Introduction

What about the universality of rights in relation to national laws? Are national laws consistent with the universality of rights? From an intercultural point of view, if we consider the notion of the “singular universal” mentioned by Porcher and Pretceille (1998: 29)1 it refers to the part of universality that is contained in each human being and shared by all. In this sense, the comparisons that can be imagined or made between human beings can only be imagine in order to emphasise local, geographical characteristics and specificities. In fact, gender is a “singular universal” because the question of gender is manifested and repeated in all human societies. As such, it appears as a universal human knot; and the means of its manifestations are language and discourses. However, it also shows and allows us to discuss the paradoxical pitfalls of the idea of universalism that underlies laws in general. From this perspective, it is language that does everything (Mills 2008), as illustrated by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). In fact, laws can be seen as (very) good intentions and texts to promote protection and non-discrimination as well as equality: since it is a matter of considering the universality of human rights, it is also a matter of having laws that reflect an adequate protection of these rights, which – being universal – should be sought by all nations. However, the reality of people’s daily lives is somewhat different, especially when it comes about women and gender, and this will be the main theme of my next points (Andolfatto et al. 2016, Eberhard, Laufer and Meur 2017, Hennette-Vauchez, Pichard, Roman 2014).

Within the global framework of forensic linguistics (Stein, Olsen and Lorz 2000; Mellinkof 1963), my main theoretical framework as a linguist will be Austin’s speech act theory (Austin 1962), and after him, performativity theory (as first developed by Butler 2004, 1997) all linked to the theoretical framework of French discourse analysis – which takes into account the historical diachronic context to better understand a specific situation and context. It is also from this perspective that I refer in particular to laws as discourses constituting “frameworks of social memory” (Halbwachs 1997). Furthermore, because the laws apply whatever happens, I also look at the overall context and definition of what verbal violence is for the people who experience it from the perspective of a sociolinguistics of discourse (Moise, Romain, Auger, Fracchiolla 2008 and since then on this topic) in gender studies. My recent research thus led me to be interested in the linguistics and the discursive manifestations of what many have considered to be details, but which I myself call symptoms of discrimination of women’s status, function, social roles as gendered roles in everyday life (on Language discrimination processes, see Stollznow 2017).

Among these symptoms I count, for example, the resistance of French administrations to removing the title “Miss” from forms; or how schools, universities, and even government institutions resist the feminisation of roles and titles, or how parents can be something other than just "father" and "mother" (since there are only two parents who can both be men or women) when it comes to obtaining identity documents (identity card or passport). For these reasons, my research is also linked to legal consciousness studies (Pélisse 2005):

“As Patricia Ewick and Susan Silbey, two scholars who have shaped the LCS, argue, "the ways in which law is experienced and understood by ordinary citizens, insofar as they choose to invoke, avoid, or resist the law, is an essential part of the life of the law. The studies therefore focus on the concrete practices of daily life in which legal rules are used and perceived (or not) as constitutive elements of reality, as opposed to an instrumental approach to law, which conceives of the latter as an afterthought and external to the social practices it regulates.”

(my translation)

1. Living one’s gender: a social role

Indeed, as they are used on a daily basis, even more than once a day, the issue of addressing and naming can be harassing for women, as it can be for transgender people when they are misgendered in the way they are named or addressed (Mr instead of Mrs etc.) (Nanda 1989, Mills 2008). Laws also become an issue when they regulate (or fail to regulate) women’s bodies, which is usually the case when it comes to childbearing and defining the right to abortion in different parts of the world; or when they are used to advertise products; or when they stigmatise the female body as inherently sexual (as is the case of films shown on international flights from Muslim countries, where women’s breasts or nudity are blurred to black).

In this context of observing what a law really means for citizens in their daily lives, the French law "Marriage for all", passed on 17 May 2013, legalising same-sex marriage, was particularly interesting because it highlighted certain problems faced by women in heterosexual marriages. It has also highlighted, year after year over the last decade, some of the ways in which laws can prove to be discriminatory against women. In particular, this law brings into play the question of control over women’s bodies as (future) mothers, as well as representations of motherhood. What does it mean to be a mother in France in the 2020s? It also allows us to rethink the notion of ‘adoption’ and the biological dimension associated with the status of mother – as opposed to non-mother (or childless woman); father; or non-biological mother or father in the case of a family with two fathers.

The comparison with India also shows that, on the one hand, there are laws and, on the other, there is the practice of applying and interpreting them; and that, in each country, the variable of adaptation is the reality of people’s daily lives.

In England and India, common law is the rule: common law is a ’body of law’ based on court decisions rather than codes or statutes. The difference between common law and civil law is that common law is a system historically focused on relationships between people (for example, multiple property rights may overlap), whereas civil law is based on the primacy and absolute nature of rights – as it is in France.

So even though the common law applies, there are different sets and levels of rules that apply in an Indian person’s daily life: caste, regional and federal laws can interfere at certain levels (Agnes 2001, Mukhopadhyay 1998, Dube 2001).

Marriage in India is primarily governed by personal laws based on an individual’s religion, and most personal laws do not recognise same-sex marriages. The Special Marriage Act, a secular law that allows inter-faith and inter-caste marriages, also does not explicitly allow same-sex marriages. India does not recognise registered marriages or civil unions for same-sex couples, although same-sex couples can enjoy rights and benefits as a resident couple (analogous to cohabitation) under a judgment of the Supreme Court of India in August 2022

In all countries, the question of childbearing and parenthood is a major gender issue, because it is a major human issue and, in fact, at the centre of life, linked to one’s social position in the world, society and inheritance (descent, transmission of names and property, the child’s place in society according to its sex…).

And it is also the gateway to control over women’s bodies, because it is directly linked to social representations of parenthood, also in its political, social and economic connections and meanings. What does it mean to be a mother? To be a father? To have a child? And what difference does it make if the child is a boy or a girl? What does it mean to be a woman or a man, transsexual, homosexual or cisgender? From there, and depending on the place of birth, the decision about one’s own body is very different. In France, before the Neuwirth law (28/12/1967) which authorised contraception, contraception was often confused with abortion: preventing fertilisation was associated with interrupting the development of the foetus2. Then, the Veil Law (01/17/1975) legalised the right to abortion in France, with the voluntary interruption of procreation (previously a punishable offence). Looking in parallel at the evolution of (civil) marriage in France, the PACS law (15/11/1999) gave recognition to other couple statuses by the simple fact that people decided to live together by contract, and also allowed the recognition of cohabitation as a status that could be easily declared. Finally, the law on marriage "for all" - i.e., the recognition of homosexual marriages - also gave women the right to adopt their own child as a social parent after marriage, under very specific conditions that had to be proven and confirmed by the judge (17 May 2013). This law was actually amended in August 2021 and allows for early recognition by the social mother, as long as proof of the absence of the father is provided (certificate of insemination by an anonymous donor) (XXXX 2021 Alicante; Brunet et al. 2023).

2. What does gay marriage in France teach us about discrimination?

2.1. Methodology and corpus’ presentation

Same-sex marriage was seen as a victory for equality in France. However, the law itself is based on a certain kind of discrimination, because it has created a second type of marriage, which is fundamentally different from a normal marriage in terms of creating a family, which is supposed to be the main project of marriage (Fine and Martial 2010). The fact that lesbians can marry has also highlighted certain discriminations linked to the status of the married woman as such; these discriminations have been felt all the more by these women because they are lesbians. Among these, the mismatching of their surnames that was automatically made by banks and other administrations highlighted the abusive practice to name any married woman with only her husband’s name (in our case, each wife was nominated by the other wife’s surname, thus creating an absurd situation). The discrimination experienced mainly concerns the identity of the person, and in particular the question of the address, the way of being named, as a married woman, as a mother, as an individual; the transmission of the name (XXXX 2018) and above all the recognition of the non-biological mother as a full mother, through marriage (Théry 2016, Gross 2013, Stambolis-Ruhstorfer and Descoutures 2020, Brunet 2015). In fact, one of the recurring practices to guarantee a semblance of at least symbolic recognition is for the non-biological mothers to declare their child’s birth at the town hall: “"So it was I who went to declare the birth at the town hall, so that I would appear as a third declarant, but in fact it was the only mention of me that existed before the adoption" (9P2) (XXXX 2017). This ensures them to see their name appear on their child’s birth certificate before adoption and to therefore also be able to prove their presence and commitment as a mother throughout the process of the child’s birth, a process that a police investigation verifies during the adoption application.

My corpus of studies consists of thirty-two interviews, lasting between thirty minutes and an hour, that I conducted between 2016 and 2022 with one or sometimes both mothers of lesbian families. In order to maintain anonymity, the interviews have been randomized from 1 to 32. The P1 label always concerns the mother who speaks on behalf of the couple. In the rare cases where both mothers participated in the interview, the allocation between P1 and P2 is also randomized based on who speaks first. Thus, the notation 9P2 means that this is interview number 9, and that it is the mother who spoke second at the start of the interview who speaks here. The transcriptions have been cleaned of all the marks of orality in order to make them more readable – hence the notations ‘(...)’. The data processing being for now of a qualitative type, based on selected excerpts relevant for this publication, it therefore did not require full transcription of the interviews.

The lesbian families in my corpus are defined as two mothers with at least one child who have married in order to have their joint motherhood legally recognised for the child or children. The general framework of the 2013 law is that it authorises the adoption of the spouse’s child (identical to heterosexual marriage) under certain conditions of educational recognition of the children. In this process of adopting their partner’s child, women must prove that their children have no father and that they have been involved with the children since the beginning of the project (Guermonprez 2018). The adoption process confers the right to change one’s name, to choose a surname and, at a symbolic level, to register the child in the two lines of its two mothers at the same time.

2.2. Another type of forced marriage

What the analysis of the corpus reveals, on the one hand, is the violence that results from the shortcomings of this law, insofar as these shortcomings create situations of discrimination, while this law, in particular, aimed to include homosexuals in a system that ignored them. In fact, the main of these discriminations is that lesbian families were obliged to get married in order to seek "protection" for their families and to be recognised as legitimate, even though they had no particular intention of getting married:

10P1: "that’s the reason why we got married, in fact (...) it’s the only reason because I knew 10P2 wanted to be pregnant and I told her (...) OK, (...) on the other hand, (...) it’s not the same thing. (...) on the other hand, let me warn you, we don’t have children, we don’t even consider having a procedure if we’re not married, just because in my head, in fact, that was really the thing that guaranteed legitimation”

The argument of having no choice but to get married for the sake of the whole family is repeated in almost all the interviews I have collected over these years. It is also very clear for the parents of interview number eight:

8P1: "We didn’t have a plan to get married, no (...) we lived all these years without getting married (...) afterwards (...) I think that when you get older, apart from the question (of the child), you also ask yourself other questions about the protection of the other; so maybe we would have got married for other reasons, like protection, inheritance, or I don’t know what to imagine (...) we never talked about it, but personally (...) I never rocked in my chair. (…) I have never been caught up in the illusion of "the princess who marries the prince" (...) because there are women who expect marriage as a kind of realisation, as a kind of result (...) so we had a very simple wedding, we had the witnesses and we had a great restaurant, it took twenty minutes, here is the end of the ceremony (...) again it is a very simple ceremony. ... once again it is a purely administrative process for me, in any case at that time (departure abroad) (...) as a matter of fact I do not carry any romanticism on the notion of marriage".

As is clear to the parents of interview number nine:

9P2: "So there were several things, so there was already the fact that the child had to be over 6 months old3, so that was the first thing. Marriage has never been a goal or a wish for us, nor to get a PACS. We have a connection to it that is not necessarily ... well, we really got married so that I could adopt (the child’s name). But I don’t think we would ever have got married or had a civil partnership otherwise... for reasons of, I was going to say, conviction”.

Another reason for marrying soon after the law was political anxiety, because the law was difficult to pass and you never know what will happen next. This couple (interview number seven) felt they had to do it immediately, just after they had contracted a civil union (PACS), for which they had a very big party:

7P1: "We got married in July 2014 (...) more than a year after the law (...). I was the one who insisted to 7P2 that she would do it, because I was afraid that we would have a window of a little bit too short and that after all this... we didn’t know if Hollande4 would be maintained and that if we had Marine Le Pen5, maybe... (...) that she threatened to annul the marriage for everyone (...) and that’s why I kept saying to 7P2: "we have to start, we have to start".

And then 7P1 adds:

"and then hey, it was still necessary to get married, even if it was a formality, it is not completely a formality. So, we finally started in July 2014, so we got married, we didn’t have a big party again, (...) well we still marked the occasion, but we didn’t make all the fuss, we just had a little party at home".

Again, the implicit reference is to the need to get married in order to protect their family (they had two children by then). An interviewee described her case where although separated for many years, the two mothers decided nevertheless to get married in order to do the adoption process for their teenager children’s sake, and then have a divorce. More, many of these mothers, who had to pay between two hundred and two thousand euros for the adoption process, also had to pay when deciding to get a divorce, which adds a pecuniary dimension to the discrimination.

So, in a way, we could speak here of the institutional violence that forced women to marry in order to be recognised as the other parent of the children they had, the child they had helped to bring into the world because they too wanted to be mothers (Gross 2013).

When talking about violence, the first thing that counts is the violence that is felt, which is quite obvious here in the ways it emerges from the speeches. Before finally being able to adopt their children, non-biological mothers lived (and still live in some cases) in constant stress linked to all kinds of possible life threats. What would happen if the biological mother died? if an emergency life-saving decision had to be made for their child that they cannot legally make? If she herself dies and cannot pass on her assets, nor her name, to her child? This bastard status (literally and figuratively) constitutes a precariousness of the emotional and parental bond with the child, who needs the security conferred on him by the legal presence of his two parents, at his side, from his birth. Thus, even if they never wanted to get married, these women are obliged to do so to protect their children, especially since the second mother has no legally recognised relationship with the child until the adoption is finalised (which takes 6 to 18 months, depending on the families, judges and courts where they live). In fact, if the biological mother were to die before the adoption was finalised, she would have absolutely no right to keep her children with her, and even the possibility of seeing her children again would depend entirely on the wishes of the biological mother’s family.

In terms of parental responsibility, this procedure, which was and still is imposed only on lesbian families, is discriminatory but necessary for them as parents. It shows that when it comes to protecting their children, they put their children first, whatever their own beliefs may be. Working on this issue has also taught me that whatever the big equality discourses, the acculturation of discrimination is regular when it comes to women and the family (Stambolis-Ruhstorfer and Descoutures 2020). Extending my research on this topic to India, a totally different country, has been a way to push further the theorizing of this fact.

3. What does it mean to be born a woman in India?

According to the United Nations report of April 2023, India will become the most populous country in the world with a total population of 1,425,775,8506.

Population control has been a public policy concern in India for some time7. In fact, a population control bill was introduced in Parliament in 2019, but later withdrawn in 2022. However, another issue to consider in this context is India’s existing laws on reproductive health and contraception. The Supreme Court of India in the case of Suchita Srivastava and anr v/s Chandigarh Administration said: "It is important to recognise that reproductive choice can be exercised for procreation as well as for abstinence. The crucial consideration is that a woman’s right to privacy, dignity and physical integrity should be respected. This means that there should be no restrictions whatsoever on the exercise of reproductive choice, such as a woman’s right to refuse to participate in sexual activity or to insist on the use of contraceptive methods".

In India, it is the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare who regulates contraceptive services under the National Family Planning Welfare Program8. Contraception (that is birth control) is promoted and made available free of charge. The K.S. Puttaswamy judgement (26/10/2018)9 recognised the constitutional right of women to make reproductive choices as part of the personal liberty guaranteed under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution10.

However, Indian marriage reinforces gender roles to the extent that women ’change’ families and become the ’property’ of their husband’s family, both symbolically and materially (Chatterjee and Jeganathan 2000, Agnes 2001). In fact, today the practice of dowry has been reversed and it is the bride’s parents who have to give a large sum of money to the groom’s family for him to marry their daughter. This then leads to a lot of abuse and crimes against the woman (including harassment, abuse and even death) and a lot of pressure in general.

When a woman marries, she also becomes the child of her husband’s parents and has to take care of them as if they were her own parents. For this reason, a little boy is often valued more: the child’s education and investment will not be lost to another family when he marries, but the boy will stay with his parents and care for them with his wife after marriage. It is therefore important for parents to know that they will be looked after when they are older. Of course, there are now Indian women who are independent and active enough to look after their elderly parents, but this is not yet the norm11.

In the rural state of Rajasthan, female infanticide (also known as gender-based infanticide) is still a common practice. In fact, it is still a deeply disturbing issue in some parts of India (Saravanan 2002, Dewan and Kahn 2009). This practice involves the deliberate killing of female infants or foetuses due to cultural, social or economic preferences for male children. As I explained, the preference for male children is rooted in cultural and societal factors, including dowry practices, inheritance norms and the perception that male heirs are essential to carry on the family name (Ahlawat 2013). In particular, the dowry system, whereby the bride’s family is expected to make significant gifts or financial contributions to the groom’s family, can place an economic burden on the family with daughters. This in turn contributes to a preference for male children12.

Sons are often seen as the primary breadwinners and providers for the family, especially in rural agricultural communities. The belief that male offspring will contribute more to the family income can lead to the devaluation of female children. Deep-rooted patriarchal norms and the desire for male heirs to carry on the family name and property also contribute to the preference for male children13. In addition, intersectionality in India includes caste parameters that do not exist in France14 (Agnes 2001). And, like other forms of discrimination, it is written off as unconstitutional15. This is also the reason why there is still a demand and business for arranged marriage, although it is often done in a smoother and more modern manner – as illustrated in the three seasons Netflix Series Indian Matchmaking, October 2023.

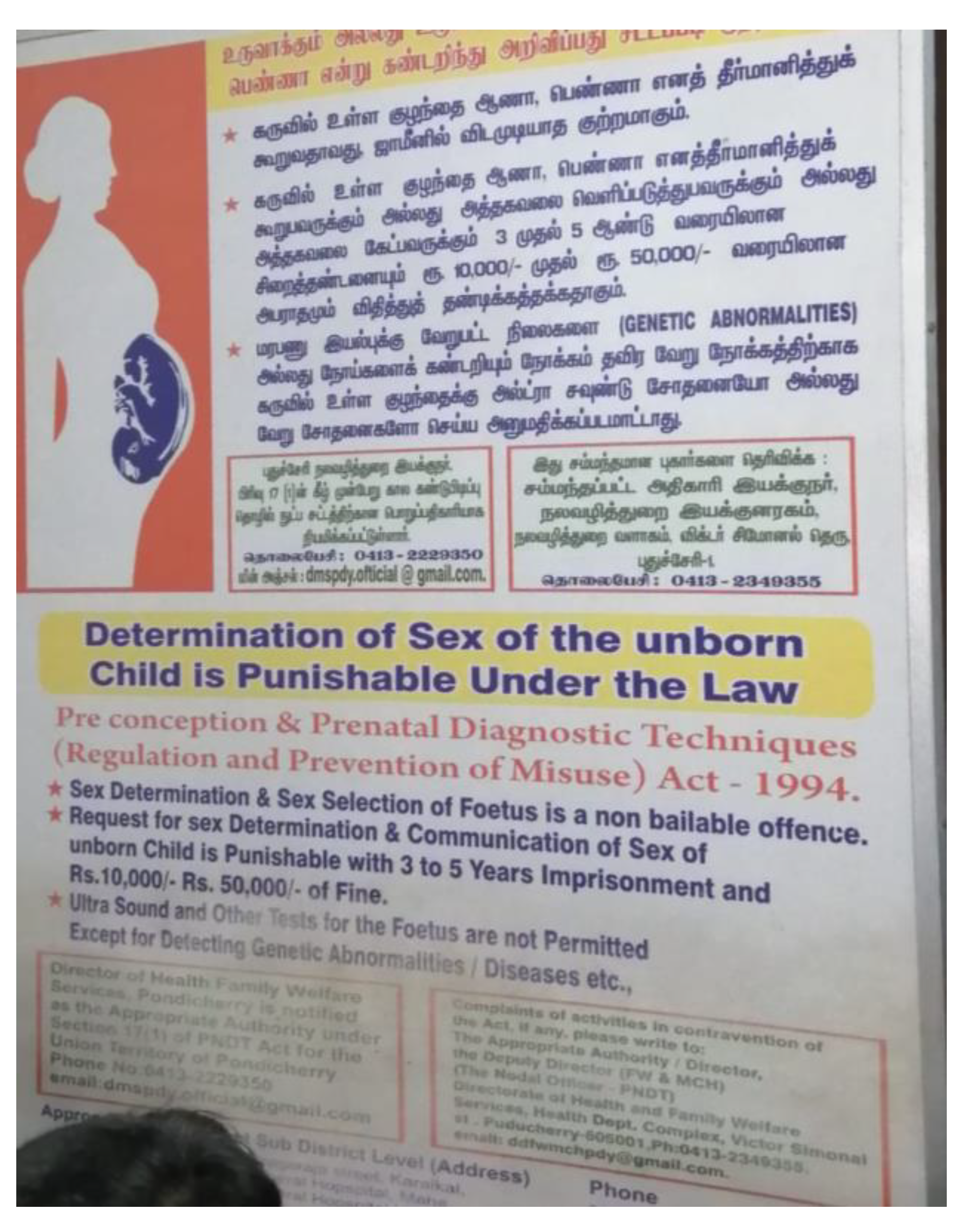

The following photo (photo 1) was taken (by me) at the entrance to the New Medical Centre in Pondicherry, Tamil Nadu, India, on 18 August 2022. The picture shows a shadow of a pregnant woman with a focus of the foetus in her womb, in blue. The text is written both in Tamil and in English and says:

“Determination of Sex of the unborn Child is Punishable Under the Law. Pre-conception and Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse – Act 1994): Sex Determination and Sex Selection of foetus is a non bailable offence. Request for sex Determination and Communication of Sex of unborn Child is Punishable with 3 to 5 Years Imprisonment and 10000 to 50000 rupees of fine. Ultra Sound and Other Tests for the Foetus are not Permitted except for Detecting Genetic Abnormalities, Diseases, etc”.

This poster highlights and illustrates both this whole issue and what I am trying to define when I speak of the "symptoms" of women’s social status/function/role in society in their ordinary lives:

Figure 1.

Waiting room/entrance – New Medical Centre, Pondicherry, Tamil Nadu, India, 18/08/2022.

Figure 1.

Waiting room/entrance – New Medical Centre, Pondicherry, Tamil Nadu, India, 18/08/2022.

While in Europe it is a normal and regular practice to know about prenatal sexuality from the third month (from the time when the baby is supposed to be safer to be carried until the end), in India it is forbidden and punishable on grounds of gender discrimination. However, the law does not completely prevent it, and in this configuration, there is a risk that if a baby girl is announced, the groom’s family (the in-laws and often the man himself) will put pressure on the pregnant mother to undergo an illegal and dangerous abortion after three months of pregnancy.

4. What about same-sex couples in India?

In 2018, the Indian Supreme Court partially decriminalised homosexuality by striking down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which criminalised consensual same-sex relations. The court ruled that consensual homosexual acts between adults are not illegal. However, the context of the vote was very different from the "civil rights" and individual freedom of life that come with it in France or England, for example.

In fact, Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code was introduced in 1861 during the British rule of India and was modelled on the Buggery Act of 1533. It made sexual acts "against the order of nature" illegal. On 6 September 2018, the Supreme Court of India ruled that the application of Section 377 to consensual same-sex relations between adults was unconstitutional, "irrational, indefensible and manifestly arbitrary". In fact, the main argument of the lawyers defending decriminalisation was that the penal law (i.e., Section 377) was primarily a colonial law that discriminated against Indians. They insisted on the double discrimination inherent in this article, which leads to the conclusion that the problem does not lie with same-sex couples, but with the condemnation of Indians on the basis of an imported colonial law that persists despite independence.

Arundhaty Katju and Menaka Guruswamy

16, both Brahmin lawyers, came forward as a lesbian couple to defend decriminalisation

17. In fact, Katju’s two main arguments were, firstly, that this was not an issue (the legalisation of gay rights) that only affected Western countries, but also directly affected India in terms of its history, its culture:

"Malaysians and Sri Lankans are looking at how they can use India’s ruling to overturn anti-gay laws in their own countries" - "imported" by colonialism, especially the British. (...) Our government must realise that these are not our laws, that this has never been our culture (...) Independence and decolonisation must surely mean more freedom...".

Of course, Hindu culture is at first glance that of an open and gender-fluid country, given Hindu deities and the constitutional existence of a third gender18 (Shah 2012). After India’s decriminalisation, other movements emerged in Kenya, Botswana, etc., based on the same anti-colonial argument.

However, the decriminalisation of homosexuality did not automatically legalise same-sex marriage in India.

More recently, on 17 October 2023, the Supreme Court of India rejected the petitions of 21 petitioners, including same-sex couples, trans people and associations. The judges said they did not have the power to make such a decision and, as the government wanted, handed the responsibility over to Parliament. However, there has been notable progress on marriage for couples where one member is transgender. The Supreme Court has ruled that there is no obstacle to the marriage of transsexuals, provided they identify as "man" and "woman" respectively (says Sophie Landrin from New Delhi, India, correspondent for Le Monde, 19 October 2023)19.

Although it does not recognise same-sex marriages or civil unions, the vast majority of heterosexual marriages are not registered with the government and customary marriage remains the dominant form of marriage. Hindu priests perform same-sex marriage ceremonies in India and abroad, and hundreds of same-sex marriages between Hindus in India have been reported in customary marriages since at least the late 1980s. As pointed out in the introduction, India does not have a single law on marriage, and each citizen has the right to choose which law applies to them based on their religious community. Although marriage is regulated at the federal level, the existence of multiple marriage laws complicates the issue.

Conclusion

In conclusion, what can we say about the existence of potentially discriminatory laws?

Some people have in common a certain kind of social insecurity due to the gaps in the laws (which structure societies), because these laws don’t cover all the areas of a person’s life and needs (love, work, having a family) to be fulfilled in a safe environment. In fact, this seems to affect all individuals who are not considered male, masculine, with all the attributes that are socially expressed.

The question also seems to arise in relation to the status of transgender people - and the naming/gender issue involved - and in relation to what it means to be a lesbian in India, or simply a woman who wants to have a family.

The evolution of Indian legislation and parliamentary debate on the rights of LGBTQ+ people in India on the base that “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure by law” (Article 21, Indian Constitution) also shows that despite decriminalisation, their status remains precarious.

In fact, despite the various judgments putting forward Article 21 to protect minorities – including women – in different ways, the constitutional recognition of Hijras as a third gender20, transgender people face poor social and professional integration and their status as regular citizens remains extremely precarious. Most of the time, male to female transsexuals especially are ostracised, have difficulty finding work and are often forced to beg or prostitute themselves, while paradoxically also being feared by the population, which recognises that they have a certain power (for example, they are given money so as not to risk their curse) (Nanda 1989)21.

Although constitutional laws exist to protect their rights, their application in everyday life remains problematic, and the feeling of having an illegitimate status despite the law persists. For these people, the norm is still to live in an intermediate zone between rights and non-rights, where the sense of violence is very present.

The fact is that the laws we have been debating about are not based on the union of people as people, but on the sex and sexuality of people - so they are de facto discriminatory, creating a double standard instead of equal treatment. In fact, the laws that allow the union of two people are based on the paradigm of differentiation whereas if they emphasized the paradigm of diversity, it would bring more coherence between the law and people’s everyday life.

Although in France, as in India, gender discrimination is generally criminalised by law, it nevertheless manifests itself in different ways on a daily basis. The testimony of French lesbian mothers shows this: they have won legal recognition, but it remains very partial. The examples cited in this publication all concern the maternal body. Moreover, they also concern the potential matriarchal body, in the sense that women could find themselves endowed with a communicable power that has been denied to them for centuries, and in a relatively universal way in the history of humanity.

This shows that the symbolic constitutes a site of social realisation. According to the theory of speech acts and the performativity of address (Austin 1962, Butler 1997), the social is created with, in and through the symbolic.

Addressing or naming someone in a certain way (mother, Miss or Mrs, transgender, Hijras…) defines both social places and roles in a dialogical relationship; and simultaneously assigns and constructs identities in synchrony, but also, as the question of the transmission of surnames carried and given to children shows, in diachrony to be only their fathers’. Names are thus transmitted across generations and according to iterative processes of use which making women disappear, also end up having legal value in the minds of individuals - which ties in with the question of representations.

Funding

This research was funded by the CNRS for the Indian part, with the denomination “Dispositif exceptionnel MESRI - mobilité internationale pour personnels accueillis en délégation au CNRS- INSHS”.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study with the commitment to respect their anonymity – which therefore prevents the publication of the complete interviews.

Acknowledgments

Blandine Ripert, Director of the French Institute of Pondicherry, India, UMIFRE 21 (CNRS-MEAE) - UAR3330 "Savoirs et Mondes Indiens"in 2022, and to Delphine Thivet, then Head of the Social Sciences Department, French Institute of Pondicherry, On leave from Centre Émile Durkheim, Comparative Political Science and Sociology – UMR 5116 (CNRS, Sciences Po Bordeaux and Bordeaux University).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Notes

| 1 |

« Le concept « d’universel singulier », forgé d’abord par Hegel pour exprimer l’idée que, dans un individu particulier, l’universel pouvait être tout entier exprimé, a été repris par Sartre, dans son analyse de Flaubert trouvant en celui-ci à la fois la personne Gustave, incomparable à toute autre, et le porteur de l’ensemble du monde (…) L’éthique nous paraît être légitimement classable parmi les universels-singuliers, c’est-à-dire parmi les réalités présentes partout (universel) mais que chaque société (singulier), et même chaque personne interprète à la façon, selon sa propre grille et son interprétation spécifique » (p.29). |

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

In order to launch the adoption process. |

| 4 |

He was the French President in 2013. |

| 5 |

She is and has been for the past decade the leader of the French far right. |

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

Under The Family Planning Policy, the Government of India encourages couples to adopt the use of contraceptives. Contraceptives are provided free of charge in all Sub-centers, Primary Health Centers (PHCs), Community Health Centre (CHCs) and Rural Family Welfare Centers, District Hospitals, etc. throughout the country. |

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

“Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.), a retired judge of the Madras High Court, challenged the constitutional validity of the Aadhaar scheme. He argued that the scheme violated the right to privacy. A three-judge bench held that a larger bench should determine whether the Constitution of India guarantees a right to privacy. A nine-judge bench decided this case. The Court held that privacy is an attribute of human dignity. The right to privacy safeguards one’s freedom to make personal choices and control significant aspects of their life. In addition, it noted that personal intimacies (marriage, procreation and family), including sexual orientation, are at the core of an individual’s dignity. |

| 11 |

And when it happens, they often end up staying single and sacryfying their own personal life to fill in this role of ‘head’ and main money provider of the family. |

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

Further, the Court described discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation as “deeply offensive to dignity and self-worth”. It noted that the right to privacy was at the intersection of Articles 15 and 21 of the constitution, by referring to its decision in NALSA which grants the right to self-recognition of gender. It stated that the right to privacy was an expression of individual autonomy, dignity, and identity. Therefore, the right to privacy and sexual orientation is at the core of the right to equality, non-discrimination and life.

The Court held that the identity of all individuals must be protected without discrimination because sexual orientation is an essential component of one’s identity.

The Court observed that the right to privacy is primarily derived from Article 21. However, it is also supplemented by the values enshrined in other fundamental rights. Therefore, it advocated for a holistic view of fundamental rights.

|

| 14 |

The caste system in India is a social hierarchy that historically has divided people into hierarchical groups based on their occupation, social status, and hereditary factors. It is often associated with the Vedic period (1500–500 BCE). The Vedas, the oldest sacred texts of Hinduism, contain references to the varna system, which later evolved into the caste system. Initially, the system was more flexible, with people categorized into four main varnas (classes) based on their occupation: Brahmins (priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaishyas (merchants and farmers), and Shudras (laborers and service providers). Over time, this system became more rigid and stratified, leading to the emergence of numerous jatis (sub-castes) based on various factors like region, language, and specific occupations. The caste system also incorporated elements of social hierarchy and purity-pollution concepts. Traditionally, each caste had specific occupations associated with it, and individuals were expected to follow the occupation of their birth and marriages were often restricted within one’s own caste to maintain social purity. While the Indian Constitution prohibits discrimination based on caste and promotes equality, the caste system’s influence persists in some aspects of Indian society. Affirmative action policies, known as reservations, have been implemented to address historical disadvantages faced by certain castes, particularly Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs). |

| 15 |

Part III of the Indian Constitution describes: Fundamental Rights – 16. (2) No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth, residence or any of them, be ineligible for, or discriminated against in respect of, any employment or office under the State. (The Constitution of India, p. 8). Part III, Fundamental Rights, 15. « Prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth.—(1) The State shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them. (2) No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them, be subject to any disability, liability, restriction or condition with regard to—" (The Constitution of India, 2023, p.6). |

| 16 |

|

| 17 |

|

| 18 |

|

| 19 |

|

| 20 |

The court held that all transgender persons are entitled to fundamental rights under Article 14 (Equality), Article 15 (Non-Discrimination), Article 16 (Equal Opportunity in Public Employment), Article 19(1)(a) (Right to Free Speech) and Article 21 (Right to Life) of the Indian Constitution. Also see the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill, 2016 ( https://prsindia.org/billtrack/the-transgender-persons-protection-of-rights-bill-2016). |

| 21 |

When in India and thanks to the network of researchers, I was able to speak with one of them, J., who frequents the French-speaking community. In order to interview her, I covered her travelling expenses. At the restaurant I usually went to near the French Institute of Pondicherry, I was able to see for myself the curious, surprised and, above all, disconcerted looks of the waiters. I was also fortunate to be able to attend the Koovagam transgender festival in April, in Tamil Nadu, where transgender people from all parts of India normally go every year or two. The Hindu religious ritual performed in Koovagam was very usefull to better understand an unwritten part of their culture. |

References

- Agnes, Flavia. Law and Gender Inequality: The Politics of Women’s Rights in India; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlawat, Neerja. Dispensable Daughters and Indispensable Sons: Discrete Family Choices. Social Change 2013, 43, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andolfatto, Dominique; Bugnon, Caroline; Dechâtre, Laurent; Docaj, Denisa; Donier, Virginie; Droin, Nathalie, et al.; et al. Le principe de non-discrimination: l’analyse des discours. [Rapport de recherche] Mission de recherche Droit et Justice. Credespo – Université de Bourgogne. Convention n°214.04.03.21. 2016; Available online: http://www.gip-recherche-justice.fr/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/R.F.214.04.03.21-1.pdf.

- Auger Nathalie, Moïse Claudine; Béatrice, Fracchiolla; Schultz-Romain, Christina. De la violence verbale: pour une sociolinguistique des discours et des interactions. Actes du Congrès Mondial de Linguistique Française; Cité Universitaire. Paper n° 074: Paris, 2008; Volume 074, pp. 630–642, http://www.linguistiquefrancaise.org/articles/cmlf/abs/2008/01/cmlf08140/cmlf08140.html. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, John-Langshaw. How to do Things with Words; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Brunet, Laurence. Les atermoiements du droit français dans la reconnaissance des familles formées par des couples de femmes. Enfances Familles Générations 2015, 23, 91–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, Laurence; Carayon, Lisa; Marguet, Laurie; Mesnil, Marie. Dégenrer le droit à la filiation. Paper presented at the International Conference No(s) futur(s), Toulouse, Université Le Mirail, July 4–7; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Judith. Undoing Gender; Routledge: New York and London, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Judith. Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative; Routledge: New-York, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, Partha; (eds.), Pradeep Jeganathan. Community, Gender and Violence; Permanent black: New Delhi, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dewan, B.S.; Khan, A.M. Socio-cultural determinants of female foeticide. Social Change 2009, 39, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, Leela. Anthropological explorations in gender: Intersecting fields. New Delhi. Sage Publications. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard, Mireille; Laufer, Jacqueline; (ed.), Dominique Meurs; et al. Genre et discriminations; iXe: Paris, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hennette-Vauchez, Stéphanie; Pichard, Marc; (ed.), Diane Roman. La loi & le genre: études critiques de droit français; CNRS: Paris, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Agnès; Martial, Agnès. Vers une naturalisation de la filiation? Genèses 2010, 1, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, Agnès; Martial, Agnès. Performativité des constructions identitaires: Mariage pour tous, nom, adresse et filiation. Le Discours et la Langue Revue de linguistique française et d’analyse du discours, Les observables en analyse de discours - Numéro offert à Catherine Kerbrat-Orecchioni 2017, 9, 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Agnès; Martial, Agnès. Se dire, être dit, et devenir. La question linguistique de l’adresse aux femmes aux carrefours de la loi. 5e Colloque annuel R2DIP Analyse du discours et institutions sociales: l’expertise discursive dans les domaines de la santé et de la justice. Paper presented at the Réseau de recherche des discours institutionnels et politiques (R2DIP) Conference, University of Cergy Pontoise, Cergy, France., Dec 2018. ⟨hal-01989657⟩. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Agnès; Martial, Agnès. When Laws discriminate instead of introducing more equality: the case of the "Mariage pour tous" law. 5th International Language and Law Conference, University of Alicante (ILLA), Sep 2021, Alicante, Spain. ⟨halshs-03338992⟩. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Agnès and Agnès Martial. Gender in Laws. Paper presented at the AILA Conference, Lyon, July 17–21.

- Fine, Agnès; Martial, Agnès. When law deals with Gender. Paper presented at the ILLA Conference, Cracow, 19–22 September; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, Martine. Ouvrir l’accès à l’AMP pour les couples de femmes? In Mariage de même sexe et filiation; Edited by Irène Théry; Éditions de l’EHESS: Paris, 2013; pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Guermonprez, Mathilde. L’autre mère. Documentary, Arte Radio, 31 mn. 2018; Available online: https://www.arteradio.com/son/61659148/l_autre_mere.

- Mellinkof, David. The Language of the Law; Little, Brown and company: New York, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, Sarah. Language and Sexism; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, Maitrayee. Legally Dispossessed: Gender, Identity and the process of Law; Bhatkal and Sen: Calcutta, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda, Serena. Neither Man nor Woman. The Hijras of India; Modern anthropology library: Belmont USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Pélisse, Jérôme. A-t-on conscience du droit ? Autour des Legal Consciousness Studies. Genèses, Sciences sociales et histoire, Belin 2005, 2, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcher Louis and Martine Abdallah-Pretceille. Ethique de la diversité et éducation; l’éducateur, PUF: Paris, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Saravanan, Sheela. Female Infanticide in India: A review of literature. Social Change 2002, 32, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, Irène. Mariage et filiation pour tous. Une métamorphose inachevée. Le Seuil, collection La République des Idées: Paris, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stambolis-Ruhstorfer, Michael; Descoutures, Virginie. French Lesbian Parents Confront the Obligation to Marry in order to Establish Kinship. International Social Science Journal 2020. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/issj.12241. [CrossRef]

- Shah, Shalini. The Making of Womanhood. Gender Relations in the Mahaabhaarata; Manohar: New Delhi, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Dieter, Frances Olsen and Alexander Lorz. Law and Language: Theory and Society; Düsseldorf University Press: Düsseldorf, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stollznow, Karen. The language of Discrimination. Lincom Studies in Semantica. 2017. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).