Submitted:

10 December 2023

Posted:

11 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Study Design

2.2. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

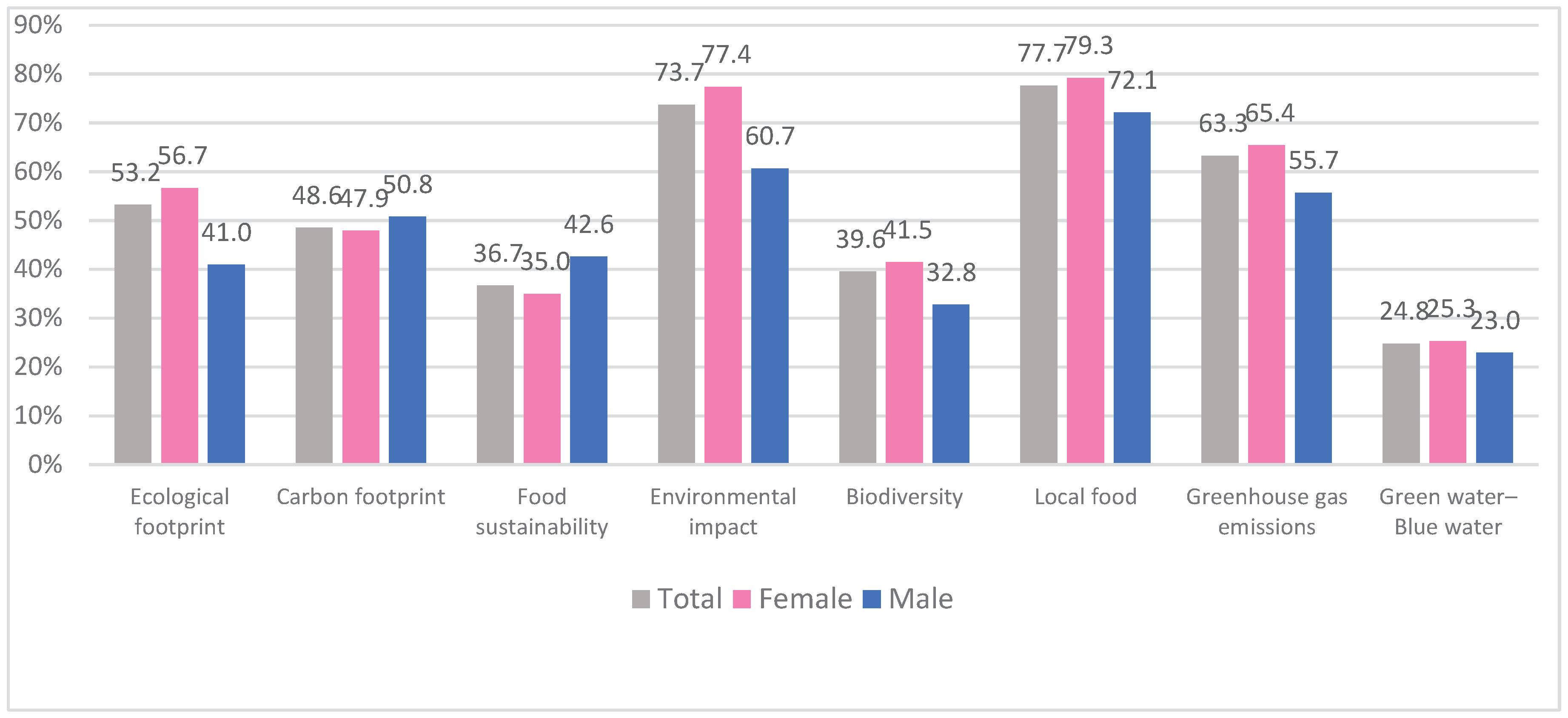

3.1. Level of Knowledge on Food Sustainability Concepts

3.2. Attitudes towards Sustainable Diets

4. Discussion

4.1. Knowledge on Environmental Concepts and Food Sustainability

4.2. Attitudes to Sustainable Diets

5. Study limitation

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire on Food Sustainability Knowledge and Attitudes

- Section 1: Student Background

- 1.

-

Which faculty are you currently enrolled in?

- -

- Faculty of Allied Health Sciences

- -

- Faculty of Architecture

- -

- Faculty of Arts

- -

- Faculty of Business Administration

- -

- Faculty of Computing Science and Engineering

- -

- Faculty of Dentistry

- -

- Faculty of Education

- -

- Faculty of Engineering and Petroleum

- -

- Faculty of Law

- -

- Faculty of Life Sciences

- -

- Faculty of Medicine

- -

- Faculty of Pharmacy

- -

- Faculty of Public Health

- -

- Faculty of Sciences

- -

- Faculty of Sharia and Islamic Studies

- -

- Faculty of Social Studies

- 2.

-

Which degree are you currently undertaking?

- -

- Bachelor’s degree

- -

- Master’s degree

- -

- Postdoctoral degree

- 3.

-

Which year of study are you currently in?

- -

- 1st

- -

- 2nd

- -

- 3rd

- -

- 4th

- -

- 5th

- -

- 6th

- -

- 7th

- 4.

-

What is your mode of study?

- -

- Full-time

- -

- Part-time

- 5.

-

Do you live in university accommodation?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- Section 2: Sociodemographic Data

- 6.

-

What is your gender?

- -

- Male

- -

- Female

- 7.

-

How old are you? (years)_____________________________________________________________________________________

- 8.

-

What is your nationality?

- -

- Kuwaiti

- -

- Non-Kuwaiti

- 9.

-

Which governorate do you live in?

- -

- Al-Ahmadi

- -

- Capital

- -

- Farwaniya

- -

- Hawali

- -

- Jahra

- -

- Mubarak Al-Kabeer

- 10.

-

What is your marital status?

- -

- Single

- -

- Married

- -

- Divorced

- -

- Widowed

- 11.

-

Do you have children?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- 12.

- If you answered yes, how many children do you have? ______

- 13.

-

Are you employed/self-employed?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- 14.

-

How long have you been employed for?

- -

- Less than a year

- -

- 2- 5 years

- -

- 5-10 years

- -

- 10-15 years

- 15.

-

Where are you employed?

- -

- Governmental sector

- -

- Private sector

- -

- Self/family business

- -

- Academia

- -

- Healthcare

- -

- Other

- 16.

-

What is your monthly income?

- -

- Less than 500 KD

- -

- 500 KD – 1000 KD

- -

- 1100 KD – 1500 KD

- -

- 1600 KD – 2000 KD

- -

- 2000 + KD

- 17.

-

What is your weight (in kilograms)?______

- 18.

-

What is your height (in meters, e.g. 1.65)?______

- 19.

-

Are you physically active?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- 20.

-

How many hours per week are you physically active?

- -

- Less than 3 hours per week

- -

- 3 to 5 hours per week

- -

- More than 5 hours per week

- Section 3: Questions on Knowledge on environmental impact concepts and Food Sustainability.

- 21.

- Do you know the following concepts?

| Concept | Yes | No | Heard the term but do not know what it means |

| Ecological footprint | |||

| Carbon footprint | |||

| Food sustainability | |||

| Environmental impact | |||

| Biodiversity | |||

| Local food | |||

| Greenhouse gas emissions | |||

| Green water–Blue water |

- 22.

- On a scale from 1 to 5, to what extent do you consider that each of the following aspects contributes to a sustainable diet?

| Aspects | Not Important at all | Of little Importance | Moderately Important | Important | Very Important | Not sure / Don’t know |

| Low environmental impact | ||||||

| Respectful of biodiversity | ||||||

| No additives | ||||||

| Low processing | ||||||

| Few ingredients | ||||||

| Organic /ecologic products | ||||||

| Plenty of fresh products | ||||||

| Diet rich in vegetables | ||||||

| Diet typical from own culture | ||||||

| Locally produced | ||||||

| Affordable | ||||||

| Easy to follow |

- 23.

-

Do you believe that sustainable diet and healthy diet terms mean the same thing?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- -

- Don’t know

- 24.

- In your opinion, do the following foods have a positive or negative impact towards the sustainability of the planet.

| Food Type | Positive Impact | Negative Impact | I Don’t Know |

| Vegetables | |||

| Meat and its derivatives | |||

| Fish, shellfish, and its derivatives | |||

| Milk and Dairy | |||

| Eggs | |||

| Processed foods | |||

| Carbonated and processed drinks |

- 25.

- From 1 to 5, indicate to what extent you agree with the following statements related to water and its use in food production. 1: “Do not agree” and 5 : “Completely agree”.

| Do not agree | Agree a little | Mostly Agree | Agree | Completely agree | I don’t know | |

| Enough water for the planet is granted by the natural cycle of water | ||||||

| Production of meat-based foods require more input of water resources | ||||||

| Production of plant-based foods require more input of water resources |

- Section 4: Questions on Attitudes towards Sustainable Diets

- 26.

- From 1 to 5: How important is it for you that the products you consume are produced in a sustainable way? 1 Being “Not important at all” and 5 “Very important”.

| Not Important at All | Little Importance | Moderately Important | Important | Very Important | Not sure/Don’t know |

- 27.

- From 1 to 5: To what extent are you willing to pay more money for food and drink products that are produced in a sustainable way? 1 Being: “Not at all” and 5 “Willing”.

| Not at All | Unwilling | Moderately Willing | Quite Willing | Willing | Not sure/Don’t know |

- 28.

- To what extent are you willing to change your current dietary habits towards more sustainability? 1 Being: “Not at all” and 5 “Willing”.

| Not at All | Unwilling | Moderately Willing | Quite Willing | Willing | Not sure/Don’t know |

- 29.

- To what extent are you willing to purchase a food or drink that is labelled with a low carbon and water footprint? 1 Being: “Not at all” and 5 “Willing”.

| Not at All | Unwilling | Moderately Willing | Quite Willing | Willing | Not sure/Don’t know |

- 30.

- To what extent are you willing to reduce consumption of a particular food or drink after knowing that it is one of the foods producing more environmental impact ? 1 Being: “Not at all” and 5 “Willing”.

| Not at All | Unwilling | Moderately Willing | Quite Willing | Willing | Not sure/Don’t know |

References

- Key takeaways from the IPCC special report on climate change and land. unfoundation.org, 2019. Available online: https://unfoundation.org/blog/post/key-takeaways-from-the-ipcc-special-report-on-climate-change-and-land/ (accessed 14 April 2022).

- Global surface temperature, NASA. 2023. Available online: https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/global-temperature/ (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Climate and health country profile – 2015 Kuwait. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1031351/retrieve/ (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Ecological footprint. Global Footprint Network. 2021. Available online: https://www.footprintnetwork.org/our-work/ecological-footprint/ (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Lin, D.; Hanscom, L.; Murthy, A.; Galli, A.; Evans, M.; Neill, E.; Mancini, M.S.; Martindill, J.; Medouar, F.-Z.; Huang, S.; et al. Ecological Footprint Accounting for Countries: Updates and Results of the National Footprint Accounts, 2012–2018. Resources 2018, 7, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwait: CO2 Country Profile. Our World in Data 2020. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions/ (accessed 10 May 2022).

- Nationally Determined Contributions. State of Kuwait - October 2021. Available online: https://epa.gov.kw/Portals/0/PDF/KuwaitNDCEN.pdf (accessed 30 May 2022).

- Environmental impacts of Food Production. Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/environmental-impacts-of-food/ (accessed 7 April 2022).

- Conrad, Z.; Niles, M.T.; Neher, D.A.; Roy, E.D.; Tichenor, N.E.; Jahns, L. Relationship between food waste, diet quality, and environmental sustainability. PLoS One 2018, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2021. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021/ (accessed 11 April 2022).

- Goal 12: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/ (accessed 14 April 2022).

- Burlingame, B., & Dernini, S. (Eds). Sustainable diets and biodiversity. Directions and solutions for policy, research, and action. FAO: Rome, 2010; 13-89.

- García-González, Á.; Achón, M.; Carretero Krug, A.; Varela-Moreiras, G.; Alonso-Aperte, E. Food Sustainability Knowledge and Attitudes in the Spanish Adult Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dernini, S., & Berry, E. M. Mediterranean diet: From a healthy diet to a sustainable dietary pattern. Frontiers in Nutrition 2015, 2-15. [CrossRef]

- Barthelmie, R.J. Impact of Dietary Meat and Animal Products on GHG Footprints: The UK and the US. Climate 2022, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, L.; Alkazemi, D. Trends in Fast-food Consumption among Kuwaiti Youth. International journal of preventive medicine 2019, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almansour, F. D.; Allafi, A. R.; Al-Haifi, A. R. Impact of nutritional knowledge on dietary behaviors of students in Kuwait University. Acta bio-medica : Atenei Parmensis 2020, 91(4), e2020183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhonacker, F.; Van Loo, E. J.; Gellynck, X.; Verbeke, W. Flemish consumer attitudes towards more sustainable food choices. Appetite 2013, 62, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaspar, M. C. M. P., Celorio-Sardà, R., Comas-Basté, O., Latorre-Moratalla, M. L., Aguilera, M., Llorente-Cabrera, G. A., Puig-Llobet, M., & Vidal-Carou, M. C. Knowledge and perceptions of food sustainability in a Spanish university population. Frontiers in nutrition 2022, 9, 970923. [CrossRef]

- Making our food fit for the future – citizens’ expectations. Special Eurobarometer. Belgium: European Commission. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/publications/making-our-food-fit-future-citizens-expectations_en/ (accessed 5 January 2023).

- Irazusta-Garmendia, A., Orpí, E., Bach-Faig, A., & González Svatetz, C. A. Food Sustainability Knowledge, Attitudes, and Dietary Habits among Students and Professionals of the Health Sciences. Nutrients 2023, 15(9), 2064. [CrossRef]

- Willett, W., Rockström, J., Loken, B., Springmann, M., Lang, T., Vermeulen, S., Garnett, T., Tilman, D., DeClerck, F., Wood, A., Jonell, M., Clark, M., Gordon, L. J., Fanzo, J., Hawkes, C., Zurayk, R., Rivera, J. A., De Vries, W., Majele Sibanda, L., Afshin, A., … Murray, C. J. L. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393(10170), 447–492. [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M., Godfray, H. C. J., Rayner, M., & Scarborough, P. Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. PNAS 2016, 113, 4146 – 4151. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1523119113. [CrossRef]

- Ruini, L. F., Ciati, R., Pratesi, C. A., Marino, M., Principato, L., & Vannuzzi, E. Working toward Healthy and Sustainable Diets: The "Double Pyramid Model" Developed by the Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition to Raise Awareness about the Environmental and Nutritional Impact of Foods. Frontiers in Nutrition 2015, 2, 9. [CrossRef]

- What we eat matters: Health and environmental impacts of diets worldwide. Health and environmental impacts of diets worldwide - Global Nutrition Report. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/reports/2021-global-nutrition-report/health-and-environmental-impacts-of-diets-worldwide/ (accessed 9 May 2022).

- Macdiarmid, J. I., Douglas, F., & Campbell, J. Eating like there’s no tomorrow: Public awareness of the environmental impact of food and reluctance to eat less meat as part of a sustainable diet. Appetite, 2016, 96, 487–493. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26476397/.

- Changing Climate, Changing Diets Pathways to Lower Meat Consumption. Chatham House Report. Available online: https://storage.googleapis.com/planet4-eu-unit-stateless/2018/08/ac718383-ac718383-chhj3820-diet-and-climate-change-18.11.15_web_new.pdf (accessed 11 November 2022).

- Almansour, F. D., Allafi, A. R., & Al-Haifi, A. R. Impact of nutritional knowledge on dietary behaviors of students in Kuwait University. Acta bio-medica:Atenei Parmensis, 2020, 91(4). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33525277/.

- The environmental impact of Food & Seafood. Sustainable Fisheries UW. Available online: https://sustainablefisheries-uw.org/seafood-101/cost-of food/#:~:text=Seafood%20has%20a%20much%20lower,freshwater%20than%20land%2Dbased%20food.&text=In%20addition%20to%20being%20one,gone%20extinct%20due%20to%20fishing/ (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Laird, B., Chan, H. M., Kannan, K., Husain, A., Al-Amiri, H., Dashti, B., Sultan, A., Al-Othman, A., & Al-Mutawa, F. Exposure and risk characterization for dietary methylmercury from seafood consumption in Kuwait. Science Direct 2017, 607-608, 375–380. [CrossRef]

- Guillen, J., Natale, F., Carvalho, N., Casey, J., Hofherr, J., Druon, J. N., Fiore, G., Gibin, M., Zanzi, A., & Martinsohn, J. T. Global seafood consumption footprint. Ambio, 2019, 48(2), 111–122. [CrossRef]

- Water: Thirsty animals, thirsty crops: Heinrich Böll stiftung: Brussels Office - European Union. Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. Available online: https://eu.boell.org/en/2021/09/07/water-thirsty-animals-thirsty-crops/ (accessed 10 May 2022).

- Sánchez-Bravo, P., Chambers, E., 5th, Noguera-Artiaga, L., López-Lluch, D., Chambers, E., 4th, Carbonell-Barrachina, Á. A., & Sendra, E. Consumers’ Attitude towards the Sustainability of Different Food Categories. Foods (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 9(11), 1608. [CrossRef]

- Syed Azhar, S. N. F., Mohammed Akib, N. A., Sibly, S., & Mohd, S. Students’ attitude and perception towards sustainability: The case of Universiti Sains Malaysia. MDPI, 2022, 14, 3925. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/7/3925.

- Afroz, N., & Ilham, Z. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice of university students towards Sustainable Development Goals (sdgs). JISDeP, 2020, 1, 31-44. http://jurnal.pusbindiklatren.bappenas.go.id/lib/jisdep/article/view/12/4.

- Elmi, A., Anderson, A. K., & Albinali, A. S. Comparative study of conventional and organic vegetable produce quality and public perception in Kuwait. View of comparative study of conventional and organic vegetable produce quality and public perception in Kuwait. Kuwait Journal of Science, 2019, 46, 120-127. https://journalskuwait.org/kjs/index.php/KJS/article/view/6760/343.

- Tobler, C., Visschers, V. H., & Siegrist, M. Eating green. Consumers’ willingness to adopt ecological food consumption behaviors. Appetite, 2011, 57(3), 674–682. [CrossRef]

| Categories | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 78 | |

| Male | 22 | |

| Age range (years) | ||

| <20 | 48 | |

| 20-22 | 34 | |

| >22 | 18 | |

| Type of Degree | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 94 | |

| Master’s degree | 6 | |

| Mode of study | ||

| Full-time | 58 | |

| Part-time | 42 | |

| Year of study | ||

| <3rd year | 71 | |

| =>3rd year | 29 | |

| Nationality | ||

| Kuwaiti | 85 | |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 15 | |

| Faculty | ||

| Medical | 18 | |

| Non-medical | 82 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 87 | |

| Married | 11 | |

| Divorced | 1 | |

| Children | ||

| No | 92 | |

| Yes | 8 | |

| Governorate | ||

| Al-Ahmadi | 18 | |

| Capital | 18 | |

| Farwaniya | 24 | |

| Hawali | 15 | |

| Jahra | 10 | |

| Mubarak Al-Kabeer | 12 | |

| Others | 2 | |

| Employment status | ||

| No | 89 | |

| Yes | 12 | |

| Length of Employment | ||

| None | 84 | |

| <=5 years | 10 | |

| >5 years | 5 | |

| Employment sector | ||

| Govt Sector | 9 | |

| Private Sector | 3 | |

| Other | 88 | |

| Income | ||

| None of the above | 42 | |

| <500 KD | 45 | |

| >=500 KD | 13 | |

| BMI | ||

| Non-Obese | 66 | |

| Obese | 34 | |

| Physically active | ||

| No | 36 | |

| Yes | 64 | |

| Physical activity - hrs/week | ||

| <3 hrs/week | 35 | |

| 3-5 hrs/week | 42 | |

| >5 hrs/week | 22 |

| Food Sustainability Related Term | Age Groups (in years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <20 | 20-22 | >22 | Total | p-value | |

| n = 133 | n = 95 | n = 50 | |||

| Ecological footprint | 44.4 | 57.9 | 68.0 | 53.2 | 0.046 |

| Carbon footprint | 42.1 | 53.7 | 56.0 | 48.6 | 0.295 |

| Food sustainability | 30.1 | 42.1 | 44.0 | 36.7 | 0.079 |

| Environmental impact | 69.2 | 74.7 | 84.0 | 73.7 | 0.277 |

| Biodiversity | 33.1 | 44.2 | 48.0 | 39.6 | 0.006 |

| Local food | 72.9 | 81.1 | 84.0 | 77.7 | 0.454 |

| Greenhouse gas emissions | 58.6 | 68.4 | 66.0 | 63.3 | 0.605 |

| Green water–Blue water | 26.3 | 20.0 | 30.0 | 24.8 | 0.546 |

| Attribute | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Low environmental impact | 2.62 | 1.934 |

| Respectful of biodiversity | 2.47 | 1.928 |

| No additives | 1.78 | 1.903 |

| Low processing | 1.98 | 1.947 |

| Few ingredients | 1.72 | 1.744 |

| Organic /ecologic products | 2.88 | 1.884 |

| Plenty of fresh products | 3.53 | 1.806 |

| Diet rich in vegetables | 3.58 | 1.733 |

| Diet typical from own culture | 2.39 | 1.801 |

| Locally produced | 2.79 | 1.757 |

| Affordable | 3.53 | 1.826 |

| Easy to follow | 3.16 | 1.916 |

| Food type | Gender | I don’t know | Negative impact | Positive impact | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetables | Female | 13% | 2% | 85% | 0.658 |

| Male | 10% | 3% | 87% | ||

| Meat and its derivatives | Female | 22% | 15% | 63% | 0.032 |

| Male | 10% | 10% | 80% | ||

| Fish, shellfish, and its derivatives | Female | 21% | 11% | 68% | 0.131 |

| Male | 10% | 11% | 79% | ||

| Milk and dairy | Female | 17% | 17% | 66% | 0.252 |

| Male | 13% | 10% | 77% | ||

| Eggs | Female | 21% | 8% | 71% | 0.082 |

| Male | 15% | 2% | 84% | ||

| Processed food | Female | 16% | 76% | 8% | 0.133 |

| Male | 26% | 64% | 10% | ||

| Carbonated and processed drinks | Female | 13% | 81% | 6% | 0.01 |

| Male | 15% | 67% | 18% |

| Food type | Age group (years) | Don’t know | Negative impact | Positive impact | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetables | <20 | 17.30% | 0.80% | 82.00% | 0.084 |

| 20-22 | 7.40% | 3.20% | 89.50% | ||

| >22 | 8.00% | 4.00% | 88.00% | ||

| Meat and its derivatives | <20 | 24.10% | 9.00% | 66.90% | 0.052 |

| 20-22 | 16.80% | 15.80% | 67.40% | ||

| >22 | 12.00% | 24.00% | 64.00% | ||

| Fish, shellfish,and its derivatives | <20 | 22.60% | 12.80% | 64.70% | 0.169 |

| 20-22 | 16.80% | 6.30% | 76.80% | ||

| >22 | 12.00% | 14.00% | 74.00% | ||

| Milk and dairy | <20 | 21.10% | 15.00% | 63.90% | 0.167 |

| 20-22 | 10.50% | 13.70% | 75.80% | ||

| >22 | 12.00% | 20.00% | 68.00% | ||

| Eggs | <20 | 23.30% | 6.00% | 70.70% | 0.293 |

| 20-22 | 15.80% | 5.30% | 78.90% | ||

| >22 | 16.00% | 12.00% | 72.00% | ||

| Processed food | <20 | 25.60% | 67.70% | 6.80% | 0.027 |

| 20-22 | 11.60% | 76.80% | 11.60% | ||

| >22 | 10.00% | 82.00% | 8.00% | ||

| Carbonated and processed drinks | <20 | 20.30% | 69.90% | 9.80% | 0.016 |

| 20-22 | 6.30% | 85.30% | 8.40% | ||

| >22 | 8.00% | 86.00% | 6.00% |

| Response | 1. Enough water for the planet is granted by the natural cycle of water | 2. Production of meat-based foods require more input of water resources | 3. Production of plant-based foods require more input of water resources | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Total | Gender | Total | Gender | Total | ||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | ||||

| I don’t know | 23% | 20% | 22% | 30% | 34% | 31% | 25% | 33% | 27% |

| Do not agree | 9% | 3% | 8% | 13% | 15% | 13% | 5% | 5% | 5% |

| Agree a little | 15% | 13% | 14% | 13% | 10% | 13% | 11% | 7% | 10% |

| Mostly agree | 21% | 18% | 20% | 19% | 18% | 19% | 16% | 11% | 15% |

| Agree | 21% | 30% | 23% | 18% | 11% | 17% | 24% | 26% | 24% |

| Completely agree | 12% | 16% | 13% | 6% | 11% | 8% | 19% | 18% | 19% |

| Response | To what extent are you willing to pay more money for food and drink products that are produced in a sustainable way? | To what extent are you willing to change your current dietary habits toward more sustainability? |

| Not sure/don’t know | 20.9% | 19.4% |

| Not at all | 4.0% | 4.3% |

| Unwilling | 10.1% | 10.1% |

| Moderately willing | 36.7% | 25.9% |

| Quite willing | 16.9% | 21.9% |

| Willing | 11.5% | 18.3% |

| To what extent are you willing to purchase food or drink that is labelled with a low carbon and water footprint? | To what extent are you willing to reduce consumption of a particular food or drink after knowing that it is producing more environmental impact? | |

| Not sure/don’t know | 30.6% | 22.3% |

| Not at all | 3.6% | 3.6% |

| Unwilling | 13.3% | 10.4% |

| Moderately willing | 21.2% | 25.2% |

| Quite willing | 12.2% | 15.8% |

| Willing | 19.1% | 22.7% |

| Variable | Category | Attitude (DV) | Pearson Chi-square value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (n) | Positive (n) | ||||

| Faculty type | Medical | 10 | 41 | 7.551 | 0.006 |

| Non-medical | 91 | 136 | |||

| Degree level | Bachelor | 95 | 166 | 0.008 | 0.927 |

| Master | 6 | 11 | |||

| Knowledge | Poor | 40 | 73 | 65.78 | <0.001 |

| Good | 137 | 28 | |||

| Year of study | <3rd year | 78 | 119 | 3.112 | 0.078 |

| =>3rd year | 23 | 58 | |||

| Mode of study | Full-time | 53 | 108 | 1.925 | 0.165 |

| Part-time | 48 | 69 | |||

| University accommodation | No | 101 | 175 | 1.15 | 0.284 |

| Yes | 0 | 2 | |||

| Gender | Female | 78 | 139 | 0.064 | 0.801 |

| Male | 23 | 38 | |||

| Age | <20 years old | 58 | 75 | 6.462 | 0.04 |

| 20-22 years old | 26 | 69 | |||

| >22 years old | 17 | 33 | |||

| Nationality | Kuwaiti | 88 | 149 | 0.444 | 0.505 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 13 | 28 | |||

| Governorate | Capital | 33 | 59 | 8.113 | 0.017 |

| Al-Ahmadi | 40 | 44 | |||

| Al-Farwaniya | 28 | 74 | |||

| Marital status | Single | 88 | 155 | 0.334 | 0.846 |

| Married | 11 | 20 | |||

| Divorced | 2 | 2 | |||

| Children | No | 92 | 163 | 0.085 | 0.771 |

| Yes | 9 | 14 | |||

| Employment status | Unemployed | 92 | 154 | 1.053 | 0.305 |

| Employed | 9 | 23 | |||

| None | 87 | 147 | 2.629 | 0.269 | |

| Length of Employment | <=5 years | 7 | 22 | ||

| >5 years | 7 | 8 | |||

| Employment sector | Govt Sector | 7 | 18 | 1.352 | 0.509 |

| Private Sector | 2 | 6 | |||

| Other | 92 | 153 | |||

| Monthly income | None | 54 | 63 | 8.524 | 0.014 |

| <500 KD | 36 | 90 | |||

| >=500 KD | 11 | 24 | |||

| BMI | Non-Obese | 61 | 121 | 2.182 | 0.14 |

| Obese | 40 | 54 | |||

| Physically active | No | 39 | 61 | 0.481 | 0.488 |

| Yes | 62 | 116 | |||

| Physical activity - hrs/week | <3 hrs/week | 37 | 61 | 0.249 | 0.883 |

| 3-5 hrs/week | 43 | 75 | |||

| >5 hrs/week | 21 | 41 | |||

| Independent Variable | B | p-value | OR | 95% C.I.for EXP(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Constant | 0.511 | 0.057 | 1.666 | ||

| Income=None of the above(1) | -0.638 | 0.019 | 0.528 | 0.310 | 0.900 |

| BMI=Non-Obese(1) | 0.645 | 0.022 | 1.906 | 1.099 | 3.307 |

| Governorate=Al-Ahmadi(1) | -0.786 | 0.005 | 0.456 | 0.263 | 0.790 |

| Type_College=Medical(1) | 0.959 | 0.016 | 2.608 | 1.194 | 5.698 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).