1. Introduction

Recommendation mechanisms have emerged as vital tools for filtering information in various aspects of life. They are widely used in commercial platforms, including e-commerce sites like Amazon. Our preferences and purchases change over time. To ensure recommended results align more closely with actual needs, the Sequential Recommendation System (SRS) has gained prominence [

1]. SRS emphasizes continuous interaction records with time-series characteristics, based on the assumption that dependencies exist between interactions. Therefore, all user interaction records are essential for a comprehensive understanding. Traditionally, research in this area often used the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) as the network architecture, yielding positive results [

2,

3,

4].

The sequential recommendation method utilizes a series of interaction records as its reference basis. To avoid learning incorrect information from irrelevant interaction records, the concept of a session has been introduced. Interaction records within a defined period are considered part of the same session, with interactions processed separately based on the session. This led to the development of both session-based and session-aware recommendations.

The Session-Based Recommender System (SBRS) [

2,

5,

6] aims to reflect users' actual thinking and behavior patterns. It considers only the interaction records within a short period, meaning recommendations are based solely on one session's data. This approach's limitation is its reliance on a narrow data range, leading to less personalized recommendations. It is, however, beneficial for users seeking recommendation system convenience without needing to register or log in.

To facilitate personalized recommendations, the Session-Aware Recommender System (SARS) was developed [

7]. SARS involves recommendations comprising multiple sessions [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Personalized recommendations typically rely on the user's current interaction to infer their short-term behavioral intentions. While short-term behaviors significantly influence future interests and are thus considered as short-term preferences, sessions too distant from the short-term period are classified as long-term preferences. Users have both long-term and short-term preferences, integrated into their overall intention preference for recommendations [

1,

11]. This method's limitations include overlooking context information and a rigid definition of short-term preferences based on the last session, which can limit recommendation adaptability.

The correlation between a product and the current product represents potential information that should be considered in understanding the real intentions of consumers. Additionally, previous studies have often limited the definition of short-term preferences to the last session [

11]. This approach can lead to recommendations that are too rigid and inflexible. This rigidity arises because a session's definition is based on time intervals, as mentioned earlier. If a user's intentions span a period that extends beyond the confines of a single session, this behavior pattern may not accurately represent the user's true intentions.

Our work adopts SARS over SBRS, addressing two unresolved shortcomings: the neglect of context information and the inflexible definition of long-term and short-term preferences. We propose a method that considers context information, typically divided into intra-context and inter-context categories. Intra-context refers to additional messages accompanying interactions, while inter-context, based on the session, pertains to information between the current and past sessions. One challenge with context information is its potential irrelevance to the interaction sequence. Another is its tendency to diminish the emphasis on sequential data in recommendations.

Addressing the relevance of auxiliary context information to sequential interaction records, the hidden state in the Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) is suggested to be used as the model's context information [

1]. This method ensures the generated context information, based on past interaction records, is relevant. It also mitigates the issue of the RNN framework forgetting older messages in long sequence data. Therefore, our paper proposes using the prediction representation of GRU as the latent-context information, derived from learning based on past sequential interaction records.

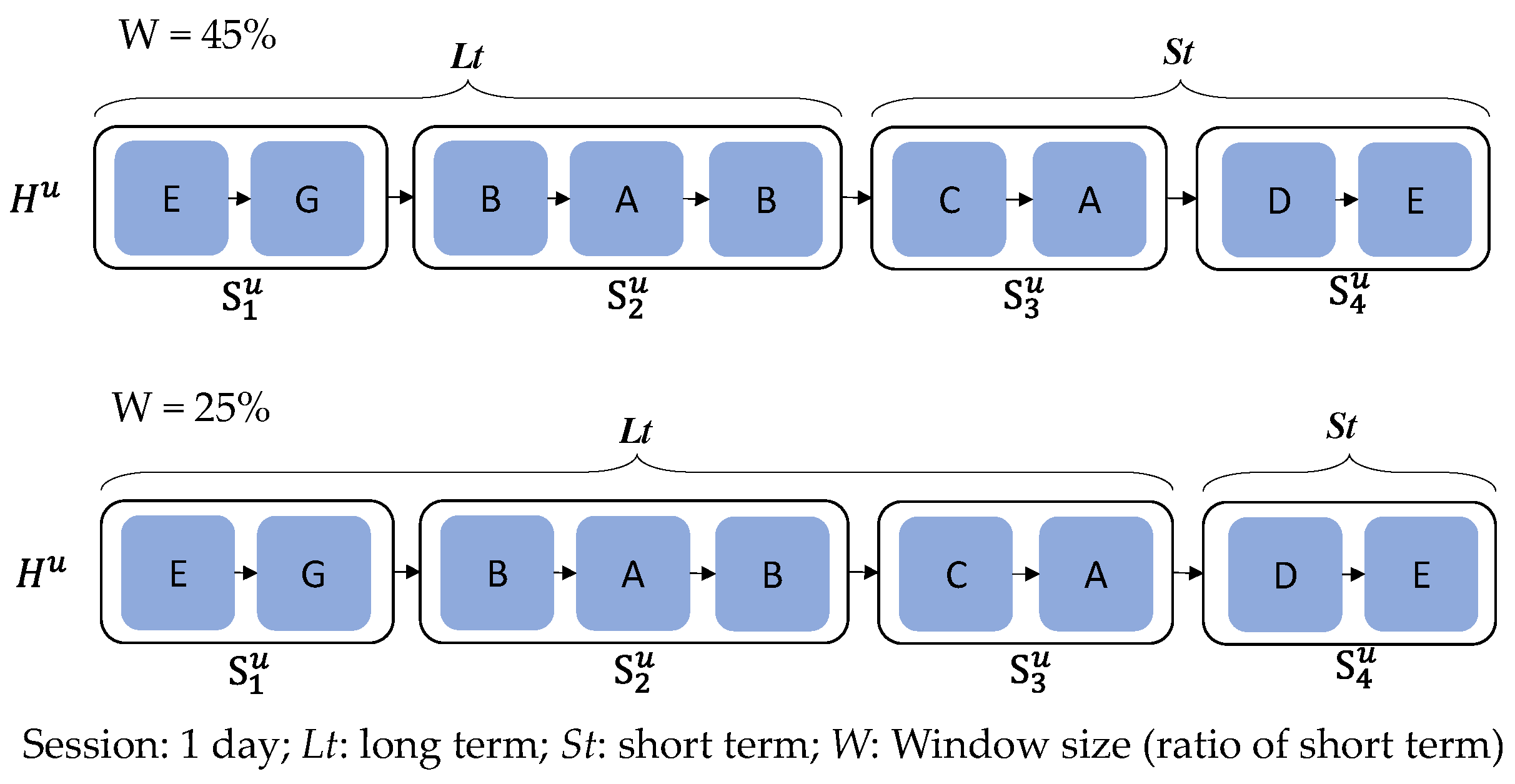

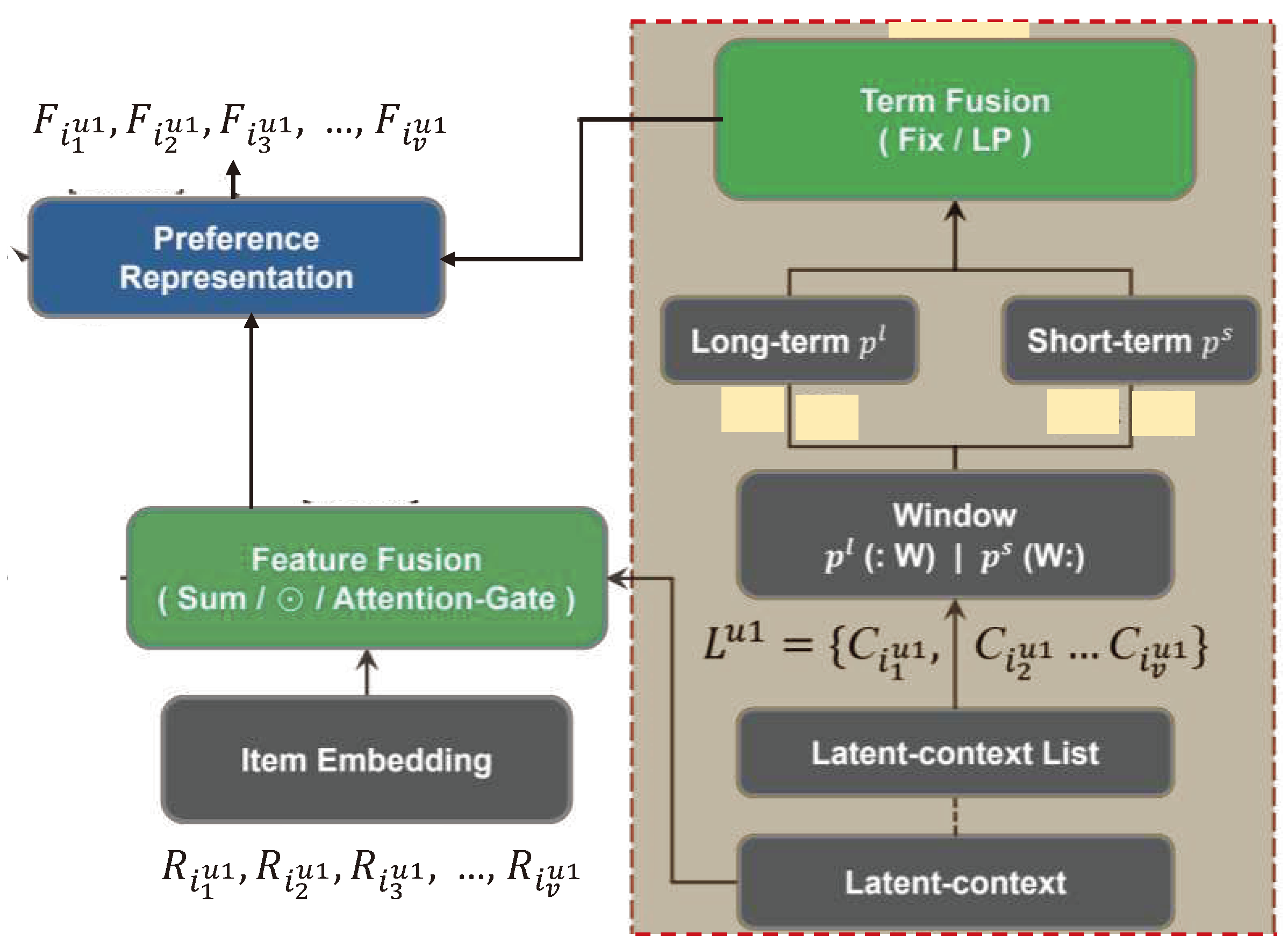

We also address the inflexibility in defining long-term and short-term preferences, due to the time-based division of sessions. Specifically, we use a long-term and short-term window (W) to flexibly capture user preferences. As shown in

Figure 1, setting the window to 45% involves considering 45% of the messages closest to the current message in the 9 interaction records as short-term preferences, with the remainder as long-term preferences. This window method more flexibly identifies the user's actual preferences and divides the range of long-term and short-term preferences accordingly.

Since SBRS lacks the capability for personalized recommendations, we expand our research using SARS. While previous studies considered context information, some limitations were not effectively addressed. Thus, we incorporate latent context information, more closely related to interaction records. Traditional SARS does not consider long-term and short-term preference information along with context information. Our approach, in contrast, considers both as key foundations for improving recommendation performance. Additionally, we use windows to appropriately address the problem of defining long-term and short-term preferences.

In summary, the contributions of this study include:

1. Innovative Combination: We combine GRU networks with attention mechanisms to enhance session-aware recommender systems, focusing on both short-term and long-term user preferences.

2. Latent-Context GRU Model: Introducing the Latent-Context GRU model, a novel approach for capturing latent interaction information, demonstrating improved performance in session-aware recommendation tasks.

3. Comprehensive Evaluation: Rigorous evaluation against current state-of-the-art methods provides a detailed analysis of its effectiveness and potential for further development.

2. Related Work

In traditional recommendation systems, prevalent methods include POP (Most-Popular) and Item-based Nearest Neighbor (Item-kNN) [

12]. Subsequent developments have introduced methods like Collaborative Filtering (CF) [

13], Matrix Factorization (MF) [

14,

15], and Markov Chain (MC) [

8]. These methods utilize user click data as the basis for recommendations, where clicks during browsing represent varying preferences or interests of users, to predict their next item of interest.

Sequential recommendation, a primary branch of recommendation systems, is further divided into session-based and session-aware recommendations. HCA [

1], a hierarchical neural network model, focuses on enhancing short-term interests by capturing the complex correlations between adjacent messages within each time frame. As RNN tends to gradually forget past information due to long-term dependencies, this method helps the system retain information.

GRU4Rec [

2], is a recommendation system model employing the RNN approach. This model continually learns from past features through RNN, combined with the timing of data clicks, to construct a highly effective recommendation method at that time. Compared to traditional methods, RNN adds a sequential consideration, with experimental results underscoring its effectiveness and establishing neural methods' status in recommendation systems.

Neural Session-Aware Recommendation (NSAR) [

9] operates under session-aware recommendation, incorporating all sessions into the model for learning and predicting the next item. This work discusses the timing of feature integration, positing that different integration opportunities significantly affect recommendation performance, hence proposing two strategies: pre-combine and post-combine.

Inter-Intra RNN (II-RNN) [

16] is a two-layer RNN architecture model which can effectively enhance recommendation performance and expedite feature learning. This is because the final prediction representation of the inner network is passed to the initial hidden state of the outer network. The outer network thus does not start learning from scratch, a method whose effectiveness is proven by this research. CAII [

17] is another two-layer GRU model which utilizes session information, including item ID, image characteristics, and item price, to compare these features and achieve a balanced CAII. The CAII-P strategy emerged as the best solution in this research, suggesting that image features do not substantially enhance recommendation quality. This also indicates that session information is not directly correlated with sequential data, a key motivation for our study.

The discussed research highlights that personalized recommendations cannot be solely based on session-based methods. Hence, session-aware recommendation research has been extended. Additionally, the use of latent context information as an auxiliary method in recommendation systems has been explored but not extensively developed.

Our work builds on session-aware recommendation, integrating latent-context information and long-term and short-term preference features. We adopt HCA's [

1] approach of using GRU prediction representation as an auxiliary feature for model learning, treating such information as latent-context. Drawing from NSAR's [

9] pre-combine and post-combine feature combination strategies, we revise the Attention-Gate formula for feature fusion calculations. Our proposed method's main framework follows the inner and outer GRU architecture of II-RNN [

16], with a significant difference: while II-RNN inputs only item IDs, our method also incorporates latent content information and designs for processing long-term and short-term preferences.

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Problem Statements

Consider a set of users

U, where each user

u possesses a historical interaction record

. These records consist of

t sessions, each ordered chronologically by the time of interaction. Within each session, denoted as

, there are

v items with which the user has interacted, also arranged in the order of interaction within that session. The objective is to predict a set of items {

ir1,

ir2, …,

irk} that the user is most likely to interact with next. These predicted items are typically ranked in descending order of interaction probability.

Table 1 lists the symbols used in this paper, with additional terms introduced in the subsequent sections.

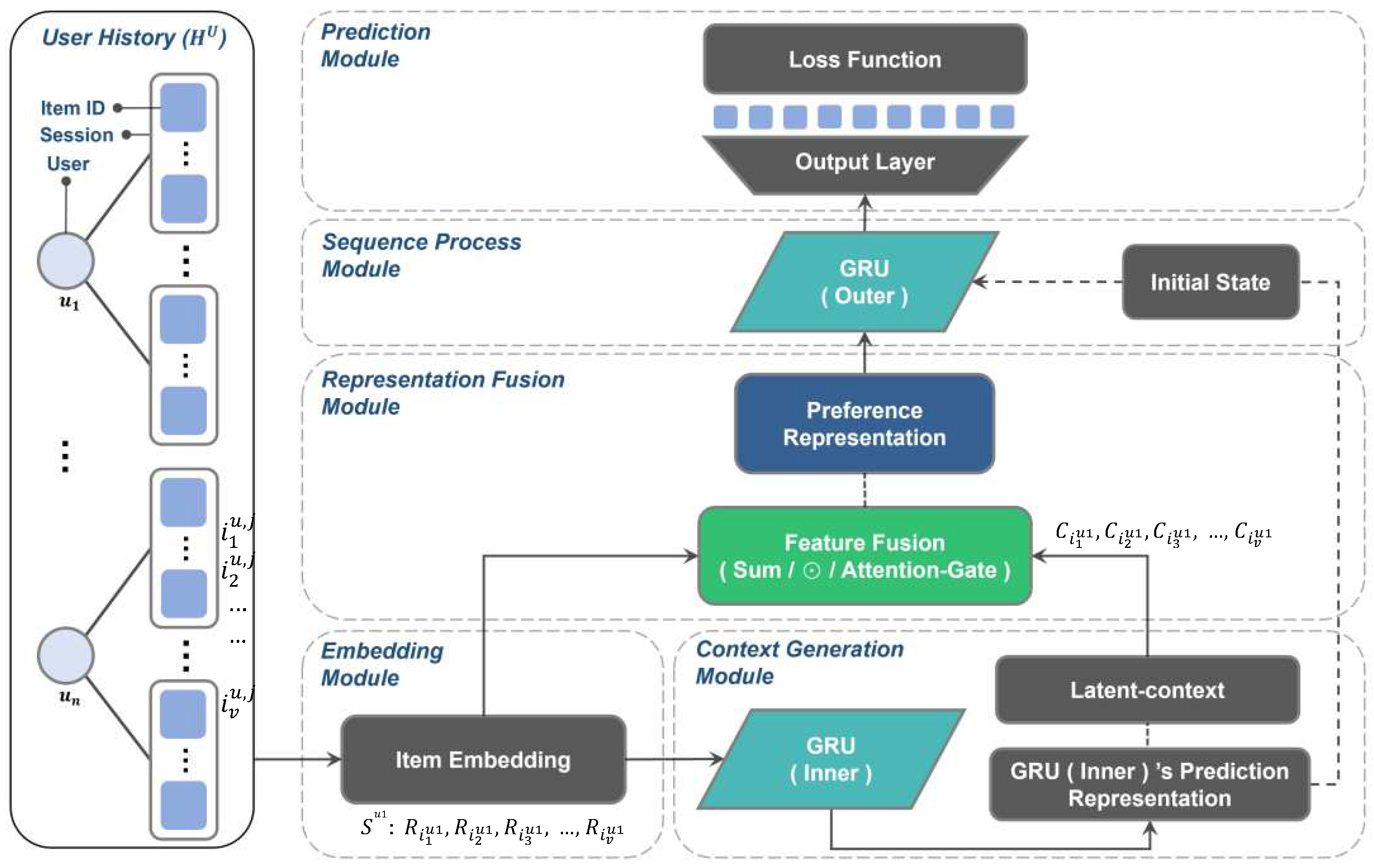

3.2. LCII Architecture

Figure 2 depicts the architecture of the proposed method, named LCII (

Latent

Context

II). The architecture consists of five modules: Embedding Module, Context Generation Module, Representation Fusion Module, Sequence Processing Module, and Prediction Module.

Specifically, the Embedding Module first generates a random number table, tailored to the size of the input data. It then converts the item ID into an embedded representation, which becomes the input for the model.

The Context Generation Module generates potential context information that is considered for recommendations. As GRU (Inner) processes the embedded representation sequentially, a predicted representation is generated one-by-one, based on the latent features learned previously, and thus, it is closely related to the interactive Item. The prediction representation generated by GRU (Inner) is treated as this potential context information.

The Representation Fusion Module activates after acquiring potential context information. It employs two distinct strategies for this purpose: Pre-combining and Post-combining. These strategies are used to create the Preference Representation. In essence, these strategies integrate information from two key processes: feature fusion and term fusion. Feature fusion involves extracting session features by merging item embeddings with latent context information, effectively capturing the current session's characteristics. Meanwhile, term fusion focuses on aggregating latent context information that reflects both long-term and short-term user preferences. This dual approach in the Representation Fusion Module ensures a comprehensive integration of immediate session data with overarching user preference trends.

Subsequently, the Sequence Processing Module uses GRU (Outer) for learning and prediction. The GRU (Outer) accepts the first prediction representation from GRU (Inner) as the initial state, receives sequentially the preference representation, and produces the final prediction. The predictions are fed into the Prediction Module. Prediction Module ultimately produces the user's recommendation list and provides the prediction evaluation.

3.2.1. Embedding Module

We use Item2vec [

18] to convert each item ID into an embedding vector. A lookup table for all the items is constructed as an embedding matrix of size

M×

d, where

M is the total number of items and

d is the embedding size. A user session

of v items

is then embedded, using the lookup table. The resulting embeddings,

,

, …,

, are the Item Embeddings of the user session. Consider when the processing of user

u reaches the

p-th item, denoted as

, in the

j-th session

. All items from the first session up to this

p-th item collectively form the current set of input item embeddings. These embeddings are then processed to extract their latent contexts. This process results in the division of the embeddings into long-term and short-term preferences, which are handled in the subsequent modules.

3.2.2. Context Generation Module

The output from the Embedding Module constitutes the input for the Context Generation Module. The primary objective of this research is to identify and capture latent interactive information, herein referred to as 'Latent-context'. The process for generating this content information commences with the input of the embedding-transformed representation into a GRU, designated as the GRU (Inner). That is, , , …,, goes through the GRU (Inner) and produces the latent context …. Within this neural network framework, user information is subject to a learning process.

Upon each iteration through the GRU, two distinct outcomes are yielded: the Hidden State and the current Prediction Representation. The Prediction Representation, as derived from the GRU, is conceptualized as Latent-context and is subsequently stored within a dedicated Latent-context list. This list is further employed by another GRU, named GRU (Outer). The rationale for selecting this specific information as Latent-context is based on the methodology of generating the Prediction Representation at any given temporal point. This involves using both the Hidden State and the current interaction record as inputs. The Hidden State represents a cumulative preference profile, developed through the analysis of historical interaction records up to the current moment. Consequently, the Prediction Representation, grounded in these derived preferences, facilitates the generation of user-specific items of potential interest.

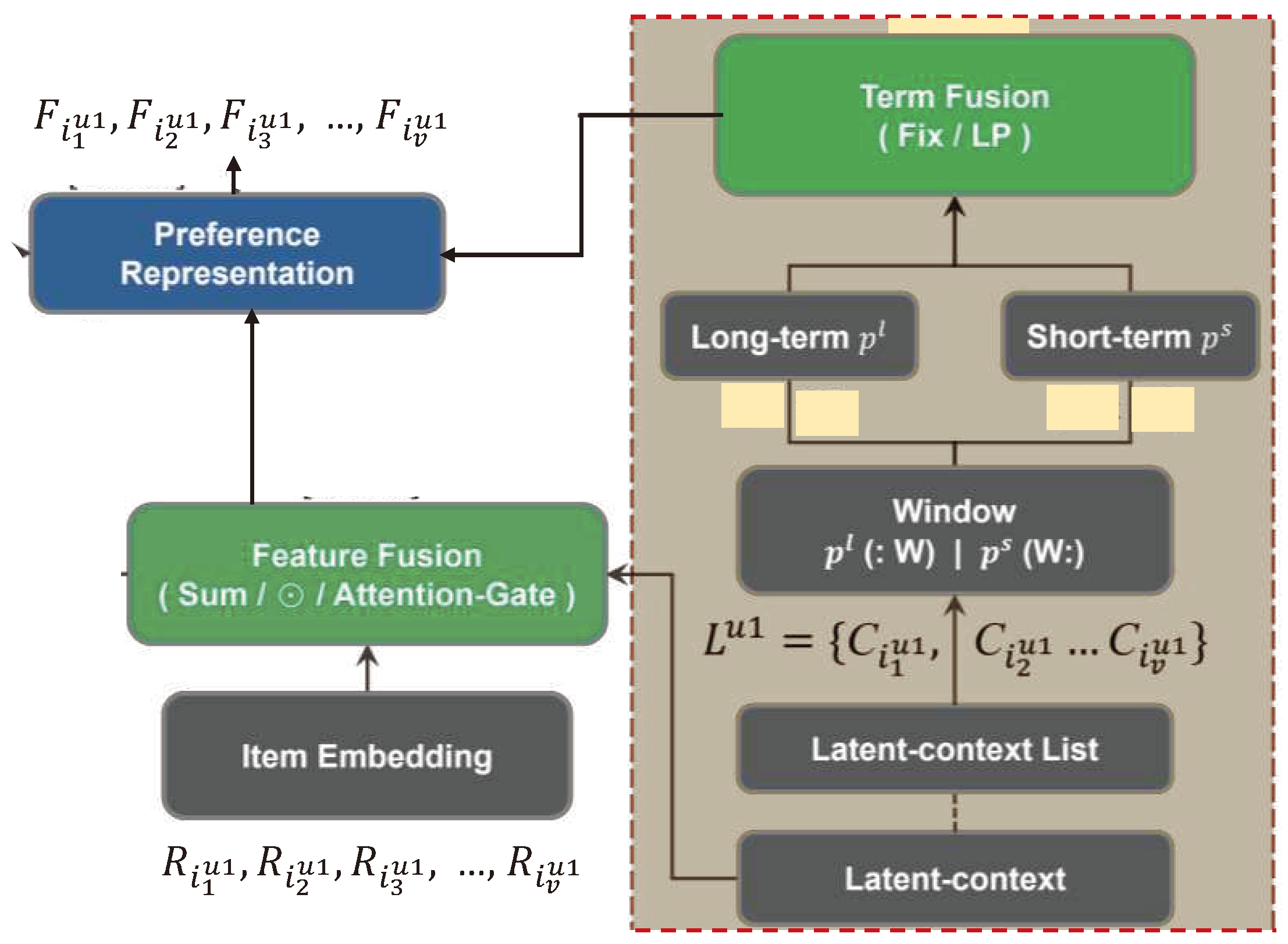

3.2.3. Representation Fusion Module

Upon completion of the initial two modules, we acquire two key outputs: the Item Embedding and the Latent Context. These outputs are subsequently utilized as inputs for the Representation Fusion Module. The primary aim of this module is to integrate the two features to derive a unified User Preference Representation.

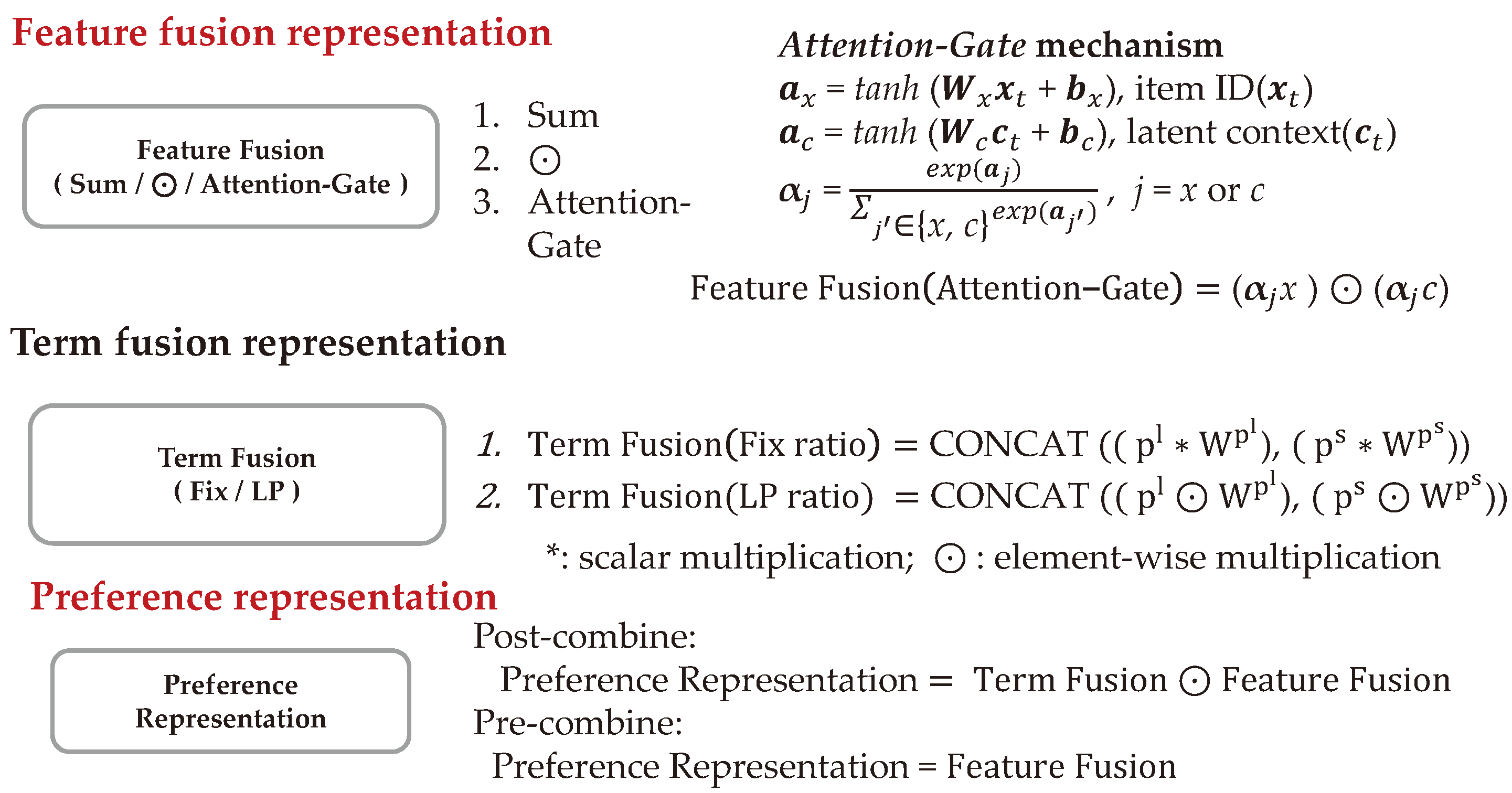

There are three ways to combine two representations into a new representation having the same number of dimension in this study: Vector Addition, Element-wise Vector Multiplication, and the Attention-Gate Mechanism [

9]. Vector Addition involves the straightforward process of summing corresponding vector elements. Conversely, Element-wise Vector Multiplication entails the multiplication of corresponding elements in the vectors. The Attention-Gate Mechanism, adapted from the formula outlined in [

9] and modified to exclude the phase content vectors from that study, aims to identify and emphasize the most salient features among the comparison set. This mechanism operates by assigning a calculated weight (scalar) to these features based on their relevance, which is then multiplied back into the original inputs and merged through element-wise multiplication.

The basic LCII integrates the Item Embedding and the Latent Context using one of the three ways, without the engagement of long and short terms, and generates the User Preference Representation. The basic LCII can be extended with two strategies, both operate with term fusion representation to generate the Preference Representation: Pre-combining and Post-combining.

Within the context of Term Fusion [

9], the computation of long-term and short-term preferences uses latent-context list as a source, divides the list based on the setting ratio of the window size. For example, setting the window of 30% for a sequence of 19 items will grab 30% of the nearest neighbor information as a short-term preference (

ps). The results are (

…

) as short-term preference and (

…

) as long-term preference (

pl). LCII sets the window size using either the Fixed ratio (Fix) or the Learning Parameters ratio (LP). The Fix sets a fixed window size, which is a pre-determined parameter. The LP learns the window size dynamically from the data. The key point of learning is that the weight matrix is generated based on the size of the range divided by the long-term and short-term windows, so the long-term and short-term preference information within the range can be learned and the weights will be updated and learned from iterations.

Thus, LCII-Pre combines the item embedding with the term fusion representation, again, using one of the three ways three ways (Vector Addition, Element-wise Vector Multiplication, and the Attention-Gate Mechanism). As shown in

Figure 2, the LCII combines the term fusion representation with the item embedding into the feature fusion representation. This representation is directly used as the Preference Representation for next module. The strategy used is called

pre-combining, and this method is referred to as the

LCII-Pre method.

Alternatively, the LCII may use another strategy to combine term fusion representation to generate the Preference Representation. The item embedding is first combined with the latent context, using one of the three ways (Vector Addition, Element-wise Vector Multiplication, and the Attention-Gate Mechanism), to become the feature fusion representation. The Preference Representation is generated by the Element-wise Vector Multiplication between feature fusion representation and term fusion representation. The strategy used is called post-combining, and this method is referred to as the LCII-Post method.

This process is graphically depicted in

Figure 3, depicting the operation of the fusion module. The representation fusion of LCII-Pre is shown in

Figure 4, while that of LCII-Post is shown in

Figure 5. The Preference Representation serves as the input to the Outer GRU in the subsequent module, as described next.

3.2.4. Sequence Processing Module

This module involves integrating the Preference Representation with the predictive output of the inner GRU into the outer GRU. A crucial aspect to consider is the discrepancy between the dimensions of the temporary message (output from inner GRU) and the dimensions of the hidden state. To address this, we employ the embedding details of the initial element of the predictive representation to establish the initial state for the GRU's hidden state. This approach, as delineated in the study [

16], primarily addresses the 'cold start' challenge commonly encountered in Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) at the onset [

10,

16,

19]. By assigning an initial value to the initial Hidden State within the recursive neural network, the model can more rapidly adapt to learning and predicting tasks. Consequently, the use of temporary messages, particularly the adoption of the inner GRU's predictive output as the initial value, plays a pivotal role in expediting the learning of user preferences and enhancing the efficacy of predictions in GRU-based models.

3.2.5. Prediction Module

The prediction module operates as follows: First, it derives a representation from user preferences during the sequence processing phase. This representation is processed by a Feedforward Neural Network, which adjusts the embedding to match the original interaction record's format. The module then compares this representation to the actual data (ground truth), producing scores that rank items by relevance. The model's accuracy is evaluated using the softmax cross-entropy loss function, comparing the predicted and actual data across all user sessions. This process trains the LCII model to make accurate item recommendations. In the final step, the model follows the Top@k recommendation approach to generate a list of recommended items.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Datasets and Pre-Processing

Three well-known datasets were used in the experiments: Steam [

20], MovieLens 1M [

21], and Amazon [

22]. The Steam dataset comprises video game platform review data, featuring 2,567,538 users, 15,474 items, and 7,793,069 interaction records. The MovieLens 1M dataset, known for its movie rating data, includes information about item categories and encompasses 1,000,209 interaction records. The Amazon e-commerce dataset focuses on clothing, shoes, and jewelry shopping data from 2012 to 2014, containing 402,093 users, 140,116 items, and 770,290 interaction records. With regard to the data preprocessing method, Steam and MovieLens 1M datasets were preprocessed following the method described in [

10], while the Amazon dataset followed the method in [

17].

The preprocessing details are as follows: For MovieLens 1M and Steam, the session time division is set to one day (60*60*24 seconds); the maximum session length is capped at 200 for MovieLens 1M and 15 for Steam. The data filtering conditions are consistent across datasets. For each user, there must be at least two sessions, and each session must have a minimum of two interactions. Each interaction (i.e., item ID) should occur at least five times, and the number of user interaction records (i.e., interaction number of items) should be five or more. Additionally, the ratio of training to testing data is set at 8:2.

For the Amazon dataset, session division is based on interactions occurring at the same time point, with a maximum session length of 20 and a minimum of three sessions. The maximum session lengths for Steam, MovieLens 1M, and Amazon are 15, 200, and 20, respectively. The ratio of training to testing is also 8 to 2.

Table 2 lists the characteristics of datasets after pre-processing.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics and Parameter Settings

In the experiment, this study employs Recall@K, MRR@K, and NDCG@K as the evaluation metrics. The calculation of Recall@K is based on the top K predictions, with the K value set to 5, 10, and 20 as evaluation criteria. The optimal experimental parameter settings for each dataset are as follows. Amazon Configuration: Window ratio is set to 65, and the ratio of long-term to short-term preference in the fixed ratio strategy is 0.5/0.5. The number of iterations is 100, and the learning rate is set at 0.001. Steam Configuration: Window ratio is 4, with the long-term to short-term preference ratio in the fixed proportional strategy set to 0.2/0.8. The number of iterations is 200, and the learning rate is 0.001. MovieLens 1M Configuration: Window ratio is 30, and the long-term to short-term preference ratio in the fixed ratio strategy is 0.8/0.2, with 200 iterations. The learning rate is 0.01.

The feature fusion method utilizes the Attention-Gate, and the term fusion method employs a fixed ratio. Other hyperparameters, set as common parameters, include an embedding/GRU hidden unit size of 80, inner/outer GRU layers of 1, a batch size of 100, and a dropout rate of 0.8. The experimental optimizer is the Adam optimizer, and the loss function used is the Cross Entropy Loss Function.

4.3. Baseline Models

To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed method, we conducted comparisons with the following well-established methods:

4.4. Performance Comparisons

4.4.1. Performance of Different Feature Fusion Strategies

Given that the Amazon dataset is compatible with all recommendation methods under consideration, we initially selected the feature fusion method based on this dataset. The optimal solution identified here was then applied to subsequent experimental analyses. For these experiments, we utilized the LCII model. Three feature fusion strategies were examined: Sum, Element-wise Multiplication (⊙), and the Attention-Gate mechanism. The experimental results are presented in

Table 3, where the best result is highlighted in bold and the second-best score is underlined, as will be marked in subsequent charts.

The Attention-Gate mechanism mitigates conflicts in fusion between messages with differing feature content. By leveraging calculated weights, Attention-Gate assesses the influence of each feature on the model, enabling it to prioritize certain feature information over others during different time periods. This approach effectively reduces the dominance of one feature type over another. In terms of prediction accuracy, without considering sorting, Attention-Gate performs the best. When sorting indices are taken into account, Attention-Gate still competes closely with the other two fusion methods. Therefore, based on these experimental results, the Attention-Gate mechanism will be used for experimental analysis in subsequent comparison models.

4.4.2. Performance of Different Windows

In the experiments, we will utilize the Learning Parameters ratio (LP) in LCII-Post Term Fusion as the experimental model. The experiments in this section aim to validate the effectiveness of the long-term and short-term strategies and to examine the division between them. An inadequately sized window, either too small or too large, may result in suboptimal performance. Finding the right balance between long and short-term considerations is a crucial aspect of this experimental phase.

Table 4 presents the experimental results on the Amazon dataset. When the window is set to 65%, the MRR reaches its optimum, suggesting that this setting effectively brings the real recommendation target closer to the top of the list. In other words, using 65% of the information in the capture window as a short-term preference can effectively prioritize the recommendation target. More experimental results are summarized here: For the MovieLens 1M dataset, the optimal window setting is 30%, with 35% being the second best. For the Steam dataset, the best parameter setting is a window of 4%, followed closely by 3%. These experiments demonstrate that different datasets have unique characteristics for the optimal parameter. Subsequent experiments will therefore employ the optimal window setting for each dataset as a fixed parameter for comparative analysis.

4.4.3. Long-term and Short-term Fixed Ratio Performance

In this section, we assess the recommendation performance using a fixed ratio (Fix) for long/short-term preferences. The experiment tested various parameter settings, with combinations of [long-term/short-term] preferences set at [0.8/0.2], [0.5/0.5], and [0.2/0.8]. Additionally, extreme setting combinations of [1/0] and [0/1] were evaluated, where the former exclusively considers long-term preferences and completely disregards short-term ones, while the latter does the opposite.

The experimental results are summarized below. From the Amazon dataset, it is evident that both Post-combine and Pre-combine strategies achieve optimal performance with a fixed ratio of [0.5/0.5]. This finding suggests that the representation model requires a balanced consideration of both short-term and long-term preferences for best results. For the MovieLens 1M dataset, the Post-combine outcome mirrors that of Amazon, with the optimal configuration for Pre-combine being [0.8/0.2]. Notably, focusing solely on short-term preference [0/1] deteriorates model performance. Incorporating long-term information significantly enhances results, yet exclusively considering long-term preference [1/0] is not the most effective strategy.

Furthermore, the Steam dataset results indicate a bias towards short-term preference, implying that information features significantly impact dataset performance. Consequently, the best setting for Post-combine is [0.2/0.8], and for Pre-combine, it is [0/1].

4.4.4. Overall Comparisons

The overall experimental results are presented in

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7, respectively, for datasets Amazon, MoveiLens 1M, and Steam. Most-Popular and Item-kNN are not included when their performance are far worse than the others. Our proposed method demonstrates the best performance in most metrics across the three datasets. Specifically, LCII yields the best results for Amazon, LCII-Pre

Fix for MovieLens 1M, and LCII-Post

Fix for Steam. In the MovieLens 1M dataset, LCII-Pre

Fix outperforms II-RNN and BERT4Rec(+ST+TSA) in Recall@20 by 1.85% and 2.54% respectively, translating to relative increases of 7% and 9.9%. In the Steam dataset, LCII-Post

LP shows a 18.66% and 5.5% higher performance in Recall@20 compared to II-RNN and BERT4Rec(+ST+TSA), corresponding to relative improvements of 39.88% and 9.2%. For Amazon's Recall@20, LCII surpasses II-RNN and CAII by 2.59% and 1.89%, respectively, indicating performance boosts of 11.3% and 8%.

Table 5.

Overall Performance w.r.t. Amazon Dataset.

Table 5.

Overall Performance w.r.t. Amazon Dataset.

| Model |

Recall

@5 |

MRR

@5 |

NDCG

@5 |

Recall

@10 |

MRR

@10 |

NDCG

@10 |

Recall

@20 |

MRR

@20 |

NDCG

@20 |

| Most-Popular |

0.0041 |

0.0022 |

0.0026 |

0.0075 |

0.0025 |

0.0039 |

0.0144 |

0.0030 |

0.0065 |

| Item-kNN |

0.2172 |

0.1796 |

0.1820 |

0.2239 |

0.1804 |

0.2044 |

0.2260 |

0.1806 |

0.2143 |

| II-RNN |

0.2238 |

0.2139 |

0.1926 |

0.2264 |

0.2143 |

0.2080 |

0.2294 |

0.2145 |

0.2117 |

| CAII-P |

0.2295 |

0.2115 |

0.1929 |

0.2342 |

0.2121 |

0.2081 |

0.2364 |

0.2123 |

0.2120 |

| SASRec |

0.0908 |

- |

0.0821 |

0.1007 |

- |

0.0853 |

0.1102 |

- |

0.0877 |

|

0.1093 |

- |

0.0900 |

0.1205 |

- |

0.0936 |

0.1327 |

- |

0.0967 |

|

0.1231 |

- |

0.1060 |

0.1343 |

- |

0.1096 |

0.1409 |

- |

0.1113 |

| LCII |

0.2407 |

0.2157 |

0.2060 |

0.2487 |

0.2168 |

0.2244 |

0.2553 |

0.2173 |

0.2300 |

|

0.2360 |

0.2064 |

0.2017 |

0.2450 |

0.2077 |

0.2204 |

0.2529 |

0.2082 |

0.2275 |

|

0.2368 |

0.2119 |

0.2019 |

0.2467 |

0.2133 |

0.2219 |

0.2538 |

0.2138 |

0.2281 |

|

0.2357 |

0.2127 |

0.2008 |

0.2446 |

0.2140 |

0.2205 |

0.2528 |

0.2145 |

0.2279 |

|

LCII-

|

0.2371 |

0.2147 |

0.2029 |

0.2442 |

0.2156 |

0.2212 |

0.2519 |

0.2162 |

0.2273 |

5. Conclusions

Our study introduces a groundbreaking approach to session-aware recommendations, emphasizing the integration of latent-context features with both long-term and short-term user preferences. The novel methodologies, particularly the LCII-Post and LCII-Pre models, have demonstrated their superiority over traditional recommendation models in our experiments with the MovieLens 1M and Steam datasets. This success highlights the potential of our approach in enhancing the accuracy and relevance of recommendations.

The practical implications of our findings are noteworthy. The LCII model, in particular, emerges as a robust solution for real-world application scenarios. Its balance of performance efficiency and lower execution time costs makes it an attractive option for deployment in various recommendation system environments.

Looking towards future research, there are several promising avenues to explore. The scalability of our proposed models to larger and more diverse datasets represents a significant area for further investigation. Additionally, the integration of more nuanced contextual information, such as user demographics or temporal usage patterns, could further refine the accuracy and applicability of our recommendations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ming-Yen Lin; Formal analysis, Ming-Yen Lin; Investigation, Ming-Yen Lin and Ping-Chun Wu; Methodology, Ming-Yen Lin, Ping-Chun Wu and Sue-Chen Hsueh; Supervision, Ming-Yen Lin; Writing – original draft, Ping-Chun Wu; Writing – review & editing, Sue-Chen Hsueh.

Funding

This research was funded by National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, under grant number MOST109-2221-E-035-064 and by Feng Chia University, Taiwan, under grant number 22H00310.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cui, Q.; Wu, S.; Huang, Y.; Wang, L. A Hierarchical Contextual Attention-Based GRU Network for Sequential Recommendation. arXiv:1711.05114. 2017. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.05114 (accessed on 2022/9/23).

- Hidasi, B.; Karatzoglou, A.; Baltrunas, L.; Tikk, D. Session-Based Recommendations with Recurrent Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2015. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1511.06939 (accessed on 2022/10/20).

- Hidasi, B.; Karatzoglou, A.; Quadrana, M.; Tikk, D. Parallel Recurrent Neural Network Architectures for Feature-rich Session-Based Recommendations. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems (RecSys '16), 2016; pp. 241-248. [CrossRef]

- Hidasi, B.; Karatzoglou, A. Recurrent Neural Networks with Top-k Gains for Session-Based Recommendations. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM '18), 2018; pp. 843-853. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ren, P.; Chen, Z.; Ren, Z.; Lian, T.; Ma, J. Neural Attentive Session-Based Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM '17), 2017; pp. 1419-1428. [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S. Next-Item Recommendations in Short Sessions. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems (RecSys '21), 2021; pp. 282-291. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, D.; Ling, Y.; Chen, H. A Joint Neural Network for Session-Aware Recommendation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 74205-74215. [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Dong, S.; Zeng, Z. Increasing Recommended Effectiveness with Markov Chains and Purchase Intervals. Neural Computing and Applications 2014, 25, 5, 1153-1162.

- Phuong, T.M.; Thanh, T.C.; Bach, N.X. Neural Session-Aware Recommendation. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 86884-86896. [CrossRef]

- Seol, J.J.; Ko, Y.; Lee, S.G. Exploiting Session Information in BERT-Based Session-Aware Sequential Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR '22), 2022; pp. 2639-2644. [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.Y.; Yanxiang, L.; Chen, H. A Neighbor-Guided Memory-Based Neural Network for Session-Aware Recommendation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 120668-120678. [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, B.; Karypis, G.; Konstan, J.; Reidl, J. Item-Based Collaborative Filtering Recommendation Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 10th international conference on World Wide Web, 2001; pp. 285-295.

- Linden, G.; Smith, B.; York, J. Amazon.com Recommendations: Item-To-Item Collaborative Filtering. IEEE Internet Computing 2003, 7, 1, 76-80. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhou, M.; Li, S.; Shang, M. An Inherently Nonnegative Latent Factor Model for High-Dimensional and Sparse Matrices from Industrial Applications. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2018, 14, 5, 2011-2022. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhou, M.; Li, S.; Xia, Y.; You, Z.H.; Zhu, Q.; Leung, H. Incorporation of Efficient Second-Order Solvers Into Latent Factor Models for Accurate Prediction of Missing QoS Data. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2018, 48, 4, 1216-1228. [CrossRef]

- Ruocco, M.; Skrede, O.S.L.; Langseth, H. Inter-Session Modeling for Session-Based Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Deep Learning for Recommender Systems (DLRS 2017), 2017; pp. 24-31. [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, S. C.; Shih, M. S.; Lin, M. Y. Context Enhanced Recurrent Neural Network for Session-Aware Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Technologies and Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 2023.

- Barkan, O.; Koenigstein, N. ITEM2VEC: Neural Item Embedding for Collaborative Filtering. In Proceedings of the IEEE 26th International Workshop on Machine Learning for Signal Processing (MLSP), 2016; pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Wu, S.; Liu, Q.; Zhong, W.; Wang, L. MV-RNN: A Multi-View Recurrent Neural Network for Sequential Recommendation. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2020, 32, 2, 317-331. [CrossRef]

- Steam dataset. Available online: https://cseweb.ucsd.edu/~jmcauley/datasets.html#steam_data (accessed on 2022/10/20).

- MovieLens dataset. Available online: https://grouplens.org/datasets/movielens/ (accessed on 2022/10/20).

- Amazon dataset. Available online: http://jmcauley.ucsd.edu/data/amazon (accessed on 2022/10/20).

- Kang, W.C.; McAuley, J. Self-Attentive Sequential Recommendation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), 2018; pp. 197-206. [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Pei, C.; Lin, X.; Ou, W.; Jiang, P. BERT4Rec: Sequential Recommendation with Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformer. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM '19), 2019; pp. 1441-1450. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W.L. Cloze Procedure: A New Tool for Measuring Readability. Journalism Bulletin 1953, pp. 415-433. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the North American Association for Computational Linguistics (NAACL), 2019; pp. 4171-4186.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).