1. Introduction

Effectively managing a community’s assets on the blockchain can be transparent, mainly when the community oversees its assets and introduces its token. However, a relationship exists between the community’s assets and the overall value of its issued tokens, and this study provides evidence of such a connection. The study’s findings can potentially enhance decision-making and strategies within the blockchain and cryptocurrency sphere.

Decentralization, transparency, and security are foundational principles in the blockchain domain. The evolution of blockchain technology has led to the creation of decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), empowering communities to decide on their operations collaboratively. A DAO can create its token and form an ecosystem where each token provides voting rights to its holder, excluding its marketplace value. Consequently, this holder impacts the DAO’s decision-making through transparent voting processes, aligning with the fundamental tenets of decentralization in the blockchain.

Decentralized Finance (DeFi) is rooted in traditional financial activities on the blockchain, like lending and trading without intermediaries. With the advent of DeFi 2.0, the field incorporated the idea of a DAO making decisions regarding a project’s liquidity within the protocol. An advancement was implemented by Olympus DAO in 2021, and their paradigm led to the creation of numerous similar projects, where the community of the protocol owned and decided its treasury and its diversification (Spinoglio 2022). Additionally, token holders from the DAO possess voting privileges, which play a pivotal role in shaping the community’s future choices, as observed in the KlimaDAO project (Freni, Ferro, and Moncada 2022). Finally, in DeFi projects, the tokenized assets owned by the protocol are held in the “treasury,” which is in the form of smart contracts, and the use of a treasury’s funds is decided through a voting process (Bhambhwani 2023). The purpose of the treasury in Olympus DAO is to support the DAO’s issued token liquidity (Olympus DAO, n.d.).

The KlimaDAO project, while related to Olympus DAO as a DeFi 2.0 project, is a pioneer in the Regenerative Finance (ReFi) sector (Baim 2023) and is referenced as such by other authors as well (Bordeleau and Casemajor 2023). ReFi is a term connected to DeFi, as they both use the same tools, but ReFi is focused on services linked to regenerative economics (Schletz et al., 2023). KlimaDAO aims to establish a carbon-based cryptocurrency, participating in the voluntary carbon market using Web3 technology. Each KlimaDAO token’s (KLIMA) value is alleged to be backed by one carbon tonne from tokens issued by Moss Earth, Toucan protocol, and C3 protocols, whose tokens are backed by carbon offset credits from carbon registries like Verra and Gold Standard (KlimaDAO 2022). The treasury of KlimaDAO consists of tokens that include carbon offset, such as Base Carbon Tonne (BCT), and non-carbon offset tokens, such as stablecoins.

However, tokenizing carbon credits is a controversial subject that led to the subsequent announcements by Verra in 2021, 2022, and 2023, where it declared no responsibility and involvement for such activities. However, Verra conducted a multi-week public consultation regarding the approach towards the activities associating tokens with instruments issued by Verra along with regulatory-associated concerns. Additionally, (Babel et al. 2022) cite KlimaDAO when focusing on the transparency issues of voluntary carbon offsets.

This study explores whether there is a two-way relationship between the treasuries of Olympus DAO and KlimaDAO and their market capitalization by employing a Granger Causality test. Additionally, we try to find evidence of whether carbon offset tokens can validate the concept of DAO-issued tokens having inherent value through tokenized carbon credits, for which there could be regulatory concerns. Focusing on the example of KlimaDAO, we employ an EGARCH model to address the issues of conditional heteroskedasticity in the time series.

The structure of the study is as follows:

Section 2 details the literature review,

Section 3 the methodology,

Section 4 presents the results,

Section 5 contains the discussion, and Section 6 encapsulates the study’s conclusions.

2. Literature Review

Song et al. (2023), while documenting the mechanism behind Olympus DAO, highlighted the importance of the Olympus DAO token, as well as the treasury mechanism of the project. They explained in detail the staking and bonding mechanisms of the project, which are the main elements of increasing the treasury that supports the DAO’s token. The bonding mechanism allows potential investors to buy the Olympus DAO token at a discount, resulting in the subsequent cash flows being directed to the DAO’s treasury, and the staking mechanism gives an incentive to the DAO token holders to deposit their tokens in the treasury and get interest, in DAO tokens, for their deposit. Subsequently, the treasury assets are used to back the DAO’s token, whose price should not fall under one dollar. When using the treasury funds, the DAO makes such decisions through a voting mechanism with transparent and secure procedures. Chitra et al. (2022) find the role of the treasury to be that of an indirect “insurance fund.” Additionally, the Olympus DAO token is alleged to represent its underlying collateral (Ante et al., 2023).

Jirásek (2023) studied the organizational model of KlimaDAO, inspired by Olympus DAO, and characterized KlimaDAO as a notable example among other DAOs. The author acknowledged KlimaDAO’s commitment to its mission, which led to the acquisition of around 4% of all voluntary carbon market credits by October 2022. Sicilia et al. (2022) also denoted the significance of the KlimaDAO project, exploring the mechanism behind the carbon offset tokens. They acknowledged the complexity of this mechanism and suggested that future works could be focused on assessing the impact of the tokenized carbon offsets in DeFi. In their endeavor to develop a scale for assessing the readiness of blockchain applications for carbon markets, Sipthorpe et al. (2022) categorize KlimaDAO as a “fully competitive” project, the sole DAO project at the highest tier of their scale. Nonetheless, Sipthorpe et al. recognize the market’s immaturity and the challenges associated with these endeavors, mainly due to the lack of pertinent regulations that might deter potential investors from participating in this domain.

Ziegler & Welpe (2022) highlighted the treasury as a crucial attribute of DAOs, while Metelski & Sobieraj (2022) suggested the potential for further investigation into the connection between a DeFi project’s treasury and its valuation, leading to a more precise assessment of a DeFi’s value, taking its treasury assets into account.

Nowak (2022) addressed the issue of carbon credit tokenization and noted its innovative significance for the carbon offset markets; Nowak also cites KlimaDAO and the tokens it creates in this context.

In summary, our literature review did not yield any pertinent studies related to the econometric assessment of either the treasury or the tokenized carbon offsets in the treasury and their potential influence on the market capitalization of a DAO.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Filtering

The Olympus DAO and KlimaDAO treasury data were acquired from Defillama.com (n.d.), and market capitalization data were sourced from Coingecko.com (n.d.). The analyzed period in the data is between October 27, 2021, and September 16, 2023. The data regarding the treasuries of the DAOs are denominated in US dollars.

The Olympus DAO treasury data encompassed tokens in the DAO’s treasury across Ethereum, Polygon, Arbitrum, and Fantom blockchains, along with their corresponding USD values. Similarly, the KlimaDAO treasury consisted of all the tokens under management by the DAO. The formula for the treasury is presented in Equation (1).

In Equation (1), the treasury of a DAO consists of the total sum of the crypto assets (CA) that are included in the respective treasury smart contracts managed by the DAO at time t.

Next, to analyze further the effects of the carbon offset treasury in KlimaDAO, we identify the “KlimaDAO carbon tokens” (KCT). KCT consists of the tokens that KlimaDAO explicitly characterizes as “carbon tokens” (CT) (KlimaDAO 2022), which are BCT, NCT, MCO2, UBO, NBO, and in the KCT we include any liquidity pool token containing these assets, all of which are held in the KlimaDAO treasury, resulting in Equation (2).

In Equation (2), at the time t, the KCT is the sum of every CT.

3.2. Granger Causality Test

In order to make accurate predictions using time series data, it is crucial to determine whether any variables can be used as predictors for one another. Causality plays a critical role in time series analysis, as it measures the extent to which one variable’s values can be used to forecast another variable’s values. By understanding causality, we can gain more insights into future outcomes of a time series based on the values of contiguous time series over time.

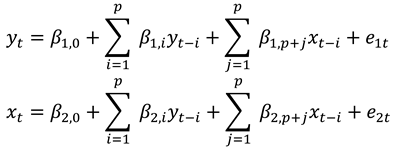

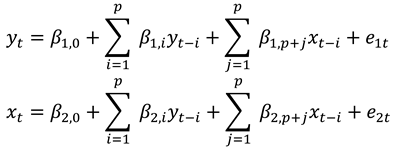

Granger Causality, introduced by Granger in 1969, is a statistical technique that uses Vector Autoregressive Models to determine the direction and strength of causality between two time series. In order to apply this method, the variables must be stationary or cointegrated. A VAR model of order p can be defined as follows in Equation (3):

|

(3) |

For the sake of illustration, we use variables y and x. The order of the Vector Autoregression (VAR) model refers to the number of lags required to validate the hypothesis that each error term is white noise (Shojaie and Fox 2022). We can say that “y Granger causes x” if the past values of y are statistically significant. To examine if x Granger causes y, the testing process needs to be repeated in the opposite direction.

In our analysis, we will investigate whether the returns of OlympusDAO and KlimaDAO market capitalization (MCAP) and their treasuries, Granger-cause each other.

3.3. EGARCH Analysis

Our analysis uses an EGARCH (Nelson 1991) formulation to address its conditional variance. The standard GARCH model (Bollerslev 1986) assumes that negative and positive shocks over time affect variance similarly, an assumption rejected in most cases. EGARCH is an asymmetric GARCH formulation that appropriately addresses positive and negative effects, meaning the much more potent effect of adverse shocks compared to the positive ones on variance. Another advantage of EGARCH is its lack of positive parameter restriction since its exponential derivation bypasses it. Therefore, the conditional mean examined in this study is presented in Equation (4).

where μ is the constant, and

rMCAP and

rKCT are the logarithmic returns of KlimaDAO market cap and

KCT, respectively, to address the issues of stationarity, as the variables are I(1) series according to the ADF and KPSS tests. The EGARCH equation (5) is:

In Equation (5) we define as ln(σ²) the exponent of the variance of the time series, ω as the constant, α as the i parameters for the ARCH effects, γ as the i parameters for the asymmetric effects of the EGARCH derivation and as β the j parameters for the GARCH effects.

The null hypothesis of zero leverage or asymmetry effects on a GARCH model assumes that all γ terms are equal to zero. Asymmetry suggests dissimilar effects on conditional variance when shocks of the same magnitude and opposite sign occur, while leverage implies a negative correlation between the shocks occurring in returns and variance (McAleer and Hafner 2014). The null hypothesis is rejected either when γ < 0 suggesting leverage effects are present in our model or when γ > 0 suggesting asymmetry between the contrasting effects (Chang and McAleer 2017). Since leverage is not possible in an EGARCH model where α and γ are always positive, we may examine only the presence of asymmetry.

Our findings suggest that we may model the conditional variance using an EGARCH model of the first order for the ARCH effects, the second order for the GARCH, and the first order for leverage effects. The EGARCH equation is now transformed as (6):

Finally, we adopt robust standard errors in our estimations to certify the absence of heteroscedasticity in the residuals (White 1982). The EGARCH model was estimated following the methodology of Ghalanos (2022).

3. Results

Table 1 presents the results regarding the stationarity tests and indicates the selection of the final variables to be examined in the subsequent analysis.

In

Table 1 for our analysis, we selected the natural logarithmic values of the examined variables and their respective returns. We observe that in all cases where the variables are in their logarithmic form, the KPSS test for stationarity is rejected when testing for trend stationarity, even if the ADF test null hypothesis for the existence of a unit root is rejected in two cases. Therefore, to ensure that no unit root exists in our time series, we calculate the returns of the variables. In the returns of the variables, we observe that the null hypothesis of a unit root regarding the ADF test is rejected in all cases, and the null hypothesis of trend stationarity regarding the KPSS test is not rejected in all cases. Subsequently, in our analysis, we will use the logarithmic returns of the variables. The descriptive statistics of the examined variables are presented in

Table 2.

Table 2 shows that all variables’ skewness and kurtosis values indicate asymmetry and peakedness in their distributions. Subsequently, the Jarque Bera statistics, with p-values close to zero, reject the null hypothesis of a normal distribution for each variable.

Table 3 shows that the optimal lag length for the VAR model is three since the AIC, BIC, and HQC criteria suggest the same optimal order.

According to the Granger causality tests shown in

Table 4, it is evident that

r_MCAP_OlympusDAO has a significant causal relationship with both

r_MCAP_KlimaDAO and

r_Treasury_OlympusDAO, as the variable Granger causes

r_MCAP_KlimaDAO, just as it does with

r_Treasury_KlimaDAO; This finding implies that

r_MCAP_OlympusDAO can be a valuable tool in predicting future returns of both variables. Additionally, we found that

r_MCAP_KlimaDAO strongly affects the return of its treasury but does not have the same impact on the return of Olympus DAO treasury. This discrepancy highlights the different behavior of the two crypto-assets.

The results of the EGARCH estimation parameters are presented in

Table 5.

The results show that the constant parameters

μ and

ω are not statistically significant, while the external regressor

rKCT is significant at the 1% level, meaning there is a positive relationship between the

rKCT and the conditional mean of the dependent variable. While

alpha1 is insignificant,

beta1 and

beta2 are significant at the 1% level. As a result, the conditional variances of two previous periods have a persisting effect on the present one. The leverage term gamma1 is significant, indicating an inconsistency in terms of positive and negative shock effects, which is on par with Chang and McAleer, who observed the presence of asymmetry in all EGARCH models. Next, in

Table 6, we present the diagnostic test results of the examined model.

In terms of serial correlation, we performed a weighted Ljung-Box Test, suggesting that it is absent from our estimation, where the null hypothesis of the absence of serial correlation in the residuals could not be rejected for any lag length. Additionally, we observe no ARCH effect up to the eighth lag of the residuals.

We proceed to examine the structural changes of the time series over time. Following Nyblom’s methodology (1989), we examine the joint statistic value of the fitted model, where the null hypothesis of the stability of the parameters could not be rejected, resulting in the absence of any structural breaks in the series.

We also test for the presence of leverage effects in the residuals, according to the “Sign Bias Test” of Engle & Ng (1993). The leverage effects are the effect of the residual sign changes in volatility in presence, indicating that the model may be misspecified. The null hypothesis assumes no sign bias, and since their probability is not statistically significant, we do not observe any leverage effects.

4. Discussion

The outcomes of the Granger causality tests, as depicted in the results section, elucidate compelling relationships within our study. The significant causal connection between the returns of Olympus DAO MCAP, the returns of its treasury, and the returns of KlimaDAO MCAP suggests that the Olympus DAO MCAP returns hold predictive value for future returns in these instances.

Furthermore, KlimaDAO’s MCAP returns influence on its treasury highlights the importance of considering individual asset characteristics, which may be helpful when formulating investment strategies or risk management approaches. Additionally, after more carefully examining the KlimaDAO treasury, we saw that the returns of KCT may also affect the KlimaDAO MCAP, showing that a part of the KlimaDAO’s treasury could also support its value.

5. Conclusions

This study explored the interaction between market capitalization and treasuries in two popular DAO projects, Olympus DAO and KlimaDAO. Furthermore, we explored the effect of the returns of KlimaDAO treasury carbon-tokens on KlimaDAO market capitalization returns.

The results could contribute to the predictive modeling toolkit, emphasizing the utility of the returns of Olympus DAO MCAP and shedding light on the distinct behaviors of Olympus DAO and KlimaDAO. These findings enrich our understanding of the intricate dynamics within the crypto-asset domain, offering valuable implications for investors, policymakers, and researchers alike.

Additionally, this research explored the importance of a DAO’s treasury and identified a potential link between the returns from the carbon offset tokens stored in the treasury, which may contribute to the market capitalization of the DAO when employed as collateral for its token, even in the presence of regulatory uncertainties.

This study’s contribution could be a headstart to support whether questionable tokenized assets could be considered to have value. It also provides more evidence that if a token is backed by assets in a DAO treasury, it could support its value, enabling the potential managers of such assets to make better investment decisions. Future studies could focus on further evaluating the significance of the treasury in DeFi projects, emphasizing its role in assessing the overall value of a DeFi project. Finally, there is potential for research to expand into assessing the importance of other tokenized assets in this context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K. and K.P.; methodology, I.K. and K.P.; software, I.K. and K.P.; validation, I.K. and K.P.; formal analysis, I.K. and K.P.; investigation, I.K. and K.P.; resources, I.K. and K.P.; data curation, I.K. and K.P.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K. and K.P.; writing—review and editing, I.K. and K.P.; supervision, I.K. and K.P.; project administration, I.K. and K.P.; funding acquisition, I.K. and K.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding .

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data was collected from Defillama.com and Coingecko.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ante, Lennart, Ingo Fiedler, Jan Marius Willruth, and Fred Steinmetz. 2023. “A Systematic Literature Review of Empirical Research on Stablecoins.” FinTech 2 (1): 34–47. [CrossRef]

- Babel, Matthias, Vincent Gramlich, Marc-Fabian Körner, Johannes Sedlmeir, Jens Strüker, and Till Zwede. 2022. “Enabling End-to-End Digital Carbon Emission Tracing with Shielded NFTs.” Energy Informatics 5 (1): 27. [CrossRef]

- Baim, Owen. 2023. “Curbing Climate Change: An Analysis of the Blockchain’s Impact on the Voluntary Carbon Market,” April. [CrossRef]

- Bhambhwani, Siddharth. 2023. “Governing Decentralized Finance (DeFi).” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY. [CrossRef]

- Bollerslev, Tim. 1986. “Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity.” Journal of Econometrics 31 (3): 307–27. [CrossRef]

- Bordeleau, Erik, and Nathalie Casemajor. 2023. “Cosmo-Financial Imaginaries: BeeDAO as Infrastructural Art Prototype for Planetary Regeneration.” SocArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Chia-Lin, and Michael McAleer. 2017. “The Correct Regularity Condition and Interpretation of Asymmetry in EGARCH.” Economics Letters 161 (December): 52–55. [CrossRef]

- Chitra, Tarun, Kshitij Kulkarni, Guillermo Angeris, Alex Evans, and Victor Xu. 2022. “DeFi Liquidity Management via Optimal Control: Ohm as a Case Study”.

- “Cryptocurrency Prices, Charts, and Crypto Market Cap.” n.d. CoinGecko. Accessed , 2023. https://www.coingecko.com/.

- DefiLlama. n.d. “DefiLlama - DeFi Dashboard.” Accessed October 23, 2023. https://defillama.com/.

- Engle, Robert F., and Victor K. Ng. 1993. “Measuring and Testing the Impact of News on Volatility.” The Journal of Finance 48 (5): 1749–78. [CrossRef]

- Freni, Pierluigi, Enrico Ferro, and Roberto Moncada. 2022. “Tokenomics and Blockchain Tokens: A Design-Oriented Morphological Framework.” Blockchain: Research and Applications 3 (1): 100069. [CrossRef]

- Ghalanos, Alexios. 2022. Rugarch: Univariate GARCH Models. R package version 1.4-9.

- Granger, C. W. J. 1969. “Investigating Causal Relations by Econometric Models and Cross-Spectral Methods.” Econometrica 37 (3): 424–38. [CrossRef]

- Jirásek, Michal. 2023. “Klima DAO: A Crypto Answer to Carbon Markets.” Journal of Organization Design, June. [CrossRef]

- KlimaDAO. 2022. “The KLIMA Token’s Role in the Digital Carbon Market.” KlimaDAO. August 8, 2022. https://www.klimadao.finance/blog/what-is-KLIMA-tokens-role-in-onchain-carbon-market.

- McAleer, Michael, and Christian M. Hafner. 2014. “A One Line Derivation of EGARCH.” Econometrics 2 (2): 92–97. [CrossRef]

- Metelski, Dominik, and Janusz Sobieraj. 2022. “Decentralized Finance (DeFi) Projects: A Study of Key Performance Indicators in Terms of DeFi Protocols’ Valuations.” International Journal of Financial Studies 10 (4): 108. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Daniel B. 1991. “Conditional Heteroskedasticity in Asset Returns: A New Approach.” Econometrica 59 (2): 347–70. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, Eric. 2022. “Voluntary Carbon Markets.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4127136.

- Nyblom, Jukka. 1989. “Testing for the Constancy of Parameters over Time.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 84 (405): 223–30. [CrossRef]

- Schletz, Marco, Axel Constant, Angel Hsu, Simon Schillebeeckx, Roman Beck, and Martin Wainstein. 2023. “Blockchain and Regenerative Finance: Charting a Path toward Regeneration.” Frontiers in Blockchain 6. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbloc.2023.1165133.

- Shojaie, Ali, and Emily B. Fox. 2022. “Granger Causality: A Review and Recent Advances.” Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 9 (1): 289–319. [CrossRef]

- Sicilia, Miguel-Angel, Elena García-Barriocanal, Salvador Sánchez-Alonso, Marçal Mora-Cantallops, and Juan-José de Lucio. 2022. “Understanding KlimaDAO Use and Value: Insights from an Empirical Analysis.” In International Conference on Electronic Governance with Emerging Technologies, 227–37. Springer.

- Sipthorpe, Adam, Sabine Brink, Tyler Van Leeuwen, and Iain Staffell. 2022. “Blockchain Solutions for Carbon Markets Are Nearing Maturity.” One Earth 5 (7): 779–91.

- Song, Ahyun, Euiseong Seo, and Heeyoul Kim. 2023. “Analysis of Olympus DAO: A Popular DeFi Model.” In 2023 25th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT), 262–66. [CrossRef]

- Spinoglio, Francesco. 2022. “Redefining Banking Through Defi: A New Proposal for Free Banking Based on Blockchain Technology and DeFi 2.0 Model.” Journal of New Finance 2 (4). [CrossRef]

- “Treasury | Olympus Docs.” n.d. Accessed November 10, 2023. https://docs.olympusdao.finance/main/overview/treasury/.

- Verra. 2022. “Verra Addresses Crypto Instruments and Tokens.” Verra (blog). May 25, 2022. https://verra.org/verra-addresses-crypto-instruments-and-tokens/.

- ———. 2023. “Verra Concludes Consultation on Third-Party Crypto Instruments and Tokens.” Verra (blog). January 17, 2023. https://verra.org/verra-concludes-consultation-on-third-party-crypto-instruments-and-tokens/.

- “Verra Statement on Crypto Market Activities.” 2021. Verra (blog). November 25, 2021. https://verra.org/statement-on-crypto/.

- White, Halbert. 1982. “Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Misspecified Models.” Econometrica 50 (1): 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, Christian, and Isabell M. Welpe. 2022. “A Taxonomy of Decentralized Autonomous Organizations.” In Proceedings of the 43rd International Conference on Information Systems, ICIS 2022, Digitization for the Next Generation, Copenhagen, Denmark, December 9-14, 2022, edited by Niels Bjørn-Andersen, Roman Beck, Stacie Petter, Tina Blegind Jensen, Tilo Böhmann, Kai-Lung Hui, and Viswanath Venkatesh. Association for Information Systems.https://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2022/blockchain/blockchain/1.

Table 1.

Stationarity tests.

Table 1.

Stationarity tests.

| Variable |

ADF |

KPSS |

| Statistic |

p-value |

Statistic |

p-value |

| LN_MCAP_Olympus DAO |

-3.73 |

.00*** |

.64 |

.01*** |

| LN_MCAP_KlimaDAO |

-2.94 |

.04** |

.69 |

.01*** |

| LN_Treasury_Olympus DAO |

-2.61 |

.09* |

.15 |

.04** |

| LN_Treasury_KlimaDAO |

.15 |

.97 |

.39 |

.01*** |

| r_MCAP_Olympus DAO |

-22.43 |

.00*** |

.11 |

.10 |

| r_MCAP_KlimaDAO |

-11.03 |

.00*** |

.12 |

.10 |

| r_Treasury_Olympus DAO |

-12.28 |

.00*** |

.04 |

.10 |

| r_Treasury_KlimaDAO |

-11.55 |

.00*** |

.08 |

.10 |

| LN_KCT |

-2.69 |

.08* |

.68 |

.01*** |

| r_KCT |

-15.56 |

.00*** |

.08 |

.10 |

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the examined variables.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the examined variables.

| Variable |

Statistic |

| Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Range |

Max |

Min |

Median |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

Jarque Bera |

Jarque Bera

p-value |

| r_MCAP_Olympus DAO |

-.004 |

.044 |

.502 |

.162 |

-.340 |

-.001 |

-1.783 |

16.058 |

5267.838 |

.000 |

| r_Treasury_Olympus DAO |

-.002 |

.046 |

1.446 |

.857 |

-.588 |

.000 |

5.709 |

216.226 |

1310879.000 |

.000 |

| r_MCAP_KlimaDAO |

-.007 |

.061 |

.713 |

.267 |

-.447 |

-.004 |

-.945 |

11.079 |

1978.948 |

.000 |

| r_Treasury_KlimaDAO |

-.002 |

.069 |

1.163 |

.568 |

-.595 |

-.173 |

-.079 |

31.315 |

23050.355 |

.000 |

| r_KCT |

-.003 |

.054 |

.680 |

.327 |

-.354 |

-.233 |

-.021 |

13.338 |

3072.755 |

.000 |

Table 3.

VAR lag selection criteria.

Table 3.

VAR lag selection criteria.

| Lags |

Log Likelihood |

p (LR) |

AIC |

BIC |

HQC |

| 1 |

4269.240 |

- |

-12.461 |

-12.328 |

-12.410 |

| 2 |

4363.453 |

.000 |

-12.690 |

-12.452 |

-12.598 |

| 3 |

4449.424 |

.000 |

-12.896* |

-12.551* |

-12.762* |

| 4 |

4453.218 |

.960 |

-12.860 |

-12.409 |

-12.685 |

| 5 |

4465.460 |

.079 |

-12.849 |

-12.292 |

-12.633 |

| 6 |

4474.889 |

.276 |

-12.830 |

-12.166 |

-12.573 |

| 7 |

4492.579 |

.004 |

-12.835 |

-12.065 |

-12.537 |

| 8 |

4498.715 |

.725 |

-12.806 |

-11.930 |

-12.467 |

Table 4.

Granger causality test results.

Table 4.

Granger causality test results.

| Null hypothesis |

Observations |

F-Statistic |

Probability |

| Variable |

“Does not Granger cause” |

| r_MCAP_Olympus DAO |

r_MCAP_KlimaDAO |

687 |

3.31 |

.02*** |

| r_MCAP_KlimaDAO |

r_MCAP_Olympus DAO |

|

.24 |

.87 |

| r_Treasury_KlimaDAO |

r_MCAP_KlimaDAO |

687 |

.28 |

.84 |

| r_MCAP_KlimaDAO |

r_Treasury_KlimaDAO |

|

19.15 |

.00*** |

| r_Treasury_Olympus DAO |

r_MCAP_KlimaDAO |

687 |

.36 |

.79 |

| r_MCAP_KlimaDAO |

r_Treasury_Olympus DAO |

|

2.03 |

.11 |

| r_Treasury_KlimaDAO |

r_MCAP_Olympus DAO |

687 |

.61 |

.61 |

| r_MCAP_Olympus DAO |

r_Treasury_KlimaDAO |

|

.26 |

.85 |

| r_Treasury_Olympus DAO |

r_MCAP_Olympus DAO |

687 |

1.72 |

.16 |

| r_MCAP_Olympus DAO |

r_Treasury_Olympus DAO |

|

3.82 |

.01*** |

| r_Treasury_Olympus DAO |

r_Treasury_KlimaDAO |

687 |

.06 |

.98 |

| r_Treasury_KlimaDAO |

r_Treasury_Olympus DAO |

|

.26 |

.86 |

Table 5.

EGARCH results.

| Coefficient |

Estimate |

Std. Error |

t value |

p-value |

| μ |

-.002 |

.001 |

-1.607 |

.108 |

| rKCT |

.638 |

.107 |

5.958 |

.000*** |

| ω |

-.071 |

.097 |

-.726 |

.468 |

| alpha1 |

.040 |

.061 |

.664 |

.506 |

| beta1 |

.369 |

.082 |

4.493 |

.000*** |

| beta2 |

.614 |

.086 |

7.175 |

.000*** |

| gamma1 |

.418 |

.103 |

4.081 |

.000*** |

Table 6.

Model diagnostic test statistics.

Table 6.

Model diagnostic test statistics.

| Weighted Ljung-Box Test on Standardized Residuals |

|

|

Weighted Ljung-Box Test on Standardized Squared Residuals |

|

|

Weighted ARCH LM Tests |

| Laga

|

|

|

Lagb

|

|

|

Lag |

| 1 |

2 |

5 |

|

|

1 |

8 |

14 |

|

|

4 |

6 |

8 |

| .843 |

.881 |

2.993 |

|

|

1.182 |

2.063 |

3.148 |

|

|

.383 |

.845 |

1.487 |

| [.359] |

[.538] |

[.408] |

|

|

[.277] |

[.849] |

[.947] |

|

|

[.536] |

[.793] |

[.842] |

| Nyblom stability test |

|

|

|

|

|

Sign Bias Test |

| Joint Statistic |

Joint Statistic Asymptotic Critical Values |

|

|

|

|

|

| 10% |

5% |

1% |

|

|

|

|

|

Sign Bias |

Negative Sign Bias |

Positive Sign Bias |

Joint Effect |

| 1.452 |

1.690 |

1.900 |

2.350 |

|

|

|

|

|

1.864 |

1.675 |

.336 |

4.595 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[.063]* |

[.094]* |

[.737] |

[.204] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).