Submitted:

08 December 2023

Posted:

13 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

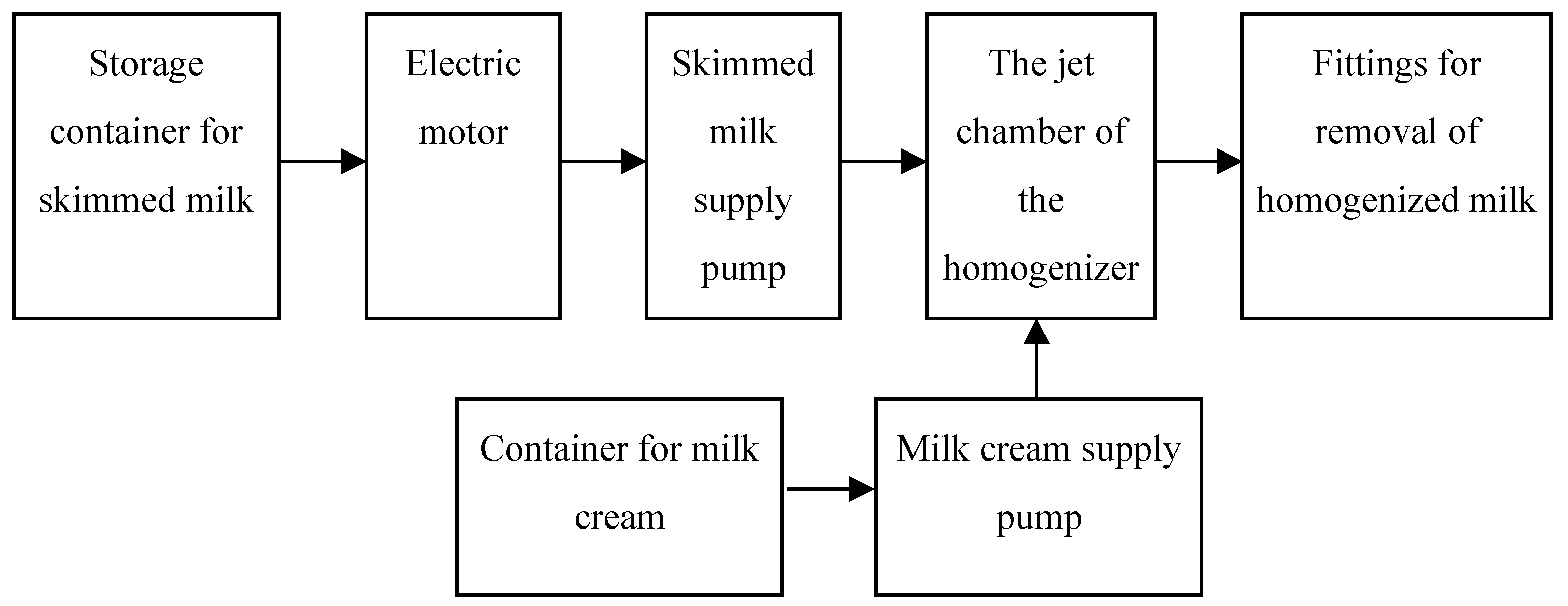

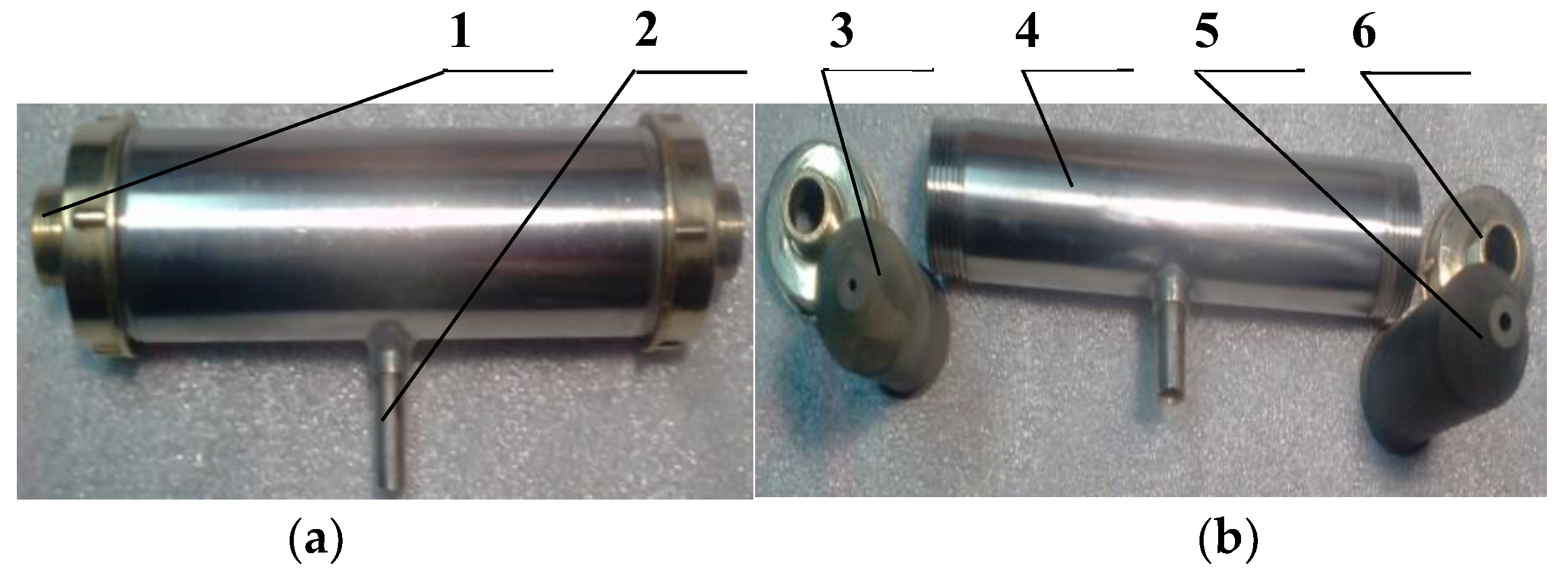

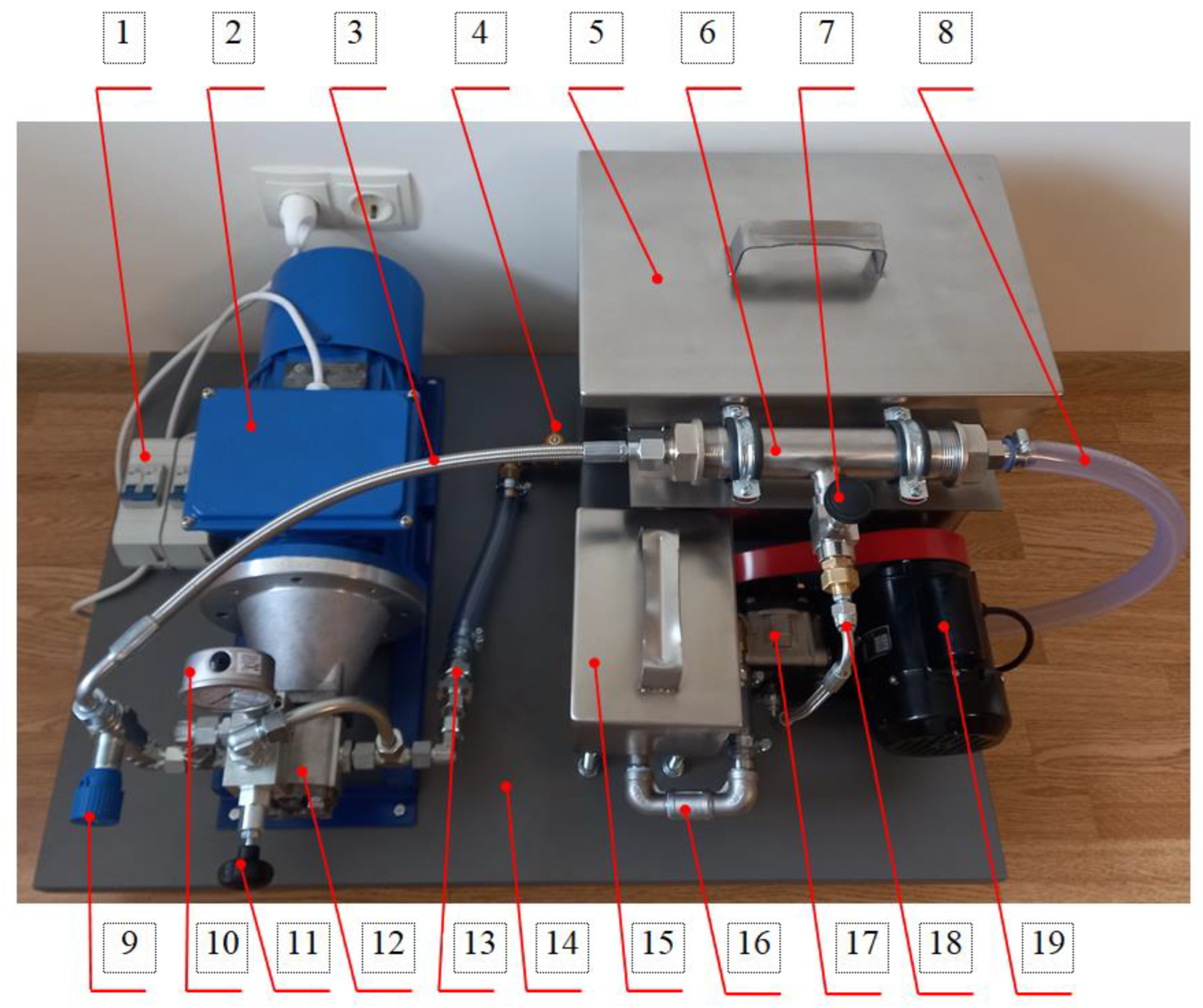

2.1. Scheme of the experimental sample and the structure of the chamber of the homogenization unit of the jet-slit homogenizer

2.2. Methods of experimental research

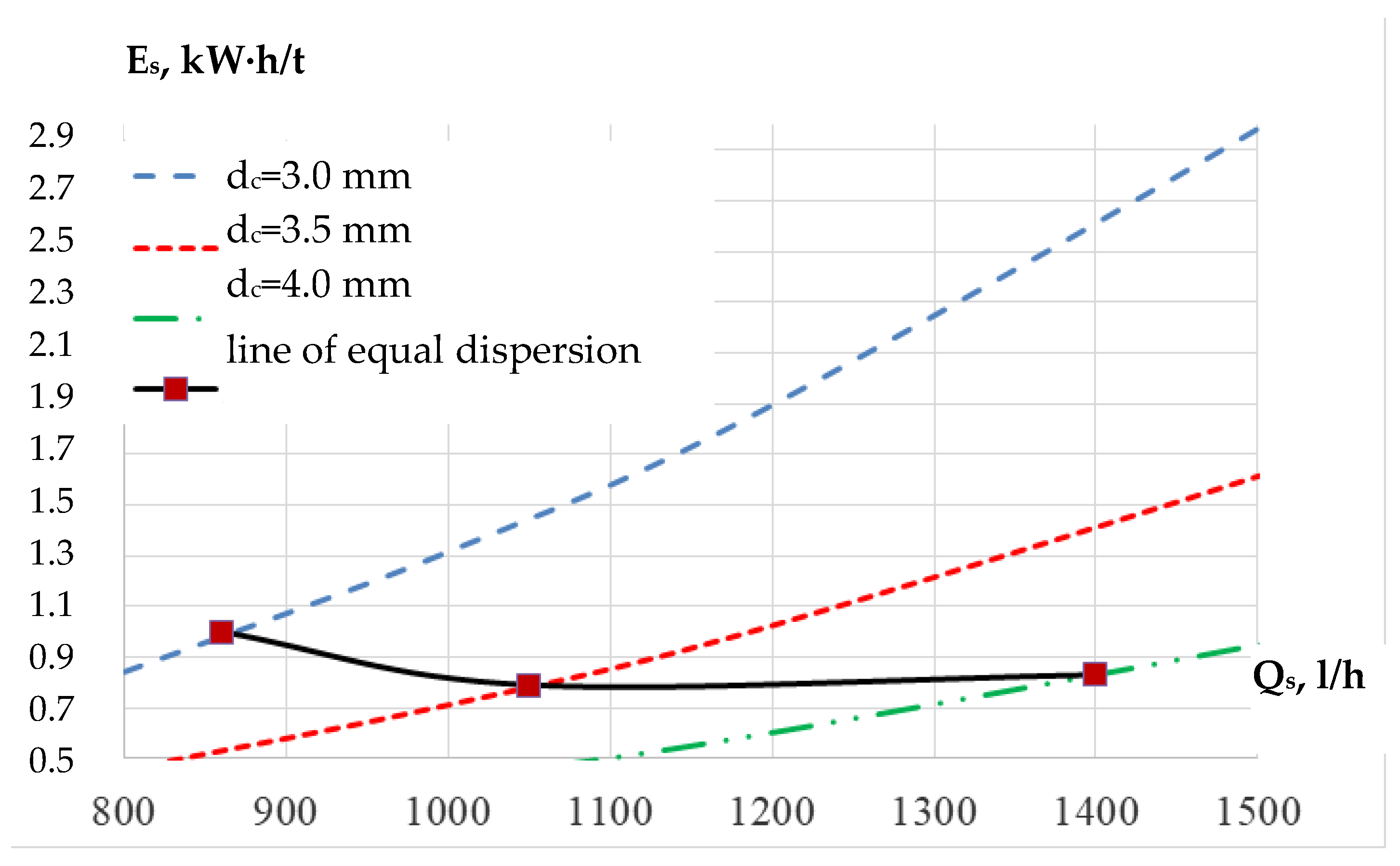

2.3. Methodology for optimizing the parameters of a jet-slit milk homogenizer

3. Results

3.1. Results of analytical studies

3.2. Results of experimental studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Green Deal, EU, 2019. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Delivering the European Green Deal, EU, 2019. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/delivering-european-green-deal_en (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Labenko, O.; Sobchenko, T.; Hutsol, T.; Cupiał, M.; Mudryk, K.; Kocira, A.; Pavlenko-Didur, K.; Klymenko, O.; Neuberger, P. Project Environment and Outlook within the Scope of Technologically Integrated European Green Deal in EU and Ukraine. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialkova, E.A. Gomogenizatsiya. Novyj Vzglyad; Monografiya-spravochnik. SPb.; GIORD: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2006; p. 392. [Google Scholar]

- Dhankhar, P. Homogenization fundamentals. IOSR J. Eng. 2014, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innings, F.; Trägårdh, C. Visualization of the drop deformation and break-up process in a high pressure homogenizer. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2005, 28, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppertz, T. Homogenization of Milk Other Types of homogenizer (High-Speed Mixing, Ultrasonics, Microfluidizers, Membrane Emulsification). In Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 761–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartar, L. The General Theory of Homogenization; Lecture Notes. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; p. 470. [Google Scholar]

- Samoichuk, K.; Zahorko, N.; Oleksiienko, V.; Petrychenko, S. Generalization of Factors of Milk Homogenization. In Modern Development Paths of Agricultural Production; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciron, C.; Gee, V.; Kelly, A.; Auty, M. Comparison of the effects of high-pressure microfluidization and conventional homogenization of milk on particle size, water retention and texture of non-fat and low-fat yoghurts. Int. Dairy J. 2010, 20, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoichuk, K.; Kovalyov, A.; Oleksiienko, V.; Palianychka, N.; Dmytrevskyi, D.; Chervonyi, V.; Horielkov, D.; Zolotukhina, I.; Slashcheva, A. Determining the quality of milk fat dispersion in a jet-slot milk homogenizer. East. Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2020, 5, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson, A.; Fuchs, L.; Innings, F.; Revstedt, J.; Trägårdh, C.; Bergenståhl, B. Velocity measurements of turbulent two-phase flow in a high-pressure homogenizer model. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2013, 200, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbil, H. Evaporation of pure liquid sessile and spherical suspended drops: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. Elsevier B.V. 2012, 170, 6786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capretto, L.; Cheng, W.; Hill, M.; Zhang, X. Micromixing within Microfluidic Devices. Top Curr Chem 2011, 304, 27–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vladisavljevic, G.; Al Nuumani, R.; Nabavi, S. Microfluidic production of multiple emulsions. Micromachines 2017, 8, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, A.; Islam, M.; Hasan, N. The Effect of pH and High-Pressure Homogenization on Droplet Size. Sigma J. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2017, 35, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, K.; Fan, Z. H. Mixing in Microfluidic Devices and Enhancement Methods. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2015, 25, 94001–94017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Li, L.; Ge, X.; Zhang, S.; Qiu, T. Scale-up of microreactor: Effects of hydrodynamic diameter on liquid–liquid flow and mass transfer. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 226, 115838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Flores, D.; Hernández-Herrero, M.; Guamis, B.; Ferragut, V. Comparing the Effects of Ultra-High-Pressure Homogenization and Conventional Thermal Treatments on the Microbiological, Phys, and Chem Quality of Almond Beverages. J. Food Sci. 2013, 78, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Chang, C.; Wang, Y.; Fu, L. Microfluidic Mixing: A Review. Ijms 2011, 12, 3263–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, G.; Xue, L.; Zhang, H.; Lin, J. A Review on Micromixers. Micromachines 2017, 8, 274–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharyaa, S.; Mishrab, V.; Patelc, J. Enhancing the mixing process of two miscible fluids: A review. AIP Conference Proceedings 2021, 2341, 030025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minakov, A.; Rudyak, V.; Gavrilov, A.; Dekterev, A. Smeshenie v mikromiksere T—Tipa pri umerennykh chislakh Rejnol'dsa. Teplofiz. I Ajeromekhanika 2012, 19, 577–587. [Google Scholar]

- Fonte, C.; Fletcher, D.; Guichardon, P.; Aubin, J. Simulation of micromixing in a T-mixer under laminar flow conditions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 222, 115706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Wu, Z.; Sattari Najafabadi, M.; Sunden, B. Liquid-Liquid Flow Patterns in Microchannels. In Proceedings of the ASME 2017 Heat Transfer Summer Conference, Bellevue, Washington, DC, USA; 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Roudgar, M.; Brunazzi, E.; Galletti, C.; Mauri, R. Numerical study of split T-micromixers. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2012, 35, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marzo, L.; Cree, P.; Barbano, D. Prediction of fat globule particle size in homogenized milk using Fourier transform mid-infrared spectra. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 8549–8560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Ameel, T.; Guilkey, J. Mixing kinematics of moderate Reynolds number flows in a T-channel. Phys. Fluids 2010, 22, 031601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagodnitsyna, A.; Kovalev, A.; Bilsky, A. Flow patterns of immiscible liquid-liquid flow in a rectangular microchannel with T-junction. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 303, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, H.; Kawaji, M. Viscous oil-water flows in a microchannel initially saturated with oil: Flow patterns and pressure drop characteristics. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2011, 37, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, S.; Kockmann, N.; Woias, P. Characterization of Laminar Transient Flow Regimes and Mixing in T-shaped Micromixers. Heat Transf. Eng. 2009, 30, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobasov, A.; Minakov, A.; Rudyak, V. Izuchenie rezhimov smesheniya zhidkosti i nanozhidkosti v T-obraznom mikromiksere. Inzhenerno Fiz. Zhurnal 2018, 91, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Camarri, S. T-shaped micromixers aligned in a row: Characterization of the engulfment regime. Eng. Acta Mechanica 2022, 233, 1987–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darekar, M.; Singh, K.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Shenoy, K. Liquid-Liquid Two-Phase Flow Patterns in Y-Junction Microchannels. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 12215–12226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fani, A.; Camarri, S.; Salvetti, M. Investigation of the steady engulfment regime in a three-dimensional T-mixer. Phys. Fluids 2013, 25, 64–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobasov, A.; Minakov, A. Analyzing mixing quality in a T-shaped micromixer for different fluids properties through numerical simulation. Chemical Eng. Process. 2018, 124, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermakov, S.; Hutsol, T.; Glowacki, S.; Hulevskyi, V.; Pylypenko, V. Primary Assessment of the Degree of Torrefaction of Biomass Agricultural Crops. Environment. Technology: Rezekne, Latvia, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussong, J.; Lindken, R.; Pourquie, M.; Westerweel, J. Numerical study on the flow physics of a T-shaped micro mixer. In Proceedings of the IUTAM Symposium on Advances in Micro- and Nanofluidics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haponiuk, E.; Zander, L.; Probola, G. Effect of the homogenization process on the rheological properties of food emulsions. Pol. J. Nat. Sci. 2015, 30, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Dejnychenko, G.; Samojchuk, K.; Kovalyov, O. KonstruktsiJi strumynnykh dyspergatoriv zhyrovoJi fazy moloka. Pr. TDATU 2016, 16, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, M.; Dejmek, P. Engineering Aspects of Emulsification and Homogenization; CRC Press; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2015; p. 331. ISBN 9781466580435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.; Watts, A.; McConville, J. Mechanical particle-size reduction techniques. AAPS Adv. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 22, 165–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Lucas, D. A literature review of theoretical models for drop and bubble breakup in turbulent dispersions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2009, 64, 3389–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, H.; Truong, T.; Bansal, N.; Bhandari, B. The Effect of Manipulating Fat Globule Size on the Stability and Rheological Properties of Dairy Creams. Food Biophys. 2017, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, V.; Ghasemi-Varnamkhasti, M.; Ebrahimi, R.; Abbasvali, M. Ultrasonic techniques for the milk production industry. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. MSRMD 2014, 58, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deynichenko, G.; Samoichuk, K.; Yudina, T.; Levchenko, L.; Palianychka, N.; Verkholantseva, V.; Dmytrevskyi, D.; Chervonyi, V. Parameter optimization of milk pulsation homogenizer. Journal of Hygienic Engineering and Design 2018, 24, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Havrylenko, Y.; Kholodniak, Y.; Halko, S.; Vershkov, O.; Miroshnyk, O.; Suprun, O.; Dereza, O.; Shchur, T.; Śrutek, M. Representation of a monotone curve by a contour with regular change in curvature. Entropy 2021, 23, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoichuk, K.; Kovalyov, A.; Oleksiienko, V.; Palianychka, N.; Dmytrevskyi, D.; Chervonyi, V.; Horielkov, D.; Zolotukhina, I.; Slashcheva, A. Elaboration of the research method for milk dispersion in the jet slot type homogenizer. EUREKA Life Sci. 2020, 5, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9622:2013; Milk and Liquid Milk Products. ISO Standards: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- ISO 707:2013; Milk and milk products. Guidance on Sampling. ISO Standards: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Jiang, B.; Shi, Y.; Lin, G.; Kong, D.; Du, J. Nanoemulsion prepared by homogenizer: The CFD model research. J. Food Eng. 2019, 241, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovs, S.; Bulgakov, V.; Kaletnik, H.; Shymko, L.; Kuvachov, V.; Ihnatiev, Y. Experimental checking of mathematical models describing the functioning adequacy of bridge systems in agricultural track system. INMATEH-Agricultural Engineering. 2020, 62, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossett, D.; Weaver, W.; Mach, A.; Hur, S.; Tse, H.; Lee, W.; Amini, H.; Carlo, D. Label-free cell separation and sorting in microfluidic systems. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 397, 3249–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulgakov, V.; Kuvachov, V.; Olt, J. Theoretical study on power performance of agricultural gantry systems. Ann. DAAAM Proc. Int. DAAAM Symp. 2019, 30, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulevskyi, V.; Stopin, Y.; Postol, Y.; Dudina, M. Experimental Study of Positive Influence on Growth of Seeds of Electric Field a High Voltage. In Modern Development Paths of Agricultural Production. Trends and Innovations; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samojchuk, K.; Kovalyov, O.; Palyanichka, N.; Kolodij, O.; Lebid', M. Eksperimental'ni doslidzhennya parametriv struminnogo gomogenizatora moloka z rozdil'noyu podacheyu vershkiv shchil'ovogo tipu. Pr. TDATU 2019, 19, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postelmans, A.; Aernouts, B.; Jordens, J.; Van Gerven, T.; Saeys, W. Milk homogenization monitoring: Fat globule size estimation from scattering spectra of milk. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 60, 102311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoichuk, K.; Kovalyov, A.; Fuchadzhy, N.; Hutsol, T.; Jurczyk, M.; Pająk, T.; Banaś, M.; Bezaltychna, O.; Shevtsova, A. Energy Costs Reduction for Dispersion Using a Jet-Slot Type Milk homogenizer. Energies 2023, 16, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoichuk, K.; Zhuravel, D.; Viunyk, O.; Milko, D.; Bondar, A.; Sukhenko, Y.; Sukhenko, V.; Adamchuk, L.; Denisenko, S. Research on milk homogenization in the stream homogenizer with separate cream feeding. Potravinarstvo Slovak Journal of Food Sciences 2020, 14, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulgakov, V.; Pascuzzi, S.; Adamchuk, V.; Kuvachov, V.; Nozdrovicky, L. Theoretical study of transverse offsets of wide span tractor working implements and their influence on damage to row crops. Agriculture 2019, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanga, B.; Zhua, Z.; Gaoa, M.; Yana, X.; Zhua, X.; Guo, W. A portable detector on main compositions of raw and homogenized milk. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 177, 105668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Kim, K.; Kim, S. Numerical study of the effect on mixing of the position of fluidstream interfaces in a rectangular microchannel. Int. J. Microsystem Technologies 2010, 16, 1757–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faichuk, O.; Voliak, L.; Pantsyr, Y.; Slobodian, S.; Szeląg-Sikora, A.; Gródek-Szostak, Z. European Green Deal: Threats Assessment for Agri-Food Exporting Countries to the EU. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graskemper, V.; Yu, X.; Feil, J.-H. Farmer typology and implications for policy design – An unsupervised machine learning approach. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchenko, A.; Voloshina, A.; Panchenko, I.; Titova, O.; Caldare, A. Design of Hydraulic Mechatronic Systems with Specified Output Characteristics. Advances in Design, Simulation and Manufacturing III. DSMIE 2020. Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodziak, A.; Wajs, J.; Zuba-Ciszewska, M.; Stobiecka, M.; Janczuk, A. Organic versus conventional raw cow milk as material for processing. Animals 2021, 11, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voloshina, A.; Panchenko, A.; Panchenko, I.; Zasiadko, A. Geometrical parameters for distribution systems of hydraulic machines. In Modern Development Paths of Agricultural Production; Nadykto, V., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of homogenizer | Average diameter of fat droplets after homogenization, μm | Average value of SEC, kWh/t |

|---|---|---|

| Valve | 0.78 | 7.20 |

| Microfluidizer | 0.10 | 10.00 |

| Cavitation | 1.10 | 1.20 |

| Mini-mixers | 1.20 | 1.50 |

| Opposite-flow jet | 0.80 | 1.70 |

| Impact-jet | 0.82 | 1.50 |

| Jet homogenizer with counter feed of cream | 0.77 | 1.40 |

| Jet homogenizer with separate supply of cream | 0.85 | 0.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).