1. Introduction

One of the medicinal plants that grows in Indonesia is the Sungkai plant (

Peronema canescens Jack).

Peronema canescens Jack (P. canescens) in Jambi Province is ethnobotanically used for various therapies such as antidemam, antioxidan, and immunostimulant [

1]. This plant is traditionally used by the community in medicine or health care, such as bruising medicine, fever medicine, cold medicine, worming medicine, and mouthwash [

2].

P. canescens contains bioactive compounds that play as antidiaberics [

3], antihyperurisemia [

4], anti-inflammatory [

5], potential anticancer [

6], and immunostimulant [

7]. Other studies mention that

P. canescens has potential bioactivity as an antibacterial and antioxidant. This potential is related to the content of secondary metabolite compounds possessed by

P. canescens plants, such as alkaloids, terpenoids, phenolics, flavonoids, tannins, and saponins [

5].

However, bioactive compounds in extracts that are still in liquid form have several disadvantages, such as a high organoleptic impact due to the bitter and sour taste of some compounds, low solubility, a tendency to oxidize, and a limited shelf life, reducing the utilization of bioactive compounds [

8]. Therefore, some kind of processing or delivering system as an alternative is needed that can overcome this problem, to ensure their effectiveness and target function. Encapsulation is an effective method that improves the phytochemical stability by entrapping the core material with the coating agent [

9].

Albeit, he application of encapsulation technology continues to experience developments, such as nanoencapsulation and microencapsulation. Microencapsulation is one of the methods used to protect active substances, improve their physico-chemical properties, and protect them from unpleasant flavors and aromas or adverse environmental conditions [

10]. The extrusion method is one of the most popular and simple methods in microencapsulation technology. The advantages of this method compared to other methods are that it is easy to perform, does not require high temperatures, has gentle formulation conditions that ensure higher cell viability, does not use harmful solvents, and can be performed under aerobic and anaerobic conditions [

11].

Biopolymers are oftentimes as coating materials for microencapsulation of various bioactive compounds because they have attractive physico-chemical properties [

12]. The selection of a coating material that can avoid compositional changes due to damage to the bioactive compounds in the extract is a crucial point for the success of the microencapsulation process [

13]. Coating materials such as inulin, maltodextrin, and Arabic gum are recognized as safe and have been used for the stability of bioactive compounds [

14]. Maltodextrin is a polysaccharide class compound consisting of β-D-glucose units obtained by acid or enzyme hydrolysis of some starches (corn, rice, potato, starch, or wheat). Maltodextrin has high solubility in water, has a neutral taste, is colorless, has low viscosity, and is easily obtained [

15]. Inulin is a polymer of fructose units linked by a terminal glucose unit at the end of the chain. Inulin has activity as an anticytotoxic and immunomodulator. In addition, inulin also behaves as a prebiotic and stimulates the activity of beneficial microflora in the colon. Since its release only occurs in the gut, inulin can be used to protect bioactive compounds in extracts that are susceptible to degradation along the human digestive tract [

15,

16,

17]. Arabic gum is a complex heteropolysaccharide composed of D-glucuronic acid, L-rhamnose, D-galactose, and L-arabinose, including about 2% protein. Arabic gum is often used as a dressing in microencapsulation technology because it has good emulsification properties, high solubility, and low viscosity in aqueous solutions. In addition, it provides good retention of volatile substances and effective protection against oxidation [

15]. These three biopolymers were chosen to be used as coating materials in this microencapsulation study of an ethanol extract of

P. canescens leaves extract due to their functional properties. The purpose of this study was to determine the best microencapsulation formulation using maltodextrin, inulin, and Arabic gum

3. Discussion

The encapsulation is known as one of the most widely used techniques to protect bioactive compounds from various environmental factors and even helps to increase the efficiency of drug delivery systems effectively [

30], moisture, and light; hence, it can extend the shelf life of the product and avoid damage [

24,

30]. The process of forming encapsulation methods on the scale of microparticles proved to be more effective and efficient, especially in drug doses and the reaction speed in reaching the target cell. One of the factors that influence encapsulation technology is the type and ratio of coating material, concentration and structure of the active substances, emulsion properties, and drying process variables, which are important factors to be considered in the encapsulated powder's physical and chemical properties [

31].

Arabic gum belongs to a protein coating material that has good layer-forming, binding, and emulsifying properties that boost yield [

32]. Maltodextrin has a low surface activity, which leads to a subpar microencapsulation procedure [

33]. Treatment of variations in a carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) concentration showed a decrease in per cent yield with each increase in CMC concentration. The increase in CMC content causes the diffusivity of water (the ability of water to move) to decrease so that the efficiency of extract coating decreases.

Treatment of the type of coating material showed that the encapsulation efficiency with gum arabic coating material was greater than that of maltodextrin, even inulin coating material. The type of coating material greatly influences the efficiency of the encapsulation process. Gum arabic is a coating material because it has good emulsifying properties and can form a layer/film [

34]. The good emulsifying properties of gum arabic are due to its protein content. Gum arabic is a better coating material than maltodextrin in the microencapsulation process of cardamom oleoresin [

35].

A

1 with Arabic gum dressing material had a maximum microencapsulant solubility percent in water of 98.95%, whereas sample M

1 with maltodextrin dressing material had a maximum of 99.38%. According to previous studies, the higher the maltodextrin concentration, the higher the solubility value [

36]. This happens because maltodextrin has the property of being able to bind hydrophobic substances. Besides, maltodextrin is a polysaccharide soluble in water to form a uniformly dispersed solution. The hydroxyl groups in maltodextrin will interact with water when the material is dissolved. The added maltodextrin can bind water in the material and maintain the water content so that a large amount of maltodextrin added will affect the yield. The increase in yield, along with the proportion of maltodextrin, indicates that maltodextrin has a better ability to coat extracts, in this case, the ability to form emulsions, film formation, and flexibility in coating extracts [

27,

37,

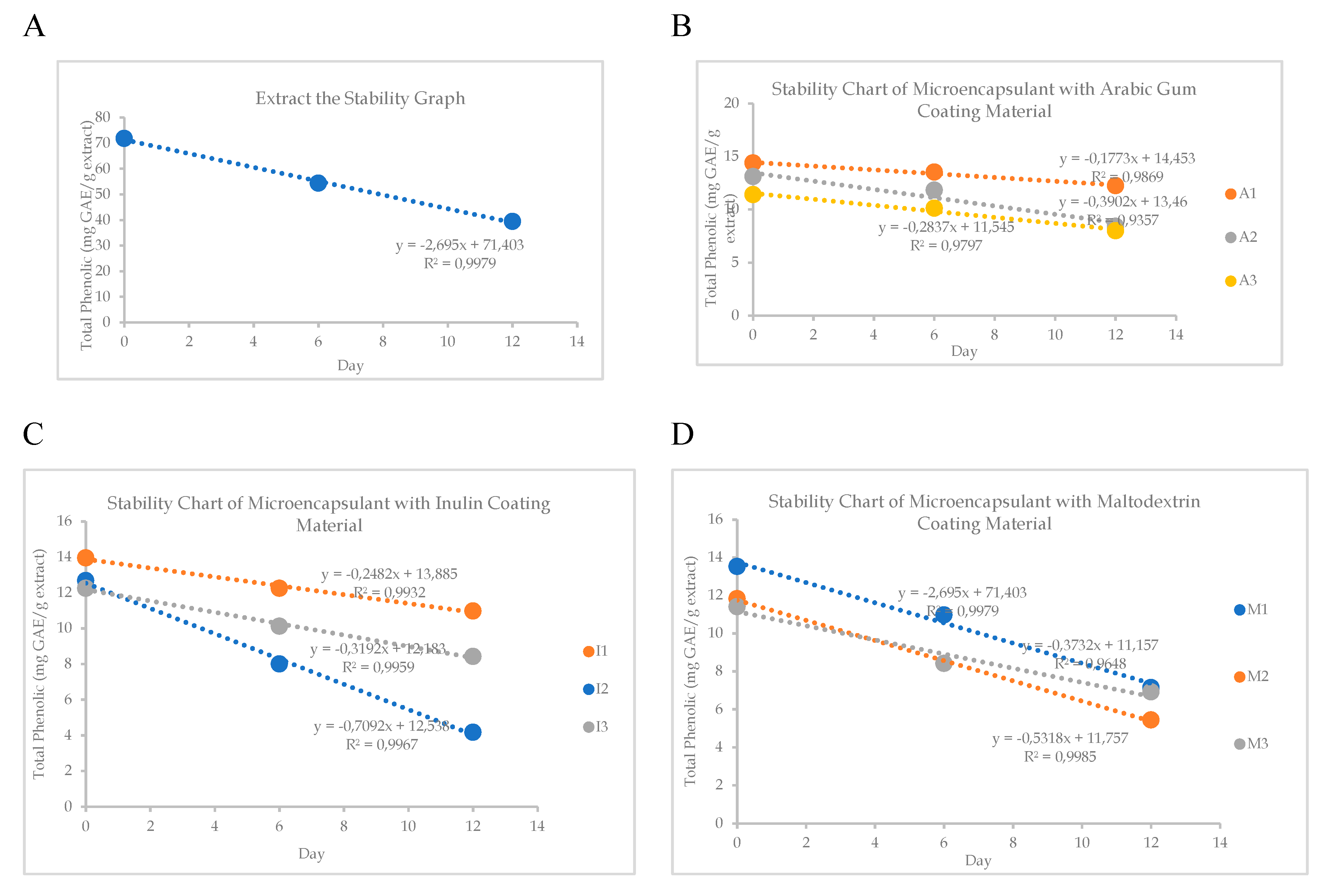

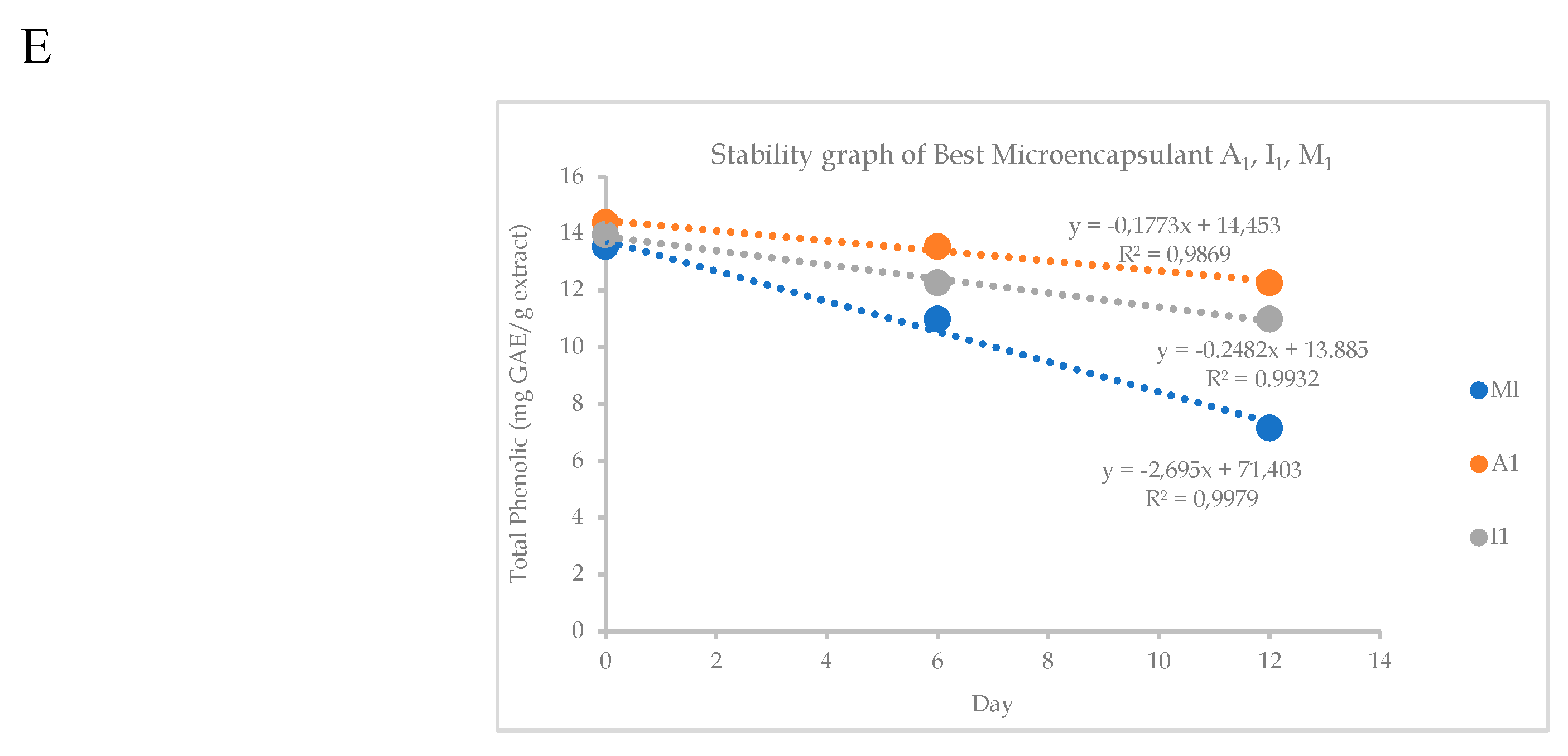

38].A1 microencapsulant has the highest stability and a percentage decrease in total phenolic content ranging from 0.1773% to 0.1773% per time unit, is known from this investigation. When compared to other microencapsulants, microencapsulant A1 is the most effective at protecting phenolic chemicals. This is because microencapsulants with good oxidation protection are created when 90% Arabic gum and 10% CMC are combined. Previous studies claimed that by raising viscosity, thickening agents can improve the stability of the coating substance. However, if thickening agents are added in excess, the extract will not be adequately covered, allowing for fast destruction due to inadequate protection [

23].

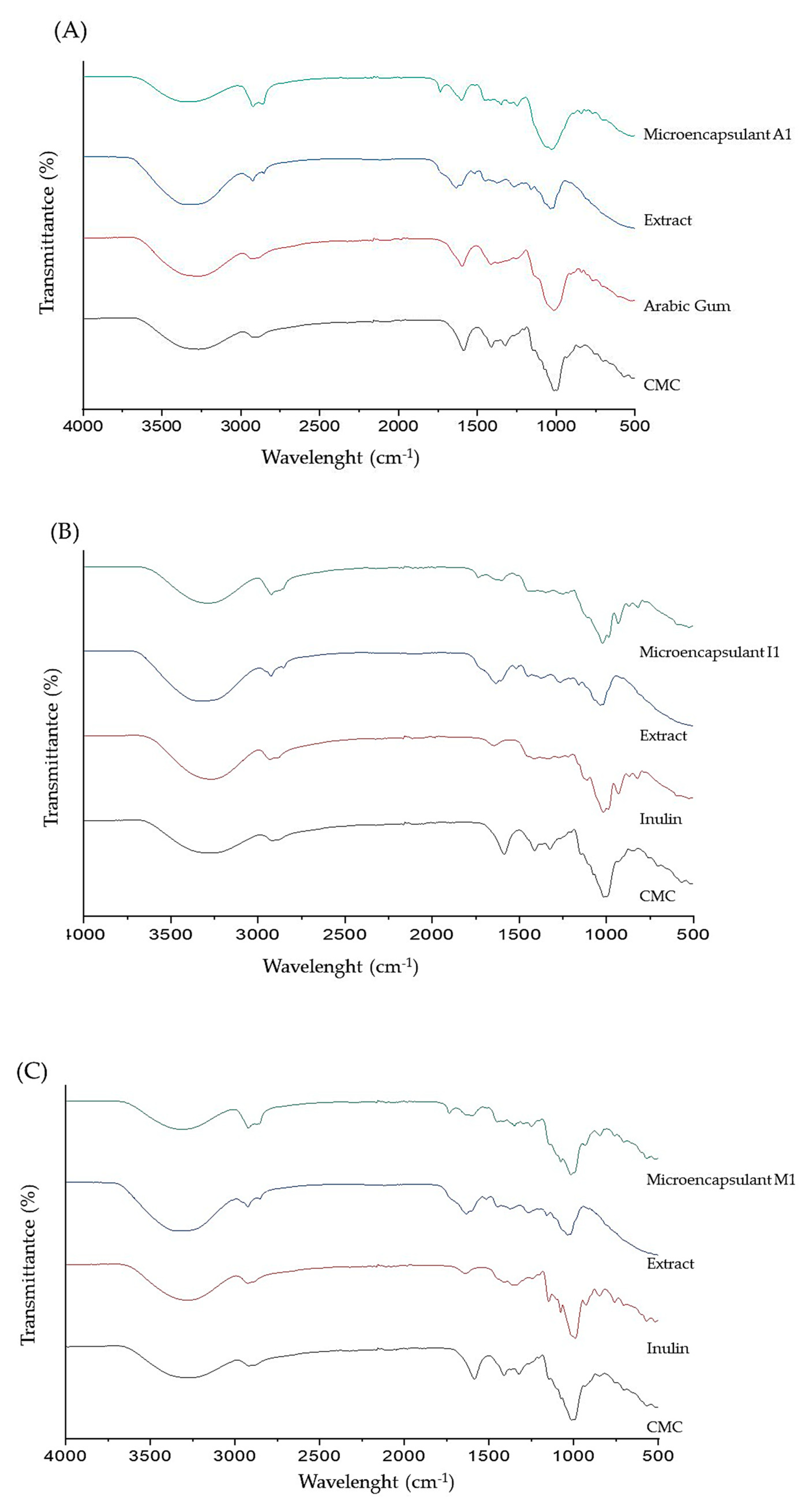

The FTIR spectrum shows a wide absorption band at wave numbers 3200-3600 cm

-1 which indicates a loosening of the O-H (hydroxyl) and wave numbers at 2850-2970 and 1340-14700 cm

-1 indicate stretching the C-H bond. The encapsulation formulation and the coating material have almost the same spectrum, the peak appearing at a wavelength of 675-995 cm

-1, which indicates the presence of the C-H Alkene functional group, which usually appears at a wavelength of 675-995 cm

-1. The FT-IR spectra of Tween-80 showed a major band of C-H at 675-995 cm

-1, and the transmittance value decreased in the encapsulation results. Meanwhile, the major band in maltodextrin at 1050-1300 cm

-1 C-O stretching, the same band appears in all encapsulates; this is the same as previous research [

39]. Theoretically, the occurrence of a cross-linking reaction between Ca

2+ and maltodextrin affects the intensity of the asymmetry, and symmetry COO- stretching was observed at 1594 cm

-1, and a weak symmetric peak was presented at 1400–1500cm

-1 Also a peak appearing at a wavelength of 1733 cm

-1 indicates the presence of the C=O Aldehid/ketone/carboxylic acid/ester functional group, which usually appears at a wavelength of 1690-1760 cm

-1. The results of the comparison of the FT-IR spectra between the coating and the encapsulation results show that an encapsulation is formed, and it can be seen that all the spectra present in the encapsulation material appear on the encapsulation.

It is shown that antioxidant test results of an ethanol extract of

P. canescens leaves that have been microencapsulated have IC

50 values ranging from 121.176–139.503 mg/L. Microencapsulant A1 has the highest IC

50 value compared to other microencapsulants. The antioxidant activity test results of each microcapsulant can be attributed to the amount of secondary metabolite compound content in the extract. Based on

Table 6, it is known that A1 microencapsulant encapsulates more phenolic compounds contained in the extract. Antioxidant activity is influenced by total phenolic, which is a compound that can donate many hydrogen atoms to neutralize DPPH radicals.

Maltodextrin is stable against oxidising compounds but has poor emulsification capacity and stability and low oil retention. Maltodextrin can also reduce viscosity and has the property to prevent oxidation so that the antioxidants will be well enveloped [

22,

40]. The concentration of the dressing also plays an important role in the encapsulation process. Too high amount of dressing makes the emulsion dense, which makes the atomisation process difficult. The too-high dressing also causes puffing or ballooning and particle cracking. At a certain concentration of maltodextrin addition, the antioxidant quality and the ability to capture free radicals will be better [

41].

The treatment of dressing type showed that gum arabic had greater antioxidant activity than maltodextrin. The use of maltodextrin dressing has high oxidation resistance properties. It can reduce the viscosity of the emulsion combined with other dressings with better emulsifying properties that cause antioxidants in the encapsulate to be enveloped and well protected [

42].

Gum arabic binder has better emulsifying properties than maltodextrin. Antioxidant activity is also influenced by the properties of gum arabic binder, which can form texture, form film, bind and emulsify well so that gum arabic can maintain the core material of the product because the gum arabic binder can form a layer that can protect the core material from the process of destructive changes [

12,

43,

44]. The antioxidant activity of the encapsulate is related to the total phenol content. A high total phenol content of the encapsulate will result in high antioxidant activity as well. Hence, the ability of the antioxidant to donate electrons in terms of suppressing the development of free radicals is also higher. Protection using the encapsulation process can prevent degradation due to light or oxygen radiation and slow evaporation, then will minimise the loss of antioxidants due to oxidation [

45]

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

The main material used in this study was Sungkai leaves (Peronema canescens Jack.) obtained from Pamuatan Village, Kupitan District, Sijunjung Regency, West Sumatra Province, Indonesia. Other materials used were FeCl3, 2N sulfuric acid, Dragendorff reagent, Lieberman-Burchard reagent, HCl, Mg powder, HCl, tween-80, distilled water, maltodextrin (Lihua Starch), CMC (Sigma), Inulin (Pep'D), Arabic gum (Orlife), CaCl2 (Pudak Scientific), Glutaraldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich), Gallic acid (Sigma), Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, Na2CO3 (Emsure®), Ascorbic acid (Emsure®), methanol p. a (Emsure®), DPPH (Sigma-Aldrich), The equipment used in this research is glassware (Pyrex®), Fourier-Transform infrared spectroscopy (Alpha II-Bruker), a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo-Fischer), and a SEM-EDX JEOL JSM-6510LA.

4.2. Preparation and Extraction

Sungkai leaves are selected in good condition, wet sorted, then washed to separate the test material from dirt, and dried for 7 days [

46]. Furthermore, the simplisia was pulverized using a grinder and obtained 2,500g of simplisia powder, and the yield obtained was 10%. The extraction process of

P. canescens leaves was carried out by maceration using 96% ethanol solvent at 37°C to prevent damage to compounds contained in Sungkai leaves, such as phenolics. The process of separating extracts and solvents is carried out using a vacuum rotary evaporator at temperatures below the boiling point of the solvent to minimize damage to bioactive compounds due to high temperatures [

47]. The ethanol extract of Sungkai leaves obtained from Sungkai leaves was 303 g, and the yield obtained was 12,12%. The crude extract of sungkai leaves from ethanol solvent was analyzed using LC/MS-MS. The results of the LC/MS-MS data analysis obtained a chromatogram in the form of a peak height plot, and the molecular weight of the compounds contained in the extract can be obtained so that you can know the number of compounds contained in each sample.

4.3. Phytochemical and Total Phenolics

Phytochemical screening was carried out to qualitatively test the compounds contained in the ethanol extract of Sungkai leaves, such as flavonoids, tannins, alkaloids, saponins, steroids, and phenolic compounds, following the procedures of previous studies

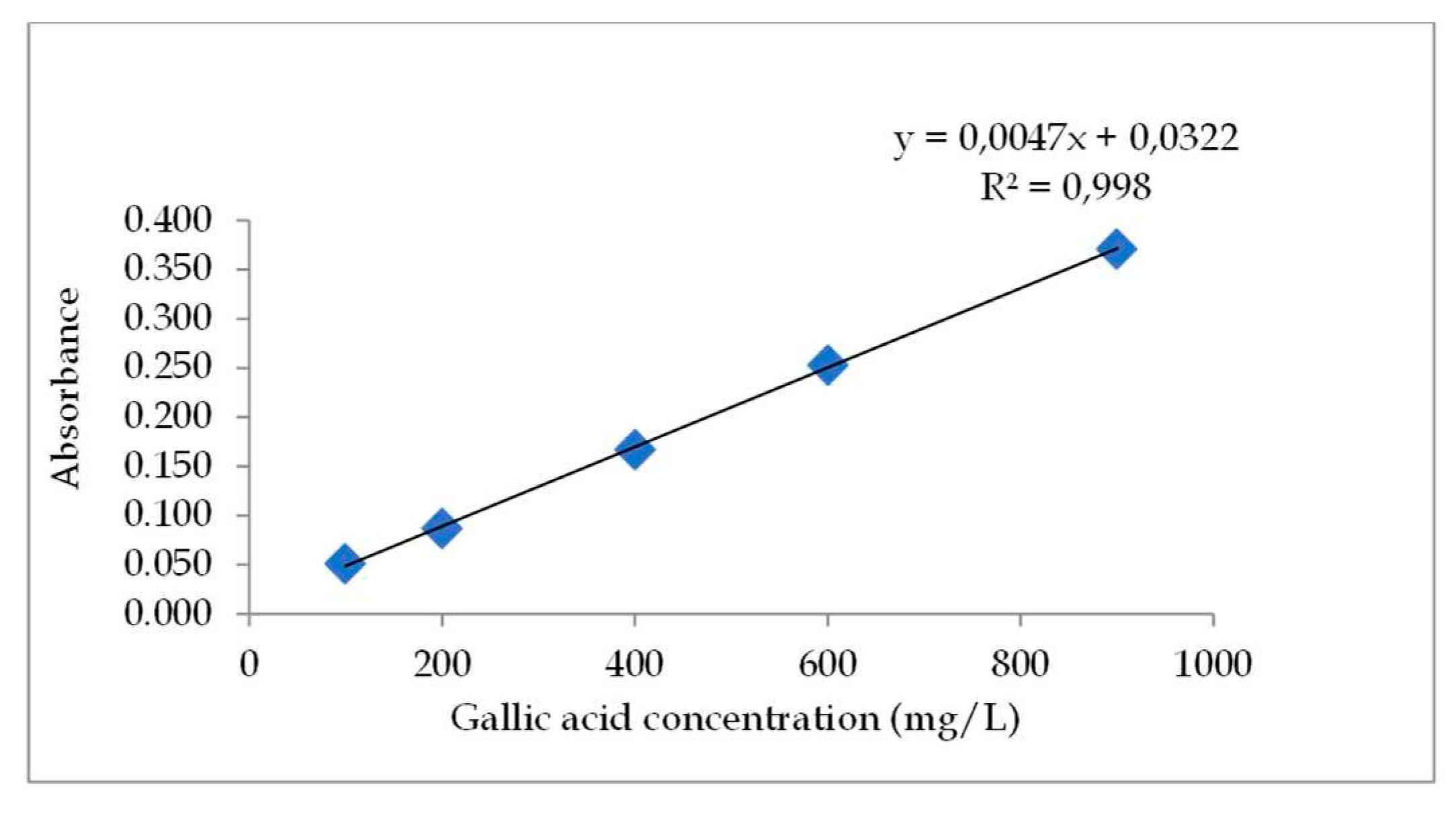

[48]. A gallic acid standard solution was made by dissolving 10 mg of gallic acid in a 10 mL volumetric flask using methanol solvent, thus obtaining a concentration of 1000 mg/L in the mother solution. Then the 1000mg/L mother liquor was diluted into several concentrations, namely 20; 40; 60; 80; and 100 mg/L. Determination of total phenolic content by the Folin-Ciocalteu method A total of 0.5 mL of sample (standard solution and test solution) was put into a 10 mL volumetric flask, 0.5 mL of Folin-Ciocalteau reagent was added, and the flask was allowed to stand for 5 minutes. Then 1 mL of 20% sodium carbonate was added and diluted with distilled water until the limit mark. The mixture was incubated for 2 hours. The absorbance was then measured at a wavelength of 750 nm [

29]. Based on the absorbance values obtained, a calibration curve was made and a linear regression equation for the standard solution was obtained. The total phenolic content of each test solution was determined from the linear regression equation of the standard solution. Total phenolic content is expressed in mg Galic Acid Equivalent (GAE)/g sample.

4.4. Microencapsulation

The microencapsulation process of the ethanol extract of Sungkai leaves was carried out using the extrusion method by following the procedure of the study [

28]. The dressing mixture was put into 100 mL of 85

0C distilled water, then 1 mL of tween-80 and 1g of dried sungkai leaf extract were added. After homogenization, the solution was dripped into a 0.2 M CaCl

2 solution with ethanol solvent (70%). The formed granules were allowed to stand for 15 min, after which they were filtered. Crosslinking was done with glutaraldehyde crosslinkers. The gel beads were soaked in glutaraldehyde solutions for 5 min. The gel beads were drained and dried to a constant weight.

4.5. % Yield.

The calculation of percent yield is done by calculating the overall weight of the microencapsulant product and the total weight of the microencapsulant material, which are then calculated using the following equation:

Where, %R: Yield product; W0: Microencapsulated weight (g); WT: total weight of microencapsulated material (g)

4.6. Water Solubility

One gram of microencapsulant was weighed and then dissolved in 20 milliliters of purified water. Then filter paper was used for filtration. Before use, the filter paper was weighed and heated for 30 min at 105°C. After the filtration procedure was completed, the filter paper and the remaining material were dried once again in the oven at 105 °C for 1 hour. It was then weighed after cooling for 15 min in a desiccator.

Where, a: weight of sample used (g); b: weight of filter paper (g); c: weight of filter paper and residue (g); d: moisture content of the sample (%).

4.7. Stability and Efficiency

Stability: A total of 1 gram of microencapsulant was placed in a vial bottle and stored at 60°C for 12 days. Total phenolic content was measured on days 0, 6, and 12. Product stability was observed against storage temperature and time by measuring total phenolic content.

Microencapsulation efficiency is the ratio of total encapsulated phenolic content (a) to total phenolic content before encapsulation (b).

Where, ME: microencapsulation efficiency; a: total phenolics successfully encapsulated; b: total phenolics before encapsulation.

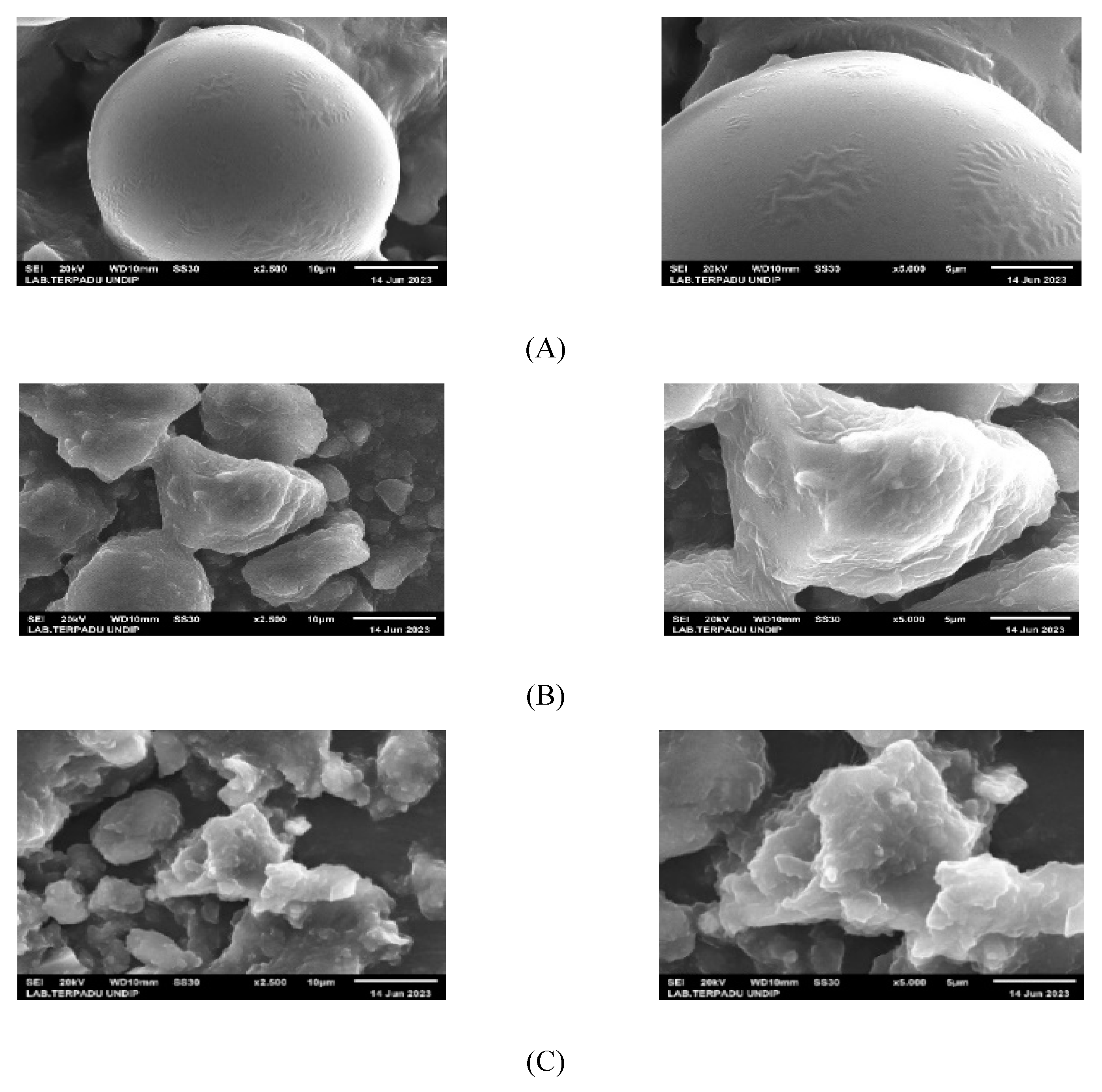

4.8. Morphology Analysis and IR Spectrum

Maltodextrin, inulin, Arabic gum, carboxymethylcellulose, and microencapsulants had their infrared spectra recorded using Fourier-Transform infrared spectroscopy (Alpha II-Bruker) at wave numbers ranging from 500 to 4000 cm-1. Using a SEM-EDX JEOL JSM-6510LA, the morphology form of the microencapsulants produced by the microencapsulation method were examined.

4.9. Antioxidant Activity Test

Antioxidant activity testing was carried out by adding 3 mL of a 0.1 mM DPPH solution to samples at various concentrations. As a negative control in this test, 2 mL of methanol was added to 3 mL of DPPH solution. Do the work in a dark place that is not exposed to sunlight. Then the absorbance of each concentration of test solution and control was measured at a wavelength of 515 nm. (Šukele et al., 2023). The measured absorbance values were contrasted with those measured using methanol added to DPPH solution as a negative control and ascorbic acid as a positive control. The IC

50 value, which indicates the concentration that provides 50% inhibition, was computed after the percent inhibition value, which displays the DPPH silencing activity, had been calculated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.L.T., M.L; methodology, F.F, I.L.T; software, R.D.P; validation, I.L.T and M.L.; formal analysis, I.L.T; investigation, F.F.; resources, F.F.; data curation, I.L.T; writing—original draft preparation, I.L.T and F.F; writing—review and editing, I.L.T.; visualization, F.F.; supervision, M.L; project administration, M.L; funding acquisition, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.