1. Introduction

Doxorubicin (DOX) is an anthracycline antibiotic isolated from

Streptomyces peucetius caesius that attained US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 1974 [

1]. Following its approval, DOX became one of the most widely prescribed chemotherapeutic agents due to its broad-spectrum activity against both solid and metastatic cancers such as breast cancer, lymphomas, and leukemias [

1,

2]. Following entry into a cancer cell, DOX inhibits tumor progression through three purported mechanisms. Firstly, it binds to the 26S proteasome found in the cytoplasm enabling its entry into the nucleus where is intercalates with the DNA resulting inhibition of DNA replication and transcription; secondly, once in the nucleus it also intercalates with topoisomerase II disrupting DNA repair; and lastly in the cytoplasm DOX is oxidized to DOX-semiquinone which results in production of free radicals such as, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and disruption of the cell membrane [

3,

4].

Despite DOX’s broad-spectrum activity, its clinical use is limited due to both its detrimental dose-dependent and cumulative dose, dosage surpassing 400–700 mg/m2 for adults and 300 mg/m2 for children, effects such as DOX-induced cardiotoxicity (DIC), heart failure, and secondary malignancies [

1,

5]. DIC clinically presents as left ventricular dysfunction, arrhythmias primarily atrial fibrillation, and congestive heart failure [

6,

7]. Consequently, the underlying mechanisms involved in DIC have been extensively researched. Multiple studies have suggested that the three major sources of cell damage in DIC are: (1) mitochondrial dysfunction; (2) increase oxidative stress resulting in excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS); and (3) topoisomerase 2β inhibition resulting in multiple double stranded breaks [

1,

6]. Additionally, studies have also shown the involvement of both regulated and unregulated cell death pathways, autophagy, necroptosis, ferroptosis, pyroptosis, and apoptosis, in DIC [

6,

8,

9]. Therefore, it is believed that the molecular pathogenesis of DIC is multi-factorial with concurrent triggering of cell death pathways [

1,

6,

10].

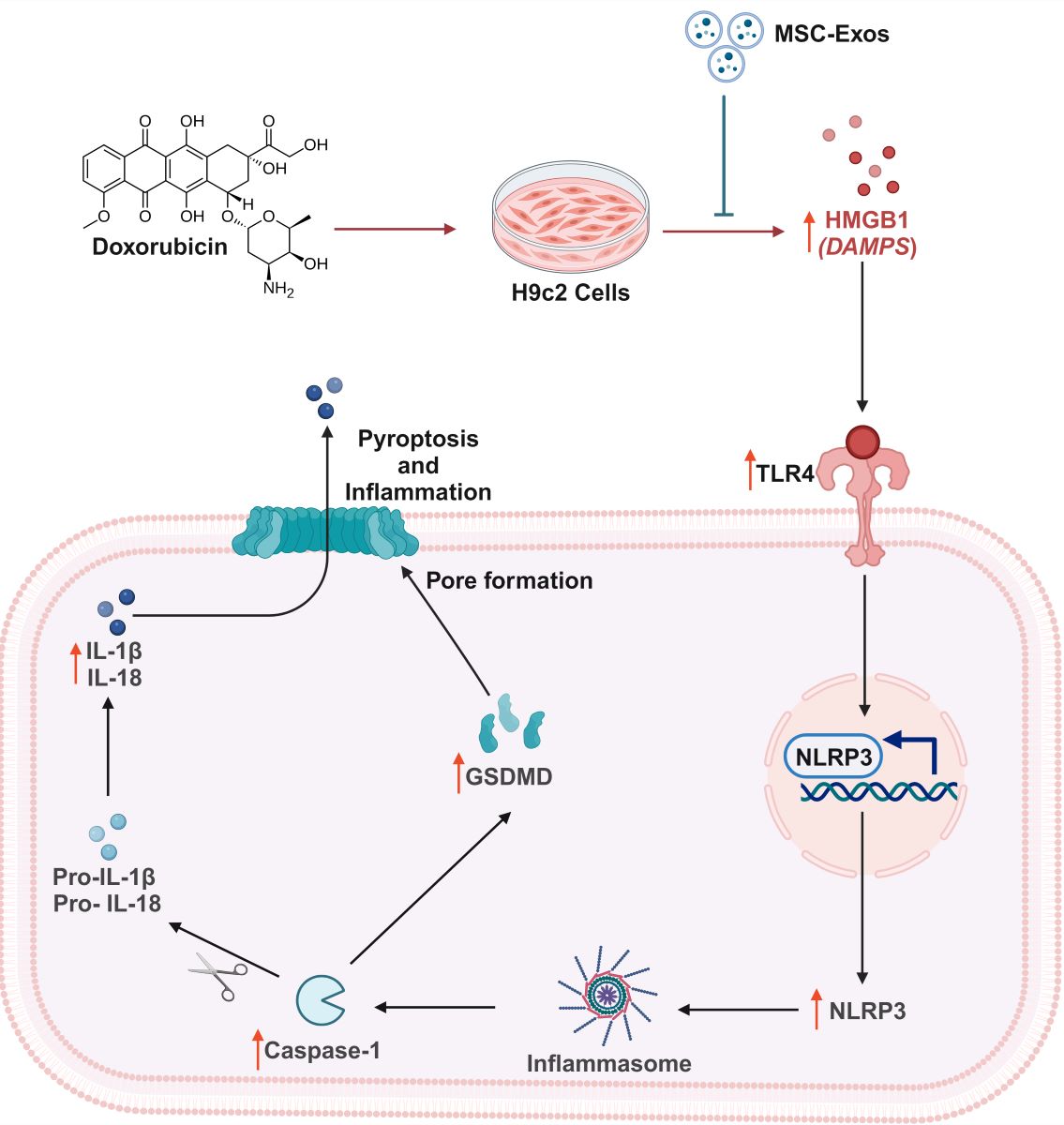

As previously mentioned, pyroptosis is one of the cell death pathways implicated in the pathogenesis of DIC [

9]. Pyroptosis is a form of inflammation-mediated cell death that is characterized by the activation of the inflammasome and maturation of pro-inflammatory cytokines [

11]. It is a distinct form of regulated cell death in that the pore executioner is gasdermin D (GSDMD), leads to nuclear condensation, cell swelling, and membrane rupture [

12]. Furthermore, pyroptosis is activated by pro-inflammatory cytokines, pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), and damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [

1]. DOX administration has been demonstrated to lead to an increase expression of high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), a known DAMP, that interacts with toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), a receptor shown to play a key role in DOX-induced inflammation [

13,

14]. Following TLR4 activation, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) is triggered leading to formation of the "NOD-like" receptor pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome which activates Caspase-1 [

11,

13]. Activated caspase-1 then cleaves pro-IL-1β, pro-IL-18, and gasdermin D (GSDMD) leading to maturation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and formation of the GSDMD pore, a key executioner of pyroptosis [

9,

15].

As a result, there is a need for discovering novel therapeutic approaches to counteract the cardiotoxic effects of DOX. With this aim, numerous studies have investigated stem cells as potential cell-based therapies for DIC [

16]. Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) have been evaluated due to their ability to differentiate into cardiomyocytes which can be implanted in the heart to improve heart function, however, there are associated bioethical restrictions regarding the use of ESCs [

16]. An alternative cell-based strategy researched are induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) as they do not have ethical restrictions like ESCs but can be tumorigenic and are genetically unstable [

17,

18]. As a result, further studies have identified adult mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) as a suitable tool for both regenerative and preventative therapy for DIC [

16]. MSCs exert their cardioprotective effects through paracrine secretion of various growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines that aid in cardiac regeneration and repair [

19]. Nonetheless, MSCs have their own disadvantages such as weak myocardial homing, teratoma formation, and decrease viability following transplantation [

19]. Though, numerous studies have shown that the therapeutic potential of MSCs are mainly exerted by their paracrine effects, for example by paracrine factors such as exosomes [

20].

Exosomes are nanosized extracellular vesicles (30-200 nm diameter) that are generated through the endocytic pathway and are released by exocytosis and dependent on their cell origin, carry a variety of consitutents such as DNA, microRNA (miRNA), proteins, lipids, and metabolites [

21]. MSCs derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) preserve the therapeutic properties of MSCs without the associated disadvantages of stem cell therapy. MSC-Exos avoid the risk of becoming tumorigenic as they are not self-replicating, have biocompatibility and low immunogenicity, and an adequate number can be attained since they can be continuously secreted from immortalized cells [

20,

22]. Furthermore, MSC-Exos have shown to reduce apoptosis and cardiac fibrosis in myocardial infracted mice, promote angiogenesis, and promote cardiomyocyte proliferation [

23,

24]. However, whether MSC-Exos can attenuate DOX-induced proptosis in an

in vitro model has never been reported.

Therefore, the current study aims to investigate the therapeutic potential of MSC-Exos in attenuating DOX-induced pyroptosis in cardiomyocytes. Thus, leading to the identification of a novel therapeutic approach that can be effective at countering the cardiotoxicity induced by DOX.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Derived-Exosomes

C57BL/6 mouse bone MSCs were purchased from OriCell (Roseland, NJ, USA). Briefly, MSCs were cultured with mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells complete medium (OriCell, Roseland, NJ, USA). MSCs were cultured in T75 flask with complete medium for 48 hours, then replaced with serum-free knockout Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and cells were grown for an additional 48 hours. Next, the culture medium was collected, centrifuged, and supernatant was collected in sterile tubes and combined with Exoquick-TC Exo precipitation solution (System Biosciences (SBI) , Palo Alto, CA, USA) in accordance with manufacturer’s instruction. Following incubation, tubes were centrifuged, supernatant was aspirated, exosome pellet was collected.

2.2. MSC Exosome Confirmation and Characterization

Isolated Exos were confirmed via flow cytometry analysis with CellTrace™ Violet (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) as previously published [

25]. In brief, isolated Exos were incubated with CellTrace reagent for 20mins at 37°C. Following labelling, flow cytometry analysis was accomplished using the CytExpert Software for the CytoFLEX Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter).

Exo pellet was then characterized by through western blot for specific protein biomarkers for exosomes, namely CD63 and heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) as published [

9]. In brief, exosomal protein were extracted by reconstitution with radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (RIPA) and the concentration of isolated protein was acquired using the Bio-Rad protein assay. The extracted protein (50μg) and ladder (SeeBlue Plus2 Prestained Standard) were loaded onto 4-12% Bolt gels and ran for 22 mins at 200V followed by transfer to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane using the iBlot2 Gel Transfer Device. Membranes were then incubated with antibodies CD63 (1:1,000; SBI, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and HSP70 (1:1,000; SBI, Palo Alto, CA, USA).

2.3. H9c2 Cell Culture

Rat embryonic cardiomyocytes cells (H9c2) purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) were maintained in cell culture flasks with DMEM (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), penicillin/streptomycin (P/S; ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), sodium pyruvate (NaP; ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), glutamine (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and non-essential amino acids (NEAA, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37˚C in the presence of 5% CO2.

2.4. MTT Assay

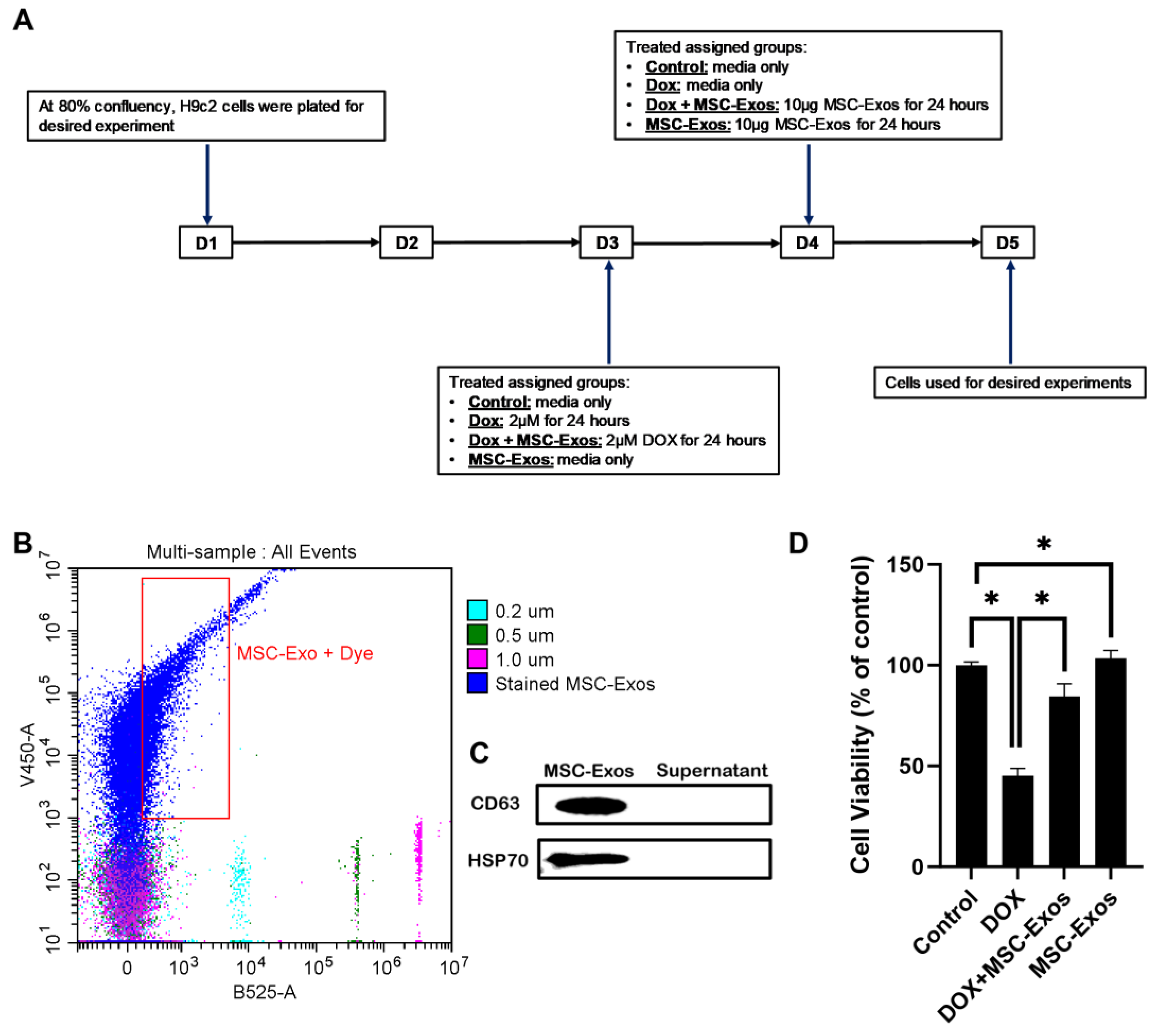

H9c2 cells were cultured in 96-well plates (10,000 cells/well) until ≈60-80% then divided into 4 groups: (1) Control; (2) DOX; (3) DOX+MSC-Exos; (4) MSC-Exos (exosome control). Briefly, group 1 and group 4 H9c2 cells were cultured in growth media, while group 2 and 3 cells were treated with 2μM DOX (prepared in sterilized water) for 24 hours. Following the 24 hour incubation, media from all groups were removed. Subsequently, groups 1 and 2 cells received fresh growth media, while groups 3 and 4 cells received 10μg of MSC-Exos Exos and cells were cultured for an additional 24 hours (

Figure 1A). After the treatment period, MTT (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) was performed following the manufacturer’s protocol as previously published [

26]. Briefly, MTT reagent was added to each well for 4 hours at 37˚C resulting in the formation of formazan crystal which was then solubilized and incubated overnight. Following the incubation, absorbance was measured at 550nm and 650nm (background) using the SpectraMAX i3 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader. Cell viability was calculated as a percent of control.

2.5. Immunocytochemistry (ICC) Staining

H9c2 cells were cultured in eight-chamber slides (10,000 cells/chamber) and treated as previously described (

Figure 1A). Following treatment, slides were washed with sterile 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X in the dark. Following permeabilization, slides were then blocked and incubated with primary antibodies: HMGB1 (1:250; Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA), TLR4 (1:250; Abcam Waltham, MA, USA), NLRP3 (1:250; LifeSpan BioSciences, Shirley, MA, USA), caspase-1 (1:250; Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA), IL-1β (1:250; Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA), IL-18 (1:250; Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA), and GSDMD (1:250; Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA) overnight at 4˚C. Following primary antibody incubation, cells were washed with 1X PBS and incubated with secondary antibody Alexa 568 (anti-rabbit, 1:1000; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at room temperature (RT). Lastly, slides were washed and counterstained using Vectashield Antifade mounting medium containing 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to stain the nuclei and mounted with coverslips.

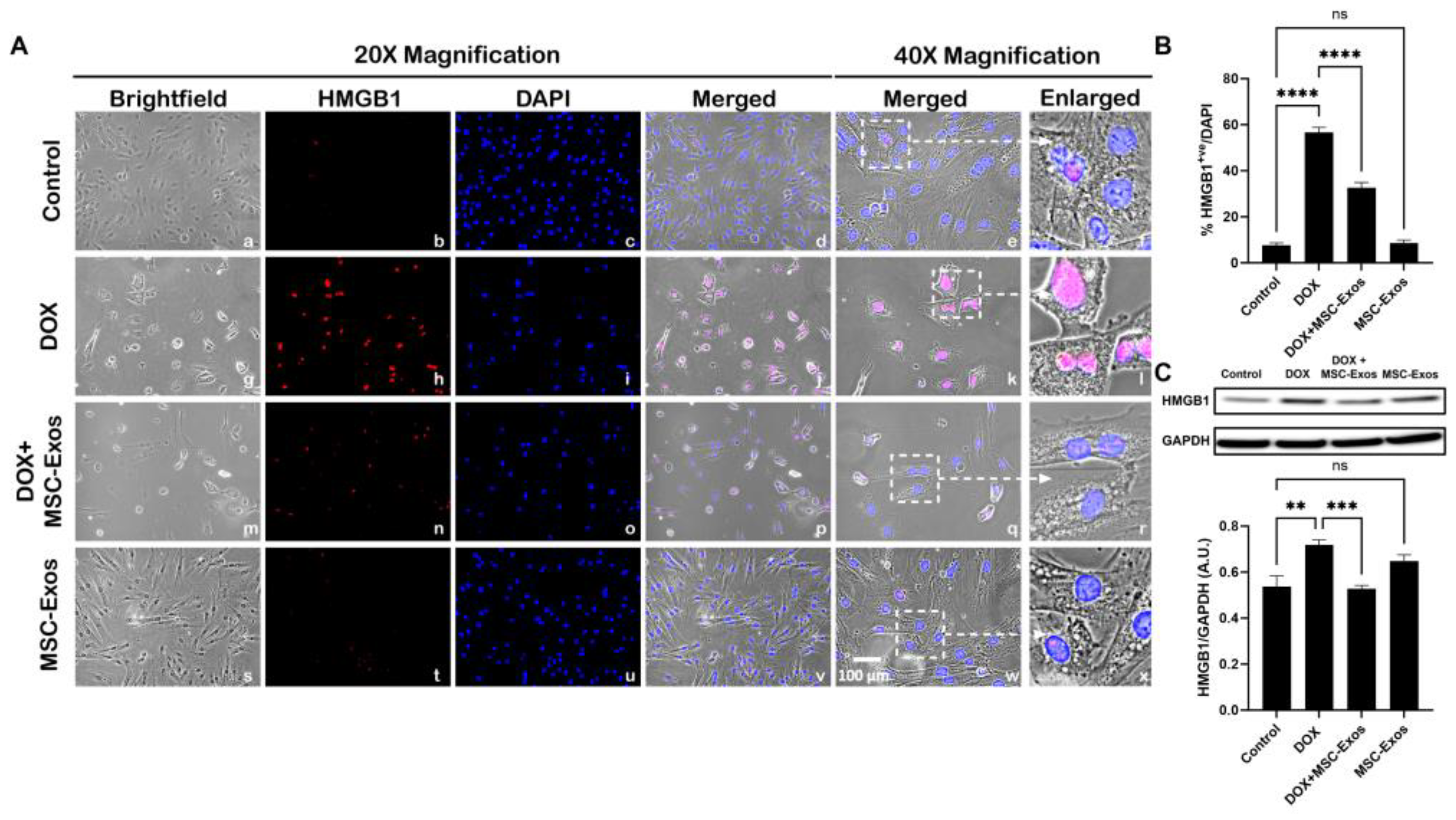

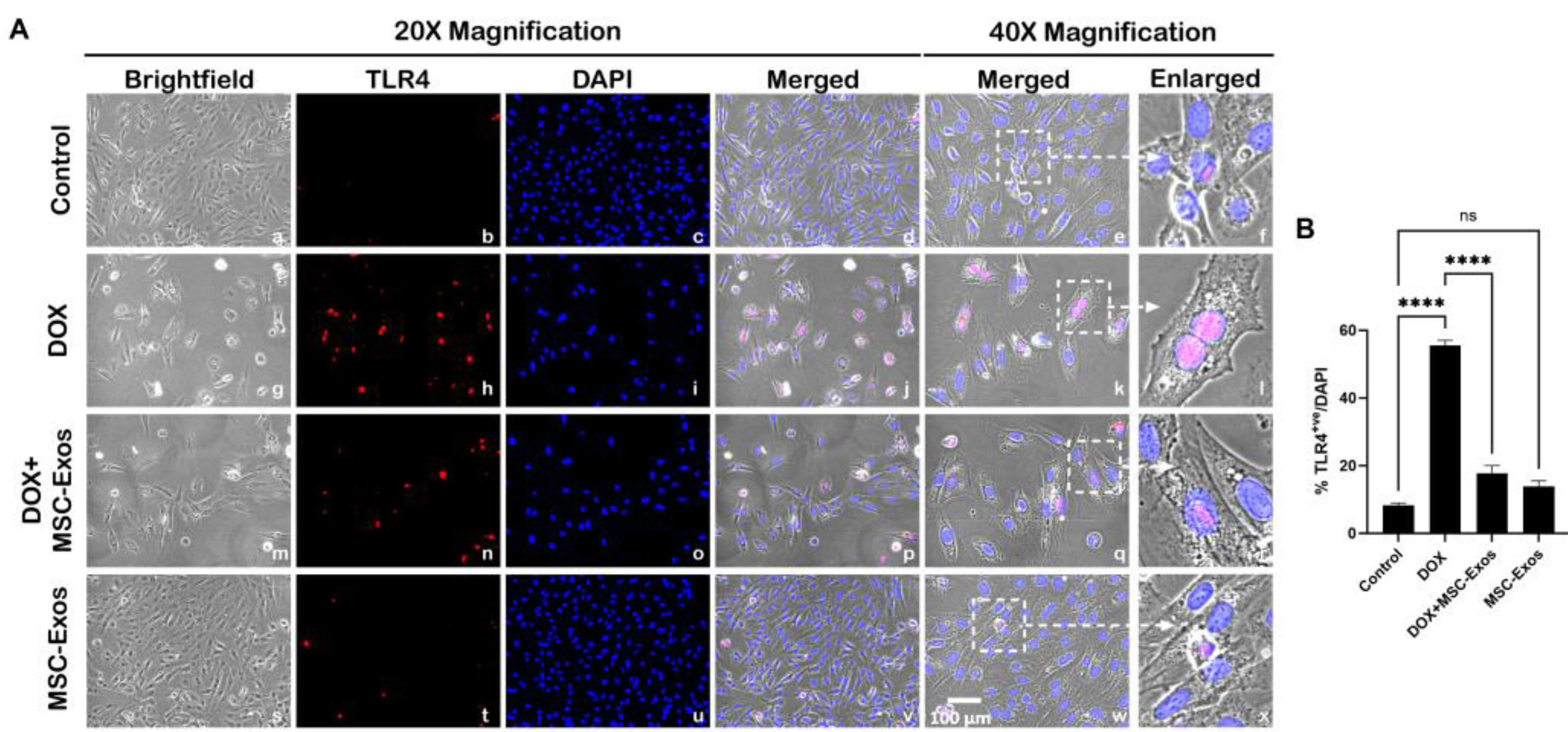

Images for quantification were taken using the 20X magnification and representative images were taken using the 40X magnification on the BZ-X810 Keyence microscope. The percentage of pyroptotic cell death were determined by evaluating the number of positively stained cells (in red) over the total DAPI+ve (in blue) multiplied by 100 [(total cells+ve/total DAPI+ve) x 100) using the ImageJ software. Bar graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism software.

2.6. Western Blot

H9c2 cells were cultured in 100mm2 dishes (500,000 cells/dish) adhering to the previously described treatment plans (

Figure 1A). After the treatment period, cells were lysed using RIPA and the resultant cell lysate was obtained. Bio-Rad protein assay was utilized to elucidate in concentration of isolated proteins. The protein samples (25μg) and ladder (SeeBlue Plus2 Prestained Standard) were loaded onto 4-12% Bolt gels and ran for 22 mins at 200V followed by transfer to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane using the iBlot2 Gel Transfer Device as previously published [

27]. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk, incubated overnight at 4˚C with primary antibodies (1:1000) specific for pyroptotic markers (HMGB1, caspase-1, IL-1β, and GSDMD), followed with incubation with secondary antibody (anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody, 1:1000; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) before imaging with the Sapphire Biomolecular Imager. Densitometric analyses were performed using Image J software and all bands were normalized to the loading control glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) and expressed in arbitrary units (A.U.). Bar graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism software.

2.7. RT-PCR

H9c2 cells were cultured in 60mm2 dishes (200,000 cells/dish) adhering to the previously described treatment plans (

Figure 1A). After treatment period, TRIzol reagent was utilized to extract total RNA, cDNA (SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix for qRT-PCR; ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) was reverse transcribed, and RT-PCR was performed to evaluate the gene expression levels for NLRP3 (

Table 1) as previously described [

27]. GAPDH was used as the housekeeping gene to normalize the fold expression. Bar graph was generated using GraphPad Prism software.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was assessed at p<0.05 through the analysis of data using both Student’s T-Test and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test for post hoc comparisons. Data representation in graphs was made utilizing using GraphPad Prism software, and values are presented as means ± SEM.

4. Discussion

Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity (DIC) is multifaceted in nature, encompassing not only mitochondrial dysfunction and production of ROS, but also involvement of multiple cell death pathways. In the early stages of DOX therapy, asymptomatic and symptomatic cardiomyopathy highlighted by epigenetic changes and cellular injury presents and then later develops to abnormal cell signaling resulting in cardiac dysfunction, fibrosis, endothelial injury, and hypotensive remodeling [

31]. All together these events result in congestive heart failure, a detriment that is of mounting concern as cancer survivors are increasing in number.

In recent years, novel exosome therapeutics aimed at cardiac regeneration and repair have garnered interest. Traditionally, strategies employed to reduce DIC is to alter the delivery mechanism of DOX by encapsulating it in a liposome therefore changing its biodistribution; however, this limits the use to specific cancers due to its high cost [

7]. Alternatively, a drug that targets topoisomerase IIβ enzyme and reduce iron-mediated production of oxidative radicals like the FDA approved drug dexrazoxane have been used to counter DIC; however, it has associated restrictions because it was seen to increase the incidence of secondary malignancies [

7]. Furthermore, various cell-based therapies such as stem cell have been investigated; nonetheless, there are constraints in their use due to the associated teratoma formation, weak myocardial homing, and weak viability following transplantation [

23]. Hence, employing a cell-free alternative that retains the advantages associated with stem cells such as stem-cell derived exosomes would present a novel therapeutic intervention that would have greater efficacy in countering DIC.

Mesenchymal stem cell derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) secrete diverse factors that result in anti-inflammatory, pro-angiogenic, anti-apoptotic, and anti-fibrotic outcomes following intravenous and intramyocardial transplantation [

32]. Furthermore, a prior study has identified that pre-treatment with MSC-derived small extracellular vesicles attenuated DOX-induced apoptosis through upregulation of survivin [

33]. Therefore, further investigation into the impact of MSC-Exos on the multifaceted regulated cell death pathways implicated in DIC could contribute to uncovering the robust therapeutic potential of MSC-Exos as a cell-free therapeutic.

In this study, we explored the therapeutic potential of MSC-Exos, a cell-free alternative to MSCs, in attenuation of pyroptosis, inflammation-mediated cell death, in our established in vitro DIC model. In this context, our investigation is the first to accentuate the ability of MSC-Exos to attenuate the HMBG1/TLR4 axis and NLRP3 inflammatory cascade.

DOX treatment mediates the upregulation of HMGB1, a DAMP and upstream activator of pyroptotic cell death. Further to this, HMGB1 is an extracellular molecule that triggers inflammatory responses under conditions such as sepsis and myocardial infraction and carries out its biological role through its receptor TLR4 [

14,

29]. Studies have depicted that DOX treatment specifically results in an increased secretion of HMGB1 in the heart and brain [

14,

34]. However, it is unknown whether MSC-Exos treatment would attenuate the DOX-induced upregulation of HMGB1. Data presented in current study depicts that DOX treatment ensued a heighten expression of HMGB1 in cardiomyocytes, thereby corroborating with other published studies on HMGB1 upregulation following DOX treatment [

14,

29,

34]. Further to this, MSC-Exos treatment resulted in a substantial reduction in HMGB1 in comparison to DOX group. A justification behind MSC-Exos ability to attenuate the expression of HMGB1 lies in substantiated studies indicating the anti-inflammatory effects of MSC-Exos along with its cardioprotective potential [

32].

Aforementioned the receptor for HMGB1 is TLR4, a constituent of the innate immune system that belongs to the TLR family and thereby responds to both endogenous and exogenous signals thereby triggering various pathophysiological functions such as pyroptotic cell death upstream of NLRP3 [

13]. Furthermore, TLR4 is not only expressed on immune cells but are also expressed in the heart and brain following DOX administration [

9,

13,

35]. Henceforth, to further understand the significance of HMGB1 downregulation upon MSC-Exos administration, we assessed TLR4. Our data validates that elevated HMGB1 results in an upregulation of TLR4, while MSC-Exos treatment substantially reduced levels, indicating the ability of MSC-Exos to inhibit TLR4. MSC-Exos is known to release microRNAs that can inhibit TLR4 signaling [

36]. Hence, the reduced TLR4 expression observed following MSC-Exos treatments could be a result of decreased HMGB1 expression therein reducing TLR4 activation as previously mentioned or directly due to factors released from the MSC-Exos.

TLR4 signaling activates the NLRP3 inflammasome, a mediator of pyroptotic cell death. NLRP3, pro-caspase-1, and apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC) constitutes the NLRP3 inflammasome which self-cleaves to form active caspase-1 [

9,

27]. Therefore, further we investigated the effect of MSC-Exos on NLPR3 and caspase-1 after DOX treatment; aimed to strengthen the validation of MSC-Exos' therapeutic efficacy in regulating the HMGB1/TLR4/NLRP3 inflammatory cascade. Our data exhibits that DOX treatment increases the expression of NLRP3 and caspase-1 thereby agreeing with previously published data while MSC-Exos reduced these levels.

Additionally, caspase-1 cleaves and initiates pro-inflammatory cytokines pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 to their active form, IL-1β and IL-18, and GSDMD to N-GSDMD, the pyroptotic executioner that forms membrane pores through which the pro-inflammatory cytokines are released [

9,

35]. Our data demonstrates that MSC-Exos reduced the DOX-induced upregulation of IL-1β, IL-18, and GSDMD. Taken together, these findings indicate for the first time that MSC-Exos targets DOX-induced HMGB1 upregulation thereby attenuating the downstream pyroptotic cascade. Moreover, our study corroborates with established studies that illustrate the therapeutic potential of MSC-Exos in myocardial infraction and heart failure models [

35,37,38]. However, additional studies are necessary to understand the specific factors released by MSC-Exos that elicits the therapeutic effects.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates for the first time that MSC-Exos attenuates DOX-induced: (1) HMGB1/TLR4 axis; (2) NLRP3 inflammatory cascade; and (3) GSDMD pore formation, resulting in diminished pyroptosis. These findings indicate a decrease in HMGB1 and further reduction in pyroptosis suggesting that MSC-Exos attenuates the upstream HMGB1/TLR4 axis; however, the possibility that MSC-Exos could have potential direct effect on the pyroptotic pathways (caspase-1, IL-1β, IL-18) and pyroptotic executioner GSDMD need to be further explored. Furthermore, the current study was conducted in our cell culture system; consequently, further studies are required in an in vivo DIC model to strengthen our findings. Moreover, this study provide evidence that MSC-Exos can be a prospective therapeutic agent to counter DOX-induced cardiotoxicity as it preserves the potential of MSCs without the associated disadvantages of stem cell therapy.

Figure 1.

MSC-Exos Characterization and Ability to Alleviate DOX-induced Reduction in Cell Viability. (A) Schematic representation of the study design. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of violet labeled isolated MSC-Exos (black box) and green labeled sizing beads. (C) Western blot confirmation of exosomes protein biomarkers CD63 and HSP70. (D) MSC-Exos reversed the reduction in cell viability induced by DOX, as assessed using MTT assay. Error bar denotes standard mean error (SEM). *p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

MSC-Exos Characterization and Ability to Alleviate DOX-induced Reduction in Cell Viability. (A) Schematic representation of the study design. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of violet labeled isolated MSC-Exos (black box) and green labeled sizing beads. (C) Western blot confirmation of exosomes protein biomarkers CD63 and HSP70. (D) MSC-Exos reversed the reduction in cell viability induced by DOX, as assessed using MTT assay. Error bar denotes standard mean error (SEM). *p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

MSC-Exos Diminishes Pyroptotic Initiator HMGB1 in an In Vitro DIC Model. (A) Representative photomicrographs depict 20x brightfield snapshots, HMGB1+ve cells (red), DAPI (blue), and merged 20x snapshots. 40x brightfield merged snapshots and white dotted boxes with arrows denote expanded area of 40x snapshots. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) MSC-Exos reduces proportion of HMGB1+ve cells induced by DOX. (C) HMGB1was assessed in cell lysates followed by densitometric analysis. Error bar denotes SEM. **p < 0.002, ***p < 0.0006, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 2.

MSC-Exos Diminishes Pyroptotic Initiator HMGB1 in an In Vitro DIC Model. (A) Representative photomicrographs depict 20x brightfield snapshots, HMGB1+ve cells (red), DAPI (blue), and merged 20x snapshots. 40x brightfield merged snapshots and white dotted boxes with arrows denote expanded area of 40x snapshots. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) MSC-Exos reduces proportion of HMGB1+ve cells induced by DOX. (C) HMGB1was assessed in cell lysates followed by densitometric analysis. Error bar denotes SEM. **p < 0.002, ***p < 0.0006, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

MSC-Exos Reduced TLR4 Expression an In Vitro DIC Model. (A) Representative photomicrographs depict 20x brightfield snapshots, TLR4+ve cells (red), DAPI (blue), and merged 20x snapshots. 40x brightfield merged snapshots and white dotted boxes with arrows denote expanded area of 40x snapshots. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) MSC-Exos reduces pyroptotic proportion of TLR4+ve cells induced by DOX. Error bar denotes SEM. ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

MSC-Exos Reduced TLR4 Expression an In Vitro DIC Model. (A) Representative photomicrographs depict 20x brightfield snapshots, TLR4+ve cells (red), DAPI (blue), and merged 20x snapshots. 40x brightfield merged snapshots and white dotted boxes with arrows denote expanded area of 40x snapshots. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) MSC-Exos reduces pyroptotic proportion of TLR4+ve cells induced by DOX. Error bar denotes SEM. ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

MSC-Exos Decreases NLRP3 Inflammasome Formation in an In Vitro DIC Model. (A) Representative photomicrographs depict 20x brightfield snapshots, NLRP3+ve cells (red), DAPI (blue), and merged 20x snapshots. 40x brightfield merged snapshots and white dotted boxes with arrows denote expanded area of 40x snapshots. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) MSC-Exos reduces proportion of NLRP3+ve cells induced by DOX. (C) Relative fold change of NLRP3. Error bar denotes SEM. **p < 0.002, ***p < 0.0006, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

MSC-Exos Decreases NLRP3 Inflammasome Formation in an In Vitro DIC Model. (A) Representative photomicrographs depict 20x brightfield snapshots, NLRP3+ve cells (red), DAPI (blue), and merged 20x snapshots. 40x brightfield merged snapshots and white dotted boxes with arrows denote expanded area of 40x snapshots. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) MSC-Exos reduces proportion of NLRP3+ve cells induced by DOX. (C) Relative fold change of NLRP3. Error bar denotes SEM. **p < 0.002, ***p < 0.0006, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

MSC-Exos Mitigates Pyroptotic Cascade Marker Caspase-1 in an In Vitro DIC Model. (A) Representative photomicrographs depict 20x brightfield snapshots, Caspase-1+ve cells (red), DAPI (blue), and merged 20x snapshots. 40x brightfield merged snapshots and white dotted boxes with arrows denote expanded area of 40x snapshots. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) MSC-Exos reduces proportion of Caspase-1+ve cells induced by DOX. (C) Caspase-1 was assessed in cell lysates followed by densitometric analysis. Error bar denotes SEM. *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

MSC-Exos Mitigates Pyroptotic Cascade Marker Caspase-1 in an In Vitro DIC Model. (A) Representative photomicrographs depict 20x brightfield snapshots, Caspase-1+ve cells (red), DAPI (blue), and merged 20x snapshots. 40x brightfield merged snapshots and white dotted boxes with arrows denote expanded area of 40x snapshots. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) MSC-Exos reduces proportion of Caspase-1+ve cells induced by DOX. (C) Caspase-1 was assessed in cell lysates followed by densitometric analysis. Error bar denotes SEM. *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 6.

MSC-Exos Mitigates Pyroptotic Cascade Marker IL-1β in an In Vitro DIC Model. (A) Representative photomicrographs depict 20x brightfield snapshots, IL-1β+ve cells (red), DAPI (blue), and merged 20x snapshots. 40x brightfield merged snapshots and white dotted boxes with arrows denote expanded area of 40x snapshots. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) MSC-Exos reduces proportion of IL-1β+ve cells induced by DOX. (C) IL-1β was assessed in cell lysates followed by densitometric analysis. Error bar denotes SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.002, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 6.

MSC-Exos Mitigates Pyroptotic Cascade Marker IL-1β in an In Vitro DIC Model. (A) Representative photomicrographs depict 20x brightfield snapshots, IL-1β+ve cells (red), DAPI (blue), and merged 20x snapshots. 40x brightfield merged snapshots and white dotted boxes with arrows denote expanded area of 40x snapshots. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) MSC-Exos reduces proportion of IL-1β+ve cells induced by DOX. (C) IL-1β was assessed in cell lysates followed by densitometric analysis. Error bar denotes SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.002, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 7.

MSC-Exos Mitigates Pyroptotic Cascade Marker IL-18 in an In Vitro DIC Model. (A) Representative photomicrographs depict 20x brightfield snapshots, IL-18+ve cells (red), DAPI (blue, and merged 20x snapshots. 40x brightfield merged snapshots and white dotted boxes with arrows denote expanded area of 40x snapshots. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B MSC-Exos reduces proportion of IL-18+ve cells induced by DOX. Error bar denotes SEM. ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 7.

MSC-Exos Mitigates Pyroptotic Cascade Marker IL-18 in an In Vitro DIC Model. (A) Representative photomicrographs depict 20x brightfield snapshots, IL-18+ve cells (red), DAPI (blue, and merged 20x snapshots. 40x brightfield merged snapshots and white dotted boxes with arrows denote expanded area of 40x snapshots. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B MSC-Exos reduces proportion of IL-18+ve cells induced by DOX. Error bar denotes SEM. ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 8.

MSC-Exos Attenuates Pyroptotic Executioner GSDMD in an In Vitro DIC Model. (A) Representative photomicrographs depict 20x brightfield snapshots, GSDMD+ve cells (red), DAPI (blue), and merged 20x snapshots. 40x brightfield merged snapshots and white dotted boxes with arrows denote expanded area of 40x snapshots. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) MSC-Exos reduces proportion of GSDMD+ve cells induced by DOX. (C) GSDMD was assessed in cell lysates followed by densitometric analysis. Error bar denotes SEM. *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 8.

MSC-Exos Attenuates Pyroptotic Executioner GSDMD in an In Vitro DIC Model. (A) Representative photomicrographs depict 20x brightfield snapshots, GSDMD+ve cells (red), DAPI (blue), and merged 20x snapshots. 40x brightfield merged snapshots and white dotted boxes with arrows denote expanded area of 40x snapshots. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) MSC-Exos reduces proportion of GSDMD+ve cells induced by DOX. (C) GSDMD was assessed in cell lysates followed by densitometric analysis. Error bar denotes SEM. *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

Table 1.

RT-PCR Rat Primers.

Table 1.

RT-PCR Rat Primers.

| Table . |

Forward Primer |

Reverse Primer |

| NLRP3 |

5ʹ- GGTGACCTTGTGTGTGCTTG-3ʹ |

5ʹ- ATGTCCTGAGCCATGGAAGC-3ʹ |

| GAPDH |

5ʹ-GCCCACTAAAGGGCATCCTG-3ʹ |

5ʹ-GAGTTGGGATGGGGACTCTCA-3ʹ |