3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of TiO2@N-Doped C

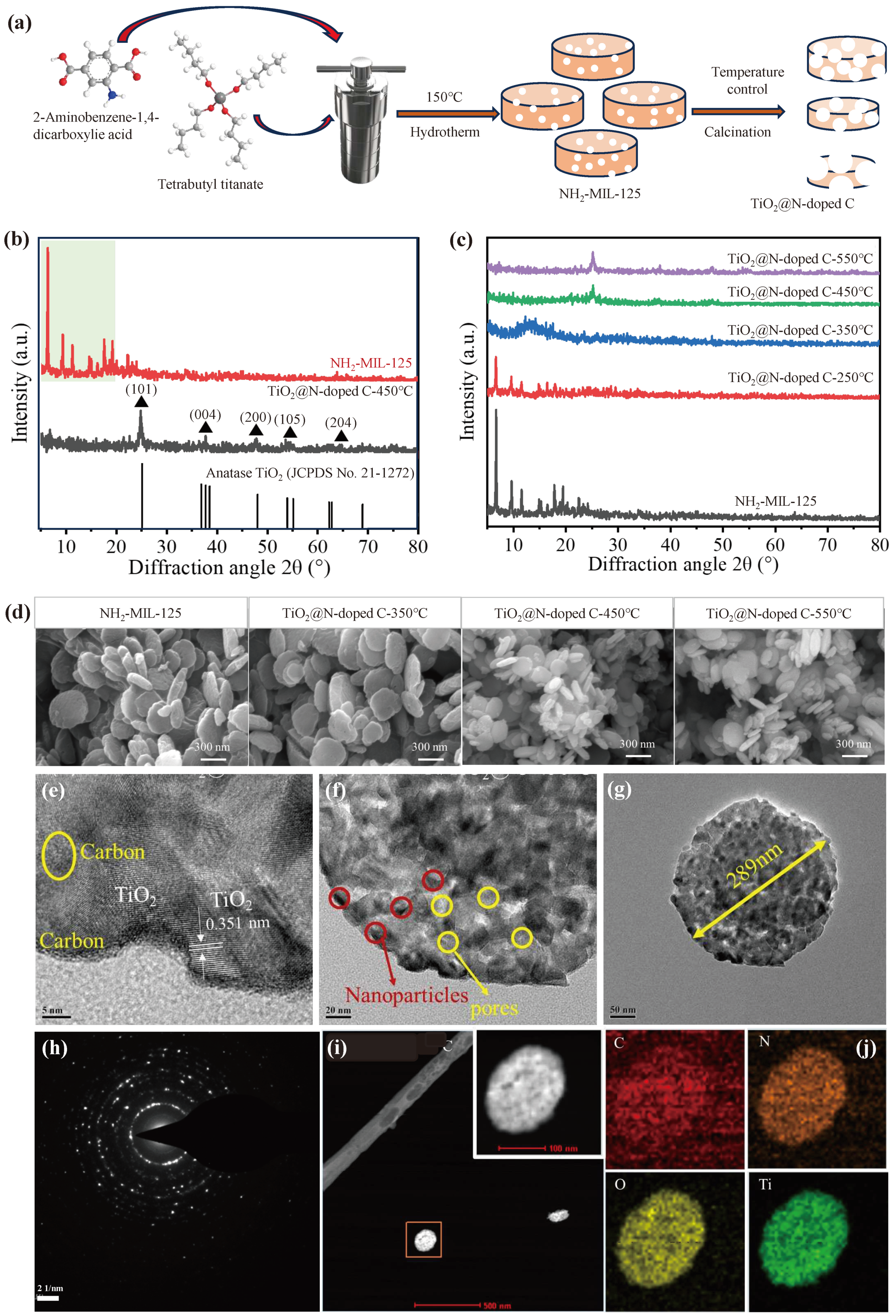

The overall fabrication of the TiO

2@N-doped C composite is schematically illustrated in

Figure 1a. In order to explore the crystal structure of the sample prepared in the experiment, X-ray Diffraction (XRD) tests were first conducted. NH

2-MIL-125 samples show typical diffraction peaks at 6.67°, 9.62°, 11.48°, 14.90°, 16.50°, 17.89° and 19.42°. The outcomes indicated that the synthesis of NH

2-MIL-125 was successful and that the produced MOF exhibited acceptable crystallinity. TiO

2@N-doped C-450°C was obtained by calcination of NH

2-MIL-125, and the characteristic peak of NH

2-MIL-125 totally vanished during the process. The XRD pattern of TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C was compared with the standard diffraction card of acanite TiO

2 (JCPDSNo.21−1272). It was found that peaks of 25.06°, 38.10°, 47.89°, 53.70° and 61.46° correspond to the (101), (004), (200), (105) and (204) planes of anatase, respectively. The results show that pyrolysis of NH

2-MIL-125 to produce anatase TiO

2 is successful. In addition, XRD characterization of TiO

2@N-doped C is significantly different with different calcination temperatures (

Figure 1b,c). The calcination temperature of TiO

2@N-doped C-250 °C is too low, which causes insufficient pyrolysis. The characteristic peaks of NH

2-MIL-125 can still be seen at 6.63°, 9.65° and 11.64°, but the peak intensity is reduced significantly. This may be due to the partial disintegration and recombination of the NH

2-MIL-125 structure. When the temperature of the calcination reaches 350 °C, only a carbon sheath peak at 13.19° and no TiO

2 related peak pattern are visible, indicating that the NH

2-MIL-125 structure is totally broken down. TiO

2 has not yet formed crystals, and the carbon element that was liberated during the calcination has been doped into the compound. The distinctive peak of anatase TiO

2 is clearly seen when the temperature hits 450 °C. Following that, the intensity of the anatase TiO

2 characteristic peak no longer varies considerably with the rise in calcination temperature, but the crystallinity of TiO

2 is more excellent.

From SEM images, the prepared NH

2-MIL-125 showed circular flake shape with an average diameter of about 422 nm (

Figure 1d). In TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C, the thickness of TiO

2 like circular tablets is about 50 nm and the diameter is about 140 nm. The sample has a thickness of around 60 nm and a diameter of about 370 nm at TiO

2@N-doped C-350 °C. The sample has a thickness of around 70 nm and a diameter of about 450 nm at TiO

2@N-doped C-250 °C. It follows that it is evident that as the calcination temperature rises, the average particle size of the sample particles shrinks to some extent while maintaining its round pill shape. This might be because as the calcination temperature rises, the network structure of NH

2-MIL-125 gradually loses its capacity to crystallize and the organic molecules in the skeleton break down.

The shape and crystal structure of TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C composites were obtained by TEM. The observation of amorphous carbon shows that a large amount of TiO

2 is distributed in the carbon matrix, and finally forms TiO

2@C composite. The sample obtained after calcination still maintains a porous structure, as seen by the presence of TiO

2 nanoparticles and pores (

Figure 1e,f). This porous construction can increase the photocatalytic efficiency by exposing as many active sites as feasible while also facilitating the transmission and diffusion of electrons during catalysis. In the adsorption experiment, more investigation into porous structure will be done at N/ TiO

2@C-450 °C, on which a lattice spacing of 0.351 nm was found, compatible with the lattice spacing of the crystal planes of anatase TiO

2 (101) (

Figure 1g). From TEM observation, the diameter of the TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C is approximately 289 nm (

Figure 1g). At TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C, a lattice spacing of 0.351 nm was found, which was compatible with the lattice spacing of the crystal planes of anatase TiO

2 (101) (

Figure 1h). Titanium, oxygen, carbon, and nitrogen are all further confirmed by the element mapping (

Figure 2i,j). It is evident that at TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C, the distribution of element titanium, oxygen, carbon, and nitrogen is quite uniform. It can be argued that during calcination, the nitrogen element contained in the organic ligand 2-amino-terephtharic acid is released and then doped into the sample, while the titanium element in NH

2-MIL-125 is grown in situ to form TiO

2, which is uniformly dispersed in the porous carbon skeleton, and ultimately the nitrogen-doped TiO

2@C is successfully formed.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram and characterization of the TiO2@N-doped C composite. (a) Fabrication of TiO2@N-doped C composite. (b,c) NH2-MIL-125 and TiO2@N-doped C composites with calcination temperature of 250 °C,350 °C,450 °C and 550 °C. (d) SEM images of NH2-MIL-125 and TiO2@N-doped C composites with calcination temperature of 250 °C,350 °C,450 °C and 550 °C. (e,f) and (g) TEM images of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C. (h) Electron diffraction image of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C. (i,j) The element mapping of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram and characterization of the TiO2@N-doped C composite. (a) Fabrication of TiO2@N-doped C composite. (b,c) NH2-MIL-125 and TiO2@N-doped C composites with calcination temperature of 250 °C,350 °C,450 °C and 550 °C. (d) SEM images of NH2-MIL-125 and TiO2@N-doped C composites with calcination temperature of 250 °C,350 °C,450 °C and 550 °C. (e,f) and (g) TEM images of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C. (h) Electron diffraction image of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C. (i,j) The element mapping of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C.

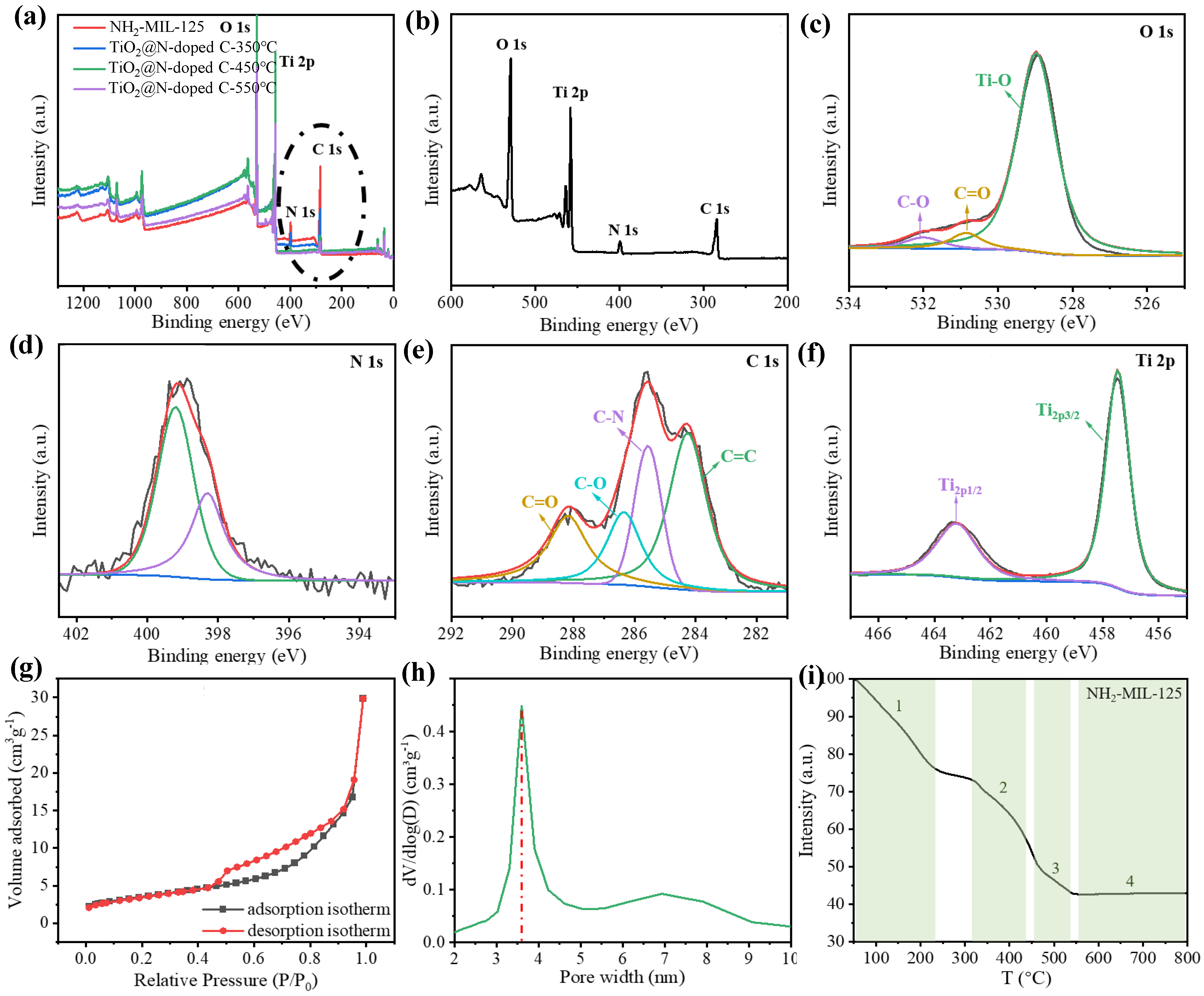

Figure 2.

Chemical characterization of the TiO2@N-doped C composites. (a,b) The survey XPS spectra of NH2-MIL-125, TiO2@N-doped C-250 °C, TiO2@N-doped C-350 °C, TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C and TiO2@N-doped C-550 °C. The high-resolution XPS spectra of (c) O 1s, (d) N 1s, (e) C 1s and (f) Ti 2p of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C. (g) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C. (h) pore size distributions of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C. (i) Thermogravimetric curve of NH2-MIL-125.

Figure 2.

Chemical characterization of the TiO2@N-doped C composites. (a,b) The survey XPS spectra of NH2-MIL-125, TiO2@N-doped C-250 °C, TiO2@N-doped C-350 °C, TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C and TiO2@N-doped C-550 °C. The high-resolution XPS spectra of (c) O 1s, (d) N 1s, (e) C 1s and (f) Ti 2p of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C. (g) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C. (h) pore size distributions of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C. (i) Thermogravimetric curve of NH2-MIL-125.

The elemental composition and valence information of TiO

2@N-doped C were subsequently examined using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), which was utilized to test the material composition (

Figure 2a,b). When the temperature is too high, all the nitrogen will be released and no longer doped into the TiO

2@C composite, and the peaks value of carbon and nitrogen will decrease with the increase of calcination temperature. When the temperature reaches 550 °C, the peak of nitrogen is close to zero. However, the proper calcination temperature is crucial, as XRD pattern analysis has shown that anatase TiO

2 is difficult to produce or has poor crystallinity at too low temperatures. The calcination temperature of 450 °C can be used as the equilibrium temperature between nitrogen doping and TiO

2 crystallinity. Three peaks at 532.0 eV, 530.9 eV, and 528.9 eV, which are associated with the C-O bond, C=O bond, and Ti-O bond, respectively, can be seen in the XPS spectra of O 1s (

Figure 2c). The surface hydroxyl oxygen, which is essential for the photodegradation of contaminants, is responsible for the development of the C-O bond. To fight contaminants, the hydroxyl radical OH• can be created when it interacts with photogenic holes. N 1s (

Figure 2d) displayed a broad peak between 398.4 and 399.4 eV. It is consistent with other results and typical Ti-N structures in nitrogen-doped TiO

2 [

25]. And the C=C peak (

Figure 2e) at 288.2 eV, 286.4 eV, 285.6 eV, and 284.2 eV correspond to C=O, C-O, C-N, and C=C, respectively. For pure anatase TiO

2, Ti-O peaks is located at 458.5 eV, 464.5 eV. The Ti 2p peak at N/TiO

2@C-450 °C is 457.5 eV, 463.5 eV, which is a 6.0 eV energy splitting. The peaks of Ti 2p showed in Fig. 2f centered at about 463.2 eV and 457.5 eV belonged to Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2, respectively, which confirmed the Ti

4+ species in the form of TiO

2 nanoparticles. The Ti 2p peak at TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C is slightly moved to a lower binding energy when compared to pure anatase TiO

2, which is brought on by nitrogen doping altering the local chemical environment of titanium ions. The successful doping of nitrogen into TiO

2@C, as shown by the test findings from XPS, has positive implications for reducing the band gap width of TiO

2 and increasing its visible light activity. We also test the relative amount of C, N in the sample by elemental analyzer. The content of nitrogen decreases with the increase of heat treatment temperature. A as high as 0.12% N/C ratio is obtained under heat treatment of 450 °C.

The nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherm samples at TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C (

Figure 2g) exhibit the conventional type IV isotherm and type H3 hysteresis loop. The pore size distribution was calculated using the nonlocal density function model (NLDFT) based on data from N

2 adsorption (

Figure 2h). TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C has a specific surface area of 63 m

2/g, which is significantly less than that of NH

2-MIL-125 but still significantly larger than that of other TiO

2 catalysts. Therefore, basic fuchsin, rhodamine B, and tetracycline hydrochloride can be degraded at more active sites thanks to the large specific surface area of TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C.

BET data need to be interpreted in combination with thermogravimetric curves (

Figure 2g,h). The specific surface area of the samples decreases and the average pore size increases with increasing roasting temperature, but for different reasons. The sample changes at about 200 °C as a result of the elimination of any remaining solvent. When the temperature reaches 350 °C, the porous structure collapses and the crystal skeleton begins to disintegrate, greatly reducing the specific surface area. The decomposition of the crystal skeleton and the collapse of the porous structure make the specific surface area decrease sharply. When the calcination temperature was further increased to 450 °C, the BET data changed due to the recrystallization of TiO

2 and the formation of pyrolytic carbon substrates. However, the skeleton shrank significantly once more at 550 °C, and the specific surface area dropped to 13 m

2/g, making it difficult for contaminants and the catalyst to make contact. Therefore, by adjusting the calcination temperature, the TiO

2@N-doped C catalyst with the best photocatalytic effect was created at 450 °C.

Table 1.

Textural Characteristics of NH2-MIL-125, TiO2@N-doped C-200°C, TiO2@N-doped C-350°C, TiO2@N-doped C-450°C and TiO2@N-doped C-550°C.

Table 1.

Textural Characteristics of NH2-MIL-125, TiO2@N-doped C-200°C, TiO2@N-doped C-350°C, TiO2@N-doped C-450°C and TiO2@N-doped C-550°C.

| Sample |

SBET

(m2g-1) |

Vtotal

(cm3g-1) |

Average Pore Diameter (nm) |

| NH2-MIL-125 |

539 |

0.087 |

5.32 |

| TiO2@N-doped C-200 °C |

763 |

0.168 |

6.54 |

| TiO2@N-doped C-350 °C |

89 |

0.157 |

9.30 |

| TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C |

63 |

0.141 |

10.89 |

| TiO2@N-doped C-550 °C |

13 |

0.046 |

12.26 |

3.2. Photocatalytic Degradation of TiO2@N-Doped C

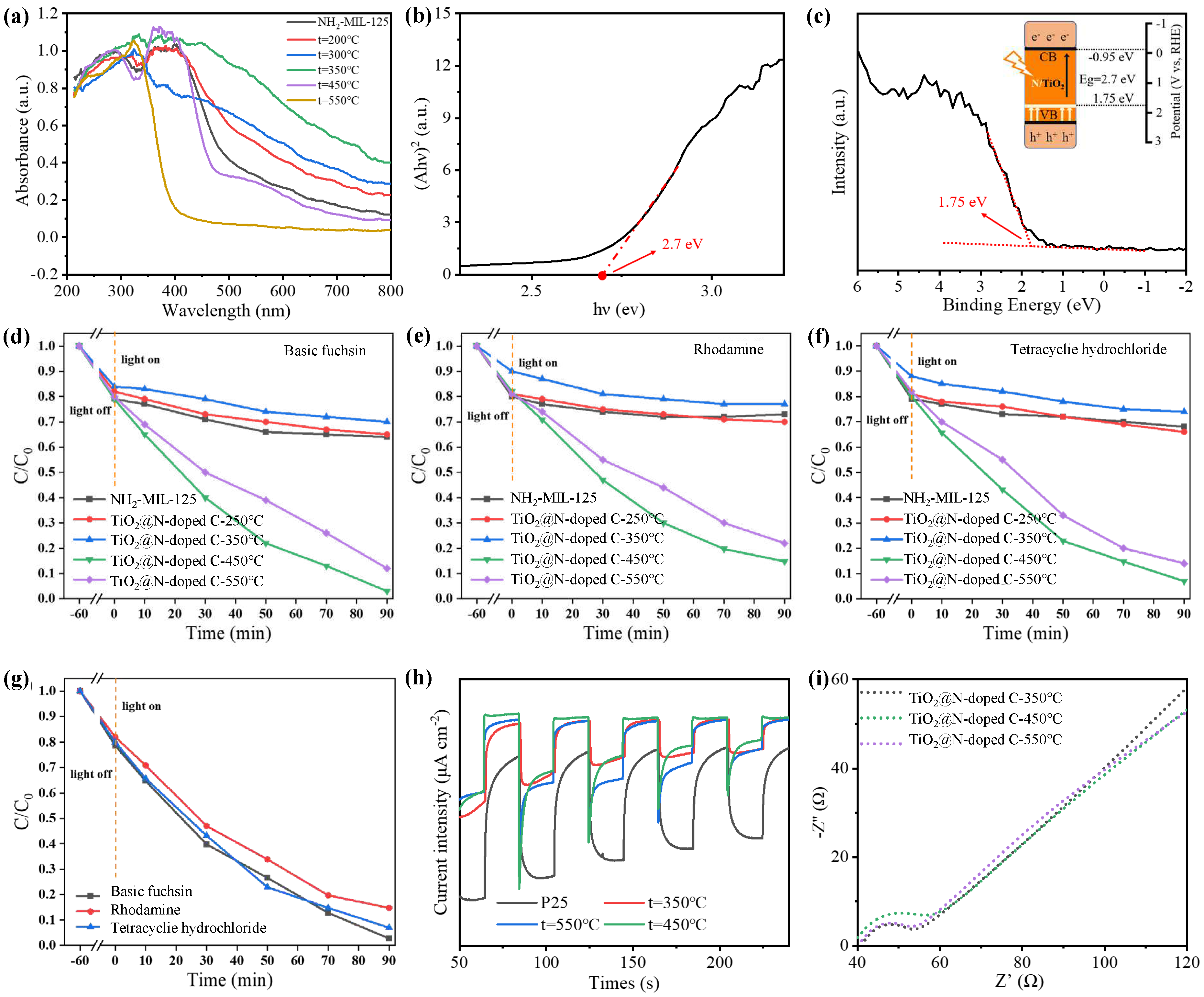

The light absorption capacity of TiO

2@N-doped C composites was investigated by UV-Vis absorption test (

Figure 3a). NH

2-MIL-125 is yellow, as was already described. The sample's color continues to deepen as the calcination temperature rises due to the breakdown of the crystal skeleton and collapse of the porous structure. The sample's hue changes to brown at 350 °C, when it exhibits the best ability to absorb visible light. As the calcination temperature increases after 350 °C, TiO

2 crystals start to form and the sample's color lightens. The sample is nearly white at 550 °C, and visible light can no longer be absorbed. We know that P25, the white commercial grade TiO

2, has poor absorption capabilities for visible light. The optimal catalyst for the best visible light absorption performance at 400-800 nm should be TiO

2@N-doped C-350 °C. However, the photocatalytic activity of TiO

2@N-doped C-350 °C is subpar due to the absence of TiO

2 crystal. The most acceptable visible light catalyst, according to a thorough comparison between the sample's photoabsorption capacity and TiO

2 content, is TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C.

Compared with P25, the as-prepared TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C sample has a wider absorption range, which is because nitrogen in the organic connector is released and doped into the sample during calcination, which reduces the wide band gap of TiO

2, and causes the light absorption range to shift to the visible region. The prohibited band spectra (

Figure 3b) and valence band spectra (

Figure 3c) of TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C can be used to compute the energies of the valence band, conduction band, and band gap, which are -0.95 eV, 1.75 eV, and 2.7 eV, respectively. The TiO

2@N-doped C0-450 °C band gap created in this work is narrower than that of anatase TiO

2, which has a band gap energy of 3.22 eV, making it more suitable for light absorption and photocatalytic processes.

Under xenon lamp illumination, the photocatalytic activity of TiO

2@N-doped C composites were assessed using dealkalized fuchsin, Rhodamine B, and tetracycline hydrochloride. These three contaminants all degrade in a very similar way. Only NH

2-MIL-125 is capable of decomposing basic fuchsin (

Figure 3d), lowering the pollutant concentration to 65%. This is because NH

2-MIL-125 can carry out a certain amount of physical adsorption due to its large specific surface area and micropore structure. The capability for deterioration varies significantly amongst TiO

2@N-doped C samples. At 350 °C, TiO

2@N-doped C exhibited the lowest degradation ability compared to other catalysts. TiO

2@N-doped C-350 °C showed the worst degradation ability, and 70% of basic fuchsin remained in the solution after degradation, even less than NH

2-MIL-125 adsorption effect. This is mainly due to two reasons: firstly, TiO

2 does not form at this temperature and prevents photocatalytic reactions; secondly, at 350 °C NH

2-MIL-125 undergoes significant pyrolysis that rapidly changes its skeletal structure and reduces specific surface area sharply. Moreover, there is an overall increase in pore size resulting in mesoporous pores and causing a decline in its adsorption effectiveness. The degradation of 99.7% of basic fuchsin at TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C was the highest among all samples within 90 minutes. Although the anatase TiO

2 obtained by heat treatment at 550°C has the highest content and the best crystal form, implying the most superior photocatalytic effect. While, the above characterization results indicated that reducing nitrogen content at TiO

2@N-doped C-550 °C decreases the utilization efficiency of visible light. Consequently, the degradation efficiency of basic fuchsin is not as good as that achieved with TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C.

The degradation of Rhodamine B and tetracycline hydrochloride exhibited similar trends in the above samples (

Figure 3e,f). NH

2-MIL-125 achieved a 73% reduction in the content of Rhodamine B through physical adsorption. Among the tested catalysts, TiO

2@N-doped C-350 °C demonstrated the lowest degradation efficiency with only 23% of pollutants being degraded, while TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C exhibited the highest degradation effect by degrading 89.9% of Rhodamine B within 90 minutes. Physical adsorption by NH

2-MIL-125 resulted in a decrease in the content of tetracycline hydrochloride to 68%. Similarly, TiO

2@N-doped C-350 °C showed inferior performance with only a 26% degradation rate for pollutants, whereas TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C displayed superior degradation capability by achieving a remarkable removal rate of 93% for tetracycline hydrochloride within the same time frame (

Figure 3g). In

Table 2, we summarize the recent works on the degradation performance of TiO

2 composites against tetracycline. In comparison, our materials show an outstanding catalytic property.

Under xenon lamp irradiation, we use photocurrent test to investigate the phenomenon of photogenerated carrier transport in samples. The photocurrent intensity of all TiO

2@N-doped C samples is relatively high, indicating a slow photogenerated carrier recombination rate (

Figure 3h). This is mainly because titanium dioxide is combined with the carbon matrix, the porous structure of the carbon skeleton shorters the carrier transfer distance, so that the photogenerated electron pairs can be effectively separated. In addition, the large specific surface area of the carbon skeleton exposes more active sites, making the carrier transmission and diffusion more convenient. In short, the combination of carbon skeleton and TiO

2 enhances the photocurrent intensity of the composite compared with commercial grade titanium dioxide P25. It is well known that the higher the photocurrent density, the better the ability to separate photogenerated electrons and holes. Therefore, compared with P25, TiO

2@N-doped C improves the carrier separation efficiency and inhibits the photogenerated carrier recombination. To confirm this, we further studied the resistance of interfacial charge conversion by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. As shown in

Figure 3i, the radii of all TiO

2@N-doped C composites are small, indicating that the TiO

2@N-doped C catalyst has higher interfacial charge separation efficiency and better electrical conductivity, which is similar to the trend of photocurrent response test results

In summary, the optimal balance between anatase TiO2 formation and nitrogen doping is achieved when the calcination temperature reaches 450 °C, and TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C exhibits the highest photocatalytic capacity.

Figure 3.

(a) DRS spectra of TiO2@N-doped C with calcination temperature for 200 °C, 300 °C, 350 °C, 450 °C, 550 °C and NH2-MIL-125. (b) Band gap and (c) Valence band spectra of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C (with Energy level diagram of TiO2@N-doped C -450 °C). Photocatalytic degradation efficiencies of (d) basic fuchsins, (e) Rhodamine B, and (f) tetracycline hydrochloride over NH2-MIL-125,TiO2@N-doped C-200 °C,TiO2@N-doped C-350 °C, TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C and TiO2@N-doped C-550 °C under the xenon lamp irradiation. (g) Degradation plots of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C. (h) Transient photocurrent responses of TiO2@N-doped C with calcination temperature for 350°C, 450°C, 550°C and NH2-MIL-125. (i) EIS Nyquist plots of TiO2@N-doped C with calcination temperature for 350°C, 450°C, and 550°C.

Figure 3.

(a) DRS spectra of TiO2@N-doped C with calcination temperature for 200 °C, 300 °C, 350 °C, 450 °C, 550 °C and NH2-MIL-125. (b) Band gap and (c) Valence band spectra of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C (with Energy level diagram of TiO2@N-doped C -450 °C). Photocatalytic degradation efficiencies of (d) basic fuchsins, (e) Rhodamine B, and (f) tetracycline hydrochloride over NH2-MIL-125,TiO2@N-doped C-200 °C,TiO2@N-doped C-350 °C, TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C and TiO2@N-doped C-550 °C under the xenon lamp irradiation. (g) Degradation plots of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C. (h) Transient photocurrent responses of TiO2@N-doped C with calcination temperature for 350°C, 450°C, 550°C and NH2-MIL-125. (i) EIS Nyquist plots of TiO2@N-doped C with calcination temperature for 350°C, 450°C, and 550°C.

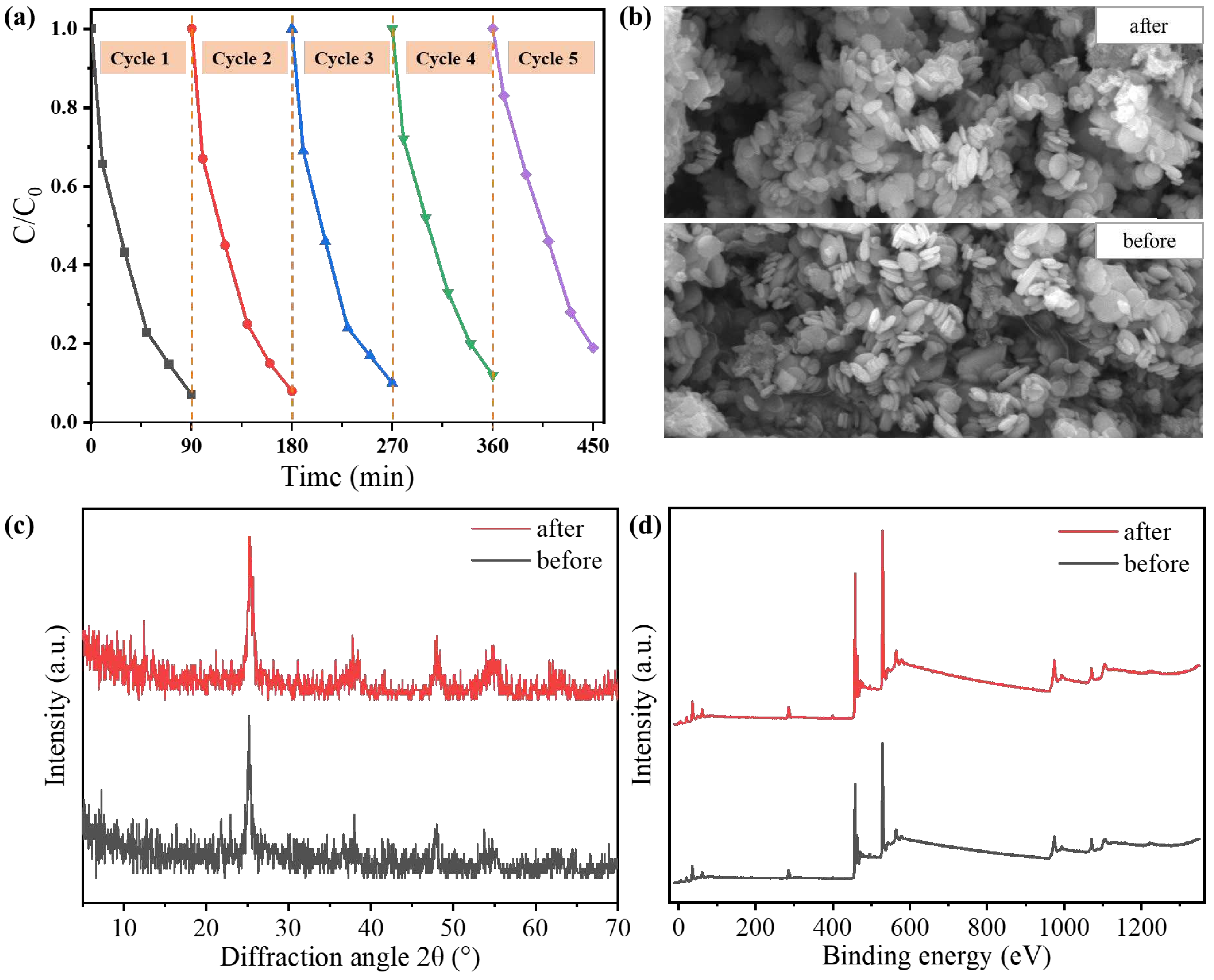

Tetracycline hydrochloride was used as an example to investigate the stability and reusability of the TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C catalyst. The same sample was employed for five consecutive degradation cycles under identical conditions (

Figure 4a). No significant changes were observed after five cycles, although the degradation capacity decreased from 93% to 81%. This decrease in degradation capacity is primarily attributed to the blockage of mesoporous channels in TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C by pollutants over prolonged reaction times, making it challenging to effectively clean and negatively impacting the recyclability of the catalyst Additionally, the inevitable loss of the photocatalyst during repeated use will also result in a decrease in degradation efficiency. Moreover, a comparison of SEM images, XRD spectra, and XPS spectra (

Figure 4b–d) before and after the reaction reveals that there is no significant change in the structure, morphology characteristics, and chemical composition of TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C before and after testing. TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C exhibits excellent photocatalytic ability, stability, and reusability; it has great potential as a visible photocatalyst for various types of pollutants.

3.3. Photocatalytic Mechanism

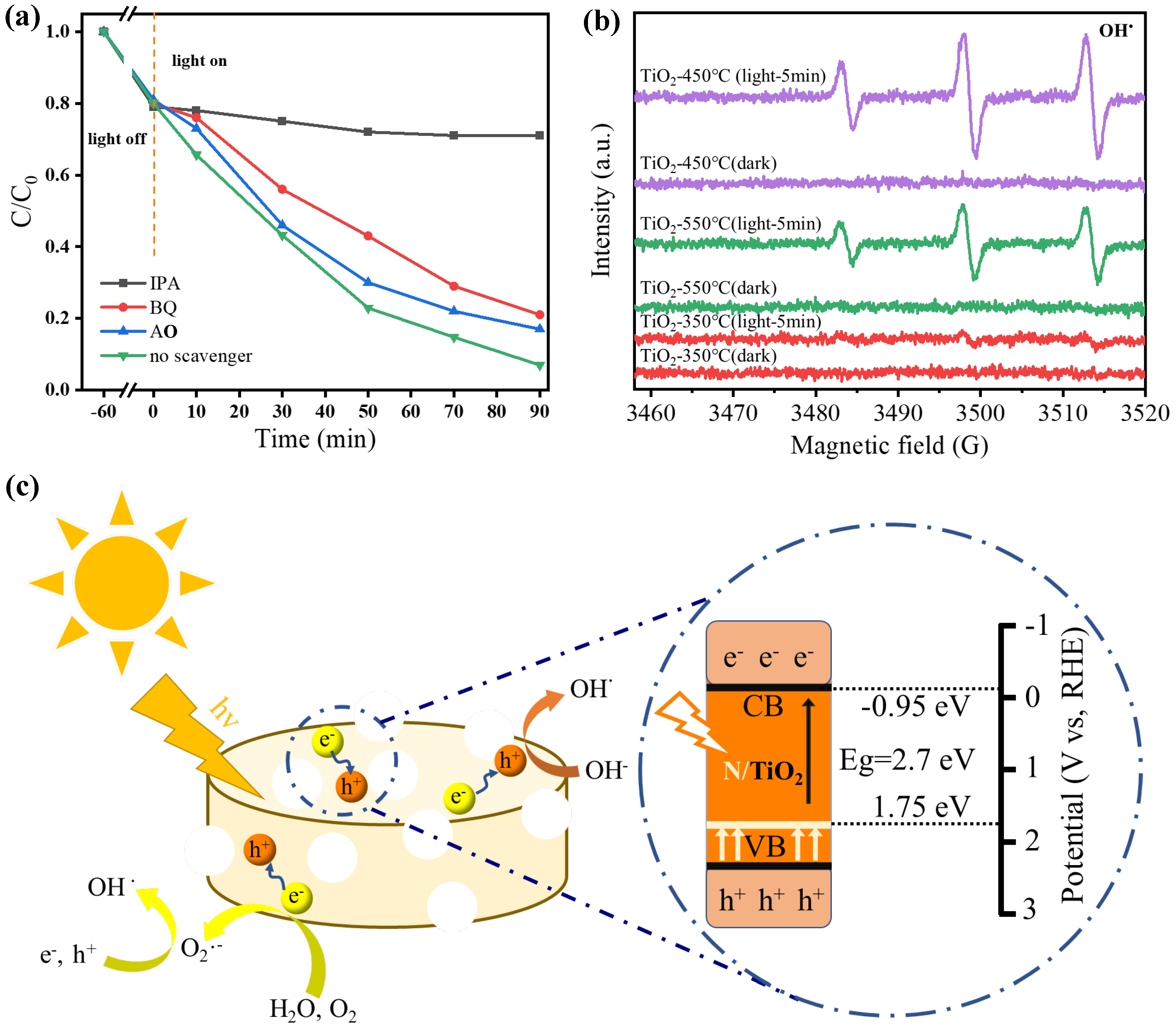

The photocatalytic mechanism of TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C nanomaterials during visible light degradation was investigated by conducting multiple trapping experiments using tetracycline hydrochloride as an example. Three additional trapping reagents were added to the reaction solution, among which ammonium oxalate (AO) was used to trap e

-, benzoquinone (BQ) was used to trap O

2•, and isopropyl alcohol (IPA) was used to trap OH• (

Figure 5a). The addition of each trapping agent will affect the degradation rate of tetracycline hydrochloride, among which isopropyl alcohol has the most prominent inhibitory effect among all trapping agents. The degradation efficiency of TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C was reduced significantly to 71% after the addition of isopropyl alcohol, indicating that OH• plays a leading role in the degradation reaction of tetracycline hydrochloride under visible light irradiation. In addition, the addition of ammonium oxalate and benzoquinone (BQ) also had a certain effect on the degradation rate, suggesting that e

- and O

2•

- were also involved in the process, but did not play a major role. In conclusion, OH• was produced by the TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C catalyst during the photocatalysis process, which enhanced the oxidation capacity of the active substance and improved its ability to degrade tetracycline hydrochloride greatly.

DMPO trapping agent was added to the photocatalytic reaction system to detect active free radicals by EPR. Therefore, electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy was used to detect the signals of OH• radicals generated by TiO

2@N-doped C-350 °C, TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C and TiO

2@N-doped C-550 °C under visible light irradiation (

Figure 5b). Obviously, regardless of dark or light conditions, TiO

2@N-doped C-350 °C OH, almost no occurrence of free radicals, this is due to the TiO

2 of TiO

2@N-doped C-350 °C has not formed. At TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C and TiO

2@N-doped C -550 °C, almost no OH• free radicals increased. This indicates that the photogenerated electrons on anatase TiO

2 were transferred rapidly through the carbon skeleton, resulting in the production of a large amount of OH• free radicals. TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C exhibits the highest number of OH• free radicals due to nitrogen doping, which enhances the sample's utilization rate of visible light. This phenomenon further confirms the excellent photocatalytic effect of nitrogen-doped TiO

2 supported by a carbon skeleton.

Figure 5.

(a) The photocatalytic ability of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C for the degradation of tetracycline with or without adding IPA, BQ, and AO under visible light. (b) EPR spectra of the OH• on the TiO2@N-doped C-350 °C, TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C, and TiO2@N-doped C-550 °C catalysts. (c) The probable photocatalytic mechanism of tetracycline degradation by TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C under visible light irradiation.

Figure 5.

(a) The photocatalytic ability of TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C for the degradation of tetracycline with or without adding IPA, BQ, and AO under visible light. (b) EPR spectra of the OH• on the TiO2@N-doped C-350 °C, TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C, and TiO2@N-doped C-550 °C catalysts. (c) The probable photocatalytic mechanism of tetracycline degradation by TiO2@N-doped C-450 °C under visible light irradiation.

Based on the test results and analysis mentioned above, a possible photocatalytic reaction mechanism of TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C can be proposed (

Figure 5c). Under visible light irradiation, nitrogen-doped TiO

2 nanoparticles can efficiently produce charge carriers. At this stage, the unique porous structure of TiO

2@N-doped C-450 °C provides additional pathways for the movement of charge carriers, facilitating easy transfer of electrons to the carbon framework and effectively separating photogenerated electrons and holes. During the degradation process, O

2•

- free radicals are generated through reactions between electrons enriched on the carbon framework with H

2O and O

2. The electrons generate from N/TiO

2@C-450 °C under visible light irradiation is 2.7 eV, which have a much lower work function than pure TiO

2 (3.2 eV). Meanwhile, due to the lower valence band (VB) of nitrogen-doped TiO

2 compared to the REDOX potential of O

2/•O

2ˉ• (-0.13 eV), the oxidation of H

2O by holes on TiO

2 leads to the generation of superoxide anion radical species (O

2ˉ•), which actively contribute to the degradation process, ultimately resulting in the degradation of organic pollutants such as basic fuchsin.