Submitted:

04 December 2023

Posted:

05 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

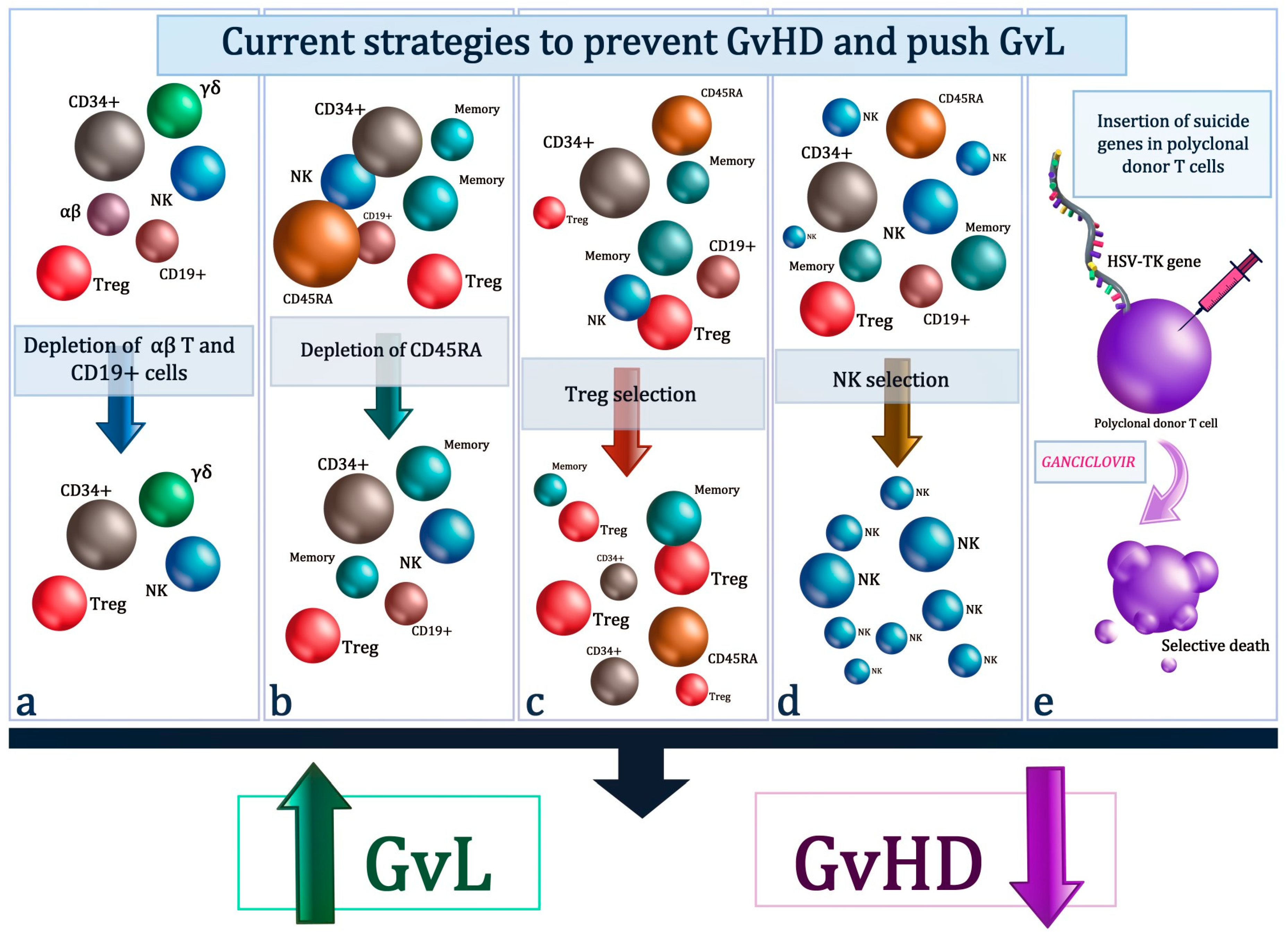

2. Removal Of αβ T-Cells

2.1. Removal Of Naive T-Cells (CD45RA T-Cell Subset)

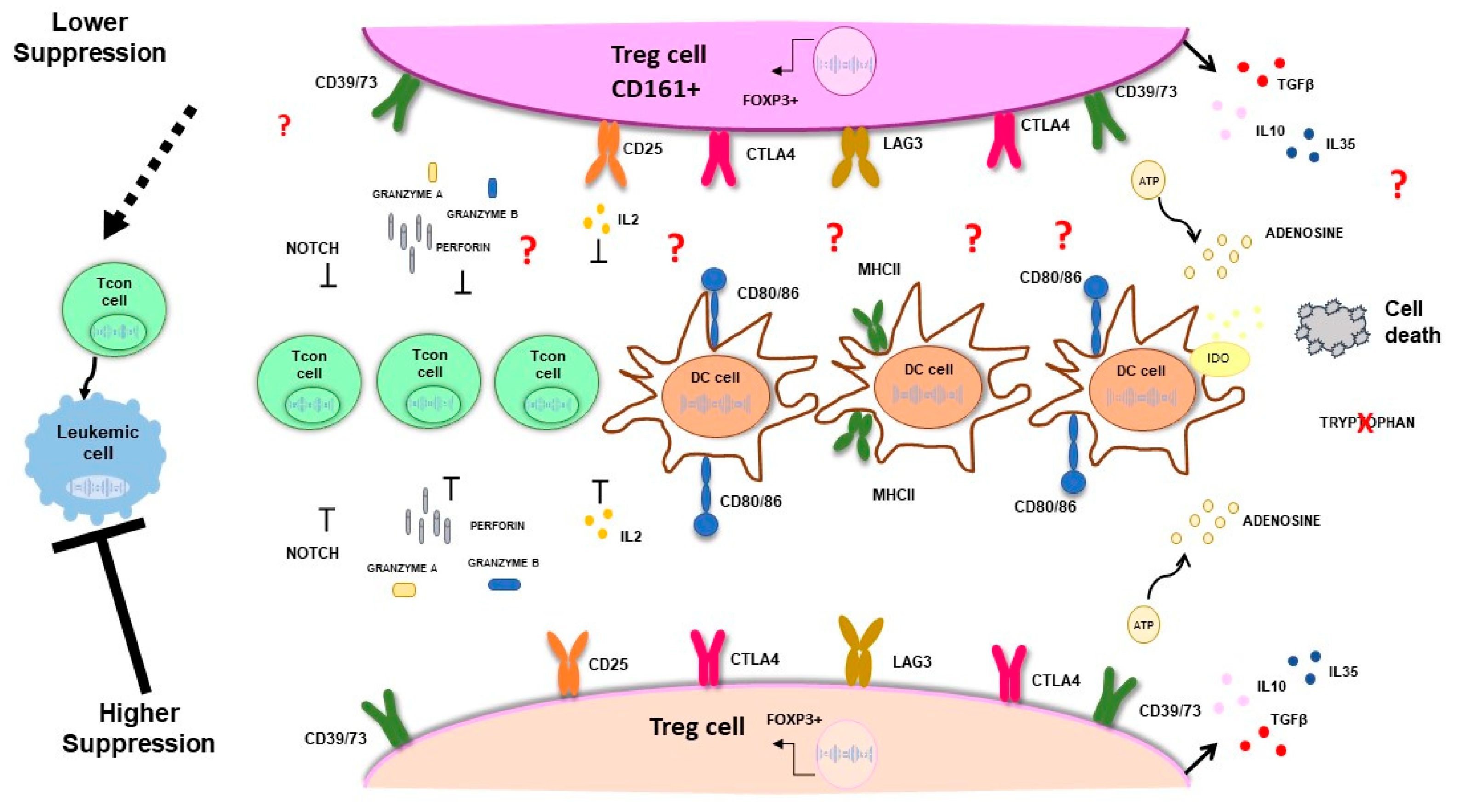

2.2. Tregs Selection

2.3. NK

2.4. Suicide Gene Therapy

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jagasia, M.; Arora, M.; Flowers, M.E.; Chao, N.J.; McCarthy, P.L.; Cutler, C.S.; Urbano-Ispizua, A.; Pavletic, S.Z.; Haagenson, M.D.; Zhang, M.J.; et al. Risk factors for acute GVHD and survival after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 2012, 119, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiser, R.; Blazar, B.R. Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease - Biologic Process, Prevention, and Therapy. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 2167–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiad, Z.; Chojecki, A. Graft versus Leukemia in 2023. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2023, 36, 101476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversa, F.; Tabilio, A.; Velardi, A.; Cunningham, I.; Terenzi, A.; Falzetti, F.; Ruggeri, L.; Barbabietola, G.; Aristei, C.; Latini, P.; et al. Treatment of high-risk acute leukemia with T-cell-depleted stem cells from related donors with one fully mismatched HLA haplotype. N Engl J Med 1998, 339, 1186–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversa, F.; Terenzi, A.; Tabilio, A.; Falzetti, F.; Carotti, A.; Ballanti, S.; Felicini, R.; Falcinelli, F.; Velardi, A.; Ruggeri, L.; et al. Full haplotype-mismatched hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a phase II study in patients with acute leukemia at high risk of relapse. J Clin Oncol 2005, 23, 3447–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.; Karimi, M. Dissecting the regulatory network of transcription factors in T cell phenotype/functioning during GVHD and GVT. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1194984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazar, B.R.; Murphy, W.J.; Abedi, M. Advances in graft-versus-host disease biology and therapy. Nat Rev Immunol 2012, 12, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airoldi, I.; Bertaina, A.; Prigione, I.; Zorzoli, A.; Pagliara, D.; Cocco, C.; Meazza, R.; Loiacono, F.; Lucarelli, B.; Bernardo, M.E.; et al. gammadelta T-cell reconstitution after HLA-haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation depleted of TCR-alphabeta+/CD19+ lymphocytes. Blood 2015, 125, 2349–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godder, K.T.; Henslee-Downey, P.J.; Mehta, J.; Park, B.S.; Chiang, K.Y.; Abhyankar, S.; Lamb, L.S. Long term disease-free survival in acute leukemia patients recovering with increased gammadelta T cells after partially mismatched related donor bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2007, 39, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, L.S., Jr.; Henslee-Downey, P.J.; Parrish, R.S.; Godder, K.; Thompson, J.; Lee, C.; Gee, A.P. Increased frequency of TCR gamma delta + T cells in disease-free survivors following T cell-depleted, partially mismatched, related donor bone marrow transplantation for leukemia. J Hematother 1996, 5, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaleff, S.; Otto, M.; Barfield, R.C.; Leimig, T.; Iyengar, R.; Martin, J.; Holiday, M.; Houston, J.; Geiger, T.; Huppert, V.; et al. A large-scale method for the selective depletion of alphabeta T lymphocytes from PBSC for allogeneic transplantation. Cytotherapy 2007, 9, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handgretinger, R. New approaches to graft engineering for haploidentical bone marrow transplantation. Semin Oncol 2012, 39, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Pira, G.; Malaspina, D.; Girolami, E.; Biagini, S.; Cicchetti, E.; Conflitti, G.; Broglia, M.; Ceccarelli, S.; Lazzaro, S.; Pagliara, D.; et al. Selective Depletion of alphabeta T Cells and B Cells for Human Leukocyte Antigen-Haploidentical Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. A Three-Year Follow-Up of Procedure Efficiency. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016, 22, 2056–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, F.; Pende, D.; Maccario, R.; Mingari, M.C.; Moretta, A.; Moretta, L. Haploidentical hemopoietic stem cell transplantation for the treatment of high-risk leukemias: how NK cells make the difference. Clin Immunol 2009, 133, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretta, L.; Locatelli, F.; Pende, D.; Marcenaro, E.; Mingari, M.C.; Moretta, A. Killer Ig-like receptor-mediated control of natural killer cell alloreactivity in haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2011, 117, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, W.; Iyengar, R.; Turner, V.; Lang, P.; Bader, P.; Conn, P.; Niethammer, D.; Handgretinger, R. Determinants of antileukemia effects of allogeneic NK cells. J Immunol 2004, 172, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muccio, L.; Bertaina, A.; Falco, M.; Pende, D.; Meazza, R.; Lopez-Botet, M.; Moretta, L.; Locatelli, F.; Moretta, A.; Della Chiesa, M. Analysis of memory-like natural killer cells in human cytomegalovirus-infected children undergoing alphabeta+T and B cell-depleted hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematological malignancies. Haematologica 2016, 101, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertaina, A.; Merli, P.; Rutella, S.; Pagliara, D.; Bernardo, M.E.; Masetti, R.; Pende, D.; Falco, M.; Handgretinger, R.; Moretta, F.; et al. HLA-haploidentical stem cell transplantation after removal of alphabeta+ T and B cells in children with nonmalignant disorders. Blood 2014, 124, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, P.; Pagliara, D.; Galaverna, F.; Li Pira, G.; Andreani, M.; Leone, G.; Amodio, D.; Pinto, R.M.; Bertaina, A.; Bertaina, V.; et al. TCRalphabeta/CD19 depleted HSCT from an HLA-haploidentical relative to treat children with different nonmalignant disorders. Blood Adv 2022, 6, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaziev, J.; Isgro, A.; Sodani, P.; Paciaroni, K.; De Angelis, G.; Marziali, M.; Ribersani, M.; Alfieri, C.; Lanti, A.; Galluccio, T.; et al. Haploidentical HSCT for hemoglobinopathies: improved outcomes with TCRalphabeta(+)/CD19(+)-depleted grafts. Blood Adv 2018, 2, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laberko, A.; Sultanova, E.; Gutovskaya, E.; Shipitsina, I.; Shelikhova, L.; Kurnikova, E.; Muzalevskii, Y.; Kazachenok, A.; Pershin, D.; Voronin, K.; et al. Mismatched related vs matched unrelated donors in TCRalphabeta/CD19-depleted HSCT for primary immunodeficiencies. Blood 2019, 134, 1755–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, F.; Merli, P.; Pagliara, D.; Li Pira, G.; Falco, M.; Pende, D.; Rondelli, R.; Lucarelli, B.; Brescia, L.P.; Masetti, R.; et al. Outcome of children with acute leukemia given HLA-haploidentical HSCT after alphabeta T-cell and B-cell depletion. Blood 2017, 130, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschan, M.; Shelikhova, L.; Ilushina, M.; Kurnikova, E.; Boyakova, E.; Balashov, D.; Persiantseva, M.; Skvortsova, Y.; Laberko, A.; Muzalevskii, Y.; et al. TCR-alpha/beta and CD19 depletion and treosulfan-based conditioning regimen in unrelated and haploidentical transplantation in children with acute myeloid leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 2016, 51, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laberko, A.; Bogoyavlenskaya, A.; Shelikhova, L.; Shekhovtsova, Z.; Balashov, D.; Voronin, K.; Kurnikova, E.; Boyakova, E.; Raykina, E.; Brilliantova, V.; et al. Risk Factors for and the Clinical Impact of Cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr Virus Infections in Pediatric Recipients of TCR-alpha/beta- and CD19-Depleted Grafts. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017, 23, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.; Feuchtinger, T.; Teltschik, H.M.; Schwinger, W.; Schlegel, P.; Pfeiffer, M.; Schumm, M.; Lang, A.M.; Lang, B.; Schwarze, C.P.; et al. Improved immune recovery after transplantation of TCRalphabeta/CD19-depleted allografts from haploidentical donors in pediatric patients. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015, 50 (Suppl 2), S6-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Im, H.J.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, N.; Jang, S.; Kwon, S.W.; Park, C.J.; Choi, E.S.; Koh, K.N.; Seo, J.J. Reconstitution of T and NK cells after haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation using alphabeta T cell-depleted grafts and the clinical implication of gammadelta T cells. Clin Transplant 2018, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezioso, L.; Manfra, I.; Bonomini, S.; Schifano, C.; Segreto, R.; Monti, A.; Sammarelli, G.; Todaro, G.; Sassi, M.; Bertaggia, I.; et al. Haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in adults using the alphabetaTCR/CD19-based depletion of G-CSF-mobilized peripheral blood progenitor cells. Bone Marrow Transplant 2019, 54, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynar, L.; Demir, K.; Turak, E.E.; Ozturk, C.P.; Zararsiz, G.; Gonen, Z.B.; Gokahmetoglu, S.; Sivgin, S.; Eser, B.; Koker, Y.; et al. TcRalphabeta-depleted haploidentical transplantation results in adult acute leukemia patients. Hematology 2017, 22, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Witte, M.A.; Janssen, A.; Nijssen, K.; Karaiskaki, F.; Swanenberg, L.; van Rhenen, A.; Admiraal, R.; van der Wagen, L.; Minnema, M.C.; Petersen, E.; et al. alphabeta T-cell graft depletion for allogeneic HSCT in adults with hematological malignancies. Blood Adv 2021, 5, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radestad, E.; Sundin, M.; Torlen, J.; Thunberg, S.; Onfelt, B.; Ljungman, P.; Watz, E.; Mattsson, J.; Uhlin, M. Individualization of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Using Alpha/Beta T-Cell Depletion. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.E.; McNiff, J.; Yan, J.; Doyle, H.; Mamula, M.; Shlomchik, M.J.; Shlomchik, W.D. Memory CD4+ T cells do not induce graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest 2003, 112, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.E.; Tang, A.L.; Wang, Y.; Froicu, M.; Rothstein, D.; McNiff, J.M.; Jain, D.; Demetris, A.J.; Farber, D.L.; Shlomchik, W.D.; et al. Enhancing alloreactivity does not restore GVHD induction but augments skin graft rejection by CD4(+) effector memory T cells. Eur J Immunol 2011, 41, 2782–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Matte-Martone, C.; Zheng, H.; Cui, W.; Venkatesan, S.; Tan, H.S.; McNiff, J.; Demetris, A.J.; Roopenian, D.; Kaech, S.; et al. Memory T cells from minor histocompatibility antigen-vaccinated and virus-immune donors improve GVL and immune reconstitution. Blood 2011, 118, 5965–5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Matte-Martone, C.; Li, H.; Anderson, B.E.; Venketesan, S.; Sheng Tan, H.; Jain, D.; McNiff, J.; Shlomchik, W.D. Effector memory CD4+ T cells mediate graft-versus-leukemia without inducing graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2008, 111, 2476–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschner, D.; Distler, E.; Wehler, D.; Frey, M.; Marandiuc, D.; Langeveld, K.; Theobald, M.; Thomas, S.; Herr, W. Depletion of naive T cells using clinical grade magnetic CD45RA beads: a new approach for GVHD prophylaxis. Bone Marrow Transplant 2014, 49, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleakley, M.; Heimfeld, S.; Loeb, K.R.; Jones, L.A.; Chaney, C.; Seropian, S.; Gooley, T.A.; Sommermeyer, F.; Riddell, S.R.; Shlomchik, W.D. Outcomes of acute leukemia patients transplanted with naive T cell-depleted stem cell grafts. J Clin Invest 2015, 125, 2677–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleakley, M.; Sehgal, A.; Seropian, S.; Biernacki, M.A.; Krakow, E.F.; Dahlberg, A.; Persinger, H.; Hilzinger, B.; Martin, P.J.; Carpenter, P.A.; et al. Naive T-Cell Depletion to Prevent Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease. J Clin Oncol 2022, 40, 1174–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleakley, M.; Otterud, B.E.; Richardt, J.L.; Mollerup, A.D.; Hudecek, M.; Nishida, T.; Chaney, C.N.; Warren, E.H.; Leppert, M.F.; Riddell, S.R. Leukemia-associated minor histocompatibility antigen discovery using T-cell clones isolated by in vitro stimulation of naive CD8+ T cells. Blood 2010, 115, 4923–4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bergen, C.A.; van Luxemburg-Heijs, S.A.; de Wreede, L.C.; Eefting, M.; von dem Borne, P.A.; van Balen, P.; Heemskerk, M.H.; Mulder, A.; Claas, F.H.; Navarrete, M.A.; et al. Selective graft-versus-leukemia depends on magnitude and diversity of the alloreactive T cell response. J Clin Invest 2017, 127, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamcarz, E.; Madden, R.; Qudeimat, A.; Srinivasan, A.; Talleur, A.; Sharma, A.; Suliman, A.; Maron, G.; Sunkara, A.; Kang, G.; et al. Improved survival rate in T-cell depleted haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation over the last 15 years at a single institution. Bone Marrow Transplant 2020, 55, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triplett, B.M.; Shook, D.R.; Eldridge, P.; Li, Y.; Kang, G.; Dallas, M.; Hartford, C.; Srinivasan, A.; Chan, W.K.; Suwannasaen, D.; et al. Rapid memory T-cell reconstitution recapitulating CD45RA-depleted haploidentical transplant graft content in patients with hematologic malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015, 50, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, S.; Talleur, A.C.; Li, Y.; Madden, R.M.; Mamcarz, E.; Qudeimat, A.; Sharma, A.; Srinivasan, A.; Suliman, A.Y.; Epperly, R.; et al. CD45RA-Depleted Haploidentical Transplantation Combined with NK Cell Addback Results in Promising Long-Term Outcomes in Pediatric Patients with High-Risk Hematologic Malignancies. Blood 2021, 138, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisinni, L.; Gasior, M.; de Paz, R.; Querol, S.; Bueno, D.; Fernandez, L.; Marsal, J.; Sastre, A.; Gimeno, R.; Alonso, L.; et al. Unexpected High Incidence of Human Herpesvirus-6 Encephalitis after Naive T Cell-Depleted Graft of Haploidentical Stem Cell Transplantation in Pediatric Patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2018, 24, 2316–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perruccio, K.; Sisinni, L.; Perez-Martinez, A.; Valentin, J.; Capolsini, I.; Massei, M.S.; Caniglia, M.; Cesaro, S. High Incidence of Early Human Herpesvirus-6 Infection in Children Undergoing Haploidentical Manipulated Stem Cell Transplantation for Hematologic Malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2018, 24, 2549–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasior Kabat, M.; Bueno, D.; Sisinni, L.; De Paz, R.; Mozo, Y.; Perona, R.; Arias-Salgado, E.G.; Rosich, B.; Marcos, A.; Romero, A.B.; et al. Selective T-cell depletion targeting CD45RA as a novel approach for HLA-mismatched hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in pediatric nonmalignant hematological diseases. Int J Hematol 2021, 114, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touzot, F.; Neven, B.; Dal-Cortivo, L.; Gabrion, A.; Moshous, D.; Cros, G.; Chomton, M.; Luby, J.M.; Terniaux, B.; Magalon, J.; et al. CD45RA depletion in HLA-mismatched allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for primary combined immunodeficiency: A preliminary study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015, 135, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muffly, L.; Sheehan, K.; Armstrong, R.; Jensen, K.; Tate, K.; Rezvani, A.R.; Miklos, D.; Arai, S.; Shizuru, J.; Johnston, L.; et al. Infusion of donor-derived CD8(+) memory T cells for relapse following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood Adv 2018, 2, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunaikina, M.; Zhekhovtsova, Z.; Shelikhova, L.; Glushkova, S.; Nikolaev, R.; Blagov, S.; Khismatullina, R.; Balashov, D.; Kurnikova, E.; Pershin, D.; et al. Safety and efficacy of the low-dose memory (CD45RA-depleted) donor lymphocyte infusion in recipients of alphabeta T cell-depleted haploidentical grafts: results of a prospective randomized trial in high-risk childhood leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 2021, 56, 1614–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, S.; Madden, R.M.; Mamcarz, E.; Srinivasan, A.; Sharma, A.; Talleur, A.C.; Epperly, R.; Qudeimat, A.; Suliman, A.Y.; Obeng, E.A.; et al. CD45RO+ T-Cell Add Back and Prophylactic Blinatumomab Administration Post Tcrαβ/CD19-Depleted Haploidentical Transplantation in Pediatric Patients with High Risk Acute Leukemia. Blood 2021, 138, 2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagna, L.; Valli, V.; Timofeeva, I.; Capizzuto, R.; Bramanti, S.; Mariotti, J.; De Philippis, C.; Sarina, B.; Mannina, D.; Giordano, L.; et al. Feasibility and Efficacy of CD45RA+ Depleted Donor Lymphocytes Infusion After Haploidentical Transplantation With Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide in Patients With Hematological Malignancies. Transplant Cell Ther 2021, 27, 478.e471–478.e475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maung, K.K.; Chen, B.J.; Barak, I.; Li, Z.; Rizzieri, D.A.; Gasparetto, C.; Sullivan, K.M.; Long, G.D.; Engemann, A.M.; Waters-Pick, B.; et al. Phase I dose escalation study of naive T-cell depleted donor lymphocyte infusion following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2021, 56, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaguchi, S. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory t cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol 2004, 22, 531–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, M.; Takahashi, T.; Sakaguchi, N.; Kuniyasu, Y.; Shimizu, J.; Otsuka, F.; Sakaguchi, S. Thymus and autoimmunity: production of CD25+CD4+ naturally anergic and suppressive T cells as a key function of the thymus in maintaining immunologic self-tolerance. J Immunol 1999, 162, 5317–5326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, L.A.; Mottet, C.; Mason, D.; Powrie, F. Human CD4(+)CD25(+) thymocytes and peripheral T cells have immune suppressive activity in vitro. Eur J Immunol 2001, 31, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baecher-Allan, C.; Brown, J.A.; Freeman, G.J.; Hafler, D.A. CD4+CD25high regulatory cells in human peripheral blood. J Immunol 2001, 167, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ianni, M.; Del Papa, B.; Cecchini, D.; Bonifacio, E.; Moretti, L.; Zei, T.; Ostini, R.I.; Falzetti, F.; Fontana, L.; Tagliapietra, G.; et al. Immunomagnetic isolation of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ natural T regulatory lymphocytes for clinical applications. Clin Exp Immunol 2009, 156, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Ianni, M.; Del Papa, B.; Zei, T.; Iacucci Ostini, R.; Cecchini, D.; Cantelmi, M.G.; Baldoni, S.; Sportoletti, P.; Cavalli, L.; Carotti, A.; et al. T regulatory cell separation for clinical application. Transfus Apher Sci 2012, 47, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, P.; Boeld, T.J.; Eder, R.; Albrecht, J.; Doser, K.; Piseshka, B.; Dada, A.; Niemand, C.; Assenmacher, M.; Orso, E.; et al. Isolation of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells for clinical trials. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2006, 12, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safinia, N.; Vaikunthanathan, T.; Fraser, H.; Thirkell, S.; Lowe, K.; Blackmore, L.; Whitehouse, G.; Martinez-Llordella, M.; Jassem, W.; Sanchez-Fueyo, A.; et al. Successful expansion of functional and stable regulatory T cells for immunotherapy in liver transplantation. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 7563–7577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunstein, C.G.; Fuchs, E.J.; Carter, S.L.; Karanes, C.; Costa, L.J.; Wu, J.; Devine, S.M.; Wingard, J.R.; Aljitawi, O.S.; Cutler, C.S.; et al. Alternative donor transplantation after reduced intensity conditioning: results of parallel phase 2 trials using partially HLA-mismatched related bone marrow or unrelated double umbilical cord blood grafts. Blood 2011, 118, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, S.; Tang, Q.; Sarwal, M.; Laszik, Z.G.; Putnam, A.L.; Lee, K.; Leung, J.; Nguyen, V.; Sigdel, T.; Tavares, E.C.; et al. Polyclonal Regulatory T Cell Therapy for Control of Inflammation in Kidney Transplants. Am J Transplant 2017, 17, 2945–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluestone, J.A.; Buckner, J.H.; Fitch, M.; Gitelman, S.E.; Gupta, S.; Hellerstein, M.K.; Herold, K.C.; Lares, A.; Lee, M.R.; Li, K.; et al. Type 1 diabetes immunotherapy using polyclonal regulatory T cells. Sci Transl Med 2015, 7, 315ra189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Ianni, M.; Falzetti, F.; Carotti, A.; Terenzi, A.; Castellino, F.; Bonifacio, E.; Del Papa, B.; Zei, T.; Ostini, R.I.; Cecchini, D.; et al. Tregs prevent GVHD and promote immune reconstitution in HLA-haploidentical transplantation. Blood 2011, 117, 3921–3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelli, M.F.; Di Ianni, M.; Ruggeri, L.; Falzetti, F.; Carotti, A.; Terenzi, A.; Pierini, A.; Massei, M.S.; Amico, L.; Urbani, E.; et al. HLA-haploidentical transplantation with regulatory and conventional T-cell adoptive immunotherapy prevents acute leukemia relapse. Blood 2014, 124, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierini, A.; Ruggeri, L.; Carotti, A.; Falzetti, F.; Saldi, S.; Terenzi, A.; Zucchetti, C.; Ingrosso, G.; Zei, T.; Iacucci Ostini, R.; et al. Haploidentical age-adapted myeloablative transplant and regulatory and effector T cells for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv 2021, 5, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Zeiser, R.; Dasilva, D.L.; Chang, D.S.; Beilhack, A.; Contag, C.H.; Negrin, R.S. In vivo dynamics of regulatory T-cell trafficking and survival predict effective strategies to control graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic transplantation. Blood 2007, 109, 2649–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignali, D.A.; Collison, L.W.; Workman, C.J. How regulatory T cells work. Nat Rev Immunol 2008, 8, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collison, L.W.; Workman, C.J.; Kuo, T.T.; Boyd, K.; Wang, Y.; Vignali, K.M.; Cross, R.; Sehy, D.; Blumberg, R.S.; Vignali, D.A. The inhibitory cytokine IL-35 contributes to regulatory T-cell function. Nature 2007, 450, 566–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Kitani, A.; Strober, W. Cell contact-dependent immunosuppression by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells is mediated by cell surface-bound transforming growth factor beta. J Exp Med 2001, 194, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, H.A.; Zhu, E.; Terry, A.M.; Guy, T.V.; Koh, W.P.; Tan, S.Y.; Power, C.A.; Bertolino, P.; Lahl, K.; Sparwasser, T.; et al. Selective Treg reconstitution during lymphopenia normalizes DC costimulation and prevents graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest 2015, 125, 3627–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Workman, C.; Lee, J.; Chew, C.; Dale, B.M.; Colonna, L.; Flores, M.; Li, N.; Schweighoffer, E.; Greenberg, S.; et al. Regulatory T cells inhibit dendritic cells by lymphocyte activation gene-3 engagement of MHC class II. J Immunol 2008, 180, 5916–5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Regalado-Magdos, A.D.; Stiggelbout, B.; Lee-Kirsch, M.A.; Lieberman, J. The cytosolic exonuclease TREX1 inhibits the innate immune response to human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Nat Immunol 2010, 11, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borsellino, G.; Kleinewietfeld, M.; Di Mitri, D.; Sternjak, A.; Diamantini, A.; Giometto, R.; Hopner, S.; Centonze, D.; Bernardi, G.; Dell'Acqua, M.L.; et al. Expression of ectonucleotidase CD39 by Foxp3+ Treg cells: hydrolysis of extracellular ATP and immune suppression. Blood 2007, 110, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edinger, M.; Hoffmann, P.; Ermann, J.; Drago, K.; Fathman, C.G.; Strober, S.; Negrin, R.S. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells preserve graft-versus-tumor activity while inhibiting graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation. Nat Med 2003, 9, 1144–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohmeyer, J.K.; Hirai, T.; Turkoz, M.; Buhler, S.; Lopes Ramos, T.; Kohler, N.; Baker, J.; Melotti, A.; Wagner, I.; Pradier, A.; et al. Analysis of the T-cell repertoire and transcriptome identifies mechanisms of regulatory T-cell suppression of GVHD. Blood 2023, 141, 1755–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbar, F.; Villanova, I.; Giancola, R.; Baldoni, S.; Guardalupi, F.; Fabi, B.; Olioso, P.; Capone, A.; Sola, R.; Ciardelli, S.; et al. Clinical-Grade Expanded Regulatory T Cells Are Enriched with Highly Suppressive Cells Producing IL-10, Granzyme B, and IL-35. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2020, 26, 2204–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sandy, A.R.; Wang, J.; Radojcic, V.; Shan, G.T.; Tran, I.T.; Friedman, A.; Kato, K.; He, S.; Cui, S.; et al. Notch signaling is a critical regulator of allogeneic CD4+ T-cell responses mediating graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2011, 117, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hippen, K.L.; Aguilar, E.G.; Rhee, S.Y.; Bolivar-Wagers, S.; Blazar, B.R. Distinct Regulatory and Effector T Cell Metabolic Demands during Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Trends Immunol 2020, 41, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Papa, B.; Pierini, A.; Sportoletti, P.; Baldoni, S.; Cecchini, D.; Rosati, E.; Dorillo, E.; Aureli, P.; Zei, T.; Iacucci Ostini, R.; et al. The NOTCH1/CD39 axis: a Treg trip-switch for GvHD. Leukemia 2016, 30, 1931–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachev, V.; Vanderbeck, A.; Perkey, E.; Furlan, S.N.; McGuckin, C.; Gomez Atria, D.; Gerdemann, U.; Rui, X.; Lane, J.; Hunt, D.J.; et al. Notch signaling drives intestinal graft-versus-host disease in mice and nonhuman primates. Sci Transl Med 2023, 15, eadd1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldoni, S.; Ruggeri, L.; Del Papa, B.; Sorcini, D.; Guardalupi, F.; Ulbar, F.; Marra, A.; Dorillo, E.; Stella, A.; Giancola, R.; et al. NOTCH1 inhibition prevents GvHD and maintains GvL effect in murine models. Bone Marrow Transplant 2021, 56, 2019–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Song, Q.; Yang, S.; Wu, X.; Yang, D.; Marie, I.J.; Qin, H.; Zheng, M.; Nasri, U.; et al. Donor T cell STAT3 deficiency enables tissue PD-L1-dependent prevention of graft-versus-host disease while preserving graft-versus-leukemia activity. J Clin Invest 2023, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radojcic, V.; Pletneva, M.A.; Yen, H.R.; Ivcevic, S.; Panoskaltsis-Mortari, A.; Gilliam, A.C.; Drake, C.G.; Blazar, B.R.; Luznik, L. STAT3 signaling in CD4+ T cells is critical for the pathogenesis of chronic sclerodermatous graft-versus-host disease in a murine model. J Immunol 2010, 184, 764–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurence, A.; Amarnath, S.; Mariotti, J.; Kim, Y.C.; Foley, J.; Eckhaus, M.; O'Shea, J.J.; Fowler, D.H. STAT3 transcription factor promotes instability of nTreg cells and limits generation of iTreg cells during acute murine graft-versus-host disease. Immunity 2012, 37, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, K.; Fernandez, M.R.; Sagatys, E.M.; Reff, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, M.C.; Kiluk, J.V.; Hui, J.Y.C.; McKenna, D., Jr.; Hupp, M.; et al. Metabolic reprogramming augments potency of human pSTAT3-inhibited iTregs to suppress alloreactivity. JCI Insight 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guardalupi, F.; Sorrentino, C.; Corradi, G.; Giancola, R.; Baldoni, S.; Ulbar, F.; Fabi, B.; Andres Ejarque, R.; Timms, J.; Restuccia, F.; et al. A pro-inflammatory environment in bone marrow of Treg transplanted patients matches with graft-versus-leukemia effect. Leukemia 2023, 37, 1572–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, F.; Strober, S.; Leventhal, J.R.; Kawai, T.; Kaufman, D.B.; Levitsky, J.; Sykes, M.; Mas, V.; Wood, K.J.; Bridges, N.; et al. The Fourth International Workshop on Clinical Transplant Tolerance. Am J Transplant 2021, 21, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffin, C.; Vo, L.T.; Bluestone, J.A. T(reg) cell-based therapies: challenges and perspectives. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Neil, A.; Brook, M.; Abdul-Wahab, S.; Hester, J.; Lombardi, G.; Issa, F. A GMP Protocol for the Manufacture of Tregs for Clinical Application. Methods Mol Biol 2023, 2559, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennessy, C.; Deptula, M.; Hester, J.; Issa, F. Barriers to Treg therapy in Europe: From production to regulation. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1090721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lu, W.; Liang, C.L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Qiu, F.; Dai, Z. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) Treg: A Promising Approach to Inducing Immunological Tolerance. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohseni, Y.R.; Tung, S.L.; Dudreuilh, C.; Lechler, R.I.; Fruhwirth, G.O.; Lombardi, G. The Future of Regulatory T Cell Therapy: Promises and Challenges of Implementing CAR Technology. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noyan, F.; Zimmermann, K.; Hardtke-Wolenski, M.; Knoefel, A.; Schulde, E.; Geffers, R.; Hust, M.; Huehn, J.; Galla, M.; Morgan, M.; et al. Prevention of Allograft Rejection by Use of Regulatory T Cells With an MHC-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor. Am J Transplant 2017, 17, 917–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, K.G.; Hoeppli, R.E.; Huang, Q.; Gillies, J.; Luciani, D.S.; Orban, P.C.; Broady, R.; Levings, M.K. Alloantigen-specific regulatory T cells generated with a chimeric antigen receptor. J Clin Invest 2016, 126, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boardman, D.A.; Philippeos, C.; Fruhwirth, G.O.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Hannen, R.F.; Cooper, D.; Marelli-Berg, F.M.; Watt, F.M.; Lechler, R.I.; Maher, J.; et al. Expression of a Chimeric Antigen Receptor Specific for Donor HLA Class I Enhances the Potency of Human Regulatory T Cells in Preventing Human Skin Transplant Rejection. Am J Transplant 2017, 17, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, N.A.; Lamarche, C.; Hoeppli, R.E.; Bergqvist, P.; Fung, V.C.; McIver, E.; Huang, Q.; Gillies, J.; Speck, M.; Orban, P.C.; et al. Systematic testing and specificity mapping of alloantigen-specific chimeric antigen receptors in regulatory T cells. JCI Insight 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ampudia, J.; Chu, D.; Connelly, S.; Ng, C. CD6 Is a Modulator of Treg Differentiation and Activity. Blood 2022, 140, 12653–12654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imura, Y.; Ando, M.; Kondo, T.; Ito, M.; Yoshimura, A. CD19-targeted CAR regulatory T cells suppress B cell pathology without GvHD. JCI Insight 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boroughs, A.C.; Larson, R.C.; Choi, B.D.; Bouffard, A.A.; Riley, L.S.; Schiferle, E.; Kulkarni, A.S.; Cetrulo, C.L.; Ting, D.; Blazar, B.R.; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor costimulation domains modulate human regulatory T cell function. JCI Insight 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, N.A.J.; Rosado-Sanchez, I.; Novakovsky, G.E.; Fung, V.C.W.; Huang, Q.; McIver, E.; Sun, G.; Gillies, J.; Speck, M.; Orban, P.C.; et al. Functional effects of chimeric antigen receptor co-receptor signaling domains in human regulatory T cells. Sci Transl Med 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado-Sanchez, I.; Haque, M.; Salim, K.; Speck, M.; Fung, V.C.; Boardman, D.A.; Mojibian, M.; Raimondi, G.; Levings, M.K. Tregs integrate native and CAR-mediated costimulatory signals for control of allograft rejection. JCI Insight 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koristka, S.; Kegler, A.; Bergmann, R.; Arndt, C.; Feldmann, A.; Albert, S.; Cartellieri, M.; Ehninger, A.; Ehninger, G.; Middeke, J.M.; et al. Engrafting human regulatory T cells with a flexible modular chimeric antigen receptor technology. J Autoimmun 2018, 90, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrien-Elliott, M.M.; Jacobs, M.T.; Fehniger, T.A. Allogeneic natural killer cell therapy. Blood 2023, 141, 856–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupo, K.B.; Matosevic, S. Natural Killer Cells as Allogeneic Effectors in Adoptive Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, I.; Yoon, S.R.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, H.; Jung, S.J.; Jang, Y.J.; Kang, M.; Yeom, Y.I.; Lee, J.L.; Kim, D.Y.; et al. Donor-derived natural killer cells infused after human leukocyte antigen-haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation: a dose-escalation study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014, 20, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krebs, P.; Barnes, M.J.; Lampe, K.; Whitley, K.; Bahjat, K.S.; Beutler, B.; Janssen, E.; Hoebe, K. NK-cell-mediated killing of target cells triggers robust antigen-specific T-cell-mediated and humoral responses. Blood 2009, 113, 6593–6602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamaschi, C.; Bear, J.; Rosati, M.; Beach, R.K.; Alicea, C.; Sowder, R.; Chertova, E.; Rosenberg, S.A.; Felber, B.K.; Pavlakis, G.N. Circulating IL-15 exists as heterodimeric complex with soluble IL-15Ralpha in human and mouse serum. Blood 2012, 120, e1-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.S.; Soignier, Y.; Panoskaltsis-Mortari, A.; McNearney, S.A.; Yun, G.H.; Fautsch, S.K.; McKenna, D.; Le, C.; Defor, T.E.; Burns, L.J.; et al. Successful adoptive transfer and in vivo expansion of human haploidentical NK cells in patients with cancer. Blood 2005, 105, 3051–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.A.; Denman, C.J.; Rondon, G.; Woodworth, G.; Chen, J.; Fisher, T.; Kaur, I.; Fernandez-Vina, M.; Cao, K.; Ciurea, S.; et al. Haploidentical Natural Killer Cells Infused before Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation for Myeloid Malignancies: A Phase I Trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016, 22, 1290–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrien-Elliott, M.M.; Foltz, J.A.; Russler-Germain, D.A.; Neal, C.C.; Tran, J.; Gang, M.; Wong, P.; Fisk, B.; Cubitt, C.C.; Marin, N.D.; et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation donor-derived memory-like NK cells functionally persist after transfer into patients with leukemia. Sci Transl Med 2022, 14, eabm1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrien-Elliott, M.M.; Becker-Hapak, M.; Cashen, A.F.; Jacobs, M.; Wong, P.; Foster, M.; McClain, E.; Desai, S.; Pence, P.; Cooley, S.; et al. Systemic IL-15 promotes allogeneic cell rejection in patients treated with natural killer cell adoptive therapy. Blood 2022, 139, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, A.; Zhang, B.; Dougherty, P.; Luo, X.; Wang, J.; Blazar, B.R.; Miller, J.S.; Cichocki, F. Chronic stimulation drives human NK cell dysfunction and epigenetic reprograming. J Clin Invest 2019, 129, 3770–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denman, C.J.; Senyukov, V.V.; Somanchi, S.S.; Phatarpekar, P.V.; Kopp, L.M.; Johnson, J.L.; Singh, H.; Hurton, L.; Maiti, S.N.; Huls, M.H.; et al. Membrane-bound IL-21 promotes sustained ex vivo proliferation of human natural killer cells. PLoS One 2012, 7, e30264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciurea, S.O.; Schafer, J.R.; Bassett, R.; Denman, C.J.; Cao, K.; Willis, D.; Rondon, G.; Chen, J.; Soebbing, D.; Kaur, I.; et al. Phase 1 clinical trial using mbIL21 ex vivo-expanded donor-derived NK cells after haploidentical transplantation. Blood 2017, 130, 1857–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terren, I.; Orrantia, A.; Astarloa-Pando, G.; Amarilla-Irusta, A.; Zenarruzabeitia, O.; Borrego, F. Cytokine-Induced Memory-Like NK Cells: From the Basics to Clinical Applications. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 884648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.A.; Elliott, J.M.; Keyel, P.A.; Yang, L.; Carrero, J.A.; Yokoyama, W.M. Cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 1915–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romee, R.; Schneider, S.E.; Leong, J.W.; Chase, J.M.; Keppel, C.R.; Sullivan, R.P.; Cooper, M.A.; Fehniger, T.A. Cytokine activation induces human memory-like NK cells. Blood 2012, 120, 4751–4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romee, R.; Rosario, M.; Berrien-Elliott, M.M.; Wagner, J.A.; Jewell, B.A.; Schappe, T.; Leong, J.W.; Abdel-Latif, S.; Schneider, S.E.; Willey, S.; et al. Cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells exhibit enhanced responses against myeloid leukemia. Sci Transl Med 2016, 8, 357ra123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, R.M.; Birch, G.C.; Hu, G.; Vergara Cadavid, J.; Nikiforow, S.; Baginska, J.; Ali, A.K.; Tarannum, M.; Sheffer, M.; Abdulhamid, Y.Z.; et al. Expansion, persistence, and efficacy of donor memory-like NK cells infused for posttransplant relapse. J Clin Invest 2022, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini, C.; Ferrari, G.; Verzeletti, S.; Servida, P.; Zappone, E.; Ruggieri, L.; Ponzoni, M.; Rossini, S.; Mavilio, F.; Traversari, C.; et al. HSV-TK gene transfer into donor lymphocytes for control of allogeneic graft-versus-leukemia. Science 1997, 276, 1719–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciceri, F.; Bonini, C.; Marktel, S.; Zappone, E.; Servida, P.; Bernardi, M.; Pescarollo, A.; Bondanza, A.; Peccatori, J.; Rossini, S.; et al. Antitumor effects of HSV-TK-engineered donor lymphocytes after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation. Blood 2007, 109, 4698–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciceri, F.; Bonini, C.; Stanghellini, M.T.; Bondanza, A.; Traversari, C.; Salomoni, M.; Turchetto, L.; Colombi, S.; Bernardi, M.; Peccatori, J.; et al. Infusion of suicide-gene-engineered donor lymphocytes after family haploidentical haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for leukaemia (the TK007 trial): a non-randomised phase I-II study. Lancet Oncol 2009, 10, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vago, L.; Oliveira, G.; Bondanza, A.; Noviello, M.; Soldati, C.; Ghio, D.; Brigida, I.; Greco, R.; Lupo Stanghellini, M.T.; Peccatori, J.; et al. T-cell suicide gene therapy prompts thymic renewal in adults after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2012, 120, 1820–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Dotti, G.; Krance, R.A.; Martinez, C.A.; Naik, S.; Kamble, R.T.; Durett, A.G.; Dakhova, O.; Savoldo, B.; Di Stasi, A.; et al. Inducible caspase-9 suicide gene controls adverse effects from alloreplete T cells after haploidentical stem cell transplantation. Blood 2015, 125, 4103–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Di Stasi, A.; Tey, S.K.; Krance, R.A.; Martinez, C.; Leung, K.S.; Durett, A.G.; Wu, M.F.; Liu, H.; Leen, A.M.; et al. Long-term outcome after haploidentical stem cell transplant and infusion of T cells expressing the inducible caspase 9 safety transgene. Blood 2014, 123, 3895–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Diagnosis Patient number |

Type of donor | Conditioning | GVHD prophylaxis |

Graft composition | Survival | CI of aGVHD | CI of cGVHD |

| Bertaina A et al. Blood. 2014 | Children with both malignant and nonmalignant diseases (n=23) | haplo | MAC 30%, NMA 70%, according to the original disorder |

ATG (n=23) | CD34+ cells/kg: 15.8 × 106 (range: 10.4 × 106 to 40 × 106) TCR-αβ+CD3+ cells/kg: 4 × 104 (range: 1 × 104 to 9.5 × 104) |

2y TRM 9.3% (SE ±6.1); 2y DFS 91.1% (SE ±6.2); 2y OS 91.1% (SE ±6.2). |

Grade I–II: 13% Grade III–IV: 0% |

18 months: 0% |

| Gaziev J et al. Blood Adv. 2018 | Children with nonmalignant diseases (n=14) | haplo | MAC 100% | CSA + steroids (n=12); CSA + MMF (n=2) |

CD34+ cells/kg: 15.7 × 106 (range: 8.1 × 106 to 39.2 × 106) TCR-αβ+CD3+ cells/kg: 4 × 104 (range: 1 × 104 to 10 × 104) |

5y DFS 69% (95% CI: 37%–87%) 5y OS 84% (95% CI: 49%–96%) |

Grade II–III: 28% (95% CI, 1%–49%) |

extensive cGVHD: 21% (95% CI, 0% to 40%) |

| Laberko A et al. Blood. 2019 | Children with nonmalignant diseases (n=98) | MUD, haplo | MAC 74%, NMA 26%, |

ATG + CSA ± MTX/MMF (n=96) | CD34+ cells/kg: 10.5 × 106 (range: 6.3 × 106 to 14.9 × 106) in haplo TCR-αβ+CD3+ cells/kg: 1.4 × 104 (range: 0.5 × 104 to 13 × 104) in haplo |

5y OS 86% (95% CI: 76%–94%) in MUD; 5y OS 87% (95% CI: 73%–100%) in haplo |

Grade II–IV 17% (95% CI, 10%–28%) in MUD; Grade II–IV 22% (95% CI, 10%–47%) in haplo |

limited cGVHD 9% (95% CI, 4%–19%) in MUD; chronic GVHD 13% (95% CI, 5%–37%) in haplo |

| Locatelli F et al, Blood 2017 | Children with malignant diseases (n=80) | haplo | MAC 100% |

ATG (n=80) | CD34+ cells/kg: 13.9 × 106 (range: 6 × 106 to 40.4 × 106) TCR-αβ+CD3+ cells/kg: 4.7 × 104 (range: 0.2 × 104 to 9.9 × 104) |

5y NRM 5% (95% CI, 2%–13%); 5y DFS 71% (95% CI, 61%–81%); 5y OS 72% (95% CI, 62%–82%) |

Grade I–II 30% | limited cGVHD 5% |

| Maschan M et al. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016 | Children with malignant diseases (n=33) |

MUD, haplo | MAC 100% |

ATG + tacrolimus + MTX (n=21), ATG + tacrolimus (n=5), ATG + MTX (n=2), ATG (n=5) |

CD34+ cells/kg: 9 × 106 (range: 3.8 × 106 to 21 × 106) TCR-αβ+CD3+ cells/kg: 2 × 104 (range: 0.29 × 104 to 12.6 × 104) |

2y TRM 10% (95% CI, 4%–26%); 2y DFS 60% (95% CI, 43%–76%); 2y OS 67% (95% CI, 50%–84%) |

Grade III–IV: 39% (95% CI, 26%–60%) |

cGvHD 30% (95% CI, 18–50)% |

| Prezioso L et al, 2019 | Adult with malignant diseases (n=59) |

haplo | MAC 100% |

ATG (n=59) | CD34+ cells/kg: 11 × 106 (range: 5 × 106 to 19 × 106) TCR-αβ+CD3+ cells/kg: 8.4 × 104 (range: 0.4 × 104 to 62 × 104) |

2y TRM 25%; 2y OS 51% |

Grade II–IV: 17% Grade III–IV: 3% |

limited cGvHD 3% |

| Kaynar L et al. Hematology. 2017 | Adult with malignant diseases (n=34) |

haplo | MAC 100% |

ATG (n=34) | CD34+ cells/kg: 12.7 × 106 (range: 10.3 × 106 to 16 × 106) TCR-αβ+CD3+ cells/kg: 1.8 × 104 (range: 0.7 × 104 to 2.5 × 104) |

2y DFS 33%; 2y OS 36% |

Grade I–IV: 30.3% Grade III–IV: 6.1% |

cGvHD 6.1% |

| de Witte MA et al, Blood Advances 2021 | Adult with malignant diseases (n=35) |

MRD, MUD | MAC 100% |

ATG + MMF (n=35) | CD34+ cells/kg: 6.1 × 106 (range: 2.8 × 106 to 19 × 106) TCR-αβ+CD3+ cells/kg: 2 × 104 (range: 0.0 × 104 to 9.0 × 104) |

2y NRM 32% (95% CI, 17%–48%); 2y DFS 40% (95% CI, 24%–56%); 2y OS 54% (95% CI, 37%–67%) |

Grade II–IV 26% (95% CI, 13%–41%); Grade III–IV 14% (95% CI, 5%–28%) |

2y cGvHD 23% (95% CI, 1%–38%) |

| Author | Diagnosis Patient number |

Conditioning | GVHD prophylaxis |

Graft composition | Survival | CI of aGVHD | CI of cGVHD | ||||||

| Naik S et al Blood 2021 |

Children with hematologic malignancies (n = 72) |

Submyeloablative conditioning |

MMF (n = 61) and/or sirolimus (n = 8) |

Day 0: CD34+ cells/kg: 9.85 × 106 (range: 1.96 × 106 to 44.64 × 106 ) Day +1: CD45RA-depleted graft: CD34+ cells/kg: 5.82 × 106 (range: 0.58 × 106 to 39.43 × 106 ) CD3+ T cells/kg: 60.1 × 106 (range: 16.08 × 106 to 528.43 × 106 ) CD3+CD45RA+ cells/kg: median 0, range 0-0.2 x10 6cells/kg). day+6: NK cells (median: 11.7 x10 6cells/kg; range: 1.65-99.2) |

3-y OS: 68.9% (95%CI: 58.9%– 80.6%) 3-y LFS: 62.2% (95% CI 51.9%– 74.6%) |

Grade II–IV: 36.1% (95% CI: 25.1%– 47.2%) Grade III or IV: 29.2% (95% CI: 19.1%–39.9%) | 3y: 20.8% (95% CI: 12.3%-30.9%) |

||||||

| Sisinni et al. Biology of BMT 2018 |

Children with acute leukemias (n = 25) |

Submyeloablative conditioning | CSA (n= 3), CSA+ MTX (n= 1), MMF (n = 21) |

CD34+ cells/kg: 6.29 × 106 (range: 4.04 × 106 to 18.1 × 106) CD45RA+ cells/kg: 0.6 × 104 (range: 0.2 × 104 to 1 × 104 ) |

30 months OS: 58% | Grade II–IV: 39% Grade III or IV: 33% | 30 months: 22% | ||||||

| Gasior et al. Transfusion 2021 |

Children with hematologic malignancies (n = 17) Severe aplastic anemia (n = 1) | Submyeloablative conditioning | MMF (n = 18) | CD34+ cells/kg: 6.5 × 106 (range: 5 × 106 to 11.2 × 106) CD3+CD45RA+ cells/kg: 3.6 × 104 (range: 0 to 23 × 104 ) Day +7: NK cells/kg: 12.6 × 106 (range: 3.9 × 106 to 100 × 106) |

2yOS: 87.2% (95% CI: 78.6%–95.8%) 2y EFS: 67.3% (95% CI: 53.1%–81.5%) 2-year GRFS: 64% (95% CI: 50.5%–78.1%) | At day +180: Gr III or IV: 34.8% (95% CI: 21.8%–47.8%) | At 1 year: 23.1% (95% CI: 11.4%–34.1%) | ||||||

| Clinical trials and outcomes after CD45RA-depleted Donor Lymphocyte Infusions after haploidentical HCT | |||||||||||||

| Authors | Diagnosis | Transplant platform | Indication, timing,cell dose used | survival | Acute GVHD | Chronic GVHD | |||||||

| Dunkaina et al. BMT 2021 | Children with hematologic malignancies (Total = 143. experimental arm, memory DLI, n = 76; control arm, n = 73 | TCR αβ depletion Myeloablative conditioning Haplo (n = 69) MUD (n = 6) MSD (n = 1) |

Prophylactic - day 0: 25 × 103 cell/kg, day 30,60,90,120 50 ×103 cell/kg Median number of DLI given = 4 (range:1-5) |

2y OS: 79% (95% CI: 69%–88%) 2y EFS: 72% (95% CI: 62%–83%) | Grade II–IV: 14.5% (95% CI:8%–25%) Grade III or IV: 8% (95% CI: 4%– 17%) |

2y: 6% (95% CI: 2%– 16%) | |||||||

| Naik et al. Blood 2021 | Children with acute leukemia (n = 30) |

TCR αβ depletion Submyeloablative conditioning | Prophylactic two weeks following engraftment: DL1: 1 × 105 cells/kg DL2: 1 × 106 cells/kg DL3: 1 × 107 cells/kg |

1y OS: 86.3% (95% CI: 74.6%–99.7%) 1-year EFS: 69.8% (95% CI: 55.2%– 88.4%) |

Grade II–IV: 26.7% (95% CI: 2.4%– 43.3%) Grade III or IV: 13.3% (95% CI: 4.1%–28.1%) | None | |||||||

| Castagna et al. Transplant Cell Ther. 2021 | Adults with hematologic malignancies (n = 19) | Post-transplant cyclophosphamide Myeloablative, reduced-intensity conditioning | Prophylactic DLI of 3 infusions each 4-6 weeks apart First dose given at median of 55 days (range, 46-63) post HCT DL1 5 × 105 cells/kg DL2 1 × 106 cells/kg DL3 5 × 106 cells/kg |

1y OS: 79% (95% CI: 45%–93%) 1y EFS: 75% (95% CI: 46%–90%) |

aGVHD I-IV 6% (95% CI: 0%–17%) | 1y: 15% (95% CI: 0%– 35%). | |||||||

| Author | Diagnosis Patient number |

Type of donor | Conditioning | GVHD prophylaxis |

NK Source and Timing of administration | Survival | CI of aGVHD | CI of cGVHD |

| Choi I et al. (2014) |

Adults with hematological malignancies, mostly AML (n =41) |

haplo | reduced-intensity conditioning |

Cyclosporin alone (n 13); Methotrexate + cyclosporin (n 28) |

Donor-derived NK cells Infusion 2 and 3 weeks after HCT Escalating doses (median dose of 2.0x108/kg) |

31.5 months EFS: 31% OS: 35% (refractory AML) EFS: 0% OS: 0% (refractory ALL/lymphoma) leukemia progression vs historical control cohort (46% vs 74%) |

22% (8 months after HCT) | 24% (3.3 months after HCT) |

| Lee DA et al. (2016) |

Children and adults with high-risk myeloid malignancies (AML, MDS, or CML refractory or beyond first remission)) (n=21) |

MSD: 13 (62%); MUD: 8 (38%) | regimen with busulfan and fludarabine | Thymoglobulin 1.5 mg/kg/day was given on days -3 to -1 (n 21); Tacrolimus started from day -2 and for 3 months; Methotrexate 5 mg/m2 was given on days 1, 2, 6, and 11. |

NK cells from an HLA haploidentical related donor (distinct from transplantation donor) Dose ranging from 0.02 to 8.32 ×106 /kg) Daily infusions for five days after conditioning |

relapse-free survival: 102 days; OS: 233 days; GVH- and Relapse-free: 89 days |

Grade I/II: n 5/21, Grade 3: n 2/21 (10%) |

n 6/21 |

| Ciurea SO et al. (2017) | Adults with high-risk myeloid malignancies (AML, MDS or CML with ≤ 5% bone marrow blasts) (n 13) |

haplo | RIC (melphalan-based) |

cyclophosphamide (50 mg/kg per day on days 13 and 14) + tacrolimus from day 15 and for 6 months + mycophenolate mofetil from day 15 and for 3 months | Membrane-bound IL21 expanded donor NK cells Doses ranging form 1 × 105/kg to to 3 × 1087kg) n 3 infusions before and after haploidentical HSCT (on days −2, +7, and +28). |

1 year OS: 92% 1 year DFS: 85% Relapse rate and overall mortality was not different than in conventional transplants |

Grade I/II: n 7/13 (54%) Grade III-IV: 0 |

0 |

| Berrien Elliot MM et al (2022) |

adult patients with high risk relapsed/refractory AML (n 15) |

haplo | RIC |

tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil starting on day +5 (until days +180 and +35, respectively) |

Same haploidentical donor memory like NK cells. Doses ranging from 0.5 ×106 to 10 × 106 cells/kg Infusion on day + 7 after transplant conditioned with a RIC regimen. Posttransplant cyclophosphamide on days +3 and + 4 IL 15 agonist administered subcutaneously on day +7 and over 3 weeks. |

1 year OS: 29% | grade I: 4/15 grade 2: 6/15 |

All grade:2/15 |

| Shapiro RM et al. (2022) |

relapsed myeloid malignancies relapsed after haploidentical HCT (AML, MDS, MDS/MPN, BPDC) (n 6) |

haplo | RIC | ATG + tacrolimus + MTX (n=21), ATG + tacrolimus (n=5), ATG + MTX (n=2), ATG (n=5) |

Donor-derived memory like NK cells Dose ranging from 5 to 10 million cells/kg Infusion after lymphodepleting chemotherapy Administration of IL2 (n 7 doses) |

All grade: 0 |

All grade: 0 |

| Author | Diagnosis Patient number |

Type of donor | Conditioning | GVHD prophylaxis |

Graft composition | Survival | CI of aGVHD | CI of cGVHD |

| Ciceri F et al., Lancet Oncol 2009 | Adult with malignant diseases (n=50) 22 received TK cells |

haplo | MAC 100% | ATG (n=45) | CD34+ cells/kg: 11.6 × 106 (range: 4.6 × 106 to 16.8 × 106) CD3+ cells/kg: 1 × 104 (range: 0.26 × 104 to 10 × 104) |

3y NRM 49% (95% CI, 17%–63%); 3y OS 49% (95% CI, 25%–73%) |

Grade I-IV 45% (n=10/22) | Extensive cGvHD 4% (n=1/22) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).