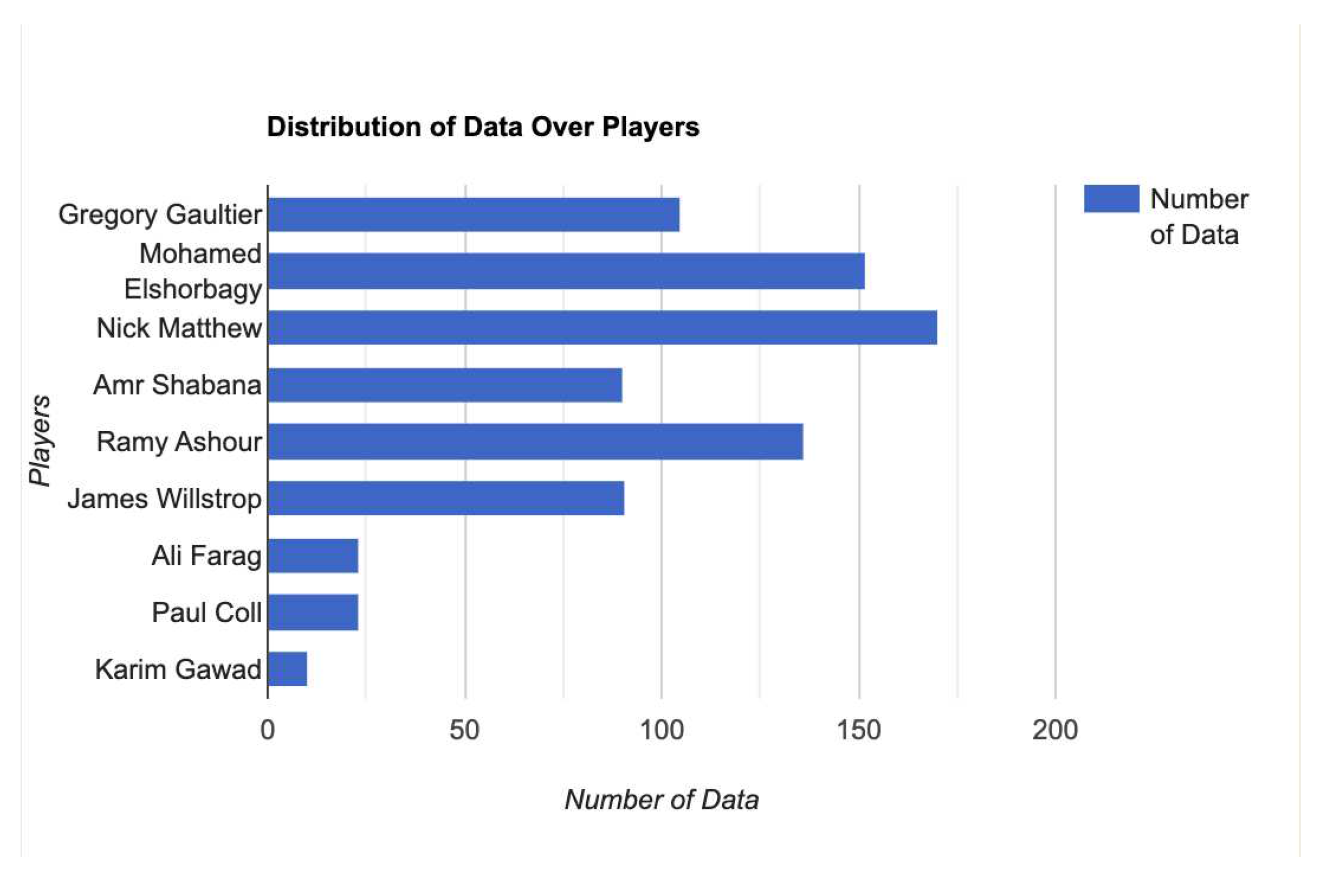

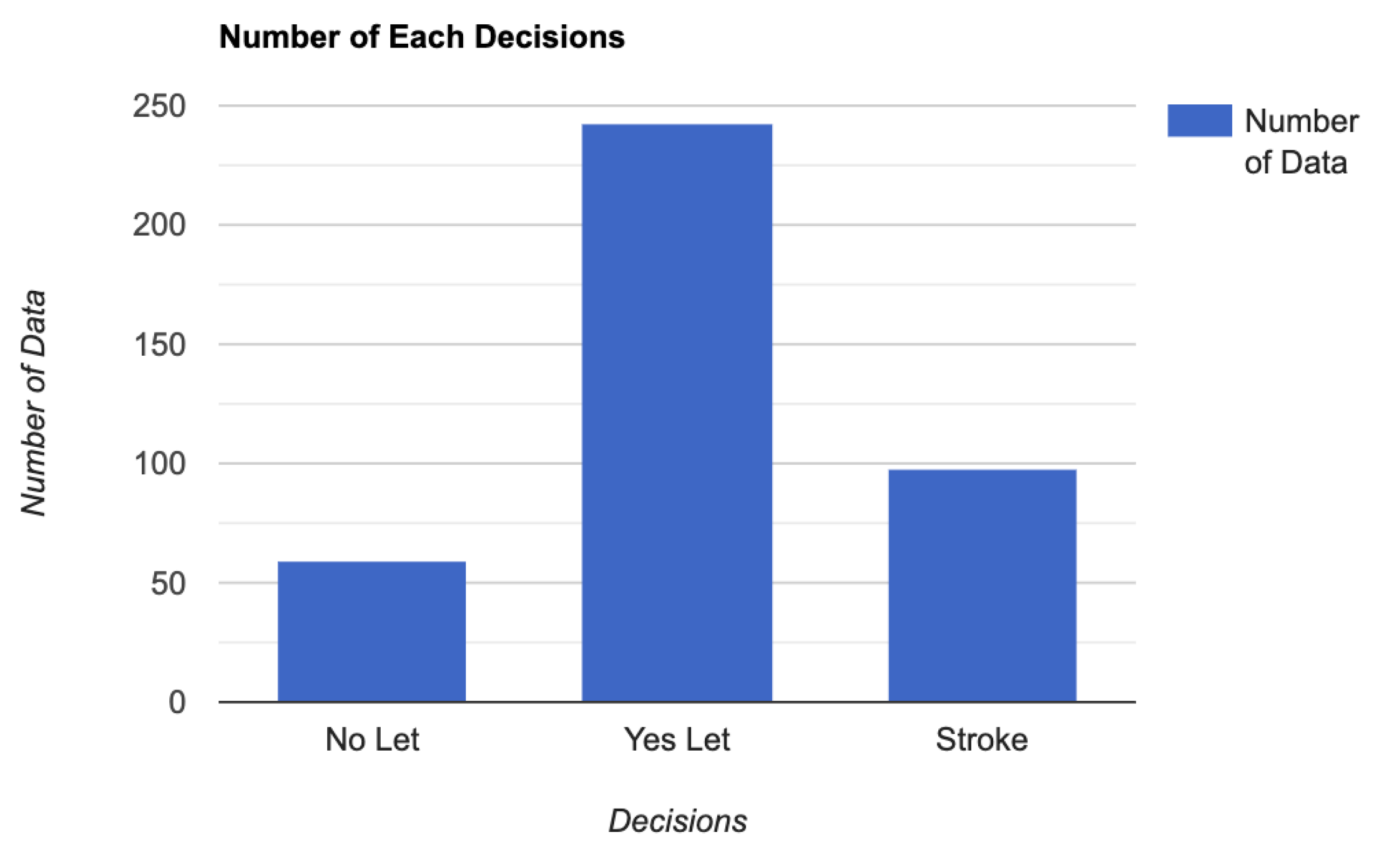

3.5. Modified Data Points

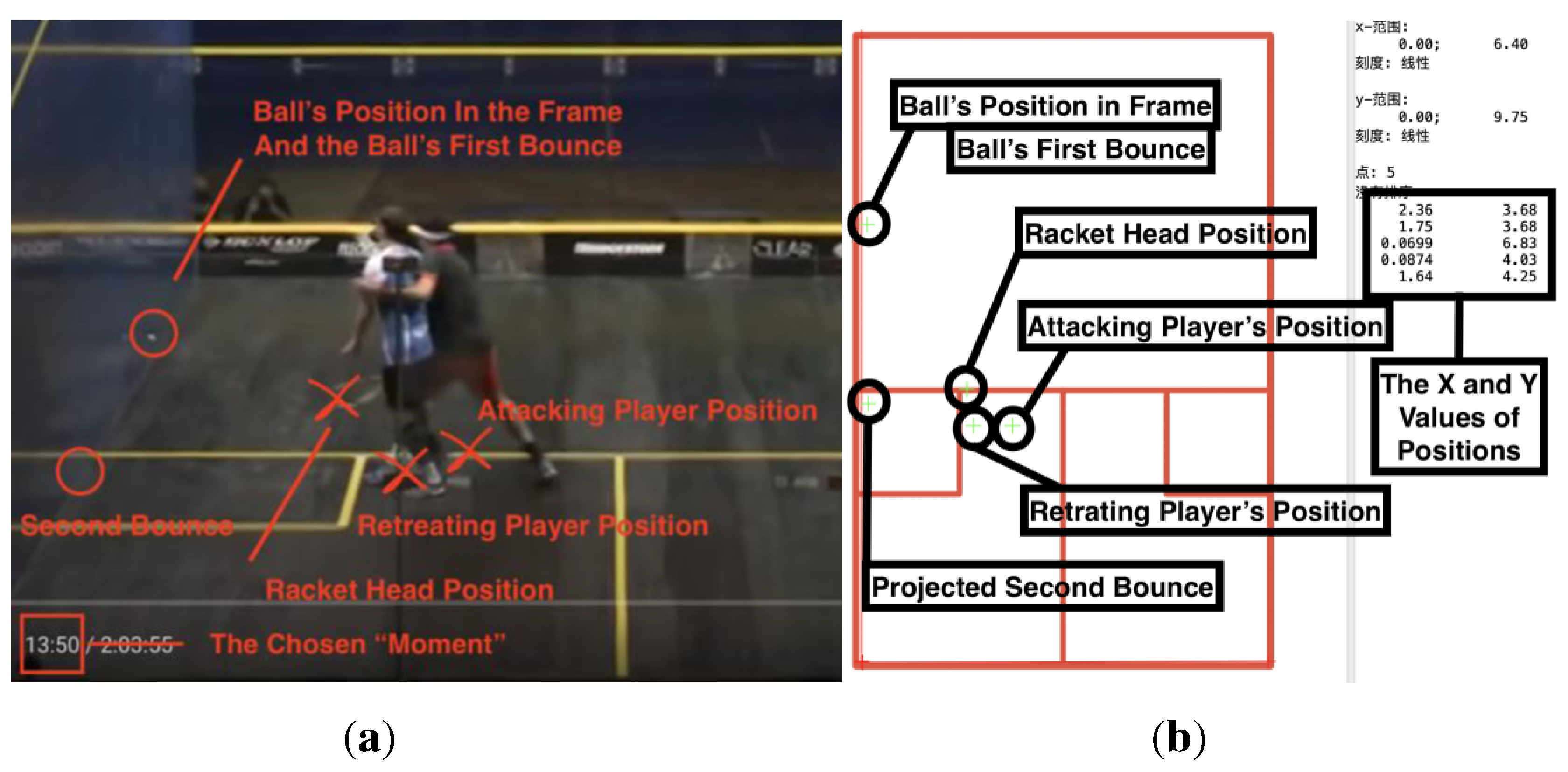

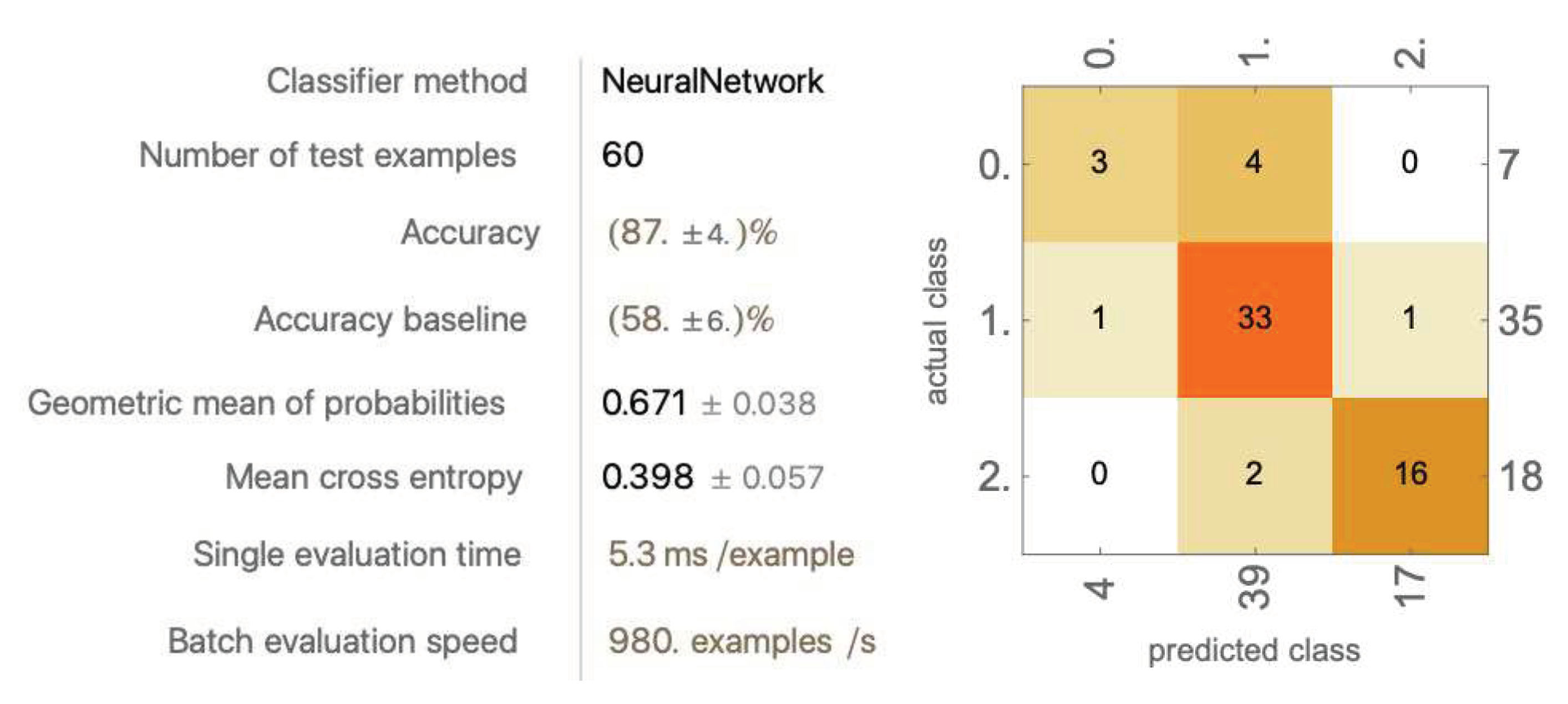

We hypothesized that the initial six data components (or, the primitive data components) would not be enough to achieve the accuracy needed in real-life squash refereeing. There are more than six factors that decide what should be the right decision for an interference. Therefore, we decided to calculate a second layer of data using the primitive components we had acquired. The second layer of data components may be able to provide more insights into why and how a situation is considered one of the three decisions. More specifically, we used the primitive data components and calculated nine more values which we think can provide useful information. The second layer of data components is explained below:

3.5.1. Distance of Attacking Player (AP) to Retreating Player (RP)

The distance between two players is calculated through the Pythagorean theorem. This value is included because how close the players are may affect how the decision is made, especially in situations where no physical contact is presented but the ability to play the ball is impeded. This value may provide less useful information in cases where physical contact occurs, as in those situations the distance tends to be short as the players’ bodies have made contact.

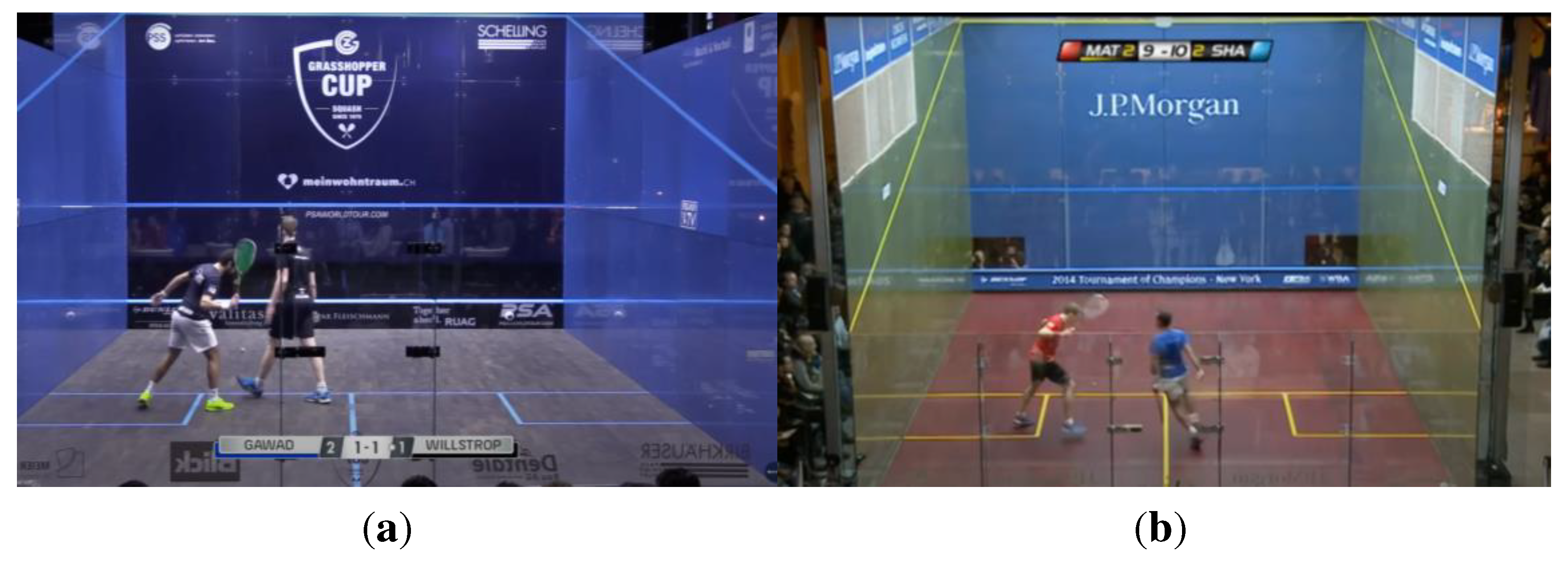

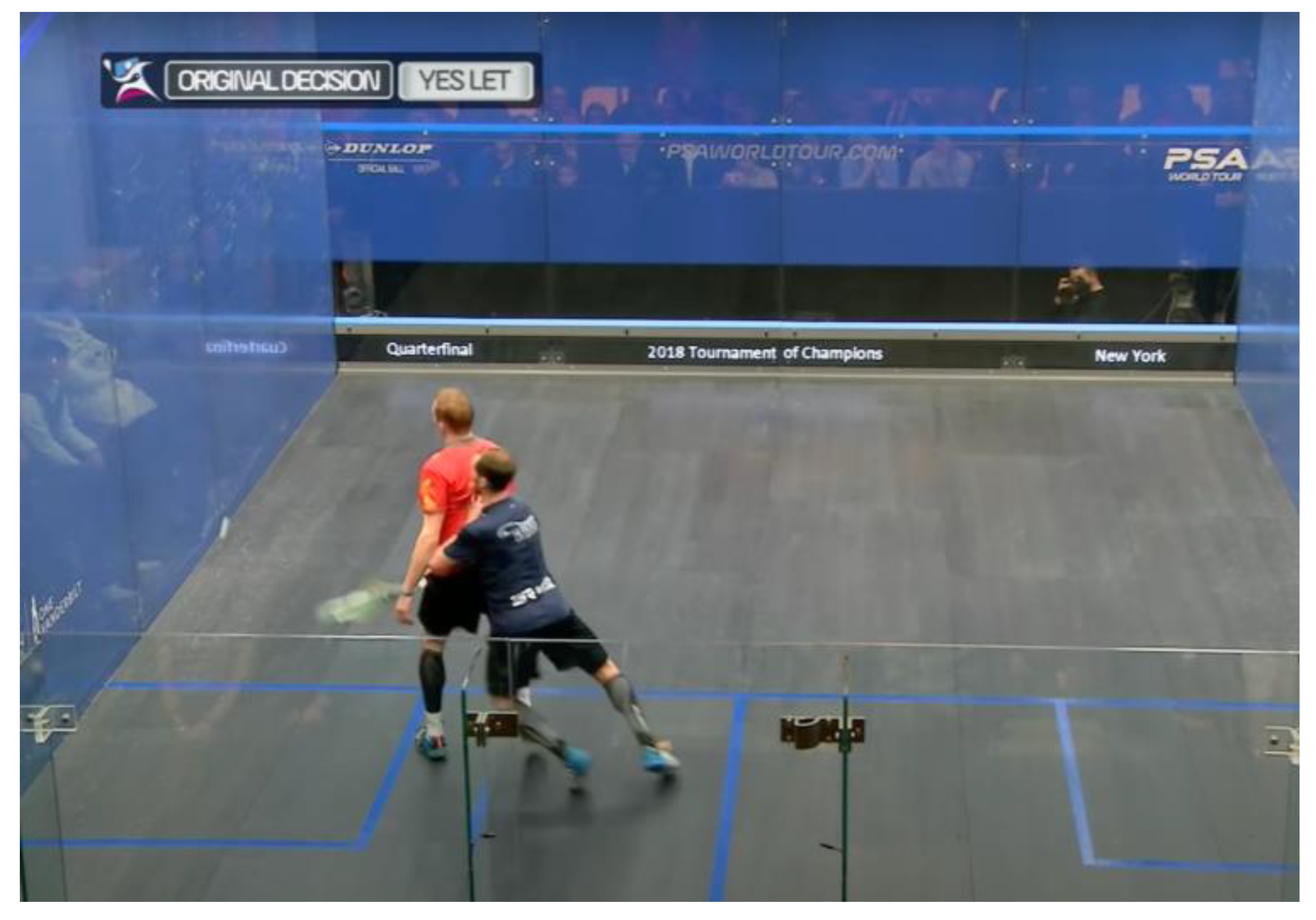

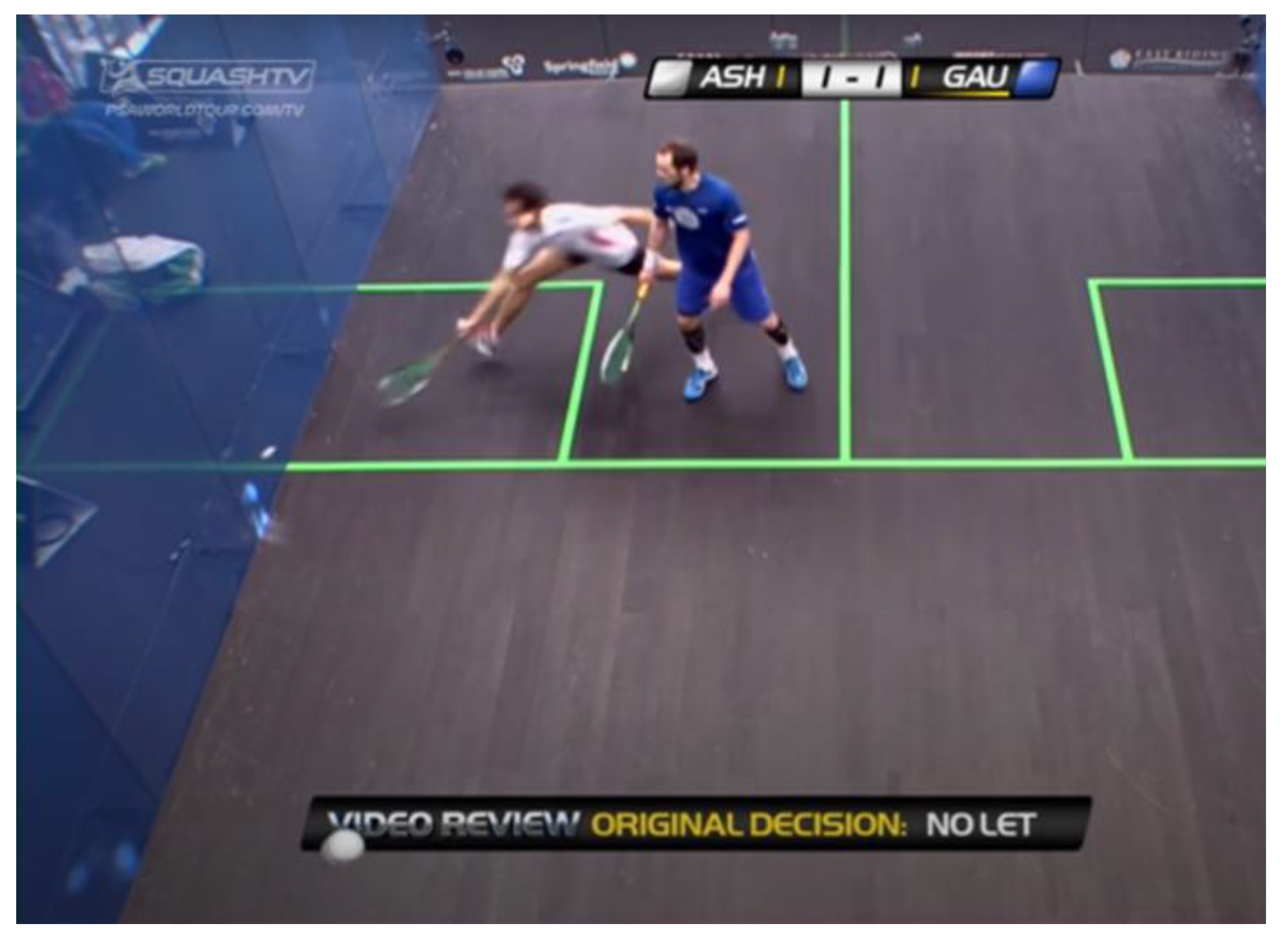

Figure 10.

(

a) Data #402, Gawad/Willstrop 2018 Grasshopper 1:02:48 Stroke [

23]. (

b) Data #92, Matthew/Shabana 2014 Tournament of Champions (ToC) 1:35:10 Yes Let [

24].

Figure 10.

(

a) Data #402, Gawad/Willstrop 2018 Grasshopper 1:02:48 Stroke [

23]. (

b) Data #92, Matthew/Shabana 2014 Tournament of Champions (ToC) 1:35:10 Yes Let [

24].

The above two cases are a great demonstration of how distance between players can cause the decision to change. In both scenarios, the player location and the ball locations are similar, yet the former is decided a Stroke and the latter a Yes Let. This is because in the first scenario, the two players are very closely positioned. If the attacking player was going to play the ball, he would likely strike his opponent. Therefore, a stroke is awarded to the attacking player. In the second scenario, there is more space between the two players, and the attacking player would have space to hit the ball without hitting his opponent. Therefore, the referees deemed the situation as Yes Let.

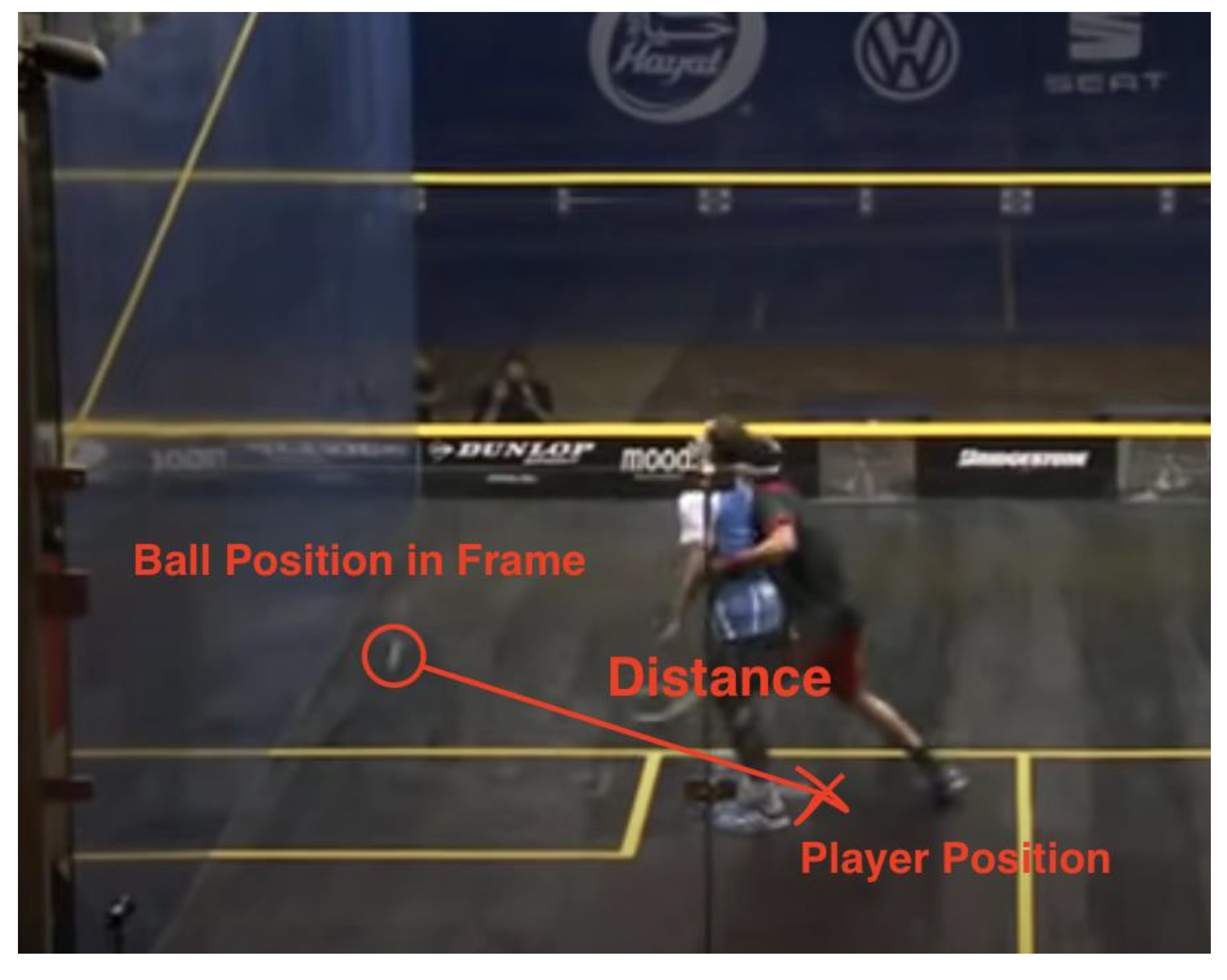

3.5.2. Distance of Attacking Player to Ball Position in Frame

The distance of AP to the ball provides useful information in making decisions. If the ball is close to the AP, there is more possibility of the decision being a stroke; the further the ball is from the AP, the higher the chance of the decision being a No Let. The distance can be a good indicator of the attacking player’s ability to play the ball. There are fewer chances of No Lets if the attacking player is ready to play the ball instead of being on the way to the ball.

However, the ball position may not be a good indicator of where the player will play the ball. In situations where the ball travels to the back of the court and the interference happens when the ball is in the middle, the distance of AP to the ball can provide information about where the player will be playing the ball. In situations where the ball stays up in the court, the distance of AP to the ball can be misleading because the ball position in frame will travel towards the player and end at the second bounce position. In this case, where the player will play the ball is closer to the player than the ball position in frame, and the distance of AP to the ball is exaggerated.

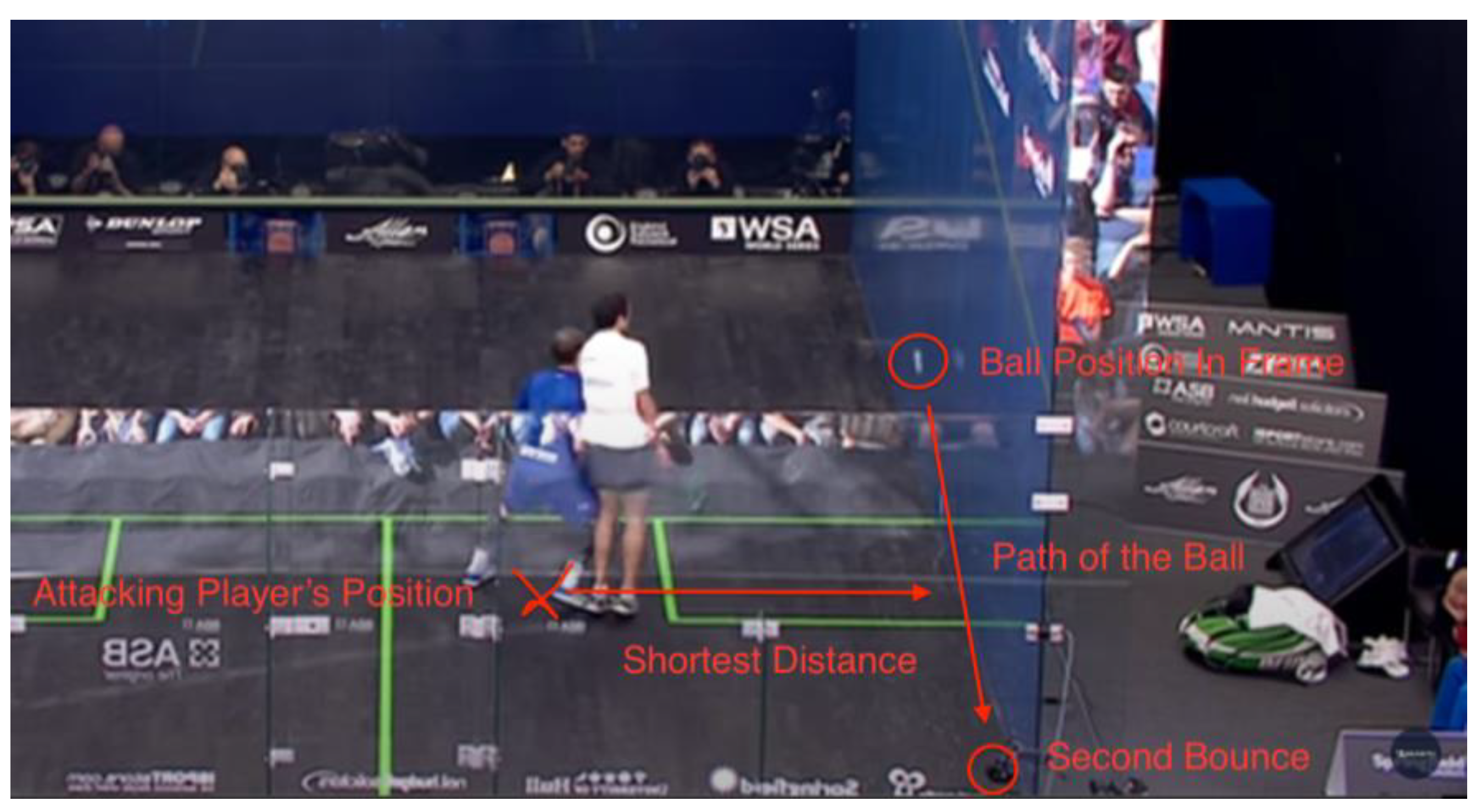

Figure 11.

Data #4, Gaultier/Elshorbagy 2014 ElGouna 19:57 YesLet [

17].

Figure 11.

Data #4, Gaultier/Elshorbagy 2014 ElGouna 19:57 YesLet [

17].

The above situation is a case in which this information can be a useful tool, as the ball position in frame is close to where the player is going to play it. The distance therefore provides insights into the player’s ability to get to the ball.

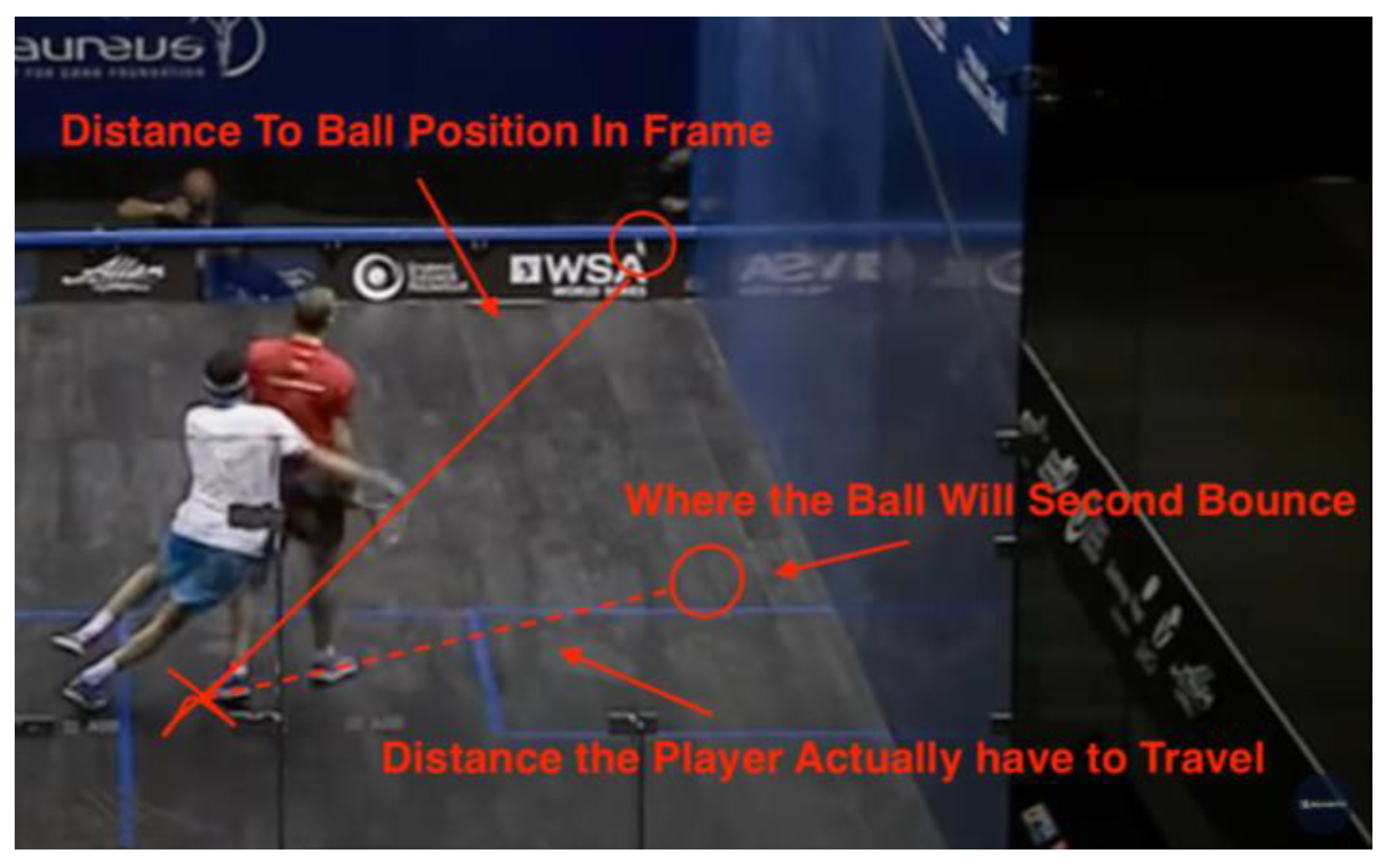

Figure 12.

Data #39, Matthew/Elshorbagy 2014 British Open 49:11 Yes Let [

25].

Figure 12.

Data #39, Matthew/Elshorbagy 2014 British Open 49:11 Yes Let [

25].

This situation is a case in which the information can be misleading. The ball travels towards the attacking player, therefore, the ball position in frame is a lot further than the distance the attacking player actually has to travel.

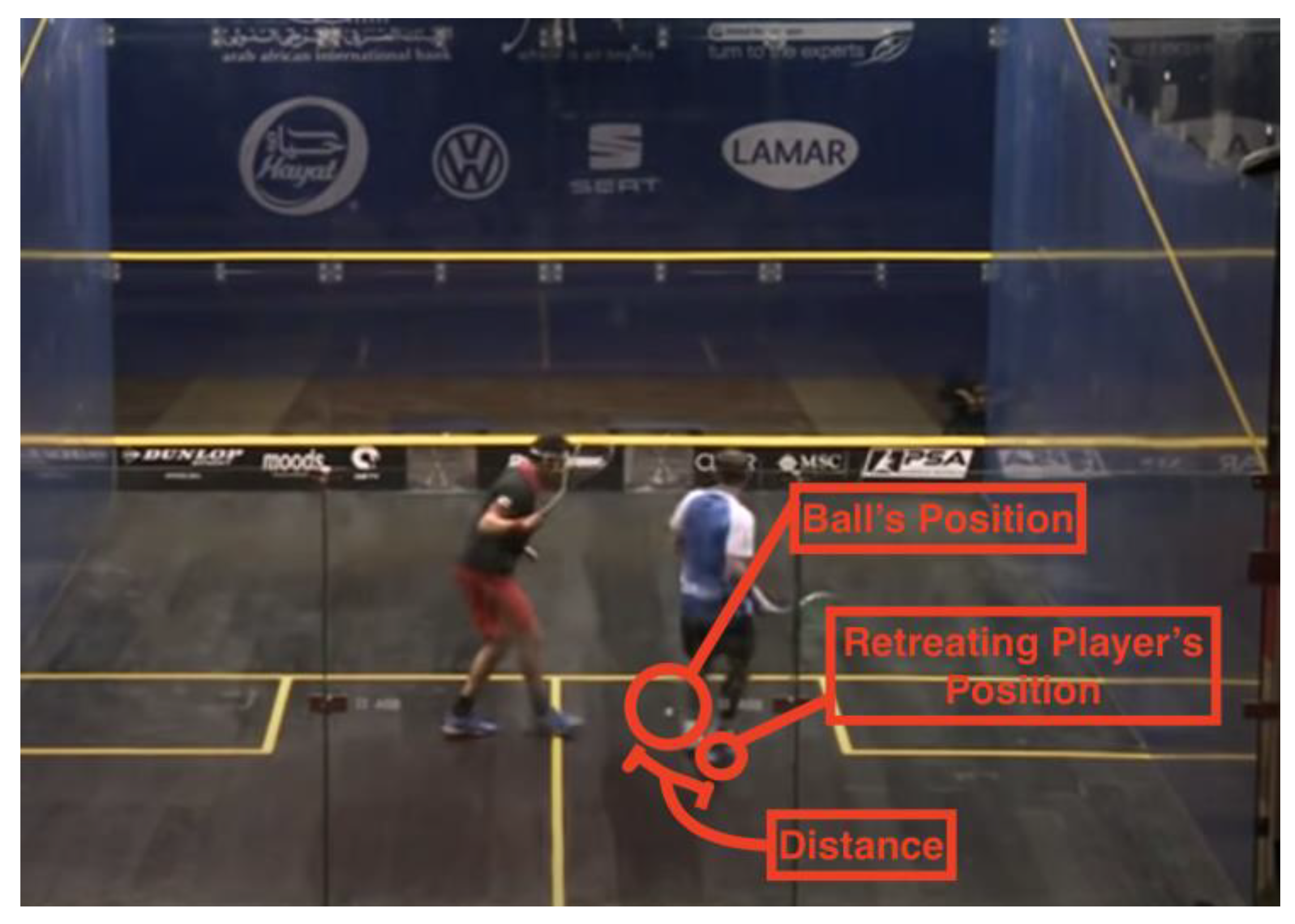

3.5.3. Distance of Retreating Player to Ball Position in Frame

The distance of the retreating player to the ball can provide information about how much the RP is blocking access to the ball. If the RP is away from the ball, the situation should lean away from a stroke. If the RP is right next to the ball, it shows that the RP is blocking access to the ball, which would push the decision towards a stroke.

Similar to the distance of AP to ball position in frame, this value may not be a good indicator of where the attacking player can play the ball. If the ball position in frame is next to the RP, but the AP is still too far away to play the ball, the situation can be considered a Yes Let or No Let. On the other hand, if the ball position in frame is away from the RP, but it will eventually end next to the RP, the situation can still be considered a Stroke.

Figure 13.

Data #25, Gaultier/Elshorbagy 2014 ElGouna 1:42:50 Stroke [

17].

Figure 13.

Data #25, Gaultier/Elshorbagy 2014 ElGouna 1:42:50 Stroke [

17].

This example shows how the distance of RP to the ball can be a good indicator that the situation is a stroke. In this case, the RP accidentally hits the ball back to himself, and the AP would have hit him had he attempted to swing at the ball. Therefore, because the distance of RP to the ball is small, this situation is considered a stroke.

Figure 14.

Data #364, Shabana/Matthew 2013 World Tour Finals 1:00:33 No Let [

26].

Figure 14.

Data #364, Shabana/Matthew 2013 World Tour Finals 1:00:33 No Let [

26].

This situation shows that the distance of RP to the ball can also be an indicator if the situation is a No Let. In this case, the RP is very far away from the ball, which suggests that the AP created his own interference by going directly at the RP, or the AP could not have reached the ball had there been no interference. In either case, the decision would be No Let.

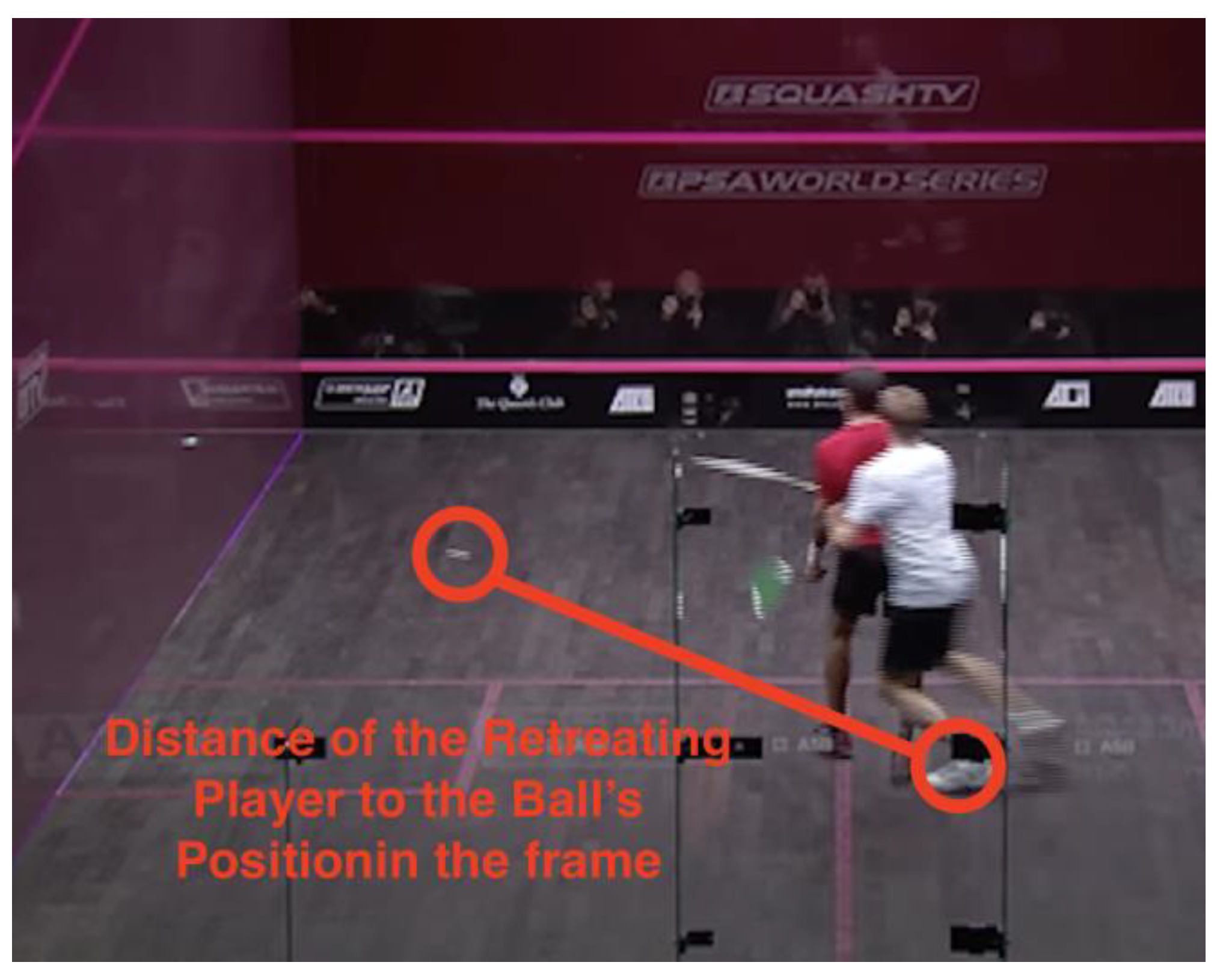

3.5.4. Distance of Attacking Player to Second Bounce

Usually, the referee looks at the second bounce to determine how far away the ball is from the players. By considering the distance of the AP to the second bounce, we can gain information about how much the attacking player has to move before arriving at a position to play the ball. This value can be very straightforward when the ball remains at the front of the court: the closer it gets to the AP, the higher the chance it is a stroke.

However, when the ball travels to the back of the court, at some point the ball is closest to the attacking player, and it will travel away. Had there been no interference, the attacking player would ideally play the ball where it is closest to him instead of following the ball until its second bounce. In this case, the distance of AP to the second bounce position again fails to identify the position where the player is going to play the ball.

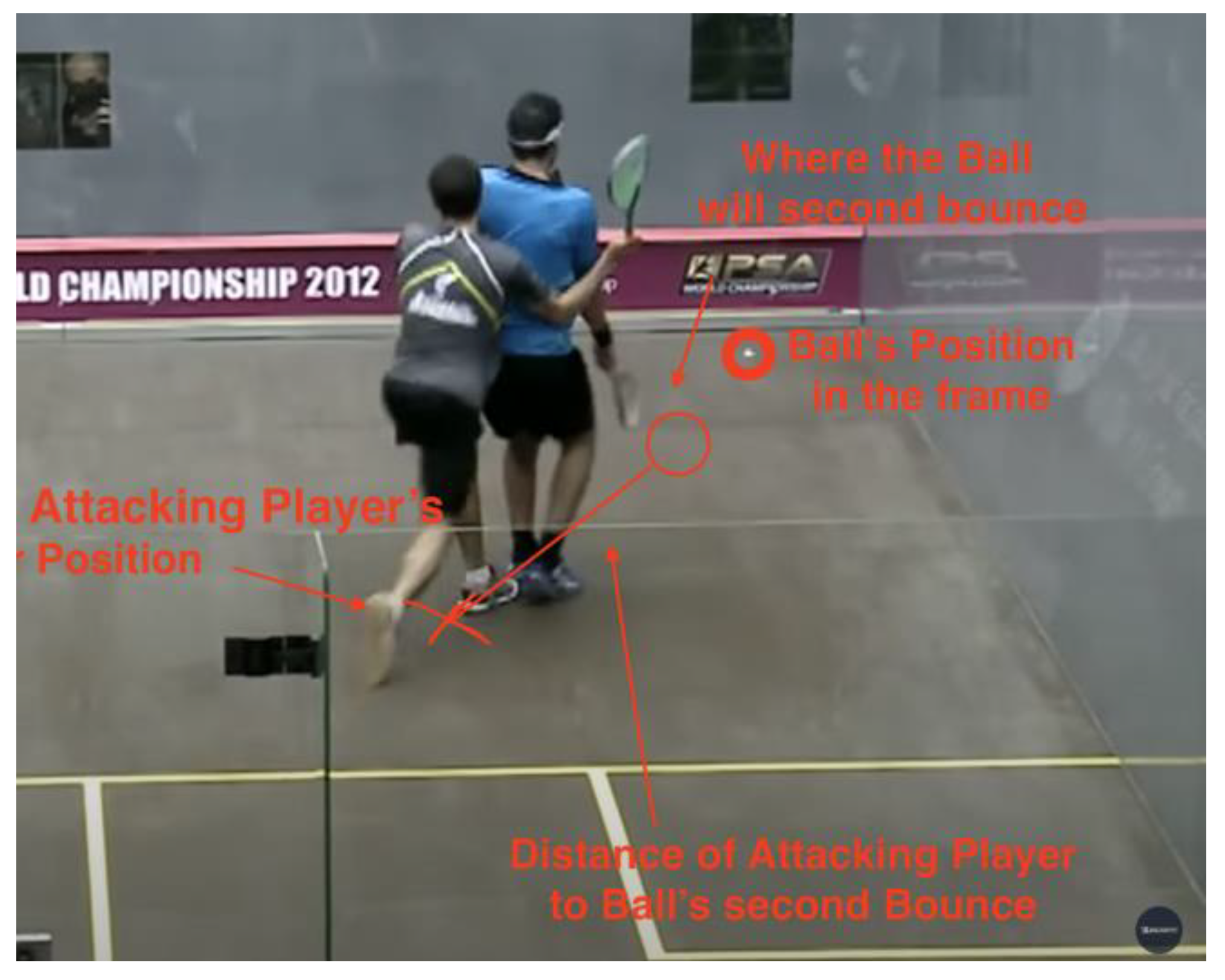

Figure 15.

Data #142, Ashour/Elshorbagy 2012 World Championship 1:30:41 Stroke [

27].

Figure 15.

Data #142, Ashour/Elshorbagy 2012 World Championship 1:30:41 Stroke [

27].

In the case above, the distance of the attacking player to the second bounce supports why the decision is a Stroke. Where the ball lands for its second bounce is really close to the AP, which means the AP could easily play the shot, had there been no interference. Since the retreating player is directly in the way, this is one of the most obvious stroke decisions.

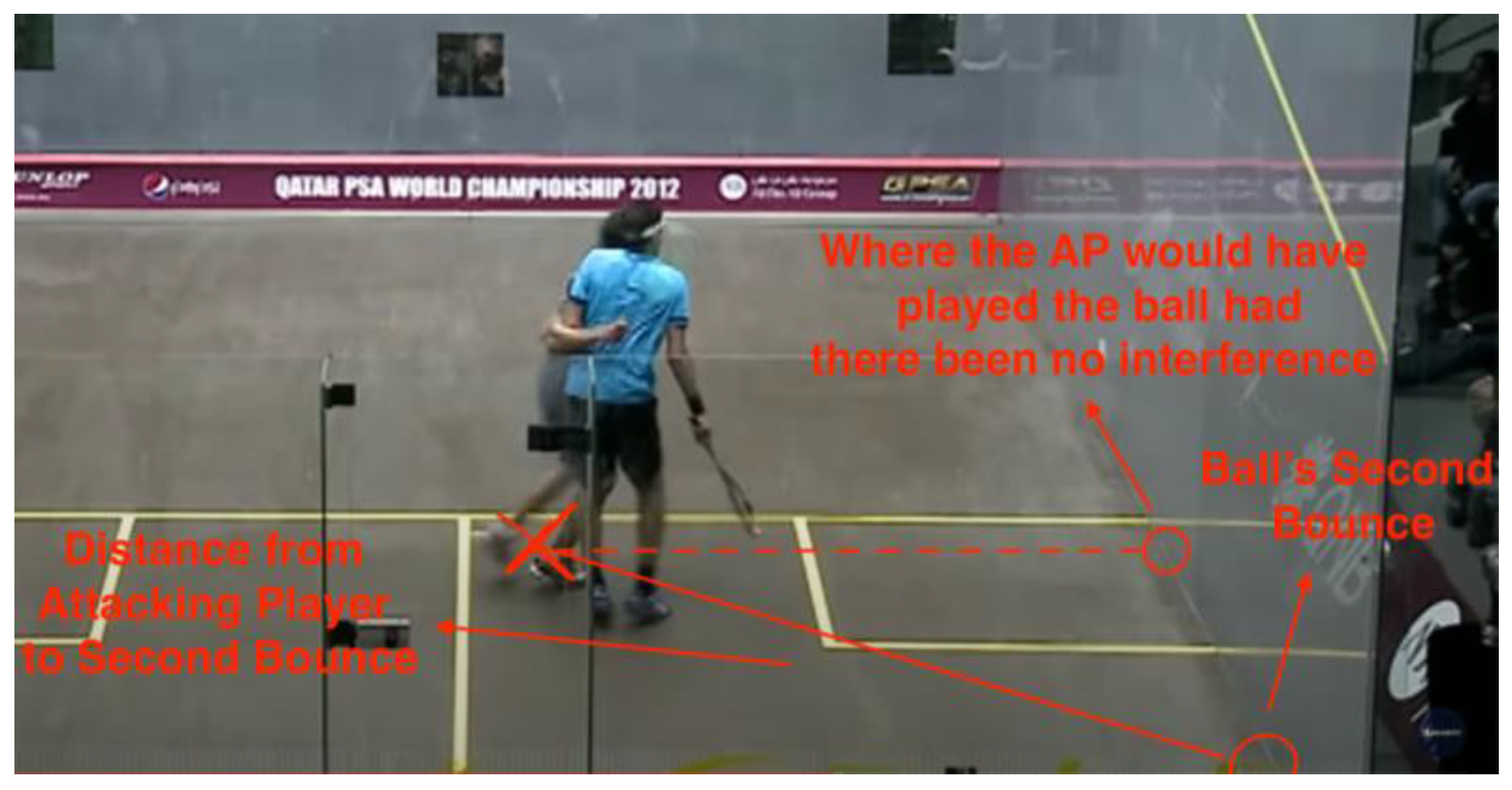

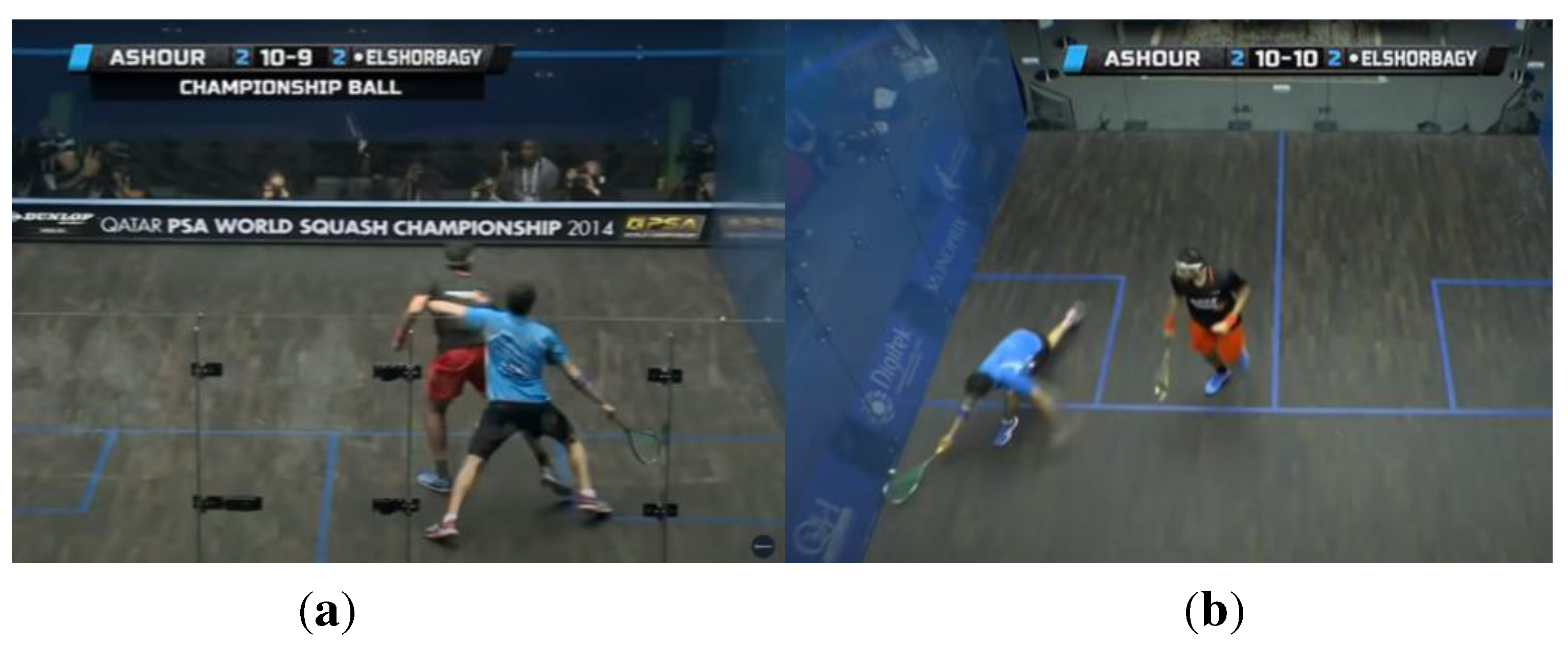

Figure 16.

Data #134, Ashour/Elshorbagy 2012 World Championship 1:13:29 Yes Let [

27].

Figure 16.

Data #134, Ashour/Elshorbagy 2012 World Championship 1:13:29 Yes Let [

27].

This is a case where the distance of the attacking player to the second bounce is an inaccurate representation of the attacking player’s ability to get to the ball. Had there been no interference, the AP would have played the ball around the service box. If we consider the distance to the second bounce, the AP would be unjustly evaluated for his ability to retrieve the ball, since he only has to move to the service box instead of having to move to the back of the court.

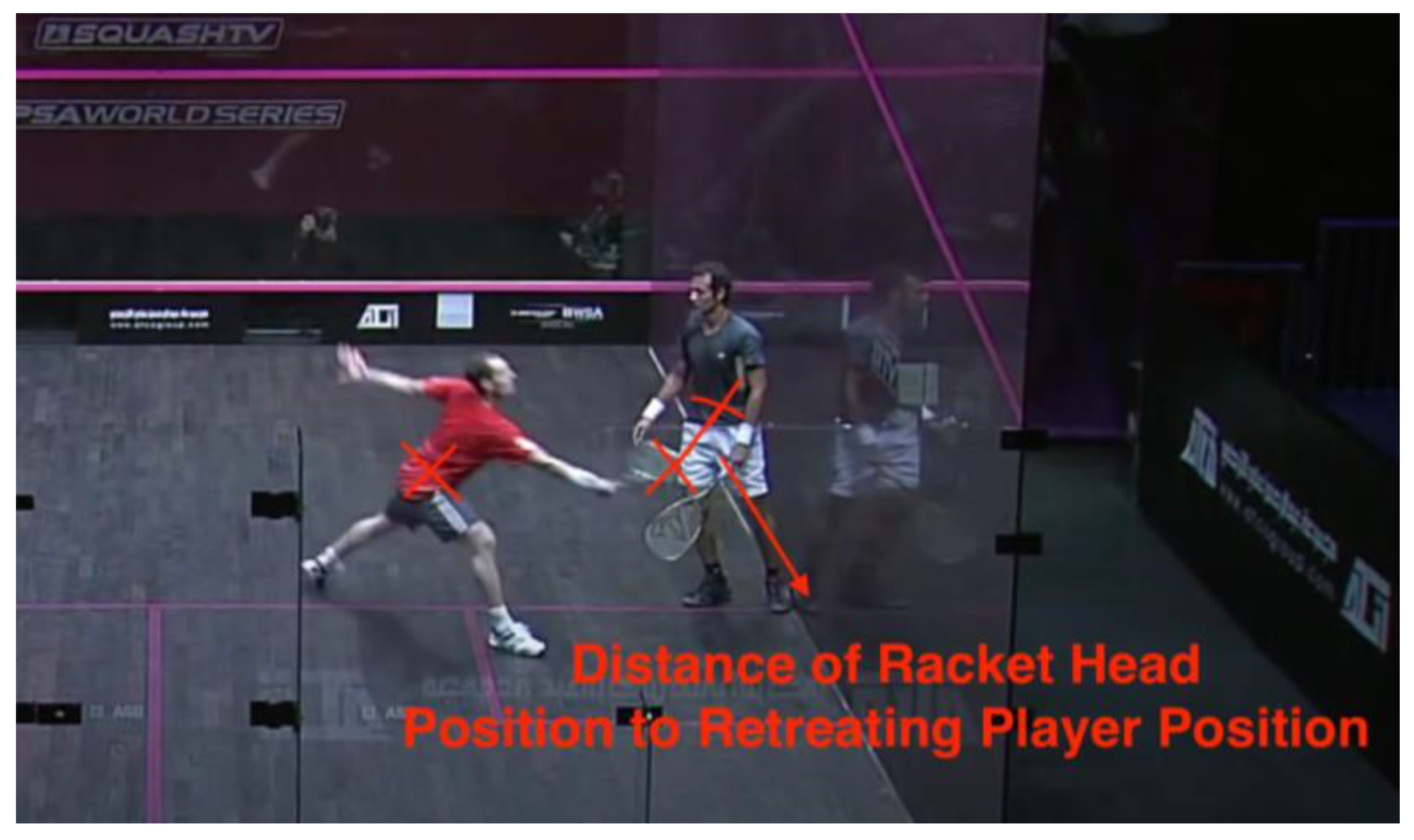

3.5.5. Distance of Racket Head to Retreating Player

If the swing of a player is impeded by the other player and he would have been able to play the ball otherwise, a Stroke would be awarded to the player. The distance of the racket head to the retreating player aims to capture this aspect of decision-making. If the racket head is close to the retreating player and the ball is close to the AP, the situation will likely be a Stroke.

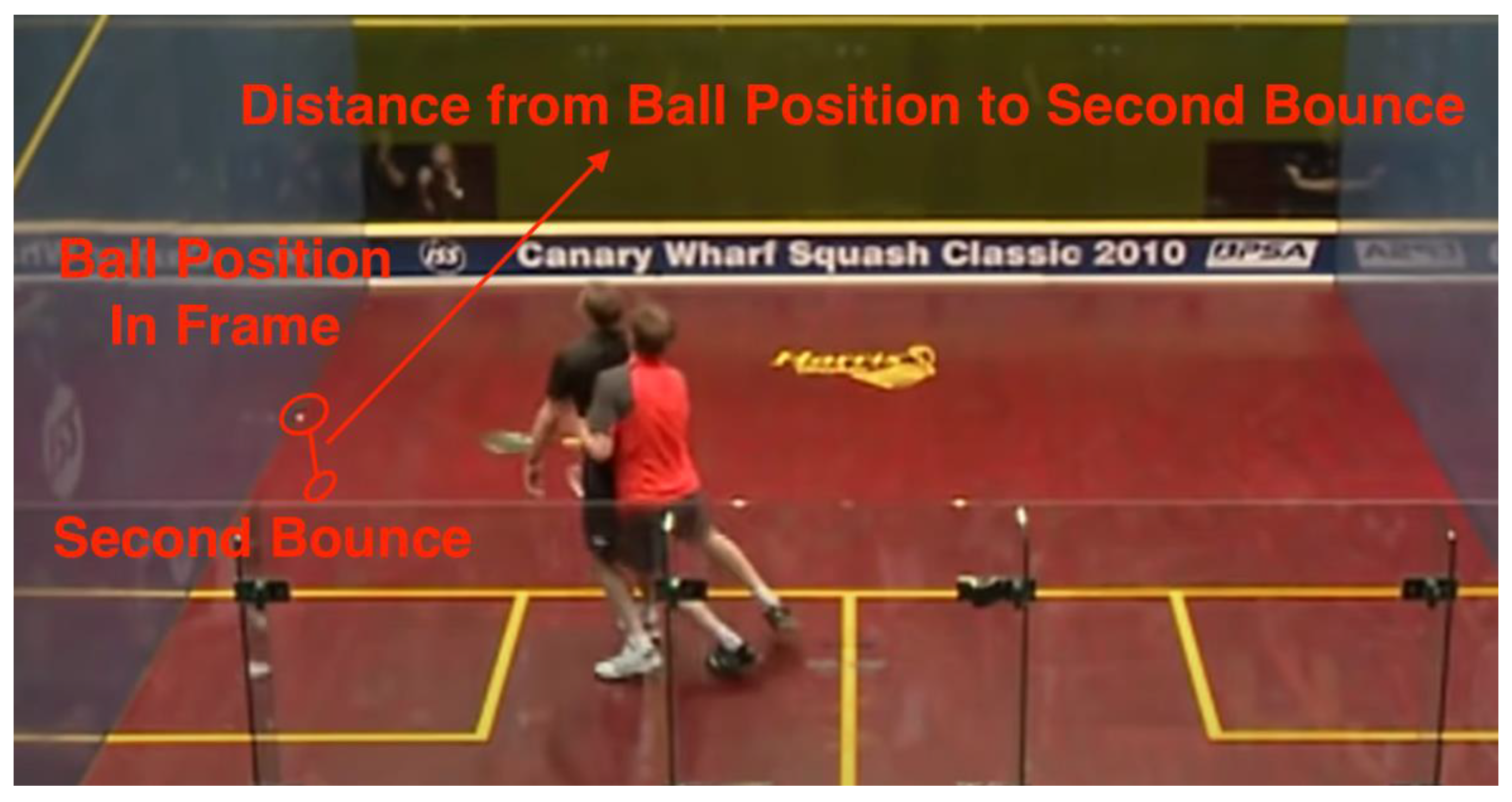

Figure 17.

Data #192, Matthew/Willstrop 2010 Canary Wharf 1:41:18 Stroke [

28].

Figure 17.

Data #192, Matthew/Willstrop 2010 Canary Wharf 1:41:18 Stroke [

28].

This is an example of the racket head being too close to the retreating player, and the referee deemed the situation a stroke. Had the AP swung at the ball, the RP would likely have been hit. After all, this distance provides similar information to the Distance of AP to RP, but we hypothesize that this may provide a more accurate value.

3.5.6. Distance of the Ball Position in Frame to Second Bounce

In making decisions, the referee considers the “quality of shot.” If there is interference, yet the shot is “too good,” the referee makes the decision of No Let. This value aims to present information about how good the ball is. The distance of the ball position in frame to the second bounce shows how far the ball travels before it dies, and therefore indirectly provides information about how much time the player has to retrieve the ball if there has been no interference, or the “time remaining.” If the contact happened and the ball died right away, the AP could not have gotten to the ball, even if there was not any interference. On the other hand, if there is still lots of time until the ball dies after the interference, the situation is likely a Yes Let.

Figure 18.

Data #167 Matthew/Willstrop 2010 Canary Wharf 1:02:50 No Let [

28].

Figure 18.

Data #167 Matthew/Willstrop 2010 Canary Wharf 1:02:50 No Let [

28].

This situation demonstrates how this information can be used to determine No Let. As the ball hits the “nick” on the first bounce (the “nick” is the corner between the floor and the wall. When a ball lands in the nick, energy is taken away and it can die very quickly), the ball stays very short, which leaves no time for the AP to retrieve the shot. Because the distance of ball position to second bounce is short, the referee deemed the situation a No Let, as the AP could not reach the ball even if there was not any interference.

3.5.7. Distance of Racket Head to Ball Position in Frame

This value provides similar information to the distance of the attacking player to the ball position in frame. We included this information because sometimes the reach of the player can be long enough to reach the ball even when their body is more than a meter away. The racket head position may provide more useful information about the attacking player’s ability to play the ball than the attacking player’s position.

Figure 19.

Data #214, Shabana/Gaultier 2011 World Series Finals 33:09 Stroke [

29].

Figure 19.

Data #214, Shabana/Gaultier 2011 World Series Finals 33:09 Stroke [

29].

This case is an example of why the distance of racket head to ball position may provide a better notion of the attacking player’s ability to play the ball than the distance of attacking player to ball position. In this case, the AP’s racket head is very far away from his body. He is fully stretched and can strike a ball that is more than one and a half meters away from him. In this case, simply calculating the distance of the AP to the ball may provide a false sense that the AP is still some distance away from the ball, Therefore, we decided to include this value.

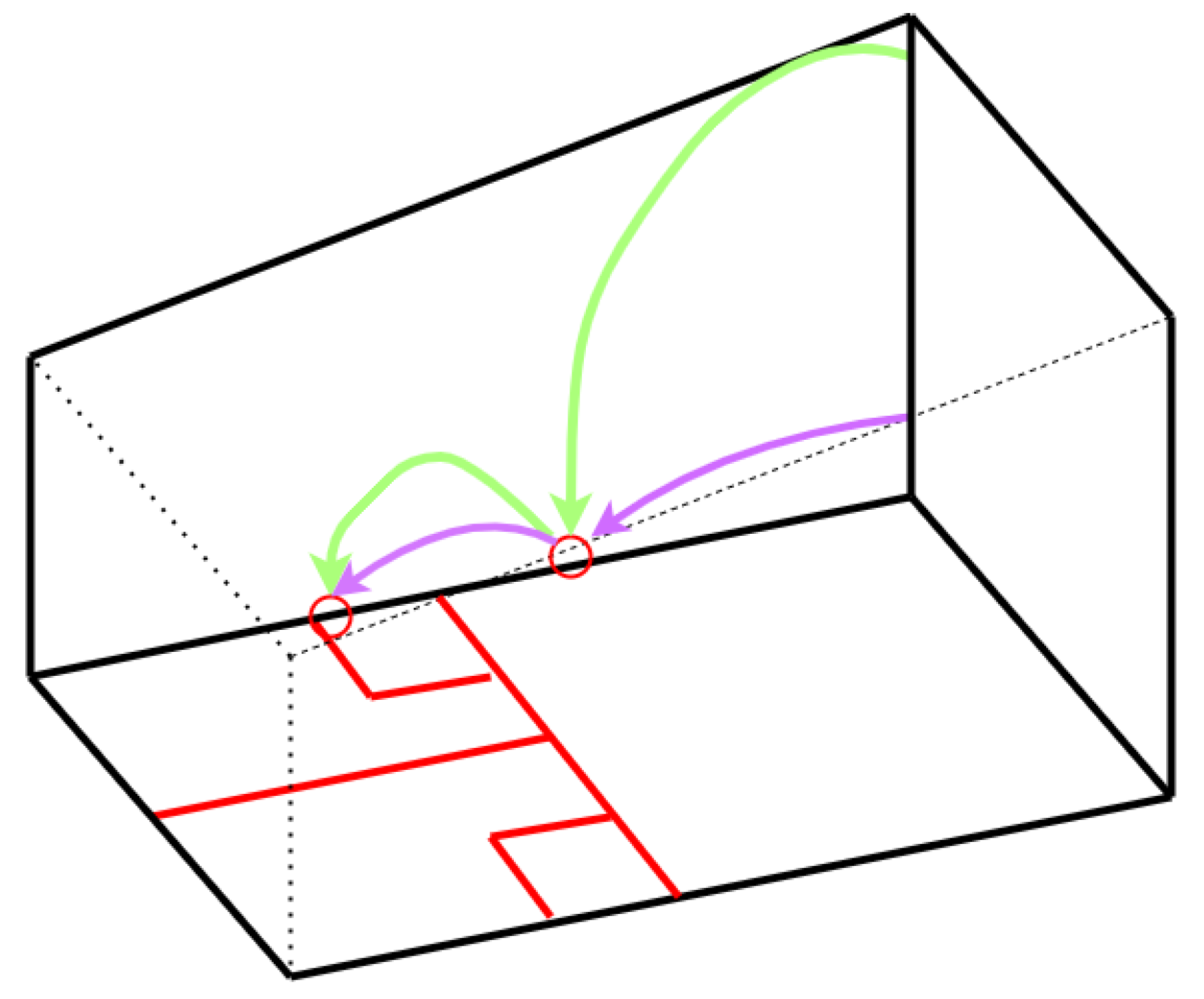

3.5.8. The Shortest Distance from Racquet Head to The Path of Ball

For multiple values described above, the limitation of “not able to identify where the AP is going to play the ball” exists. This value aims to resolve the issue by calculating the shortest distance from the path of the ball to the AP’s racket head. The path of the ball is defined as the straight line segment from the ball position in frame to the second bounce position. We define the shortest path to be the line which originated from the racket head position and is perpendicular to the ball’s path. If the line intersects the ball path (as the ball path is a line segment and could end before the intersection happens), we calculate the distance from the racket head position to the intersection. If the intersection does not exist on the line segment, we take the closest ending point (either second bounce or ball position) on the line segment and calculate the distance from it to the racket head position.

Figure 20.

Data #283 Gaultier/Ashour 2013 British Open 22:55 Yes Let [

30].

Figure 20.

Data #283 Gaultier/Ashour 2013 British Open 22:55 Yes Let [

30].

This is an example of the shortest distance to the ball’s path. If there was not any interference, the AP would have chosen to approach the ball through the path with the shortest distance (which is the line perpendicular to the path) instead of going all the way to where the ball bounces.

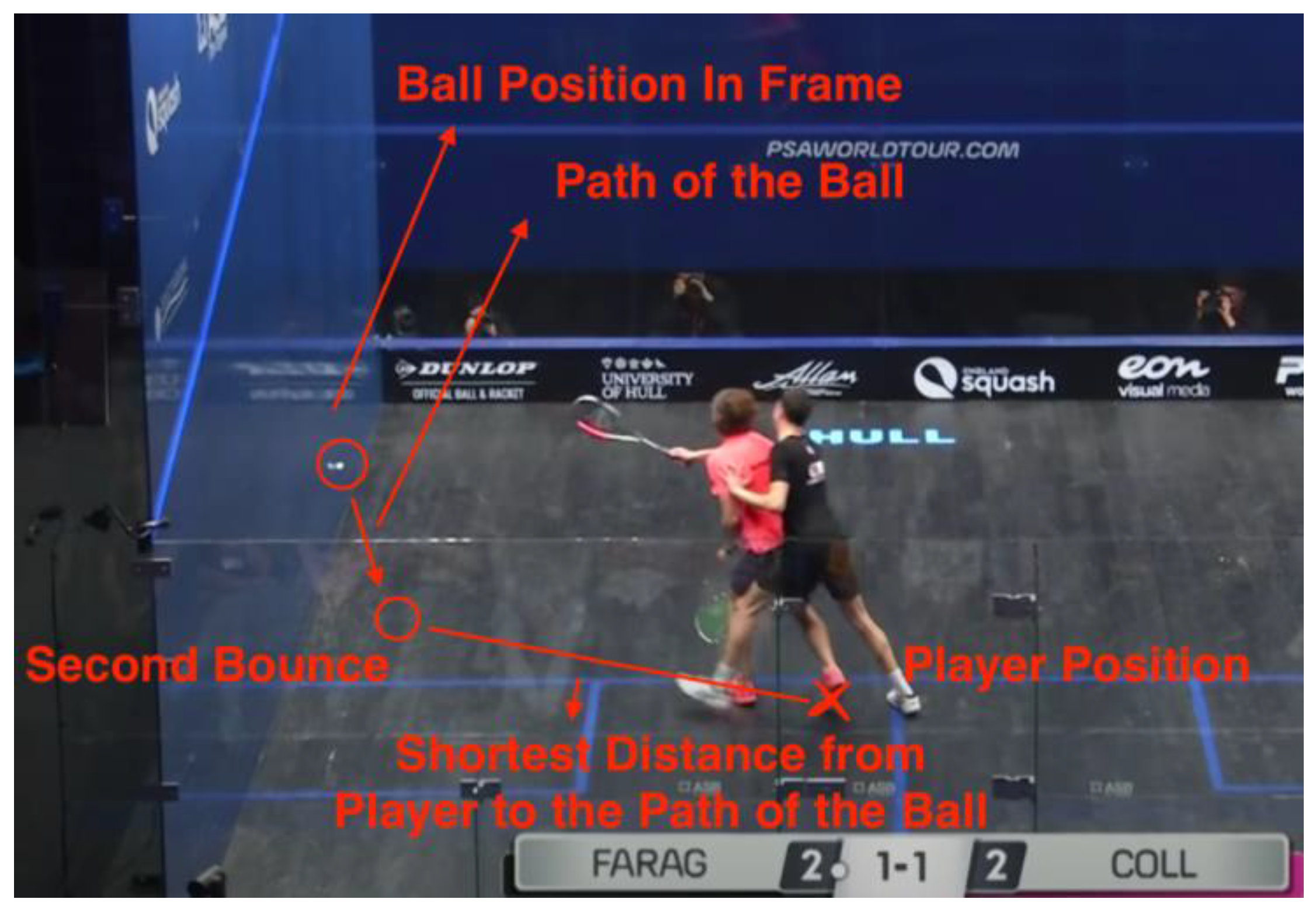

Figure 21.

Data #390 Farag/Coll 2019 British Open 1:05:40 Yes Let [

31].

Figure 21.

Data #390 Farag/Coll 2019 British Open 1:05:40 Yes Let [

31].

In this case, the shortest distance to the path of the ball is the distance to the second bounce position. Because the perpendicular line to the ball’s path originating from the AP’s position does not intersect with the line segment (does not exist on the path), we take the closest ending point of the segment (either ball position in frame or second bounce position) as the closest point.

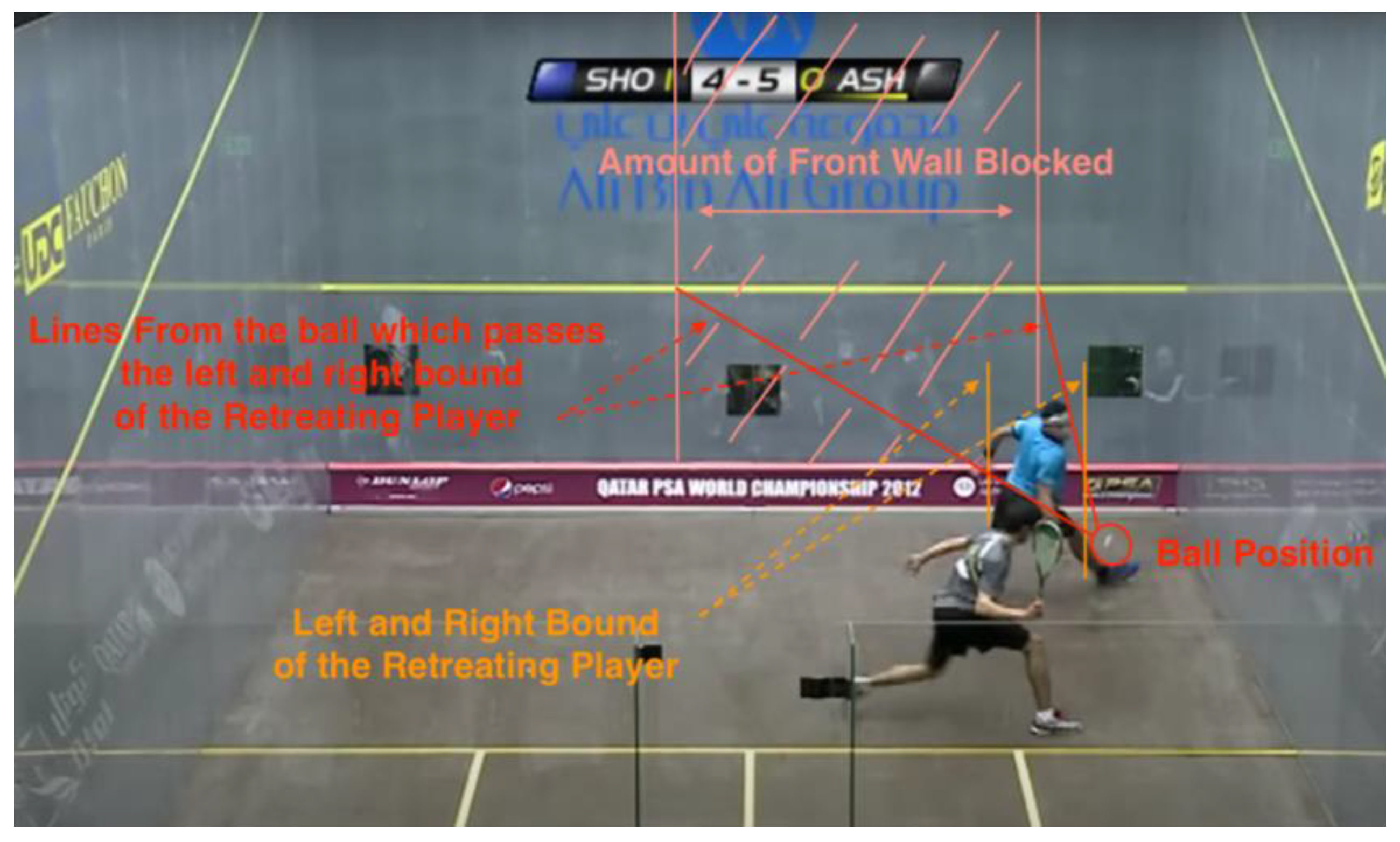

3.5.9. Access to the Front Wall: How Much is Blocked by the Other Player

When the RP blocks the AP’s access to the front wall, the situation is considered a Stroke. This rule is sometimes compromised when the blockage is little or the AP is not able to make shots due to the speed or the position of the ball. Although it is not a clear-cut situation, a significant blockage of the front wall is still considered a Stroke. We calculated the blockage by drawing lines from the AP to both sides of RP, offset by the player’s body width, and analyzing where the lines meet the front wall. For this study, we defined the body width as 80 cm, as the average shoulder width for men is around 40 cm, and we added 40 cm of width to the total width due to the arms and the legs on each side [

32].

Figure 22.

Data #118, Elshorbagy/Ashour 2012 World Championship 23:16 Stroke [

27].

Figure 22.

Data #118, Elshorbagy/Ashour 2012 World Championship 23:16 Stroke [

27].

This is an example of how the amount of blockage on the front wall is calculated. Two imaginary lines are drawn from the ball passing the bounds of the RP and reaching the front wall. The final blockage is the width of the area (labeled in pink) inside the two lines.