1. Introduction

Solar radiation is a significant factor contributing to the acceleration of skin aging through impairment of metabolism in the skin cells. Two mechanisms of this harmful effects are recognized, the first involves the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), the second, UV radiation induced DNA damage. Both processes contribute to deregulation of metabolism in the skin cells, inhibition of collagen biosynthesis and induction of cell death through apoptosis [

1,

2]. As a result, collagen metabolism is impaired at transcriptional and post-transcriptional level. At transcriptional level UVA induces NF-kB expression, the inhibitor of collagen gene transcription [

3]. Post-transcriptionally it impairs prolidase activity, the enzyme providing proline from imidodipeptides for collagen biosynthesis [

4]) and activates matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) that degrade collagen extracellularly [

5]. In addition, collagen also plays a critical role in regulating cellular metabolism as a ligand of integrin receptors. Integrin receptors participate in signaling that regulates collagen biosynthesis and prolidase activity [

4]. Both processes are stimulated by the insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I), the most potent factor stimulating collagen biosynthesis [

6]. Under physiological conditions, the activation of β1-integrin and IGF-I receptors initiate a cascade of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAP-kinase) signaling pathway, including extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK-1 and ERK-2) [

4]. It is well established that ROS down-regulate expression of MAP kinase ERK1/2 and support expression of stress-activated kinases, JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) and p38. The effectors of MAP kinases are transcription factors, including c-Jun and c-Fos, which form the activating protein complex AP-1 (activating protein-1). This protein plays important role in regulation of collagen metabolism as inhibitor of pro-collagen type I gene expression and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling pathway [

7,

8,

9].

Chronic exposure to UVA induces inflammation in the skin, resulting in the release of cytokines and proinflammatory factors, including the nuclear transcription factor NF-κB (Nuclear factor kappa B) [

5,

10,

11]. Activated NF-κB plays an important role in regulating the expression of various genes involved in immune and inflammatory responses, including the expression of cyclooxygenase COX-2, an enzyme associated with the inflammatory process [

12].

Seed oil derived from

Amaranthus cruentus L. (AmO) is considered a promising source of bioactive compounds of anti-oxidative potential [

13]. Its use may contribute to various health benefits, including anti-oxidant, anti-cancer, anti-allergic and anti-hypertensive activity. The oil obtained from the cold-pressing of

Amaranthus cruentus L. has a relatively low lipid content, approximately 7-8%. However, these lipids are valuable for health due to the presence of unsaturated fatty acids, tocopherols, tocotrienols, phytosterols, and squalene, which are not commonly found together in other oils.

The effect of AmO on collagen metabolism and wound healing in cells exposed to UVA radiation is currently unknown. Given the oil's rich composition of bioactive compounds, it has the potential to exhibit protective effects not only against oxidative stress but also other metabolic disturbances induced by UV radiation. This study aims to investigate the effect of AmO on collagen biosynthesis and wound healing process in human skin fibroblasts exposed to UVA radiation.

2. Results and Discussion

Prolonged exposure of skin to UV radiation leads to generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the skin cells. They cause a redox imbalance, deregulation of collagen synthesis and damage to DNA, proteins and lipids. They also affect the integrity of biological membranes of skin cells, fibroblasts and keratinocytes [

5]. In our previous study we found that exposure of fibroblasts to different doses of UVA radiation contributed to decrease in the cell viability in a UVA dose-dependent manner [

13]. Based on these data, in present study we have selected a dosage of 10 J/cm

2, which was IC50 value for cell viability in our experimental protocols [

13] to evaluate the effect of Amaranthus cruentus L. seed oil (AmO) on collagen metabolism and wound healing.

Plant oils are among the cosmetic materials that demonstrate beneficial effects on the skin, due to their chemical composition, primarily the presence of Essential Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs), as well as other components of the unsaponifiable fraction, such as squalene, phytosterols, and tocopherols [

14]. AmO, in this regard, is characterized by a favorable chemical composition, containing approximately 60% linoleic acid, 8- 10% squalene, and tocopherols, thus demonstrating protective and antioxidant potential against UV radiation. In our previous study we demonstrated that fibroblasts viability decreased to approximately 55% of the control value when exposed to 10 J/cm

2 UVA radiation dose. We have found that in AmO at 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15% concentrations evoked protective effect on decreased viability of fibroblasts exposure to UVA irradiation [

13]. These data led us to evaluate the effect of AmO on collagen metabolism in fibroblasts exposed to UVA radiation.

Collagen is the main structural protein of connective tissue, providing the skin with proper tension, elasticity, and flexibility. Excessive exposure to the sun, extreme temperatures, and certain compounds in cosmetics can affect the structure of collagen fibers, resulting in worsened skin condition [

15]. Collagen biosynthesis was evaluated by measurement of L-5-[

3H]-proline incorporation into collagen proteins. The results were expressed as dpm of L-5-[

3H]-proline released from collagenase-sensitive proteins per milligram of total protein in the homogenate extract, and expressed as a percentage of the control value (100%) (

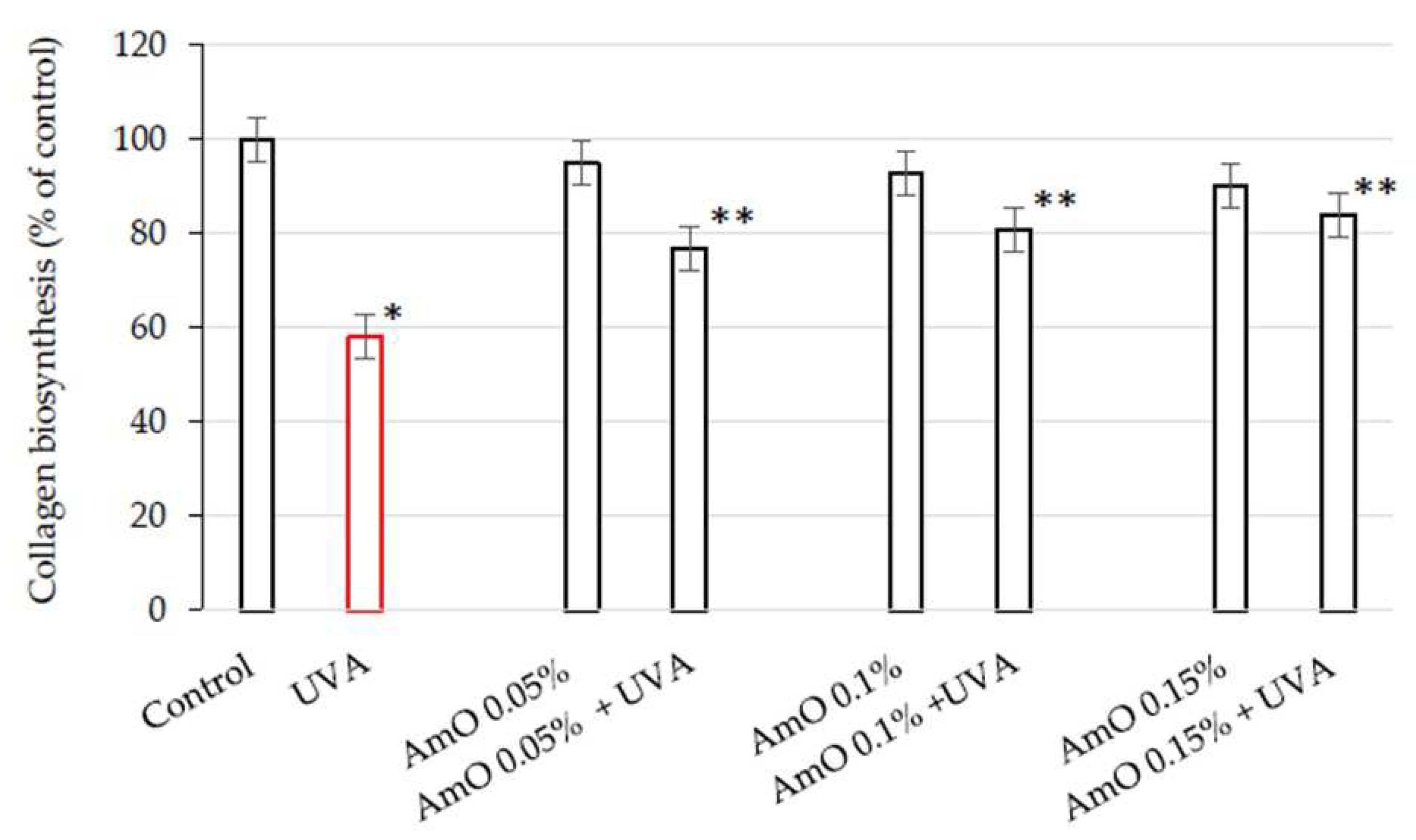

Figure 1).

We have found that AmO at studied concentrations slightly inhibited collagen biosynthesis in fibroblasts, however, the inhibition was statistically insignificant. When the cells were exposed to UVA radiation, collagen biosynthesis was decreased to 58% of the control value (statistically significant at p < 0.05). AmO at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1% and 0.15% partially counteracted UVA-dependent inhibition of collagen biosynthesis to about 78%, 81%, and 85% of the control value, respectively. This data suggest that AmO has a protective effect on collagen biosynthesis in human skin fibroblasts exposed to UVA radiation.

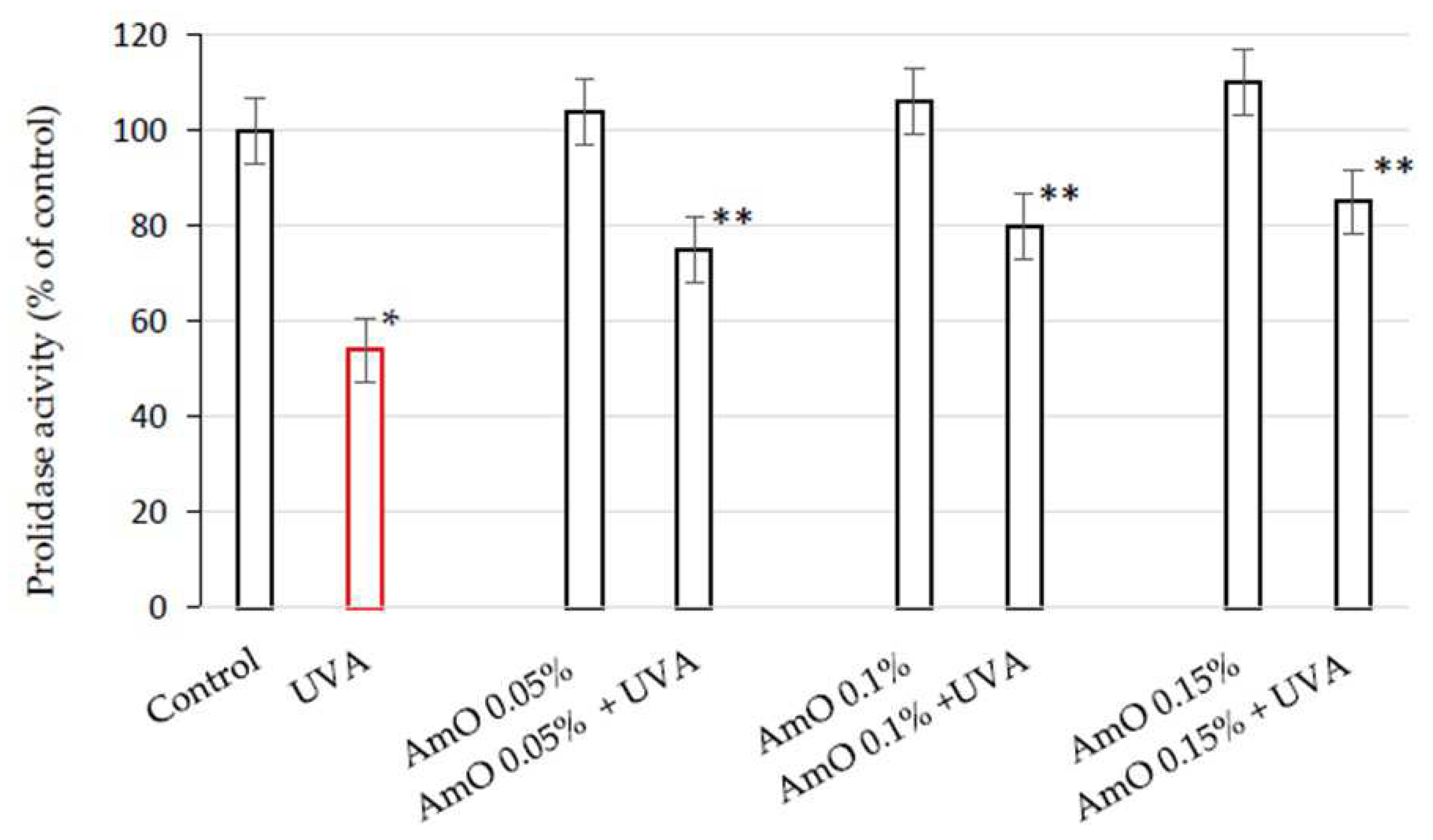

Collagen content in the tissues depends on the balance between collagen biosynthesis and degradation. An important regulator of collagen turnover is prolidase, cytoplasmic enzyme catalyzing the final stage of collagen degradation. It cleaves di- and tri-peptides containing C-terminal proline. Released proline is reused for collagen biosynthesis and cell growth [

16]. Therefore, we decided to study the prolidase activity in human skin fibroblasts exposed to UVA radiation and treated with AmO. We assessed this activity using a colorimetric method, based on the measurement of proline released from the substrate (Gly-Pro), using the Chinard's reagent. AmO did not affect significantly prolidase activity in the studied cells. In UVA-terated cells prolidase activity was decreased to 54% of the control value. AmO at concentrations 0.05%, 0.1% and 0.15% partially counteracted UVA-dependent inhibition of prolidase activity to about 75%, 80%, and 85% of the control value, respectively (

Figure 2). These data shows the protective effect of the AmO on UVA-induced impairment of collagen biosynthesis and prolidase activity in fibroblasts.

Collagen plays a significant role in cellular metabolism as a ligand of integrin receptors containing β1 subunit. The β1-integrin receptor is involved in signaling pathways that regulate collagen biosynthesis and prolidase activity. Interactions between collagen and these receptors activate intracellular signaling pathways, contributing to the regulation of various cellular metabolic functions [

4].

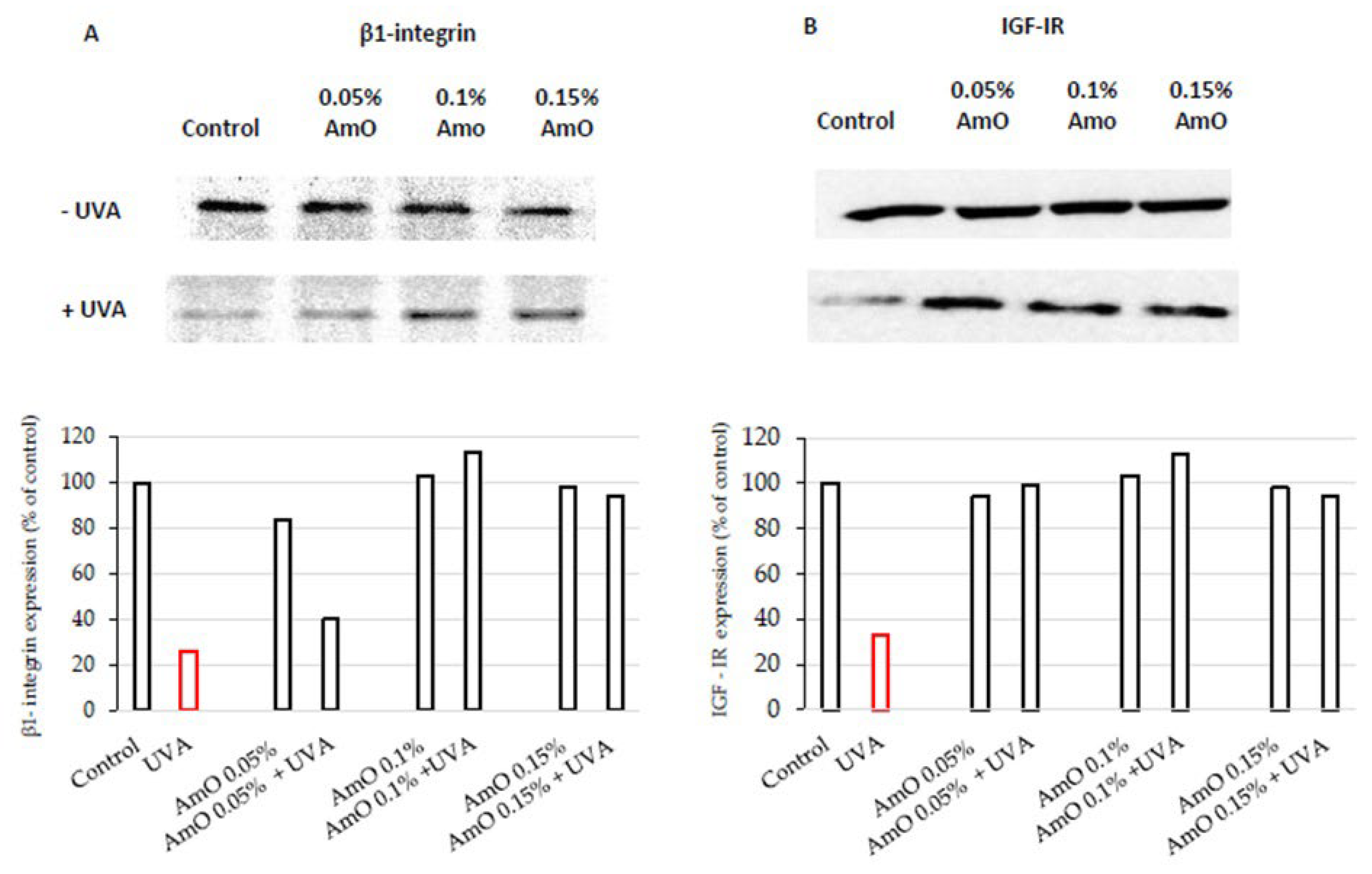

AmO at 0.05% and 0.1% concentrations did not affect the expression of β1-integrin receptor as presented in

Figure 3A. Slight decrease in the expression of this receptor was found at 0.15% of AmO. In UVA-treated cells the expression of this receptor was drastically decreased, while the application of AmO counteracted this process in a dose-dependent manner. Regarding the results of collagen biosynthesis and prolidase activity, there is another level of correlation between these processes and β1-integrin receptor expression in UVA and AmO treated cells. It suggests that UVA radiation, by decreasing the expression of the β1-integrin receptor, down-regulate prolidase activity, leading to reduced collagen production. The protective effect of AmO on the the UVA-induced down-regulation of β1-integrin expression may represent a molecular mechanism for protection of collagen biosyntheis against deleterious effect of UV radiation on this process.

Prolidase activity and collagen biosynthesis are regulated also by insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR) signaling. IGF-I belongs to a peptide growth factors that play a significant role in cell metabolism, proliferation, differentiation and it is the most potent stimulator of collagen biosynthesis [

6]. The expression of IGF-I is elevated in skin cells under inflammatory conditions. For instance, in psoriatic skin, fibroblasts evoke high expression of IGF-I [

17].

To date, the effect of UVA on IGF-IR expression in cells of normal skin is not well recognized. The study presented in this report shows that fibroblasts exposed to UVA radiation evoke decreased IGF-IR receptor expression, suggesting the mechanism for UVA-induced inhibition of collagen biosynthesis. The application of AmO at tested concentrations counteracted the deleterious effect of UVA on IGF-IR expression (

Figure 3B). These findings suggest that down regulation of IGF-IR signaling may play important role in the mechanism of UVA-induced inhibition of collagen biosynthesis. They also suggest the mechanism for protective action of AmO on this process.

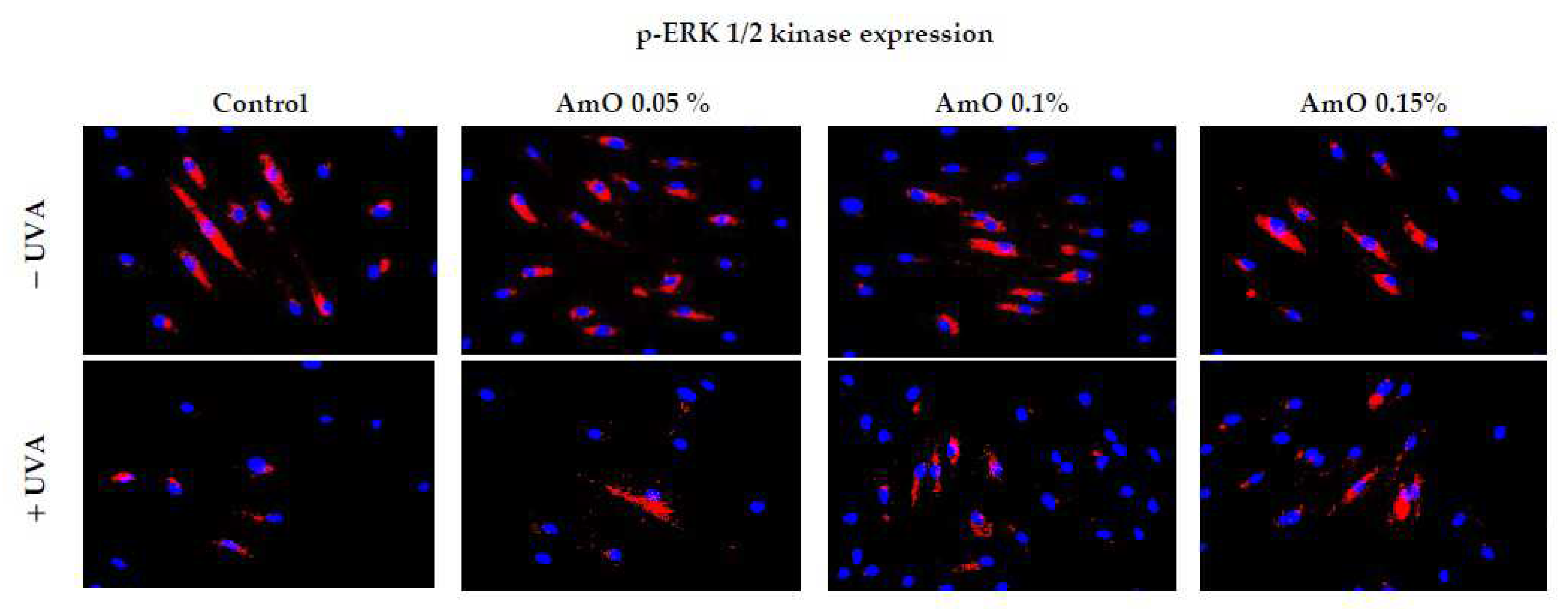

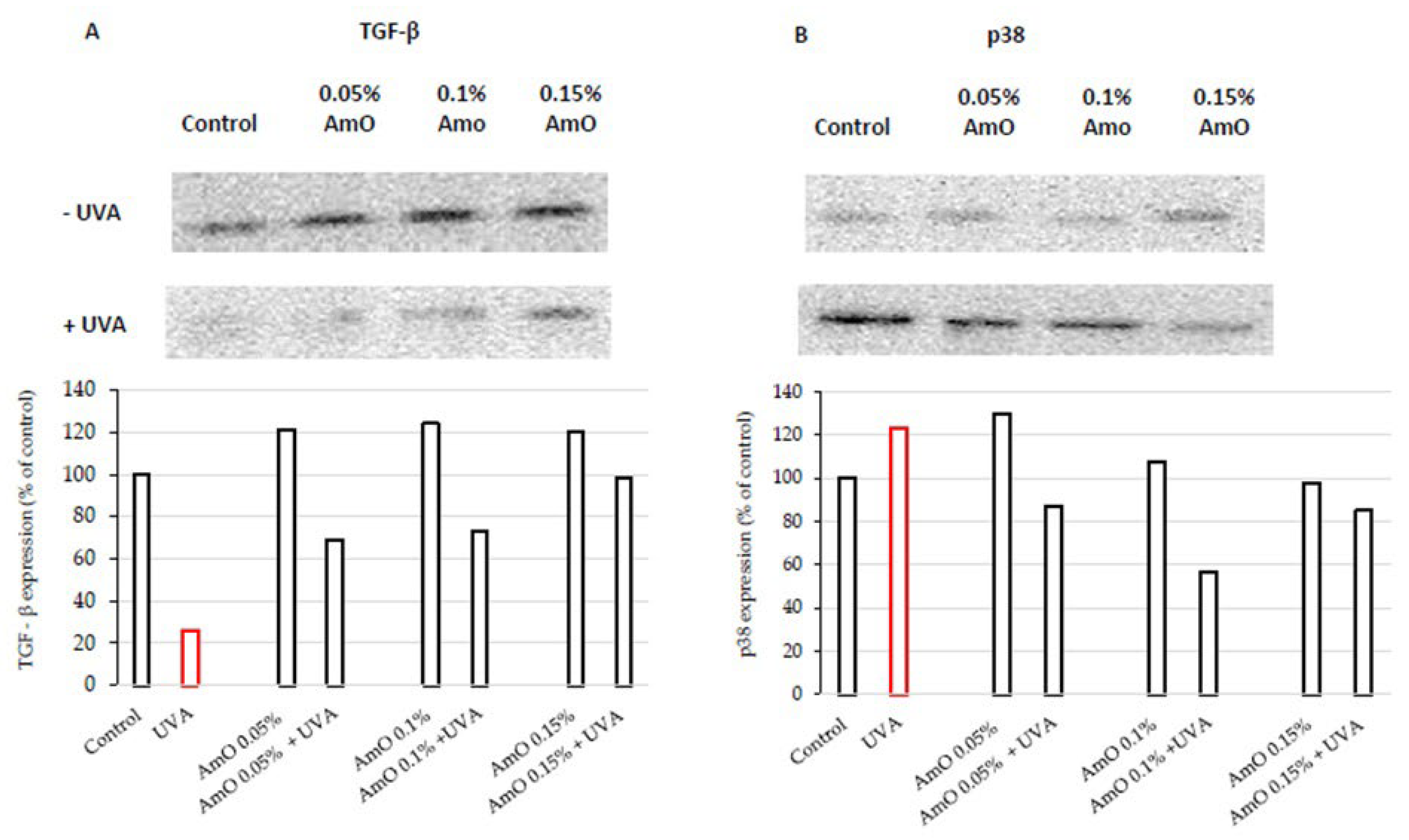

We have confirmed the potential involvement of the β1-integrin and IGF-I receptors in the molecular mechanism by which UVA affects collagen biosynthesis and prolidase activity. It is well established that stimulation of these receptors lead to the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) [

8,

9]. MAPK signaling pathways play a important role in cellular metabolism. For instance in skin cells ROS induce decrease in the expression of phosphorylated forms of ERK 1/2 kinase (p-ERK 1/2) and increase in the expression of stress-activated kinase p38, leading to the up-regulation of expression of transcription factors, including c-Jun and c-Fos, which form the activator protein-1 (AP-1) complex [

7,

8,

9]. This protein is a key regulator in various skin processes, including photoaging, by affecting the TGF-β signaling pathway and inhibiting the expression of type I procollagen gene. In our previous studies, we demonstrated that UVA radiation induced an increase of ROS generation in fibroblasts [

13]. In present studies we show that UVA induced a decrease in the expression of p-ERK 1/2 (

Figure 4) and TGF-β (

Figure 5A) and an increase in p38 protein expression (

Figure 5B). This confirms the hypothesis on the correlation between UVA-induced ROS generation, deregulation of MAPK-dependent signaling pathways and collagen biosynthesis in fibroblasts. From several other studies, it is evident that the application of antioxidants from natural sources (e.g., green tea, pomegranate extract), reverses the negative effects (deregulation of the above-described cellular signaling pathways) of oxidative stress, including that induced by UVA [

18,

19]. Our research supports the data, showing that AmO, in a dose-dependent manner, restored the UVA-induced decrease in the expression of p-ERK 1/2 (

Figure 4) and TGF-β (

Figure 5A), and restored to the control value UVA-induced increase in the expression of p38 kinase (

Figure 5B). This confirms the protective effect of AmO on the deleterious impact of UVA on the investigated cellular signaling pathways.

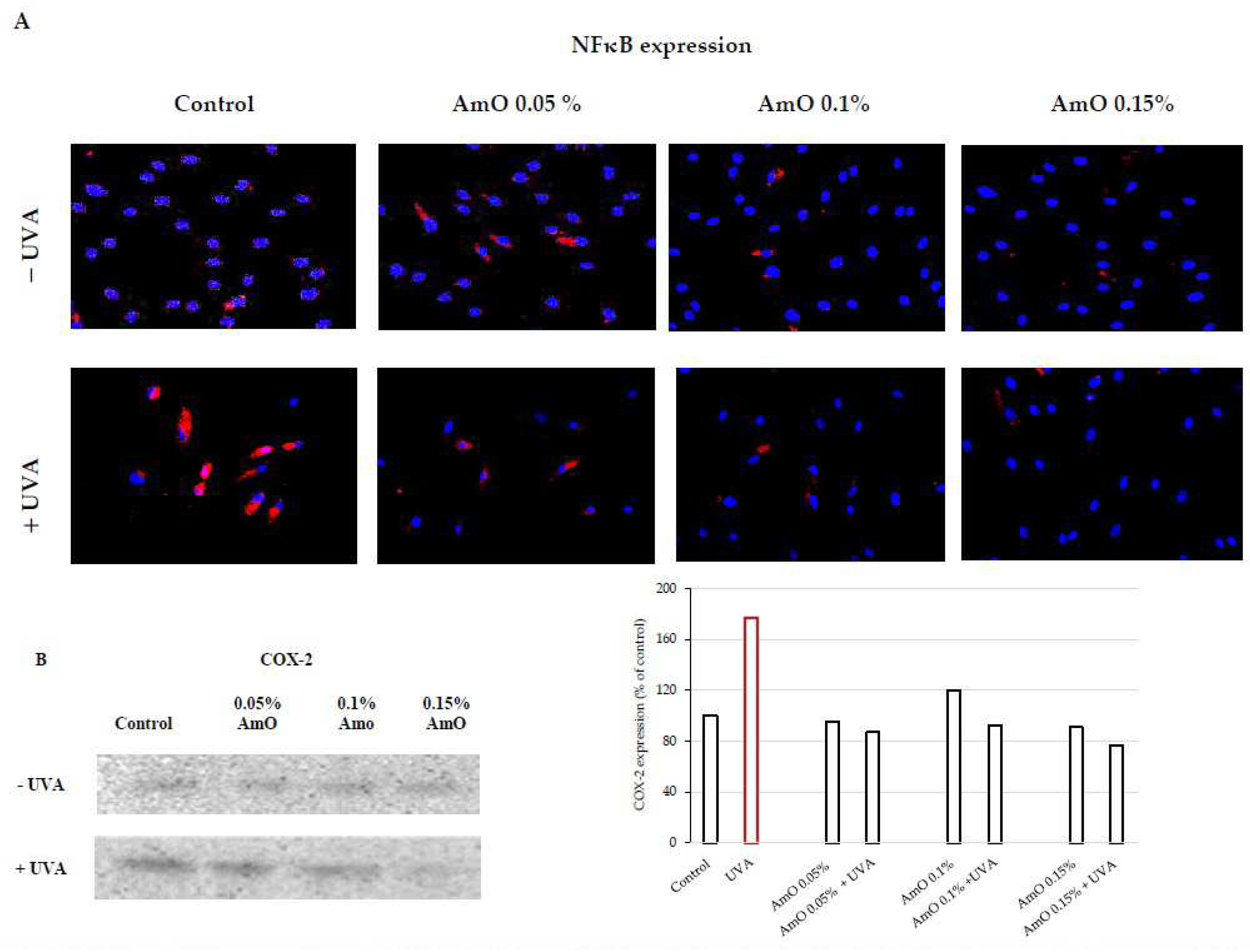

UVA-induced skin damage is preceded by tissue inflammation. Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) has been described as one of the pro-inflammatory factors activated by UV radiation. It serves as a mediator of cellular responses to inflammatory stimuli, pathogens, and cellular stressors. In the cytoplasm of cells, NF-κB is present in an inactive form bound to the inhibitory protein IκB. It is known that NF-κB activation is induced by inflammatory stimuli, and subsequently, NF-κB translocate to the cell nucleus [

20]. Activated NF-κB plays a crucial role in regulating the expression of various genes involved in immune and inflammatory responses, including the expression of cyclooxygenase COX-2, an enzyme participating in the inflammatory process. UVA radiation activates COX-2, which induces inflammatory process. Vostálová et al. [

12] observed an increase in the expression of COX-2 in the skin of mice exposed to a dose of 20 J/cm

2 of UVA. In our experiments, we demonstrated that UVA irradiation of fibroblasts at a dose of 10 J/cm

2 significantly increased the expression of NF-κB and its translocation to the cell nucleus (

Figure 6A), along with increased COX-2 expression (

Figure 6B). This confirms the pro-inflammatory mechanism of UVA in the studied cellular model. AmO by itself did not induce changes in the expression and translocation of NF-kB to the nucleus, however, in cells exposed to the UV radiation significantly inhibited the expression of this factor. These experiments show that UVA-induced increase in the expression of COX-2 associated with the translocation of NF-kB into the nucleus of human skin fibroblasts is counteracted by AmO (

Figure 6A,B). This shows protective action of AmO against UVA-induced inflammation in fibroblasts and suggests that AmO preparation may be useful as a potential therapeutic agent.

Disruption of skin integrity by external factors (e.g., UV radiation) activate reparative processes. Fibroblasts play a crucial role in skin wound healing, from the early inflammatory phase to the final production of extracellular matrix components. Contemporary research is exploring substances, including natural compounds, that can impact tissue regeneration. Plant oils have shown promising results in both in vitro and in vivo studies. They influence various phases of the wound healing process through their antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties, as well as by promoting cell proliferation, enhancing collagen synthesis, stimulating skin regeneration, and repairing the skin's lipid barrier function. It has been demonstrated that the fatty acids present in these oils also play a significant role in the wound healing process. Linolenic, linoleic, and oleic acids serve as precursors for the synthesis of inflammatory or anti-inflammatory mediators and are integral components of cell membrane phospholipids, ceramides, and sebum, all of which are vital constituents of the lipid barrier [

21].

Plant-based oils are mixtures of glyceryl esters and higher fatty acids, and they also contain phytosterols, vitamin E and its derivatives, and squalene. It has been demonstrated that triglycerides, free fatty acids, glycerol, and nonsaponifiable compounds directly or indirectly influence the wound healing process. The biological effect of plant oils in wound healing is mainly attributed to their similarity to skin lipids. Numerous studies confirm that various natural oils, under different conditions, exhibit more or less effective actions in the wound healing process. For example, in vitro studies have shown that cold-pressed rapeseed oil stimulates fibroblast proliferation and promotes fibroblast migration to the wound area, indicating its wound-healing effects. Similar effects were observed with flaxseed oil [

21]. Additionally, plant oils like borage oil, evening primrose oil, and avocado oil, containing gamma-linolenic acid (GLA), are beneficial for skin conditions, inflammation, and irritations. Borage oil, with its high GLA content, stimulates skin cell activity and regeneration, making it useful in treating skin conditions such as allergies and inflammations. Evening primrose oil also supports skin regeneration, eases skin issues, and reduces inflammation, making it a good choice for those with conditions like psoriasis. Avocado oil, rich in vitamin E, β-carotene, vitamin D, protein, lecithin, and fatty acids, offers substantial benefits when added to formulations [

22]. In respect to AmO there is a lack of studies on its role in skin repair processes, so it was essential to conduct this study.

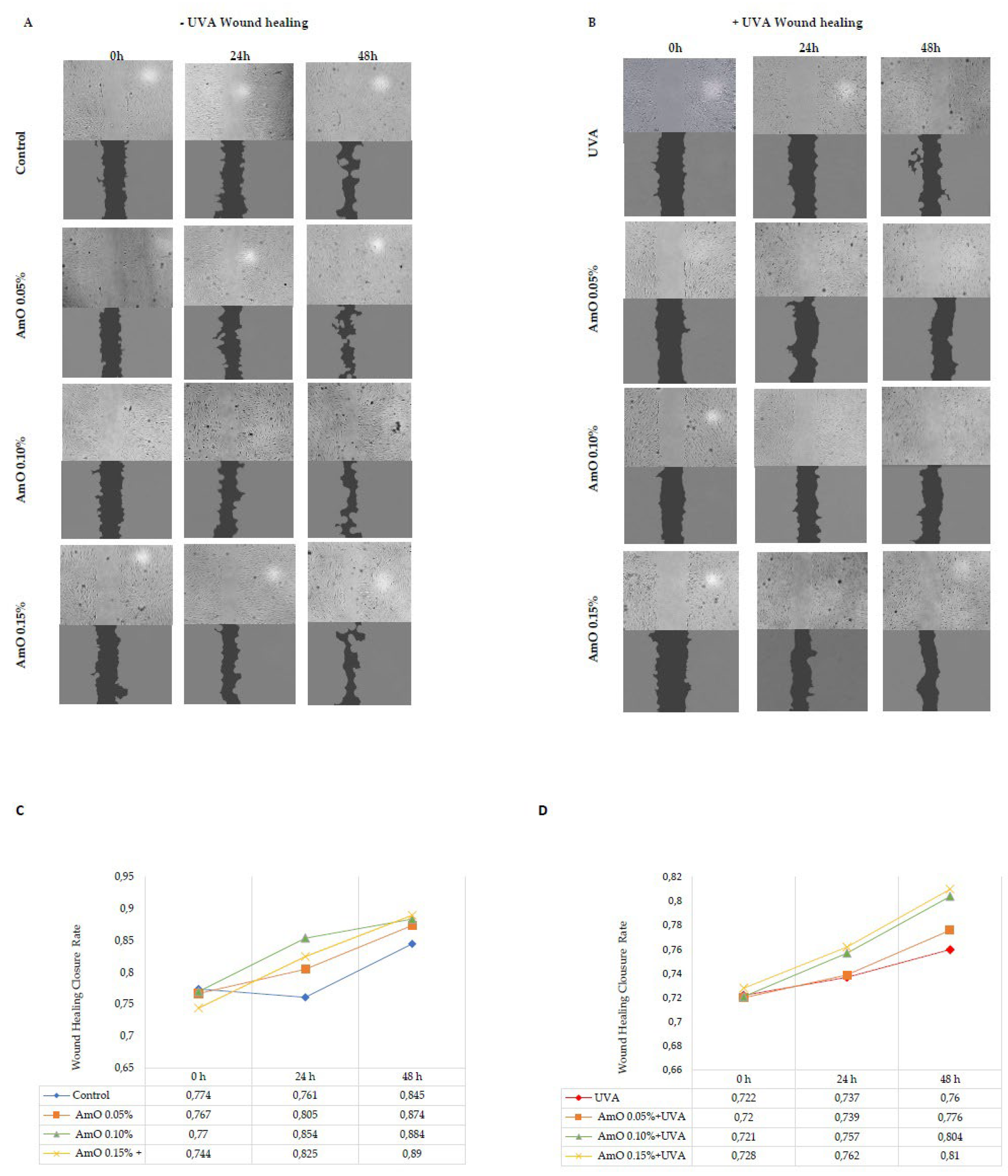

The results of wound closure are presented in images obtained from a fluorescence microscope and subjected to analysis using ImageJ

® software with the Wound Healing Size Tool extension (

Figure 7A,B). The wound healing closure rate was calculated and presented on a chart and in digital form (

Figure 7C,D). The obtained results show that AmO stimulated fibroblast proliferation and promoted their migration in a model of wound healing under control conditions (without exposure to UVA radiation). All studied concentrations of AmO, (0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.15%) positively influenced the wound healing process in a time and dose dependent manner. Interestingly, the ability of AmO to stimulate fibroblast proliferation and migration was also enhanced after exposure to UVA, although less intensely than in non-UVA-irradiated cells. The effectiveness of AmO in the wound healing process may be attributed to the presence of components such as linoleic acid, squalene, derivatives of vitamin E, and phytosterols. These components not only scavenge free radicals, as demonstrated in our previous study [

13], but also have a beneficial impact on the wound healing processes, as presented in this report.

It is known that migration, adhesion, proliferation, neovascularization, remodeling, and apoptosis are the key processes in wound healing, affected by ROS. An increased production of ROS can disrupt these processes [

23]. Studies by Wlaschek and Scharffetter-Kochanek [

24] have shown that changes in mitochondrial DNA induced by UV radiation can increase intracellular ROS levels in fibroblasts, leading to alterations in their migration and proliferation. In vitro wound healing tests have demonstrated a significantly reduced ability of fibroblasts to close the wound gap, suggesting that an excess of ROS in mitochondria negatively affects the wound healing process. This explains how the overlapping processes, resulting in increased ROS production due to cell damage in fibroblast exposed to UVA radiation limit the regenerative capacity of the compound studied in our study, in the wound healing process [

24].

It has been demonstrated that therapies involving the application of plant-derived butters or oils are efficacious with limited adverse effects, rendering phytotherapy a compelling alternative for dermatological treatments. Fatty acids are recognized to play a significant role in the described wound healing processes, whereas non-saponifiable compounds can substantially contribute to antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects [

14]. Therefore, it is advisable, based on our research findings, to consider the use of unrefined plant-derived oils, including AmO in cosmetics, with a protective effect against solar radiation. Therefore, results of this study provide rational for applications of AmO in therapeutics of protective activity against UVA-induced skin damage