Submitted:

08 December 2023

Posted:

11 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method of Review

| S. No | Topics | Details | References |

| 1 | Post earthquake performance of Buildings | Earthquake induced loss of functionality in buildings. Damage assessment for critical infrastructure. Safety index at the Life safety performance level. Floor response spectra using direct displacement-based design procedure. composite column for older buildings. Effects on infrastructure near the fault line against the quality of material used and other factors. Review on BIM applications and O&M practices. | [1,2,3,6,11,13,16,21,42,47,48,59,62,69] |

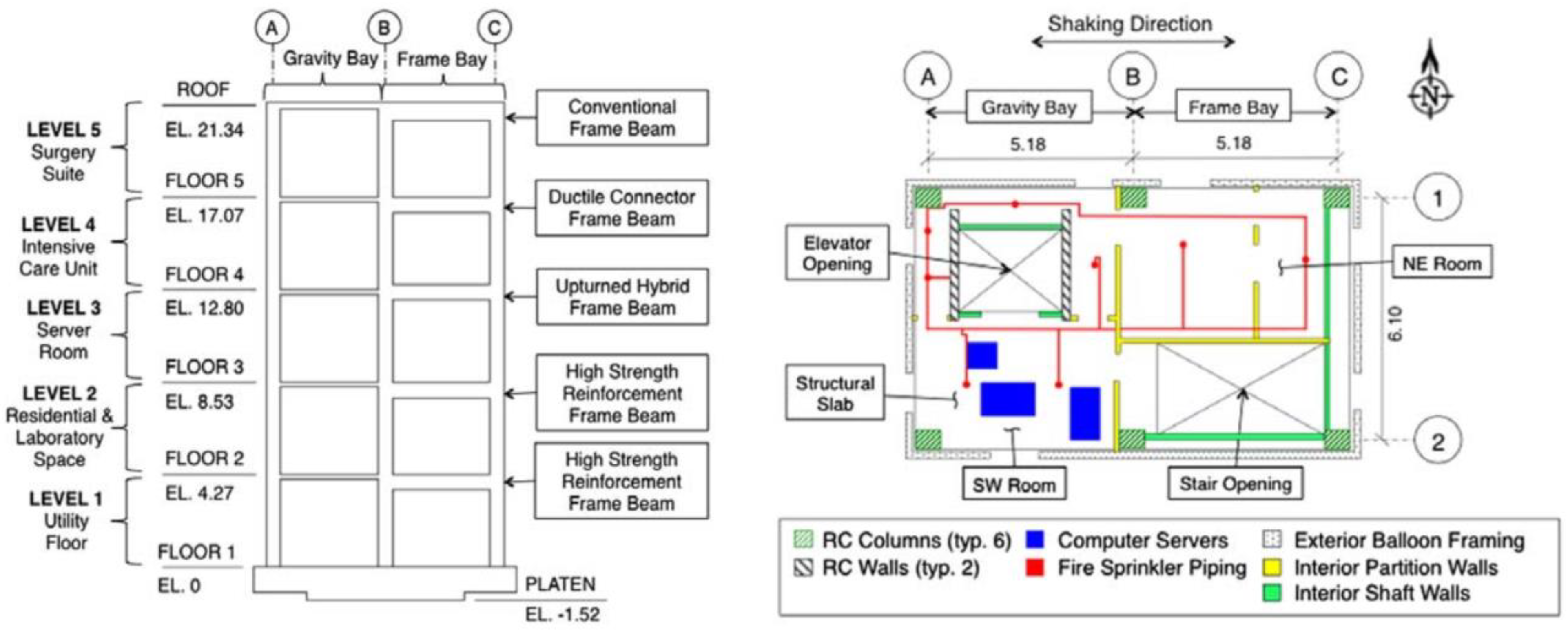

| 2 | Shake Table Test of Buildings | Shake Tables of multi-story buildings. Performance based seismic design framework using NSE's for Base isolated systems. | [11,18,51] |

| 3 | Shake Table Test of Nonstructural elements | Seismic performance of Fiber reinforced gypsum partitions, glass fiber reinforced facades, spider glazing facades and URM partitions on shake table beyond collapse prevention level. In-plane and out of plane behavior under shake table tests for claddings. | [25,27,33] |

| 4 | Nonstructural Elements | NSE like Fiber reinforced gypsum partitions, glass fiber reinforced facades, spider glazing facades and URM partitions, Claddings, Acceleration sensitive and displacement sensitive NSE, Fixed and Base isolated supports, damping in NSE | [4,5,7,8,9,10,11,14,20,22,23,24,26,28,29,31,32,34,35,36,37,39,40,41,43,44,45,49,50,52,54,61] |

| 5 | Sustainability and Resilience | Performance based design involving resilience, repair time and delay time, functionality loss, viscous damper effect, Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction, sustainability using BIM, sustainability impacts for dismantling | [53,55,56,57,60,63,64,65,66,67,68,72,74,82,96,97,98,99,100] |

| 6 | Life cycle cost assessment | Small housing, Steel frames, Concrete type, Prefabricated housing, Greenhouse effect, BIM tool for life cycle, Pre design stage life cycle, light weight floor effect, energy saving, circular economy in life cycle. | [15,17,70,73,75,76,81,84,85,86,87,88,89,92,93,94,95] |

| 7 | Environmental Life Cycle Assessment | Fiber reinforced concrete effect, Renewable energy, Technical and electrical equipment’s, green house with conventional house, Artificial intelligence and Digital Twin, Reduction in CO2 emissions, ecological problems due to construction, | [30,71,77,78,79,80,83,90] |

3. Building Systems Configuration and Performance Results

- 1.

- Suspended Ceilings

- 2.

- Fire Sprinkler Piping systems

- 3.

- Partition Walls

- 4.

- Precast Cladding Panels

- 5.

- Glazed Curtain Wall

3.1 . Fiber Reinforced gypsum partitions (FGP)

3.2. Unreinforced masonry partitions (URM)

3.3. Glass Fiber Reinforced Concrete (GFRC) Cladding façade

3.4. Spider Glazing Façade (SG)

4. Types of Non-Structural Elements

5. Sustainability and Resilience for Performance Evaluation

5.1. Steel Stairs

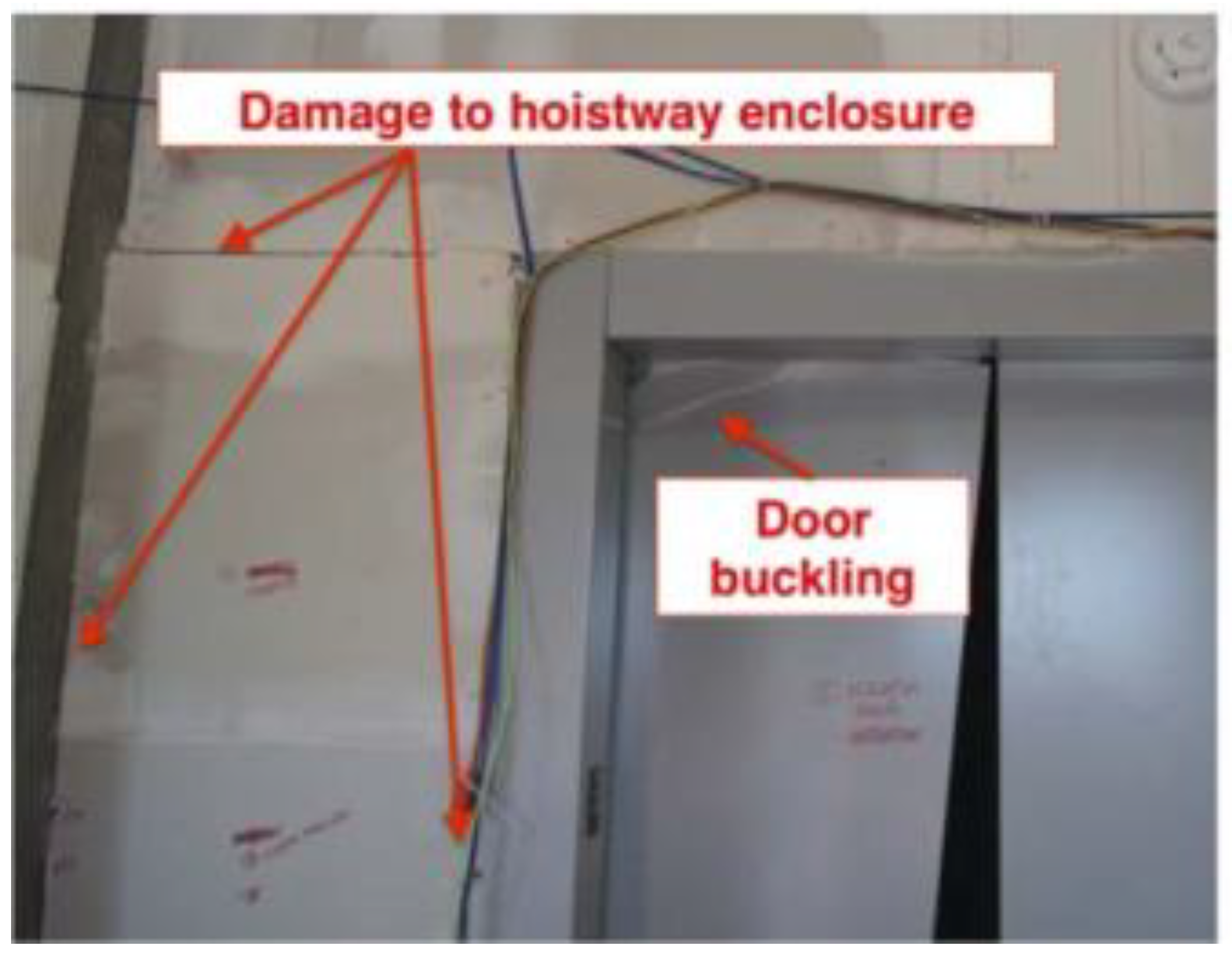

5.2. Passenger Elevator

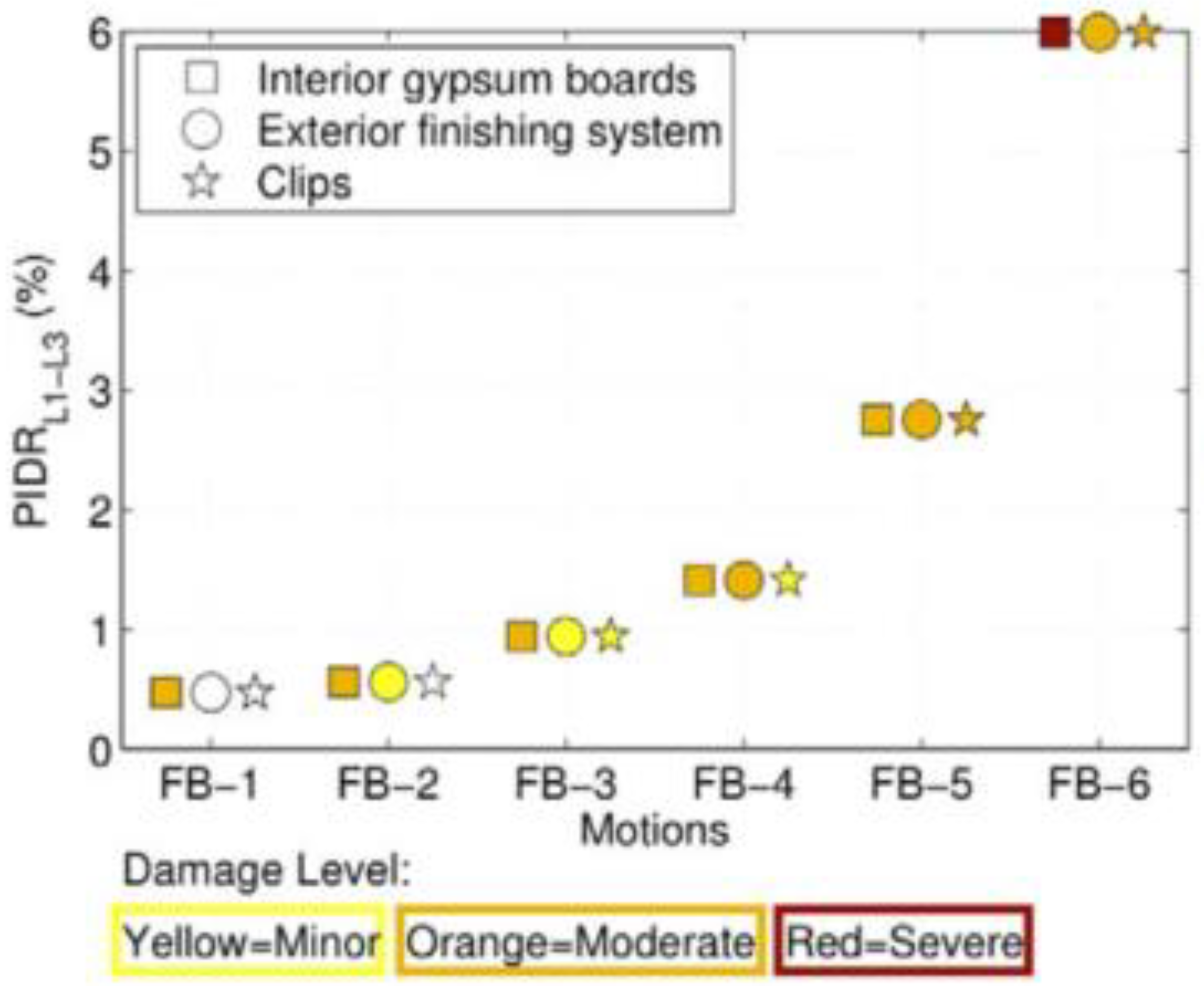

5.3. Architectural Façade

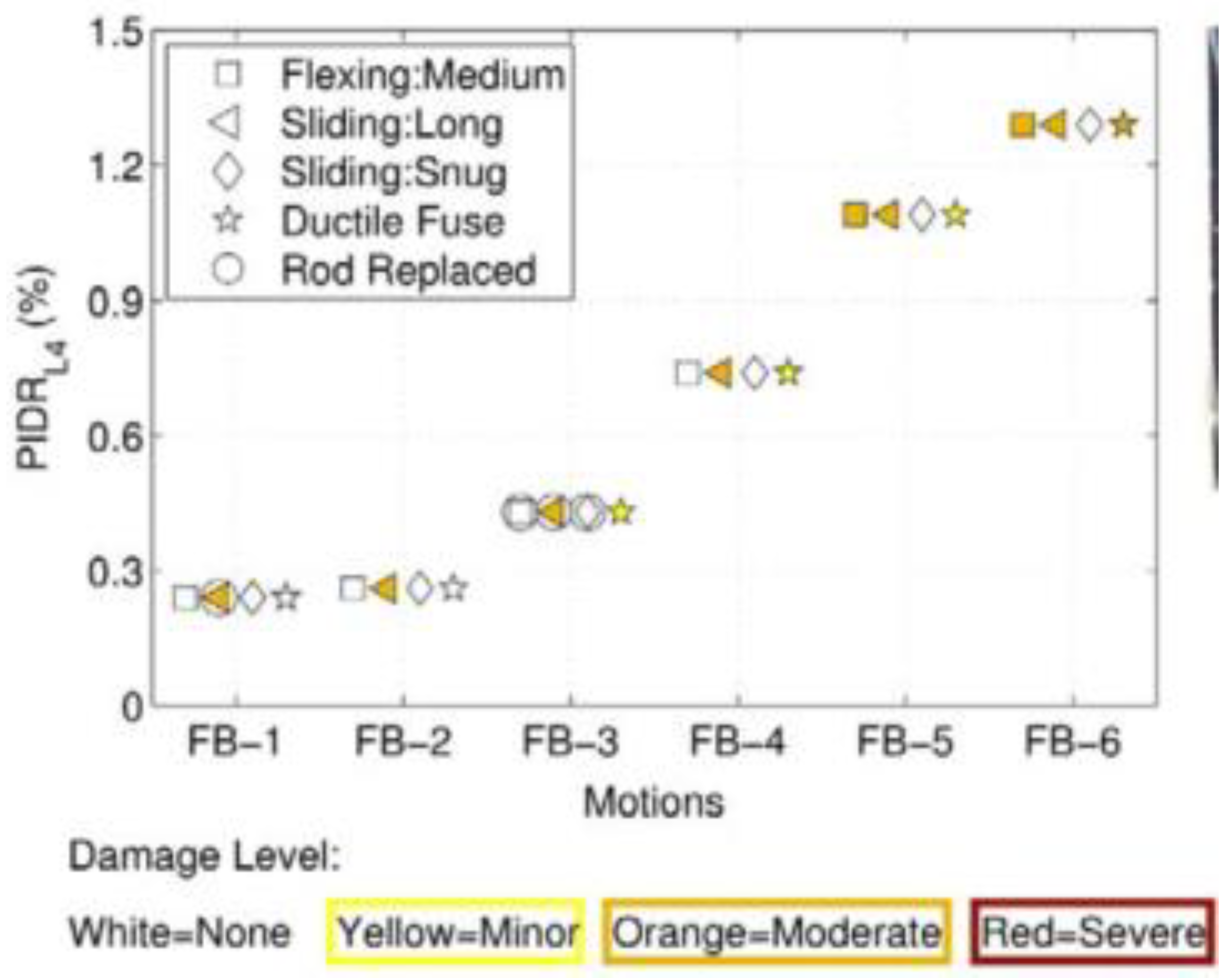

5.4. Precast Concrete Panels

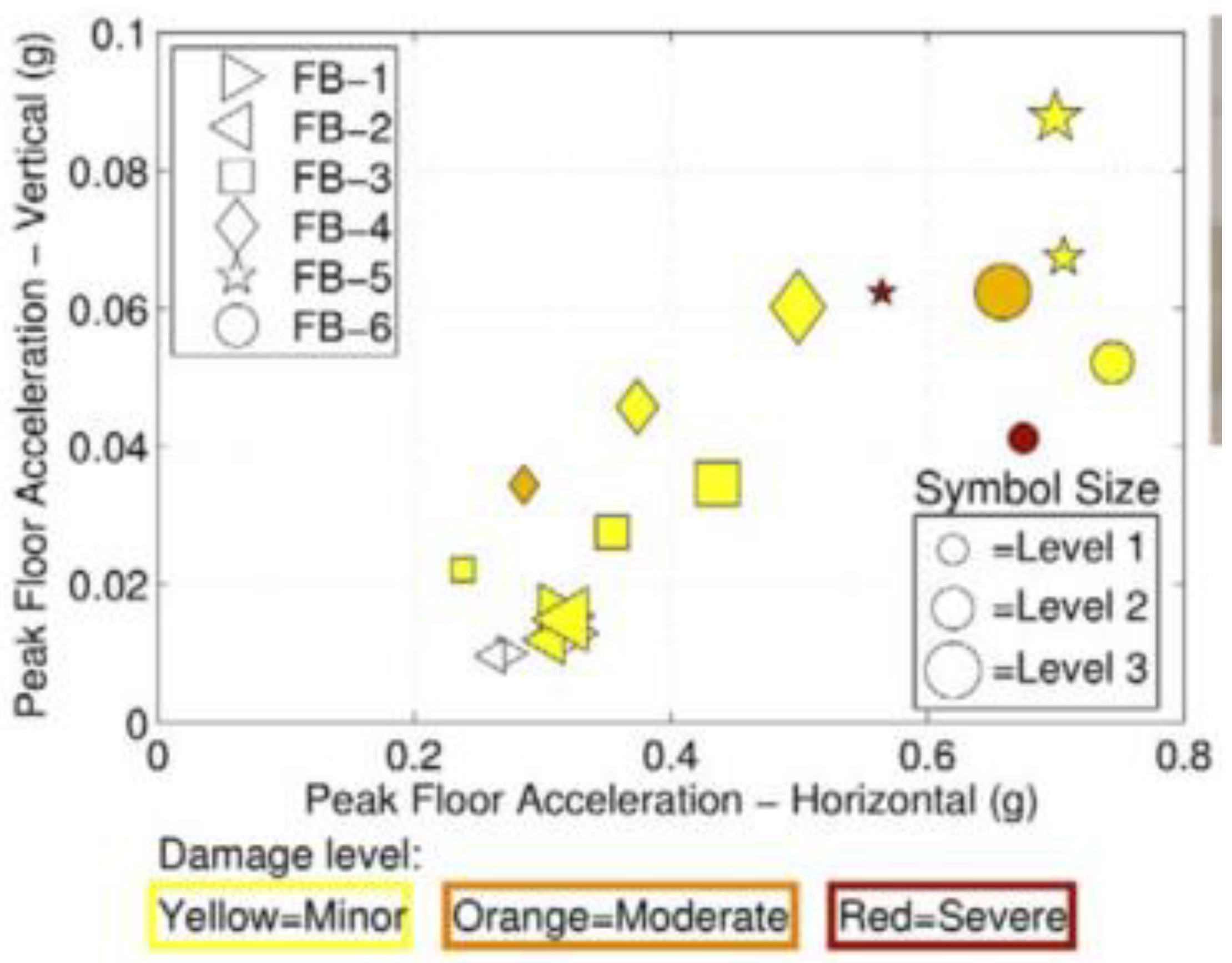

5.5. Ceilings

5.6. Services, HVAC, Piping, Sprinkler, Electrical

5.7. Computer Servers, Medical Rooms & Roof Top (Air Handling units & Cooling Towers)

5.8. Framework for Building Performance in the Assessment of Community Seismic Resilience

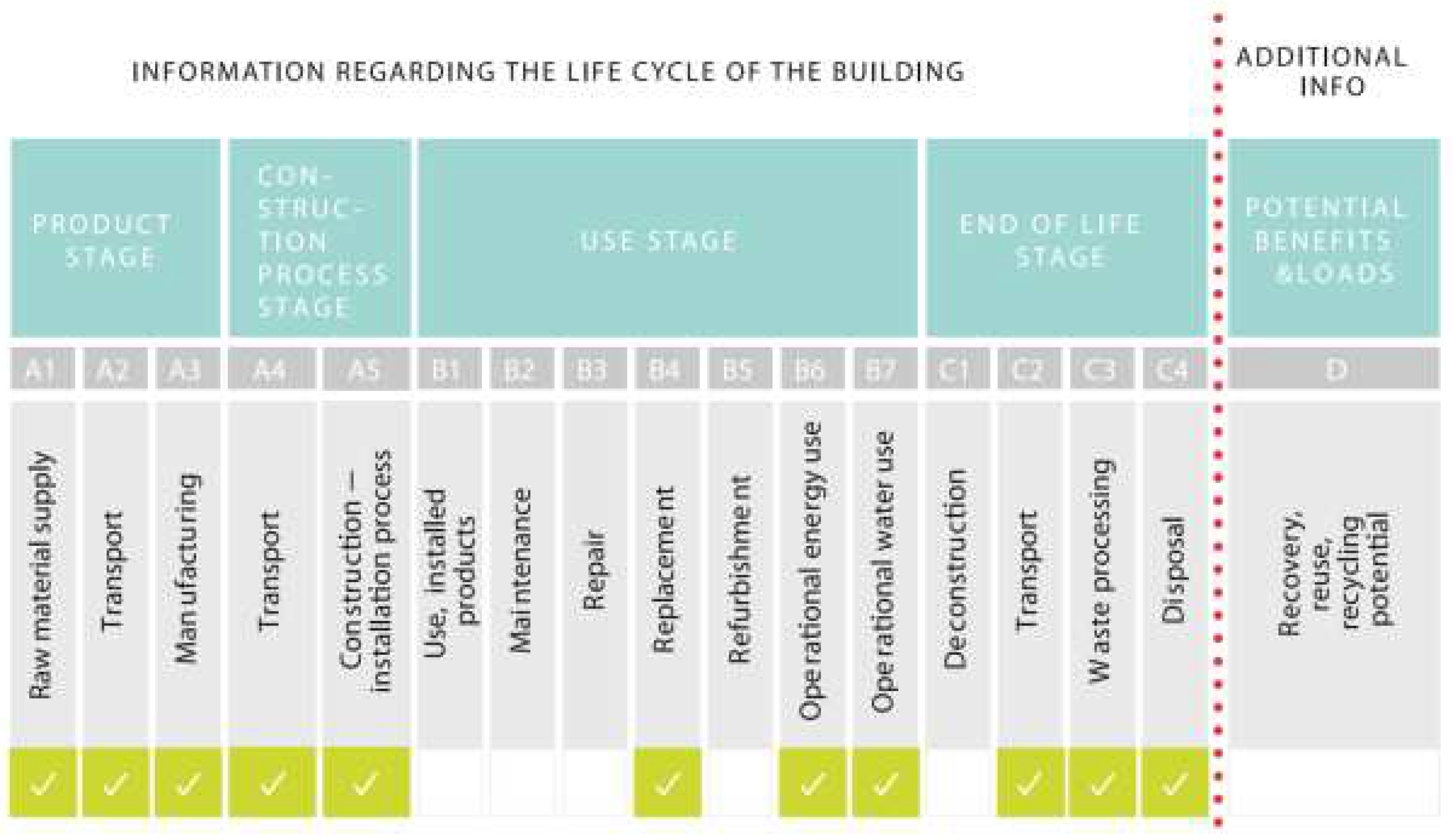

6. Life Cycle Assessment of NSE’s

7. Sustainability in Residential Buildings

7.1. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment

7.2. Life Cycle Cost Assessment

7.3. Social Life Cycle Assessment

8. Research Gap

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Ref No. | Authors | Study Area | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Devin, A. and P.J. Fanning | Effects of NSE's on the floor vibrations and associated Damping | Accurate methods for dynamic properties and modelling of NSE's not available | |

| 2 | Mohsenian, V., N. Gharaei-Moghaddam, and I. Hajirasouliha | Acceleration sensitive NSE's | Code based methods are not accurate and MDOF methods by different researchers need to be used to provide accurate results | |

| 3 | Chen, M.C., et al | Full Scaled Shake Table Tests of 05 Story RC Building under Fixed and Base isolator system | Comparison drawn with respect to max inter-story drift and base shear. However, detailed comparison between Base isolator system and Fixed system not shown | |

| 4 | Nicoletti, V., et al., | Infill wall contribution to the lateral load behavior of RC frame structures | For low and medium height buildings, masonry infill increases the lateral strength and for high rise, mass increase remain dominant behavior | |

| 5 | Dhakal, R.e.a. | Shake Tables of 3 story building for performance of NSE's | Tested for steel buildings only for low damage design under lateral loads | |

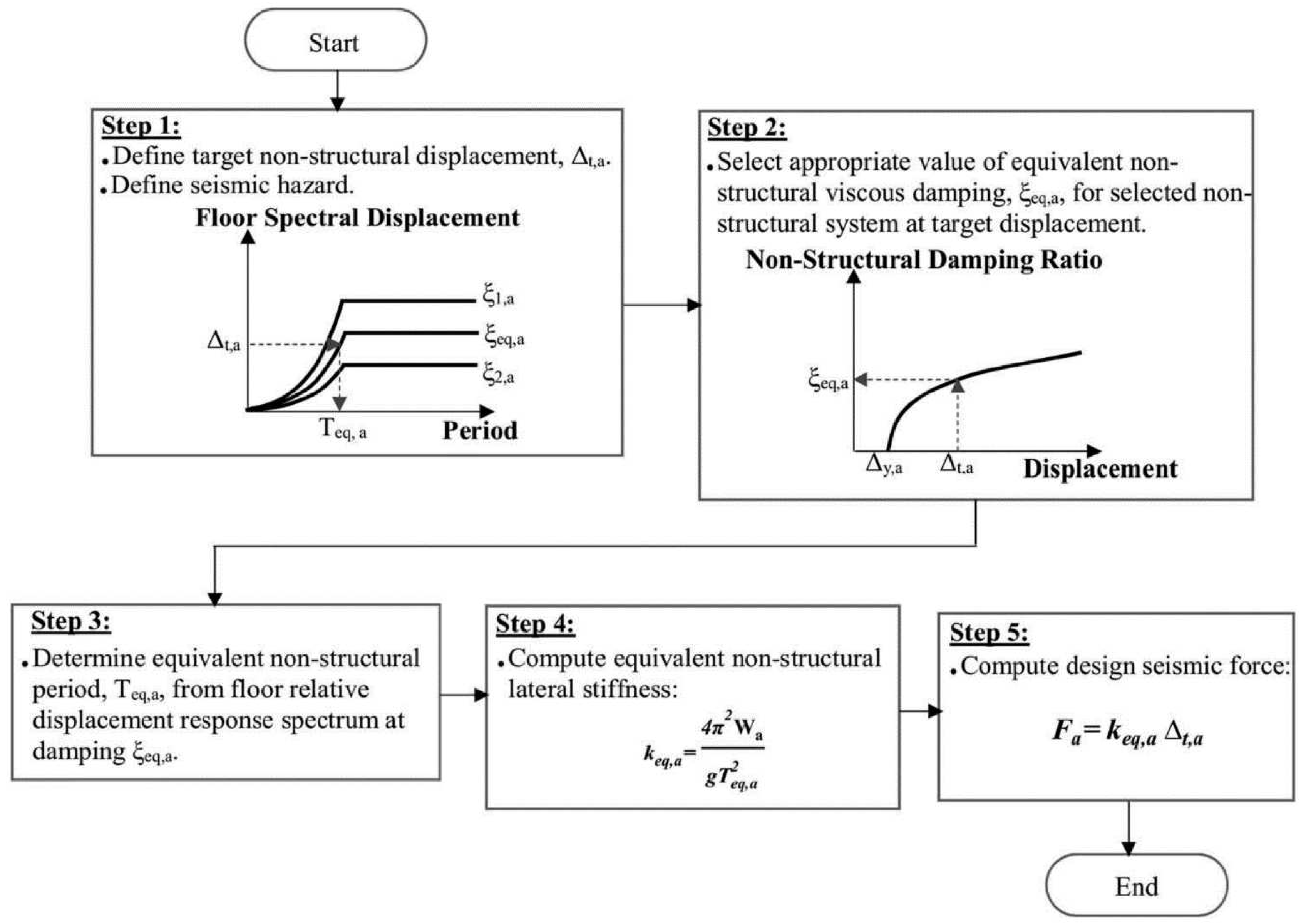

| 6 | Filiatrault, A., et al., | Direct displacement-based earthquake design for NSE's | Details of NSE's variation of global equivalent Viscous damping required and corresponding ground motions intensities and hazards Cyclic behavior of NSE's not established |

|

| 7 | Mohsenian, V., et al., | Reliability of NSE's in multi-story steel frames using different approaches | Only valid for acceleration sensitive NSE's, need to further study for displacement sensitive and a combination of acceleration-displacement sensitive NSE's | |

| 8 | Perrone, D., et al., | NSE's damages in Italy during 2016 earthquake due to non-following the code provisions | Remedial measures to repair/retrofit the damages not referred | |

| 9 | Sullivan, T.J., | Improving the design of SE's & NSE’s to repair it for post-earthquake performance with less cost | Research only done for partition wall and other NSE's performance not judged | |

| 10 | Bianchi, S., J. Ciurlanti, and S. Pampanin, | Damage control performance under maximum earthquake by Introducing gaps (vertical and horizontal) in NSE's to absorb the drifts during the earthquake | Models developed using pushover analysis for walls only, cyclic loading and spacings for different geometries needs to be done | |

| 11 | Michel, C., A. Karbassi, and P. Lestuzzi, | Retrofitting using numerical modelling and ambient vibration strategy | frequency increase shows stiffness is greater than the mass addition in the retrofitting work | |

| 12 | Chen, M.C., et al., | Performance based seismic design framework using NSE's for Base isolated systems | Limited for unidirectional seismic forces only | |

| 13 | Sousa, L. and R. Monteiro, | Retrofitting of NSE's Partition wall instead of SE to reduce losses and minimize costs | Limited for infill walls only and for a particular region | |

| 14 | Steneker, P., et al., | Including damping and sliding hinge joints at beam column connection to improve NSE performance | Limited for three story steel MRF | |

| 15 | Baltzopoulos, G., R. Baraschino, and I. Iervolino, | PBEE ground motion for structural risk assessment | Reduction in structural response by efficient intensity measure, does not inform the cost reduction | |

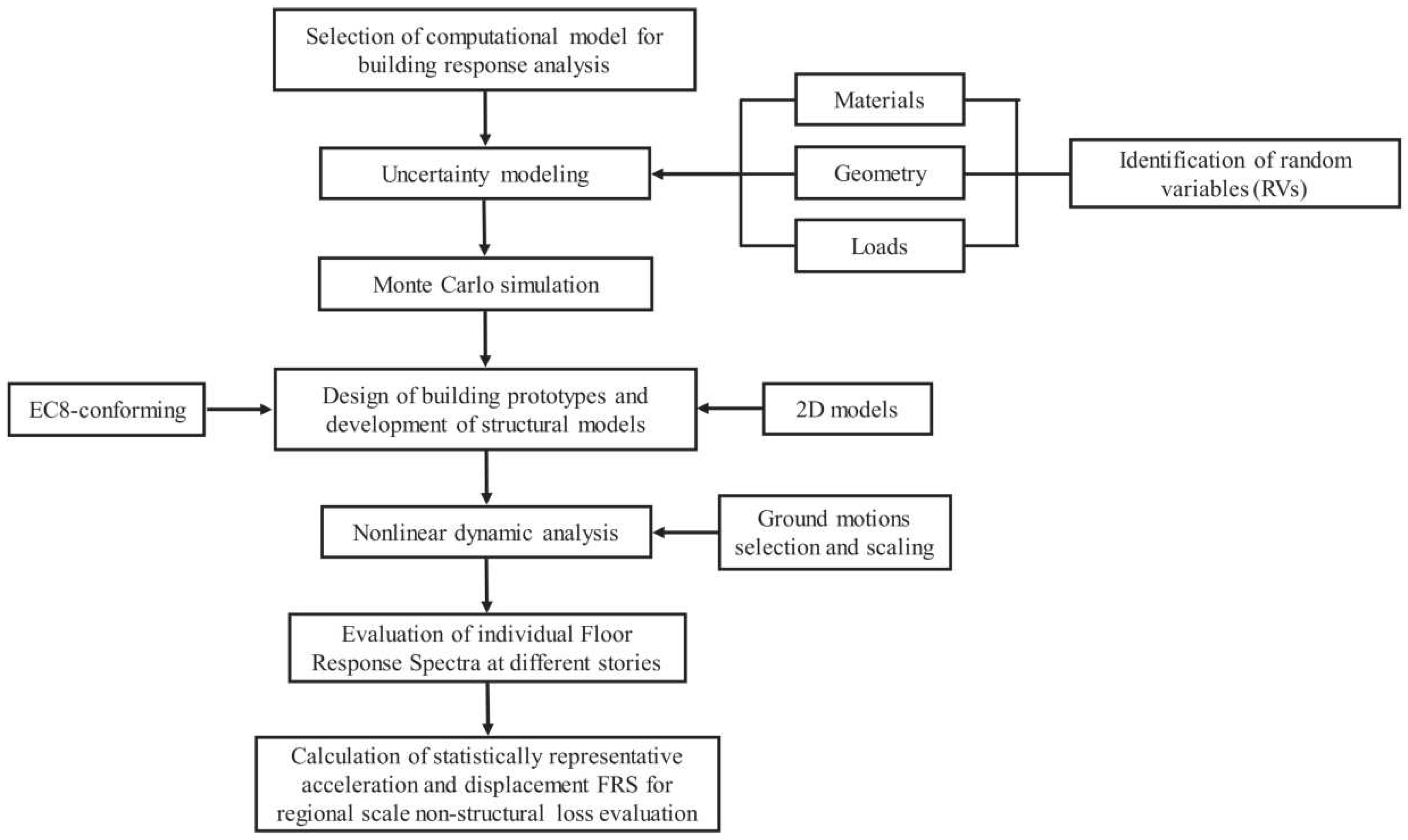

| 16 | Merino, R.J., D. Perrone, and A. Filiatrault, | Floor response spectra using direct displacement-based design procedure | time period for NSE's from NLTHA is assumed longer than 3 seconds which is not practicable | |

| 17 | H. Anajafi and R.A Medina | Equivalent static analysis for acceleration sensitive NSE as per ASCE 7-16 | limited to light NSE's only and may be conservative for heavier NSE's | |

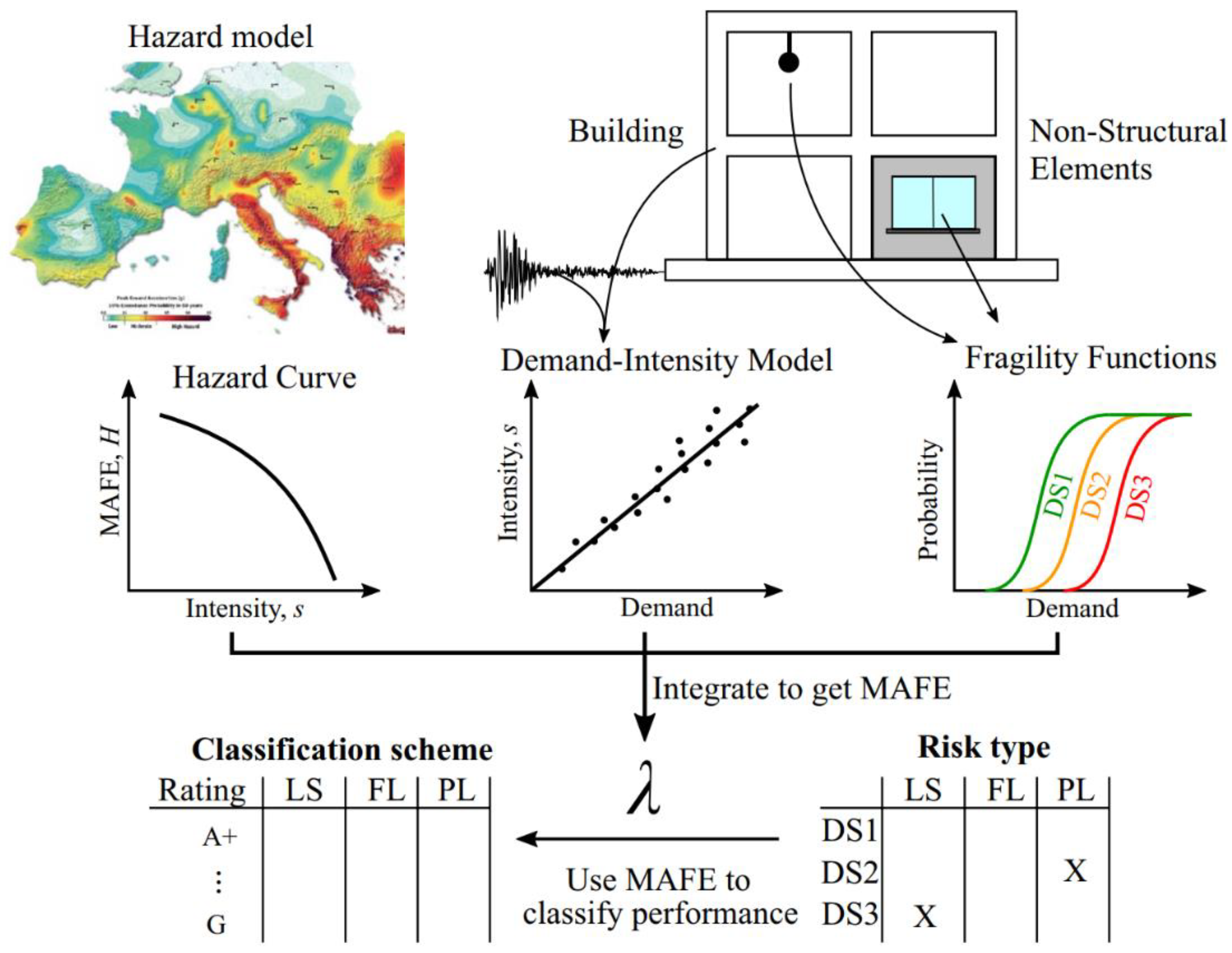

| 18 | O’Reilly, G.J. and G.M. Calvi, | Risk fragility for NSE's | Research work done on infill walls only. Other NSE's not discussed | |

| 19 | Berto, L., et al., | Floor response spectra for costly NSE's at ultimate limit state (ULS) and damage limit state (DLS) | Research based on 2D models and not all the different NSE's are discussed | |

| 20 | D'Angela, D., G. Magliulo, and E. Cosenza, | Rigid dominant behavior of unanchored NSE during earthquakes | Not categorized for a specific type of building whether steel or concrete, influence of frequency contents on NSE's and the sliding behavior of NSE's neglected in the study | |

| 21 | Reza Esfandiyar et al., | Viscous damper for seismic behavior of RC building | Simplified Maxwell model is desirable for the vicious damper | |

| 22 | Memduh Karalar, Murat Çavuşli | NSE's performance in RC building during strong earthquake | The study only takes into account the NSE loads as per IBC 2003 without taking into account the other properties like type of connections, nature of NSE's etc. | |

| 23 | Anwar, G.A., Y. Dong, and C. Zhai, | Sustainability and Resilience under earthquake for repair cost, repair time and embodied energy | Repair time is important for resilience and needs further research | |

| 24 | Yön, B., O. Onat, and M.E. Öncü, | Damages of hollow bricks infill walls in-plane and out of plane for RC framed buildings | Adequate retrofitting technique needed for repair, retrofitting and inclusion of NSE design provisions in Turkish Seismic Code (TSC) | |

| 25 | Sheshov, V., et al., | Survey of the damages to buildings during the 2019 Albania earthquake | Earthquake damages to the SE and NSE's without any guidelines on repair/retrofitting and adopting code-based design approaches | |

| 26 | Xu Bao, M.-H.Z., Chang-Hai Zhai, | Seismic response and fragility at near and far fault | Near fault earthquake analysis should be done for safety assessment of containment structure | |

| 27 | Filiatrault, A., et al., | NSE seismic performance evaluation for suspended elements using cyclic loadings | details regarding the NSE type in different MRF (Steel and concrete), size and specifications needs to be addressed further | |

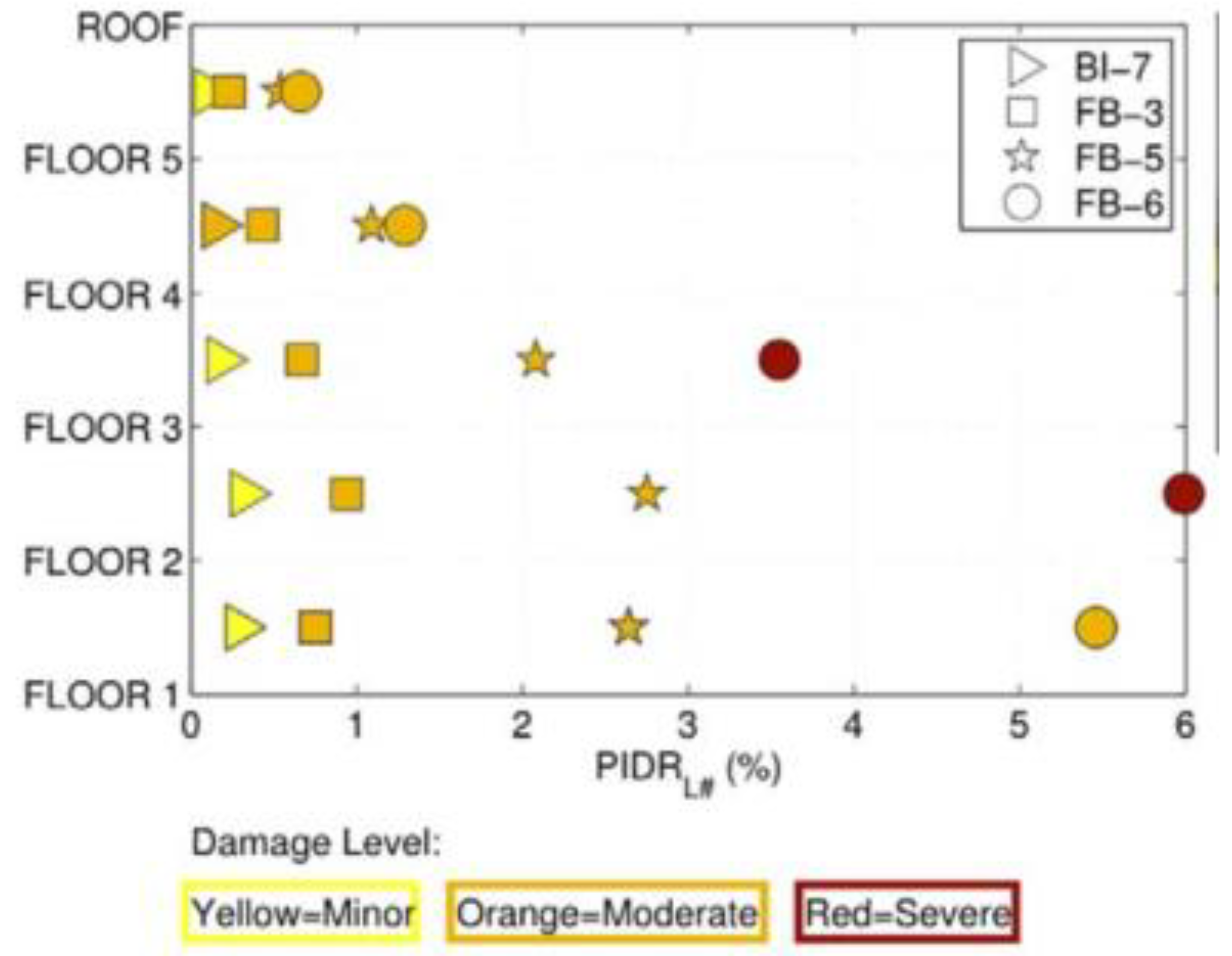

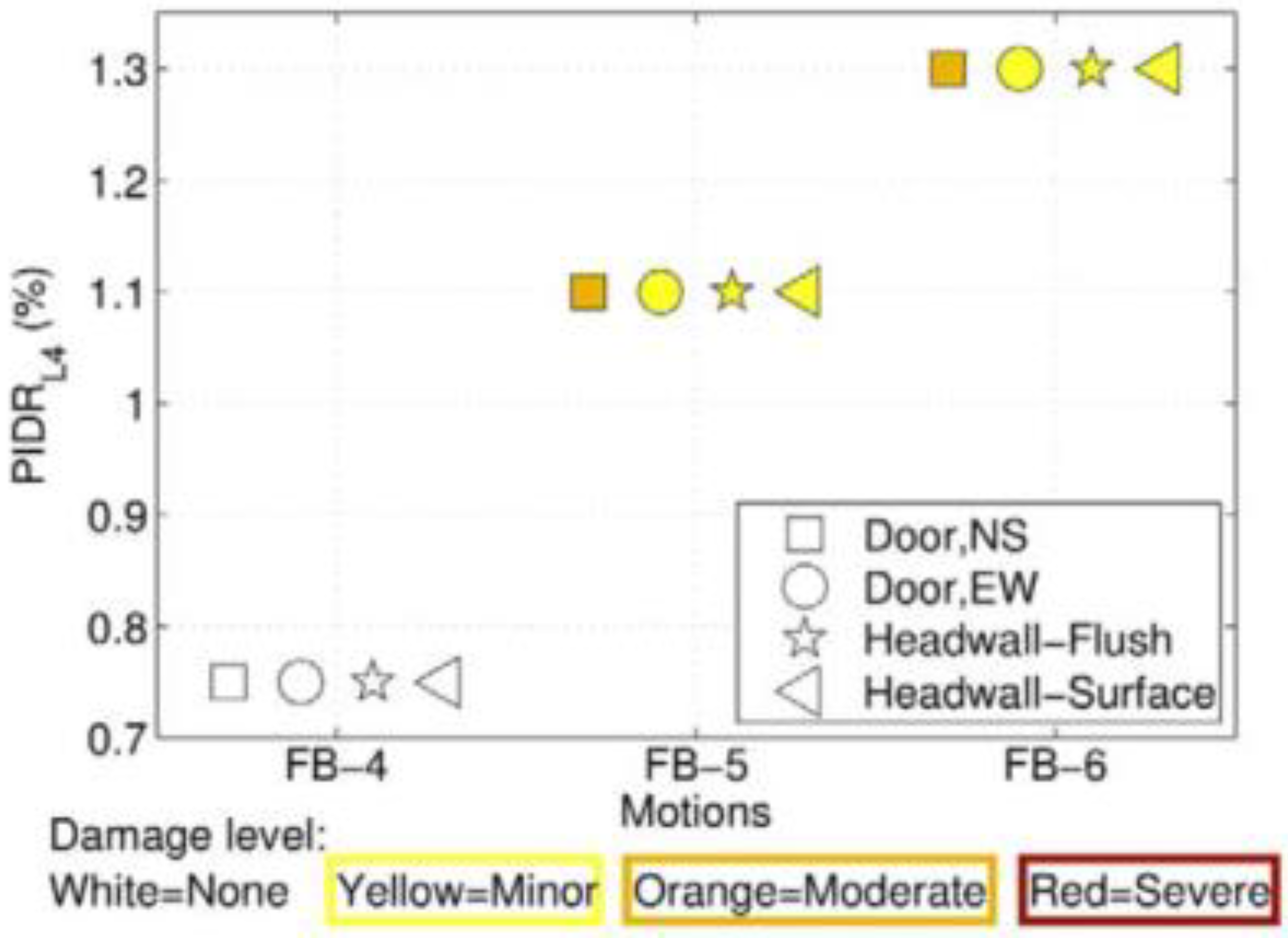

| 28 | Bianchi et al., | Seismic performance of Fiber reinforced gypsum partitions, glass fiber reinforced facades, spider glazing facades and URM partitions on shake table beyond collapse prevention level | out of plane behavior and expected annual losses (EAL) to be researched | |

| 29 | Pesaralanka, V., et al., | Amplification effects due to the soft story on acceleration sensitive NSE's | research limited to linear analysis only. Damages states of NSE's and EAL Losses needed to be researched further | |

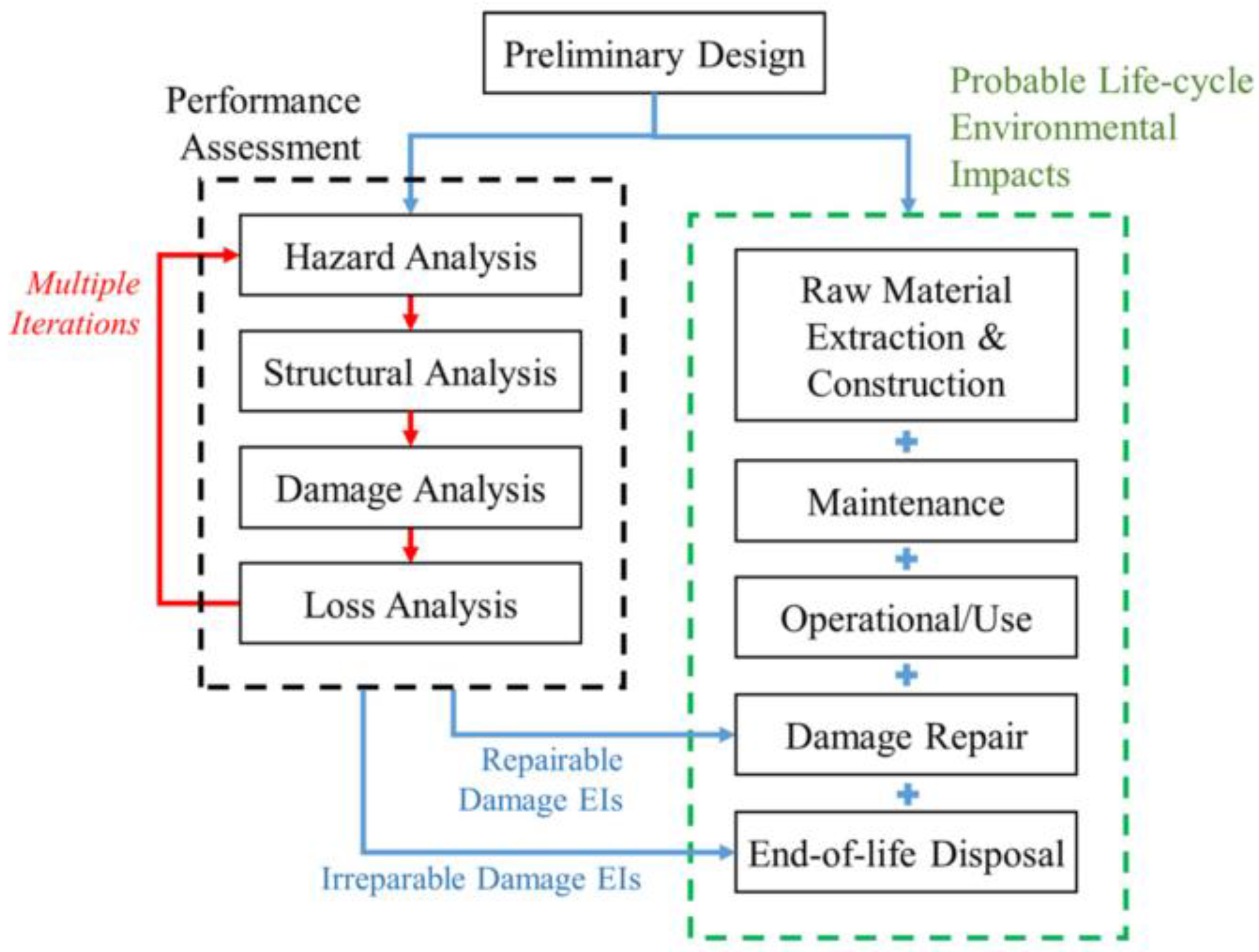

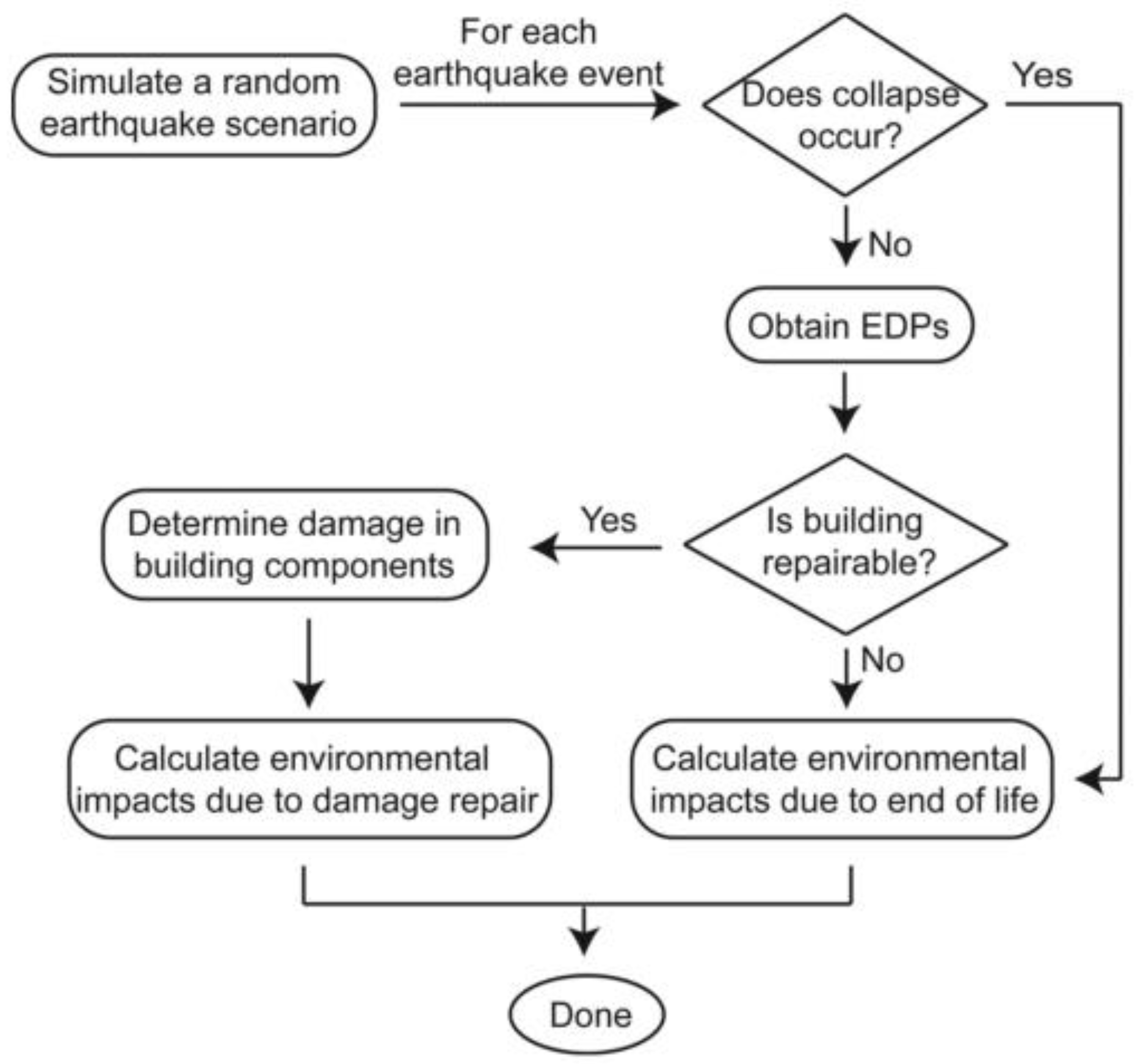

| 30 | Chhabra, J.P.S., et al., | Life cycle assessment due to seismic actions on steel building | Results based on the assumption that loss of function due to earthquake only and limited to the particular case study | |

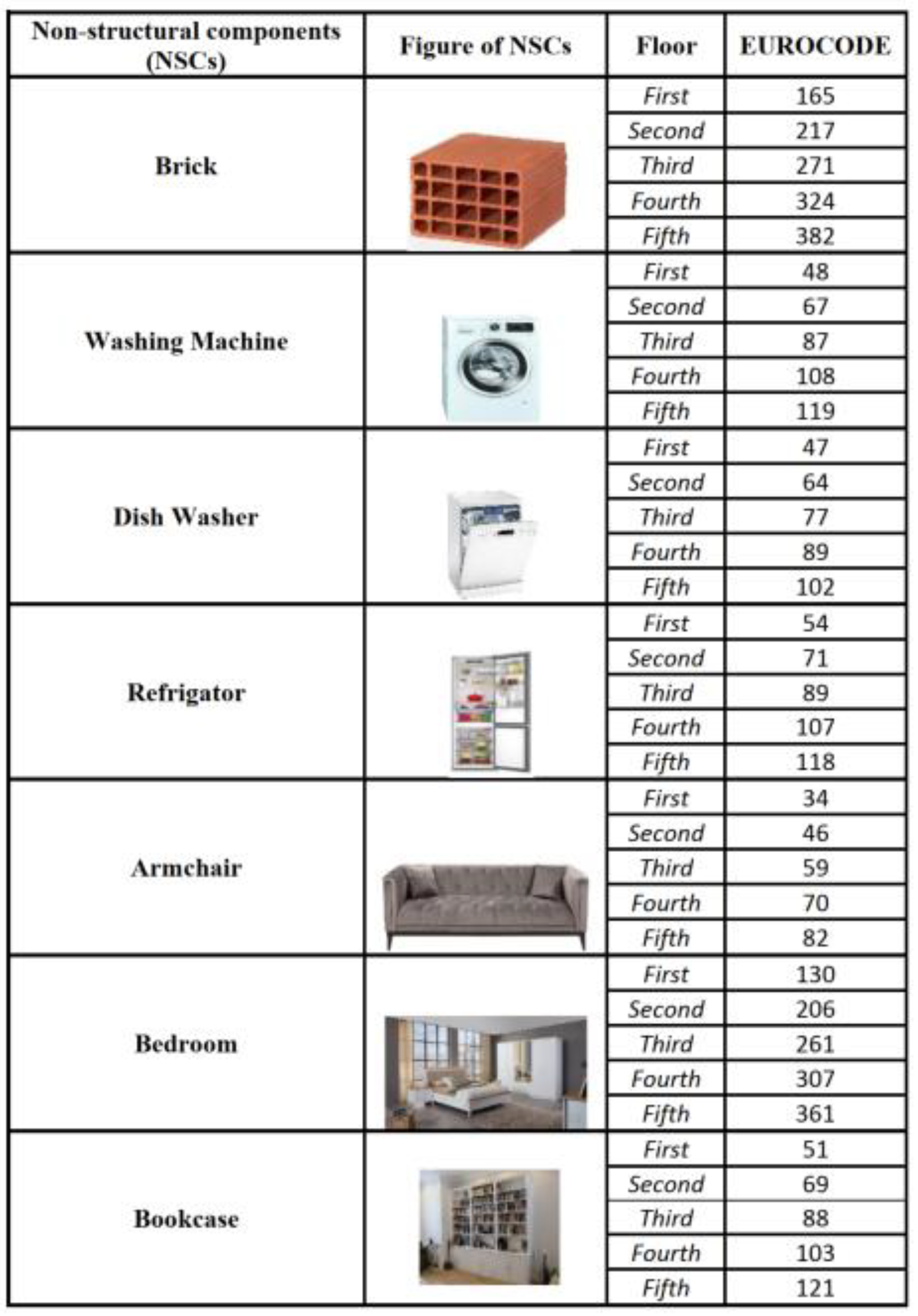

| 31 | Memduh Karalar, Murat Çavuşl | Performance of displacement sensitive NSE restraint in RC buildings as per Eurocode 8 | only the NSE loads are taken using SAP2000 software, more sophisticated FEA software’s like Abaqus, ATENA, DIANA FEA can be used | |

| 32 | Nardin, C., et al., | Shake Tables tests for Steel MRF using ground motion model | limited to steel MRF and particular tanks in industries only. Not valid for general buildings and different MRF other than steel | |

| 33 | Merino, R.J., D. Perrone, and A. Filiatrault, | Seismic design methods for force and displacement NSE's | For supporting systems sensitive to torsion and non-linear suspended NSE behavior needs to be researched | |

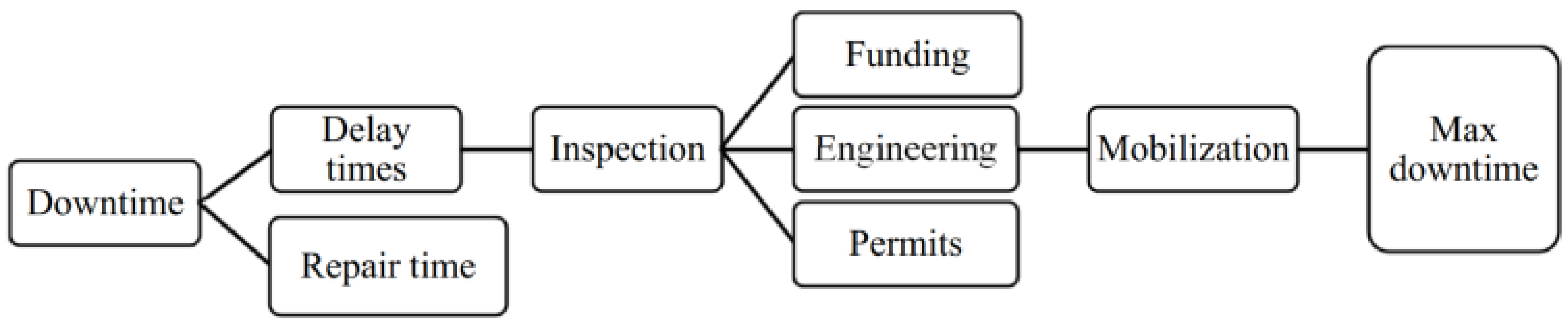

| 34 | Joyner, M.D. and M. Sasani, | Resilience based performance metrics considering the repair costs and functionality loss for buildings | Change in repair cost and loss of function depends upon building initial time period for which more research work is needed | |

| 35 | Perrone, D., et al., | Nonlinear time history analysis for floor response spectrum on masonry infill walls | Effects of openings, mechanical and geometrical properties for infill walls needs further study | |

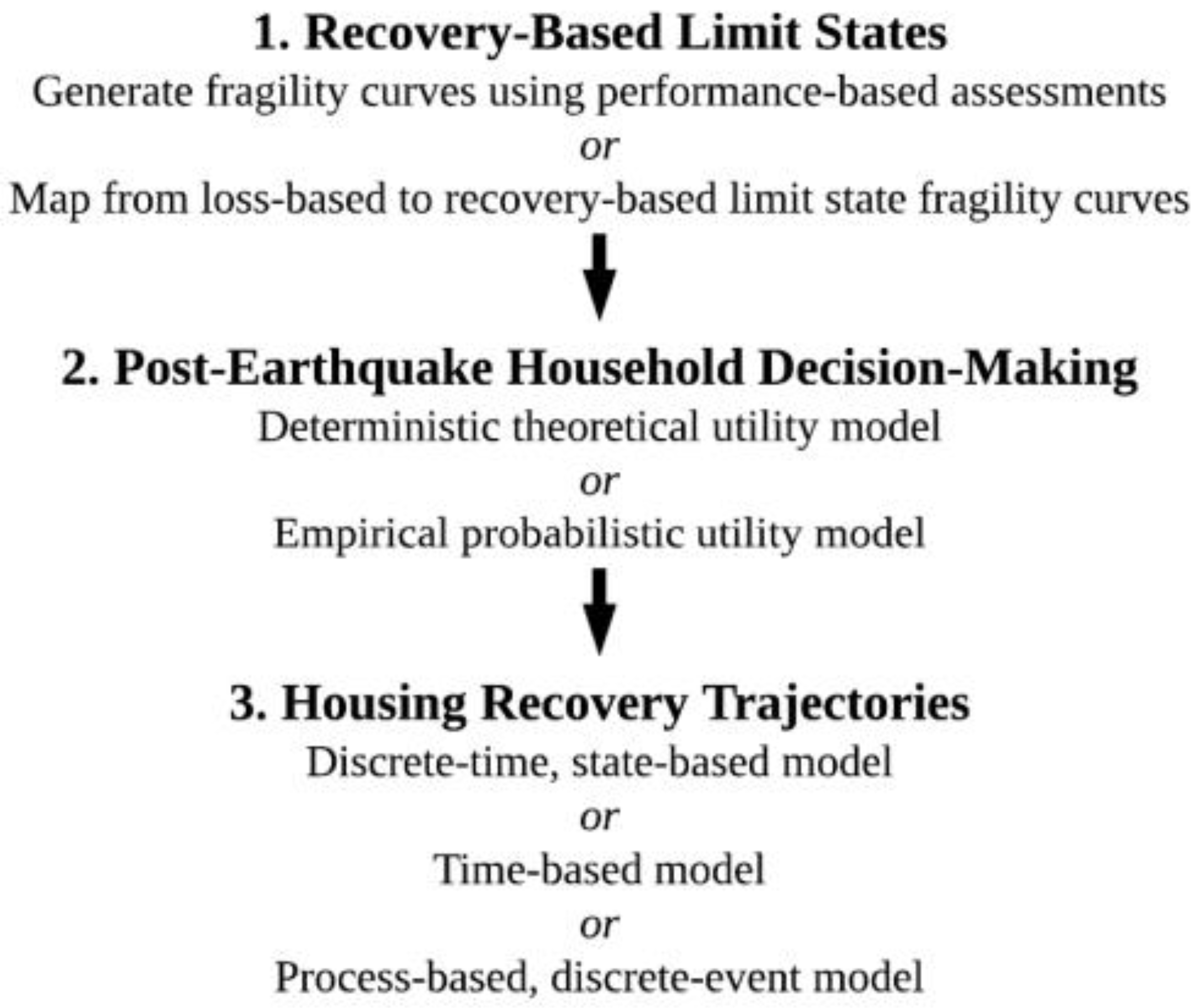

| 36 | Henry V. Burton et al., | Conceptual framework for post seismic action recovery of building | Pre earthquake and Post earthquake planning is needed | |

| 37 | Clementi, F., et al., | Vulnerability of old masonry building like churches during the 2016 earthquake at Italy | Numerical simulations coincide with damage witnessed in the churches | |

| 38 | Mieler, M.W. and J. Mitrani-Reiser, | Earthquake induced loss of functionality in buildings | further research needed to rectify the design gaps for quick functionality after a major earthquake | |

| 39 | Takagi, J. and A. Wada, | Performance of buildings in terms of functionality after an earthquake | Design of buildings and infrastructure should follow a resilient approach rather than life safety | |

| 40 | Liu, C., D. Fang, and L. Zhao, | Post earthquake behavior after 2015 Nepal earthquake | Performance of masonry wall under the earthquake can be improved using seismic band reducing the residual deformation | |

| 41 | Miranda et al., | Bracings designed for NSE to reduce the design forces and displacement demand | Bracings as support structures to free standing NSE proposed but the design force equation and the specifications needed further elaboration | |

| 42 | Eskandari, M., et al., | Damage assessment for critical infrastructure | Lifelines are very important and their ability depends upon their planning, design, implementation and maintenance | |

| 43 | Sisti, R., et al., | Performance of masonry walls during the 2016-2017 Italy earthquake | use of modern, sustainable and efficient materials can reduce the vulnerability of historical buildings (which are mostly unreinforced) | |

| 44 | O'Reilly, G.J., et al., | Seismic Assessment and Loss estimation of Existing Schools in Italy | Repair time and casualties are not included in this research | |

| 45 | Ottonelli, D., S. Cattari, and S.J.J.o.E.E. Lagomarsino, | Performance based method for masonry fragility using nonlinear response and finite element method | For existing buildings progressive damages under the pushover curve but for masonry quite challenging especially for monumental buildings | |

| 46 | Cardone, D., G. Perrone, and A. Flora, | Direct losses related to the post-earthquake repair costs | Can be used for unsymmetrical geometry and uneven floor occupancy types | |

| 47 | Cosenza, E., et al., | Safety index at the life safety performance level | Further research needed to for precise determination of expected annual losses (EAL) | |

| 48 | Del Vecchio, C., M.D. Ludovico, and A. Prota, | Repair costs associated with 120 RC buildings damaged during the 2009 L'Aquila earthquake | Hollow bricks are very brittle in nature, further research needed to compare the repair costs for buildings with no Damage state | |

| 49 | Gerardo Araya-Letelier et al., | To improve the drift capacity of Gypsum partition walls under earthquake loads | Friction/sliding connection lowers the risk in Gypsum partitions vulnerable to lateral loads under low story drifts | |

| 50 | Yön, B., | Performance of locally made unreinforced masonry in an earthquake | Wall strengthened with medium steel ratio can increase the ductility by 45.71% | |

| 51 | Derakhshan, H., et al., | Fragility of URM under lateral loadings for rapid assessment of seismic risk to NSE | larger dispersion values should be used for walls due to material and geometrical uncertainty | |

| 52 | Menichini, G., | Damage pattern of the infill precast concrete panels | interface between the RC member and the panel must carry the out of plane loading from the impact of loadings and the inertial forces on the panel | |

| 53 | Wang, W., et al., | performance of precast façade assembled with steel structure | Assembled façade perform differently when in connection, so extensive research is needed | |

| 54 | O’Hegarty, R., et al., | High Performance fiber reinforced concrete panels for environmental improvement | Types of materials used as a replacement to traditional aggregates should be environmentally friendly along with meeting the strength requirements | |

| 55 | Urbańska-Galewska, E., O. Zapała, and D. Wieczorek, | Performance of Transparent faces in construction | Right concept and selection of type used can reduce the construction cost as well as reduce energy requirements | |

| 56 | Adhikari, R.K. and D. D’Ayala, | Sensitivity analysis of different materials under earthquake | Stone in mud mortar shows different level of performance due to quality control issue, improvement in seismic performance as a result of retrofitting can be made possible | |

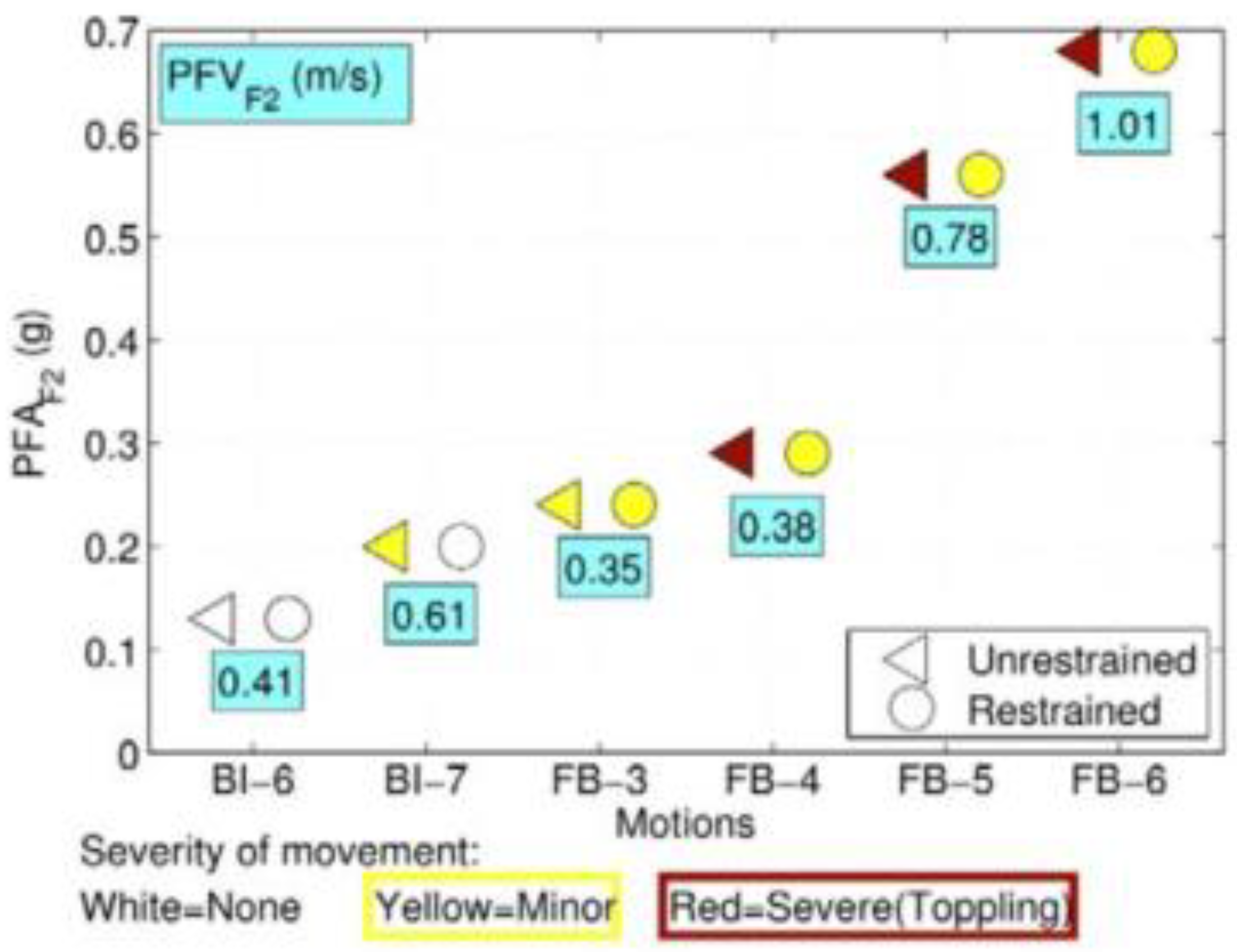

| 57 | Pantoli, E., et al., | Performance of NSE under Fixed and Base isolated systems | Independent performance of NSE tested under shake table needs further research | |

| 58 | Anwar, G.A., Y. Dong, and Y. Li, | sustainability and resilience in the performance-based decision making under earthquakes | different retrofitting options can serve as multi-criteria decision-making for seismic loss, sustainability and resilience | |

| 59 | Hassan, W.M., et al., | Performance of composite column i.e., steel and concrete for older buildings | ACSE 41-17 overestimates and underestimates the resilience and vulnerability respectively | |

| 60 | Furtado, A., et al., | Resilience incorporating the delay time and non-structural elements | Underestimating resilience be avoided and preventive measures for school type building be taken in post-earthquake planning | |

| 61 | González, C., M. Niño, and G. Ayala, | Delay time and Non-structural Elements in Resilience | Simplified approach for accessing the seismic resilience is not reliable approach | |

| 62 | B. Larson et al., | Performance of Viscous Damped Moment Frame building for Resilience | Detailing on NSE is important to improve Resilience | |

| 63 | Morán-Rodríguez, S. and D.A. Novelo-Casanova, | Seismic vulnerability of health facilities including structural and non-structural elements | Model proposed can perform better in vulnerability assessment by utilization the data collection and classifying them, this approach based for Mexico can be used in other regions | |

| 64 | Heidari, M., N. Eskandary, and S.S. Miresmaeeli, | effects of earthquake on infrastructure near the fault line against the quality of material used and other factors | Government should formulate useful policies to reduce vulnerability and increase resilience | |

| 65 | You, T., W. Wang, and Y. Chen, | Novel long term resilience indicator for earthquake resilience of a community | Proposed model gives good performance compared to routine methods | |

| 66 | Anwar, G.A., Y. Dong, and M. Ouyang, | Community resilience assessment methodology in earthquakes | The study used of HAZUS, REDITM Rating system and others etc., site specific data can be based for better estimating the community resilience | |

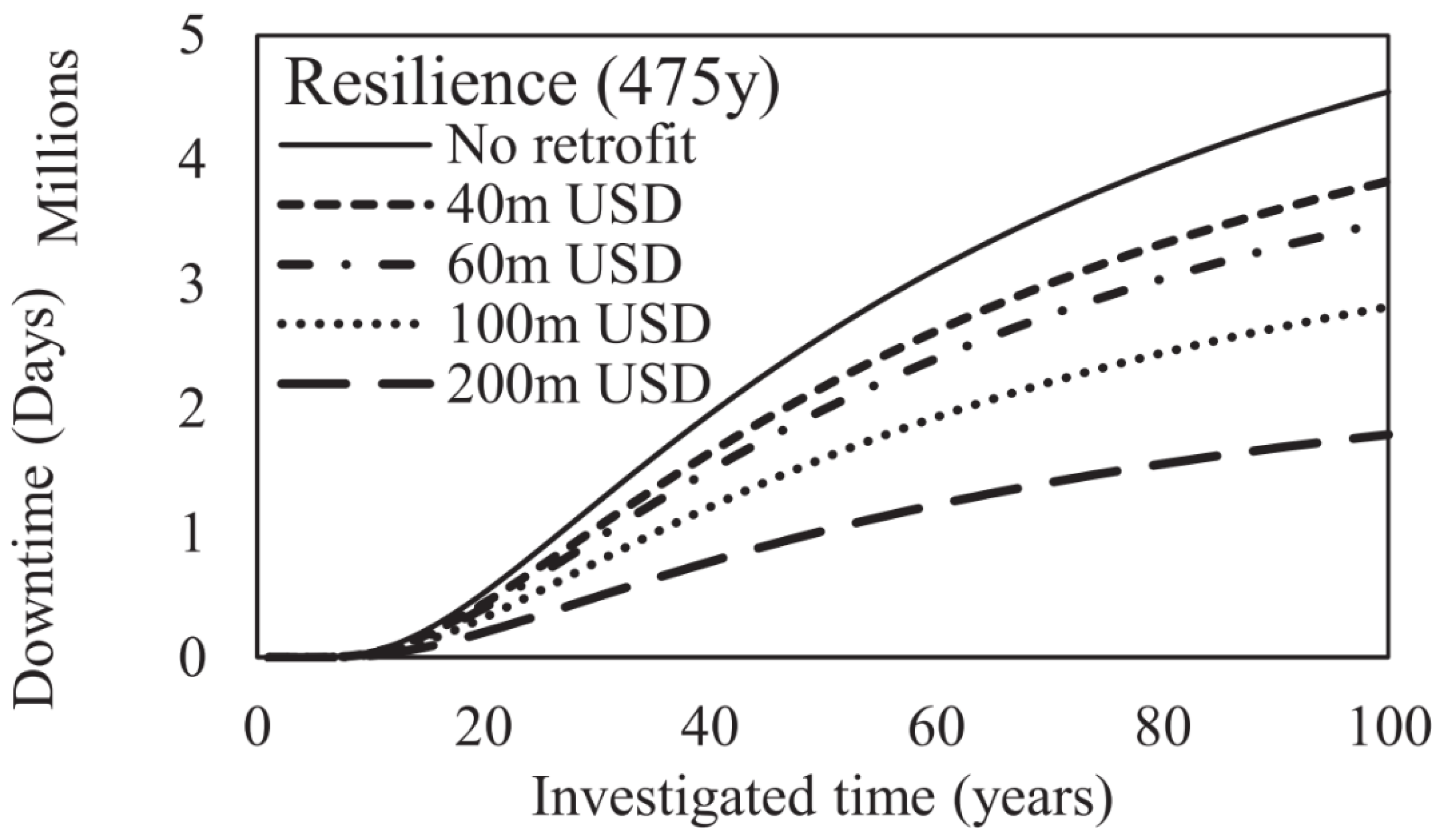

| 67 | Anwar, G.A., Y. Dong, and M.A. Khan, | Community level Framework for increasing sustainability and resilience of building systems | Repair costs and downtime can be reduced by appreciable retrofitting costs | |

| 68 | Asadi, E., A.M. Salman, and Y. Li, | A coupled resilience and sustainability-based decision framework | Diagrids have good lateral capacity, can reduce the CO2 emissions but ample knowledge of the construction quality is required | |

| 69 | Freddi, F., et al., | Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 for cost effective methods | Innovations like Structural Health Monitoring, Early earthquake warning and numerical modelling can be challenging for low-income countries | |

| 70 | Gao, X. and P. Pishdad-Bozorgi, | Review on BIM applications and O&M practices | BIM can improve the efficiency of O&M activities | |

| 71 | Eskew, J., et al., | Renewable energy alternative as an environmentally friendly approach | by further exploring the idea, marked reduction in dependence over fossil fuels can be made which is environmentally friendly also | |

| 72 | Hajek, P., et al., | Sustainability using BIM | BIM reduces final costs and delays resulting in economic stability | |

| 73 | Bojana et al., | Life cycle assessment for small houses in Sweden | Energy usage and water consumed not covered in this study | |

| 74 | Shahana Y. Janjua et al., | Comparison of the different sustainability measures for a residential building | Region bases Life cycle sustainability assessment required to cover the environmental, social and economic aspects | |

| 75 | Manjunatha, M., et al., | Impact of concrete composition on the life cycle and environment aspect | Portland pozzolana cement and ground granulated blast furnace slag makes the concrete sustainable material reducing CO2 emissions | |

| 76 | Teng, Y., et al., | Reducing building life cycle costs assessments using prefabricated buildings | Review shows the advantages of Life cycle cost assessment using prefabricated buildings is inconsistent and not clear due to number of opinions | |

| 77 | Fnais, A., et al., | Environmental aspects of building on the lifecycle | Building's environmental impact cannot be deducted by considering only the major components | |

| 78 | Hoxha, E., et al., | Environmental impacts of technical equipment’s and electrical equipment’s | For complex buildings and huge systems, Life cycle costs are faced with a number of challenges | |

| 79 | Yao, L., A. Chini, and R. Zeng, | Comparison of green roof with conventional roofs | Green roof performs better environmentally but the initial and maintenance costs is higher than conventional roof system | |

| 80 | Bilal, M., et al., | Building energy efficiency through integrating of technologies, Artificial intelligence, Digital Twins, BIM | Building automation system performance increased, better integration with the industry can be further researched | |

| 81 | Jayalath, A., et al., | Impact of cross laminated timber on the greenhouse effect and Life cycle cost during construction | overall good impact but operation cost can be further reduced using recycling technique for sustainability | |

| 82 | Eberhardt, L.C.M., H. Birgisdóttir, and M. Birkved, | impacts on sustainability using designed for dismantling strategy | to reduce the negative environmental effects, circular economy principles using Design for dismantling type is beneficial | |

| 83 | Schwartz, Y., R. Raslan, and D. Mumovic, | Environment friendly construction to minimize the CO2 emissions | use of refined materials, the CO2 emissions can be reduced by 80% subject to recycling potential of the materials | |

| 84 | Altaf, M., et al., | Life cycle cost analysis awareness in industry at Malaysia | 5%-16% of industry knows the importance of Life cycle cost assessment | |

| 85 | Nwodo, M.N. and C.J. Anumba, | Various challenges in the Life cycle assessment of buildings | BIM Tool can enhance the data collection and storage. Only web of science source used for the review | |

| 86 | Roberts, M., S. Allen, and D. Coley, | Importance of Life cycle analysis is pre design stage | Life cycle analysis faces barriers in terms of method and practice in early design impacting the environmental performance | |

| 87 | Ahmed, I.M. and K.D. Tsavdaridis, | Use of lightweight flooring for reducing the Life cycle cost and overall efficiency | Precast sandwich panel reduces life cycle cost by 21% compared to cast in situ structures | |

| 88 | Zhang, L., J. Wu, and H. Liu, | Green Building is benefits for life cycle of a building | Overestimation in the initial costs, cost benefits for green building approach need further research | |

| 89 | Song, X., et al., | Effects of Geotechnical works on the Life cycle cost for buildings | Discrepancies in literature on the life cycle assessment of buildings for foundations, impact categories and sensitivity analysis of LCA results | |

| 90 | Wang, Z., Y. Liu, and S. Shen, | Environmental and ecological problems due to the building construction in China | Recycling of the material reduces the CO2 emissions and minimizes the energy required during disposing off the dismantled material | |

| 91 | Khalid, H., et al., | Life cycle cost assessment by saving energy using reduction of cooling load in buildings | Limitations regarding modelling and analysis of the target objectives | |

| 92 | Hossain, M.U., et al., | Shift from Linear economy to circular economy in construction sector | Circular economy can improve the practicability for sustainable construction with further research towards case specific buildings | |

| 93 | Hwang, B.-G., M. Shan, and J.-M. Lye, | Solution of the hurdle’s small constructors face during project execution | Role of the client/government is important to pave way for smooth project management and resolve smaller firms for sustainable service delivery | |

| 94 | Potrč Obrecht, T., et al., | Linking Life cycle costing with Building information modelling (BIM) | capability of BIM should not be overlooked and the manual data can be integrating into BIM | |

| 95 | Altaf, M., et al., | Using BIM Tool with Life cycle cost assessment to optimize the energy requirement | Initial cost may be higher but the maintenance cost is low for the 20 years which optimizes the Life cycle cost | |

| 96 | Srivastava, S., U.I. Raniga, and S. Misra, | Challenges in integrating social, economic and environmental aspects in construction sector | Sustainable construction can be ensured using the Triple Bottom approach covering the social, economic and environmental aspects | |

| 97 | Goel, A., | Social Sustainability based analysis of feasibility study using the community salient perspective | insufficient data available from developing countries to judge the social sustainability of construction projects | |

| 98 | Goel, A., L.S. Ganesh, and A. Kaur, | Conceptual framework for social sustainability with Construction project management (CPM) | Gap between temporary project organizations and permanent project organization can be reduced using the conceptual framework approach | |

| 99 | Santarelli, S., G. Bernardini, and E. Quagliarini, | debris estimation for safety analysis of occupants for evacuation during an earthquake hazard | This approach can help in quick rescue and safe evacuation countering the challenges due to blockage and narrow streets challenging the rescue activities | |

| 100 | Amini Hosseini, K. and Y.O. Izadkhah, | Awareness about disaster management by involving the community | Highly beneficial for preparedness in school in Iran and can be followed in other earthquake prone regions |

References

- Mieler, M.W. and J. Mitrani-Reiser, Review of the State of the Art in Assessing Earthquake-Induced Loss of Functionality in Buildings. Journal of Structural Engineering, 2018. 144(3). [CrossRef]

- Takagi, J. and A. Wada, Recent earthquakes and the need for a new philosophy for earthquake-resistant design. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, 2019. 119: p. 499-507. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., D. Fang, and L. Zhao, Reflection on earthquake damage of buildings in 2015 Nepal earthquake and seismic measures for post-earthquake reconstruction. Structures, 2021. 30: p. 647-658. [CrossRef]

- Mohsenian, V., N. Gharaei-Moghaddam, and I. Hajirasouliha, Multilevel seismic demand prediction for acceleration-sensitive non-structural components. Engineering Structures, 2019. 200. [CrossRef]

- Miranda et al., Towards a new approach to design acceleration-sensitive non-structural components 2018.

- Eskandari, M., et al., Sensitivity analysis in seismic loss estimation of urban infrastructures. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk, 2018. 9(1): p. 624-644. [CrossRef]

- Yön, B., O. Onat, and M.E. Öncü, Earthquake Damage to Nonstructural Elements of Reinforced Concrete Buildings during 2011 Van Seismic Sequence. Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities, 2019. 33(6). [CrossRef]

- Perrone, D., et al., Seismic performance of non-structural elements during the 2016 Central Italy earthquake. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 2018. 17(10): p. 5655-5677. [CrossRef]

- Tanja KALMAN ŠIPOŠ et al., STRUCTURAL PERFORMANCE LEVELS FOR MASONRY INFILLED FRAMES. 2018.

- Sullivan, T.J., Post-Earthquake Reparability of Buildings: The Role of Non-Structural Elements. Structural Engineering International, 2020. 30(2): p. 217-223. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.C., et al., Performance-based seismic design framework for inertia-sensitive nonstructural components in base-isolated buildings. Journal of Building Engineering, 2021. 43. [CrossRef]

- Sisti, R., et al., Damage assessment and the effectiveness of prevention: the response of ordinary unreinforced masonry buildings in Norcia during the Central Italy 2016–2017 seismic sequence. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 2018. 17(10): p. 5609-5629. [CrossRef]

- O'Reilly, G.J., et al., Seismic assessment and loss estimation of existing school buildings in Italy. Engineering Structures, 2018. 168: p. 142-162. [CrossRef]

- Ottonelli, D., S. Cattari, and S.J.J.o.E.E. Lagomarsino, Displacement-based simplified seismic loss assessment of masonry buildings. 2020. 24(sup1): p. 23-59. [CrossRef]

- Cardone, D., G. Perrone, and A. Flora, Displacement-Based Simplified Seismic Loss Assessment of Pre-70S RC Buildings. Journal of Earthquake Engineering, 2020. 24(sup1): p. 82-113. [CrossRef]

- Cosenza, E., et al., The Italian guidelines for seismic risk classification of constructions: technical principles and validation. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 2018. 16(12): p. 5905-5935. [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, C., M.D. Ludovico, and A. Prota, Repair costs of reinforced concrete building components: from actual data analysis to calibrated consequence functions. Earthquake Spectra, 2020. 36(1): p. 353-377. [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, R.e.a. Shake Table Tests of Multiple Non-Structural Elements in a Low–Damage Structural Steel Building. 2019.

- Bianchi et al., Shake-table tests of innovative drift sensitive nonstructural elements in a low-damage structural system. International Association for Earthquake Engineering, 2021. 50(9): p. 22.

- Gerardo Araya-Letelier et al., Development and Testing of a Friction/Sliding Connection to Improve the Seismic Performance of Gypsum Partition Walls. Earthquake Spectra, 2019. 35(2). [CrossRef]

- Hakan Dilmac et al., The investigation of seismic performance of existing RC buildings with and without infill walls. 2018.

- Yön, B., Identification of failure mechanisms in existing unreinforced masonry buildings in rural areas after April 4, 2019 earthquake in Turkey. Journal of Building Engineering, 2021. 43. [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, H., et al., Seismic fragility assessment of nonstructural components in unreinforced clay brick masonry buildings. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics, 2019. 49(3): p. 285-300. [CrossRef]

- Lu, X. and S. Zha, Full-scale experimental investigation of the in-plane seismic performance of a novel resilient infill wall. Engineering Structures, 2021. 232. [CrossRef]

- KARAKALE, V., SEISMIC PERFORMANCE OF CLADDING SYSTEMS:EXPERIMENTAL WORK. 2019.

- Menichini, G., Seismic Response of Vertical Concrete Facade systems in reinforced concrete prefabricated buildings. 2020, University of Ljubljana Faculty of Civil and Geodetic Engineering: Italy.

- Nader, K.A.A., et al., Seismic evaluation of cladded exterior walls considering the effects of façade installation details and out-of-plane behavior of walls. Structures, 2020. 24: p. 317-334. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., et al., A Review on the Seismic Performance of Assembled Steel Frame-precast Concrete Facade Panels. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 2019. 690(1).

- Bedon, C., et al., Performance of structural glass facades under extreme loads – Design methods, existing research, current issues and trends. Construction and Building Materials, 2018. 163: p. 921-937.

- O’Hegarty, R., et al., High performance, low carbon concrete for building cladding applications. Journal of Building Engineering, 2021. 43. [CrossRef]

- Urbańska-Galewska, E., O. Zapała, and D. Wieczorek, Transparent façades – selection of construction materials with the use of modified multi-criteria spider’s network analysis method. MATEC Web of Conferences, 2018. 219.

- D'Angela, D., G. Magliulo, and E. Cosenza, Seismic damage assessment of unanchored nonstructural components taking into account the building response. Structural Safety, 2021. 93. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, S., J. Ciurlanti, and S. Pampanin, Comparison of traditional vs low-damage structural and non-structural building systems through a cost/performance-based evaluation. Earthquake Spectra, 2020. 37(1): p. 366-385. [CrossRef]

- VIGGIANI, L.R.S., Alternative techniques and approaches for improving the seismic performance of masonry infills. 2023.

- Sousa, L. and R. Monteiro, Seismic retrofit options for non-structural building partition walls: Impact on loss estimation and cost-benefit analysis. Engineering Structures, 2018. 161: p. 8-27. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, R.K. and D. D’Ayala, 2015 Nepal earthquake: seismic performance and post-earthquake reconstruction of stone in mud mortar masonry buildings. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 2020. 18(8): p. 3863-3896. [CrossRef]

- Memduh Karalar, M.Ç., Assessing of Earthquake Performance of Nonstructural Components Considering 2018 International Building Code 2020 GECE, Seoul, Korea. 2020.

- Chen, M.C., et al., Full-Scale Structural and Nonstructural Building System Performance during Earthquakes: Part I – Specimen Description, Test Protocol, and Structural Response. 2016. 32(2): p. 737-770.

- Pantoli, E., et al., Full-Scale Structural and Nonstructural Building System Performance during Earthquakes: Part II – NCS Damage States. Earthquake Spectra, 2016. 32(2): p. 771-794. [CrossRef]

- Filiatrault, A., et al., Performance-Based Seismic Design of Nonstructural Building Elements. Journal of Earthquake Engineering, 2018. 25(2): p. 237-269. [CrossRef]

- Steneker, P., et al., Integrated Structural–Nonstructural Performance-Based Seismic Design and Retrofit Optimization of Buildings. Journal of Structural Engineering, 2020. 146(8). [CrossRef]

- Merino, R.J., D. Perrone, and A. Filiatrault, Consistent floor response spectra for performance-based seismic design of nonstructural elements. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics, 2019. 49(3): p. 261-284. [CrossRef]

- Medina, H.A.a.R.A., Effects of Supporting Building Characteristics on Nonstructural Component Acceleration Demands. 2019.

- O’Reilly, G.J. and G.M. Calvi, A seismic risk classification framework for non-structural elements. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 2021. 19(13): p. 5471-5494. [CrossRef]

- Berto, L., et al., Seismic safety of valuable non-structural elements in RC buildings: Floor Response Spectrum approaches. Engineering Structures, 2020. 205. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, G.A., Y. Dong, and Y. Li, Performance-based decision-making of buildings under seismic hazard considering long-term loss, sustainability, and resilience. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering, 2020. 17(4): p. 454-470. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, W.M., et al., Seismic vulnerability and resilience of steel-reinforced concrete (SRC) composite column buildings with non-seismic details. Engineering Structures, 2021. 244. [CrossRef]

- Sheshov, V., et al., Reconnaissance analysis on buildings damaged during Durres earthquake Mw6.4, 26 November 2019, Albania: effects to non-structural elements. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 2021. 20(2): p. 795-817. [CrossRef]

- Filiatrault, A., et al., Effect of cyclic loading protocols on the experimental seismic performance evaluation of suspended piping restraint installations. International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping, 2018. 166: p. 61-71. [CrossRef]

- Memduh Karalar, M.Ç., Assessing 3D Earthquake Behaviour of Nonstructural Components Under Eurocode 8 Standard, in The 2020 Structures Congress (Structures20). 2020: Seoul, Korea.

- Nardin, C., et al., Experimental performance of a multi-storey braced frame structure with non-structural industrial components subjected to synthetic ground motions. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics, 2022. 51(9): p. 2113-2136. [CrossRef]

- Merino, R.J., D. Perrone, and A. Filiatrault, Appraisal of seismic design methodologies for suspended non-structural elements in Europe. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 2022. 20(15): p. 8061-8098. [CrossRef]

- Joyner, M.D. and M. Sasani, Building performance for earthquake resilience. Engineering Structures, 2020. 210. [CrossRef]

- Perrone, D., et al., Probabilistic estimation of floor response spectra in masonry infilled reinforced concrete building portfolio. Engineering Structures, 2020. 202. [CrossRef]

- Furtado, A., et al.,, A Review of the Performance of Infilled RC Structures in Recent Earthquakes. Applied Sciences, 2021. 11(13). 2021. [CrossRef]

- González, C., M. Niño, and G. Ayala, Functionality Loss and Recovery Time Models for Structural Elements, Non-Structural Components, and Delay Times to Estimate the Seismic Resilience of Mexican School Buildings. Buildings, 2023. 13(6). [CrossRef]

- B. Larson et al., Designing for whole of building resilience: A Case study of nonstructural elements in a viscous damped moment frame building. 2019.

- Morán-Rodríguez, S. and D.A. Novelo-Casanova, A methodology to estimate seismic vulnerability of health facilities. Case study: Mexico City, Mexico. Natural Hazards, 2017. 90(3): p. 1349-1375. [CrossRef]

- Heidari, M., N. Eskandary, and S.S. Miresmaeeli, The Challenge of Affordable Housing in Disasters: Western Iran Earthquake in 2017. Disaster Med Public Health Prep, 2020. 14(2): p. 289-291. [CrossRef]

- You, T., W. Wang, and Y. Chen, A framework to link community long-term resilience goals to seismic performance of individual buildings using network-based recovery modeling method. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, 2021. 147. [CrossRef]

- Pesaralanka, V., et al., Influence of a Soft Story on the Seismic Response of Non-Structural Components. Sustainability, 2023. 15(4). [CrossRef]

- Henry V. Burton et al., Integrating Performance Based Engineering and Urban Simulation to Model PostEarthquake Housing Recovery. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, G.A., Y. Dong, and M. Ouyang, Systems thinking approach to community buildings resilience considering utility networks, interactions, and access to essential facilities. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 2022. 21(1): p. 633-661. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, G.A., Y. Dong, and M.A. Khan, Long-term sustainability and resilience enhancement of building portfolios. Resilient Cities and Structures, 2023. 2(2): p. 13-23. [CrossRef]

- Asadi, E., A.M. Salman, and Y. Li, Multi-criteria decision-making for seismic resilience and sustainability assessment of diagrid buildings. Engineering Structures, 2019. 191: p. 229-246. [CrossRef]

- Freddi, F., et al., Innovations in earthquake risk reduction for resilience: Recent advances and challenges. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 2021. 60. [CrossRef]

- Asadi, E., et al., Risk-informed multi-criteria decision framework for resilience, sustainability and energy analysis of reinforced concrete buildings. Journal of Building Performance Simulation, 2020. 13(6): p. 804-823. [CrossRef]

- Joo, M.R. and R. Sinha, Nonstructural performance improvements for seismic resilience enhancement of modern code-compliant buildings, in Life-Cycle of Structures and Infrastructure Systems. 2023. p. 3888-3895.

- Gao, X. and P. Pishdad-Bozorgi, BIM-enabled facilities operation and maintenance: A review. Advanced Engineering Informatics, 2019. 39: p. 227-247. [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, J.P.S., et al., Probabilistic Assessment of the Life-Cycle Environmental Performance and Functional Life of Buildings due to Seismic Events. Journal of Architectural Engineering, 2018. 24(1). [CrossRef]

- Eskew, J., et al., An environmental Life Cycle Assessment of rooftop solar in Bangkok, Thailand. Renewable Energy, 2018. 123: p. 781-792. [CrossRef]

- Hajek, P., et al., BIM adoption towards the sustainability of construction industry in Indonesia. MATEC Web of Conferences, 2018. 195.

- Bojana et al., Life Cycle Assessment of Building Materials for a Single-family House in Sweden, in 10th International Conference on Applied Energy (ICAE2018). 2019, Energy Procedia: Hong Kong, China.

- Shahana Y. Janjua et al., A Review of Residential Buildings’ Sustainability Performance Using a Life Cycle Assessment Approach. Journal of Sustainability Research, 2019. 1(1). [CrossRef]

- Manjunatha, M., et al., Life cycle assessment (LCA) of concrete prepared with sustainable cement-based materials. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2021. 47: p. 3637-3644. [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y., et al., Reducing building life cycle carbon emissions through prefabrication: Evidence from and gaps in empirical studies. Building and Environment, 2018. 132: p. 125-136. [CrossRef]

- Fnais, A., et al., The application of life cycle assessment in buildings: challenges, and directions for future research. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 2022. 27(5): p. 627-654. [CrossRef]

- Hoxha, E., et al., Influence of technical and electrical equipment in life cycle assessments of buildings: case of a laboratory and research building. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 2021. 26(5): p. 852-863. [CrossRef]

- Yao, L., A. Chini, and R. Zeng, Integrating cost-benefits analysis and life cycle assessment of green roofs: a case study in Florida. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal, 2018. 26(2): p. 443-458. [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M., et al., Energy Efficient Buildings in the Industry 4.0 Era: A Review. 2023.

- Jayalath, A., et al., Life cycle performance of Cross Laminated Timber mid-rise residential buildings in Australia. Energy and Buildings, 2020. 223. [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, L.C.M., H. Birgisdóttir, and M. Birkved, Life cycle assessment of a Danish office building designed for disassembly. Building Research & Information, 2018. 47(6): p. 666-680. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Y., R. Raslan, and D. Mumovic, The life cycle carbon footprint of refurbished and new buildings – A systematic review of case studies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2018. 81: p. 231-241. [CrossRef]

- Altaf, M., et al., Evaluating the awareness and implementation level of LCCA in the construction industry of Malaysia. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 2022. 13(5). [CrossRef]

- Nwodo, M.N. and C.J. Anumba, A review of life cycle assessment of buildings using a systematic approach. Building and Environment, 2019. 162. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M., S. Allen, and D. Coley, Life cycle assessment in the building design process – A systematic literature review. Building and Environment, 2020. 185. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.M. and K.D. Tsavdaridis, Life cycle assessment (LCA) and cost (LCC) studies of lightweight composite flooring systems. Journal of Building Engineering, 2018. 20: p. 624-633. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., J. Wu, and H. Liu, Turning green into gold: A review on the economics of green buildings. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2018. 172: p. 2234-2245.

- Song, X., et al., Life Cycle Assessment of Geotechnical Works in Building Construction: A Review and Recommendations. Sustainability, 2020. 12(20). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Y. Liu, and S. Shen, Review on building life cycle assessment from the perspective of structural design. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 2021. 20(6): p. 689-705. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, H., et al., Reducing cooling load and lifecycle cost for residential buildings: a case of Lahore, Pakistan. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 2021. 26(12): p. 2355-2374. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.U., et al., Circular economy and the construction industry: Existing trends, challenges and prospective framework for sustainable construction. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2020. 130.

- Hwang, B.-G., M. Shan, and J.-M. Lye, Adoption of sustainable construction for small contractors: major barriers and best solutions. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 2018. 20(10): p. 2223-2237. [CrossRef]

- Potrč Obrecht, T., et al., BIM and LCA Integration: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 2020. 12(14).

- Altaf, M., et al., Optimisation of energy and life cycle costs via building envelope: a BIM approaches. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S., U.I. Raniga, and S. Misra, A Methodological Framework for Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment of Construction Projects Incorporating TBL and Decoupling Principles. Sustainability, 2021. 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Goel, A., Social sustainability considerations in construction project feasibility study: a stakeholder salience perspective. Emerald Insight, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Goel, A., L.S. Ganesh, and A. Kaur, Project management for social good. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 2020. 13(4): p. 695-726.

- Santarelli, S., G. Bernardini, and E. Quagliarini, Earthquake building debris estimation in historic city centres: From real world data to experimental-based criteria. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 2018. 31: p. 281-291. [CrossRef]

- Amini Hosseini, K. and Y.O. Izadkhah, From “Earthquake and safety” school drills to “safe school-resilient communities”: A continuous attempt for promoting community-based disaster risk management in Iran. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 2020. 45.

| Functionality level | ATC-20 placard | Utilities | Damage | Description |

| None | None (not yet inspected) | Not applicable | Potentially significant | The building has not been inspected but has been damaged and evacuated |

| Restricted entry | Unsafe (red) | Not applicable | Significant, requiring repair or demolition | The building is not safe to occupy or enter, except as authorized by the local jurisdiction |

| Restricted use | Restricted use (yellow) | Not applicable | Moderate to significant, requiring repair | Parts of the building are not safe to enter or occupy |

| Re-occupancy | Inspected (green) | Unavailable | Minor, requiring repair | The building is safe to occupy but does not have access to utilities |

| Baseline | Inspected (green) | Critical ones available | Cosmetics, requiring repair | The building is safe to occupy and has access to critical utilities |

| Full | Inspected (green) | All available | None | The building is safe to occupy and has access to all utilities |

| S. No | Method of Analysis | Description | SE’s & NSE’s | Limitation |

| 1 | Standard Reliability | For each ground motion record, the maximum response selected | Overall Reliability estimation not considered | No information about the damage location effect. Only valid for Steel MRF upto 15 stories |

| 2 | Story Wise Reliability Approach | Reliability for each floor considered separately and then the minimum value used for the complete building | Overall Reliability estimation not considered | Only valid for Steel MRF upto 15 stories |

| 3 | Block Diagram Reliability Approach | Set of Parallel and series components considered | Overall Reliability estimation considered |

| Damage State | Median Capacity IDIDS (%) |

Log SD of Capacity ΒDS |

Sub-DS | Damage Description | |

| Structural | SDS1 | 2 | 0.4 | --- | Beams or joints exhibit residual crack widths > 0.06 in |

| SDS2 | 2.75 | 0.3 | --- | No significant spalling; no fracture or buckling of reinforcing Spalling of cover concrete exposes beam and joint transverse reinforcement but not longitudinal reinforcement. No fracture or buckling of reinforcing | |

| SDS3 | 5 | 0.3 | SDS31 (20%) |

No significant spalling; no fracture or buckling of reinforcing Spalling of cover concrete exposes beam and joint transverse reinforcement but not longitudinal reinforcement. No fracture or buckling of reinforcing | |

| SDS32 (80%) | Spalling of cover concrete exposes a significant length of beam longitudinal reinforcement; crushing of core concrete may occur; Fracture or buckling of reinforcing may occur. Also, 20% of cases will trigger an unsafe placard. | ||||

| Nonstructural | PDS1 | 0.5 | 0.4 | --- | Partitions: Screw pop-out, cracking of wallboard, warping or cracking of tape, slight crushing of wall panel at corners. |

| PDS2 | 1 | 0.3 | --- | Partitions: Moderate cracking or crushing of gypsum wall boards (typically in corners); Moderate corner gap openings, bending of boundary studs | |

| PDS3 | 2.1 | 0.2 | --- | Partitions: Buckling of studs and tearing of tracks; tearing or bending of the top track, tearing at corners with transverse walls, large gap openings, walls displaced |

|

| CDS1 | 2.7 | 0.3 | --- | Curtain wall: Gasket seal failure | |

| CDS2 | 2.76 | 0.3 | --- | Curtain wall: Glass cracking | |

| CDS3 | 3.03 | 0.3 | --- | Curtain wall: Glass falls from frame | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).