Submitted:

05 December 2023

Posted:

07 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

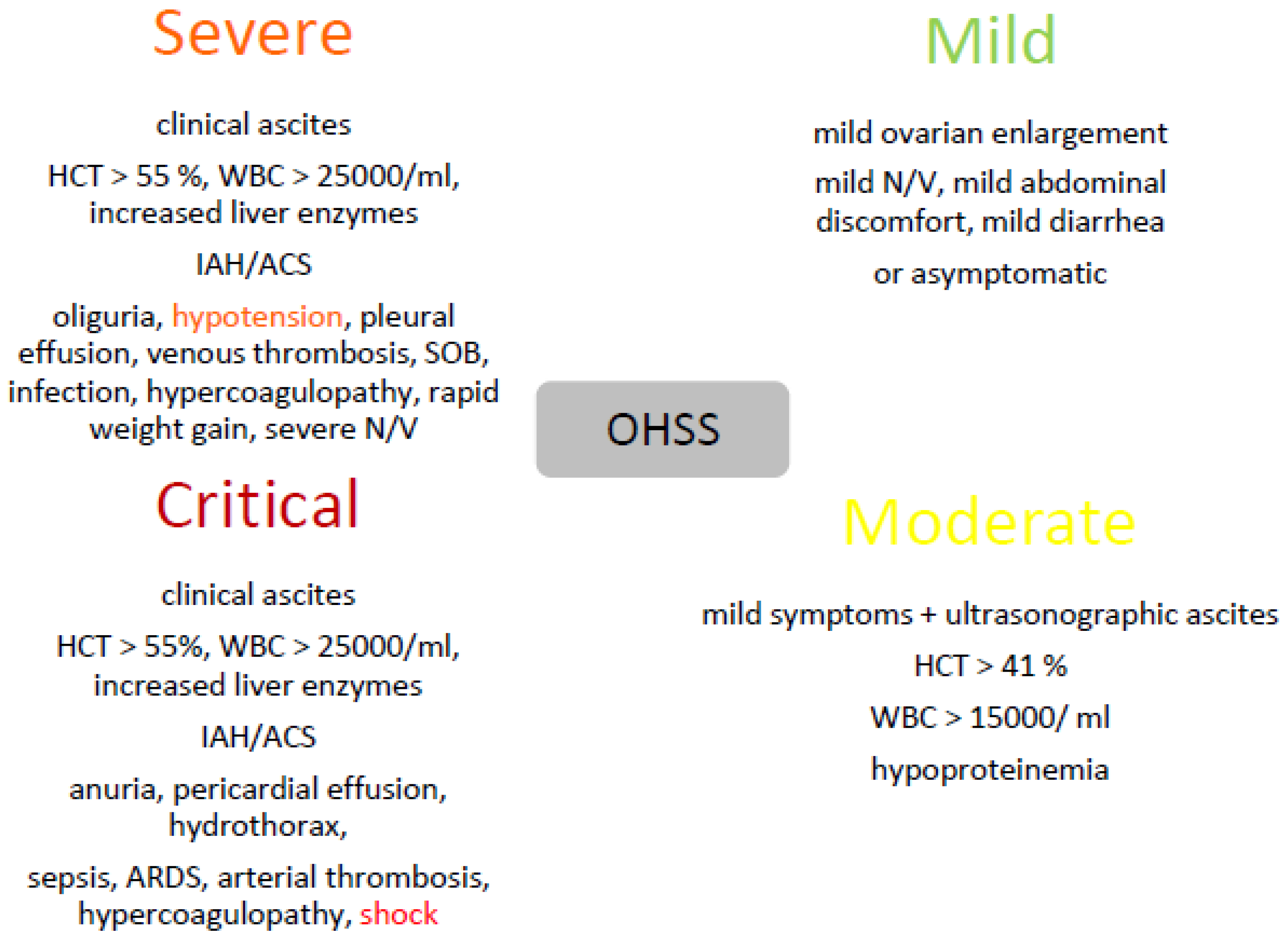

2. OHSS

2.1. Third Spacing Phenomenon

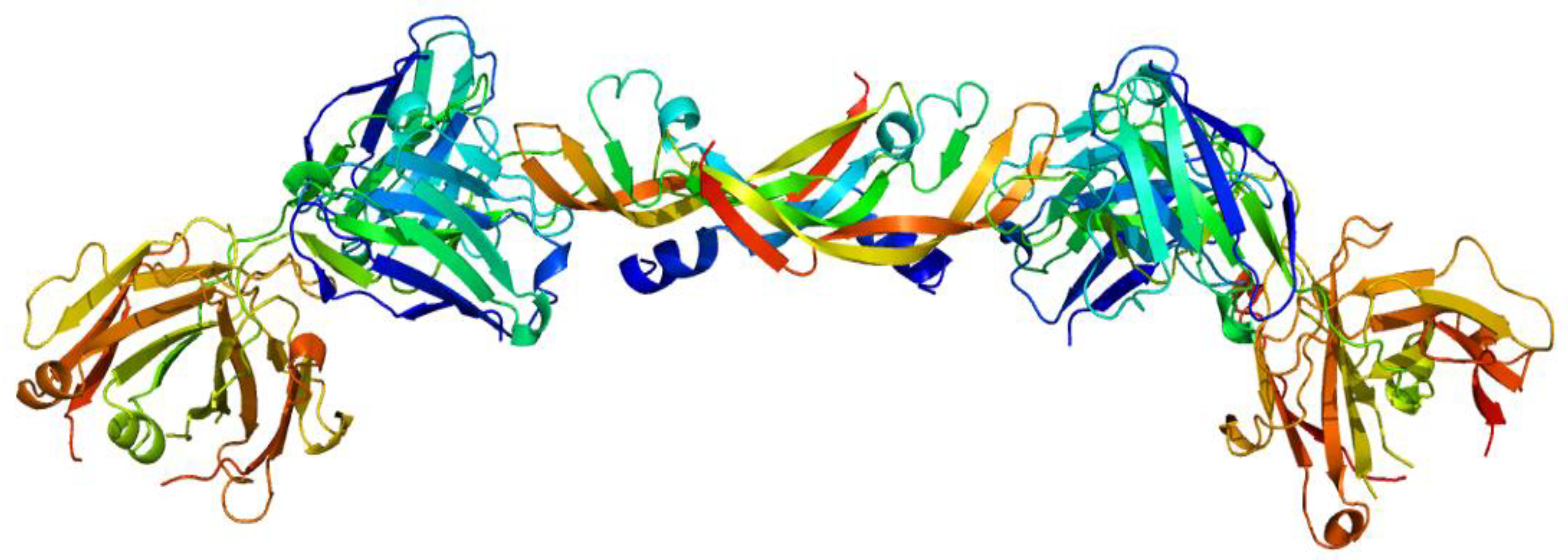

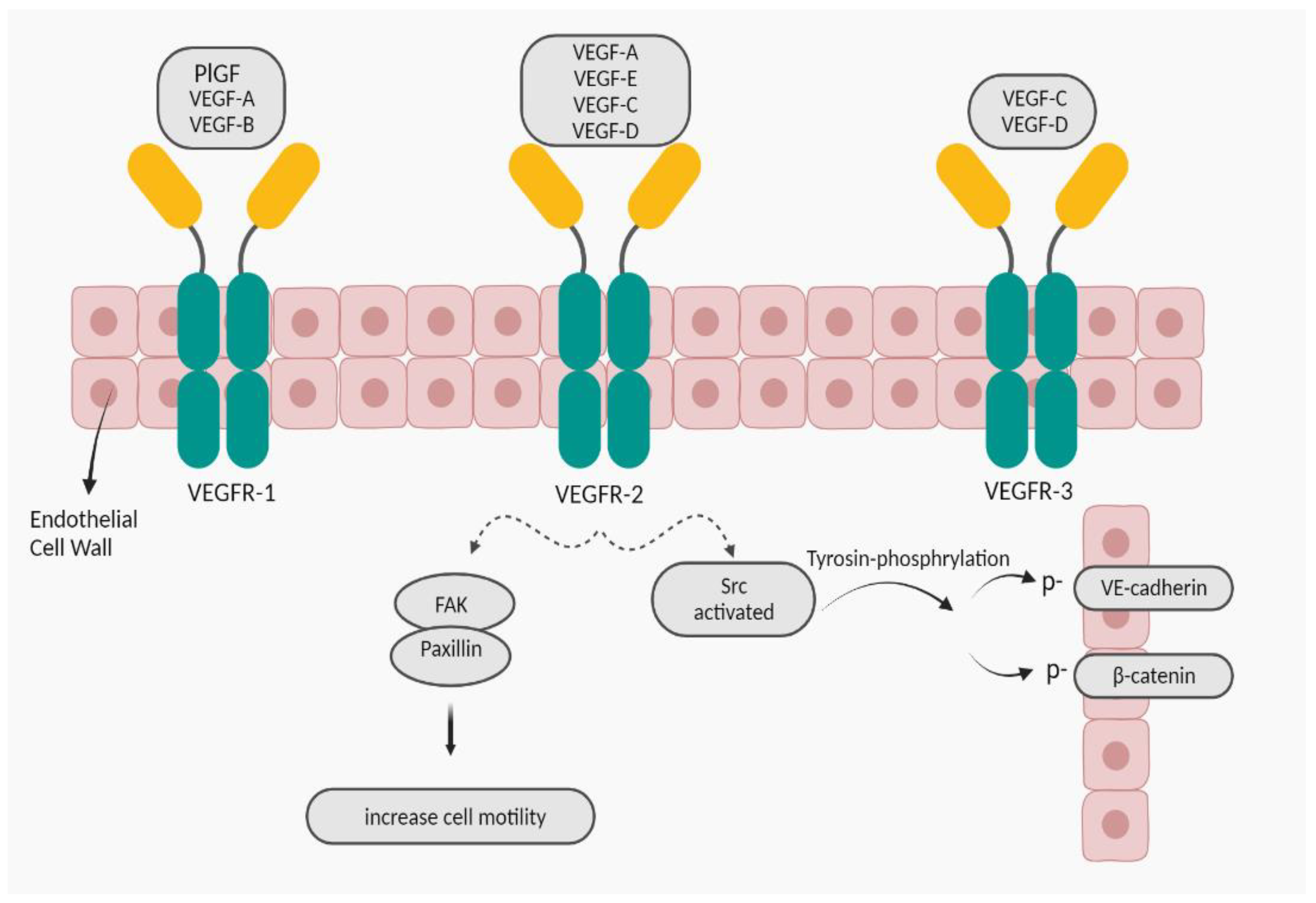

2.1.1. VEGF

2.1.1.1. VEGF-A; Increasing Vascular Permeability

3. Obesity

3.1. Adipose Tissue

3.1.1. VEGF-A, Angiogenesis

4. Conclusion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farkas B, Boldizsar F, Bohonyi N, Farkas N, Marczi S, Kovacs GL, et al. Comparative analysis of abdominal fluid cytokine levels in ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). Journal of Ovarian Research. 2020;13(1):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Timmons D, Montrief T, Koyfman A, Long B. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: a review for emergency clinicians. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2019;37(8):1577-84. [CrossRef]

- Hazlina NHN, Norhayati MN, Bahari IS, Arif NANM. Worldwide prevalence, risk factors and psychological impact of infertility among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open. 2022;12(3):e057132. [CrossRef]

- Sharma R, Biedenharn KR, Fedor JM, Agarwal A. Lifestyle factors and reproductive health: taking control of your fertility. Reproductive biology and endocrinology. 2013;11(1):1-15. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Fu Y, Tang M, Yan H, Zhang F, Hu X, et al. Risk of Higher Blood Pressure in 3 to 6 Years Old Singleton Born From OHSS Patients Undergone With Fresh IVF/ICSI. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2022;13. [CrossRef]

- Chen M, Heilbronn L. The health outcomes of human offspring conceived by assisted reproductive technologies (ART). Journal of developmental origins of health and disease. 2017;8(4):388-402. [CrossRef]

- Fang L, Yu Y, Li Y, Wang S, He J, Zhang R, et al. Upregulation of AREG, EGFR, and HER2 contributes to increased VEGF expression in granulosa cells of patients with OHSS. Biology of reproduction. 2019;101(2):426-32. [CrossRef]

- Christ J, Herndon CN, Yu B. Severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome associated with long-acting GnRH agonist in oncofertility patients. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 2021;38(3):751-6. [CrossRef]

- Akalewold M, Yohannes GW, Abdo ZA, Hailu Y, Negesse A. Magnitude of infertility and associated factors among women attending selected public hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Women's Health. 2022;22(1):1-11. [CrossRef]

- Jahromi BN, Parsanezhad ME, Shomali Z, Bakhshai P, Alborzi M, Vaziri NM, et al. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: a narrative review of its pathophysiology, risk factors, prevention, classification, and management. Iranian journal of medical sciences. 2018;43(3):248.

- Liu F, Jiang Q, Sun X, Huang Y, Zhang Z, Han T, et al. Lipid metabolic disorders and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: a retrospective analysis. Frontiers in Physiology. 2020;11:491892. [CrossRef]

- Humaidan P, Nelson S, Devroey P, Coddington C, Schwartz L, Gordon K, et al. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: review and new classification criteria for reporting in clinical trials. Human Reproduction. 2016;31(9):1997-2004. [CrossRef]

- Sun B, Ma Y, Li L, Hu L, Wang F, Zhang Y, et al. Factors associated with ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) severity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing IVF/ICSI. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2021;11:615957. [CrossRef]

- Abbara A, Islam R, Clarke S, Jeffers L, Christopoulos G, Comninos A, et al. Clinical parameters of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome following different hormonal triggers of oocyte maturation in IVF treatment. Clinical endocrinology. 2018;88(6):920-7. [CrossRef]

- Bergandi L, Canosa S, Carosso AR, Paschero C, Gennarelli G, Silvagno F, et al. Human recombinant FSH and its Biosimilars: clinical efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness in controlled ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization. Pharmaceuticals. 2020;13(7):136. [CrossRef]

- Braam S, de Bruin J, Mol B, van Wely M. The perspective of women with an increased risk of OHSS regarding the safety and burden of IVF: a discrete choice experiment. Human reproduction open. 2020;2020(2):hoz034. [CrossRef]

- Pakhomov S, Orlova V, Verzilina I, Sukhih N, Nagorniy A, Matrosova A. Risk Factors and Methods for Predicting Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome (OHSS) in the in vitro Fertilization. Archives of Razi Institute. 2021;76(5):1461-8. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Qian Y, Pei Y, Wu K, Lu S. Coagulation and Fibrinolysis Biomarkers as Potential Indicators for the Diagnosis and Classification of Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome. Frontiers in Medicine. 2021:1430. [CrossRef]

- Claesson-Welsh, L. Vascular permeability—the essentials. Upsala journal of medical sciences. 2015;120(3):135-43. [CrossRef]

- Wautier J-L, Wautier M-P. Vascular Permeability in Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(7):3645. [CrossRef]

- Liu K, Yang W, Hu M, Xie W, Huang J, Cui M, et al. Exosomal miR-27 negatively regulates ROS production and promotes granulosa cells apoptosis by targeting SPRY2 in OHSS. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2021;25(8):3976-90. [CrossRef]

- Elchalal U, Schenker JG. The pathophysiology of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome--views and ideas. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 1997;12(6):1129-37. [CrossRef]

- Morris RS, Wong IL, Do YS, Hsueh WA, Lobo RA, Sauer MV, et al. The Pathophysiology of Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome (OHSS). Tissue Renin-Angiotensin Systems. 1995:391-8. [CrossRef]

- Elmahal M, Lohana P, Anvekar P, Menda MK. Hyponatremia: An Untimely Finding in Ovarian Hyper-Stimulation Syndrome. Cureus. 2021;13(7). [CrossRef]

- Medicine PCotASfR. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertility and sterility. 2008;90(5):S188-S93. [CrossRef]

- Bates DO. Vascular endothelial growth factors and vascular permeability. Cardiovascular research. 2010;87(2):262-71. [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki Y, Matsunaga Y, Tokunaga Y, Obayashi S, Saito M, Morita T. Snake venom Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors (VEGF-Fs) exclusively vary their structures and functions among species. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(15):9885-91. [CrossRef]

- Senger DR, Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, Perruzzi CA, Harvey VS, Dvorak HF. Tumor cells secrete a vascular permeability factor that promotes accumulation of ascites fluid. Science. 1983;219(4587):983-5. [CrossRef]

- Claesson-Welsh L, Welsh M. VEGFA and tumour angiogenesis. Journal of internal medicine. 2013;273(2):114-27. [CrossRef]

- Bokhari SMZ, Hamar P. Vascular endothelial growth factor-D (VEGF-D): An angiogenesis bypass in malignant tumors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023;24(17):13317. [CrossRef]

- Shibuya M. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor (VEGFR) signaling in angiogenesis: a crucial target for anti-and pro-angiogenic therapies. Genes & cancer. 2011;2(12):1097-105. [CrossRef]

- Shibuya M, Yamaguchi S, Yamane A, Ikeda T, Tojo A, Matsushime H, et al. Nucleotide sequence and expression of a novel human receptor-type tyrosine kinase gene (flt) closely related to the fms family. Oncogene. 1990;5(4):519-24.

- Claesson-Welsh, L. VEGF-B taken to our hearts: specific effect of VEGF-B in myocardial ischemia. Am Heart Assoc; 2008. p. 1575-6. [CrossRef]

- Van Bergen T, Etienne I, Cunningham F, Moons L, Schlingemann RO, Feyen JH, et al. The role of placental growth factor (PlGF) and its receptor system in retinal vascular diseases. Progress in retinal and eye research. 2019;69:116-36. [CrossRef]

- Chen XL, Nam J-O, Jean C, Lawson C, Walsh CT, Goka E, et al. VEGF-induced vascular permeability is mediated by FAK. Developmental cell. 2012;22(1):146-57. [CrossRef]

- Adam AP, Sharenko AL, Pumiglia K, Vincent PA. Src-induced Tyrosine Phosphorylation of VE-cadherin Is Not Sufficient to Decrease Barrier Function of Endothelial Monolayers*♦. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(10):7045-55. [CrossRef]

- Abedi H, Zachary I. Vascular endothelial growth factor stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation and recruitment to new focal adhesions of focal adhesion kinase and paxillin in endothelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(24):15442-51. [CrossRef]

- Elias I, Franckhauser S, Bosch F. New insights into adipose tissue VEGF-A actions in the control of obesity and insulin resistance. Adipocyte. 2013;2(2):109-12. [CrossRef]

- Tzenios, N. OBESITY AS A RISK FACTOR FOR DIFFERENT TYPES OF CANCER. EPRA International Journal of Research and Development (IJRD). 2023;8(2):97-100. [CrossRef]

- Lobstein T, Brinsden H, Neveux M. World obesity atlas 2022. 2022.

- Wen X, Zhang B, Wu B, Xiao H, Li Z, Li R, et al. Signaling pathways in obesity: mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2022;7(1):298. [CrossRef]

- AlZaim I, de Rooij LP, Sheikh BN, Börgeson E, Kalucka J. The evolving functions of the vasculature in regulating adipose tissue biology in health and obesity. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2023:1-17. [CrossRef]

- Kim C, Fryar C, Ogden CL. Epidemiology of obesity. Handbook of epidemiology: Springer; 2023. p. 1-47. [CrossRef]

- Hu FB. Obesity in the USA: diet and lifestyle key to prevention. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2023;11(9):642-3. [CrossRef]

- Organization WH. WHO European regional obesity report 2022: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; 2022.

- Elkhawaga SY, Ismail A, Elsakka EG, Doghish AS, Elkady MA, El-Mahdy HA. miRNAs as cornerstones in adipogenesis and obesity. Life Sciences. 2023:121382. [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D. Perspective: Obesity—an unexplained epidemic. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2022;115(6):1445-50. [CrossRef]

- Purnell, JQ. Definitions, classification, and epidemiology of obesity. Endotext [Internet]. 2023.

- Mahmoud R, Kimonis V, Butler MG. Genetics of obesity in humans: A clinical review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(19):11005. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, AM. An overview of epigenetics in obesity: The role of lifestyle and therapeutic interventions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(3):1341. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus E, Bays HE. Cancer and obesity: an obesity medicine association (OMA) clinical practice statement (CPS) 2022. Obesity Pillars. 2022;3:100026. [CrossRef]

- Masood B, Moorthy M. Causes of obesity: a review. Clinical Medicine. 2023;23(4):284. [CrossRef]

- Sørensen TI, Martinez AR, Jørgensen TSH. Epidemiology of obesity. From Obesity to Diabetes: Springer; 2022. p. 3-27. [CrossRef]

- Nijhawans P, Behl T, Bhardwaj S. Angiogenesis in obesity. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2020;126:110103. [CrossRef]

- Martin WP, Le Roux C. Obesity is a disease. Bariatric Surgery in Clinical Practice. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Loos RJ, Yeo GS. The genetics of obesity: from discovery to biology. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2022;23(2):120-33. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh SS, Ferreira T, Benonisdottir S, Rahmioglu N, Becker CM, Granne I, et al. Obesity and risk of female reproductive conditions: A Mendelian randomisation study. PLoS medicine. 2022;19(2):e1003679. [CrossRef]

- Langley-Evans SC, Pearce J, Ellis S. Overweight, obesity and excessive weight gain in pregnancy as risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes: a narrative review. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 2022;35(2):250-64. [CrossRef]

- Creanga AA, Catalano PM, Bateman BT. Obesity in pregnancy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2022;387(3):248-59. [CrossRef]

- Corvera S, Solivan-Rivera J, Yang Loureiro Z. Angiogenesis in adipose tissue and obesity. Angiogenesis. 2022;25(4):439-53. [CrossRef]

- Lustig RH, Collier D, Kassotis C, Roepke TA, Kim MJ, Blanc E, et al. Obesity I: Overview and molecular and biochemical mechanisms. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2022;199:115012. [CrossRef]

- Horwitz A, Birk R. Adipose Tissue Hyperplasia and Hypertrophy in Common and Syndromic Obesity—The Case of BBS Obesity. Nutrients. 2023;15(15):3445. [CrossRef]

- Lemoine AY, Ledoux S, Larger E. Adipose tissue angiogenesis in obesity. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2013;110(10):661-9. [CrossRef]

- Fitch AK, Bays HE. Obesity definition, diagnosis, bias, standard operating procedures (SOPs), and telehealth: an Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) Clinical Practice Statement (CPS) 2022. Obesity Pillars. 2022;1:100004. [CrossRef]

- Corvera S, Gealekman O. Adipose tissue angiogenesis: impact on obesity and type-2 diabetes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease. 2014;1842(3):463-72. [CrossRef]

- Zhou W, Liu K, Zeng L, He J, Gao X, Gu X, et al. Targeting VEGF-A/VEGFR2 Y949 signaling-mediated vascular permeability alleviates hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2022;146(24):1855-81. [CrossRef]

- Herold J, Kalucka J. Angiogenesis in adipose tissue: the interplay between adipose and endothelial cells. Frontiers in physiology. 2021;11:624903. [CrossRef]

| PCOS |

| AFC > 8 |

| Age < 30 |

| AMH > 3.36 ng/ml |

| Low BMI |

| Previous OHSS |

| Serum estradiol levels > 2500 pg/ml during COH |

| Small ovarian follicle count > 14 |

| A large number of retrieved oocytes > 20 |

| hCG administration |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).