Submitted:

27 November 2023

Posted:

28 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wood dust concentration measurement

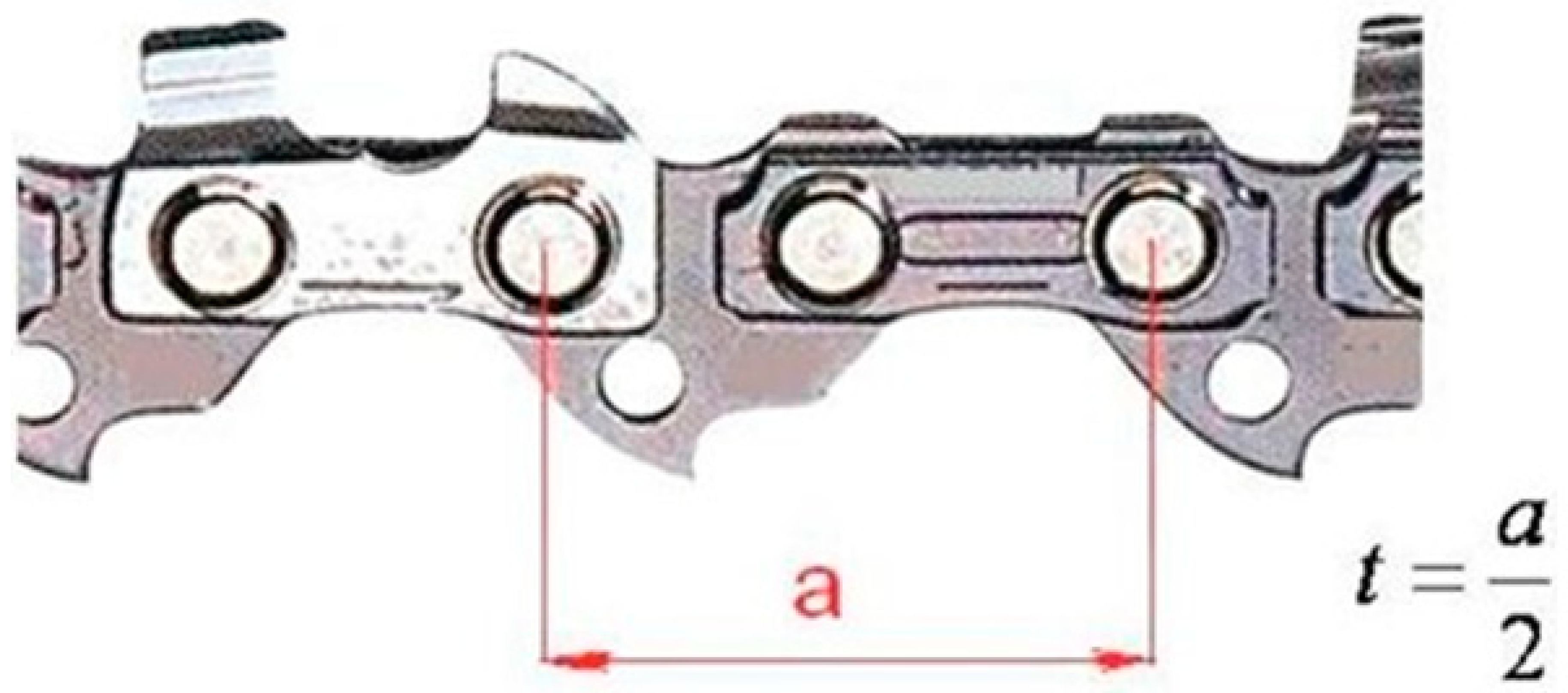

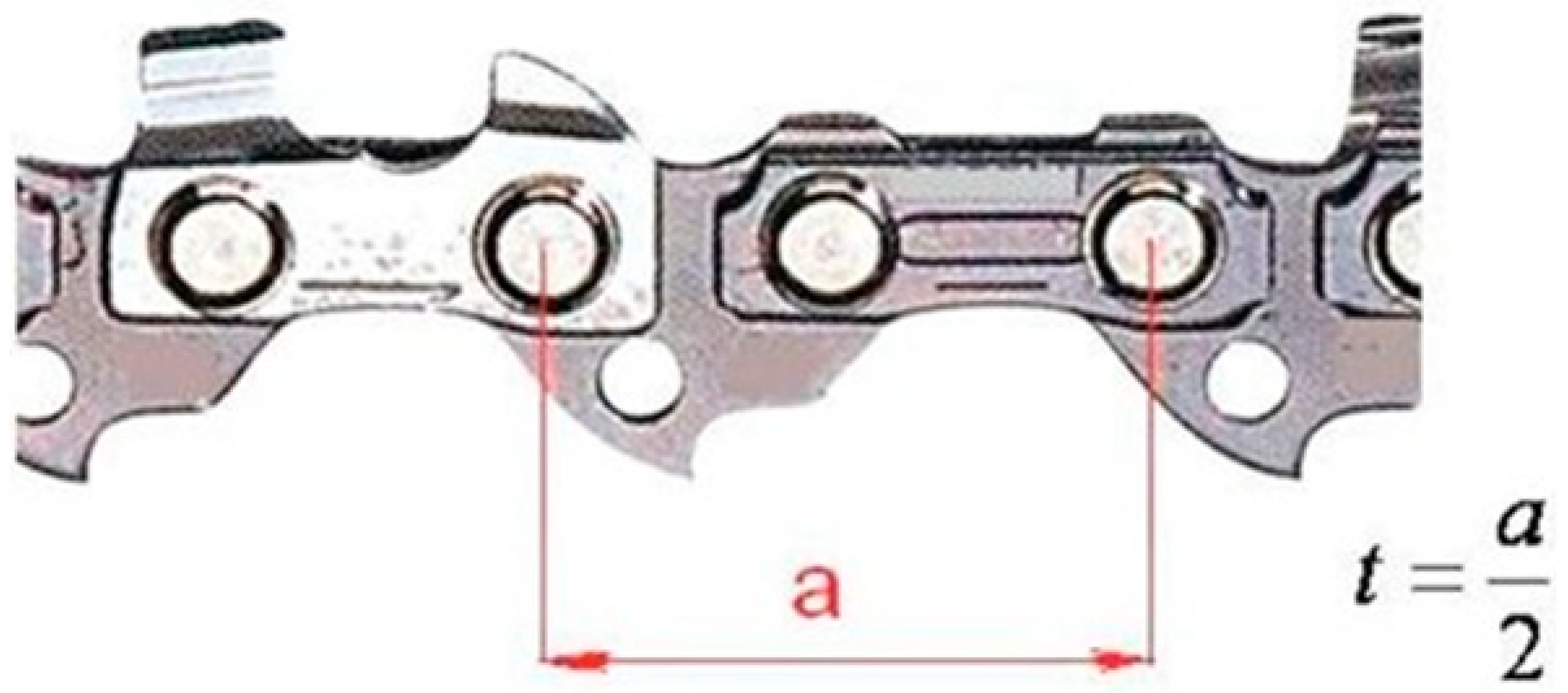

2.2. Chainsaw chain types

2.3. Test specimens

2.4. Timing of work tasks

2.5. Statistical methodology

3. Results

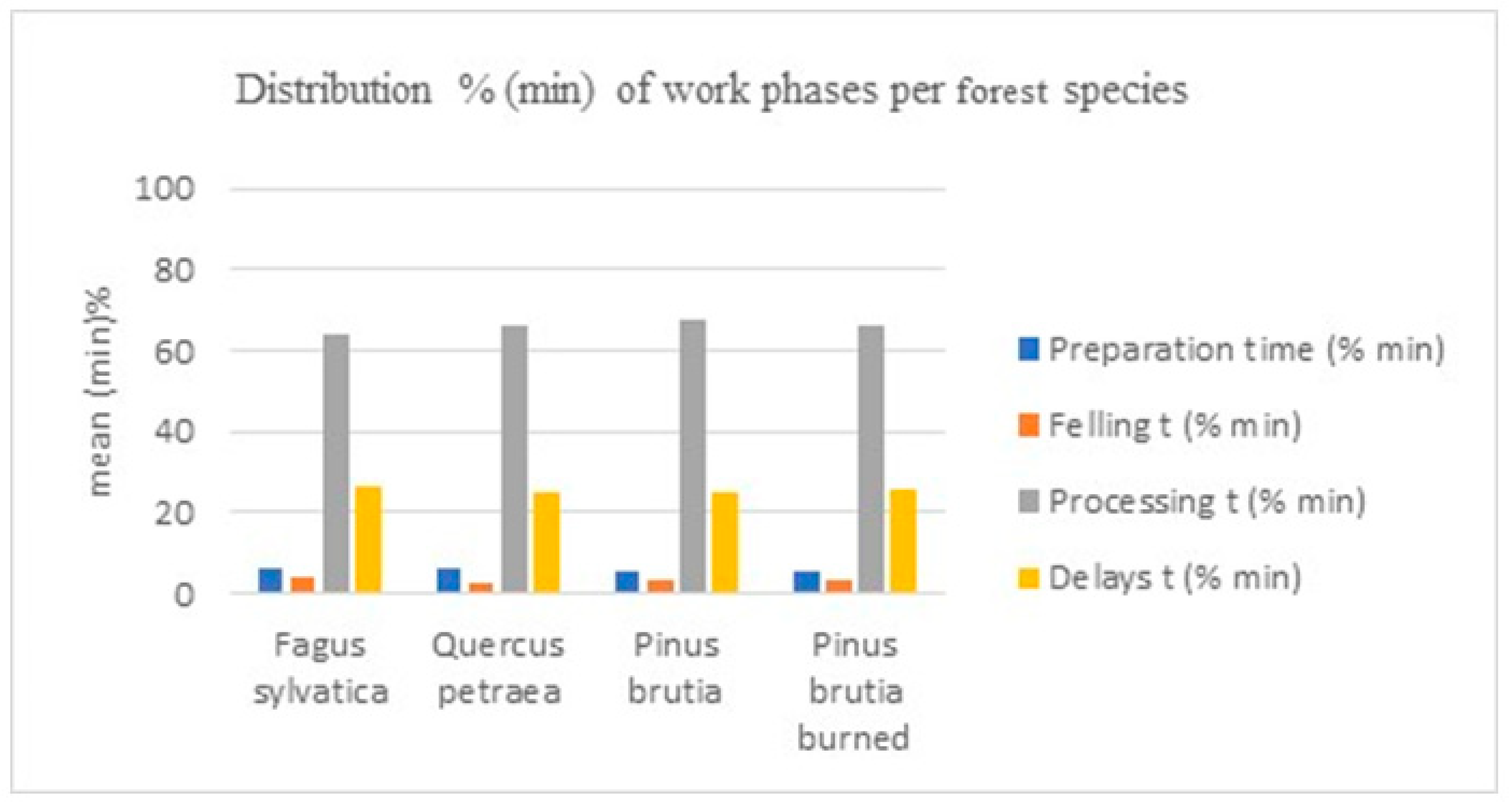

3.1. Resutls of work tasks

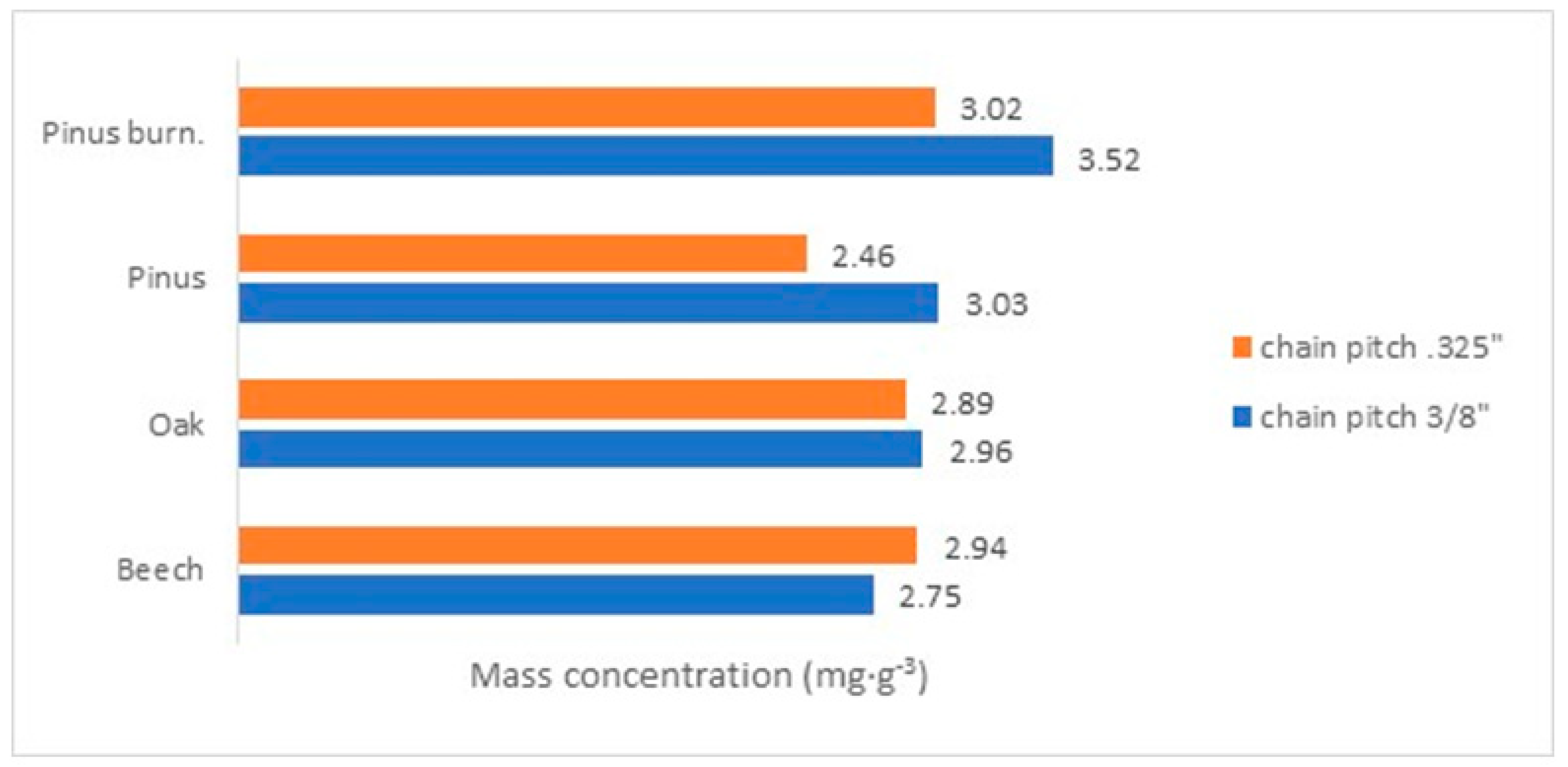

3.2. Inhalable wood dust concentrations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montorselli, N.B.; Lombardini, C.; Magagnotti, N.; Marchi, E.; Neri, F.; Picchi, G.; Spinelli, R. Relating Safety, Productivity and Company Type for Motor-Manual Logging Operations in the Italian Alps. Accident Analysis & Prevention 2010, 42, 2013–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vusić, D.; Šušnjar, M.; Marchi, E.; Spina, R.; Zečić, Ž.; Picchio, R. Skidding Operations in Thinning and Shelterwood Cut of Mixed Stands – Work Productivity, Energy Inputs and Emissions. Ecological Engineering 2013, 61, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjalainen, T.; Zimmer, B.; Berg, S.; Welling, J.; Schwaiger, H.; Finér, L.; Cortijo, P. Energy, Carbon and other Material Flows in the Life Cycle Assessment in Forestry and Forest Products. European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2001, p. 68.

- Spinelli, R.; Magagnotti, N.; Nati, C. Options for the Mechanized Processing of Hardwood Trees in Mediterranean Forests. International Journal of Forest Engineering 2009, 20, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourgholami, M.; Majnounian, B.; Zargham, N. Performance, capability and costs of motor-manual tree felling in Hyrcanian hardwood forest. Croatian Journal of Forest Engineering 2013, 34, 283–293. [Google Scholar]

- Liepiņš, K.; Lazdiņš, A.; Liepiņš, J.; Prindulis, U. Productivity and Cost-Effectiveness of Mechanized and Motor-Manual Harvesting of Grey Alder (Alnus Incana (L.) Moench): A Case Study in Latvia. Small-scale Forestry 2015, 14, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsianitis, D.; Tsioras, P.A. Time Consumption and Production Costs of Two Small-Scale Wood Harvesting Systems in Northern Greece. Small-scale Forestry 2016, 16, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenče, J.; Mihelič, M.; Poje, A. Influence of Chain Filing, Tree Species and Chain Type on Cross Cutting Efficiency and Health Risk. Forests 2017, 8, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallington, T.J.; Srinivasan, J.; Nielsen, O.J.; Highwood, E.J. Greenhouse gases and global warming. In Environmental and Ecological Chemistry—Volume 1; Sabljic, A., Ed.; Eolss Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 36–63. [Google Scholar]

- Dado, M.; Kučera, M.; Salva, J.; Hnilica, R.; Hýrošová, T. Influence of Saw Chain Type and Wood Species on the Mass Concentration of Airborne Wood Dust during Cross-Cutting. Forests 2009, 13, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, F.; Foderi, C.; Laschi, A.; Fabiano, F.; Cambi, M.; Sciarra, G.; Aprea, M.C.; Cenni, A.; Marchi, E. Determining Exhaust Fumes Exposure in Chainsaw Operations. Environmental Pollution 2016, 218, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukat, W.; Jakubek, B.; Barczewski, R.; Wróbel, M. The Influence of the Direction of Wood Cutting on the Vibration and Noise of Chainsaws. Tehnicki vjesnik - Technical Gazette 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.; Hoffmann, S.; Brieger, F.; Hartsch, F.; Jaeger, D.; Sauter, U.H. Vibration and Noise Exposure during Pre-Commercial Thinning Operations: What Are the Ergonomic Benefits of the Latest Generation Professional-Grade Battery-Powered Chainsaws? Forests 2021, 12, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftime, M.D.; Dumitrascu, A.-E.; Ciobanu, V.D. Chainsaw Operators’ Exposure to Occupational Risk Factors and Incidence of Professional Diseases Specific to the Forestry Field. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2022, 28, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kováč, J.; Krilek, J.; Dado, M.; Beňo, P. Investigating the Influence of Design Factors on Noise and Vibrations in the Case of Chainsaws for Forestry Work. FME Transactions 2018, 46, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landekić, M.; Bačić, M.; Pandur, Z.; Šušnjar, M. Vibration Levels of Used Chainsaws. Forests 2020, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arman, Z.; Nikooy, M.; Tsioras, P.A.; Heidari, M.; Majnounian, B. Physiological Workload Evaluation by Means of Heart Rate Monitoring during Motor-Manual Clearcutting Operations. International Journal of Forest Engineering 2021, 32, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheţa, M.; Marcu, M.; Borz, S. Workload, Exposure to Noise, and Risk of Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Case Study of Motor-Manual Tree Feeling and Processing in Poplar Clear Cuts. Forests 2018, 9, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywiński, W.; Turowski, R.; Jelonek, T.; Tomczak, A. Physiological Workload of Workers Employed during Motor-Manual Timber Harvesting in Young Alder Stands in Different Seasons. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health 2022, 35, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leszczyński, K. The Concentration of Carbon Monoxide in the Breathing Areas of Workers during Logging Operations at the Motor-Manual Level. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health 2014, 27, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, B.; Parker, R.; Todoroki, C. Exploring Chainsaw Operator Occupational Exposure to Carbon Monoxide in Forestry. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene 2016, 14, D1–D12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, F.; Laschi, A.; Foderi, C.; Fabiano, F.; Bertuzzi, L.; Marchi, E. Determining Noise and Vibration Exposure in Conifer Cross-Cutting Operations by Using Li-Ion Batteries and Electric Chainsaws. Forests 2018, 9, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimou, V.; Anezakis, V.-D.; Demertzis, K.; Iliadis, L. Comparative Analysis of Exhaust Emissions Caused by Chainsaws with Soft Computing and Statistical Approaches. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2017, 15, 1597–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimou, V.; Kantartzis, A.; Malesios, C.; Kasampalis, E. Research of Exhaust Emissions by Chainsaws with the Use of a Portable Emission Measurement System. International Journal of Forest Engineering 2019, 30, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, E.; Neri, F.; Cambi, M.; Laschi, A.; Foderi, C.; Sciarra, G.; Fabiano, F. Analysis of Dust Exposure during Chainsaw Forest Operations. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 2017, 10, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimou, V.; Malesios, C.; Chatzikosti, V. Assessing Chainsaw Operators’ Exposure to Wood Dust during Timber Harvesting. SN Applied Sciences 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew E, Gebre Y, De Wael K (2015) A Survey of Occupational Exposure to Inhalable Wood Dust Among Workers in Small- and Medium-Scale Wood-Processing Enterprises in Ethiopia. The Annals of Occupational Hygiene 2014. [CrossRef]

- Mantanis, G; Dalos, G. ; Anastasis, G. The impact of wood dust on the health of woodworking and furniture industry workers. Geotechnical Science Issues 2005, 16(2), 74–80. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Tureková, I.; Mračková, E.; Marková, I. Determination of Waste Industrial Dust Safety Characteristics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, D. Air quality on biomass harvesting operations. In Proceedings of the 34th Council on Forest Engineering Annual Meeting, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 12–15 June 2011; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Hazard Prevention and Control in the Work Environment: Airborne Dust; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Charbotel, B.; Fervers, B.; Droz, J.P. Occupational Exposures in Rare Cancers: A Critical Review of the Literature. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2014, 90, 99–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARC. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Wood Dust and Formaldehyde; WHO: Lyon, France, 1995; Volume 62. [Google Scholar]

- Council Directive 1999/38/EC of 29 April 1999 Amending for the Second Time Directive 90/394/EEC on the Protection of Workers from the Risks Related to Exposure to Carcinogens at Work and Extending It to Mutagens. Available online: https://Eur-Lex.Europa.Eu/Legal-Content/BG/TXT/?Uri=CELEX:31999L0038 (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Directive (EU) 2017/2398 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2017 Amending Directive 2004/37/EC on the Protection of Workers from the Risks Related to Exposure to Carcinogens or Mutagens at Work (Text with EEA Relevance). 2017. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2017/2398/oj/eng (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- European Union. Directive 2006/42/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 May 2006 on Machinery, and Amending Directive 95/16/EC (Recast); European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dąbrowski, A. Analysis and Laboratory Testing of Technical Injury Prevention Measures for Portable Combustion Chainsaws. Forests 2020, 11, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimou V.; Tioutiountzi Th. Malesios Ch. Determining occupational exposure to inhalable wood dust in forestry operation, 21 November 2023, PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square. 21 November. [CrossRef]

- Dimou, V.; Malesios, C.; Chatzikosti, V. Assessing Chainsaw Operators’ Exposure to Wood Dust during Timber Harvesting. SN Applied Sciences 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HSE: Information about Health and Safety at Work Available online: https://www.hse.gov.uk.

- Björheden, R,; Thompson, A.M. An International Nomenclature for Forest Work Study. Paper presented at the XX IUFRO Congress, Tampere, 6-12 August 1995, p. 16. 12 August.

- Casella, G.; Berger, R.L. Statistical Inference; 2001; ISBN 978-0-534-24312-8.

- Sprinthall, R.C. Basic Statistical Analysis; 2011; ISBN 978-0-205-05217-2.

- Montgomery, D.C.; Runger, G.C. Applied Statistics and Probability for Engineers; 2014; ISBN 978-1-118-74393-5.

- Kauppinen T.; Vincent R.; Liukkonen T.; Grzebyk M.; Kauppinen A.; Welling I.; Arezes P.; Black N.; Bochmann F.; Campelo F.; Costa M.; Elsigan G.; Goerens R.; Kikemenis A.; Kromhout H.; Miguel S.; Mirabelli D.; McEneany R.; Pesch B.; Plato N.; Schlünssen V.; Schulze J.; Sonntag R.; Verougstraete V.; De Vicente MA.; Wolf J.; Zimmermann M.; Husgafvel-Pursiainen K.; Savolainen K. Occupational Exposure to Inhalable Wood Dust in the Member States of the European Union. The Annals of Occupational Hygiene 2006. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.K.; Wong, M.H.; Tam, N.F.Y.; Choy, A.C.K. Properties and Toxicity of Airborne Wood Dust in Woodworking Establishments. Toxicology Letters 1985, 26, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poje, A.; Potočnik, I.; Košir, B.; Krč, J. Cutting Patterns as a Predictor of the Odds of Accident among Professional Fellers. Safety Science 2016, 89, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, D.; Kos, A.; Zečić, Ž.; Jazbec, A.; Šušnjar, M. Concentration of Wood Dust in the Working Environment during Felling and Processing of Beech Trees. In Proceedings of the FORMEC 2005—Scientific Cooperation for Forest Technology Improvement, Ljubljana, Slovenija, 26–28 September 2005; Biotechnical Faculty, University of Ljubljana: Ljubljana, Slovenija, 2005; p. 123. [Google Scholar]

- Horvat, D.; Kos, Ž.; Zečić, Ž.; Jazbec, A.; Šušnjar, M.; Očkajová, A. Tree Cutters’ Exposure to Oakwood Dust—A Case Study from Croatia. Die Bodenkult. 2007, 58, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Horvat, D.; Čavlović, A.; Zečić, Ž.; Šušnjar, M.; Bešlić, I.; Madunić-Zečić, V. Research of Fir-Wood Dust Concentration in the Working Environment of Cutters. Croatian Journal of Forest Engineering 2017, 26(2), 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J.L. Changes in Logging Injury Rates Associated with Use of Feller-Bunchers in West Virginia. Journal of Safety Research 2002, 33, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelsson, S.-Ă. The Mechanization of Logging Operations in Sweden and Its Effect on Occupational Safety and Health. Journal of Forest Engineering 1998, 9, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandryk, J.; Alwis, K.U.; Hocking, A.D. Work-Related Symptoms and Dose-Response Relationships for Personal Exposures and Pulmonary Function among Woodworkers. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 1999, 35, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demers, P.A.; Kogevinas, M.; Boffetta, P.; Leclerc, A.; Luce, D.; Gérin, M.; Battista, G.; Belli, S.; Bolm-Audorf, U.; Brinton, L.A.; et al. Wood Dust and Sino-nasal Cancer: Pooled Reanalysis of Twelve Case-control Studies. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 1995, 28, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chain Type | Coding | No of Processed Trees |

Average DBH5 (cm) |

Number of Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitch Chain 3/8” | 3/8”Fs1 | 45 | 60.48 | 12 |

| 3/8”Qp2 | 91 | 38.57 | 12 | |

| 3/8”Pbr3 | 256 | 30.78 | 12 | |

| 3/8”Pbr.bur4 | 296 | 28.43 | 12 | |

| Pitch Chain 0.325” | 0.325”Fs | 80 | 53.01 | 12 |

| 0.325”Qp | 184 | 38.96 | 12 | |

| 0.325”Pbr | 460 | 32.21 | 12 | |

| 0.325”Pbr.bur | 495 | 29.36 | 12 | |

| 1: Fagus sylvatica, 2: Quercus petraea, 3: Pinus brutia, 4: P. brutia burned, 5: Diameter at Breast Height | ||||

| Chain type | Mean preparation time (minutes) |

Total time on-site (minutes) |

Mean chainsawrunning time (minutes) |

Mean $delay (minutes) |

Chainsaw running time as a percentage of total timeon-site |

Number of samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitch Chain 3/8” | 20.35 | 335.33 | 226.73 | 88.26 | 67.60 | 48 |

| Pitch Chain 0.325” | 20.84 | 354.10 | 244.48 | 88.77 | 68.88 | 48 |

| Chain type | Mean felling time (minutes, %) | Mean limbing time (minutes, %) | Mean bucking time (minutes, %) | No of processed trees |

Average DBH (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitch Chain 3/8” | 8.44 3.72% |

32.88 14.50% |

185.41 81.78% |

688 | 39.57 |

| Pitch Chain 0.325” | 15.99 6.54% |

52.59 21.51% |

175.91 71.95% |

1219 | 38.39 |

| Chain type | Mean wood dust concentration (mg/m3) | Min wood dust concentration (mg/m3) | Max wood dust concentration (mg/m3) | Mean wood dust concentration / 8 hours (mg/m3) | Mean humidity (%) | Mean temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitch Chain 3/8” | 3.07 (±1.62)* | 0.61 | 8.11 | 4.19 | 52.28 | 16.98 |

| Pitch Chain 0.325” | 2.82 (±1.25) | 0.87 | 5.82 | 3.83 | 48.24 | 18.08 |

| * Standard deviation | ||||||

| Chain type | ≤3 mg/m3 | (3,5] mg/m3 | >5 mg/m3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pitch Chain 3/8” | 26 (54.17%) | 16 (33.33%) | 6 (12.50%) |

| Pitch Chain 0.325” | 28 (58.00%) | 18 (38.00%) | 2 (4.17%) |

| Chain type | Beech | Oak | Pine | Pine burned | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitch Chain 3/8” | 0 (0.00%) |

1 (8.33%) |

2 (16.67%) |

3 (25.00%) |

6 (12.50%) |

| Pitch Chain 0.325” | 2 (4.17%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (4.17%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).