Submitted:

26 November 2023

Posted:

27 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material Properties of Ice

2.1. Constitutive Equations for Ice Elasto-Plastic Behavior

2.2. Yield Criteria of Ice

- (1)

- Crushable foam model

- (2)

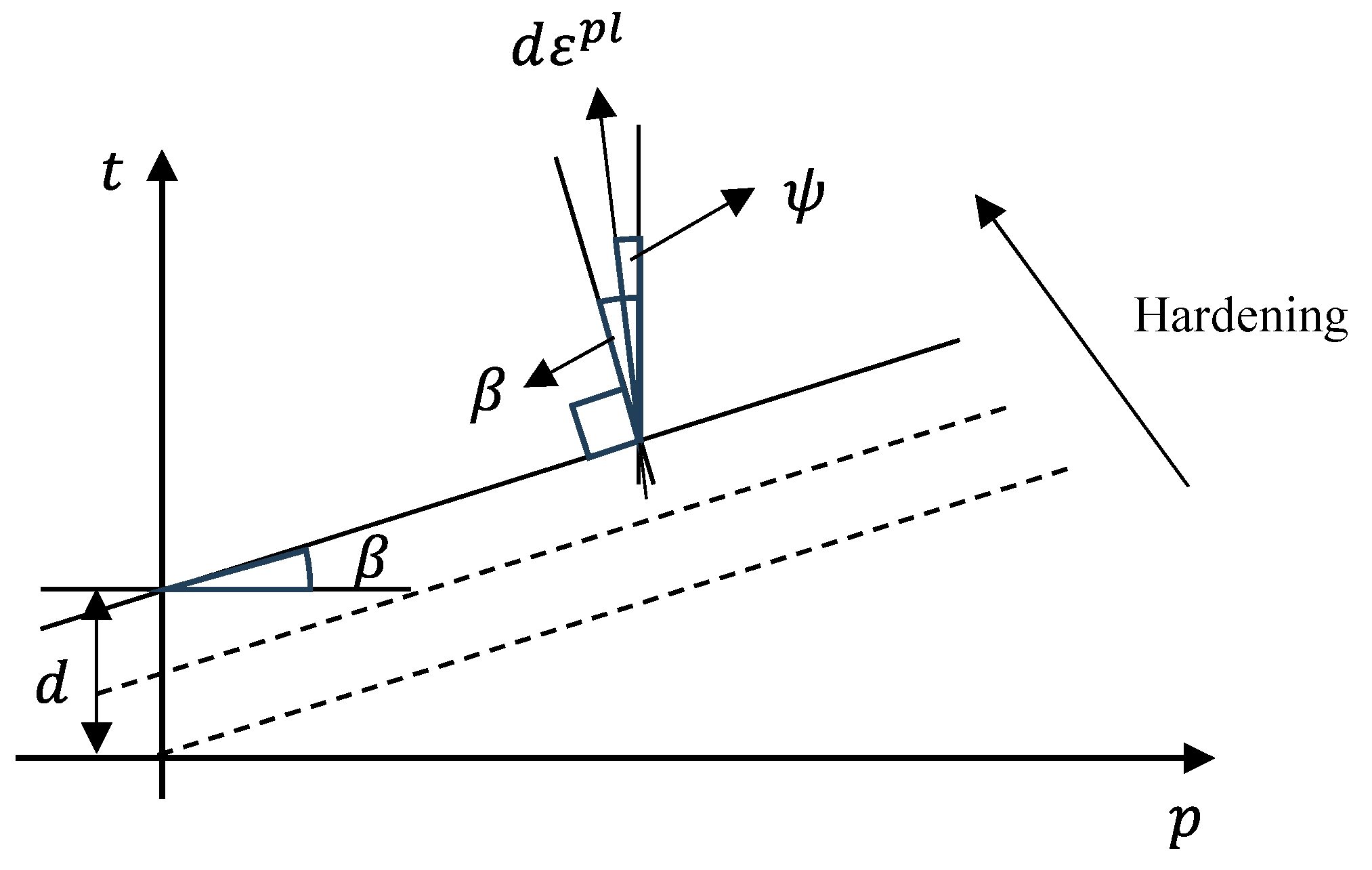

- Drucker-Prager model

- (3)

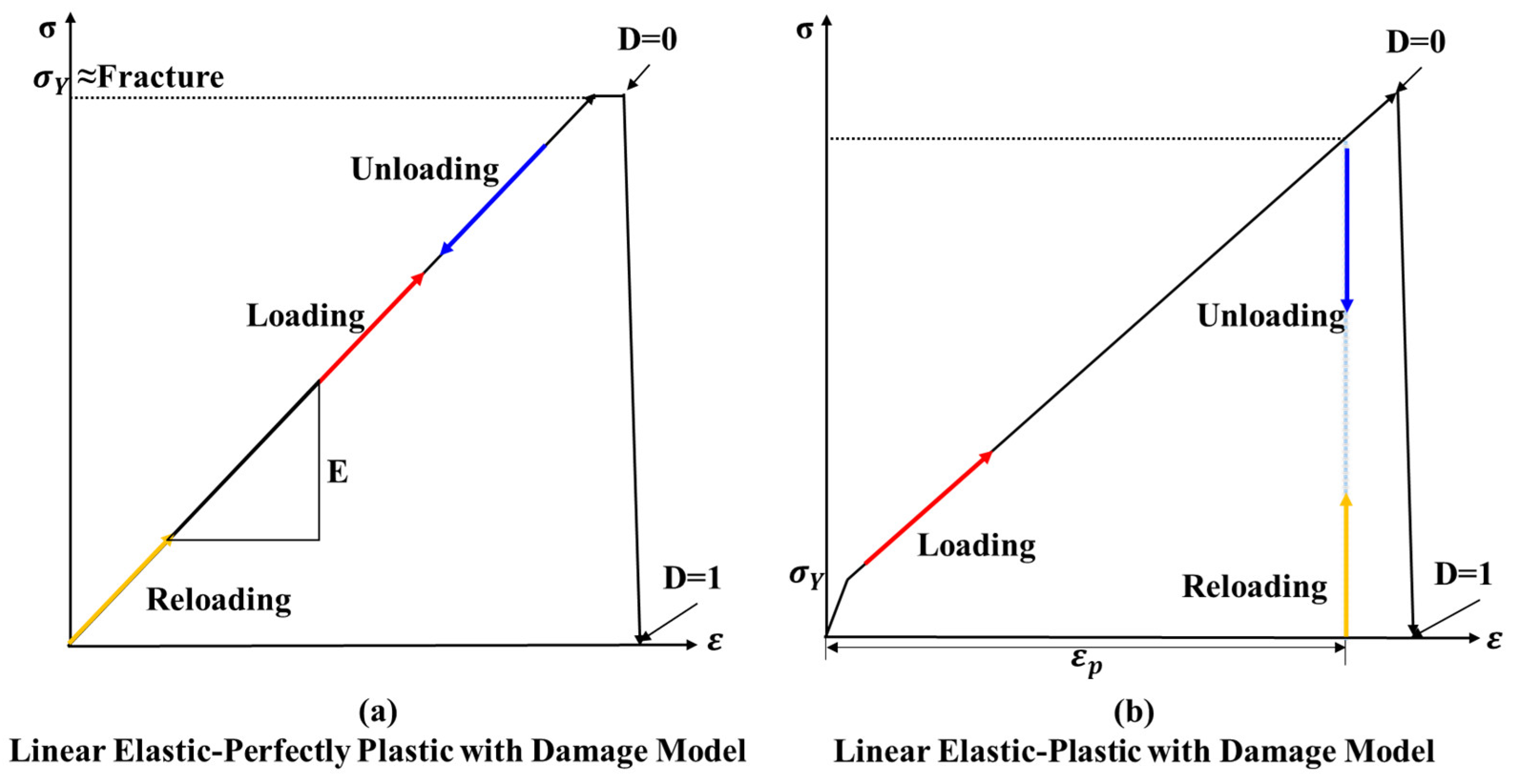

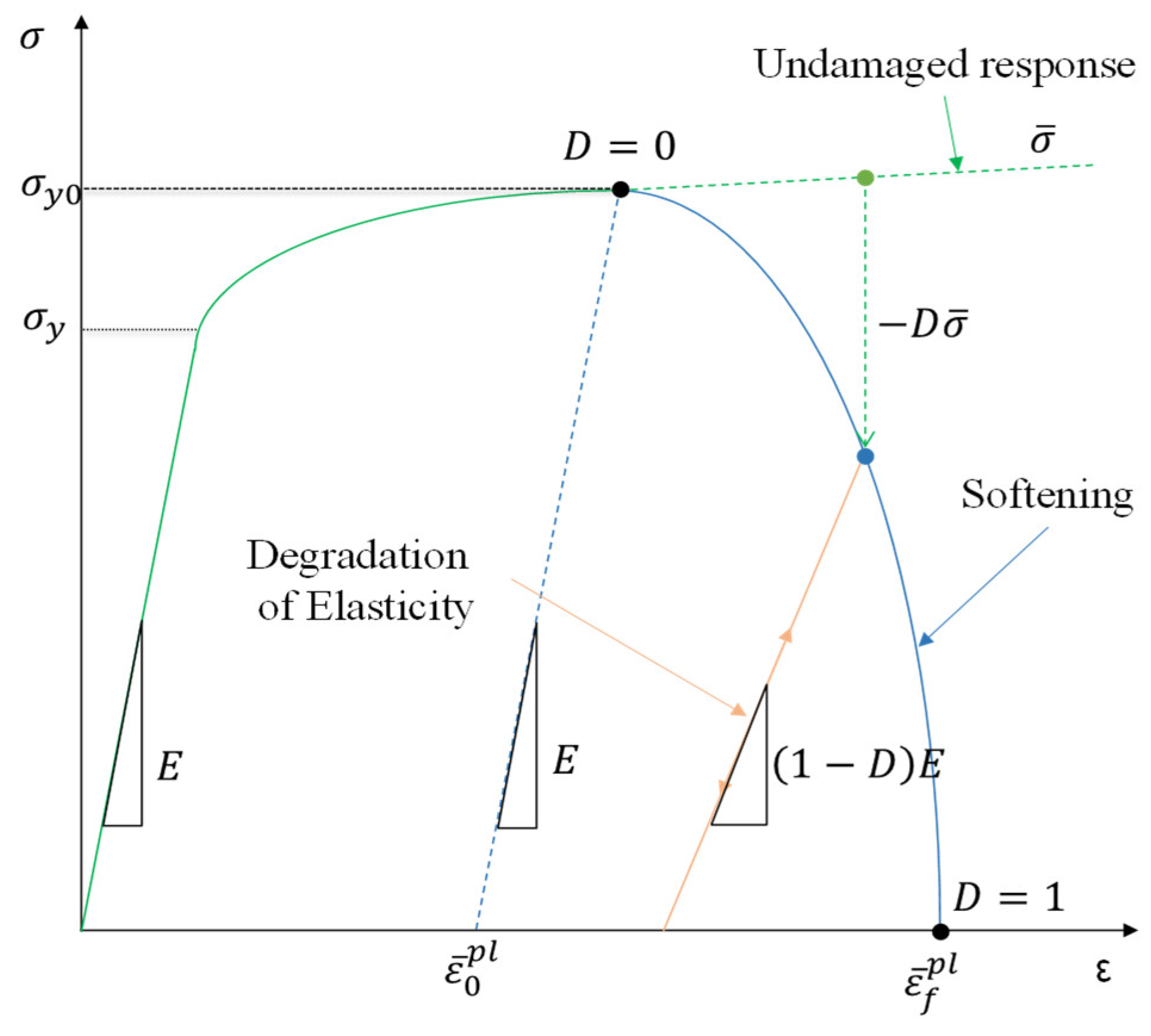

- Ductile damage model

- Damage Initiation (D=0): The fracture model identifies the commencement of damage when the material reaches its ultimate strength. Damage initiation is typically associated with the equivalent plastic strain ().

- Damage Evolution (0<D<1): In Figure 4, the dotted line represents the undamaged response, indicating the material’s pure plastic behavior without the influence of a damage model. The solid line, labeled as “softening,” depicts the behavior of the material once it has sustained damage. Following damage initiation (D=0), the model simulates the progression of damage. As the damage evolves, the material’s stiffness starts to decrease, and the damage variable (D) increases.

- Fracture (D=1): When the damage variable (D) reaches 1, signifying the completion of the damage progression, the material’s internal cohesive strength is completely lost. At this point, material fracture occurs, and bonded elements may separate or be removed (i.e., element deletion).

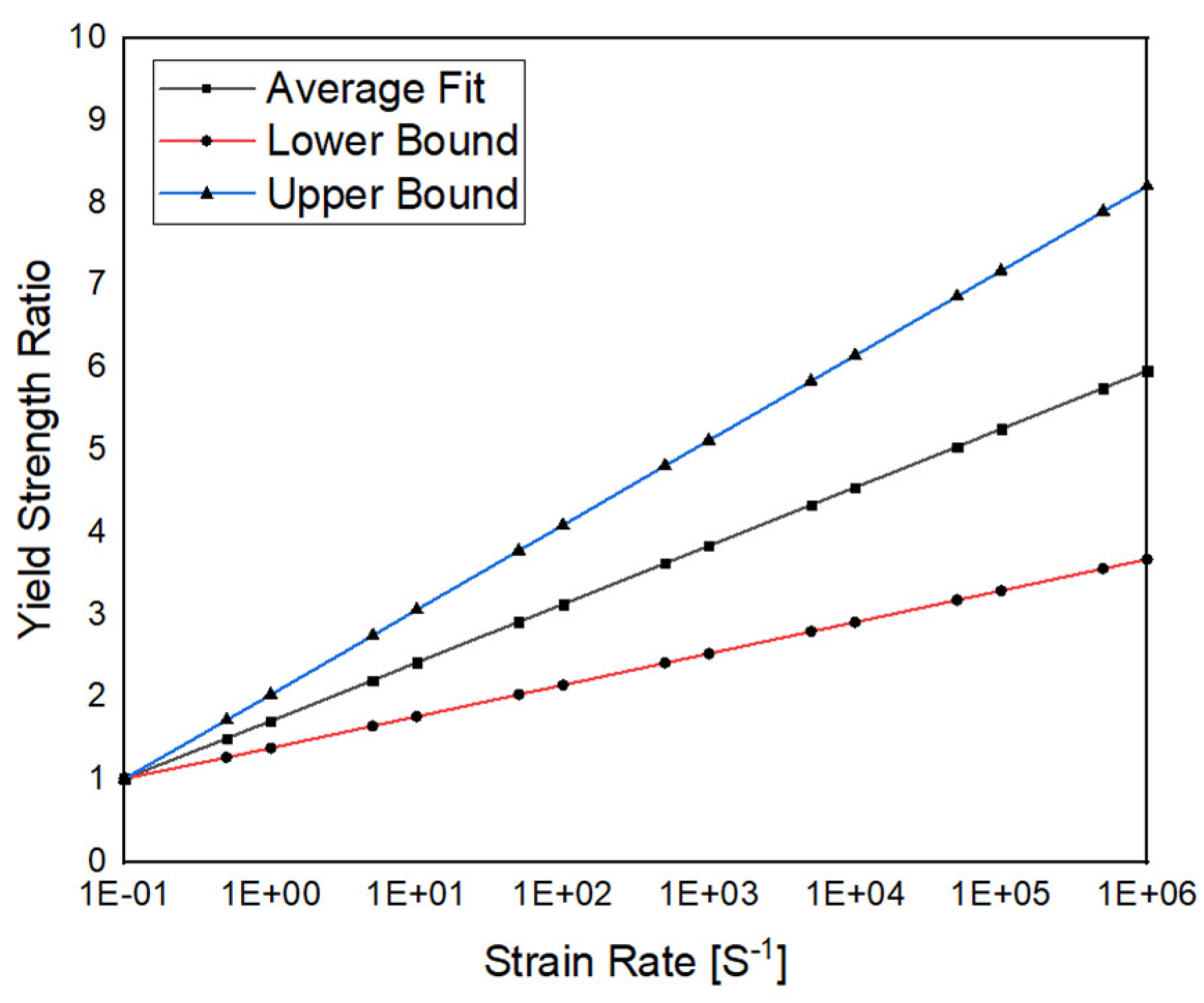

2.3. Strain Rate Dependency of Ice: Yield Strength Ratio

3. Ice material Calibration

- Plastic deformation relationships: Models such as the linear elastic-perfectly plastic (LEPP) and linear elastic-plastic (LEP) models define how materials behave when they exceed the elastic limit. While the LEPP model assumes that no deformation occurs beyond the yield point, the LEP model describes post-yield hardening or softening. These material plastic properties are applied to the analyses to verify their results.

- Yield criteria: The crushable foam (CF) and Drucker-Prager (DP) models define the conditions under which materials reach yield. The CF model simulates the collapse of cellular materials under compression, whereas the DP model models the yield of pressure-dependent materials. Given the sensitivity of ice to pressure and density, the appropriateness of these conditions was investigated.

- Strain rate dependence: In dynamic events such as collisions, strain rate affects the yield stress and failure modes of the material. Results are analyzed based on whether or not strain rate dependence is considered.

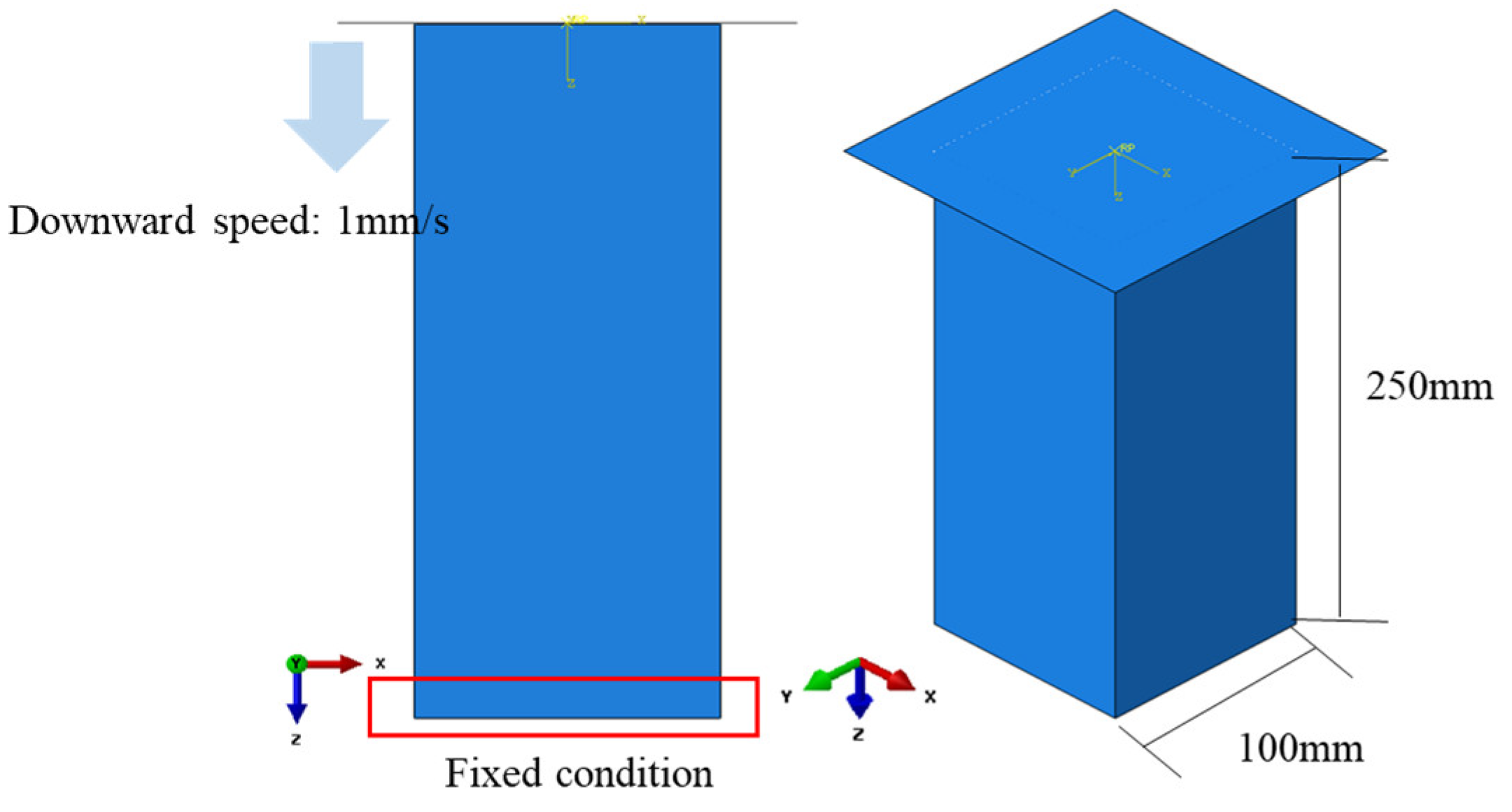

3.1. Determination of Material Model Constants

- LEPP model: This model requires the determination of two fundamental material constants, Young’s modulus () and the yield stress (). Young’s modulus is conventionally obtained from tensile tests, whereas the yield stress is the stress point at which the material begins to undergo plastic deformation.

- LEP model: Similar to LEPP, the LEP model requires the determination of Young’s modulus () and yield stress (). In addition, it requires consideration of additional constants associated with the hardening model and the hardening coefficient or plastic flow rule.

- CF model: This model requires the definition of material constants that govern the compressive behavior of foams. Key constants include density, initial strength (), and hardening coefficient. The determination of these constants is facilitated by the analysis of stress-strain curves derived from compression tests on specimens.

- DP model: The DP model requires a set of constants related to the angle of internal friction (β), material cohesion (d), drag parameters such as the dilatancy angle (ψ), and constants related to the hardening rule. Typically, these constants are obtained from triaxial compression tests and should be considered in conjunction with stress paths.

- LEPP model: The apparent elastic modulus was assumed to be 0.14 GPa. The yield stresses for the CF and DP models were set at 4.8 MPa and 3 MPa respectively. The material damage model parameters included a failure strain of 1.0 × 10-4 and an energy release rate of 15.0 J.

- LEP model: The elastic modulus, influenced by stress and strain rate, was set to 9 GPa. Hardening constants for this model are detailed in Table 4 for both the CF and DP models, and failure strains were designated as 0.019 and 0.025, respectively, with a damage evolution energy of 15.0 J.

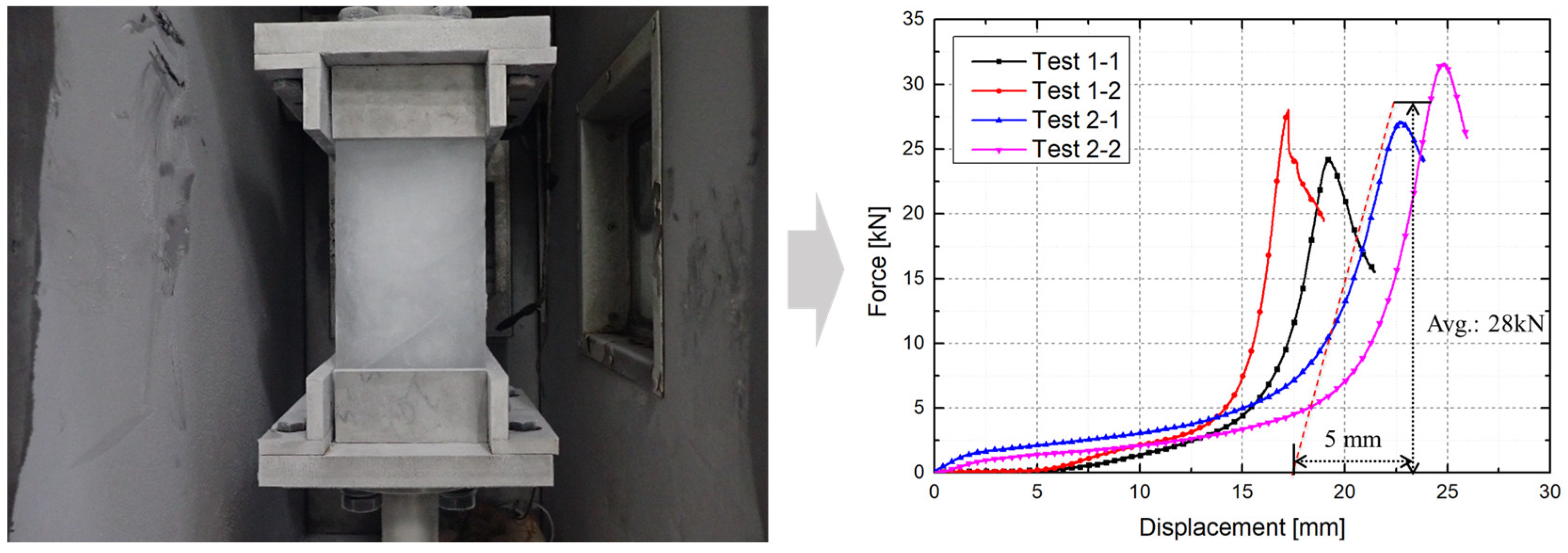

3.2. Finite Element Analysis Simulating Ice Compression Experiments

- Contact conditions: The lower surface of the ice specimen was fixed in place. A hard node-to-surface contact condition was applied to the upper surface, which came into contact with the rigid compression plate. This setup was crucial to prevent any penetration between the specimen and the plate.

- Compression conditions: The rigid compression plate was set to move at a speed of 1.0 mm/s, mirroring the experimental conditions. This movement applied a controlled displacement to the specimen, thereby replicating the actual test conditions in the numerical model.

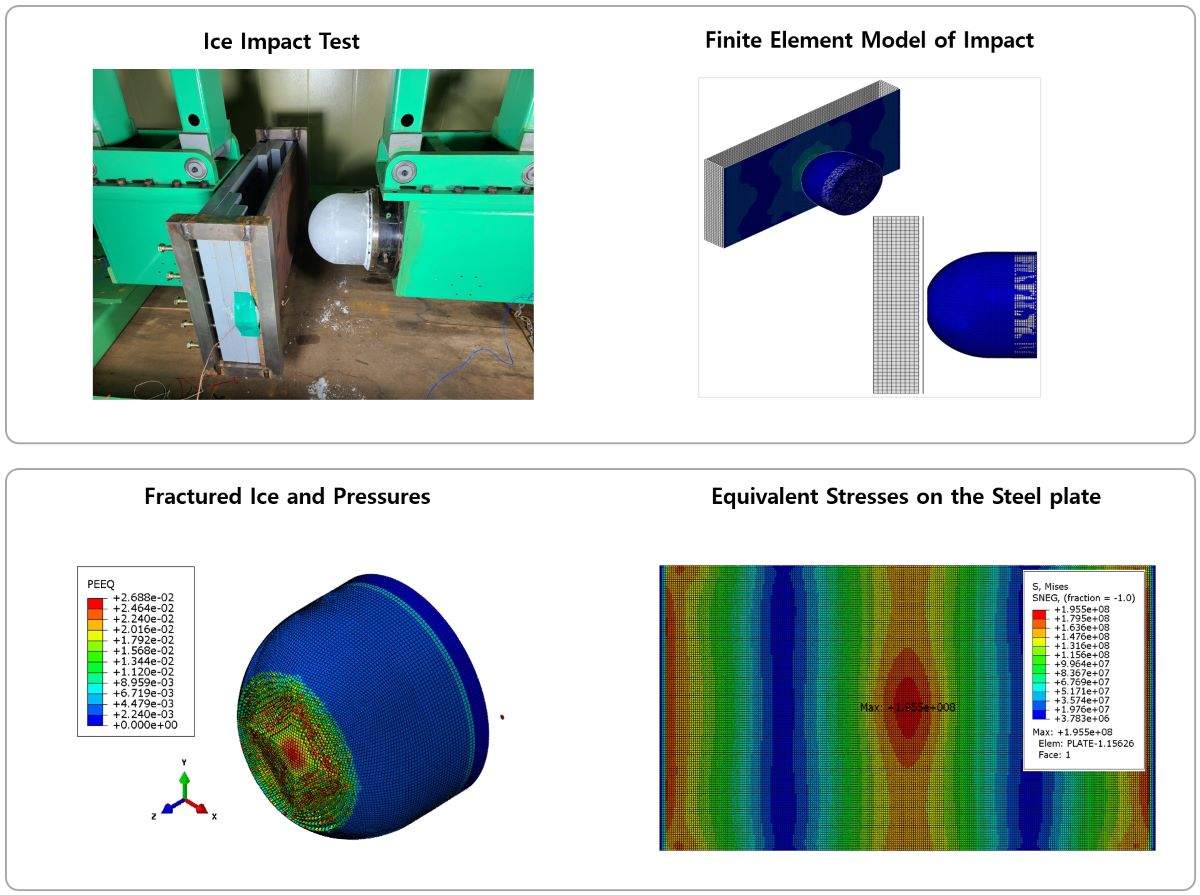

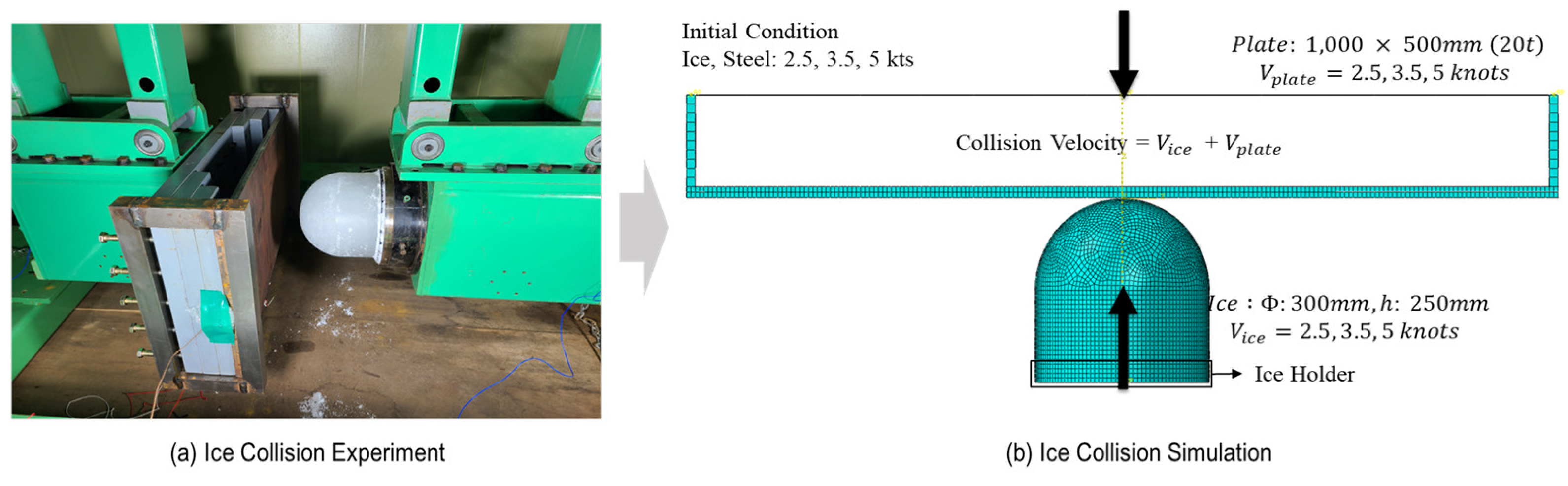

4. Simulation Model for the Ice-Structure Collision Experiment

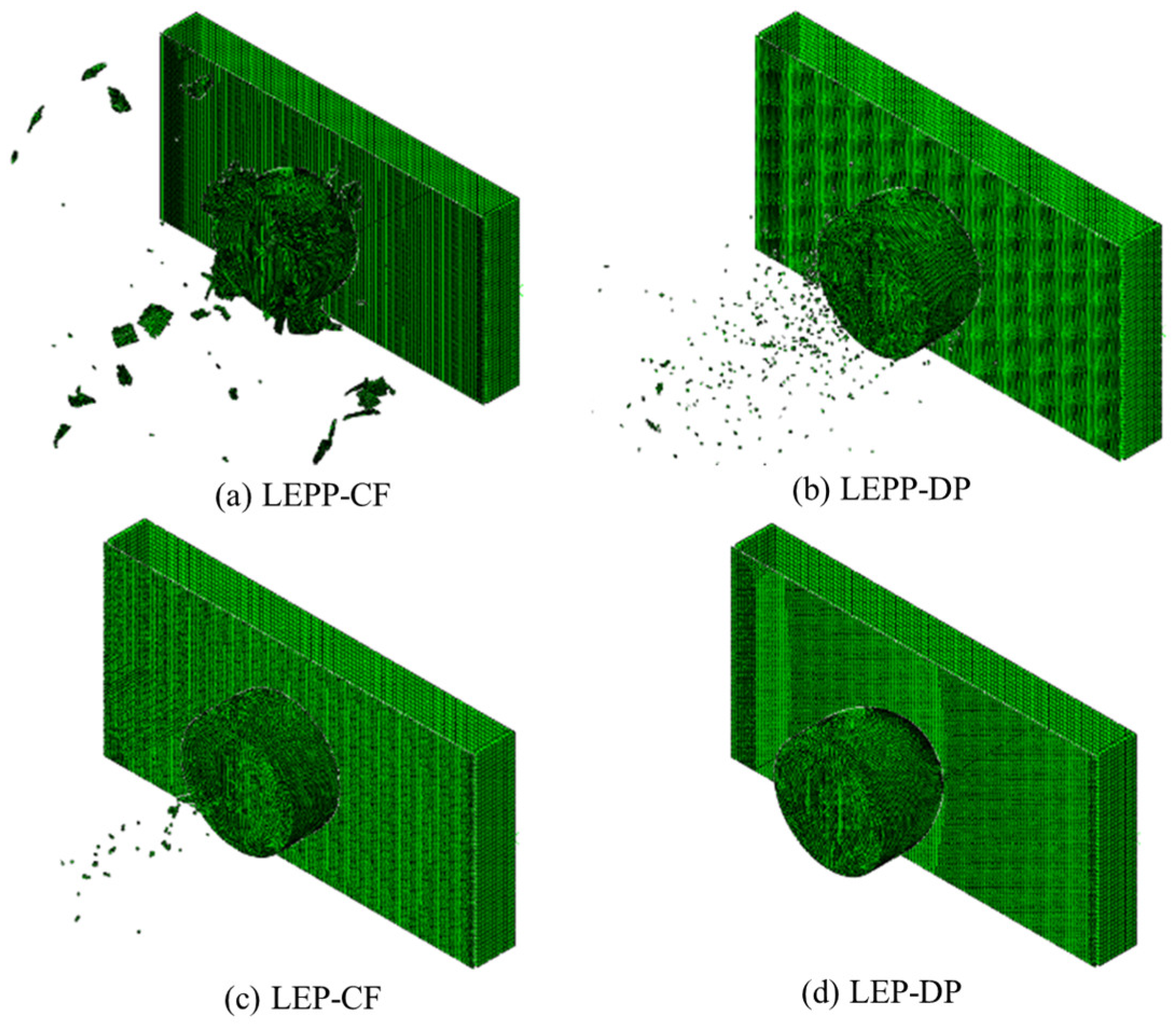

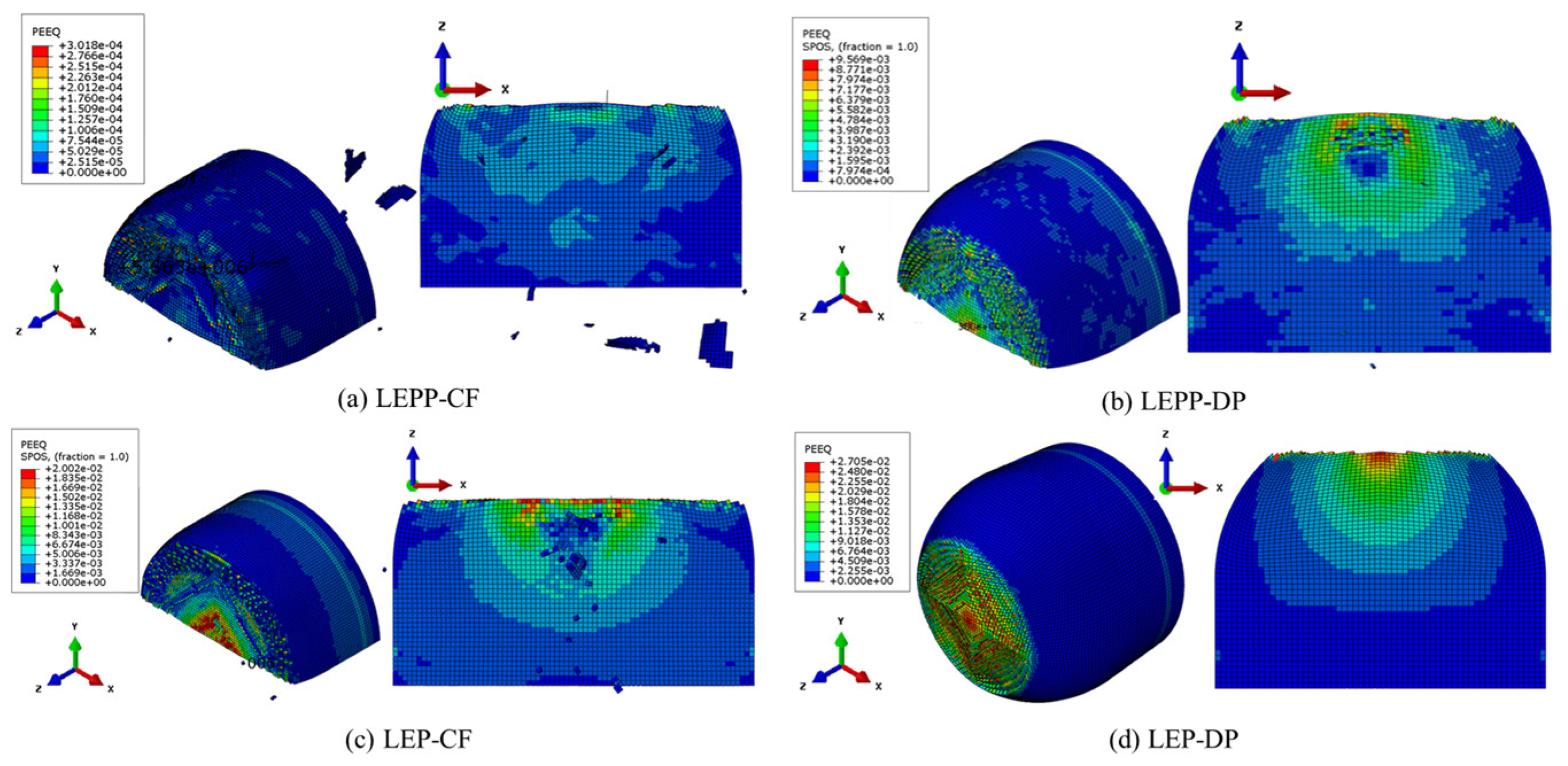

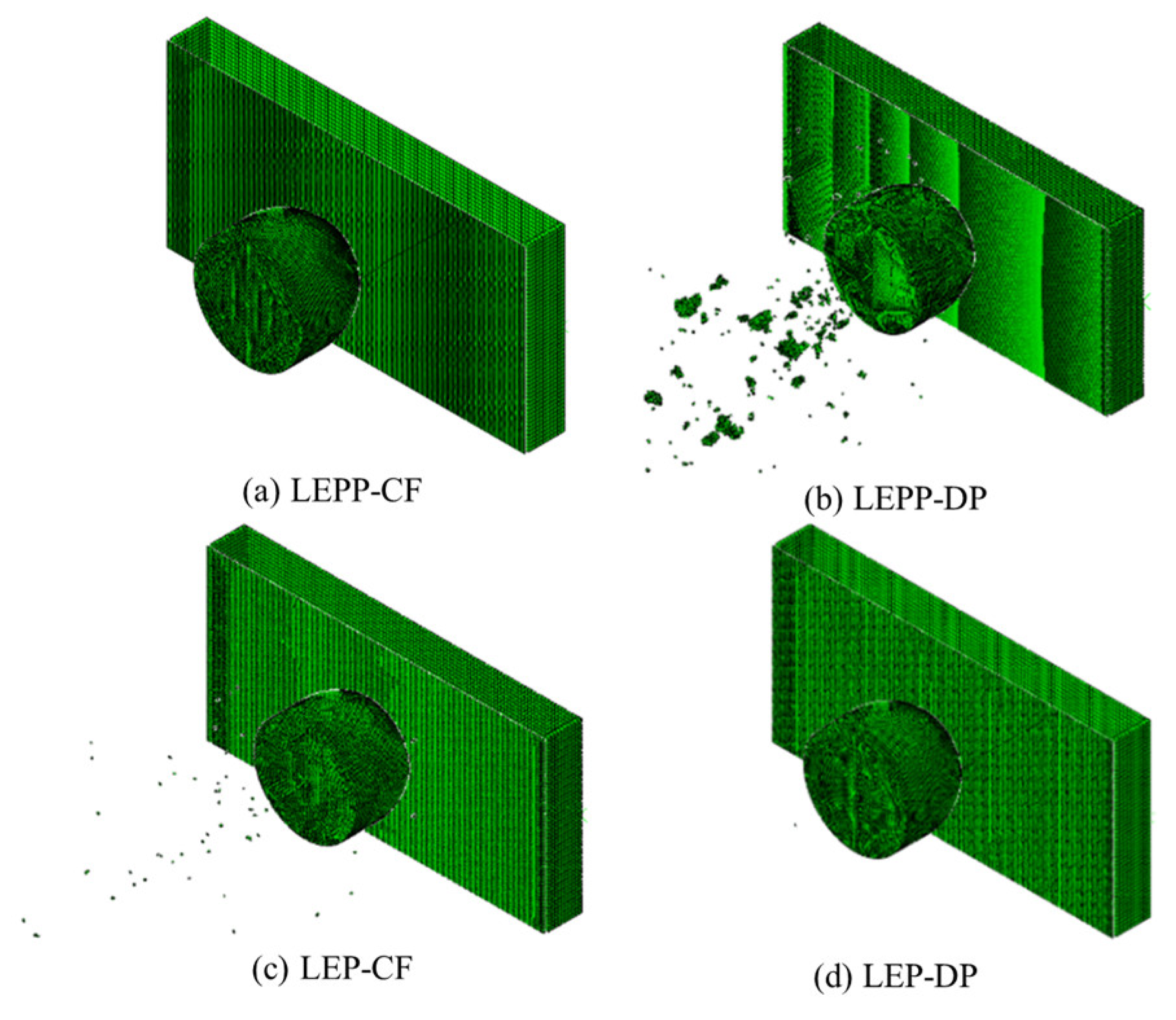

- Ice yield criteria: The CF and DP models were used to model the yielding and failure behavior of ice, as described in Section 2.1.

- Contact conditions: Contact conditions were established to account for the interaction between the two objects and to calculate the load transferred from the ice to the structure. For the contact between ice elements and plates, hard contact and tie conditions are applied.

- Element with reduced integration: Reduced integration was used to establish the stiffness matrix to enhance the computational efficiency, along with the selection of the hourglass control.

- Time increment: In the explicit finite element analysis, the determination of the time increment (△t) is crucial for achieving both accuracy and computational efficiency. In our study, the time increment for explicit integration was calculated using the following formula: , where represents the size of the smallest element within mesh. Moreover, represents the material’s dilatational wave speed, which is a function of the material’s mechanical properties and is calculated using the formula: , where E denotes the elastic modulus of the material, and ρ denotes the density.

4.1. Overview of the Ice-Structural Collision Simulation Model

4.2. Collision Analysis Reflecting Quasi-Static Compressed Material Model

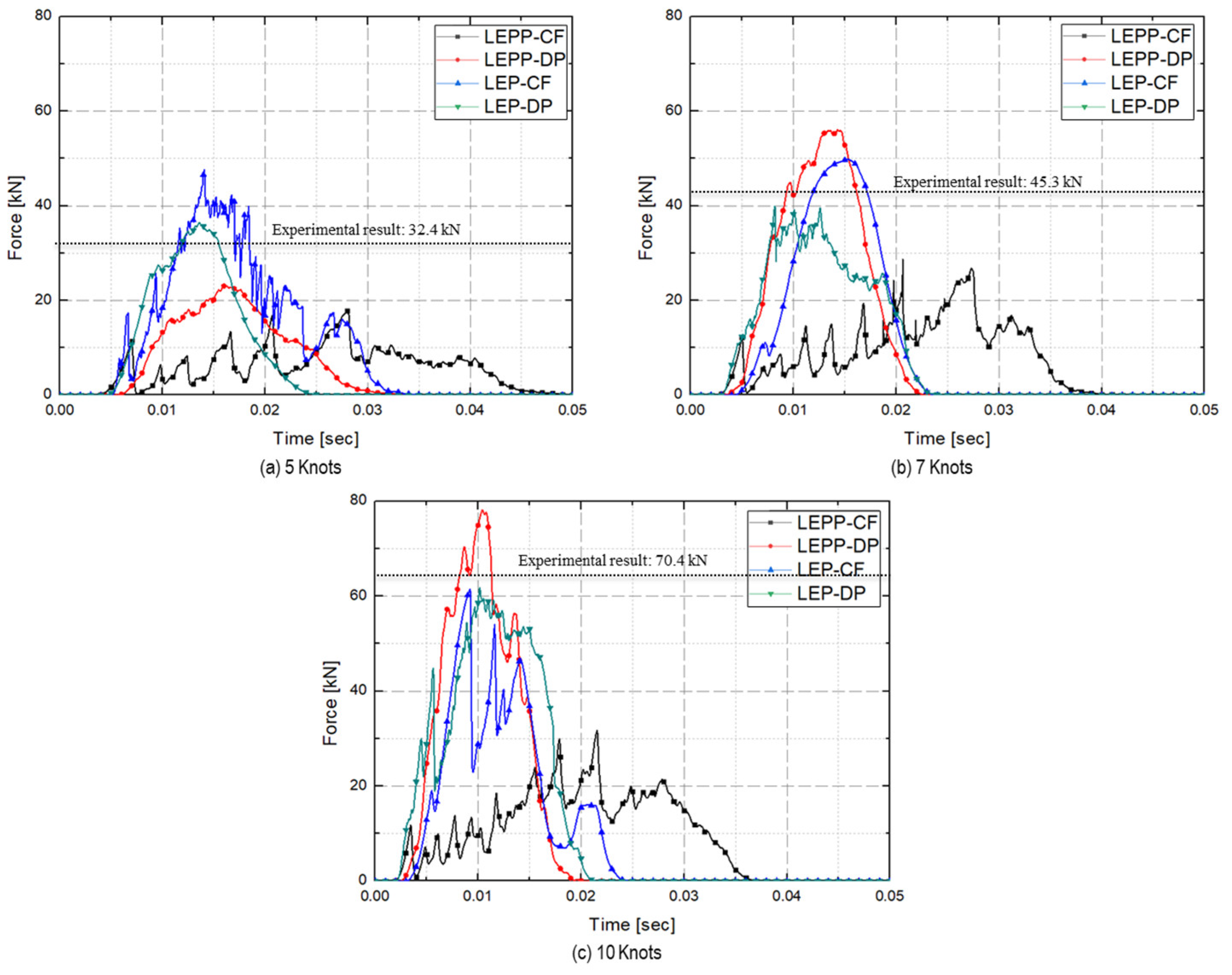

- Predicted strains on steel plate

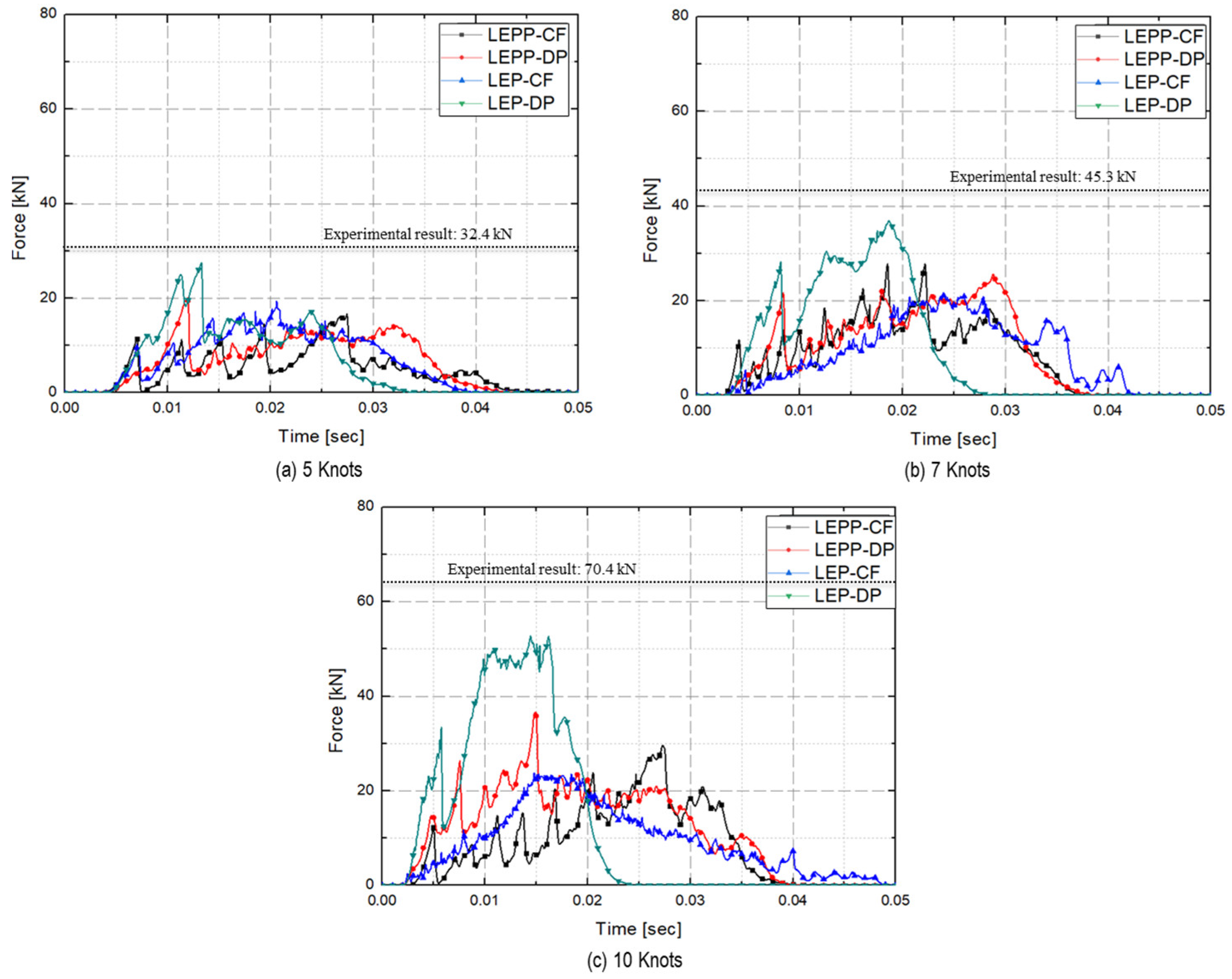

- Ice collision force prediction results

4.3. Collision Analysis Reflecting Yield Ratio According to Strain Rate

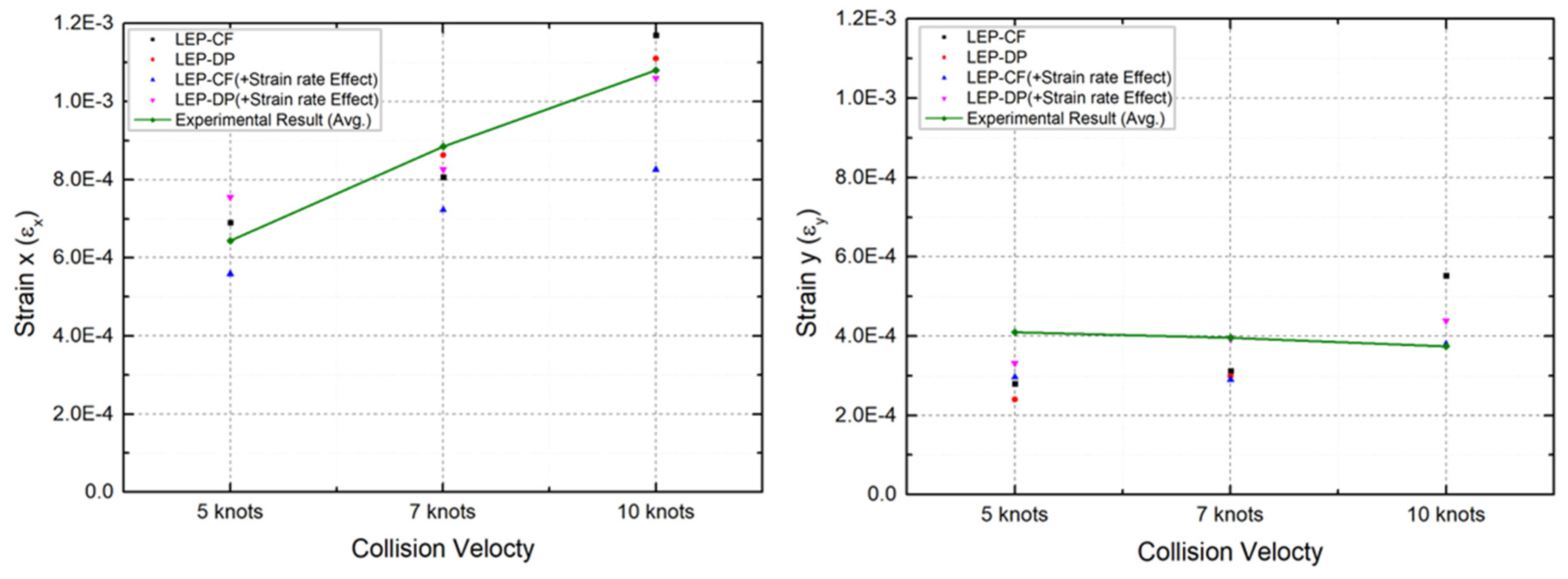

- Strain of steel plate prediction results

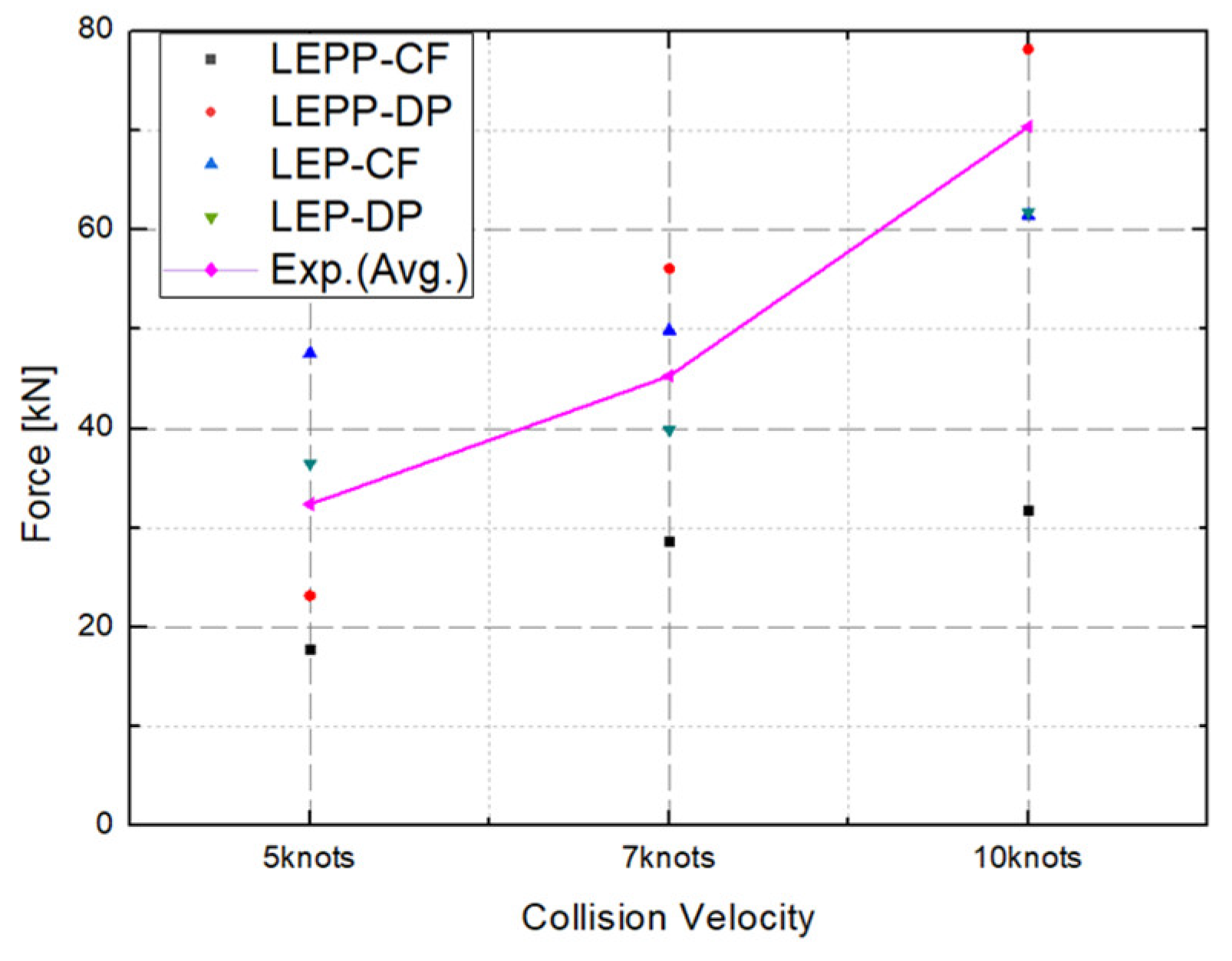

- Ice collision force prediction results

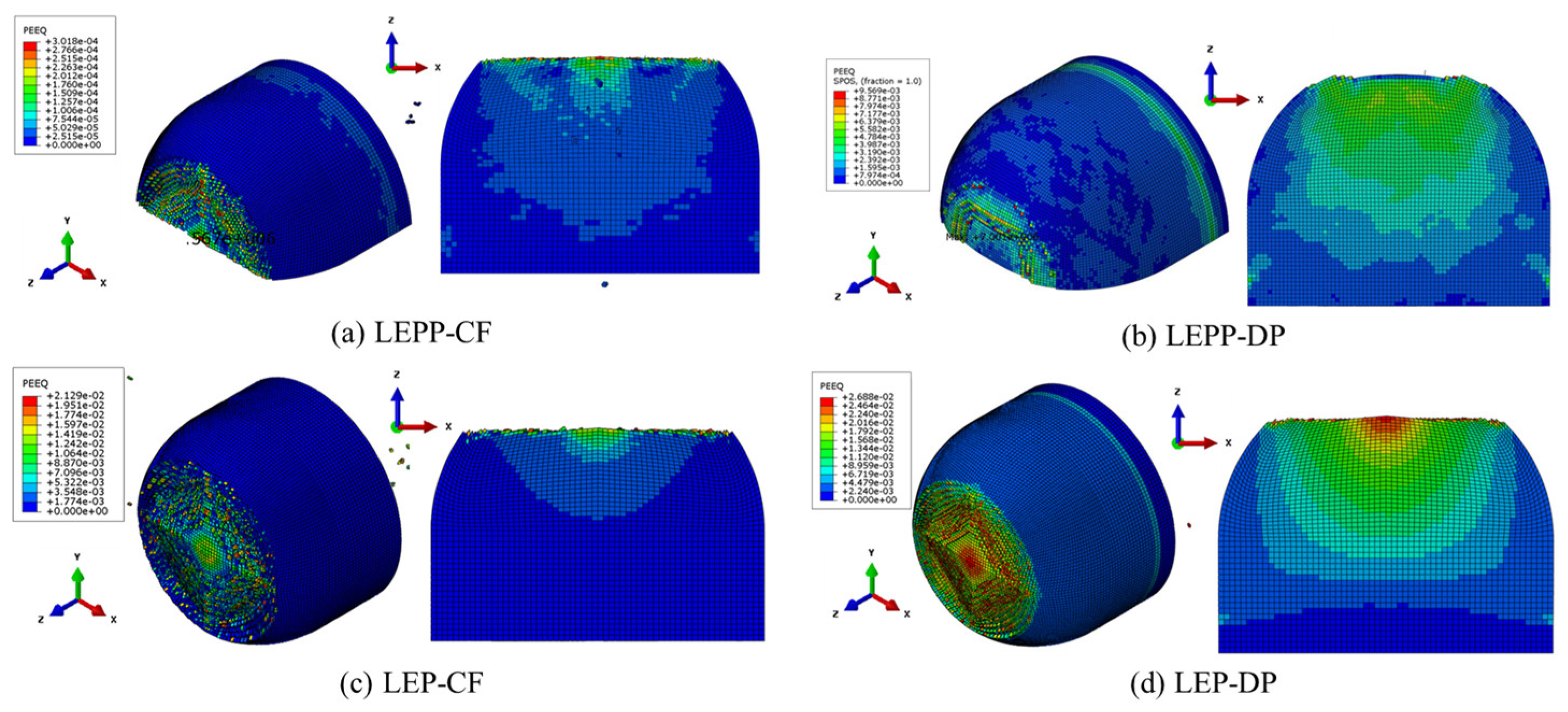

4.4. Evaluation of Suitability for each Combination of Ice Material Models

- The strain rates for each material model were compared to identify models that closely match the experimental results. Figure 28 presents a comparison of the accuracy of the maximum strain rates in the width and height directions of the plate specimen as a function of collision velocity. Table 13 and Table 14 provide a comparison of the calculated and experimental values for the horizontal strain and vertical strain for each analysis combination. Here, we observed that dynamic material properties combined with the DP model (LEP-DP) accurately simulated , with an 8.7% deviation, and , with a 12.4% deviation. In summary, our findings demonstrated that considering dynamic effects yields better strain rate predictions, and when considering both width and height directions, the combination of the dynamic material properties of ice with the DP model is deemed the most appropriate model.

| Collision velocity |

LEP-CF | LEP-DP | LEP-CF + Strain rate effect |

LEP-DP + Strain rate effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 kts | 6.90 × 10−4 (7.1%) | 6.43 × 10−4 (0.2%) | 5.59 × 10−4 (13.2%) | 7.55 × 10−4 (−17.3%) |

| 7 kts | 8.06 × 10−4 (8.9%) | 8.63 × 10−4 (2.3%) | 7.22 × 10−4 (18.4%) | 8.26 × 10−4 (6.7%) |

| 10 kts | 1.17 × 10−3 (8.3%) | 1.11 × 10−3 (2.8%) | 8.26 × 10−4 (6.7%) | 1.06 × 10−3 (2.0%) |

| Avg. Difference |

8.1% | 1.7% | 15.0% | 8.7% |

| Collision Velocity |

LEP-CF | LEP-DP | LEP-CF + Strain rate effect |

LEP-DP + Strain rate effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 kts | 2.80 × 10−4 (31.7%) | 2.40 × 10−4 (41.5%) | 2.96 × 10−4 (27.9%) | 3.32 × 10−4 (19.0%) |

| 7 kts | 3.12 × 10−4 (21.2%) | 2.99 × 10−4 (24.5%) | 2.90 × 10−4 (26.8%) | 3.92 × 10−4 (0.90%) |

| 10 kts | 5.53 × 10−3 (47.9%) | 3.76 × 10−3 (0.5%) | 3.80 × 10−4 (−1.5%) | 4.39 × 10−3 (−17.4%) |

| Avg. Difference |

33.6% | 22.1% | 17.7% | 12.4% |

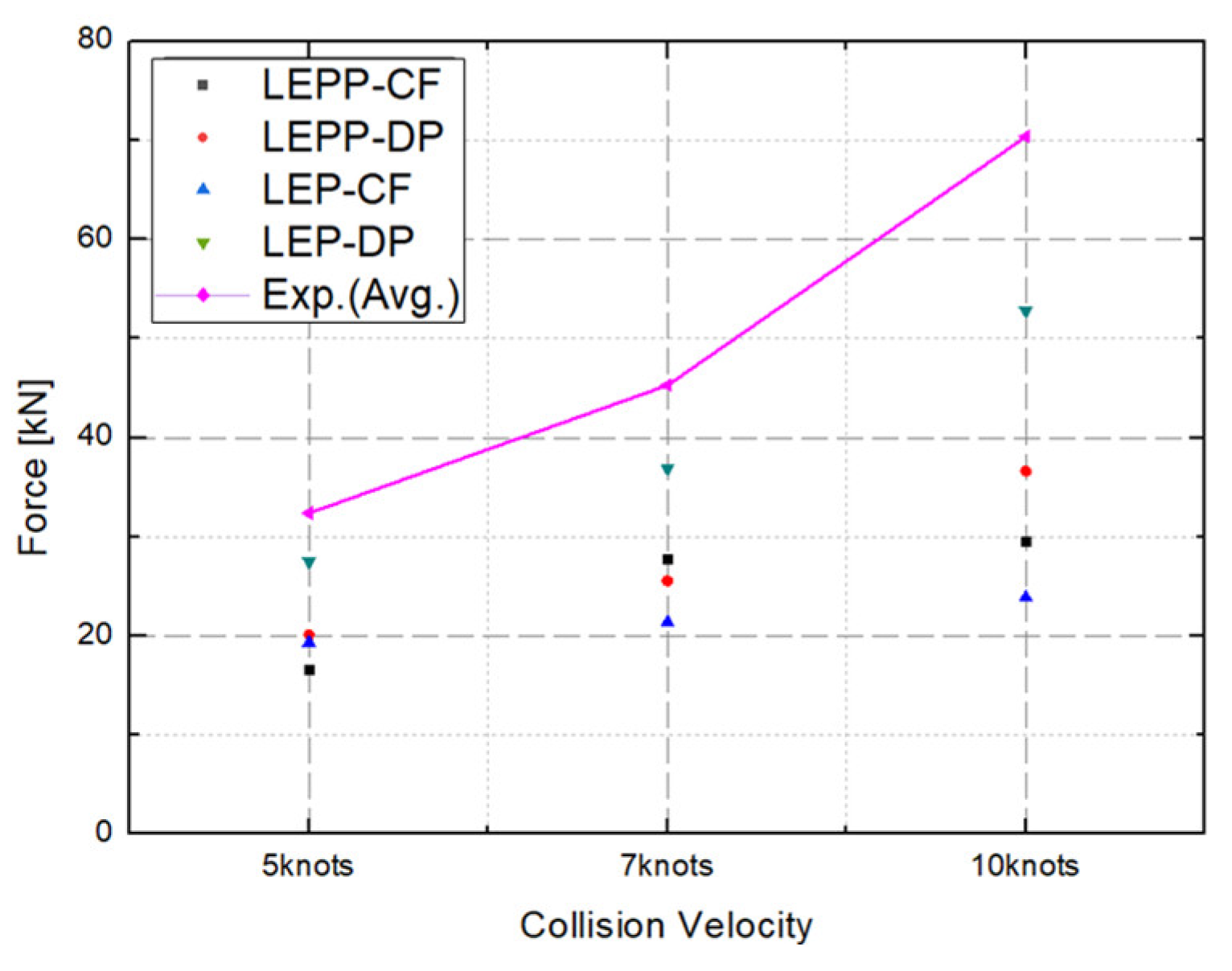

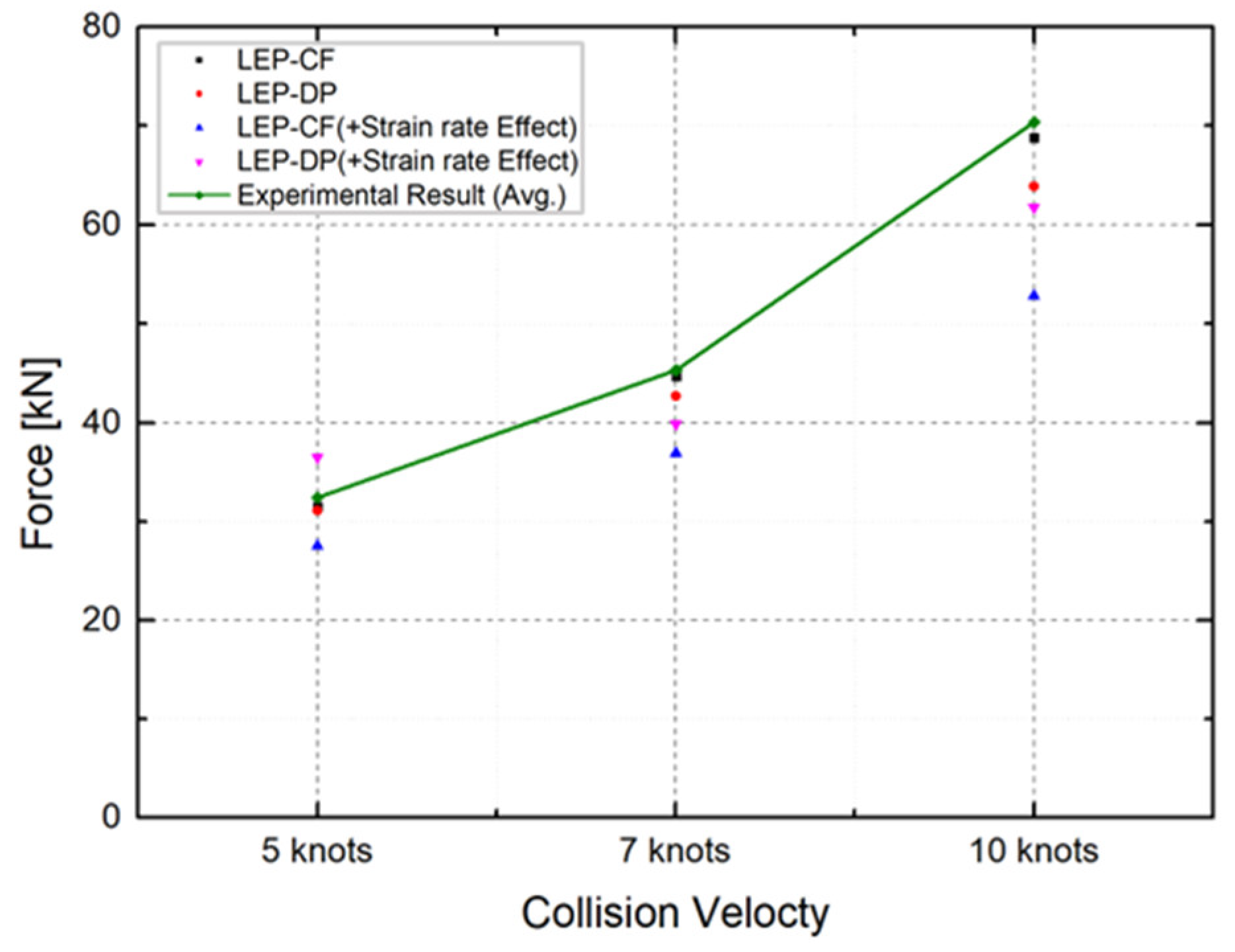

- Subsequently, we turned our attention to the maximum collision force exerted by the ice on the plate specimen. The maximum collision force applied by the ice to the plate specimen was compared for different ice material property models. Figure 29 compares the predicted collision force for each material model combination against the experimental data.

- Table 15 provides a comprehensive summary of the differences between experimental and analytical collision force for each material model combination. The inclusion of dynamic strain rate effects to the LEP material model with the DP yield condition (LEP-DP with strain rate effect) accurately predicts collision force with a 12.2% deviation, demonstrating high accuracy in both strain rates and collision force. This material model combination shows high accuracy in both strain rates and collision force.

| Collision Velocity |

LEP-CF | LEP-DP | LEP-CF + Strain rate effect |

LEP-DP + Strain rate effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 kts | 31.5 (2.9%) | 31.1 (4.2%) | 27.5 (25.0%) | 36.5 (-12.6%) |

| 7 kts | 44.7 (1.3%) | 42.7 (5.7%) | 36.9 (18.5%) | 39.9 (11.8%) |

| 10 kts | 68.8 (3.7%) | 63.9 (10.5%) | 52.8 (25.0%) | 61.8 (12.2%) |

| Avg. Difference |

2.6% | 6.8% | 19.5% | 12.2% |

| FEA Result | Material model | 5 kts | 7 kts | 10 kts | Mean Diff. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

) (Difference with experiment) |

LEP -DP |

(−13.2%) |

(−18.4%) |

(−6.7%) |

15.0% |

| LEP -DP + Strain rate effect |

(−17.3%) |

(−6.7%) |

(−2.0%) |

8.7% | |

|

) (Difference with experiment) |

LEP -DP |

(−27.9%) |

(−26.8%) |

(−1.5%) |

17.7% |

| LEP -DP + Strain rate effect |

(−19.0%) |

(−0.9%) |

(−17.4%) |

12.4% | |

| Max. force (Difference with experiment) |

LEP -DP | 27.5 (−25.0%) |

36.9 (−18.5%) |

52.8 (−25.0%) |

19.5% |

| LEP -DP + Strain rate effect |

36.5 (−12.6%) |

39.9 (−11.8%) |

61.8 (−12.2%) |

12.2% |

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tangborn, A.; Kan, S.; Tangborn, W. Calculation of the Size of the Iceberg Struck by the Oil tanker Overseas Ohio. In 14th IAHR Symposium on Ice, 1998; Vol. 1, pp 237-241.

- Gagnon, R. Results of numerical simulations of growler impact tests. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2007, 49(3), 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, R. A numerical model of ice crushing using a foam analogue. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2011, 65(3), 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Daley, C.; Colbourne, B. A numerical model for ice crushing on concave surfaces. Ocean Eng. 2015, 106, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajaste-Rudnitski, J.; Kujala, P. Ship propagation through ice field. J. Struct. Mech. 2014, 47(2), 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.; Kim, E.; Amdahl, J. Fluid-structure-interaction analysis of an ice block-structure collision. 2015.

- Zhu, L.; Qiu, X.; Chen, M.; Yu, T. Simplified ship-ice collision numerical simulations. In ISOPE International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference, 2016; ISOPE: pp ISOPE-I-16-521.

- Cai, W.; Zhu, L.; Yu, T.; Li, Y. Numerical simulations for plates under ice impact based on a concrete constitutive ice model. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2020, 143, 103594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Lee, H.; Choung, J.; Kim, H.; Daley, C. Cone ice crushing tests and simulations associated with various yield and fracture criteria. Ships and Offshore Structures 2017, 12 (sup1), S88–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutfraind, R.; Savage, S. B. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics for the simulation of broken-ice fields: Mohr–Coulomb-type rheology and frictional boundary conditions. J. Comput. Phys. 1997, 134(2), 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajaste-Rudnitski, J.; Kujala, P. Ship propagation through ice field. J. Struct. Mech. 2014, 47(2), 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Zheng, X.; Ma, Q. Updated smoothed particle hydrodynamics for simulating bending and compression failure progress of ice. Water 2017, 9(11), 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuhkuri, J.; Polojärvi, A. A review of discrete element simulation of ice–structure interaction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2018, 376(2129), 20170335. [Google Scholar]

- Tsarau, A.; Lubbad, R.; Løset, S. A numerical model for simulation of the hydrodynamic interactions between a marine floater and fragmented sea ice. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2014, 103, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Shang, J. Discrete element modeling of ice loads on ship hulls in broken ice fields. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2013, 32(11), 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.-S.; Hwang, S.-Y.; Lee, J. H. Experimental Evaluation and Validation of Pressure Distributions in Ice–Structure Collisions Using a Pendulum Apparatus. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11(9), 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrette, P. D.; Jordaan, I. J. Pressure–temperature effects on the compressive behavior of laboratory-grown and iceberg ice. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2003, 36(1-3), 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. J. High strain-rate compression tests on ice. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101(32), 6099–6101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, H.-S.; Jeong, S.-Y. Numerical simulation of ice impacts on ship hulls in broken ice fields. Ocean Eng. 2019, 182, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Kim, Y. Numerical simulation of level ice–structure interaction using damage-based erosion model. Ocean Eng. 2021, 220, 108485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, R.; Derradji-Aouat, A. First results of numerical simulations of bergy bit collisions with the CCGS terry fox icebreaker. In Proceedings of the 18th IAHR International Symposium on Ice, Sapporo, IAHR & AIRH, Japan; 2006; Citeseer. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Hu, Z.; Wang, J. Sensitivity analysis for iceberg geometry shape in ship-iceberg collision in view of different material models. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obisesan, A.; Sriramula, S. Efficient response modelling for performance characterisation and risk assessment of ship-iceberg collisions. Appl. Ocean Res. 2018, 74, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tippmann, J. D. Development of a strain rate sensitive ice material model for hail ice impact simulation; University of California: San Diego, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tippmann, J. D.; Kim, H.; Rhymer, J. D. Experimentally validated strain rate dependent material model for spherical ice impact simulation. Int. J. Imp. Eng. 2013, 57, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keune, J. Development of a hail ice impact model and the dynamic compressive strength properties of ice. Thesis, Purdue University, 2004.

- SIMULIA, Abaqus theory manual 6.13, Simulia 2013.

| Material behavior |

Model | Equation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yield criteria |

Crushable Foam |

|

Gagnon [3] Kim, et al. [4] |

| Drucker-Prager |

|

Kajaste-Rudnitski & Kujala [11] | |

| Damage model |

Ductile Damage |

|

Han, et al. [9] Kim, et al. [19] Jeon & Kim [20] |

| Strain rate dependency | - | Yield stress ratio as strain rate | Tippmann [24] |

| Material models |

Constitutive equation | Yield criterion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEPP | LEP | CF | DP | |

| LEPP-CF | O | O | ||

| LEPP-DP | O | O | ||

| LEP-CF | O | O | ||

| LEP-DP | O | O | ||

| LEPP | CF (Obisesan & Sriramula [23]) | DP (Jeon & Kim [20]) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Compression Yield Stress Ratio | Hydrostatic Yield Stress Ratio | Friction Angle |

Flow Stress Ratio |

Dilation Angle |

| Value | 1.49 | 1.79 | 36 deg | 1 | 12 deg |

| LEP | Crushable Foam (CF) | Drucker Prager (DP) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardening Value |

Stress | Strain | Stress | Strain |

| 0.5 MPa | 0 | 0.5 MPa | 0 | |

| 3.3 MPa | 0.019 | 3 MPa | 0.025 | |

| 3.3 MPa | 0.5 | 3 MPa | 0.5 | |

| FEA Result | LEPP-CF | LEPP-DP | LEP-CF | LEPP-DP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Force [kN] | 28.2 | 27.9 | 27.8 | 28.2 |

| Displacement[mm] | 5.02 | 5.1 | 4.98 | 4.92 |

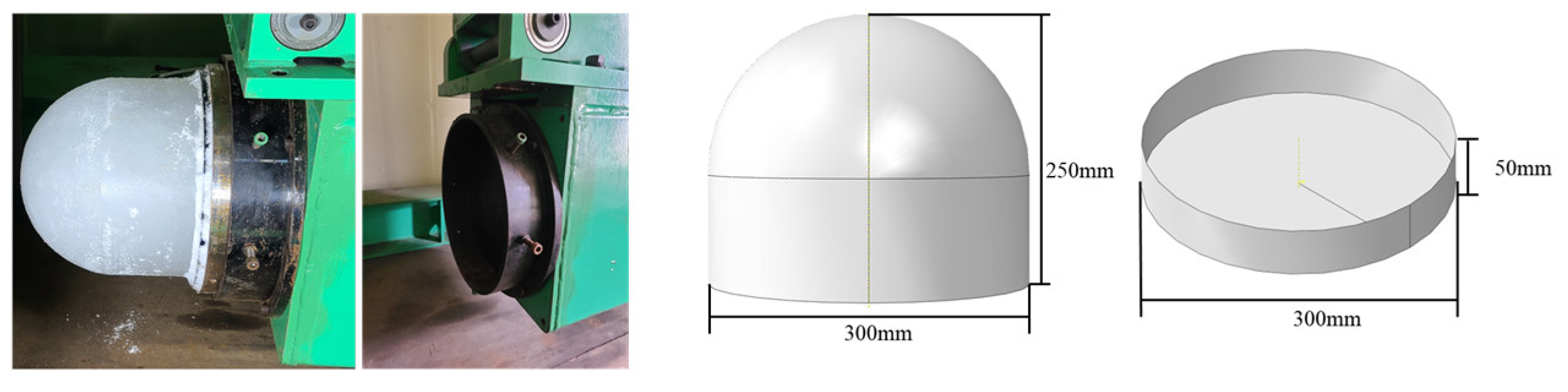

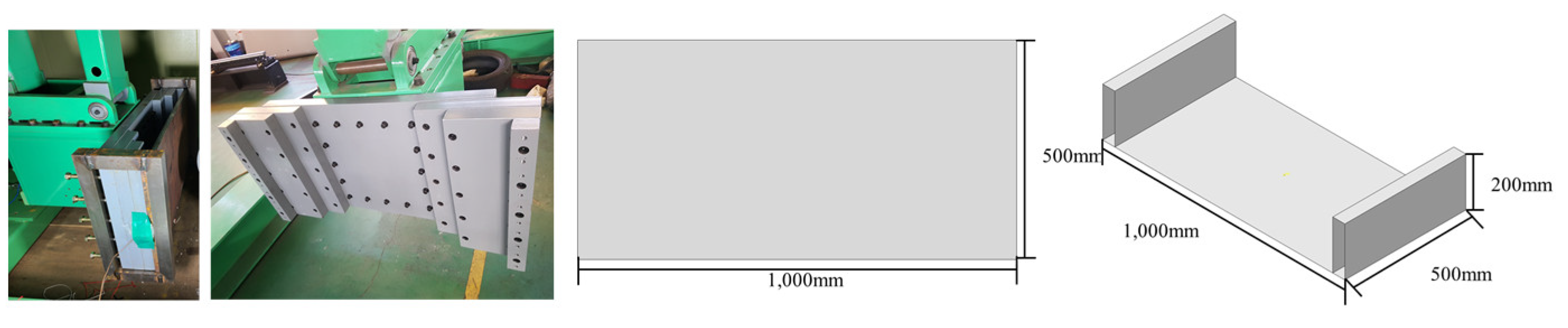

| Ice Specimen | Ice Holder | Steel Plate | Steel Jig | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry |

= 300 mm = 250 mm |

= 300 mm = 50 mm |

1,000 × 500 mm Thickness= 20 mm |

1,000×500 mm 200×50×500mm |

|

| Element | Deformable Body | Rigid Body | Deformable Body | Rigid Body | |

| Shell Element (S4R) |

Rigid Element (R3D4) | Solid Element (C3D8R) |

Rigid Element (R3D4) | ||

| Contact | Hard contact with steel plate (penalty contact, frictionless) |

Tie condition with ice |

Hard contact with steel plate (penalty contact, frictionless) |

Tie condition with steel plate |

|

| Collision Velocity |

Experiment (Avg.) |

LEPP -CF | LEPP -DP | LEP -CF | LEP -DP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 kts | 6.44 × 10−4 | 3.77 × 10−4(41.4%) | 3.59 × 10−4(44.3%) | 3.44 × 10−4(46.7%) | 5.59 × 10−4(13.2%) |

| 7 kts | 8.85 × 10−4 | 4.72 × 10−4(46.6%) | 6.19 × 10−4(30.1%) | 4.65 × 10−4(47.4%) | 7.22 × 10−4(18.4%) |

| 10 kts | 1.08 × 10−3 | 5.26 × 10−4(51.3%) | 5.87 × 10−4(45.6%) | 5.37 × 10−4(50.3%) | 9.35 × 10−3(13.4%) |

| Difference | - | 46.4% | 40.0% | 51.3% | 15.0% |

| Collision Velocity |

Experiment (Avg.) |

LEPP -CF | LEPP -DP | LEP -CF | LEP -DP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 kts | 4.10 × 10−4 | 1.76 × 10−4(57.1%) | 2.01 × 10−4(50.9%) | 1.78 × 10−4(56.5%) | 2.96 × 10−4(27.9%) |

| 7 kts | 3.96 × 10−4 | 2.58 × 10−4(34.9%) | 2.51 × 10−4(36.6%) | 1.81 × 10−4(23.1%) | 2.90 × 10−4(26.8%) |

| 10 kts | 3.74 × 10−4 | 3.09 × 10−4(17.3%) | 2.34 × 10−4(37.4%) | 3.87 × 10−4(-3.4%) | 3.80 × 10−4(-1.5%) |

| Difference | - | 46.4% | 40.0% | 51.3% | 15.0% |

| Collision Velocity |

Experiment (Avg.) |

LEPP -CF | LEPP -DP | LEP -CF | LEP -DP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 kts | 32.4 | 16.7(48.6%) | 20.1(37.9%) | 19.3(40.3%) | 27.5(15.1%) |

| 7 kts | 45.3 | 31.8(38.6%) | 25.6(43.6%) | 21.4(52.8%) | 36.9(18.5%) |

| 10 kts | 70.4 | 24.99(58.0) | 36.6(48.0%) | 23.9(66.1%) | 52.8(25.0%) |

| Difference | - | 48.4% | 43.1% | 53.1% | 22.1% |

| Collision Velocity |

Experiment (Avg.) |

LEPP -CF | LEPP -DP | LEP -CF | LEP -DP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 kts | 6.44 × 10−4 | 3.30 × 10−4(48.8%) | 4.82 × 10−4(25.2%) | 7.98 × 10−4(-23.9%) | 7.55 × 10−4(-17.3%) |

| 7 kts | 8.85 × 10−4 | 4.72 × 10−4(46.6%) | 1.07 × 10−3(-21.3%) | 1.08 × 10−3(-21.7%) | 8.26 × 10−4(6.7%) |

| 10 kts | 1.08 × 10−3 | 5.26 × 10−4(51.3%) | 1.73 × 10−3(-29.6%) | 1.24 × 10−3(-14.5%) | 1.06 × 10−3(2.0%) |

| Difference | - | 48.9% | 30.2% | 20.0% | 8.7% |

| Collision Velocity |

Experiment (Avg.) |

LEPP -CF | LEPP -DP | LEP -CF | LEP -DP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 kts | 4.10e-04 | 1.83 × 10−4(55.4%) | 1.95 × 10−4(52.4%) | 4.31 × 10−4(-5.03%) | 3.32 × 10−4(19.0%) |

| 7 kts | 3.96e-04 | 2.59 × 10−4(34.6%) | 3.78 × 10−4(4.6%) | 5.30 × 10−4(-33.9%) | 3.92 × 10−4(0.9%) |

| 10 kts | 3.74e-04 | 3.09 × 10−4(17.4%) | 4.67 × 10−4(-24.8%) | 3.36 × 10−4(10.0%) | 4.39 × 10−4(-17.4%) |

| Difference | - | 35.8% | 27.3% | 16.3% | 12.4% |

| Collision Velocity |

Experiment (Avg.) |

LEPP -CF | LEPP -DP | LEP -CF | LEP -DP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 kts | 32.4 | 17.8 (45.1%) | 23.2 (28.5%) | 47.6 (-46.8%) | 36.5 (-12.7%) |

| 7 kts | 45.3 | 28.7 (36.7%) | 56.1 (-23.8%) | 49.9 (-10.1%) | 39.9 (11.8%) |

| 10 kts | 70.4 | 31.8 (54.9%) | 78.2 (-11.0%) | 61.5 (12.6%) | 61.8 (12.2%) |

| Difference | - | 45.6% | 21.1% | 34.8% | 12.2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).