1. Introduction

Leaves are the organs of photosynthesis, and chlorophyll (Chl) is the pigment that gives them a green. Chl does not absorb green light but reflects it [

1]. However, variation in leaf color is a common phenomenon in nature. Some plants have white areas in their leaves, and varieties with albino leaves have been bred for ornamental purpose. Although photosynthesis might be affected, albino leaves have distinct colors and longer ornamental periods, the economic value of ornamental plants.

Several studies have shown that the yellowing or albinism of plant leaves is related to the poor development of chloroplast structure and the obstruction of Chl synthesis [

2] stemming from the direct or indirect effects of genetic mutations [

3,

4]. Leaves with less Chl become light green or lose green color [

1]. In yellow or albino leaves, the expression of Chl biosynthesis genes is down-regulated, and Chl degradation-related enzymes and carotenoid-related genes are highly expressed [

5,

6].

The ability to accurately identify and locate leaf color mutant genes is continually increasing given the continuous improvements in genome, transcriptome, and molecular marker technology [

7]. Proteomics analysis has made significant contributions to our understanding of how plants respond to various environmental changes and has been suggested to be an effective analytical method for determing the relationships between changes in the abundances of proteins and their biological functions [

4].

Primulina serrulata R.B.Zhang & F.Wen is a beautiful gesneriad with high ornamental value because of its rosette leaves and colorful flowers [

8]. Some white-veined (WV) leaves in natural habitat have bright white veins, whereas others have fewer white veins or are almost completely green (

Figure 1A,B). The leaves of seedlings grown in the laboratory also vary in the ratio of white veins (

Figure 1C). Here, we determined the Chl content of leaves and carried out a proteomic experiment to identify the differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) between WV plants and the control and characterize the role of DEPs in WV coloration. Generally, our data provide new insights that could be used to aid the breeding of WV plants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant materials and Chl determination

Leaf blades ca. 2 cm × 2 cm in size from

P. serrulata seedlings grown in the laboratory were divided into two types. One type had bright and distinct white veins, and the other had few white veins (

Figure 1C). Chl

a and Chl

b were determined using spectrophotometry following Zhang, Qu and Li [

9]. Three WV leaves and three control leaves were removed and immediately placed in liquid nitrogen for subsequent proteomic analysis.

2.2. Protein extraction, digestion, and TMT labeling

First, 600 μL of lysis solution was added to each sample and dissociated using ultrasound on ice for 10 min and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min; the supernatant was then collected. Proteins were quantified using the BCA method. Next, 100 μg of protein solution was added to DTT to a final concentration of 10 mM; the solution was then placed in a 55 °C water bath for 1 h, IAA was quickly added to a final concentration of 55 mM, and the solution was left in a dark room for 30 min. Four times the volume of the sample solution of acetone was added and precipitated at –20 °C for at least 3 h. After centrifugation at 4 °C and 20,000 g for 30 min, the sediments were taken out; this step was repeated twice. Finally, 100 μL of 100 mM TEAB solution was added, mixed and rotated.

A total of 1.5 μg of trypsin was added to each sample. Next, 1.0 μg of enzyme was added for each 100 μg of protein substrate, and the samples were then placed in a water bath at 37 °C for 4 h. After centrifugation at 5,000 g to precipitate the solution to the bottom of the EP tube. One sample was selected from each group, and 1 μg of enzyme-dissolved sample was analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) for 1 h.

The peptide solution was cold-dried and then dissolved by 100 μL of 0.1 M TEAB to a concentration of 1 μg/μL. TMT-labeling reagent was balanced to room temperature, and 41 μL of isopropanol was added, followed by vortexing for 1 min and centrifugation to the tube bottom. Labeling reagents were added to the peptide solution and labeled by different isotopes. The peptides were fully mixed with the labeling reagents, centrifuged to the tube bottom, and left at room temperature for 1 h. Next, 5% hydroxylamine was added to terminate the reactions for 15 min. Five μg of materials from each sample was mixed to test the labeling efficiency. The labeled samples were mixed with one sample and transferred to a new EP tube. The samples were labeled and cold-dried.

2.3. High pH phase separation

The mixed labeled peptides were desaulted using 0.1% TFA in 0.5% and 60% acetonitrile solution. The labeled peptides were separated using high pH and reversed-phase LC. The pH was 10.0; 10 mM ammonium formate was used for fluid phase A, and 10 mM ammonium formate and 90% acetonitrile were used for fluid phase B. The labeled peptides were separated using an H-Class LC system (Waters Corporation, USA): the sample volume was 50 μL, the flow velocity was 250 μL/min, and samples were tested at 215 nm. Starting at the second minute, one tube of the distillation fraction was collected for each minute. The distillation fractions were merged into 6 shares according to the chromatographic peak pattern.

2.4. MS analysis

The data-dependent mode was used with automatic switching between MS and MS/MS. A primary scan carried out using whole-scanning MS by Orbitrap ranged from m/z 350 to 1550 and the resolution was set to 120,000 (m/z 200). The maximum ion introducing time was 50 ms, and the automatic gain control was 4e5 ions. The parent ions for MS/MS were fragmented using 38% higher energy C-trap dissociation and scanned by Orbitrap at 15,000 resolution. The lowest ion intensity for MS/MS was set at 50,000. The maximum ion introducing time was 22 ms for MS/MS, the automatic gain control was 5e4 ions, and the selecting window for the parent ion was set to 1.6 Da. Ions with 2–7 electric charges were collected. Dynamic exclusion (30 S) was set after one MS/MS scan to avoid collecting the same parent ions.

2.5. Protein identification and quantification

The total ion flow chromatogram of the MS signal was derived from MS scanning; the abscissa was the elution time, and the ordinate was the peak intensity. The MS data were input into Proteome Discoverer software (version 2.4, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for sieving. The embedded Sequest program was used to analyze the results of the sieved spectrogram. The protein quantification value was determined based the signal value from the extracted TMT-reported ions; the peptide quantification value was indicated by the median, and the protein quantification value was indicated by the accumulation value of the peptide quantification value.

2.6. Bioinformatics analysis

The original RAN-seq transcripts (no. SRR1184436) of closely related species (P. fimbrisepala) were downloaded from the SRA database. The sequences were assembled to construct predicted transcriptional sequences and translated to form reference protein pool for the species in this experiment. The sequencing quality was assessed by FastQC software, and the Trimmomatic software package was used to filter low-quality sequences and putative chimeras. The high-quality sequences were assembled to obtain the transcripts using Trinity (version 2.10.0). The coding proteins were predetermined for the obtained transcript sequences using TransDecoder (version 5.5.0).

To reduce the false positive rate, the search results were further filtered using Proteome Discoverer 2.4. Peptide spectrum matches with reliability greater than 99% and proteins that contained at least one unique peptide were considered credible. Only credible proteins and peptide spectrum matches were retained and verified by the false discovery rate (FDR). Peptides and proteins with an FDR greater than 1% were removed.

3. Results

3.1. Chl contents in WV plants and the control

The Chl content (a + b; mg g-1) were significantly lower (P < 0.001) in the WV group (0.64 ± 0.16) than in the control group (1.40 ± 0.12), suggesting that Chl synthesis was reduced in WV leaves compared with the control group.

3.2. Functional analysis of total proteins

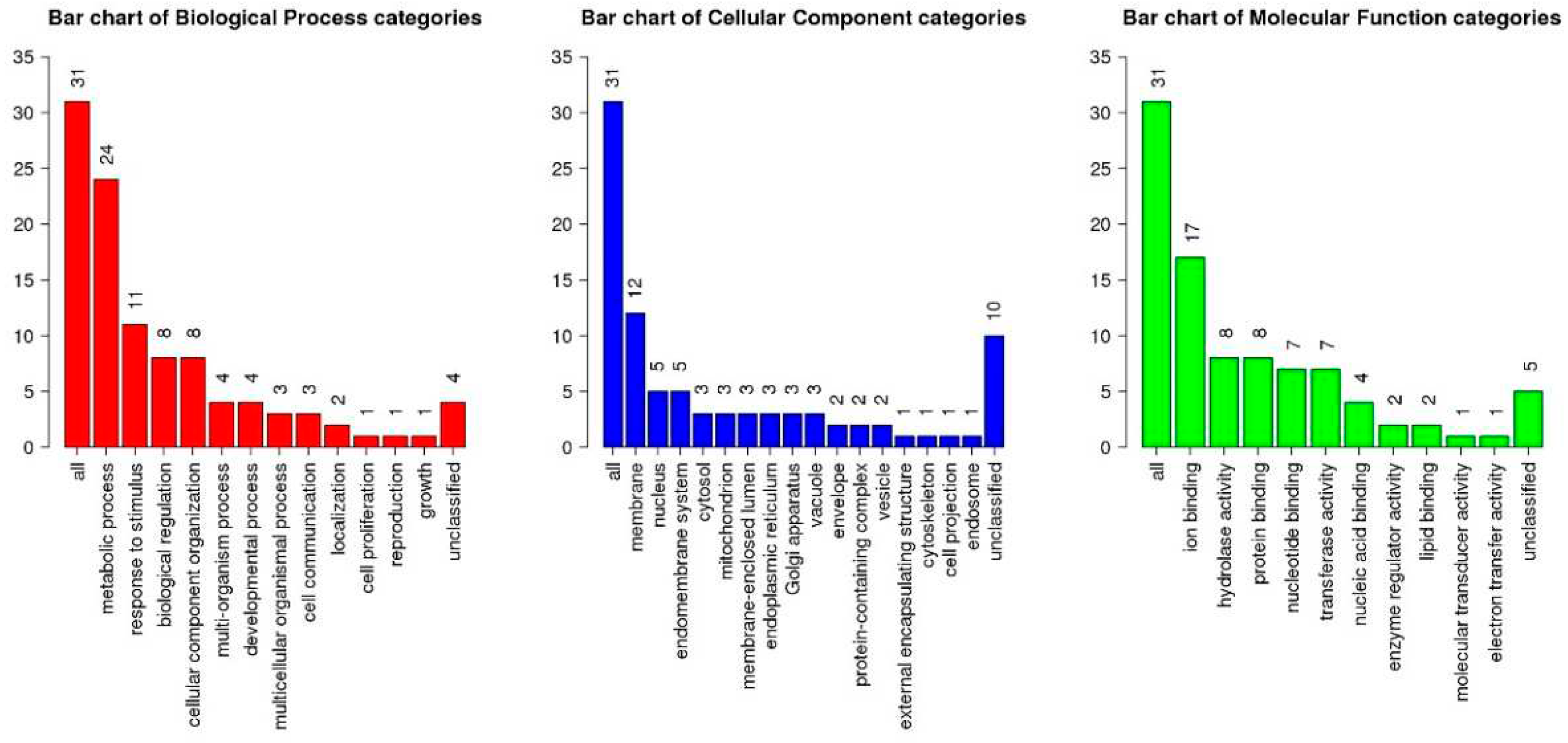

Our proteomics analysis successfully identified a total of 6,261 proteins.

Figure 2, illustrating the results through Gene Ontology (GO) database annotation, highlights that the leaf proteins of

P. serrulata are primarily associated with diverse biological processes (BP). These processes encompass metabolic activities, responses to stimuli, biological regulation, cellular component organization, among others. From a molecular function (MF) perspective, the identified proteins predominantly exhibit activities such as ion binding, hydrolase activity, protein binding, and more. Regarding cellular components (CC), these proteins are chiefly implicated in structures such as the membrane, nucleus, endomembrane system, and so forth.

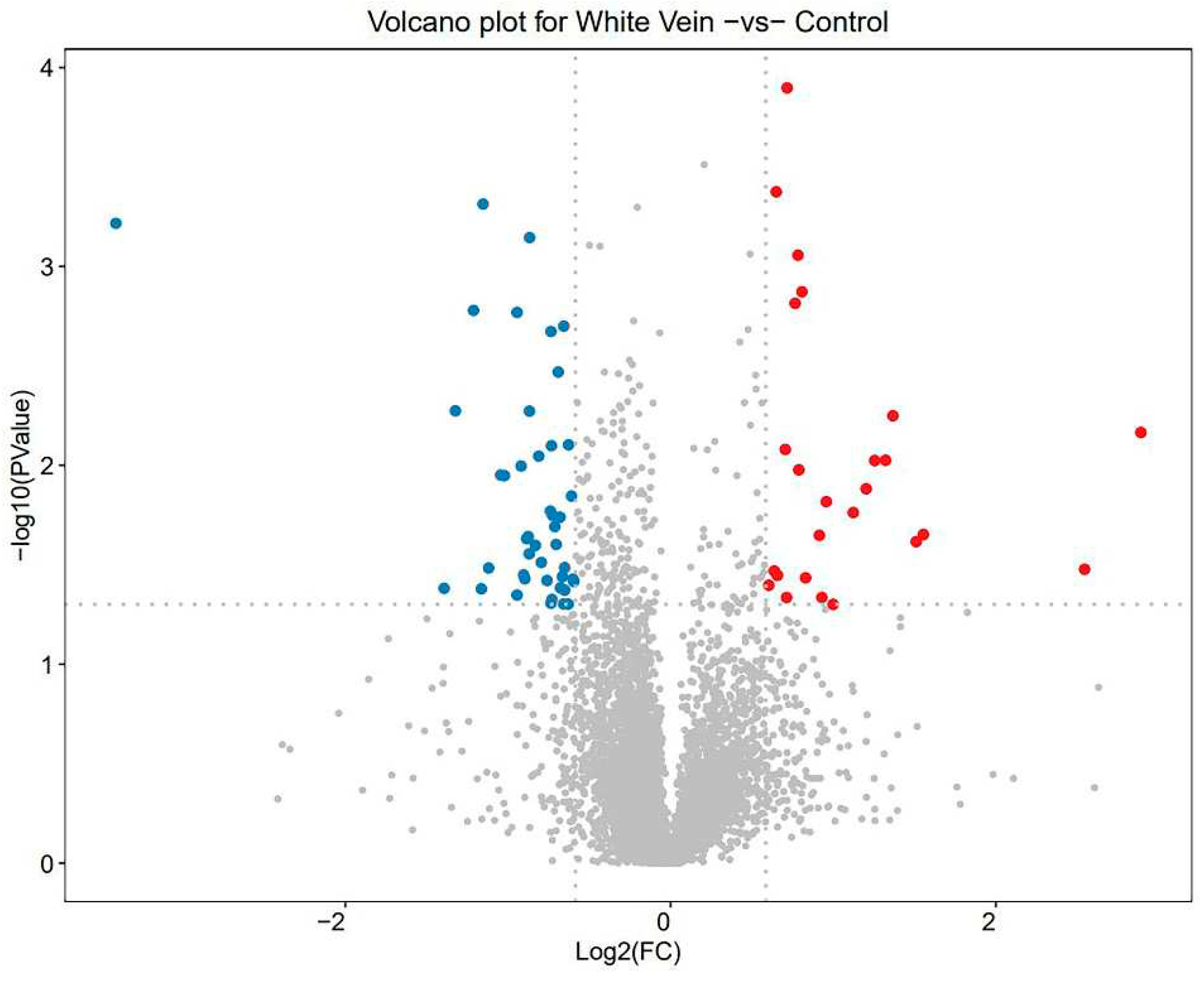

3.3. DEPs quantity

Of the total 6,261 proteins, 69 DEPs were identified, with 44 down-regulated and 25 up-regulated in the WV plants (

Figure 3).

3.4. Functional enrichment analysis of DEPs

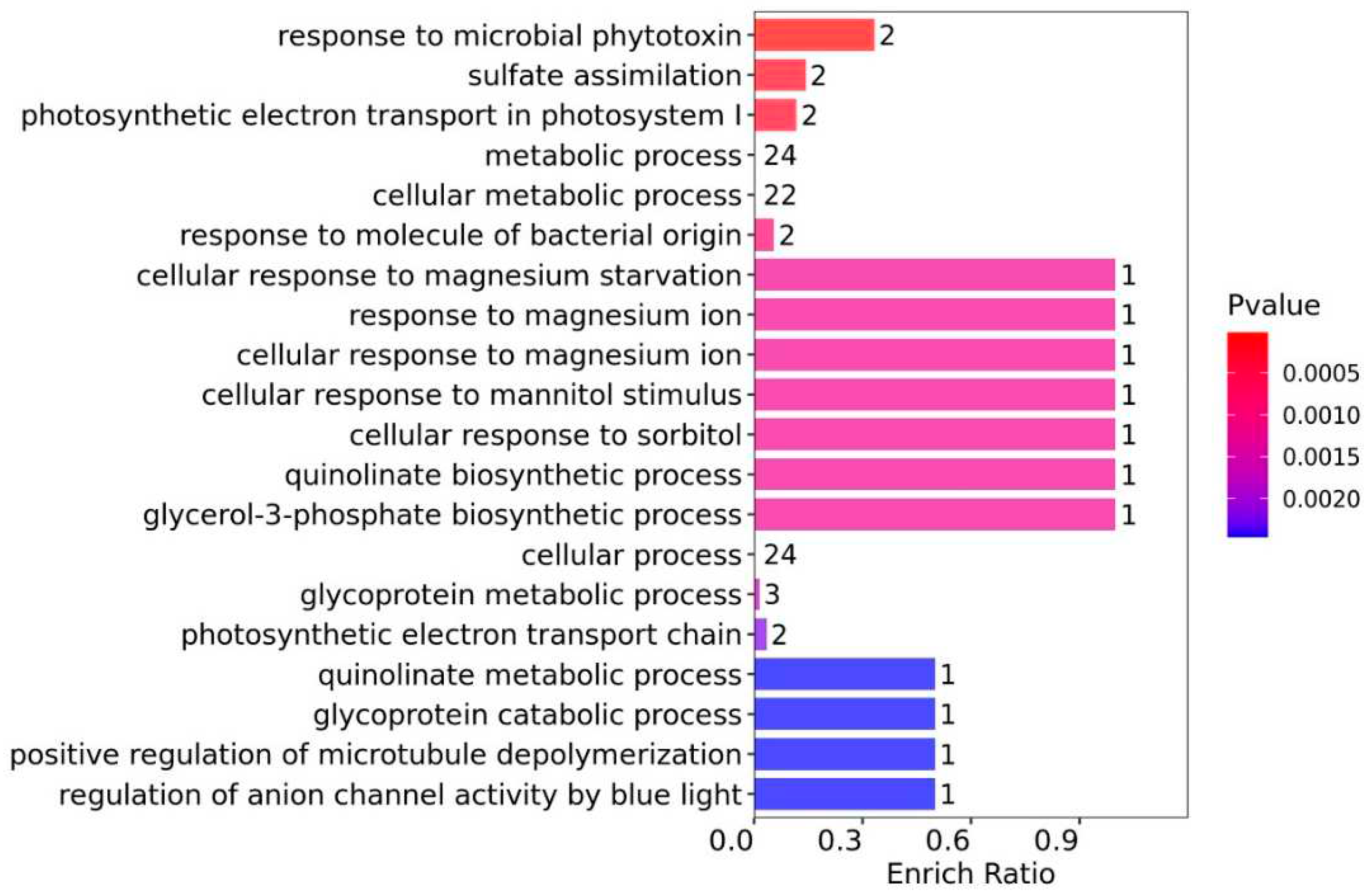

3.4.1. Functional GO enrichment analysis

In the context of the GO-BP enrichment analysis (

Figure 4), the DEPs with the highest enrichment ratios were predominantly associated with magnesium metabolism, despite a medium level of statistical significance. Specifically, these encompassed cellular responses to magnesium starvation (1, with an enriched quantity of DEPs following suit), response to magnesium ion (1), and cellular response to magnesium ion (1). Due to magnesium being an essential element for Chl synthesis, the results of this enrichment analysis align with the decrease in Chl content and the down-regulation of DEPs related to Chl synthesis observed in the WV group in this study.

Other BP DEPs exhibiting notable enrich ratios were linked to cellular responses to mannitol stimulus (1) or sorbitol (1), as well as the biosynthetic processes of quinolinate (1) or glycerol-3-phosphate (1). Despite a relatively low enrich ratio, these DEPs were principally associated with metabolic processes (24), cell metabolic processes (22), and cell processes (24).

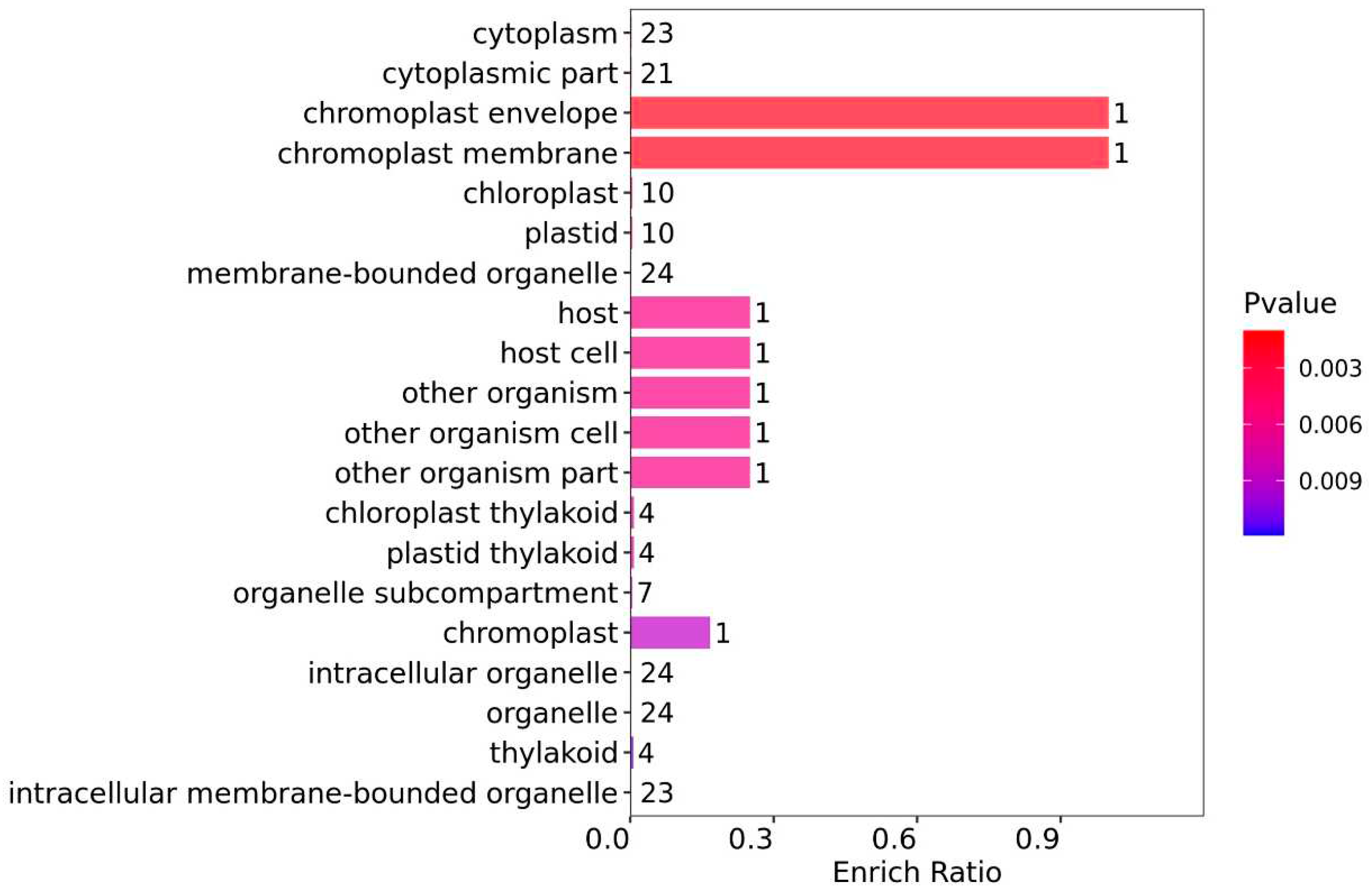

From the GO-CC enrichment analysis (

Figure 5), the DEPs with the highest enrich ratio were associated with chromoplast (chromoplast envelope (1) and chromoplast membrane (1)), and the statistical significance was high. Although the enrich ratio was low, the DEPs were primarily related to cytoplasm, organelle, and chloroplast, including cytoplasm (23), cytoplasmic part (21), chloroplast (10), plastid (10), membrane-bounded organelle (24), intracellular organelle (24), organelle (24), and intracellular membrane-bounded organelle (23). The results of this enrichment analysis align with the down-regulation of DEPs related to chloroplast synthesis observed in the WV group in this study.

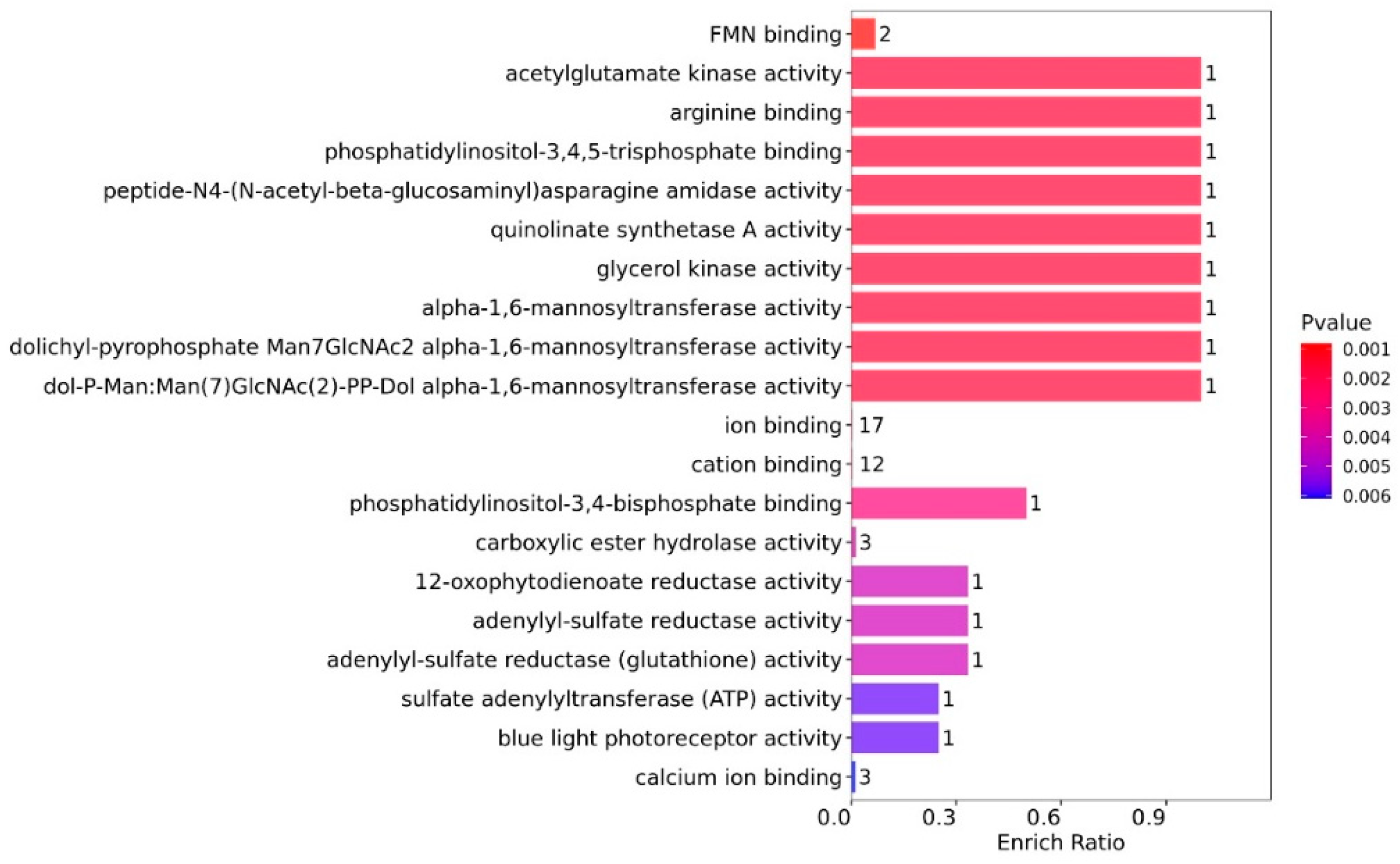

From the GO-MF enrichment analysis (

Figure 6), the DEPs with the highest enrich ratio were primarily involved in material binding (arginine (1) and phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (1)) and enzyme activity (seven enzymes and one DEP for each). Although the enrich ratio was low, the DEPs were mainly related to ion binding (17) and cation binding (12), with three DEPs involved in calcium ion binding.

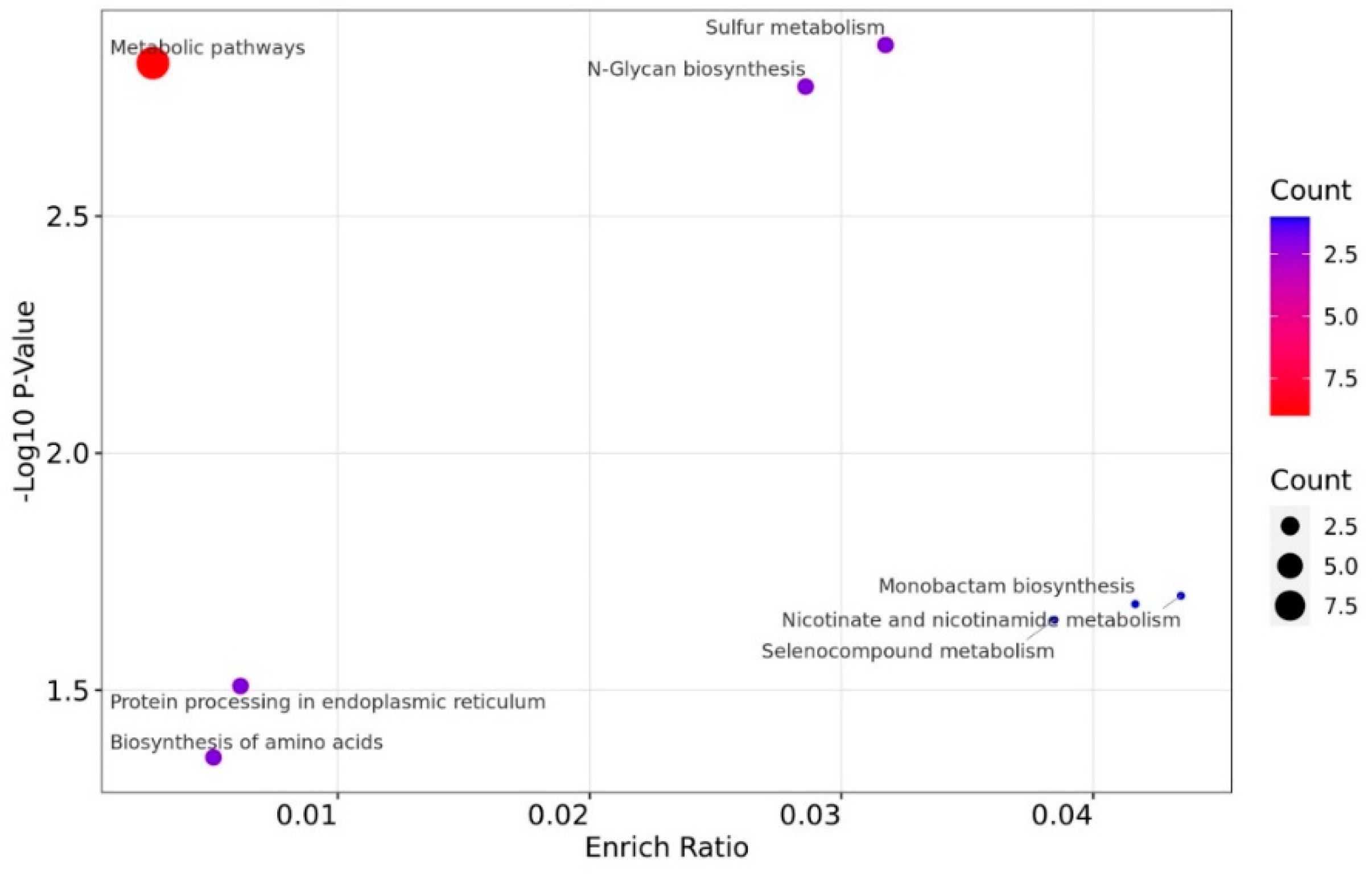

3.4.2. Functional KEGG enrichment analysis

The DEPs were significantly enriched in "Metabolic pathways" (9) in the KEGG enrichment analysis in this study (

Figure 7). Other counts (one or two DEPs) were enriched in nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism, monobactam biosynthesis, selenocompound metabolism, sulfur metabolism, N-Glycan biosynthesis, protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and biosynthesis of amino acids.

3.5. Protein interaction network analysis

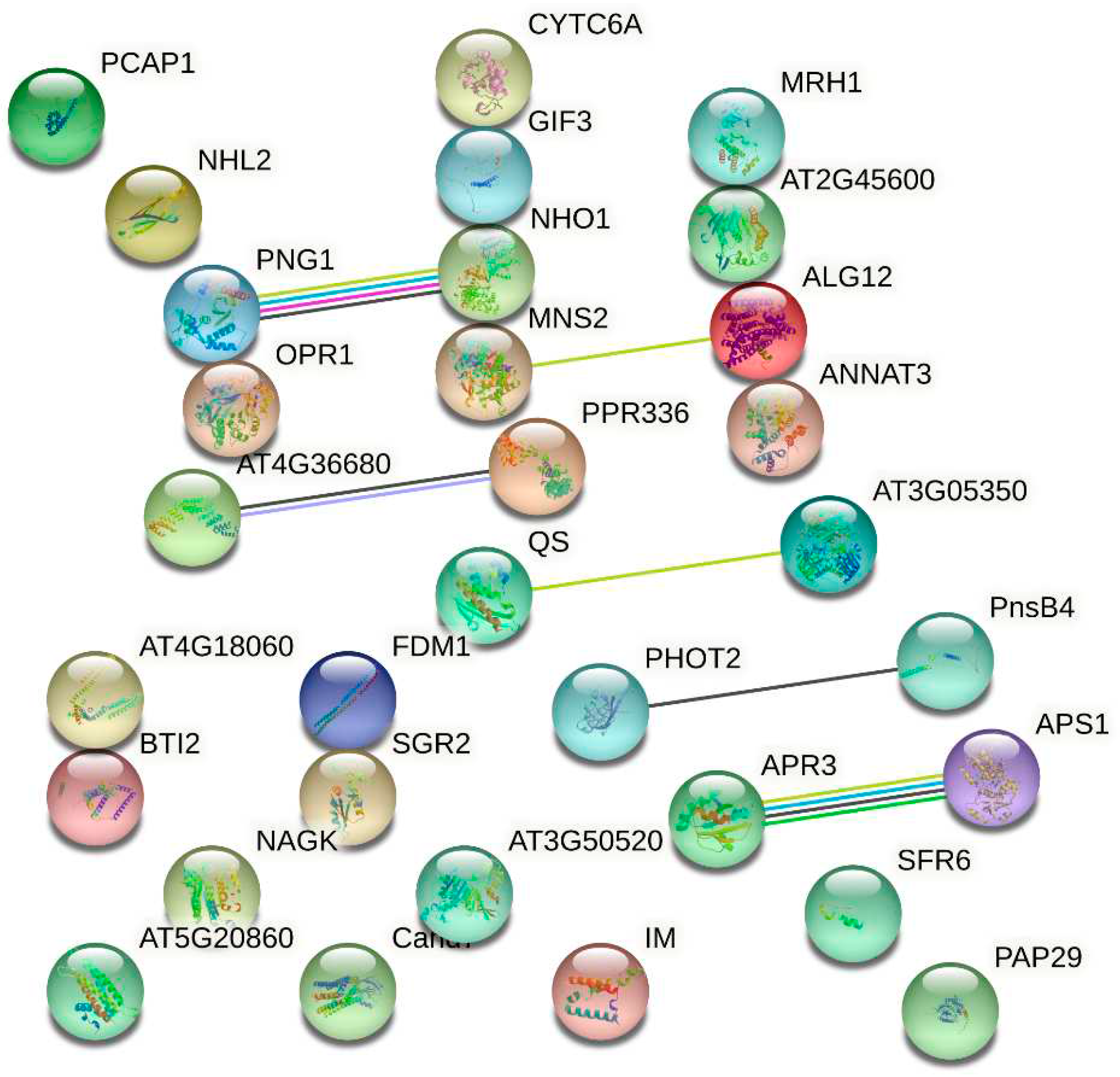

In the DEPs in this study, there are strong correlations (

Figure 8) between phosphoadenosine phosphosulfate reductase (APR3) and adenylyl phosphosulfate (APS1), and between peptide:

N-glycanase (PNG1) and glycerol kinase (NHO1). Obvious interactions also occur in pentatricopeptide repeat-containing (PPR) protein (AT4G36680) and PPR336 (At1g61870), mannosyl-oligosaccharide 1,2-alpha-mannosidase IA (MNS2) and asparagine-linked glycosylation (ALG) protein 12 homolog (ALG12), quinolinate synthase (QS) A and probable phosphoglycerate mutase (PGAM) GpmB (AT3G05350), phototropin (PHOT2) and photosynthetic NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (NDH) subunit of subcomplex B 4 (PnsB4).

4. Discussion

4.1. Proteins affecting formation of chloroplast and Chl

Some down-regulated DEPs in the WV group are associated with the formation of chloroplasts, including reticulon-3, allene oxide synthase (AOS), and cytochrome c6. Reticulons are ER-localized proteins and are ubiquitous in eukaryotic organisms [

10]. Inactivation of the plant reticulon gene leads to severe defects in chloroplast functioning and oxidative stress, resulting in leaves that are pale-green in color [

11]. AOS is targeted to the chloroplast envelope through a pathway that involves ATP and proteins [

12]. Cytochrome c6 is a soluble metalloprotein involved in the reduction of photosystem I [

13].

Some down-regulated DEPs in the WV group are related to Chl biosynthesis, including PHOT2 and guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G-protein) subunit beta. Chl biosynthesis may be controlled by the joint action of phytochromes and PHOTs, which regulate the formation of different chlorophyllide forms [

14]. In addition to GTPase activity, G-proteins exhibit various specific molecular attributes [

15] and are involved in the activation of phytochrome-mediated Chl a/b-binding proteins (cab) gene [

16].

There was an interaction between PHOT2 and PnsB4 in this study (

Figure 8). PHOT is a flavoprotein [

17] and photoreceptor involved in a variety of blue-light-elicited physiological processes including phototropism, chloroplast movement and stomatal opening in plants [

18]. Chloroplast NDH is a different enzyme with a structure similar to that of respiratory NADH dehydrogenase [

19], which is a subunit of PnsB4.

Many down-regulated DEPs related to chloroplast and Chl in the WV group, along with the interaction between PHOT2 and PnsB4 in this study, indicate that the WV cells synthesize fewer chloroplasts and Chl, resulting in the white appearance.

4.2. Proteins related to stress resistance

Some down-regulated DEPs can enhance resistance to environmental stresses, such as drought (late embryogenesis abundant protein [

20] and maspardin [

21]), salt (salt stress root protein RS1 (conjectured from the literal meaning), maspardin [

21] and MNS2 [

22]), heat shock (general stress protein CTC [

23] and retrovirus-related Pol polyprotein from transposon [

24]), oxidation (putative oxidoreductase GLYR1 [

25], SIA1 [

26] and reticulon [

11]), toxin (GPR107 [

27] and cell number regulator [

28]), misfolded glycoprotein (peptide:N-glycanase 1 [

29]), herbivore (AOS [

30]), phytopathogenic fungi (polygalacturonase inhibitor [

31]), and other abiotic and biotic stresses (alcohol dehydrogenase 1 [

32] and beta-glucosidase [

33]). Cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 7 is associated with the variation in the strength of the hypersensitive response [

34].

Fewer DEPs related to stress resistance were up-regulated in the WV group. Acetylglutamate kinase enhances drought tolerance [

35]. Carboxylesteraseisozymes are involved in detoxification or metabolic activation [

36]. Major pollen allergen Bet v 1 is involved in cold tolerance [

37]. In plants, purple acid phosphatase acts as a phosphate (Pi) scavenger, thus mobilizing Pi mostly during growth or under stressed conditions like drought and Pi deprivation [

38]. By capturing toxic metal ions, ferritin is involved in the antioxidant system of defense [

39].

There were sevaral interaction types between PNG1 and NHO1 in this study (

Figure 8). PNG1 may be required for efficient proteasome-mediated degradation of a misfolded glycoprotein [

29] and NHO1 plays a role in general resistance against bacteria and fungi [

40,

41].

In general, the stress resistances in the WV leaves were overall weakened but there are some compensation mechanism against certain stresses.

4.3. Proteins related to biomacromolecule modification

Some down-regulated DEPs in the WV group are related to the biomacromolecule modification. Deficient in DNA methylation 1 protein is an ATPase stimulated by both naked and nucleosomal DNA and it induces nucleosome repositioning on a short DNA fragment [

42]. Retrovirus-related Pol polyprotein from transposon is involved in DNA methylation, which has been reported to contribute to phenotypic plasticity in response to environmental stress in aquatic organisms [

43].

Glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) transamidase is a key enzyme of the posttranslational GPI modification, which generates a carbonyl intermediate, a prerequisite for GPI attachment and many eukaryotic cell surface proteins are anchored to the membrane via GPI [

44]. The polyadenylate-binding protein is an essential protein found in all eukaryotes and is involved in an extensive range of cellular functions, including translation, mRNA metabolism, and mRNA export [

45]. PPR proteins are a large family of modular RNA-binding proteins and facilitate processing, splicing, editing, stability and translation of RNAs [

28].

Many DEPs related to biomacromolecule modification were down-regulated in the WV group, likely attributable to the down-regulation of numerous DEPs involved in photosynthesis and stress resistance within the WV group.

There was an interaction between ALG12 and MNS2 in this study (

Figure 8). ALG is a prevalent protein modification reaction in eukaryotic systems which involves the co-translational transfer of a pre-assembled tetradecasaccharide from a dolichyl-pyrophosphate donor to the asparagine side chain of nascent proteins at the ER membrane [

46]. MNS2 is one of the two functionally redundant mannosidases which are located in Golgi apparatus and MNS1/2-mediated mannose trimming of N-glycans is crucial in modulating glycoprotein abundance to withstand salt stress in plants [

22]. The obvious interaction between ALG12 and MNS2 in this study indicated that the WV formation is related to the protein glycosylation process.

4.4. Proteins related to iron and/or sulfur were increased in WV leaves

Some up-regulated DEPs in the WV group contain iron and/or sulfur, such as QS, APR3, ferritin-1, acid phosphatase, sulfate adenylyl transferase, and prolyl endopeptidase-like protein. Both QS and APR are iron–sulfur enzymes. Most of the cellular iron is stored in ferritin, which is both the acceptor and donor of iron for metabolic processes [

39].

Two up-regulated proteins contain heme, whose porphyrin ring surrounds an iron ion [

47]. The nitrate reductase monomer is composed of a ∼100-kD polypeptide and one each of FAD, heme-iron, and molybdenum-molybdopterin [

48]. A heme-heme binuclear center is in the cytochrome

bd ubiquinol oxidase [

49].

One up-regulated protein can catalyze the reaction related to iron. Acid phosphatase catalyzes hydrolysis of phosphate monoesters in acidic condition and most of isoforms show a characteristic purple color due to charge transfer from tyrosine residue to Fe (III) [

38].

Although iron is an essential element for Chl synthesis [

50], it is likely to be utilized for the synthesis of heme and ferritin in the WV leaves. This inference is supported by the down-regulation of several DEPs involved in Chl synthesis and the up-regulation of several DEPs containing heme or ferritin in this study. Iron-rich ferritins are thought to hinder Chl biosynthesis because of the mutual inhibition between heme and Chl [

7]. Both heme and Chl contain a porphyrin ring structure; in heme, the porphyrin ring surrounds an iron ion, while in Chl, it surrounds a magnesium ion [

47].

Some up-regulated DEPs in the WV group are related to sulfate and respiration. Heme serves as a catalyst for respiration to release the energy stored in organic bonds while Chl serves as a catalyst to convert the energy of sunlight into the stored chemical energy of organic bonds [

51]. Sulfate is taken up by the cell and is activated by sulfate adenylyl transferase to adenylyl phosphosulfate and inorganic pyrophospate [

52]. Prolyl endopeptidase-like is a (thio)esterase involved in mitochondrial respiratory chain function [

53].

Two pairs of proteins related to sulphate or respiration interacted in this study, namely, APR3 and APS1, and QS and AT3G05350 (

Figure 8). APR is the enzyme with the greatest control over the sulphate assimilation pathway, which provides reduced sulphur for the synthesis of the amino acids cysteine and methionine [

54]. APS can be reduced to sulfite and adenosine monophosphate [

52] so it is also related to sulphate assimilation pathway and energy metabolism.

QS is an iron–sulfur enzyme in the biosynthesis of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), playing a crucial role as a cofactor in numerous essential redox biological reactions [

55], such as the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), which is the main energy metabolic pathway in organisms. 2,3-biphophoglycerate-independent PGAM AT3G05350 is a key enzyme in glycolysis that catalyzes the reversible interconversion of 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PGA) to 2-phosphoglycerate (2-PGA) [

56]. Because TCA and glycolysis are both the crucial process in energy metabolism, the obvious interaction between the QS and AT3G05350 in this study indicated that the WV formation is related to energy metabolism.

The up-regulated DEPs containing iron or sulfur in the WV group, along with the interacted proteins related to the sulfate assimilation pathway and energy metabolism in this study, indicate that photosynthesis is weakened, and respiration is enhanced in the WV leaves.

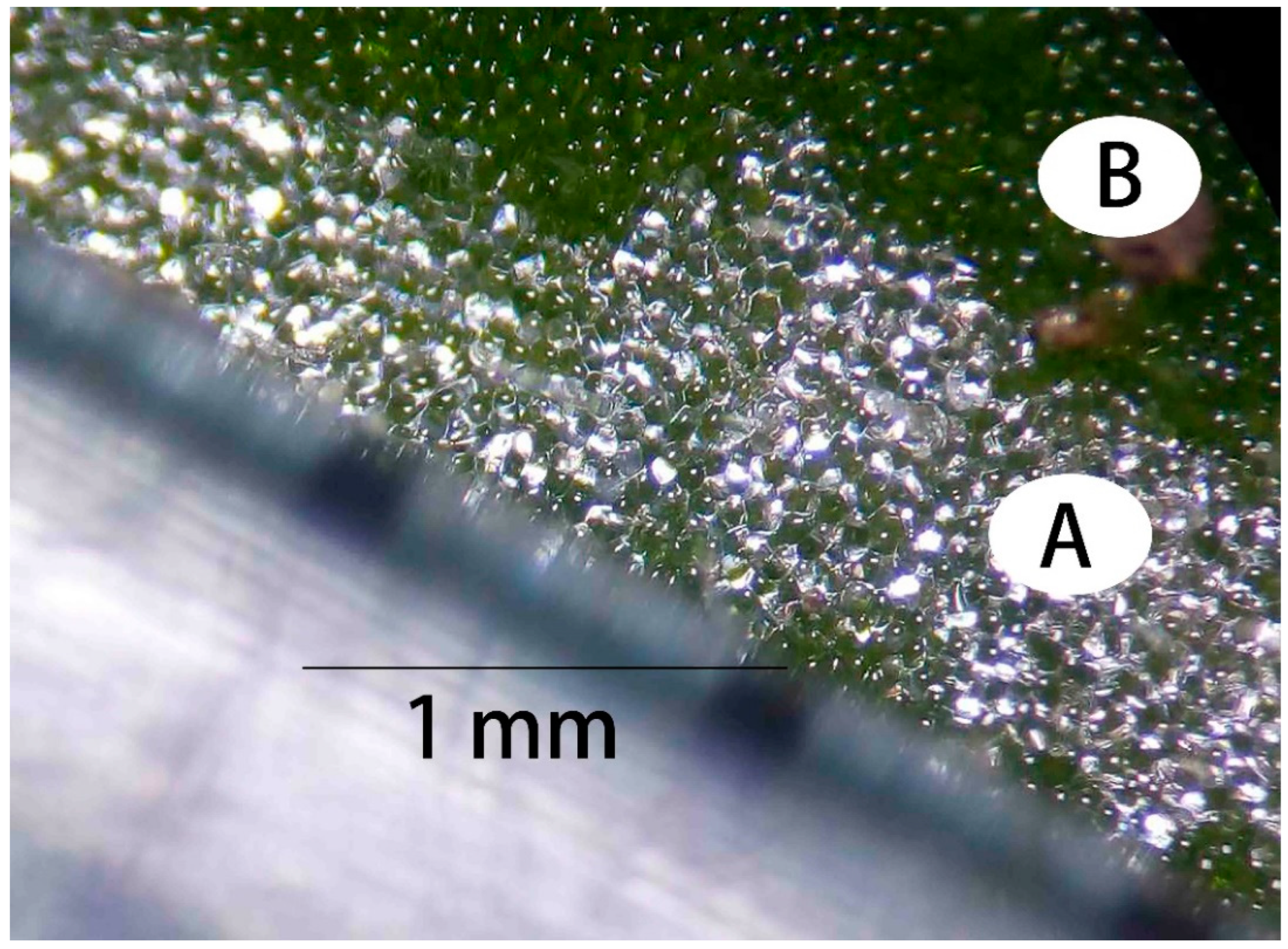

4.5. DEPs affecting cell wall formation

Both expansin-A4 and pectinesterase were up-regulated in the WV group. Expansin-A4 is involved in cell elongation and cell wall modification by loosening and extending plant cell walls [

57]. Pectinesterase acts on pectins in the cell wall in vivo, potentially causing gel formation [

58]. The upregulation of these two DEPs in

P. serrulata suggests ongoing cell wall elongation and gelation within the white veins, aligning with the visual traits of the white veins where cells appear more protrusive and irregular (

Figure 9A) compared to the smoother cells in the green areas (

Figure 9B). The observed differentiation can potentially be ascribed to the extension of cell walls in the white region. Moreover, the enhanced refractivity noted in the white area suggests a greater accumulation of gels within these cellular structures.

5. Conclusions

We conducted a comprehensive proteomic analysis using a TMT-based approach to compare WV plants with green-leaved plants in P. serrulata. The Chl content was significantly lower in the WV group than in the control group. A total of 69 DEPs were identified, with 25 showing up-regulation and 44 displaying down-regulation. Insights derived from the proteome analysis indicate several phenomena within the WV leaves: 1) a reduction in the biosynthesis of chloroplast and Chl; 2) predominant utilization of iron for heme and ferritin synthesis instead of Chl; 3) an increase in respiration; and 4) elongation and gelling of cell walls. Our proteome study suggests that the cultivation of WV leaves can be manipulated by intentionally up-regulating or down-regulating specific proteins.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, Q.-L.D and R.-B.Z.; formal analysis, B.-L.Z and M.-F.C; investigation, D.-J.X. , T.D. and L.H.; software, Z.-M.Q. and S.-S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.-L.D and D.-J.X.; writing—review and editing, R.-B.Z.; funding acquisition, D.-J.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science & Technology Fundamental Resources Investigation Program (Grant No. 2022FY100201).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors [Ren-Bo Zhang], upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Suzhou Bionovogene Company, China, for help with the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- M.Y. Xu, P. He, W. Lai, L.H. Chen, L.L. Ge, S.Q. Liu, Y.J. Yang, Advances in Molecular Mechanism of Plant Leaf Color Variation, Molecular Plant Breeding (2021). https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/46.1068.S.20210112.1619.016.html.

- Chen, L.Y.; He, L.T.; Lai, J.L.; He, S.T.; Wu, Y.X.; Zheng, Y.S. The variation of chlorophyll biosynthesis and the structure in different color leaves of Bambusa multiplex ‘Silverstripe’. Journal of Forest and Environment 2017, 37, 385–391. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.L.; Shi, Y.F.; Wu, J.L. Rice (Oryza sativa L. ) leaf color mutants. Journal of Nuclear Agricultural Sciences 2011, 25, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.M.; Wang, S.; Wang, P.; Gao, L.L.; Yang, R.T.; Li, Y. Label-free comparative proteomic and physiological analysis provides insight into leaf color variation of the golden-yellow leaf mutant of Lagerstroemia indica. Journal of Proteomics 2020, 228, 103942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.Y.; Huang, L.B.; Chen, Q.S.; Lyu, Y.Z.; Sun, H.N.; Liang, Z.H. Physiological and anatomical differences and differentially expressed genes reveal yellow leaf coloration in Shumard Oak. Plants 2020, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.F.; Xu, Y.; Ma, J.Q.; Jin, J.Q.; Huang, D.; Yao, M.; Ma, C.L.; Chen, L. Biochemical and transcriptomic analyses reveal different metabolite biosynthesis profiles among three color and developmental stages in ‘Anji Baicha’(Camellia sinensis). BMC Plant Biology 2016, 16, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.K.; Yuan, S.X.; Hu, F.R. Research Progress on Molecular Mechanisms of the Leaf Color Mutation. Molecular Plant Breeding 2019, 17, 1888–1897. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Deng, T.; Lv, X.-Y.; Zhang, R.-B.; Wen, F. Primulina serrulata (Gesneriaceae), a new species from southeastern Guizhou, China. PhytoKeys 2019, 132, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.L.; Qu, W.J.; Li, X.F. Experimental guidance of plant biology, 4th ed.; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- N.J. Tolley, Functional Analysis of a Reticulon Protein from Arabidopsis thaliana, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Warwick, 2010.

- Tarasenko, V.I.; Garnik, E.Y.; Katyshec, A.I.; Subota, I.Y.; Konstantinov, Y.M. Disruption of Arabidopsis reticulon gene RTNLB16 results in chloroplast dysfunction and oxidative stress. Journal of Stress Physiology & Biochemistry 2012, 8, S21. [Google Scholar]

- Knopf, R.R.; Feder, A.; Mayer, K.; Lin, A.; Rozenberg, M.; Schaller, A.; Adam, Z. Rhomboid proteins in the chloroplast envelope affect the level of allene oxide synthase in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal 2012, 72, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Rosa, M.A.; Navarro, J.A.; Dıaz-Quintana, A.; De la Cerda, B.; Molina-Heredia, F.P.; Balme, A.; del S Murdoch, P.; Dıaz-Moreno, I.; Durán, R.V.; Hervás, M. An evolutionary analysis of the reaction mechanisms of photosystem I reduction by cytochrome c6 and plastocyanin. Bioelectrochemistry 2002, 55, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Zheng, Y. Phototropin is partly involved in blue-light-mediated stem elongation, flower initiation, and leaf expansion: A comparison of phenotypic responses between wild Arabidopsis and its phototropin mutants. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2020, 171, 103967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millner, P.A. Are guanine nucleotide-binding proteins involved in regulation of thylakoid protein kinase activity? FEBS letters 1987, 226, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romerro, L.C.; Lam, E. Guanine nucleotide binding protein involvement in early steps of phytochrome-regulated gene expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1993, 90, 1465–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casal, J.J. Phytochromes, cryptochromes, phototropin: photoreceptor interactions in plants. Photochemistry and Photobiology 2000, 71, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitoku, T.; Nakasone, Y.; Zikihara, K.; Matsuoka, D.; Tokutomi, S.; Terazima, M. Photochemical Intermediates of Arabidopsis Phototropin 2 LOV Domains Associated with Conformational Changes. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 371, 1290–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikanai, T. Chloroplast NDH: a different enzyme with a structure similar to that of respiratory NADH dehydrogenase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics 2016, 1857, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, M.-D.; Hoekstra, F.A.; Hsing, Y.-I.C. Late embryogenesis abundant proteins, Advances in botanical research: Elsevier: 2008; pp. 211–255.

- Wang, F.-B.; Wan, C.-Z.; Niu, H.-F.; Qi, M.-Y.; Gang, L.; Zhang, F.; Hu, L.-B.; Ye, Y.-X.; Wang, Z.-X.; Pei, B.-L. OsMas1, a novel maspardin protein gene, confers tolerance to salt and drought stresses by regulating ABA signaling in rice. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2023, 22, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Niu, G.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Sun, S.; Yu, F.; Lu, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Hong, Z. Trimming of N-glycans by the Golgi-localized α-1, 2-mannosidases, MNS1 and MNS2, is crucial for maintaining RSW2 protein abundance during salt stress in Arabidopsis. Molecular plant 2018, 11, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völker, U.; Engelmann, S.; Maul, B.; Riethdorf, S.; Völker, A.; Schmid, R.; Mach, H.; Hecker, M. Analysis of the induction of general stress proteins of Bacillus subtilis. J Microbiology 1994, 140, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traylor-Knowles, N.; Rose, N.H.; Sheets, E.A.; Palumbi, S.R. Early transcriptional responses during heat stress in the coral Acropora hyacinthus. The Biological Bulletin 2017, 232, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaria, P.; Abbà, S.; Palmano, S. Novel aspects of grapevine response to phytoplasma infection investigated by a proteomic and phospho-proteomic approach with data integration into functional networks. BMC genomics 2013, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manara, A.; DalCorso, G.; Leister, D.; Jahns, P.; Baldan, B.; Furini, A. At SIA 1 AND At OSA 1: two Abc1 proteins involved in oxidative stress responses and iron distribution within chloroplasts. New Phytologist 2014, 201, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tafesse, F.G.; Guimaraes, C.P.; Maruyama, T.; Carette, J.E.; Lory, S.; Brummelkamp, T.R.; Ploegh, H.L. GPR107, a G-protein-coupled Receptor Essential for Intoxication by Pseudomonas aeruginosa Exotoxin A, Localizes to the Golgi and Is Cleaved by Furin*♦. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2014, 289, 24005–24018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, K.; Tian, Y.; Hu, Z.; Chai, T. Wheat cell number regulator CNR10 enhances the tolerance, translocation, and accumulation of heavy metals in plants. Environmental science technology 2018, 53, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Park, H.; Hollingsworth, N.M.; Sternglanz, R.; Lennarz, W.J.J.T.J.O.C.B. PNG1, a yeast gene encoding a highly conserved peptide: N-glycanase. The Journal of cell biology 2000, 149, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, E.E.; Goossens, A. Jasmonates: what ALLENE OXIDE SYNTHASE does for plants. Journal of experimental botany 2019, 70, 3373–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lorenzo, G.; Ferrari, S. Polygalacturonase-inhibiting proteins in defense against phytopathogenic fungi. Current opinion in plant biology 2002, 5, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Liu, W.; Yao, Y.; Wei, Y.; Chan, Z. Alcohol dehydrogenase 1 (ADH1) confers both abiotic and biotic stress resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Science 2017, 262, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 33. Gómez-Anduro, G.; Ceniceros-Ojeda, E.A.; Casados-Vázquez, L.E.; Bencivenni, C.; Sierra-Beltrán, A.; Murillo-Amador, B.; Tiessen, A. Genome-wide analysis of the beta-glucosidase gene family in maize (Zea mays L. var B73). Plant molecular biology 2011, 77, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Kim, S.-B.; Balint-Kurti, P.J.P. A maize cytochrome b–c1 complex subunit protein ZmQCR7 controls variation in the hypersensitive response. Planta 2019, 249, 1477–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Han, G.; Sun, X.; Sheng, Y.; Yan, J.; Scheller, H.V.; Zhang, A. Over-expression of a maize N-acetylglutamate kinase gene (ZmNAGK) improves drought tolerance in tobacco. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 9, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosokawa, M.; Satoh, T. Measurement of carboxylesterase (CES) activities. Current protocols in toxicology 2001, 10, 47.1–47.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Saand, M.A.; Abdelaal, W.B.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Fan, H.; Wang, F. iTRAQ-based comparative proteomic analysis of two coconut varieties reveals aromatic coconut cold-sensitive in response to low temperature. Journal of Proteomics 2020, 20, 103766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, A.; Srivastava, P.K. A molecular description of acid phosphatase. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology 2012, 167, 2174–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielińska-Dawidziak, M. Plant ferritin—a source of iron to prevent its deficiency. Nutrients 2015, 7, 1184–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, T.; Xiao, F.; Tang, X.; Thilmony, R.; He, S.; Zhou, J.-M. Interplay of the Arabidopsis nonhost resistance gene NHO1 with bacterial virulence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2003, 100, 3519–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Tang, X.; Zhou, J.-M. Arabidopsis NHO1 is required for general resistance against Pseudomonas bacteria. The Plant Cell 2001, 13, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeski, J.; Jerzmanowski, A. Deficient in DNA methylation 1 (DDM1) defines a novel family of chromatin-remodeling factors. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, L.; Chen, M.J.G. Genome-wide DNA methylation signatures of sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus during environmental induced aestivation. Genes 2020, 11, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohishi, K.; Inoue, N.; Maeda, Y.; Takeda, J.; Riezman, H.; Kinoshita, T. Gaa1p and gpi8p are components of a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) transamidase that mediates attachment of GPI to proteins. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2000, 11, 1523–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, N.; Mangus, D.A.; Chang, T.-C.; Palermino, J.-M.; Shyu, A.-B.; Gehring, K. Poly (A) nuclease interacts with the C-terminal domain of polyadenylate-binding protein domain from poly (A)-binding protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2007, 282, 25067–25075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weerapana, E.; Imperiali, B. Asparagine-linked protein glycosylation: from eukaryotic to prokaryotic systems. Glycobiology 2006, 16, 91R–101R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberts, B. Molecular biology of the cell. Garland science 2017.

- Campbell, W.H. Nitrate reductase structure, function and regulation: bridging the gap between biochemistry and physiology. Annual review of plant biology 1999, 50, 277–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.J.; Alben, J.O.; Gennis, R.B. Spectroscopic evidence for a heme-heme binuclear center in the cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidase from Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1993, 90, 5863–5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, H., Jr.; Evans, H.; Matrone, G. Investigations of the role of iron in chlorophyll metabolism. II. Effect of iron deficiency on chlorophyll synthesis. Plant Physiology 1963, 38, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granick, S. Evolution of heme and chlorophyll, Evolving genes and proteins; Elsevier, 1965; pp. 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, G.; Zane, G.; Kazakov, A.; Li, X.; Rodionov, D.; Novichkov, P.; Dubchak, I.; Arkin, A.; Wall, J. , Rex (encoded by DVU_0916) in Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough is a repressor of sulfate adenylyl transferase and is regulated by NADH. Journal of bacteriology 2015, 197, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosier, K.; McDevitt, M.T.; Smet, J.; Floyd, B.J.; Verschoore, M.; Marcaida, M.J.; Bingman, C.A.; Lemmens, I.; Peraro, M.D.; Tavernier, J. Prolyl endopeptidase-like is a (thio) esterase involved in mitochondrial respiratory chain function. Iscience 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopriva, S.; Koprivova, A. Plant adenosine 5′-phosphosulphate reductase: the past, the present, and the future. Journal of experimental botany 2004, 55, 1775–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudens, S.O.-D.; Loiseau, L.; Sanakis, Y.; Barras, F.; Fontecave, M. Quinolinate synthetase, an iron–sulfur enzyme in NAD biosynthesis. FEBS letters 2005, 579, 3737–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Assmann, S.M. The glycolytic enzyme, phosphoglycerate mutase, has critical roles in stomatal movement, vegetative growth, and pollen production in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of experimental botany 2011, 62, 5179–5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Li, Q.; Yin, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Gan, S.; Wu, A.-M. Identification of novel miRNAs and their target genes in Eucalyptus grandis. Tree Genetics Genomes 2018, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.-W.; Ben-Arie, R.; Lurie, S. Pectin esterase, polygalacturonase and gel formation in peach pectin fractions. Phytochemistry 2000, 55, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).