Introduction

Tarsal Tunnel syndrome is an entrapment neuropathy of the posterior tibial nerve and potentially its terminal branches under the flexor retinaculum and behind the medial malleolus of the ankle (Kalçık Ünan, 2021). Tarsal Tunnel syndrome can be characterized by local tenderness, pain, paresthesia, and heat, followed by numbness and tingling. Symptoms may become more permanent and severe, spreading toward the posterior, medial, or distal aspect of the lower extremity (Kalçık Ünan, 2021). The occurrence of nerve damage in the tarsal tunnel is unclear and thought to be underdiagnosed. However, it has been found to have a higher incidence in females and can be witnessed at any age (Kiel, 2022). Contributing factors to the incidence of tarsal tunnel syndrome include trauma, tight-fitting shoes, abnormal biomechanics, and systemic diseases, which may induce nerve or surrounding tissue inflammation (Dreyer, 2023). Left untreated, posterior tibial nerve compression can cause permanent nerve damage, atrophy, and persistent pain (Kiel, 2022). While many intervention strategies exist for treating tarsal tunnel, there is limited robust evidence to guide the clinical management of the syndrome (McSweeney, 2015). Currently, standard conservative management includes activity modification, physical rehabilitation, corticosteroid injections, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Rodríguez-Merchán, 2021). It remains unclear when to intervene with surgical procedures as opposed to conservative management due to the various stages of the disease and the need for a structured, stepwise approach when treating patients (McSweeney, 2015). Although the initiation of surgical intervention is unclear, there are a few different surgical approaches that are available. Three methods for decompression of the tibial nerve and its branches include open surgery, endoscopic surgery, and ultrasound-guided surgery (Iborra, 2020). Any surgical tarsal tunnel intervention can range in out-of-pocket costs from 3,000 to 7,000 USD with up to six weeks of recovery time for the patient. Novel alternative interventions are necessary for refractory connective tissue nerve damage, as surgery does not guarantee improvement given that surgical success rates vary from 44% to 96% (Rodríguez-Merchán, 2021). With uncertainty surrounding the treatment of Tarsal Tunnel defects, this study aims to propose an alternative intervention that targets explicit damage to the connective tissues surrounding the related nerves for patients who have failed conservative management and desire to avoid surgical intervention.

Compression of nerves can have varying etiologies, but most equate to breakdown, rearrangement from trauma, and damage to the surrounding structural tissues. This collapse of connective tissue puts excess pressure on specific points along a given nerve, deteriorating the protective cushioning surrounding nerve fascicles. Most connective tissues, including nerve extra cellular matrix (ECM), comprise collagenic matrices as their primary structural support component (Gao, 2013). Wharton’s jelly is a loose connective tissue found in the umbilical cord that cushions and protects the vessels within the cord from external forces and stretching. It contains collagen types I and III, hyaluronic acid, proteoglycans, growth factors, and cytokines. Hydrodissection of a compressed nerve with Wharton’s jelly can supplement the damaged protective coating and provide additional cushioning to the nerve, as well as replace surrounding collapsed connective tissues, promoting proper function. The retrospective repository used in this study is facilitated by Regenative Labs, containing data on over 180+ beneficial homologous uses for Wharton’s jelly tissue allografts, including musculoskeletal defects. This case series presents data from patient-reported pain scales in the retrospective repository of eight patients who received one application of Wharton’s jelly to refractory nerve damage and compression within the tarsal tunnel.

Materials and Methods

All methods complied with the FDA and American Association of Tissue Banks (AATB) standards. This study was conducted under an Institute of Regenerative and Cellular Medicine IRB-approved protocol (RL-UCT-001), and informed consent was obtained from the study participant. Wharton’s jelly tissue allograft was processed and distributed by Regenative Labs.

Case Presentation

This retrospective case study pulled patients from the Regenative Labs repository with complete data sets, documented tarsal tunnel nerve-related defects, and received only one 2mL application of the 150mg Wharton’s jelly tissue allograft. Complete data sets include pain scales recorded at initial, 30-day, and 90-day visits. The pain scale utilized in this study is the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS), and the function rating scale used is the Western Ontario and McMaster University Arthritis Index (WOMAC). Following these requirements, eight patients with nerve damage on one or both legs were obtained from 4 clinics. The participating clinics in this study include Enhanced Healthcare of the Ozarks, Baycity Associates in Podiatry, Regenerative Health 360, and Advanced Medicine of the Ozarks. Data sets were completed for each extremity separately. The severity of neuropathy among the participants in this study was determined at each clinic through several tests that assess the different nerve senses.

The tests could include Graphesthesia, Rebuilder Mitt Test, reflex reactions, Romberg test, and Tandem test. The Graphesthesia test interprets ambiguous tactile symbols from different spatial perspectives (Arnold, 2017). The Rebuilder Mitt test uses medical device mitts that send electrical signals to the nerves and muscles that are an exacerbated sensation of the typical nerve signals. The signals from the mitts function to stimulate the nerves and strengthen the muscles. Reflex reactions were tested in the ankle as neuropathy affects sensory and motor components (Malik, 2013). The Romberg test removes the visual and vestibular components that contribute to balance to identify a particular impairment in patients with proprioception difficulties (Forbes, 2023). The Tandem test is used to screen for neurological and vestibular disorders by having the patient close their eyes and walk. While the patient walks, the test administrator counts the number of consecutive tandem steps out of ten (Cohen, 2018). Additional devices to assess patient neuropathy include cold sensitivity, a pinwheel device to evaluate the ability to feel sharp or pointed sensations, vibrations through the use of a tuning fork, a medi-tip to test pinprick sensation and determine between sharp and dull sensations, and 10g monofilament (Fred Nelson, 2015). Temperatures in the feet, forearms, and face, along with oxygen in the feet and hands, are compared to assure symmetrical sensation. The purpose of these tests is to provide a baseline of sensory loss. If the results of the sensory test show that sensory loss is only in the feet, then a specific amount of Wharton’s jelly is applied in specific anatomical sites of the foot.

This study included eight patients, one female and seven males, who presented with nerve defects in the tarsal tunnel aspect of their lower extremities. Two patients received WJ in their right foot only, and four patients received WJ in their left foot. Two patients received WJ in both their feet. The age distribution included one patient in the range of 40-49, six in the range of 70-79, and one in the range of 80-89. BMI distribution included four patients who were categorically overweight, two patients who were obese, and two patients who had an unreported BMI.

Procedure

A 25-gauge needle was used in the application of the WJ tissue allograft. The application is not a guided entry. If sensory loss was present only in the foot, a total of 2mL WJ was applied in 3 separate injection sites. The sites include 0.5 cc of WJ at the posterior tibial nerve, 0.5 cc at the medial plantar nerve, and one cc at the superficial peroneal nerve on the dorsal side of the foot. If the neuropathy extended upwards towards the patella, then a total of 2mL WJ was applied in four different injection sites. 0.5 cc into the lateral calcaneus branch, 0.5 cc to the lateral peroneal nerve just below the patella, 0.5 cc to the medial plantar nerve, and 0.5 cc to the posterior tibial nerve. Some providers recommended that the patient receive high-powered laser therapy or red-light therapy as well as vibration therapy at home daily.

Results

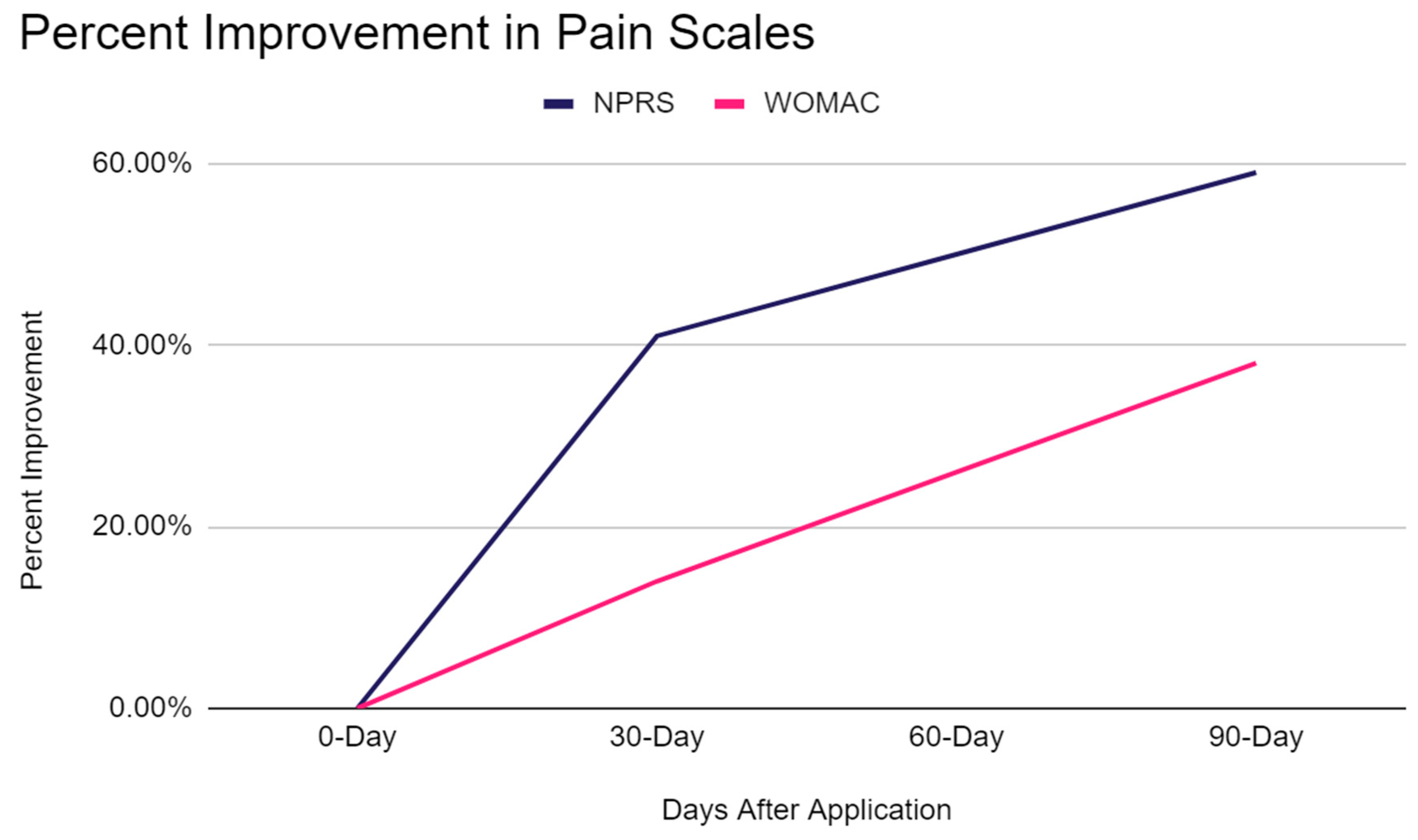

The percent change of improvement in patient pain scales was calculated with the cohort averages at initial application, 30-day follow-up, and 90-day follow-up appointments. The average NPRS score was 6.7 at the initial application appointment, and WOMAC was 30.6. At the 30-day follow-up, NPRS was 4.8, and WOMAC was 26.8. At the 90-day follow-up, NPRS was 2.75, and WOMAC was 19.1. Percent improvement was calculated for NPRS and WOMAC from initial to 30-day and 90-day follow-up appointments. From the initial application to the 30-day follow-up, there was a 41.20% improvement in NPRS and a 14.18% improvement in WOMAC. Finally, the initial application to 90-day follow-up showed an improvement of 59.43% in NPRS and a 37.58% improvement in WOMAC. Overall, the most significant improvement was seen in the NPRS category from initial application to the 90-day follow-up, but all patients experienced significant improvements in pain.

Figure 1 compares the percent improvement in the NPRS and WOMAC scales. The figure illustrates a steep improvement in NPRS from initial application to 30 days after application and a gradual improvement from 30 to 90 days. In comparison, WOMAC has a steady, gradual improvement from application to 90-day follow-up.

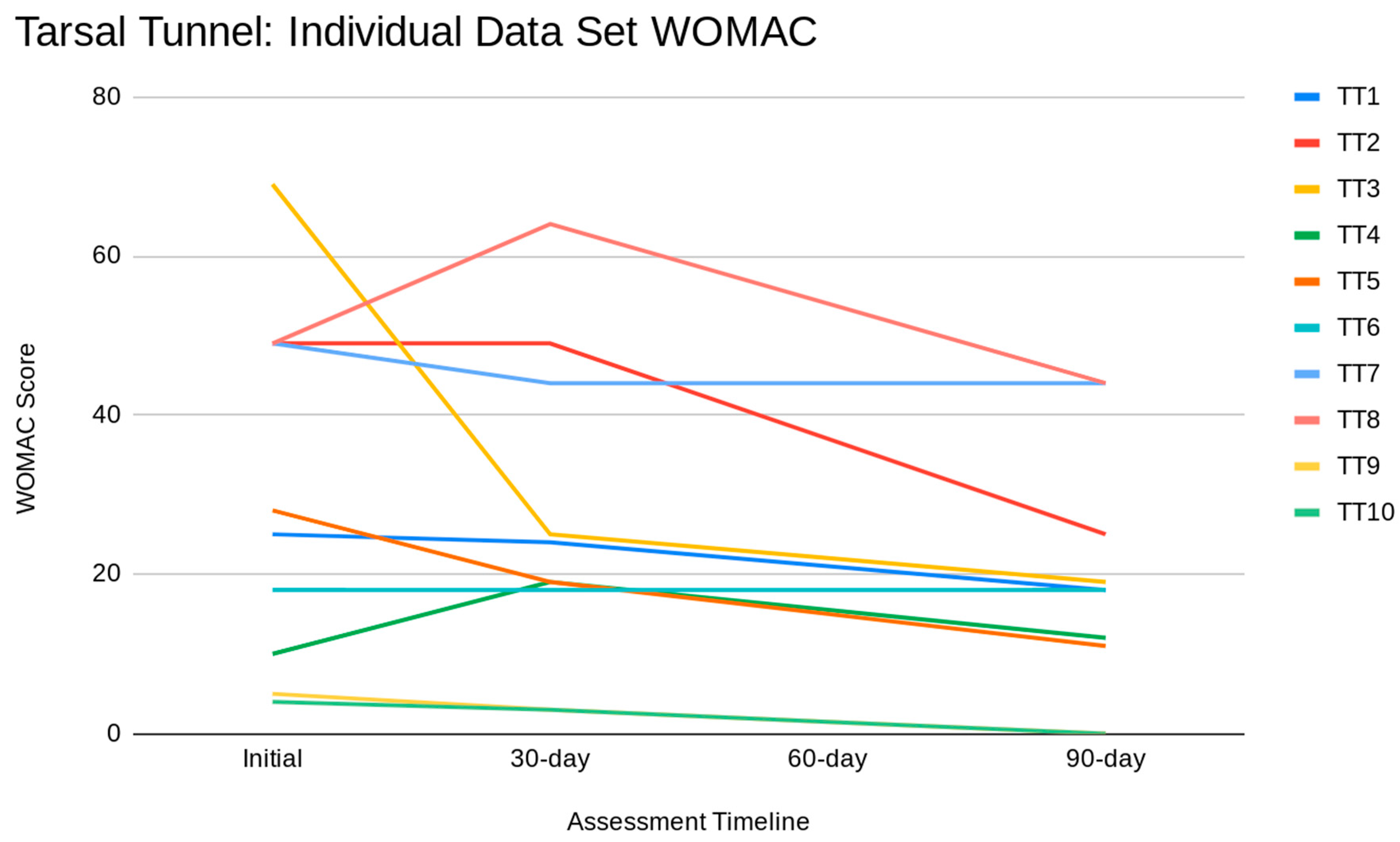

Figure 2 illustrates individual Tarsal Tunnel data sets for the WOMAC scale. It is essential to recognize that a higher WOMAC score correlates to increased pain.

Discussion

Given the reported pain improvements on various pain rating scales, this study provides evidence that WJ allograft applications are safe, minimally invasive, and efficacious for patients who have failed standard care treatments for connective tissue defects associated with Tarsal Tunnel syndrome. Of the patients in this study, no adverse reactions were reported. The results of this study warrant further research to confirm the efficacy of Wharton's jelly added to conservative care protocols. Additional studies may clarify the optimal dose, protocol, and durability of WJ allograft application. Limitations of this study include its small cohort size and non-blinded trial design. However, the effect of the survey being non-blinded is minimized by using patient-reported scales of NPRS and WOMAC, which quantize patient pain, functionality, and stiffness based on an array of questions. The positive results presented in this retrospective case series align with current literature on human tissue defects associated with knee osteoarthritis (Davis, 2022), articular cartilage defects affiliated with the sacroiliac joint (Lai, 2023), degenerative tissue in sacral decubitus ulcers (Lavor, 2023), and more. Patient-reported pain, joint stiffness, and physical function had a 20.52% improvement in the knee study by Davis, an 84% reduction in NPRS, and a 76% reduction in WOMAC in the sacroiliac joint study by Lai. The sacral decubitus ulcer study by Lavor showed one patient reporting a 94% decrease in wound volume and the other patient reporting a 100% decrease in wound volume after both patients had failed at least 30 months of conservative and procedural management before WJ application. Of these studies, no adverse reactions were reported, and significant pain improvement was seen in each study, making WJ allografts a promising alternative intervention for musculoskeletal and tissue defects.

This study implies significant importance in the potential of WJ to aid in tissue repair of collapsed connective tissues surrounding nerves and potentially nerve ECM as it demonstrates improved nerve sensation of patients enduring neuropathy associated with Tarsal Tunnel syndrome. WJ can be utilized homologously in patients suffering from neuropathy when directly addressing the connective tissues surrounding individual nerve fibers in three distinct components: the endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium (Pavelka, 2010). The individual nerve fiber is surrounded by the endoneurium, which is comprised of a network of collagen fibrils that function to hold together the nerve fibers and blood capillaries in larger nerve fiber bundles. The perineurium, followed by the epineurium, surrounds the endoneurium. The endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium are all connective tissues with individual responsibilities that function together as shielding and cushioning barriers for the impulse-conducting elements of the myelin sheath covering the nerve (Peltonen, 2013). Specifically important to this study is the function of the epineurium.

The epineurium primarily comprises a collagenous extracellular matrix surrounding the entire nerve, contributing to nerve tensile strength (Peltonen, 2013). Nerve damage leading to neuropathy may occur if the tissue surrounding the nerve does not fully support the nerve. When tissues endure pressure, they deform and create pressure gradients. Often, compression occurs at sites where a nerve runs through a tunnel that is formed by stiff tissue boundaries (Rempel, 1999). A study by Rempel tested the effects of compression damage on nerve sensation and found that axonal degeneration occurred with compression and correlated with endoneurial edema (1999). A study by Gao explains that ECM begins to participate in the nerve regeneration process in that epineurium, perineurium, and endoneurium, comprised of collagen, provide structural support for nerve regeneration (2013). Like the ECM of the nerve fiber, the primary function of WJ is to provide cushion, protection, and structural support to umbilical vessels by preventing their compression, torsion, and bending (Gupta, 2020). This study proposes that the application of WJ to the surrounding area of the affected nerve can supplement and promote the repair of the damaged tissue that is contributing to nerve compression. When WJ is applied directly to the nerve, it can replace the missing ECM and provide cushioning and support to the nerve fascicles, promoting standard functionality.

Given the function and components of WJ and the significant results in this study, WJ presents a promising alternative to the current standard of care practices and could potentially prevent further invasive procedures. Additional research with randomized control trials can statistically compare the efficacy and durability of WJ in connective nerve tissue supplementation for neuropathy patients with other standard non-invasive procedures.

Conclusions

The utilization of WJ allografts in applying tissue defects associated with tarsal tunnel syndrome shows improvement in patient pain and function. WJ can replace the damaged ECM and connective layers of the affected nerves, as well as cushion the nerve from exterior soft tissue damage, which leads to improved nerve sensation, ultimately decreasing neuropathy associated with Tarsal Tunnel syndrome. After failing other standard-of-care treatment options, the patients in this study were able to find relief with the application of WJ allografts. Future research may include a larger and more diverse cohort and a blinded control group to evaluate the safety and efficacy of WJ further and assist in defining dosage protocols in the application of tissue defects associated with Tarsal Tunnel syndrome.

References

- Kalçık Ünan, M., Ardıçoğlu, Ö., Pıhtılı Taş, N., Aydoğan Baykara, R., & Kamanlı, A. (2021). Assessment of the frequency of tarsal tunnel syndrome in rheumatoid arthritis. Turkish journal of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 67(4), 421–427. [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, M. A., & Gibboney, M. D. (2023). Anterior Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Kiel J, Kaiser K. Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome. [Updated 2022 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513273/.

- McSweeney, S. C., & Cichero, M. (2015). Tarsal tunnel syndrome—A narrative literature review. The Foot, 25(4), 244-250. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Merchán EC, Moracia-Ochagavía I. Tarsal tunnel syndrome: current rationale, indications and results. EFORT Open Rev. 2021 Dec 10;6(12):1140-1147. PMID: 35839088; PMCID: PMC8693231. [CrossRef]

- Gao X, Wang Y, Chen J, Peng J. The role of peripheral nerve ECM components in the tissue engineering nerve construction. Rev Neurosci. 2013;24(4):443-53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, G., & Auvray, M. (2017). The Graphesthesia Paradigm: Drawing Letters on the Body to Investigate the Embodied Nature of Perspective-Taking. i-Perception, 8(1), 2041669517690163. [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. M., Jindal, S., Bansal, S., Saxena, V., & Shukla, U. S. (2013). Relevance of ankle reflex as a screening test for diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism, 17(Suppl 1), S340–S341. (Suppl 1). [CrossRef]

- Forbes J, Munakomi S, Cronovich H. Romberg Test. [Updated 2023 Aug 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563187/.

- Cohen, H. S., Stitz, J., Sangi-Haghpeykar, H., Williams, S. P., Mulavara, A. P., Peters, B. T., & Bloomberg, J. J. (2018). Tandem walking as a quick screening test for vestibular disorders. The Laryngoscope, 128(7), 1687–1691. [CrossRef]

- Iborra, A., Villanueva, M. & Sanz-Ruiz, P. Results of ultrasound-guided release of tarsal tunnel syndrome: a review of 81 cases with a minimum follow-up of 18 months. J Orthop Surg Res 15, 30 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Davis JM, Sheinkop MB, Barrett TC. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Cryopreserved Human Umbilical Cord Tissue Allografts to Augment Functional and Pain Outcome Measures in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: An Observational Data Collection Study. Physiologia. 2022; 2(3):109-120. [CrossRef]

- Lai A, Shou J, Traina SA, Barrett T. The Durability and Efficacy of Cryopreserved Human Umbilical Cord Tissue Allograft for the Supplementation of Cartilage Defects Associated with the Sacroiliac Joint: A Case Series. Reports. 2023; 6(1):12. [CrossRef]

- Lavor M, Shou J, Mobarak R, Lambert N, Barrett T. Novel Application of Umbilical Cord Flowable Tissue Allografts in Sacral Decubitus Ulcers: A Case Study. 2023 Jan 05; 4(1): 014-022. Article ID: JBRES1644, Available at: https://www.jelsciences.com/articles/jbres1644.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Pavelka, M., Roth, J. (2010). Peripheral Nerve: Connective Tissue Components. In: Functional Ultrastructure. Springer, Vienna. [CrossRef]

- Peltonen, S., Alanne, M., & Peltonen, J. (2013). Barriers of the peripheral nerve. Tissue barriers, 1(3), e24956. [CrossRef]

- (definitions in explaining neuropathy) Fred R.T. Nelson, Carolyn Taliaferro Blauvelt. 12 - Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Physical Therapy and Occupational Therapy. A Manual of Orthopaedic Terminology (Eighth Edition). W.B. Saunders. 2015. Pages 365-375. ISBN 9780323221580. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (US) Steering Committee for the Workshop on Work-Related Musculoskeletal Injuries: The Research Base. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders: Report, Workshop Summary, and Workshop Papers. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1999. Biological Response of Peripheral Nerves to Loading: Pathophysiology of Nerve Compression Syndromes and Vibration Induced Neuropathy. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK230871/. 2308.

- Gao, X., Wang, Y., Chen, J., & Peng, J. (2013). The role of peripheral nerve ECM components in the tissue engineering nerve construction. Reviews in the neurosciences, 24(4), 443–453. (, 24, 4, 443–453. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).