Submitted:

20 November 2023

Posted:

21 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sourcing of materials

2.2. Experimental design

2.3. Tests

2.4. X-ray fluorescence

2.5. X-ray diffraction

2.6. Life cycle assessment

3. Results and Discussion

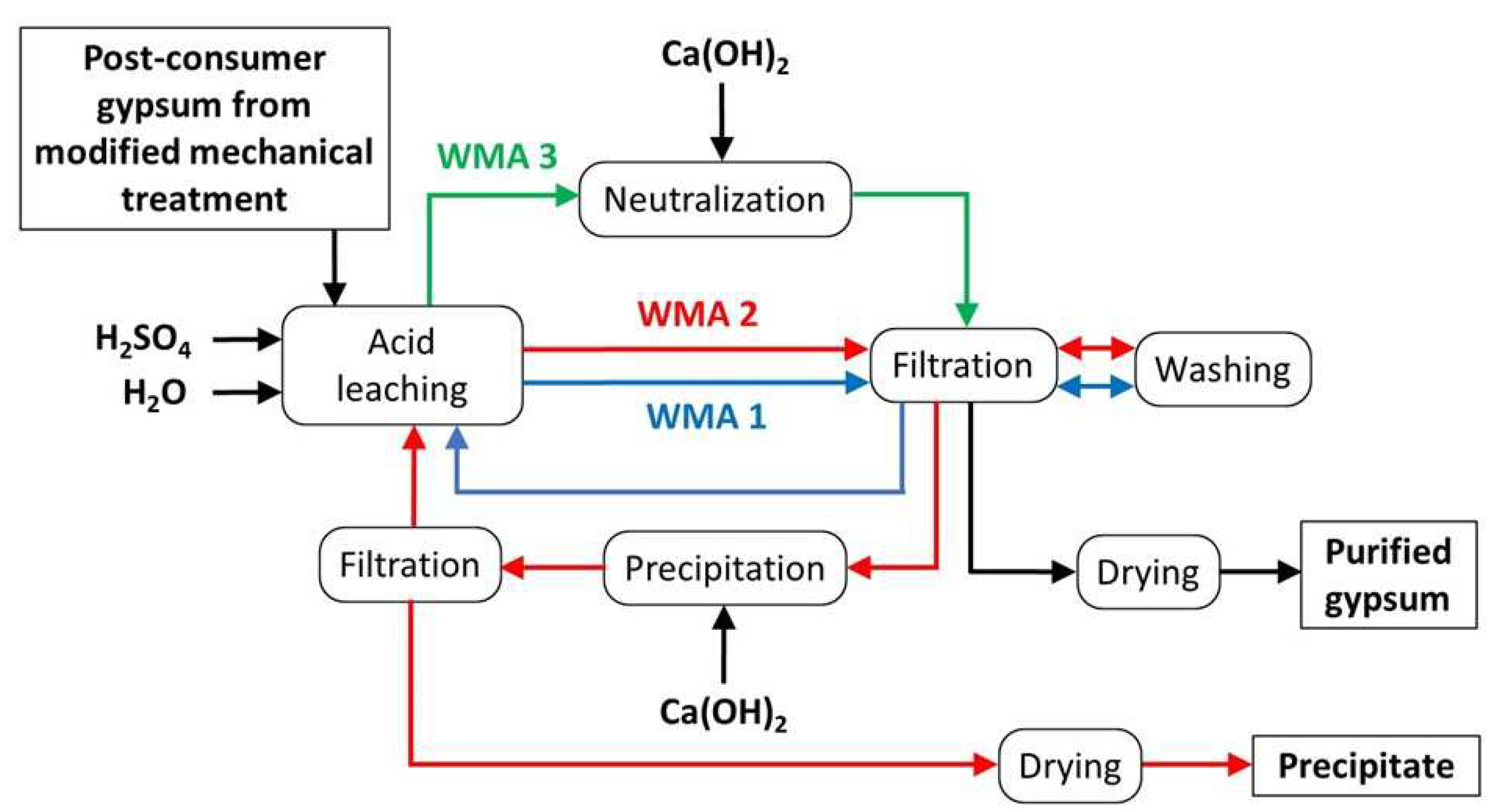

3.1. WMA 1

3.2. WMA 2

3.3. WMA 3

3.4. LCA

3.5. Comparison of WMA 3 with other acidic wastewater technologies

3.6. By-product applications

3.7. Potential barriers and enabling measures

4. Conclusions

- The reuse of acidic wastewater was not technically viable because there was no improvement in purified gypsum quality compared to the gypsum feedstock.

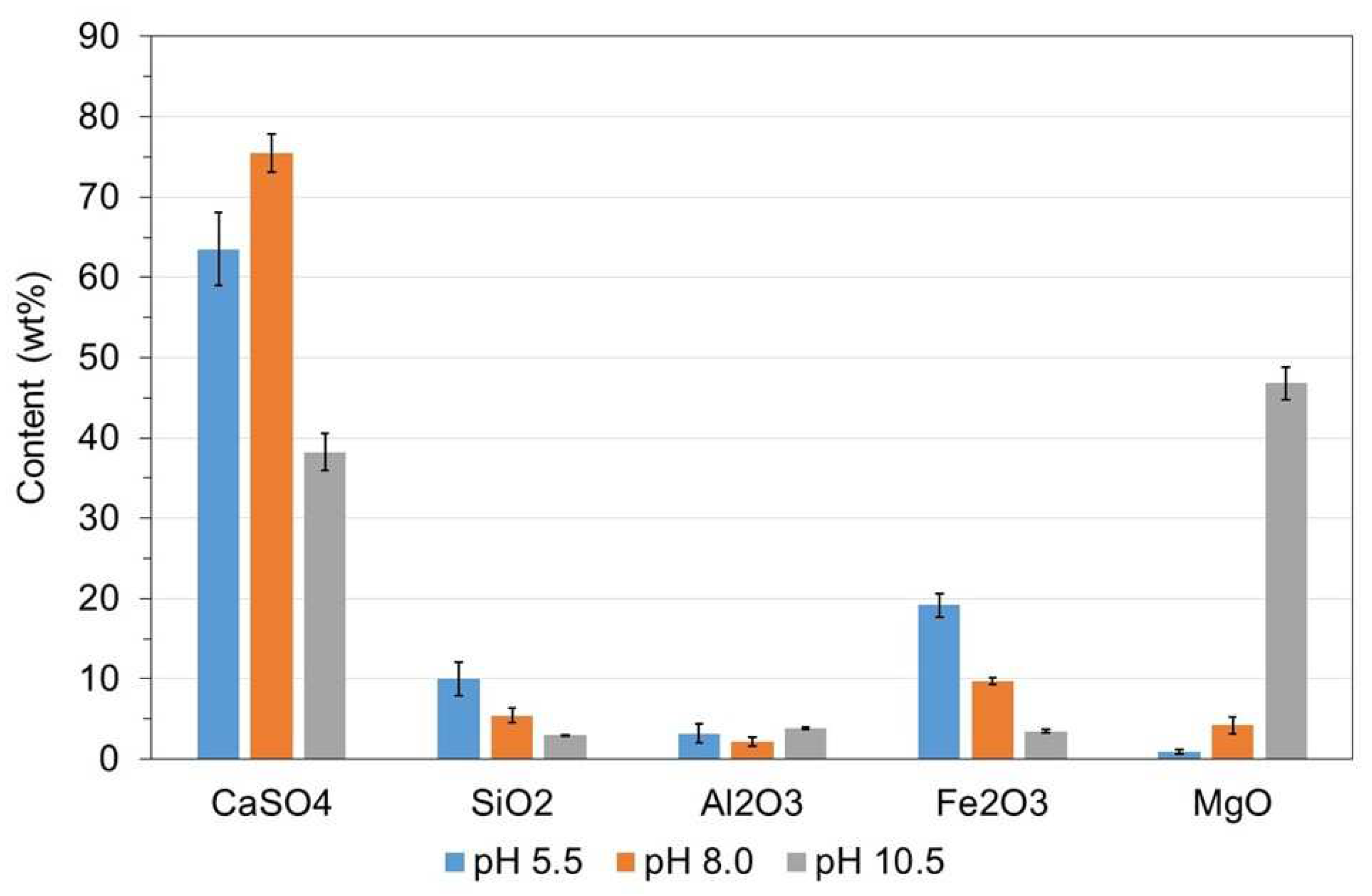

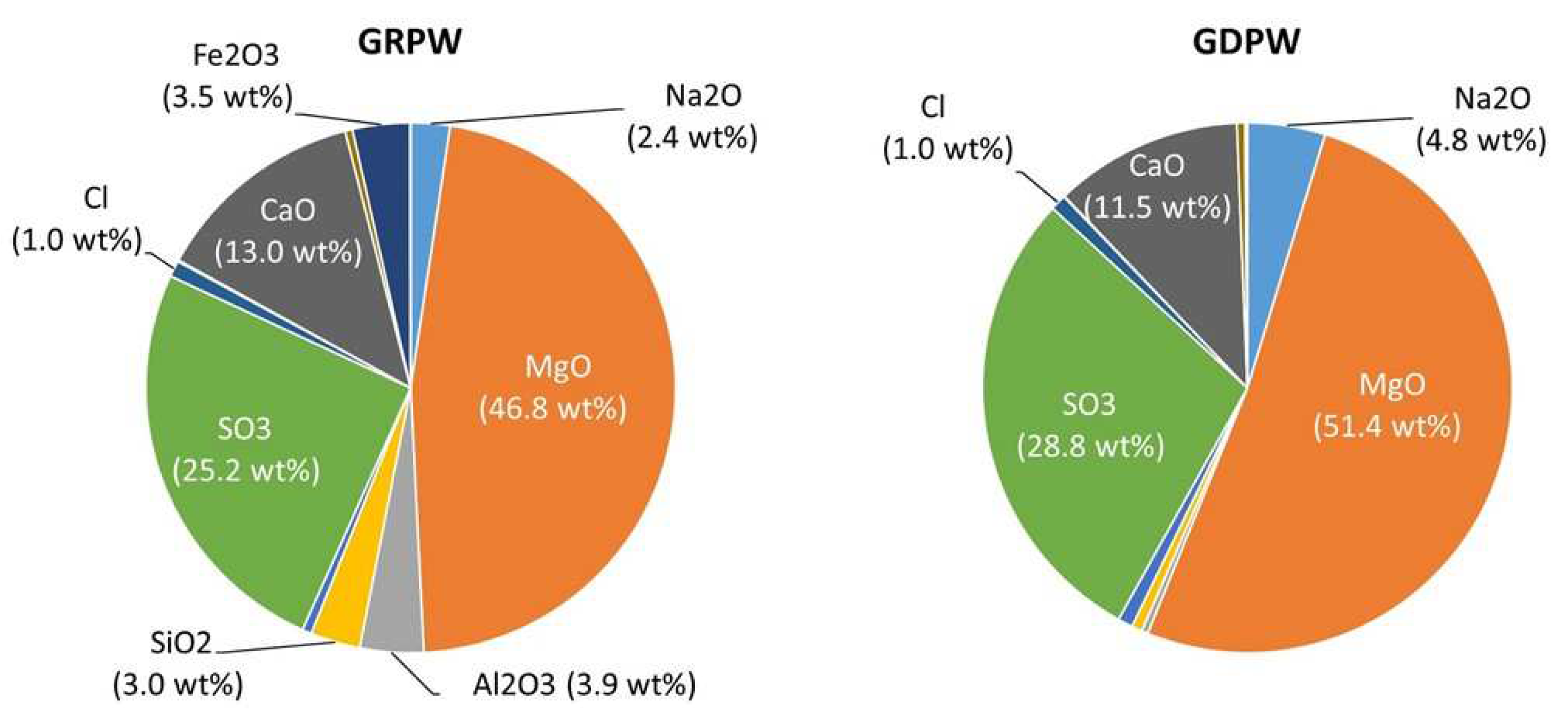

- A pH of 10.5 was required to precipitate Mg(OH)2 and the precipitate was a Mg-rich gypsum mainly composed of CaO, SO3 and MgO (≥85% on a weight basis).

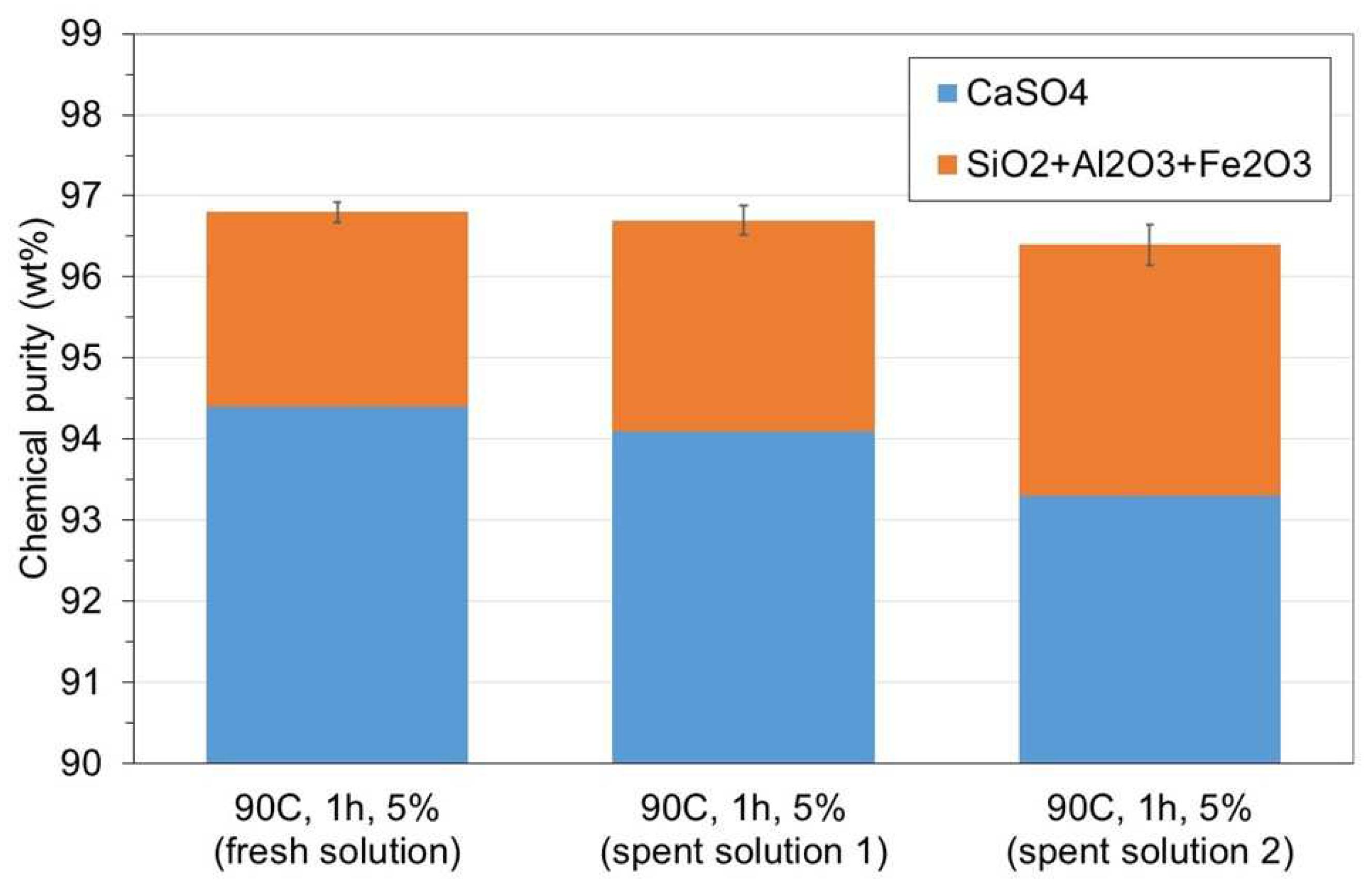

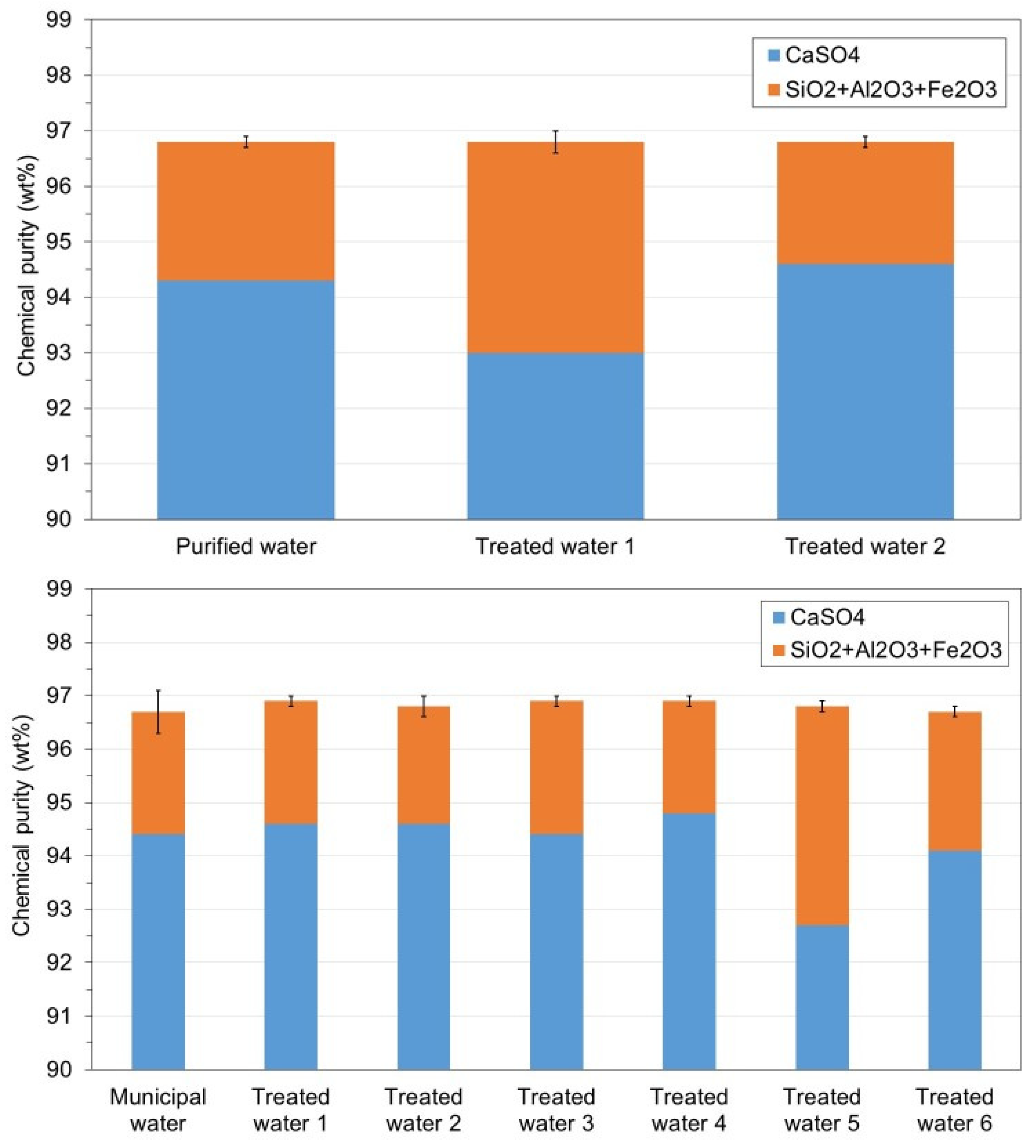

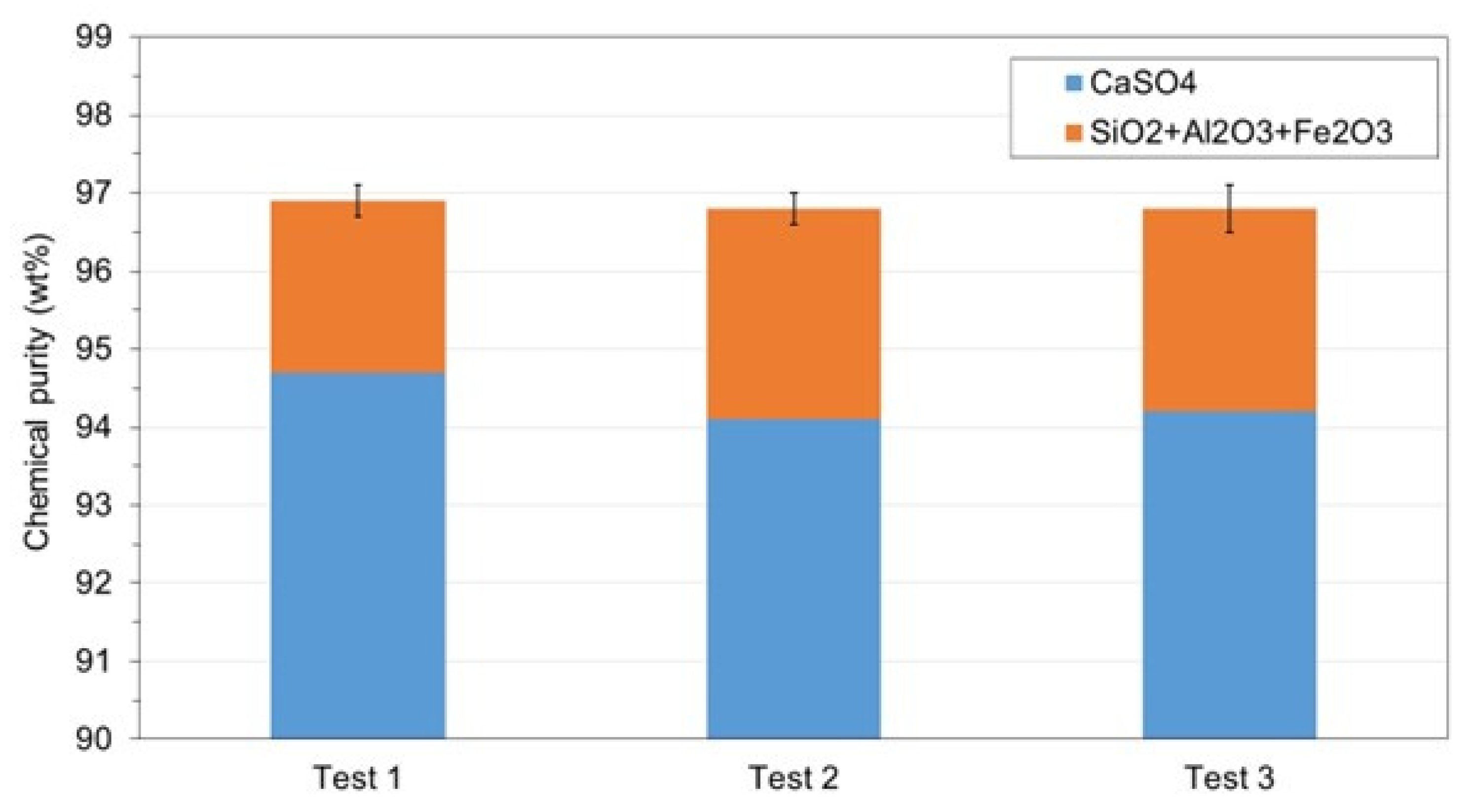

- The reuse of the treated water obtained after precipitation of the soluble impurities did not affect the chemical purity of the recycled gypsum after 6 cycles, enabling the reduction of water usage and wastewater disposal costs in the acid leaching gypsum purification plant.

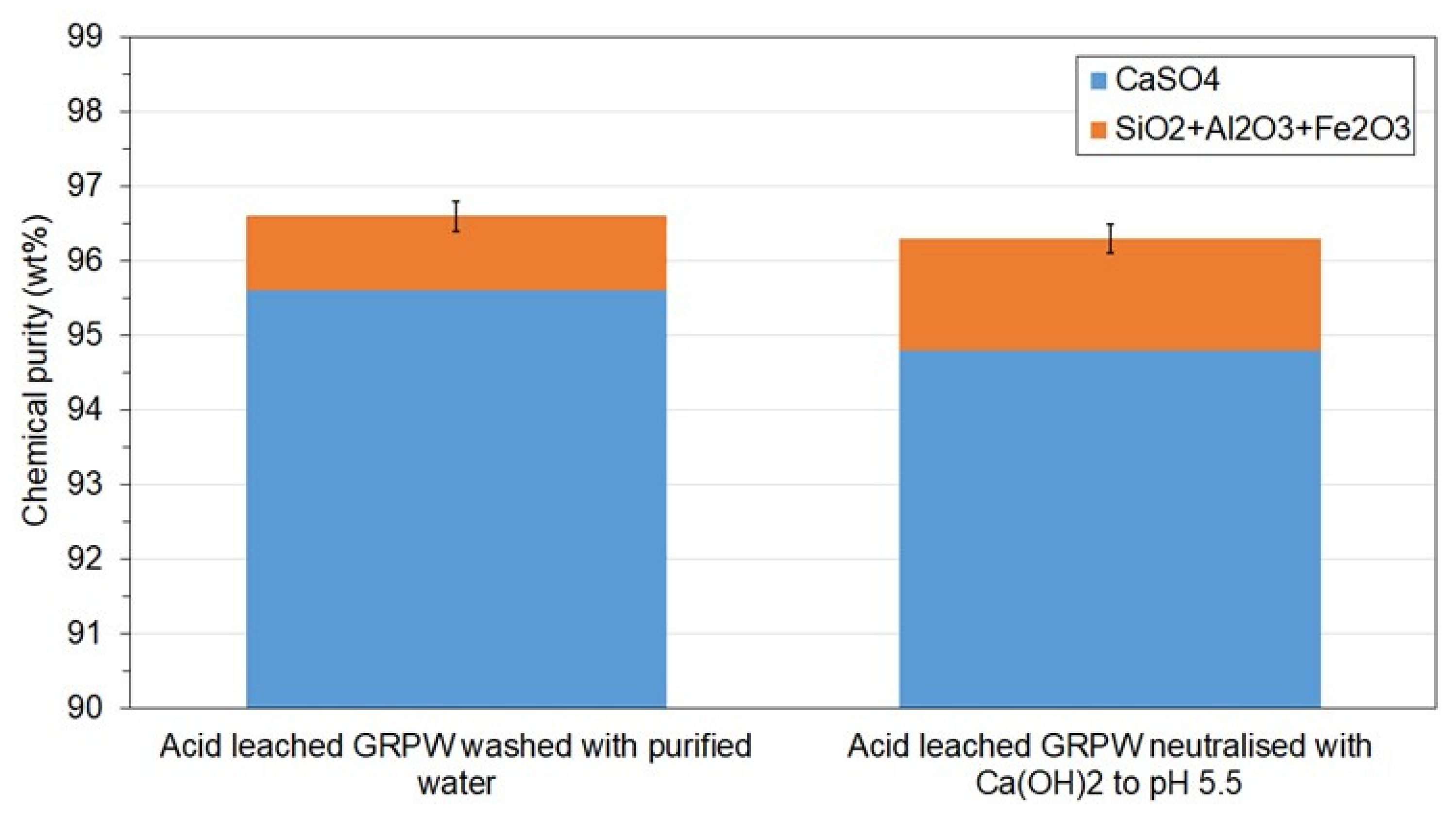

- Acid neutralization prior filtration did not reduce the chemical purity of the recycled gypsum but decreased its CaSO4 content by 0.8 wt%. The economic and environmental benefits of avoiding recycled gypsum cake washing and expensive corrosion-resistant equipment at the acid leaching gypsum purification plant would greatly compensate for this small reduction in CaSO4 content.

- The steps of the proposed in-house wastewater treatment are acid leaching, acid neutralization, purified gypsum (chemical purity > 96 wt%) filtration, purified gypsum cake drying, precipitation of soluble impurities in wastewater (Mg-rich gypsum), precipitate filtration, precipitate drying, and reuse of treated water in the acid leaching step.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Papailiopoulou, N.; Grigoropoulou, H.; Founti, M. Techno-economic impact assessment of recycled gypsum usage in plasterboard manufacturing. J. Remanufacturing 2019, 9, 141–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Díaz, M.; Osmani, M.; Cavalaro, S.; Needham, P.; Parker, B.; Lovato, T. Acid leaching technology for post-consumer gypsum purification. Open Research Europe 2023, 3, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 3. EEA Report No 23/2018. Industrial waste water treatment–pressures on Europe’s environment. European Environment Agency, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2800/496223 (accessed on the 14th of September 2023). [CrossRef]

- 4. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/60/oj (accessed on the 14th of September 2023).

- EPA’s Clean Water Act 1972. https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-clean-water-act (accessed on the 14th of September 2023).

- Chen, Q.; Ding, W.; Sun, H.; Peng, T. Synthesis of anhydrite from red gypsum and acidic wastewater treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 124026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEAP, 2020. EU’s Circular Economy Action Plan for a cleaner and more competitive Europe. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1583933814386&uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (accessed on the 14th of September 2023).

- Yun, T.; Chung, J.W.; Kwak, S.-Y. Recovery of sulfuric acid aqueous solution from copper-refining sulfuric acid wastewater using nanofiltration membrane process. J. Environ. Manage. 2018, 223, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potgieter, J.H.; Potgieter, S.S.; McCrindle, R.I.; Strydom, C.A. An investigation into the effect of various chemical and physical treatments of a South African phosphogypsum to render it suitable as a set retarder for cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 1223–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, E.M.; Strydom, C.A. Purification of South African phosphogypsum for use as Portland cement retarder by a combined thermal and sulphuric acid treatment method. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2004, 100, 411–414. [Google Scholar]

- Aliedeh, M.A.; Jarrah, N.A. Application of full factorial design to optimize phosphogypsum beneficiation process (P2O5 reduction) by using sulphuric and nitric acid solutions. In Proceedings of the Sixth Jordanian International Chemical Engineering Conference, Amman, Jordan, 12-14 March 2012. https://jeaconf.org/UploadedFiles/Document/31365fa2-c30a-442c-ae60-bea341617140.pdf (accessed on the 14th of September 2023).

- Al-Hwaiti, M.S. Influence of treated waste phosphogypsum materials on the properties of ordinary portland cement. Bangladesh J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2015, 50, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, D.N.; Chi, N.K.; Lam, T.D.; Truyen, C.Q.; Kiên, T.T.; Dinh, D.T. Purification of phosphogypsum for use as cement retarder by sulphuric acid treatment. Vietnam J. Sci. Technol. 2020, 58, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokshin, E.P.; Tareeva, O.A.; Elizarova, I.R. On integrated processing of phosphogypsum. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2013, 86, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokshin, E.P.; Tareeva, O.A. Production of high-quality gypsum raw materials from phosphogypsum. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2015, 88, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moalla, R.; Gargouri, M.; Khmiri, F.; Kamoun, L.; Zairi, M. Phosphogypsum purification for plaster production: A process optimization using full factorial design. Environ. Eng. Res. 2018, 23, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennaciri, Y.; Zdah, I.; Alaoui-Belghiti, H.E.; Bettach, M. Characterization and purification of waste phosphogypsum to make it suitable for use in the plaster and the cement industry. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2020, 207, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Išek, J.I.; Kaluđerović, L.M.; Vuković, N.S.; Milošević, M.; Vukašinović, I.; Tomić, Z.P. Refinement of waste phosphogypsum from Prahovo, Serbia: characterization and assessment of application in civil engineering. Clay Miner. 2020, 55, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosinski, A.; Kowalczyk, J.; Mazanek, C. Development of the Polish wasteless technology of apatite phosphogypsum utilization with recovery of rare-earths. J. Alloy. Compd. 1993, 200, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkov, A.V.; Andreev, V.A.; Anufrieva, A.V.; Makaseev, Y.N.; Bezrukova, S.A.; Demyanenko, N.V. Phosphogypsum technology with the extraction of valuable components. Procedia Chem. 2014, 11, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammas-Nasri, I.; Horchani-Naifer, K.; Férid, M.; Barca, D. Rare earths concentration from phosphogypsum waste by two-step leaching method. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2016, 149, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walawalkar, M.; Nichol, C.K.; Azimi, G. Process investigation of the acid leaching of rare earth elements from phosphogypsum using HCl, HNO3 and H2SO4. Hydrometallurgy 2016, 166, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychkov, V.N.; Kirillov, E.V.; Kirillov, S.V.; Semenishchev, V.S.; Bunkov, G.M.; Botalov, M.S.; Smyshlyaev, D.V.; Malyshev, A.S. Recovery of rare earth elements from phosphogypsum. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masmoudi-Soussi, A.; Hammas-Nasri, I.; Horchani-Naifer, K.; Ferid, M. Rare earths recovery by fractional precipitation from a sulfuric leach liquor obtained after phosphogypsum processing. Hydrometallurgy 2020, 191, 105253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brückner, L.; Elwert, T.; Schirmer, T. Extraction of rare earth elements from phosphogypsum: Concentrate digestion, leaching, and purification. Metals 2020, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040, 2006: Environmental management—Life cycle assessment principles and framework. International Standards Organization, Geneva. https://www.iso.org/standard/37456.html (accessed on the 14th of September 2023). 20 September.

- Semerjian, L.; Ayoub, G.M. High-pH-magnesium coagulation-flocculation in wastewater treatment. Adv. Environ. Res. 2003, 7, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Wu, B.; Zhu, J.; Fan, X.; Cai, P.; Wen, J.; Liu, X. Preparation of magnesium hydroxide from leachate of dolomitic phosphate ore with dilute waste acid from titanium dioxide production. Hydrometallurgy 2014, 142, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolonen, E.-T.; Rämö, J.; Lassi, U. The effect of magnesium on partial sulphate removal from mine water as gypsum. J. Environ. Manage. 2015, 159, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Fan, S.; Wu, Y.; Hu, H.; Feng, Z.; Huang, Z.; Liang, J.; Qin, Y. A stepwise processing strategy for treating highly acidic wastewater and comprehensive utilization of the products derived from different treating steps. Chemosphere 2021, 280, 130646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, M.; Knauf, O.; Mäkinen, J.; Yang, X.; Koukkari, P. Integrated acid leaching and biological sulfate reduction of phosphogypsum for REE recovery. Miner. Eng. 2020, 155, 106408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefeni, K.K.; Msagati, T.A.M.; Mamba, B.B. Acid mine drainage: Prevention, treatment options, and resource recovery: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on waste and repealing certain Directives. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/98/oj (accessed on the 14th of September 2023).

- Regulation (EU) 2019/1009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 laying down rules on the making available on the market of EU fertilising products and amending Regulations (EC) No 1069/2009 and (EC) No 1107/2009 and repealing Regulation (EC) No 2003/2003. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1009/oj (accessed on the 14th of September 2023).

- Commission regulation (EU) No 463/2013 of 17 May 2013 amending Regulation (EC) No 2003/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council relating to fertilisers for the purposes of adapting Annexes I, II and IV thereto to technical progress. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2013/463/oj (accessed on the 14th of September 2023).

- Ritchey, K.D.; Snuffer, J.D. Limestone, gypsum, and magnesium oxide influence restoration of an abandoned Appalachian pasture. Agron. J. 2002, 94, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanda, A.F.; Jusop, S.; Ishak, C.F.; Othman, R. Utilization of magnesium-rich synthetic gypsum as magnesium fertilizer for oil palm grown on acidic soil. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaim, M.; Sibhatu, K.T.; Siregar, H.; Grass, I. Environmental, economic, and social consequences of the oil palm boom. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2020, 12, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hukari, S.; Hermann, L.; Nättorp, A. From wastewater to fertilisers—Technical overview and critical review of European legislation governing phosphorus recycling. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 542, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Arya, S.; Kumar, S. Industrial wastewater treatment: Current trends, bottlenecks, and best practices. Chemosphere 2021, 285, 131245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Directive 2014/52/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 amending Directive 2011/92/EU on the assessment of the effects of certain public and private projects on the environment Text with EEA relevance. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2014/52/oj (accessed on the 14th of September 2023).

- Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH), establishing a European Chemicals Agency, amending Directive 1999/45/EC and repealing Council Regulation (EEC) No 793/93 and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1488/94 as well as Council Directive 76/769/EEC and Commission Directives 91/155/EEC, 93/67/EEC, 93/105/EC and 2000/21/EC. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2006/1907/oj (accessed on the 14th of September 2023).

| Sample | SO3 | CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MnO | MgO | P2O5 | K2O | Na2O | Cl | Ni2O3 | SrO |

| GRPW | 63.7 | 30.6 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 | < 0.1 | 0.1 |

| GDPW | 62.5 | 30.7 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 0.2 | < 0.1 | 0.5 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 |

| Precipitates |

Gypsum, CaSO4.2H2O |

Portlandite, Ca(OH)2 |

Kieserite, MgSO4.H2O |

Brucite, Mg(OH)2 |

| GRPW, municipal water, pH 5.5 | 95.8 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| GRPW, municipal water, pH 8.0 | 94.1 | 3.4 | 0.9 | 1.6 |

| GRPW, municipal water, pH 10.5 | 86.3 | 6.4 | 3.5 | 3.8 |

| GDPW, purified water, pH 10.5 | 79.0 | 4.0 | 9.6 | 7.4 |

| GDPW, treated water 1, pH 10.5 | 81.7 | 3.3 | 6.1 | 8.9 |

| GDPW, treated water 2, pH 10.5 | 87.7 | 1.0 | 6.1 | 5.2 |

| Impact category | Unit | WMA 1 | WMA 2 | WMA 3 |

| Global warming | kg CO2 eq | 1551 | 1762 | 1545 |

| Stratospheric ozone depletion | kg CFC11 eq | 0.000595 | 0.000696 | 0.000564 |

| Ionizing radiation | kBq Co-60 eq | 396.60 | 544.52 | 410.41 |

| Ozone formation (human health) | kg NOx eq | 2.962 | 3.310 | 2.788 |

| Fine particulate matter formation | kg PM2.5 eq | 3.725 | 3.851 | 3.514 |

| Ozone formation (terrestrial ecosystems) | kg NOx eq | 3.021 | 3.372 | 2.843 |

| Terrestrial acidification | kg SO2 eq | 11.93 | 12.31 | 11.78 |

| Freshwater eutrophication | kg P eq | 0.689 | 0.684 | 0.645 |

| Marine eutrophication | kg N eq | 1.447 | 1.349 | 1.333 |

| Terrestrial ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 19275 | 19513 | 19044 |

| Freshwater ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 186.4 | 191.3 | 185.4 |

| Marine ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 244.8 | 251.5 | 243.3 |

| Human carcinogenic toxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 101.7 | 101.5 | 93.9 |

| Human non-carcinogenic toxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 3652 | 3713 | 3587 |

| Land use | m2a crop eq | 83.6 | 103.9 | 86.1 |

| Mineral resource scarcity | kg Cu eq | -0.607 | -0.466 | -6.230 |

| Fossil resource scarcity | kg oil eq | 461.7 | 539.2 | 461.8 |

| Water consumption | m3 | 38.64 | 40.63 | 41.62 |

| Barriers (B) | Enabling measures (M) | |

| Legal | B1. Lack of local, regional, national, EU-wide permits and authorization processes for the installation and operation of acidic wastewater treatment plants and disposal of the treated water after maximum utilization cycles. | M1. New local, national, EU-wide regulations for acidic wastewater treatment plants and effluent disposal, or adaptation of existing regulations (e.g., EU’s Environmental Impact Assessment Directive [41]). |

| B2. Lack of regulations for the magnesium-rich gypsum as a fertilizer or soil ameliorant product. | M2. Adaptation of End-of-Waste criteria of the EU’s Waste Framework Directive4, Fertilizers Regulation33, and Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) Regulation [42]. | |

| Social | B3. Low acceptance of the magnesium-rich gypsum fertilizer or soil ameliorant by the agricultural industry due to lack of knowledge. | M3. Dissemination campaigns for practitioners (e.g., specialist magazines, workshops, etc.) to highlight sustainability benefits and provide guidance for application as fertilizer or soil ameliorant. Wastewater sustainability guidelines issued by Governments. |

| Technical | B4. Inconsistent quality of the magnesium-rich gypsum fertilizer or soil ameliorant that restricts its commercialization. | M4. Quality control of incoming plasterboard waste and magnesium-rich gypsum by-product with training of operatives for effective wastewater treatment process management. |

| Economic | B5. Additional equipment, materials, energy, and labor costs in the acid leaching gypsum purification plant for the in-house wastewater treatment. | M5. Governments incentives in the form of tax rebates, financial and technical assistance to plasterboard recyclers in implementing the wastewater treatment technology and commercializing the magnesium-rich gypsum as fertilizer or soil ameliorant. |

| B6. Non-existent market or limited demand for the magnesium-rich gypsum as fertilizer or soil ameliorant. | M6. Identify and target niche agricultural markets with high demand of the magnesium-rich gypsum by-product. | |

| Environmental | B7. Adverse environmental impact on aquatic ecosystems after application of the magnesium-rich gypsum (e.g., water eutrophication). | M7. Research and development to monitor the magnesium-rich gypsum’s mobility in soils and aquatic ecosystems. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).