Therefore, a relevant question is whether or not treated waste mud can be used as roadbed filling material.

For waste mud to meet the requirements of roadbed filling material, solidification materials are widely used to solidify the waste mud. Horpibulsk et al. found that the clay water/cement ratio is a key factor in determining the strength development of cement-cured Bangkok clay in both laboratory and field settings, and that the bonding strength increases with a decrease in the clay water/cement ratio [

9]. Chen et al. used cement to solidify waste mud and found that by adding 3% cement, the cubic compressive strengths of the waste mud–solidified soil reached 0.2 MPa, 0.35 MPa, and 0.7 MPa at curing times of 3, 7, and 28 days, respectively [

10]. Gao et al. used cement, fly ash, slag micropowder, and plant ash for solidification of waste mud and found that adding 4% cement and 8% fly ash resulted in an unconfined compressive strength of the solidified soil of 250 kPa after 28 days [

11]. To more effectively use waste mud for embankment filling, Zhang et al. proposed a treatment method using flocculation solidification combined with vacuum preloading. Flocculation solidification can exert an efficient dehydration effect, and low vacuum preloading can significantly reduce the moisture content of the mud and improve the solidification efficiency of the solidification agent; combined, the overall soil was effectively reinforced [

12]. Ding et al. developed a curing agent based on cement, mixed gypsum, quicklime, silica fume, and absorbent resin to treat waste mud generated during slurry shield tunnel construction. When the cement content was 15% and the admixture content was 12%, the early compressive strength of the solidified soil was the highest, with an unconfined compressive strength of 1203 kPa at 60 days. The rapid increase in strength was caused by the production of a large amount of hydration products [

13]. Tian et al. prepared unfired ceramsite by mixing waste mud with cement, quicklime, and water glass, and found that when the mud: cement ratio was 3:1, the quicklime content was 10%, the water glass content was 1%, and the mud-based unfired ceramsite had lower water absorption and mud content, higher strength, and good performance [

14]. Unconfined compressive strength is often used to evaluate the solidification effect of waste mud [

3,

11]; however, the mechanism by which the solidifying materials affect the strength of waste mud is currently unclear. Moreover, as a roadbed filler, the shear and deformation characteristics of waste mud–solidified soil also need to be studied.

For this study, waste mud was collected from a highway reconstruction project and used to study the effects and mechanism of solidification. Unconfined compressive strength tests, consolidated undrained shear triaxial tests, consolidation compression tests, and resonance column tests were conducted to investigate the strength and deformation characteristics of waste mud–solidified soil. Combined with the results of scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) tests, the solidification mechanism of waste mud was revealed. This study can provide technical support for the treatment, disposal, and resource utilization of waste mud.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Test materials

The waste mud used in this study was obtained from a national highway reconstruction project near Hangzhou, China. The basic properties of the waste mud are shown in

Table 1. The waste mud had an optimum moisture content of 16.6% and a maximum dry density of 1.768 g/m

3. The solidifying material used in this study was ordinary Portland cement (PC 42.5).

2.2. Test methods

The dehydrated waste mud was dried in a drying oven and then crushed through a 2-mm sieve to obtain waste mud dry soil. A certain amount of dry soil was taken for each test, and pure water was added to make waste mud with different initial moisture contents (40%, 50%, and 60%). Ordinary Portland cement was added to the waste mud, and the mixture was stirred fully using a mud mixer to prepare the waste mud–solidified soil. Three cement contents (5%, 7%, and 9% of dry soil mass) were tested. The prepared waste mud–solidified soil samples were cured in a constant temperature curing box for 3, 7, 14, or 28 days.

Using the Standard for geotechnical test methods (GB/T 50123-2019), the unconfined compressive strength test, consolidated undrained triaxial shear test, consolidation compression test, and resonant column test were conducted on the waste mud–solidified soil samples to obtain the unconfined compressive strength, shear strength, compression curve, dynamic shear modulus, and damping ratio under different conditions [

15].

The original soil and solidified soil samples with different cement contents were selected. After the samples reached the curing time, the middle part of the samples was ground into fine powder. The powder was dried and subjected to SEM and XRD analysis.

3. Test results

3.1. Unconfined compressive strength

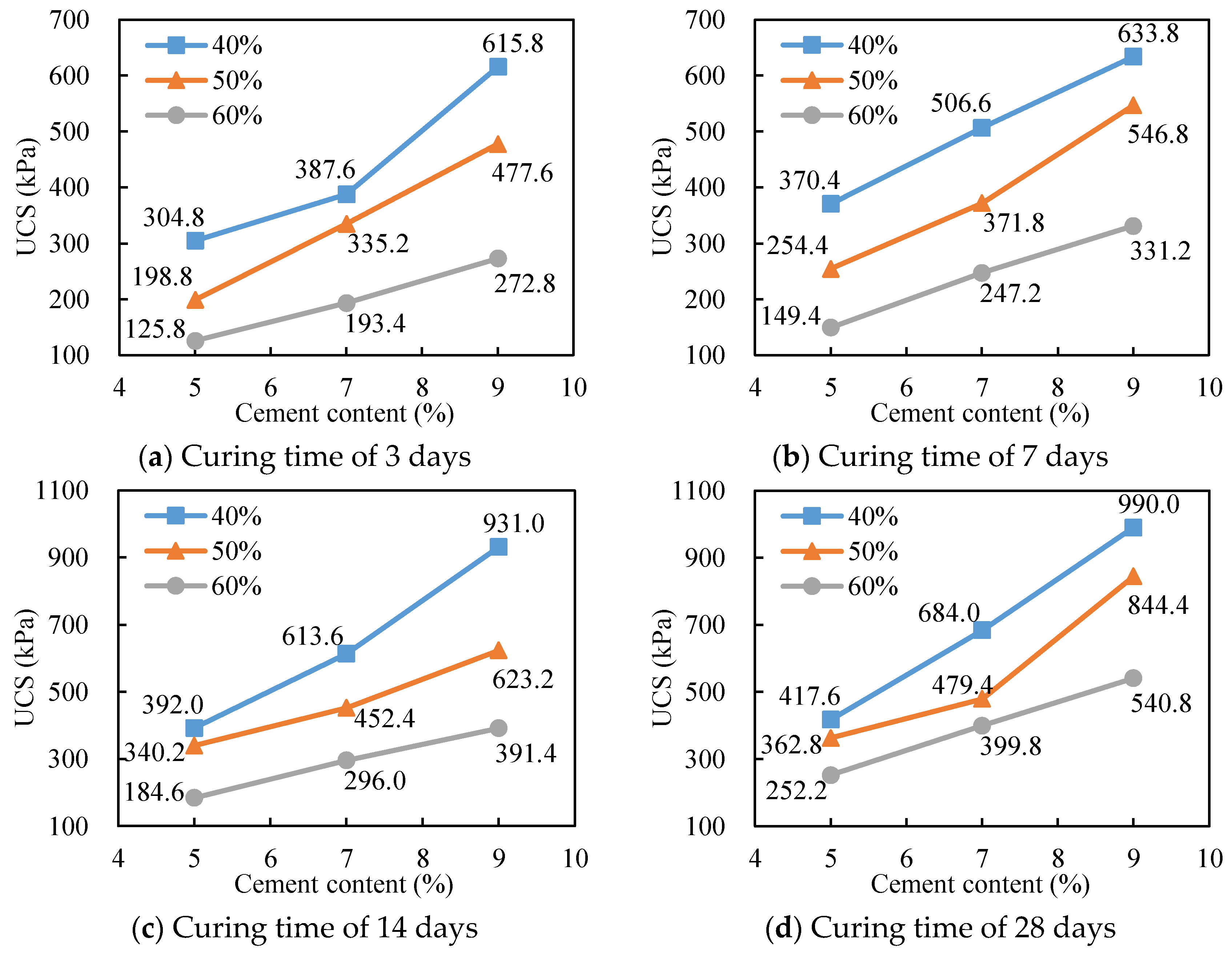

Figure 1 shows the influence of cement contents on the unconfined compressive strength of waste mud–solidified soil. The unconfined compressive strength of waste mud–solidified soil increased with increasing cement content. For example, waste mud–solidified soil with an initial moisture content of 40% and a cement content of 5% had increasing unconfined compressive strengths after curing times of 3, 7, 14, and 28 days of 304.8, 370.4, 392.0, and 417.4 kPa, respectively. The samples with the same moisture content and 9% cement content had increasing unconfined compressive strengths at the four curing times (3, 7, 14, and 28 days) of 615.8, 633.8, 931.0, and 990.0 kPa, respectively. With the cement content increasing from 5% to 9%, the strength of these samples increased by 102.03%, 71.11%, 137.5%, and 137.18% respectively. The strength changes of the waste mud–solidified soil at the other two moisture contents were similar to the results for 40% moisture.

In addition, a lower initial moisture content resulted in a more notable effect of the cement content on the unconfined compressive strength of waste mud–solidified soil. When the initial moisture content was 40% and the cement content increased from 5% to 9%, the unconfined compressive strength of waste mud–solidified soil increased by an average of 125.57% at different curing times. When the initial moisture contents were 50% and 60%, the average increases in the unconfined compressive strength of waste mud–solidified soil were 117.78% and 105.77%, respectively.

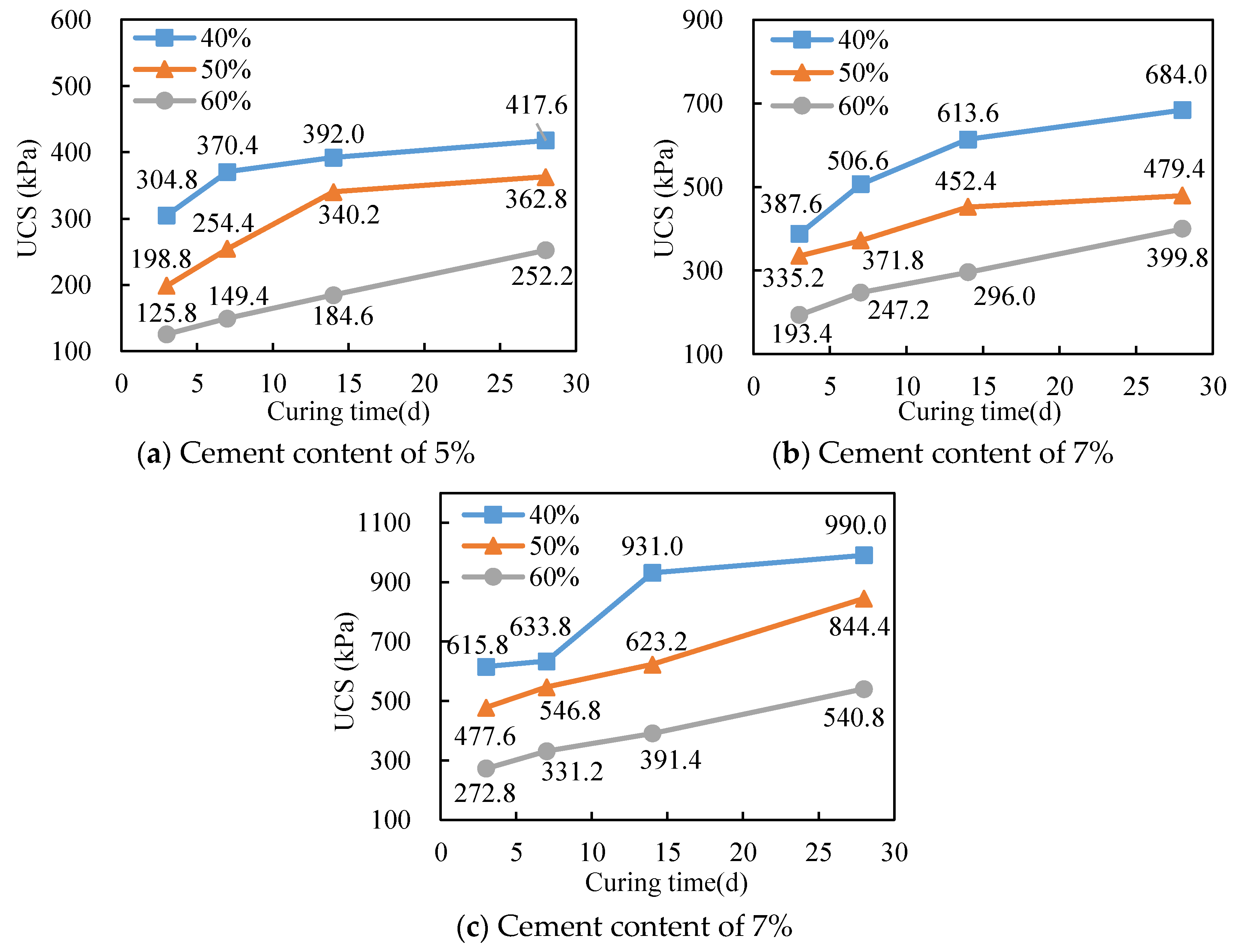

Figure 2 shows the effect of curing time on the unconfined compressive strength of waste mud–solidified soil. With the increase in curing time, the unconfined compressive strength of waste mud–solidified soil also increased. As the curing time increased from 3 to 28 days, the unconfined compressive strength of solidified soil with a cement content of 5% and initial moisture content of 40% increased from 304.8 kPa to 417.6 kPa. The unconfined compressive strength of solidified soil with a cement content of 7% increased from 387.6 kPa to 684 kPa over the curing time. The unconfined compressive strength of solidified soil with a cement content of 9% increased from 615.8 kPa to 990 kPa over the curing time. The unconfined compressive strength increased by an average of 58.08% over the curing time with different cement contents. However, when the initial moisture content was 50% and 60%, the unconfined compressive strength increased by 67.43% and 101.81%, respectively, as the curing time increased from 3 to 28 days. Therefore, a higher initial moisture content resulted in a more significant effect of curing time on the unconfined compressive strength.

For solidified soil at each cement content, the increase of the unconfined compressive strength of waste mud–solidified soil was more rapid during the early stages of curing, then the increase became slower and tended to stabilize. For example, during the curing time from 7 to 14 days, the unconfined compressive strength of the solidified soil with a cement content of 9% and initial moisture content of 40% increased by as much as 46.9%. However, during the curing time for this sample from 14 to 28 days, the unconfined compressive strength increased by only 6.33%. With the continuous increase in curing time, the increasing rate of the unconfined compressive strength of solidified soil with each cement content gradually decreased, which indicates that as the hydration reactions of the cement end, the curing time has little influence on the improvement of the unconfined compressive strength.

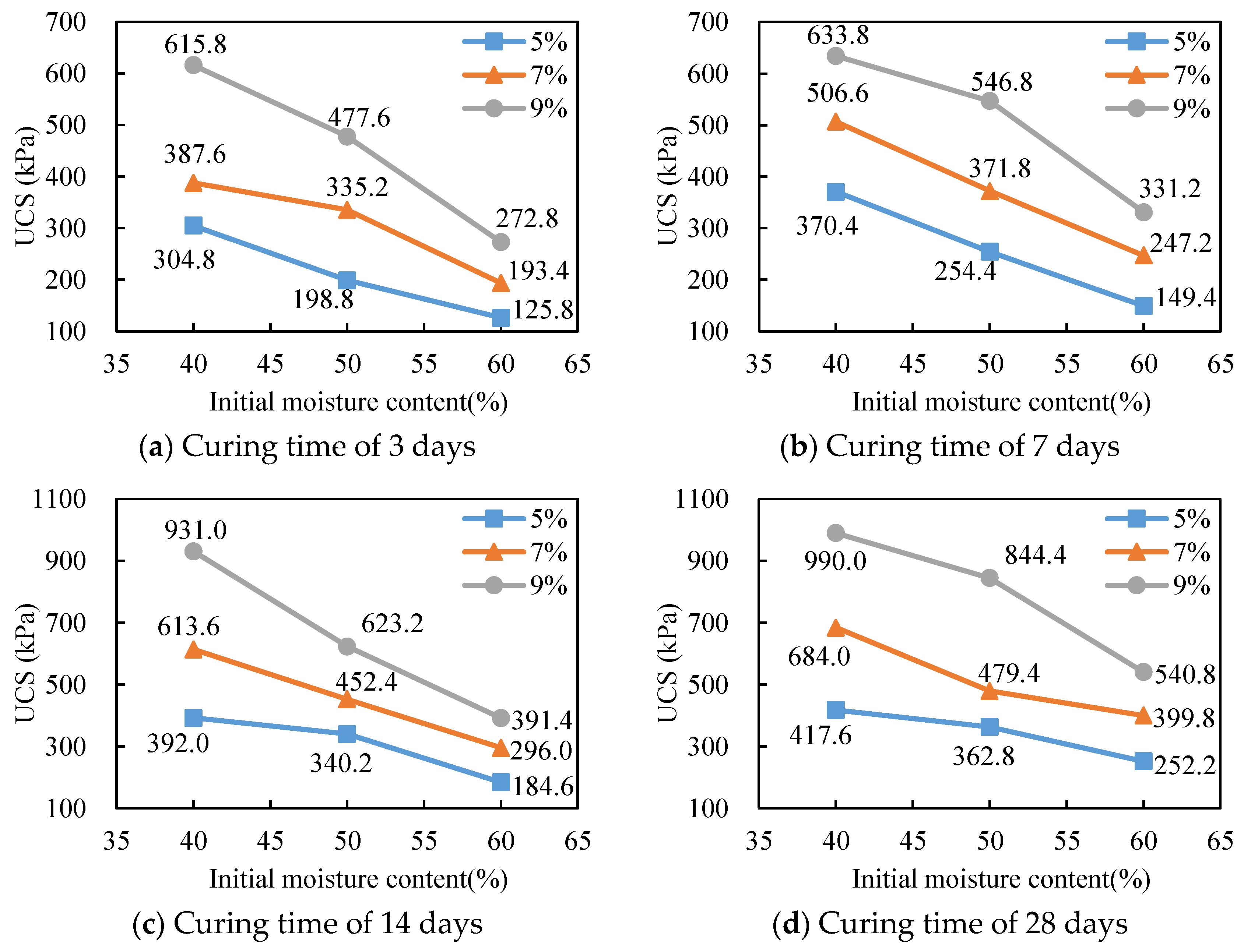

Figure 3 shows the effect of the initial moisture content on the unconfined compressive strength of the waste mud–solidified soil. The unconfined compressive strength of the waste mud–solidified soil decreased with increasing initial moisture content.

At a curing time of 3 days, with an initial moisture content increasing from 40% to 60%, the unconfined compressive strength of the waste mud–solidified soil decreased from 304.8 kPa to 125.8 kPa (reduced by 58.7%); at a curing time of 7 days, with an initial moisture content increasing from 40% to 60%, the unconfined compressive strength of the waste mud–solidified soil decreased from 370.4 kPa to 149.4 kPa (reduced by 59.7%); at a curing time of 14 days, with an initial moisture content increasing from 40% to 60%, the unconfined compressive strength of the waste mud–solidified soil decreased from 392.0 kPa to 184.6 kPa (reduced by 52.9%); and at a curing time of 28 days, with an initial moisture content increasing from 40% to 60%, the unconfined compressive strength of the waste mud–solidified soil decreased from 417.6 kPa to 252.2 kPa (reduced by 39.6%). Therefore, a shorter curing time resulted in a more significant effect of initial moisture content on the unconfined compressive strength of waste mud–solidified soil.

3.2. Consolidated undrained shear strength

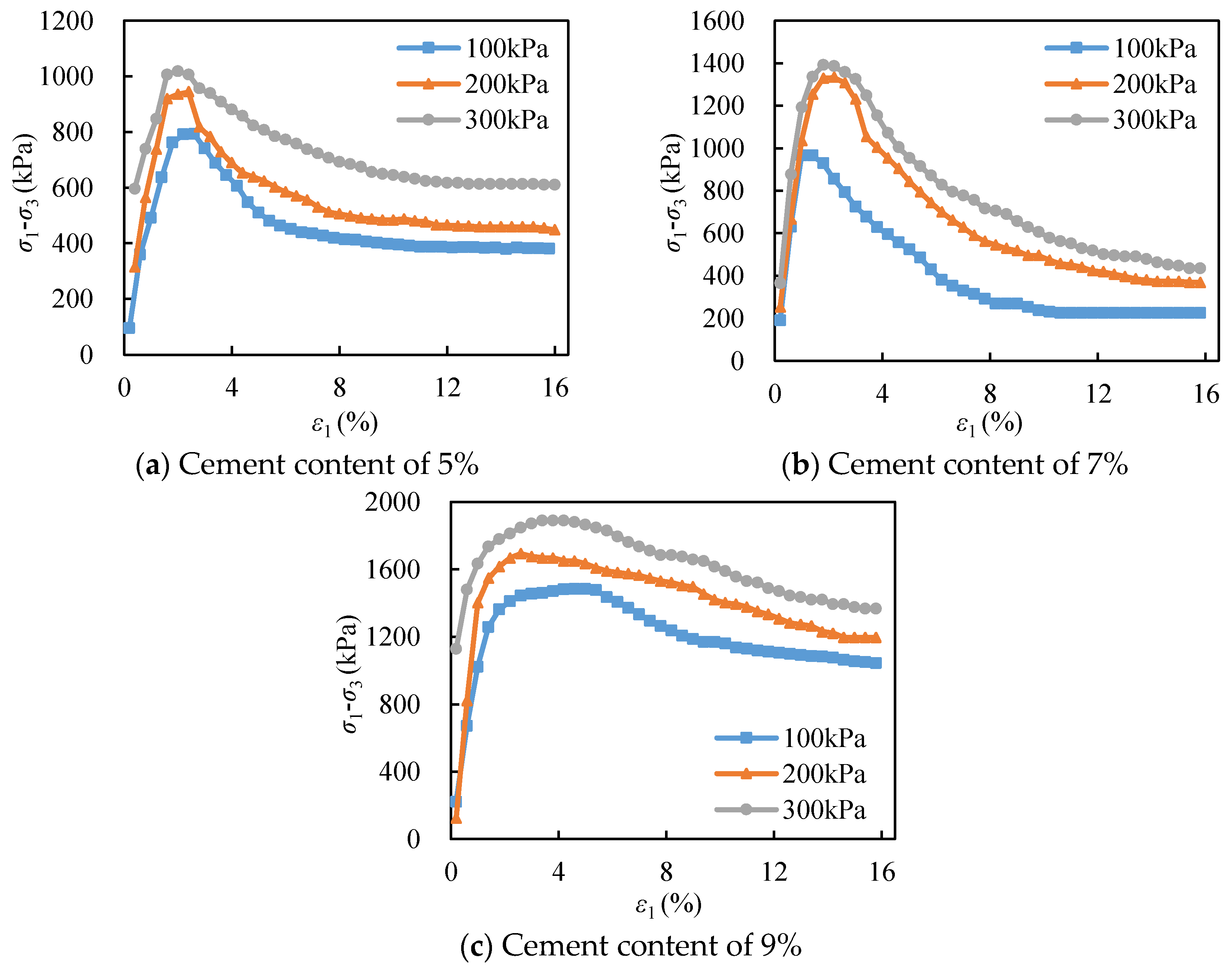

Consolidated undrained triaxial shear tests were conducted on soil with an initial moisture content of 40% and curing time of 28 days. The main stress difference and axial strain curves for soils with the three different cement contents are shown in

Figure 4. The main stress difference and the axial strain curve of the waste mud–solidified soil under different cement contents all had the same pattern of change. With an increase in axial strain, the main stress difference first increased but then decreased and eventually tended to stabilize. In addition, the peak of the main stress difference also increased with increasing cement content. For example, at a surrounding pressure of 300 kPa, the soils with cement contents of 5%, 7%, and 9% had maximum main stress differences of 1018.2 kPa, 1390.8 kPa, and 1890.2 kPa, respectively.

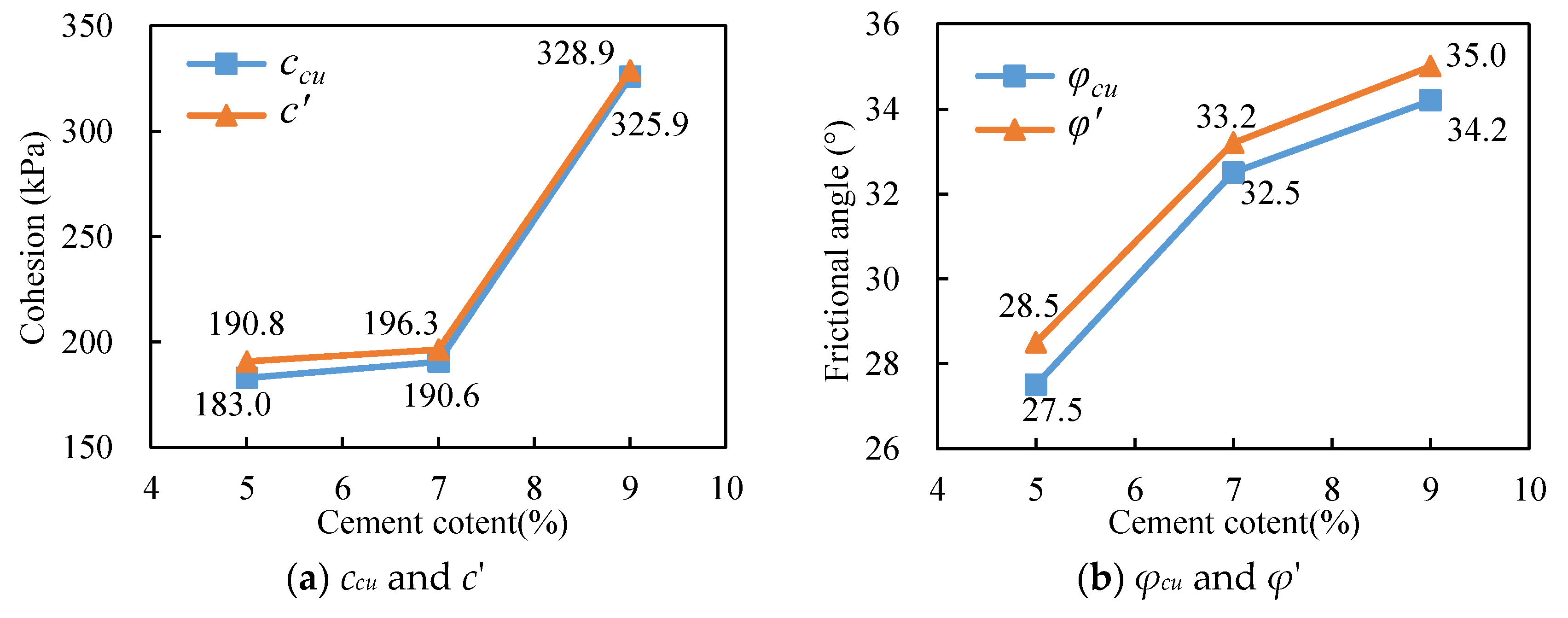

Figure 5 shows the effect of cement content on the shear strength parameters of waste mud–solidified soil. With the cement content increasing from 5% to 9%, the cohesion

ccu of waste mud–solidified soil increased from 183.0 kPa to 325.9 kPa (by 78.09%) and the friction angle

φcu increased from 27.5° to 34.2° (by 24.36%). This result also shows that the shear strength of waste mud–solidified soil increased with increasing cement content within a certain range.

3.3. Compression coefficient

The results of the compression test are shown in

Figure 6. The void ratio of waste mud–solidified soil under the three cement contents decreased with increasing surrounding pressure

p. The void ratio of waste mud–solidified soil was the largest with a cement content of 7%, and lowest with a cement content of 9%. According to the data in

Figure 6, the calculated compression coefficients of waste mud–solidified soil with cement contents of 5%, 7%, and 9% were 2.24 × 10

−3, 1.50 × 10

−3, and 1.04 × 10

−3 kPa

−1. With increasing cement content from 5% to 9%, the compression coefficient decreased, which shows that the compressibility of the waste mud–solidified soil decreased with cement content.

3.4. Dynamic shear modulus and damping ratio

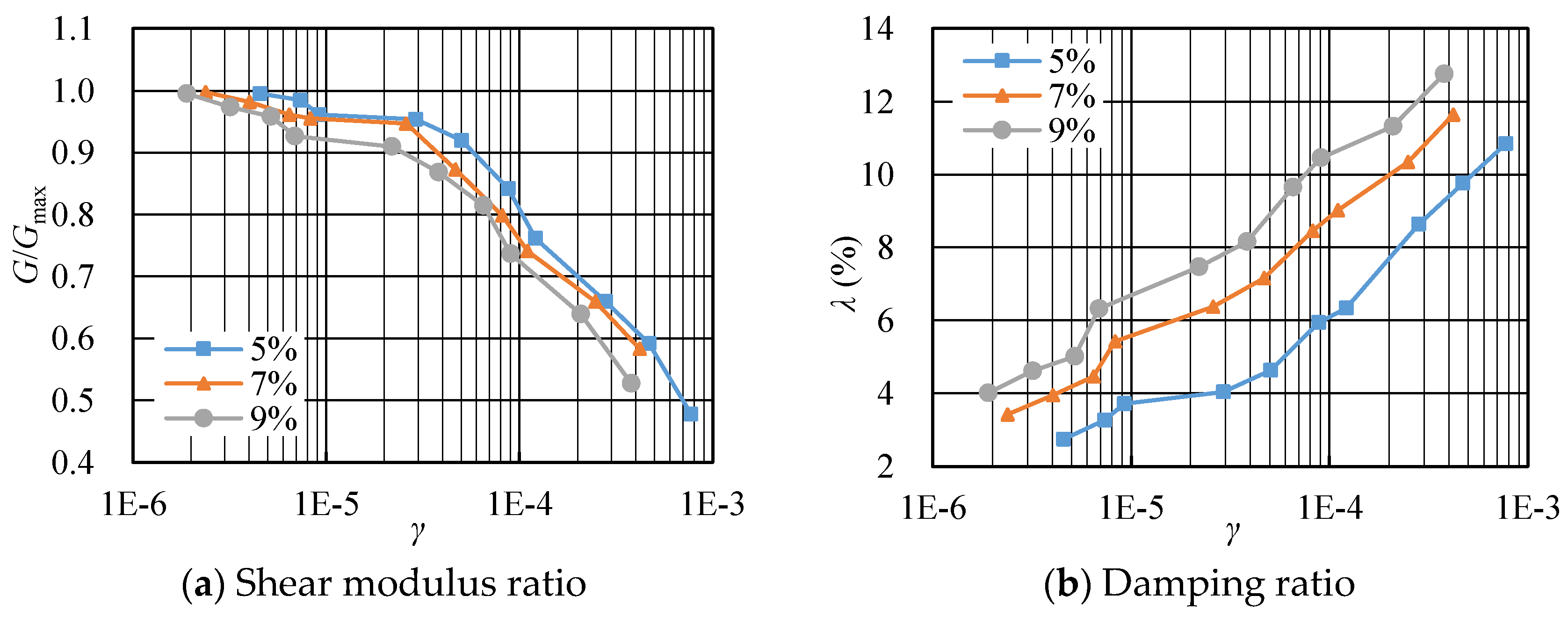

To study the dynamic characteristics of waste mud–solidified soil, resonance column tests were conducted to obtain the curves of shear modulus ratio, damping ratio, and strain of waste mud–solidified soil with three cement contents, as shown in

Figure 7. With the same shear strain, a higher cement content resulted in a smaller shear modulus ratio and larger damping ratio. With increasing shear strain, the shear modulus ratio of the waste mud–solidified soil at the three cement contents gradually decreased. In the smaller range of shear strain from 1 × 10

−6 to 1 × 10

−5, the decay rate of the shear modulus ratio was relatively slow, but the curve gradually steepened with increasing shear strain and the decay rate also increased significantly. The relationship between damping ratio and shear strain was opposite from the relationship between the shear modulus ratio and shear strain. In the smaller range of shear strain from 1 × 10

−6 to 1 × 10

−5, the increasing rate of the damping ratio was relatively slow; however, with increasing shear strain, the curve gradually steepened and the increasing rate also increased significantly.

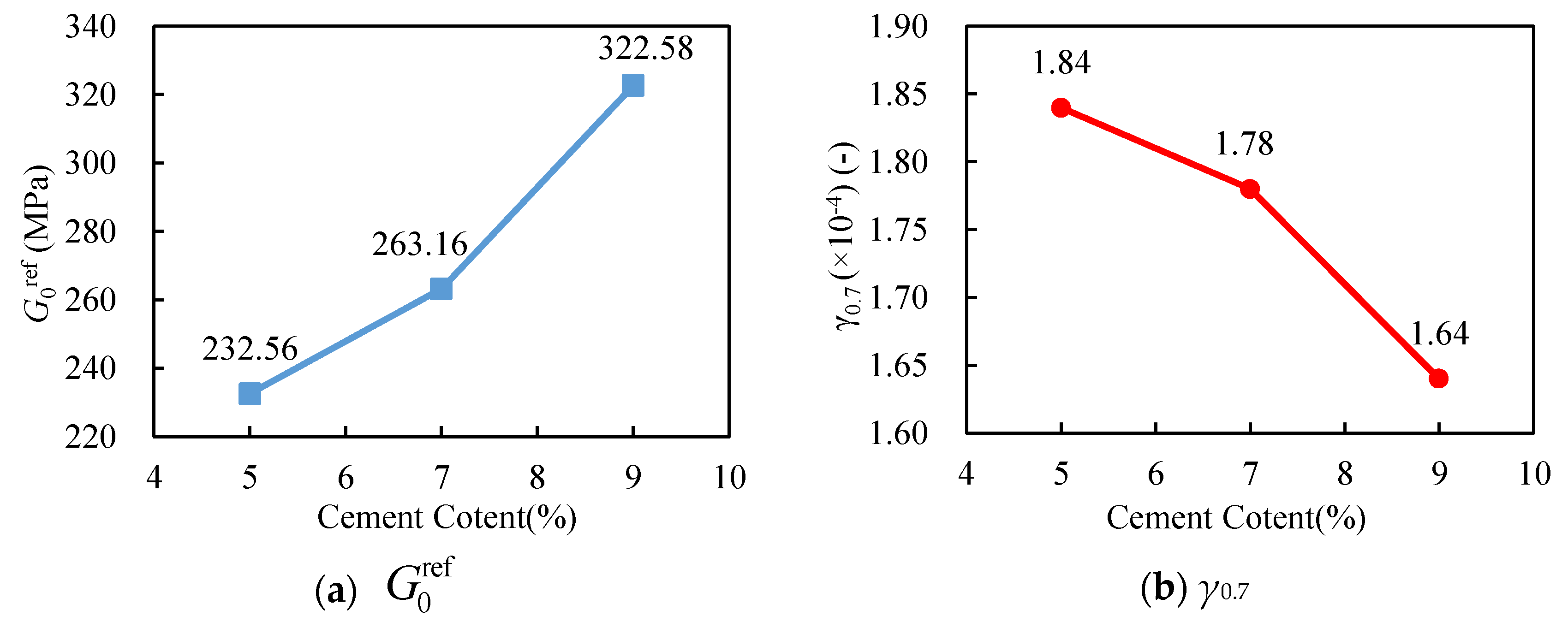

Using the data in

Figure 7, the initial dynamic shear modulus

and the shear strain corresponding to a shear modulus decay to 70% of the initial shear modulus

γ0.7 were calculated; these are shown in

Figure 8. The initial dynamic shear modulus of the waste mud–solidified soil with three cement contents (5%, 7%, 9%) were 232.56, 263.16, and 322.58 MPa, respectively. With the cement content increasing from 5% to 9%, the

increased by 38.71%. The

γ0.7 of the waste mud–solidified soil at the three cement contents were 1.84 × 10

−4, 1.78 × 10

−4, and 1.64 × 10

−4, respectively. With the cement content increasing from 5% to 9%, the

γ0.7 decreased by 10.87%.

4. Discussion

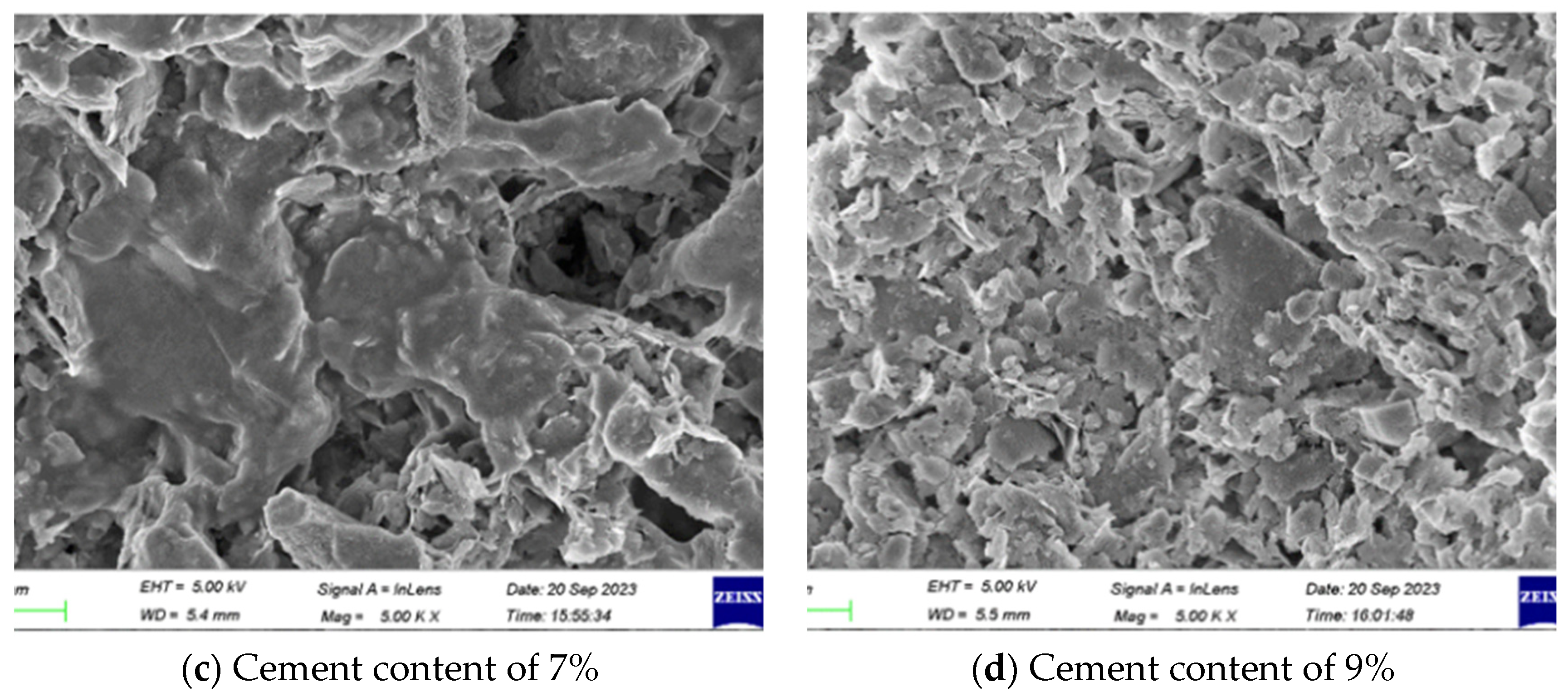

Figure 9 shows the SEM images (5000× magnification) of the undisturbed sample of waste mud and the solidified soil specimens with various cement contents. The particle distribution of the undisturbed soil sample is relatively loose with irregular arrangement of soil particles, the pores between particles are relatively large, the pore sizes between particles vary, and the pore distribution is irregular; this results in diverse shapes of soil units and an unstable soil structure prone to damage. In contrast, the microscopic structure of the solidified soil tends to be more regular. The solidified soil particles no longer exhibit a loose state but form relatively regular block-like structures. The connections between soil particles are mainly through large soil particles and a small amount of fine particles. The sample with 9% cement content exhibited a significant presence of gel-like substances on the surface, while lower cement content had a lower amount of gel-like substances. This indicates that the mineral components in the cement are undergoing hydration reactions with the waste mud soil and are forming new crystals; therefore, the cement-solidifying agent exhibits a good solidification effect.

The products of the cement hydration reaction fill in the gaps between soil particles, and at higher cement content, there are a smaller number and smaller size of gaps in the entire soil sample. The hydration products of cement also include a large number of ions, which undergo chemical reactions with the external electric layer of soil particles, generating colloids with coagulation-promoting effects. When the cement content is low, there are fewer bonding products and fewer effective bonds established between clay particles, resulting in slow strength growth. With an increased cement content, there is a significant increase in the bonding material between clay particles, establishing more bonding and promoting the firm bonding of soil particles, which results in a significant increase in soil strength.

Figure 10 displays the XRD spectra of samples under different conditions. According to the analysis from the Jade software, the peak values correspond to the potentially existing phases. The primary components of the waste mud are SiO

2, with predominant phases being quartz and calcium feldspar. Other components include GaPO

4, AlPO

4, SiS

2, PbS

2O

6, AS

2O

6, and C

4H

8N

2O

2. The main component of the solidified soil is also SiO

2, but in significantly reduced proportions. Other components include AlPO

4, SiS

2, PbS

2O

6, Al

2Mg

4(OH)

12(CO

3)(H

2O)

3, and CaAl

2Si

2O

8. After solidification, the specimens produced diffraction peaks for C–S–H gel and calcium aluminate hydrate. The undisturbed soil contains a large amount of SiO

2 but a higher proportion of low quartz, which is the primary reason for the lower strength of the undisturbed soil. After the cement solidification reactions, the structure of SiO

2 undergoes changes, with a significant reduction in low quartz content and the formation of a harder quartz. Although both are forms of quartz, their different elemental arrangements have a significant impact on structural strength. With increasing cement content, the production of gel products from hydration reactions increases and the content of AlPO

4 in the solidification reaction also increases. The generated gel and crystals play a role in bonding and filling within the soil, resulting in a solidification effect on the mud. This significantly enhances the strength of the solidified soil.

5. Conclusions

In this study, unconfined compressive strength tests, consolidated undrained shear triaxial tests, consolidation compression tests, and resonance column tests were conducted to investigate the road performance of waste mud–solidified soil. XRD and SEM tests were used to reveal the solidification mechanism of waste mud. The following conclusions were obtained:

Adding 5% cement to waste mud with an initial moisture content of 40% and curing for 3 days resulted in an unconfined compressive strength of 304.8 kPa. When 9% cement was added, the unconfined compressive strength increased by more than 100%. When the curing time was extended from 3 days to 28 days, the unconfined compressive strength of the waste mud–solidified soil increased by approximately 70%. However, when the initial moisture content increased from 40% to 60%, the unconfined compressive strength decreased by approximately 50%.

When the cement content increased from 5% to 9%, the cohesion and friction angle of the waste mud–solidified soil increased from 183.0 kPa to 325.9 kPa (78% increase) and the friction angle increased from 27.5° to 34.2° (24% increase). In addition, the compression coefficient decreased by nearly 55%, the initial dynamic shear modulus increased by approximately 38%, and the shear strain corresponding to a shear modulus decay to 70% of the initial shear modulus γ0.7 decreased by nearly 11%. This indicates that with an increase in cement content, the shear strength of the waste mud–solidified soil improved and its compressibility decreased.

The microscopic test results show that samples with higher cement content had more cementitious products generated by the hydration reactions, especially AlPO4. The bonding substances between soil particles significantly increased, which had a bonding and filling effect on soil particles and promoted firm adhesion of soil particles. Therefore, the strength of waste mud–solidified soil significantly increased while its compressibility decreased.

Author Contributions

Data curation, Yan Tang, Han Jiang, Zide Yang and Shiyao Xiong; Funding acquisition, Yan Tang and Gaofeng Xu; Investigation, Shi Shu; Methodology, Han Jiang, Zide Yang and Shiyao Xiong; Project administration, Gaofeng Xu; Resources, Yan Tang; Supervision, Shi Shu; Writing – original draft, Han Jiang and Zide Yang; Writing – review & editing, Shi Shu. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the financial support from the Science and technology project of Zhejiang Huadong Geotechnical Investigation & Design Institute CO, Ltd. (no. ZKY2022-HDJS-02-14) and the National Key R&D Program of China (no. 2022YFC3202705).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ryu, Y.M.; Kwon, Y.S.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, I.M. Slurry Clogging Criteria for Slurry Shield Tunneling in Highly Permeable Ground. KSCE J. Civil Eng. 2019, 23, 2784–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, R.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lu, J. An Experimental Study on the Treatment of Engineering Waste Slurry by Using Agent Conditioning-Combined Pressure Filtration. Geofluids 2022, 1057244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Mao, T.; Li, N.; Jia, L.; Zhang, F.; Wang, W. Characterization of Short-term Strength Properties of Fiber/Cement-Modified Slurry. Adv. Civil Eng. 2019, 3789403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, K.; Zeng, G.; Shu, B.; Luo, D. Study on the Performance and Solidification Mechanism of Multi-Source Solid-Waste-Based Soft Soil Solidification Materials. Materials, 2023, 16, 4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, W.; Liu, D.; Song, H.F.; Pu, G.J. Development and Experimental Study on Environmental Slurry for Slurry Shield Tunneling, Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 216, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, F.; Wang, D.; Du, J.; Song, H.; Wang, Y.L.; Lv, H.; Ma, J. Laboratory Study of Flocculation and Pressure Filtration Dewatering of Waste Slurry. Adv. Civil Eng. 2020, 2423071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, B.; Wu, Q.; Qiu, W.; Wang, N. Analysis and Outlook on the Situation of Sand and Stone Mineral Resources in China. Xinjiang Geol. (In Chinese). 2023, 41, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Research on the Application of Tunnel Waste as Subgrade Filler. Archit. Technol. 2023, 54, 1838–1841. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Horpibulsk, S.; Rachan, R.; Suddeepong, A.; Chinkulkijniwat, A. Strength Development in Cement Admixed Bangkok Clay: Laboratory and Field Investigations. Soils Found. 2011, 51, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J.C.; Gao, H.B.; Han, J.G. Study on Test and Practical Application of Solidification Treatment of Wasted Mud. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 477–478, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Cheng, X.; Chen, G. Experimental and field study on treatment waste mud by in-situ solidification. P. I. Civil Eng- Munic. 2018, 173, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.J.; Zheng, Y.L.; Dong, C.Q.; Zheng, J.J. Strength behavior of dredged mud slurry treated jointly by cement, flocculant and vacuum preloading. Acta Geotech. 2022, 17, 2581–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Su, X.; Zheng, J. The Curing and Strength Properties of Highly Moist Waste Mud from Slurry Shield Tunnel Construction. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Hu, F.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang. Experimental Study on Preparation of Unburned Ceramsite from Waste Mud. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Water Resource and Environment. WRE 2022. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Weng, CH., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 341. [Google Scholar]

-

GB/T 50123-2019; Standard for Geotechnical Test Method. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).