1. Introduction

Simultaneous Localisation and Mapping (SLAM) serves as a fundamental requirement in several robotic tasks, and is widely used in areas such as autonomous driving, drones, augmented reality, and more. SLAM technology focuses on estimating a map of an uncharted environment and relying solely on data from the robot's own sensors to calculate the robot's position in that map. In recent years, visual SLAM has been the subject of a great deal of attention and research, especially dynamic visual SLAM research on the basis of RGB-D cameras.

Compared to other cameras, monocular cameras have many advantages, such as cost and size compared to other cameras, but there are several challenges, including issues related to size and observability of state initialisation. To address these challenges and enhance the robustness of visual SLAM systems, stereo or RGB-D cameras are often employed. However, conventional vision-based SLAM systems typically presume that the scene is not dynamic, and the presence of dynamic elements can lead to erroneous observations, diminishing the performance of various aspects of the SLAM system, such as robustness and accuracy. Although the RANSAC algorithm can handle anomalies in static or slightly dynamic environments, its effectiveness is limited when dynamic objects occupy the camera's field of view.

Recently, a number of researchers have used semantic information combined with geometric methods to address the visual SLAM challenge in dynamic environments. This approach combines techniques from target detection algorithms [

3], target tracking algorithms [

4] and semantic segmentation algorithms [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Semantic segmentation is good at providing fine dynamic object contour information, but its increased segmentation accuracy and algorithmic robustness also lead to higher time cost and poor real-time performance, as well as the problem of object segmentation boundary error. Target detection algorithms and target tracking algorithms solve the above problems to some extent. They can help recognize and track dynamic targets, but their object frames usually include a high proportion of static points, which can result in a reduction in the localization accuracy of the visual SLAM system if too many static points are included. To ameliorate this problem, researchers have begun to use geometric methods, such as geometric constraints and motion estimation, to help further increase the robustness and accuracy of SLAM systems. These methods enhance the identification capabilities of the system, reducing identification errors in static and dynamic areas to reduce misidentification of static points. By combining semantic and geometric methods, the performance of various aspects of the SLAM system in dynamic environments is improved, such as the positioning accuracy of the SLAM system, the segmentation accuracy of the semantic network and the robustness of the SLAM system, making them more suitable for a variety of application areas.

Regarding the above-mentioned issue, based on target detection and multi-view geometry, we propose TKG-SLAM, a high-performance and efficient visual SLAM system designed to support dynamic scenes. TKG-SLAM builds upon ORB-SLAM2 [

1] and leverages YOLOv5 for semantic information acquisition, compensates for missed detections using Kalman filtering and the Hungarian algorithm, and utilizes multi-view geometry to match static points. We've developed a two-stage approach with different conditions to handle various constraints, and static key points are incorporated for camera pose optimization.

The algorithm in this article conducts comprehensive performance testing on the TUM datasets, mainly including accuracy and running time. Our algorithm provides the most accurate localisation in certain dynamic scenarios and excels in real-time performance in comparison to state-of-the-art dynamic SLAM methods. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

Object detection based on YOLOv5, with compensation for missed detections using Kalman filtering and the Hungarian algorithm.

Utilizing the percentage of the image covered by detection boxes for multi-view geometry matching of feature points, ensuring the retention of static points within detection boxes for both precision and efficiency.

2. Related Works

The work situation is assumed to be stable and rigid in most current vision SLAM systems. However, in case of deployment in dynamic scenes, incorrect data correlation resulting from the static scene hypothesis can seriously affect the accuracies and robustness of the system. Since there are many dynamic objects in real life and they cannot be avoided, it is necessary to divide the extracted feature points into two categories: static features and dynamic features. The key to addressing this challenge lies in the detection and rejection of dynamic features. Previous work in dynamic vision SLAM can be broadly classified into three groups. The first is the very beginning, where only geometric information is used to deal with dynamic targets, then the second is the use of semantic information to deal with dynamic targets after the popularity of deep learning, and finally the third is the combination of geometric and semantic information to deal with dynamic targets together.

Since the dynamic feature points did not satisfy the constraints of the geometric approach, the visual SLAM system was only able to retain the static feature points. Kundu et al [

15] developed a remarkable system for monocular dynamic object recognition. This system draws inspiration from the principle of multi-view geometry and innovatively detects dynamic objects based on two geometric constraints [

16]. The core concept hinges on the utilization of the basis matrix, with a primary focus on aligning the epipolar lines associated with static feature points in the current video frame with those of the corresponding static feature points from the preceding video frame. In addition, certain approaches, such as [

17,

18,

19], opt for the direct method for motion detection. Direct method algorithms are faster and can use more image information. However, due to the necessary assumption that the grey scale cannot change, their robustness in complex environments may suffer.

The semantic method can more directly and accurately obtain the area where the dynamic object is located, because the deep neural network provides accurate object detection and object segmentation, which can be a target box (target detection network) or a dynamic target contour (instance segmentation network, semantic segmentation network). For example, Zhang et al. [

20] leveraged the target detection network YOLO [

21] as a foundation for obtaining the target frame that encompasses the location of the dynamic object. In their methodology, the identified region within this target frame was subsequently designated as a dynamic region, and then reject all the feature points within the region. However, the algorithm works robustly when the percentage of target frames in the video frames is small, but when the percentage is too large, too many static feature points in the frame will be eliminated, resulting in too few feature points in the whole video frame and erroneous construction of the map, which leads to errors. RDS-SLAM [

7] enhances its dynamic object representation by leveraging the capabilities of a semantic segmentation network to extract the outline of the dynamic object in key frames. This strategic use of semantic segmentation addresses certain limitations associated with the target object frame, but its detected outline of the dynamic object is not as good as that of the target frame, and it can be used to detect the dynamic object. However, the effectiveness of dynamic object contour detection in methods such as RDS-SLAM is highly dependent on the performance and quality of the underlying semantic segmentation network. This leads to potential problem, and it is difficult to optimise the accuracy and real-time performance at the same time.

Recent work has begun to investigate combining geometric and semantic approaches together to remove dynamic feature points. For example, DynaSLAM [

6] obtains dynamic target contours based on the instance segmentation network Mask R-CNN [

24], and then combine it with a multi-view geometric approach to cull dynamic feature points, DS-SLAM [

5] obtain dynamic target contours based on the semantic segmentation network SegNet [

25] in a separate thread, and then combine it with the optical flow method in the geometric approach for dynamic. YOLO-SLAM [

22] obtains the target frame of a dynamic object based on the target detection network YOLO, and then combine the depth-RANSAC method with the geometric method to remove the feature points inside the dynamic target frame. In a similar vein, Chang et al. [

23] obtain the dynamic object contour by using the instance segmentation network YOLACT, and then remove the feature points within the contour. And then filter the dynamic points by combining geometric constraints. All of these methods combine semantic and geometric methods, and compared with applying only one of them, these methods are more effective in removing dynamic feature points, and the accuracy and robustness of the SLAM system is better.

Of the above methods, in general, the geometric methods have an advantage in terms of speed, the semantic methods have an advantage in terms of positioning accuracy, and the combined semantic-geometric methods are more accurate, but also more time-consuming. More specifically, they also have the following drawbacks:

- 1)

Unable to effectively handle extreme situations. When most of the feature points are removed based on the semantic information provided by the deep network, the remaining feature points are difficult to be used by the SLAM system to build a map for localisation.

- 2)

Weak real-time performance. Because of factors such as the high complexity of deep learning networks and the lack of emphasis on real-time in the construction of SLAM systems, their computational complexity is excessively high. In order to solve the above problems, we provide an effective algorithm that combines geometry and semantics and that takes into account both the accuracy and the real-time performance.

3. System Description

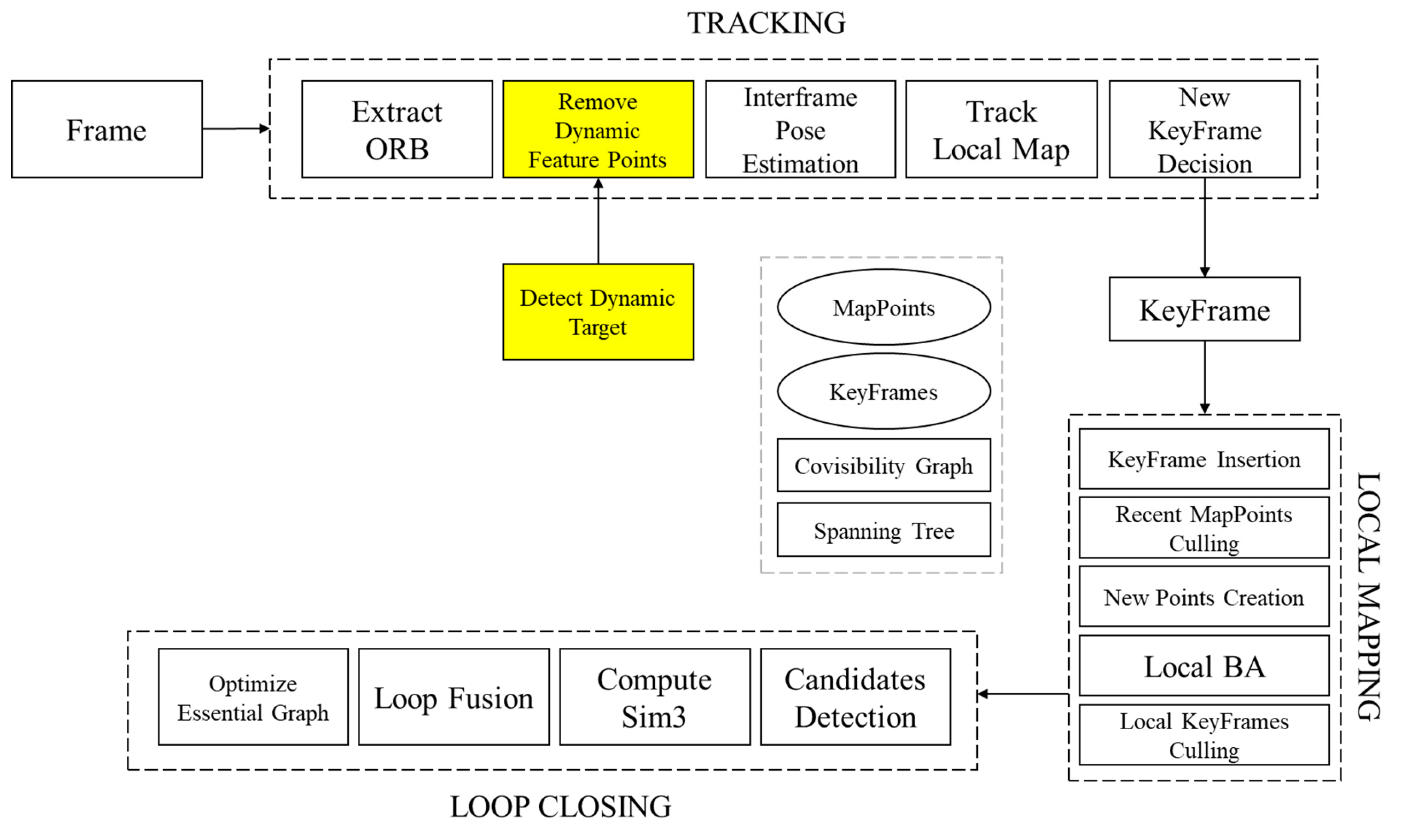

Figure 1 illustrates the comprehensive framework of the proposed system. The highlighted yellow box represents the dynamic point processing module. In this module, video frames traverse the dynamic target detection component, responsible for identifying a priori dynamic entities, such as individuals or vehicles. The dynamic target detection module comprises the YOLOv5 target detection network, a Kalman filter, and a multi-view geometry constraint module. This process can be divided into two stages: firstly, it detects dynamic objects within the area, allowing for the determination of the potential rectangular motion regions associated with prior dynamic objects. In the second stage, the multi-view geometry module identifies and retains static points within the rectangular area, ultimately eliminating dynamic objects from the scene.

3.1. Dynamic target detection

Given the presence of dynamic elements such as people, animals, and vehicles in the real scene, YOLOv5 is employed to acquire prior information about these dynamic objects. The input of YOLOv5 is the RGB raw image. This article sets the possible dynamic set of objects as

, where:

Consider the objects in

as a priori dynamic objects. If additional a priori dynamic objects are required based on the scenario, the network trained on MS COCO [

14] can be fine-tuned using new training data.

According to , the algorithm is improved and fine-tuned using the loss function . In the formula, represents categories, represents the weight of category , represents the probability that the real label is category , and represents the prediction probability of the model. Adjust the weights of object categories within to give higher weights to the categories of interest, thereby promoting the model to better detect these objects.

YOLOv5 is employed for handling dynamic objects, serving as a high-speed, real-time object detection network capable of identifying the regions where potential prior dynamic objects are situated. TR-SLAM [

8] and DS-SLAM [

5] utilise the slight semantic segmentation network SegNet, and YOLOv5 offers lower computational complexity and superior real-time performance compared to them. In addition, Dyna-SLAM [

6] utilises Mask-RCNN, YOLOv5 processes one frame in a fraction of the time required by Mask-RCNN under the same hardware conditions compared to Dyna-SLAM. Consequently, it excels in terms of timeliness. This module detects prior dynamic objects within the scene and considers all feature points as potential dynamic points.

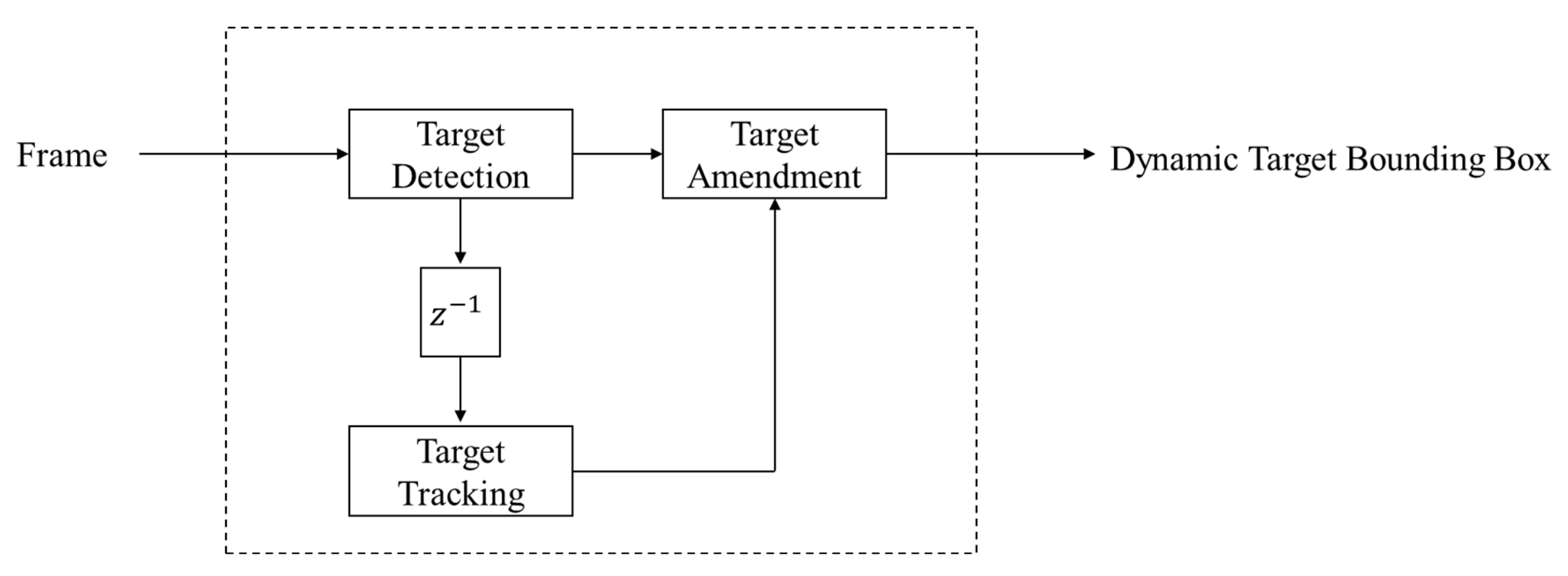

3.2. Missing detection supplement

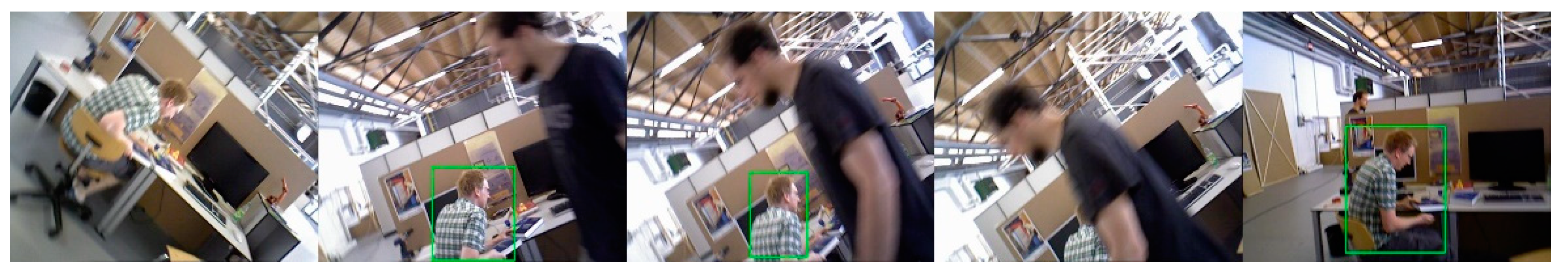

In practice, SLAM carts often face situations of fast turns and uneven road surfaces, which easily lead to blurred images captured by the camera. Due to the blurred images, YOLOv5 is prone to miss detection when detecting dynamic objects, which in turn affects the feature points extraction and feature points matching of the SLAM system on dynamic objects, thus reducing the quality and accuracy of SLAM map building. As shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

In this paper, the Kalman filter is used as a complement to missed detection to solve this problem. This method improves the accuracy and stability of detection by checking the complementary missed objects. Based on the Kalman filter, we are able to effectively deal with the leakage detection problem of YOLO, which can provide more accurate and reliable detection results, thus improving the quality and accuracy of the SLAM system's map building. The system model used in Kalman filter is as follows.

In the above equation (subscript k denotes k moment, k-1 means k-1 moment), is the state vector of the dynamic object, is the observation vector of the dynamic object, is the state transfer matrix from moments to moments, and is the observation matrix. is the noise vector of the system, and is the noise vector of the observation. are generally white noise sequence obeying zero-mean Gaussian distribution, and their covariance matrices are , respectively. assume that are both noise vectors obeying zero-mean Gaussian distribution.

In this paper, the state vector

of a priori dynamic objects is defined as:

where

are used to locate the position of the bounding box in the video frame, that is, the coordinates of the top left-hand corner.

refers to the area of the bounding box, and

is the aspect ratio of the bounding box.

are the velocities of the target frame in the

direction, and

is the rate of change of the area of the target frame.

Under normal circumstances, the time between the two frames before and after the camera sensor captures the image is very short, the dynamic object can be assumed to move at a steady speed between frames, and assuming that the time interval between each frame is

, the state transfer matrix and observation matrix can be defined as follows, respectively:

In this paper, we set to 1 frame.

We can correct the detection results of missed dynamic regions based on unmatched predicted boxes. The logic for identifying misses is as follows: if the number of dynamic objects detected in the previous video frame is more than the number detected in the current video frame, we check if the number of objects being tracked by the Kalman filter is greater than the number of detections in the current frame. If it is greater, this indicates a missed detection, and we use the tracked results to rectify the detection results. If the number of tracked objects and detected objects in the current frame are equal, we maintain the current detection results as the output. The overall workflow of the dynamic region's missed detection method is illustrated in

Figure 4.

The detection results of the corrected missed dynamic region are shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

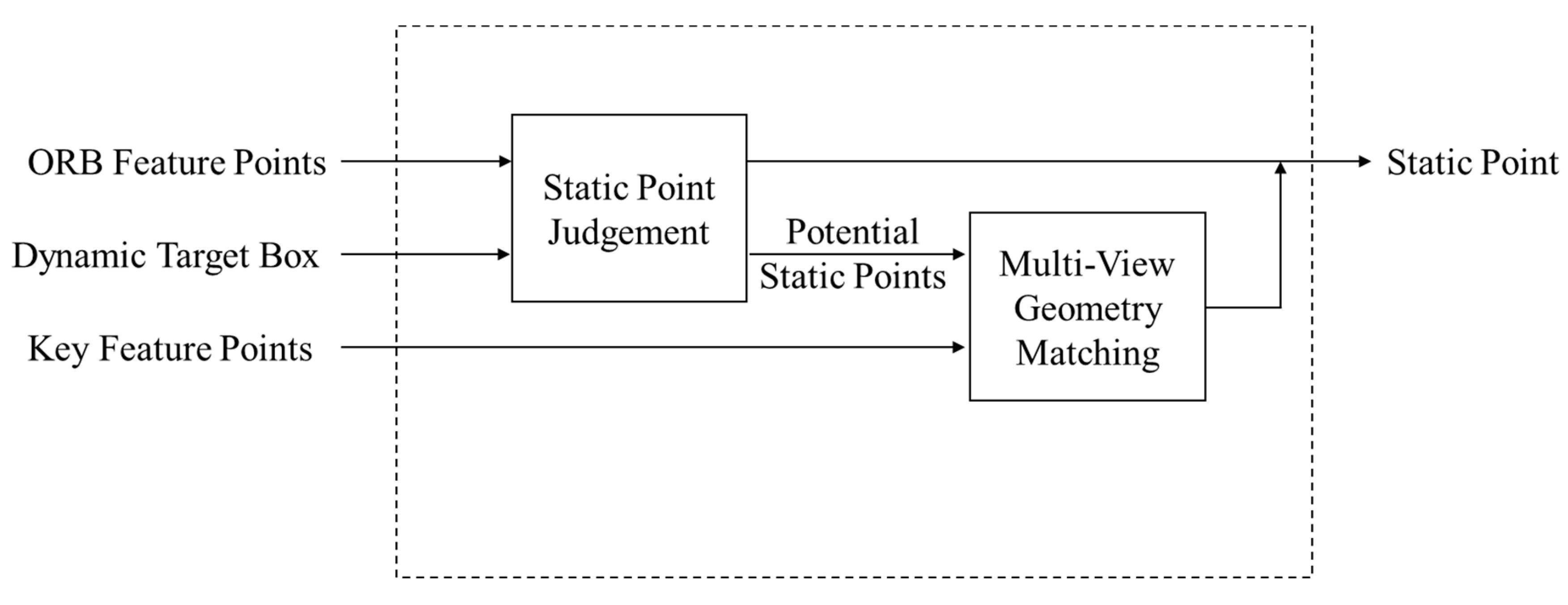

3.3. Dynamic feature points removal

While the problem of detection missing can be resolved by applying a Kalman filter to correct the missing detection region, in cases where Kalman correction is applied to dynamic regions with missing detections, some prediction frames can cover up to 80% or even more of the image frame, as shown in

Figure 6. Removing the dynamic feature points from these frames would significantly reduce the amount of feature points, which in turn would affect the accuracy of the image reconstruction. To address this issue, multi-view geometry is used to match moving feature points, as depicted in

Figure 7.

This paper does not impose multi-view geometry constraints on all frames to improve the efficiency of the system. Let the input image area size be

, and the area sum of all target detection frames in the figure be

, then we define the ratio of the bounding box to the video frame as:

Set a threshold with . When , all of the feature points within the region of the bounding box can be removed directly. Instead, only the feature points present within the static area will be utilized for feature matching and map building, in which case it is considered to have enough feature points for feature point matching. When the proportion of the bounding box in the image is , the inclusion of multi-view geometry constraint relationships is critical to better differentiate between static and dynamic feature points. In this way, we can deal with feature points according to different scenarios and guarantee the stability of the system and the accuracy of map building while ensuring real-time performance.

The basic algorithmic flow of dynamic point rejection on the basis of multi-view geometry is as follows:

- a)

Find the 3 most similar reference frames for the current frame.

Where,

is the queue for sorting the distance between the current frame and the key frame, noted as the reference frame queue,

is obtained by normalizing the difference between the translation distances of the two frames, and

is obtained by normalizing the difference between the Euler angle distances of the two frames. in this paper, the size of the reference frame queue is set to 3.

- b)

Feature points with depth in the reference frame are selected, and 3D points under the reference frame are computed and then transformed to the world coordinate system.

- c)

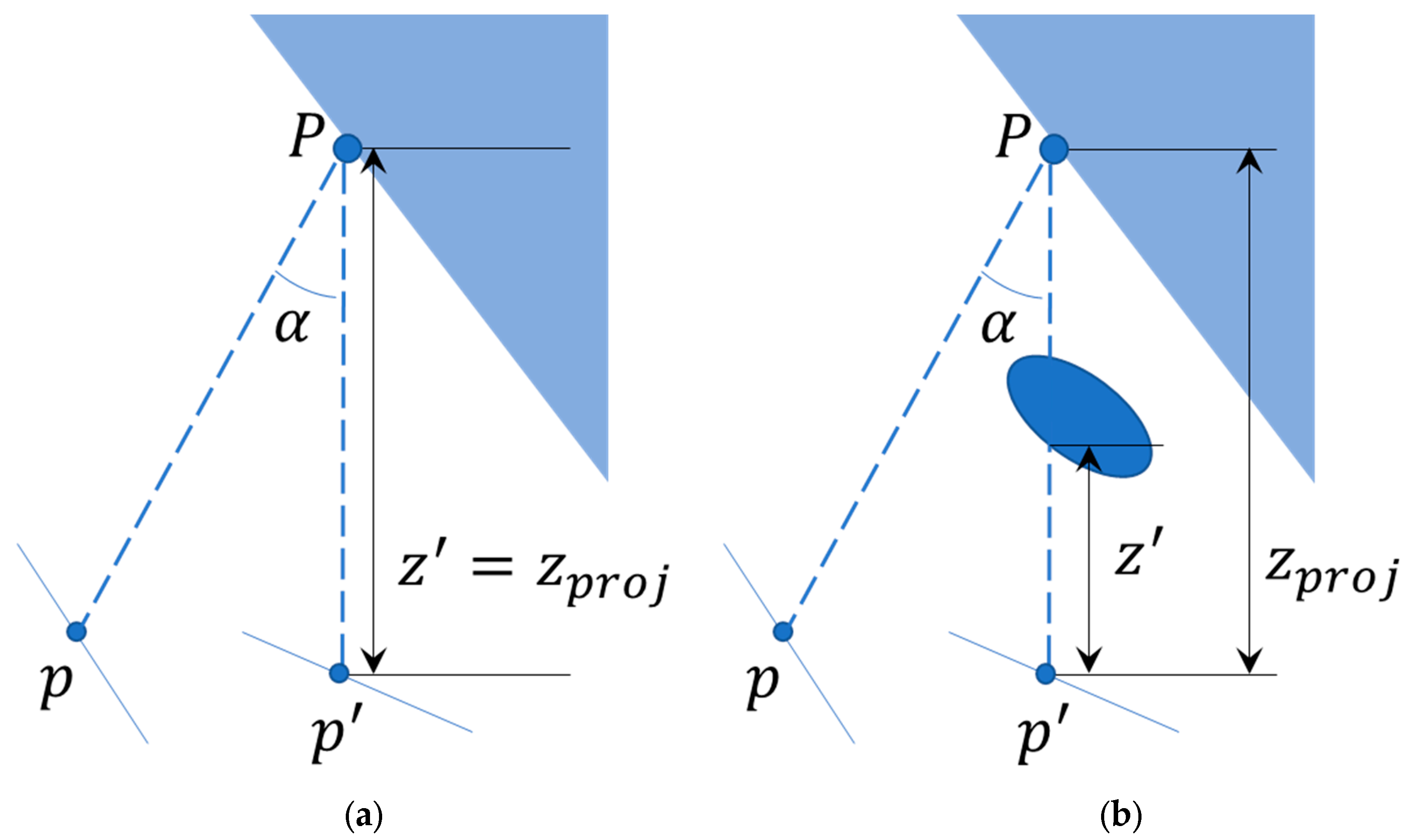

Retain the points where the angle between the current frame-to-map point vector and the reference frame-to-map point vector is less than 30°, as shown in

Figure 8.

is the feature point of the reference frame,

is the feature point of the current frame, and

is the map point with the angle

. When

, then

may be a dynamic point, and then it will be ignored.

- d)

The remaining map points are back-projected under the current frame coordinate system, keeping the map points with depth value .

- e)

The remaining map points are then transformed to the current pixel coordinate system, and each point within the small region (patch) is traversed in the form of a small region centred on the remaining key point of the current frame. For each pixel point, determine whether its depth value is greater than zero and less than the depth value of the projection point of the reference frame at the current key point (centre of the region). If these conditions are met, it is considered as a potential dynamic object point, as it indicates that this feature point is probably hidden by a moving object, resulting in a lower smaller value.

- f)

Calculate the depth difference of these potential dynamic points. If the set threshold is less than the depth difference, proceed to calculate the variance and average of the depth in the surrounding area. If the threshold is less than the depth difference, it implies complex occlusion relationships within the region, leading to its classification as a static point. If the depth difference is greater than the threshold, it implies complex occlusion relationships within the region, leading to its classification as a static point. Points with a depth difference less than the threshold are considered dynamic. As illustrated in

Figure 8(b), the key points p within the reference frame KF are mapped onto the current frame CF, corresponding to

.The projected depth value for

is denoted as

. At this point, the depth value for

in the current frame is

, and because it is occluded so

. Therefore, point

is regarded as a dynamic feature point.

4. Experimental Results

We use the TUM RGB-D datasets to test the performance of the algorithm. We select the dynamic scene part, which includes eight datasets. These are four low motion (abbreviated as "s" in the subsequent tables) and four high motion (abbreviated as "w" in the subsequent tables) sequences. The RGB-D camera motion consists of four modes: static, xyz, halfsphere and rpy. Two metrics were used to evaluate performance, namely absolute trajectory error (ATE) and relative position error (RPE). ATE is used to know the global performance of the algorithm. RPE helps to understand the performance of the algorithm in different aspects, including position and orientation accuracy. Root mean square error (RMSE) and standard deviation (SD) statistics are used to represent the robustness and stability of the system [

13].

Our approach was first compared with a number of state-of-the-art visual SLAM methods. Next, to verify the performance of each module of the algorithm, ablation experiments were set up for each module. Finally, the real-time performance is compared with the visual SLAM algorithm with the best real-time performance. All of the experiments were carried out on a computer that was equipped with an Intel i5 processor and 16 GB of RAM. The initial value of in the experiments were set to 0.01 and the initial value of were set to 0.1.

4.1. Comparison with the state-of-the-art methods

We compare our method with state-of-the-art dynamic SLAM methods, including Dyna-SLAM [

6], TRS [

8], CFP-SLAM [

4], AIV-SLAM [

11] and Amos-SLAM [

9]. These algorithms and ours are based on the ORB-SLAM2 system, which improves the system's poor dynamic scene effects. In this article, the result with the highest accuracy is in bold and the result with the second accuracy is underlined. The data of each algorithm in the table of this article are taken from the literature, * indicates that the data are not given in the original literature. Based on the experimental results, it can be concluded that our SLAM algorithm has better performance in both low-dynamic and high-dynamic environments. In static sequences, where there are few missed detections, the role of the Kalman filter is very small, so the effect of our algorithm is not optimal. In the rpy sequences, firstly, the polar constraints are not applied and, Second, the high variation in the camera angle results in poor feature matching, so that our algorithm performs a little worse. As can be seen in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

4.2. Ablation experiments

To demonstrate the effectiveness of each module within our SLAM system, a range of ablation experiments were conducted within high-dynamic scenes.

Table 3 illustrates the experimental results. The experimental findings are presented in

Table 3, with TKG-SLAM representing our algorithm, TK-SLAM indicating the version without multi-view geometry, TG-SLAM excluding the missed detection compensation, and T-SLAM treats all feature points in the bounding box as dynamic feature points and deletes them directly.

The experimental results indicate that in high-dynamic scenes, TK-SLAM often loses tracking because it removes too many feature points, and in some cases, it even results in tracking failure within w/half. TG-SLAM, on the other hand, cannot perform multi-view geometry algorithms when object detection is lost due to a lack of missed detection compensation, leading to tracking loss. T-SLAM directly eliminates a large number of feature points, causing certain difficulties in system initialization, and the feature points in some video frames are insufficiently matched, resulting in a decrease in accuracy.

4.3. Execution Time

As real-time performance is emphasised in practical applications, it is very important for the SLAM system. In order to eliminate the difference in runtime due to different hardware platforms, we take the execution time of the ORB-SLAM2 algorithm on the individual hardware platform as the unit for algorithm runtime comparison. We measured the mean relative runtime of each module, as illustrated in

Table 4. Where ORIGINAL is the runtime of ORB-SLAM2, which is set to T. KALMAN is the leakage compensation and data association module of the box, YOLO is the target detection thread based on YOLOv5, which runs in parallel with ORB feature extraction, and GEOME is the multi-view geometry algorithm module.

Among the algorithms compared in this paper, CFP-SLAM is the one with the highest real time performance. As indicated in Table 5, when operating under the same hardware conditions, our algorithm exhibits a time complexity of 3.86 T, whereas CFP-SLAM has a time complexity of 6.24 T. Clearly, our algorithm demonstrates superior real-time performance.

5. Conclusions

A visual SLAM algorithm integrating YOLOv5, Kalman filter and multi-view geometry is proposed in this paper. It mainly addresses the problem of unstable operation of the SLAM system in dynamic scenes. Following compensation for missing detections, video frames with an excessive proportion of detection frames are constrained using multi-view geometry. Extensive experiments demonstrate that our algorithm attains commendable localization accuracy across a broad range of low and high dynamic scenes, achieving optimal accuracy in specific scenarios. Furthermore, it exhibits reduced computational requirements and enhanced real-time performance compared to other algorithms operating on the same hardware platform. Looking forward, our plan involves applying this algorithm to embedded cars to further validate its real-time performance and accuracy in practical applications.

References

- Mur‐Artal R, Tardós J D. Orb‐slam2: An open‐source slam system for monocular, stereo, and rgb‐d

cameras[J]. IEEE transactions on robotics, 2017, 33(5): 1255‐1262.Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Title of the

chapter. In Book Title, 2nd ed.; Editor 1, A., Editor 2, B., Eds.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2007;

Volume 3, pp. 154–196.

- Saputra M R U, Markham A, Trigoni N. Visual SLAM and structure from motion in dynamic environments: A survey[J]. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 2018, 51(2): 1-36.

- L. Xiao, J. Wang, X. Qiu, Z. Rong, and X. Zou, “Dynamic‐slam: Semantic monocular visual localization and

mapping based on deep learning in dynamic environment,” Robotics and Autonomous Systems, vol. 117,

pp. 1–16, 2019.

- Hu X, Zhang Y, Cao Z, et al. CFP-SLAM: A Real-time Visual SLAM Based on Coarse-to-Fine Probability in Dynamic Environments[C]//2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, 2022: 4399-4406.

- Yu C, Liu Z, Liu X J, et al. DS-SLAM: A semantic visual SLAM towards dynamic environments[C]//2018 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems (IROS). IEEE, 2018: 1168-1174.

- Bescos B, Fácil J M, Civera J, et al. DynaSLAM: Tracking, mapping, and inpainting in dynamic scenes[J]. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 2018, 3(4): 4076-4083.

- Liu Y, Miura J. RDS-SLAM: Real-time dynamic SLAM using semantic segmentation methods[J]. Ieee Access, 2021, 9: 23772-23785.

- Ji T, Wang C, Xie L. Towards real-time semantic RGB-D SLAM in dynamic environments[C]//2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2021: 11175-11181.

- Zhuang Y, Jia P, Liu Z, et al. Amos-SLAM: An Anti-Dynamics Two-stage SLAM Approach[J]. arxiv preprint arxiv:2302.11747, 2023.

- Li A, Wang J, Xu M, et al. DP-SLAM: A visual SLAM with moving probability towards dynamic environments[J]. Information Sciences, 2021, 556: 128-142.

- Ni J, Wang L, Wang X, et al. An Improved Visual SLAM Based on Map Point Reliability under Dynamic Environments[J]. Applied Sciences, 2023, 13(4): 2712.

- Liu G, Zeng W, Feng B, et al. DMS-SLAM: A general visual SLAM system for dynamic scenes with multiple sensors[J]. Sensors, 2019, 19(17): 3714.

- Sturm J, Engelhard N, Endres F, et al. A benchmark for the evaluation of RGB-D SLAM systems[C]//2012 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems. IEEE, 2012: 573-580.

- Lin T Y, Maire M, Belongie S, et al. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context[C]//Computer Vision–ECCV

2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6‐12, 2014, Proceedings, Part V 13.

Springer International Publishing, 2014: 740‐755.

- Kundu A, Krishna K M, Sivaswamy J. Moving object detection by multi-view geometric techniques from a single camera mounted robot[C]//2009 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. IEEE, 2009: 4306-4312.

- Hartley R, Zisserman A. Multiple view geometry in computer vision[M]. Cambridge university press, 2003.

- Piaggio M, Fornaro R, Piombo A, et al. An optical-flow person following behaviour[C]//Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE International Symposium on Intelligent Control (ISIC) held jointly with IEEE International Symposium on Computational Intelligence in Robotics and Automation (CIRA) Intell. IEEE, 1998: 301-306.

- Nguyen D, Hughes C, Horgan J. Optical flow-based moving-static separation in driving assistance systems[C]//2015 IEEE 18th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems. IEEE, 2015: 1644-1651.

- Zhang T, Zhang H, Li Y, et al. Flowfusion: Dynamic dense rgb-d slam based on optical flow[C]//2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2020: 7322-7328.

- Zhang L, Wei L, Shen P, et al. Semantic SLAM based on object detection and improved octomap[J]. IEEE Access, 2018, 6: 75545-75559.

- Redmon J, Farhadi A. YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2017: 7263-7271.

- Wu W, Guo L, Gao H, et al. YOLO-SLAM: A semantic SLAM system towards dynamic environment with geometric constraint[J]. Neural Computing and Applications, 2022: 1-16.

- Chang J, Dong N, Li D. A real-time dynamic object segmentation framework for SLAM system in dynamic scenes[J]. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 2021, 70: 1-9.

- He K, Gkioxari G, Dollár P, et al. Mask r-cnn[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision. 2017: 2961-2969.

- Badrinarayanan V, Kendall A, Cipolla R. Segnet: A deep convolutional encoder‐decoder architecture for

image segmentation[J]. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, 2017, 39(12): 2481-2495.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).