1. Introduction

Down syndrome (DS) or trisomy 21 represents the most frequent chromosomal alteration in live births. The current prevalence is estimated to be 1.44 per 1000 live births in the United States [

1]. There are several comorbidities that contribute to a significantly shorter life expectancy compared to the general population, however, respiratory failure, pneumonia, heart failure are the risk factors identified for in-hospital mortality.

This susceptibility to infections is generally considered to be multifactorial in origin and is related to both impaired immune function and non-immunological factors.

In adult patients, the immune disorders underlying increased susceptibility to respiratory infections are poorly understood [

2].

Similarly, there are few studies describing the pathogens most involved in the etiology of pneumonia in patients with DS.

In a 2020 review Santoro reports that the specific infectious etiology of pneumonia was provided in only one article and did not show a coherent pathogen but rather a variety of causes [

3]. The identification of the specific infectious etiology could have important implications on prevention, choice of therapy and identification of the underlying risk factor.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a double-stranded DNA virus and a member of the Herpesviridae family. CMV is widely considered to be an infectious pathogen responsible for life-threatening community-acquired pneumonia in immunosuppressed patients, for example, transplant recipients and those taking immunosuppressive drugs or steroids, and is characterized by respiratory distress, dyspnea, and cough. Similarly, in adults with DS, cytomegalovirus pneumonia could be a complication of CMV disease favored by immune disorders.

CMV is commonly detected by viral isolation, rapid culture of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, and quantification of CMV DNA in BAL fluid. There are no studies on the prevalence and severity of cytomegalovirus pneumonia in subjects with DS.

We present the case of a 50-year-old patient with Down syndrome and renal failure who arrived at our intensive care unit with severe ARDS, after having been initially treated at home with empiric antibiotic therapy and subsequently in the medical department of another hospital with antibiotics and antifungals for bilateral pneumonia.

2. Case presentation

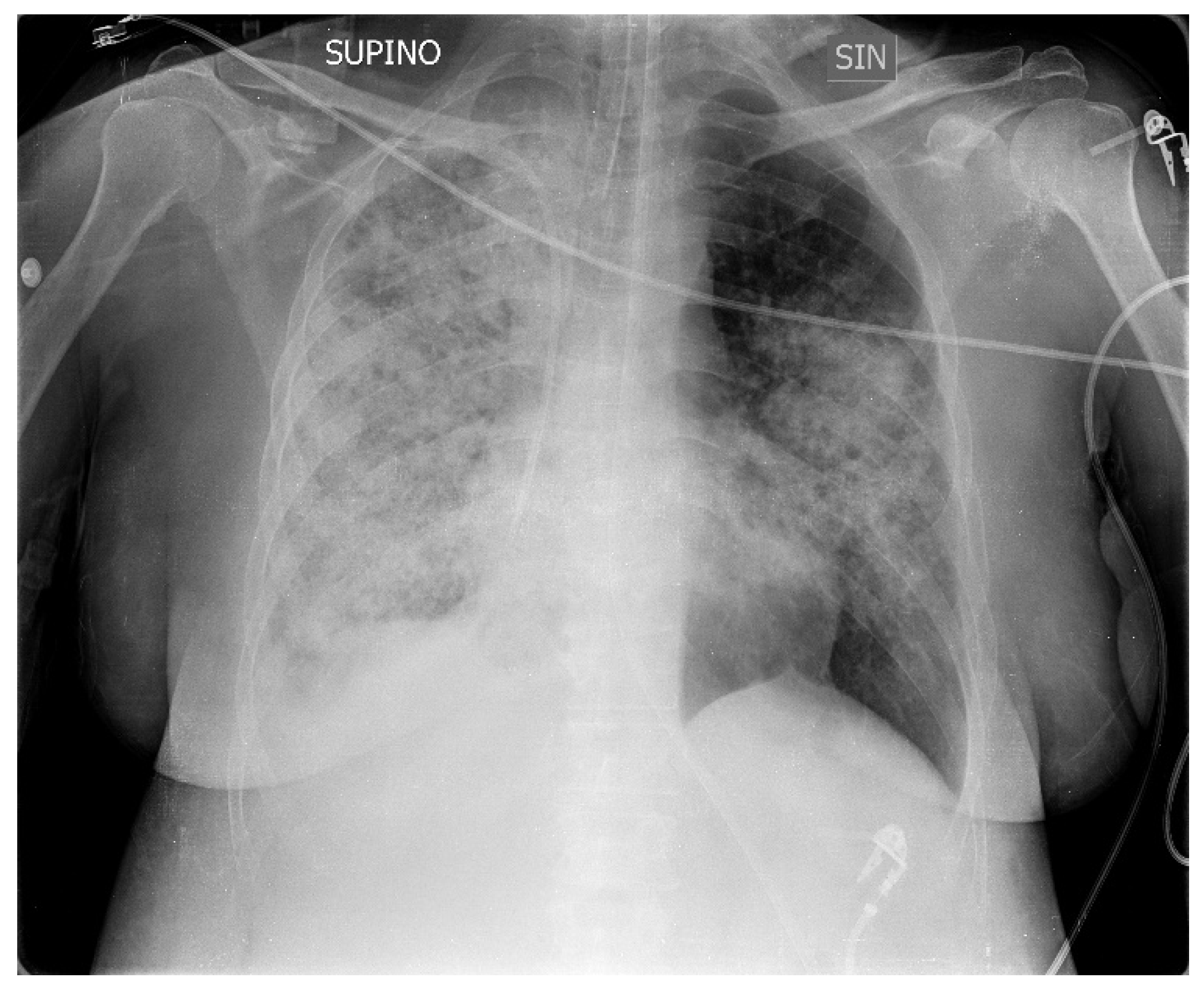

A 50-year-old patient suffering from Down syndrome came to our ED with fever (38 °C), severe respiratory failure, tachypnea and dyspnea, a SpO2 of 82%, sinus tachycardia, and blood pressure of 105/63, and a picture of bilateral pneumonia in the ‘X-ray of the chest with greater involvement of the right lung (

Figure 1) The patient came from the medical department of another hospital and the symptoms had started about 10 years ago with cough and low-grade fever. After seven days of home therapy with ceftriaxone and azithromycin for worsening symptoms, she was admitted to hospital with the diagnosis of bilateral interstitial pneumonia. Here, empiric therapy with meropenem, linezolid and caspofungin was started and supplemental oxygen was required.

After approximately 36 hours, due to the worsening of her clinical conditions, she was transferred to our emergency room where she arrived in the clinical conditions previously described. His medical history described renal failure, there was no history of a previous cytomegalovirus infection, and he was in good hemodynamic compensation.

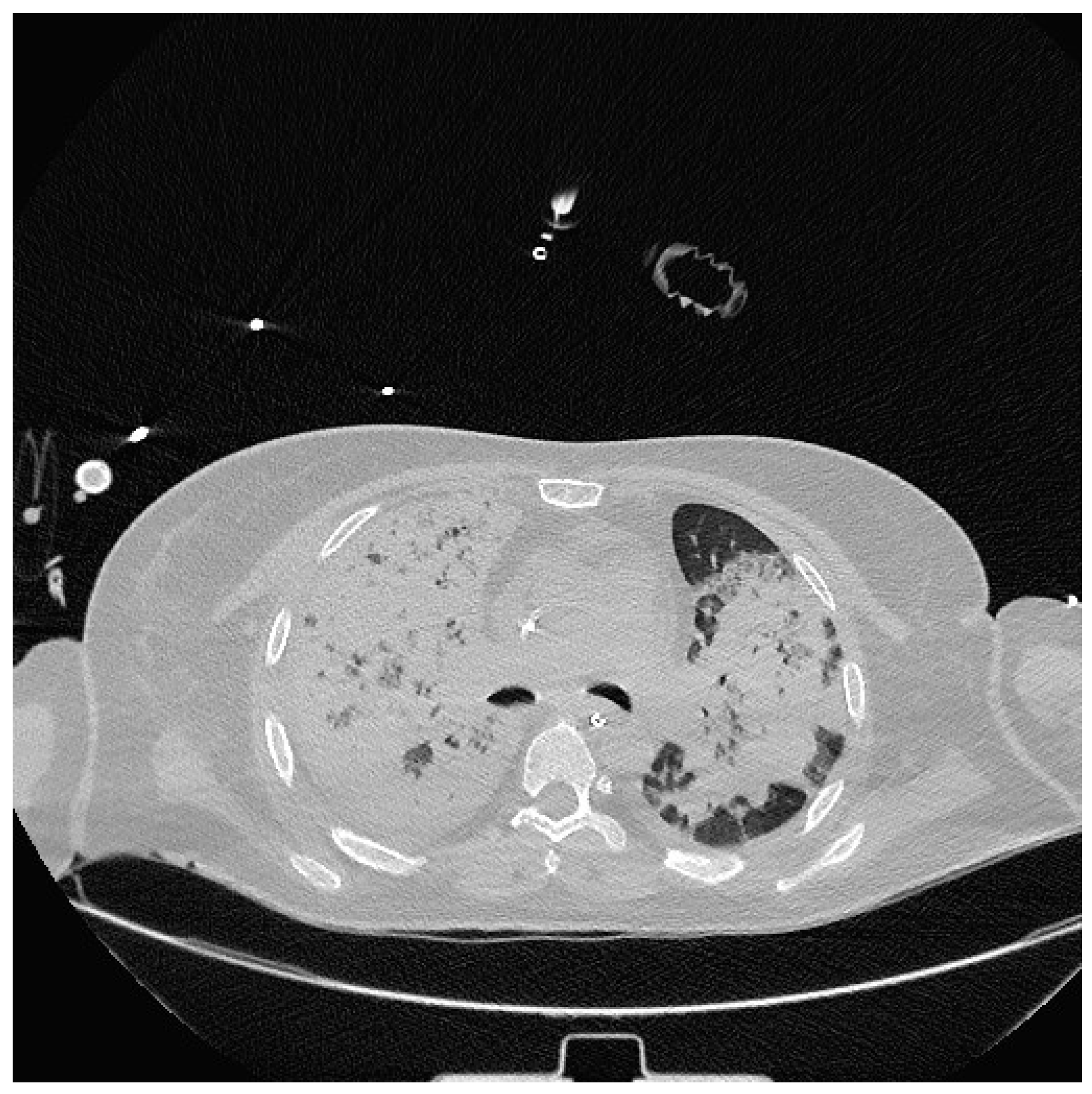

Severe hypoxia despite supplemental oxygen and respiratory distress required orotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation in the emergency room. A chest CT scan was then performed which showed extensive consolidation of the right lung and subtotal consolidation of the left lung. (

Figure 2).

Upon admission to the Intensive Care Unit, blood tests showed leukocytosis (16,060 cells/μL), C-reactive protein (22.32 mg/dL), procalcitonin 3.22, as well as the presence of anemia (Hb 10 g/dl) with vitamin B12 deficiency (81 pg/ml), renal failure (creatinine 1.63, GFR 36.4).

Urine samples were negative for Legionella and Streptococcus pneumoniae antigens.

The antibiotic and antifungal therapy with meropenem, linezolid and caspofungin, which had begun approximately 36 hours earlier at another hospital, was continued.

Fibro-bronchoscopy was performed which highlighted a hyperemic tracheo-bronchial mucosa and absence of tracheo-bronchial secretions and, at the same time, a broncholavage (BAL) was sent to bacteriology for molecular diagnostics with Film-array of the lower respiratory tract, for phenotypic culture examination and for the research for Galactomannan.

No organisms were detected in blood cultures, BAL cultures, or microscopy. The PCR tests were negative for galactomannan and for the presence of Pneumocystis jirovecii, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, herpes simplex and syncytial viruses, Sars CoV 2, Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

In consideration of the clinical history, and the poor response to the ongoing therapy, with persistence of hypoxia, a second BAL was performed 48 hours after the first to search for cytomegalovirus DNA (CMV -DNA) which gave a positive result but with a low load (300 copies/ml); 2.4 log CMV DNA.

Ganciclovir therapy was therefore started at the correct dosage for renal function indices

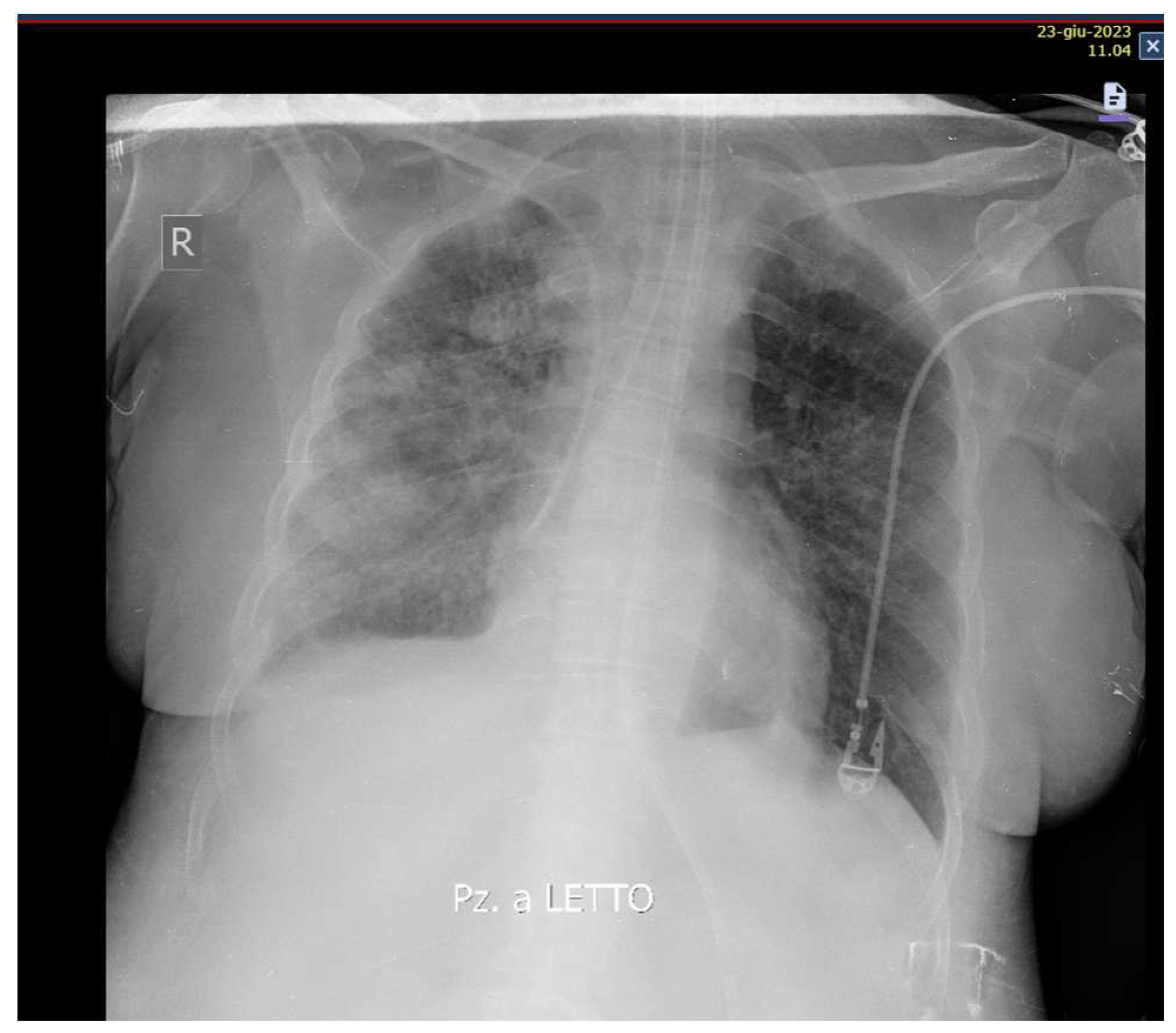

After 48 hours of therapy with Ganciclovir, a reduction in inflammation indices was observed: C-reactive protein 3.43, WBC 14000, Procalcitonin 0.49.

Likewise, an improvement in respiratory exchanges and radiological images was observed (

Figure 3).

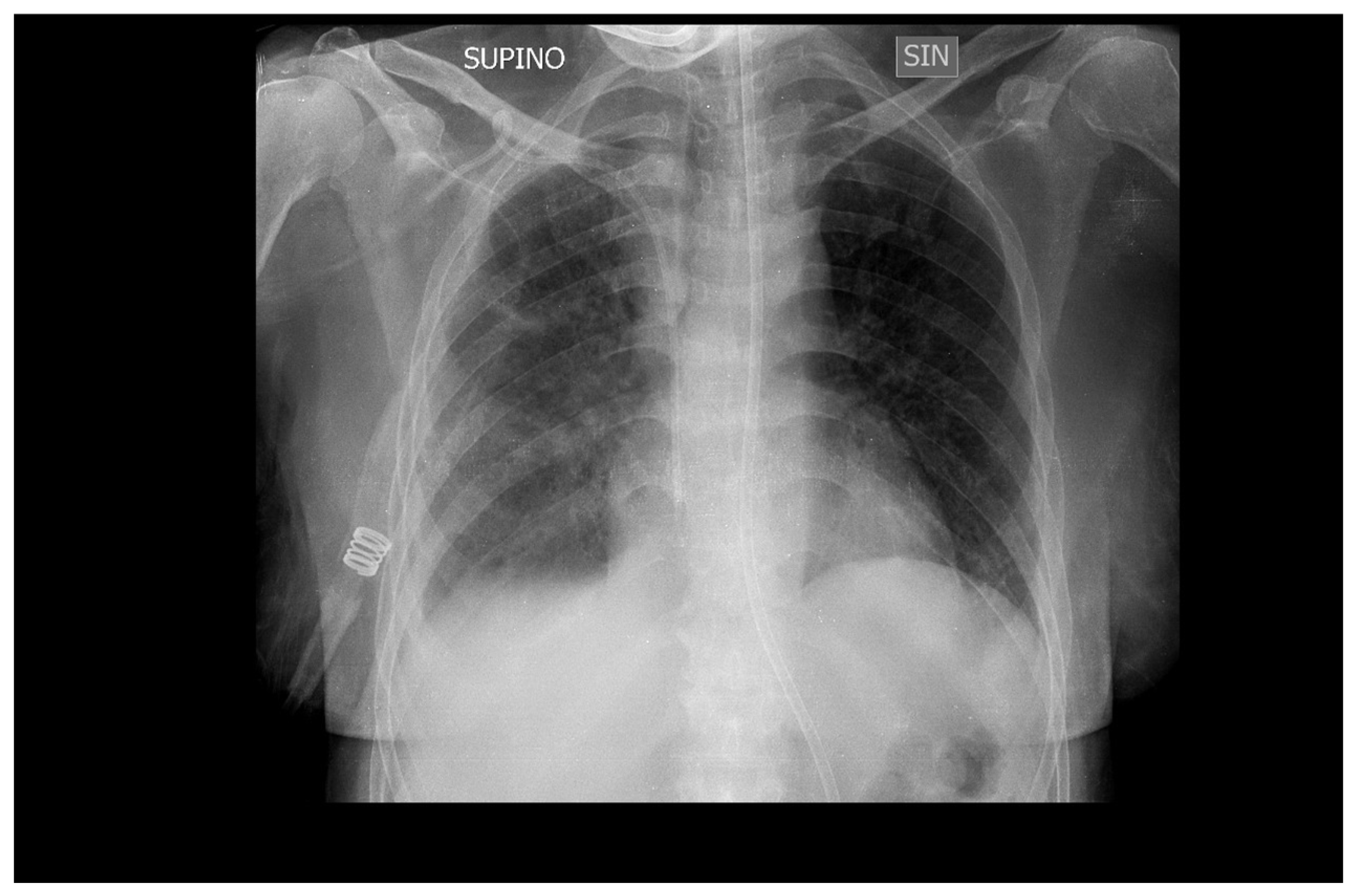

Mechanical ventilation was stopped after 10 days (

Figure 4) and the patient was transferred to the medical department where she continued therapy with Ganciclovir for another two weeks before being discharged to her home.

3. Discussion

In this study we described the case of an adult patient with DS with a severe form of bilateral pneumonia and a BAL positive for CMV-DNA. CMV is widespread and can be commonly found in BAL fluid samples from asymptomatic people.

Cytomegalovirus pneumonia is a rare but life-threatening complication of CMV disease. Various clinical conditions have been associated with a high risk of HCMV infection leading to interstitial lung disease. Pneumonia is the most common manifestation of HCMV infection in hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients with high mortality rates [

4,

5]. Similarly, solid organ transplant recipients are at high risk of contracting HCMV pulmonary infection [

6,

7]. Despite antiviral prophylaxis, HCMV pneumonia can occur after lung transplantation and is associated with poor outcome [

8]. HCMV pulmonary infection is also a common disease of HIV-infected patients [

9], and HCMV pneumonia may be the first manifestation of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) [

10].

Interestingly, all of the aforementioned high-risk groups for HCMV pneumonia show impaired T-cell immunity, already indicating a relevant role for this type of immune cell.

However, rare cases of HCMV pneumonia have been observed in immunocompetent patients, implying that virus-encoded pathogenicity determinants may also cause lung disease [

11,

12,

13].

In CMV pneumonia, symptoms are nonspecific and include dry cough, dyspnea, dyspnea on exertion, and fever [

14]. Radiological findings in HCMV pneumonia are also rather nonspecific and include diffuse interstitial infiltrates on chest radiography and ground-glass opacities, small nodules, and others on computed tomography [

15]. Clinical and radiological images are therefore nonspecific and typical of other forms of interstitial pneumonia, which may lead to delays in the diagnosis of cytomegalovirus pneumonia [

16].

The diagnosis of HCMV pneumonia should be performed by a combination of serological testing together with the detection of virus DNA in blood and/or bronchoalveolar lavage specimens. Lung biopsy may allow direct detection of HCMV infection via immunohistopathology.

One study demonstrated that a cutoff value of CMV DNA levels >500 IU/mL in BAL fluid can be used to differentiate between CMV pneumonia and lung contamination with a positive predictive value of 45% [18]. In our case the concentration on BAL was found to be 300 copies/ml) and 2.4 log CMV DNA.

To date, there are no studies that have described the prevalence and severity of CMV pneumonia in adult patients with DS

Pneumonia disproportionately affects people with DS throughout life, starting in childhood, and represents an important cause of mortality.

In fact, it is known that patients suffering from Down syndrome have an increased risk of having severe pneumonia with the need for hospitalization, admission to intensive care and mechanical ventilation [19].

Overall, the risk of dying from an infection is 12 times higher in patients with DS than in individuals without DS [21].

People with DS have a greater susceptibility to infections, especially respiratory ones, due to anatomical anomalies of the airways, the presence of gastro-esophageal reflux and immune system disorders. For this reason, all vaccinations are strongly recommended to reduce the risk of infections and their complications.

However, the articles in the literature have not provided data to explain why the prevalence and severity of pneumonia and respiratory infections are increased in DS and the cause could be multifactorial.

Immune disorders in DS remain poorly understood, vary from individual to individual and have been alternatively interpreted as premature aging or an intrinsic defect of the immune system [20].

Several genes of chromosome 21 are involved in immune function (ITGβ2, IFNAR1, IFNGR2 and ICOSL, etc.), but their overexpression has not been demonstrated [22]. Many other epigenetics-related genes are encoded on this chromosome, which could alter the expression and immune function of B or T cells [23].

Inadequate vaccine responses and reduced levels of IgG2 or IgG4 are suggestive of a primary antibody deficiency. The proportions of B cell populations resemble models of common variable immunodeficiency, a condition that includes a heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by significant hypogammaglobulinemia of unknown origin, inability to produce specific antibodies after immunization and susceptibility to bacterial infections, particularly by capsulated bacteria [24,25].

Research to evaluate the efficacy of Immunoglobulin G for routine clinical use in the treatment of CMV pneumonia and other pathogens in patients with Down syndrome could be considered.

There are also knowledge gaps regarding the identification of responsible infectious organisms and the lack of data on the prevention and screening of risk factors for pneumonia.

Studies of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection in individuals with DS have shown increased prevalence and severity, by need for hospitalization and length of hospitalization, compared to non-DS controls [26].

Given the increased prevalence and severity of lung infections compared to controls, it is important to remain vigilant about potential CMV etiology to timely diagnose, treat, and prevent pneumonia in individuals with DS.

Regarding the prevention of respiratory infections, two vaccines for respiratory syncytial virus have recently been approved and it could be useful to consider universal administration to all patients with DS.

In this case the patient initially treated with antibiotics and antifungals without success was subsequently treated with Ganciclovir approximately 10 days after the onset of symptoms after isolation of CMA-DNA in the BAL.

Likewise given the disease burden associated with pneumonia in patients with DS and the deficit in knowledge of causative agents, further studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of vaccination and vaccine strategies to prevent pneumococcal pneumonia in children and adults with DS, as well as damages and costs [27,28].

A vaccine to prevent congenital CMV infection is in development. Currently, the best way to limit the risk of contagion is careful personal hygiene, especially for the categories of people most vulnerable to the disease.

4. Conclusions

This case aims to highlight that CMV pneumonia in individuals with DS can be a life-threatening condition. It also clarifies the importance of early diagnosis of infections from opportunistic pathogens such as CMV to ensure timely and efficient treatment.

The greater susceptibility to developing serious pulmonary conditions could have a multifactorial etiology which includes the presence of immune disorders that are not yet well defined, especially in adulthood.

There is an urgent need for further research studies on DS, guiding options for prevention and studying the etiology of pneumonia and lifelong respiratory infections, as the main cause of death in DS.

References

- DISCERN-Genetics: quality criteria for information on genetic testing. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 14, 1179–1188. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alan, H.; Carol Bower, B.; Emma, R.H.; Glasson, J. The four ages of Down syndrome. Eur. J. Public Health 2007, 17, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, S.L.; Chicoine, B.; Jasien, J.M.; Kim, J.L.; Stephens, M.; Bulova, P.; Capone, G. Pneumonia and respiratory infections in Down syndrome: A scoping review of the literature. Am. J. Med Genet. Part A 2020, 185, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, G.M.; Horak, D.A.; Niland, J.C.; Duncan, S.R.; Forman, S.J.; Zaia, J.A. A randomized, controlled trial of prophylactic ganciclovir for cytomegalovirus pulmonary infection in recipients of allogeneic bone marrow transplants; The City of Hope-Stanford-Syntex CMV Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 1005–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeckh, M.; Ljungman, P. How we treat cytomegalovirus in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Blood 2009, 113, 5711–5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishman, J.A. Infection in solid-organ transplant recipients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2601–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, R.B., Jr.; Rowlands, D.T., Jr.; Rifkind, D. Infectious Pulmonary Disease in Patients Receiving Immunosuppressive Therapy for Organ Transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1964, 271, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, L.D.; Finlen-Copeland, C.A.; Turbyfill, W.J.; Howell, D.; Willner, D.A.; Palmer, S.M. Cytomegalovirus pneumonitis is a risk for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome in lung transplantation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 181, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, J.M.; Hannah, J. Cytomegalovirus pneumonitis in patients with AIDS. Findings in an autopsy series. Chest 1987, 92, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczawinska-Poplonyk, A.; Jonczyk-Potoczna, K.; Ossowska, L.; Breborowicz, A.; Bartkowska-Sniatkowska, A.; Wachowiak, J. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia as the first manifestation of severe combined immunodeficiency. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014, 39, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, B.A.; Pherez, F.; Walls, N. Severe cytomegalovirus (CMV) community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in a non immunocompromised host. Heart Lung 2009, 38, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grilli, E.; Galati, V.; Bordi, L.; Taglietti, F.; Petrosillo, N. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia in immunocompetent host: Case report and literature review. J. Clin. Virol. 2012, 55, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goncalves, C.; Cipriano, A.; Videira Santos, F.; Abreu, M.; Mendez, J.; Sarmento, E.C.R. Cytomegalovirus acute infection with pulmonary involvement in an immunocompetent patient. IDCases 2018, 14, e00445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafailidis, P.I.; Mourtzoukou, E.G.; Varbobitis, I.C.; Falagas, M.E. Severe cytomegalovirus infection in apparently immunocompetent patients: A systematic review. Virol. J. 2008, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, J.H.; Kim, E.A.; Lee, K.S.; Kim, T.S.; Jung, K.J.; Song, J.H. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia: High-resolution CT findings in ten non-AIDS immunocompromised patients. Korean J. Radiol. 2000, 1, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restrepo-Gualteros, S.M.; Gutierrez, M.J.; Villamil-Osorio, M.; Arroyo, M.A.; Nino, G. Challenges and Clinical Implications of the Diagnosis of Cytomegalovirus Lung Infection in Children. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2019, 21, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinana, J.L.; Gimenez, E.; Gomez, M.D.; Perez, A.; Gonzalez, E.M.; Vinuesa, V.; Hernandez-Boluda, J.C.; Montoro, J.; Salavert, M.; Tormo, M.; et al. Pulmonary cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA shedding in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: Implications for the diagnosis of CMV pneumonia. J. Infect. 2019, 78, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeckh, M.; Stevens-Ayers, T.; Travi, G.; Huang, M.L.; Cheng, G.S.; Xie, H.; Leisenring, W.; Erard, V.; Seo, S.; Kimball, L.; et al. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA quantitation in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients with CMV pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, 1514–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uppal, H.; Chandran, S.; Potluri, R. Risk factors for mortality in Down syndrome: Risk factors for mortality in down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 2015, 59, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, D.A.; Gridley, G.; Cnattingius, S.; Mellemkjaer, L.; Linet, M.; Adami, H.O.; et al. Mortality and cancer incidence among individuals with Down syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2003, 163, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusters, M.A.; Verstegen, R.H.; Gemen, E.F.; de Vries, E. Intrinsic defect of the immune system in children with Down syndrome: a review. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009, 156, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcovecchio, G.E.; Bortolomai, I.; Ferrua, F.; Fontana, E.; Imberti, L.; Conforti, E.; et al. Thymic epithelium abnormalities in DiGeorge and Down syndrome patients contribute to dysregulation in T cell development. Front Immunol. 2019, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satgé, D.; Seidel, M.G. The pattern of malignancies in Down syndrome and its potential context with the immune system. Front Immunol. 2018, 9, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verstegen, R.H.J.; Driessen, G.J.; Bartol, S.J.W.; van Noesel, C.J.M.; Boon, L.; van der Burg, M.; et al. Defective B-cell memory in patients with Down syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014, 134, 1346–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carsetti, R.; Valentini, D.; Marcellini, V.; Scarsella, M.; Marasco, E.; Giustini, F.; et al. Reduced numbers of switched memory B cells with high terminal differentiation potential in Down syndrome. Eur J Immunol. 2015, 45, 903-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagliano, D.R.; Nylund, C.M.; Eide, M.B.; Eberly, M.D. Children with Down syndrome are high-risk for severe respiratory syncytial virus disease. J Pediatr 2015, 166, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusters, M.A.A.; Manders, N.C.C.; de Jong, B.A.W.; van Hout, R.W.N.M.; Rijkers, G.T.; de Vries, E. Functionality of the pneumococcal antibody response in Down syndrome subjects. [CrossRef]

- Nurmi, T.; Leinonen, M.; Häivä, V.M.; Tiilikainen, A.; Kouvalainen, K. Antibody response to pneumococcal vaccine in patients with trisomy-21 (Down’s syndrome).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).