1. Introduction

Resveratrol (RSV) is a plant-derived phytoalexin compound, which is naturally produced in response to environmental stress and pathological invasion, acting as a natural inhibitor of cell proliferation. RSV has inhibitory effects on many processes such as platelet aggregation, vasoconstriction, proliferation of smooth muscle, low-density lipoprotein oxidation, and nitric oxide synthesis (1). RSV has shown interesting effects on tumor microenvironment and it is currently considered an option in prevention and treatment of human cancer (2). Its biochemical and molecular activities induce apoptosis among cancer cells by increasing pro-apoptotic p53 gene expression and decreasing expression of apoptotic inhibitor Bcl-2 (3,4). Suggested mechanisms for the anticancer effects of resveratrol are induction of cell death by regulating Fas levels in the cell membrane (5,6) or reduction of protein production to the cell cycle (7,8), among others. Cancer chemoprevention is based on the use of nutraceuticals or phytochemicals to reverse carcinogenesis before the metastasis phase occurs. This can be achieved by blocking key events of tumor initiation and progression or by inhibition of the ability of cancer cells to migrate to other tissues. It has been demonstrated that adequate treatment during the early stage of cancer could positively affect the carcinogenesis pathways (9). Numerous phytochemicals are proposed as chemopreventive agents, in particular RSV has recently been under the spotlight due to their wide-spectrum therapeutic properties. Literature data supports RSV as a potent chemopreventive and chemosensitizer agent that enhances anticancer therapies by regulating multidrug-resistant protein expressions, by interfering with cell signal pathways and cell cycle regulators and by influencing apoptosis (10).

Despite literature data evidencing RSV effectiveness against various diseases such as diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, obesity, inflammation, cardiovascular, neurodegenerative and cancer, its therapeutic use is hindered by its instability and unfavorable pharmacokinetic properties. According to the Biopharmaceutical Classification System, RSV is considered a Class II compound (11). Therefore, this molecule crosses the biological membranes, and it is widely absorbed after oral administration. Nevertheless, RSV is extensively metabolized in the enterocytes and hepatocytes, leading to glucuronidation and sulphate metabolites showing lower biological activity than the parent compound (12). As a result of this, RSV plasma and tissue concentrations are below the IC50 values reported for in vitro cancer cells (5-100 µM) even after administration of very high oral doses (13,14). Searching of analogue molecules with more favorable pharmacokinetic profile is among current strategies to overcome the RSV drawbacks, but nanotechnology appears as the most promising approach to achieve this goal. Nanotechnology has been applied to produce controlled delivery systems with RSV, including liposomes, polymer nanoparticles, micelles, lipid and inorganic nanocarriers, nanocrystals, nanoemulsions, and bionic drug delivery systems (12). Several studies have been carried out with liposomes for RSV to be targeted to different cells, such as folate decorated liposomes for osteosarcoma (15) p-aminophenyl alfa-d-mannopiranose or germ agglutinin decorated liposomes for brain gliomas (16) mitochondria-targeted liposomes (17,18), deformable and hyaluronic-acid decorated liposomes for epidermal cells (19), fusogenic liposomes for brain-microvascular vessels (20) or pH sensitive liposomes for microenvironment of tumor (21). Moreover, liposomes have been applied for RSV to increase sensitivity to doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil of colorectal cancer cells (10,22), for docetaxel synergy in prostate cancer (23), and for protective effect against DOX and cisplatin side effects (10,24). On top of that, RSV liposomes have been assayed for vaginal infection (25,26) and periodontal diseases (27).

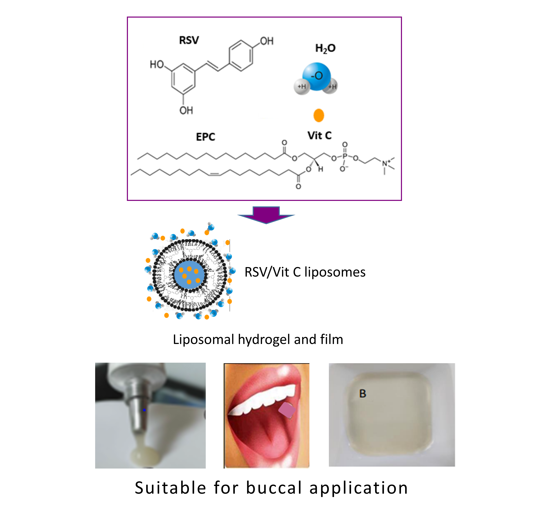

Oral cancer represents the most common head and neck cancer, and most cases are histologically defined as oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCC). The onset of this kind of tumor is multifactorial, starting from changes in the normal mucosa and evolving into cancer lesions that eventually lead to metastasis (28,29). Despite the available therapeutic strategies having been greatly improved over the past decades, the patients’ survival rates are still below 50% (30). Identification of novel therapeutic agents and innovative approaches aimed at both treatment and prevention of OSCC, is a high concern among the scientific community. Since chemoprevention, therapeutic synergy and ameliorating of chemotherapy side effects have been proved for RSV, targeting to oral mucosa seems to be an interesting approach to take advance of the wide-spectrum of therapeutic properties assigned to RSV. Our hypothesis is that all these benefits might be achieved in patients prone to suffer buccal cancer or already suffering from OSCC, as far as controlled delivery of RSV at the oral mucosa is accomplished. Liposomes have proved their ability as drug nanocarriers for mucosa membranes (31,32) and physicochemical properties of RSV make it a good candidate to be loaded in liposomes. Accordingly, the aim of the present study was to efficiently produce RSV loaded liposomes able to controlled delivery in the oral mucosa and suitable for topical application at the oral cavity. A solvent-free procedure that preserves RSV stability has been optimized to obtain RSV liposomes using phosphatidylcholine as the bilayer phospholipid. The produced liposomes have been characterized in regards to size, polydispersity, zeta potential, entrapment efficiency, cell biocompatibility, antioxidant efficacy and in vitro permeability. All these studies focused on assessing the suitability of RSV liposomes to be included in medicines for buccal administration aimed at chemoprevention and enhancement of oral cancer chemotherapy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

L-α-phosphatidylcholine egg yolk (EPC), sodium alginate low (ALV) and high viscosity (ALV and AHV, respectively) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich® (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Resveratrol (RSV), vitamin C, glycerine (G), citric acid monohydrate, xanthan gum and Tween-20® were purchased from Acofarma S.A. (Madrid, Spain). HPLC-grade ethanol and acetonitrile were supplied by Thermo Fisher Scientific (Germany). H2PO4, NaOH and disodium phosphate were purchased from PanReac ApplieChem (Darmstadt, Germany). Ultrapure water was obtained with a Wasserlab Automatic Plus System. Cromafil® PETfilters from Macherey-Nagel (Duren, Germany). Human buccal carcinoma cell line TR146 (#151425) was purchased to CancerTools (UK), Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, #D5796), fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin/streptomycin, trypsin-EDTA, and 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA, #D6883) were purchased to Merck KGaA (Germany).

2.2. Preparation and Characterization of Liposomes

Liposomes were prepared from egg phosphatidylcholine (EPC) and trans-resveratrol (RSV) at 0.3 and 0.5 RSV molar fractions and different RSV concentrations, as shown in

Table 1. MilliQ-water or phosphate buffer pH=7,4 (PBS) with 0.5% w/w vitamin C were used as hydration media.

A solvent free method previously described (32–35) was optimized to prepare the liposomes. In brief, the proper amounts of EPC and RES were weighted and mixed in a glass vessel to form a thin film. Hydration media with 0.5% w/w vitamin C or without vitamin C was added and mixed until dispersion of the thin film. The mixtures were placed in a Fisher Scientific FB 15061 ultrasonic bath (50 Hz) for 20 min to facilitate the lipid hydration and arrangement to form the RSV loaded liposomes. Different temperatures (30-40ºC range) were assayed to evaluate the influence of this condition on the efficiency of the process. The resulting suspensions were extruded (8 times across Cromafil® PET filters of 0.45 µm), and the samples were kept at room temperature for 60 min. Then, liposome suspensions were stored at 4 -6◦C until use. Turbidity, viscosity (γ), optical microscopy, as well as pH measurements were carried out as routine controls applied to each batch of liposomes prepared. Turbidity measurement was carried out using a HACH 2100Q turbidimeter calibrated with standard samples in a range of 400-12000 NTU (Nephelometric Turbidity Unit). Samples were properly diluted for the turbidity being into the calibration range and inserted in the portable turbidimeter. A glass capillary viscometer was used for viscosity (γ), which was estimated from the time it took for the sample to flow through the capillary marks under the influence of gravity. The instrument, provided with two set of marks, was calibrated with milliQ-water (ρ = 1 g/mL; γ = 1 mm

2/s) to estimate the viscometer constants (K1 and K2, mm

2/s

2). The time required by the sample to flow through the capillary tube marks was converted to a kinematic viscosity using the equation:

where t is the time (s) and K is the corresponding calibration constant value (k1=0.0164 and k2=0.012 6 for the first and second mark, respectively).

For the optical microscope, 10 µL of sample was placed on a glass support and fixed to be observed using an optical microscope connected to a digital camera. For pH, a pHmeter (Peak Instrument INC, 1801) was used.

In addition to the above routine controls, the next assays were performed in triplicate

-Hydrodynamic diameter (Dh), polydispersity index (PDI) and zeta potential of liposomes were analyzed by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, Co., Malvern, UK). The analysis was performed at 25 ºC and a scattering angle of 173º, after the appropriate dilution with milli-Q containing or not vitamin C, to avoid multiple scattering.

-Entrapment efficiency (EE%). Quantification of RSV in samples before and after filtration was carried out by an HPLC technique to evaluate the efficiency of the method to incorporate the RSV into the liposomes. A Purosphere STAR RP-18 endcapped, 50 mm × 4.0 mm, 5 µm column and a mixture of 0.1% formic acid in water and acetonitrile (70/30 v/v), adjusted to pH 4.2 using triethanolamine, were used. The injection volume was 10 μL, and the flow rate was 1 mL/min, with the column temperature at 25ºC. The UV detector was set at 292 nm (HPLC system with Waters Alliance 2695 separation module, 2998 photodiode array detector and empower processor system). The area under the curve of the RSV peak was registered for detection and further calculation of the RSV concentration. 2 mg/mL RSV stock solutions were prepared using 95% v/v ethanol or water-ethanol mixture (50% v/v). Calibration curves of RSV for each solvent were prepared at different concentration ranges and analysed. Since differences were not found the later was used for RSV in liposome samples. The analytical method was validated for specificity, linearity, precision, accuracy and stability (

Table S1 in supplemetary material).

EE% was estimated according to the following equation

Where Cf is the RSV concentration measured in filtered liposome suspension and Ci is the initial RSV concentration used to prepare the liposomes.

From EE% values, RSV payload (µg/mL; mM) in liposome suspensions were estimated.

2.3. Studies with TR146 Cell Line

The human buccal carcinoma cell line TR146 was used to evaluate antioxidant effect of RSV liposomes. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and incubated at 37ºC in 5% CO2. Culture media was replaced every 2–3 days and at 70–80% confluence cells were split using 0.25% trypsin–EDTA. For all studies described TR146 cells were used between passage 16 and 19.

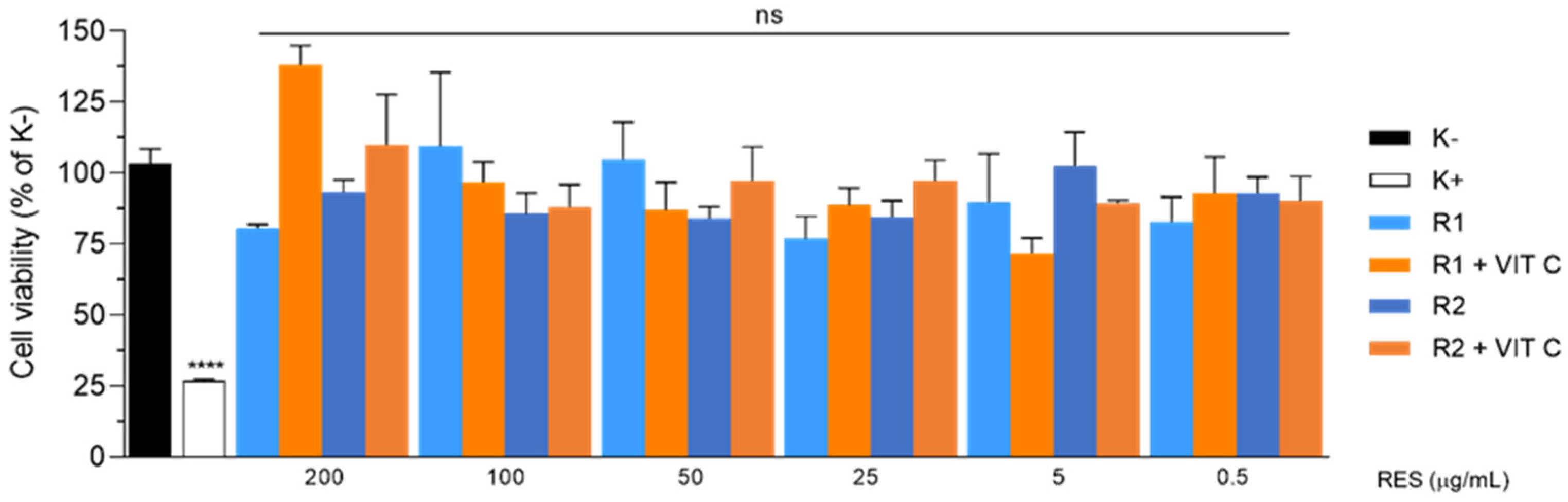

2.3.1. Cell Biocompatibility

Cell growth was monitored using an Optika inverted light microscope equipped with an Opikam B5 (BG, Bergamo, Italy) digital camera. The MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay was used, following ISO 10993–5, to evaluate cell viability in the presence of liposomes. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates with DMEM, using a cellular density of 1x104 cells/well, and incubated at 37 C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere for 24 h. After 24 h, the culture medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium mixed with sterile liposome suspension diluted for different RSV concentrations (0.5-200 µg/mL) and maintained at 37ºC in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere for 24 h. After 24 h the culture medium was removed and replaced with 50 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL in PBS). The cells were then incubated for 3 h at a 37º C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. Thereafter, MTT was removed and 100 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added and gently agitated for 15 min at room temperature to dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance was then measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Multiskan GO—Thermo Scientific). Ethanol 70% treated cells were used as positive controls (K+) (dead cells), whereas untreated cells (without liposomes) were used as negative controls (K-). The mean cell viability values (n=3, independent experiments) have been expressed as the percentage of K+.

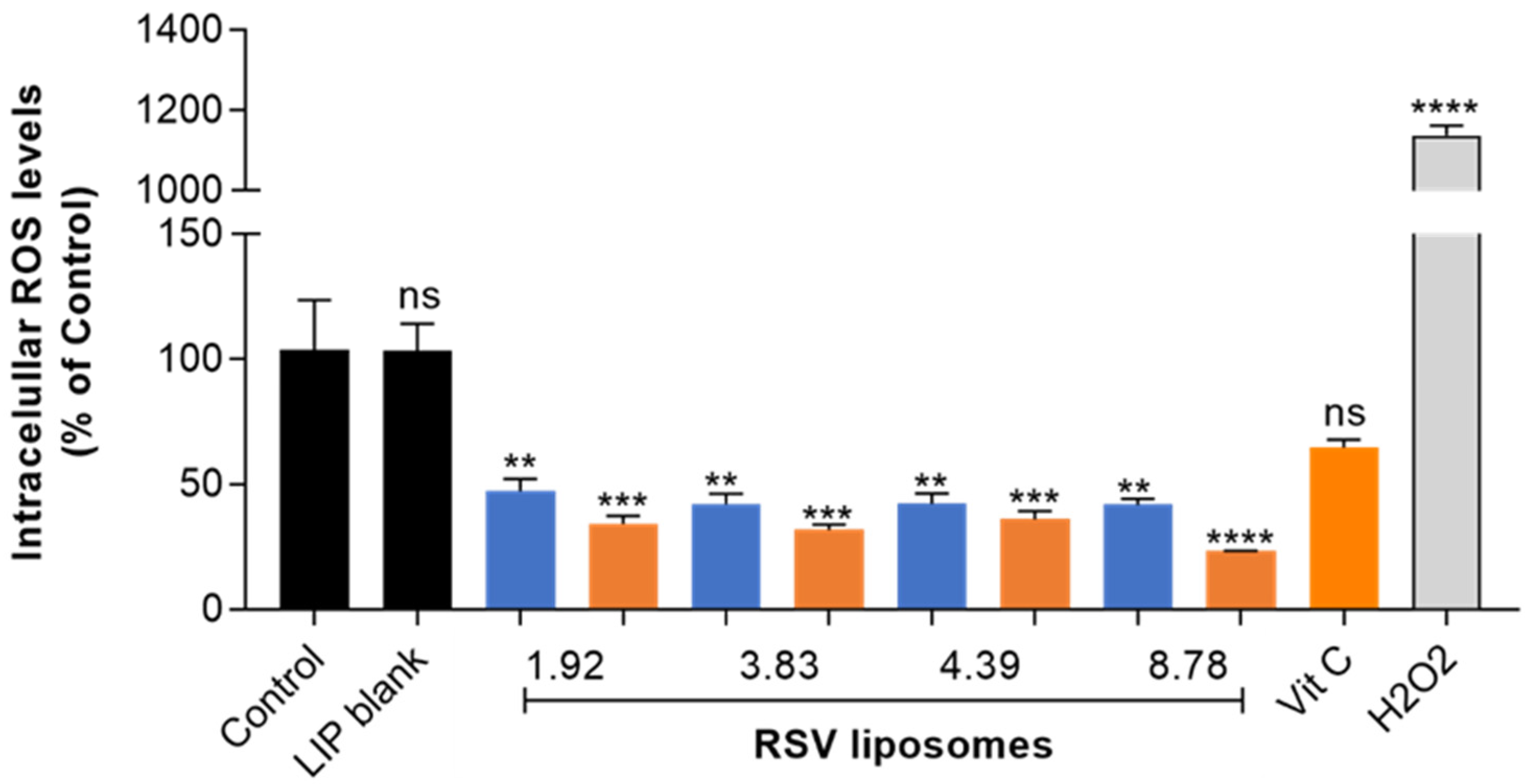

2.3.2. Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Assay

ROS levels were analyzed using the cell-permeable probe 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate. The DCFDA assay measures the fluorescent 2,7-dichlorofluorescein that results from DCFDA oxidation by ROS. About 2x104 TR146 cells were seeded in 96-well plates in the day before to the experiments. Cells were incubated with DCFDA (50 µM) in complete medium for 1h at 37 ºC, and then treated with the different formulations of liposomes for 1h. Cells incubated with DCFDA, without liposomes treatment, and cells treated with H2O2 were included in the assays as negative and positive controls, respectively. The fluorescence produced in the DCFDA assay was measured in a SpectraMax Gemini spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices) at excitation/emission wavelengths of 485/535 nm.

2.4. Permeation Assay

An Erweka vertical diffusion chamber with a permeation area of 2.2 cm

2 was used for this assay. A fixed volume (2 mL) of the liposome suspension was placed in the donor compartment, and a PermeaPad® membrane was mounted to reach occlusive conditions. Then, the chamber was immersed in a vase containing 100 mL of simulated salivary fluid (SSF) at 36º C acting as the receptor compartment. SSF samples were taken at previously programmed times (2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, 120 and 150 min) and replaced with the same volume of fresh SSF. RSV was quantified in the withdrawn samples by the HPLC method above described and the cumulative amount in the receptor compartment was estimated. The cumulative amount of permeated RSV was plotted against time, and the slope of the linear part of the curve, representing the steady-state flux rate (Jss), was used for permeability (P) calculation, according to the following equation:

Where Jss is the slope of the linear fraction of the curve, and A is the permeation area.

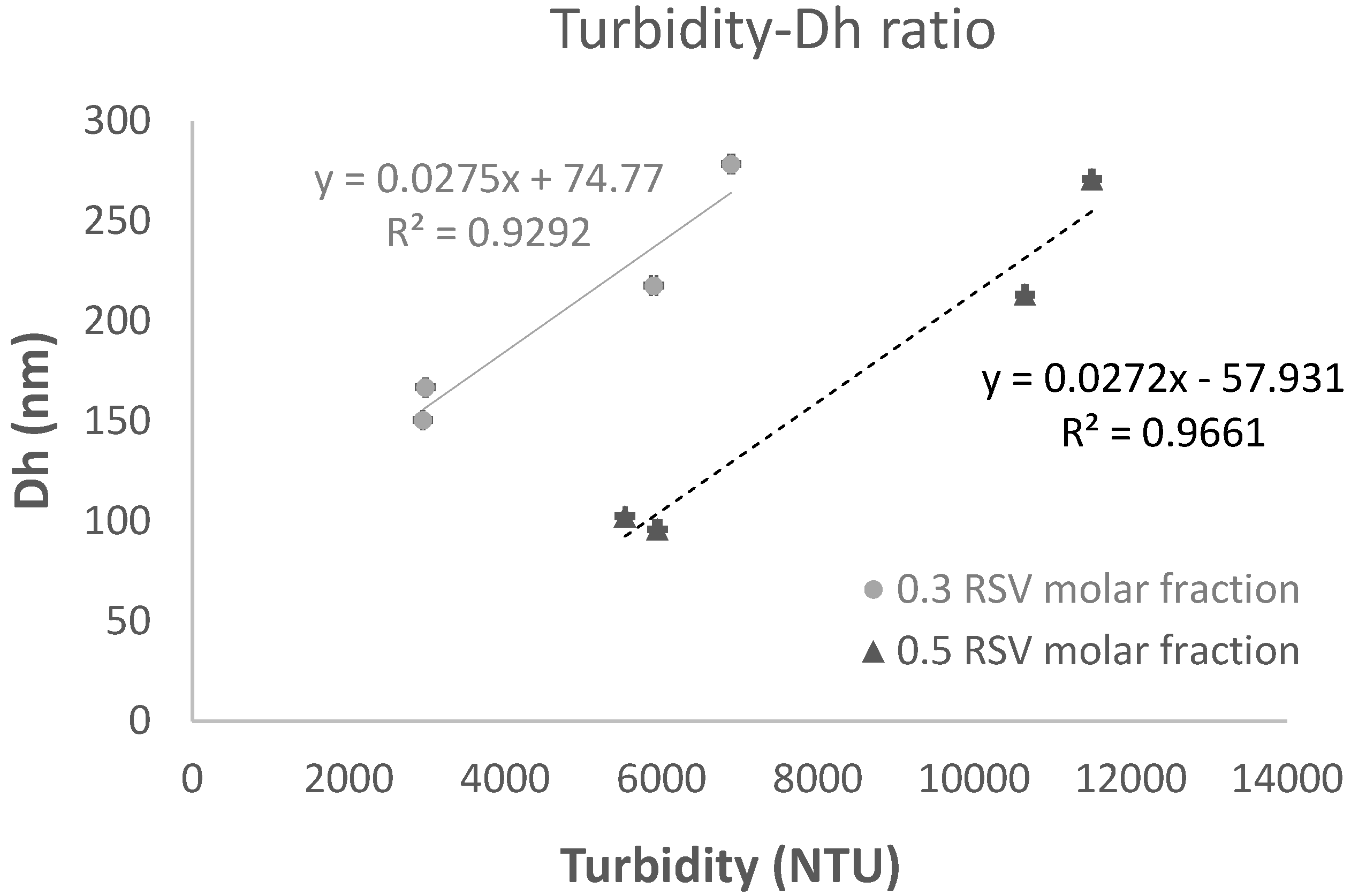

The similarity factor (f2) was assessed to compare kinetic profiles from samples with and without vitamin C using the following equation

Where n is the number of observations, Lt and LCt the average amount of RSV released from liposomes without vitamin C and with vitamin C, respectively. RSV release profiles were also analyzed based on the following plots: cumulative amount of drug released vs. time for zero order; log % drug remaining vs. time for first order; cumulative % drug release vs. square root of time for the simplified Higuchi model, and the log cumulative % drug released vs. log time for the Korsmeyer-Peppas model (36).

2.5. Buccal Formulation (Liposomal Hydrogels and Films)

Liposomal hydrogels and films were prepared using alginates of low and high viscosity (ALV and AHV, respectively) as gelling agent and glycerin (G) as hygroscopic/plasticizer agent. Different combinations of ALV (2-6%w/w) or AHV (2-4%w/w) with G (1-3%w/w) were assayed and the rheological properties (viscosity, extensibility, extrusion properties) of resulting hydrogels were evaluated.

Hydrogels were prepared by adding the proper amount of alginate to the liposome suspension, the mixtures were agitated until sample homogenization and refrigerated overnight. Then G was added and the resulting mixtures used for rheology assays and film preparation. Viscosity was measured at 25ºC using a rotational viscometer (801 Nahita). For the extensibility, increasing weights were applied to a fixed amount of hydrogel (0.5 g) placed between two glass plates and the diameter of the spread hydrogel area was recorded. Extrudability through 2-0.5 mm range was tested.

Films were obtained from hydrogels by the film casting method (37). In brief, 3.5 g of hydrogel were poured into 2 cm side plates and maintained at 30 ± 2ºC for 14 hours. Remaining moisture, flexibility and folding resistance of resulting films were tested at the end of drying period.

The experimental procedures above described were carried out protecting the samples from light exposure.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis and comparison were performed using GraphPad Prim 7, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnet’s post hoc test. Results are described as mean ± standard deviation and data were considered statistically significant at a value of p <0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Influence of Temperature

The preparation of liposomes at temperature above a critical value is a requirement for lipids to hydrate and rearrange into the concentric bilayers forming the liposomes. Resveratrol is found in either cis- or trans-configurations, but the latter is the only active form. Unfortunately, RSV exposure to light, pH> 7 or high temperature activates the pass of trans- to cis-configuration. Temperatures from 30ºC to 40ºC were assayed in this study and the results revealed that below 35ºC the process was not efficient (EE%<15%), irrespectively of the RSV molar ratio (0.3 or 0.5), RSV concentration (1.9-8.78 mg/mL) and the presence or absence of vitamin C in samples. Ultrasonic agitation at 40ºC facilitated sample extrusion, and produced higher EE% values. Nevertheless, the higher the temperature the greater the risk of isomerization of trans-resveratrol to the inactive isomer, therefore a balance between process efficiency and RSV stability was considered and a temperature of 37ºC was selected in our study to prepare the RSV liposomes.

3.2. Influence of Hydration Media, RSV Molar Fraction and RSV Concentration

Table 2 shows the main characteristics of produced liposome suspensions. Acidic pHs were found in all cases, irrespectively of RSV molar fraction, RSV concentration and presence or absence of vitamin C, and lower pH values were achieved for samples with vitamin C. For RSV, an acidic medium is advantageous because low pH protects the active form from its isomerization to the cis isomer.

Regarding viscosity, lower values were found in samples with vitamin C, compared to those without the vitamin, irrespectively of RSV molar fraction and RSV concentration, the differences being statistically significant (p<0.001).

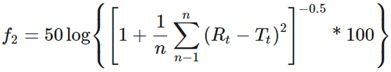

Turbidity depends on the number and size of particles suspended in a liquid media and this was selected as the Critical Process Parameter (CPP) in relation to the liposome hydrodynamic diameter (Dh), which is a critical quality attribute (CQA) of liposomes. As found for viscosity, it was observed that vitamin C influenced turbidity and the samples with vitamin C presented higher values than those without the vitamin, irrespectively of the RSV molar fraction and RSV concentration, the differences showing statistical significance (p<0.001). Notice the low variability of turbidity measurements, with variation coefficients below 1% confirming the robustness and reproducibility of the solvent-free method applied here to prepare RSV liposomes. A similar procedure had been previously validated for liposomes of EPC and cholesterol (CHOL) bilayer loaded with sildenafil citrate (34), but this procedure has been applied for the very first time here to prepare EPC liposomes without CHOL but RSV, at low temperature.

For Dh, in line with viscosity and turbidity data, results confirm the influence of vitamin C, and higher Dh values were observed for samples with vitamin C (213.26-278.43 nm range) compared to those without the vitamin (95.91-166.86 nm range). A linear relationship between turbidity and Dh was found for 0.3 and 0.5 RSV molar fraction, as shown in

Figure 1 and this correlation validates the turbidity of liposome suspension as the CPP related to the CQA of liposomes.

PDI and zeta potential were not significantly affected by RSV molar fraction, RSV concentration or vitamin C in samples, although lower PDI values were observed for samples without vitamin C (PDI<0.25) than found for those with the vitamin (PDI 0.26-0.35 range). Negative values of ZP, in the range of -4.68±0.66 mV to -12.56±2.49 mV, were observed in all cases. These results are in line with previous studies performed to characterize the interactions of EPC with vitamin C (38) which reported that the dielectric properties of the lipid bilayer were not altered by the vitamin, likely due to conservation of structured water of the phosphate groups in the polar heads of the lipid. Comparison of RSV-EPC liposomes produced here with CHOL-EPC liposomes (39) reveals similar negative ZP values. Some previous studies have shown that RSV incorporates into the hydrophobic core of the EPC bilayer close to the double bonds of polyunsaturated fatty acids, similar to cholesterol location in lipid bilayers (40), while others have shown that RSV also adsorbs onto the membrane surface.

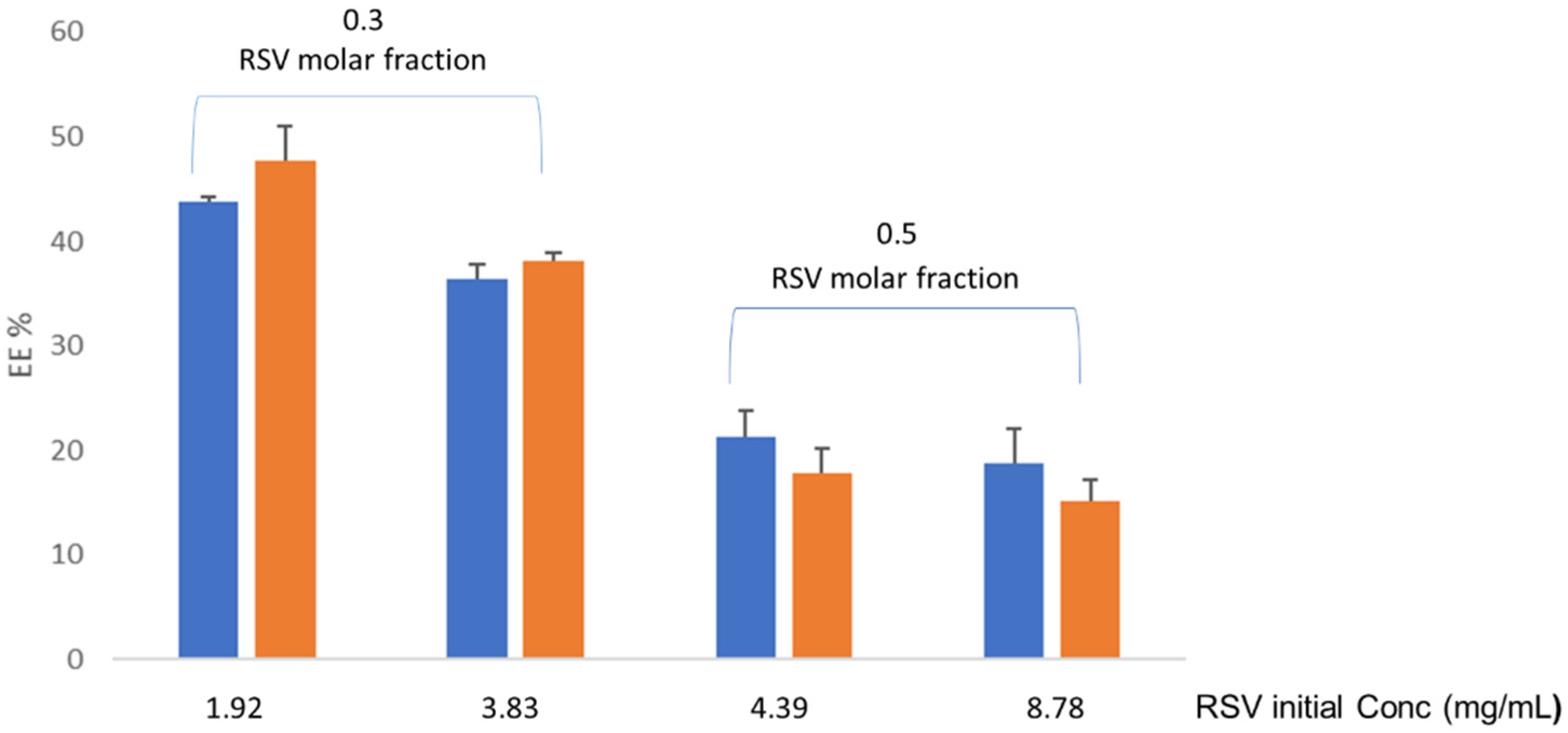

RSV calibration curves in the range of 25-300 revealed linearity (r²=0,999), irrespectively of using 95% ethanol or water-ethanol mixture (

Figure S1 in supplementary material). It was found that RSV quantification in unfiltered liposome samples diluted with water-ethanol mixture produced concentration values lower than expected for the RSV amount initially added. This finding alerted on RSV remaining in the bilayer and not being properly quantified by the HPLC when diluted with the mixture. In fact, same samples diluted with 95 % ethanol and vortexed before analytical quantification lead to RSV concentrations fitting the theoretical values. Accordingly, the later condition was applied to for RSV analytical quantification in liposome samples. The results (

Figure 2) showed that EE% progressively decreased as RSV concentration increased and the highest values (43,78 ± 0,47% for liposomes without vitamin C and 47,63 ± 3,35% for liposomes with vitamin C) were achieved for the lowest RSV concentration and molar fraction (1.92 mg/ mL and 0.3, respectively).

This finding points to a limited number of RSV molecules able to be packed into the lipid bilayer of the liposomes, the rest remaining in the dispersion media and retained by filters used for extrusion. Literature data (41) reported that RSV adsorbs on the membrane surface and then inserts and assembles into the bilayer until reaching the appropriate RSV/lipid ratio. According to our results, RSV molar fractions ≥ 0.3 lead to RSV excess retained in the filter during the extrusion process. According to this finding, molecular packing restriction for RSV in lipid EPC bilayer seems to be different that reported for CHOL, the latter able to incorporate into lipid bilayers up to 0.5-0.6 molar fraction (42).

RSV payload in liposome samples were estimated from the corresponding EE% and values in the range of 0.81-0.90 mg/mL (equivalent to 3.59-3.98 mM) were obtained, irrespectively of the initial conditions applied, this likely due to the above commented restriction for RSV molecules to be packed in the lipid bilayer. Despite this limitation, the RSV payload was high enough for buccal formulations to achieve concentrations in oral mucosa above the IC50 values (5-100 µM) reported for cancer cells (43).

3.3. Liposome Biocompatibility

Results from the biocompatibility assay are shown in

Figure 3. For the conditions tested, mean cell viability >70% was observed in all cases and no statistically significant differences were found when compared to negative control (100% cell viability).

Our results prove that proposed liposomes are biocompatible and safe at RSV concentrations (up to 200 µg/mL =.88 mM), higher than reported values for pharmacological effects linked to RSV benefits.

3.4. Antioxidant Effects of RSV Liposomes

TR146 cell line that mimics human buccal epithelium was selected for ROS assay. As shown in

Figure 4, intracellular ROS were significantly reduced by RSV liposomes showing remarkable antioxidant effects that were not significantly affected by RSV molar fraction or RSV concentration conditions used for liposome production. As previously commented, RSV payload of liposome samples obtained after extrusion were all in the narrow range of 0.81-0.90 mg/mL (equivalent to 3.59-3.98 mM), this explaining that differences in ROS results among liposomes prepared from different concentrations were not found.

Vitamin C reinforced the antioxidant effects of RSV liposomes, and lower ROS levels were observed for samples with the vitamin compared to those without vitamin. Regarding liposomes prepared from different RSV concentration, statistically significant differences among them were not found. Despite relevant differences among initial RSV concentration used for liposome production, the final payload was in the narrow range of 0.81-0.90 mg/mL (equivalent to 3.59-3.98 mM) in all cases, this explaining that differences in ROS results among liposomes prepared from different concentrations were not found. Results from ROS assay obtained here confirm the interest in encapsulating RSV in liposomes to improve the cell exposure to the phytoactive molecule. Besides acting as efficient nanocarriers, liposomes protected RSV from enzymatic metabolism and facilitated the achievement of effective intracellular concentrations in TR146 cells, representative of squamous cell carcinoma.

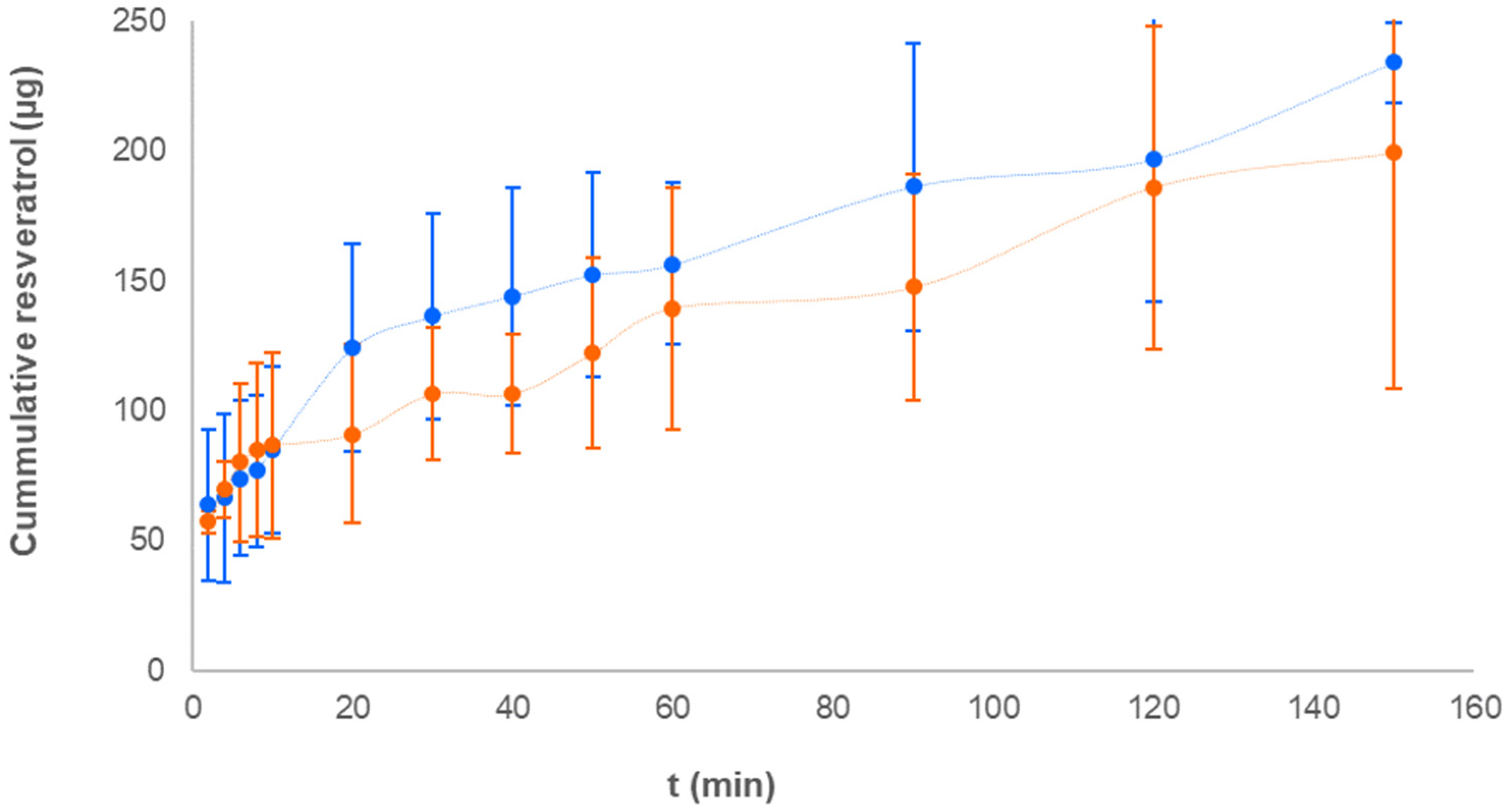

3.5. Permeation Assay

The permeability assay was carried out with liposomes produced from 0.3 molar fraction and 1.98 mg/mL RSV concentration with or without vitamin C. PermeaPad® membranes were used in this study because these have proven functionality in predicting drug transport across biological barriers, including buccal epithelium (42).

Figure 6 shows the mean cumulative amounts of RSV quantified in the receptor compartment of the diffusion cell (individual values in

Figure S2 of supplementary material).

According to similarity factor (45.14 %) and permeability values estimated from Jss, (1.42±0.90 and 0.59±.0.66 µg/cm2/min for samples without and with vitamin C, respectively), the presence of vitamin C produced a slower permeation rate compared to samples without the vitamin, this likely due to the higher Dh value observed for liposomes with vitamin C. In any case, the ability of RSV liposomes to efficiently permeate the PermeaPad® membrane was proved and these results, together with those obtained from ROS assay with TR146 cells, confirm the multi-functionality of liposomes which showed the ability not only to transport but also to protect RSV from the enzymatic cell activity.

Kinetic analysis of curves showed that the non-linear regression Higuchi and Korsmeyer Peppas models best fitted the experimental data, with release exponent values (N <0.5) pointing to a Fickian diffusion to be the mechanism involved in liposome permeation across the membranes.

Table 3.

Result from in vitro release profiles data fitting to different kinetic models.

Table 3.

Result from in vitro release profiles data fitting to different kinetic models.

| |

Zero Order |

First Order |

Higuchi |

Korsmeyer-Peppas |

| r2

|

r2

|

r2

|

r2

|

N |

| Without Vit C |

0.9460 |

0.9200 |

0.9681 |

0.9339 |

0.3153 |

| With Vit C |

0.9381 |

0.8791 |

0.9715 |

0.9619 |

0.2230 |

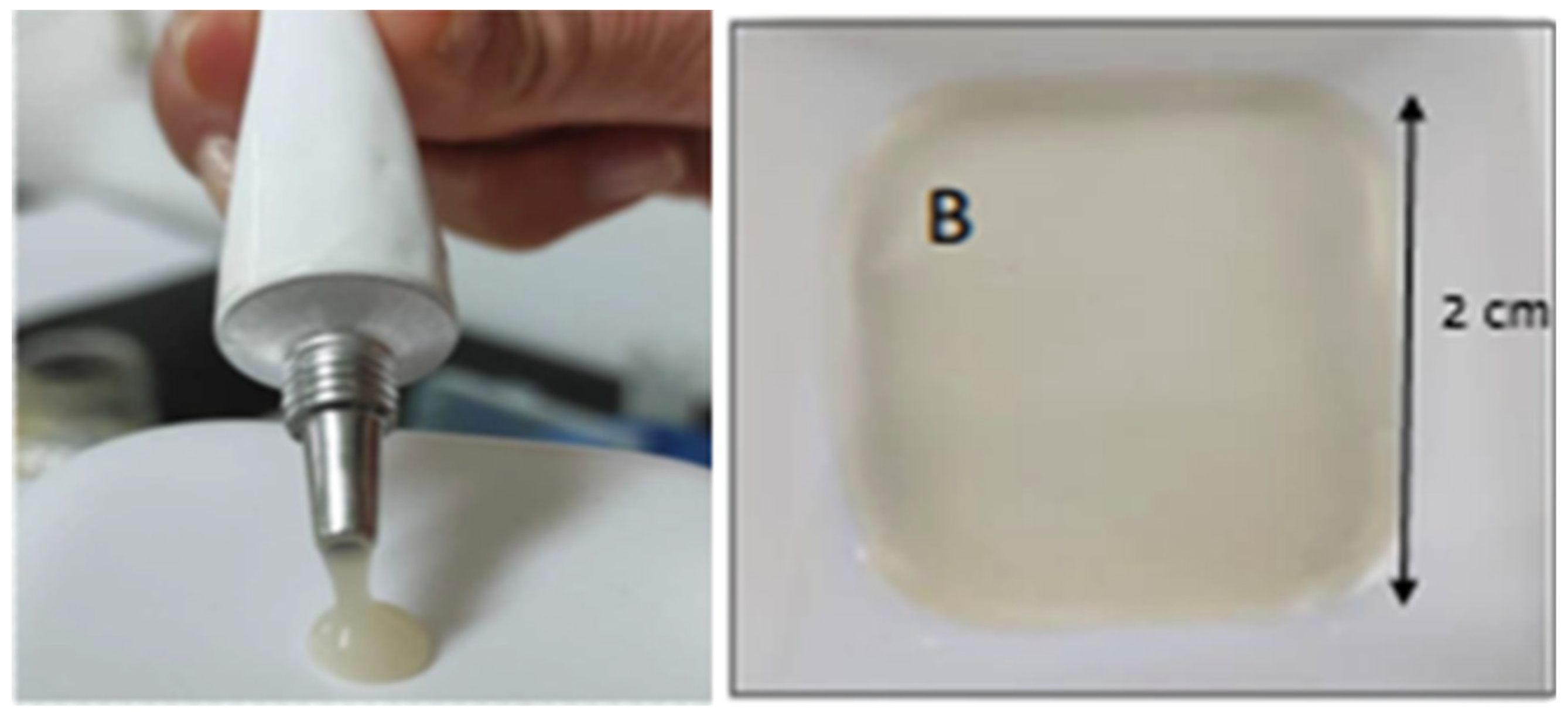

3.6. Liposomal Formulations for Buccal Application

As proof of concept, liposomes prepared from 0.3 RSV molar ratio and 1.92 mg/mL RSV concentration with vitamin C were formulated as hydrogels and films. Liposomal hydrogels presented smart aspect and favorable rheology. The weak value of zeta potential observed in liposomes makes them prone to aggregation. Nevertheless, a homogeneous distribution of liposomes in the hydrogels was observed, this likely due to the viscosity that hinders liposome diffusion and aggregation. Hydrogels showed favorable rheology for topical application and “on site” retention, as well as easy extrudability trough diameter≥1mm (extensibility results in figure S3 of supplementary material). For films, a remaining moisture in the range of 18-20% lead to flexibility and fold resistance (≥15) suitable for buccal application. Moreover, the RSV payload permits to achieve concentrations in the oral mucosa above the IC50 values reported for cancer cells with small hydrogel amounts (<2 g) and comfortable size films (≈1 cm

2).

Figure 6 shows the aspect of RSV liposomal hydrogels and films

Previous studies on RSV liposomes have been performed and reported in literature, but this is the first time that liposomes without CHOL, made of EPC and RSV have been described and efficiently produced by a solvent-free method at low temperature. This is also the first time that RSV liposomes are proposed and characterized in terms of their suitability for buccal administration aimed at chemoprevention and/or treatment of oral cancer. Additional studies to confirm the benefits of RSV topical application and biopharmaceutics characterization of the buccal formulations proposed here are forward steps to confirm the hypothesis that RSV liposomal buccal formulations may overcome some of the RSV limitations that currently hinder its clinical use for oral cancer.

4. Conclusions

Liposomes made of EPC and RSV had been successfully produced by a solvent-free procedure based on component mixture and ultrasonic agitation at 37ºC. Turbidity-Dh relationships supports turbidity as a critical process parameter related to Dh, a critical quality attribute of liposomes, and this confirms the reliability of the solvent-free procedure applied here to prepare biocompatible, safe and high loaded RSV liposomes. Liposomes produced with vitamin C showed Dh in the range of 213.26-278.43 nm, higher than those found for liposomes without vitamin C, but still compatible for buccal tissue targeting. Efficient permeation across PermeaPad® membranes and TR146 cells uptake was observed for RSV liposomes. RSV protection from cellular metabolism was also proved, with the final result of relevant antioxidant effects that were reinforced by vitamin C. Alginates of high and low viscosity were used to prepare liposomal hydrogels and films that showed rheological properties suitable for buccal application. The payload permits to achieve RSV concentrations above reported IC50 for cancer cells in the oral mucosa with small amounts of hydrogels and comfortable sized films. This is the first study on production and characterization RSV-EPC liposomes focused on their suitability for buccal administration aimed at chemoprevention and/or treatment of oral cancer.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. complementary information can be found in Table S1 and Figures S1-S3. Table S1: Results from the validation of the analytical method used for RSV quantification in liposomal samples. Figure S1: Calibration curves obtained for RSV samples prepared with 95% ethanol or 50% ethanol/water mixture; Figure S2: Individual cumulative RSV curves obtained from the permeation assay carried out with vertical diffusion chambers using PermeaPad membranes; Figure S3: Result from the extensibility assay performed with RSV liposomal hydrogels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, supervision, visualization, project administration and funding acquisition: Maria José de Jesús Valle and Amparo Sánchez Navarro. Writing–original draft: Amparo Sánchez Navarro. Funding acquisition: Alexandra Mabel Rondon Mujica. All authors have participated in methodology, validation, investigation, resources, writing-review and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Salamanca (Program for development of prototypes oriented to industrial market, 2022/2023)

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable”

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable.”

References

- Banez, M.J.; Geluz, M.I; Chandra, A;, Hamdan, T.; Biswas, O.S.; Bryan N.S.; Von Schwarz, E.R. A systemic review on the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of resveratrol, curcumin, and dietary nitric oxide supplementation on human cardiovascular health. Nutr. Res. 2020, 78, 11–26.

- Vieira, I.R.S.; Tessaro, L.; Lima, A.K.O.; Velloso, I.P.S.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Recent Progress in Nanotechnology Improving the Therapeutic Potential of Polyphenols for Cancer. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delmas, D.; Lancon, A.; Colin, D.; Jannin, B.; Latruffe, N. Resveratrol as a Chemopreventive Agent: A Promising Molecule for Fighting Cancer. Curr. Drug Targets. 2006, 7, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.Y.; Im, E.; Kim, N.D. Mechanism of Resveratrol-Induced Programmed Cell Death and New Drug Discovery against Cancer: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, L.; Silbert, S.K.; Maude, S.L.; Nastoupil, L.J.; Ramos, C.A.; Brentjens, R.J.; Sauter, C.S.; Shah, N. N.; Abou-El-Enein, M. Preparing for CAR T cell therapy: patient selection, bridging therapies and lymphodepletion. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 342–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Zorita, S.; Fernández-Quintela, A.; Macarulla, M.T.; Aguirre, L.; Hijona, E.; Bujanda, L.; Milagro, F.; Martínez, J.A.; Portillo, M.P. Resveratrol attenuates steatosis in obese Zucker rats by decreasing fatty acid availability and reducing oxidative stress. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Chang, H.W.; Yan, D.; Lee, K.M.; Ucmak, D.; Wong, K.; Abrouk, M.; Farahnik, B.; Nakamura, M.; Zhu, T.H.; Bhutani, T.; Liao, W. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athar, H.R.; Khan, A.; Ashraf, M. Inducing Salt Tolerance in Wheat by Exogenously Applied Ascorbic Acid through Different Modes. J. Plant. Nutr. 2009, 32, 1799–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan Shankar, G.; Swetha, M.; Keerthana, C.K.; Rayginia, T.P.; Anto, R.J. Cancer Chemoprevention: A Strategic Approach Using Phytochemicals. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei, S.; Ranjbar, B.; Tackallou, S.H.; Aref, A.R. Hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) in breast cancer: The crosstalk with oncogenic and onco-suppressor factors in regulation of cancer hallmarks. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2023, 248, 154676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, E.S.; Sim, W.Y.; Lee, S.K.; Jeong, J.S.; Kim, J.S.; Baek, I.H.; Choi, D.H.; Park, H.; Hwang, S.J.; Kim, M.S. Preparation and Evaluation of Resveratrol-Loaded Composite Nanoparticles Using a Supercritical Fluid Technology for Enhanced Oral and Skin Delivery. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Lei, H.; Zhang, D. Recent progress in nanotechnology-based drug carriers for resveratrol delivery. Drug Deliv. 2023, 30, 2174206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boocock, D.J.; Faust, G.E.S.; Patel, K.R.; Schinas, A.M.; Brown, V.A.; Ducharme, M.P.; Booth, T.D.; Crowell, J.A.; Perloff, M.; Gescher, A.J.; Steward, W.P.; Brenner, D.E. Phase I Dose Escalation Pharmacokinetic Study in Healthy Volunteers of Resveratrol, a Potential Cancer Chemopreventive Agent. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2007, 16, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, B.; Kwah, M.X.Y.; Liu, C.; Ma, Z.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Ding, L.; Xiang, X.; Ho, P.C.L.; Wang, L.; Ong, P.S.; Goh, B.C. Resveratrol for cancer therapy: Challenges and future perspectives. Cancer Lett. 2021, 515, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.T.; Zeng, X.F.; Yang, H.; Jia, M.L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, W.; Liu, S.Y. Resveratrol Loaded by Folate-Modified Liposomes Inhibits Osteosarcoma Growth and Lung Metastasis via Regulating JAK2/STAT3 Pathway. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2023, 18, 2677–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Hong, W.; Yu, M.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Ying, X. Multifunctional Targeting Liposomes of Epirubicin Plus Resveratrol Improved Therapeutic Effect on Brain Gliomas. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2022, 17, 1087–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.H.; Ko, Y.T. Enhanced Subcellular Trafficking of Resveratrol Using Mitochondriotropic Liposomes in Cancer Cells. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujioka, T.; Sasaki, D.; Takeda, A.; Harashima, H.; Yamada, Y. Resveratrol-Encapsulated Mitochondria-Targeting Liposome Enhances Mitochondrial Respiratory Capacity in Myocardial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzé, S.; Rama, F.; Rocco, P.; Debernardi, M.; Bincoletto, V.; Arpicco, S.; Cilurzo, F. Rationalizing the Design of Hyaluronic Acid-Decorated Liposomes for Targeting Epidermal Layers: A Combination of Molecular Dynamics and Experimental Evidence. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 3979–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenhoeft, T.; Tarantini, S.; Nyúl-Tóth, Á.; Yabluchanskiy, A.; Csipo, T.; Balasubramanian, P.; Lipecz, A.; Kiss, T.; Csiszar, A.; Csiszar, A.; Ungvari, Z. Fusogenic liposomes effectively deliver resveratrol to the cerebral microcirculation and improve endothelium-dependent neurovascular coupling responses in aged mice. Geroscience 2019, 41, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, S.; Qiao, M.; Jia, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.; Hu, H.; Chen, D. Construction of Hierarchical-Targeting pH-Sensitive Liposomes to Reverse Chemotherapeutic Resistance of Cancer Stem-like Cells. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, P.; Thumrongsiri, N.; Tanyapanyachon, P.; Chonniyom, W.; Punnakitikashem, P.; Saengkrit, N. Resveratrol Loaded Liposomes Disrupt Cancer Associated Fibroblast Communications within the Tumor Microenvironment to Inhibit Colorectal Cancer Aggressiveness. Nanomaterials 2022, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, K. A transcriptomic signature for prostate cancer relapse prediction identified from the differentially expressed genes between TP53 mutant and wild-type tumors. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanazi, A.; Yunusa, I.; Elenizi, K.; Alzarea, A.I. Efficacy and safety of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harboring epidermal growth factor receptor mutation: a network meta-analysis. Lung Cancer Manag. 2021, 10, LMT43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jøraholmen, M.W.; Johannessen, M.; Gravningen, K.; Puolakkainen, M.; Acharya, G.; Basnet, P.; Basnet, N.S. Liposomes-In-Hydrogel Delivery System Enhances the Potential of Resveratrol in Combating Vaginal Chlamydia Infection. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jøraholmen, M.W.; Damdimopoulou, P.; Acharya, G, Škalko-Basnet, N. Toxicity Assessment of Resveratrol Liposomes-in-Hydrogel Delivery System by EpiVaginalTM Tissue Model. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1295. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, R.; Wei, J.; Hou, J.; Wang, B.; Lai, H.; Huang, Y. Remodeling immune microenvironment in periodontitis using resveratrol liposomes as an antibiotic-free therapeutic strategy. J. Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousseau, C.P.V.; Sorroche, B.P.; de Jesus Teixeira, R.; de Carvalho, A.C.; Melendez, M.E.; de Castro Capuzzo, R.; Laus, A.C.; Sussuchi da Silva, L.; Soares de Menezes, N.; Lopes Carvalho, A.; Rebolho Batista Arantes, L.M. miR-99a-5p as a biomarker for lymph node metastasis prediction in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Head Neck 2023, 45, 2489–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markopoulos, A.K. Current Aspects on Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Open Dent J. 2012, 6, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.E.; Burtness, B.; Leemans, C.R.; Lui, V.W.Y.; Bauman, J.E.; Grandis, J.R. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2020, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antimisiaris, S.G.; Marazioti, A.; Kannavou, M.; Natsaridis, E.; Gkartziou, F.; Kogkos, G.; Mourtas, S. Overcoming barriers by local drug delivery with liposomes. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 174, 53–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesús Valle, M.J.; Sánchez Navarro, A. Liposomes Prepared in Absence of Organic Solvents: Sonication Versus Lipid Film Hydration Method. Curr. Pharm. Anal. 2015, 11, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesús Valle, M.J.; Coutinho, P.; Ribeiro, M.P.; Sánchez Navarro, A. Lyophilized tablets for focal delivery of fluconazole and itraconazole through vaginal mucosa, rational design and in vitro evaluation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 122, 144–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jesús Valle, M.; Gil González, P.; Prata Ribeiro, M.; Araujo, A.; Sánchez Navarro, A. Sildenafil Citrate Liposomes for Pulmonary Delivery by Ultrasonic Nebulization. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesús Valle, M.J.; Maderuelo Martín, C.; Zarzuelo Castañeda, A.; Sánchez Navarro, A. Albumin micro/nanoparticles entrapping liposomes for itraconazole green formulation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, I.; Arora, S.; Rana, V.; Arora, G.; Malik, K. Formulation and evaluation of controlled release matrix mucoadhesive tablets of domperidone using Salvia plebeian gum. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2011, 2, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.O.; McConville, J.T. Manufacture and characterization of mucoadhesive buccal films. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2011, 77, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales Chahara, F.; Díazb, S.B.; Ben Altabef, F.A.; Alvarez, P.E. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. In 2019. p. 60–69.

- Farzaneh, H.; Ebrahimi Nik, M.; Mashreghi, M.; Saberi, Z.; Jaafari, M.R.; Teymouri, M. A study on the role of cholesterol and phosphatidylcholine in various features of liposomal doxorubicin: From liposomal preparation to therapy. Int. J. Pharm.

- Neves, A.R.; Queiroz, J.F.; Reis, S. Brain-targeted delivery of resveratrol using solid lipid nanoparticles functionalized with apolipoprotein E. J. Nanobiotechnology 2016, 14, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meleleo, D. Study of Resveratrol’s Interaction with Planar Lipid Models: Insights into Its Location in Lipid Bilayers. Membranes 2021, 11, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardešić, I.; Boban, Z.; Subczynski, W.K.; Raguz, M. Membrane Models and Experiments Suitable for Studies of the Cholesterol Bilayer Domains. Membranes 2023, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, B.; Kwah, M.X.Y.; Liu, C.; Ma, Z.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Ding, L.; Xiang, X.; Chi-Lui Ho, P.; Wang, L.; Shi Ong, P.; Cher Goh, B. Resveratrol for cancer therapy: Challenges and future perspectives. Cancer Lett. 2021, 515, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).