Submitted:

16 November 2023

Posted:

16 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Xihu Longjing Tea Processing Method

2.2. Sample Preparation and Extraction

2.4. Waters Q-EXACTIVE Plus/Dionex U3000 UHPLC

2.5. Data Preprocessing and Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Metabolite Profifiling Analysis

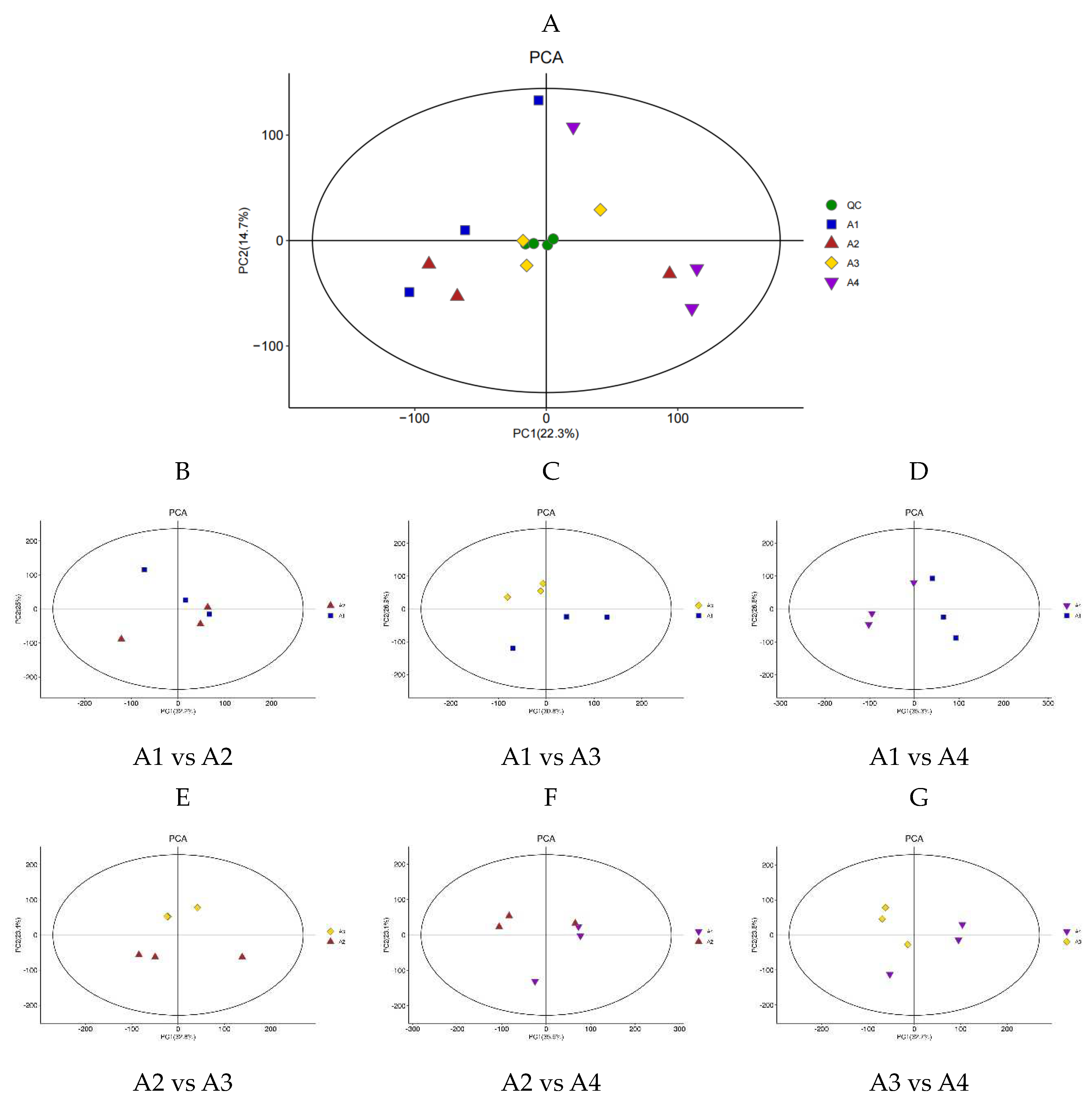

3.2. Differential Metabolite Analysis Based on PCA

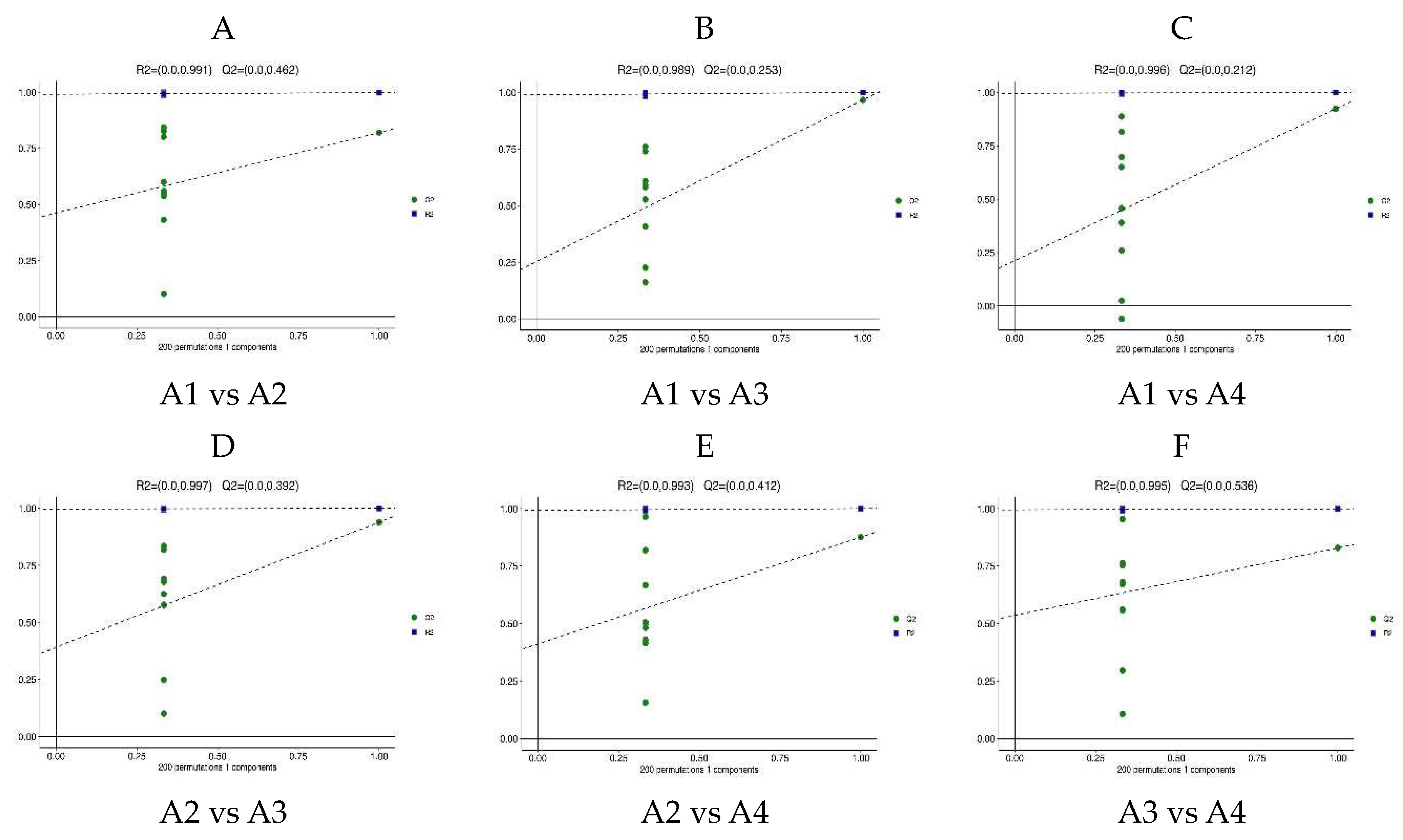

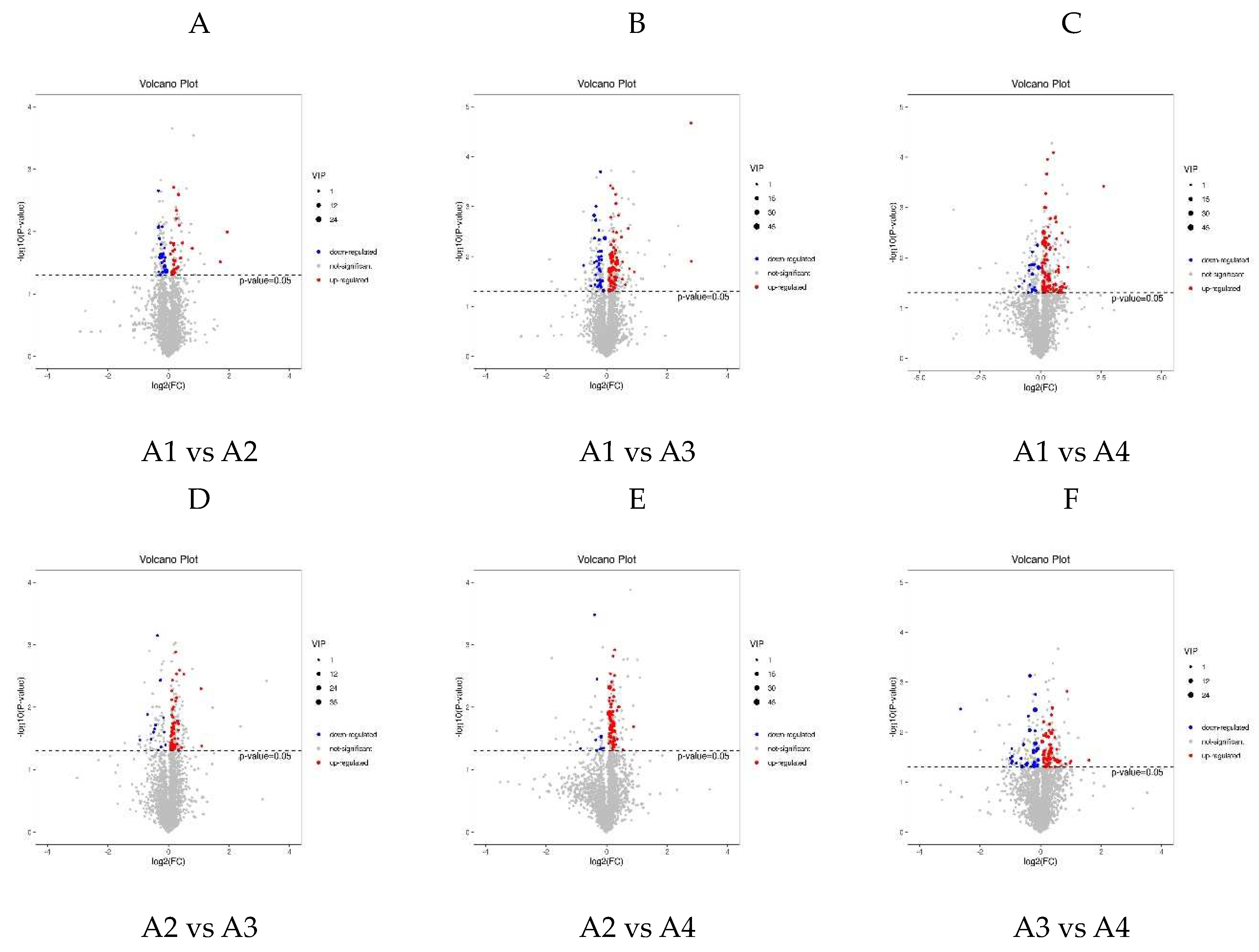

3.3. Differential Metabolite Analysis via OPLS-DA

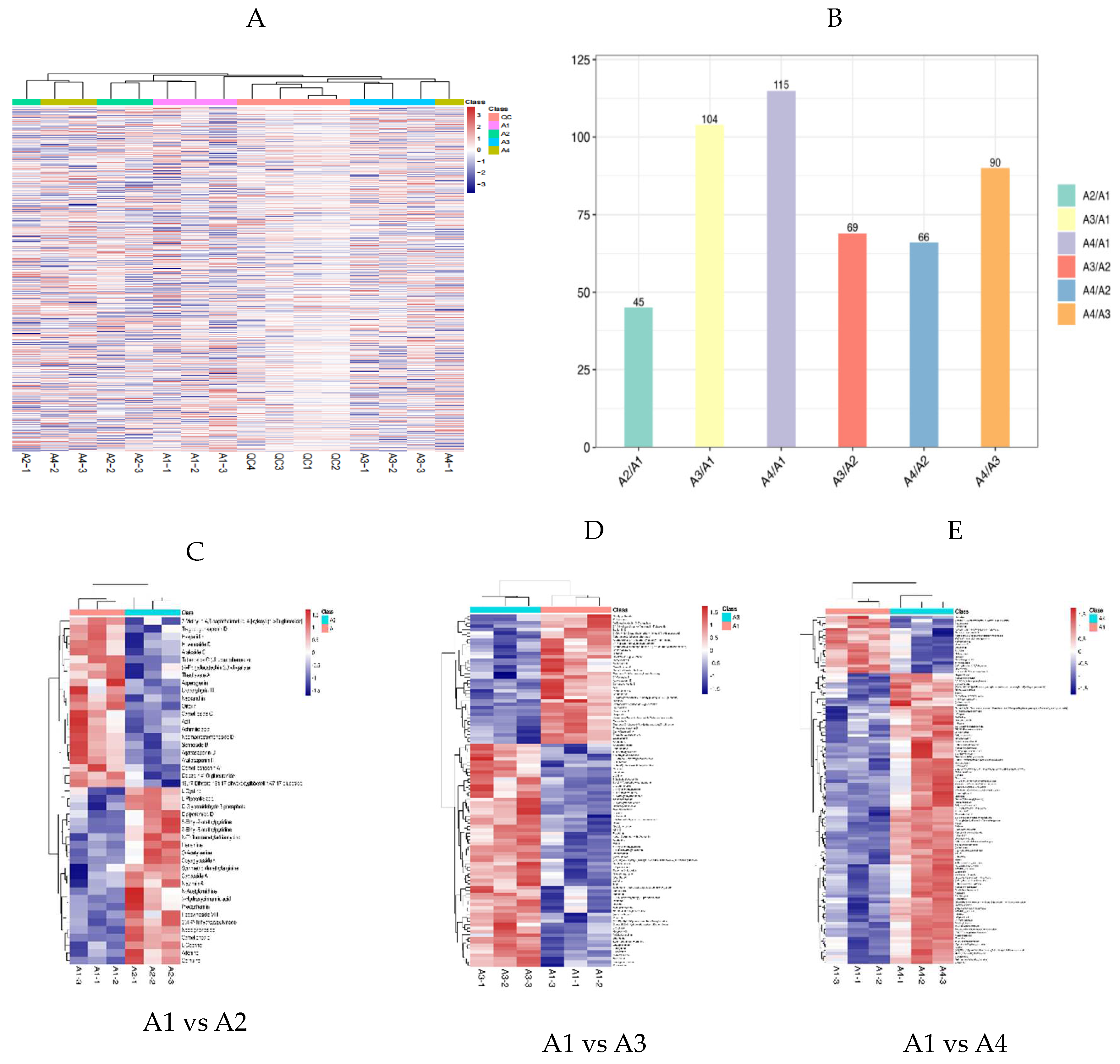

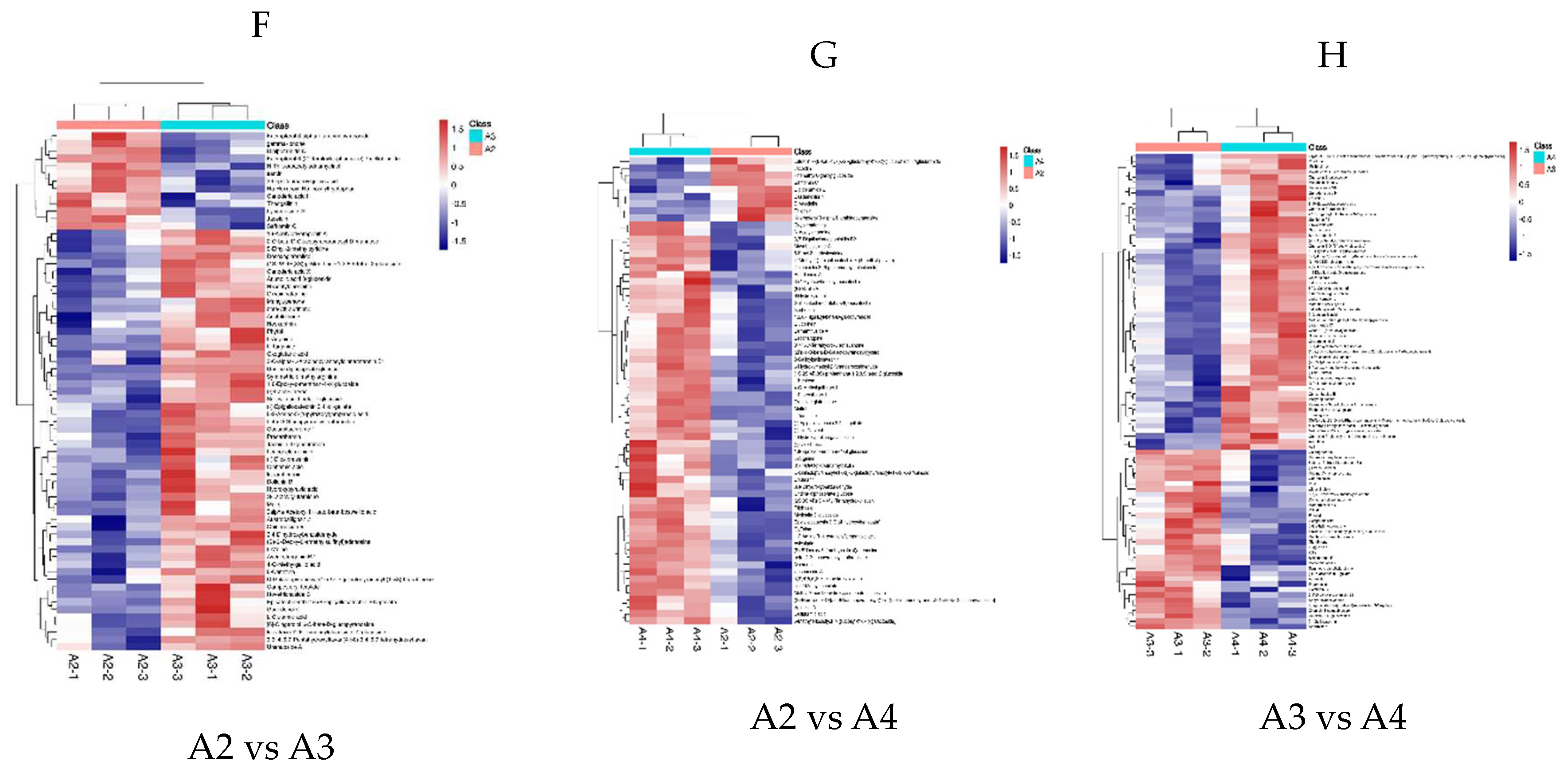

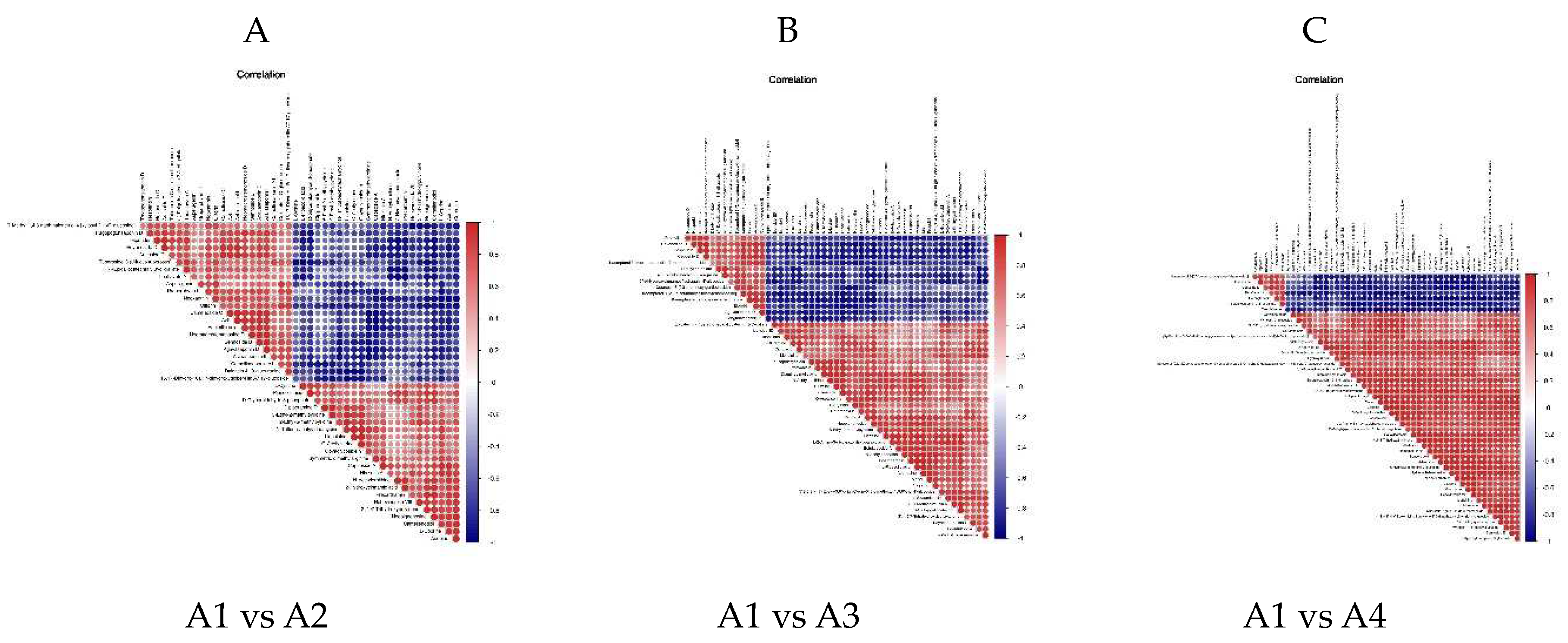

3.4. Differential Metabolite Association HEATMAP

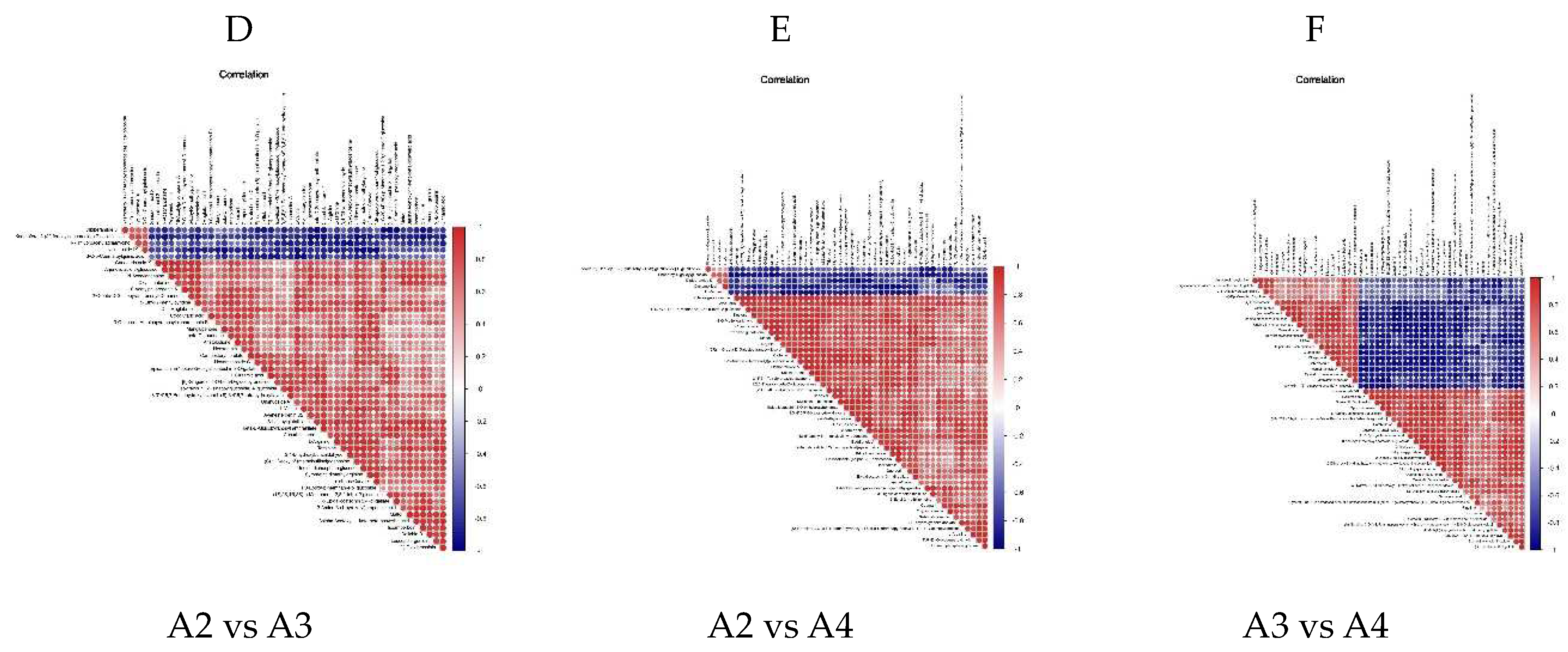

3.5. Differential Metabolic Pathways among the Xihu Longjing Tea Processing Samples

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, J. Y., Feng, X. N., Lyu, C., Zhou, S., Liu, Z. X. Effects of different processing methods on the lipid composition of hazelnut oil: a lipidomics analysis. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2022, 11: 427-435. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. Q., Yang, X. T., Wang, H. L., Yang. X. F., Su, X. Q., Kong, J. H., Cheng, Y. L., Yao, W. R., Qian, H. Study on the establishment of quality discrimination model of Longjing 43 green tea (Camellia sinensis(L.) Kuntze). J APPL RES MED AROMA 2022, 31: 100389-100396. [CrossRef]

- Gong, S. Y., Mao, Z. F., Lu, D. B., Zhang, Y. B., Qian, X. D., et al. Effect of processing technology on quality of spring (high-grade) longjing tea. China Tea 2011, 12: 8-11.

- Shen, H. Effects of different processing methods on the quality of high-grade WestLake Longjing tea-comparison from sensory evaluation results. Tea Proc. in China 2010, 3:33-35.

- Wang, H., Gong, S. Y, Wei, M. X., et al. Effects of tea varieties and processing technology on the quality of changxing bamboo shoot tea. Chinese Tea 2014, 3:18-21.

- Zhang, C, Claire, L., Chao, Y., et al. Antioxidant capacity and major polyphenol composition of teas as affected by geographical location, plantation elevation and leaf grade.Food Chem. 2018, 244:109-119.

- Wang, L. Y., Wei, K., Cheng, H., et al.Geographical tracing of Xihu Longjing tea using high performance liquid chromatography. Food Chem. 2014, 146:98-103. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J., Shao, Z. Q., Chang, L. M. Discussion on the processing technology of Longjing tea automatic continuous production line with different defoliation methods . Tea, 2017, 43(3) :157-160.

- Xia, J. R., Xu, L. Y., Yang, Q., et al. Analysis of Longjing tea mechanism technology. Tea Proc. in China, 2016, 1: 20-23.

- Jiang, B. F. Research and application of new semi-continuous processing technology of Longjing tea. Agri. Sci. and Tech. in Shanghai 2016, 2:21-22.

- Shi, D. L, Lu, D. B., Jin, J. Small-scale processing mode and technology integration of Longjing tea. Chinese Tea 2015, 5: 21-22.

- Chen, F, Zou, X. W. A brief analysis of the reasons for the formation of the quality of West Lake Longjing tea. Tea Proc. in China 2011, 3: 22,27-30.

- Wang, D. B. Xu, J., Ru, L. J., et al. Reasons for quality defects of longjing tea and improvement methods. Chinese Tea 2019, 3:46-48.

- Shi, D. L, Yu, J. Z., Liu, X, H., et al. Study on the effect of different technology and different pot method on the quality of longjing tea. J. Southwest Normal University (natural science edition) 2010, 35(5):173-177.

- Kang, M. L., Xue, X. C., Ling, J. G. Optimization of processing parameters of longjing tea with summer and autumn tea. Sci. and tech. in the Food Industry 2007, 28(12):145-147.

- Ge, Y. T., Sheng, L. F., Gao, L. H., et al. Identification of key control points in Longjing tea mechanism process based on leaf temperature monitoring. Zhejiang Agri. Sci. 2019, 60(3): 425-426, 436.

- Han, Y. C., Chen, H. J., Gao, H. Y., et al. Effect of soaking conditions on antioxidant properties of West Lake Longjing and correlation analysis. Chinese Journal of Food 2018,18(10):128-136.

- Yin. J. F., Xu, Y. Q., Chen, G. S., et al. Effects of different types of drinking water on flavor and main quality components of WestLake Longjing tea. Chinese Tea 2018, 5:21-26.

- Chen, Q., Zhao, J., Guo, Z., et al. Determination of caffeine content and main catechins contents in green tea (Camellia sinensis L.) using taste sensor tech nique and multivariate calibration. J FOOD COMPOS ANAL 2010, 23(4): 353-358. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. , Zhao, J., & Vittayapadung, S. Identification of the green tea grade level using electronic tongue and pattern recognition. FOOD RES INT 2008, 41(5): 500-504. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. J.,Kan, Z. P., Henry, J. T., Ling, T. J., Ho, C. T., Li, D. Y., Wan, X. C. Impact of Six Typical Processing Methods on the Chemical Composition of Tea Leaves Using a Single Camellia sinensis Cultivar, Longjing 43. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 5423−5436. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Dai, W.; Lu, M.; Xie, D.; Tan, J.; Yang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Lv, H.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, L.; Ni, D.; Lin, Z. Metabolomic analysis reveals the composition differences in 13 Chinese tea cultivars of different manufacturing suitabilities. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 1153− 1161. [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Xie, D.; Lu, M.; Li, P.; Lv, H.; Yang, C.; Peng, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, J.; Lin, Z. Characterization of white tea metabolome: Comparison against green and black tea by a nontargeted metabolomics approach. Food Res. Int. 2017, 96, 40−45. [CrossRef]

- Davosir, D., Sola, I. Membrane permeabilizers enhance biofortification of Brassica microgreens by interspecific transfer of metabolites from tea (Camellia sinensis). Food Chem. 2023, 420: 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Qi, B. R., Zhang, Y. Y., Ren, D. Y. Fu Brick Tea Alleviates Constipation via Regulating the Aquaporins-Mediated Water Transport System in Association with Gut Microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71(8): 3862-3865. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., & Wei, Z. The classification and prediction of green teas by elector chemical response data extraction and fusion approaches based on the combination of e-nose and e-tongue. RSC ADV 2015, 5(129): 106959–106970.

- Xu, L., Yan, X., et al. Combining Electronic tongue array and chemometrics for discriminating the specific geographical origins of green tea. J ANAL METHODS CHEM 2013, 3: 1-5.

- Yu, P., Yeo, A. S. L., Low, M. Y., et al. Identifying key non-volatile com pounds in ready-to-drink green tea and their impact on taste profile. Food Chem. 2014, 155: 9-16.

- Ma, G., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., et al. Determining the geographical origin of Chinese green tea by linear discriminant analysis of trace metals and rare earth elements: taking Dongting Biluochun as an example. Food Control 2016, 59: 714-720. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. H., Hsieh, C. H., Tsai, S. Y., Wang, C. Y., & Wang, C. C. Anticancer effects of epigallocatechin-3-gallate nanoemulsion on lung cancer cells through the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. SCI REP-UK 2020,10, 5163-5173. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. G., Duan, J. W., Diao, Y. P., Chen, Y. Liang, X. Y., Li, H. Y., et al. ROS-responsive capsules engineered from EGCG-Zinc networks improve therapeutic angiogenesis in mouse limb ischemia. BIOACT MATER 2021,6:1-11. [CrossRef]

- Dai, W. Z., Ruan, C. C., Zhang, Y. M., Wang, J. J., Shao, Z. H., ……, Liang, J. Bioavailability enhancement of EGCG by structural modification and nano delivery: A review.J FUNCT FOODS 2020, 65: 103732-103740.

- Dong, X. W., Tang, Y. M., Zhan, C. D., Wei, G. H. Green tea extract EGCG plays a dual role in Aβ42 protofibril disruption and membrane protection: A molecular dynamic study. CHEM PHYS LIPIDS 2021, 234:105024-105034. [CrossRef]

- Nikoo, M., Regenstein, J. M., Gavlighi, H. A. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) and its potential to preserve the quality and safety of foods. COMPR REV FOOD SCI F 2018,17, 732-753. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. B., Wu, X. J., Chen, X.Y., Guo, R., Kou, Y. X., Li, X. J., …, Wu, Y. Casein-maltodextrin maillard conjugates encapsulation enhances the antioxidative potential of proanthocyanidins: An in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Food Chem. 2021, 346, 128952-128959.

- Wang, Q., Cao, J., Yu, H., Zhang, J. H., Yuan, Y. Q., Shen, X. R., Li, C.The effects of EGCG on the mechanical, bioactivities, cross-linking and release properties of gelatin film. Food Chem. 2019, 271, 204-210.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).