Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a genetic disease associated with variants in the genes of the cardiac sarcomere and characterized by enhanced cardiac actin-myosin crossbridge cycling leading to hyperdynamic contractility, cardiac hypertrophy, and diastolic dysfunction [

1]. Obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (oHCM) occurs when hypercontractility, hypertrophy and mitral valve morphology contribute to outflow tract obstruction [

1]. Mavacamten is a first-in-class, small molecule inhibitor of cardiac myosin ATPase approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in April 2022 for use in patients with symptomatic oHCM. Mavacamten reduces contractile force through decreased myosin head availability [

2]. We now have more than 18 months of experience with commercial mavacamten following the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) pathway, and no reports exist of its longer term, real-world effects. Here, we report a case series of 50 patients with oHCM treated with mavacamten and closely monitored through a multidisciplinary program at the Stanford Center for Inherited Cardiovascular Disease (SCICD).

Case report

A 26 year old man presented with severely reduced exercise capacity (VO2max 67% of predicted) due to obstructive HCM characterized by severe septal hypertrophy (2.8 cm) with associated late gadolinium enhancement. He had normal-to-hyperdynamic left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, 63%) and a resting LVOT gradient of 90 mmHg with systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve causing moderate mitral regurgitation. Genetic testing revealed a likely pathogenic variant in MYH7 (c.1051A>G, p.Lys351Glu).

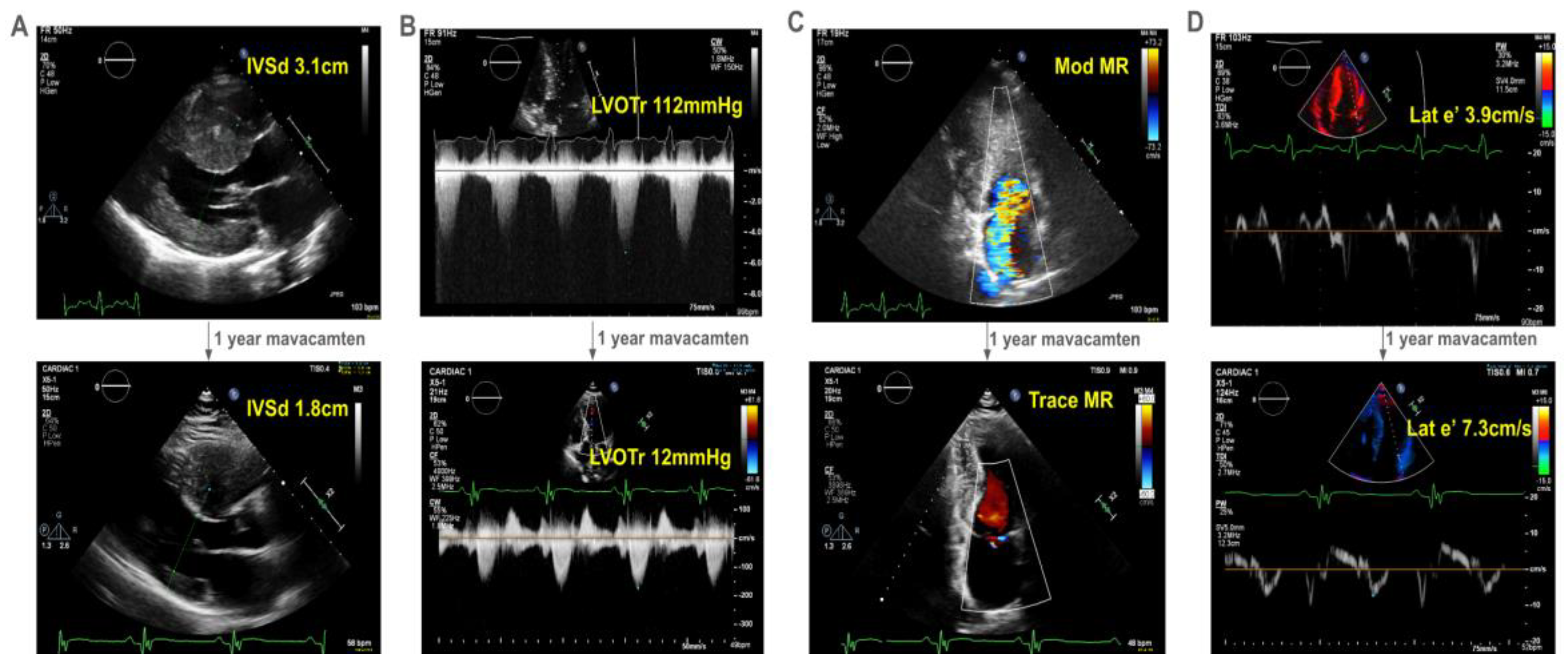

The patient developed decreasing exercise tolerance, with increasing left ventricular septal hypertrophy to 3.1cm (

Figure 1A) and LVOT gradient of 112mmHg at rest (

Figure 1B). His SAM-associated moderate mitral regurgitation worsened (

Figure 1C). He had echocardiographic evidence of diastolic dysfunction, with reduced lateral e’ of 3.9cm/s (

Figure 1D). He deferred surgical myectomy out of concern for operative risk.

He started mavacamten at 40 years of age. After one year, there was dramatic improvement in his symptoms with a reduction in his interventricular septal thickness from 3.1cm to 1.8cm (

Figure 1A) and resting LVOT gradient from 112 mmHg to 12mmHg (

Figure 1B). Mitral regurgitation reduced to trace (

Figure 1C). Finally, he had improvement in his lateral e’ velocity from 3.9 cm/s to 7.3 cm/s (

Figure 1D,

online video).

One year experience of real world mavacamten therapy

We have observed similar trends across patients on mavacamten. In our cohort, 64% (32) were women with an average age of 63.5±13.5 years (SD) and body-mass index of 28.5±5.4 kg/m

2. All patients were closely monitored according to the FDA-mandated REMS pathway[

3], with an average 36 weeks follow up. Mavacamten was temporarily held in 5 patients (10%) due to valsalva LVOT gradient < 20mmHg, and in 2 patients (4%) for LVEF <50%[

3]. Mavacamten was stopped in 3 patients (6%) for fatigue/malaise (n=2), and loss of insurance coverage (n=1). We noted minimal atrial fibrillation or non-sustained ventricular tachycardia on follow-up monitoring. Mavacamten doses on most recent follow-up were: 2.5mg (9, 20%), 5mg (17, 38%), 10mg (13, 29%), and 15mg (6, 13%,

Table 1).

We observed significant changes in echocardiographic measurements of mavacamten-treated patients at most recent followup compared to baseline. In line with trial data, there was a dramatic mean decrease in LVOT gradient at rest and with Valsalva with reductions of -33mmHg [-45,-21] (95% CI) in resting LVOT gradient, and -51mmHg [-69,-32] reduction in Valsalva LVOT gradient (

P<0.001, pairwise T-test.) There was significant improvement in the proportion of patients with moderate or severe mitral regurgitation (

P<0.001, McNemar-Bowker,

Table 1). Accompanying this change in LVOT gradient, we noted a significant decrease in diastolic interventricular septal thickness (-0.2 [-0.30, -0.13] cm,

P<0.001,

Table 1). We observed a clinically insignificant reduction in mean LVEF from 67 to 64% (-3.1 [-5.4,-0.8]%,

P=0.008) without change in right ventricular systolic pressure (

P= 0.12,

Table 1). There was a significant decrease in medial e’ (-0.9 cm/s [-1.7, -0.09],

P=0.03), but no significant change in E/e’ or lateral e’ (

Table 1). These positive changes in echocardiographic measurements were mirrored by New York Heart Association (NYHA) symptom class, which improved dramatically with mavacamten treatment (McNemar-Bowker test,

P<0.001). Two elderly patients with severe concomitant disease unrelated to oHCM (4%) died during follow up: One had pre-existing hypoxemic pulmonary hypertension that progressed. The second died from unrelated septic shock. One patient (2%) developed septic shock due to tricuspid valve endocarditis during which mavacamten was discontinued, and ultimately required ECMO and complex cardiac surgery. Only a limited subset of our cohort had pre- and post-mavacamten cardiopulmonary exercise stress testing (n=7), precluding meaningful statistical analysis.

To enable timely and optimally monitored access to cardiac myosin inhibitor therapy for our patients, our center developed a nurse-led training course for the FDA REMS program[

3]. This training focuses on appropriate patient selection, prescription, authorization, triage and surveillance, and provides education on common clinical problems that can arise during therapy with an emphasis on interdisciplinary care. Particular emphasis was placed on REMS monitoring and dose adjustment based on echocardiographic parameters. In the hope that our experience can enable expert oHCM care with cardiac myosin inhibitors at other centers, our pathway and training tools are shared (see

online materials).

Conclusions

We describe real-world use of mavacamten in 50 patients with oHCM. Consistent with EXPLORER-HCM[

4] and VALOR-HCM[

5], we report significant improvement in wall thickness, mitral regurgitation, LVOT obstruction and NYHA class. Moreover, in our center’s experience, neither arrhythmia burden, nor contractility have worsened in the vast majority of patients: We note a clinically insignificant mean decrease in LVEF, with only two patients requiring temporary mavacamten discontinuance for LVEF < 50%. Adverse events were rare, unrelated to mavacamten itself, and seen solely in patients with disease too advanced to have been represented in clinical trials. Our multidisciplinary pathway enabled us to provide a large number of patients with a novel closely-monitored therapeutic within just a few months of commercial availability. These data lead us to conclude that mavacamten, as a first-in-class cardiac myosin inhibitor, is safe and efficacious in real-world settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

Declarations Of Interest

V.N.P. has consulting and advisory relationships with BioMarin, Lexeo Therapeutics and Viz.ai and receives funding from BioMarin, the John Taylor Babbitt Foundation, the Sarnoff Cardiovascular Research Foundation, and NHLBI R01HL168059 and K08HL143185. M.T.W. reports research grant and in kind support from Bristol Myers Squibb, , consulting for Leal Therapeutics, , outside the submitted work. E.A.A. reports advisory board fees from Apple and Foresite Labs. E.A.A. has ownership interest in SVEXA, Nuevocor, DeepCell, and Personalis, outside the submitted work. E.A.A. is a board member of AstraZeneca. D.S.K. is supported by the Wu-Tsai Human Performance Alliance and NIH 1L30HL170306. CSW reports consultancy fees from AiRNA Bio and Avidity Biosciences. CSW is supported by NIH grants K08HL167699, L30HL159413, F32HL160067 and American Heart Association grant 23CDA1042900. The remainder of authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Stanford Center for Inherited Cardiovascular Disease Author Masthead

Karim I Sallam, Masataka Kawana, Chad S Weldy, Marco Perez, Joshua W Knowles, Jason Tso, Cindy Lamendola, Allysonne Smith, Nancy Robles, Colleen Bonnett, Ellen Bacolor, Kimberly Hecker, Isabella Cuenco, Beth Kao, Elise Munsey, Andrea Linder, Kathleen Lacar, Julia Platt, Chloe Reuter, Tia Moscarello, Ryan Murtha, Jennifer Kohler, Hannah Ison, Mitchel Pariani, Anusha Klinder, Priya Nair, Jennifer Marino, Andrea Linder, Ruchi Patel, Matthew T Wheeler, Euan A Ashley, Victoria N Parikh.

References

- Members WC, Ommen SR, Mital S, Burke MA, Day SM, Deswal A, Elliott P, Evanovich LL, Hung J, Joglar JA, Kantor P, Kimmelstiel C, Kittleson M, Link MS, Maron MS, Martinez MW, Miyake CY, Schaff HV, Semsarian C, Sorajja P. 2020 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:e159–e240. [CrossRef]

- Green EM, Wakimoto H, Anderson RL, Evanchik MJ, Gorham JM, Harrison BC, Henze M, Kawas R, Oslob JD, Rodriguez HM, Song Y, Wan W, Leinwand LA, Spudich JA, McDowell RS, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. A small-molecule inhibitor of sarcomere contractility suppresses hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in mice. Science. 2016;351:617–621. [CrossRef]

- Squibb B-M. CAMZYOS (mavacamten) REMS Program [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 14];Available from: https://www.camzyosrems.com.

- Olivotto I, Oreziak A, Barriales-Villa R, Abraham TP, Masri A, Garcia-Pavia P, Saberi S, Lakdawala NK, Wheeler MT, Owens A, Kubanek M, Wojakowski W, Jensen MK, Gimeno-Blanes J, Afshar K, Myers J, Hegde SM, Solomon SD, Sehnert AJ, Zhang D, Li W, Bhattacharya M, Edelberg JM, Waldman CB, Lester SJ, Wang A, Ho CY, Jacoby D, investigators E-H study, Bartunek J, Bondue A, Craenenbroeck EV, Kubanek M, Zemanek D, Jensen M, Mogensen J, Thune JJ, Charron P, Hagege A, Lairez O, Trochu J-N, Axthelm C, Duengen H-D, Frey N, Mitrovic V, Preusch M, Schulz-Menger J, Seidler T, Arad M, Halabi M, Katz A, Monakier D, Paz O, Viskin S, Zwas D, Olivotto I, Rocca HPB-L, Michels M, Dudek D, Oko-Sarnowska Z, Oreziak A, Wojakowski W, Cardim N, Pereira H, Barriales-Villa R, Pavia PG, Blanes JG, Urbano RH, Diaz LMR, Elliott P, Yousef Z, Abraham T, Afshar K, Alvarez P, Bach R, Becker R, Choudhury L, Fermin D, Jacoby D, Jefferies J, Kramer C, Lakdawala N, Lester S, Marian A, Masri A, Maurer M, Nagueh S, Owens A, Owens D, Rader F, Saberi S, Sherrid M, Shirani J, Symanski J, Turer A, Wang A, Wever-Pinzon O, Wheeler M, et al. Mavacamten for treatment of symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (EXPLORER-HCM): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396:759–769. [CrossRef]

- Desai MY, Owens A, Geske JB, Wolski K, Naidu SS, Smedira NG, Cremer PC, Schaff H, McErlean E, Sewell C, Li W, Sterling L, Lampl K, Edelberg JM, Sehnert AJ, Nissen SE. Myosin Inhibition in Patients With Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Referred for Septal Reduction Therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80:95–108. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).