Submitted:

05 December 2023

Posted:

06 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

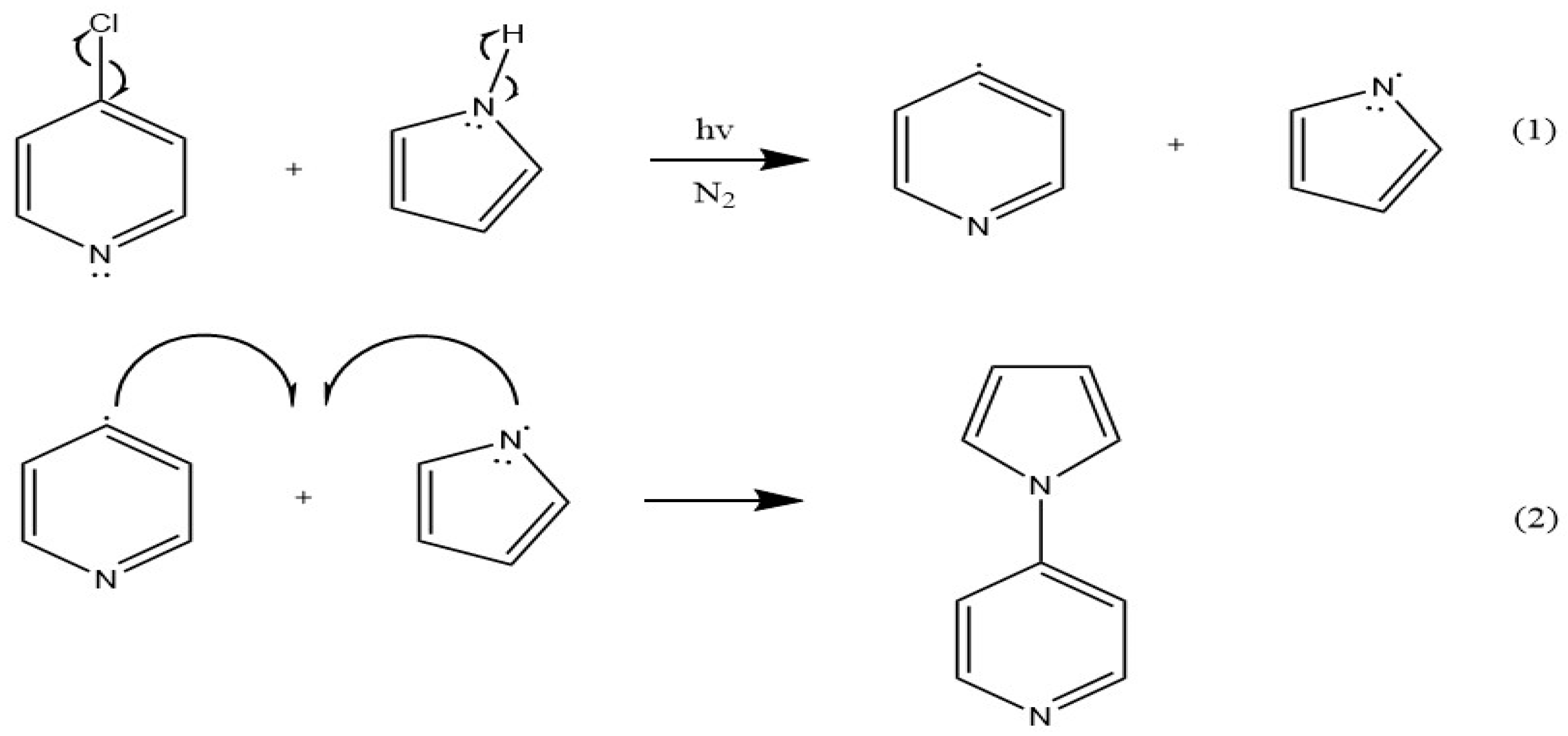

2.2. Synthesis of 4(pyrrol-1-yl)pyridine

2.3. Instrumentation and Procedures

2.4. Titration with 1 x 10-2 M sodium nitrite (aq.)

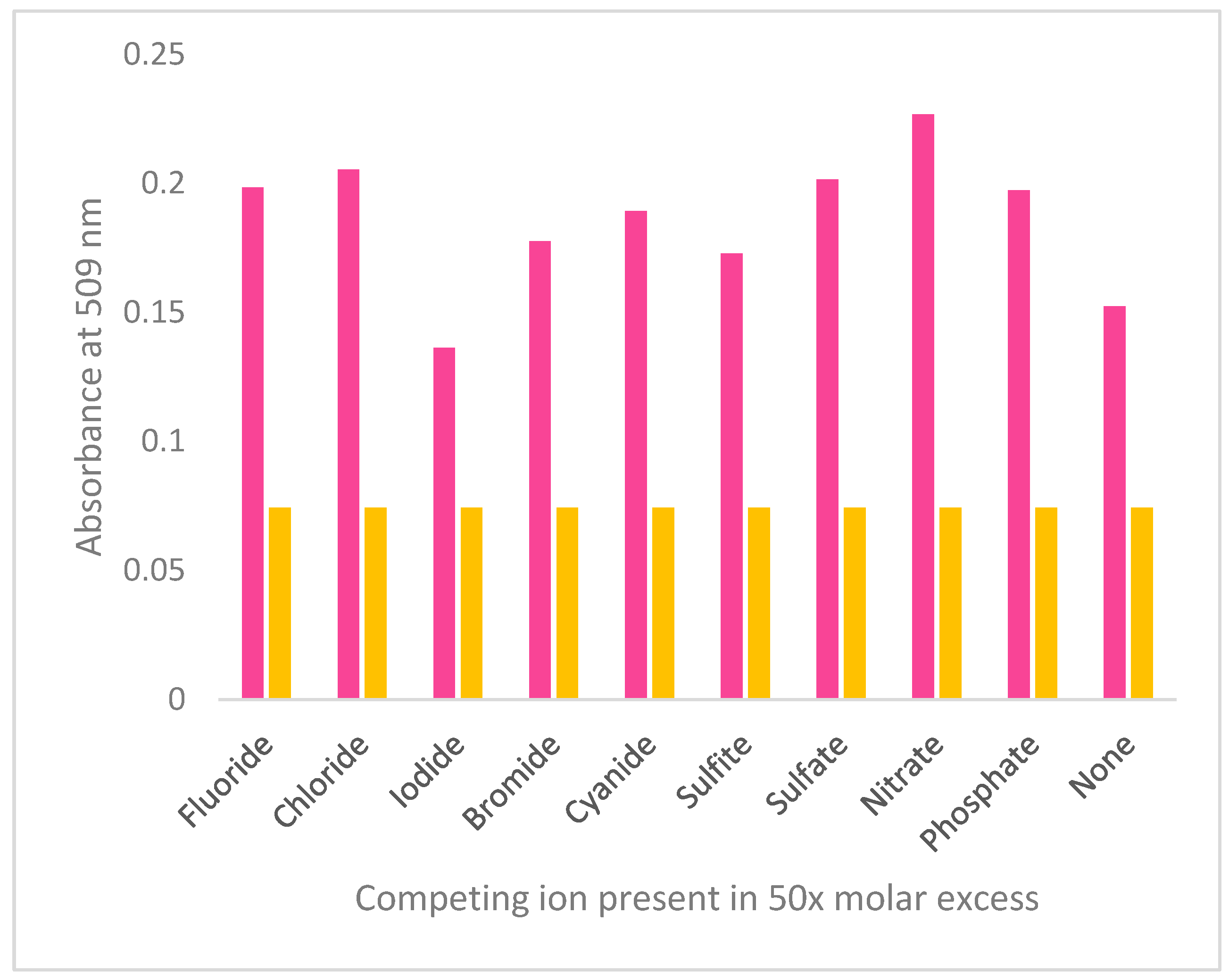

2.5. Competitive anion titrations

2.6. Dynamic Light Scattering

2.7. Tyndall Effect

3. Results and Discussion

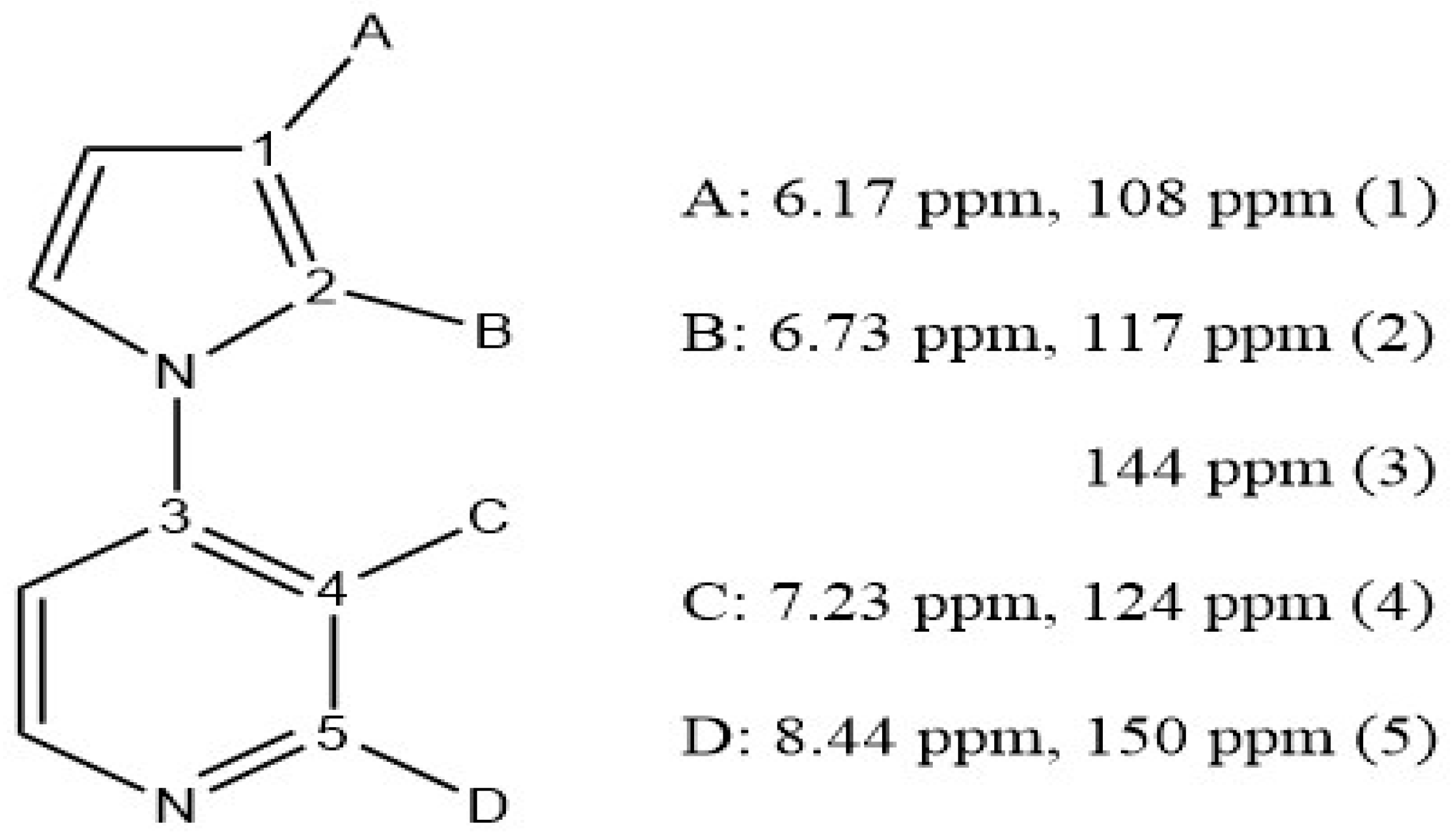

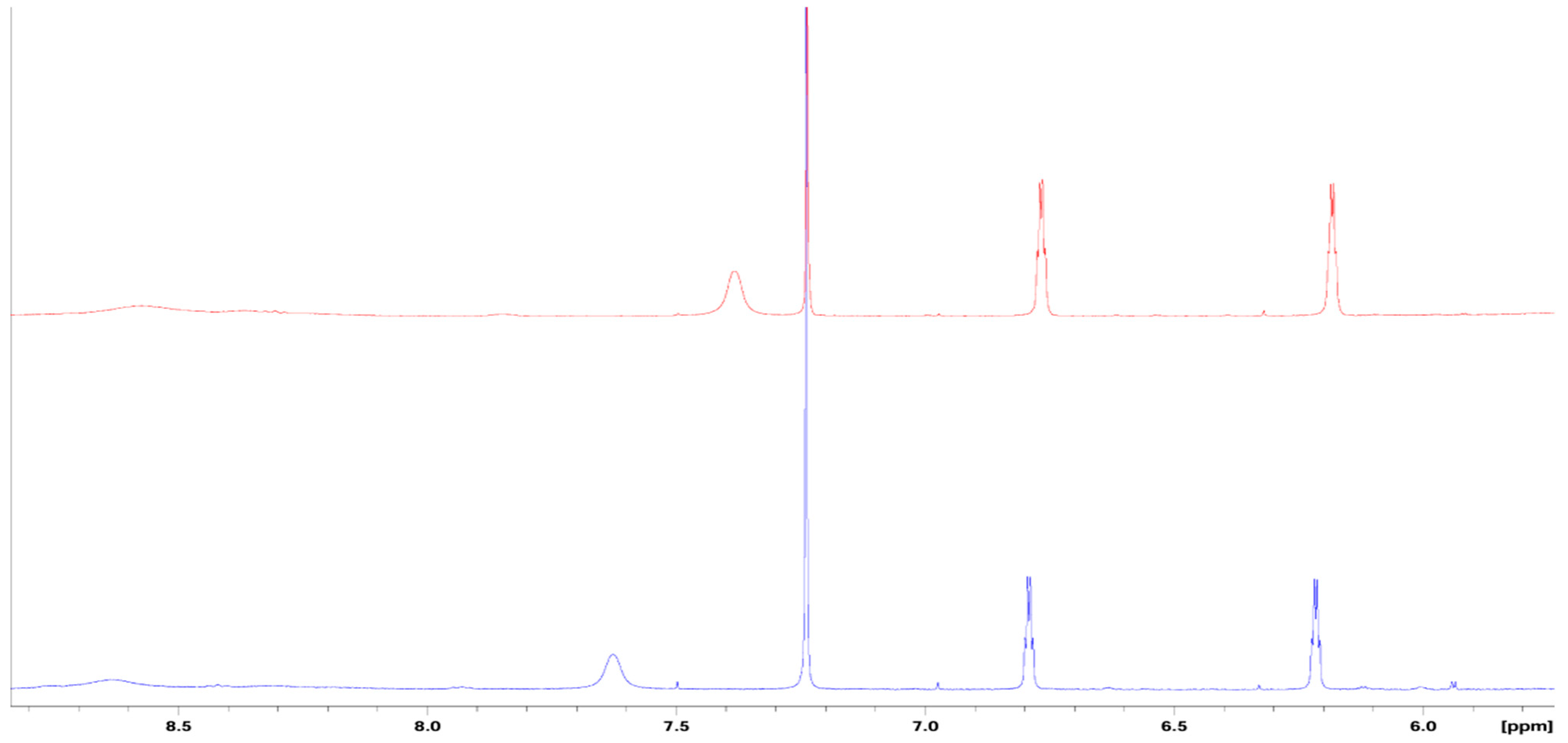

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of 4(pyrrol-1-yl)pyridine

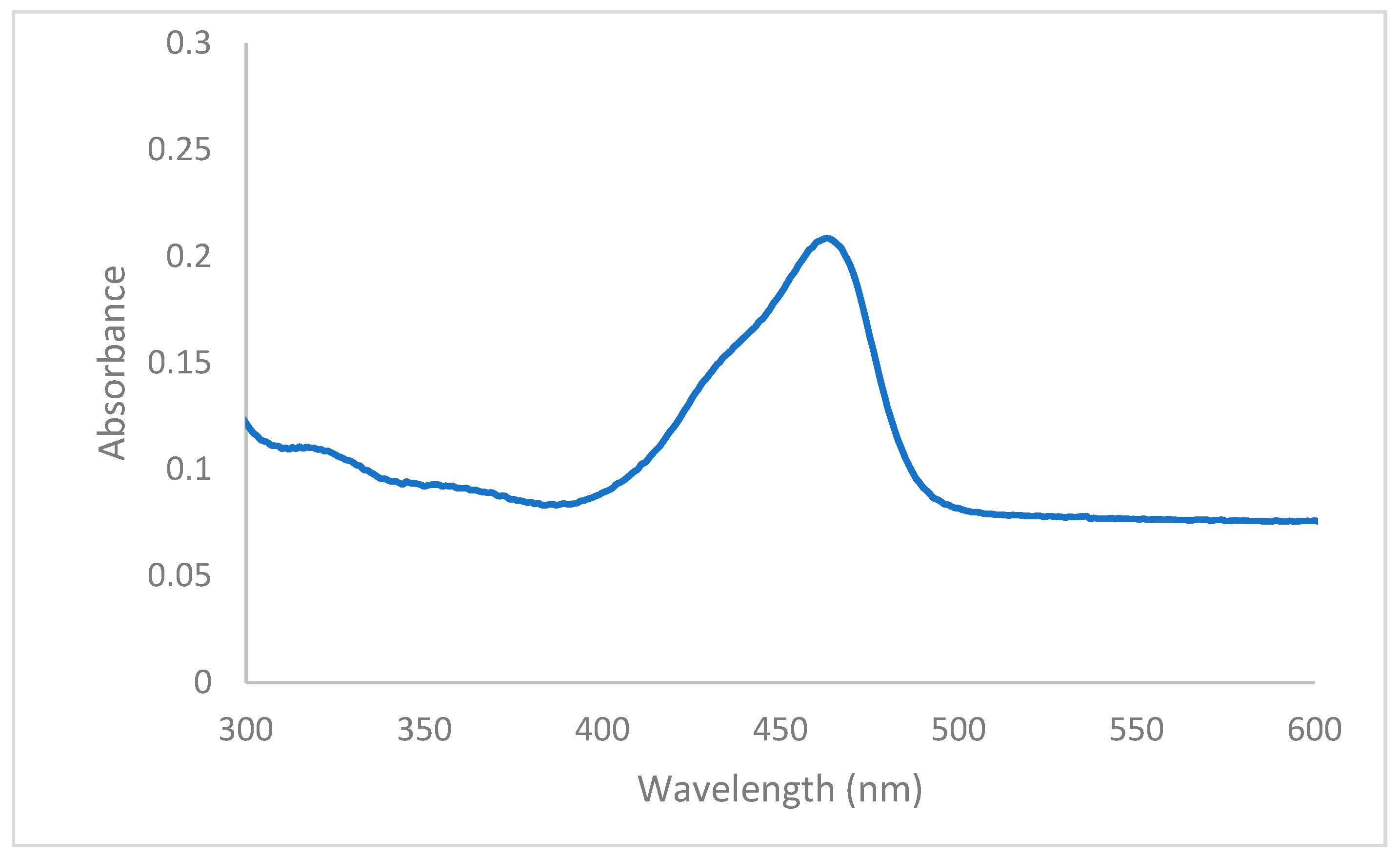

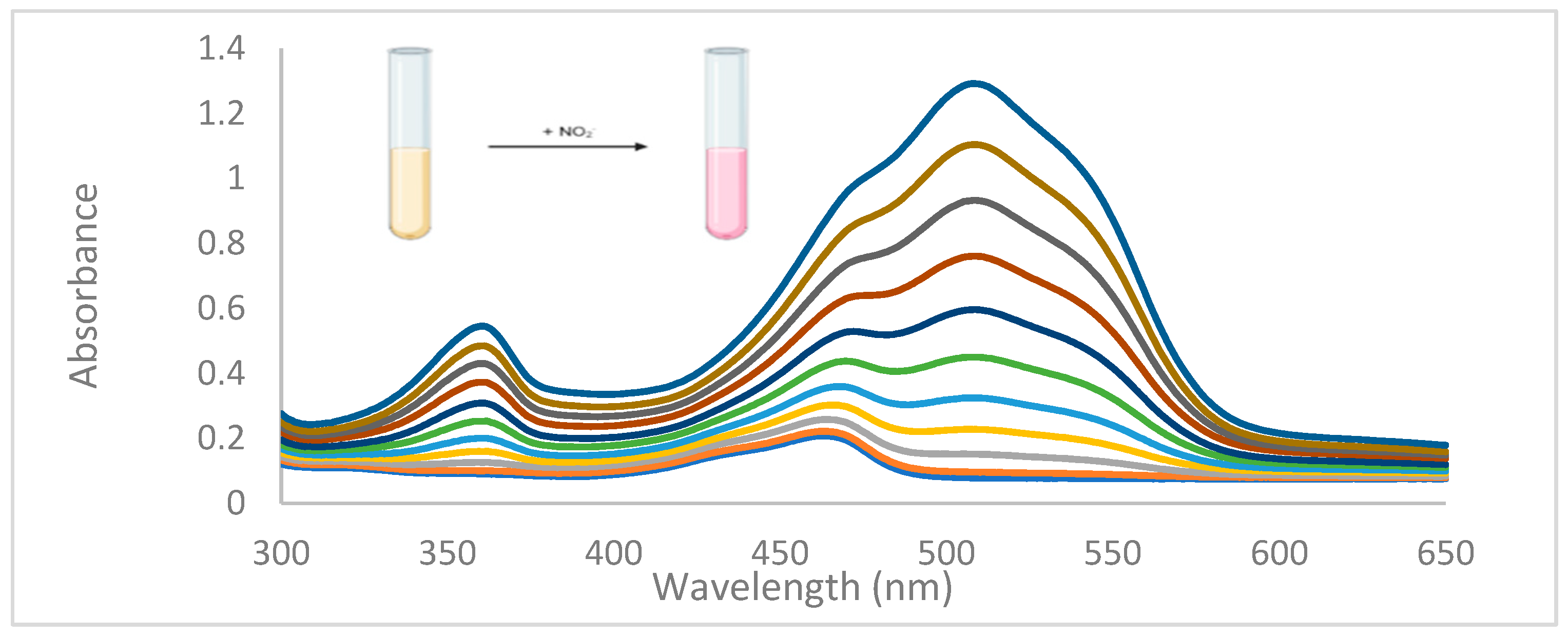

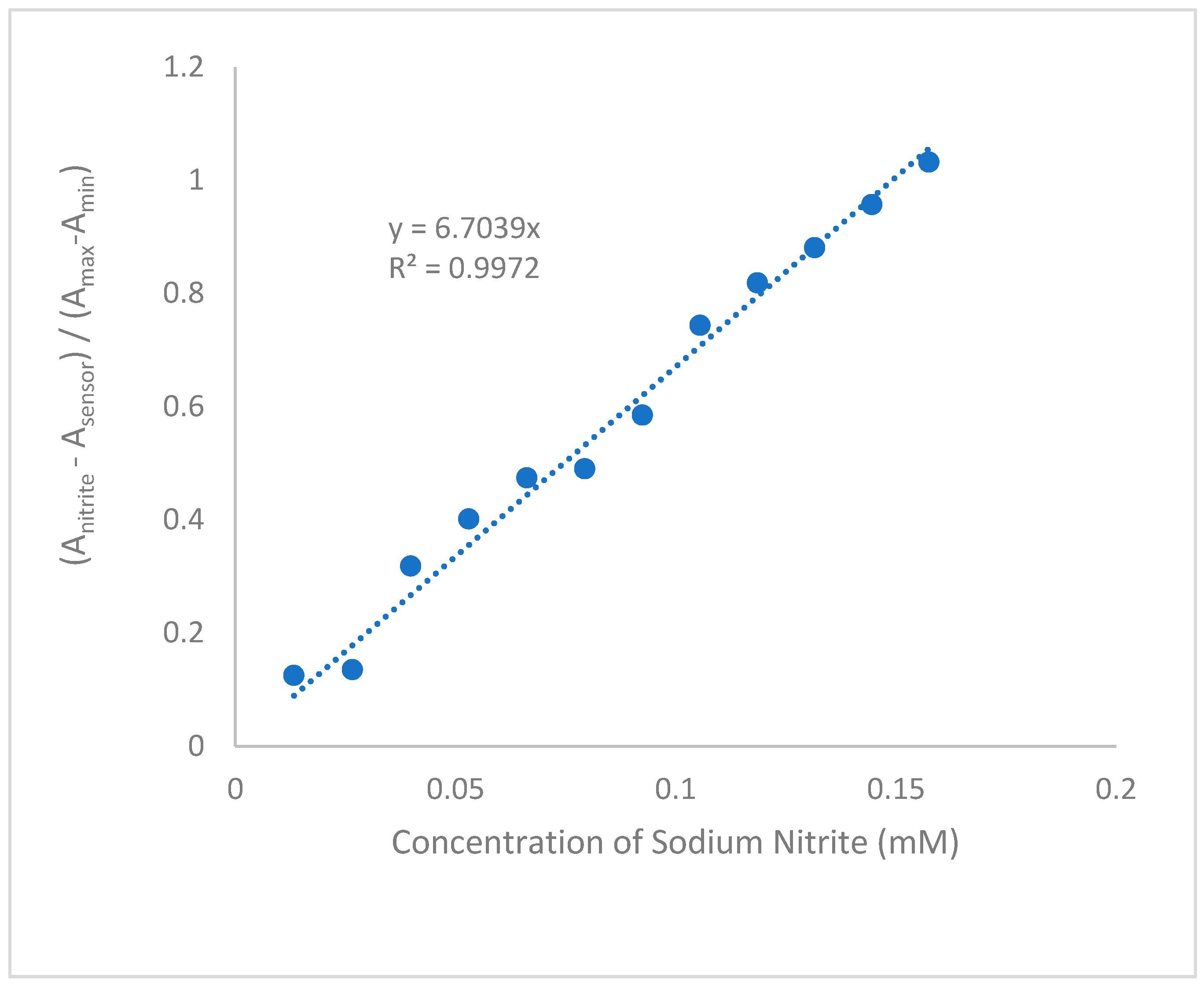

3.2. Anion Sensing by 4(pyrrol-1-yl)pyridine

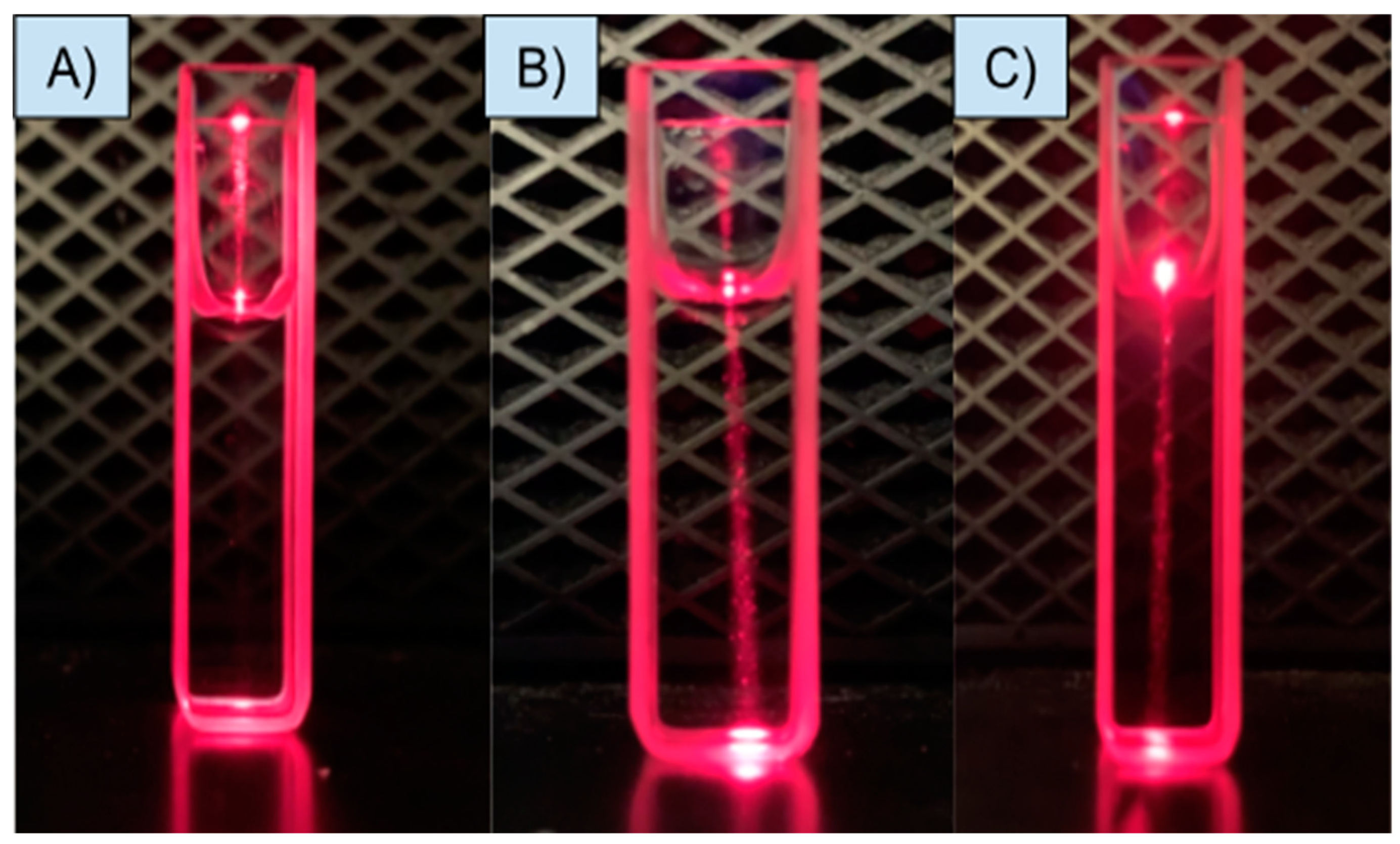

3.3. Possible mechanism of sensing

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. National Primary Drinking Water Regulations: Contaminant Specific Fact Sheets, Inorganic Chemicals, consumer version; Washington DC, 1995.

- Moorcroft, M.J.; Davis, J.; Compton, R.G. Talanta, 2001, 54, 785-803. [CrossRef]

- Fanning, J.C. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2000, 199, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nollet, L.M.L.Handbook of Water Analysis, 2000.

- Guidelines for drinking water quality, 2nd ed. Addendum to Vol. 2. Health criteria and other supporting information. World Health Organization, Geneva, 1998.

- Rajasulochana, P.; Ganesan, Y.; Kumar, P.S.; Mahalazmi, S.; Tasneem, F.; Ponnuchamy, M.; Kapoor, A. Paper-Based Microfluidic Colorimetric Sensor on a 3D Printed Support for Quantitative Detection of Nitrite in Aquatic Environments. Environmental Research, 2022, 208, 112745. [CrossRef]

- Burt, T.P.; Howden, N.J.K.; Worral, F.; Whelan, M.J. Long-term monitoring of river water nitrate: how much data do we need? J. Environ. Monit. 2010, 12, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, S.R.; Caraco, N.F.; Correll, D.L.; Howarth, R.W.; Sharpley, A.N.; Smit, V.H. Nonpoint pollution of surface waters with phosphorus and nitrogen. Ecol. Appl. 1998, 8. 559-568. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.C.; Di, H.J.; Moir, J.L. Nitrogen losses from the soil/plant system: a review. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2013, 162, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, H.; Harris, N.R.; Merrett, G.V.; Rivers, M.; Coles, N. The impact of agricultural activities on water quality: A case for collaborative catchment-scale management using integrated wireless sensor networks. Comput. Electron. Agr. 2013, 96, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Ahn, M.S.; Hahn, Y.B. A highly sensitive nonenzymatic sensor based on Fe2O3 nanoparticle coated ZnO nanorods for electrochemical detection of nitrite. Adv. Mater. Interfaces, 2017, 4, 1700691-1700700. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.R.; Kong, F.Y.; Liu, J; Liang, T.M; Xu, J.J; Chen, H.Y. Synthesis of Potassium-Modified Graphene and its Application in Nitrite-Selective Sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 1981-1988. [CrossRef]

- Ye.D.; Luo, L.; Chen, Q.; Liu, X. A novel nitrite sensor based on graphene/polypyrrole/chitosan nanocomposite modified glassy carbon electrode. Analyst. 2011, 136, 4563-4569.

- Zuane, J.D. Handbook of Drinking Water Quality, 2nd ed.; 1996.

- Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Hu, Z.; Li, X.; Ding, T.; Hou, X.; Chen, Z.; Ye, Z.; Luo, R. Ni(NO3)2- induced high electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance of self-supported fold like WC coating on carbon fiber paper prepared through molten salt method, Electrochem. Acta. 2022, 422, 140553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhe, T.; Li, R.; Li, F.; Liang, S.; Shi, D.; Sun, X.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Bu, T,; Want, L. Surface Engineering of Carbon Selenide Nanofilms on Carbon Cloth: An Advanced and Ultrasensitive Self- Supporting Binder-Free Electrode for Nitrite Sensing. Food Chem. 2021, 340, 127953. 140553. [CrossRef]

- Sihto, H.M.; Budi Susila, Y.; Tasara, T.; Radstrom, P.; Stephan, R.; Schelin, J.; Johler, S. Effect of Sodium Nitrite and Regulatory Mutations Δagr, ΔsarA, and ΔsigB on the MRNA and Protein Levels of Staphylococcal Enteroxtoxin. D. Food Control. 2016, 65, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyuz, M.; Ata, S. Determination of Low-Level Nitrite and Nitrate in Biological, Food, and Environmental Samples by Gas Chromatography-Mass spectrometry and Liquid Chromatography with Fluorescence Detection. Talanta. 2009, 79, 900–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hospital, X.F.; Hierro, E.; Arnau, J.; Carballo, J.; Aguirre, J.S.; Gratacos-Cubarsi, M.; Fernandex, M. Effect of Nitrate and Nitrite on Listeria and Selected Spoilage Bacteria Inoculated in Dry-Cured Ham. Food. Res. Int. 2017, 101, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulmumeen, H.A.; Risikat, A.N.; Sururah, A.R. Food: its preservatives, additives, and applications. Int. J. Chem. Biochem. Sci. 2012, 1, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Chen, X, Zhu, L.; Liu, W.; Jiang, L. Programming an orthogonal self-assembling protein cascade based on reactive peptide-protein pairs for in vitro enzymatic trehalose production. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2022, 70, 4690-4700. [CrossRef]

- Larson, S.C.; Bergkvist, L.; Wolk, A. Processed Meat Consumption, Dietary Nitrosamines and Stomach Cancer Risk in a Cohort of Swedish Women. Int. J. Cancer. 2006, 119, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neth, M.R.; Love, J.S.; Horowitz, B.Z.; Shertz, M.D.; Sahni, R.; Daya, M.R. Fatal sodium nitrite poisoning: key considerations for prehospital providers. Prehosp. Emerg. Care. 2021, 25, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manassaram, D.M.; Backer, L.C.; Moll, D.M. A Review of Nitrates in Drinking Water: Maternal Exposure and Adverse Reproductive and Developmental Outcomes. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryan. N.S.; Fernandez, B.O.; Bauer, S.M.; Garcia-Saura, M.F.; Milson, A.B.; Rassaf, T.; Maloney, R.E.; Bharti, A.; Rodriguez, J.; Feelisch, M. Nitrite is a Signalling Molecule and Regulator of Gener Expression in Mammalian Tissues. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005, 1, 290-297.

- Ye, D.; Luo, L.; Ding, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, X. Synthesis of Potassium-Modified Graphene and its Application in Nitrite-Selective Sensing. Analyst. 2011, 136, 4563–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, P.; Wu, L.; Guan, W. Dietary nitrates, nitrites, and nitrosamines intake and the risk of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2015, 7, 9872–9895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balimandawa, M.; de Meester, C.; Leonard, A. The mutagenicity of nitrite in the Salmonella/microsome test system. Mutat. Res., Genet. Toxicol. 1994, 321, 7-11. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Hu, L.; Feng, X.; Wang, S. Nitrate and Nitrite in Health and Disease. Aging Dis. 2018, 9, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, S.E. Endogenous formation of N-nitroso compounds in relation to the intake of nitrate or nitrite. In: Health aspects of nitrate and its metabolites. 1995, 137-150.

- Fan, A.M.; Steinberg, V.E. Health implications of nitrate and nitrite in drinking water: an update on methemoglobinemia occurrence and reproductive and developmental toxicity. Regul Toxicol. Pharmacol. 1996, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puangpila, C.; Jakmunee, J.; Pencharee, S.; Pensrisirikul, W. Mobile-phone based colorimetric analysis for determining nitrite content in water. Environ. Chem. 2018, 15, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.H.; Mark, S.D.; Cantor, K.P.; Weisenburger, D.D.; Correa-Villasenor, A.; Zahm, S.H. Drinking Water Nitrate and the Risk of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Epidemiology. 1996, 7, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Nitrate and Nitrite in Drinking Water Background Document for Development of Drink Water. 2009, 2, 21.

- Bagheri, H.; Hajian, A.; Rezaei, M.; Shirzadmehr, A. Composite of Cu metal nanoparticles-multiwall carbon nanotubes-reduced graphene oxide as a novel and high-performance platform of the electrochemical sensor for simultaneous determination of nitrite and nitrate. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 324, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, J. Fabrication Non-Enzymatic Electrochemical Sensor Based on Methyl Red and Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite Modified Carbon Paste Electrode for Determination of Nitrite in Food Samples. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2023, 18, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussler, A.K.; Glanemann, M.; Schirmeier, A.; Liu, L.; Nussler, N.C. Fluorometric measurement of nitrite/nitrate by 2,3-diaminonaphthalene. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2223–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, T.; Arai, Y.; Takitani, S. Fluorometric determination of nitrite with 4-hydroxycoumarin. Anal. Chem. 1986, 58, 3132–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adarsh, N.; Shanmugasundaram, M.; Ramaiah, D. Efficient Reaction Based Colorimetric Probe for Sensitive Detection, Quantification, and on-Site Analysis of Nitrite Ions in Natural Water Resources. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 10008–10012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, L.; Ranjan, N. Highly Selective and Sensitive Detection of Nitrite Ion by an Unusual Nitration of a Fluorescent Benzimidazole. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 2745–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shou, Y.; Yan, D; Wei, M. ; A 2D quantum-dot based electrochemiluminescence film sensor towards reversible temperature-sensitive response and nitrite detection. J. Mater. Chem. 2015, 3, 10099–10106. [Google Scholar]

- Garside, C. A chemiluminescent technique for the determination of nanomolar concentrations of nitrate and nitrite in seawater. Mar. Chem. 1982, 11, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Fang, Y.; An, T.; Zhu, K.; Lu, J. Simultaneous spectrophotometric determination of nitrite and nitrate in water samples by flow-injection analysis. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2000, 76, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Standard. Water quality-determination of nitrites-molecular absorption spectrometric method. 1993.

- Fox, J.B. J. Anal. Biochem. 1979, 51, 1493.

- Guembe-Garcia, M.; Gonzalez-Ceballos, L.; Arnaiz, A.; Fernandez-Muino, M.A.; Sancho, M.T.; Oses, S.M.; Ibeas, S.; Rovira, J.; Melero, B.; Represa, C.; Garcia, J.M.; Vallejos, S. Easy Nitrite Analysis of Processed Meat with Colorimetric Polymer Sensors and a Smartphone App. ACS Appl. Matter. Interfaces. 2022, 14, 37051–37058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Yang, H.; Xu, S.; Li, X.; Wei, W.; Liu, X. “Olive-Structured” Nanocomposite Based on Environmental Nitrite Detection. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 17424–17431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Xu, J.; Lin, K.; Li, M.; Lu, M. Low-Cost Automatic Sensor for In Situ Colorimetric Detection of Phosphate and Nitrite in Agricultural Water. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 2541–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Wu, M.L.; Yan, B.Y.; Wang, H.F.; Kong, C. Integrated Digital Microfluidic Platform for Colorimetric Sensing of Nitrite. ACS Omega. 2020, 5, 11196–11201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, K.; Ohkura, K.; Terashima, N.; Kanaoka, Y. Photoreaction of 4-iodopyridine with Herteroaromatics. Heterocycles. 1986, 24, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barckholtz, C.; Barckholz, T.A.; Hadad, C.M. C-H and N-H Bond Dissociation Energies of Small Aromatic Hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, L.; Lees, A.J.; US 2020/0363382. 2020.

- Chen, H.; Wang, Q.; Tao, F.; A Novel Palladium-catalyzed Amination of aryl Halides with Amines using rac-P-Phos as the Ligand. Chinese Journal of Chemistry, 2009, 27, 1382-1386.

- Pai, G.; Asoke, P.C. Ligan-free Copper Nanoparticle promoted N-arylation of azoles with aryl and heteroaryl iodides, Tetrahedron Letters. 2014, 55, 941-944.

- Teo, Y.C.; Yong, F.F.; Sim,S. Ligand-free Cu2O-catalyzed cross coupling of nitrogen heterocycles with iodopyridines. Tetrahedron, 2013, 69, 7279-7284. [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.B.; Brimble, M.A.; Furkert, D.P. Reactivity of 2-Nitropyrrole Systems: Development of Improved Synthetic Approaches to Nitropyrrole Natural Products. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 12460–12470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, K.J.; Morrey, D.P. Nitropyrroles-I. Tetrahedron. 1966, 22, 57-62.

- Hills, B.P.; Takacs, S.F.; Belton, P.S. The Effects of Proteins on the Proton N.M.R. Transverse Relaxation Time of Water. Molec. Phys. 1989, 67, 919–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarrity, J.F.; Ogle, C.A. High-Field Proton NMR Study of the Aggregation and Complexation of N-Butyllithium in Tetrahydrofuran. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 1805–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazawa, N.; Sorensen, T.S. The Line-Shape Analysis of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Peaks Broadened by the Presence of a “hidden” Exchange Partner. Canadian Journal of Chemistry. 1978, 56, 2737–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbardelli, D.; Chidichiomo, G.; Longeri, M. Nuclear Relaxation of Partially Oriented Pyridine Determined by Line Width Analysis of 1H NMR Spectra. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1987, 135, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parteni, F.; Tassinari, F.; Libertini, E.; Lanzi, M.; Mucci, A. π-Stacking Signature in NMR Solution Spectra of Thiophene-Based Conjugated Polymers. ACS Omega. 2017, 2, 5775–5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjuroski, I.; Furrer, J.; Vermathen, M. Probing the Interactions of Porphyrins with Macromolecules using NMR Spectroscopy Techniques. Molec. 2021, 26, 1942–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E.; Bradley, R. Effects of “Ring Currents” on the NMR Spectra of Porphyrins. J. Chem. Phys. 1959, 31, 1413–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerlov, N.G.; Kullenber, B. The Tyndall Effect of Uniform Minerogenic Suspensions. Tellus. 1953, 5, 306–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Deng, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhuang, M.; Yuan, Y.; Nie, J.; Zhang, Y. Highly Sensitive Colorimetric Detection of a Variety of Analytes via the Tyndall Effect. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 15114–15122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, M. The Use of Light Scattering for Determining Particle Size and Molecular Weight and Shape. J. Chem. Educ. 1952, 29, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjanawarut, R.; Yuan, B.; Xiano, D.S. UV-Vis Spectroscopy and Dynamic Light Scattering Study of Gold Nanorods Aggregation. Nucleic Acid Therapeutics. 2013, 23, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duff, D.G.; Kirkwood, D.J.; Stevenson, D.M. The Behaviour of Dyes in Aqueous Solutions. I. The Influence of Chemical Structure on Dye Aggregation a Polarographic Study. J. Soc. Dyes. Colour. 1977, 93, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, A.; Sanz. F. Dye aggregation in solution: Study of C.I. direct red I. Dyes. Pigments. 1999, 40, 131-139.

- Martinez-Manez, R.; Sancenon, F. Fluorogenic and Chromogenic Chemosensors, and Reagents for Anions. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 4419–4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.: Aziz, H. Direct Observation of Exciton-Induced Molecular Aggregation in Organic Small-Molecule Electroluminescent Materials. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2019, 123, 16424-16429. [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Tang, B.Z. Fluorescent Sensors Based on Aggregation-Induced Emission: Recent Advances and Perspectives. ACS Sens. 2017, 2, 1382–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, D.J. Information Content in Organic Molecules: Aggregation States and Solvent Effects. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2005, 45, 1223–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

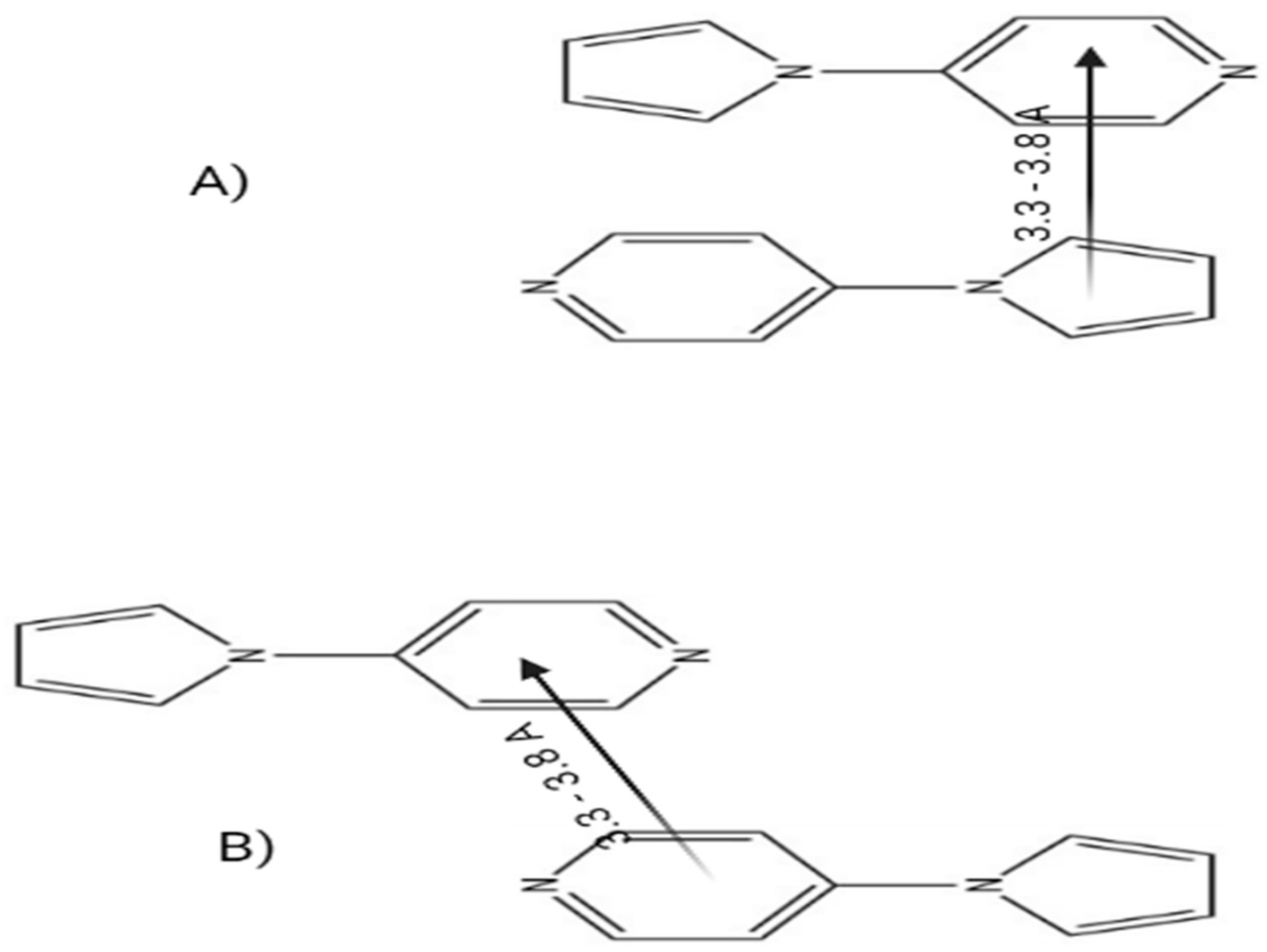

- Martinez, C.R.; Iverson, B.L. Rethinking the Term “Pi-Stacking”. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C.A.; Sanders, J.K. The Nature of Pi-Pi Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 5525–5534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiak, C. A Critical Account on π-π Stacking in Metal Complexes with Aromatic Nitrogen-Containing Ligands. J. Chem. Soc. 2000, 21, 3885–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concentration (M) | Absorbance at 463 nm | Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| 7.20 x 10-3 | 0.792 | 363 |

| 6.50 x 10-3 | 0.715 | 249 |

| 3.68 x 10-3 | 0.405 | 195 |

| 2.11 x 10-3 | 0.232 | 142 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).