Submitted:

25 November 2023

Posted:

27 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- a)

- The design and hydrological characteristics of paddy-rice catchments.

- b)

- Whether puddling is essential in paddy rice catchments.

- c)

- Suitable paddy soil conditions and the implications of intermittent soil wetting and drying on changes in hydrological properties, crop yields, irrigation efficiency, and GHG emissions in paddy rice catchments.

- d)

- Reasons farmers are skeptical in adopting AWD practice.

2. Attributes of Paddy-Rice Environment

2.1. Smallholder Agricultural Development in East Africa

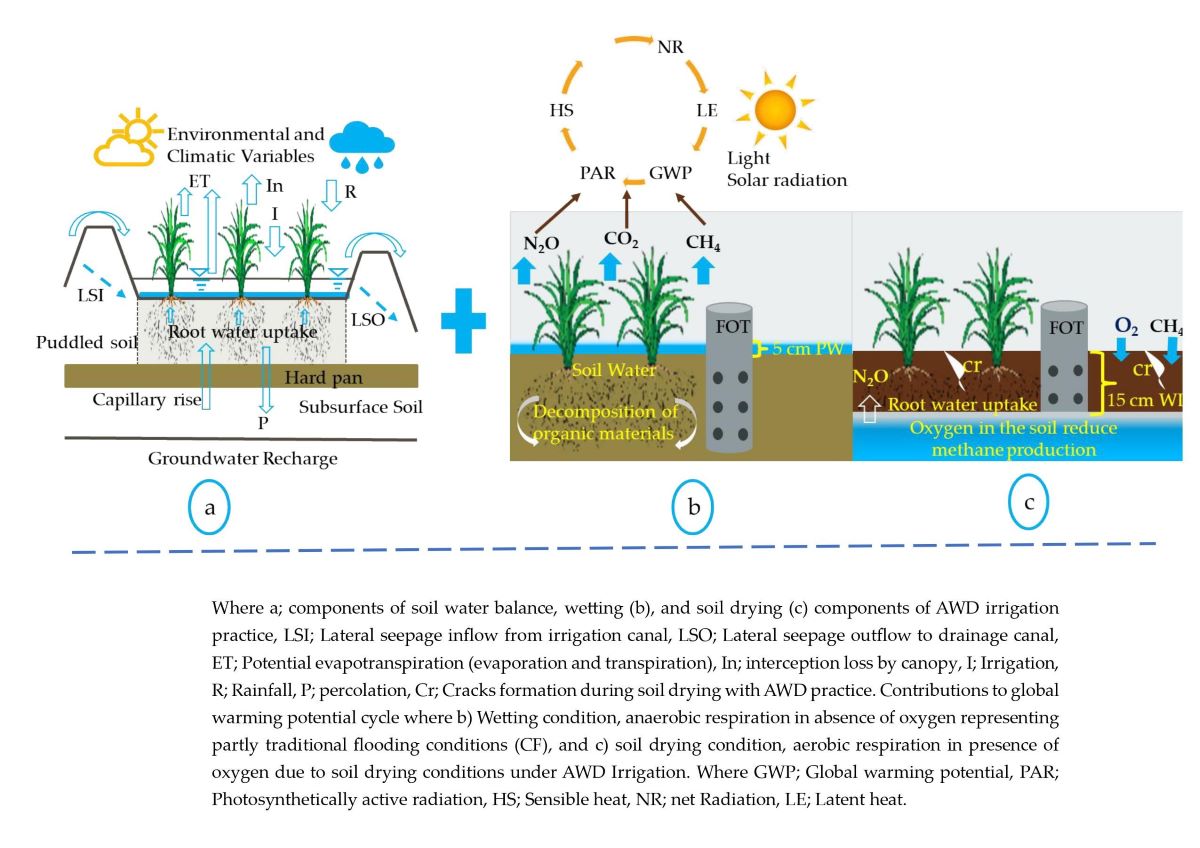

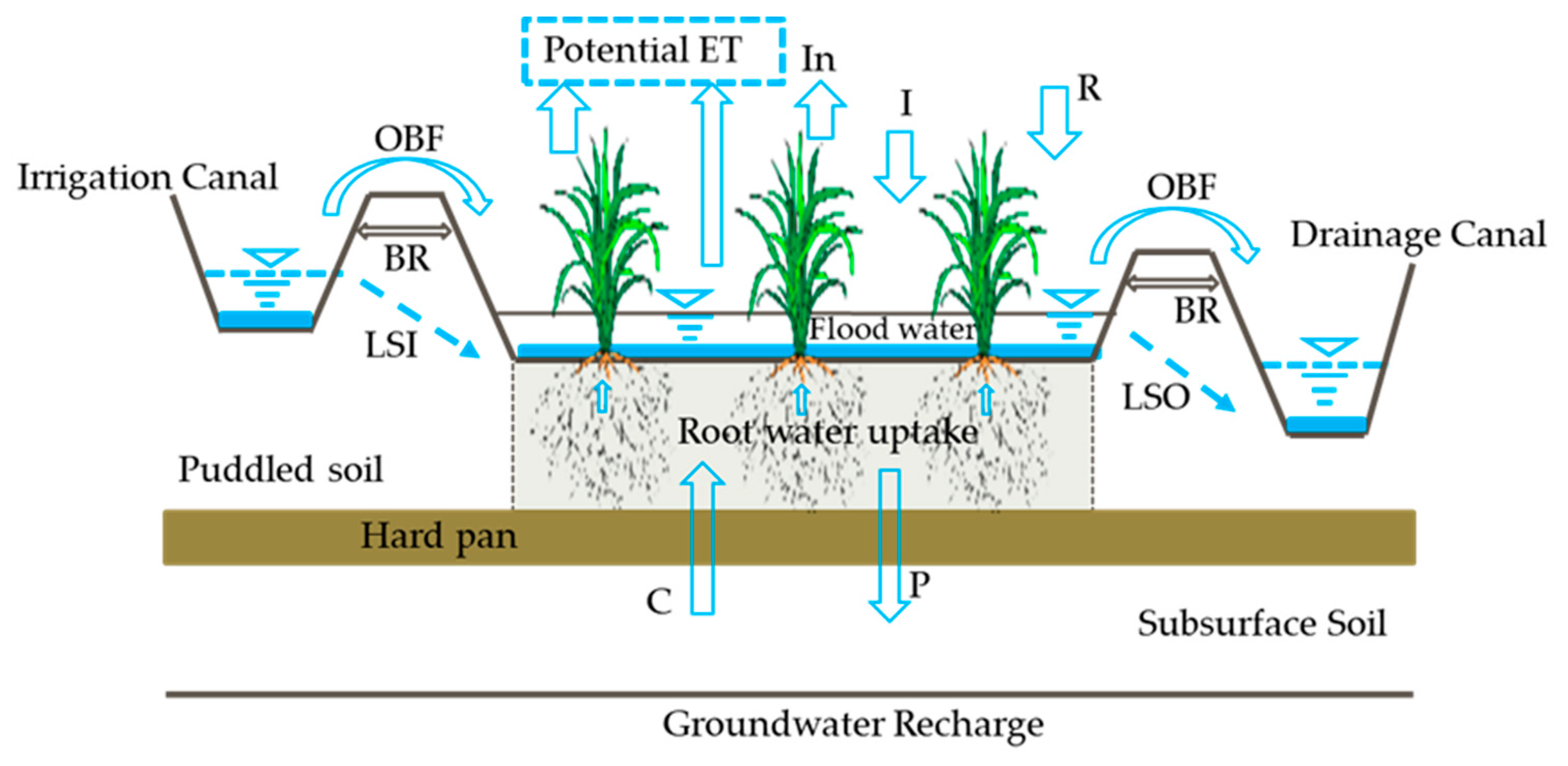

2.2. Components of Water Balance in Paddy Fields

2.3. Hydrological Properties of Paddy Rice Catchments Under Traditional Flooding

2.3.1. Puddling, Bunds, and Preferential Flow

2.3.2. Percolation and Seepage

2.4. Paddy Rice Cultivation and Crop Water Requirements

2.5. Water Management Strategies in Paddy Rice Watershed.

2.6. Climate Change and Paddy Cultivation

2.7. Integrated Paddy Rice-Fish Culture

3. Defining AWD Practice in Paddy-Rice Catchments

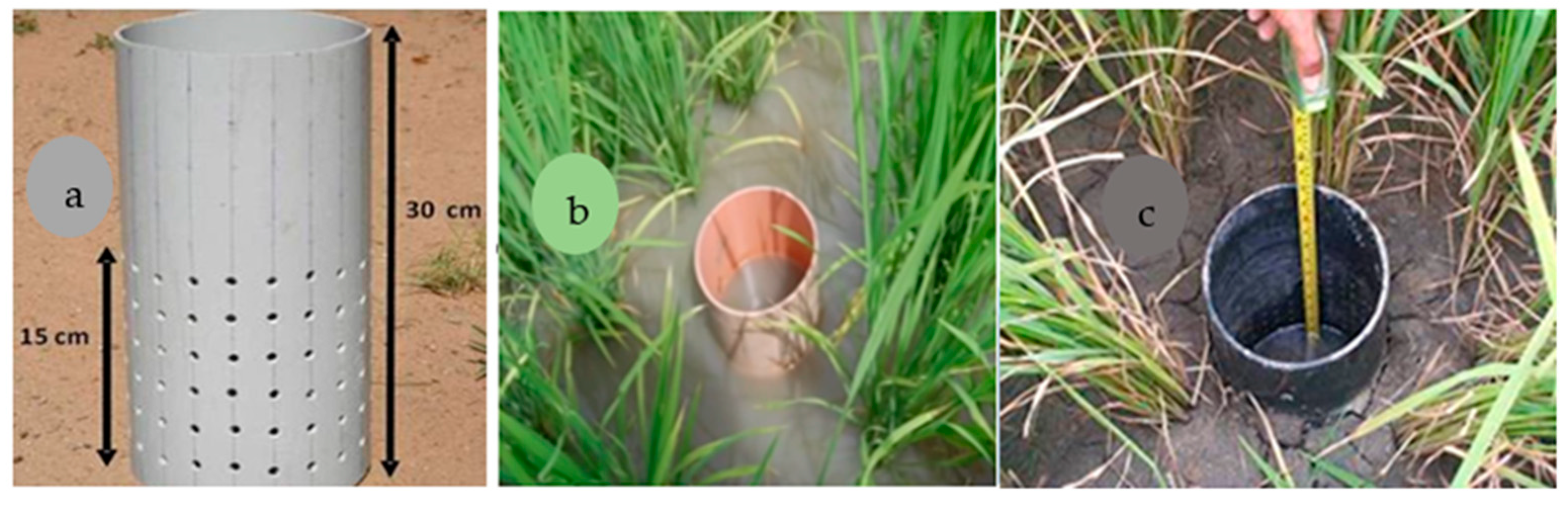

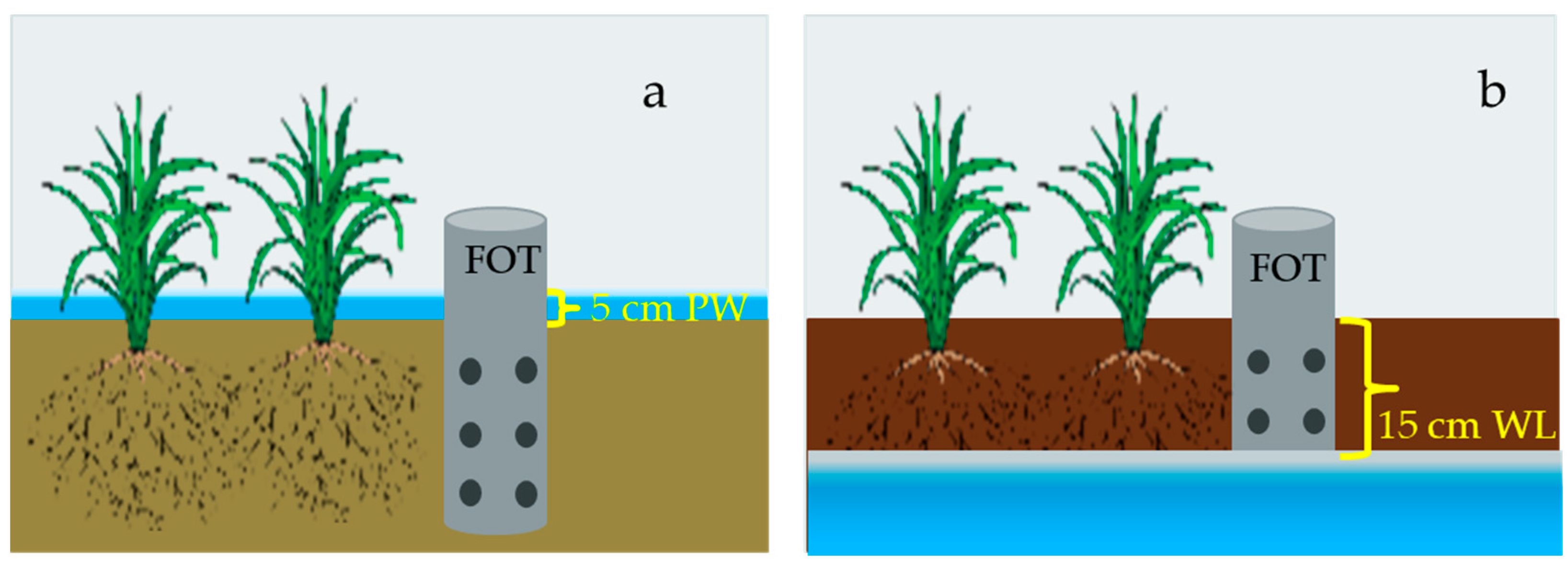

3.1. AWD Recommendations

3.2. Impacts of AWD Irrigation Practice

3.2.1. Crop Height, Yield, and Yield Components

3.3.2. Water Use Efficiency and Productivity.

3.2.3. Paddy Soil Hydrological Properties with AWD Practice

3.3.4. Redox Potential with AWD Practice

4. Adoption, Potential Challenges and Limitations of AWD Practice

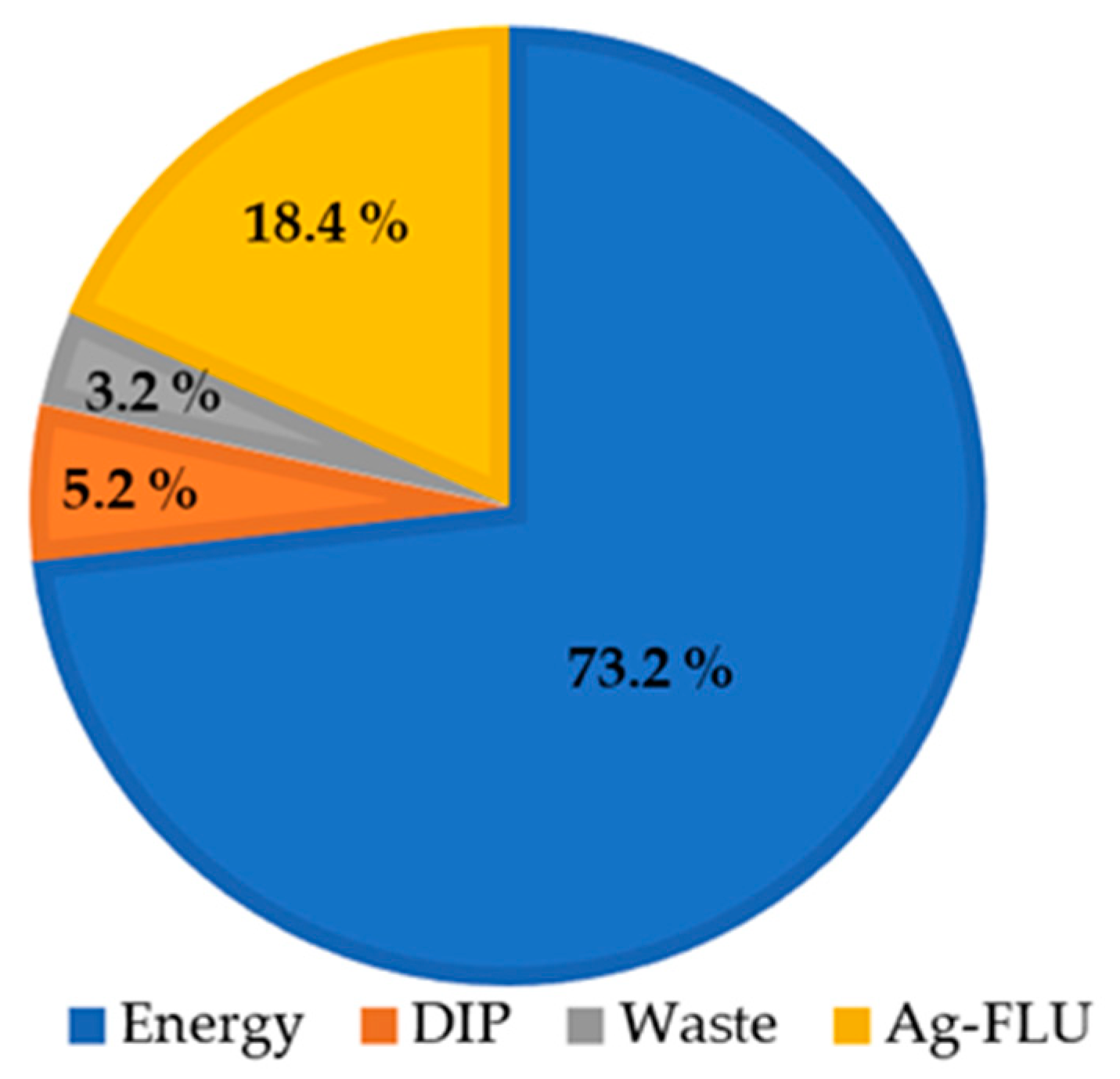

4.1. AWD Practice as Climate Adaptation and Mitigation Strategy

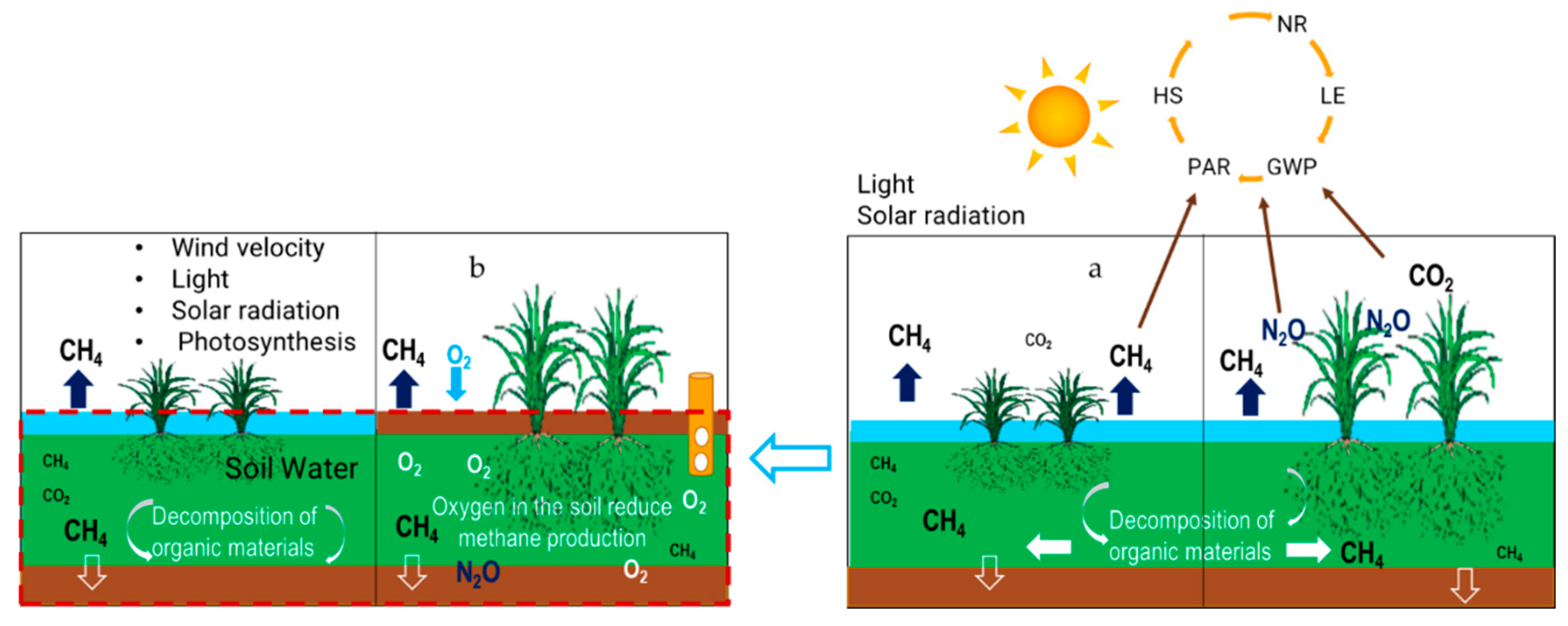

4.2. Methane GHG and Carbon Equivalent Estimation in Paddy Rice Catchment

4.3. Water Management and Carbon Dynamics with AWD in Paddy Rice Fields

5. Suggestions and Future Research Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Misr, K.A. Climate change and challenges of water and food security. Intl. J. Sust. Built Environ. 2014, 3, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidle, R.C.; Khan, A.A.; Caiserman, A.; Qadamov, A.; Khojazoda, Z. Food security in high mountains of Central Asia: a broader perspective. BioSci. 2023, 73, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathi, T.; Vanitha, K.; Lakshamanakumar, P.; Kalaiyarasi, D. Aerobic rice-mitigating water stress for the future climate change. Intl. J. Agron. Plant. Prod. 2012, 3, 241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Djaman, K.; Mel, V.; Boye, A.; Diop, L.; Manneh, B.; El-Namaky, R.; Futakuchi, K. Rice genotype and fertilizer management for improving rice productivity under saline soil conditions. Paddy Water Environ. 2020, 18, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourgholam-Amiji, M.; Liaghat, A.; Ghameshlou, A.; Khoshravesh, M.; Waqas, M.M. Investigation of the yield and yield components of rice in shallow water table and saline. Big Data in Agriculture (BDA) 2020, 2, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delong, M.; Wieland, F. Changes in root hydraulic conductivity facilitate the overall hydraulic response of rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars to salt and osmotic stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 113, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Variable rains and flooding impact on rice harvest. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2008/04/01-1 (Accessed 20 April 2023).

- Peng, S.; Huang, J.; Sheehy, J.E.; Laza, R.C.; Visperas, R.M.; Zhong, X.; Centeno, S.G.; Khush, S.G.; Cassman, G. Rice yields decline with higher night temperature from global warming. Agric. Sci. 2004, 101, 9971–9975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saud, S.; Wang, D.; Fahad, S.; Alharby, H.F.; Bamagoos, A.A.; Mjrashi, A.; Alabdallah, N.M.; AlZahrani, S.S.; AbdElgawad, H.; Adnan, M.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Ali, S.; Hassan, S. Comprehensive Impacts of Climate Change on Rice Production and Adaptive Strategies in China. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13, 926059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1500323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuong, T.P.; Bouman, B.A. Rice production in water–scarce environments, In: Kijne JW, Barker R, Molden D (eds), Water productivity in agriculture: limits and opportunities for improvement. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, UK, 2003; pp. 53–67.

- Pimentel, D.; Berger, B.; Filiberto, D.; Newton, M.; Wolfe, B.; Karabinakis, E.; Clark, S.; Poon, E.; Abbett, E.; Nandagopal, S. Water resources: agricultural and environmental issues. Bioscience 2004, 54, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwire, D.; Saito, H.; Mugisha, M.; Nabunya, V. Water Productivity and Harvest Index Response of Paddy Rice with Alternate Wetting and Drying Practice for Adaptation to Climate Change. Water 2022, 14, 3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrijo, R.D.; Lundy, E.M.; Linquist, A.B. Rice yields and water use under alternate wetting and drying irrigation: A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2017, 203, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mote, K.; Rao, V.P.; Ramulu, V.; Kumar, K.M.; Uma Devi, M. Performance of rice (Oryza sativa (L.)) under AWD irrigation practice-A brief review. Pad. Water Environ. 2022, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y. Exploring options to grow rice using less water in northern China using a modelling approach I: field experiments and model evaluation, Agric. Water Manage. 2007, 88, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampayan, R.M.; Samoy-Pascual, K.C.; Sibayan, E.B.; Ella, V.B.; Jayag, O.P.; Cabangon, R.J.; Bouman, B.A.M. Effects of alternate wetting and drying (AWD) threshold level and plant seedling age on crop performance, water input, and water productivity of transplanted rice in central luzon, Philippines. Paddy Water Environ. 2015, 13, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z. Water efficient irrigation and environmentally sustainable irrigated rice production in China, International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage. https://www.icid.org/wat_mao.pdf, 2001 (Accessed 20 February 2023).

- Ishfaq, M.; Farooq, M.; Zulfiqar, U.; Hussain, S.; Anjum, S.A. Alternate wetting and drying: a water-saving and ecofriendly rice production system. Agr. Water Manage. 2020, 241, 106363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, B.A.M.; Tuong, T.P. Field water management to save water and increase its productivity in irrigated lowland rice. Agric. Water Manage. 2001, 49, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhir, Y.; Evangelista, G.; Fardnilo, J.; Humphreys, E.; Henry, A.; Fernandez, L. Establishment method effects on crop performance and water productivity of irrigated rice in the tropics. Field Crop. Res. 2014, 166, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antic-Mladenovic, S.; Frohne, T.; Kresovic, M.; Stark, H.J.; Tomic, Z.; Licina, V.; Rinklebe, J. Biogeochemistry of Ni and Pb in a periodically flooded arable soil: fractionation and redox-induced (im)mobilization. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 186, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Rui, J.; Mao, Y.; Yannarell, A.; Mackie, R. Dynamics of the bacterial community structure in the rhizosphere of a maize cultivar. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 68, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.F.; Lombi, E.; Stroud, J.L.; McGrath, S.P.; Zhao, F.J. Selenium speciation in soil and rice: influence of water management and Se fertilization. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 11837–11843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amundson, R.; Biardeau, L. Soil carbon sequestration is an elusive climate mitigation tool. PNAS 2018, 115, 11652–11656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyron, M.; Bertora, C.; Pelissetti, S.; Pullicino, S.D.; Celia, L.; Miniotti, E.; Romani, M.; Sacco, D. Greenhouse gas emissions as affected by different water management practices in temperate rice paddies. Agric. Ecosy. Environ. 2014, 232, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Q.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Yi, Q.; Wu, W. Mitigating methane emission via annual biochar amendment pyrolyzed with rice straw from the same paddy field. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 746, 141351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, N.; Steudle, E.; Hirasawa, T.; Lafitte, R. Hydraulic conductivity of rice roots. J. Exp. Bot. 2001, 52, 1835–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiller, V.; Lafitte, H.R.; Sperry, J.S. Hydraulic Properties of Rice and the Response of Gas Exchange to Water Stress. Plant Physiol. 2003, 132, 1698–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, R.M.; Stiller, V.; Ryan, M.G.; Sperry, J.S. Stomatal conductance and photosynthesis vary linearly with plant hydraulic conductance in ponderosa pine. Plant Cell Environ. 2001, 24, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanguilig, V.C.; Yambao, E.B.; Toole, J.C.; De Datta, S.K. Water stress effects on leaf elongation, leaf water potential transpiration and nutrient uptake of rice, maize, and soybean. Plant Soil. 1987, 103, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, S.; Mailapalli, R.D.; Raghuwanshi, S.N.; Das, S.B. Hydrus-1D model for simulating water flow through paddy soils under alternate wetting and drying irrigation practice. Paddy and Water Environ. 2019, 18, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T. Paddy Fields as Artificial and Temporal Wetland, Book Chapter 9, Irrigations in ecosystems. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.80581 (Accesed 20th, April, 2023). [CrossRef]

- Odhiambo, L.O.; Murty, V.V.V. Modeling water balance components in relation to field layout in lowland paddy fields. I. Model development. Agric. Water Manage. 1996, 30, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, B.A.M.; Lampayan, R.M.; Tuong, T.P. Water management in irrigated rice: Coping with Water scarcity. International Rice Research Institute, Los Banos, Philipines, 2007; 54 p.

- Maclean, J.L.; Dawe, D.; Hardy, B.; Hettel, G.P. Rice almanac: Source book for the most important economic activity on Earth (3rd ed.). International Rice Research Institute, Los Banos, Philippines 2002, 257p.

- Ranjan, R.; Pranav, P.K. Cost analysis of manual bund shaping in paddy fields: Economical and physiological. Res. Agric. Eng. 2021, 67, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Park, G.A.; Kwon, H.J. Evaluation of Paddy Water Storage Dynamics during Flood Period in South Korea. KSCE J. Civil Eng. 2007, 17, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suozhu, M.B.; Sayed, M.; Senge. The Impact of Various Environmental Changes Surrounding Paddy Field on Its Water Demand in Japan. Rev. Agric. Sci. 2020, 8, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huanga, H.C.; Liua, C.W.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.S. Analysis of percolation and seepage through paddy bunds. J. Hydrol. 2003, 284, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, L.H.; Dold, C. Water-Use Efficiency: Advances and Challenges in a Changing Climate. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, L.; Peng, S.; Chen, M.; Shah, F.; Huang, J.; Cui, K.; Xiang, J. Aerobic rice for water-saving agriculture: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabbal, D.F.; Bouman, B.A.M.; Bhuiyan, L.S.; Sibayan, B.E.; Sattar, A.M. On-farm strategies for reducing water input in irrigated rice; case studies in the Philippines. Agric. Water Manag. 2002, 56, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, B.; Suard, B.; Serraj, R.; Tardieu, F. Rice leaf growth and water potential are resilient to evaporative demand and soil water deficit once the effects of root system are neutralized. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 1256–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zuo, Q.; Wang, X.; Ma, W.; Jin, X.; Shi, J.; Ben-Gal, A. Characterizing roots and water uptake in a ground cover rice production system. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, N.; Ozawa, K.; Mochizuki, T. Genotypic differences in root hydraulic conductance of rice (Oryza sativa L.) in response to water regimes. Plant Soil 2009, 316, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Okami, M. Root growth dynamics and stomatal behavior of rice (Oryza sativa L.) grown under aerobic and flooded conditions. F. Crop. Res. 2010, 117, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.K.; Liu, C.W.; Huang, H.C. Analysis of water movement in paddy rice fields (II) simulation studies. J. Hydrol. 2002, 268, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukawa, K. The fluctuation of irrigation requirement for paddy fields. Proceedings, International Workhop, Asian Institute of Technology, Thailand, 1992; pp. 32–42.

- Prasanthkumar, K.; Saravanakumar, M.; Gunasekar, J.J. Water Management through Puddling Techniques. J Krishi Vigyan. 2019, 8, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, J.; Ahmed, P.; Baruah, N. Puddling and its effect on soil physical properties and growth of rice and post rice crops: A review. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2020, 9, 503–510. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, K.P.; De Datta, S.K. Effects of puddling on soil physical properties and processes, In. Soil Physics and Rice Book, International Rice Research Institute, Los Banos, Philippine, 1985; pp. 224–241.

- Wopereis, M.C.S.; Wosten, J.H.M.; Bouma, J.; Woodhead, T. Hydraulic resistance in puddled rice soils- measurement and effects on water-movement. Soil Tillage Res. 1992, 24, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salokhe, V.M.; Shirin, A.K.M. Effect of puddling on soil properties: a review, Proceedings of the international Workshop, Asian Institute of Technology, Bangkok, Thailand, 1992; pp. 276–285.

- Patil, M.D.; Das, B.S. Assessing the effect of puddling on preferential flow processes through under bund area of lowland rice field. Soil Tillage Res. 2013, 134, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wopereis, M.C.S.; Bouman, B.AM.; Kropff, M.J.; ten Berge, H.F.M.; Maligaya, A.R. Water use efficiency of flooded rice fields I: Validation of the soil-water balance model SA WAH. Agric. Water Manage. 1994, 26, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beven, K.J.; Germann, P. Macropores and water flow in soils revisited. Water Resour. Res. 2013, 49, 3071–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottinelli, N.; Zhou, H.; Boivin, P.; Zhang, Z.B.; Jouquet, P.; Hartmann, C.; Peng, X. Macropores generated during shrinkage in two paddy soils using X-ray micro-computed tomography. Geoderma 2016, 265, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuong, T.P.; Wopereis, M.C.S.; Marquez, J.A.; Kropff, M.J. Mechanisms and control of percolation losses in irrigated puddled rice fields. SSA J. 1994, 58, 1794–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, Y.; Yamada, R.; Oda, M.; Fujii, H.; Ito, O.; Kashiwagi, J. Effects of puddling on percolation and rice yields in rainfed lowland paddy cultivation: Case study in Khammouane province, central Laos. Agric. Sci. 2013, 4, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, K. Effect of puddling on rice physical: Softness of puddled soil on percolation. Proceedings, International Workshop of Soil and Water Engineering for Paddy Field Management, Asian Institute of Technology, Bangkok, Thailand, 1992; pp.220-231.

- Xu, B.; Shao, D.; Fang, L.; Yang, X.; Chen, S.; Gu, W. Modelling percolation and lateral seepage in a paddy field-bund landscape with a shallow groundwater table. Agric. Water Manage. 2019, 214, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.K.; De Datta, S.K. Response of wetland rice to percolation under tropical conditions. Proceedings, International workshop, Soil and Water Engineering for paddy field management, Asian Institute of Technology, Bangkok, Thailand, 1992, pp. 109–117.

- Wickham, T.H.; Singh, V.P. Water movement through wet soils, In: Soils and Rice. International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Los Banos, Philippines,1978; pp. 337–357.

- Hasegawa, S.; Thangaraj, M.; O’Toole, J.C. Root behavior: field and laboratory for rice and non-rice crops, In Soil Physics and Rice, International Rice Research Institute (IRR), Los Banos, Philippine, 1985, pp. 383–395.

- Mizutani, M. Positive studies on the formation of surplus water requirement (Part 3)-On the variable characteristic of net water requirement. Bulletin of the Faculty of Agriculture Mie University 1980, 61, 65–96. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, D.; Yamamoto, T.; Inoue, T.; Nagasawa, T. Change in water use by irrigation system from open channel to pipeline. Abstract, Meeting of the Japanese Society of Irrigation, Drainage and Rural Engineering, 2009, 436–437.

- Tuong, T.P. Technologies for efficient utilization of water in rice production, In: Advances in Rice Science (K. S. Lee, K. K. Jena, and K. L. Heong, Eds.), Proceedings, International Rice Science Conference, Korea, Soul, Korea, 2004, pp. 141–161.

- Tuong, T.P.; Bouman, B.A.M.; Mortimer, M. More rice, less water–integrated approaches for increasing water productivity in irrigated rice-based systems in Asia. Plant Prod. Sci. 2005, 8, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, D.; Tezara, W. Causes of decreased photosynthetic rate and metabolic capacity in water-deficient leaf cells: a critical evaluation of mechanisms and integration of processes. Annals of Botany 2009, 103, 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, M. Climatic Change and Rice Yield and Production in Japan during the Last 100 Years. Geographical Review of Japan 1993, 66, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley, J.I.; Nosaka, M.T.; Nakata, M.K.; Haque, M.S.; Inukai, Y. Rice Cultivation in Bangladesh: Present Scenario, Problems, and Prospects. J Intl Cooper Agric. Dev. 2016, 14, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samejima, H.; Katsura, K.; Kikuta, M.; Njinju, M.S.; Kimani, M.J.; Yamauchi, A.; Makiwara, D. Analysis of rice yield response to various cropping seasons to develop optimal cropping calendars in Mwea, Kenya. Plant Prod. Sci. 2020, 23, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayar, N.M. Origin of African Rice, Book Chapter, 5: In Origin and Phylogeny of Rices. Academic Press, Massachusetts, US, 2014; pp 117-168.

- Odhiambo, L.O.; Murty, V.V.N. Water Management in Paddy Fields in Relation to Paddy Field Layout. Proceedings, International Workshop on Soil and Water Engineering, For Paddy Field Management, Asian Institute of Technology, Bangkok, Thailand, 1992; pp. 377–384.

- Stoop, W.; UphoV, N.; Kassam, A. A review of agricultural research issues raised by the system of rice intensification (SRI) from Madagascar: Opportunities for improving farming systems for resource-poor farmers. Agric. Syst. 2002, 71, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkhout, E.; Glover, D.; Kuyvenhoven, A. On-farm impact of the System of Rice Intensification (SRI): Evidence and knowledge gaps. Agric. Sys. 2015, 132, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UphoV, N.; Fernandez, E.; Long-Pin, Y.; Jiming, P.; Sebastien, R.; Rabenanadrasana, J. Assessments of the system of rice intensification (SRI). Proceedings, International Conference, Sanya, China, 2002.

- Bwire, D.; Saito, H.; Okiria, O. Analysis of the impacts of irrigation practices and climate change on water availability for rice production: A case in Uganda. J. Arid Land Studies. 2022, S, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, B.A.M.; Humphreys, E.; Tuong, T.P.; Barker, R. Rice and Water. Advances for Agronomy 2007, 92, 187–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katambara, Z.; Kahimba, F.C.; Mahoo, H.F.; Mbungu, W.B.; Mhenga, F.; Reuben, P.; Maugo, M.; Nyarubamba, A. Adopting the system of rice intensification (SRI) in Tanzania: A review. Ag. Sci. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampayan, M.R.; Yadav, S.; Humphreys, E. Saving Water with Alternate Wetting Drying (AWD). International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). http://www.knowledgebank.irri.org/training/fact-sheets/water-management/saving-water-alternate-wetting-drying-awd, 2005 (Accessed 3rd February 2023).

- Balasubramanian, V.; Hill, J.E. Direct seeding of rice in Asia: emerging issues and strategic research needs for the 21st century, In. Book, Direct Seeding: research strategies and opportunities, IRRI, 2002; pp. 21–45.

- Cabangon, R.J.; Tuong, T.P.; Abdullah, N.B. Comparing water input and water productivity of transplanted and direct-seeded rice production systems. Agric. Water Manage. 2002, 57, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, F.J.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, M.S.; Toulmin, C. Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Sci. 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.E.; Funk, C.C. Food security under climate change. Scie. 2008, 319, 580–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dananjaya, P.K.V.S.; Shantha, A.A.; Patabendi, K.P.L.N. Impact of Climate Change and Variability on Paddy Cultivation in Sri Lanka, Systematic Review. Res. Square 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enete, A.; Amusa, T. Challenges of Agricultural Adaptation to Climate Change in Nigeria: A Synthesis from the Literature. Fact Reports Open Edi. J. 2016, 4, 0–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lemi, T.; Hailu, F. Effects of Climate Change Variability on Agricultural Productivity. Intl. J. Environ. Sci. Nat. Res. 2019, 17, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, G.G.; Tanga, Q.; Suna, S.; Huanga, S.; Zhanga, X.; Liu, X. Droughts in East Africa: Causes, impacts and resilience. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 193, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mall, R.K.; Aggarwal, P.K. Climate Change and Rice Yields in Diverse Agro-Environments of India. II: Effect of Uncertainties in Scenarios and Crop Models on Impact Assessment. Climatic Change. 2002, 52, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tao, F. Modeling the response of rice phenology to climate change and variability in different climatic zones: Comparisons of five models. Eur. J. Agron. 2013, 45, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; McCarl, B.; Chang, C.C. Climate change, sea level rise and rice: Global market implications. Climatic Change 2011, 110, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayugi, B.; Eresanya, O.E.; Onyango, O.A.; Ogou, F.K.; Okoro, C.E.; Okoye, O.C.; Anoruo, M.C.; Dike, N.V.; Ashiru, R.O.; Daramola, T.M.; Mumo, R.; Ongoma, V. Review of Meteorological Drought in Africa: Historical Trends, Impacts, Mitigation Measures, and Prospects. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2022, 179, 1365–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornall, J.; Betts, R.; Burk, E.; Clark, R.; Camp, J.; Willett, K.; Wilshire, A. Implications of climate change for agricultural productivity in the early twenty-first century. Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2973–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.N.M.R.; Zhang, J. Trends in rice research: 2030 and beyond. Food and Energy Sec. 2022, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRiSP (Global Rice Science Partnership), In. BooK: Rice almanac, 4th Edition.: International Rice Research Institute, Los Banos, Phillippines, 2013; 283 p.

- Roudier, P.; Sultan, B.; Quirion, P.; Berg, A. The impact of future climate change on West African crop yields: What does the recent literature say? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terdoo, F.; Feola, G. The Vulnerability of Rice Value Chains in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review. Climate 2016, 4, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabnakorn, S.; Maskey, S.; Suryadi, F.X.; De Fraiture, C. Rice yield in response to climate trends and drought index in the Mun River Basin, Thailand. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 621, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontgisa, C.; Schneidera, A.; Ozdogana, M.; Kucharika, C.; Trie, V.P.D.; Duce, H.D.; Schatzd, J. Climate change impacts on rice productivity in the Mekong River Delta. Appl. Geog. 2019, 102, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassman, R.; Nelson, G.C.; Peng, S.B.; Sumfleth, K.; Jagadish, S.V.K.; Hosen, Y.; Rosegrant, M.W. Rice and global climate change, In: Rice in the global economy: Strategic research and policy issues for food security, Los Banos, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), 2010; pp. 411–431.

- Wassmann, R.; Hien, N.X.; Hoanh, C.H.U.T.; Tuong, T.O.P. Sea level rise affecting the Vietnamese Mekong delta: Water elevation in the flood season and implications for rice production. Climatic Change 2004, 66, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Paris, T.; Bhandari, H. Household income dynamics and changes in gender roles in rice farming. Book Chap.: Rice in the global economy: Strategic research and policy issues for food security, Los Banos, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), 2010; pp. 93–111.

- Rowhani, P.; Lobell, D.B.; Linderman, M.; Ramankutty, N. Climate variability and crop production in Tanzania. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2011, 151, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kima, A.S.; Traore, S.; Wang, Y.M.; Chung, W.G. Multi-genes programing and local scale regression for analyzing rice yield response to climate factors using observed and downscaled data in Sahel. Agric. Water Manage. 2014, 146, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.S.; Florax, R.J.G.M.; Flores-Lagunes, A. Climate change and agricultural productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa: A spatial sample selection model. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2014, 41, 199–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwalieji, H.U.; Uzuegbunam, C.O. Effect of climate change on rice production in Anambra State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Ext. 2012, 16, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzadilla, A.; Zhu, T.; Rehdanz, K.; Tol, R.S.J.; Ringler, C. Climate change and agriculture: Impacts and adaptation options in South Africa. Water Res. Econ. 2014, 5, 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.A.; Rakotobe, Z.L.; Rao, N.S.; Dave, R.; Razafimahatratra, H.; Rabarijohn, R.H.; Rajaofara, H.; Mackinnon, J.L. Extreme vulnerability of smallholder farmers to agricultural risks and climate change in Madagascar. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochieng, J.; Kirimi, L.; Mathenge, M. Effects of climate variability and change on agricultural production: The case of small-scale farmers in Kenya. J. Life Sci. 2016, 77, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challinor, A.J.; Koehler, A.; Whitfield, S.; Das, B. Current warming will reduce yields unless maize breeding and seed systems adapt immediately. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 954–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Iizumi, T.; Hayashi, Y.; Yokozawa, M. Projecting climate change impacts both on rice quality and yield in Japan. J. Agric. Meteorol. 2011, 67, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, S.; Wada, H.; Matsue, Y. Countermeasures for heat damage in rice grain quality under climate change. Plant Prod. Sci. 2016, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masutomi, Y.; Takimoto, T.; Shimamura, M.; Manabe, T.; Arakawa, M.; Shibota, N.; Ooto, A.; Azuma, S.; Imai, Y.; Tamura, M. Rice grain quality degradation and economic loss due to global warming in Japan. Environ. Res. Commun. 2019, 1, 121003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triyanti, R.; Suryawati, S.H.; Wijaya, R.A.; Wardono, B.; Hafsaridewi, R. Assessment of the success factors influencing of rice-fish farming innovation village to support food security. Earth and Environ. Sci. 2021, 892, 012052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juma, C. The New Harvest: Agricultural Innovation in Africa, Book, Oxford University Press, 2011, 258p. Oxford, United Kingdom.

- Koide, J.; Fujimoto, N.; Okai, N.; Mostafa, H. Rice-fish Integration in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Challenges for Participatory Water Management, Review. JARQ 2015, 49, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaliarison, J.; National Aquaculture Sector Overview -Madagascar. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department. http://www.fao.org/fishery/countrysector/naso_madagascar/ (Accessed 20th February 2023).

- Halwart, M.; Gupta, M.V. Culture of fish in rice fields, Book, FAO & the World Fish Center, Penang, Malaysia, 2004, 83 p.

- Bakker, M.; Matsuno, Y.A. Framework for Valuing Ecological Services of Irrigation Water – A Case of an Irrigation-Wetland System in Sri Lanka, Irri. Drainage Sys. 2001, 15, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halls, A.S.; Hoggarth, D.D.; Debnath, K. Impacts of hydraulic engineering on the dynamics and production potential of floodplain fish populations in Bangladesh. Fisheries Manag. Ecol. 1999, 6, 261–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowing, J.W. A review of experience with aquaculture integration in large-scale irrigation systems, In Integrated Irrigation and Aquaculture in West Africa–Concepts, Practices and Potential, M. Halwart A. van Dam, (eds), FAO, Rome, 2006, 12, 135-150.

- Bene, C.; Arthur, R.; Norbury, H.; Allison, H.E.; Beveridge, M.; Bush, S.; Campling, L.; Leschen, W.; Little, D.; Squires, D.; Thilsted, H.S.; Troell, M.; Williams, M. Contribution of fisheries and aquaculture to food security and poverty reduction: assessing the current evidence. World Dev. 2016, 79, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K. Rice–fish farming systems in China: past, present, and future, In Rice–Fish Research and Development in Asia. ICLARM Conference, Proceedings, International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management, Manila, Philippines, 1992; pp.17-26.

- Brugere, C. A review of the development of integrated irrigation aquaculture (IIA), with special reference to West Africa. In Integrated Irrigation and Aquaculture in West Africa – Concepts, Practices and Potential, eds. Halwart, M. & van Dam, A., FRome, 2006, 4, 27-60.

- Miller, J. The potential for development of aquaculture and its integration with irrigation within the context of the FAO Special Programme for Food Security in the Sahel. Proceedings, Integrated Irrigation and Aquaculture in West Africa-Concepts, Practices and Potential, FAO, Rome, 2006; pp. 61–74.

- Peterson, J.; Kalende, M.; Sanni, D.; N’Gom, M. The potential for integrated irrigation aquaculture (IIA) in Mali. Proceedings, Integrated Irrigation and Aquaculture in West Africa-Concepts, Practices and Potential, FAO, Rome, Italy, 2006; pp. 79–93.

- Pengseng, J. On-farm trial with rice-fish cultivation in Nakhon Si Thammarat Southern Thailand Walailak. J. Sci. Technol. 2013, 10, 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J. Agricultural sustainability: concepts, principles, and evidence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 363, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welcomme, R.; Bartley, D. Current approaches to the enhancement of fisheries. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 1998, 5, 351–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohafkan, P.; Furtado, J. Traditional rice fish systems and globally indigenous agricultural heritage systems, in FAO Rice Conference. http://www.fao.org/3/y5682e/y5682e0b.htm, 2004 (Accessed 21 February 2023).

- Freed, S.; Barman, B.; Dubois, M.; Flor, R.J.; Funge-Smith, S.; Gregory, R.; Hadi, B.; Halwart, M.; Haque, M.; Jagadish, S.V.K.; Joffre, O.M.; Karim, M.; Kura, Y.; McCartney, M.; Mondal, M.; Nguyen, V.K.; Sinclair, F.; Stuart, A.M.; Tezzo, X.; Yadav, S.; Cohen, P.J. Maintaining Diversity of Integrated Rice and Fish Production Confers Adaptability of Food Systems to Global Change. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 576179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja, A. Grand challenges in marine ecosystems ecology. Front. Mar. Sci. 2014, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.G. The use of zoobenthos for the assessment of water quality in canals influenced by landfilling and agricultural activity. J. Vietnam. Environ. 2019, 11, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Lu, X.W.; X.-N. Li, Y.-F. Qin. The water purification effect of hydroponic biofilter method by artificial putting in zoobenthos. China Environ. Sci. 2007, 27, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Takayoshi, Y.; Tuan, L.M.; Kazunori, M.; Shigeki, Y. Alternate Wetting and Drying (AWD) Irrigation Technology Uptake in Rice Paddies of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam: Relationship between Local Conditions and the Practiced Technology. Asian and African Area Studies 2016, 15, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mote, K.; Rao, V.; Ramulu, P.V.; Kumar, V.K.; Devi, A.K.; Uma, M. Standardization of alternate wetting and drying (AWD) method of water management in lowland rice (oryza sativa l.) for upscaling in command outlets. Irrig. Drain. 2017, 67, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IWMI, Alternate wetting and dry in Rice Cultivation. In Climate Adaptation through Innovation. https://www.nibio.no/en/projects/climaadapt/technical-briefs/_/attachment/inline/89cf553b-6cd4-4235-871d 1fa499f41129:a1f11777f5dfe8add4e297b5197576918002f05b/IWMI%20Book%20Final_AWD.PDF, 2014 (Accessed 21 February 2023.

- Latif, A. A study on effectiveness of field water tube as a practical indicator to irrigate SRI Rice in Alternate wetting and drying irrigation management practice. M.Sc. Thesis, The Univ. of Tokyo. Japan, 2010.

- Mote, K.; Praveen Rao, V.; Ramulu, V.; Kumar, A.K. Effectiveness of field water tube for standardization of alternate wetting and drying method of water management in lowland rice. Irri. Drain. J. 2019, 68, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, V.J.; Wang, Y.M. Utilizing rainfall and alternate wetting and drying irrigation for high water productivity in irrigated lowland paddy rice in southern Taiwan. Plant Prod. Sci. 2017, 20, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampayan, R.M.; Palis, F.G.; Flor, R.B.; Bouman, B.A.M.; Quicho, E.D.; De Dios, J.L.; Espiritu, A.; Sibayan, E.B.; Vicmudo Lactaoen, A.T.; Soriano, J.B. Adoption and dissemination of “Safe Alternate Wetting and Drying” in pump irrigated rice areas in the Philippines, In: 60th International Executive Council Meeting of the International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage (ICID),5th Regional Conference, 2009.

- Abrol, I.P.; Bhumbla, E.R.; Meelu, O.P. Influence of salinity and alkalinity on properties and management of rice lands, In: Book: Soil Physics and Rice. International Rice Research Institute, Los Banos, Philippines, 1985, pp. 430.

- Yang, C.; Yang, L.; Yang, Y.; Ouyang, Z. Rice root growth and nutrient uptake influenced by organic manure in continuously and alternately flooded paddy soils. Agric. Water Manage. 2004, 70, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, T.; Shiraiwa, T.; Homma, K.; Katsura, K.; Maeda, S.; Yoshida, H. Can yields of lowland rice resume the increases that they showed in the 1980s? Plant Prod. Sci. 2005, 8, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhou, G.; Shimizu, H. Plant responses to drought and rewatering. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabangon, R.J.; Tuong, T.P.; Castillo, E.G.; Bao, L.X.; Lu, G.; Wang, G.; Cui, Y.; Bouman, B.A.M.; Li, Y.; Chen, C.D.; Wang, J.Z. Effect of irrigation method and N-fertilizer management on rice yield, water productivity and nutrient-use efficiencies in typical lowland rice conditions in China. Paddy Water Env. 2004, 2, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.X.; Huang, J.L.; Cui, K.H.; Nie, L.X.; Xiang, J.; Liu, X.J. Agronomic performance of high-yielding rice variety grown under alternate wetting and drying irrigation. Field Crops Res. 2012, 126, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Mahajan, B.S. Chauhan, J. Timsina, P.P. Singh, K. Sing. Crop performance and water and nitrogen use efficiencies in dry seeded rice in response to irrigation and fertilizer amounts in northwest India. Field Crop Res. 2012, 134, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabangon, R.J.; Castillo, E.G.; Tuong, T.P. Chlorophyll meter-based nitrogen management of rice grown under alternate wetting and drying irrigation. Field Crops Res. 2011, 121, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalley, L.L.; Linquist, B.; Kovacs, K.F.; Anders, M.M. The economic viability of alternate wetting and drying irrigation in Arkansas rice production. Agron. J. 2015, 107, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siopongco, J.D.L.C.; Wassmann, R.; Sander, B.O. Alternate wetting and drying in Philippine rice production: feasibility study for a clean development mechanism, IRRI Technical Bulletin No. 17. Los Banos, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute, 2013. 18 p.

- Hamoud, Y.A.; Guo; Wang, Z.; Chen, S.; Rasool, G. Effects of irrigation water regime, soil clay content and their combination on growth, yield, and water use efficiency of rice grown in South China. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2018, 11, 126–136. [Google Scholar]

- USDA, Soil Taxonomy Report: A Basic System of Soil Classification for Making and Interpreting Soil Surveys; USDA-NRCS: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2022-06/Soil%20Taxonomy.pdf (Accessed 27 February 2023).

- Haque, A.N.A.; Uddin, K.Md.; Sulaiman, F.M.; Amin, M.A.; Hossain, M.; Solaiman, M.Z.; Mosharrof, M. Biochar with Alternate Wetting and Drying Irrigation: A Potential Technique for Paddy Soil Management. Agric. 2021, 11, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinka, T.M.; Lascano, R.J. Review Paper: Challenges and Limitations in Studying the Shrink-Swell and Crack Dynamics of Vertisol Soils. Open J. Soil Sci. 2012, 2, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, T.; Gerke, H.H. Preferential flow patterns in paddy fields using a dye tracer. Vadose Zone J. 2007, 6, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Adachi, K. Numerical analysis of crack generation in saturated deformable soil under-row-planted vegetation. Geoderma. 2004, 120, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Shao, D.; Liu, H.; Yang, F.; Xiao, C.; Yang, H. Effects of alternate wetting and drying irrigation on percolation and nitrogen leaching in paddy fields. Paddy Water Environ. 2013, 11, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R.D.; Najm, M.R.A.; Rupp, D.E.; Lane, J.W.; Uribe, H.C.; Arumi, J.L.; Selker, J.S. Hillslope run-off thresholds with shrink-swell clay soils. Hydrol. Process. 2015, 29, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.W.; Cheng, S.W.; Yu, W.S.; Chen, S.K. Water infiltration rate in cracked paddy soil. Geoderma. 2003, 117, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, N.J. A review of non-equilibrium water flow and solute transport in soil macropores: principles, controlling factors and consequences for water quality. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2007, 58, 523–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, M.A.; Cotching, W.E.; Doyle, R.B.; Holz, G.; Lisson, S.; Mattern, K. Effect of antecedent soil moisture on preferential flow in a texture-contrast soil. J. Hydrol. 2011, 398, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidle, R.C.; Kardos, T.L.; Genuchten, Van.M.Th. Heavy metals transport model in a sludge-treated soil. J. Environ. Qual. 1977, 6, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.; Luxmoore, R. Estimating macroporosity in a forest watershed by use of a tension infiltrometer. SSA J. 1986, 50, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.; Luxmoore, R. Infiltration, macroporosity, and mesoporosity distributions on two forested watersheds. SSA J. 1999, 52, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, H.A.; Norton, G.J.; Salt, D.E.; Ebenhoeh, O.; Meharg, A.A.; Meharg, C.; Islam, M.R.; Sarma, R.N.; Dasgupta, T.; Ismail, A.M.; McNally, K.L.; Zhang, H.; Dodd, I.C.; Davies, W.J. Alternate wetting and drying irrigation for rice in Bangladesh: Is it sustainable and has plant breeding something to offer? Food and Energy Secur. 2013, 2, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.F.; Lombi, E.; Stroud, J.L.; McGrath, S.P.; Zhao, F.J. Selenium speciation in soil and rice: influence of water management and Se fertilization. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 11837–11843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X. Y.; McGrath, S.P.; Meharg, A.A.; Zhao, F.J. Growing rice aerobically markedly decreases arsenic accumulation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5574–5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, G.J.; Pinson, S.R.M.; Alexander, J.; Mckay, S.; Hansen, H.; Duan, G.L.; Islam, R.M.; Stroud, L.J.S.; Zhao, F.J.; McGrath, S.P.; Zhu, Y.G.; Lahner, B.; Yakubova, E.; Guerinot, L.M.; Tarpley, L.; Eizenga, C.G.; Salt, E.D.; Meharg, A.A.; Price, H.A. Variation in grain arsenic assessed in a diverse panel of rice (Oryza sativa) grown in multiple sites. New Phytol. 2012, 193, 650–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brammer, H.; Ravenscroft, P. Arsenic in groundwater: a threat to sustainable agriculture in South and South-East Asia. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 47–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pentrakova, L.; Su, K.; Pentrak, M.; Stucki, J.W. A review of microbial redox interactions with structural Fe in clay minerals. Clay Miner. 2013, 48, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiders, M.; Scherer, H. Fixation and release of ammonium in flooded rice soils as affected by redox potential. Eur. J. Agron. 1988, 8, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucu, M.A.; Said-Pullicino, D.; Maurino, V.; Bonifacio, E.; Romani, M.; Celi, L. Influence of redox conditions and rice straw incorporation on nitrogen availability in fertilized paddy soils. Biol. Fert. Soils 2014, 50, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Yadav, S.; Hellin, J.; Balie, J.; Bhandari, H.; Kumar, A.; Mondal, A.K. Why Technologies Often Fail to Scale: Policy and Market Failures behind Limited Scaling of Alternate Wetting and Drying in Rice in Bangladesh. Water 2020, 12, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejesus, R.M.; Palis, F.G.; Rodriguez, D.G.P.; Lampayan, R.M.; Bouman, B.A.M. Impact of the alternate wetting and drying (AWD) water-saving irrigation technique: evidence from rice producers in the Philippines. Food Policy. 2011, 36, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, G.J.D. The biogeochemistry of submerged soils, Book. Wiley, Chichester, England, 2004, 304P.

- Arao, T.; Kawasaki, A.; Baba, K.; Mori, S.; Matsumoto, S. Effects of water management on Cadmium and Arsenic accumulation and Dimethylarsinic acid concentrations in Japanese rice. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 9361–9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Huang, D.; Duan, H.; Tan, G.; Zhang, J. Alternate wetting and moderate drying increase grain yield and reduces cadmium accumulation in rice grains. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 1728–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meharg, A. A.; Norton, G.; Deacon, C.; Williams, P.; Adomako, E.E.; Price, A.; Zhu, Y.; Li, G.; Zhao, F.J.; McGrath, S.; Villada, A.; Sommella, A.; De Silva, P.M.C.S.; Brammer, H.; Dasgupta, T.; Islam, M.R. Variation in rice cadmium related to human exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 5613–5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas-Calle, N.L.; Whitfield, S.; Challinor, J.A. A Climate Smartness Index (CSI) Based on Greenhouse Gas Intensity and Water Productivity: Application to Irrigated Rice. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uprety, D.C.; Dhar, S.; Hongmin, D.; Kimball, B.A.; Garg, A.; Upadhyay, J. Technologies for Climate Change Mitigation - Agriculture Sector, UNEP Riso Centre on Energy, Climate and Sustainable Development. Department of Management Engineering. Technical University of Denmark (DTU), TNA Guidebook Series, 2012.

- IPCC, Summary for Policymakers, In: IPCC Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. https://archive.ipcc.ch/pdf/special-reports/srren/SRREN_FD_SPM_final.pdf, 2011, (Accessed 27 February 2023).

- Kumar, M.; Nandini, N. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Rice Fields of Bengaluru Urban District, India. Department of Environmental Science, Bangalore University, Jnana Bharathi campus, Bengaluru, Karnataka, INDIA. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Res. 2016, 2, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Runkle, B.; Suvocarev, K.; Reavis, C.; Reba, M.L. Carbon dynamics and the carbon balance of rice fields in the growing season, Abstract #B33G-2745, American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2018.

- Lal, R. Enhancing crop yields in the developing countries through restoration of the soil organic carbon pool in agricultural lands. L. Degrad. Dev. 2005, 17, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, P.R.; Harrington, L.; Jain, M.C.; Robertson, G.P. Longterm sustainability of the tropical and subtropical rice-wheat system: an environmental perspective, In Improving the Productivity and Sustainability of Rice-Wheat System: Issues and Impacts American Society of Agronomy Special Publication 65 ed J K Ladha et al. (Madison, WI: American Society of Agronomy), 2003, pp. 27–43.

- Livsey, J.; Katterer, T.; Vico, G.; Lyon, W.S.; Lindborg, R.; Scaini1, A.; Thi Da, T.; Manzon, S. Do alternative irrigation strategies for rice cultivation decrease water footprints at the cost of long-term soil health? Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 074011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.B.; Diep, T.T.; Fock, K.; Nguyen, S.T. Using the Internet of Things to promote alternate wetting and drying irrigation for rice in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.; Wassmann, R.; Sander, B.O.; Palao, L.K. Climate-Determined Suitability of the Water Saving Technology “Alternate Wetting and Drying” in Rice Systems: A Scalable Methodology demonstrated for a Province in the Philippines. PloS ONE 2015, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akpoti, K.; Dossou-Yovo, R.E.; Zwart, J.S.; Kiepe, P. The potential for expansion of irrigated rice under alternate wetting and drying in Burkina Faso. Agric. Water Manage. 2021, 247, s106758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C.; Richards, D.R.; Yeh, G.T.; Cheng, J.R.; Cheng, H.P.; Jones, N.L. FEMWATER: a three-dimensional finite element computer model for simulating density dependent flow and transport, Technical Report, HL-96, 1996.

- Li, Y.; Simunek, J.; Jing, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ni, L. Evaluation of water movement and Water Losses in a direct-seeded-rice field experiment using Hydrus-1D. Agric. Water Manage. 2014, 142, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Shao, D.; Liu, H. Simulating soil water regime in lowland paddy fields under different water managements using HYDRUS-1D. Agric. Water Manage. 2014, 132, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.D.; Idso, S.B.; Reginato, R.J.; Pinter, P.J. Canopy temperature as a crop water stress indicator. Water Resource Res. 1981, 17, 1133–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmak, S.; Haman, Z.D.; Bastug, R. Determination of crop water stress index for irrigation timing and yield estimation of corn. Agron. J. 2000, 92, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghvaeian, S.; Comas, L.; DeJonge, K.C.; Trout, T.J. Conventional and simplified canopy temperature indices predict water stress in sunflower. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 144, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katimbo, A.; Rudnick, R.D.; DeJonge, C.K.; Him Lo, T.; Qiao, X.; Franz, E.T.; Nakabuye, N.H.; Duan, J. Crop water stress index computation approaches and their sensitivity to soil water dynamics. Agric. Water Manage. 2022, 266, 107575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadal, N.; Shrestha, J.; Poudel, N.M.; Pokharel, B. A review on production status and growing environments of rice in Nepal and in the world. Archives Agric. Environ. Sci. 2019, 4, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khus, G.S. Terminology for Rice Growing environments. International rice Research Institute (IRRI), Los Banos, Philippines. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNAAR582.pdf, 1984 (Accessed 10 April 2023).

- Cultivation practices: Water Management, Tamil Nadu University, India. http://www.agritech.tnau.ac.in/expert_system/paddy/cultivationpractices3.html (Accessed 29 March 2023).

- Thakur, A.K.; Roychowdhury, S.; Kundu, D.K.; Singh, R. Evaluation of planting methods in irrigated rice. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2005, 50, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World rice production, Consumption and Stocks, USDA. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/reporthandler.ashx?reportId=681&templateId=7&format=html&fileName=World%20Rice%20Production,%20Consumption,%20and%20Stocks (Accessed 29 March 2023).

- Chapagain, T.; Yamaji, E. The effects of irrigation method, age of seedling and spacing on crop performance, productivity, and water-wise rice production in Japan. Paddy Water Env. 2010, 8, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.; Sheikh, H.B. Effect of alternate wetting and drying (AWD) irrigation for Boro rice cultivation in Bangladesh. Agric. Fores. Fisheries 2014, 3, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, H.V. Effect of various irrigation schedules on yield and water use in transplanted paddy. Mysore. J. Agric. Sci. 2000, 34, 222–226. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.M.; Wu, L.H.; Li, Y.S.; Sarkar, A.; Zhu, D.F.; Uphoff, N. Comparisons of yield, water use efficiency, and soil microbial biomass as affected by the System of Rice Intensification. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2010, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Zhang, J.H. Crop management techniques to enhance harvest index in rice. J Exp Bot 2010, 61, 3177–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mote, K. Standardization of Alternate Wetting and Drying (AWD) method of water management in low land rice (O. sativa L.) for up scaling in command outlets. Ph.D. Thesis. Submitted to Professor Jayashankar Telangana State Agriculture University, Hyderabad, Telangana, India, 2016.

- Omwenga, K.G.; Mati, B.M.; Home, P.G. Determination of the effect of the System of Rice Intensification (SRI) on rice yields and water saving in Mwea irrigation scheme, Kenya. J. Water Res. Prote. 2014, 6, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.L.C.; Rashid, M.A.; Paul, M. Refinement of Alternate wetting and drying irrigation method for rice cultivation. Bangladesh Rice J. 2013, 17, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashouri, M. Water use efficiency, irrigation management and nitrogen utilization in rice production in the north of Iran. APCBEE Proc. 2014, 8, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariam, O.; Anua, A.R. Effects of irrigation regime on irrigated rice. J. Trop. Agric. Food Sci. 2010, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Buresh, R.J. Nutrient best management practices for rice, maize, and wheat in Asia. World Congress of Soil Science, Brisbane, Australia, 1–6 August 2010.

- Siad, M.S.; Iacobellis, V.; Zdruli, P.; Gioia, A.; Stavi, I.; Hoogenboom, G. A review of coupled hydrologic and crop growth models. Agric. Water Manage. 2019, 224, 105746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimball, B.A. Carbon dioxide and agricultural yield: An assemblage and analysis of 430 prior observations. Agron. J. 1983, 75, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelet, D.; Gay, C.A. The impacts of climate change on rice yield: A comparison of four model performances. Ecological Modelling 1993, 65, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erda, L.; Wei, X.; Hui, J.; Yinlong, X.; Yue, L.; Liping, B.; Liyong, X. Climate change impacts on crop yield and quality with CO2 fertilization in China. Biol. Sci. 2005, 360, 2149–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerardeaux, E.; Giner, M.; Ramanantsoanirina, A.; Dusserre, J. Positive effects of climate change on rice in Madagascar. Agron. Sust. Dev. 2011, 32, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palis, F.G.; Cenas, P.A.; Bouman, B.A.M.; Lampayan, R.M.; Lactaoen, A.T.; Norte, T.M.; Vicmudo, V.R.; Hossain, M.; Castillo, G.T. A farmer participatory approach in the adaptation and adoption of controlled irrigation for saving water: a case study in Canarem, Victoria, Tarlac, Philippines. Philipp. J. Crop Sci. 2004, 29, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Emission by sector, Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/emissions-by-sector, 2023 (Accessed 3 May 2023).

- Bwire, D.; Saito, H. Influence of Alternate Wetting and Drying Irrigation Conditions on Soil Redox Potential, Water productivity and Agronomic Performance of Paddy Rice. Proceeding, 72nd meeting of Japanese Society of Irrigation, Drainage and Rural Engineering, Kanto Region, 2021, book of abstract, pp. 16–20.

| S/N | Major Categories | Sub-categories | Climate Description | Major Regions/countries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Irrigated | With favorable temperature. With low-temperature, tropical zone. With low temperature, temperate zone | Warm to hot—tropics (rice all seasons) and subtropics (double crop summer rice) | Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, the Philippines, south-eastern India, south-ern China, Bangladesh |

| Warm—tropics (higher altitudes) and subtropics (sole rice after winter crop) | South Asia hills, Indo-Gangetic Plain, central China | |||

| Temperate (summer rice after winter fallow, warm and humid) | Japan, Korean peninsula, north-eastern China, southern Brazil, southern USA | |||

| Temperate (summer rice after winter fallow, hot and dry) | Egypt, Iran, Italy, Spain, California (USA), Peru, south-eastern Australia | |||

| 2 | Rainfed Lowland | RFS, favorable RFS, drought prone. RFS, drought-and submergence-prone. RFS, submergence-prone RFM deep, waterlogged |

Tropics | Cambodia, North-East Thailand, eastern India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Nigeria |

| 3 | Upland | Favorable upland with LGS. Favorable upland with SGS. Unfavorable upland with LGS. Unfavorable upland with SGS. |

Tropics | South Asia, South-East Asia, Brazilian Cerrado, western Africa, East Africa; Uganda |

| 4 | Deep Water | Deep water Very deep water |

Tropics | River deltas of South Asia and South-East Asia, Mali |

| 5 | Tidal wetlands | TW with perennial fresh water. TW with seasonal or perennial saline water. TW with acid sulfate soils. TW with peat soils | Tropics | Vast areas near seacoasts and inland estuaries in Indonesia (Sumatra and Kalimantan), Vietnam and smaller areas in India, Bangladesh, and Thailand |

| Treatment | Descriptions | Bulk density, g/cc | |

| Bulk density | After Puddling | ||

| T1 | Cp | 1.492 | 1.333 |

| T2 | CP+HBP | 1.492 | 1.193 |

| T3 | Cp+W+HBP | 1.542 | 1.247 |

| T4 | VP+HBP | 1.425 | 1.305 |

| T5 | VP+W+HBP | 1.425 | 1.322 |

| T6 | CP+HBP+SFR | 1.500 | 1.300 |

| T7 | CP+W+HBP+SFR | 1.517 | 1.283 |

| T8 | CP+W+HBP+W+SFR | 1.385 | 1.252 |

| T9 | CP+HBP+W+SFR | 1.450 | 1.255 |

| T10 | VP+HBP+W+SFR | 1.433 | 1.330 |

| T11 | VP+W+HBP+SPR | 1.442 | 1.277 |

| T12 | VP+W+HBP+W+SFR | 1.433 | 1.383 |

| T13 | VP+HBP+W+SFR | 1.492 | 1.217 |

| Treatment | Puddler Type for treatment description | Hydraulic Conductivity | Percolation Loss | |||

| Total cm/hr | % reduction over control | Total cm | % reduction over control | |||

| T1 | Disc harrow | 0.052 | 74.44 | 111.7 | 25.56 | |

| T2 | Angular bladed puddler | 0.031 | 84.87 | 066.1 | 15.13 | |

| T3 | Deshi plough | 0.098 | 51.40 | 212.3 | 48.60 | |

| T4 | Moldboard plough | 0.075 | 63.17 | 160.9 | 36.83 | |

| T5 | Control (No puddling) | 0.203 | - | 436.9 | - | |

| S/No | Stages of growth | Water requirement (mm) | Percentage of total water requirement (%) |

| 1 | Nursery | 40 | 3.22 |

| 2 | Main field preparation | 200 | 16.12 |

| 3 | Planting to panicle initiation | 458 | 37.00 |

| 4 | Panicle initiation to flowering | 417 | 33.66 |

| 5 | Flowering to maturity | 125 | 10.00 |

| Direct Seeding Systems | Seed Condition | Seedbed condition and environment | Seeding pattern | Where practiced |

| Direct-dry seeding | Dry | Dry soil, mostly aerobic | Broadcasting; drillingor sowing in rows | Mostly in rainfed areas and in irrigated areas with precise water control |

| Direct-wet seeding | Pre-germinated | Puddled soil, may be aerobic or anaerobic | Various | Mostly in irrigated areas with good drainage |

| Water seeding | Dry or pre-germinated | Standing water, mostly anaerobic | Broadcasting on standing water | In irrigated areas with good land levelling and in areas with red rice problem |

| Country | 2018/19 | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | 2022/23 |

| China | 148,490 | 146,730 | 148,300 | 148,990 | 145,946 |

| India | 116,484 | 118,870 | 124,368 | 129,471 | 132,000 |

| Bangladesh | 34,909 | 35,850 | 34,600 | 35,850 | 35,850 |

| Indonesia | 34,200 | 34,700 | 34,500 | 34,400 | 34,600 |

| Vietnam | 27,344 | 27,100 | 27,381 | 26,769 | 27,000 |

| Thailand | 20,340 | 17,655 | 18,863 | 19,878 | 20,200 |

| Burma | 13,200 | 12,650 | 12,600 | 12,352 | 12,500 |

| Philippines | 11,732 | 11,927 | 12,416 | 12,540 | 12,411 |

| Japan | 7,657 | 7,611 | 7,570 | 7,636 | 7,450 |

| Brazil | 7,140 | 7,602 | 8,001 | 7,337 | 6,936 |

| Pakistan | 7,202 | 7,206 | 8,420 | 9,323 | 6,600 |

| Cambodia | 5,742 | 5,740 | 5,739 | 5,771 | 5,933 |

| Nigeria | 5,294 | 5,314 | 5,148 | 5,255 | 5,040 |

| Korea South | 3,868 | 3,744 | 3,507 | 3,882 | 3,764 |

| Nepal | 3,736 | 3,697 | 3,744 | 3,417 | 3,654 |

| Others | 43,780 | 46,667 | 46,939 | 44,898 | 44,854 |

| Subtotal | 491,118 | 493,063 | 502,096 | 507,769 | 504,738 |

| World Total | 498,225 | 498,940 | 509,320 | 513,852 | 509,830 |

| S/N | Component | Details | Authors |

| 1 | Wp, WUE, Water Saving | Higher Wp (1.74 g L−1) in AWD compared to CF (1.23 g L−1) | [205] |

| WUE (85.55 (kg ha−1 cm) in AWD with quite a large water saving (15 cm) compared to continuous submergence | [206] | ||

| Water saving of 15–20% with AWD without a significant impact on yield | [148] | ||

| A 26.34 % reduction in water use and only a 6.40% reduction in grain yield compared to the CF. Observed up to 36 % water saving in AWD conditions | [13,223] | ||

| Water application once in 7 days consumed the lowest amount of water (80.30 cm) and saved 41% water | [207] | ||

| Water savings in AWD by 40–70%, 20–50% compared to CF | [208] | ||

| AWD irrigation regimes consumed water to the 50.9–82.1% of CF (1390 mm), with water saving (13.8–36.4%) and water productivity (1.148 to 1.266 kg m−3) | [138] | ||

| AWD improves WUE and yields with 5, 7 and 10 days of irrigation interval | [140,209] | ||

| 2 | Yield components | Average grain yield of 5.8–7.4 t ha−1 with AWD irrigation methods and 7.5–7.6 t ha−1 with continuous submergence | [138,210] |

| Soil drying period of 8 days gave the highest yield (7.13 t ha−1) compared to CF (4.87 t ha−1) in Kenya | [211] | ||

| Highest grain yield (5.9—6.2 t ha−1) with irrigation schedule when water table dropped to 15 cm below ground level in Bangladesh | [212] | ||

| Water application intervals of 5 and 8 days with CF produced statically the same grain yield. (7342, 7079 and 7159 kg ha−1, respectively) | [213] | ||

| Grain yield was higher in saturated condition (7.6 t ha−1) compared to CF (7.1 t ha−1) in Malaysia | [214] | ||

| Application of safe AWD levels did not result in loss of rice yield | [215] | ||

| Increases rice yield by 10% with AWD | [180] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).