Submitted:

21 November 2023

Posted:

22 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

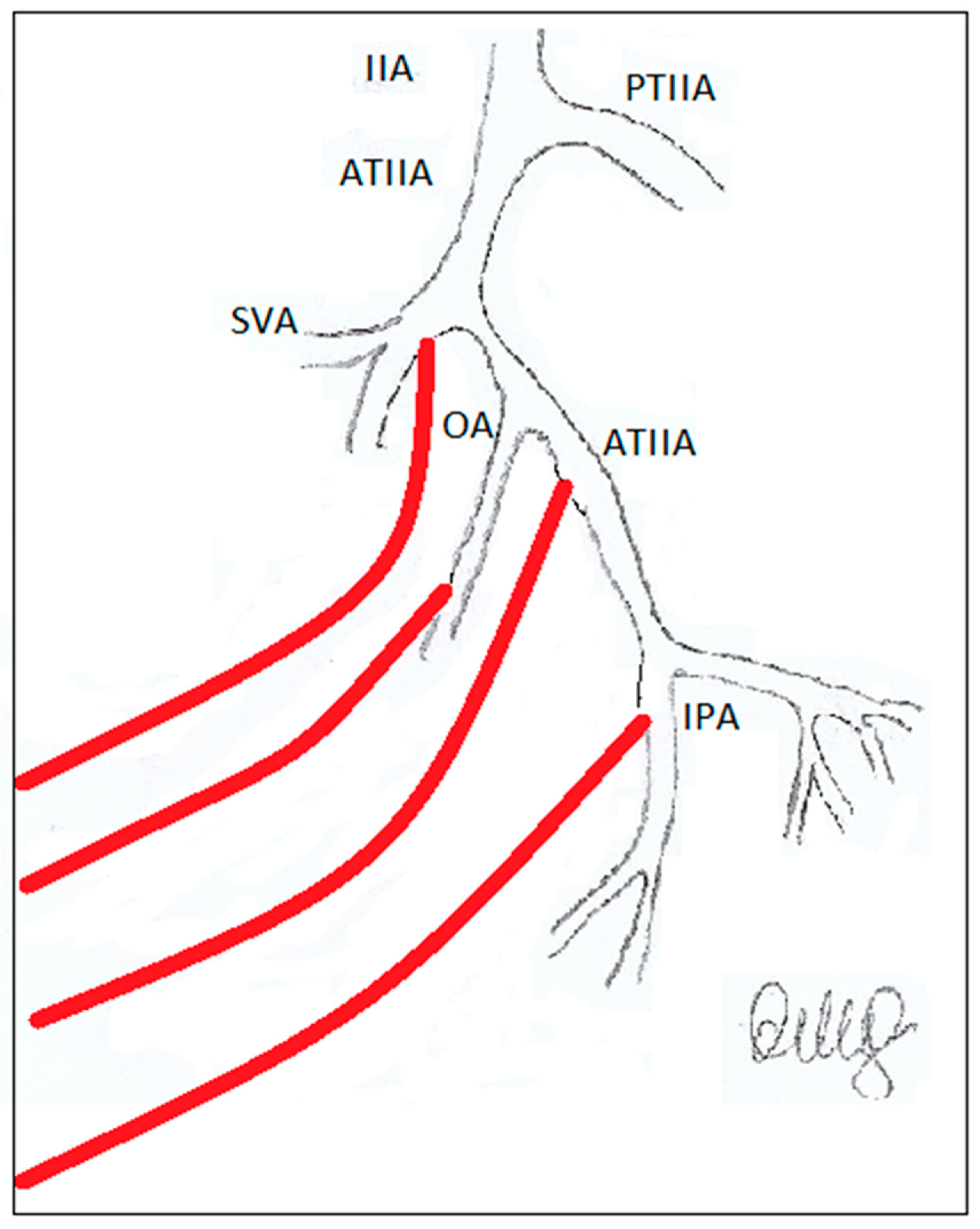

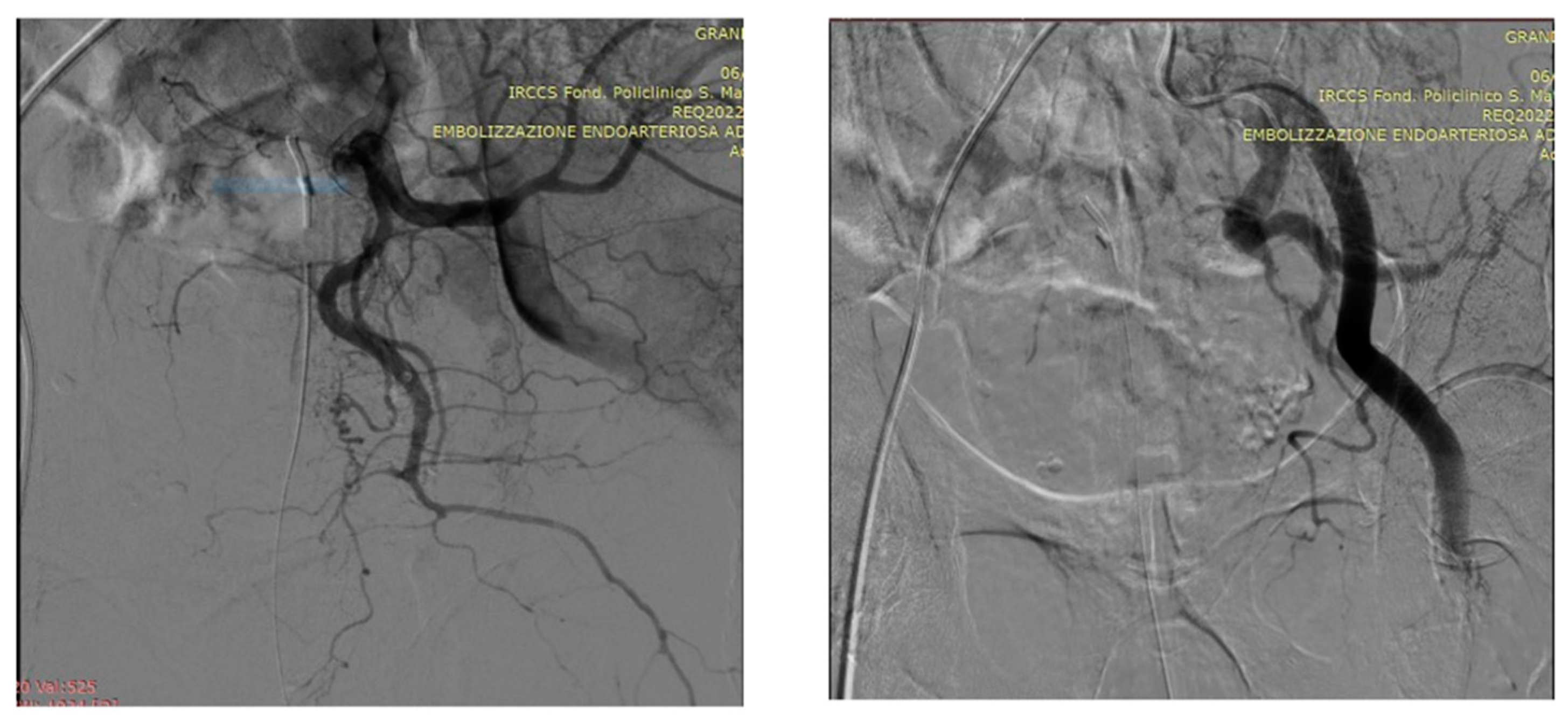

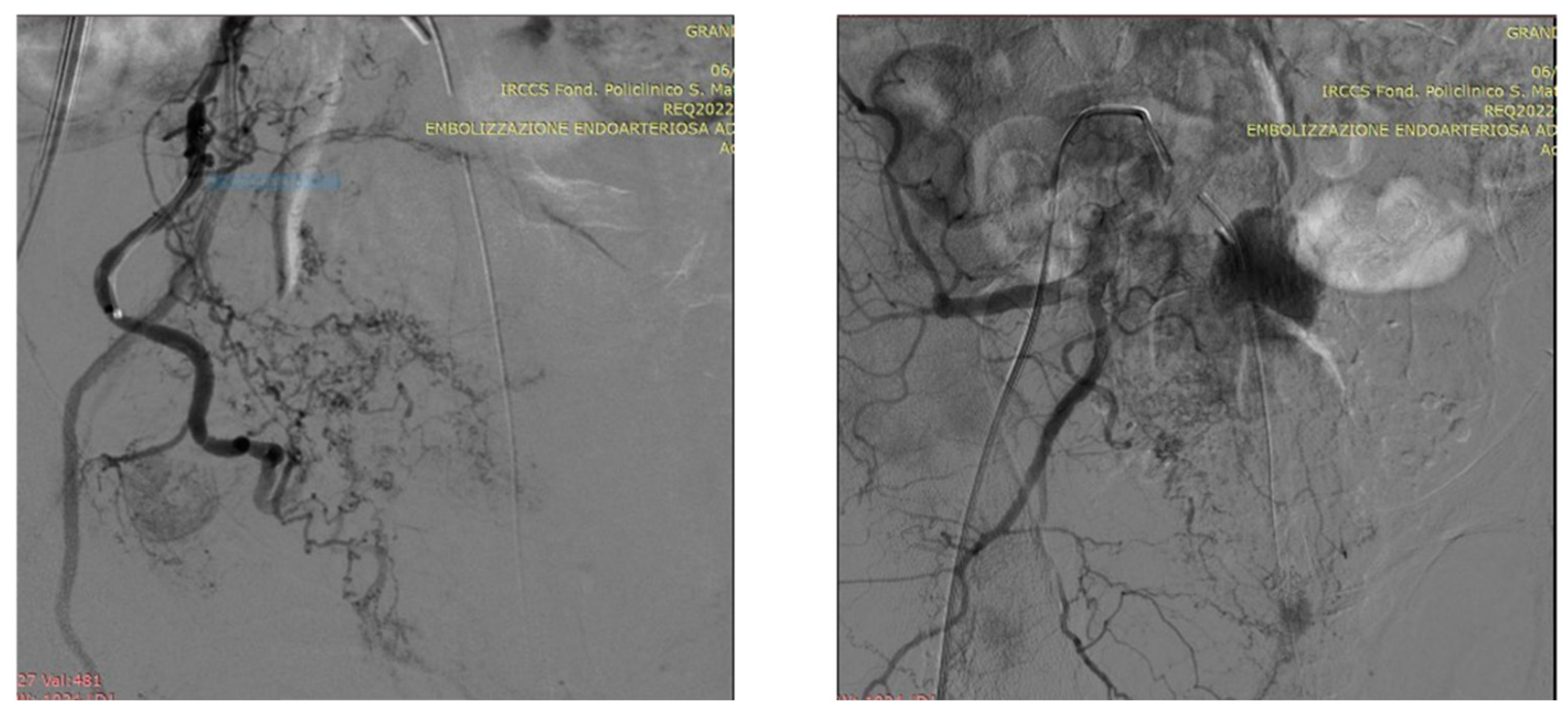

2. PAE and the importance of careful evaluation of the prostate gland’s vascular supply.

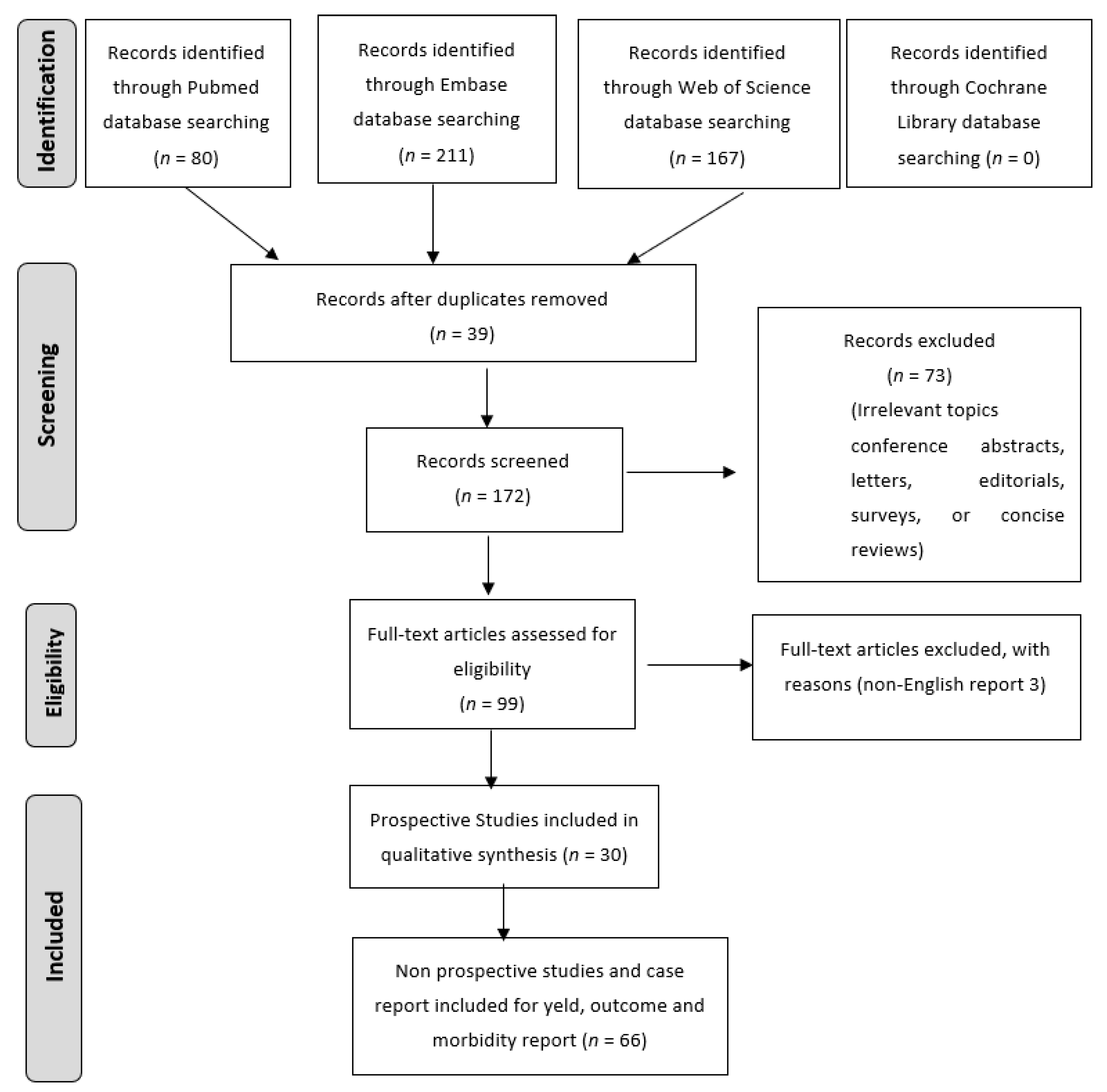

3. Materials and Methods

Research Methodology for Literature Review

4. Results

4.1. Efficacy of PAE

4.2. Yield of PAE

4.3. Morbidity and complications

4.4. Patient selection for PAE

4.5. Long-term Outcomes

4.6. Comparison to Other Treatments

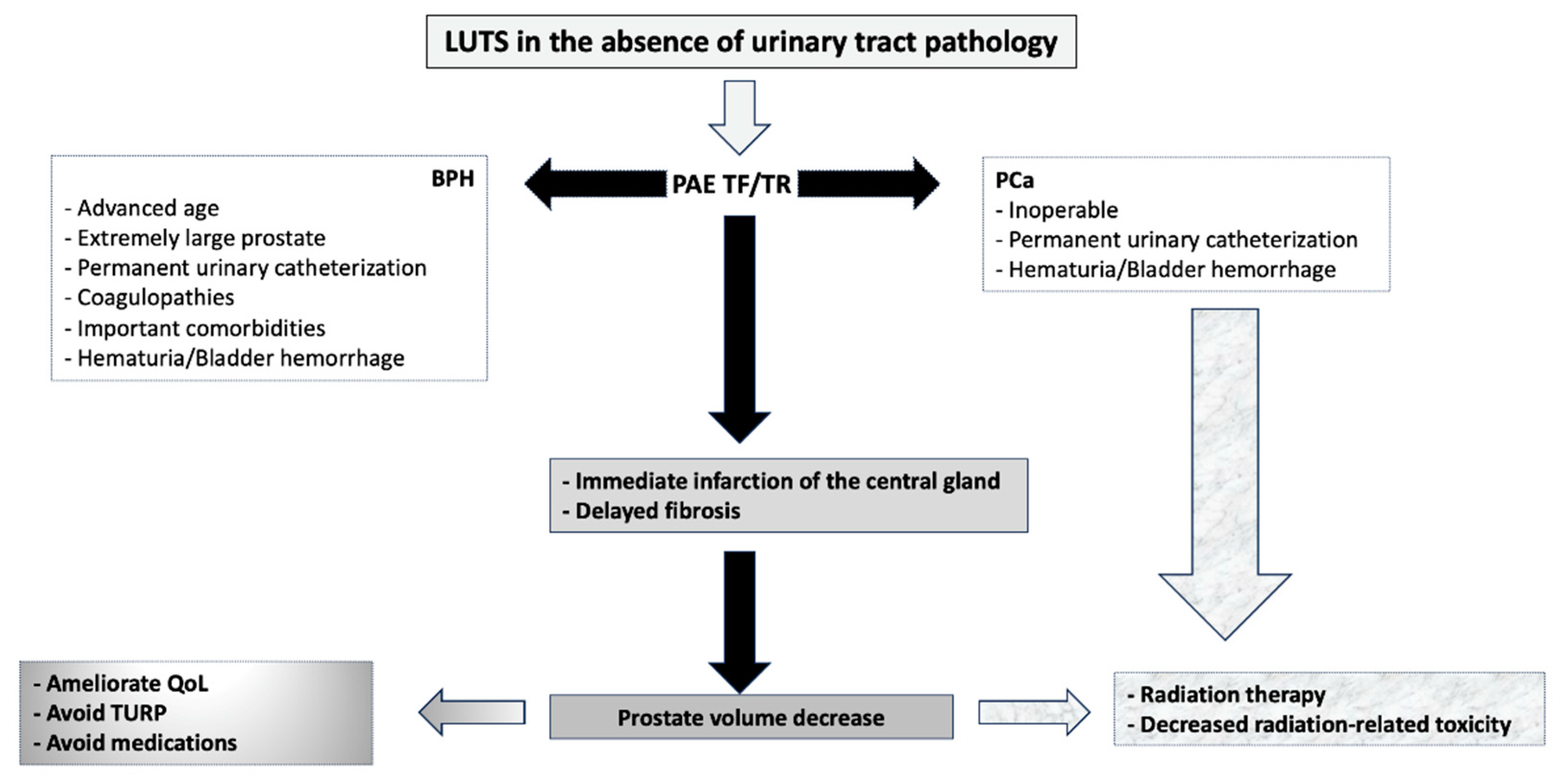

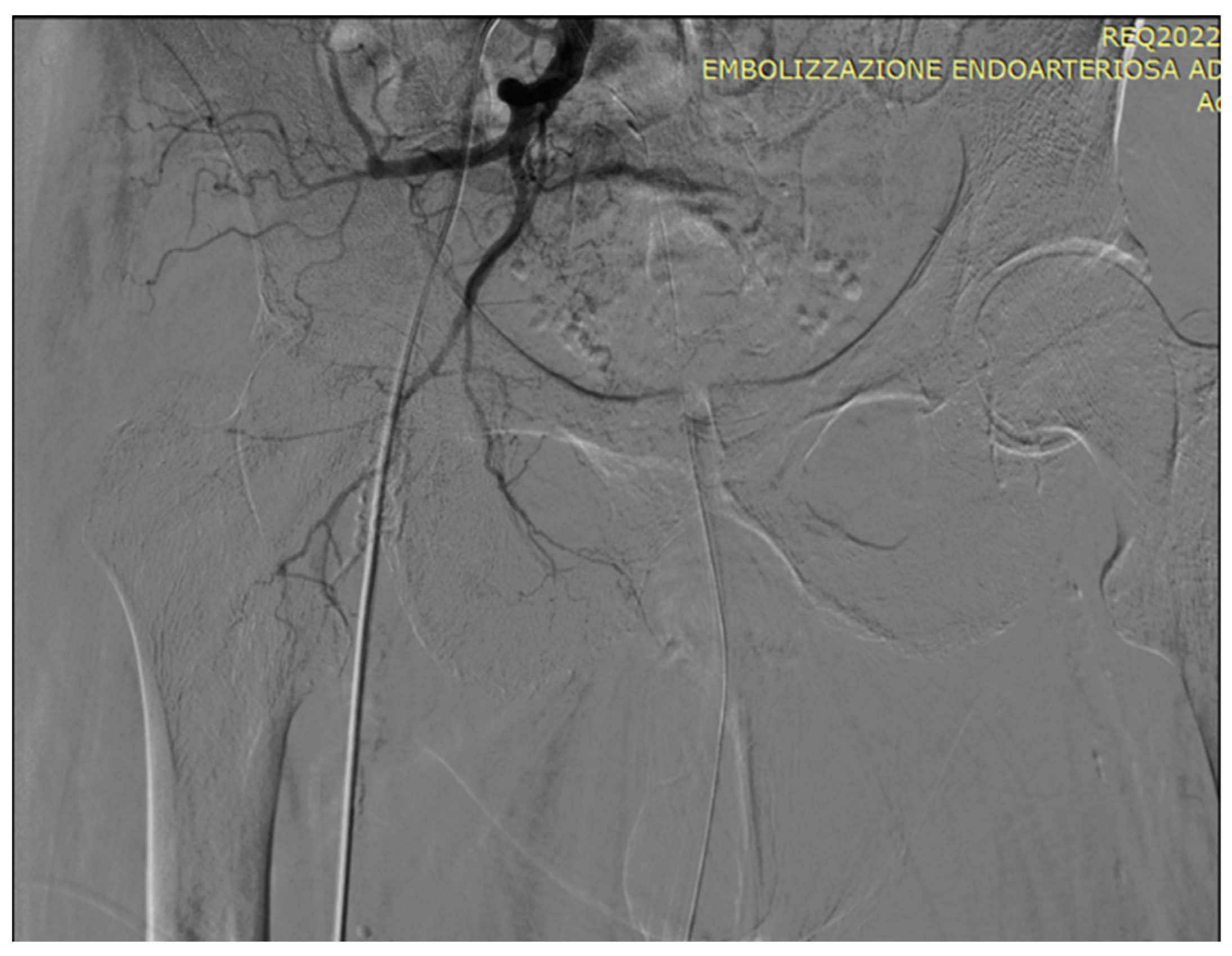

5. A suggested algorithm and a demonstrative patient profile

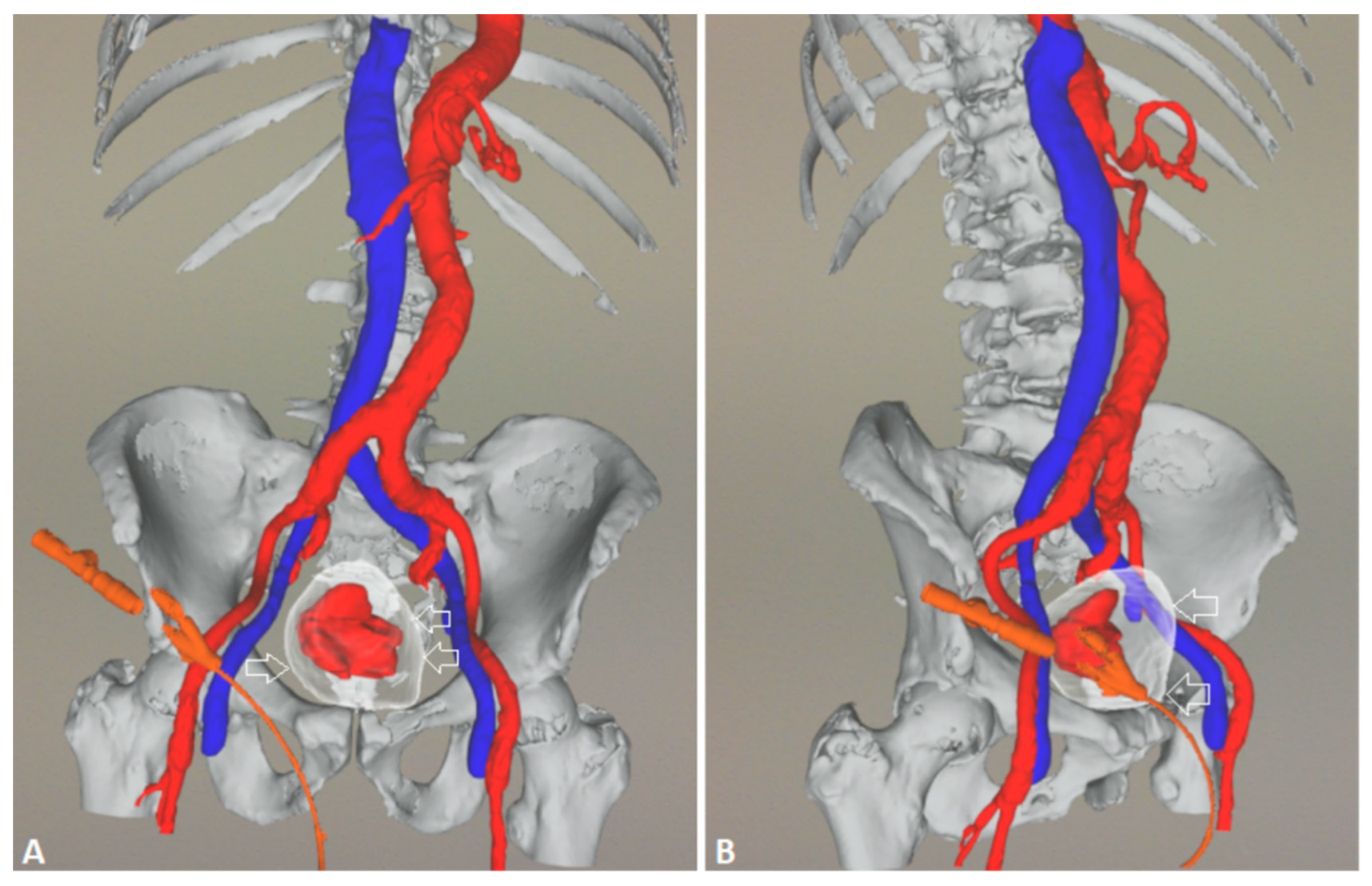

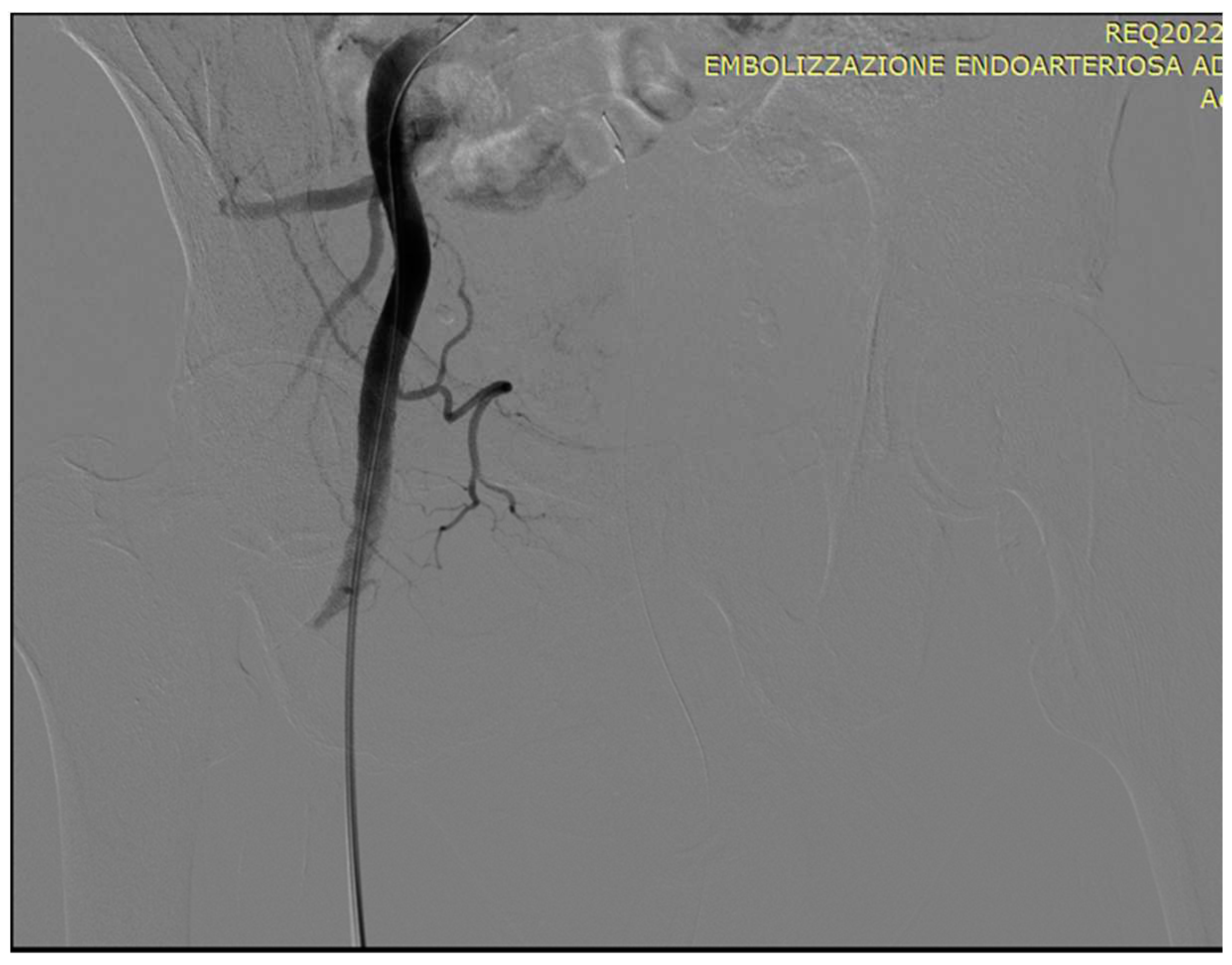

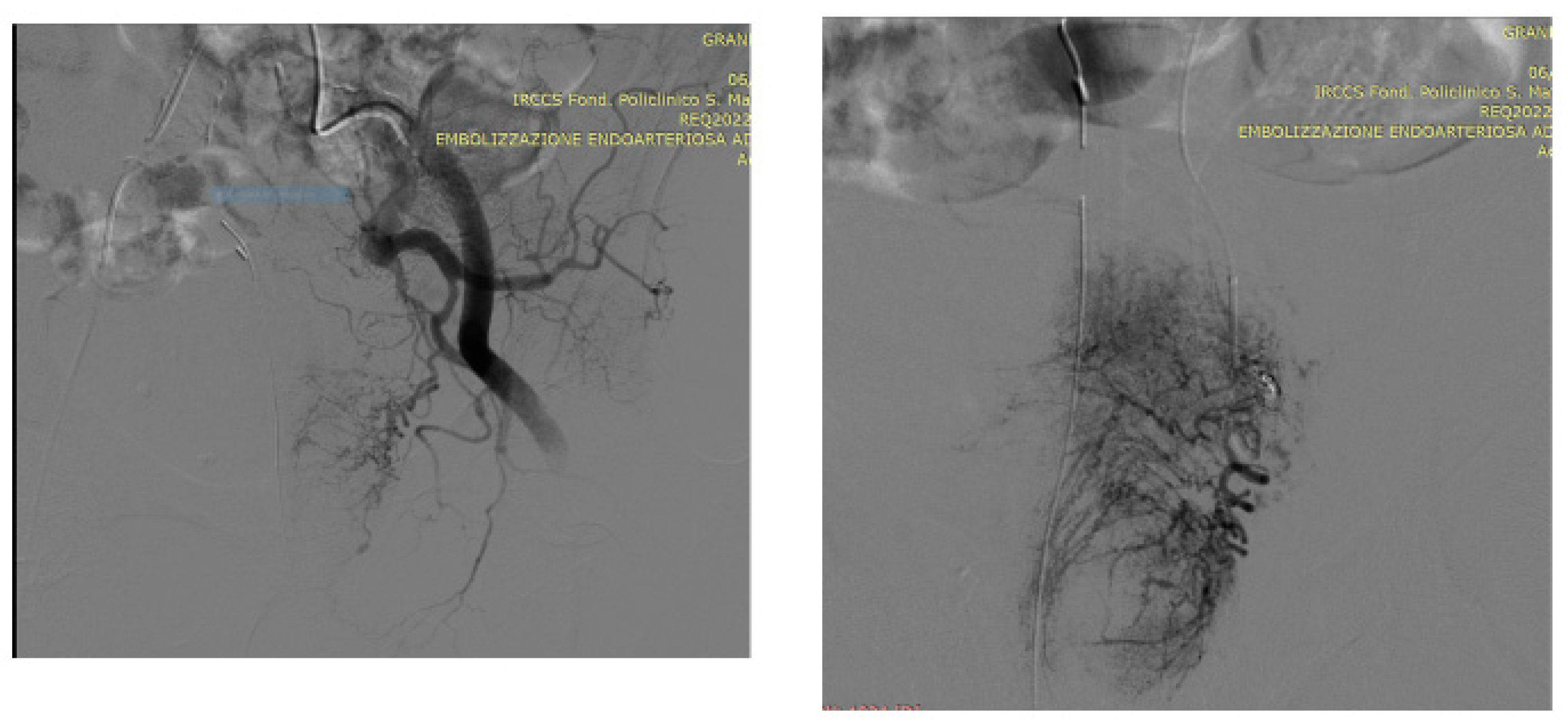

5.1. Technical details of PAE

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Abbreviations

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong MC, Goggins WB, Wang HH, Fung FD, Leung C, Wong SY, Sung JJ. Global incidence and mortality for prostate cancer: analysis of temporal patterns and trends in 36 countries. Eur Urol. 2016, 70, 862–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins A, Sundararajan V, Millar J, Burchell J, Le B, Krishnasamy M, et al. The trajectory of patients who die from metastatic prostate cancer: a population-based study. BJU Int. 2018.

- Babaian K, Truong M, Cetnar J, Cross DS, Shi F, Ritter MA, Jarrard DF. Analysis of urological procedures in men who died from prostate cancer using a population-based approach. BJU Int. 2013, 111, E65–E70. [Google Scholar]

- Rink JS, Froelich MF, McWilliams JP, Gratzke C, Huber T, Gresser E, Schoenberg SO, Diehl SJ, Nörenberg D. Prostatic Artery Embolization for Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: A Markov Model-Based Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. J Am Coll Radiol 2022; S1546-1440(22)00275-7. [CrossRef]

- Westwood J, Geraghty R, Jones P, Rai BP, Somani BK. Rezum: a new transurethral water vapour therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Ther Adv Urol 2018; 10:327-333.

- Mitchell ME, Waltman AC, Athanasoulis CA, Kerr WS Jr, Dretler SP. Control of massive prostatic bleeding with angiographic techniques. J Urol 1976, 115, 692–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, W.; Goertler, U. Successful intra-arterial embolization of bleeding carcinoma of the prostate. Urologe A, 1977, 16, 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Nadalini, V.F.; Positano, N.; Bruttino, G.P.; Medica, M.; Fasce, L. Therapeutic occlusion of the hypogastric arteries with isobutyl-2-cyanoacrylate in vesical and prostatic cancer. Radiol Med (Torino) 1981, 67, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Grosso, M.; Balderi, A.; Arnò, M.; Sortino, D.; Antonietti, A.; Pedrazzini, F.; Giovinazzo, G.; Vinay, C.; Maugeri, O.; Ambruosi, C.; Arena, G. Prostatic artery embolization in benign prostatic hyperplasia: preliminary results in 13 patients. Radiol Med 2015, 120, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisco, J.M.; Rio Tinto, H.; Campos Pinheiro, L.; Bilhim, T.; Duarte, M.; Fernandes, L.; Pereira, J.; Oliveira, A.G. Embolisation of prostatic arteries as treatment of moderate to severe lower urinary symptoms (LUTS) secondary to benign hyperplasia: results of short- and mid-term follow-up. Eur Radiol 2013, 23, 2561–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-Y.; Chai, Y.-M.; Huang, W.-H.; Zhang, Y. Prostate artery embolization on lower urinary tract symptoms related to benign prostatic hyperplasia: A systematic review and metaanalys. World J Clin Cases 2022, 10, 11812–11826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.C. Li BC. Internal iliac artery embolization for the control of severe bladder and prostate haemorrhage. Chung Hua Wai Ko Tsa Chic 1990; 28: 220-1, 253. Chinese.

- DeMeritt, J.S.; Elmasri, F.F.; Esposito, M.P.; Rosenberg, G.S. Relief of benign prostatic hyperplasia-related bladder outlet obstruction after transarterial polyvinyl alcohol prostate embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2000, 11, 767–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale FC, Antunes AA, da Motta Leal Filho JM, Oliveira Cerri LM, Baroni RH, Marcelino AS, et al. Prostatic artery embolization as a primary treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia: preliminary results in two patients. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol 2010; 33(2):355-61. [CrossRef]

- Lin Y-T, Amouyal G, Correas J-M, Pereira H, Pellerin O, Giudice CD, et al. Can prostatic arterial embolisation (PAE) reduce the volume of the peripheral zone? MRI evaluation of zonal anatomy and infarction after PAE. Eur Radiol 2016; 26:3466–73. [CrossRef]

- de Assis AM, Moreira AM, de Paula Rodrigues VC, Yoshinaga EM, Antunes AA, Harward SH, Srougi M, Carnevale FC. Prostatic artery embolization for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia in patients with prostates > 90 g: a prospective single-center study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015, 26, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmanis S, Lewis A, Mansoor A, Bircher M. Corona mortis: an anatomical study with clinical implications in approaches to the pelvis and acetabulum. Clin Anat 2007 May;20(4):433-9. [CrossRef]

- Bilhim T, Pisco J, Campos Pinheiro L, Rio Tinto H, Fernandes L, Pereira JA, Duarte M, Oliveira AG. Does polyvinyl alcohol particle size change the outcome of prostatic arterial embolization for benign prostatic hyperplasia? Results from a single-center randomized prospective study. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013, 24, 1595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao YA, Huang Y, Zhang R, Yang YD, Zhang Q, Hou M, Wang Y. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: prostatic arterial embolization versus transurethral resection of the prostate—a prospective, randomized, and controlled clinical trial. Radiology 2014, 270, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurbatov D, Russo GI, Lepetukhin A, Dubsky S, Sitkin I, Morgia G, Rozhivanov R, Cimino S, Sansalone S. Prostatic artery embolization for prostate volume greater than 80 cm3: results from a single-center prospective study. Urology 2014, 84, 400–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagla S, Martin CP, van Breda A, Sheridan MJ, Sterling KM, Papadouris D, Rholl KS, Smirniotopoulos JB, van Breda A. Early results from a United States trial of prostatic artery embolization in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2014, 25, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo GI, Kurbatov D, Sansalone S, Lepetukhin A, Dubsky S, Sitkin I, Salamone C, Fiorino L, Rozhivanov R, Cimino S, Morgia G. Prostatic arterial embolization vs open prostatectomy: a 1-year matched-pair analysis of functional outcomes and morbidities. Urology 2015, 86, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Q, Duan F, Wang MQ, Zhang GD, Yuan K. Prostatic Arterial Embolization with Small Sized Particles for the Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Due to Large Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Preliminary Results. Chin Med J (Engl) 2015, 128, 2072–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnevale FC, Iscaife A, Yoshinaga EM, Moreira AM, Antunes AA, Srougi M. Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) versus original and PErFecTED prostate artery embolization (PAE) due to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH): preliminary results of a single center, prospective, urodynamic-controlled analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2016, 39, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, F.C., Moreira, A.M., Antunes, A.A. The “PErFecTED Technique”: Proximal Embolization First, Then Embolize Distal for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2014; 37:1602–1605. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Guo L, Duan F, Yuan K, Zhang G, Li K, Yan J, Wang Y, Kang H. Prostatic arterial embolization for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia: a comparative study of medium- and large-volume prostates. BJU Int 2016, 117, 155–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabr AH, Gabr MF, Elmohamady BN, Ahmed AF. Prostatic artery embolization: a promising technique in the treatment of high-risk patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urol Int 2016, 97, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisco JM, Bilhim T, Pinheiro LC, Fernandes L, Pereira J, Costa NV, Duarte M, Oliveira AG. Medium- and long-term outcome of prostate artery embolization for patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia: Results in 630 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2016; 27:1115-1122. [CrossRef]

- Isaacson AJ, Raynor MC, Yu H, Burke CT. Prostatic artery embolization using Embosphere microspheres for prostates measuring 80-150 cm3: early results from a US trial. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2016, 27, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu SC, Cho CC, Hung EH, Chiu PK, Yee CH, Ng CF. Prostate artery embolization for complete urinary outflow obstruction due to benign prostatic hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2017, 40, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen JW, Shin JH, Tsao TF, Ko HG, Yoon HK, Han KC, Thamtorawat S, Hong B. Prostatic Arterial Embolization for Control of Hematuria in Patients with Advanced Prostate Cancer. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2017, 28, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mordasini L, Hechelhammer L, Diener P-A, Diebold J, Mattei A, Engeler D, et al. Prostatic artery embolization in the treatment of localized prostate cancer: a Bicentric Prospective Proof-of-Concept Study of 12 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2018; 29:589–97.

- Ray AF, Powell J, Speakman MJ, Longford NT, DasGupta R, Bryant T, Modi S, Dyer J, Harris M, Carolan-Rees G, Hacking N. Efficacy and safety of prostate artery embolization for benign prostatic hyperplasia: an observational study and propensity-matched comparison with transurethral resection of the prostate (the UK-ROPE study). BJU Int 2018; 122:270-282.

- Abt D, Hechelhammer L, Müllhaupt G, Markart S, Güsewell S, Kessler TM, Schmid HP, Engeler DS, Mordasini L. Comparison of prostatic artery embolisation (PAE) versus transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) for benign prostatic hyperplasia: randomised, open label, non-inferiority trial. BMJ 2018 Jun 19; 361:k2338. [CrossRef]

- Maclean D, Harris M, Drake T, Maher B, Modi S, Dyer J, Somani B, Hacking N, Bryant T. Factors predicting a good symptomatic outcome after prostate artery embolisation (PAE). Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2018; 41:1152–1159.

- Salem R, Hairston J, Hohlastos E, Riaz A, Kallini J, Gabr A, Ali R, Jenkins K, Karp J, Desai K, Thornburg B, Casalino D, Miller F, Hofer M, Hamoui N, Mouli S. Prostate artery embolization for lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia: results from a prospective FDA-approved investigational device exemption study. Urology 2018; 120:205–210.

- Franiel T, Aschenbach R, Trupp S, Lehmann T, von Rundstedt FC, Grimm MO, Teichgräber U. Prostatic Artery Embolization with 250-μm Spherical Polyzene-Coated Hydrogel Microspheres for Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms with Follow-up MR Imaging. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2018 Aug;29(8):1127-1137. [CrossRef]

- Brown N, Walker D, McBean R, Pokorny M, Kua B, Gianduzzo T, Dunglison N, Esler R, Yaxley J. Prostate artery Embolisation Assessment of Safety and feasibilitY (P-EASY): a potential alternative to long-term medical therapy for benign prostate hyperplasia. BJU Int 2018 Nov;122 Suppl 5:27-34. [CrossRef]

- Pisco J, Bilhim T, Costa NV, Ribeiro MP, Fernandes L, Oliveira AG. Safety and Efficacy of Prostatic Artery Chemoembolization for Prostate Cancer-Initial Experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2018 Mar;29(3):298-305. [CrossRef]

- Thulasidasan N, Kok HK, Elhage O, Clovis S, Popert R, Sabharwal T. Prostate artery embolisation: an all-comers, single-operator experience in 159 patients with lower urinary tract symptoms, urinary retention, or haematuria with medium-term follow-up. Clin Radiol 2019 Jul; 74(7):569.e1-569.e8. [CrossRef]

- Malling B, Røder MA, Lindh M, Freveri S, Brasso K, Lönn L. Palliative prostate artery embolisation for prostate cancer: a case series. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2019; 42:1405-1412.

- Rampoldi A, Barbosa F, Secco S, Migliorisi C, Galfano A, Prestini G, Harward SH, Di Trapani D, Brambillasca PM, Ruggero V, et al. Prostatic Artery Embolization as an Alternative to Indwelling Bladder Catheterization to Manage Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia in Poor Surgical Candidates. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol 2017; 40:530–536. [CrossRef]

- Peacock J, Sikaria D, Maun-Garcia L, Javedan K, Yamoah K, Parikh N. A Proof-of-Concept Study on the Use of Prostate Artery Embolization Before Definitive Radiation Therapy in Prostate Cancer. Adv Radiat Oncol 2020 Nov 21;6(3):100619. [CrossRef]

- Insausti I, Saez de Ocariz A, Galbete A, Capdevila F, Solchaga S, Giral P, et al. Randomized Comparison of Prostatic Artery Embolization versus Transurethral Resection of the Prostate for Treatment of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2020 Jun; 31(6):882-890. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapping CR, Little MW, Macdonald A, Mackinnon T, Kearns D, Macpherson R, Crew J, Boardman P. The STREAM Trial (Prostatic Artery Embolization for the Treatment of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia) 24-Month Clinical and Radiological Outcomes. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2021 Mar;44(3):436-442. [CrossRef]

- Saro H, Solyman MTh, Zaki M, Hasan NMA, Thulasidan N, Clovis S, Elhage O, Popert R, Sabharwal T. Prostate Artery Embolization in Patients above Eighty Years Old: Clinical Efficacy and Safety. Arab J Intervent Radiol 2022; 6:63–71.

- Insausti I, Galbete A, Lucas-Cava V, et al. “Prostatic artery embolization (PAE) using polyethylene glycol microspheres: safety and efficacy in 81 patients”. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol 2022; 45 (9):1339–1348.

- Picel AC, Hsieh TC, Shapiro RM, Vezeridis AM, Isaacson AJ. Prostatic Artery Embolization for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Patient Evaluation, Anatomy, and Technique for Successful Treatment. RadioGraphics 2019; 39(5):1526–1548.

- Carbone DJ, Hodges S. Medical therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia: sexual dysfunction and impact on quality of life. Int J Impot Res 2003; 15:299–306.

- Wang MQ, Guo LP, Zhang GD, Yuan K, Li K, Duan F, et al. Prostatic arterial embolization for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms due to large (> 80 mL) benign prostatic hyperplasia: results of midterm follow-up from Chinese population. BMC Urology 2015; 15:33.

- Delgal A, Cercueil JP, Koutlidis N, Michel F, Kermarrec I, Mourey E, Cormier L, Krausé D, Loffroy R. Outcome of transcatheter arterial embolization for bladder and prostate hemorrhage. J Urol 2010, 183, 1947–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszalek M, Ponholzer A, Rauchenwald M, Madersbacher S. Palliative transurethral resection of the prostate: functional outcome and impact on survival. BJU Int 2007; 99:56–9.

- Williams SG, Aw Yeang HX, Mitchell C, Caramia F, Byrne DJ, Fox SB, Haupt S, Schittenhelm RB, Neeson PJ, Haupt Y, Keam SP. Immune molecular profiling of a multiresistant primary prostate cancer with a neuroendocrine-like phenotype: a case report. BMC Urol 2020; 20(1):171. [CrossRef]

- Kably IM, Bhatia SS, Narayanan G. Prostatic Artery Embolization for Intractable Hematuria in Prostate Cancer. Intervent Oncol 360 2015, 3, E30–E35.

- Deng L, Li C, He Q, Huang C, Chen Q, Zhang S, Wang L, Gan Y, Long Z. Superselective Prostate Artery Embolization for Treatment of Severe Haematuria Secondary to Rapid Progression of Treatment-Induced Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer: A Case Report. Onco Targets Ther 2022; 15:67-75. [CrossRef]

- Nerli RB, Adhikari P, Mulimani N, Bidi S, Rangrez S, Chandra S, Ghagane SC. Prostate Artery Embolisation as a Palliative Care in a Patient with Prostate Cancer: A Case Report. Oncology Case Reports 2020. [CrossRef]

- Parikh N, Keshishian E, Manley B, Grass GD, Torres-Roca J, Boulware D, Feuerlein S, Pow-Sang JM, Bagla S, Yamoah K, Bhatia S. Effectiveness and safety of prostatic artery embolization for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms from benign prostatic hyperplasia in men with concurrent localized prostate cancer. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2021, 32, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapping CR, Crew J, Proteroe A, Boardman P. Prostatic artery embolization (PAE) for prostatic origin bleeding in the context of prostate malignancy. Acta Radiol Open 2019; 8(6):2058460119846061. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia S, Harward SH, Sinha VK, Narayanan G. Prostate Artery Embolization via Transradial or Transulnar versus Transfemoral Arterial Access: Technical Results. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2017 Jun;28(6):898-905. [CrossRef]

- Gil R, Shim DJ, Kim D, Lee DH, Kim JJ, Lee JW. Prostatic Artery Embolization for Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms via Transradial Versus Transfemoral Artery Access: Single-Center Technical Outcomes. Korean J Radiol 2022 May;23(5):548-554. [CrossRef]

| Author year | Country | Type study | N.° | Age, mean | Particles μm |

Results | Compl./notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pisco [11] 2013 | Portugal | PROSP in BPH LUTS refractory to medical therapy | 89 | 74.1 | 180-300 | TS 97% 86/89. FU 12 M. At 1 M IPSS, QoL, PVR, IIEF improved, all p<0.01. |

1 bladder wall necrosis that needed surgery |

| Bilhmt [19] 2013 | Portugal | PROSP in BPH to verify particle size effects 100 μm (A) vs 200 μm (B) | 80 | 63.9 | 100-200 | FU 6 M. No significant differences were found in pain scores. A had a greater ↓ in PV (8.75 cm3 p<0.13), PSA level (2.09 ng/mL p <0.001); B had greater ↓ in IPSS (3.64 points p<0.052) and QoL (0.57 points p<0.07). | No significant differences were found in adverse events between 2 groups. |

| Gao [20] 2014 | China | COMP/PROSP in BPH LUTS PAE/TURP | PAE57 TURP57 | 67.7 66.4 | 355-500 | TS TURP 100% PAE 94.7%, CF 3.9%/9.4%. FU 24 M. IPSS, QoL, Qmax, PVR, PV, PSA had significant improvements in both groups. | TURP had greater improvements in IPSS, QoL, Qmax, and PVR at 1 and 3 M, and greater ↓ in PSA and PV when compared with the PAE group (P <0.05). |

| Kurbatov [21] 2014 | Italy Russia | PROSP in BPH | 88 | 66.4 | NK | FU 12 M | IPSS QoL Qmax PVR PV p<0.05 |

| Bagla [22] 2014 | U.S.A. | PROSP in BPH | 20 | 66.6 | PROSP in BPH LUTS | TS 90%, 10% due to ATH, Significant ↓ IPSS QoL | No minor/major compl. |

| Russo [23] 2015 | Italy Russia | COMP/PROSP PAE/OP | 80 | 67 | 300-500 | FU 12 M OP had lower IPSS p<0.05, PVR lower p<0.05, higher PF p<0.01; PAE showed higher Hb, shorter HS and IBC time. | PAE could be a feasible minimally invasive technique but failed to demonstrate superiority to OP because of the increased risk of persistent symptoms and low PF after 1 year. |

| de Assis17 2015 | Brazil | PROSP in BPH LUTS in PV > 90 g | 35 | 64.8 | NK | FU 3 M: mean PV ↓ from 135.1 g to 91.9 g p<0.0001, IPSS and QoL improved p<0.001. | A significant negative correlation was observed between PSA at 24 h after PAE and IPSS 3 months after PAE (P = .0057): excessively elevated PSA within 24 h is associated with lower IPSS. |

| Li [24] 2015 | China | 24 | 74.5 | 50-100 | TS 92% Bil 86%, UNI 14% due to ATH IPSS QoL PVR p<0.002 PV p<0.001 |

No major complications. AUR 32% HEM 14% UB 36% |

|

| Carnevale [25] 2016 | Brazil | COMP/PROSP in BPH TURP/PAE/Perf | PAE15 Perf15 TURP15 |

63.5 60.4 66.4 |

NK | IPSS, QoL, PV and Qmax significantly improved. TURP and Perf both had significantly lower IPSS than PAE but not significantly different from one another. TURP had significantly higher Qmax and smaller PV but required spinal anesthesia and ↑ HS. | Perf = Perfected Proximal Embolization First, Then Embolize Distal [26] |

| Wang [27] 2016 | China | COMP/PROSP 2 groups for mean PV: A 129 / B 64 ml |

115 | 71.5 | 100 | TS A 93.8% B 96.8%. FU 12 M. Better outcome in larger PV | IPSS QoL Qmax PVRV IIEF PSA PV significantly improved in both groups. |

| Gabr [28] 2016 | Saudi Arabia | PROSP in BPH LUTS UR and IBC | 22 | 72.5 | 300-500 | TS 100% | FU 9 M: IPSS Qmax PV PSA p<0.001 No major compl. |

| Pisco [29] 2016 | Portugal | PROSP in BPH LUTS refractory to therapy | 630 | 65.1 | NK | TS 98.1% BIL 92.6% UNI 7.4% Clinical success rates at 1-3 y and 3-6.5 y were 81.9% and 76.3% | IPSS QoL Qmax PV PSA IIEF PVR p<0.001 |

| Isaacson [30] 2016 | U.S.A. | PROSP BPH LUTS | 12 | 69 | NK | TS 100%. FU 3 M: mean improvements in IPSS and QoL were 18.3 points (5–27) and 3.6 points (1–6), respectively. | 7 cases transfemoral access, 5 cases transradial access. No major compl., no ischemic injuries. |

| Yu [31] 2017 | China | COMP/PROSP in BPH PAE in AUR and IBC weaning vs relieving LUTS without AUR | 27 | 66 | 100-300 | PAE BIL 100% IBC removed in 14/16 87.5% | Outcome comparable to cases without AUR No periprocedural compl. |

| Chen [32] 2017 | Korea Taiwan | PROSP in PCa stage 4 Refractory HEM | 9 | 71.9 | NK | FU 3 M: 2 recurrent HEM, 4 died no PAE related, 3 no HEM | No complications |

| Mordasini [33] 2018 |

Switerland | Prosp to provide PAE tumoricidal effect in PCa patients | 12 | 45-75 | 100 | Complete necrosis in 2, partial in 5, viable cancer cells in all 12 | Partial bladder wall necrosis in 2 requiring surgery |

| Ray [34] 2018 | UK | COMP/PROSP in BPH PAE/TURP | PAE216 TURP89 | 66 |

NK | PAE is clinically effective, producing a median 10-point IPSS improvement from baseline at 12 M while TURP has a median 15-point improvement. TURP HS is significantly longer than PAE. | PAE compl.: sepsis 1, blood transfusion 1, FAD 4, PSH 4, penil ulcers 2. PAE provides significant improvement in IPSS and QoL, although some of these improvements are greater in the TURP arm. |

| Abt [35] 2018 | Switzerland | COMP/PROSP BPH PAE 48 / TURP 51 | 99 | PAE 65.7 TURP 66.1 | 250-400 | FU 3 M: PAE and TURP show similar results | PAE BIL 75% UNI 25% PAE HS 2.2 / TURP HS 4.2 p <0.001 |

| Maclean [36] 2018 | UK | PROSP in BPH to study clinical outcome PAE and PV | 86 | 64.9 | NK | UNI/BIL TS% 100/96.5 |

No major compl. Initial PV and %PV reduction at 3 M predict good clinical outcomes at 12 M. |

| Salem [37] 2018 | U.S.A. | PROSP in BPH LUTS | 45 | 67 | NK | FU at 1-3-6-12 M IPSS QoL Qmax p<0.001 PVR at 6 M p 0.02, at 12 M p 0.025; PV ↓ p 0.001 | Minor compl.: dysuria 13, HEM 6, HEMS 2, urinary frequency 3 and UR 2. |

| Franiel [38] 2018 | Germany | PROSP in BPH to study MRI predictors of clinical success | 30 | 66 | 250 | TS 90% 27/30 BIL in 24 (89%). Significant MRI predictors of clinical success were not identified. | FU 1-3-6 M: IPSS < 18 with ↓ > 25%, QoL score < 4 with ↓ ≥ 1, Qmax ≥ 15 mL/s and ↑ ≥ 3.0 mL/s) rates: 59% (16/27), 63% (17/27), 74% (20/27). |

| Brown [39] 2018 | Australia | PROSP in BPH LUTS (40), HEM (1), IBC (10) | 51 | 67.8 | 250 | BIL 92.2% UNI 7.8% FU 3 M: IPSS, QoL, Qmax, PV p<0.001; PVR p<0.018. 7 cases 70% had IBC removal. |

PSH 11.8%, DYS 84.3%, perineal pain 25.5%, HEMS 11.8%, fever 9.8%, 1 medial uni gluteal irritation, 1 transient rectal hemorrhagic spot. |

| Pisco [40] 2018 | Portugal | PROSP PACE in PCa staging T2N0M0, 15 refused surgery, 5 wanted to stop HT | 20 | 67.5 | 150-300 | TS 80%, 16/20. BF 18.7%, 3/16 (PSA ↓ to < 2 ng/mL followed by PSA ↑ to > 2 ng/mL within 1 month after success). BS at 12-18 M was 62.5%, 10/16. | FU 12-18 M: 1 small bladder wall necrosis removed by surgery, 2 UR, 2 SDYS, all recovered. PACE allowed a biochemical response and is a promising treatment. |

| Thulasidasan [41] 2019 | UK | PROSP to study PAE BPH LUTS or RHOPA | 159 | 70 | 100-200 | TS 98% IBC removal in 13/24 in retention. PAE controlled HEM in 12/12 RHOPA cases. | The highest baseline IPSS and reduction in PV on the 1st MRI present the most benefit from PEA. |

| Mailling [42] 2019 | Denmark | Prosp in advanced PCa LUTS 9, UR 6 cases | 11 | 75,8 | 300-500 | TS 93.3%, 1 case unsuccessful due to ATH, bilateral 10/15; IPSS reduced 12.2 points | 4 cases did not have Fu: 2 died, 1 lost, 1 not done for Ather. |

| Rampoldi [43] 2019 | Italy | PROSP in BPH, IBC in all cases | 43 | 77,9 | 300-500 | BIL 76.7%, UNI 18%, 4.7% no done for ATH. IBC removal in 80.5% | TPV reduced p<0.001 UI 3/7.5%, UR 6/14.6% |

| Peacock [44] 2020 | U.S.A. | PROSP PEA before RT in PCa LUTS | 9 | 71 | 300-500 | FU 18 M in 5 that had RT at the same center. Mean IPSS after PEA 13.8 p<0.02, mean PV ↓ was 23.1%. No BF. | PAE is a clinically significant adjunctive therapy for alleviating LUTS and achieving significant volume reduction before RT, resulting in decreased radiation-related toxicity from prostate alone RT for PCa. |

| Insausti [45] 2020 | Spain | COMP/PROSP in BPH PAE/TURP | PAE 23 TURP 22 | ? | 300-500 | FU 12 M: PAE had IPSS ↓ p<0.08 and better QoL p<0.002; PV ↓ was better in TURP p<0.001. | PAE group had fewer compl. 15/47 (TURP) p<0.001. |

| Tapping [46] 2021 | UK | PROSP in BPH symptoms refractory to medical therapy | 50 | 67 | 200-500 | TS 96% 48/50. FU 24 M. IPSS at 24 M ↓ p<0.001, PV ↓ at 3 and 12 M but not significantly different at 24 M. | Initial PV was not a good predictor of CS. |

| Saro [47] 2022 | UK | PROSP in BPH and PCa LUTS and HEM | 54 | 85.29 | 180-300 | TS 92.6%. 30 surgery was contraindicated, no possible for ATH 4. IPSS and QoL significantly improved at 12 and 24 M. PAE was successful in 19 out of 20 with IBC for UR. | 17 patients, 4 PCa, had HEM: PAE resulted in CS in 16 with immediate bleeding stoppage. PV ↓ significantly within 6 M. IBC removal successful in 16 out of 17. No intra-or postprocedural compl. were encountered. |

| Insausti [48] 2022 | Spain | PROSP in BPH LUTS refractory to therapy | 81 | 73.87 | 400±75 | TS 100% BIL 85.2% UNI 14.8%: 3 cases impossibility PA cannulation, 4 PA perfused rectum or penis, 5 ATH. CS 78.5% | FU 12 M: IPSS Q=L Qmax p<0.01, PVR <0.05 Compl. 11 cases: 3 UI 3 UR, 3 PES, 1 ED, 1 FAD. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).