Submitted:

10 December 2023

Posted:

11 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 51M15; 51M05

1. Introduction

2. Unveiling Euclidean Geometry’s Bounds-From Past to Present

2.1. Structural Limitations and Misconstructions of Non-Euclidean Methods

2.2. Divergence of Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometry

2.3. Historical to Modern Contrast

2.4. The Richness of Euclidean Geometry

3. Navigating Angle Constructability - A Comparative Exploration

3.1. Constructability within the Non-Euclidean Geometric Scheme

- Construct a line of length (This notion is ingrained in the algebraic view of constructing square roots [15]).

- Subtract .

- Divide by (Assume performing multiple bisection operations; this creates )

- Construct a right triangle with the hypotenuse and the adjacent (Draw a perpendicular line from the line segment of length constructed earlier and intersected with a circle of length ).

- The angle formed between the two lines is .

3.2. Geometric Critique of the Algebraic Construction

3.3. Constructability of Angles Multiples of 3 within the Euclidean Geometric Framework

3.3.1. Geometric Construction of and Angles

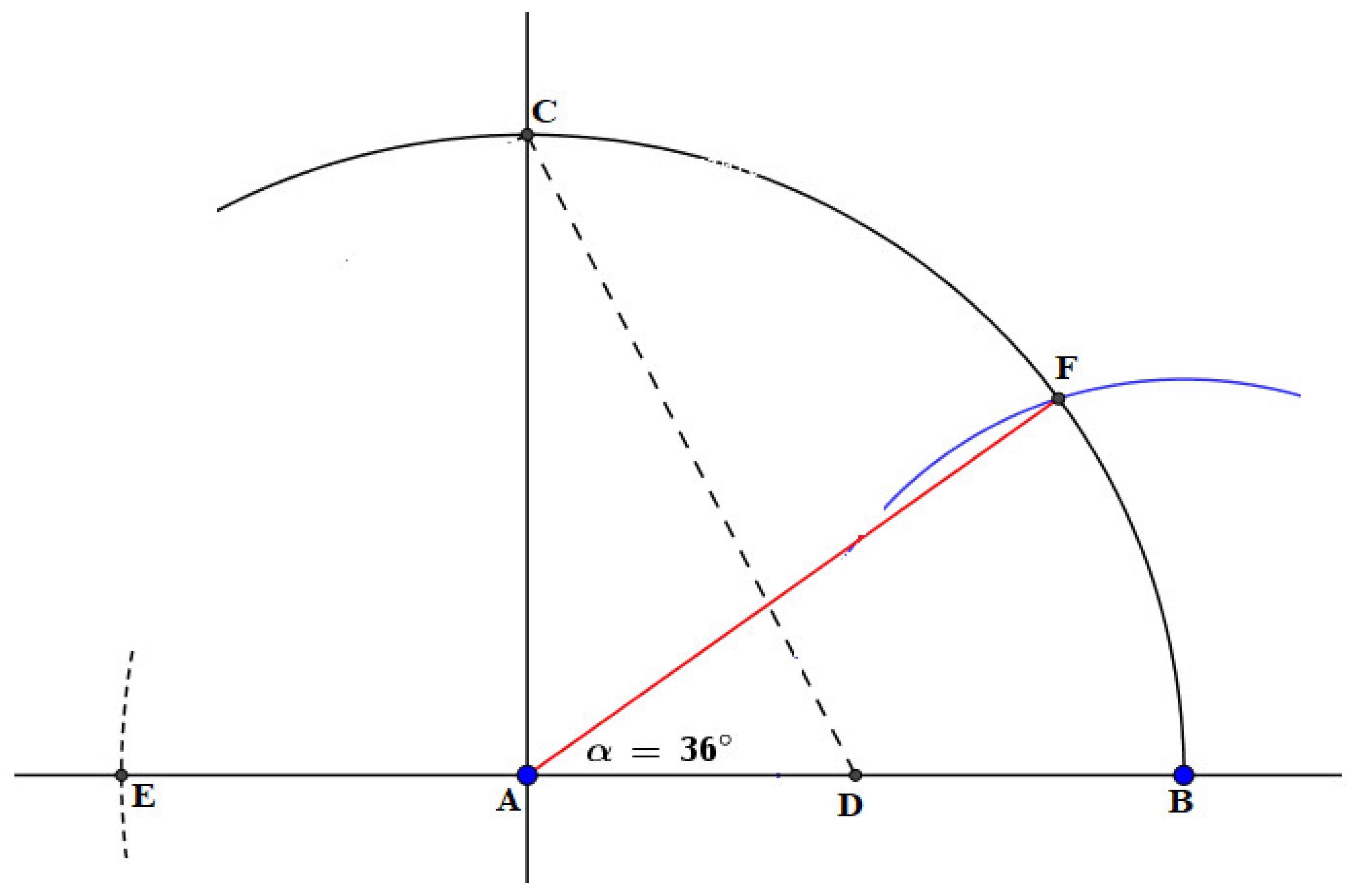

- Construct a straight line (a baseline) through the given two points and .

- Construct a perpendicular to the baseline through point .

- Using radius , construct an arc that intersects the perpendicular line constructed through point at point . since .

- Construct the midpoint of the radius , at a point, .

- Construct a straight line through points and using a straightedge.

- Using radius and point as the center of construction, construct an arc that intersects on the side of at a point,.

- Using the straight-line segment , construct an arc that intersects the curve at a point, F as depicted in Figure 1. The straight-line segment will be referred to as the ( Angle Chord) in the subsequent workflow.

3.3.2. Proof by Geometric Construction

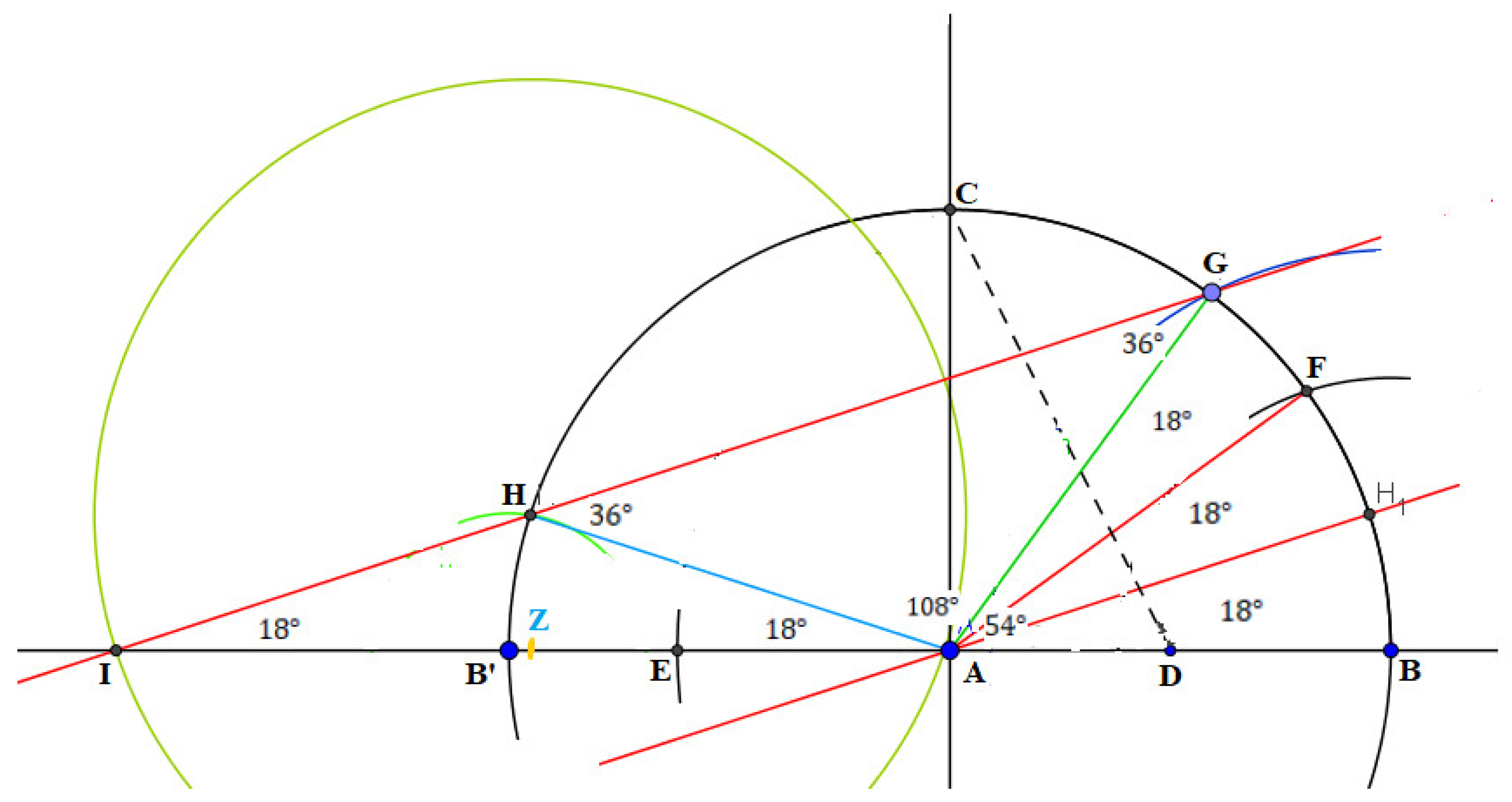

- Construct a straight line (a baseline) through the given two points and .

- Construct a perpendicular to the baseline through point .

- Using radius , construct an arc that intersects the perpendicular line constructed through point at a point such that .

- Construct the midpoint of the radius , at a point, .

- Construct a straight-line segment through points and using a straightedge.

- Using radius and center , construct an arc that intersects on the side of at a point,.

- Using the straight-line segment , construct an arc that intersects the curve at a point, .

- Construct point , a geometric reflection of point , to be the point of intersection between the arc and the baseline .

- Using chord and center , construct an arc that intersects the curve at a point, .

- With the compass adjusted to the chord and using as the center, construct an arc that intersects the curve () at a point, .

- Construct a straight line through points and , to intersect the baseline externally, at a point, .

- Using the straight-line segment and point as the center of construction, construct a circle that passes through points and , circle ().

3.4. Assessing Constructive Accuracy (Non-Euclidean Geometric Validation)

3.4.1. Construction of a Regular Pentagon

- Construct a straight line (a baseline) through the given two points and .

- Construct a perpendicular to the baseline through point .

- Using radius , construct an arc that intersects the perpendicular line constructed through point at point . since .

- Construct the midpoint of the radius , at a point, .

- Construct a straight-line segment through points and using a straightedge.

- Using radius and center , construct an arc that intersects externally at a point,.

- Using the straight-line segment , construct an arc that intersects the curve at a point, . as shown in Figure 1.

- With the compass adjusted radius and using point as the center, construct an arc that intersects the curve at a point, .

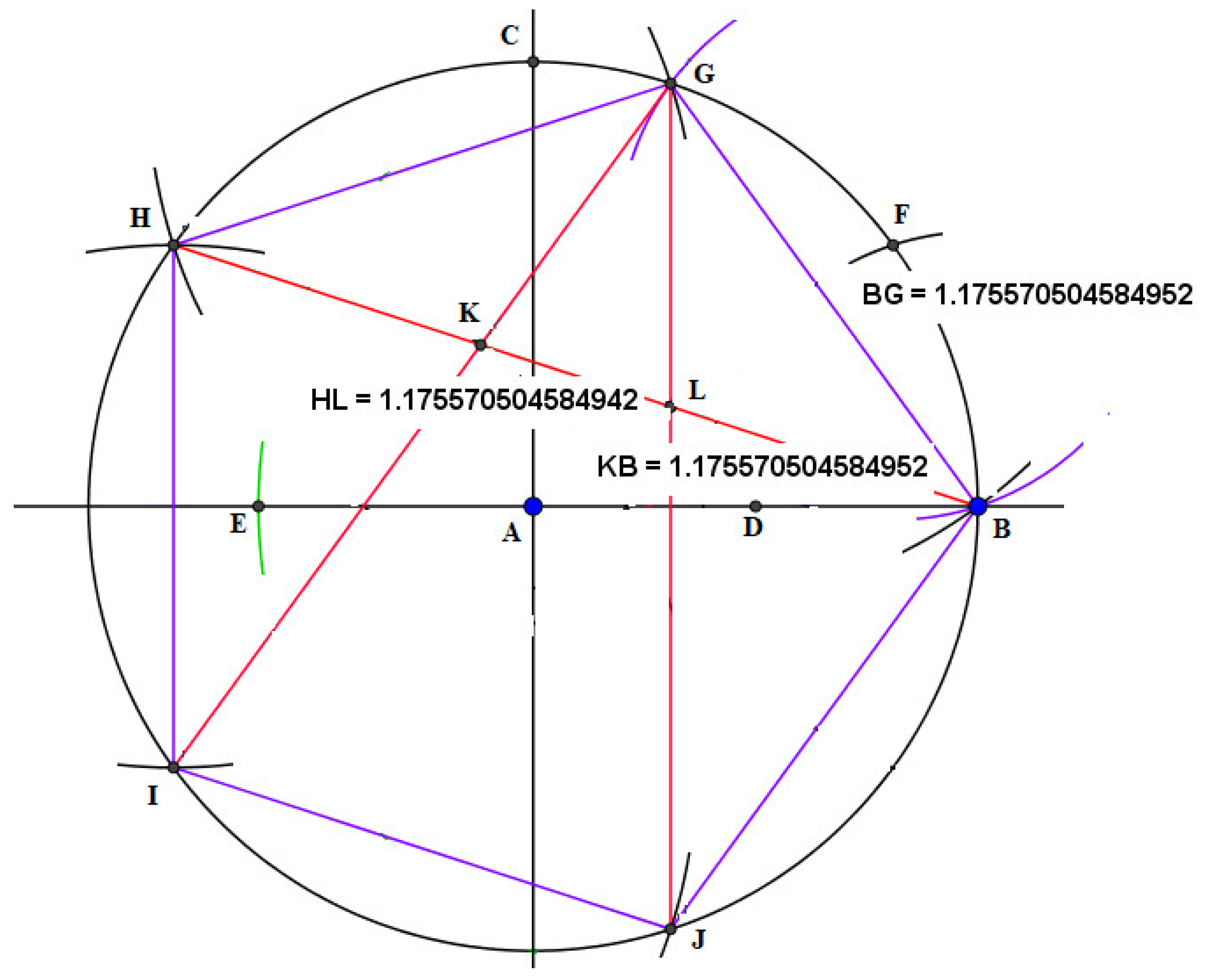

- Using the chord as radius and starting with point as the center of the construction, stroke along the curve three times to produce points , , and respectively. Points , , , , and are equidistant along .

- Construct the chord , , , , and , as shown in Figure 3. These chords (the blue lines) are the sides of the regular pentagon.

- Construct the diagonals , , and .

- Label points and , as the points of intersections between the diagonals and , and and respectively.

3.4.2. Geometric Construction of Angle

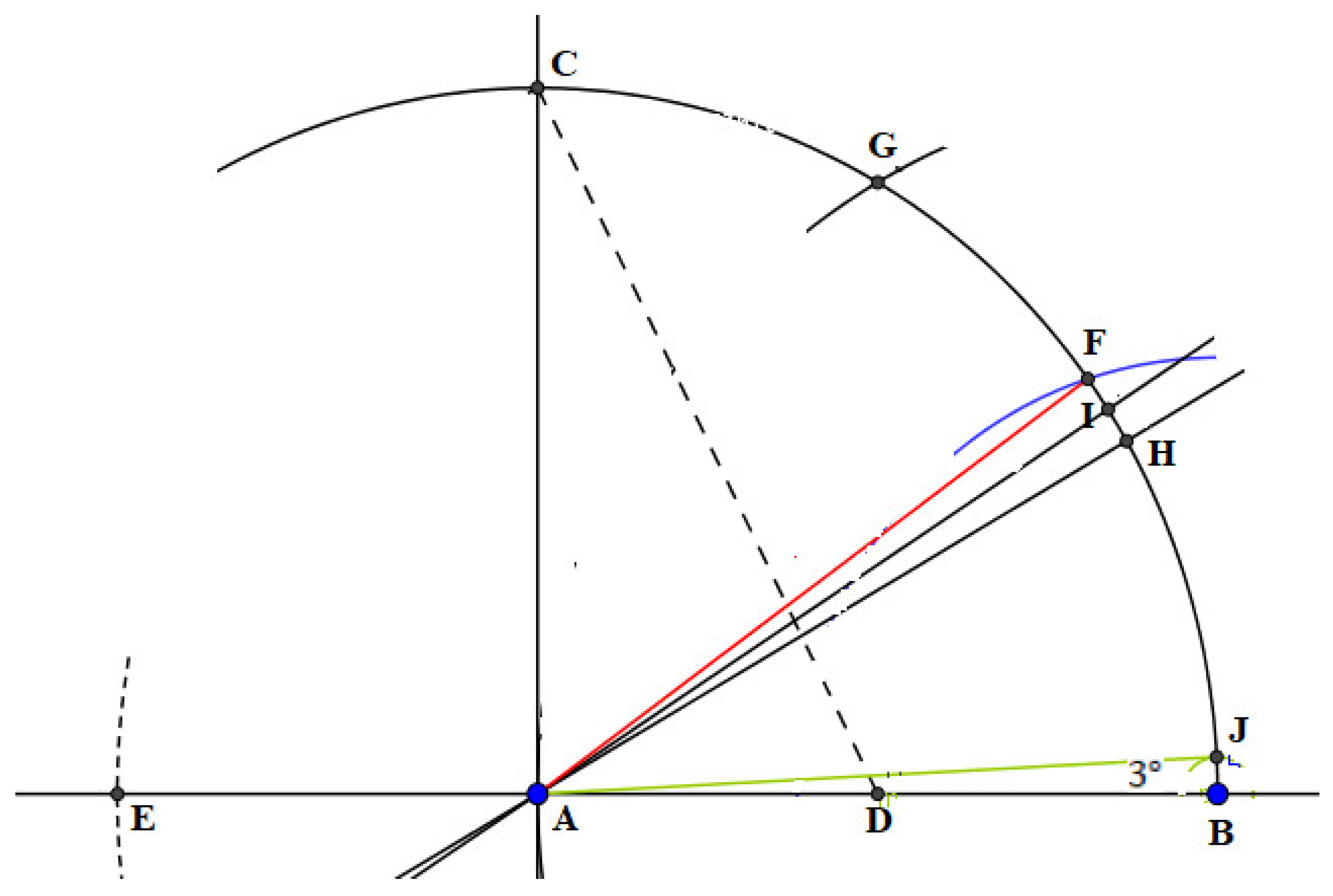

- Construct a straight line (a baseline) through the given two points and .

- Construct a perpendicular to the baseline through point .

- Using radius , construct an arc that intersects the perpendicular line constructed through point , at a point .

- Construct the midpoint of the radius , at a point, .

- Construct a straight-line segment through points and using a straightedge.

- Using radius and point as the center of construction, construct an arc that intersects on the side of at a point,.

- Using the straight-line segment , construct an arc that intersects the curve at a point, . as shown in Figure 1.

- Using radius , and center , construct an arc that intersects the curve at a point, . , implying triangle is equilateral, and .

- Construct the bisection of to intersect the curve at a point, . , since is a bisection of . This implies .

- Construct the bisection of to intersect at a point, . .

- Using either chord or chord and center , construct an arc that intersects the curve at a point, . , as shown in Figure 4.

3.5. Practical Limitations of Non-Geometric Proofs (The Case of Non-Trisectability Angles)

3.5.1. Misalignment of Geometric Concepts

3.5.2. Lack of Geometric Foundation

3.5.3. The Inadequacy of Non-Euclidean Approaches

3.5.4. Completeness of Euclidean Geometry

4. Independence of Euclidean Geometry

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: MATLAB Code Analysis

-

The MATLAB code leverages symbolic computations to precisely calculate lengths and angles, aligning with the geometric constructions outlined. It utilizes symbolic variables to represent geometric entities and employs numerical computations to ensure accuracy. The code’s structure is coherent with the step-by-step geometric procedure, emphasizing the adherence to Euclidean principles in the computational analysis. The code carefully calculates the magnitude of radius , establishes the radius , and solves for points of intersection, crucial in constructing points , , , and . The results from the code align with geometric expectations, with angles such as being precisely . This correspondence between the computational results and the expected geometric properties attests to the success of the code in validating the “ Angle Chord” property within the realm of Euclidean geometry. For accuracy check, the code results is computed to 50 decimals. This precision can be extended as desired.%% MATLAB Script for Computational Analysis of Angles Multiples of 3% This MATLAB script provides a computational analysis of Euclidean geometric% constructions related to angles multiples of 3, with a focus on showing% that the 36-degree chord is constructible and subtends an angle of 36 degrees% at the vertex of any constructed isosceles angle.%% Initializing the construction:% Clear the command window, workspace, and sets the display format for numerical values.clc; clear; format long; format compact;%% %%%%%%%%%%%%% Symbolic and Numerical Analysis%% Compute the magnitude of radius CD%% Computes the magnitude of radius CD and sets up symbolic variables.%% Computes the radius EA based on the construction.%% Solves for the points of intersection for circles with radii AB and BF.%% Establishes the point F, which defines the 36-degree angle (AngleFAB).CD = sym(sqrt((1/2)^2 + 1)); % Compute the magnitude CDdigits(50) % Set precision for symbolic computationsvpa(CD) % Display the result%% Compute the radius EA (Point E is constructed using radius CD)AZ4 = sym(CD + (1/2)); % Establish a unit from D along AB on the side of B.EA = sym(AZ4 - 1)BF = vpa(EA) % Set EA as a radius equal to BF%% Solve the points of intersection for two circles: c1-radius (AB)%% c2-radius (BF).syms x yCirclesIntersection1 = [x^2 + y^2 == 1, (x - 1)^2 + y^2 == (BF)^2];vars = [x y]; % Specify the circles x and y variables[solFx, solFy] = solve(CirclesIntersection1, vars);% For a sense check, use %double(a) to examine the numerical resultsxa = double(solFx(1)); % vpa(solFx(1));ya = double(solFy(2)); % vpa(solFy(2));% Establish the point F, that defines the 36 degrees angle: FABF = [xa ya];AngleFAB = vpa(acosd(xa)) % The 36-degrees angle%% Construct the point G such that angle GAB = 60 degrees% The point G is an intersection of two circlessyms x yCirclesIntersection2 = [x^2 + y^2 == 1, (x - 1)^2 + y^2 == 1^2];vars = [x y]; % Specify the circles x and y variables[solGx, solGy] = solve(CirclesIntersection2, vars);cS60x = double(solGx(1)); % vpa(solGx(1));sS60y = double(solGy(2)); % vpa(solGy(2));G = [cS60x sS60y];AngleGAB = vpa(acosd(cS60x)) % The 60-Degrees angle%% Construction of 30-degrees angle (Geometric bisection of angle GAB)% Set a point G1, at the intersection between lines JB and AG1, a point of% chord bisection.G1 = sym([((cS60x + 1)/2) ((sS60y)/2)]); % Intersection (Bisection) point% Compute the slope for the line G1ASlopeG1A = sym(((G1(2))/(G1(1)))); % Slope G1A% Solve for the point H, a point of intersection between G1A and the unit% circleCircleLineIntersection3 = [x^2 + y^2 == 1, ((y - G1(2))/(x - G1(1))) == SlopeG1A];vars = [x y]; % Specify the circle-line x and y variables[solHx, solHy] = solve(CircleLineIntersection3, vars);cSHx = double(solHx(2)); % vpa(solHx(2));sSHy = double(solHy(2)); % vpa(solHy(2));H = [cSHx sSHy];AngleHAB = vpa(acosd(cSHx)) % The 30-Degrees angle%% Construction of 3-degrees angle. This is achievable if we make 33-degrees.% Angle FAH = 36-degrees. We set a point I, the intersection between the% bisection and the unit circle.% Set point I1, the intersection between chord FH and the bisection of angle% FAHI1 = sym([(((xa(1)) + H(1))/2) (((ya(1)) + H(2))/2)]); % Midpoint (Point of Intersection)% Compute slope for the line I1ASlopeI1A = sym(((I1(2))/(I1(1))));CircleLineIntersection4 = [x^2 + y^2 == 1, ((y - I1(2))/(x - I1(1))) == SlopeI1A];vars = [x y]; % Specify the circle-line x and y variables[solIx, solIy] = solve(CircleLineIntersection4, vars);cSIx = double(solIx(2)); % vpa(solIx(2));sSIy = double(solIy(2)); % vpa(solIy(2));I = [cSIx sSIy]; % Point of IntersectionAngleIAB = vpa(acosd(cSIx)) % Display AngleIAB = 33 degrees%% Compute the difference between AngleIAB and AngleHAB to get angleIAHangleIAH = AngleIAB - AngleHAB % Display AngleIAB = 3 degrees

References

- Borceux, F. Euclid’s Elements. In An Axiomatic Approach to Geometry, Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2014, pp. 43–110. [CrossRef]

- Billingsley, H. The Elements of Geometrie of the Most Ancient Philosopher Euclide of Megara; John Daye: London, 1570. [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne, R. Teaching Geometry According to Euclid; 2000.

- Heath, T.L. The Thirteen Books of the Elements, 2nd ed.; Dover Publications: New York, 1956; Volume 1. Books 1-2 (first published 1925). [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo, J.M.; Center, P.D. The Euclidean Mousetrap: Schopenhauer’s Criticism of the Synthetic Method in Geometry. Ideal. Stud. 2008, 38, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath; Thomas L. The Thirteen Books of Euclid’s Elements, Translated from the Text of Heiberg, with Introduction and Commentary, Second Edition; University Press: Cambridge, 1926; Volume 3; Available in Dover Reprint.

- Kimuya, A.M.; Karanja, S.M. Incompatibility between Euclidean Geometry and the Algebraic Solutions of Geometric Problems. Eur. J. Math. Stat. 2023, 4, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaszczyk, P. From Euclid’s Elements to the Methodology of Mathematics. Two Ways of Viewing Mathematical Theory 2019, 10, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mammana, C.; Villani, V. (Eds.) Perspectives on the Teaching of Geometry for the 21st Century; New ICMI Study Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Prékopa, A.; Molnár, E. (Eds.) Non-Euclidean Geometries: János Bolyai Memorial Volume; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, B.; Galuzzi, M.; Neubrand, M.; Laborde, C. The Evolution of Geometry Education Since 1900. In Perspectives on the Teaching of Geometry for the 21st Century: An ICMI Study; Mammana, C., Villani, V., Eds.; New ICMI Study Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Malkevitch, J.; Meyer, W.; Legiša, P. Geometry in Our World. In Perspectives on the Teaching of Geometry for the 21st Century: An ICMI Study; Mammana, C., Villani, V., Eds.; New ICMI Study Series, Dordrecht, Springer Netherlands, 1998.

- Gray, J.; Gauss and Non-Euclidean Geometry. In Non-Euclidean Geometries: János Bolyai Memorial Volume, A. Prékopa and E. Molnár, Eds. Mathematics and Its Applications; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006.

- Villani, V. The Way Ahead. In Perspectives on the Teaching of Geometry for the 21st Century: An ICMI Study, C. Mammana and V. Villani, Eds. New ICMI Study Series, Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998.

- Stillwell, J. Mathematics and Its History: A Concise Edition. In Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wantzel, P.L. Recherches sur les Moyens de Reconnaitre si un Problème de Géométrie Peut se Résoudre Avec la Règle et le Compass. J. Math. Pures Appl. 1837, 2, 366–372. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, P. A Unique Method for the Trisection of an Arbitrary Angle. Matrix Sci. Math. 2023, 7, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, K. On Euclid and the Genealogy of Proof. J. Philos. 2021, 8, 54–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, E.C. Wittmann, E.C. Designing Teaching: The Pythagorean Theorem. In Connecting Mathematics and Mathematics Education: Collected Papers on Mathematics Education as a Design Science, E. C. Wittmann, Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021, pp. 95–160.

- Buechner, J. Are the Gödel Incompleteness Theorems Limitative Results for the Neurosciences? J. Biol. Phys. 2010, 36, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, T. Computability, Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem, and an Inherent Limit on the Predictability of Evolution. J. R. Soc. Interface 2012, 9, 624–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippov, M.; Zeki, S. On the Necessity of Importing Neurobiology into Mathematics. PsyCh J. 2022, 11, 755–756. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).