Submitted:

05 December 2023

Posted:

06 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Immediate vs. Long-term Effects

Thinning Intensity:

Time Elapsed from Thinning:

1.2. Magnitude of Change

Thinning Intensity:

Time Elapsed from Thinning:

1.3. Direct vs. Indirect Effects

Thinning Intensity:

Time Elapsed from Thinning:

1.4. Reversibility

2. Materials and Methods

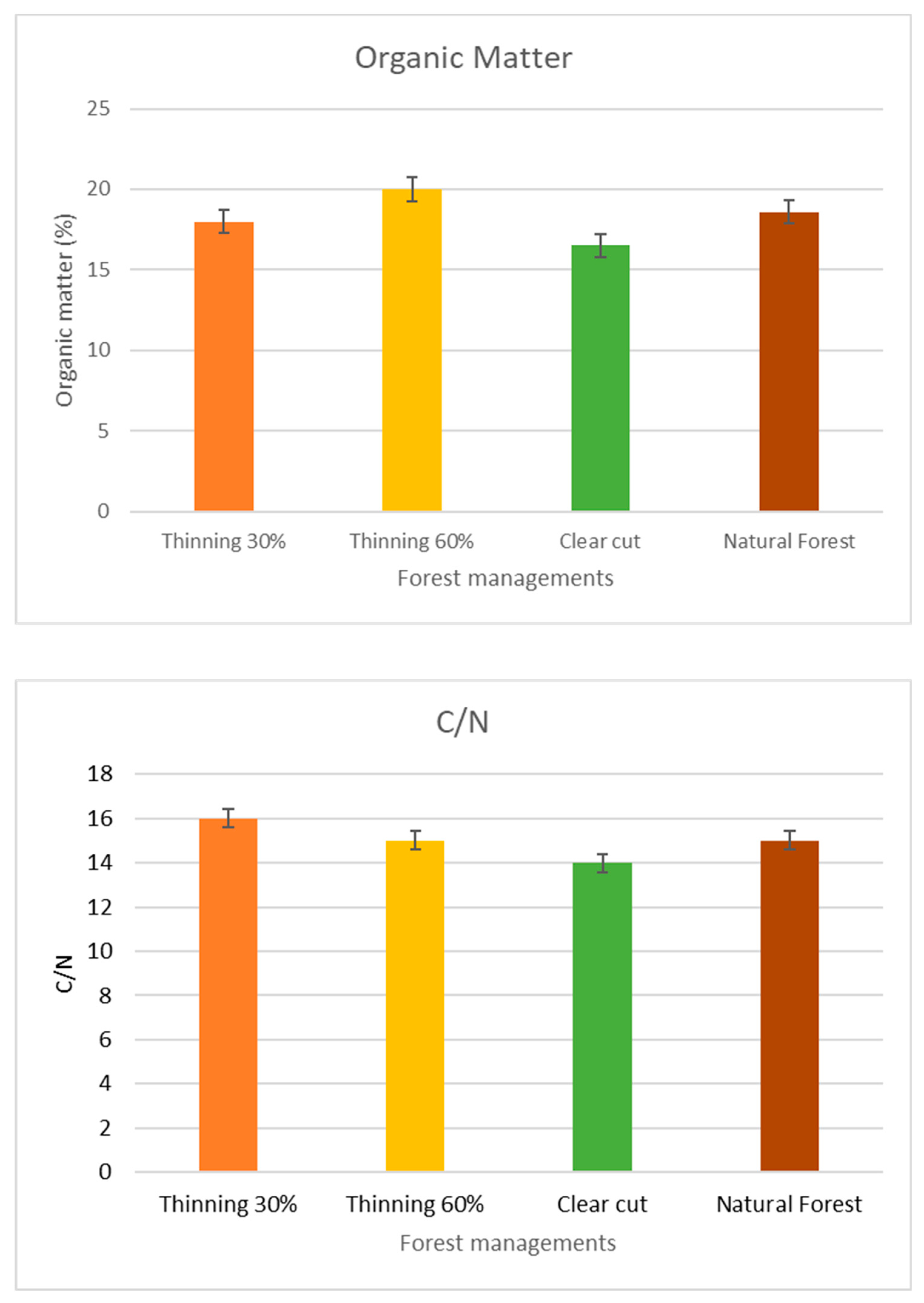

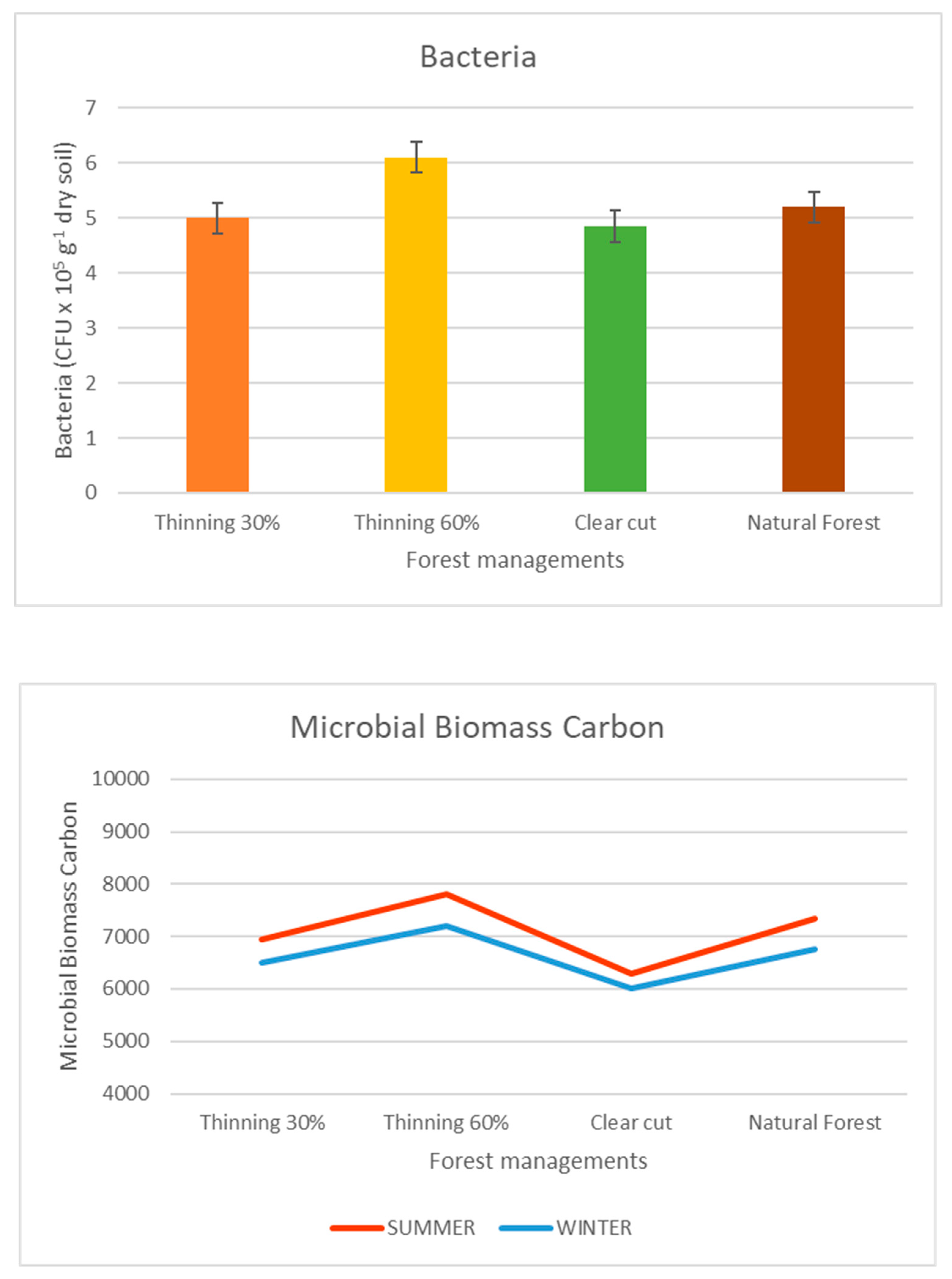

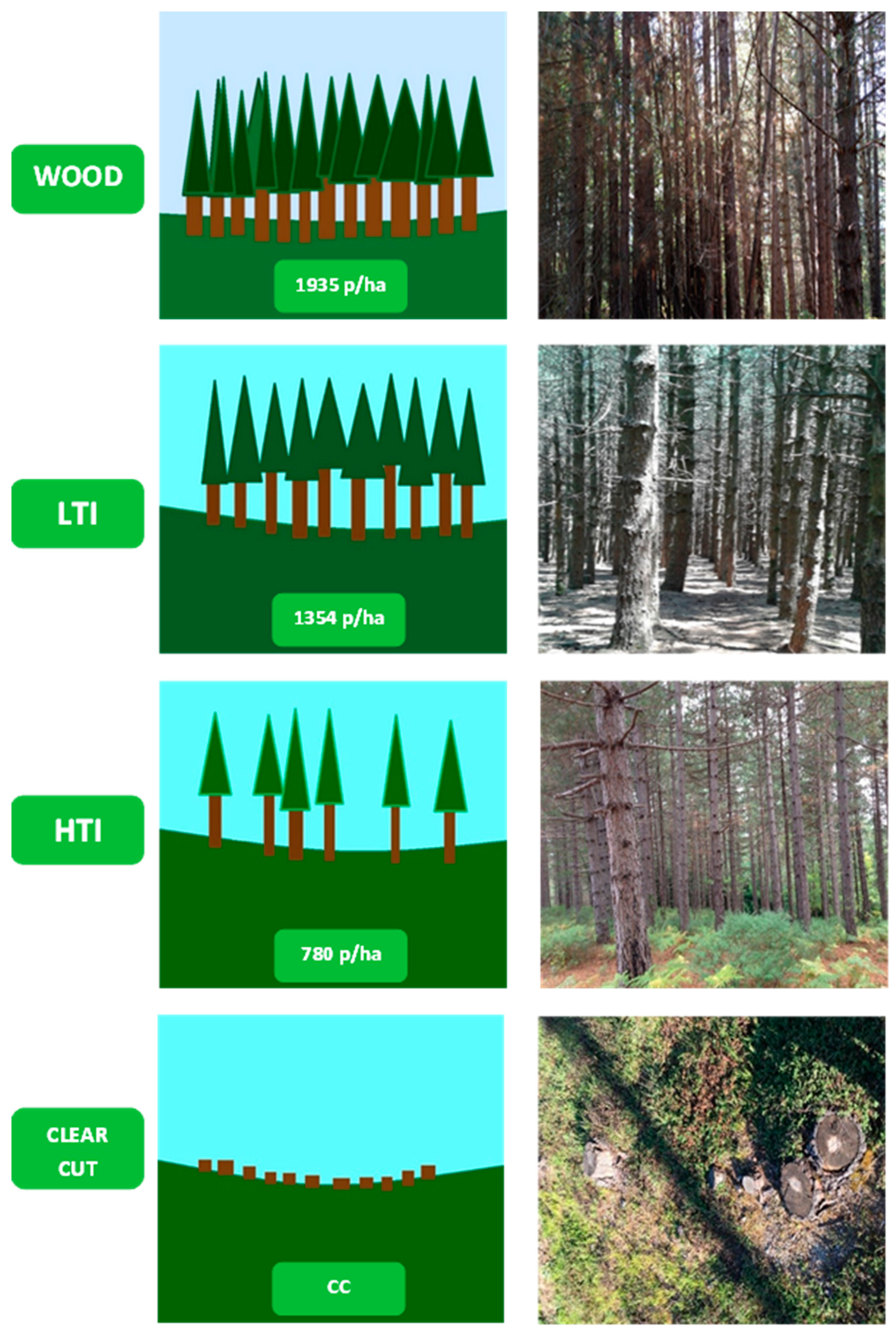

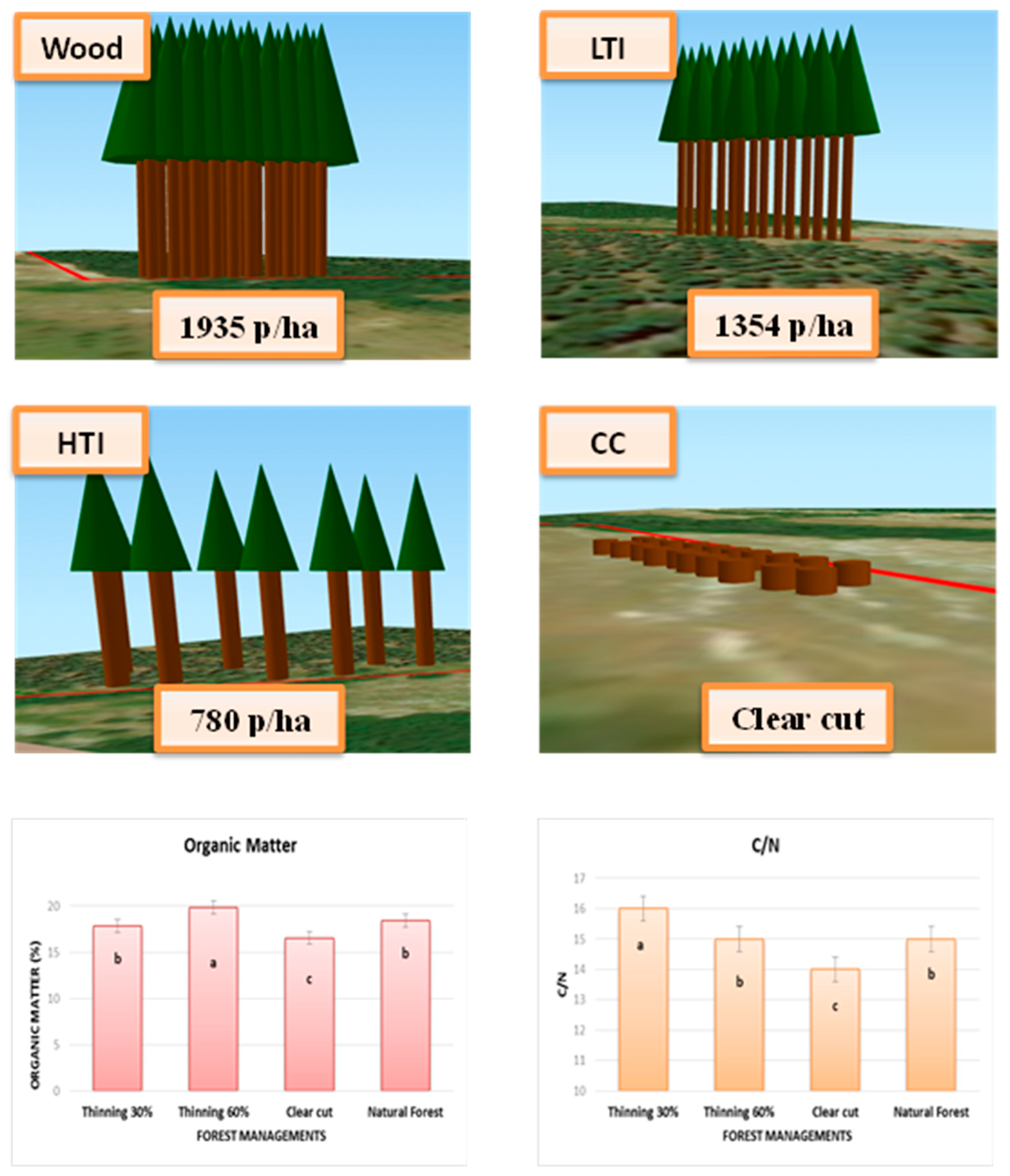

2.1. Thinning intensity effects on soil chemical and biochemical properties

2.2. Thinning time effects on soil chemical and biochemical properties

| Forest type | Location | Thinning intensity % BA |

Years after thinning | OM | MBC | Enzyme activity | References |

| Larix principis-rupprechtii | Northern China | 15 35 50 |

3 | ns + + |

ns + + |

+ + + |

Wu et al. 2019 |

| Pinus sylvestris | Central Spain | 15-20 21-35 |

2 | ns | ns | ns | Bravo-Oviedo et al. 2015 |

| Quercus ilex | Valencia, Spain | 41 | 4-7 |

ns | ns | Lull et al. 2020 | |

| Cunninghamia lanceolata | Eastern China | 21 36 |

2 | + + |

Cheng et al. 2018 | ||

| Cunninghamia lanceolata | northern China | 15 20 33 |

15 | Ns Ns ns |

Cheng et al. 2017 | ||

| Pinus halepensis | Eastern Spain | 36 54 84 |

13 | - - - |

Molina et al. 2022 | ||

|

Quercus variabilis, Quercus mongolica, Larix kaempferi |

South Korea | 5-23 30-44 |

6 | + + |

+ + |

ns ns |

Kim et al. 2019 |

| Pinus densiflora | South Korea | 15 30 |

7 | + + |

+ + |

ns ns |

Kim et al. 2018 |

| Larix kaempferi | South Korea | 20 30 |

3 | + + |

ns ns |

Kim et al. 2016 | |

| Pinus tabulaeformis | northern China | 20 40 60 |

9 | ns ns ns |

+ - |

Yang et al. 2022 | |

|

Larix principis-rupprechtii, Pinus tabulaeformis, Betula platyphylla, Quercus liaotungensis |

North China | 15 30 50 |

7 | + + + |

ns + - |

Ma et al. 2022 | |

|

Pinus rigida, Larix leptolepis |

central Korea | 50 | 2 | + | Hwang and Son 2006 | ||

| Pinus nigra | Turkey | 30 | 2 | ns | + | Bolat 2014 | |

| Pinus massoniana | China | 15 70 |

3 | ns - |

+ + |

- - |

Shen et al 2018 |

3. Discussion and conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weiskittel A.R.; Hann D.W.; Kershaw J.A. Jr.; Vanclay J.K. Forest growth and yield modeling. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester 2011 p. 425.

- Jandl R.; Bauhus J.; Bolte A.; Schindlbacher A.; Schüler S. Effect of climate-adapted forest management on carbon pools and greenhouse gas emissions. Curr Forestry Rep 2015 1:1-7. [CrossRef]

- Menyailo O.V.; Sobachkin R.S.; Makarov M.I.; Cheng C-H. Tree species and stand density: The effects on soil organic matter contents, decomposability and susceptibility to microbial priming. Forests 2022 13 (2): 284. [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson J.; Nilsson S.G.; Franc A.; Menozzi P. Biodiversity, disturbances, ecosystem function and management of European forests. For Ecol Manage 2000 132 (1): 39-50.

- LAL, R. Soil carbon sequestration in Latin America. In: Carbon sequestration in soils of Latin America. CRC Press, 2006 p. 77-92.

- Jandl R.; Lindner M.; Vesterdal L.; Bauwens B.; Baritz R.; Hagedorn F.; Johnson D.W.; Minkkinen K.; Byrne K.A. How strongly can forest management influence soil carbon sequestration? Geoderma 2007 137(3-4): 253-268.

- Ashagrie Y.; Zech W.; Guggenberger G.; Miano T. Soil aggregation, and total and particulate organic matter following conversion of native forests to continuous cultivation in Ethiopia. Soil Till Res 2007 94 (1):101-108.

- Kim S.; Li G.; Han S.H.; Kim C.; Lee S.T.; Son Y. Microbial biomass and enzymatic responses to temperate oak and larch forest thinning: Influential factors for the site-specific changes. Sci Total Environ 2019 651: 2068-2079.

- Lukac M. Soil biodiversity and environmental change in European forests. Cent Eur For J 2017 63 (2-3): 59-65. [CrossRef]

- Resck D.V.S.; Ferreira E.A.B.; Figueiredo C.C.; Zinn Y.L Dinâmica da matéria orgânica no Cerrado. In: Santos G.A.; Silva L.S.; Canellas L.P.;Camargo F.O. (eds) Fundamentos da matéria organica do solo: Ecossistemas tropicais e subtropicais Metrópole, Porto Alegre 2008 pp 359-417.

- Masyagina O.V.; Hirano T.; Ji D.H.; Choi D.S.; Qu L.; Fujinuma Y.; Sasa K.; Matsuura Y.; Prokushkin S.G.; Koike T. Effect of spatial variation of soil respiration rates following disturbance by timber harvesting in a larch plantation in northern Japan Forest Sci Technol 2006 2 (2): 80-91.

- Chen X-L.; Wang D.; Chen X.; Wang J.; Diao J-J; Zhang J-Y; Guan Q-W. Soil microbial functional diversity and biomass as affected by different thinning intensities in a Chinese fir plantation Appl Soil Ecol 2015 92: 35-44.

- Trentini C.P.; Campanello P.I.; Villagra M.; Ritter L.; Ares A.; Goldstein G. Thinning of loblolly pine plantations in subtropical Argentina: Impact on microclimate and understory vegetation. For Ecol Manage 2017 384: 236-247. [CrossRef]

- Ryu S.R.; Concilio A.; Chen J.; North M.; Ma S. Prescribed burning and mechanical thinning effects on belowground conditions and soil respiration in a mixed-conifer forest, California. For Ecol Manage 2009 257 (4): 1324-1332.

- Ma Y.; Cheng X.; Kang F.; Han H. Effects of thinning on soil aggregation, organic carbon and labile carbon component distribution in Larix principis-rupprechtii plantations in North China. Ecol Ind 2022 139: 108873. [CrossRef]

- Bolat I. The effect of thinning on microbial biomass C, N and basal respiration in black pine forest soils in Mudurnu, Turkey. Eur J Forest Res 2014 133: 131-139. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X.; Guan D.; Li W.; Sun D.; Jin C.; Yuan F.; Wang A.; Wu J. The effects of forest thinning on soil carbon stocks and dynamics: A meta-analysis. For Ecol Manage 2018 429: 36-43. [CrossRef]

- Marchi E.; Picchio R.; Spinelli R. Verani S.; Venanzi R.; Certini G. Environmental impact assessment of different logging methods in pine forests thinning. Ecol Eng 2014 70: 429-436. [CrossRef]

- Picchio R.; Spina R.; Calienno L.; Venanzi R.A.; Lo Monaco A. Forest operations for implementing silvicultural treatments for multiple purposes. It J Agron 2016 11 (1S): 156-161.

- Settineri G.; Mallamaci C.; Mitrović M.; Sidari M.; Muscolo A. Effects of different thinning intensities on soil carbon storage in Pinus laricio forest of Apennine South Italy. Eur J For Res 2018 137: 131-141. [CrossRef]

- Yang L.; Wang J.; Geng Y.; Niu S.; Tian D.; Yan T.; Liu W.; Pan J.; Zhao X.; Zhang C. Heavy thinning reduces soil organic carbon: Evidence from a 9-year thinning experiment in a pine plantation. Catena 2022 211: 106013.

- Smolander A.; Kitunen V.; Kukkola M.; Tamminen P. Response of soil organic layer characteristics to logging residues in three Scots pine thinning stands. Soil Biol Biochem 2013 66: 51-59. [CrossRef]

- Muscolo A.; Settineri G.; Attinà E. Early warning indicators of changes in soil ecosystem functioning. Ecol Indic 2015 48: 542-549. [CrossRef]

- Muscolo A.; Settineri G.; Bagnato S.; Mercurio R.; Sidari M. Use of canopy gap openings to restore coniferous stands in Mediterranean environment. iForest 2017 10 (1): 322-327. [CrossRef]

- Zhou X.; Zhou Y.; Zhou C.; Wu Z.; Zheng L.; Hu X.; Chen H.; Gan J. Effects of cutting intensity on soil physical and chemical properties in a mixed natural forest in Soutph eastern China. Forests 2015 6: 4495-4509. [CrossRef]

- Tang J.; Qi Y.; Xu M.; Misson L.; Goldstei A.H. Forest thinning and soil respiration in a ponderosa pine plantation in the Sierra Nevada. Tree Physiol 2005 25 (1): 57-66. 10.1093/treephys/25.1.57. PMID: 15519986. [CrossRef]

- Overby S.T.; Owen S.M.; Hart S.C.; Neary D.G.; Johnson N.C. Soil microbial community resilience with tree thinning in a 40-year-old experimental ponderosa pine forest. Appl Soil Ecol 2015 93: 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Richter A.; Schoning I.; Kahl T.; Bauhus J.; Ruess L. Regional environmental conditions shape microbial community structure stronger than local forest management intensity. For Ecol Manage 2018 409: 250-259. [CrossRef]

- Wu R.; Cheng X.; Han H. The effect of forest thinning on soil microbial community structure and function. Forests 2019 10 (4): 352.

- Zhou T.; Wang C.; Zhou Z. Impacts of forest thinning on soil microbial community structure and extracellular enzyme activities: A global meta-analysis). Soil Biol Biochem 2020 149, 107915. [CrossRef]

- Lei L.; Xiao W.; Zeng L.; Frey B.; Huang Z.; Zhu J.; Cheng R.; Li M-H. Effects of thinning intensity and understory removal on soil microbial community in Pinus massoniana plantations of subtropical China. Appl Soil Ecol 2021 167: 104055. [CrossRef]

- Asaye Z.; Zewdie S. Fine root dynamics and soil carbon accretion under thinned and un-thinned Cupressus lusitanica stands in Southern Ethiopia. Plant Soil 2013 366:261271. [CrossRef]

- Jonsson A.; Sigurdsson B.D. Effects of early thinning and fertilization on soil temperature and soil respiration in a poplar plantation. Icel Agric Sci 2010 23 (2): 97-109. [CrossRef]

- Clarke N.; Gundersen P.; Jönsson-Belyazid U.; Kjönaas O.J.; Persson T.; Sigurdsson B.D.; Stupak I.; Vesterdal L. Influence of different tree-harvesting intensities on forest soil carbon stocks in boreal and northern temperate forest ecosystems. For Ecol Manage 2015 51: 9-19. [CrossRef]

- Nave L.; Vance E.D.; Swanston C.W.; Curtis P.S. Harvest impacts on soil carbon storage in temperate forests. For Ecol Manag 2010 259 (5): 857-866. [CrossRef]

- Zhou D.; Zhao S.Q.; Liu S.; Oeding J. A meta-analysis on the impacts of partial cutting on forest structure and carbon storage. Biogeosciences 2013 10: 3691-3703.

- Kim S.; Han S.H.; Li G.; Yoon T. K.; Lee S-T.; Kim C.; Son Y. Effects of thinning intensity on nutrient concentration and enzyme activity in Larix kaempferi forest soils. J Ecol Environ 2016 40 (2). [CrossRef]

- Caihong Z.; Nier S.; Hao W. et al. Effects of thinning on soil nutrient availability and fungal community composition in a plantation medium-aged pure forest of Picea koraiensis. Sci Rep 2023 13, 2492. [CrossRef]

- Erkan N.; Güner Ş.T.; Aydın A.C. Thinning effects on stand growth, carbon stocks, and soil properties in Brutia pine plantations. Carbon Balance Manage 2023 18, 6. [CrossRef]

- Liu K-L.; Chen B-Y.; Zhang B.; Wang R-H.; Wang C-S. Understory vegetation diversity, soil properties and microbial community response to different thinning intensities in Cryptomeria japonica var. sinensis plantations. Front. Microbiol. 2023 14 :1117384. [CrossRef]

- Vesterdal L.; Dalsgaard M.; Felby C.; Raulund-Rasmussen K.; Jørgensen B.B. Effects of thinning and soil properties on accumulation of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus in the forest floor of Norway spruce stands. For Ecol Manage 1995 77 (1-3): 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Laganiere J.; Angers D.A.; Pare D. et al. Carbon accumulation in agricultural soils after afforestation: A meta-analysis. Global Change Biology 2010 16(1): 439–453.

- Bravo-Oviedo A.; Ruiz-Peinado R.; Modrego P.; Alonso R.; Montero G. Forest thinning impact on carbon stock and soil condition in Southern European populations of P. sylvestris L. For Ecol Manage 2015 357: 259-267. [CrossRef]

- Bárcena T.G.; Kiær L.P.; Vesterdal L.; Stefánsdóttir H.M.; Gundersen P; Sigurdsson B.D. Soil carbon stock change following afforestation in Northern Europe: a meta-analysis. Glob Change Biol 2014 20: 2393-2405. [CrossRef]

- Cheng X.; Yu M.; Li ZShort term effects of thinning on soil organic carbon fractions, soil properties, and forest floor in Cunninghamia lanceolata plantations. J Soil Sci Environ Manage 2018 9(2): 21-29. 10.5897/jssem2017.0661. [CrossRef]

- Molina A.J.; Bautista I.; Lull C.; del Campo A.; González-Sanchis M.; Lidón A. Effects of thinning intensity on forest floor and soil biochemical properties in an Aleppo pine plantation after 13 years: Quantity but also quality matters. Forests 2022 13(2): 255. [CrossRef]

- Bautista I.; Lidón A.; Lull C.; González-Sanchis M.; del Campo A.D. Thinning decreased soil respiration differently in two dryland Mediterranean forests with contrasted soil temperature and humidity regimes. Eur J For Res 2021 140: 1469-1485. [CrossRef]

- Gong C.; Tan Q.; Liu G.; Xu M. Forest thinning increases soil carbon stocks in China. For Ecol Manage 2021 482: 118812. [CrossRef]

- Cheng X.; Yu M.; Wang G.G. Effects of thinning on soil organic carbon fractions and soil properties in Cunninghamia lanceolata stands in Eastern China. Forests 2017 8 (6): 198. [CrossRef]

- Romeo F.; Settineri G.; Sidari M.; Mallamaci C.; Muscolo A. Responses of soil quality indicators to innovative and traditional thinning in a beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) forest. For Ecol Manage 2020 465:118106. [CrossRef]

- Tejedor J.; Saiz G.; Rennenberg H.; Dannenmann M. Thinning of beech forests stocking on shallow calcareous soil maintains soil C and N Stocks in the long run. Forests 2017 8 (5):167. [CrossRef]

- Bardgett R.D.; Streeter T.C.; Bol R. Soil microbes compete effectively with plants for organic-nitrogen inputs to temperate grasslands. Ecology 2023 84 (5): 1277-1287. [CrossRef]

- Lee K.H.; Jose S. Soil respiration, fine root production, and microbial biomass in cottonwood and loblolly pine plantations along a nitrogen fertilization gradient. For Ecol Manage 2023 185 (3): 263-273.

- Allison S.D. Soil minerals and humic acids alter enzyme stability: implications for ecosystem processes. Biogeochemistry 2006 81 (3): 361-373. [CrossRef]

- De Deyn G.B.; Quirk H.; Yi Z.; Oakley S.; Ostle N.J.; Bardgett R.D. Vegetation composition promotes carbon and nitrogen storage in model grassland communities of contrasting soil fertility. J Ecol 2009 97 (5): 864-875. [CrossRef]

- Billings S.A.; Lichter J.; Ziegler S.E.; Hungate B.A.; Richter D.B. A call to investigate drivers of soil organic matter retention vs. mineralization in a high CO2 world. Soil Biol Biochem 2010 42 (4): 665-668. [CrossRef]

- Nazari M.; Pausch J.; Bickel S.; et al. Keeping thinning-derived deadwood logs on forest floor improves soil organic carbon, microbial biomass, and enzyme activity in a temperate spruce forest. Eur J Forest Res 2023 142, 287–300. [CrossRef]

- Muscolo A.; Settineri G.; Romeo F.; Mallamaci C. Soil biodiversity as affected by different thinning intensities in a Pinus laricio stand of Calabrian Apennine, South Italy. Forests 2021 12 (1): 108. [CrossRef]

- Tsurho K.; Ao B. Community analysis of soil Acarina in a Natural Forest and Jhum land ecosystem of Mokokchung, Nagaland. JOSR J Appl Phys 2014 6 (4): 50-54.

- Menta C.; Renelli S. Soil health and arthropods: from complex system to worthwhile investigation. Insects 2020 11 (1): 54. 0.3390/insects11010054.

- Nsengimana V.; Kaplin B.A.; Francis F.; Nsabimana D. Use of soil and litter arthropods as biological indicators of soil quality in forest plantations and agricultural lands: A Review. Faun Entomol 2018 l7: 1-12.

- Chen X.; Chen H.Y.; Chen X.; Wang J.; Chen B.; Wang D.; Guan Q. Soil labile organic carbon and carbon-cycle enzyme activities under different thinning intensities in Chinese fir plantations. Appl Soil Ecol 2016 107: 162-169.

- Geng Y.; Dighton J.; Gray D. The effects of thinning and soil disturbance on enzyme activities under pitch pine soil in New Jersey Pinelands. Appl Soil Ecol 2012 62: 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Shen Y.; Cheng R.; Xiao W.; Jang S.; Guo Y.; Wang N.; Zeng L.; Lei L.; Wang X. Labile organic carbon pools and enzyme activities of Pinus massoniana plantation soil as affected by understory vegetation removal and thinning. Sci Rep 2018 8: 573. [CrossRef]

- 65. Hedo de Santiago J.; Lucas-Borja M.E.; Wic-Baena C.; Andrés-Abellán M.; de las Heras J. Effects of thinning and induced drought on microbiological soil properties and plant species diversity at dry and semiarid locations. Land Degrad Dev 2015 27(4): 1151-1162. [CrossRef]

- 66. Kim S.; Li G.; Han S.H.; Kim H-J.; Kim C.; Lee S-T.; Son Y. Thinning affects microbial biomass without changing enzyme activity in the soil of Pinus densiflora Sieb. et Zucc. forests after 7 years. Ann For Sci 2018 75: 13. [CrossRef]

- 67. Sinsabaugh R.L.; Lauber C.L.; Weintraub M.N.; Ahmed B.; Allison S.D.; Crenshaw C.; Contosta A.R.; Cusack D.; Frey S.; Gallo M.E.; Gartner T.B.; Hobbie S.E.; Holland K.; Keeler B.L.; Powers J.S.; Stursova M.; Takacs-Vesbach C.; Waldrop M.P.; Wallenstein M.D.; Zak D.R.; Zeglin L.H. Stoichiometry of soil enzyme activity at global scale. Ecol Lett 2008 11(11):1252-1264. [CrossRef]

- 68. Xu M.; Liu H.; Zhang Q.; Zhang Z.; Ren C.; Feng Y.; Yang G.; Han X.; Zang W. Effect of forest thinning on soil organic carbon stocks from the perspective of carbon-degrading enzymes. Catena 2002 218: 106560.

- 69. Hwang J.; Son Y. Short-term effects of thinning and liming on forest soils of pitch pine and Japanese larch plantations in central Korea. Ecol Res 2006 21: 671-680. [CrossRef]

- 70. Rytter R-M.; Rytter L. Effects on soil characteristics by different management regimes with root sucker generated hybrid aspen (Populus tremula L. × P. tremuloides Michx.) on abandoned agricultural land. iForest 2018 11: 619-627. – [online 2018-10-04]. [CrossRef]

- 71. Akburak S.; Makineci E. Thinning effects on soil and microbial respiration in a coppice-originated Carpinus betulus L. stand in Turkey. iForest 2016 9: 783-790. [CrossRef]

- 72. Budiaman A.; Haneda N.F.; Syaidah K.H. Temporal effects of forest thinning on spring tails (Entomobryomorpha: Collembola) assemblages at pulai (Alstonia scholaris) forest plantation in Banten. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2020 528 012027.

- 73. Lull C.; Bautista I.; Lidón A.; del Campo A.D. González-Sanchis M.; García-Prats A. Temporal effects of thinning on soil organic carbon pools, basal respiration and enzyme activities in a Mediterranean Holm oak forest. For Ecol Manage 2020 464: 118088. [CrossRef]

- 74. Van Damme F.; Mertens H.; Heinecke T.; Lefevre L.; De Meulder T.; Portillo-Estrada M.; Roland M.; Gielen B:; Janssens I.A.; Verheyen K.; Campioli M. The Impact of Thinning and Clear Cut on the Ecosystem Carbon Storage of Scots Pine Stands under Maritime Influence in Flanders, Belgium. Forests 2022 13: 1679. [CrossRef]

| Thinning intensity | OM | MBC | FDA | CAT | DHA |

| T1* | 140 | 18 | 28 | 128 | 25 |

| T2* | 215 | 25 | 57 | 154 | 89 |

| T3§ | -43 | -40 | 3 | 27 | 51 |

| T4§ | -73 | -51 | -50 | -35 | 130 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).