Introduction

A fingerprint found at a crime scene is important evidence in a criminal investigation. Fingerprints are collected and compared against an existing database of fingerprint images in the police database. Comparison is made by finding minutiae features [

1,

2] and comparing them to those recorded in the police database. If a match is found, the suspect's identity can be established. While minutiae marking conventionally undergoes automated procedures, occasions may arise necessitating manual interventions, specifically involving the removal and modification of minutiae, owing to the presence of artifacts. Beyond the fact that extraction of minutiae features manually is tedious work and prone to errors, the main disadvantages of this technique are: (1) fingerprints that are not of sufficient value are excluded, and (2) attempts are not made to extract additional information beyond comparison with the database, for example gender, age and other information [

3] . Fingerprints as a gender classification method is an exciting research frontier in forensic science. Research on this topic conducted by Acree in 1999 [

4] focused on analysis of ridge density and ridge width distributions to differentiate between male and female fingerprints. Acree posited that fingerprint ridge density is a reliable parameter for gender determination and observed higher ridge density in females then males. Over 20 years of research conducted and covered in the latest literature review from 2021 [

5] concluded that the number of ridges present on a fingerprint per unit area varies between individuals and shows differences based on gender. However, the mean density of fingerprint ridges varies

between populations, as demonstrated by the different datasets investigated in various studies. Moreover, a study titled "What can a single tell about gender?", published in [

6], employed image processing techniques, specifically focusing on minutiae detection and extracting image features centered around this point of interest. However, with 65% accuracy in classifying gender, this study demonstrates a moderately favorable outcome

Alternative approaches to gender classification based on fingerprint ridges use advanced machine learning and deep learning methods based on the whole fingerprint image. In [

7] the authors introduce an approach that leverages Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), Principal Component Analysis (PCA) features, and min-max normalization. The models are trained utilizing a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier and incorporate sampling techniques such as SOMAT to address dataset imbalance. In this study the right ring finger emerged as the most suitable point of interest for gender identification. It achieves an accuracy rate of 75% and 91% for males and females, respectively. The study refrained from employing deep learning methodologies and relied on a single dataset. Another article [

8] presents 99% accuracy, however, the article does not provide references or specifics regarding the precision of the train-test division when considering the occurrence of two impressions for each fingerprint and the gender balance, resulting in uncertainty regarding those results.

One of the most common publicly available databases for gender classification is SOCOfing. In [

9] gender classification performance was evaluated using single finger-based classification, resulting in 77% average accuracy. Remarkably, when employing a weighted approach that considered multiple fingers simultaneously, accuracy significantly improved, achieving a 90% accuracy rate. However, a gender classification based on multiple fingerprints is theoretical. According to our knowledge, it has no practical application in crime scene investigation. This is primarily due to the rarity of encountering more than one fingerprint at a crime scene, as supported by prior research [

10]. In this study the authors employed only an elementary 5-layer CNN [

11] architecture. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the network was trained "from scratch," without the use of any beneficial fine-tuning techniques. Another study conducted on the SOCOfing dataset [

12], reported an accuracy rate of 90% on a restricted subset comprising 2000 fingerprints out of the total 6000 fingerprints available in the SOCOfing database. Notably, there is limited clarity regarding the specific criteria employed to select the 2000 fingerprints from the larger pool of 6000. In summary, research articles focusing on the SOCOfing database have reported gender classification outcomes of approximately 75% when employing neural network-based approaches. When multiple fingerprints are used (though not practically applicable), accuracy rates as high as 90% were observed. Hence, it is evident that a baseline accuracy of around 75% is commonly encountered in gender classification tasks conducted on the SOCOfing dataset. This is indicated by references such as [

13] and others.

In the context of studies utilizing advanced techniques on private fingerprint datasets, a recent comprehensive publication [

14] conducted an extensive comparative analysis. This analysis encompassed nine widely employed classifiers, including CNN, Support Vector Machine (SVM) with three distinct kernels, k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN), Adaboost, J48, ID3, and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA). Their methodology involved gender classification based on various fingerprint features, among them ridge-density, ridges, minutiae, and fingertip-size (FTS). The results revealed that CNN achieved the highest success rate for gender classification in this context. The results showed an accuracy of 95%. However, it is important to note that these results were based on private, high-quality fingerprint images collected in controlled laboratory settings (e.g., 500 dpi resolution with each finger scanned three times to ensure image quality), which may not be representative of real-world crime scene scenarios. Moreover, a somewhat redundant methodology that uses CNN for classification was utilized when it is essentially a method for extracting features.

The Data-Centric Artificial Intelligence (DCAI) approach shifts the AI paradigm by placing more emphasis on data rather than algorithms or models [

15,

16]. Instead of solely concentrating on the model or algorithm itself, this approach analyzes data to identify which parameters instances have the most significant impact on classification. It then re-trains models based on these influential instances. In recent years, this method has proven to offer distinct advantages over traditional approaches. DCAI represents an alternative paradigm in artificial intelligence that prioritizes data over algorithms. By implementing a set of margin-based criterion, we effectively filter out uncertain classification, and as mentioned, enabling the model to learn from more reliable and informative examples. This approach has demonstrated the efficacy of the margin of confidence clean method in improving the performance and generalization capabilities of deep learning models.

To conclude, this study's primary contributions encompass several key aspects:

Assess the performance of a singular CNN methodology across a diverse range of datasets, public and private, free of prior assumptions or preprocessing steps.

Classification in scenarios of partially or low-quality fingerprint images by identification and delineation of the Region Of Interest (ROI) that most contributes to gender classification.

Improved classification results using DCAI approaches.

Datasets

In this paper we evaluate four datasets as detailed in

Table 1. Three of these datasets are publicly accessible, namely: (1) NIST-DB4 [

17], (2) SOCOfing [

18], and (3) NIST-302 [

19]. Additionally, we incorporated a privately obtained dataset from the Israeli police, henceforth referred to as IsrPoliceDB. To the best of our knowledge, these datasets represent the only publicly available resources that include gender information in conjunction with fingerprint images. The NIST-DB4 dataset [

20] comprises 4000 plain fingerprints, captured at a resolution of 500 dpi, sourced from 2000 individuals (380 females and 1620 males), where each subject contributed two impressions of their index finger for this dataset. The SOCOfing database [

18], established in 2007, consists of 6000 fingerprints collected from 600 African subjects (123 females and 477 males). Each participant provided a single impression of all ten fingers. The images in this dataset measuring 96 x 103 pixels and having a resolution of 500 dpi. Furthermore, a relatively recent dataset, NIST-302 [

21], published by the NIST agency in 2019, includes fingerprint impressions from 200 Americans (132 females and 68 males). Each individual contributed 20 impressions of all ten fingers. The the images in this dataset are at a resolution of 500 dpi, with dimensions of 256 x 360 pixels

Results

The results section is divided into three parts. In the first part we outline the process of selecting the optimal CNN for classifying gender using fingerprint images. This part also includes a thorough evaluation of the network's performance across all four databases, ensuring a comprehensive assessment. In the second part, the most influential fingerprint region that contributes significantly to gender classification was identified and evaluated. In the final part we explore several DCAI strategies aimed at enhancing gender classification accuracy. These strategies are designed to refine and optimize our gender classification models, leading to more robust and reliable classifications.

Part I -

Identification of the most suitable network for gender classification: To achieve this, the NITS-302 dataset was used as a basis for evaluating five variants of the two most widely employed CNN architectures (VGG and ResNet). NIST-302 was chosen for this evaluation due to its extensiveness and relatively high image quality, as well as its comprehensive coverage by including images of all 10 fingerprints. We used pre-trained ImageNet networks, at a learning rate of 0.0001, a batch size of 32, and an AdaGrad optimizer to train the selected models.

Table 2 shows ResNet18 exhibited overfitting issues and produced suboptimal results. Compared to ResNet, VGG16 and VGG19 achieved a test accuracy of 0.83, which is notably higher than ResNet's 0.75. It appears that VGG19 optimizes the trade-off between model complexity and generalization of unknown data; this is evident when focusing on the balance between train and test accuracy. Furthermore, the F-score, which represents a consolidated view of model performance based on precision and recall, encourages VGG models. Specifically, VGG19 achieved the highest test accuracy and F-scores of 0.84 and 0.81 respectively.

Next, the selected VGG19 model was evaluated across the four databases we used, one internal and three public.

As can be seen in

Table 3, the VGG19 network can be generalized to other datasets, as the classification results range from 70 to 95% with no evidence of overfitting. The results are correlated with the size and quality of the images in the dataset, as indicated in

Table 1. IsrPoliceDB yielded the highest classification accuracy rate of 96%, in accordance with the dataset having the largest image size and resolution. A moderately sized image and resolution in the NIST datasets (DB4, 302) achieved an accuracy rate of 80%, while a considerably smaller image achieved an accuracy rate of 68%. The results indicate that the VGG network is capable of capturing positive samples effectively, while minimizing false positives reliably and stable.

Part II-

Next, we will present the outcomes of the second part of our study. This centered on identifying and assessing the critical fingerprint image region essential for gender classification, especially in scenarios involving partially or low-quality fingerprint images. Our approach involves the identification and delineation of the ROI in fingerprint images, aiming to pinpoint the areas that significantly influence gender classification.

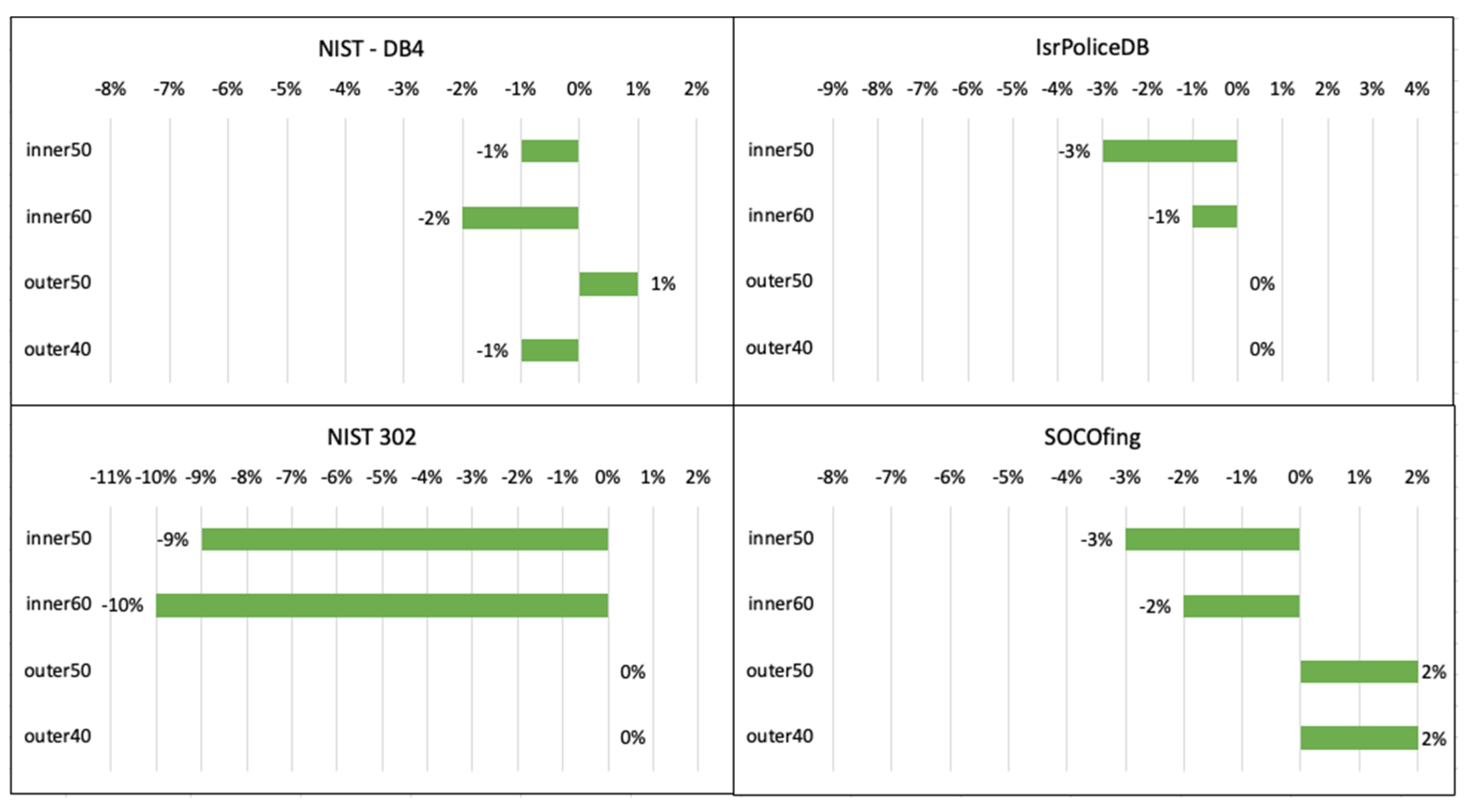

As can be seen in

Figure 2, a 4% decrease is seen when classification is based on the inner region of the fingerprint. In contrast, when classifying based on the outer region, accuracy is usually not affected, with one exception, in the NIST-DB4, which showed a 1% drop/decrease; all other cases either improved or remained unchanged. The results indicate that the outer region of a fingerprint is more significant for gender classification, which is in accordance with previous literature findings. It is further supported by the absence of "delta" elements and additional features in the outer region that do not interfere with "ridge counting."

Part III-

Lastly, we will examine the DCAI strategies to improve the results. As discussed in the methods section, DCAI is a paradigm shift in artificial intelligence that focuses on data as the primary source of information. We examined five DCAI approaches: cleanlab-OOD, FLIP (Easy and Hard), and MOC (Easy and Hard). For each of the five approaches, we scored every instance in the training set and filtered out the highest 5% of instances in the dataset. Subsequently, we re-trained each model using the resulting clean dataset. The newly trained model was then evaluated on the original test-set.

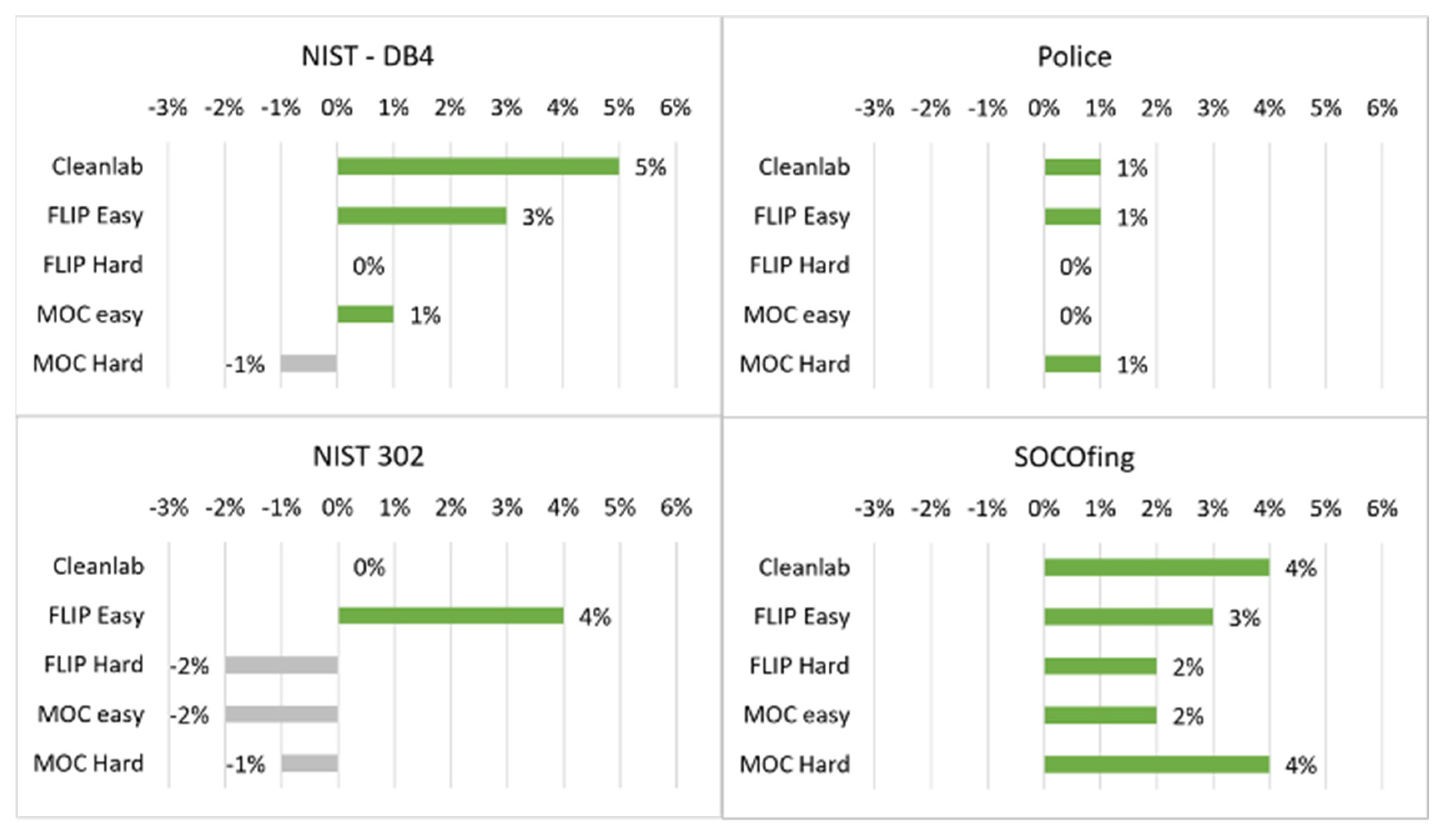

As evident from

Figure 3, Two out of the five approaches, cleanlab-OOD and FLIP-Easy, showed consistent improvements, with an average F-score improvement of 2.5% and 2.75%, respectively. The cleanlab-OOD approach improved the F-score across the four datasets, except for the NIST-302 dataset where the values were equal to the baseline. The most significant improvement was observed for the NIST-DB4 dataset, where the F-score increased from 0.82 to 0.87 (see supplemental table). FLIP-Easy approaches showed noticeable improvements on the NIST-DB4 and NIST-302 datasets. These findings provide compelling evidence of the successful filtering capability of DCAI approaches, effectively eliminating the data that negatively impacted the model's performance.

Discussion

This paper demonstrate a comprehensive evaluation of fingerprint images gender classification using CNN. The study is divided into three main parts: selection of an optimal CNN for gender classification based on the given datasets, identification of critical fingerprint regions for classification, and exploration of Data Cleaning and Augmentation for Improvement (DCAI) strategies to enhance classification accuracy. This discussion section delves into the implications of these findings and their significance for biometric gender classification.

The results indicate that VGG19 outperforms other architectures in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F-score. It achieved a test accuracy of 0.84, highlighting its ability to balance model complexity and generalization. These findings emphasize VGG19's superiority in accurately classifying gender based on fingerprint images. VGG19's successful application is further demonstrated when it is tested across different datasets, including the IsrPoliceDB and three public databases (

Table 3). The classification results range from 70% to 95%, showing its ability to generalize across various datasets without overfitting. The results are correlated with the size and quality of the images in the dataset. This indicates that VGG19 effectively captures positive samples while minimizing false positives. In order to apply gender classification in a practical manner in a variety of real-world scenarios, this ability to generalize across diverse datasets is vital. The value of fingerprint evidence in detecting crime is worth consideration when analyzing smaller datasets. As a result of their less complex architecture and shallower depth, pre-trained VGG models may perform better, mitigating overfitting, which is particularly advantageous for smaller databases.

The second part of the study focused on identifying and assessing the critical fingerprint region that significantly influences gender classification (

Figure 2). It becomes evident that the outer region holds greater importance in gender classification. This conclusion is in harmony with existing literature and underpinned by the distinct absence of disruptive elements within the outer region. The methodology employed in this study to define the ROI)in fingerprint images yields valuable insights for researchers and practitioners dealing with partially or low-quality fingerprint images.

The third part of the study explored Data-Centric AI (DCAI) strategies aimed at further enhancing classification accuracy (

Figure 3). Among the five DCAI approaches examined, cleanlab-OOD and FLIP-Easy consistently demonstrated improvement in F-scores, with an average increase of 2.5% and 2.75%, respectively. FLIP-Easy shoes the optimal approach for several reasons. First, by eliminating 5% of the data with the most inconsistent classifications during training, it ensures that the model focuses primarily on data where the classifications are stable. This enhances the model's generalization. By applying this strategy, overfitting is reduced, model reliability is improved, and independent data can be accurately predicted more accurately. Second, it helps in building a leaner, more resource-efficient model. Data points with fluctuating classifications can slow down the learning process by causing the model to repeatedly adjust its parameters to correct perceived errors. By removing these unstable elements, the model can train faster and use computational resources more efficiently. Lastly, the FLIP-Easy approach encourages a focus on high-quality data. In machine learning algorithms, the quality of the training data is crucial. By removing volatile data, this approach ensures that the model draws its lessons from the most consistent, reliable sources of data. This can result in improved overall performance. To conclude, FLIP-Easy provides the highest performance for constructing a more generalizable, efficient, and higher-performing model.