1. Introduction

The performance of rolling bearing systems, as well as the life, load capacity, vibration level, noise, running accuracy, stiffness, depend on the geometry of the bearing, including the diametrical clearance, the materials that make up the parts, hardness of contacting surfaces and the load distribution of the external load. This work deals with radial external load distribution on rolling elements of ball and cylindrical roller bearings. It is assumed that the rings and the rolling elements are made of the same material (steel) and that the rings are rigid, that is, the only deformations considered are hertzian elastic deflections located at the lines- and points-contact between rolling elements and the raceways.

Stribeck [

1] investigated the load distribution on rolling elements of a radially loaded ball bearing and found that the

maximum ball load could be obtained by multiplying the

medium external load by 4.37, for zero internal clearance. This number came to be known as Stribeck’s Constant or Number and, to account for nonzero diametrical clearance and other effects, Stribeck recommended rounding the Constant to 5.0.

An integral method for load distribution calculation in bearings was proposed by Sjövall [

2]. The relationship between the maximum loaded rolling element load and the bearing external load was established using Sjövall’s integrals.

Palmgren [

3] stated that the theoretical value of Stribeck's Constant for roller bearings with zero internal clearance is 4.08 and suggested using Stribeck's recommended value of 5.0 for the Stribeck’s Constant for either ball or roller bearings having typical clearance.

Ricci [

4] showed how the Stribeck’s Constants were found. It’s also shown that the error when adopting the value 4.08 for roller bearing Stribeck’s Constant is 55.6 times greater than when adopting the value 4.37 for the ball bearing Stribeck’s Constant.

Jones [

5] applied Hertz's theory of contact stresses of Hertz [

6] and derived an expression to determine the parameters for load distribution on rolling elements in the form of a system of nonlinear equations. To solve these equations he recommended the Newton-Raphson iterative method. Harris [

7] later applied Jones' model to his own work.

Concerning with excentric thrust load in a thrust bearing, Rumbarger [

8] gives values for axial and moment Sjövall’s integrals,

Ja(

ε) and

Jm(

ε), respectively, as functions of excentricity loading,

e, and pitch diameter,

dm, where

ε is the load distribution factor. Ricci [

9] used Newton-Raphson's method to obtain results for a single row angular contact ball bearing subjected to an eccentric thrust loading.

Houpert [

10] improved Sjövall’s integrals for multi-degree-of-freedom bearing system.

A comprehensive mathematical model of bearings was developed by Harris [

7], which described methods for internal loading distribution in statically loaded bearings addressing pure radial; pure thrust (centric and eccentric loads); combined radial and thrust load, using radial and thrust Sjövall’s integrals’ approximations; and for ball bearings under combined radial, thrust, and moment load, initially due to Jones [

11]. The load zone was described by the load distribution factor,

ε, and the contact stress-strain relationship between the ring and any rolling element was achieved. The load distribution can be obtained by continuous iteration procedure. However, studies have shown [

12] that the results obtained by the Harris [

7] method can’t rigorously satisfy the static balance. Pointing out that the problem of obtaining the load distribution in bearings with arbitrary radial clearance is to determine the number of rolling elements that participate in the transfer of the external radial load.

A new approach in the mathematical modeling of rolling bearings was developed [

12,

13]. The approach considers two boundary cases of inner ring support on an even and/or odd number of rolling elements. In relation to these boundary conditions, Tomović derived the general equations for the calculation of the boundary deflection and internal radial load values, which are necessary for the inner ring support on a finite number of rolling elements.

Research has shown that ball bearings should have slightly negative or zero internal clearance to maximize bearing life and reliability. However, zero or slightly negative clearance generates high contact stresses between raceways and balls [

14,

15]. In addition, it increases bearing friction, which makes the bearing vulnerable to temperature rise. Therefore, a bearing with positive diametrical clearance is generally chosen to avoid such problems [

16].

Ref. [

14] investigated the effect of internal clearance on load distribution and fatigue life of radially loaded deep groove ball bearings. They found that life gradually decreases with increasing clearance’s absolute value and is maximum under small negative clearance. Furthermore, in radially loaded bearings, the rolling elements, which transfer the load – active elements –, are located below the meridian plane in the so-called

loading zone. The quasi-static analysis to derive the radial load distribution is based on the assumption that the inner ring, under load, moves radially in the direction of the external load, with respect to the outer ring, which rings are considered rigid.

Ref. [

15] developed a mathematical model based on the Hertz elastic contact theory to determine the radial load distribution in ball bearings with positive, negative and zero clearance.

Considering two different distributions of the balls in relation to the load line, Ref. [

16] obtained a better load distribution in ball bearings under the influence of the relative motion between the rings in the presence of radial clearance.

Ref. [

17] proposed a model to study the load distribution in a ball bearing as a preload’s function. Preload means negative radial internal clearance. The new model is then used to calculate fatigue life as a function of external load, rotational speed and preload. The results show that adequate preload improves load distribution and prolongs fatigue life. Given load and rotational speed, an optimal preload can be obtained, estimated through the life of the bearing.

Ref. [

18] proposed a method to correct the Sjövall integral or Harris integral for the radial load distribution in radial bearings, since the sum of the vertical components of the calculated rolling element loads is not equal to the external radial load [

12,

15,

19]. The comparison between the results obtained from the corrected radial load distribution integral and the Harris integral shows the higher accuracy and superiority of the corrected radial load distribution integral.

Ref. [

20] investigated the effect of load distribution on bearing life, both theoretically and experimentally, using several housing models which provide different contact conditions between the housing bore and the outer ring. The results of the tests have substantiated that the bearing life is substantially affected by the load distribution; moreover, it has been shown that there is a linear factor between the calculated lives and the experimental ones.

Ref. [

21] proposed a mathematical method for rolling bearings stiffness calculation based on Hertz elastic contact theory, where two boundary positions of the inner ring supported by even or odd number of rolling elements are considered. The effect of bearing parameters including internal clearance and number of rolling elements on the fluctuation of radial stiffness and oscillation of rotor’s center has been systematically investigated for ball and roller bearings.

Ref. [

22] proposed an improved analytical model to study vibrations in a roller bearing caused by different edge shapes of LOcalized Defects (LOD) in raceways. The numerical results show that the amplitude and impulse waveform of the accelerations of the roller bearing is affected by the LOD edge shape and lubricated oil; however, the peak frequencies in the spectrum are slightly influenced by the LOD edge shape and lubricated oil. It seems that the presented numerical results can give some guidance for the incipient LOD detection and diagnosis for roller bearings.

Ref. [

23] proposed a new 12 DOF dynamics model for a rigid Rotor Bearing System (RBS), which can formulate the housing support stiffness, interfacial frictional moments including load dependente and load independent components, Time-Varying Displacement Excitation (TVDE) caused by a LOD, additional deflections at the sharp edges of the LOD, and lubricating oil film. The results show that the model can provide a more accurate modeling method for predicting the vibration characteristics of the rigid RBSs.

Ball bearing clearance influences starting torque, bearing stiffness and affects load distribution, load carrying capacity and bearing life. Ref. [

24] calculated the radial load distribution in a deep groove ball bearing with variable clearance - which is obtained by constructing the outer ring’s groove in an elliptical shape - and the results shown that the load distribution is better when compared to the conventional bearing, for |

θ| <

π/4, where

θ is the angle between the load line and the major axis of the elliptical outer groove.

There are two basic methods for radial external load distribution determination on rolling elements, which participate in the load transfer between rings in a rolling element bearing. There is a discrete method, where the radial external load, the diametrical clearance, the load-deflection relationships at the rolling elements-race contacts are known and assuming that the rolling elements are symmetrically and evenly distributed with respect to the radial external load direction, the rolling elements normal loads, the relative radial displacement between rings or the deflection at maximum loaded rolling element can be obtained by numerically satisfying the static equilibrium equation, which requires that the applied load must be equal to the sum of the rolling elements loads components parallel to the direction of the applied load.

There is a second method - integral method -, where the rolling element normal load equivalent to a rolling element-race elastic hertzian contact deflection equal to the relative displacement between the rings can be given by multiplying the reciprocal of an integral factor and the applied external radial load averaged. Equivalently, the maximum rolling element normal load of the bearing can be given by multiplying the reciprocal of a second integral factor and the applied external radial load averaged.

The integral methods described in the literature for normal rolling elements load distribution in a rolling bearing under radial external load require the integration, around the load zone, of a trigonometric function, which the cosine of the loading zone azimuth angle is the parameter – the Sjövall radial integral. This integral can be reduced to a standard elliptical integral by the hypergeometric series and the beta function, requiring reasonable theoretical effort. In applications, a numerical evaluation of the integral is used, therefore, an approximation of the exact solution.

The method described in this work obtain numerically the shift between rings – or the maximum elastic hertzian deflection at race-rolling element contacts - and, therefore, the normal rolling elements loads, using a single iterative numerical based Newton-Rhapson equation; and it was found that the method described in this work obtain results as accurate as, or even more accurate than the methods described in the literature, with little theoretical and computational effort. Then, in this work is described a simple, accurate numerical iterative Newton-Raphson based method for internal load distribution computation in statically loaded, single-row, deep grove, angular-contact ball bearings or cylindrical roller bearings, subjected to a known external radial load. The author didn’t find in the literature the resolution of this problem using the procedure here described.

Many of the introductory subjects have already been addressed in other papers by other authors and aren’t repeated here (geometry of ball and roller bearings, formulas for normal stresses and deflections calculations when two elastic solids are brought into contact, relationships between load and deflection for static loading). Symbols used in formulas are introduced as they appear in the text. The formulas for static loading of ball and roller bearings are presented, including equilibrium equations in the discrete and integral forms. The former presented as a sum of the normal rolling element loads components in the direction of the external load, and the last as an integral around the loading zone.

The two Sjövall’s radial integral factors, relating the maximum loaded rolling element load and the average external load, are revisited, as well as approximations for radial integrals due to Refs. [

14,

25], for line- and point-contacts. The approximations’ errors with respect to the Sjövall’s radial integral’s numerical integration are shown. A numerical approximation for the Sjövall's radial integral is proposed, which fits the numerical integration properly for almost the entire load zone range, for both, line- and point-contact, which has shown to have smaller errors than other approximations for small load zones.

In sequence, two iterative scalar equations for the radial total displacement between the rings and for maximum deformation, using the Newton-Raphson method, are introduced. Knowing the radial total displacement or the maximum deflection and the diametrical clearance, the other parameters can be found, for both ball and roller bearings: the distance between shifted groove curvature centers - considering that for this type of loading, the all balls contact angles are null; the normal load, maximum deflection and contact ellipse parameters for each ball of the ball bearing; maximum deflection and semi-width contact parameters for each roller of the roller bearing. Numerical results of the presented Newton-Raphson based method are shown through plots, for 209, 210 and 218 deep groove or angular-contact ball bearings; one that appears in Ref. [

25], 205, 209 and 213 cylindrical roller bearings and have been compared with Stribeck’s and Palmgrem’s results, which consider

null diametrical clearance for a complete range of the radial load; with an approximate iterative integration method described in Ref. [

25], with results shown in Ref. [

14], and with approximations suggested in this work.

Recently, a similar paper [

26] was published where the results of the total radial displacement between the rigid rings, using the Newton-Raphson method, are compared with the approximations of Stribeck [

1], Hamrock and Anderson [

25], Oswald, Zaretsky and Poplawski [

14], and Ricci [

26], as radial external load functions, ranging from zero to 10,000 N, for ball bearings 209, 210 and 218. In this paper, in addition to new results for ball bearings, were also include the recursive equation for determining the maximum deflection and results for some types of cylindrical roller bearings.

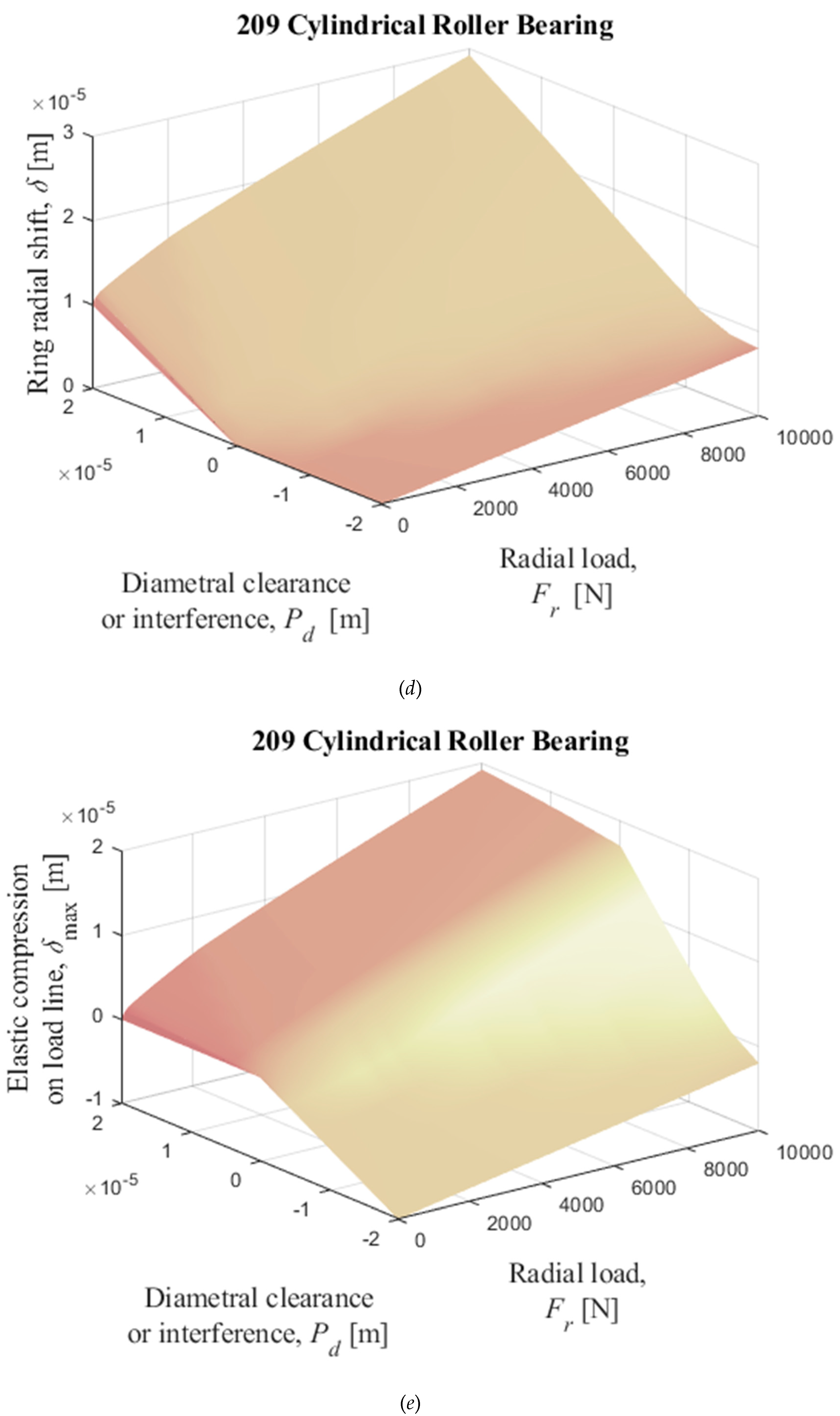

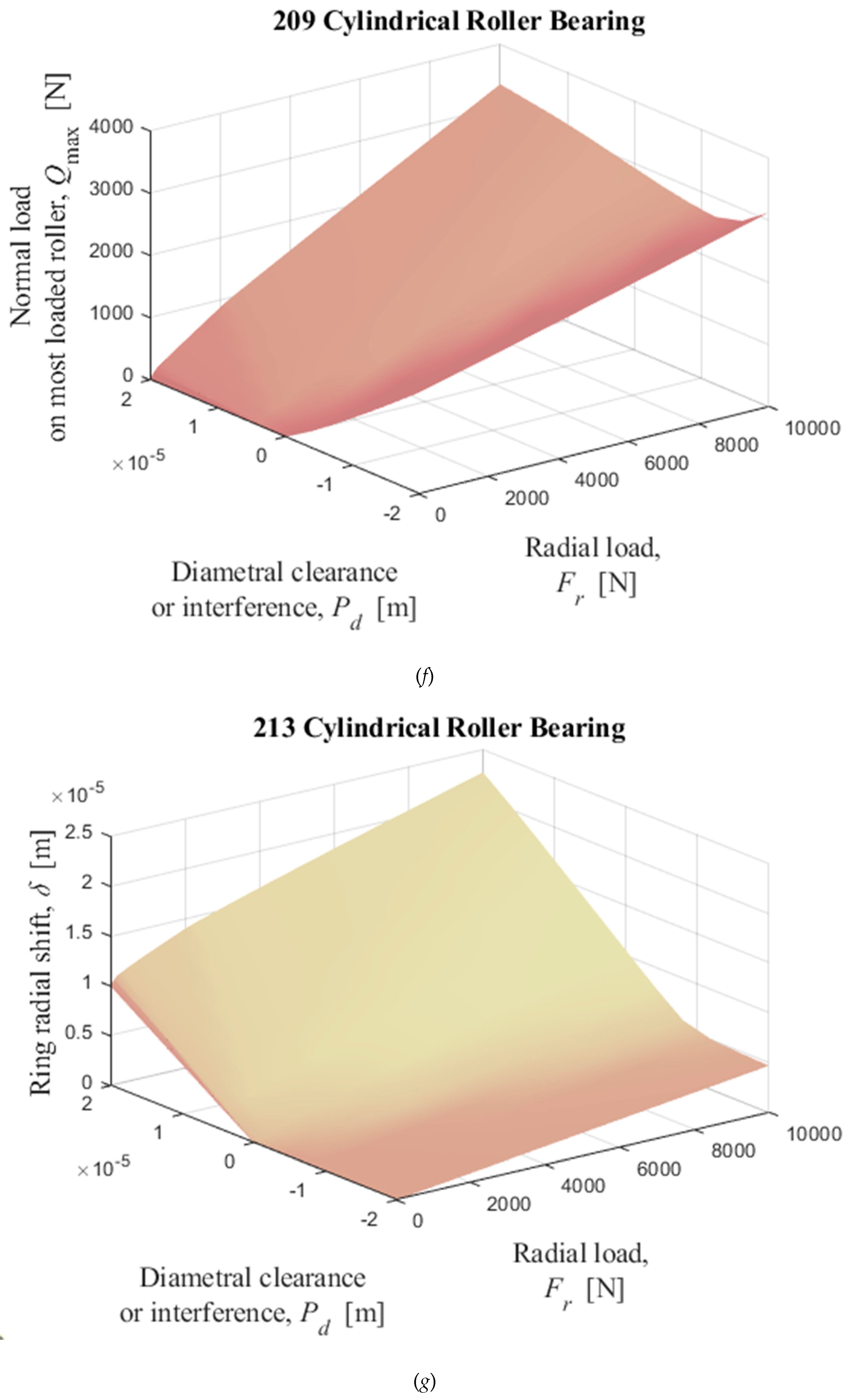

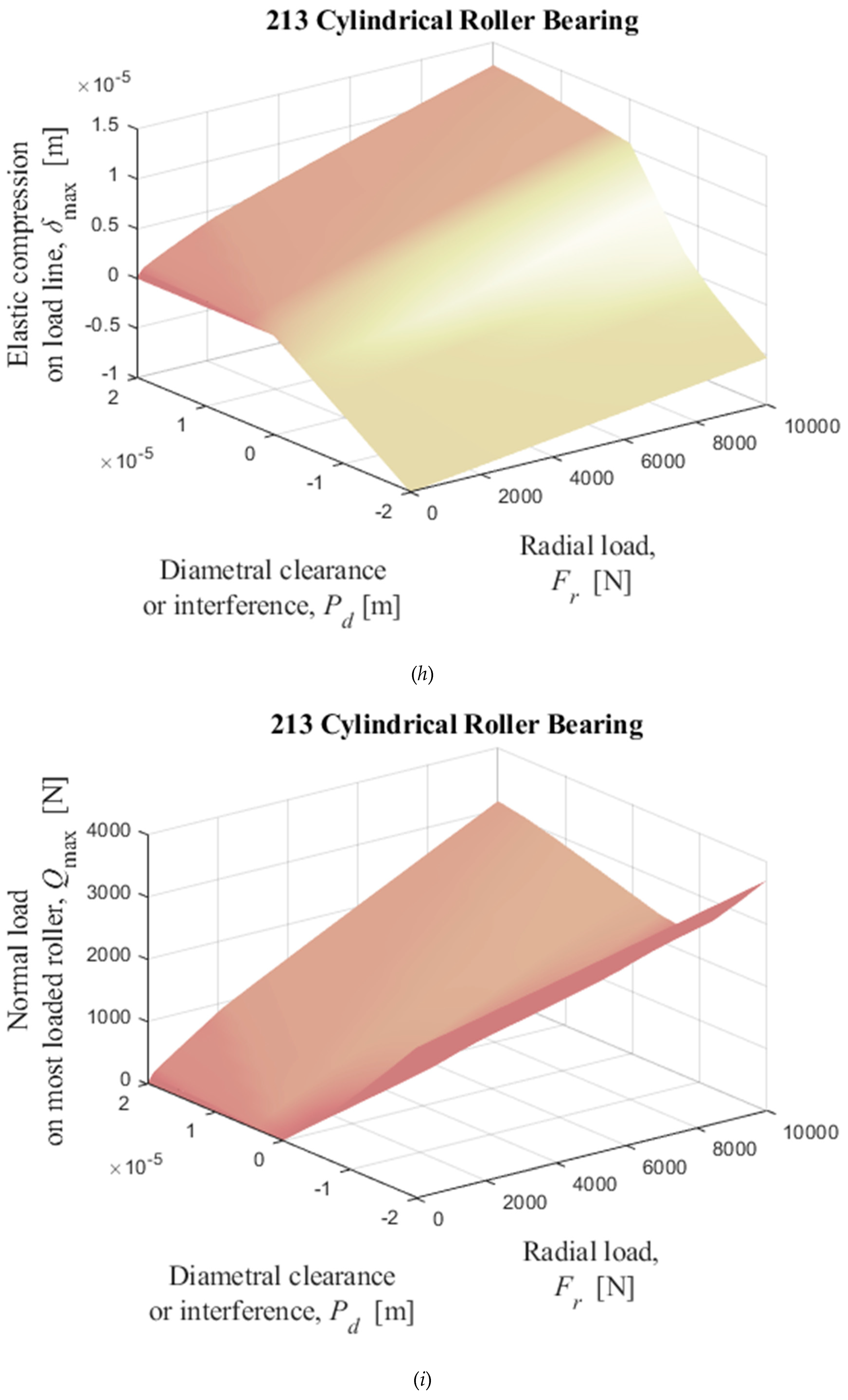

Finally, since the recursive equations introduced are ways to compute the total radial displacement between the rings and the maximum deflection at the race-rolling element elastic hertzian contact, respectively, as accurately as possible, for the ball and cylindrical roller bearings considered here, plots are presented for the total displacement between the rings, the rolling element maximum deflection and the normal load on the most loaded rolling element, as functions of the external radial load, ranging from zero to 10,000 N, and radial clearance, ranging from -2×10-5 to 2×10-5 m, using the Newton-Rhapson method.

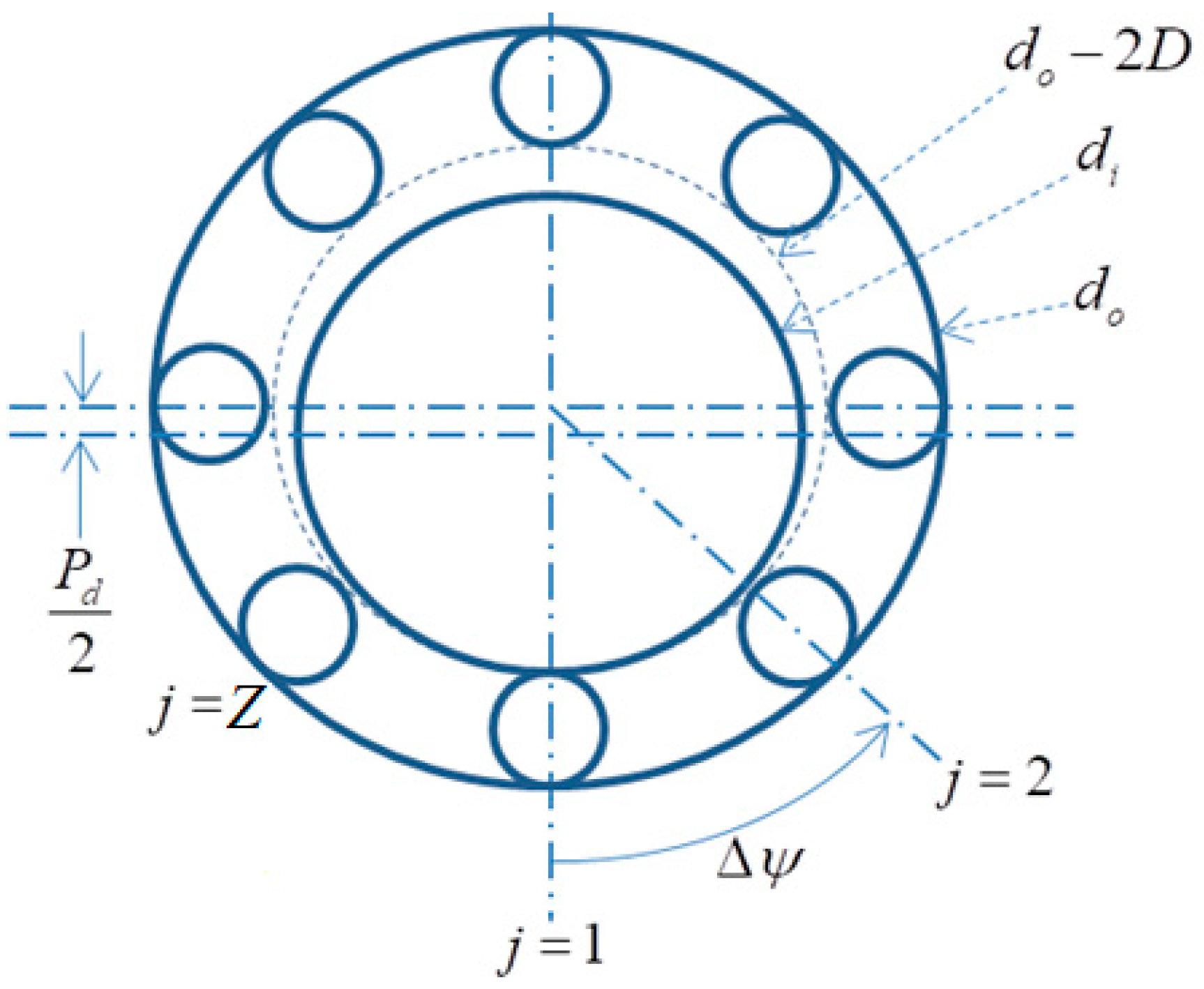

Figure 1.

Rolling elements angular positions in the radial plane, which is perpendicular to the bearing’s axis of rotation, Δψ = 2π/Z, ψj = Δψ(j − 1), j = 1, …, Z; Pd represents the diametrical clearance; do, di, D represent outer, inner raceways, and rolling element diameters, respectively.

Figure 1.

Rolling elements angular positions in the radial plane, which is perpendicular to the bearing’s axis of rotation, Δψ = 2π/Z, ψj = Δψ(j − 1), j = 1, …, Z; Pd represents the diametrical clearance; do, di, D represent outer, inner raceways, and rolling element diameters, respectively.

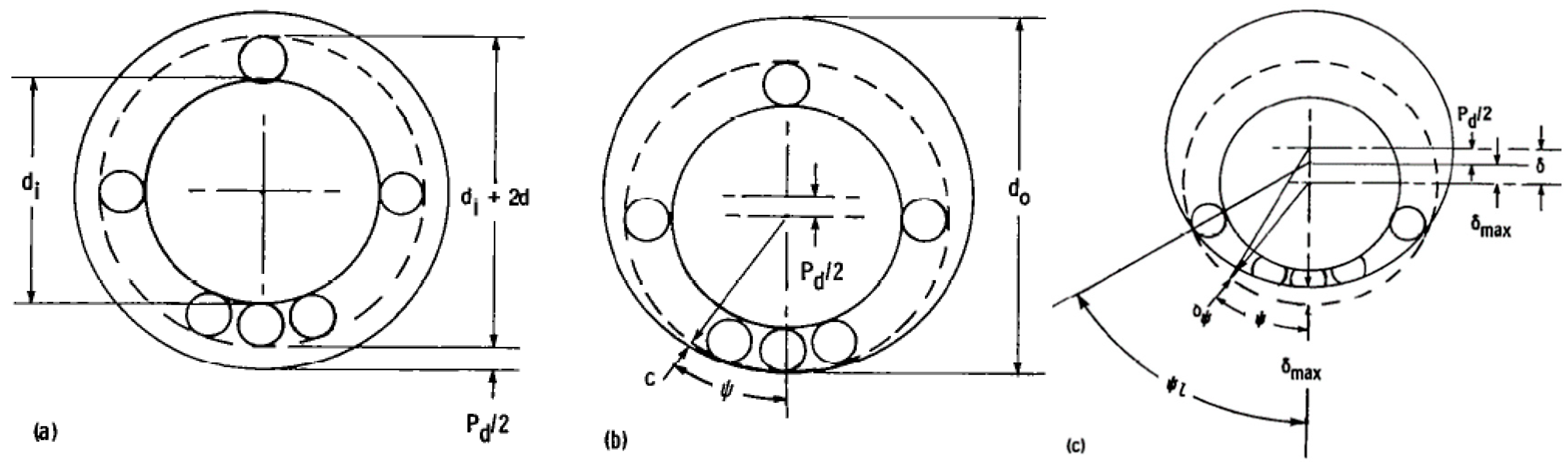

Figure 2.

Radially loaded bearing with diametrical clearance

Pd > 0, at which the load line passes through the most loaded rolling element’s center: (

a) Concentric arrangement; (

b) Initial contact; (

c) Interference. Source: Hamrock and Anderson [

25].

Figure 2.

Radially loaded bearing with diametrical clearance

Pd > 0, at which the load line passes through the most loaded rolling element’s center: (

a) Concentric arrangement; (

b) Initial contact; (

c) Interference. Source: Hamrock and Anderson [

25].

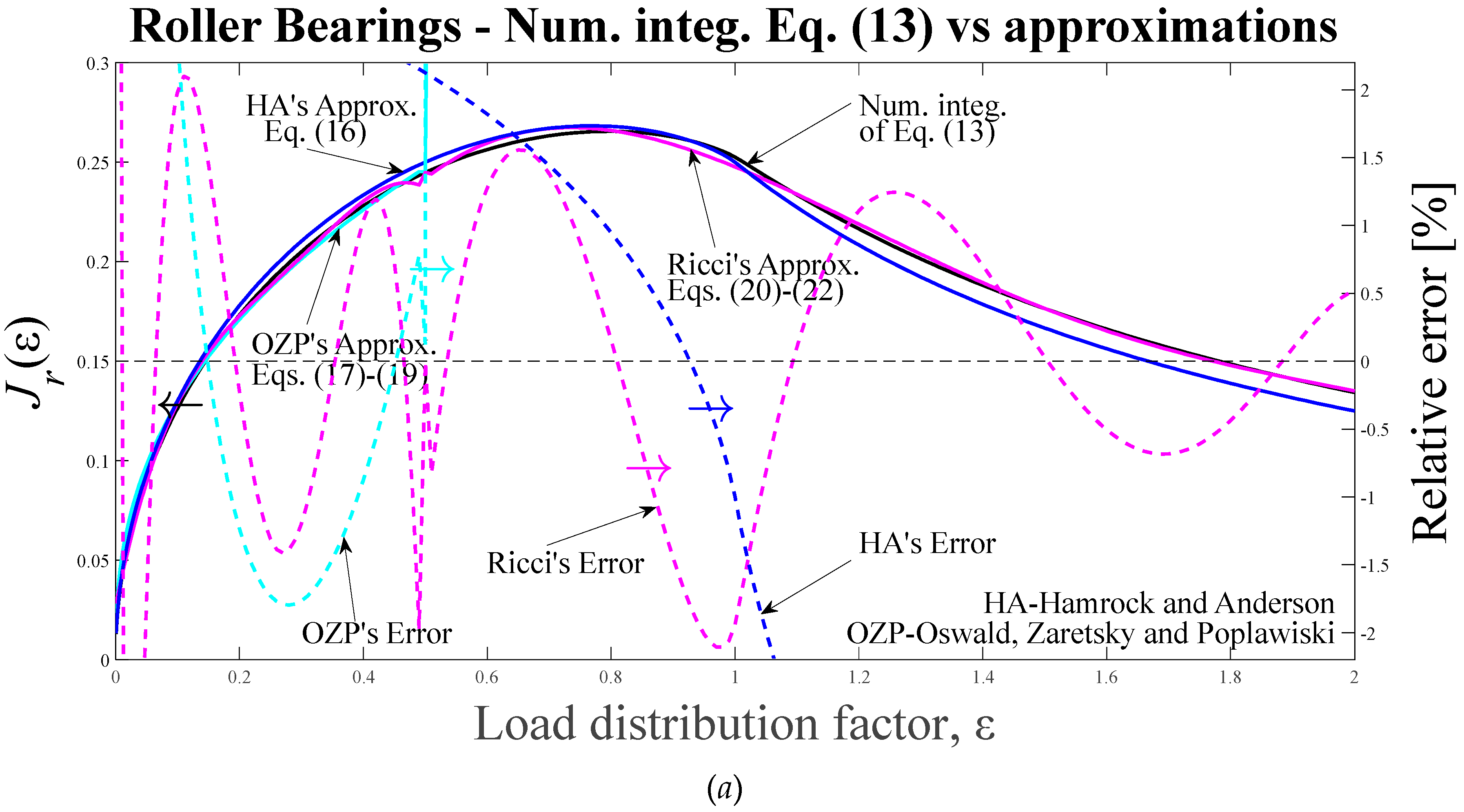

Figure 3.

Numerical integration of Eq. (13), approximations and relative errors with respect to the numerical integration, as functions of ε, for 0 ≤ ε ≤ 2. (a) n = 10/9; HA’s approx. for n = 1 (Eq. (16)); OZP’s approx. (Eqs. (17)-(19)); Ricci’s approx. (Eqs. (20)-(22)). (b) n = 3/2; HA’s approx. (Eq. (23)) multiplied by the factor (2ε)-3/2; OZP’s approx. (Eqs. (24)-(26)); Ricci’s approx. (Eqs. (27)-(29)). HA-Hamrock and Anderson; OZP-Oswald, Zaretsky and Poplawski.

Figure 3.

Numerical integration of Eq. (13), approximations and relative errors with respect to the numerical integration, as functions of ε, for 0 ≤ ε ≤ 2. (a) n = 10/9; HA’s approx. for n = 1 (Eq. (16)); OZP’s approx. (Eqs. (17)-(19)); Ricci’s approx. (Eqs. (20)-(22)). (b) n = 3/2; HA’s approx. (Eq. (23)) multiplied by the factor (2ε)-3/2; OZP’s approx. (Eqs. (24)-(26)); Ricci’s approx. (Eqs. (27)-(29)). HA-Hamrock and Anderson; OZP-Oswald, Zaretsky and Poplawski.

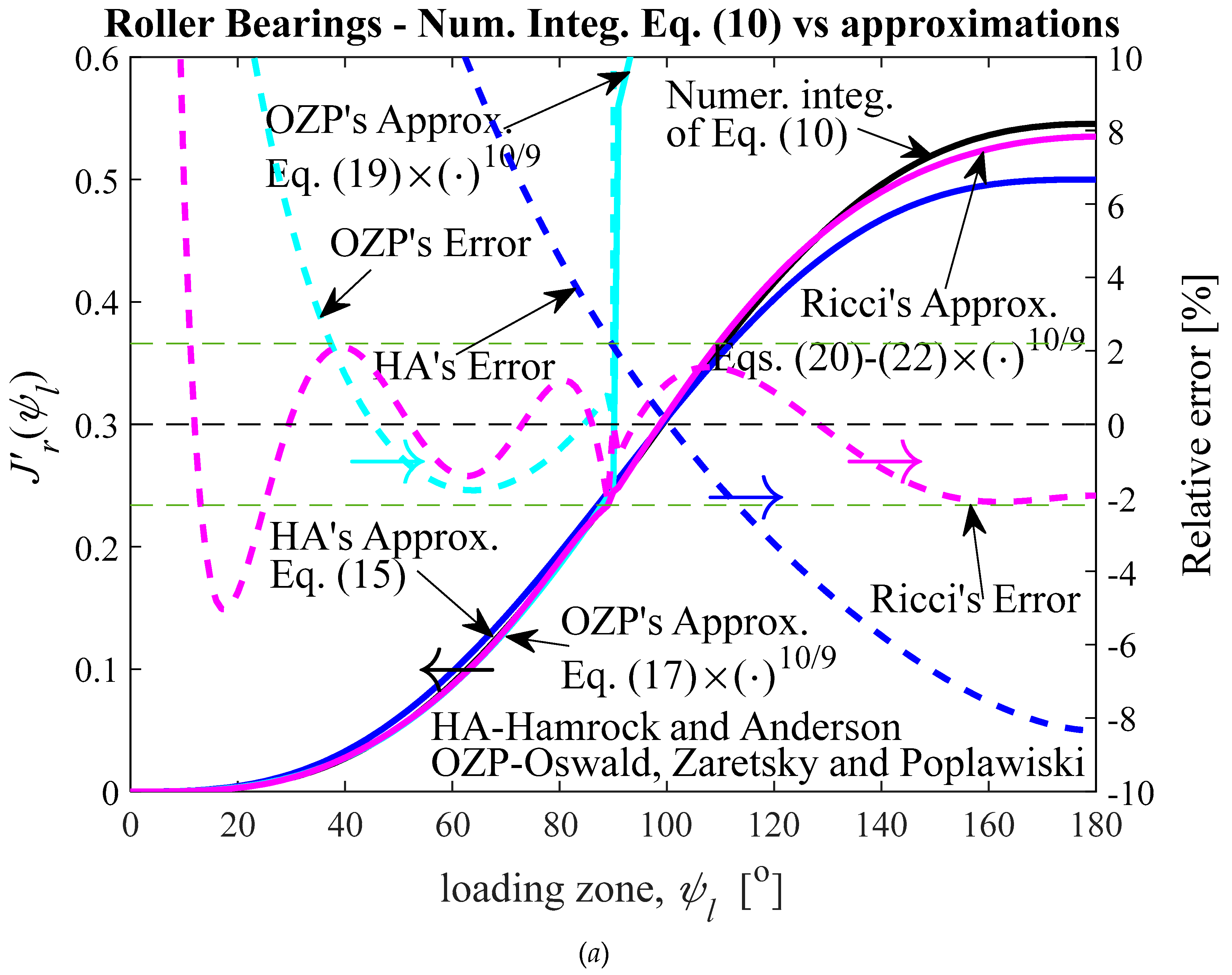

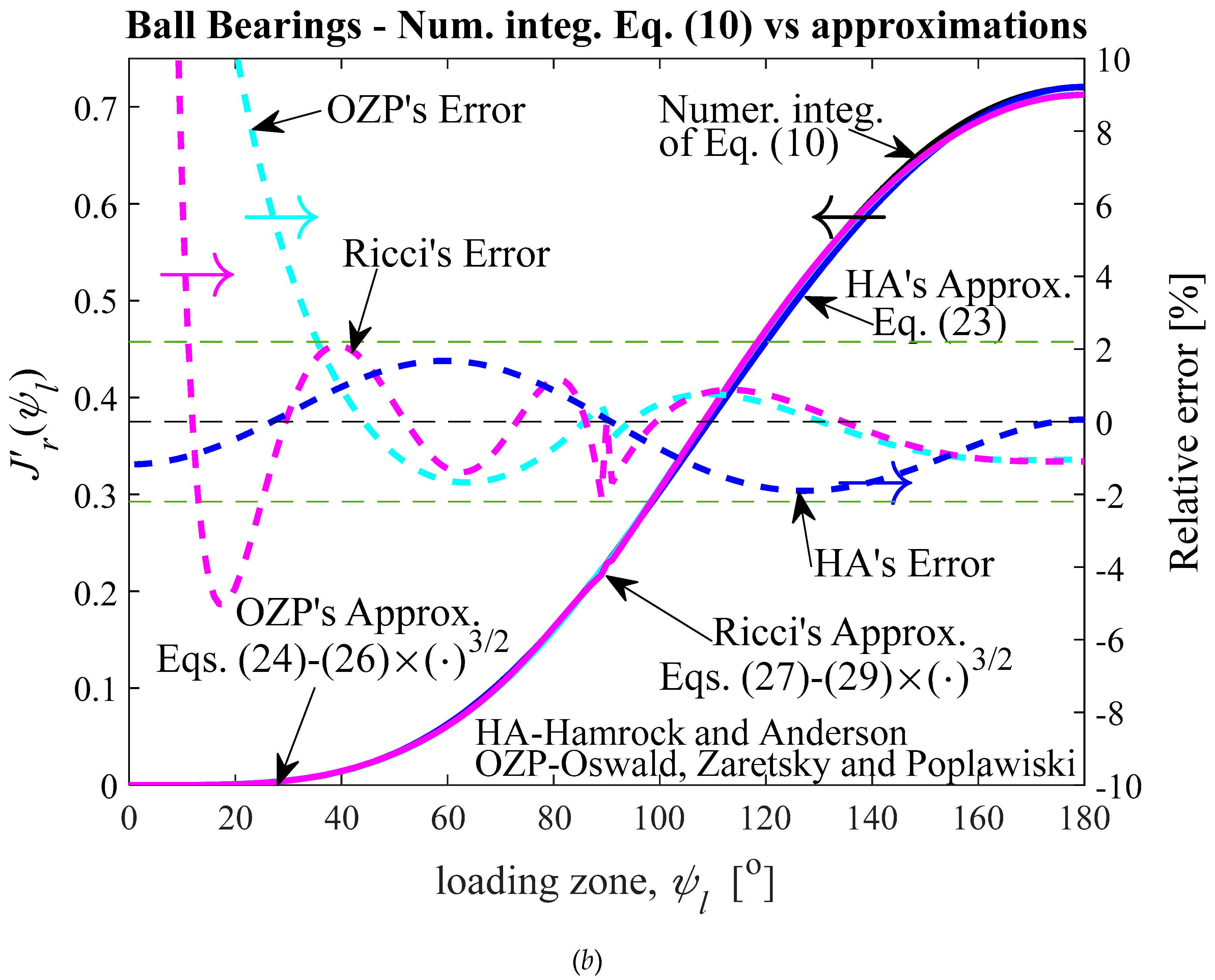

Figure 4.

Numerical integration of Eq. (10), approximations and relative errors with respect to the numerical integration, as functions of ψl, for 0 ≤ ψl ≤ 180o. (a) n = 10/9; HA’s approx. for n = 1 (Eq. (15)); OZP’s approx. (Eqs. (17)-(19)); Ricci’s approx. (Eqs. (20)-(22)), with last two approximations multiplied by the factor between curved brackets raised to the power n = 10/9 in the Eq. (14); (b) n = 3/2; HA’s approx. (Eq. (23)); OZP’s approx. (Eqs. (24)-(26)); Ricci’s approx. (Eqs. (27)-(29)), with last two approximations multiplied by the factor between curved brackets raised to the power n = 3/2 in the Eq. (14).

Figure 4.

Numerical integration of Eq. (10), approximations and relative errors with respect to the numerical integration, as functions of ψl, for 0 ≤ ψl ≤ 180o. (a) n = 10/9; HA’s approx. for n = 1 (Eq. (15)); OZP’s approx. (Eqs. (17)-(19)); Ricci’s approx. (Eqs. (20)-(22)), with last two approximations multiplied by the factor between curved brackets raised to the power n = 10/9 in the Eq. (14); (b) n = 3/2; HA’s approx. (Eq. (23)); OZP’s approx. (Eqs. (24)-(26)); Ricci’s approx. (Eqs. (27)-(29)), with last two approximations multiplied by the factor between curved brackets raised to the power n = 3/2 in the Eq. (14).

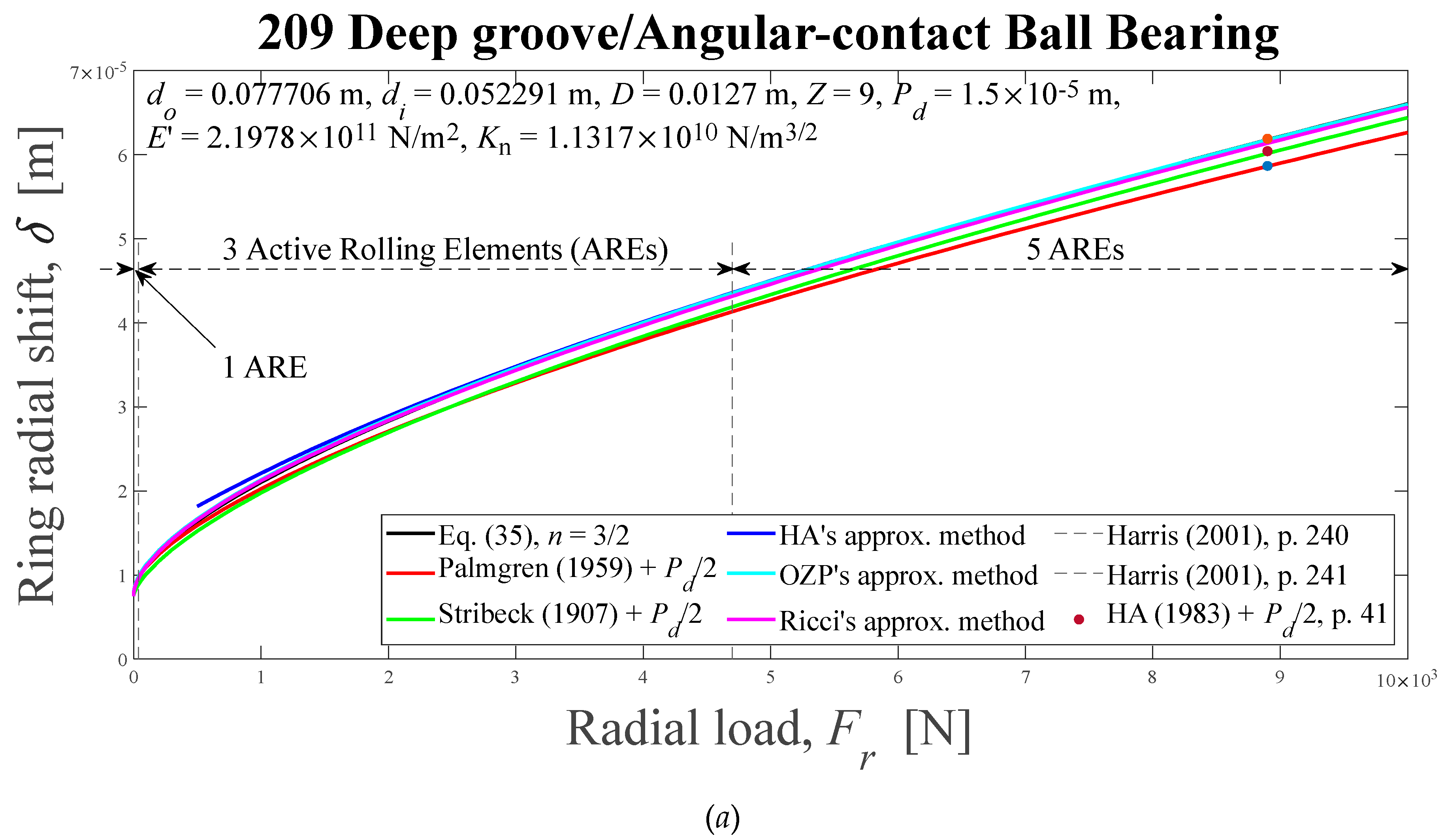

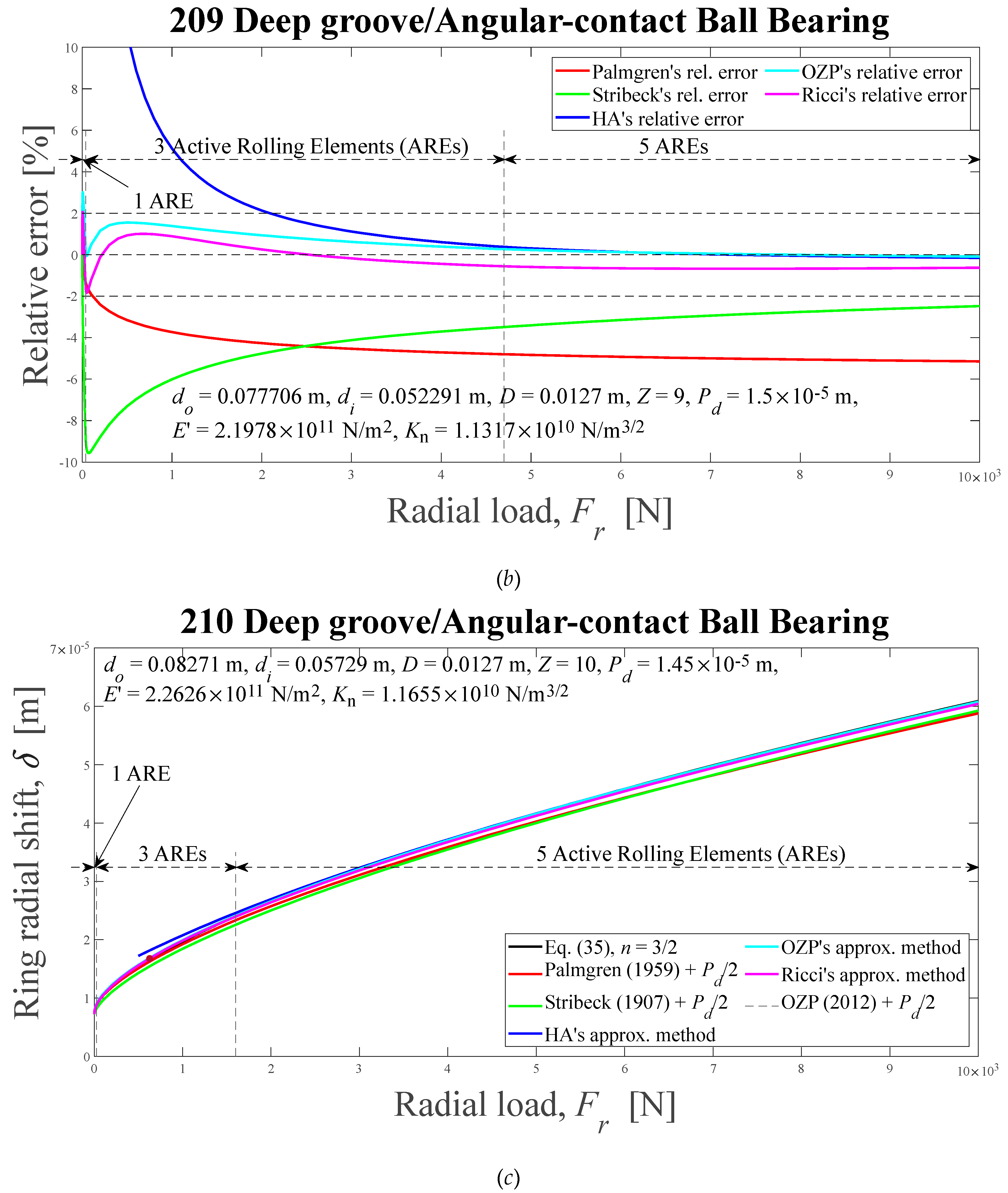

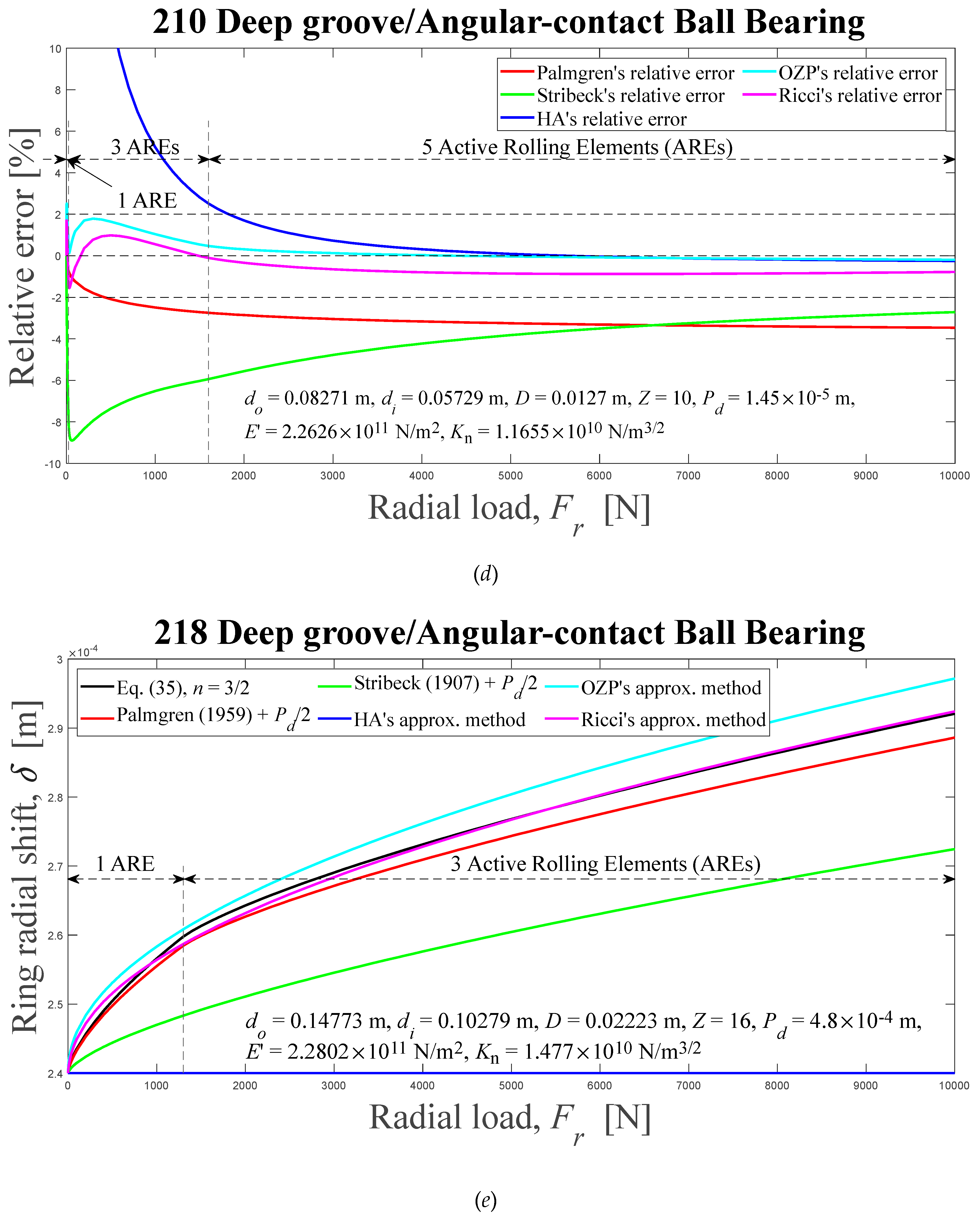

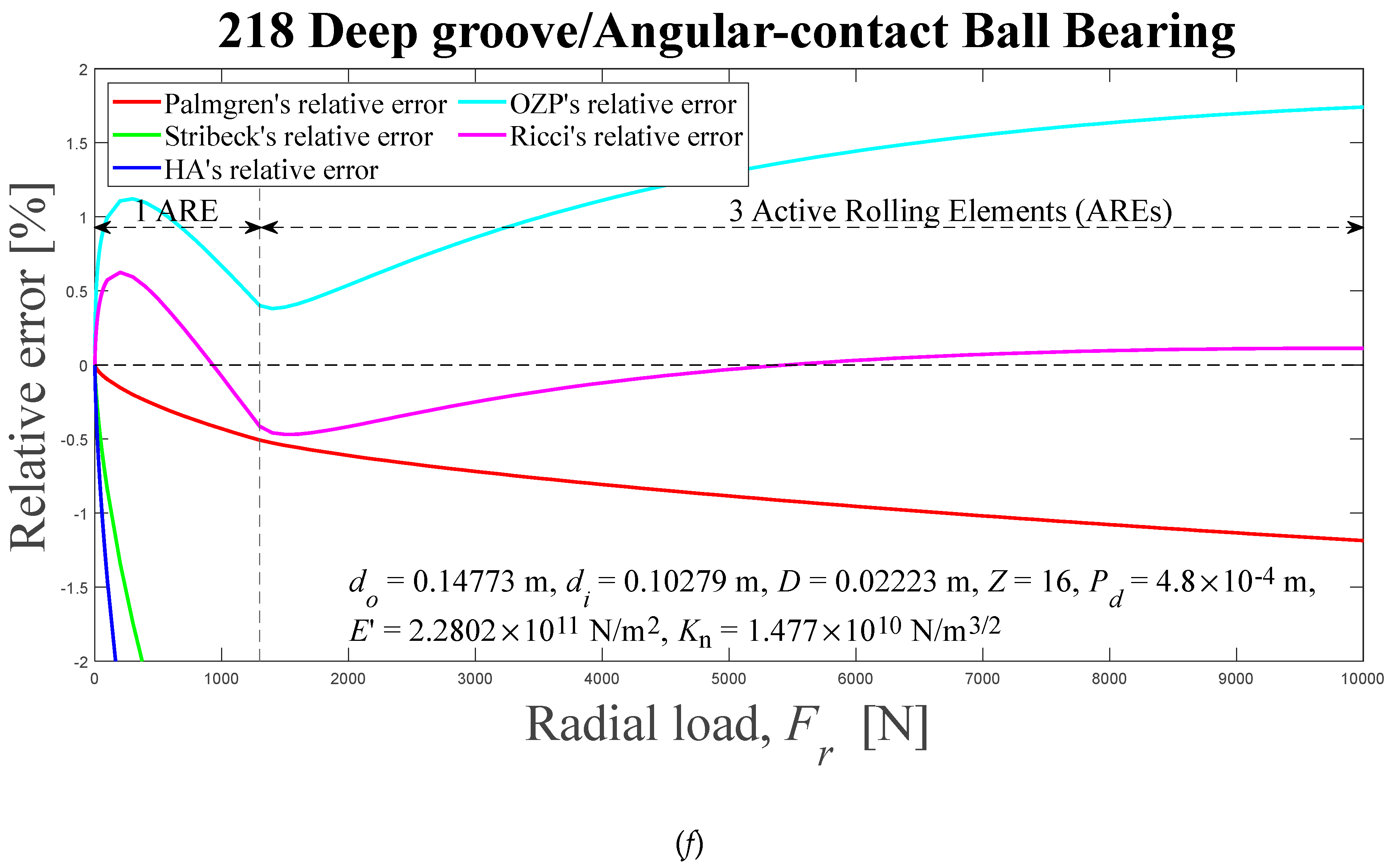

Figure 5.

Displacements between rigid rings of deep-groove or angular-contact ball bearings for six different methods, and relative errors, as a function of external radial load. Results presented in the literature also are shown: (a) and (b) 209, 0 < ε < 0.44, 0° < ψl < 83.37°; (c) and (d) 210, 0 < ε < 0.44, 0° < ψl < 83.16°; (e) and (f) 218, 0 < ε < 0.09, 0°< ψl < 34.74°. HA-Hamrock and Anderson; OZP-Oswald, Zaretsky and Poplawski.

Figure 5.

Displacements between rigid rings of deep-groove or angular-contact ball bearings for six different methods, and relative errors, as a function of external radial load. Results presented in the literature also are shown: (a) and (b) 209, 0 < ε < 0.44, 0° < ψl < 83.37°; (c) and (d) 210, 0 < ε < 0.44, 0° < ψl < 83.16°; (e) and (f) 218, 0 < ε < 0.09, 0°< ψl < 34.74°. HA-Hamrock and Anderson; OZP-Oswald, Zaretsky and Poplawski.

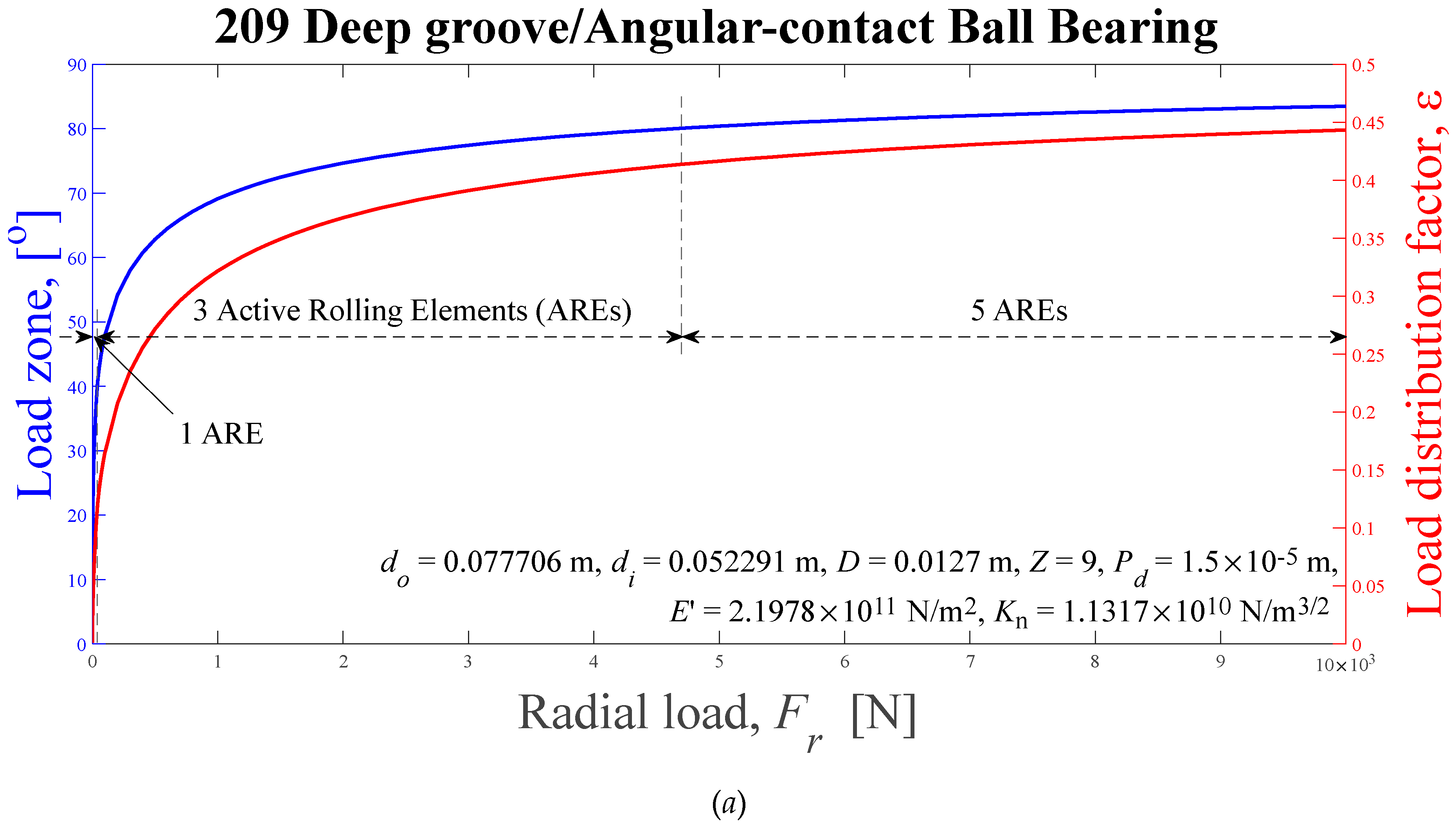

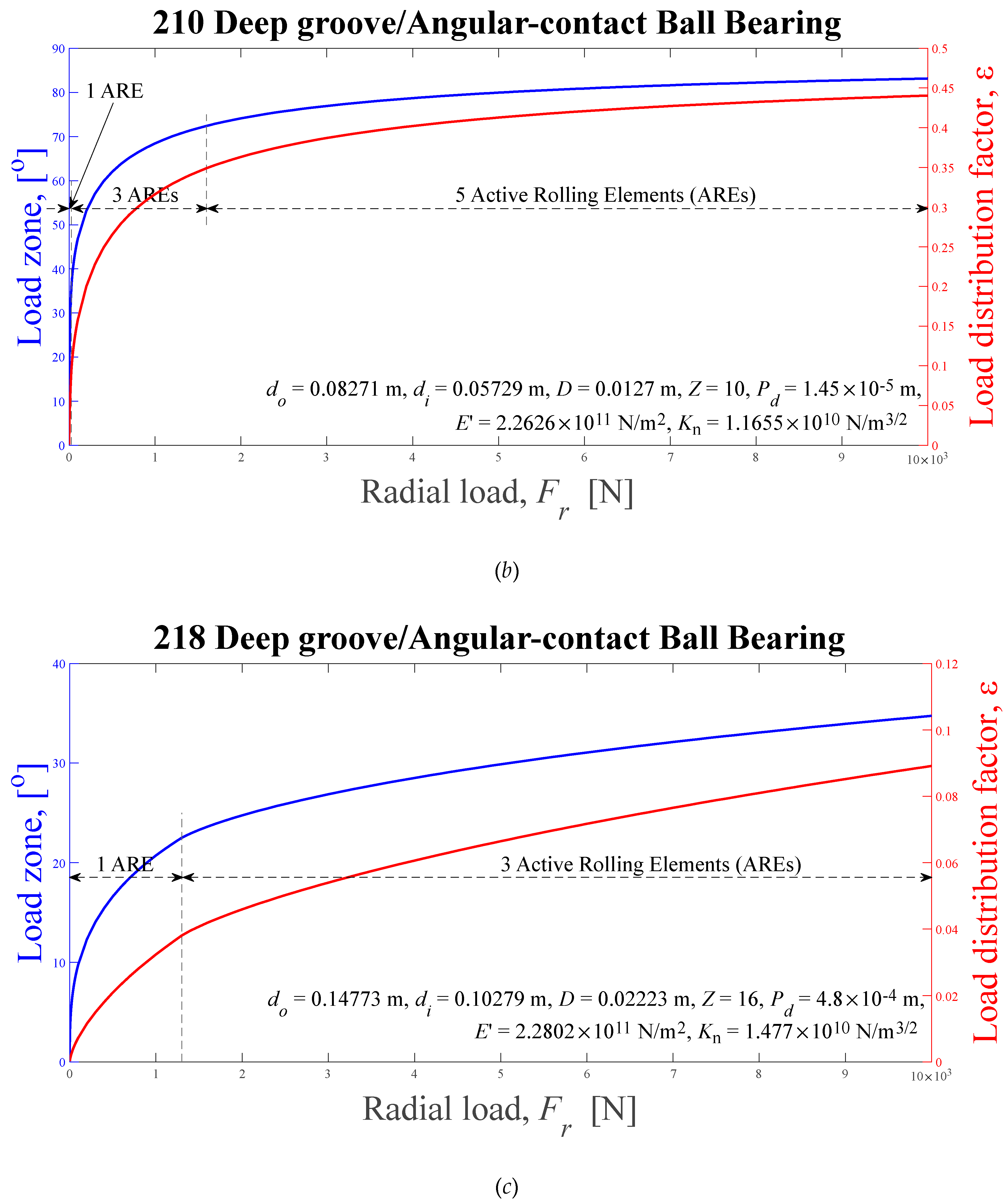

Figure 6.

Load zones, ψl, and load distribution factors, ε, computed using the Eq. (35) solved by Newton-Raphson's scheme, as radial external load functions. (a) 209, (b) 210, and (c) 218.

Figure 6.

Load zones, ψl, and load distribution factors, ε, computed using the Eq. (35) solved by Newton-Raphson's scheme, as radial external load functions. (a) 209, (b) 210, and (c) 218.

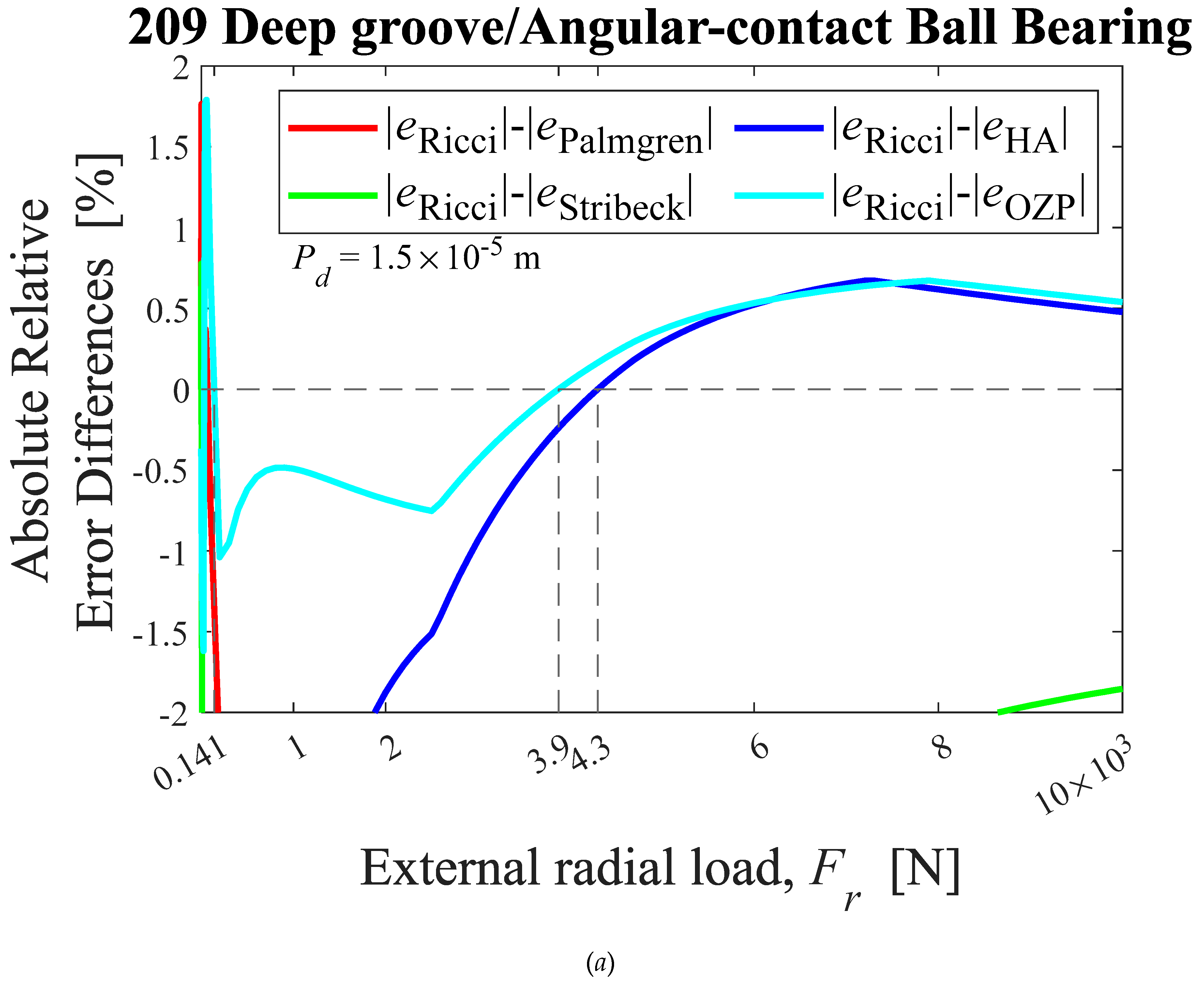

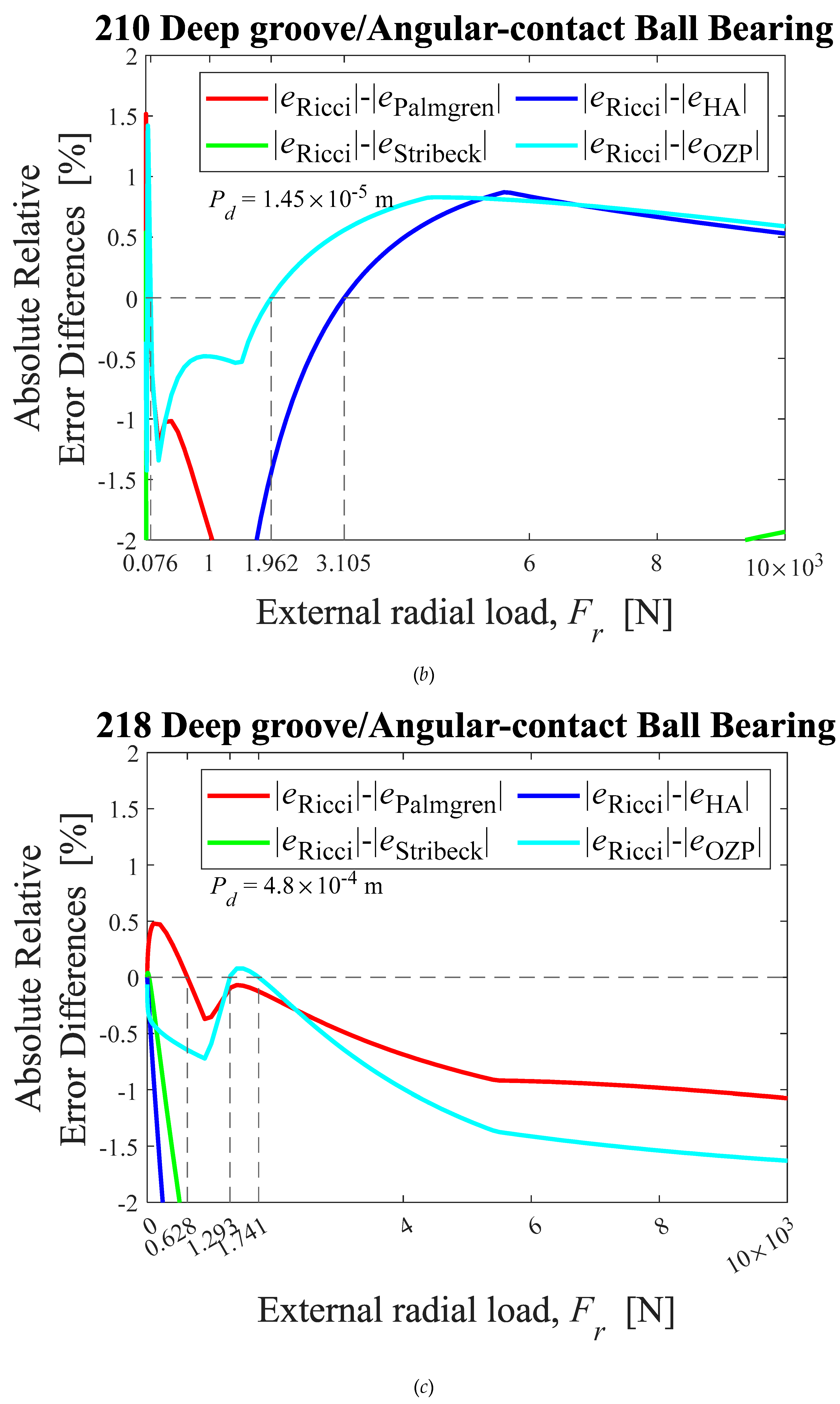

Figure 7.

Absolute relative Error differences between the Ricci approximation and Palmgren’s, Stribeck’s, HA’s, and OZP’s, approximations, as external radial load functions, for ball bearings: (a) 209, (b) 210, (c) 218. HA-Hamrock and Anderson; OZP-Oswald, Zaretsky and Poplawski.

Figure 7.

Absolute relative Error differences between the Ricci approximation and Palmgren’s, Stribeck’s, HA’s, and OZP’s, approximations, as external radial load functions, for ball bearings: (a) 209, (b) 210, (c) 218. HA-Hamrock and Anderson; OZP-Oswald, Zaretsky and Poplawski.

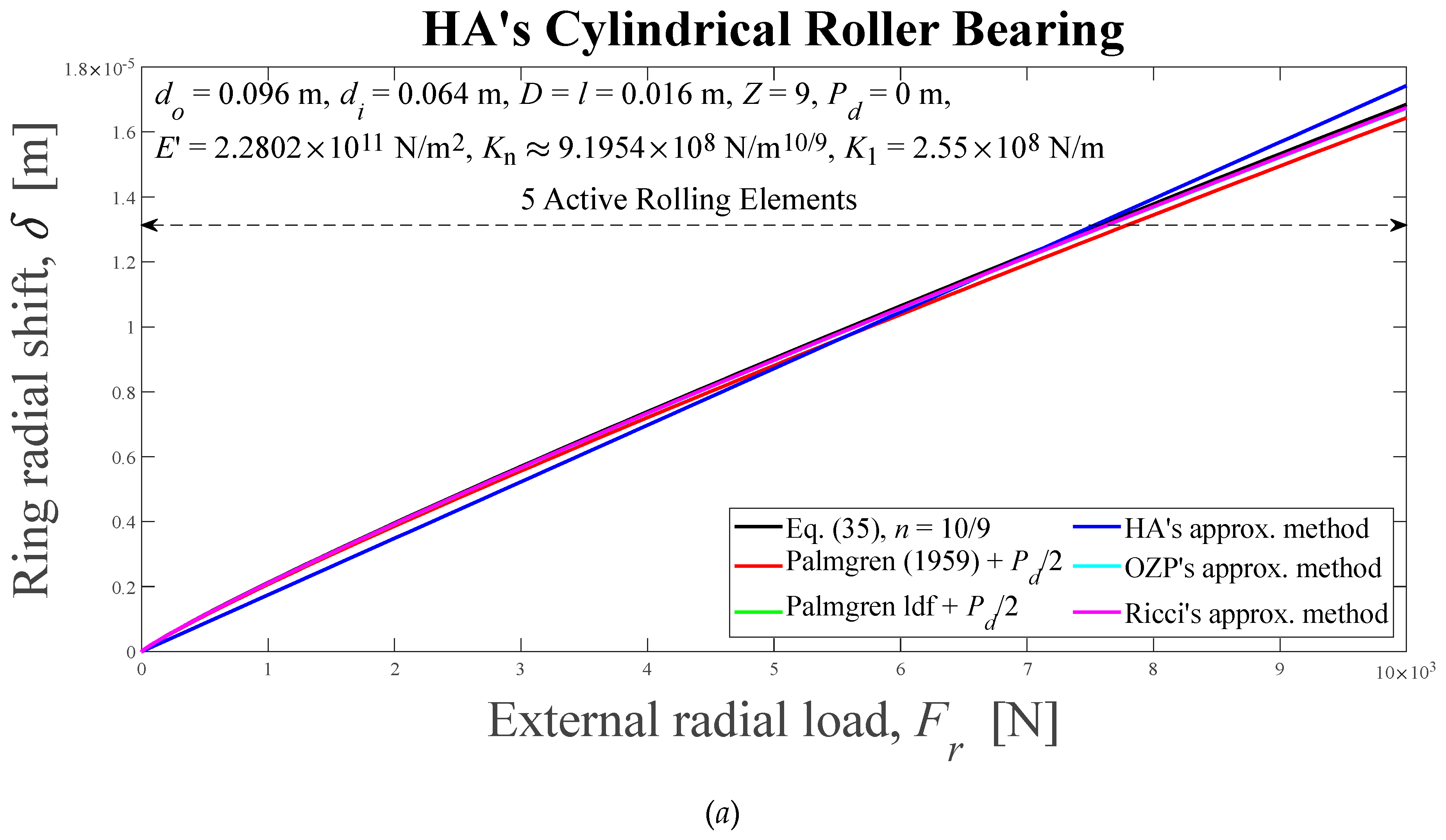

Figure 8.

Displacements between rigid rings, computed using the Eq. (35), for a cylindrical roller bearing used in Ref. [

25], as external radial load functions, applied to the inner ring, for some effective load-deflection factor values.

Figure 8.

Displacements between rigid rings, computed using the Eq. (35), for a cylindrical roller bearing used in Ref. [

25], as external radial load functions, applied to the inner ring, for some effective load-deflection factor values.

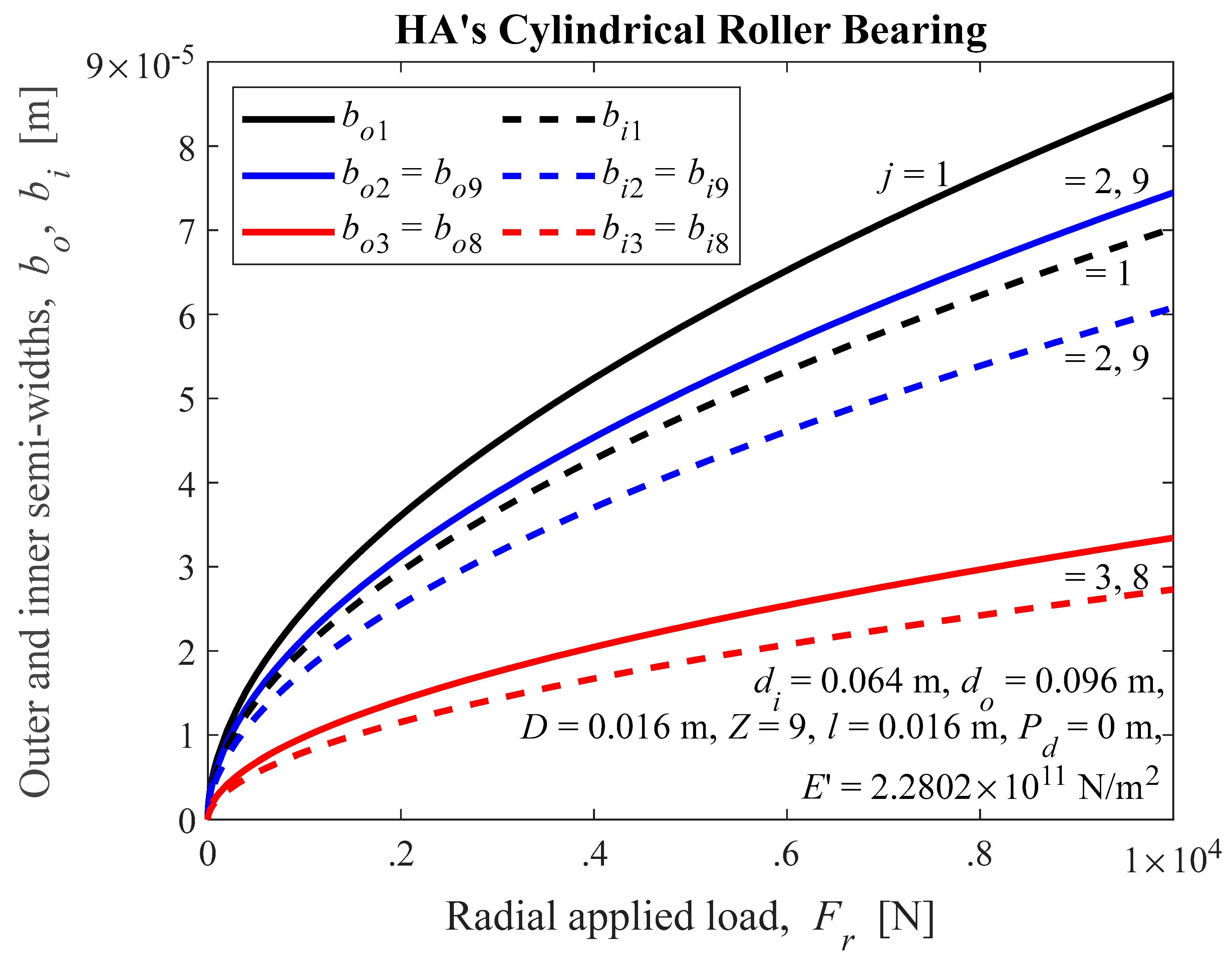

Figure 9.

Outer and inner contact semi-widths, computed using the Eq. (35), for the cylindrical roller bearing used in Ref. [

25], as external radial load functions, for effective load-deflection factor values

K1 given by the dashed lines in

Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Outer and inner contact semi-widths, computed using the Eq. (35), for the cylindrical roller bearing used in Ref. [

25], as external radial load functions, for effective load-deflection factor values

K1 given by the dashed lines in

Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Outer, inner and effective load-deflection ESDU factors, computed using the Eq. (35), for the cylindrical roller bearing used in Ref. [

25], as external radial load functions.

Figure 10.

Outer, inner and effective load-deflection ESDU factors, computed using the Eq. (35), for the cylindrical roller bearing used in Ref. [

25], as external radial load functions.

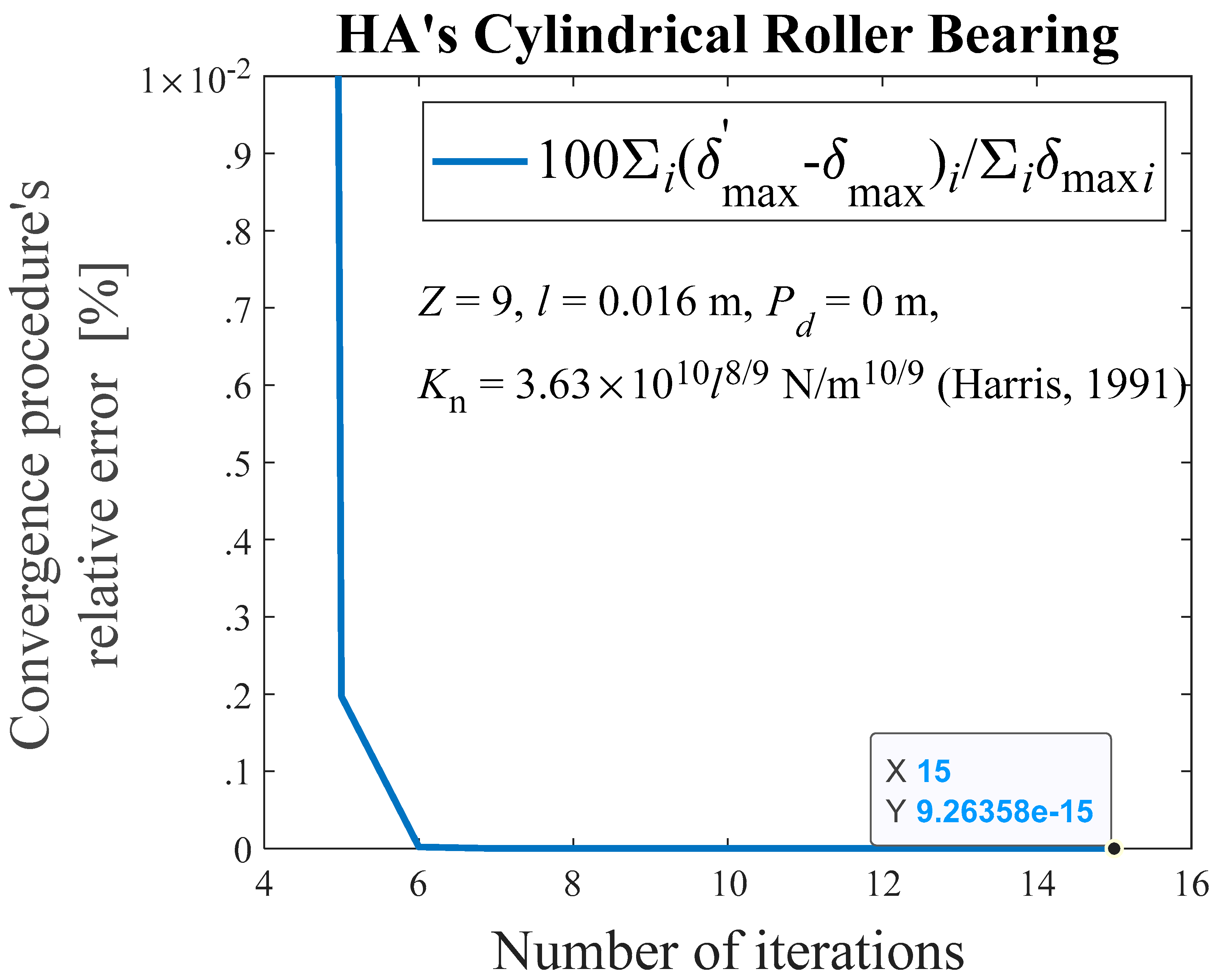

Figure 11.

Convergence’s procedure relative error in percentage, in determining the displacement between rings, computed using the Eq. (36), for the cylindrical roller bearing used in Ref. [

25], as function of the iterations number.

Figure 11.

Convergence’s procedure relative error in percentage, in determining the displacement between rings, computed using the Eq. (36), for the cylindrical roller bearing used in Ref. [

25], as function of the iterations number.

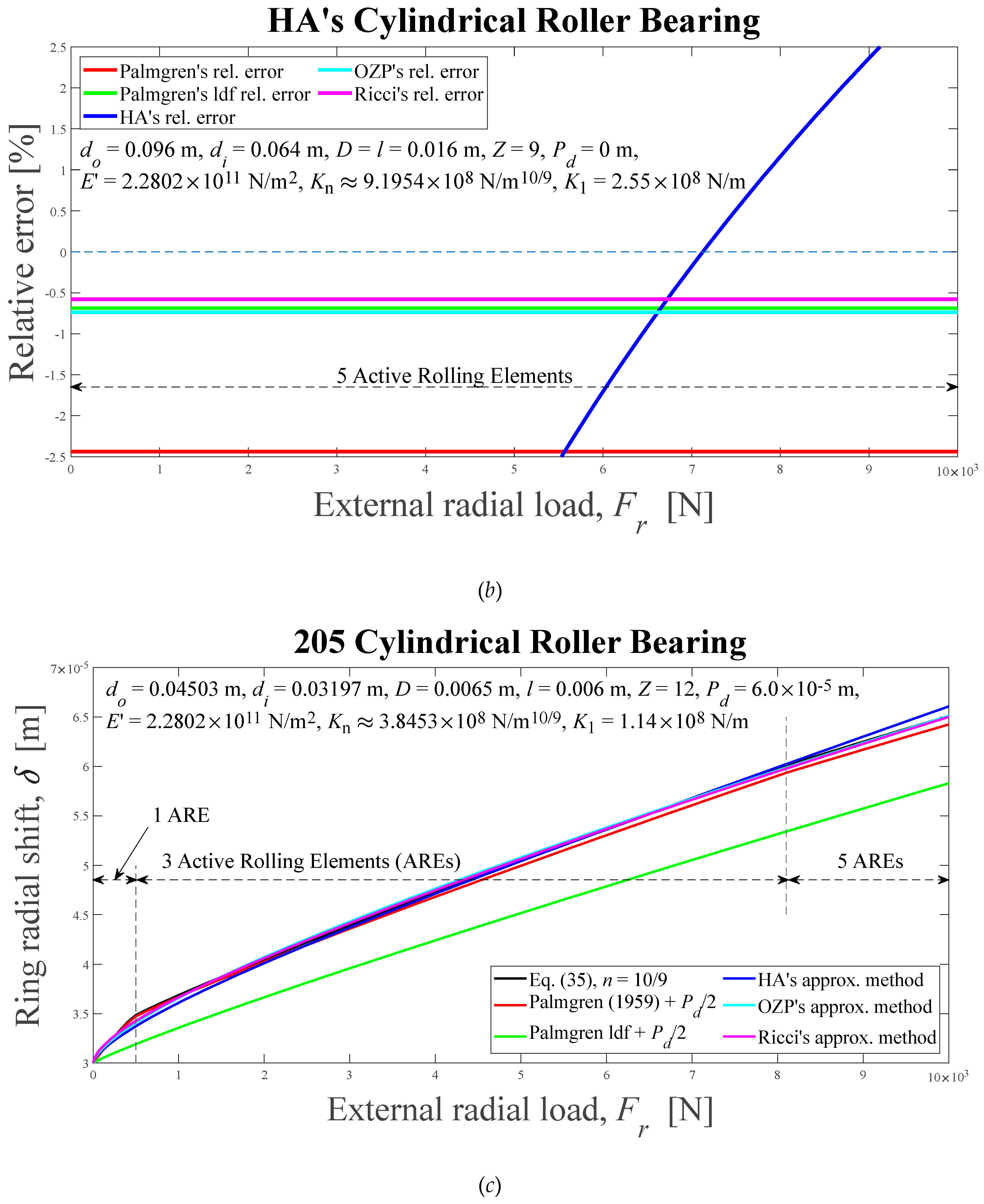

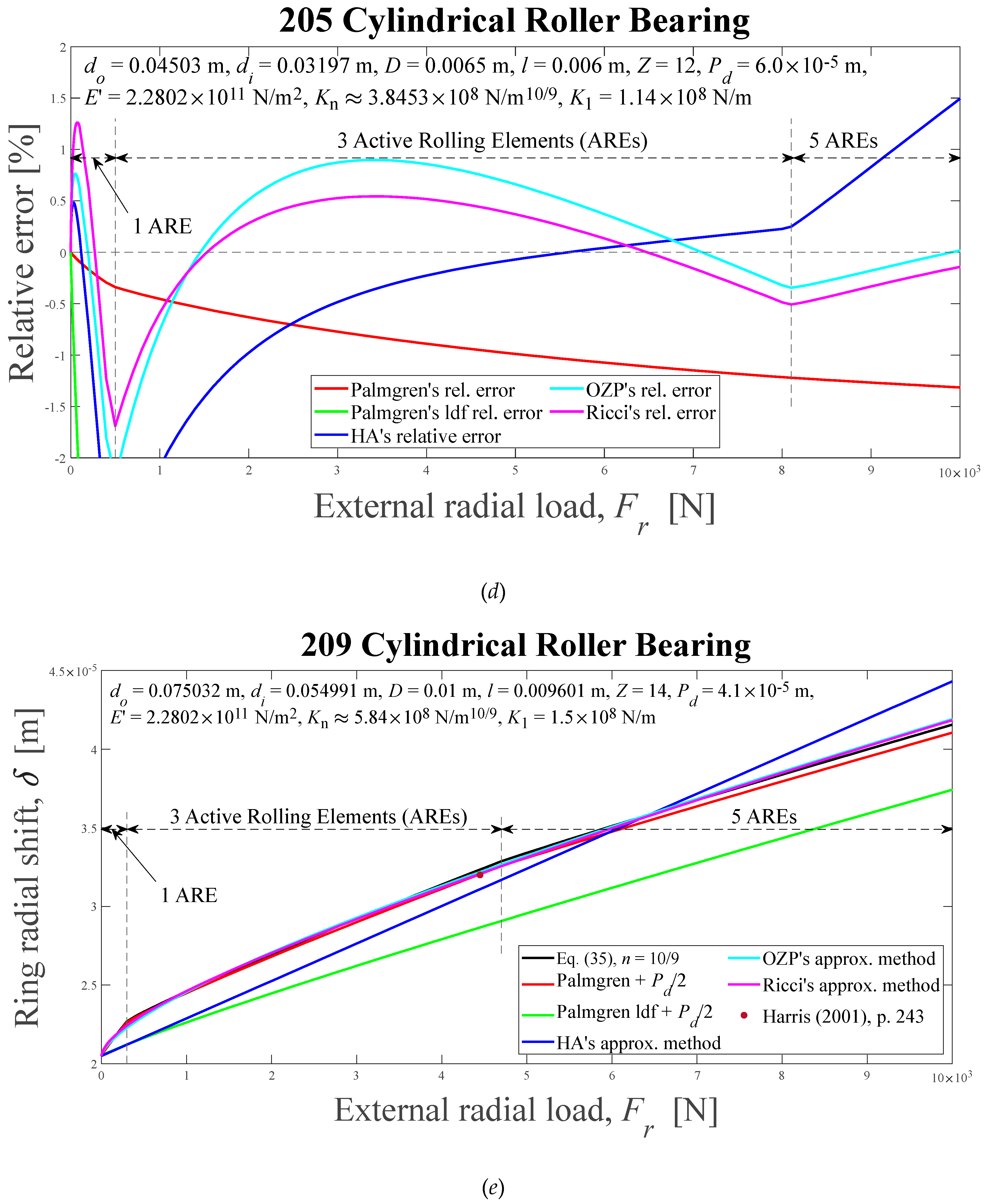

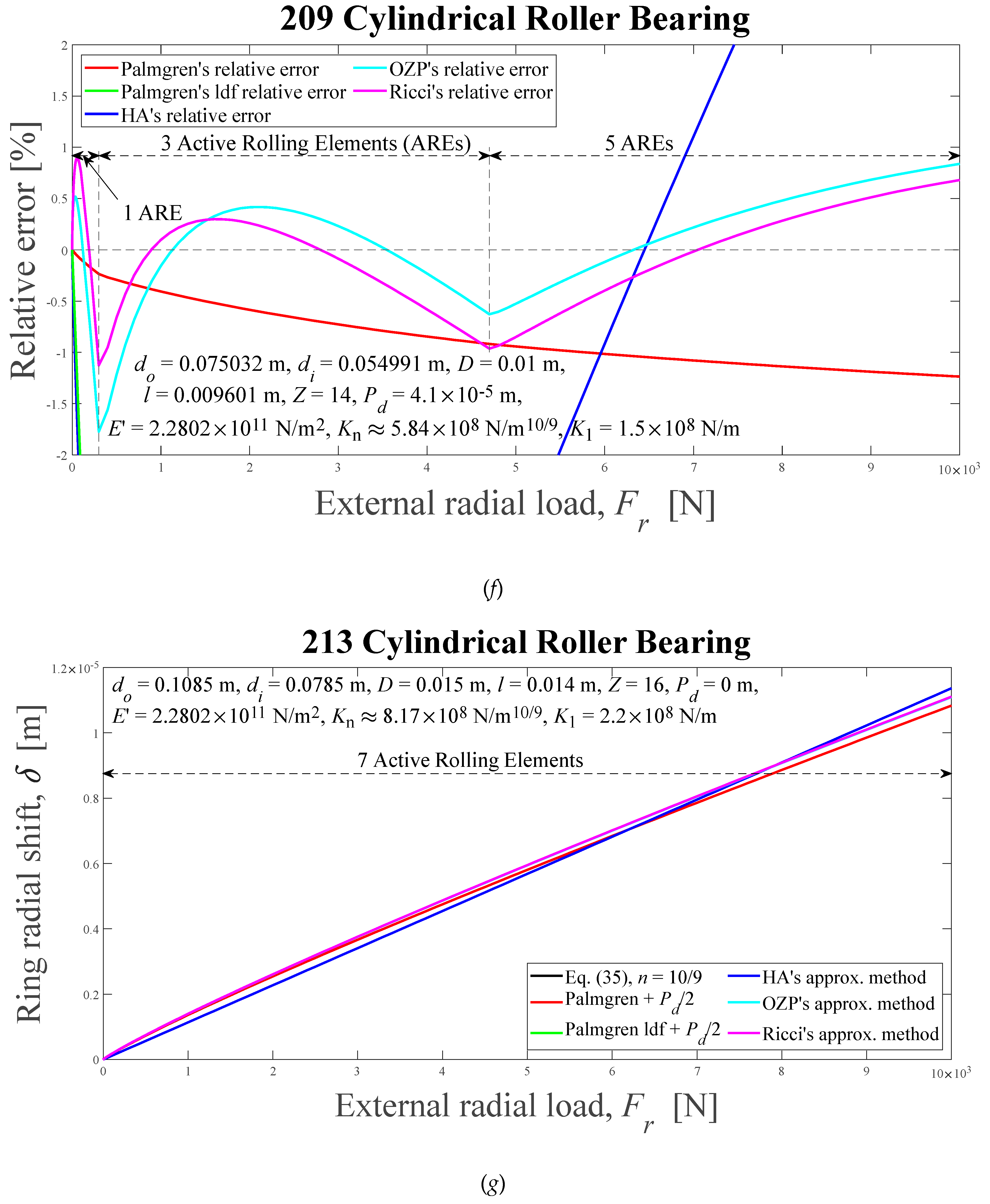

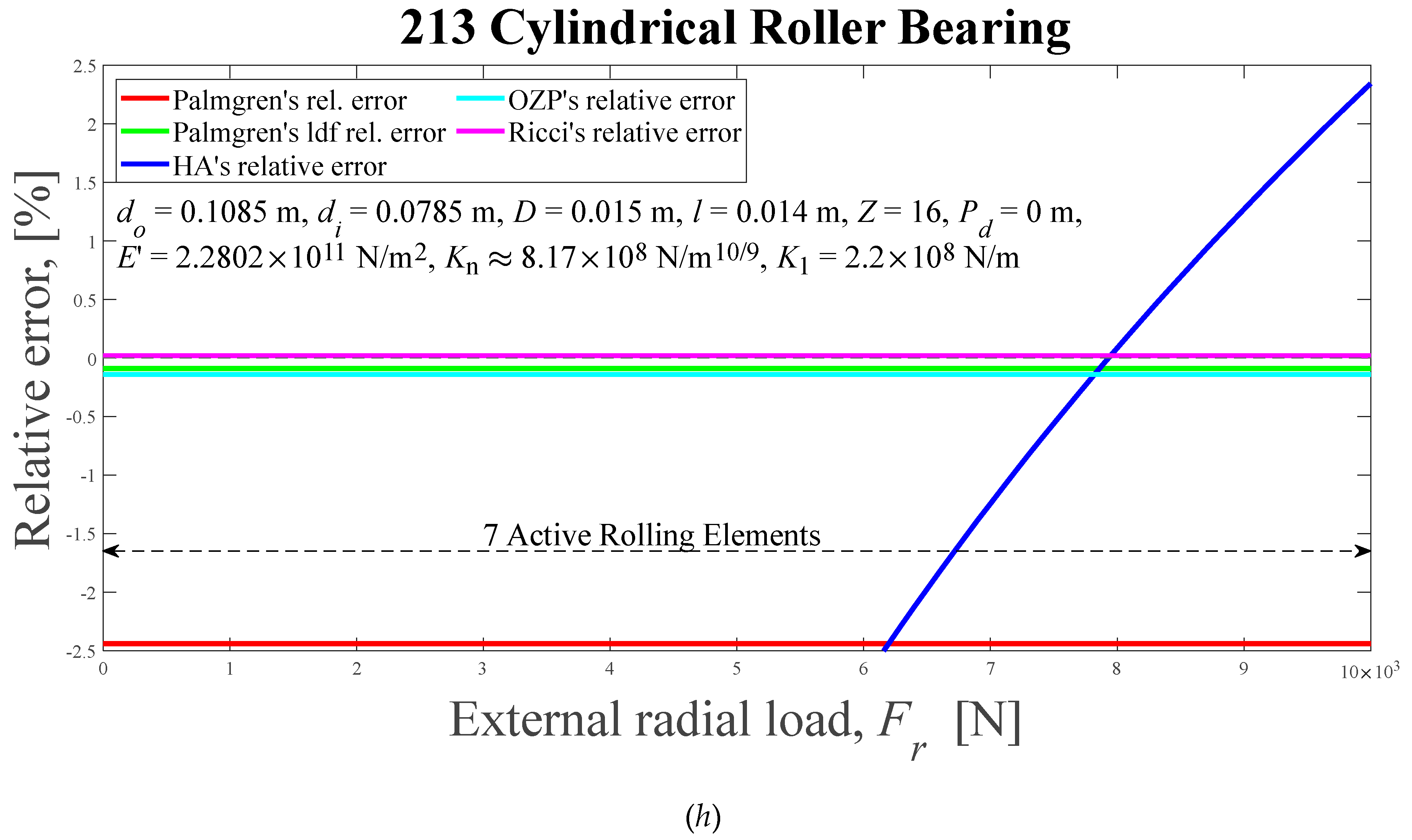

Figure 12.

Displacements between rigid rings and relative errors of the approximations with respect to the numerical solution for cylindrical roller bearings, as external radial load functions, for six different methods: (a) and (b) HA’s, ε = 0.5, ψl = 90°; (c) and (d) 205, 0 < ε < 0.27, 0° < ψl < 62.56°; (e) and (f) 209, 0 < ε < 0.25, 0°< ψl < 60.44°; (g) and (h) 213, ε = 0.5, ψl = 90°. HA-Hamrock and Anderson; OZP-Oswald, Zaretsky and Poplawski.

Figure 12.

Displacements between rigid rings and relative errors of the approximations with respect to the numerical solution for cylindrical roller bearings, as external radial load functions, for six different methods: (a) and (b) HA’s, ε = 0.5, ψl = 90°; (c) and (d) 205, 0 < ε < 0.27, 0° < ψl < 62.56°; (e) and (f) 209, 0 < ε < 0.25, 0°< ψl < 60.44°; (g) and (h) 213, ε = 0.5, ψl = 90°. HA-Hamrock and Anderson; OZP-Oswald, Zaretsky and Poplawski.

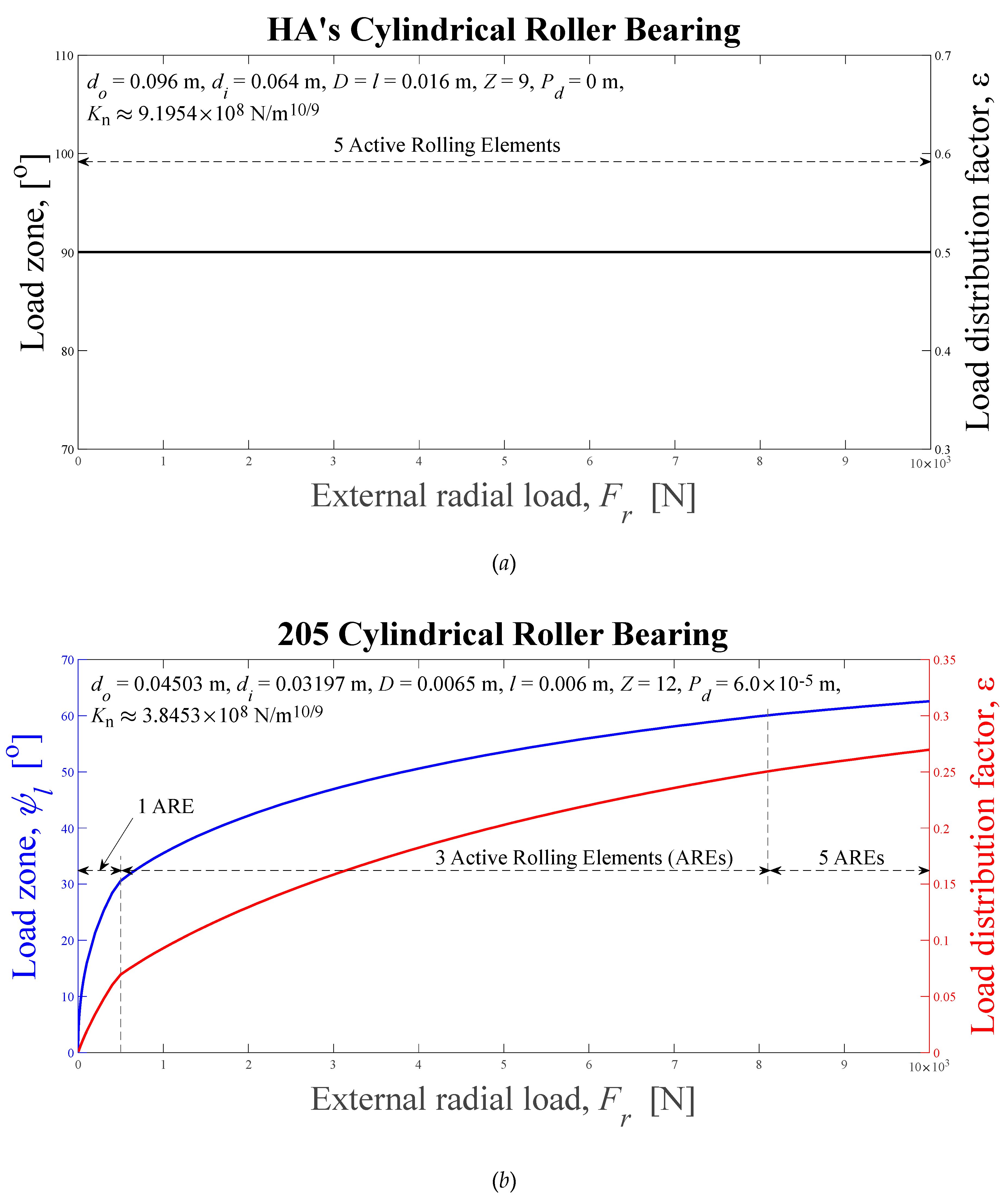

Figure 13.

Load zones, ψl, and load distribution factors, ε, computed using the Eq. (35) solved by Newton-Raphson's scheme, as radial external load functions. (a) HA’s, (b) 205, (c) 209, (d) 213.

Figure 13.

Load zones, ψl, and load distribution factors, ε, computed using the Eq. (35) solved by Newton-Raphson's scheme, as radial external load functions. (a) HA’s, (b) 205, (c) 209, (d) 213.

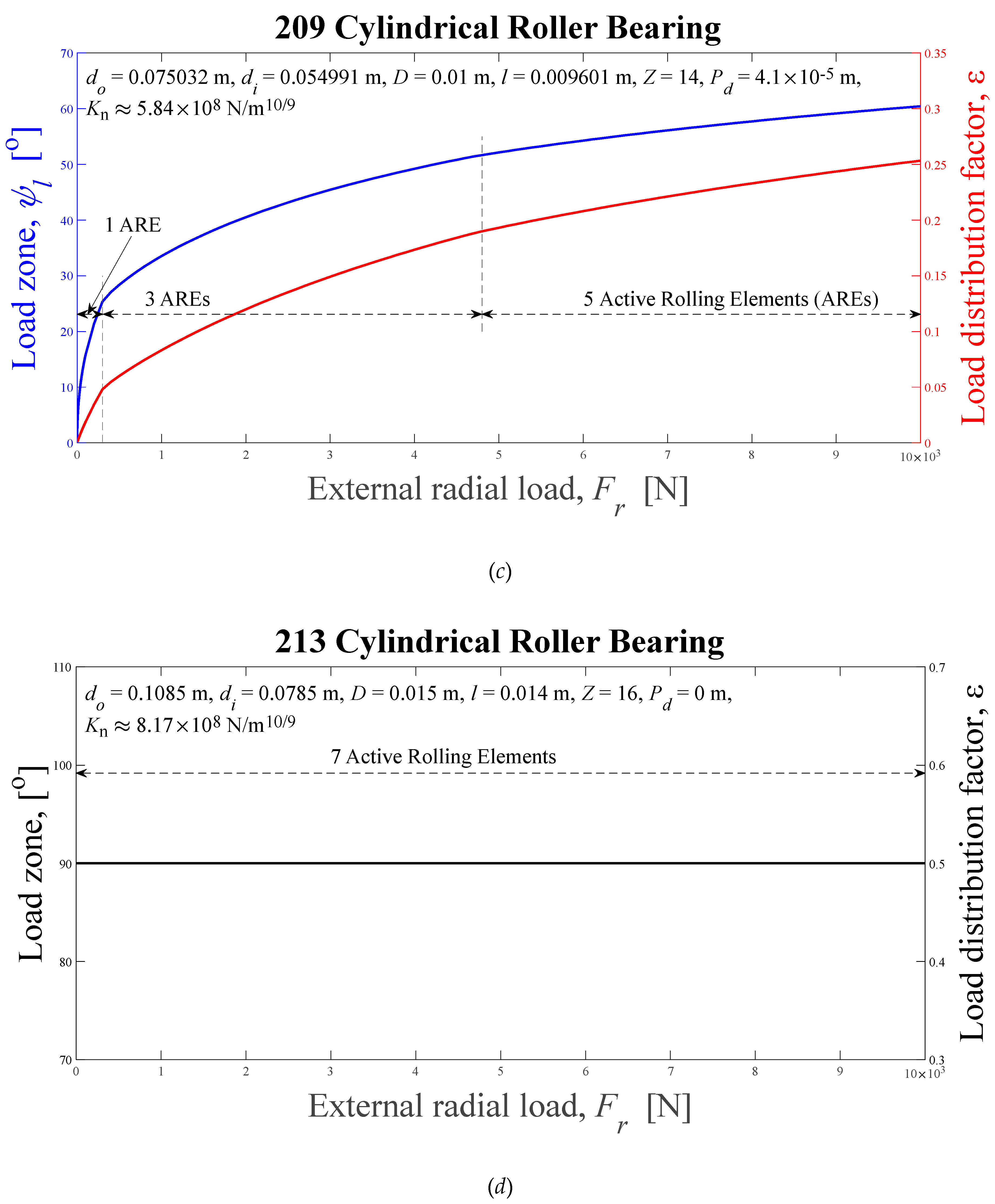

Figure 14.

Absolute relative error differences between the Ricci’s approximation and OZP’s, HA’s, Palmgren’s and Palmgren’s ldf approximations, as external radial load functions, for cylindrical roller bearings: (a) HA’s, (b) 205, (c) 209, (d) 213. HA-Hamrock and Anderson; OZP-Oswald, Zaretsky and Poplawski.

Figure 14.

Absolute relative error differences between the Ricci’s approximation and OZP’s, HA’s, Palmgren’s and Palmgren’s ldf approximations, as external radial load functions, for cylindrical roller bearings: (a) HA’s, (b) 205, (c) 209, (d) 213. HA-Hamrock and Anderson; OZP-Oswald, Zaretsky and Poplawski.

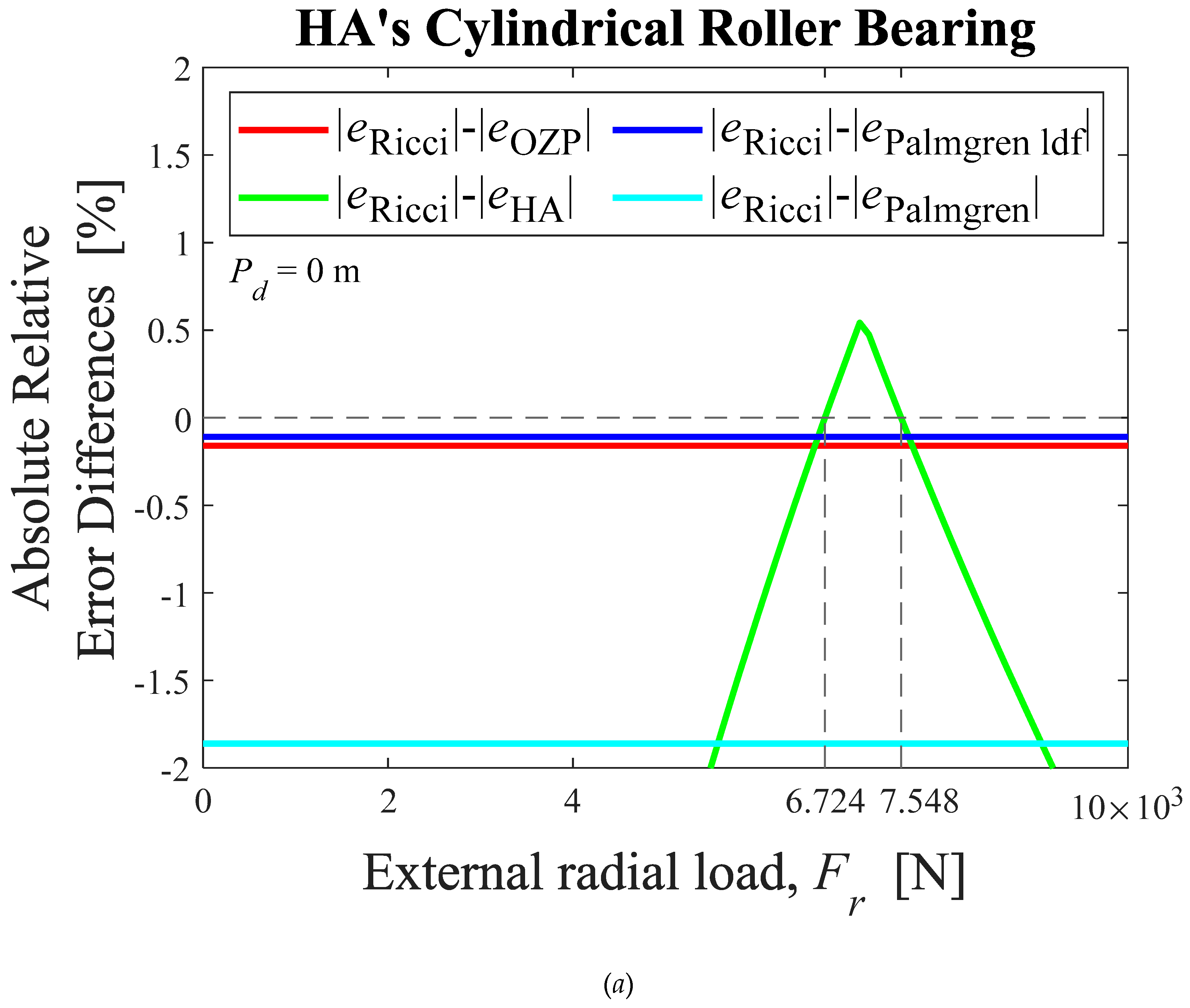

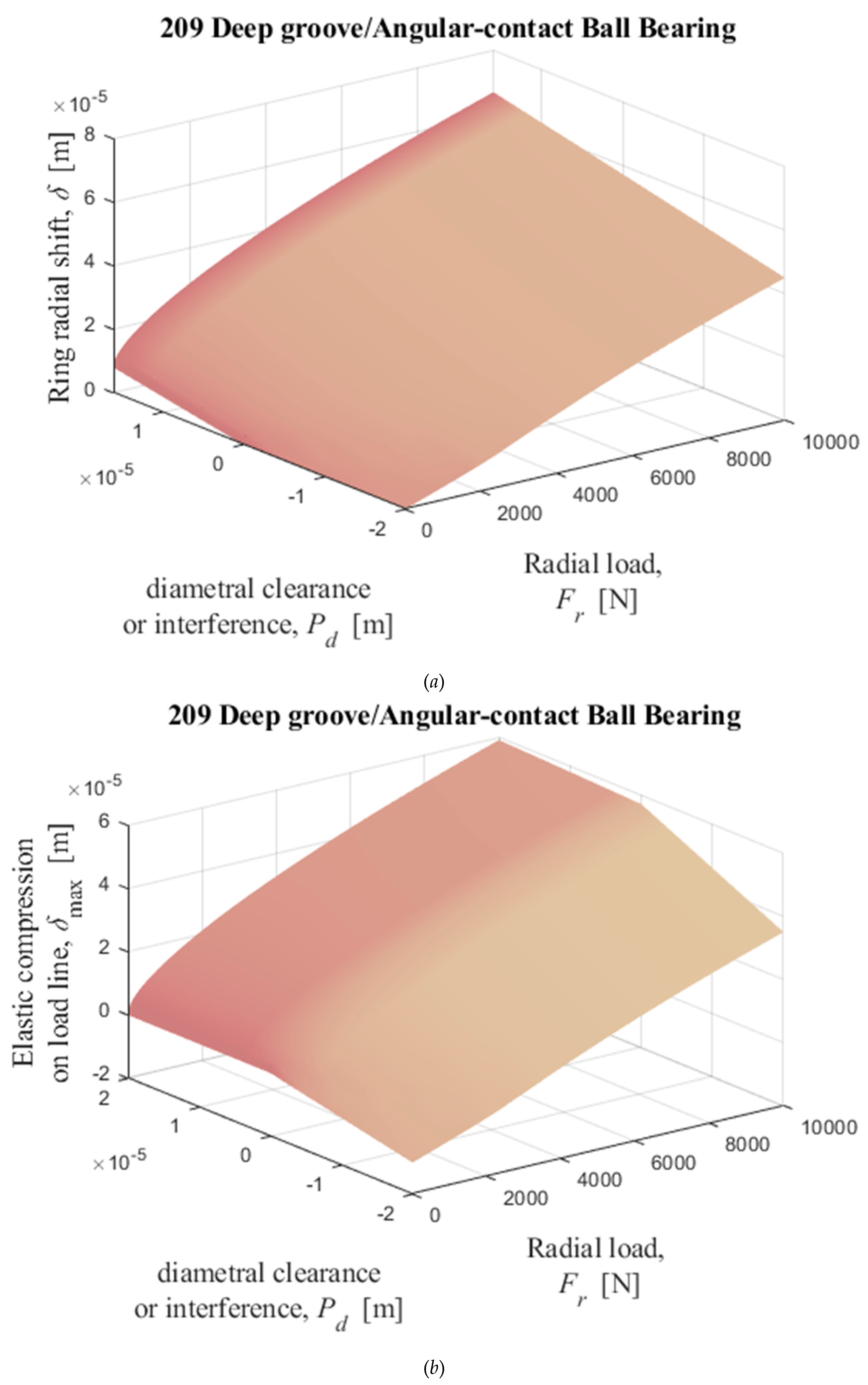

Figure 15.

Numerical solutions of radial displacement of the inner ring with respect to the outer ring, elastic compression on the load line, and normal load on the most loaded ball, obtained by solving iterativelly the equations (35) and (36) with

Table I data as input data. (

a), (

b), and (

c): 209; (

d), (

e), and (

f): 210; (

g), (

h), and (

i): 218.

Figure 15.

Numerical solutions of radial displacement of the inner ring with respect to the outer ring, elastic compression on the load line, and normal load on the most loaded ball, obtained by solving iterativelly the equations (35) and (36) with

Table I data as input data. (

a), (

b), and (

c): 209; (

d), (

e), and (

f): 210; (

g), (

h), and (

i): 218.

Figure 16.

Numerical solutions of radial displacement of the inner ring with respect to the outer ring, elastic compression on the load line, and normal load on the most loaded cylindrical roller obtained by solving iterativelly the equations (35) and (36) with

Table II data as input data. (

a), (

b), and (

c): 205; (

d), (

e), and (

f): 209; (

g), (

h), and (

i): 213.

Figure 16.

Numerical solutions of radial displacement of the inner ring with respect to the outer ring, elastic compression on the load line, and normal load on the most loaded cylindrical roller obtained by solving iterativelly the equations (35) and (36) with

Table II data as input data. (

a), (

b), and (

c): 205; (

d), (

e), and (

f): 209; (

g), (

h), and (

i): 213.