Submitted:

15 November 2023

Posted:

16 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literary review

- a = acceleration rate (m/s²) corresponding to a certain speed v;

- v = vehicle speed (m/s);

- α = acceleration rate (m/s²) at the first instant of the period considered;

- β = rate of change of acceleration with respect to speed (s−1);

- G₁ = grade of minor road, positive if upgrade and negative if downgrade (m/m);

- g = gravity acceleration (9.80665 m/s²).

2. Materials and Methods

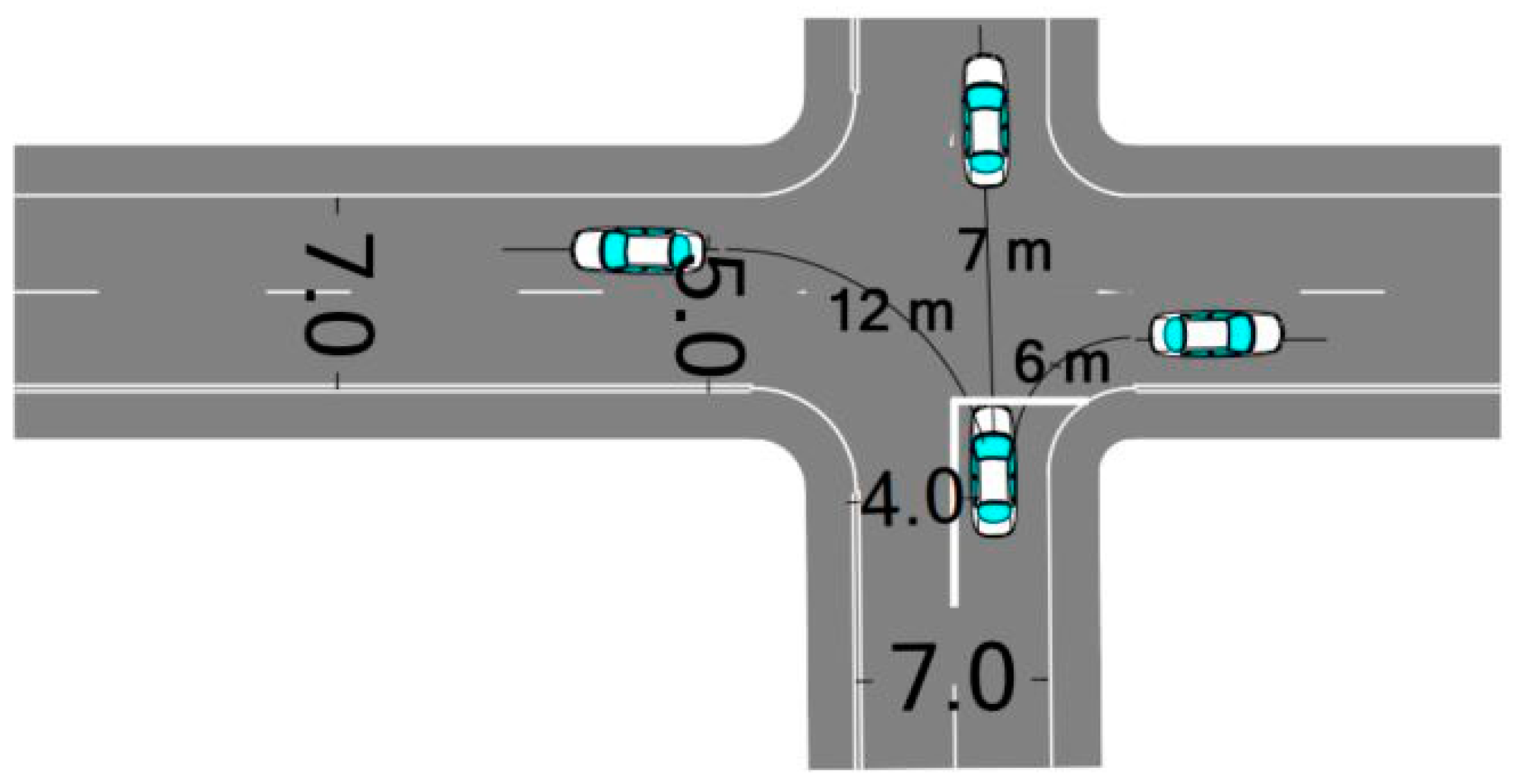

- Acceleration rates are measured using various cars;

- Testing sites are flat areas with asphalt floor in dry condition;

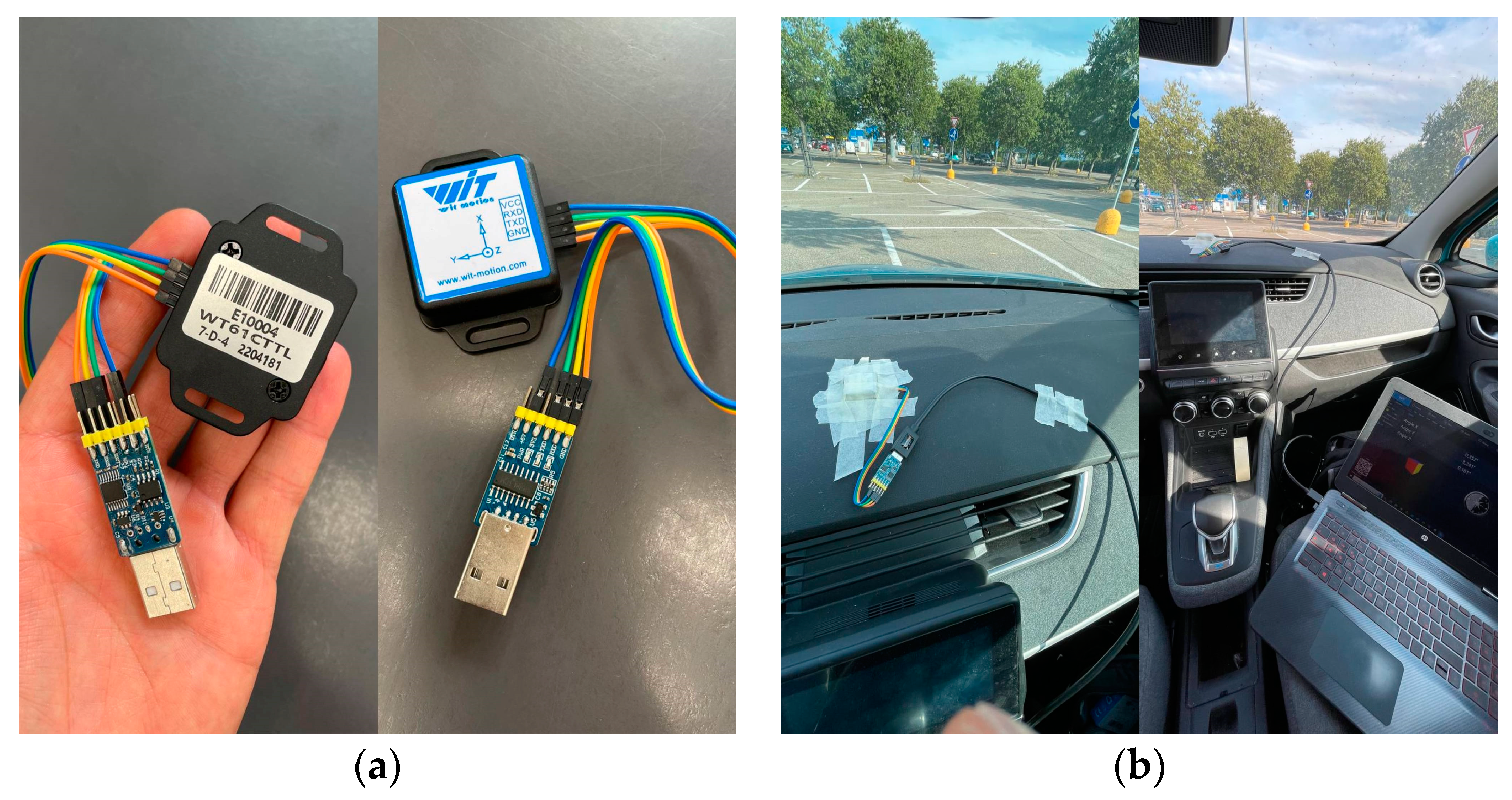

- Every vehicle was equipped with the same accelerometer that was calibrated before every acceleration probe;

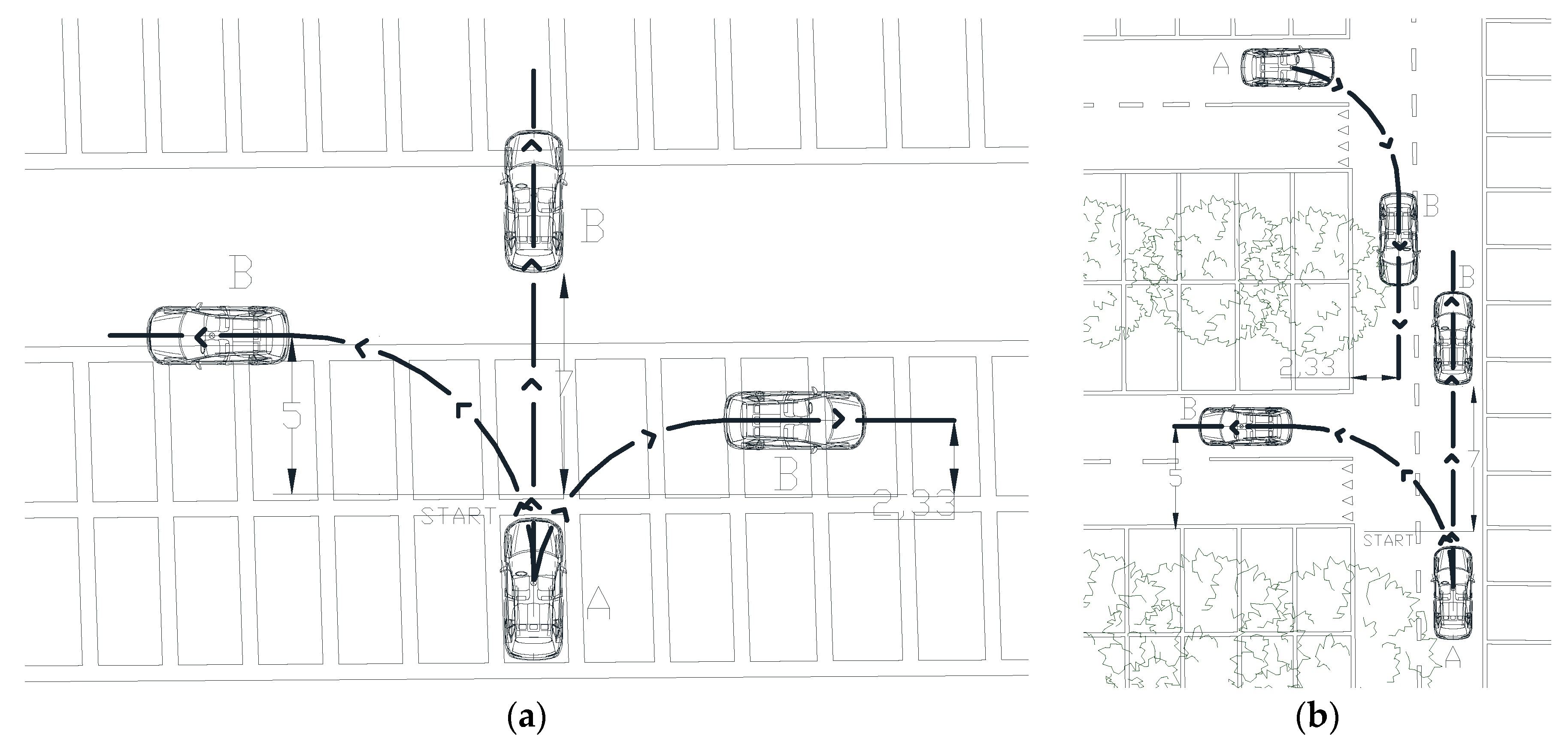

- Every manoeuvre was repeated multiple times and all of them were executed guaranteeing the minimum path, reported in Figure 1.

2.1. Materials

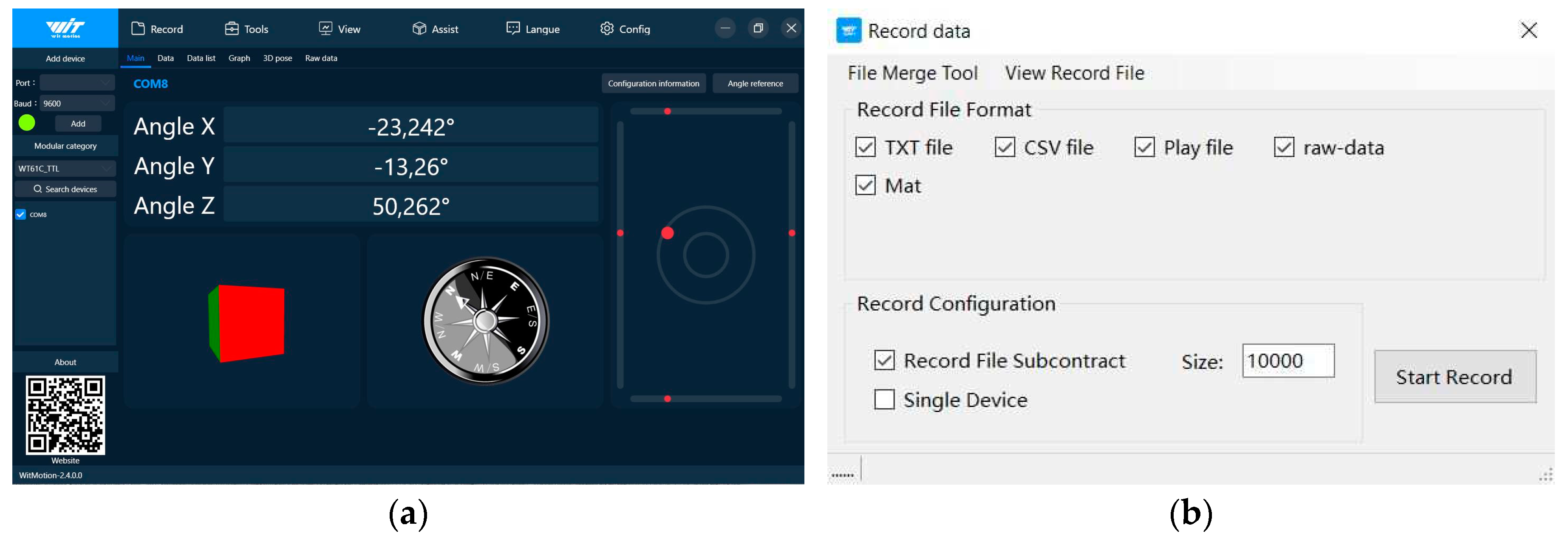

- WitMotion© accelerometer sensor WT61C-TTL

- TTL cable + extension USB cable

- Laptop

- WitMotion software [26]

2.1.1. Accelerometer

2.2. Methods: In-situ simulations and vehicles used

| Car brand | Model | Engine type | Displacement [cc] | Power [kW] | Fuel type | Mass[kg] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfa Romeo | Stelvio | Thermal | 2143 | 154 | Diesel | 1745 |

| Fiat | 500X | Thermal | 1956 | 103 | Diesel | 1570 |

| Volvo | XC60 | Mild hybrid | 1969 | 145 | Diesel | 1892 |

| Renault | Zoe E-tech | Full electric | - | 80 | Electric | 1577 |

- Lengthwise cross (LC);

- Left turn;

- Right turn.

- Slow start;

- Average start;

- Quick start.

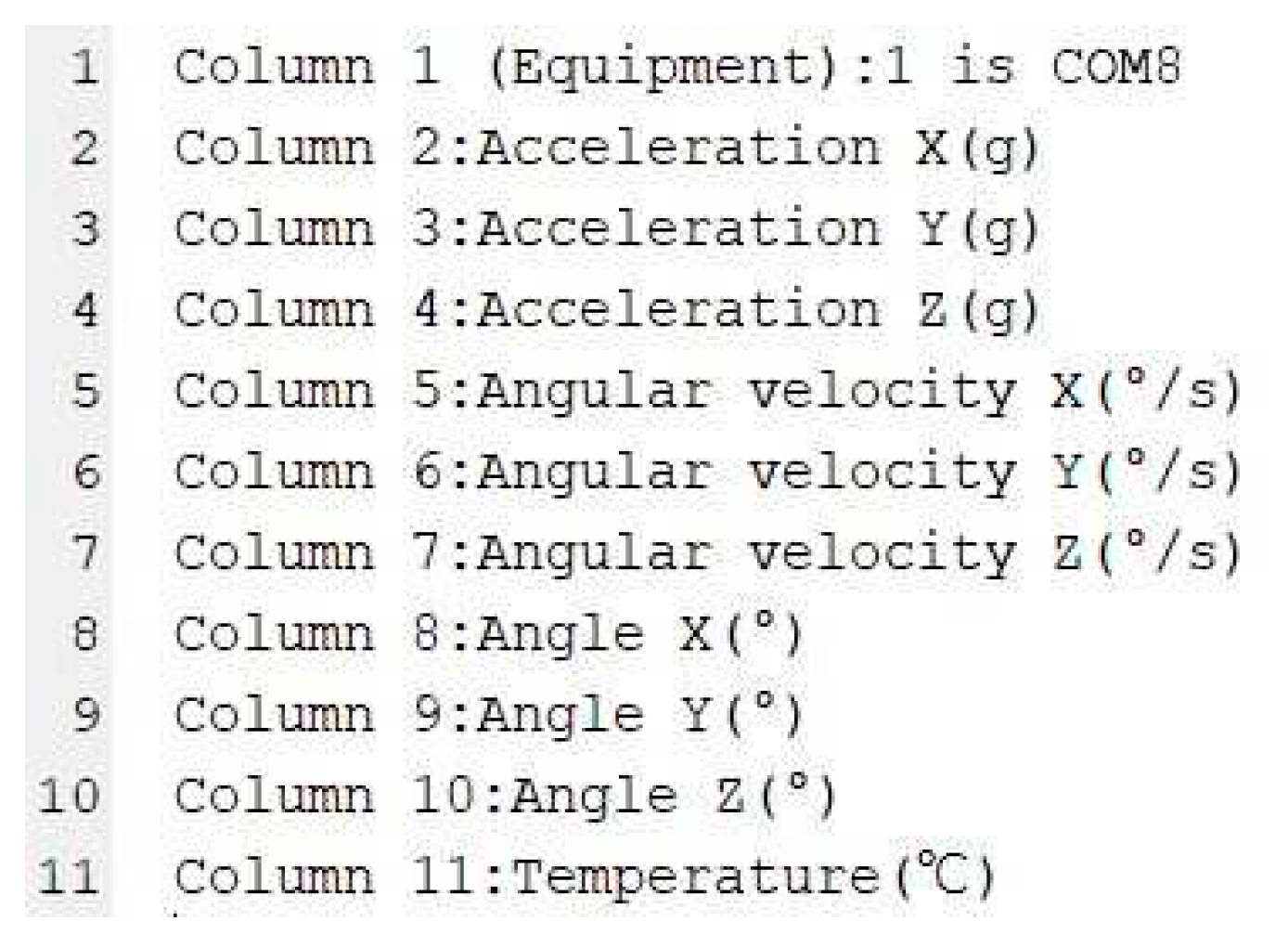

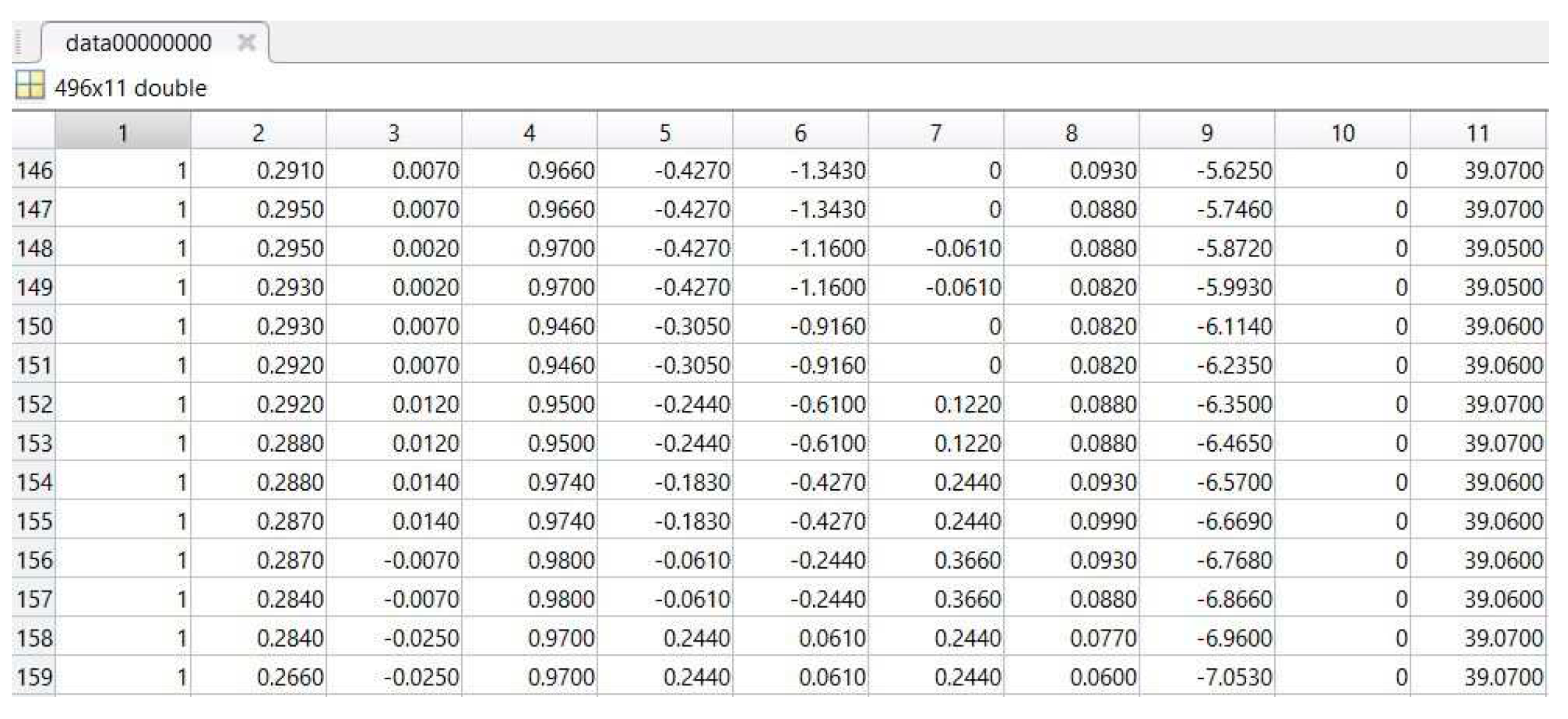

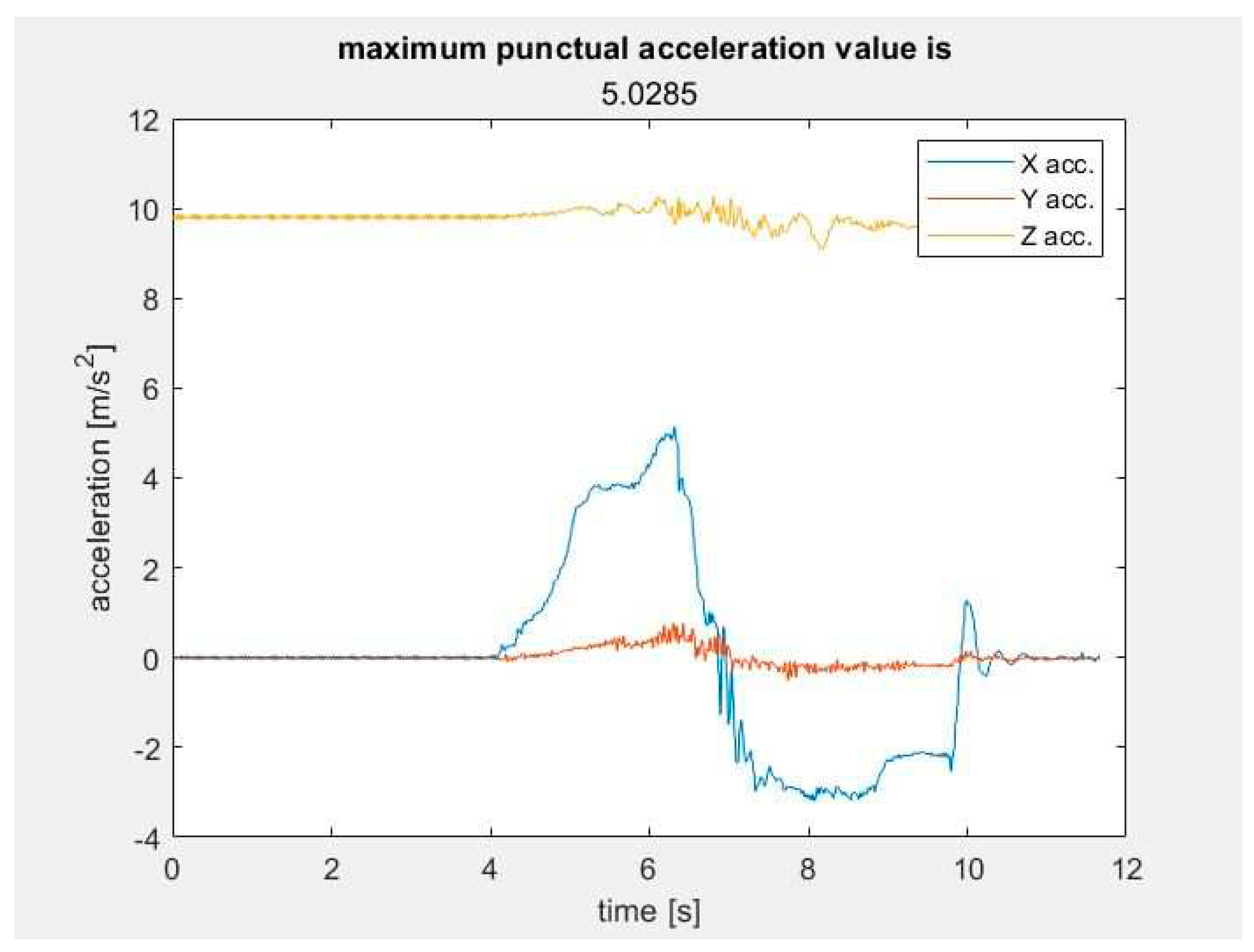

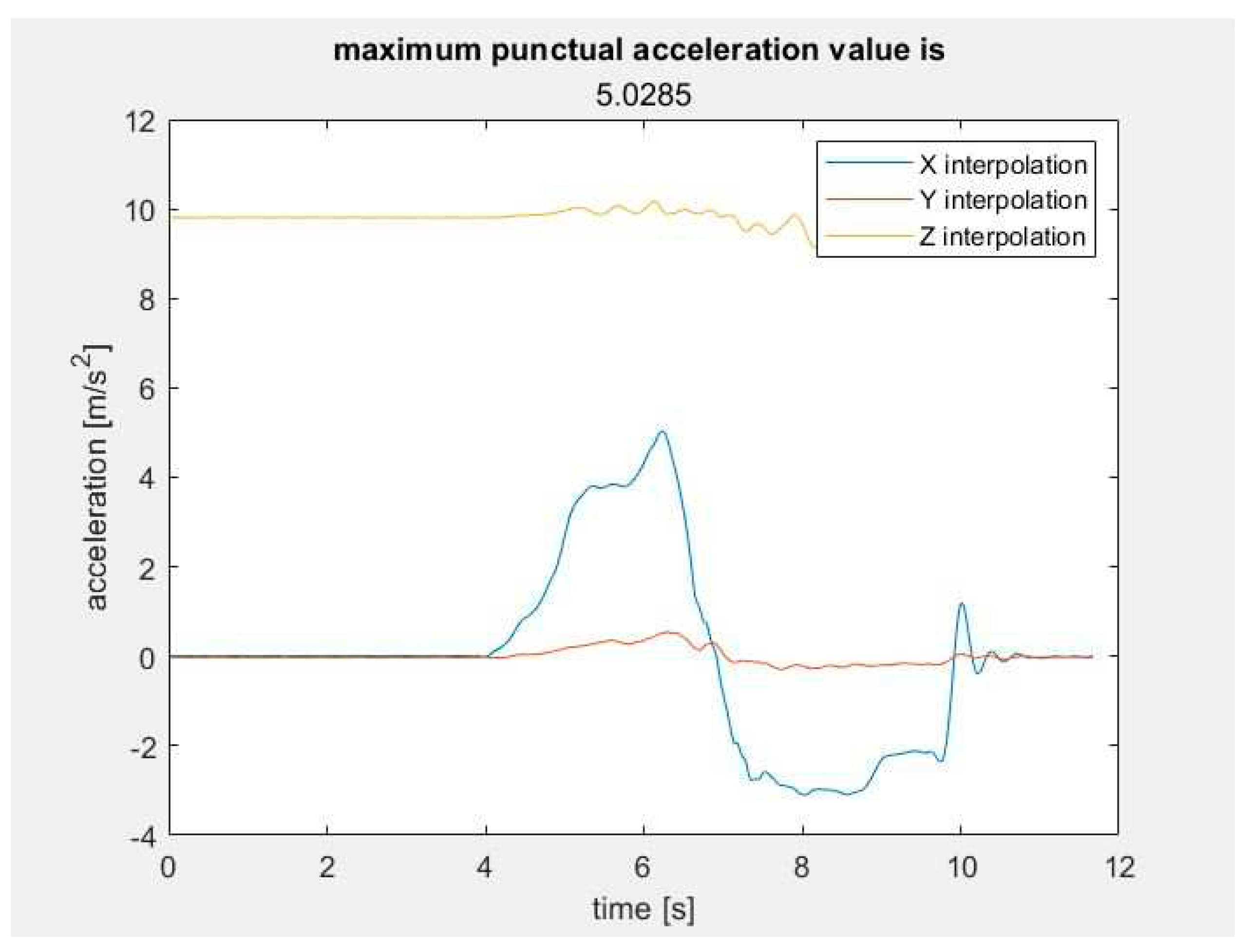

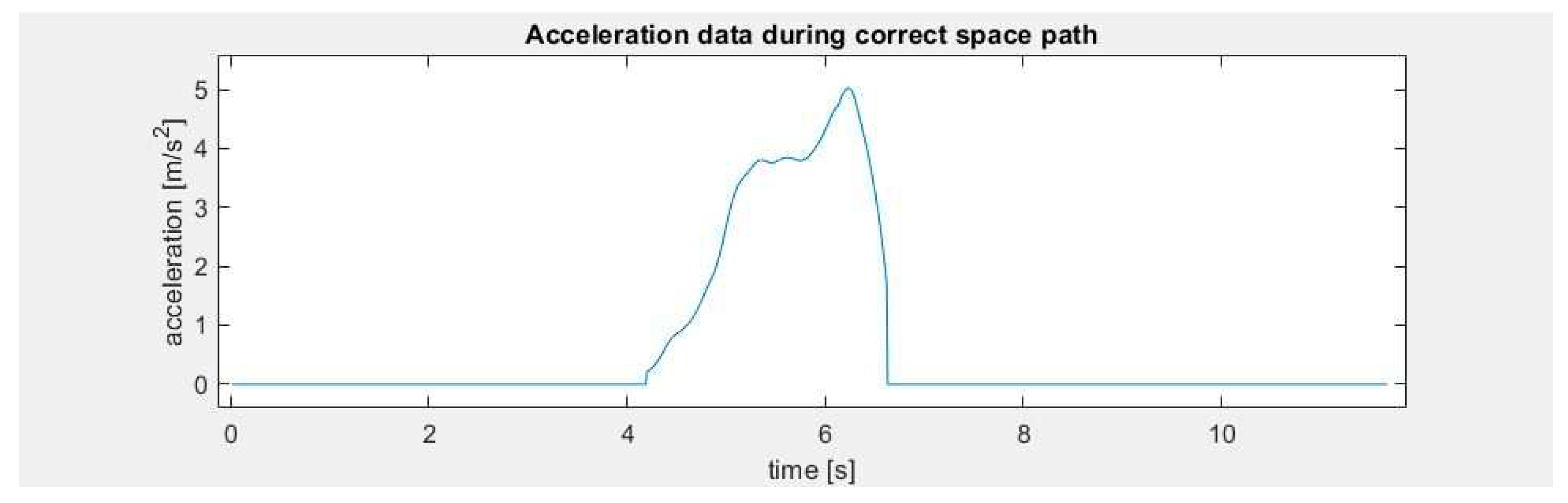

2.3. Data analysis: MATLAB© code

2.3.1. Input matrix

2.3.2. Noise filtering

2.3.3. Data sampling

- A threshold of has been used to disregard all the measures recorded during the time when the car is motionless, as it has been considered that an acceleration under this rate does not affect the whole medium evaluation and/or would only represent noise.

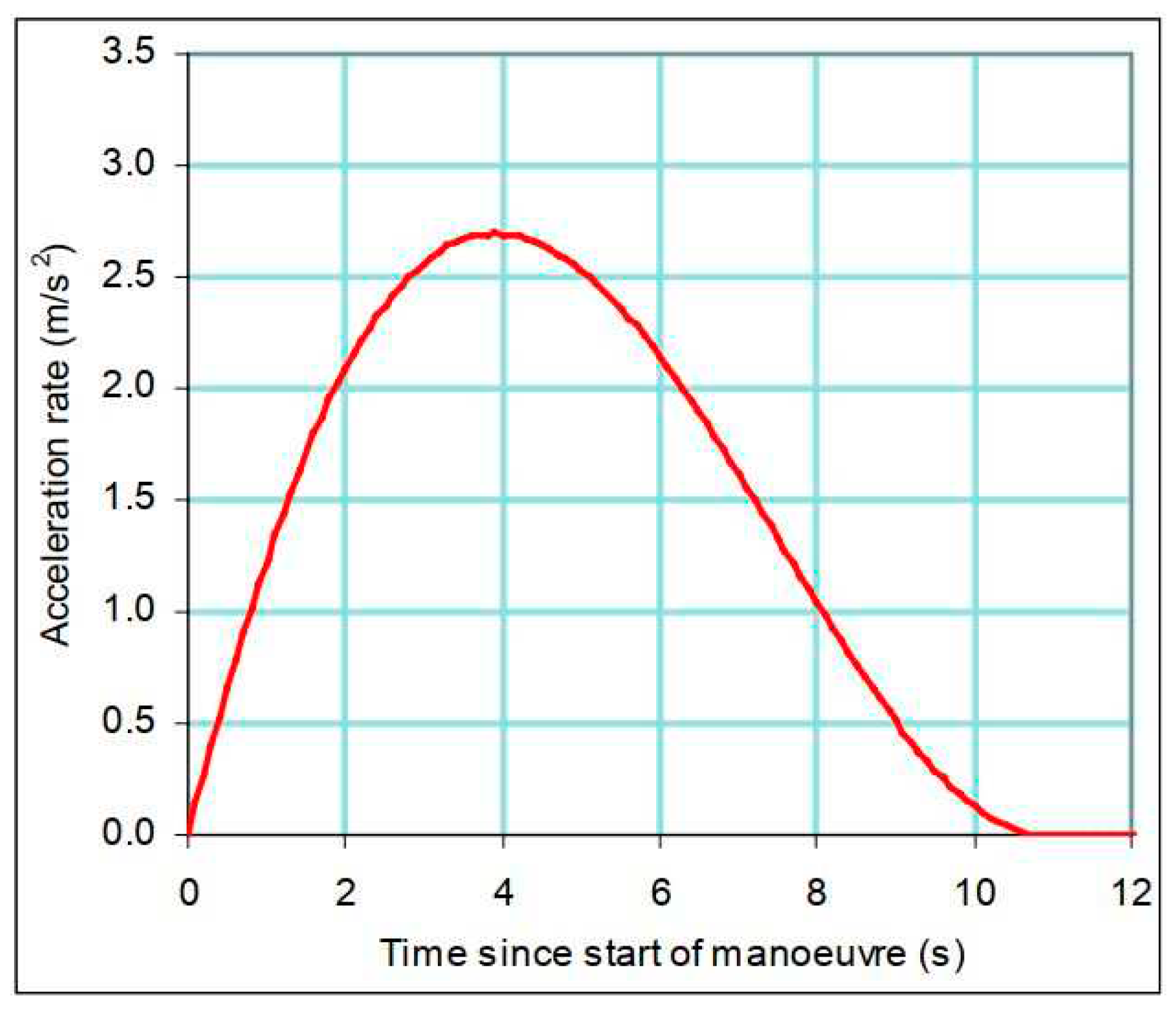

- For the purpose of extracting the last meaningful acceleration value included in the space interval, the function that describes the progress of the “x” interpolation (Figure 10) has been integrated twice, finding the speed function and the space travelled.

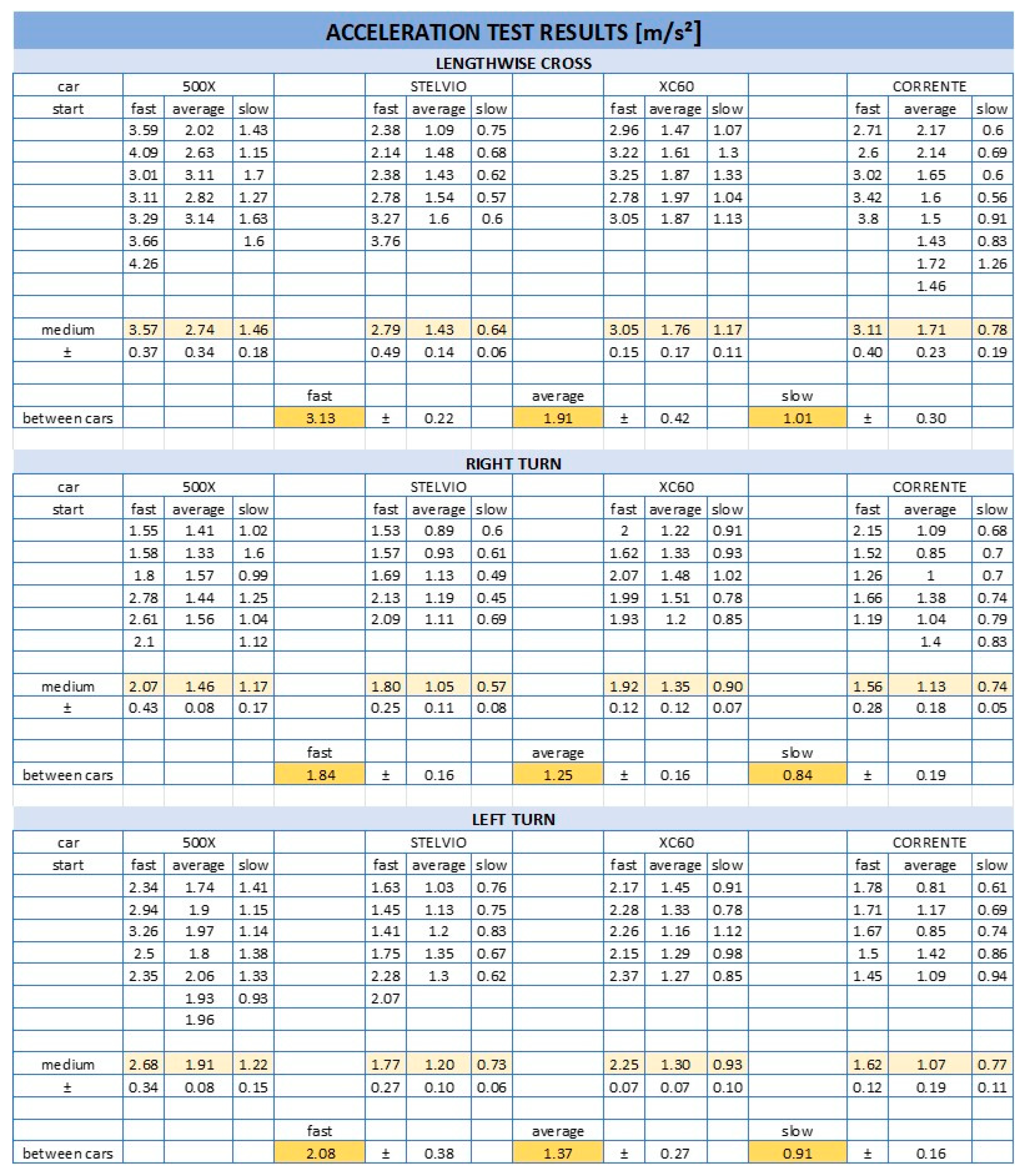

3. Results

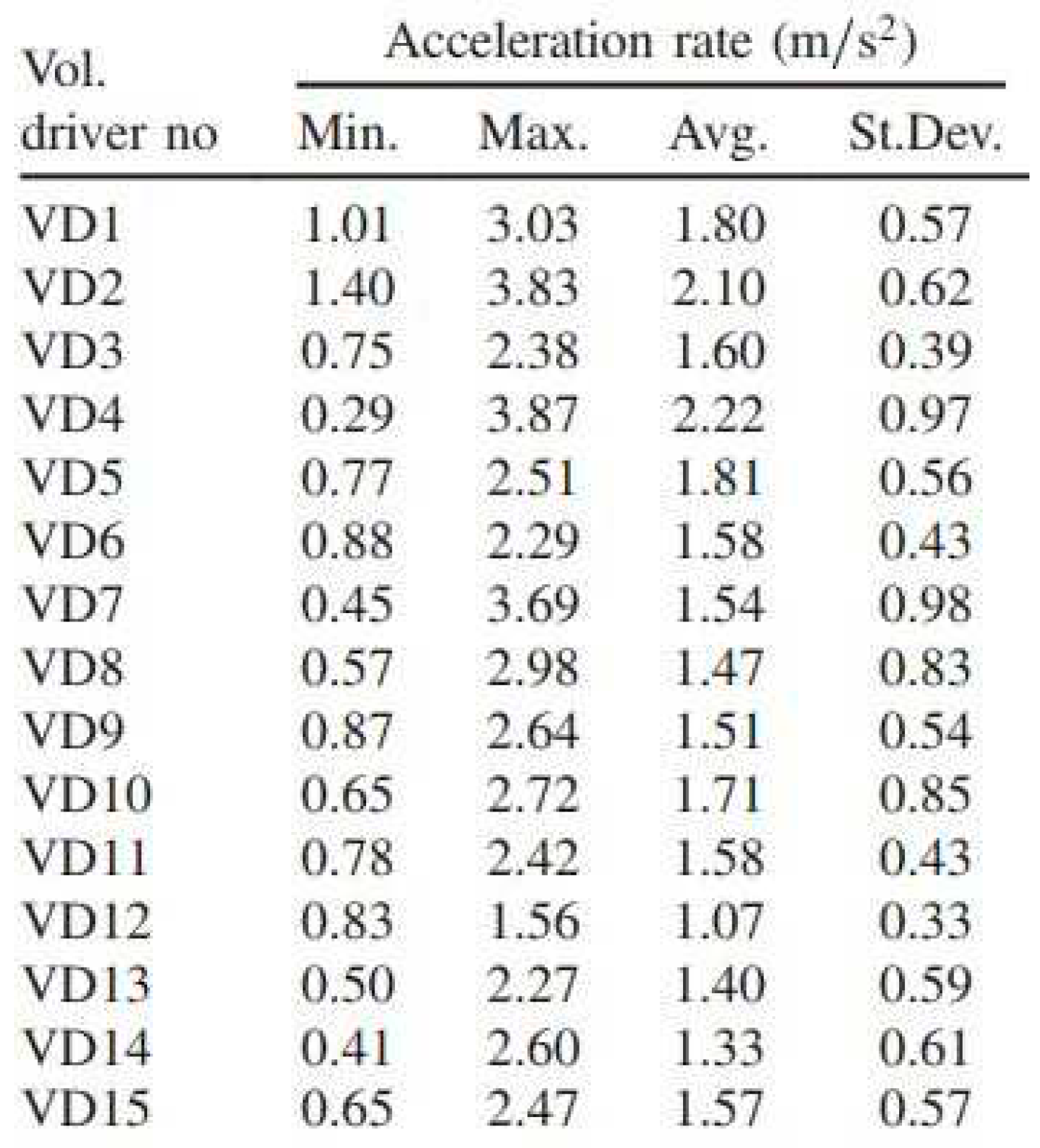

3.1. Average acceleration rates and interpretation

- Mean acc. ;

- Mean acc. .

- v₁ = √ (2∙2∙7) = ;

- v₂ = √ (2∙3∙7) = .

- t₁ = v₁/a₁ = 5,3÷2 = ;

- t₂ = v₂/a₂ =6,5÷3 = .

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Resume

- The number of probes sustained has been equally distributed between the manoeuvres of lengthwise crossing, left turn and right turn, executed adopting fast, average and slow starts;

- The totality of tests has been conducted in flat surface sites, pictured in Figure 6, with asphalt pavement, in dry conditions and hot weather. The cars were driven by the author of this study, who is a 26-year-old male with 8 years of driving experience;

- The four cars (illustrated in Table 2) used for the tests present a weight-to-power ratio included in interval, two of them powered by a Diesel engine, one with a mild-hybrid Diesel powertrain and the last one fully electric;

- The accelerometer is a highly accurate capacitive sensor as described more in detail in paragraph 2.1.1, which was opportunely attached to a plain surface of each vehicles interior and was calibrated every time before the start of each probe;

- The values deducted in this work are sampled and then calculated following the arithmetic mean and the average deviation of each value from the mean.

| Unit [m/s²] | Quick start | Average start | Slow start |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lengthwise crossing | 2,91 ÷ 3,35 | 1,49 ÷ 2,33 | 0,71 ÷ 1,31 |

| Right turn | 1,68 ÷ 2,00 | 1,09 ÷ 1,41 | 0,65 ÷ 1,03 |

| Left turn | 1,70 ÷ 2,46 | 1,10 ÷ 1,64 | 0,75 ÷ 1,07 |

5.2. Final considerations

- Broadly, the average values achieved from the tests set to be the lowest for the right turn manoeuvre and the highest for the lengthwise crossing. This phenomenon might be explained considering the human action as a deterrent to reach high acceleration values, because the combinations of accelerating and steering in turning to a narrow curve leads to more energy dispersion than the sole action of accelerating in a straight direction. As a matter of fact, circular motion acceleration is the product of a centripetal and a tangential vector, where only the last one increases or decreases speed while the centripetal is necessary to keep a circular path and it transforms into friction between the tyres and the asphalt, which generates energy losses;

- Along the study, the influence of the weight-to-power ratio on the acceleration results is not discussed. On this topic, Murro [6] reported that after conducting a statistic analysis, this ratio doesn’t considerably affect the estimation of the values, but it has a minimum impact on the dispersion interval width calculated from the average mean values. Reporting the conclusion on this discussion, the vehicles with lower weight-to-power ratio present a more uncertainty traduced in a wider deviation from the reference value, while the vehicles with higher ratio present a smaller deviation;

- The influence of driver’s age on the test measures is not analysed, but in any case, the predecessors’ studies didn’t find any correlation even though the drivers with less experience used to have a more cautious behaviour;

- Comparing the results found in this study (Table 4) with those reported from precedent papers and cited inside the literary review, the values are comparable with Murro [6] reports while they are higher related to all the other citations. This contrast might be caused by the different instruments used in measuring the acceleration values (GPS instead of MMS sensor), different layout scheme of the probes and dissimilar purpose of the test, while on the other hand, lots of analogies with Murro [6] in planning the probes and the type of sensor adopted (chosen to keep a continuity in the study reason), led to similar values, even if the cars used in these probes and the instruments are much recent;

- Bearing in mind the calculations of the space needed between the cars reported in Table 3, it is important to specify that the time considered when computing these measures is the sole interval that goes from the moment in which the tyres move on the asphalt to the moment in which the last protruding part of the car completes the path selected. In reality, when a car driver decides to perform the manoeuvre, many time frames elapse between the decision and the actual moment in which the car starts to move. For example, the psychotechnical interval of the driver, or the actual response of the actuators and the control unit of the vehicle, or the technical time required for the engine to deliver power at the tyres. All of these variables are taken into account in detailed incident reconstructions and add space to the outcomes found during this study, that are based only on the completion of the manoeuvres. Therefore, even though the pictures at Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16 delineate a space that seems to be wider than the reality, it must be even more enlarged. As a matter of fact, the highest level of prudence is always required on the road, to prevent every sort of incidents.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ISTAT Infografica sugli incidenti stradali - Anno 2019. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/245759 (accessed on 9 November 2023).

- ACI Gli incidenti stradali 2019 nelle 106 province italiane. Available online: http://www.aci.it/archivio-notizie/notizia.html?cHash=e00a4d4f57218391bf026cd673232436&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=2378 (accessed on 9 November 2023).

- Mondal, S.; Gupta, A. Evaluation of Driver Acceleration/Deceleration Behavior at Signalized Intersections Using Vehicle Trajectory Data. Transportation Letters 2023, 15, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G. Acceleration Characteristics of Starting Vehicles. Transportation Research Record 2000, 1737, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dixon, K.K.; Li, H.; Ogle, J. Normal Acceleration Behavior of Passenger Vehicles Starting from Rest at All-Way Stop-Controlled Intersections. Transportation Research Record 2004, 1883, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murro, A. Valori accelerometrici dei veicoli in immissione nelle intersezioni. ASAIS: Associazione per lo Studio e l’Analisi degli Incidenti Stradali, 2009; 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Şentürk Berktaş, E.; Tanyel, S. Effect of Autonomous Vehicles on Performance of Signalized Intersections. J. Transp. Eng., Part A: Systems 2020, 146, 04019061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snare, M.C. Dynamics Model for Predicting Maximum and Typical Acceleration Rates of Passenger Vehicles, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: Blacksburg, Virginia, 2002.

- Bokare, P.S.; Maurya, A.K. Acceleration-Deceleration Behaviour of Various Vehicle Types. Transportation Research Procedia 2017, 25, 4733–4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Kim, E. Critical Aggressive Acceleration Values and Models for Fuel Consumption When Starting and Driving a Passenger Car Running on LPG. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation 2017, 11, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, R.; Inman, V.; Dixson, A.; Warren, D. Use of Intelligent Transportation System Data to Determine Driver Deceleration and Acceleration Behavior. Transportation Research Record 2004, 1899, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lin, W.; Wang, X.; Shao, Y.-M. Acceleration and Deceleration Calibration of Operating Speed Prediction Models for Two-Lane Mountain Highways. J. Transp. Eng., Part A: Systems 2017, 143, 04017024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ng, E.C.Y.; Zhou, J.L.; Surawski, N.C.; Chan, E.F.C.; Hong, G. Eco-Driving Technology for Sustainable Road Transport: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 93, 596–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glauz, W.D.; Harwood, D.; John, A.D.S. Projected Vehicle Characteristics through 1995. Transportation Research Record 1980, Journal of the Transportation Research Board 772, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, S.; Jarvis, J. Acceleration and Deceleration of Modern Vehicles. Australian Road Research Board 1978, 86, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, S.K.; Madugula, M. Acceleration characteristics of automobiles in the determination of sight distance at stop-controlled intersections. Civil engineering for practicing and design engineers 1986, 5, 487–498. [Google Scholar]

- Akçelik, R.; Biggs, D.C. Acceleration Profile Models for Vehicles in Road Traffic. Transportation Science 1987, 21, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonneson, J.A. Modeling Queued Driver Behavior at Signalized Junctions. Transportation Research Record 1992, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bham, G.H.; Benekohal, R.F. Development, Evaluation, and Comparison of Acceleration Models. In Proceedings of the 81st Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC; Washington, DC, 2002; Vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Akçelik, R.; Besley, M. Acceleration and Deceleration Models. 23rd Conference of Australian Institutes of Transport Research 2002, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dabbour, E.; Easa, S.M. Revised Method for Calculating Departure Sight Distance at Two-Way Stop-Controlled (TWSC) Intersections. Transportation Research Record 2021, 2675, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbour, E. Design Gap Acceptance for Right-Turning Vehicles Based on Vehicle Acceleration Capabilities. Transportation Research Record 2015, 2521, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbour, E.; Easa, S. Sight-Distance Requirements for Left-Turning Vehicles at Two-Way Stop-Controlled Intersections. Journal of Transportation Engineering, Part A: Systems 2016, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbour, E.; Easa, S.M.; Dabbour, O. Minimum Lengths of Acceleration Lanes Based on Actual Driver Behavior and Vehicle Capabilities. J. Transp. Eng., Part A: Systems 2021, 147, 04020162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niels, T.; Erciyas, M.; Bogenberger, K. Impact of Connected and Autonomous Vehicles on the Capacity of Signalized Intersections – Microsimulation of an Intersection in Munich. Proceedings of 7th Transport Research Arena TRA 2018 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- WitMotion Shenzhen Co., Ltd. WitMotion Software.

- Kalman Filter. Wikipedia 2023.

- Gazzetta Ufficiale Art.1: Regolamento per l’esecuzione Del Testo Unico Delle Norme Sulla Disciplina Della Circolazione Stradale . Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaArticolo?art.versione=1&art.idGruppo=1&art.flagTipoArticolo=1&art.codiceRedazionale=059U0420&art.idArticolo=1&art.idSottoArticolo=1&art.idSottoArticolo1=10&art.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=1959-06-30&art.progressivo=0 (accessed on 9 November 2023).

- Savitzky–Golay Filter. Wikipedia 2023.

- Microsoft Corporation Microsoft Excel 2018.

| Maneuver type | Start | Acceleration [m/s²] |

|---|---|---|

| Right turn | Slow | 0,57 ÷ 1,06 |

| Average | 0,91 ÷ 1,62 | |

| Quick | 1,43 ÷ 2,41 | |

| Left turn | Slow | 0,68 ÷ 1,20 |

| Average Quick |

1,05 ÷ 1,72 1,64 ÷ 2,65 |

|

| Lengthwise cross | Slow | 0,83 ÷ 1,49 |

| Average | 1,26 ÷ 2,05 | |

| Quick | 2,05 ÷ 3,11 |

| Incoming vehicle speed | Lengthwise cross | Right turn | Left turn |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 km/h | 22,9 m | 28,8 m | 33,5 m |

| 50 km/h | 38 m | 48 m | 55,9 m |

| 70 km/h | 53,3 m | 67,1 m | 78,1 m |

| 90 km/h | 68,5 m | 86,3 m | 100,5 m |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).