1. Introduction

The problem of finding eigenvalues and eigenvectors of matrices is one of the main problems in computational physics and mathematics. One has to face this issue in the study of natural vibrations of various mechanical systems, vibrational and electronic spectra of molecules and crystals. This problem is of fundamental importance for quantum mechanics, which has become the basic discipline for studying the microcosm.

According to one of the main provisions of quantum mechanics, all observable quantities are eigenvalues of certain infinite-dimensional Hermitian operators. In addition, the finite element approximation of mathematical physics problems leads to the solution of this objective. At present, an important feature of these problems is the huge order of their matrices - up to a million or more unknown ones. Due to high orders, despite the sparse structure of matrices, the solution of such problems requires significant computing resources.

When creating preconditioners in the mixed finite-element approximations of the Stokes problem, structural mechanics and coupled problems, in the regularized interior-point methods, in the hydrodynamics, both in the theory and the constructing of the SLAE solvers, a difficult problem has to be solved. This is a generalized eigenvalue problem (GEP).

Finding eigenvalues of large scale sparse matrices is a rapidly developing area of numerical analysis, since solution of this problem became possible only with the advent of modern parallel computers. Previously, these problems were solved for small and moderate size matrices, and mainly using direct methods. At the moment, the most popular methods for solving the partial eigenvalue problem are the Krylov subspace methods [

1,

2,

3]. The main operation of these algorithms is matrix-vector multiplication, i.e., an operation that effectively uses the possibilities of parallel computing.

In this study we consider a model of an electro-elastic body in the acoustic liquid:

Acoustic liquid can be described as:

where

is stress tensor,

is an eigenvalue,

j is density for both solids and liquids,

is deformation,

u is displacement,

D is electrical induction,

E is electric field,

are mass forces,

is electrical potential,

,

,

are damping coefficient,

,

,

are stiffness, piezomodules and dielectric permittivity, correspondingly, index

j is a body number for multybody problems. For acoustic liquid part:

c is speed of sound,

s is speed vector,

is a vector of speed potentials,

p is sound pressure,

I is unit tensor,

b is dissipation coefficient.

This model describes piezoelectric materials that can be used as energy transformers and harvesters, as part of medical equipment, in non-damaging control and other applications. To find natural frequencies and corresponding shapes we need to solve the GEP for the model (

1)-(

6). These frequencies are useful in solving frequency-response fluid-structure problem for forced oscillations of the piezobody and some liquid that includes equations (

7)-(

10).

In this research we focus on the discretization of (

1)-(

6) as described in [

4] to obtain the following GEP:

where

is an eigenvalue,

v is an eigenvector. The stiffness matrix

is symmetric quasi-definite (SQD) [

5,

6,

7,

8], and the mass matrix

is symmetric positive semidefinite. In (

11) neither

nor

is positive definite, but real scalars

a and

b are exactly known such that

is positive definite (e.g.,

) and we have a symmetric definite pencil [

2,

3]. Then, the simultaneous diagonalization of two matrices of the pencil by a congruent transformation is possible [

2]. Note that the eigenvalues sensitivity depends on the condition number of the diagonalizing matrix. Both matrices in (

11) are large and sparse and the structure of

and

is following:

where

,

and

are symmetric positive definite matrices (SPD). The properties of the SQD matrices established in [

5,

6,

8], namely, SQD-matrix is square, symmetric, indefinite, nonsingular, and the inverse matrix is also SQD. In

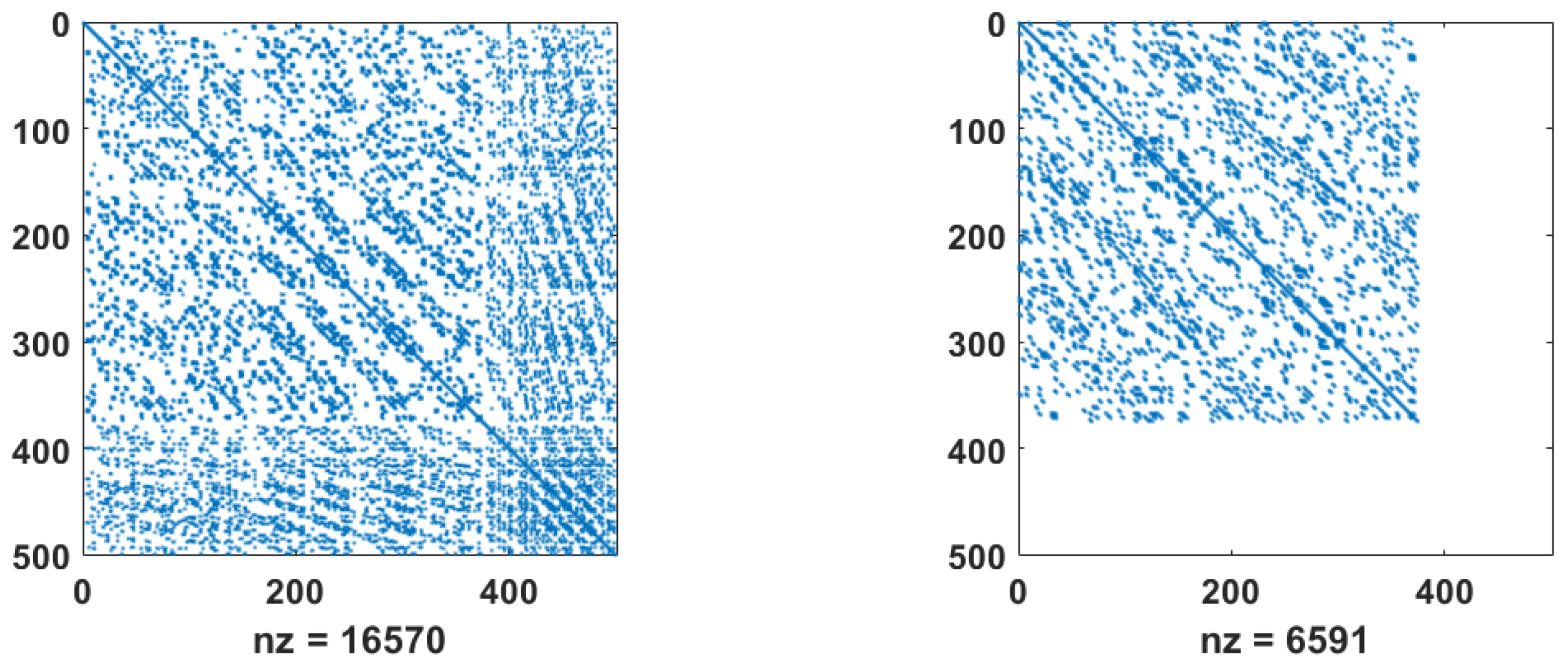

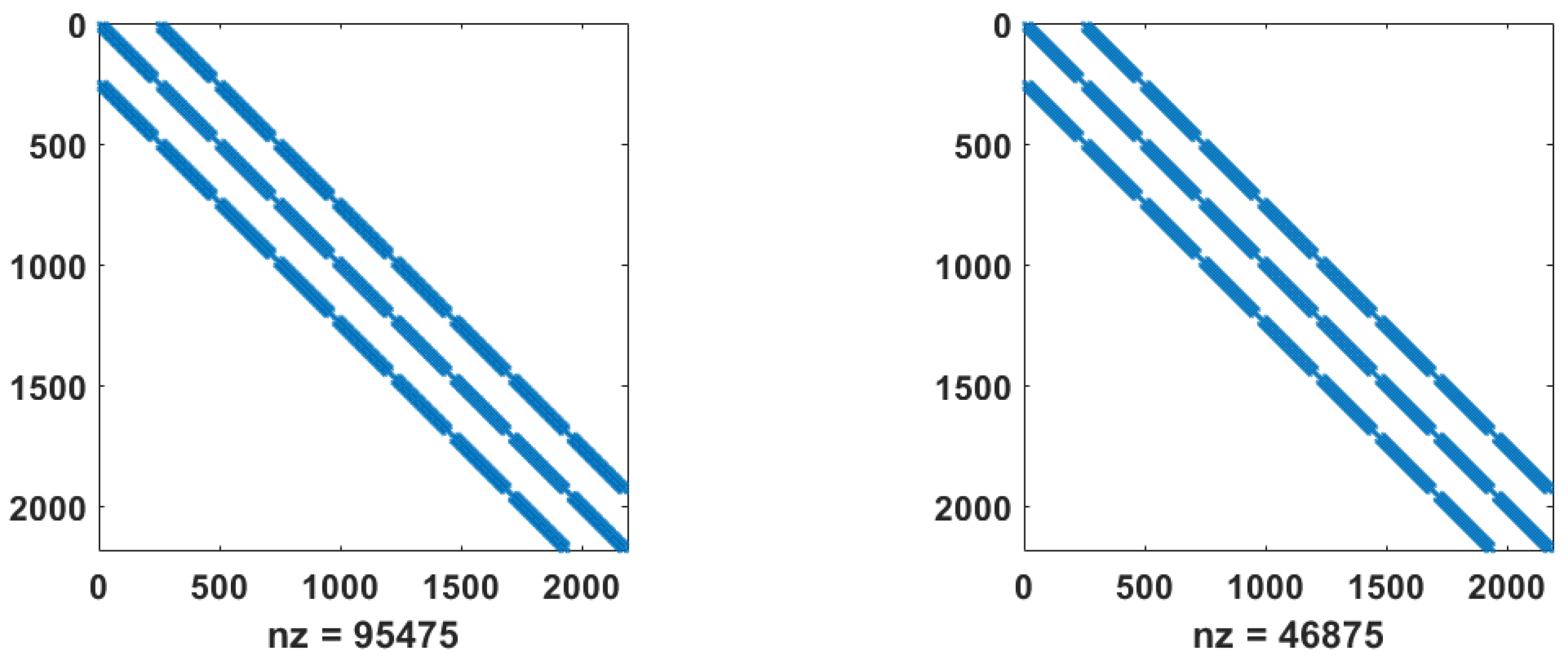

Figure 1 the structure of the stiffness and the mass matrices is shown.

The SLAEs with SQD-matrices also appear in the mixed finite-element approximation to the globally stabilized Stokes problem in weak form. After discretization with

triangular elements and continuous linear pressure, we obtain the SQD-system, where

E is the gradient matrix,

is the divergence matrix,

P is the vector-Laplacian matrix and

R represents the stabilization term [

8,

9]. If

then a saddle point linear system appears which is solved in hydrodynamic problems of a viscous incompressible fluid, in particular, when solving the Navier-Stokes equations [

10,

11,

12]. "Discretization of the Oseen problem using, e.g., finite differences or finite elements results in a generalized saddle point system. Algorithms for solving both standard and generalized eigenvalue problems for saddle point matrices have been studied in the literature, particularly for investigating the stability of incompressible flows and in electromagnetism" [

10] and references there.

The purpose of the research is to evaluate the performance of the Shift-and-Invert (SI) Lanczos method [

1,

3,

13,

14,

15] for the GEP (

11) with different ways of the SLAE solving. All eigenvalues

of (

11) are real and positive but some of them are infinite [

1,

3]. In [

1] it is shown that the Lanczos algorithm can be run directly on the pencil

if

and certain SLAEs with

can be solved. To improve the convergence rate we should use a spectral transformation [

3,

14,

15].

Denote

the rank of

and then the spectrum of (

11) has

r finite eigenvalues

, the remaining

eigenvalues being at infinity

. The eigenvectors

related with the eigenvalues at infinity are such that

. The eigenvectors corresponding to the finite eigenvalues can be

-orthonormalized, i.e.,

, where

is the Kronecker delta.

Circumscribing of the SI Lanczos algorithm can be found in [

3,

14,

15]. Let is choose a scalar

, not equal to any eigenvalue, and we seek a few eigenvalues

closest to

. Then (

11) is changed into

where

is identity matrix,

.

Let

Lanczos algorithm with an initial vector

b constructs a matrix

whose columns form the

-orthonormal basis for the Krylov subspace

[

1]. For

there is a three-term recurrence [

3]

where

,

, and

, when

is such that

. We can rewrite (

13) as

where

is the

mth unit vector,

and

is tridiagonal matrix with

along the diagonal, and

along the subdiagonal and superdiagonal. The

orthogonal projection of the eigenvalue problem

on the range of

gives the solution

with

,

and the residual is

[

2,

3,

15].

The matrix

in (

13) is not calculated. Instead, the SLAE with

is solved each time a matrix needs to be multiplied by a vector. To compute the eigenvectors it is necessary to store all calculated Lanczos vectors. This requires a large amount of memory and it cannot be determined in advance, since the number of iterations is unknown. To solve this problem, restarting version of the Lanczos method is used [

3]. Moreover, when solving a problem with a singular mass matrix, it is necessary to choose the initial vector in a special way. The Lanczos and the Ritz vectors have components in the nullspace of the mass matrix and its magnitude can increase during iterations. To solve this problem the starting vector must be placed in the proper subspace [

15].

Let

and

be the minimum and the maximum of the finite eigenvalues of (

11), and

When

then the matrix

is SQD, if

then this matrix is indefinite because the positive definiteness of the (1,1) block

is lost. When

it has only one positive eigenvalue, the rest are negative, and when

the matrix

becomes negative definite. A matrix type knowledge is fundamental when choosing a SLAE solver. Since in practice the lower part of the GEP spectrum is of interest (usually several smallest eigenvalues), we assume that it is necessary to solve a SLAE with SQD (e.g., with

) or indefinite matrices.

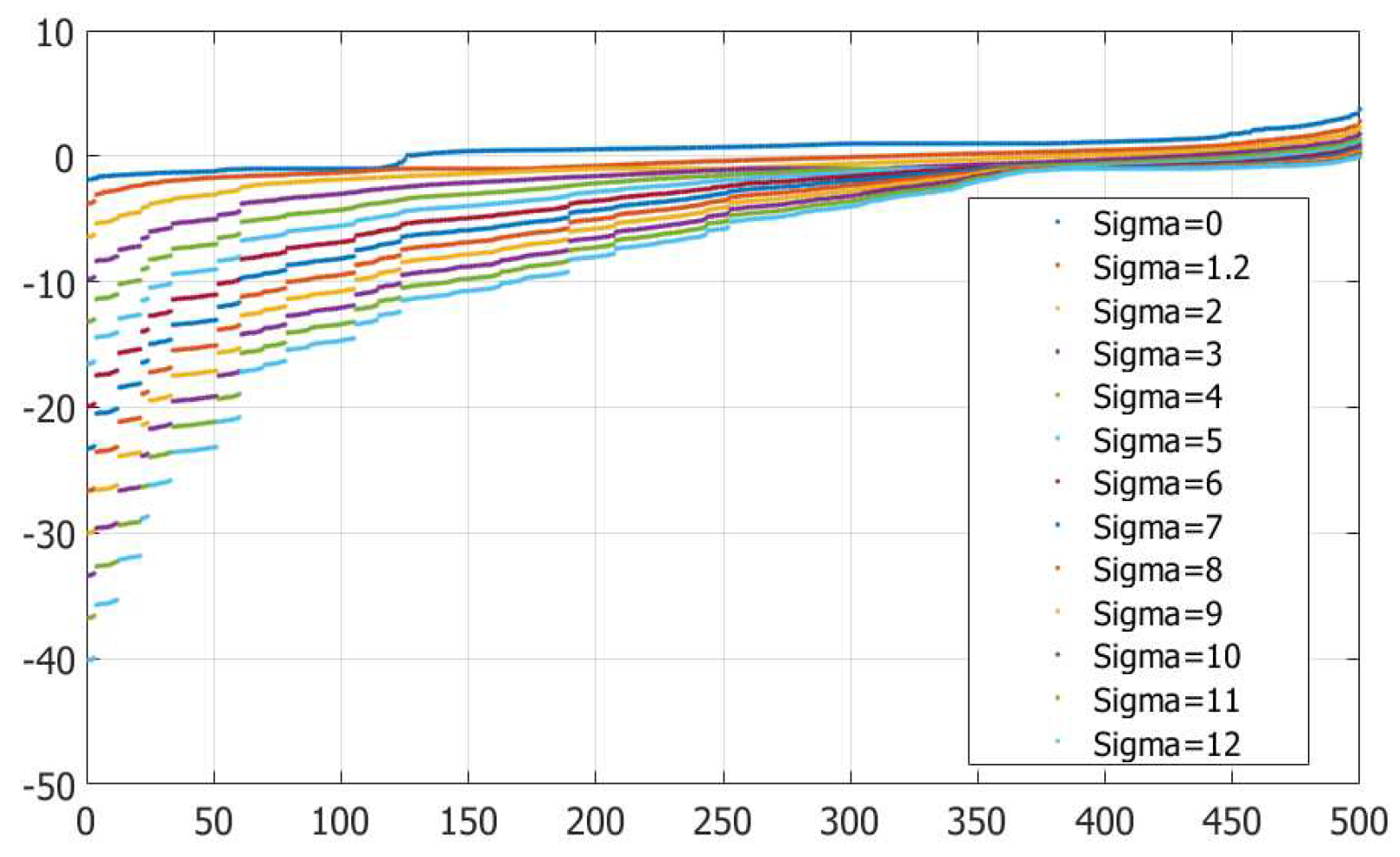

Figure 2 shows spectrum of the matrix

depending on the

value.

Often in the literature [

2,

16] etc., a direct method for solving SLAE is used based on matrix factorization. It is known [

5,

16] that SQD-matrix is strictly factorizable, i.e., for any permutation matrix

, there exists a lower triangular matrix

L (with unit diagonal) and a diagonal matrix

D (generally indefinite) such that

. In [

16] stability results for

factorization of SQD matrices have been provided. But when using the Cholesky decomposition, the main problem is the absence of an ordered structure of the matrices

in the presence of strong sparseness, i.e., the predominant number of the zero elements. Moreover, our computations showed that factor

L becomes completely fill-in and for large problems such factorization is too expensive or completely impossible.

An another approach is the iterative SLAE solving. These systems do not necessarily need to be solved very accurately. There are some strategies for choosing accuracy for SLAE solving, e.g., [

17]. Sometimes, as the number of SI Lanczos iterations increases, these systems can be solved less accurately. On the other side, outer iterations can slow down if inner steps are not enough. Since

is SQD or indefinite matrix, several approaches can be used to solve the SLAE with it.

Iterative method for indefinite SLAE: SYMMLQ, MINRES [

18], MINRES-QLP [

19], etc.

Transition from SLAE with SQD matrix to the equation system with a block non-symmetric positive definite matrix

Reducing the SLAE dimension using Schur’s complement and/or preconditioning of the inner iterative solver

Solving the SLAE with block-banded matrix that has an ordered structure and obtained by different nodes numbering

Let us consider each of these approaches.

We implement the methods and consider its robustness. The computations for the model matrix pencil

are performed with MATLAB (R2019a). Because we do not know the exact solution of (

11), at first, we compared the computed Ritz values with the eigenvalues obtained by MATLAB’s built-in solver EIGS.m for the sparse GEP. For the non-zero

matrix block

in (

12) we have

, i.e., the model pencil has 375 positive real finite eigenvalues. To control convergence in the SI Lanczos algorithm, we check for the residual norm

which is cheaply computed [

2,

3]. We use full reorthogonalization of the Lanczos vectors to obtain the best eigenvalues accuracy. In practice, the residuals become small without this procedure, but the accuracy of the computations will be worse. QR-algorithm is used to calculate the Ritz values of the tridiagonal matrix.

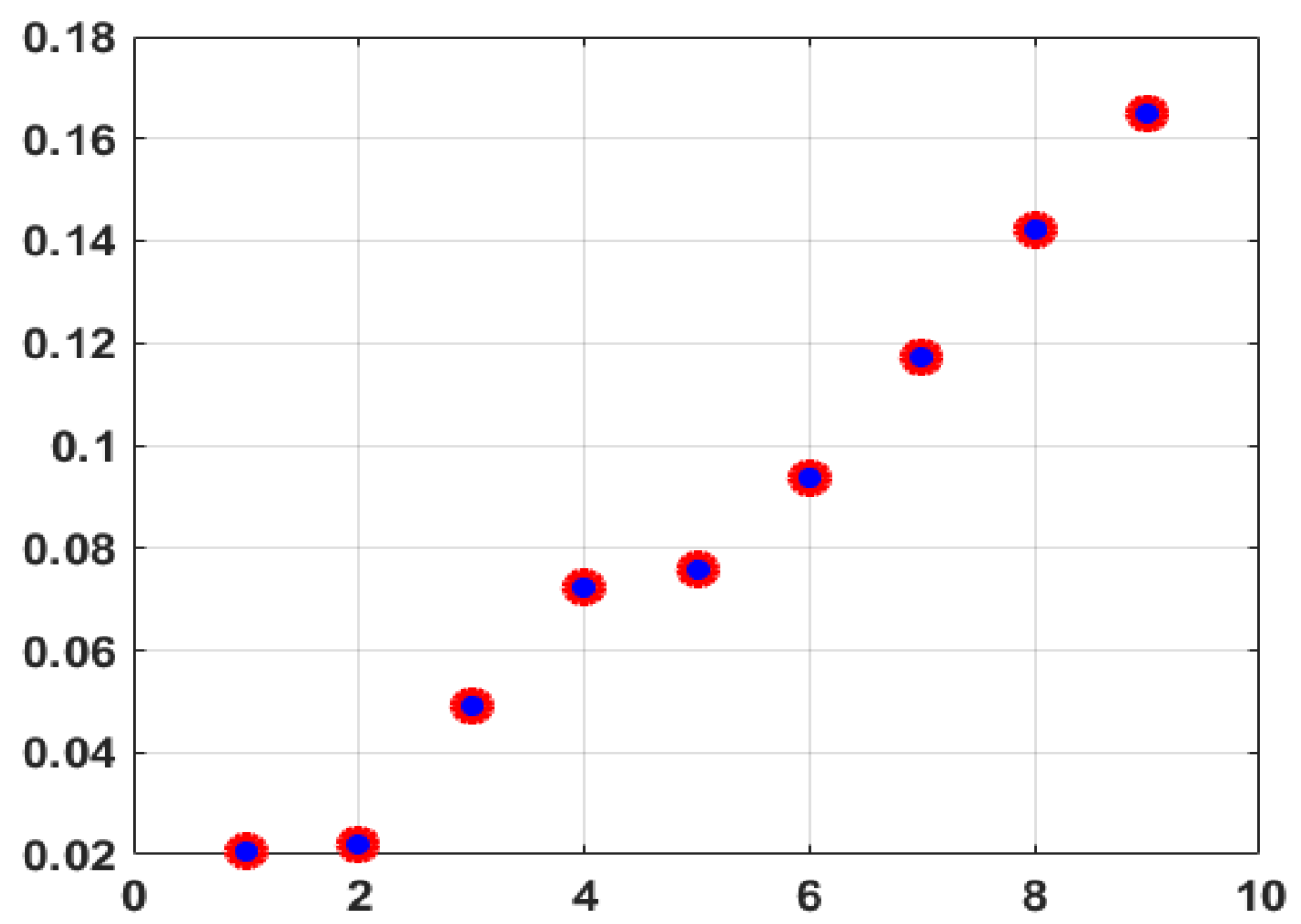

In

Figure 3 we show 9 eigenvalues closest to zero, obtained by the SI Lanczos method with the SYMMLQ [

18] SLAE solver. The accuracy of the computed eigenvalues is high, since the desired ones are well separated from the rest of the spectrum. Here

m is the Krylov subspace dimension.

3. Schur complement reduction

Let us rewrite GEP (

11)

in the

block form

where

Let

is the Schur complement of the block

R in the matrix

(denoted

), then we obtain the smaller size GEP

containing only SPD matrices

and

. The matrix

S is SPD by virtue of Sylvester’s law of inertia [

1] and

One of the most costly operations in the formation of the Schur complement is the inversion of R. Usually, methods for finding the inverse matrix are poorly parallelizable direct methods, e.g., the inversion method based on -decomposition. In the mesh issues arising from discretizations of boundary value problems in mathematical physics usually looking for efficient approximations for S since the computation of the exact one is too time-consuming.

Since the both matrices in (

16) are SPD ones, the Lanczos method without shift and inversion can be used. It finds the eigenvalues of the symmetric GEP (

16) by a Rayleigh-Ritz procedure [

1,

2,

3]

The action of

S on the column vectors

y can be computed by means of matrix-vector products with matrices

,

E,

P and by solving a linear system with matrix

R [

10]

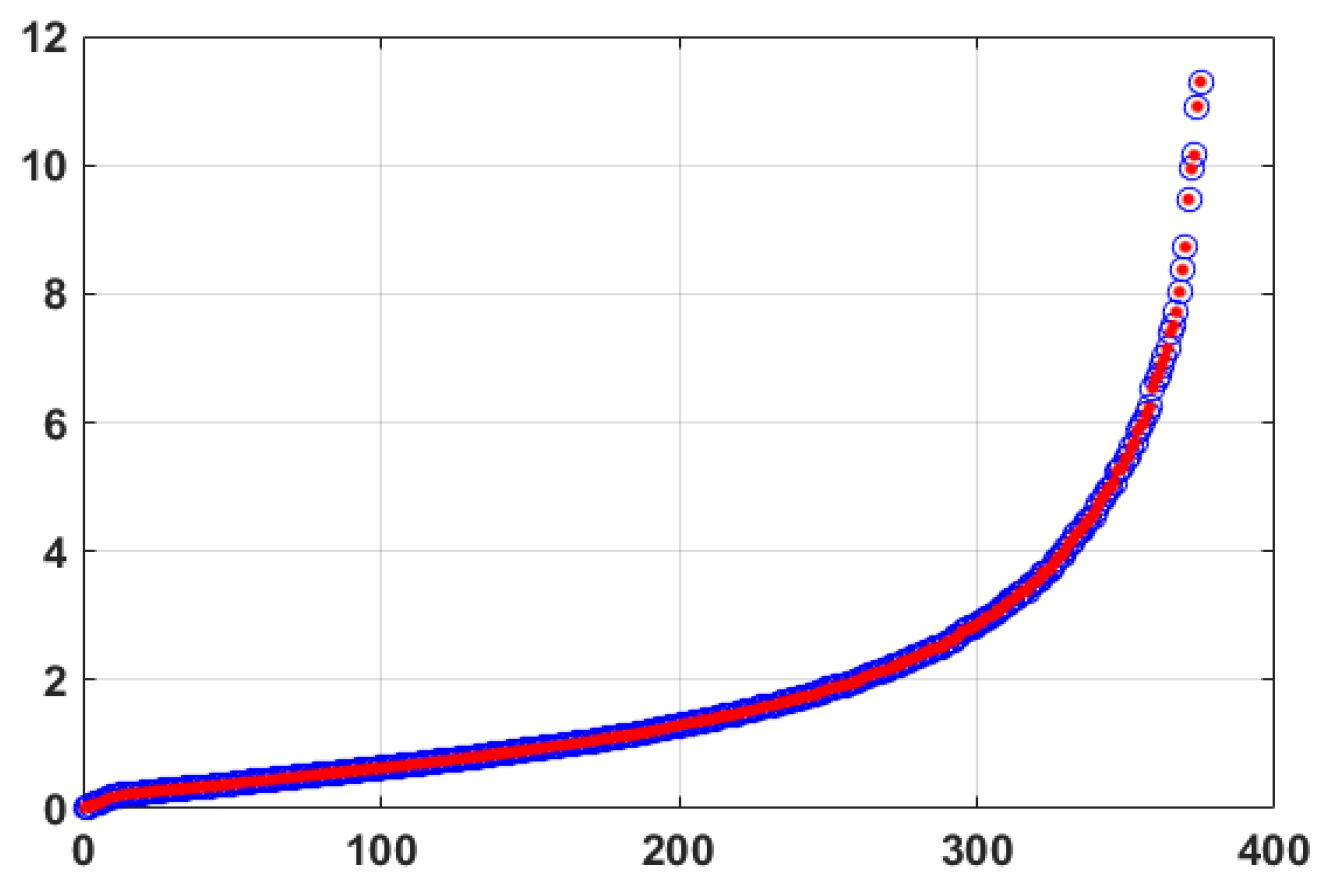

To control the robustness of the Lanczos method without spectral transformation, we check the coincidence of the Ritz values with the eigenvalues along the entire spectrum in

Figure 4.

Nevertheless, the SI Lanczos method with the inner preconditioned solver can also be used. The Schur-complement equation is

Since we are interested in several smallest eigenvalues closest to zero, we can put

. Then (

18) takes a more simple form

We have to apply a method which requires only matrix-vector multiplications by

S in addition to inner products and operations like "saxpy" (adding a multiple of one vector to another), e.g., the Conjugate Gradient Method (CGM) [

1,

2,

29].

In [

8] it was noted that

where

is SPD matrix, and

In (

15)

P and

R are easily invertible (i.e., the SLAE with these matrices can be easily solved). The convergence rate of the CGM is usually improved by a suitable preconditioner.

RESULT [

8] "The generalized CRAIG [

30] method iterates

are related to the iterates

of the CGM applied to equation

with preconditioner

P, according to

"

The Craig’s method is actually a reorganized CGM applied to the normal equations (CGNE [

29]). Denote

Then we can rewrite (

19) as

It is obvious that (

20) is the preconditioned SLAE

where

,

and

. The matrix

P is the preconditioner which is introduced implicitly. The matrices

and

are similar, therefore they have the same spectrums.

RESULT [

7] "The extended CRAIG iterates

are related to the CGM iterates for the problem

according to

"

Here

is an auxiliary variables,

is the regularization parameter equal to one in (

20). The Preconditioned CGNE (PCGNE) method was given in [

29]. At each step of this algorithm, it is necessary to solve the SLAE with matrix

P to find the current value of the residual and compute the matrix-vector product with matrix

S. We take termination criterion for the Schur-complement equation (

19) as

, where

is the residual at

k-iteration. An alternative approach is to limit iterative method to a fixed number of inner steps, but this may negatively affect the convergence rate of the outer iterations. Numerical results for the smallest

closest to zero, the corresponding Ritz value

and the modulo differences

for the moderate-dimension matrices are given in

Table 2. Here

n is the block-structured matrices dimension in (

15) and "IT" is a number of PCGNE iterations.

As the size of the matrices increases, the number of inner PCGNE iterations also increases and the accuracy of the computed Ritz values deteriorates somewhat. It turns out to be worse than the previously obtained accuracy by the iterative PSTS method. This is a consequence of using the method for the normal equations. Note that in [

31] preconditioned Lanczos algorithm had an eigenvalue problem in the inner loop instead of a linear equations problem. The SI Lanczos method with the inner preconditioned CG iterations was taken for comparison of the numerical results in this research.

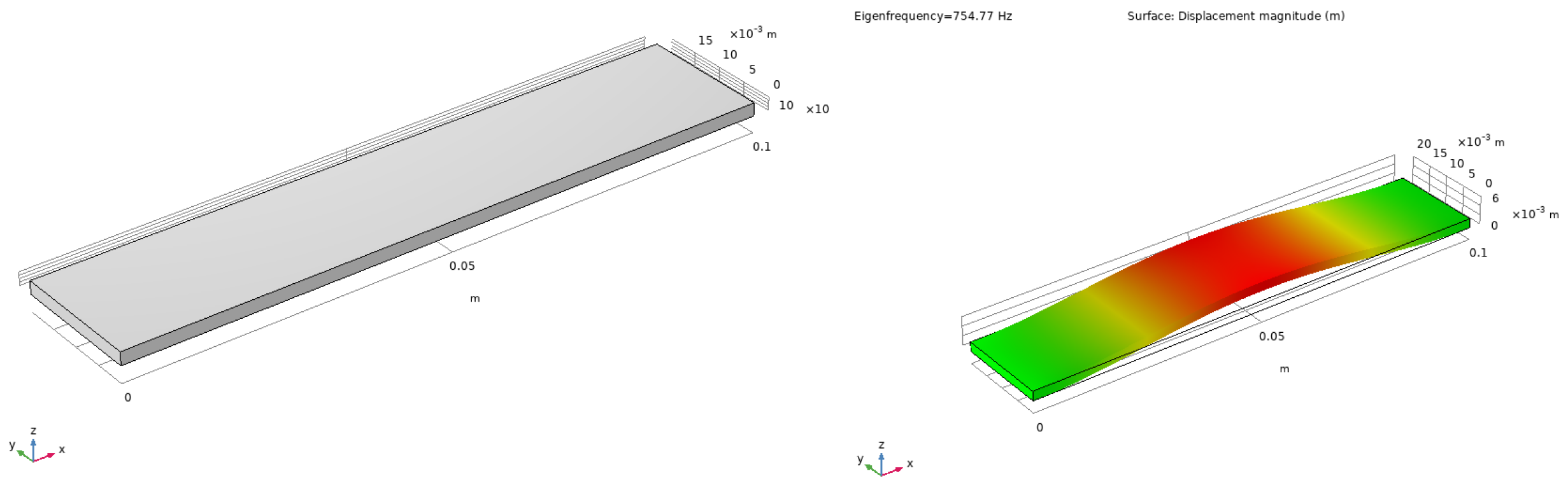

5. Program implementation in ACELAN-COMPOS package

For the purpose of demonstrating the implemented modules, we show a test model of piezodevice. Let us consider a model of piezo-active transducer shown in

Figure 6 that is working in the acoustic liquid.

The transducer is 10 cm long, 2 cm wide and 2 mm thick. Short sides are fixed. Such device can be used for emitting waves in the liquid in actuator mode or as a sensor, producing energy from periodical mechanical load. Oscillations will be forced by the difference of potentials on electrodes placed on the top and on the bottom parts of the device.

For the purpose of measuring the performance of the developed algorithms, we will proceed with a 3D model of the device, even it is possible to solve presented problem in the plane form. Initial geometry, meshing and reference studies for a presented model were performed in COMSOL Multiphysics package [

35] .

We implemented computational modules for described as part of ACELAN-COMPOS package [

4]. This software is used for general finite element computations, but focuses on modeling composite materials with coupled fields. The package is based on a class library written in C# language. The process of solving the Eigenvalue problem consists of three main stages: assembling sparse matrices, performing operations with assembled matrices and post-processing results to obtain final values.

The first stage takes an input as combination of geometry as a mesh, problems statement that includes an element implementation, materials and boundary condition. For each volume in a mesh corresponding local matrix should be computed. If two elements have the same geometry and material properties and the only difference between them is a position in the geometry, their local matrices are identical. The mesh that consists of such element is called a regular mesh. In this case, the caching and re-using of once computed local matrices can reduce the computational time. If the shape of analyzed body allows to build a quad mesh and sweep for the whole body, the quasi regular mesh can be used in the same manner. For majority of shapes tetrahedral meshes are used, and this technique is not possible, and for this case the simple parallelization can be used to build local matrices effectively. The next step is to transfer value from local matrix to global. Since the finite element method produces sparse matrices, the underlying data structure becomes the bottleneck for matrix operations. It is crucial for Lanczos method implementation to have fast and reliable matrix-vector multiplication operation. Some sparse data formats are more effective for reading and setting values by coordinates, other are optimized for multiplication [

33]. ACELAN-COMPOS package supports multiple formats, and usually the assembling and further matrix operations are performed with two different data structures: assembling process is faster for hash-table based structures, and further computing is more effective for compressed rows or columns formats.

The structure of a geometry mesh is important for the output matrix. Each column and row represents a single nodal degree of freedom. If the three dimensional mechanical problem is considered, each node with be represented as 3 rows and columns, these rows usually numbered sequentially, for node with index i these rows will be numbered . Lets consider a different node with index j. If there is an element that includes nodes i and j, in row values at columns will be filled. Some formats, like SKS (Skyline Storage), based on filling the whole section of the matrix row from the first non-zero value to the last. For that reason the indexing of nodes is important for both the size of data structure and the speed of computation. There are multiple methods for compressing the structure by re-enumerating nodes, but for quasi regular mesh trivial coordinate sorting allows to achieve the most effective structure. Another option to be considered is the sorting of degrees of freedom in the node. If piezomaterial is considered, mechanical and electrical unknowns can be grouped on node level or on the whole global matrix level.

The second stage is based on the matrix-vector and matrix-matrix multiplication. ACELAN-COMPOS package can be executed on different platforms and hardware. The client version of the package is intended to be used on consumer grade computers and laptops. For such devices limited amount of RAM should be considered, but multi-core processors (Intel Core and AMD Ryzen) series allow to perform basic parallelization. The server version usually runs on hardware with extended amount of RAM and multi-core server processors (Intel Xeon series). Such setups perform worse that consumers hardware in single-core scenarios, but since amount of memory allows to solve multiple problems simultaneously, multi-level of parallelization can be utilized. In this paper we also consider an effective processors (AMD Threadripper Series) with high single core speeds and multiple thread possibilities. We compared basic computational operations for sparse matrices on all three described setups, with underlying structures and methods implemented in CSPARSE [

34] with bindings for un-managed code and native C# implementation.

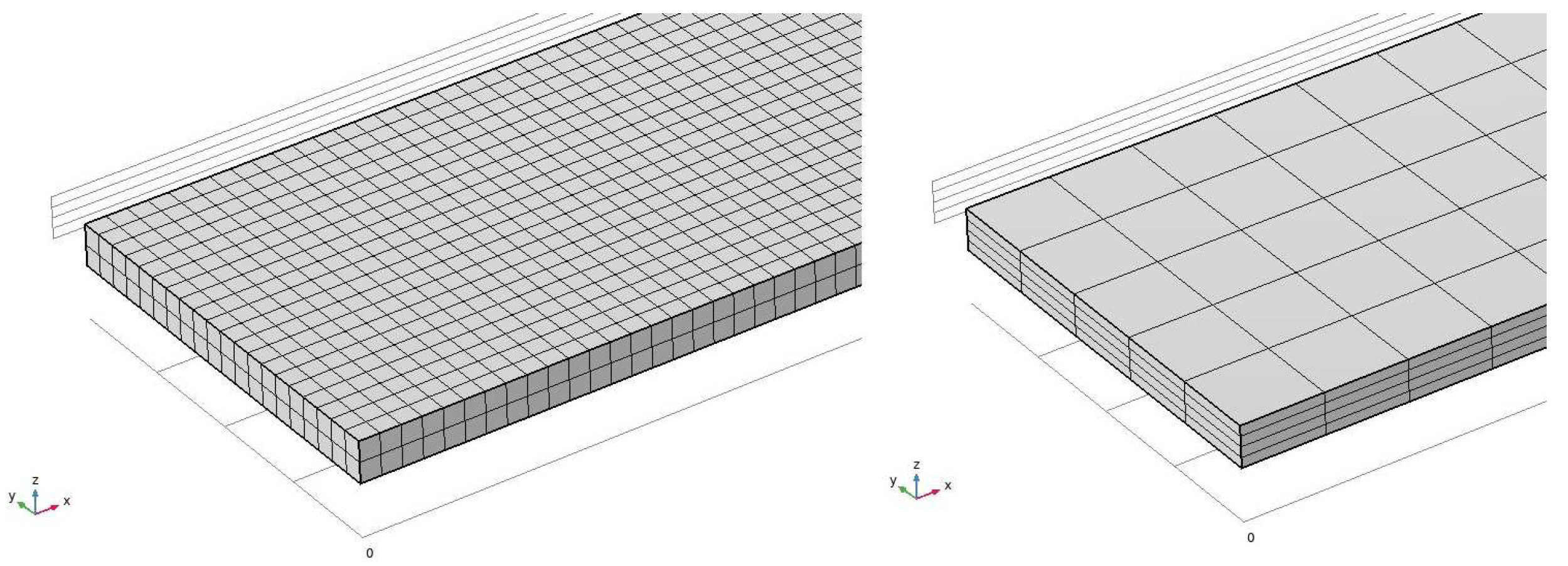

For a model presented in

Figure 6 rough or fine mesh can be suggested. Since measurements of the device are significantly different, we performed numerical experiments with three meshes: two regular with cubic elements (named A and B) and optimized mesh of hexagons (named C) as shown in

Figure 7. The difference in obtained eigenvalues between meshes was below 2%.

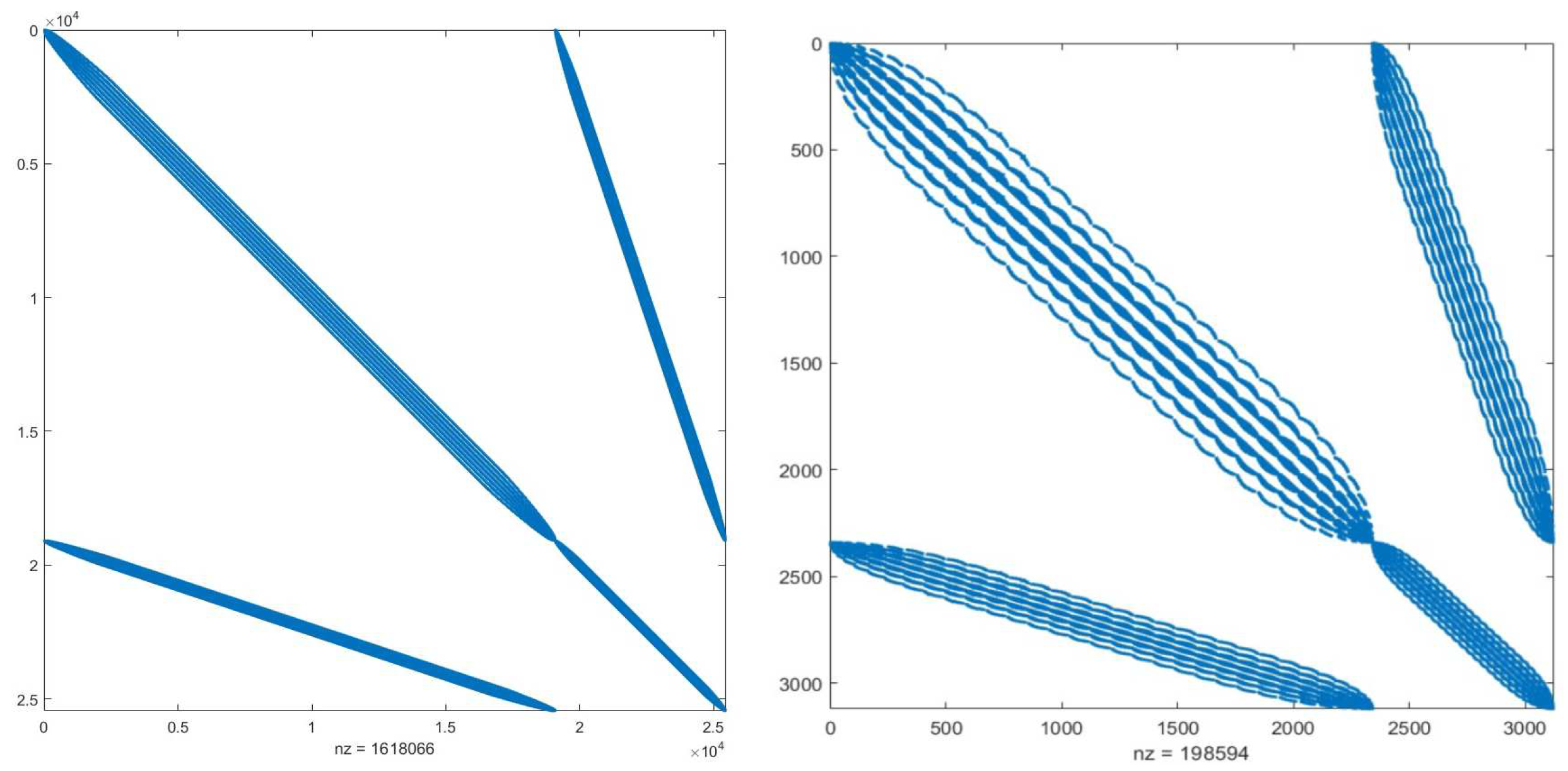

Computations were performed for two basic operations: assembling of global matrices, including loading mesh into memory and all needed operations with data formats, and matrix-vector multiplication for a sparse stiffness matrix (

Figure 8) and random vector. Matrix-vector multiplication was performed on single core. Meshes were imported into the ACELAN-COMPOS package as .nas files. Boundary conditions were re-applied. Numerical results obtained on generic consumer laptop (AMD Ryzen 7 4800H CPU, 32 Gb RAM) are presented in

Table 5.

Computations were also performed on different workstations. Without parallelization, professional PCs (AMD Threadripper PRO 3995 WX) outperform consumers PC by 3-5%. Parallelization with built-in C# tools allows to speed computation up by 40-45% for consumer PC and up to 55% on professional PCs, depending on available RAM.