1. Introduction

Gene therapy holds great promise for treating genetic diseases since it directly addresses the root of the problem. By correcting mutations, gene therapy has the potential to cure thousands of hereditary diseases. The discovery of CRISPR/Cas9 in 2012 marked a milestone in the development of gene therapies [

1]. This system uses a Cas9 nuclease inducing a DNA double-strand break at a precise location in the genome. Cas9 is directed to the desired genome sequence by a single guide RNA (sgRNA) [

2]. This sgRNA is a single-stranded RNA complementary to an 18-24 nucleotides (nt) DNA sequence [

3,

4]. The Cas9 protein forms a complex with the sgRNA and binds to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) in the DNA. This complex induces a cut at 3 nt upstream of the PAM [

5]. Depending on the microorganism of origin of the Cas9, this PAM sequence varies. For example, the most widely used Cas9 is from

Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), which recognizes an NGG PAM [

6]. After the nuclease has induced a double-strand break at the desired site, the cell will repair this cut by Homology Directed Repair (HDR) if a donor sequence is provided. However, the percentage of correction of a precise nucleotide mutation by HDR is too low to be used to treat hereditary diseases

in vivo [

7]. If no donor sequence is provided, the cell will repair the cut by Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and it will produce indels [

8].

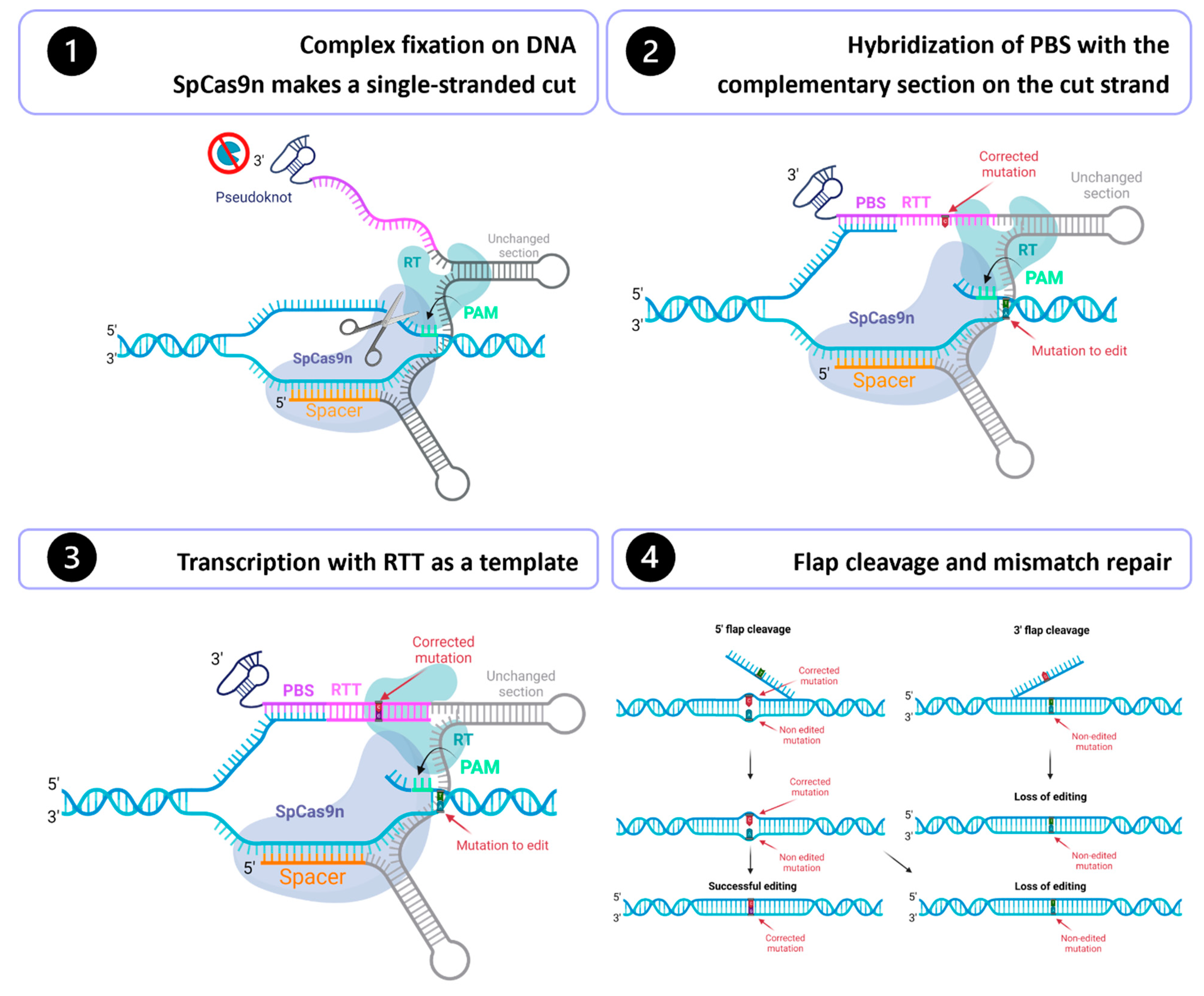

In October 2019, David R. Liu's group published an outstanding technique called Prime editing [

9]. This system can perform targeted insertions, deletions, and all 12 possible base conversions. This technology performs DNA modifications with unprecedented precision and offers substantial advantages over the traditional CRISPR/Cas9 system and the base editing, which is also derived from the CRISPR technology (

Table 1). The Prime editing technology is composed of a Cas9 nickase fused in the C-terminus with a reverse transcriptase (RT) and uses a Prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) (

Figure 1). Cas9 nickase fused with the reverse transcriptase forms the Prime editor (PE). The pegRNA is a modified sgRNA and consists of 1) the sgRNA spacer sequence, 2) the scaffold, a common region of the sgRNA that binds to the SpCas9 fused with a reverse transcriptase, 3) a primer binding site (PBS) and 4) a reverse transcriptase template (RTT), which contains the desired edits [

9] (

Figure 1). To prevent the rapid degradation of the PBS and RTT fragments by exonucleases, an additional 3’ RNA sequence forming double strand loops has been added [

10]. These modified pegRNA are called engineered pegRNA (epegRNA).

Many strategies have been developed for Prime editing, numbered PE1, PE2, PE3, PE4, PE5 and PE6 [

11]. For a PE2 gene modification, the complex formed by the Prime editor and the epegRNA initially binds to the genome, guided by the pegRNA spacer sequence. The SpCas9 nickase (H840A) recognizes a PAM and induces a single-strand break 3 nt upstream [

9]. Next, the PBS sequence binds to its complementary sequence on the cut strand. The reverse transcriptase then uses the RTT sequence as a template to synthesize a new DNA strand. At this stage, one of the strands has a duplicated section (called 5′ flap and 3′ flap), so the cell will have to eliminate one of the two flaps to reconstitute the double-stranded DNA. If a 3′ flap is kept, the correction will be retained, but editing will be lost if a 5′ flap is kept [

9].

Table 1.

Comparison of advantages and disadvantages of CRISPR/Cas9, base editing, and prime editing systems.

Table 1.

Comparison of advantages and disadvantages of CRISPR/Cas9, base editing, and prime editing systems.

| |

CRISPR/Cas9 |

Base Editing |

Prime Editing |

Off-target

effects

|

Significant off-target effects |

Little or no off-target effects |

Little or no off-target effects |

● Possibility of non-specific indels at the Double Strand Break (DSB) site [12];

● DNA donor template can lead to plasmid integration in the genome;

● Possible genome-wide off-targets. |

● No DSB;

● Bystander base edits within a narrow window of 4–10 nt [13];

● Genome-wide off-target studies need to be made. |

● No DSB;

● No bystander edits;

● Genome-wide off-target studies need to be made. |

| Flexibility |

● Can introduce insertions, deletions, and all types of substitutions. |

● Can introduce C > T, G > A, A > G, T > C and C > G substitutions only.

● The consideration of bystander edits makes base editing more stringent on the possible sites [13]. |

● Can introduce insertions, deletions, and all types of substitutions.

● Less stringent PAM requirements [14]. |

| Programmability 1 |

Only if a DNA donor template is required |

Yes |

Yes |

Efficient in vivo

delivery

|

Currently possible |

Currently possible

(but more difficult than CRISPR/Cas9 because of its larger size) |

Need to be improved

(too big for conventional vehicles) |

To edit the DNA, the desired correction must be introduced in the RTT sequence, as it provides the template for transcription.

The position of the mutation induced by Prime editing is given relative to the original SpCas9n-RT and pegRNA cleavage site. Thus, nucleotides downstream of this site will have a positive position (for example, +5 means five nucleotides after the cleavage site towards 3′), and nucleotides upstream of the cleavage site will have a negative position (for example, -5 means five nucleotides before the cleavage site towards 5′).

PE3 is similar to PE2 described above but uses an additional nicking sgRNA (nsgRNA) to induce a nick in the strand not initially cut by the SpCas9n-RT guided by the pegRNA. This additional cut forces the cell to rely on the DNA strand initially cut by the SpCas9nRT as a template. This increases the probability of retaining the edit at the mismatch repair stage. PE3 is thus more effective than the PE2 method.

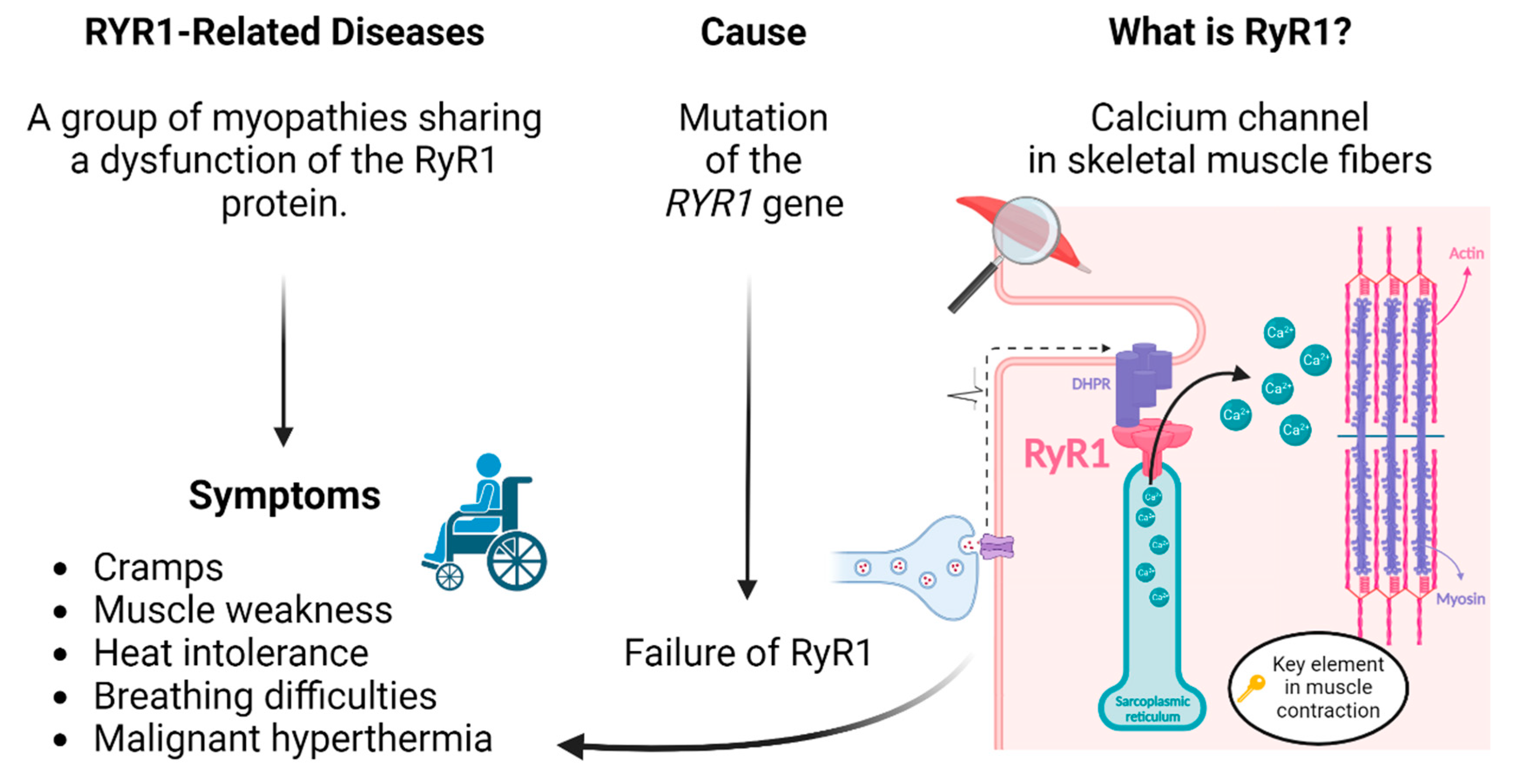

The Prime editing technology may be used to correct mutations causing RYR1-related myopathies. This group of diseases includes malignant hyperthermia (MH), central core disease (CCD), multi-minicore disease (MmD), centronuclear myopathy (CNM), congenital fibre type disproportion (CFTD) and exertional rhabdomyolysis (ERM), just to name a few [

15]. Those diseases all have in common that they are due to a mutation in the

RYR1 gene. To date, more than 700 variants in the

RYR1 gene have been identified [

16]. This gene codes for a protein called "ryanodine receptor 1" (RyR1), which is the principal calcium channel in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) in skeletal muscle fibres [

15] (

Figure 2). The dysfunction of this protein affects the flow of calcium into muscles. The position of the mutation will affect the impact on the protein, but mutations in the genes will mostly lead to a calcium leak. As calcium is critical to muscle contraction, the dysregulation of RyR1 leads to muscle weakness, cramps, exhaustion, heat intolerance, breathing difficulties and even the malignant hyperthermia reaction. Unfortunately, it also mostly degenerates into motor disability. These myopathies, therefore, severely affect the quality of life of patients. The RyR1 protein has limited functional variations, and the

RYR1 gene is one of the most intolerant to sequence variations in the human genome [

17].

So far, there is no effective treatment for these RYR1-related diseases. Since many mutations in the RYR1 genes are point mutations, the results described in the present article clearly demonstrate that Prime editing can be used to correct them, since it can substitute any nucleotide in the genome.

The present article reports the correction of one of these mutations (i.e., the T4709M) as an example. This particular mutation was selected because there is a mouse model (Ryr1TM/Indel) with that mutation that develops clear symptoms [

18].

2. Materials and Methods

Cell lines

The normal human myoblasts were obtained from a muscle biopsy of a healthy cadaveric donor. Fibroblasts derived from a skin biopsy of a patient with a heterozygous T4709M mutation were obtained from Dr Dowling Laboratory.

Plasmids

The pCMV-PE2 (Prime editor) and pU6-tevopreq1-GG-acceptor plasmids were bought from AddGene (AddGene plasmids #132775 and #174038). Cloning in these plasmids was done as described by Anzalone et al. [

9] to make the epegRNA plasmids. Our laboratory however modified the plasmid #174038 to include a second U6 promoter and a cloning site to insert the nsgRNA for the PE3 method (plasmid subsequently called epegRNA-nsgRNA). Oligonucleotides used for the construction of epegRNAs and nsgRNAs were purchased from IDT Inc. (Coralville, IO, USA). All spacer, PBS, RTT and nsgRNA sequences are in

Table S1.

Cell culture

HEK293T cells and human fibroblasts were grown in DMEM medium (Wisent Inc., Quebec, Canada) supplemented with 10% FBS (Wisent Inc.) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Wisent Inc.) at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator.

The human myoblasts were grown in a homemade medium made of 4 volumes of DMEM medium for 1 volume of medium 199 (Invitrogen™ Inc., Carlsbad, United States) supplemented with: Fetuin 25 μg/mL (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA), hEGF: 5 ng/mL (Life Technologies), bFGF: 0.5 ng/mL (Life Technologies), Insulin: 5 μg/mL (Sigma-Aldrich Canada Inc., 91077C-1G), Dex: 0.2 μg/mL (Sigma-Aldrich Canada Inc.).

Transfection of HEK293T cells

The day before transfection, the HEK293T cells were detached from the flask with a Trypsin–EDTA solution (Sigma-Aldrich Canada Inc., Oakville, Canada) and counted. Detached cells were plated in a 24-well plate at a density of 60,000 cells per well with 500 μL of culture medium. Cells were transfected with 1 μg of total DNA (500 ng of each plasmid, i.e., the plasmid coding for Prime editor and the plasmid coding for the epegRNA and the nsgRNA) with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen™ Inc., Carlsbad, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The medium was changed to 1 mL of fresh medium 24 h later and cells were maintained in incubation for 48 h before genomic DNA extraction.

Plasmid electroporation in myoblasts and fibroblasts

A total of 2 μg of plasmids (1 μg of Prime editor plasmid and 1 μg of epegRNA-nsgRNA plasmid (containing the epegRNA sequence and the nsgRNA for PE3) were added to 100,000 human myoblasts or fibroblasts and electroporated with the 10 μl Neon Transfection System (program: 1,100 volts /20 ms /2 pulses). These electroporated cells were added to one well of a 24-well culture plate containing 500 μL of the homemade medium. The electroporation medium was changed with 1 mL fresh medium after 24 h. Cells were detached with trypsin and harvested in 1 mL culture medium 48 h later, and DNA was extracted from these cells.

PE mRNA in vitro transcription

The Prime editor plasmid was first amplified by PCR to add optimized 5’ UTR regions and a poly-A tail in 3’ (

Table S2). The resulting PCR product was purified with the PCR Products Purification Kit (EZ-10 Spin Column) (Bio Basic) and served as a template for subsequent

in vitro transcription. Prime editor mRNAs were transcribed from this template using the HiScribe T7 mRNA Kit with CleanCap Reagent AG (New England BioLabs, IncIpswich, MA, USA) with complete replacement of UTP with N1-Methylpseudouridine-triphosphate (TriLink Biotechnologies Inc., San Diego, USA). The reaction mixture was incubated at 37

oC for 4 h. The reaction volume was then brought up to 50 µL with nuclease-free water. 2 µL of DNase I were added to the reaction mixture. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes. Transcribed mRNAs were purified with the Monarch RNA Cleanup Kit (500 µg) (New England BioLabs Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA), eluted in 1 mM Sodium Citrate pH 6.4, and quantified by BioDrop. PE mRNAs were then stored at -80

oC.

RNA electroporation in myoblasts

A total of 3.7 μg of RNA (0.5 μg of PE mRNA, 2.3 μg of epegRNA (chemically synthetized by IDT Inc. Coralville, IO, USA) and 0.9 μg of nsgRNA (chemically synthetized by IDT Inc. Coralville, IO, USA) were added to 50,000 human myoblasts and electroporated with the 10 μl Neon Transfection System (program: 1,100 volts /20 ms /2 pulses). These electroporated cells were added to one well of a 24-well culture plate containing 500 μL of the homemade medium. The electroporation medium was changed with 1 mL fresh medium after 24 h. Cells were detached with trypsin and harvested in 1 mL culture medium 48 h later, and DNA was extracted from these cells. For multiple treatments, three replicates were placed in one well of a 6-well culture plate containing 3 mL of the homemade medium after electroporation. 1 mL of this well was taken and put in one well of a 24-well plate. 1 additional mL of homemade medium was added to wells in the 6-well plate to reach a total of 3 mL of medium per well. Medium was changed after 24 hours. Cells in the 24-well plate were harvested for DNA extraction after 48 hours. When cells in the 6-well plate were confluent, they were passed in a T25 flask. When confluent, a sample of these cells were treated again by electroporation.

Genomic DNA preparation and PCR amplification

HEK293T cells were detached from wells directly with up and down pipetting of the culture medium and transferred in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes. Human myoblasts were detached using Trypsin–EDTA solution (Sigma-Aldrich Canada Inc.) and collected in 1 mL of the homemade medium. HEK293T cells or human myoblasts were centrifuged for 5 min at 8000 RPM at room temperature. Cell pellets were washed once with 1 mL of PBS 1× and centrifuged again for 5 min at 8,000 RPM. Genomic DNA was prepared using the DirectPCR Lysis Reagent (Viagen Biotech Inc., Los Angeles, USA). Briefly, 50 μL of DirectPCR Lysis Reagent containing 0.5 μL of a proteinase K solution (20 mg/mL) were added to each cell pellet and incubated 2 hours at 56°C followed by another incubation at 85°C for 45 min and centrifugation at 13,000 RPM for 5 min. 1 μL of each genomic DNA preparation (supernatant) was used for the PCR reaction. PCR temperature cycling was performed as follows: 98°C: 30 s and 35 cycles of 98°C: 10 s, 60°C: 20 s, 72°C: 30 s,) and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min was also performed. We used Phusion™ High-Fidelity DNA polymerase from Thermo Scientific Inc. (Massachusetts, USA) for all PCR reactions. The primers used for the PCR are listed in

Table S2. 2 μL of amplicons were electrophorized in 1X TBE buffer on 1% agarose gel to control the PCR reaction qualities and to make sure that only one specific band was present.

Deep sequencing analysis

Deep sequencing samples were prepared following the PCR protocol described above, but with different primers (

Table S2) for subsequent deep sequencing. PCR samples of 300 bp amplicon length were sent to Genome Quebec Innovation Centre at McGill University (

https://cesgq.com/en-services#en-sequencing) to sequence amplicons with the Illumina sequencer. Illumina sequencing results were analyzed with the CRISPResso 2 online program (

http://crispresso2.pinellolab.org/submission) according to the authors’ guidelines [

20].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the GraphPad PRISM 10.0.3 software package (Graph Pad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

4. Discussion

As prime editing can perform insertions, deletions and all types of substitutions, it can potentially correct all point mutations that cause inherited diseases. Prime editing can also generate cell lines or animal models for specific mutations, thereby driving forward research into many genetic diseases [

26]. To date, many

in vitro and

in vivo preclinical studies have shown that Prime editing enables the precise correction of mutations in the genome [

26]. In the field of human gene therapy, Prime editing has been attempted

in vitro and

in vivo for hereditary liver diseases (DGAT1-deficiency [

27], bile salt export pump deficiency [

27], alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency [

28,

29], phenylketonuria [

30], and tyrosinemia type 1 [

31,

32,

33]), eye diseases (Leber congenital amaurosis [

31], Cataracts [

34] and X-linked retinitis pigmentosa [

35]), skin diseases (Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa [

36] and Oculocutaneous albinism [

37]), Duchenne muscular dystrophy [

21,

38] and neurodegenerative diseases (Tay–Sachs disease [

39] and Alzheimer’s Disease [

40]), as well as cystic fibrosis [

41], beta-thalassemia [

42], sickle cell disease [

43], X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency [

44] and cancer [

37,

45].

The present work is the first demonstration of an efficient preclinical gene therapy for RYR1-related diseases in the scientific literature.

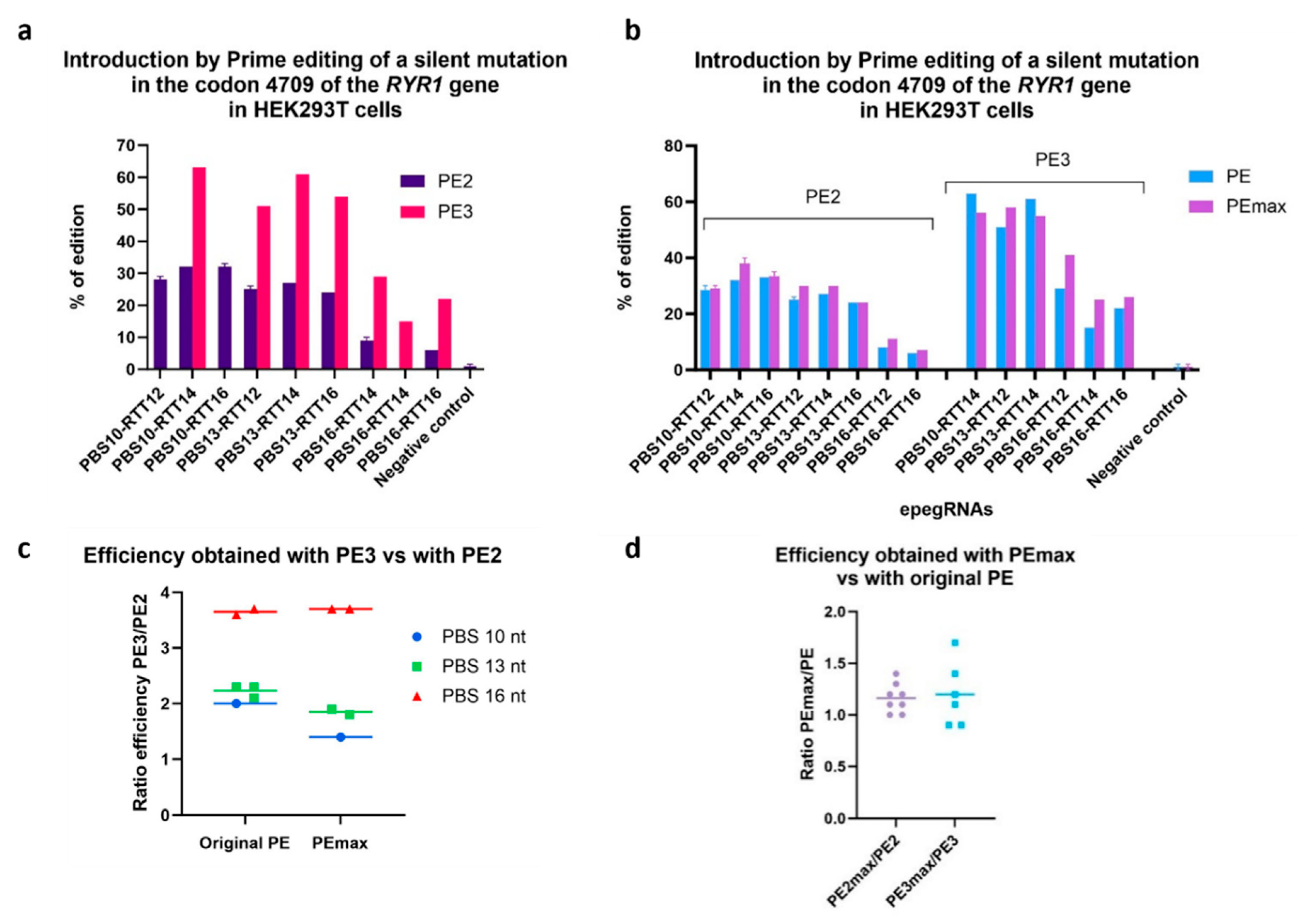

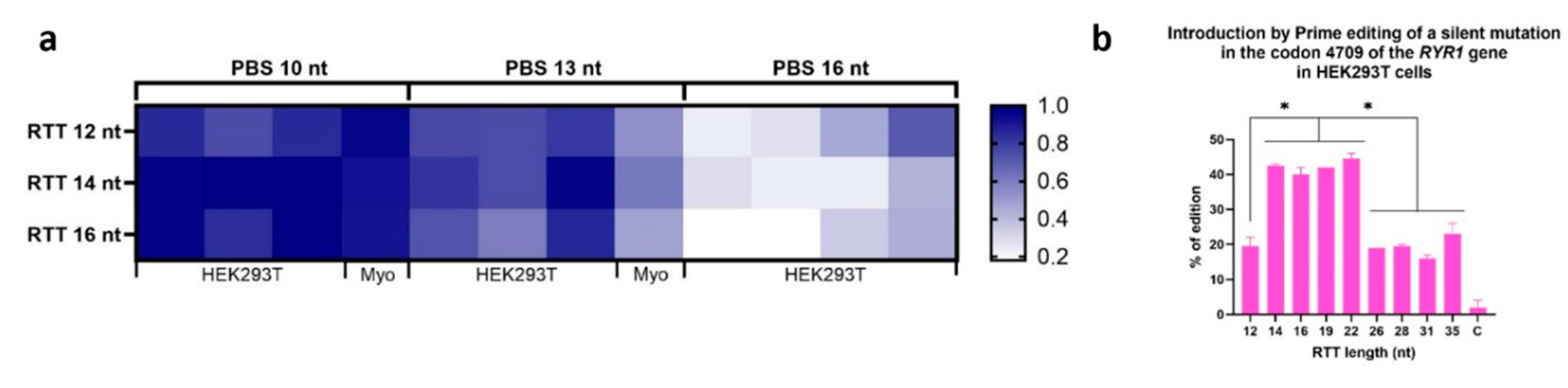

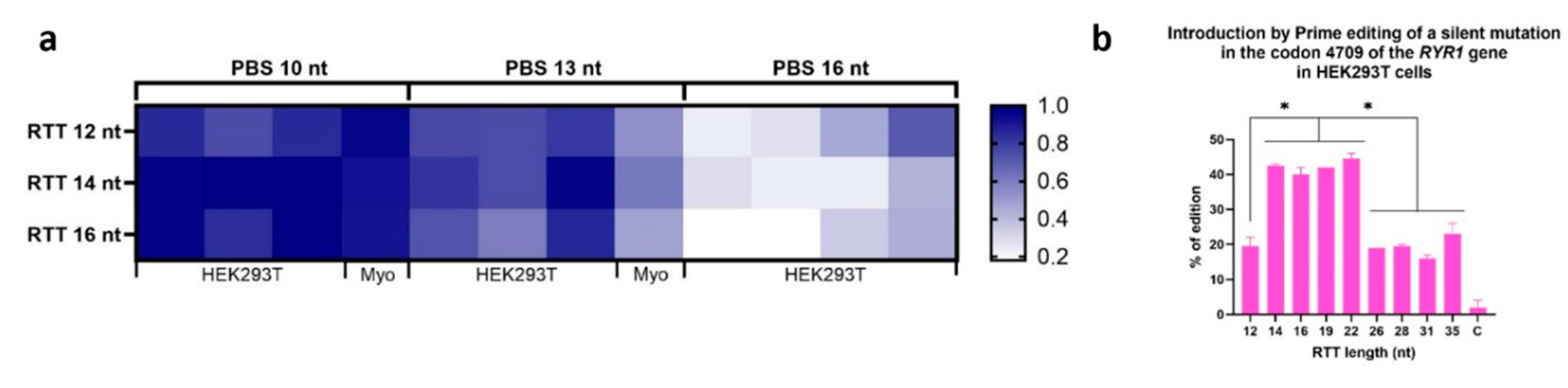

As indicated in the original article of Anzalone et al. [

9], for each point mutation to be corrected, the best epegRNA sequence has to be identified by trying several epegRNAs with different lengths of PBS and RTT. In this study, the length of the PBS was more restrictive than the length of the RTT. Varying the PBS length from 10 nt, 13 nt and 16 nt impact heavily the efficiency. Thus, for the T4709M locus, a smaller PBS of 10 nt was the best option. A recent article recommended a PBS of 7 nt to improve Prime editing by preventing inhibitory interactions between the PBS and the spacer sequences of the epegRNA [

46]. For the RTT, many lengths gave the same efficiency. RTT of 14 nt 16 nt, 19 nt and 22 nt gave the best efficiency and were not significantly different. As Prime editing optimization seems to be sequence specific, those conclusions may not apply to other targets [

19,

47].

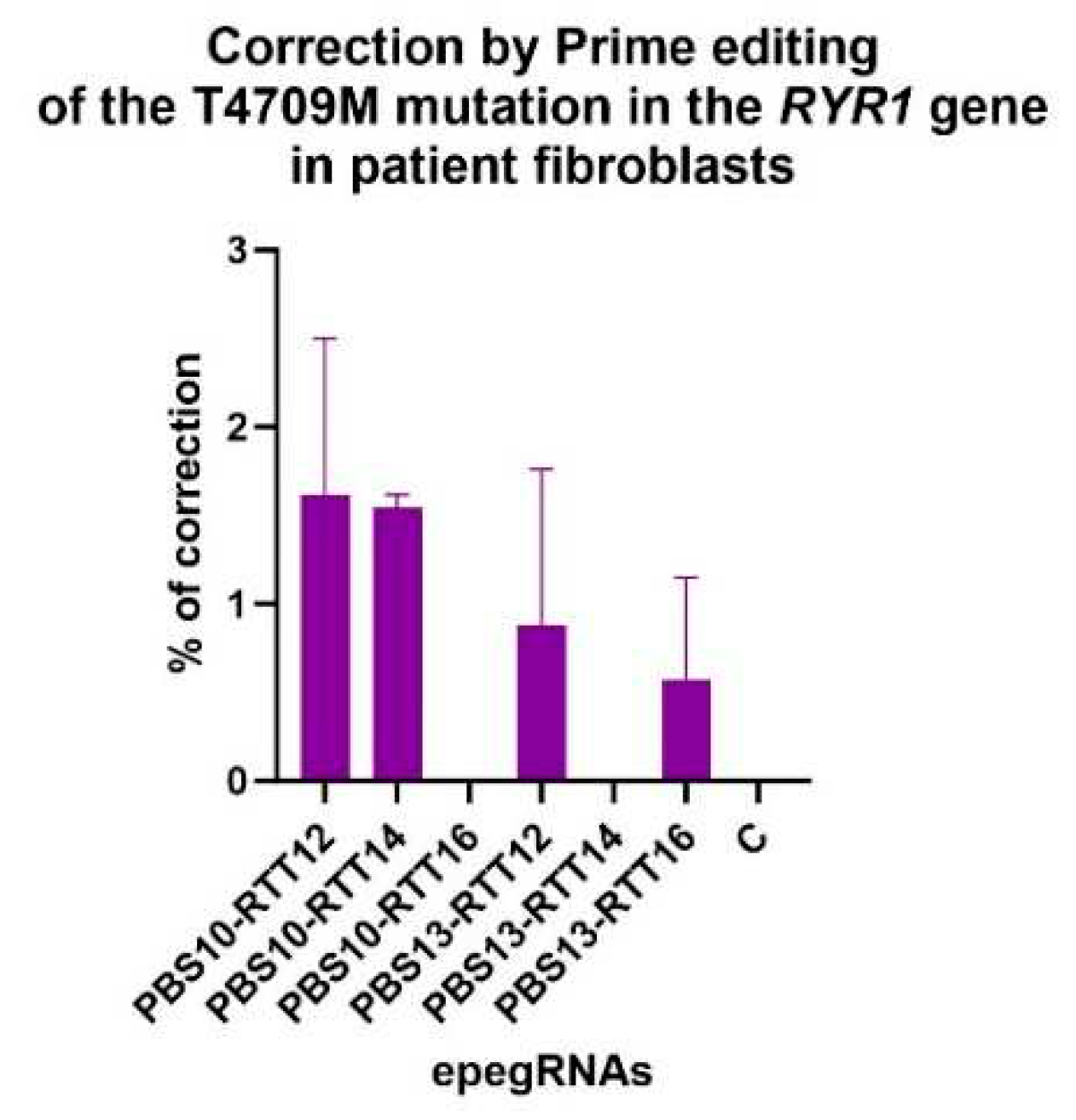

No significant editing of the T4709M mutation of the

RYR1 gene was obtained in the patient fibroblasts. Our hypothesis is that, since the

RYR1 gene is not expressed in fibroblasts [

48], but only in skeletal muscles, the region to edit must not be easily accessible to Prime editing components. However, this experimental constraint will be an advantage in future clinical applications. In fact, genome editing will only be carried out in skeletal muscles, so the off-target risks in other tissues are practically offset.

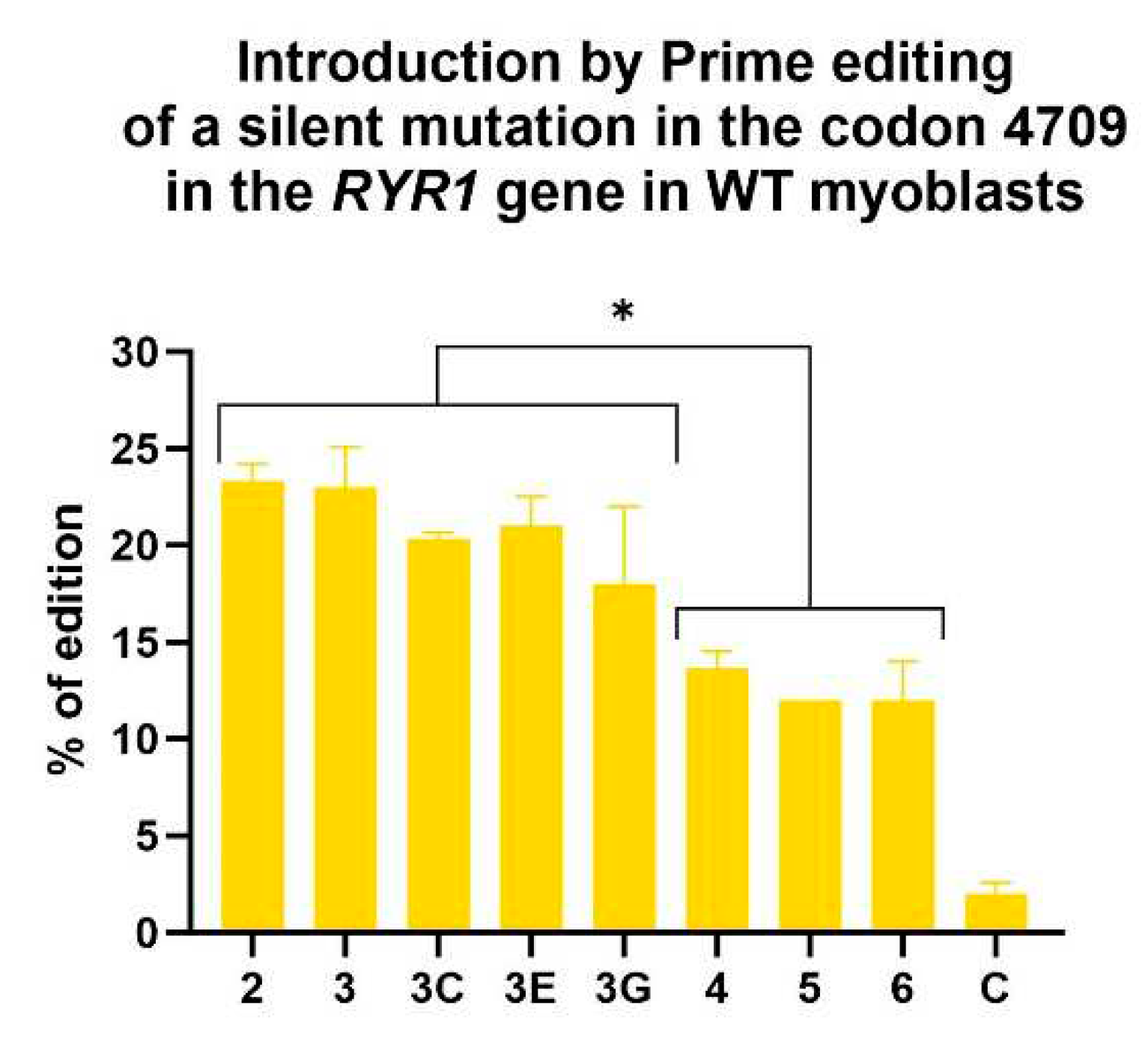

Testing the Prime editing treatment in WT myoblasts allowed to narrow the epegRNA choice for the next steps. EpegRNAs with a PBS of 10 nt outperformed epegRNAs with a PBS of 13 nt. Thus, for the next experiments, epegRNAs with a PBS of 10 nt will be used since 23% of editing were obtained in WT myoblasts and more than 40% in HEK293T cells. This result is not surprising as HEK293T are easy to transfect cells and have a deficient mismatch repair system [

49], which increases Prime editing efficiency.

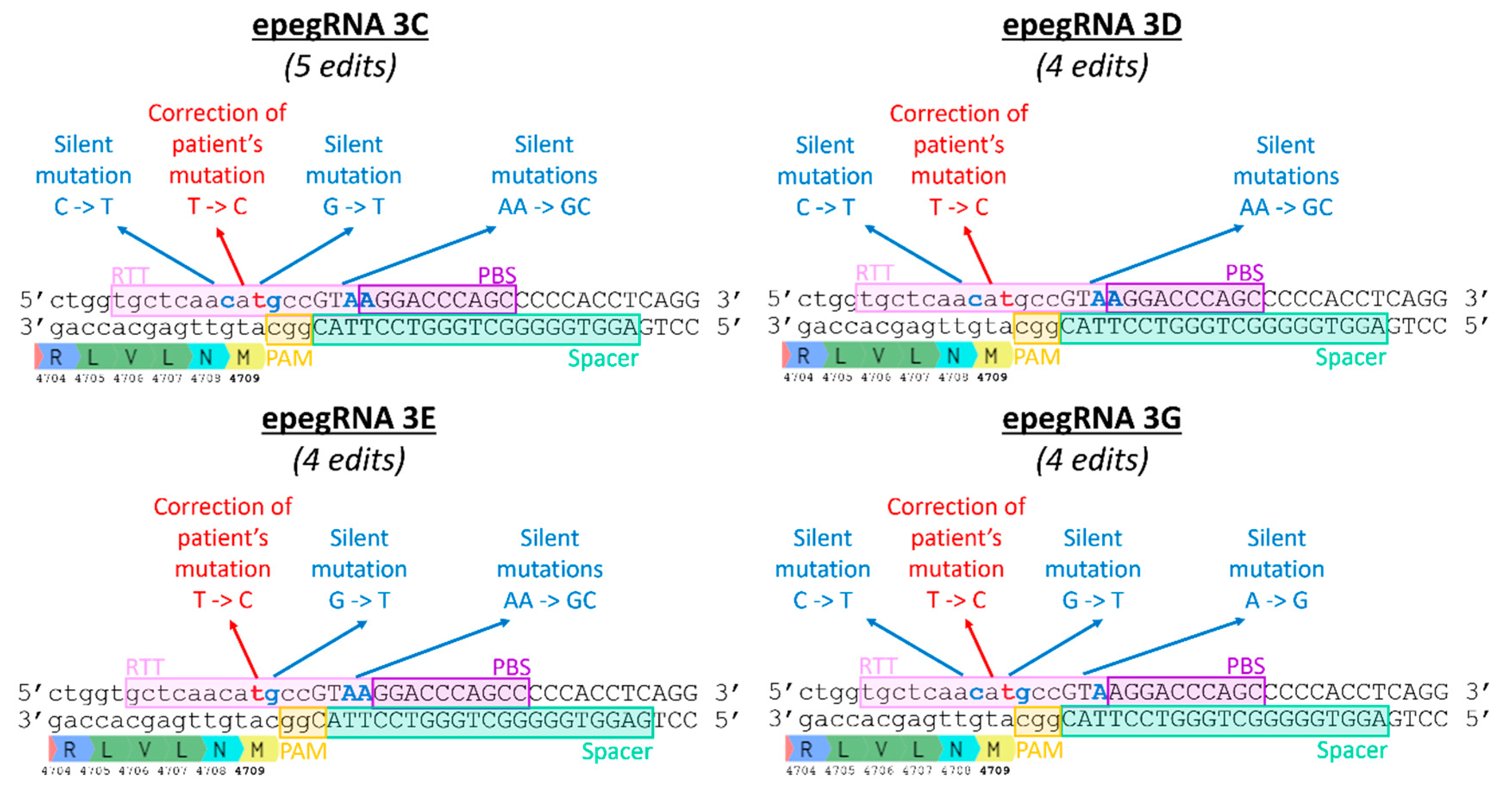

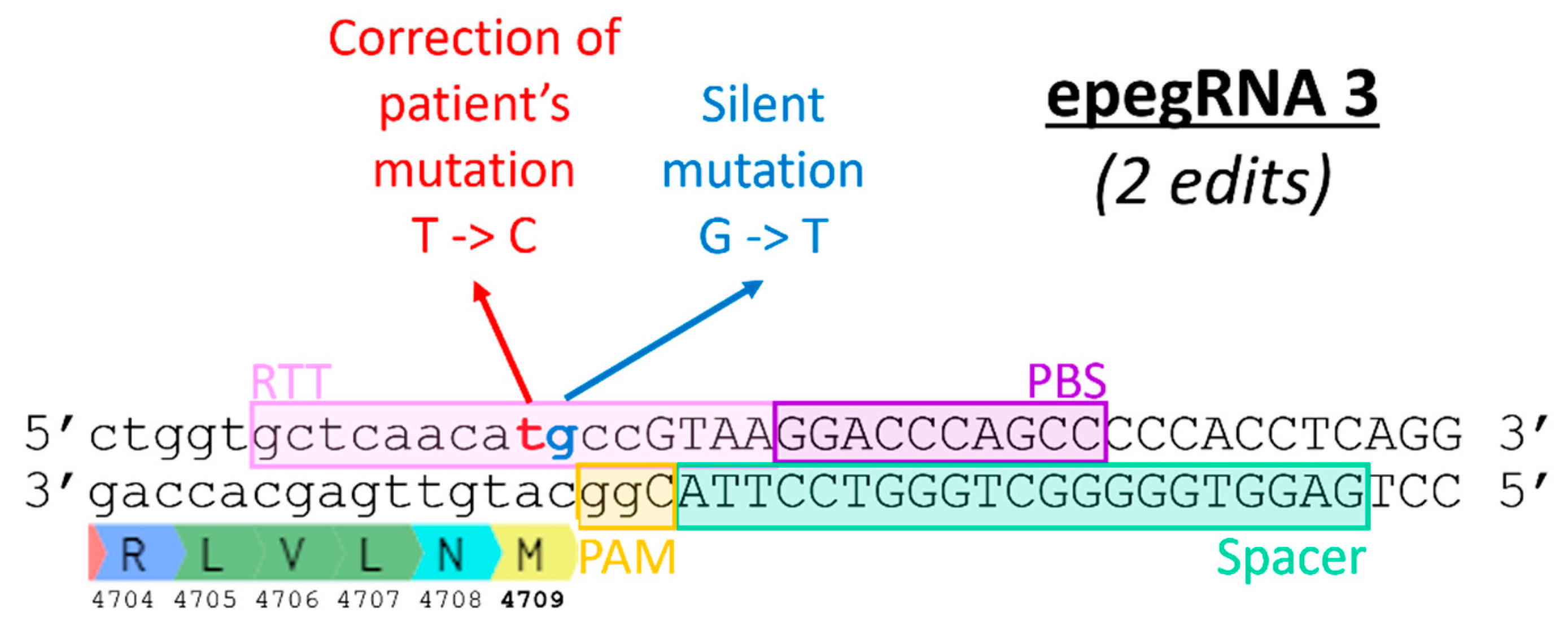

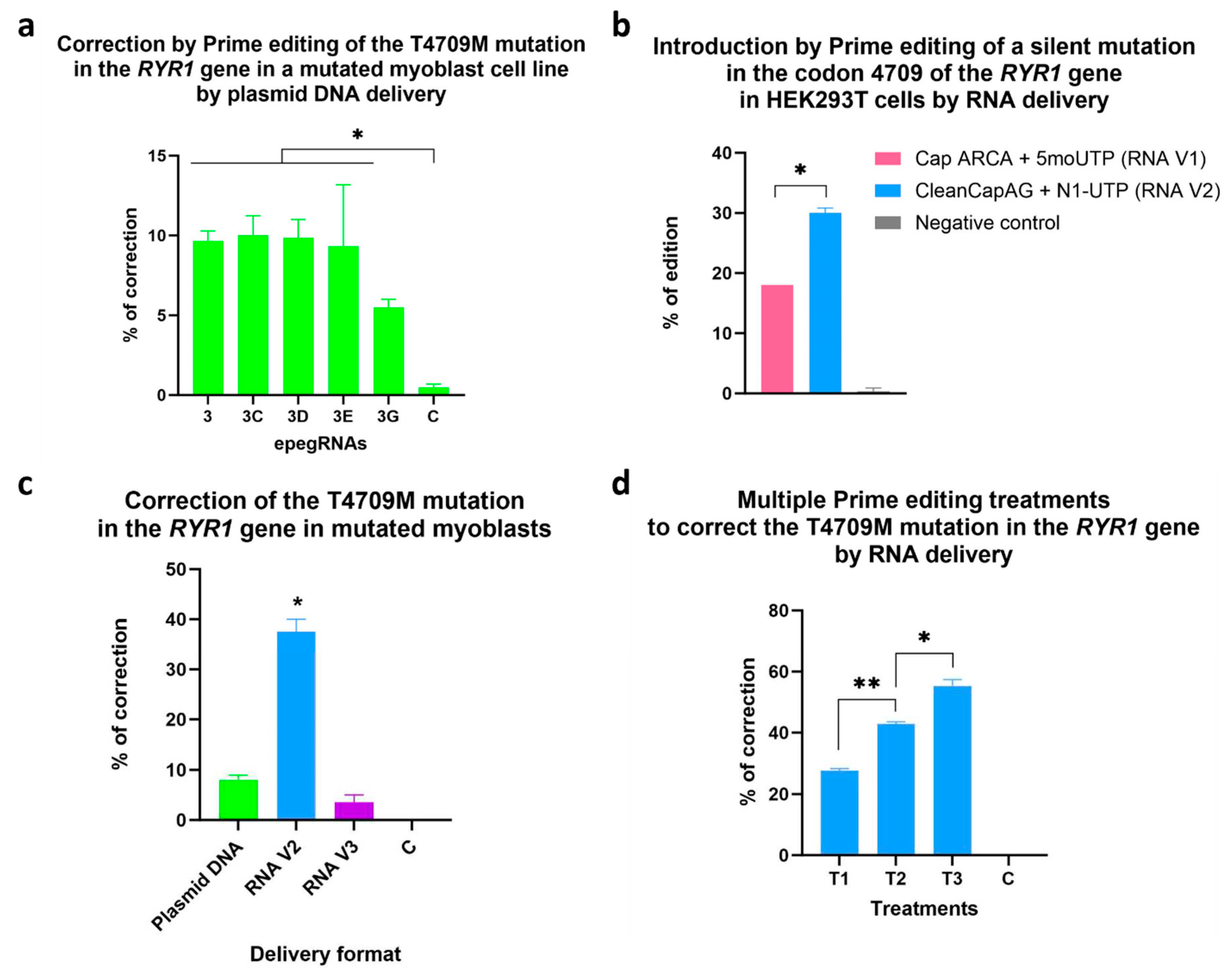

A strategy to bypass the mismatch repair system of the cells is to introduce additional silent mutations in the RTT [

11,

21]. New epegRNAs 3C, 3D, 3E and 3G were therefore constructed to test this strategy for the

RYR1 gene (Fig. 8 and

Table 3). However, adding additional silent mutations did not led to an improvement. We also tested the hypothesis that mutating the first two nucleotides (AA) of the RTT (which are also common to the spacer) (Fig. 8) would simulate the effect of a mutation in the PAM. Our hypothesis was therefore that these mutations would limit subsequent spacer attachment. However, editing rates were not significantly different from the original constructions that did not include additional edits.

While generating the myoblast cell line with the T4709M mutation in the

RYR1 gene, the manual cloning allowed us to detect an unwanted rare event. In addition to the desired mutation, we observed an undesired substitution at the heterozygous state. This indel was created because the reverse transcriptase continued to reverse transcribe even after the end of the RTT sequence. In the epegRNA, the RTT sequence is followed by the epegRNA scaffold sequence that binds to the Cas9 protein. The first nucleotide of this scaffold sequence was incorporated into the T4709M mutated cell line. Chen et al. [

11] also observed this kind of off-target. The scaffold sequence should be optimized to avoid this type of off-target event. The sequence could be modified as the first part of the scaffold sequence after the RTT makes a stronger double-stranded RNA by inserting C and G nucleotides at adequate positions. Providing a longer RTT sequence may also be investigated.

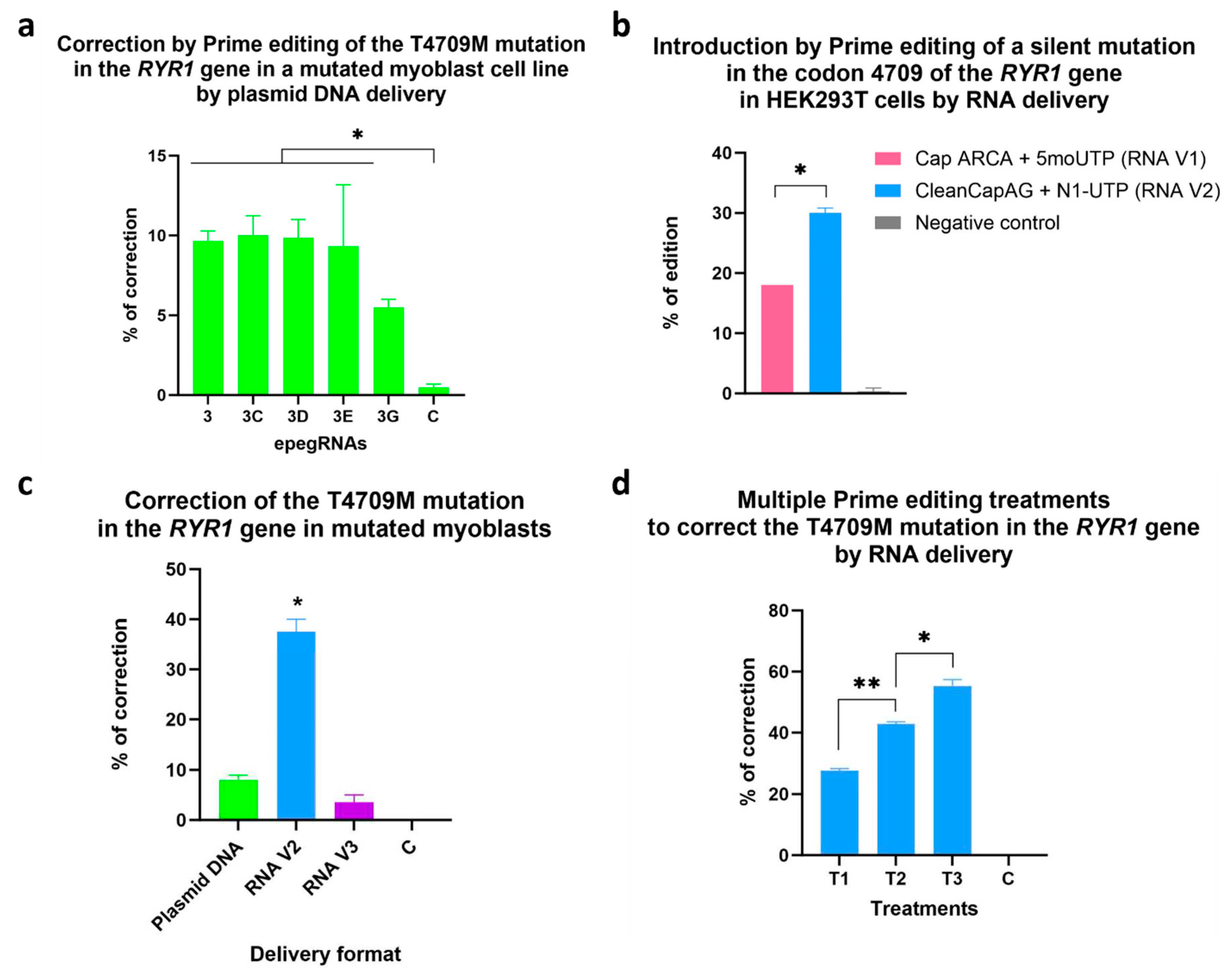

In the myoblast cell line possessing the T4709M mutation in the RYR1 gene at the homozygous state, 10 to 13% of correction were obtained. The adjacent silent mutation had the same editing rate. The lower Prime editing efficiency in that cell line compared to in WT myoblasts may be explained by the history of the cells. The T4709M cell line was generated by four electroporation treatments followed by manual cloning. Those events affected the cells and may have made them more sensitive to additional electroporation treatments.

The form in which the Prime editing components are delivered can significantly impact editing efficiency. For example, Li et al. [

50] used Prime editing to introduce substitutions in the SNCA gene in human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs). They compared the efficiency when using a PE2 treatment by delivering the components as the plasmids, mRNAs or ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) and obtained about 5%, 26.7%, and 1% editing efficiency, respectively. Our results point towards the same conclusion. Delivering the Prime editing components as RNAs dramatically increased the Prime editing efficiency and increased cell viability as RNA is less toxic to cells than DNA.

Up to 59% of corrections were obtained by RNA delivery in the T4709M myoblast cell line. This result is encouraging since persons heterozygous for this mutation are healthy.

Our results are the first demonstration that it is possible to correct mutations in the RYR1 gene. This project paves the way for treating RYR1-related myopathies by gene therapy. These breakthroughs will significantly impact the treatment of other hereditary diseases. Indeed, this method can be applied to other genetic mutations, and in each case, only the epegRNA would have to be modified!

Figure 1.

Prime editing mechanism. Step 1: Guided by the spacer sequence of the pegRNA, the Cas9 nickase fused with a reverse transcriptase (RT) binds to the DNA at the desired place in the genome. The Cas9n recognizes a PAM and induces a single-stranded nick 3 nt upstream. Step 2: The PBS hybridizes to its complementary sequence on the cut strand. Step 3: The RT uses the RTT as a template to synthesize a new DNA strand. Step 4: One DNA flap (either the 5’ flap or a 3’ flap) is removed.

Figure 1.

Prime editing mechanism. Step 1: Guided by the spacer sequence of the pegRNA, the Cas9 nickase fused with a reverse transcriptase (RT) binds to the DNA at the desired place in the genome. The Cas9n recognizes a PAM and induces a single-stranded nick 3 nt upstream. Step 2: The PBS hybridizes to its complementary sequence on the cut strand. Step 3: The RT uses the RTT as a template to synthesize a new DNA strand. Step 4: One DNA flap (either the 5’ flap or a 3’ flap) is removed.

Figure 2.

RYR1-related diseases: cause and symptoms.

Figure 2.

RYR1-related diseases: cause and symptoms.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the efficiency obtained using the PE2, PE3 and PEmax strategy. The efficiency of various technological variations of the Prime editing technique was tested by inserting a silent mutation in codon 4709 of the RYR1 gene in HEK293T cells. a. Illustration of the results using the PE2 and the PE3 methods. b. Illustration of the PE2 and PE3 methods using the PE and the PEmax strategies. c. The figure illustrates the ratio of the percentage of gene edition obtained with PE3 relative to the percentage obtained with PE2. d. Illustration of the ratio of PE2max edition relative to PE2, and of PE3max relative to PE3.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the efficiency obtained using the PE2, PE3 and PEmax strategy. The efficiency of various technological variations of the Prime editing technique was tested by inserting a silent mutation in codon 4709 of the RYR1 gene in HEK293T cells. a. Illustration of the results using the PE2 and the PE3 methods. b. Illustration of the PE2 and PE3 methods using the PE and the PEmax strategies. c. The figure illustrates the ratio of the percentage of gene edition obtained with PE3 relative to the percentage obtained with PE2. d. Illustration of the ratio of PE2max edition relative to PE2, and of PE3max relative to PE3.

Figure 4.

Effect of varying PBS length and RTT on editing efficiency. a. The darker the box is, the higher is the percentage of editing. This heatmap also summarizes the effects of varying the length of RTT and PBS tested under different conditions (PE2, PE3, PE2max, PE3max) and in different cell types (HEK293T and myoblasts), in order to compare only the effects of RTT length and PBS, i.e., without considering the effect of the strategy used or the cell type used. For each sample, the ratio of its efficiency value to the highest efficiency value obtained in the same experiment under the same condition was calculated. A value of 1 thus indicates that this sample obtained the best editing efficiency in the experiment. In order from left to right, the columns represent the following conditions for 10 nt PBS and 13 nt PBS: HEK293T PE2, HEK293T PE3, HEK293T PE2max and Myoblasts PE3. For 16 nt PBS, the columns are as follows: HEK293T PE2, HEK293T PE3, HEK293T PE2max and HEK293T PE3max. Since epegRNAs with 16 nt PBS were significantly less effective in experiments in HEK293T, these epegRNAs were not tested in myoblasts. b. Illustration of the results of inserting a silent mutation in codon 4709 of the RYR1 gene in HEK293T cells while testing different RTT lengths. All the epegs used in this experiment had a PBS containing 10 nt. The length of the RTT was varied from 12 to 35 nucleotides. RTT containing 14 to 22 nucleotides produced the best Prime editing results. One-way ANOVA, multiple comparisons and a p-value of 0.001 were used.

Figure 4.

Effect of varying PBS length and RTT on editing efficiency. a. The darker the box is, the higher is the percentage of editing. This heatmap also summarizes the effects of varying the length of RTT and PBS tested under different conditions (PE2, PE3, PE2max, PE3max) and in different cell types (HEK293T and myoblasts), in order to compare only the effects of RTT length and PBS, i.e., without considering the effect of the strategy used or the cell type used. For each sample, the ratio of its efficiency value to the highest efficiency value obtained in the same experiment under the same condition was calculated. A value of 1 thus indicates that this sample obtained the best editing efficiency in the experiment. In order from left to right, the columns represent the following conditions for 10 nt PBS and 13 nt PBS: HEK293T PE2, HEK293T PE3, HEK293T PE2max and Myoblasts PE3. For 16 nt PBS, the columns are as follows: HEK293T PE2, HEK293T PE3, HEK293T PE2max and HEK293T PE3max. Since epegRNAs with 16 nt PBS were significantly less effective in experiments in HEK293T, these epegRNAs were not tested in myoblasts. b. Illustration of the results of inserting a silent mutation in codon 4709 of the RYR1 gene in HEK293T cells while testing different RTT lengths. All the epegs used in this experiment had a PBS containing 10 nt. The length of the RTT was varied from 12 to 35 nucleotides. RTT containing 14 to 22 nucleotides produced the best Prime editing results. One-way ANOVA, multiple comparisons and a p-value of 0.001 were used.

Figure 5.

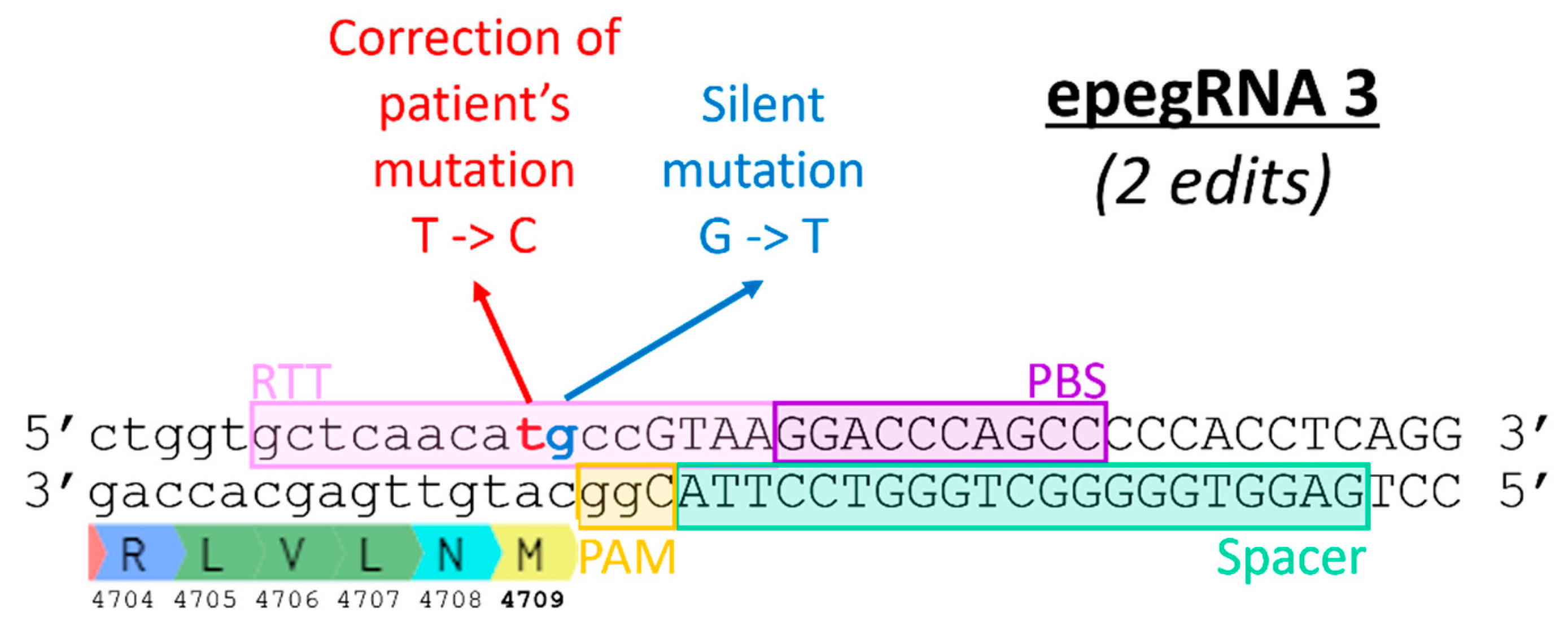

Sequence of the section of the RYR1 gene containing the T4709M mutation. The coding nucleotides are in minuscules, and those in the intron are in capital letters. The sequences necessary to construct an epegRNA that would correct the T4709M mutation are identified (Spacer, PBS and RTT). Note that the sense strand is on the top of the figure. Thus, the PAM (5’Cgg3’) is in the antisense strand, and it is the antisense strand that will be nicked by the SpCas9 nickase part of the PE. The normal 4709 codon is ACG coding for threonine. In the patient, this codon is mutated to ATG coding for methionine. For correcting the patient mutation, a C will have to be inserted in the RTT sequence (5’ gctcaacaCgccGTAA3’) so that the reverse transcriptase synthesizes a new anti-sense strand containing a 5’cgt3’ threonine anti-sense codon. However, since the experiment was done in HEK293T cells containing the normal RYR1 gene, there was no modification that could be detected by sequencing when using such an RTT. An additional silent mutation was thus inserted in the RTT (5’ gctcaacaCTccGTAA3’) to modify the normal ACG codon into an ACT codon also coding for threonine.

Figure 5.

Sequence of the section of the RYR1 gene containing the T4709M mutation. The coding nucleotides are in minuscules, and those in the intron are in capital letters. The sequences necessary to construct an epegRNA that would correct the T4709M mutation are identified (Spacer, PBS and RTT). Note that the sense strand is on the top of the figure. Thus, the PAM (5’Cgg3’) is in the antisense strand, and it is the antisense strand that will be nicked by the SpCas9 nickase part of the PE. The normal 4709 codon is ACG coding for threonine. In the patient, this codon is mutated to ATG coding for methionine. For correcting the patient mutation, a C will have to be inserted in the RTT sequence (5’ gctcaacaCgccGTAA3’) so that the reverse transcriptase synthesizes a new anti-sense strand containing a 5’cgt3’ threonine anti-sense codon. However, since the experiment was done in HEK293T cells containing the normal RYR1 gene, there was no modification that could be detected by sequencing when using such an RTT. An additional silent mutation was thus inserted in the RTT (5’ gctcaacaCTccGTAA3’) to modify the normal ACG codon into an ACT codon also coding for threonine.

Figure 6.

Correction of the T4709M mutation in patient fibroblasts. Percentage of editing was determined by Illumina deep sequencing. No editing was observed with epegRNAs PBS10-RTT16 and PBS13-RTT14. The editing percentages obtained with the other epegRNAs were not significantly different from the negative control (named C). One-way ANOVA, multiple comparisons and a pvalue of 0.05 were used.

Figure 6.

Correction of the T4709M mutation in patient fibroblasts. Percentage of editing was determined by Illumina deep sequencing. No editing was observed with epegRNAs PBS10-RTT16 and PBS13-RTT14. The editing percentages obtained with the other epegRNAs were not significantly different from the negative control (named C). One-way ANOVA, multiple comparisons and a pvalue of 0.05 were used.

Figure 7.

Insertion by Prime editing in wild-type myoblasts of a silent mutation adjacent to the eventual patient's mutation in the codon 4709 of the RYR1 gene. A one-way ANOVA indicated that the editing values obtained with epegRNAs 2, 3, 3C, 3E and 3G were significantly different from the editing values obtained with epegRNAs 4, 5 and 6. This test also demonstrated that all epegRNAs produced editing values significantly different from the negative control (named C). An ANOVA test with a p-value of 0.05 was used. The 3D epegRNA is not shown in this graph, as it did not insert the same silent mutation adjacent to the patient's mutation.

Figure 7.

Insertion by Prime editing in wild-type myoblasts of a silent mutation adjacent to the eventual patient's mutation in the codon 4709 of the RYR1 gene. A one-way ANOVA indicated that the editing values obtained with epegRNAs 2, 3, 3C, 3E and 3G were significantly different from the editing values obtained with epegRNAs 4, 5 and 6. This test also demonstrated that all epegRNAs produced editing values significantly different from the negative control (named C). An ANOVA test with a p-value of 0.05 was used. The 3D epegRNA is not shown in this graph, as it did not insert the same silent mutation adjacent to the patient's mutation.

Figure 8.

Introduction of additional silent mutations by epegRNAs 3C, 3D, 3E and 3G. The DNA sequence shown is the section of the RYR1 gene where the T4709M mutation is located. The epegRNA sections are identified (Spacer, PBS and RTT). The T4709M mutation is a T instead of a C. In the RTT, a C is therefore inserted at this position to correct the mutation. Silent mutations are added to epegRNAs in an attempt to increase the efficiency of Prime editing.

Figure 8.

Introduction of additional silent mutations by epegRNAs 3C, 3D, 3E and 3G. The DNA sequence shown is the section of the RYR1 gene where the T4709M mutation is located. The epegRNA sections are identified (Spacer, PBS and RTT). The T4709M mutation is a T instead of a C. In the RTT, a C is therefore inserted at this position to correct the mutation. Silent mutations are added to epegRNAs in an attempt to increase the efficiency of Prime editing.

Figure 9.

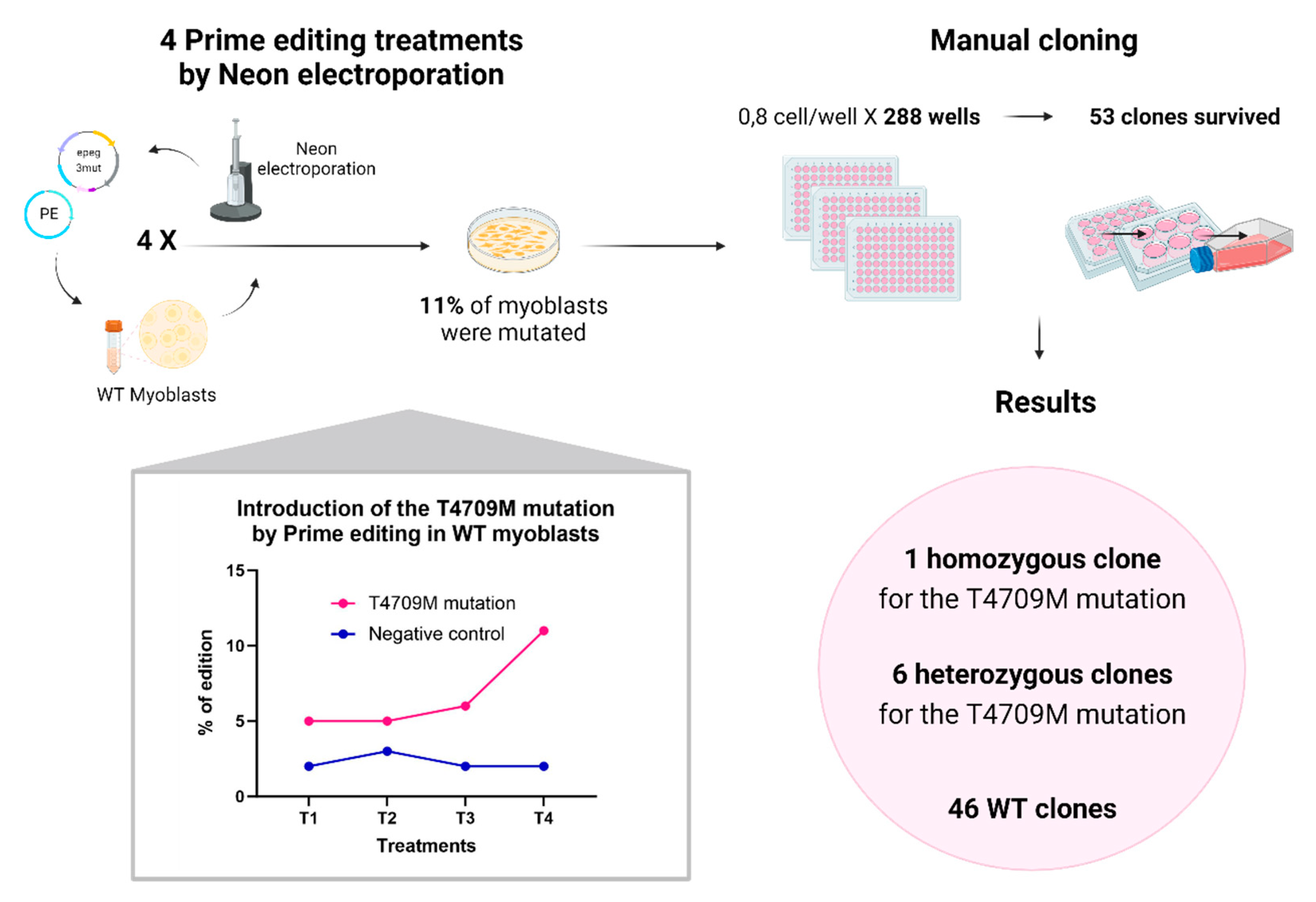

Generation of a cell line homozygous for the RYR1 T4709M mutation by Prime editing on WT myoblasts. Four Neon electroporation treatments were performed on immortalized normal myoblasts to deliver the PE components (plasmids coding for PE, an epegRNA and nsgRNA). After these four treatments, the percentage of introduction of the patient's mutation (T4709M) reached about 11%. Manual cloning was then performed. 0.8 cells were deposited per well in 288 wells of 96-well plates. Only 53 clones survived and multiplied. Of these 53 clones, one turned out to be homozygous for the T4709M mutation, 6 clones turned out to be heterozygous for this mutation, and 46 clones were WT.

Figure 9.

Generation of a cell line homozygous for the RYR1 T4709M mutation by Prime editing on WT myoblasts. Four Neon electroporation treatments were performed on immortalized normal myoblasts to deliver the PE components (plasmids coding for PE, an epegRNA and nsgRNA). After these four treatments, the percentage of introduction of the patient's mutation (T4709M) reached about 11%. Manual cloning was then performed. 0.8 cells were deposited per well in 288 wells of 96-well plates. Only 53 clones survived and multiplied. Of these 53 clones, one turned out to be homozygous for the T4709M mutation, 6 clones turned out to be heterozygous for this mutation, and 46 clones were WT.

Figure 10.

a. Correction by Prime editing of the T4709M mutation in the RYR1 gene in a myoblast line possessing this mutation at the homozygous state by delivering the Prime editing components by plasmid DNA. Experiments were performed in triplicates. The figure illustrates the percentage of correction obtained after one treatment of Prime editing delivered by plasmid DNA. One-way ANOVA was used as a statistical test. A p-value of 0.05 was used. b. Comparison of different formulations for PE mRNA. PE mRNAs were made by in vitro transcription. The first combination (RNA V1) tested was using 5’ Cap ARCA and 5-Methoxy-UTP. The second formulation (RNA V2) was made with the 5’ CleanCapAG and N1-Methylpseudo-UTP. Those PE mRNAs were tested in combination with a chemically synthesized epegRNA in HEK293T cells. The editing rate with the PE3 strategy was evaluated by tracking the silent mutation in the codon 4709 in the RYR1 gene. c. Correction of the T4709M mutation in the RYR1 gene by RNA delivery. The percentages of correction were obtained by Sanger sequencing after one Prime editing (PE3) treatment using different delivery methods. Plasmid DNA: PE, epegRNA and nsgRNA were delivered by plasmid DNA. RNA V2: PE mRNA with CleanCap AG and epegRNA and nsgRNA made by IDT. RNA V3: PE mRNA with CleanCapM6 and epegRNA and nsgRNA made by IDT. One-way ANOVA was used as a statistical test. A p-value of 0.001 was used. The percentage of correction of RNA V2 was statistically different from all other conditions. d. Multiple Prime editing treatments to correct the T4709M mutation in the RYR1 gene by RNA delivery. The percentages of correction were obtained by Sanger sequencing after one, two and three treatments of Prime editing using the PE3 strategy by RNA delivery. PE mRNA was made with CleanCap AG (RNA V2), and epegRNA and nsgRNA were chemically synthesized by IDT. One-way ANOVA was used as a statistical test. * represents a p-value <0.001 and ** represents a p-value <0.0001.

Figure 10.

a. Correction by Prime editing of the T4709M mutation in the RYR1 gene in a myoblast line possessing this mutation at the homozygous state by delivering the Prime editing components by plasmid DNA. Experiments were performed in triplicates. The figure illustrates the percentage of correction obtained after one treatment of Prime editing delivered by plasmid DNA. One-way ANOVA was used as a statistical test. A p-value of 0.05 was used. b. Comparison of different formulations for PE mRNA. PE mRNAs were made by in vitro transcription. The first combination (RNA V1) tested was using 5’ Cap ARCA and 5-Methoxy-UTP. The second formulation (RNA V2) was made with the 5’ CleanCapAG and N1-Methylpseudo-UTP. Those PE mRNAs were tested in combination with a chemically synthesized epegRNA in HEK293T cells. The editing rate with the PE3 strategy was evaluated by tracking the silent mutation in the codon 4709 in the RYR1 gene. c. Correction of the T4709M mutation in the RYR1 gene by RNA delivery. The percentages of correction were obtained by Sanger sequencing after one Prime editing (PE3) treatment using different delivery methods. Plasmid DNA: PE, epegRNA and nsgRNA were delivered by plasmid DNA. RNA V2: PE mRNA with CleanCap AG and epegRNA and nsgRNA made by IDT. RNA V3: PE mRNA with CleanCapM6 and epegRNA and nsgRNA made by IDT. One-way ANOVA was used as a statistical test. A p-value of 0.001 was used. The percentage of correction of RNA V2 was statistically different from all other conditions. d. Multiple Prime editing treatments to correct the T4709M mutation in the RYR1 gene by RNA delivery. The percentages of correction were obtained by Sanger sequencing after one, two and three treatments of Prime editing using the PE3 strategy by RNA delivery. PE mRNA was made with CleanCap AG (RNA V2), and epegRNA and nsgRNA were chemically synthesized by IDT. One-way ANOVA was used as a statistical test. * represents a p-value <0.001 and ** represents a p-value <0.0001.

Table 2.

Sequences and characteristics of epegRNAs 1 to 6. The nucleotide C in red is to correct the patient mutation T4709M and the nucleotide T in green is to insert a traceable silent mutation.

Table 2.

Sequences and characteristics of epegRNAs 1 to 6. The nucleotide C in red is to correct the patient mutation T4709M and the nucleotide T in green is to insert a traceable silent mutation.

| epegRNAs |

PBS length (nt) |

RTT length (nt) |

PBS sequence |

RTT sequence |

| 1 |

10 |

12 |

GGACCCAGCC |

AACACTCCGTAA |

| 2 |

10 |

14 |

GGACCCAGCC |

TCAACACTCCGTAA |

| 3 |

10 |

16 |

GGACCCAGCC |

GCTCAACACTCCGTAA |

| 4 |

13 |

12 |

GGACCCAGCCCCC |

AACACTCCGTAA |

| 5 |

13 |

14 |

GGACCCAGCCCCC |

TCAACACTCCGTAA |

| 6 |

13 |

16 |

GGACCCAGCCCCC |

GCTCAACACTCCGTAA |

Table 3.

Sequences and characteristics of epegRNAs 3, 3C. 3D, 3E and 3G. The nucleotide C in red is to correct the patient mutation T4709M and the nucleotide T in green is to insert a traceable silent mutation. Additional silent mutations in blue are included in epegRNAs 3C, 3D, 3E and 3G.

Table 3.

Sequences and characteristics of epegRNAs 3, 3C. 3D, 3E and 3G. The nucleotide C in red is to correct the patient mutation T4709M and the nucleotide T in green is to insert a traceable silent mutation. Additional silent mutations in blue are included in epegRNAs 3C, 3D, 3E and 3G.

| epegRNAs |

PBS length (nt) |

RTT length (nt) |

PBS sequence |

RTT sequence |

| 3 |

10 |

16 |

GGACCCAGCC |

GCTCAACACTCCGTAA |

| 3C |

10 |

16 |

GGACCCAGCC |

GCTCAATACTCCGTGC

|

| 3D |

10 |

16 |

GGACCCAGCC |

GCTCAATACGCCGTGC

|

| 3E |

10 |

16 |

GGACCCAGCC |

GCTCAACACTCCGTGC

|

| 3G |

10 |

16 |

GGACCCAGCC |

GCTCAATACTCCGTGA |