1. Introduction

Our eyes, constantly in motion, play a pivotal role in visual information processing. Even when our gaze is steady, tiny eye movements, known as fixational or micro saccades, are crucial. These movements not only prevent the loss of conscious vision (Martinez-Conde et al., 2006), but also aid in attention shifts (Hafed and Clark, 2002; Engbert and Kliegl, 2003), enhance visual sensitivity (Bonneh et al., 2015; Scholes et al., 2015), and improve visual acuity (Ko et al., 2010; see also Rucci and Desbordes, 2003).

Vergence, another form of eye movement (Collewijn & Erkelens, 1990; Mon-Williams, Tresilian, & Roberts, 2000; Richard & Miller, 1969; Ritter, 1977; Viguier, Clement, & Trotter, 2001), involves the eyes moving in opposite directions to achieve and maintain monocular vision. Our research has discovered a new role for vergence eye movements in cognitive processing. We observed that the eyes briefly converge following the presentation of a visual stimulus (Solé Puig et al., 2013). These vergence responses are more pronounced when the stimulus is attended, perceived, or retained in memory (e.g. see Solé Puig et al., 2013, 2016; 2017). This indicates a potential role of vergence in attention. Additional evidence comes from observations that individuals with attentional difficulties exhibit poor vergence responses during an attentional task (Varela et al., 2018). We refer to this phenomenon as cognitive vergence.

Cognitive vergence responses appear early and increase as the processing of a stimulus reaches a level where their strength correlates with behavioral performance. This suggests that vergence responses could predict the extent to which a stimulus is processed. Therefore, measuring cognitive vergence could potentially serve as an objective marker for detecting cognitive problems. Indeed, AI classifier models using cognitive vergence responses as input have successfully identified patients with ADHD (Varela et al., 2018) and Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) (Jiménez et al., 2021). In MCI patients, attended stimuli are accompanied by a weak enhancement whereas Alzheimer patients show no difference in vergence responses to attended and unattended stimuli. Such models can even predict the risk of MCI patients developing Alzheimer’s disease (Hashemi et al., 2023).

Eye gaze tracking is typically performed using specially designed devices that employ infrared light to detect pupil size and center and estimate gaze position. However, new methods are emerging that utilize advanced imaging techniques in the visible light spectrum to estimate gaze position using the iris of the eye (Valenti et al., 2009). This advancement paves the way for developing consumer-grade eye tracking technology that could potentially be used to detect mental health conditions by measuring cognitive vergence. In this study, we explored the feasibility of such a technique by testing MCI patients. Participants performed a brief computerized visual oddball paradigm while cognitive vergence eye movements were measured from images recorded by a webcam. Eye positions were also recorded simultaneously with a remote infrared-based pupil eye tracker.

Our results indicate that a differential vergence response to the oddball task stimuli (targets and distractors) can be measured with both the webcam-based iris tracker and infrared pupil tracker. Although the absolute magnitude of the vergence angle varied between trackers, the modulation pattern and index of the vergence responses were similar for both trackers. The findings imply that employing a consumer-grade webcam could be a viable method for capturing cognitive vergence. This holds promise for future research aimed at creating an affordable screening instrument for mental health care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

We tested 28 subjects (9 men and 19 women) recruited from a private day care center for the elderly in Barcelona. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was administered to all participants to evaluate their cognitive abilities.

2.2. Ethical Statement

Participants and their relatives received detailed instructions for the experiments. Prior to enrollment, patients or family members signed a written informed consent for their participation in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the ethics committees of the University of Barcelona.

2.3. Apparatus

We used the BGaze software (Braingaze SL, Mataró, Spain) on a laptop (MSI CX62 6QD) to present the visual stimuli and record eye position data. The faces of the participants while performing the task were recorded with the integrated webcam (HD type, 30fps, 720p). The resolution of the screen (HD 15.6") was 1366 x 768 pixels and the remote eye tracker used was an X2-30 (30Hz, Tobii Technology AB, Sweden).

2.4. Experimental procedure

The task was performed in the living room of each patient's home in order to have conditions in an operational setting. No chin rest was used and patients could wear corrective lenses. The subjects were seated approximately 50 cm from the screen on which the stimuli were presented.

2.5. Paradigm

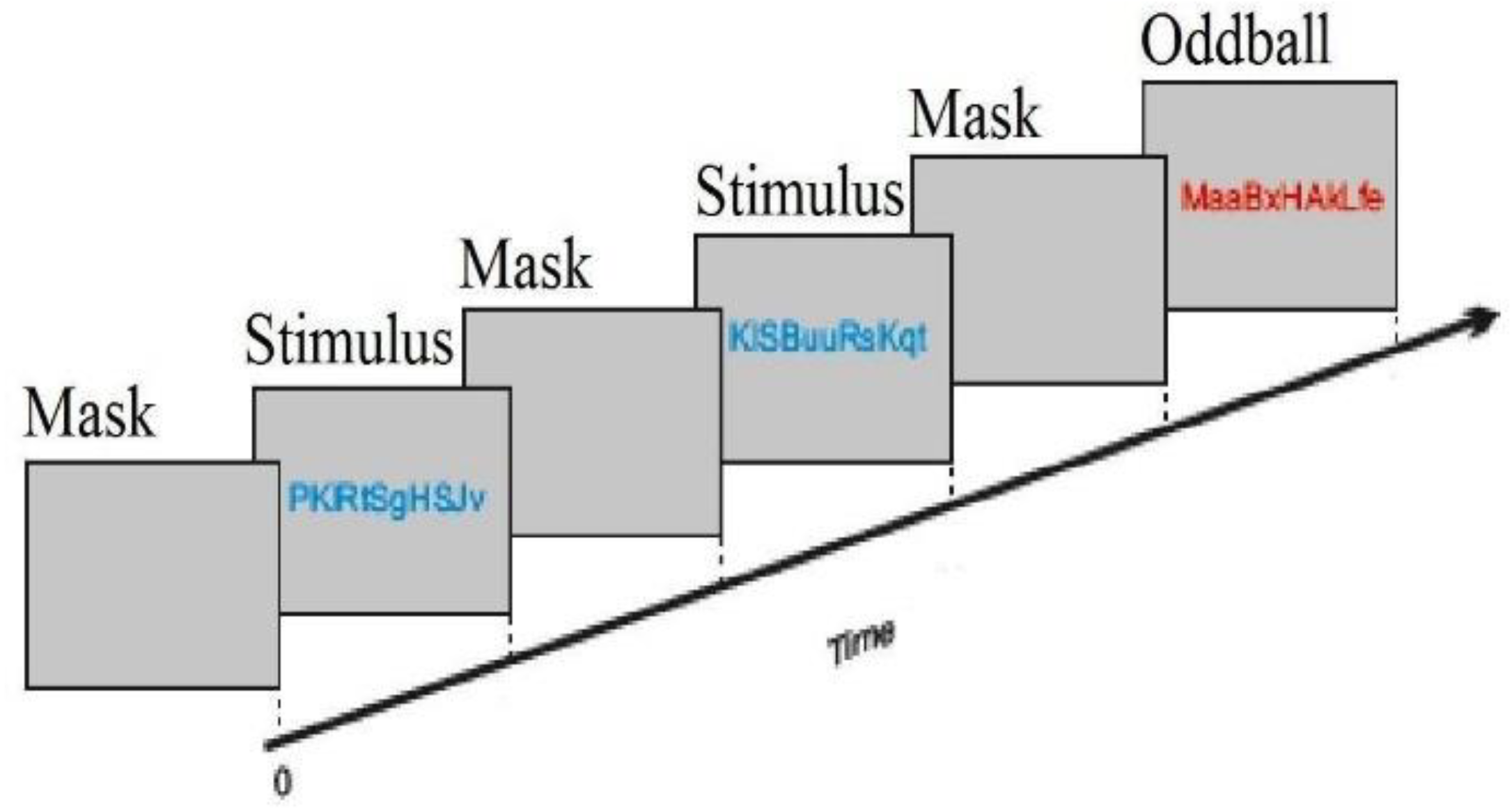

The experiment employed a visual oddball paradigm, comprising a sequence of 100 trials. Each trial began with a gray screen (mask) displayed for 2000 ms, followed by a centrally presented visual stimulus for an equal duration (

Figure 1). This stimulus consisted of an 11-character string of letters, randomly selected and varying in case. To avoid bias, these strings did not form acronyms or meaningful words. The strings were identical except for their color. In 80% of the trials, all characters were blue, while in the remaining 20%, they were red. Participants were instructed to focus on the screen and press a key only when the characters were red. Thus, red character strings served as targets, and blue ones as distractors. The stimuli were presented randomly. The task, lasting approximately 6 minutes, involved recording pupil positions using a remote eye tracker and capturing the participant’s face with a webcam.

2.6. Webcam-based eye tracking

To obtain cognitive vergence measurements from the webcam images, we used the model described in (Wang et al., 2019), which captures the 3D head poses, facial expression deformations, and 3D eye gaze states using a single RGB camera. The whole system consists of several components. First, important facial features are automatically detected and tracked, and the optical flow of each pixel in the face region is computed. Then, a data-driven 3D facial reconstruction technique is performed to reconstruct the 3D head pose and large-scale expression deformations using multi-linear expression deformation models. A pixel classifier then automatically annotates the iris and pupil pixels in the eye region, which is bounded by detected facial landmarks in the eye region. Additionally, the outer contour of the iris (i.e., the limbus) is extracted to further improve the robustness and accuracy of the gaze tracker. A DCNN-based segmentation method is used to perform a frame-by-frame pixel extraction of the iris including the pupil region. The convolutional neural network is used to predict the probability that each pixel belongs to the entire iris, including the pupil region. To track the gaze states in the video sequences, the geometric shape and 3D position of the eyeballs and the radius of the iris region together with the limbus are estimated.

2.7. Cognitive vergence calculation

Data points from the infrared eye tracker that did not correspond to valid pupil detections (i.e., whenever the validity score given by the eye tracker software had a non-zero value) were marked out. Trials with too many invalid data points (15 points or more) were discarded. The exclusion rate was 33%. Finally, interpolation was used to create sequences of evenly spaced points. In the case of the webcam eye tracker, all trials were included in the data analysis.

To calculate vergence changes, we transformed the coordinates of the left and right eye provided by the eye tracker into angular values. Rather than the vergence angle itself, say γ, we focus on the relative vergence modulation , where γ0 represents the γ value at stimulus onset, and the indicated maximum was taken for all absolute values of the difference γ(t)-γ0 in the examined time window of each trial. The subtraction of the initial values from each response served the purpose of obtaining relative changes. Subsequently, all sequences coming from trials in the same condition (target, distractor) were averaged in obtain ‘mean ’ curves.

2.8. Data and Statistical Analysis

The peak vergence response was evaluated as the mean in the 400-433ms window. Delayed responses were calculated as the average response strength over the window 600-1250 ms after stimulus onset. Modulation indices were calculated as mi= (T-D)/(T+D), where T(D) is the mean of the window-averaged vergence responses for all target (distractor) trials. For both tracker methods, the window limits were 300-600 ms. For statistical analysis, we performed a series of comparisons based on the two-tailed t-test of all accepted trials or subjects.

3. Results

MOCA scores ranged from 11 to 25 (mean±std: 16.8±3.9) out of a possible 30, indicating that subjects had cognitive impairment. Three subjects were excluded from further analysis of infrared eye tracker data because they did not provide valid pupil recordings. In total, there were 1512 distractor trials and 350 target trials. Removing the same 3 participants from the webcam data did not significantly change the results. Therefore, we decided to include all 28 subjects in the analysis of the webcam data. The total number of distractor trials was 2240 and target trials were 560, but only 2218 and 551, respectively, were correctly recorded.

3.1. Cognitive Vergence Responses

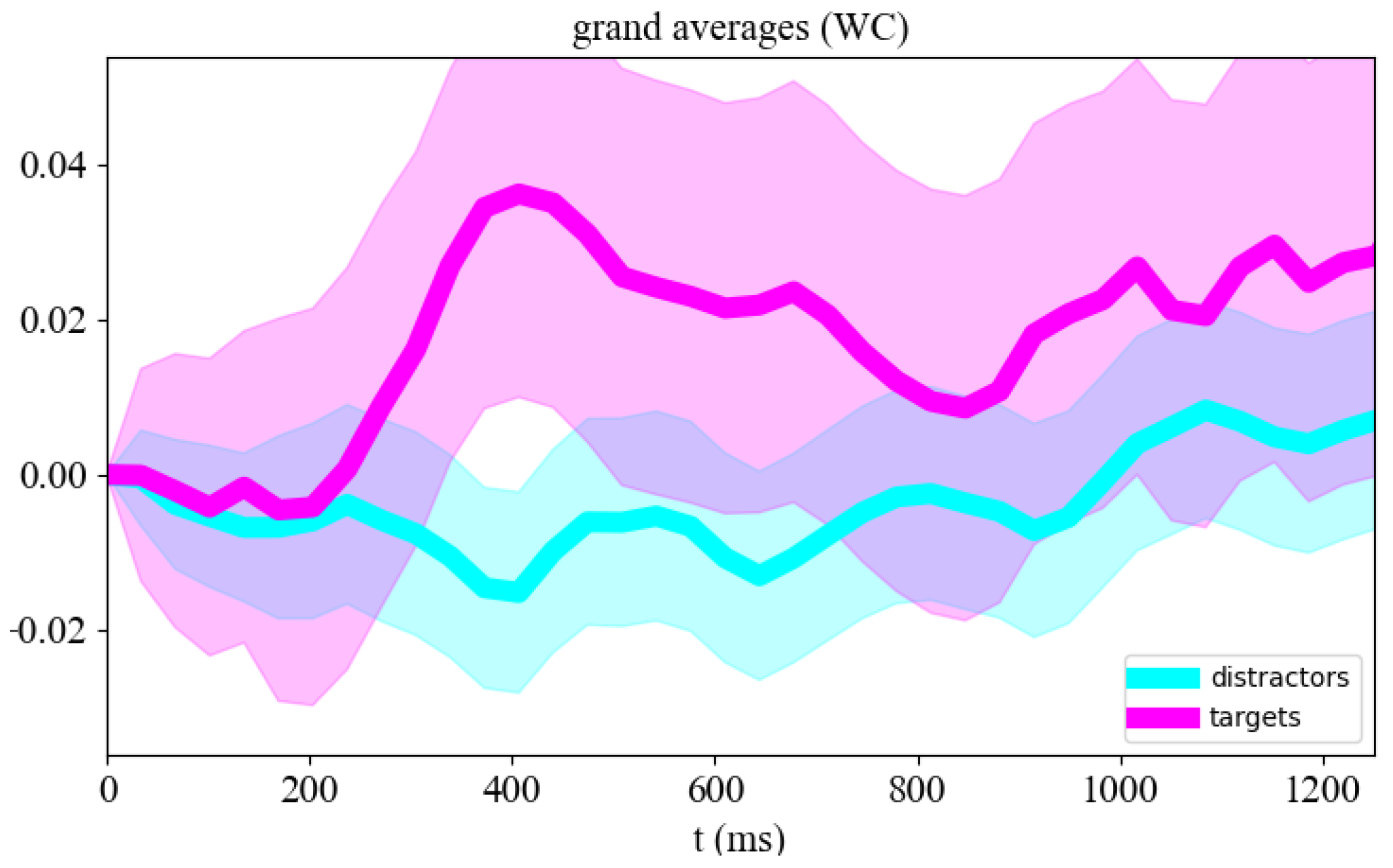

Iris positions were extracted from the webcam images to calculate vergence responses separately for the target and distractor conditions. The average target response of all participants across trials shows a clear increase in vergence angle starting about 300 ms after stimulus onset and peaking at about 450 ms, followed by a delay response (

Figure 2). The average peak response to targets (mean±std: 0.036 ± 0.107) was stronger than the initial --i.e., 0-200ms-- averaged vergence responses (mean±std: -0.002 ± 0.060, t=1.60, p=0.12). The average target delay response (mean±std: 0.021 ± 0.083) was similar to the initial response strength (t=1.19, p=0.24). Vergence eye movements during distractor trials showed neither a peak response (mean±std: -0.013 ± 0.062) nor a clear delay response (mean±std:0.001±0.056), but a slightly significant response increase from 600 ms of 3.3•10-5 deg/ms was visible.

3.3. Infrared eye tracker

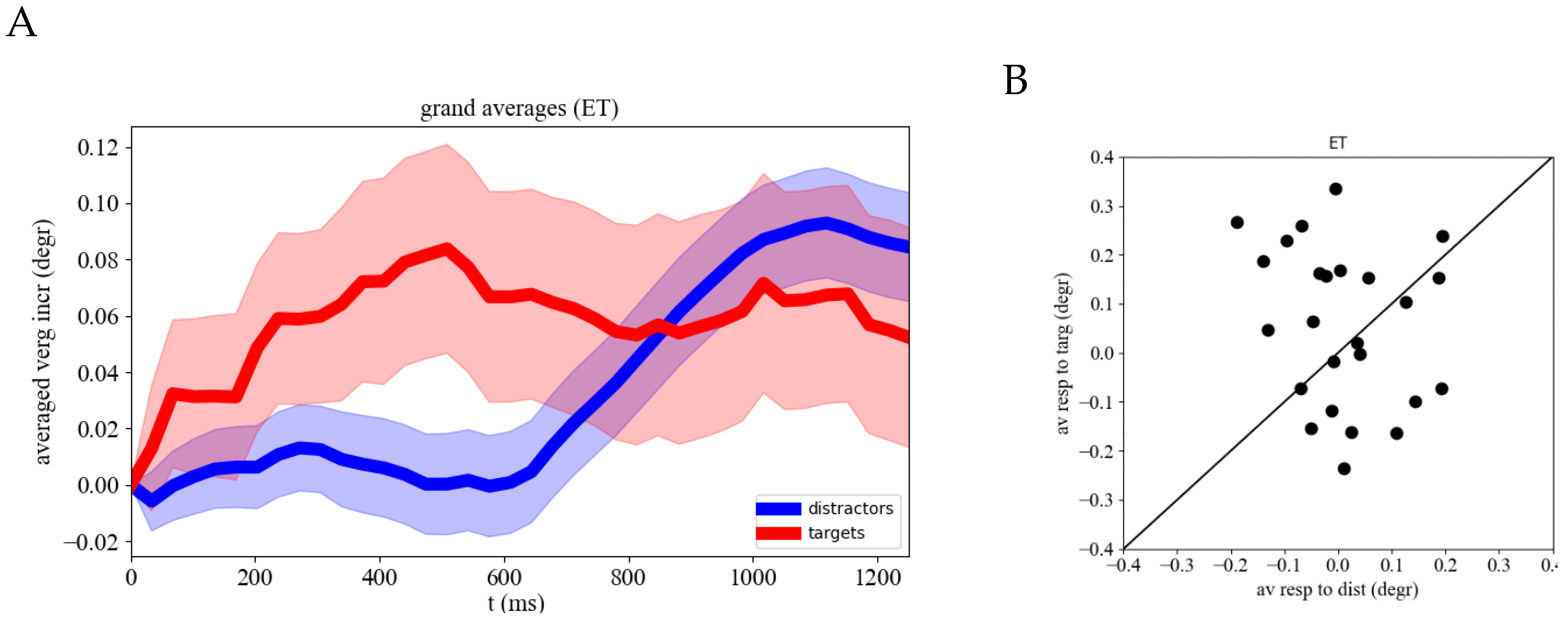

Simultaneously with the webcam recording, we recorded vergence responses with a remote infrared-based eye tracker, allowing us to compare both methods. The average vergence response to targets recorded with the infrared eye tracker showed a peak response around 500 ms followed by a delay response (

Figure 4). The results show that 52% of the subjects had a stronger peak response to targets than to distractors. The average peak response to targets (mean±std: 0.076±0.534) was significantly (t=-2.24, p=0.03) stronger than the average response to distractors (mean±std: 0.005±0.530). The delay response in the distractor condition showed a strong increase starting at about 600 ms and reaching a maximum at 1100 ms.

3.4. Comparison webcam-based to infrared eye tracker

To compare the differential vergence response recorded by the webcam-based eye tracker with that of the infrared-based eye tracker, we plotted the modulation indices per subject. The window for calculating the modulation index was 300-600 ms. The results show that 75.0% and 66.6% of the subjects showed a positive modulation index, i.e., the responses to targets were stronger than those to distractors when recorded with the infrared-based eye tracker and the webcam-based eye tracker, respectively (

Figure 5). However, in 28.4 % of the participants (N=6) it was a positive modulation in the webcam eye tracker while it was a negative modulation in the infrared eye tracker. Seven participants showed a positive modulation index in the infrared tracking but a negative one with webcam tracking, and 9 participants showed positive modulation in both trackers. The average modulation index (mi) across subjects from the infrared-based eye tracker miET (mean±std: 1.06±2.69) was not significantly (t=0.40, p=0.70) different from the average modulation index from the webcam-based eye tracker miWC (mean±std: 0.66±4.51).

4. Discussion

In this study, we compared cognitive vergence responses recorded with a webcam-based eye tracker to those captured with a remote infrared-based eye tracker during an oddball task. Both trackers exhibited a similar temporal pattern of vergence responses. However, the absolute response amplitudes were smaller when recorded with the webcam-based tracker, possibly due to differences in recording and computation methods.

Both the webcam-based eye tracker and the infrared-based eye tracker produced stronger responses to targets than to distractors, in agreement with our previous study showing a differential vergence response in an elderly population (Jiménez et al., 2021). This differential response is typically present in cognitively healthy subjects but is reduced or absent in those with cognitive impairment. Given that all participants in our current study had a history of cognitive impairment, as indicated by their MoCA scores, this could explain why some did not exhibit a differential vergence response. We conducted this study in an uncontrolled environment without the use of a chin rest, which may have introduced additional noise into the eye tracking data. The sensitivity of the trackers to noise is unlikely to be identical due to their different signal detection methods. Despite differences in absolute magnitude, both tracking methods yielded similar temporal patterns of cognitive vergence responses and captured a differential response.

4.1. Cognitive vergence: noise or signal?

The neural mechanisms that govern vergence and pupil size share some overlap, leading to a situation where a vergence eye movement can elicit a pupil response (Feil et al., 2017). This interplay results in a complex behavioral relationship (see Solé Puig et al., 2021). Infrared-based eye trackers estimate gaze position using pupil size, center, and corneal reflectance. Some suggest that these metrics may introduce errors in estimating eye movement amplitude (Hooge, Holmqvist, & Nystrom, 2016; Hooge et al., 2019; Drewes et al., 2014; Holmqvist & Blignaut, 2020). They argue that cognitive vergence may represent pupil dynamics rather than an actual vergence movement (Hooge et al., 2019). However, other studies indicate that infrared-based tracking is comparable to the search coil method for measuring small fixational eye movements (McCamy et al., 2015). They also suggest that pupil-related errors may become negligible at viewing distances beyond 50 cm (Jaschinski, 2016), which aligns with the distance we used in our study.

Despite these findings, one could still argue that cognitive vergence represents pupil dynamics or even a measurement artifact. To address this, our study employed a webcam-based eye tracker that estimates gaze by detecting the iris area and limbus. These measurements are independent of pupil detection and remain unaffected by changes in pupil size.

Our study obtained a clear differential vergence response with the webcam-based eye tracker. This lends further support to the notion that cognitive vergence results from the rotation of the eyeball, rather than being an artifact or error in measurements of pupil size or corneal reflectance.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings suggest that a consumer-grade webcam holds promise as a potential tool for recording cognitive vergence. To establish it as an affordable screening aid, further research is required to validate its clinical effectiveness and demonstrate its applicability in the realm of mental health care.

6. Patents

The IP of the method to detect cognitive disorders is protected by a patent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S.; methodology, O.L.; software, O.L..; validation, A.R., O.L. and M.S.P.; formal analysis, A.R.; investigation, M.S.P.; resources, H.S.; data curation, A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.; writing—review and editing, A.R.; visualization, A.R.; O.L.; supervision, H.S.; project administration, H.S.; funding acquisition, H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by AGAUR, Spain, grant number 2018 DI 75.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Barcelona (protocol code IRB00003099, 14 Nov 2019).” for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data of this study can be requested by email to HS.

Conflicts of Interest

HS is co-founder of Braingaze S.L., Spain.

References

- Bonneh YS, Adini Y, Polat U. Contrast sensitivity revealed by microsaccades. J Vision 2005; 15:11.

- Collewijn, H., Erkelens, C. J., & Steinman, R. M. (1997). Trajectories of the human binocular fixation point during conjugate and non-conjugate gaze-shifts. Vision Research, 37, 1049–1069.

- Drewes J, Zhu W, Hu Y, Hu X (2014). Smaller is better: Drift in gaze measurements due to pupil dynamics. PLoS One 9(10): e111197. [CrossRef]

- Engbert R, Kliegl R (2003). Microsaccades uncover the orientation of covert attention. Vision Research 43:1035-1045.

- Feil M, Moser B, Abegg M (2017). The interaction of pupil response with the vergence system. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 255: 2247–2253. [CrossRef]

- Francis EL & Owens DA (1983). The accuracy of binocular vergence for peripheral stimuli. Vision Research, 23(1), 13–19. [CrossRef]

- Hafed ZM, Clark JJ (2002). Microsaccades as an overt measure of covert attention shifts. Vision Research 42:2533-2545.

- Hashemi A, Leonovych O, Jiménez EC, Sierra-Marcos A, Romeo A, Bustos Valenzuela P, Solé Puig M, López Moliner J, Tubau E, Supèr H (2023). Classification of MCI patients using vergence eye movements and pupil responses obtained during a visual oddball test (Aging and Health Research 3 (2023) 100121. [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist K, & Blignaut, P (2020). Small eye movements cannot be reliably measured by video-based P-CR eye-trackers. Behavior research methods. [CrossRef]

- Hooge ITC, Holmqvist K, Nyström M (2016) Are video-based pupil-CR eye trackers suitable for studying detailed dynamics of eye movements? Vision Research, 128, pp. 6-18.

- Hooge ITC, Hessels RS, Nyström M (2019). Do pupil-based binocular video eye trackers reliably measure vergence? Vision Research. 156:1-9. [CrossRef]

- Jaschinski, W (2016). Pupil size affects measures of eye position in video eye tracking: implications for recording vergence accuracy. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 9 (4).

- Jiménez EC, Sierra-Marcos A, Romeo A, Hashemi A, Leonovych O, Bustos-Valenzuela P, Solé Puig M, Supèr H (2021). Altered Vergence Eye Movements and Pupil Response of Patients with Alzheimer's Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment During an Oddball Task. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021;82(1):421-433. [CrossRef]

- Ko H, Poletti M, Rucci M. (2010). Microsaccades precisely relocate gaze in a high visual acuity task. Nature Neuroscience 13: 1549-1554.

- Martinez-Conde S. Macknik SL, Troncoso XG, Dyar T (2006). Microsaccades counteract visual fading during fixation. Neuron 49: 297-305.

- McCamy MB, Otero Millan J, Leigh RJ, King SA, Schneider RM, Macknik SL, Martinez Conde S (2015) Simultaneous recordings of human microsaccades and drifts with a contemporary video eye tracker and the search coil technique PLoS One, 10 (6) e0128428.

- Mon-Williams, M., Tresilian, J. R., & Roberts, A. (2000). Vergence provides veridical depth perception from horizontal retinal image disparities. Experimental Brain Research, 133, 407–413.

- Richard, W., & Miller, J. F. (1969). Convergence as a cue to depth. Perception & Psychophysics, 5, 317–320.

- Ritter, M. (1977). Effect of disparity and viewing distance on perceived depth. Perception & Psychophysics, 22, 400–407.

- Rucci M, Desbordes G. (2003). Contributions of fixational eye movements to the discrimination of briefly presented stimuli. J. Vision 19: 852-864.

- Scholes C, McGraw PV, Nyström M, Roach NW (2015). Fixational eye movements predict visual sensitivity. Proc Biol Sci. 282(1817):20151568. [CrossRef]

- Solé Puig M, Pérez Zapata L, Aznar-Casanova JA, Supèr H (2013). A role of eye vergence in covert attention. PLoS One. 8(1):e52955. [CrossRef]

- Solé Puig M, Pallarés JM, Perez Zapata L, Puigcerver L, Cañete Crespillo J, Supèr H (2016). Attentional selection accompanied by eye vergence as revealed by event-related brain potentials. PloS One 11 (12), e0167646.

- Solé Puig M, Romeo A, Cañete Crespillo J, Supèr H (2017) Eye vergence responses during a visual memory task. Neuroreport 28 (3), 123-127.

- Valenti, R., Staiano, J., Sebe, N., Gevers, T. (2009). Webcam-Based Visual Gaze Estimation. In: Foggia, P., Sansone, C., Vento, M. (eds) Image Analysis and Processing – ICIAP 2009. ICIAP 2009. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 5716. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Varela P, Esposito FL, Morata I, Capdevila A, Solé Puig M, de la Osa N, Ezpeleta L, Faraone SV, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Cañete J, Supèr H (2018). Clinical validation of eye vergence as an objective marker for diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in children. J. Att. Disorder. [CrossRef]

- Viguier, A., Clement, G., & Trotter, Y. (2001). Distance perception within near visual space. Perception, 30, 115–124.

- Wang, Zhiyong and Chai, Jinxiang and Xia, Shihong (2019) Realtime and Accurate 3D Eye Gaze Capture with DCNN-based Iris and Pupil Segmentation. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).