1. Introduction

N. virgatus is a low-value marine fish and the second largest species for processing surimi products [

1]. As we all know, the gel characteristics of surimi are a crucial indicator of the quality, and it will reduce during the production process. Therefore, we can choose a cheap and safe exogenous additive to enhance the gel qualities of surimi products, which can help to efficiently utilize low-value fish and reduce production costs [

2,

3].

The starch is gelatinized by heating, and the internal particles are expanded to fill the network structure of the gel, thereby improving the quality of the surimi products [

4,

5,

6]. Different starches and dosages have different effects, and too much starch will affect the quality of surimi [

7,

8]. Studies have found that when potato starch is added at an amount of 16% (wt/wt), starch-protein interaction is most conducive to promoting the hairtail surimi gel [

5]. However, others believe that adding 8% (wt/wt) of sweet potato starch has the best effect on improving the quality and network structure of surimi gel [

9]. Therefore, there may be a saturation state for cross-linked protein to starches, which limits the texture properties of surimi gel. At the same time, some scholars have found that the different amount of starch added also has a difference in the changes of chemical force in the surimi matrix [

4,

10]. And the mechanisms that cause this change are different. It is believed that starch may interact with myofibrillar proteins through electrostatic or hydrogen bond interactions, contributing to improving the gel texture of surimi gels [

11]. But it may also be that the destruction of the structure of starch after heating causes the macromolecular polymer to bind to myofibrillar protein residues, resulting in changes in chemical force [

4]. This is because the enhancement of the texture properties of surimi gel and the change of intermolecular forces are affected by the type of starch and the amount of starch added. Therefore, it is still necessary to investigate the influence mechanism of different types and amounts of starch on the molecular structure and molecular interaction of myofibrillar protein and its relationship with the quality of surimi products.

Tapioca starch is a high amylopectin with a strong swelling ability, which can make surimi form a strong adhesion gel [

12]. Moreover, tapioca starch particles are larger, a slight expansion can produce a large viscosity, and the gel network structure plays a good filling effect [

13]. There are also some related studies on the impression of tapioca starch on the texture properties of surimi gel. It was found that the addition of tapioca starch and modified starch altered the physicochemical properties and protein structure of surimi gel in the low concentration range [

8]. However, many studies have only compared the effects of natural tapioca starch with modified starch on the gel properties and microstructure of surimi [

14,

15]. The multi-scale comprehensive analysis of natural tapioca starch and its added amount on physicochemical properties, microstructure, and molecular interactions of surimi gel has not been investigated.

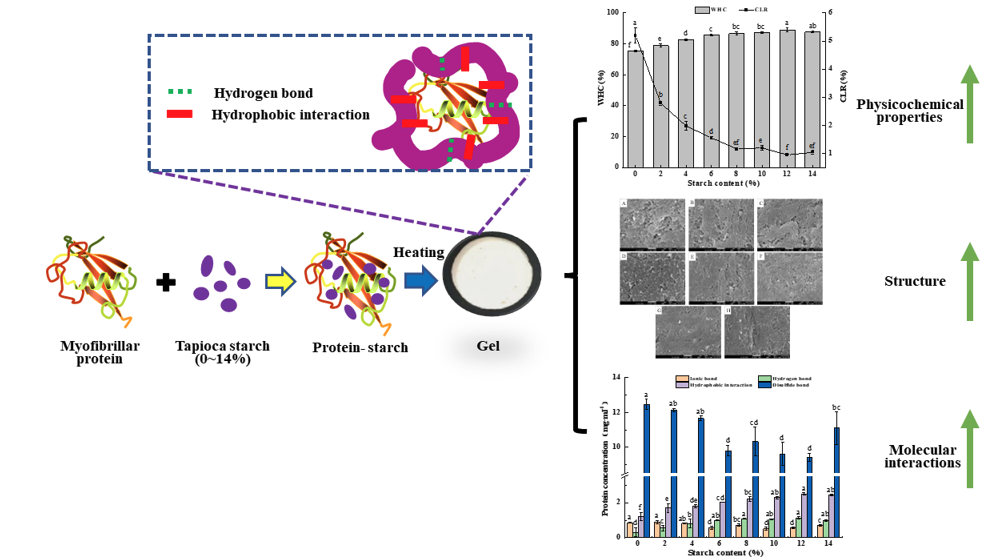

Tapioca starch with a high amylopectin content may change the structure and chemical interaction forces of surimi protein, and these intermolecular forces may have a certain correlation with gel quality. Therefore, to verify this result, tapioca starch-filled N.virgatus surimi gel was prepared. The physicochemical properties, microstructure, and molecular interaction of the complexed surimi gel were investigated. This study not only provides a reference for enhancing the quality of surimi products but also helps to understand the underlying mechanisms of tapioca starch to improve the quality of surimi gel.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Commercially frozen N. virgatus surimi (AAA grade, 78.23% moisture content, 16.43% protein content) was provided by Yangjiang Yonghao Aquatic Products Co., Ltd. (Yangjiang, China). Native tapioca starch (Food-grade) was purchased from Hebei Baiwei Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Handan, China). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

2.2. Preparation of Surimi Gel

Surimi gel was prepared based on a previous study [

16] with some modifications. The surimi was minced in a Stephan chopper (UMC 5, Stephan Machinery Co., Hameln, Germany) at 900 rpm for 1 min. 2.5% (wt/wt) NaCl was added to the surimi and chopped together for 1 min. Subsequently, the water was adjusted to 80%. Starch (0-14% (wt/wt) was mixed in the surimi pastes and minced at 1800 rpm for 3 min. The prepared surimi homogenate was filled into 25 mm plastic tubes and sealed at both ends. Two-stage heating gelation (heating at 40 ℃ for 30 min and heating at 90 ℃ for 20 min) was performed, and the heated surimi gel was placed at 4 ℃ for 12 h.

2.3. Determination of Gel Texture Properties

The surimi was left to equilibrate at room temperature and cut into cylinders (20 mm × 20 mm). The prepared samples were determined using a texture analyzer (TA-XT plus C, Stab Micro System, Godalming, UK). The probe type for measuring the gel strength was a cylinder of P/0.5, and TPA (Texture Profile Analysis) was measured using a P/0.5S spherical plunger [

3]. The program was set as follows: the measure before the test was 5.0 mm/s, the speed during the measure and the speed after the measure was 1.0 mm/s, the strain was 50%, and the trigger force was 5.0 g.

2.4. Determination of WHC

The sample was sliced thinly about 3 mm and weighed accurately (

M1), wrapped in paper, and centrifuge (temperature: 4 ℃, centrifugal force: 5000 ×g, time: 10 min). The weight (

M2) after centrifugation was quickly recorded [

17]. The calculation formula was as follows (Eq. (1)):

2.5. Determination of CLR

The prepared gel is sliced and weighed accurately (

G1) in a cooking bag (Jingsu Industries Ltd., Guangzhou, China). Subsequently, the samples were heated in hot water at 90 °C for 20 min. The samples were retrieved and placed in 4 ℃ for 24 h. The samples were dried and weighed (

G2) [

16]. The calculation formula was as follows (Eq. (2)):

2.6. Determination of Whiteness

Gel samples are sliced into thin slices (5×20×20 mm

3) and placed in clear plastic dishes [

8]. Measure whiteness values using a colorimeter (3 nh, Shenzhen Technology Company, Shenzhen, China). The calculation is as follows (Eq. (3)):

2.7. Determination of Low-Field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (LF-NMR)

The moisture distribution of the sample was measured by a nuclear magnetic resonance imaging analyzer (NMI20-060H-I, Niumag Co., Suzhou, China). Using the CPMG pulse sequence, the relaxation time

T2 of the sample was measured. The program was set as follows: magnet frequency SF=21 MHz, spectral width SW=200 MHz, recovery delay TW=3000 ms, number of echoes NECH=5000, and number of scans NS=4. The

T2 spectrum was obtained by cumulative sampling and inversion by Multi Exp Inv Analysis software. The area of each peak in the integrated spectrum was accumulated, and the peak area indicated the percentage of water contained in the sample [

18].

2.8. Light Microscopic Observation

Cut the gel samples into slices of approximately 1.5 cm, dehydrated with 30% sucrose, fixed with a mixture of 30% sucrose and frozen section embedding medium (1:1, v/v) for 4 h. Frozen section embedding medium was fixed for another 4 h and placed in a -80 ℃ refrigerator freeze for 1 h. Subsequently, the gel sample was cut into 30 μm slices with a freezing microtome [

19], placed on glass slides, and stained with eosin for 2 min (the protein appears red). The morphological structure of gel was observed using a fluorescent inverted microscope (EVOS FL Auto2, USA Life Technologies Company, USA) at 200× magnification.

2.9. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Observation

The samples were sliced thinly about 1 mm and fixed with glutaraldehyde solution (2.5%, v/v; pH 6.8) for 4 h. Rinsed twice with phosphate buffer (0.1 mol/L, pH 6.8), dehydrated with different gradient concentrations of ethanol, washed with absolute ethanol-tert-butanol at a ratio of 1:1, finally washed with 100% tert-butanol. Surimi samples were freeze-dried for 48 h and at an accelerating voltage of 8 kV using an SEM (7610F, Japan Electronics Co., Ltd., Japan) to observe the microstructure with a magnification of 15 000×.

2.10. Determination of Molecular Forces

Molecular forces determination is performed by mimicking the operation of Jiang [

7]. Surimi samples ( 4 g ) were added to 20 mL of 0.05 mol/L NaCl solution (S1), 0.6 mol/L NaCl solution (S2), 1.5 mol/L urea+0.6 mol/L NaCl solution (S3), 8 mol/L urea + 0.6 mol/L NaCl solution (S4), 0.6 mol/L NaCl + 8 mol/L urea + 0.5 mol/L β-mercaptoethanol (S5). The mixture was homogenized with a high-speed disperser (IKA T-18 homogenous disperser, Southeast Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd. Guangdong, China) for 5 min and stood for 1 h at 4 ℃. Subsequently, the mixture was centrifuged at 8000 r/min for 15 min through a freezing centrifuge (JIDI-21K, Guangzhou Vicki Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China). The protein content of the supernatant was measured by Lowry [

10]. The formula for calculating non-covalent bonds is as follows (Eq. (4-7)):

2.11. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

The freeze-dried samples were mixed with potassium bromide (KBr) in a mass ratio of 1:100, ground into powder in an agate dish, and compressed into tablets. FT-IR spectroscopy (VERTEX70, Bruker Optice Inc., Carlsruhe Karlsruhe, Germany) was performed by scanning the sample 32 times in the wave number range of 4000~500 cm-1. The protein secondary structure was derived by fitting using Peakfit 4.12 software.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as the mean the mean ± standard deviation of the five experiments. The plotting software uses Origin 2023, and all data analysis is statistically significant by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s test (SPSS 22.0), with a P<0.05 difference.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Starch on the Physicochemical Properties of Surimi Gel

3.1.1. Texture Profile Analysis

Gel strength and TPA value are some of the indicators to measure the quality of surimi products. Proteins and starches aggregate and gel through heating, thereby promoting the texture properties of food [

20]. Textural properties of

N. virgatus surimi gels at different levels of tapioca starch addition (0-14% (wt/wt) are shown in

Table 1. Surimi gel containing tapioca starch showed significantly improved gel strength, hardness, gumminess, and chewiness (

P<0.05), but slightly decreased Cohesiveness (

P<0.05). When starch absorbs water and expands at a specific gelatinization temperature, starch particles squeeze and fill voids in the gel matrix, which leads to increased hardness and gel strength of the surimi gel [

5]. The gel strength, hardness, springiness, and gumminess of gels enhanced to varying degrees with the tapioca starch content increased until it achieved a maximum value when addition of 12% tapioca starch (

P<0.05). Which because of the increase in the amount of tapioca starch added leads to an increase of tapioca starch molecules per unit volume, and an increase in the content of hydrogen bonds between molecules, bring about a firm and dense network structure [

9]. In addition, the gel texture did not change when tapioca starch was added to 14%, which may be due to too much starch distribution in the protein structure can lead to bellyful cross-linking of polysaccharides with proteins, hindering protein-protein interactions and causing gel properties no longer changed or a downward trend [

7,

21]. The data are similar to other [

8] studies suggesting that excess starch decreases the gel properties of myofibrillar protein-starch complexes.

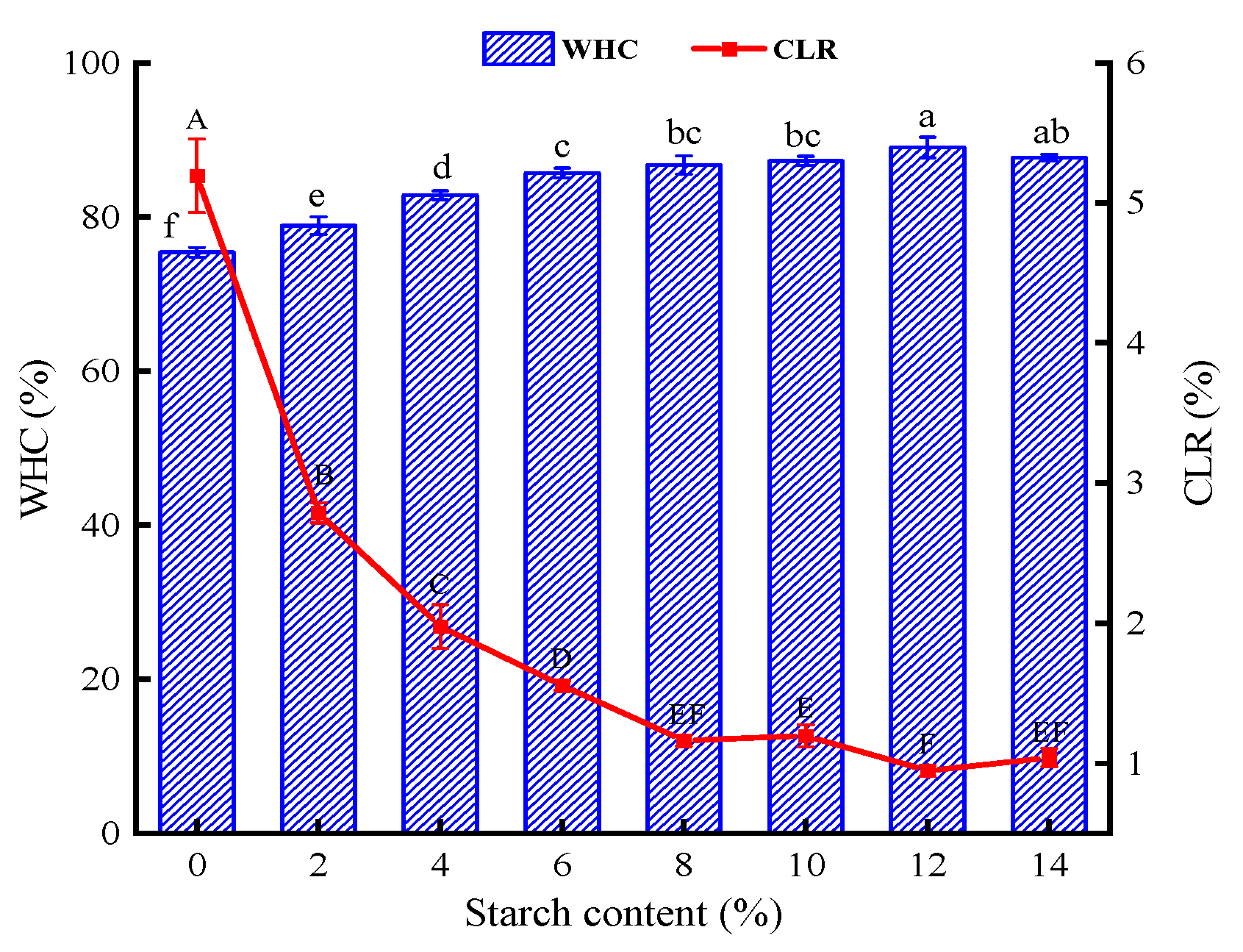

3.1.2. WHC and CLR

In general, a higher WHC and a lower CLR mean that the surimi gel can lock in plenty of water, forming a dense network structure [

22]. The WHC values of the surimi gels with the addition of tapioca starch were all enhanced, and the CLR values were all decreased in comparison to the surimi gels without tapioca starch (

Figure 1). Moreover, the WHC maintained an upward trend with the growth of tapioca starch addition (

P<0.05), except for the 14% group. The addition of 12% tapioca starch increased the WHC from 75.40 to 89.01% in the control group. As the heat-treated starch granules absorb water around the protein, the swollen starch granules squeeze the gel matrix, helping the surimi gel retain moisture [

9]. Especially for starch with relatively more amylopectin content, when the starch granule structure is damaged, it leads to amylopectin cleavage, and more hydroxyl groups are exposed to water, contributing to increased WHC of tapioca starch [

23]. Conversely, when the tapioca starch added reached 14%, the WHC was no longer rising, and the CLR was no longer falling. Luo et al [

5] came to the same conclusion, which found that a certain amount of starch can bind more water, increasing the WHC value to a certain extent. However, excess starch will contend with myofibrillar protein for water, and the part of starch dehydration can’t fully expand.

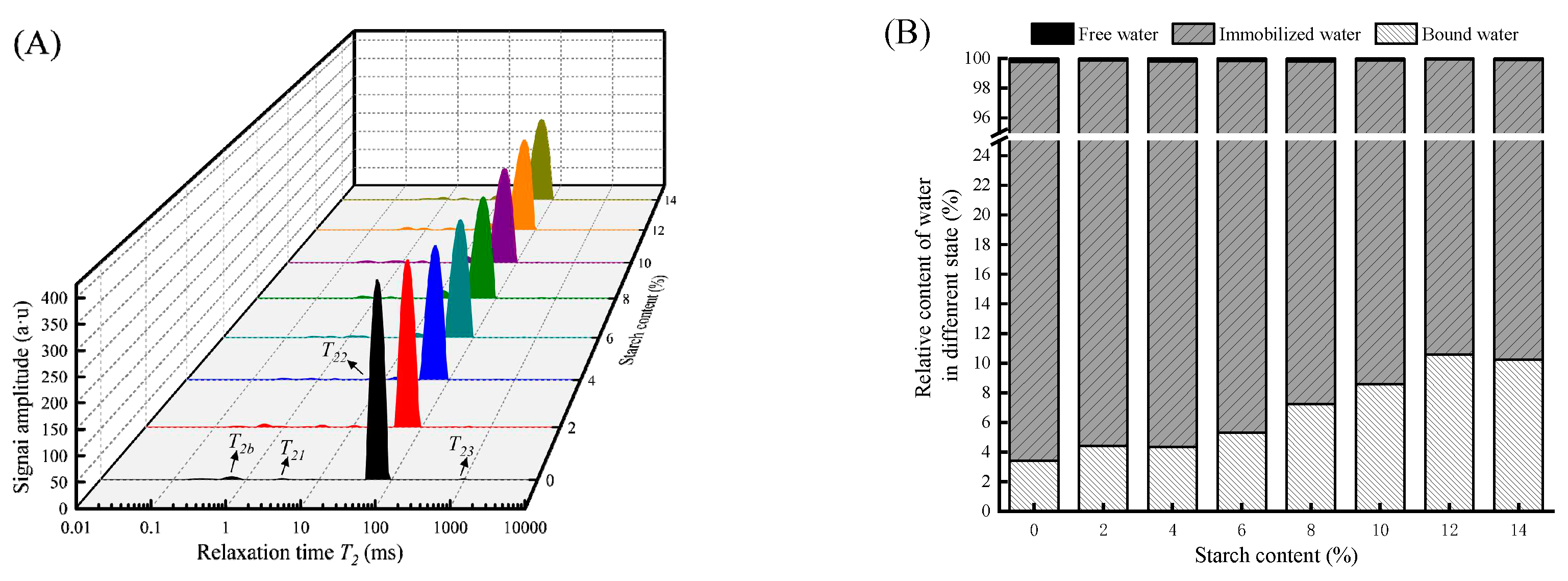

3.1.3. Water Distribution

LF-NMR is a novel method for assessing the distribution of moisture states in food [

5].

Figure 2A mainly reflects the influence of tapioca starch addition on the transverse relaxation time spectra of the gel. Three peaks in three regions were detected, namely

T21 (1-10 ms),

T22 (10-100 ms), and

T23 (>100 ms), representing bound water, immobilized water, and free water, respectively [

24]. In general, immobilized water dominates the water content in the surimi gels and is inseparable from the gel network structure [

25].

The relaxation time of each peak in the integral spectrum is calculated in

Table 2. The

T22 of immobilized water gradually decreased with the increase of tapioca starch (

P < 0.05), which indicated that tapioca starch raised the binding of hydrogen protons and lowered the free water. The higher the addition, the more hydrogen bonds were generated to bind tightly with the protein, thus reducing the mobility of the water [

3]. Moreover, the starch absorbs some of the water molecules in the surimi gel, causing more water locked by starch and adsorbed on the gel [

5], improving the WHC of the surimi gel. The relaxation time of immobilized water (

T22) was minimized at 12% of tapioca starch, reflecting the strongest binding ability to water and with the best WHC. The relative content of water in different states in the surimi gel is shown in

Figure 2B. Immobilized water content accounts for more than 89% and the other two types of water content account for less. After adding tapioca starch, the higher the starch content, the more the bound water content increases, and the free water content decreases. Gels had the best ability to bind water molecules when starch addition was 12%. On the one hand, a small amount of free water in the gel is converted into bound water, making the water molecules in the gel network stable [

25]. On the other hand, starch contains a lot of hydroxyl groups, which helps bind more water [

7]. Therefore, starch fills the gel network to some extent and could reduce the gel pore size, protecting water from leaking out of the gel pores.

3.1.4. Whiteness

As shown in

Table 3, after the addition of tapioca starch, the

L*,

a*, and

b* values of the surimi gel decreased (

P<0.05), thereby decreasing the whiteness of the surimi gel (

P<0.05). In addition, the higher the amount of starch added, the more adverse effect on the whiteness. According to scholars, the whiteness of surimi gel is related to the structure of the gel, as well as the type and color of the additive [

7]. Consequently, the decreased whiteness of the surimi gel is related to the change in gel network structure caused by the additional amount of tapioca starch and the color of the starch itself. The same conclusion was obtained by Luo et al [

5] in Hairtail surimi gels with potato starch. Large-sized starch granules have a strong expansion ability when heated and can fill voids in the gel structure, resulting in a reduction in voids and light that cannot pass through the gel surface, thereby reducing whiteness [

5]. However, the results of this study differ from existing reports in that they found that starch increased the whiteness value of surimi gel [

8]. The result may be some differences in the interactions between different starch types and surimi gel.

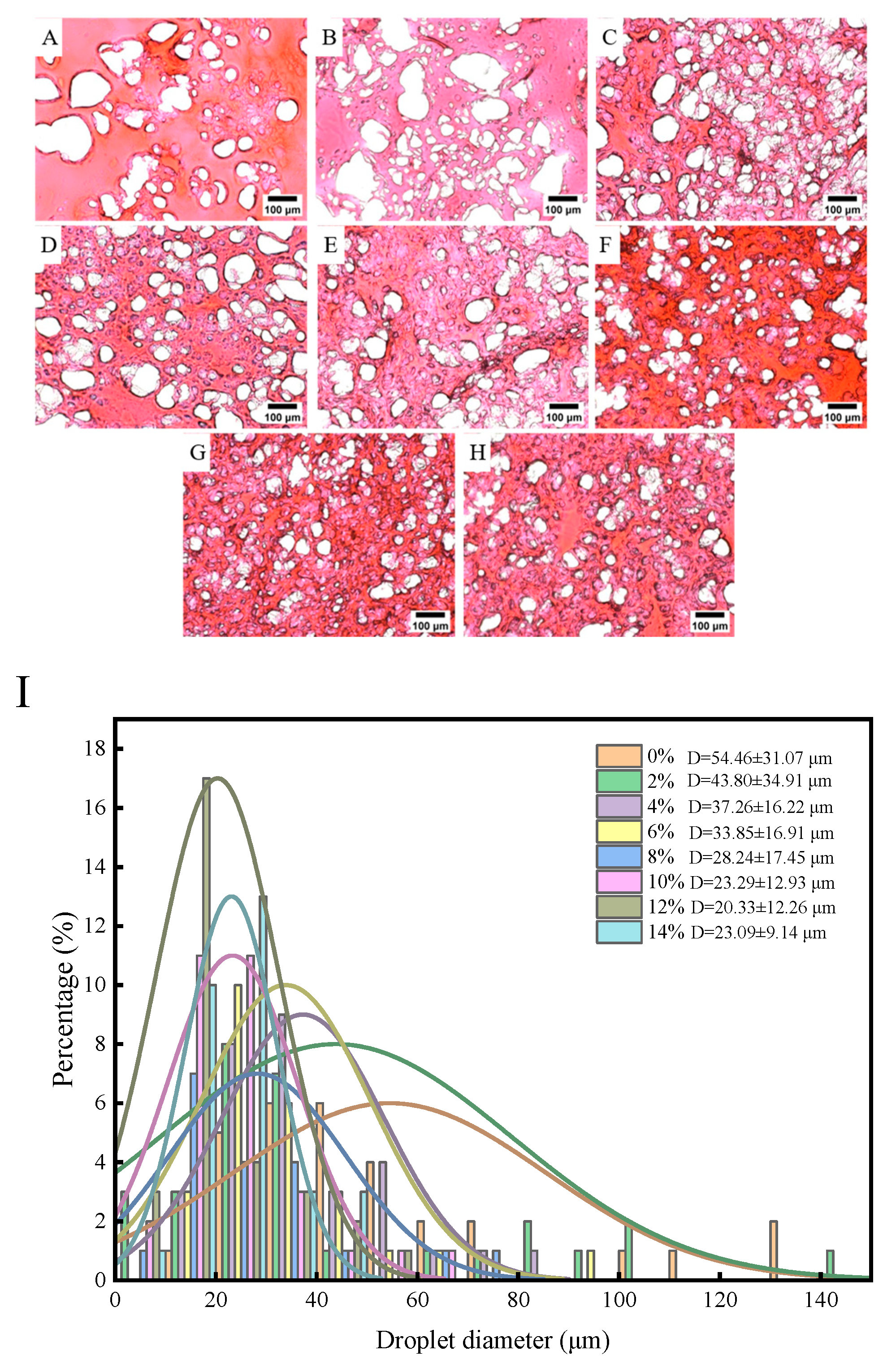

3.2. Effect of Starch on the microstructure of Surimi Gel

3.2.1. Light Microscopic Observation

Figure 3 shows the light microscope diagram, which mainly reflects the dispersion and morphology of tapioca starch in the gel structure.

Figure 3A can intuitively show that the morphological structure of the surimi gels without tapioca starch is relatively diffused, with an average cavities size of 54.46 μm (

Figure 3I). However, the surimi gel exhibited a more regular structure, and the space occupied by cavities gradually decreased with the increase of tapioca starch. The average cavity size of the surface decreased to the range of 20.33-43.80 μm (

Figure 3I). It is worth mentioning that the morphological structure became denser when the starch content was 12%, and the average cavity size decreased to 20.33 μm (

Figure 3I). Our result is compatible with other studies that starch can fill the network structure of myofibrillar proteins and reduce the average cavity size [

9]. The reduced cavity size of gels can be explained by the tapioca starch granules being heated and expanded to form web-like fibers within the cavities and act as bridges to hold the proteins together [

26]. However, different starch varieties have different particle sizes [

13]. Tapioca starch possesses large particle sizes is easy to absorb water and expand, and has a better filling effect on the gel network structure is better. In addition, the powerful dehydrating effect of tapioca starch can absorb water within the myofibrillar protein. Thus, dehydrated myofibrillar proteins have the potential to provide a better hydrophobic environment that promotes the unfolding of protein molecules and exposes hydrophobic groups during heat treatment [

27]. The highly compact network structure prevents the flow of water, which has a positive effect on maintaining moisture in the gel [

5]. Similarly, the gel structure did not change much when tapioca starch was added to 14%, further indicating that there is a threshold for the cross-linking of myofibrillar protein with tapioca starch. This phenomenon is the same as the conclusion of the water-holding studies.

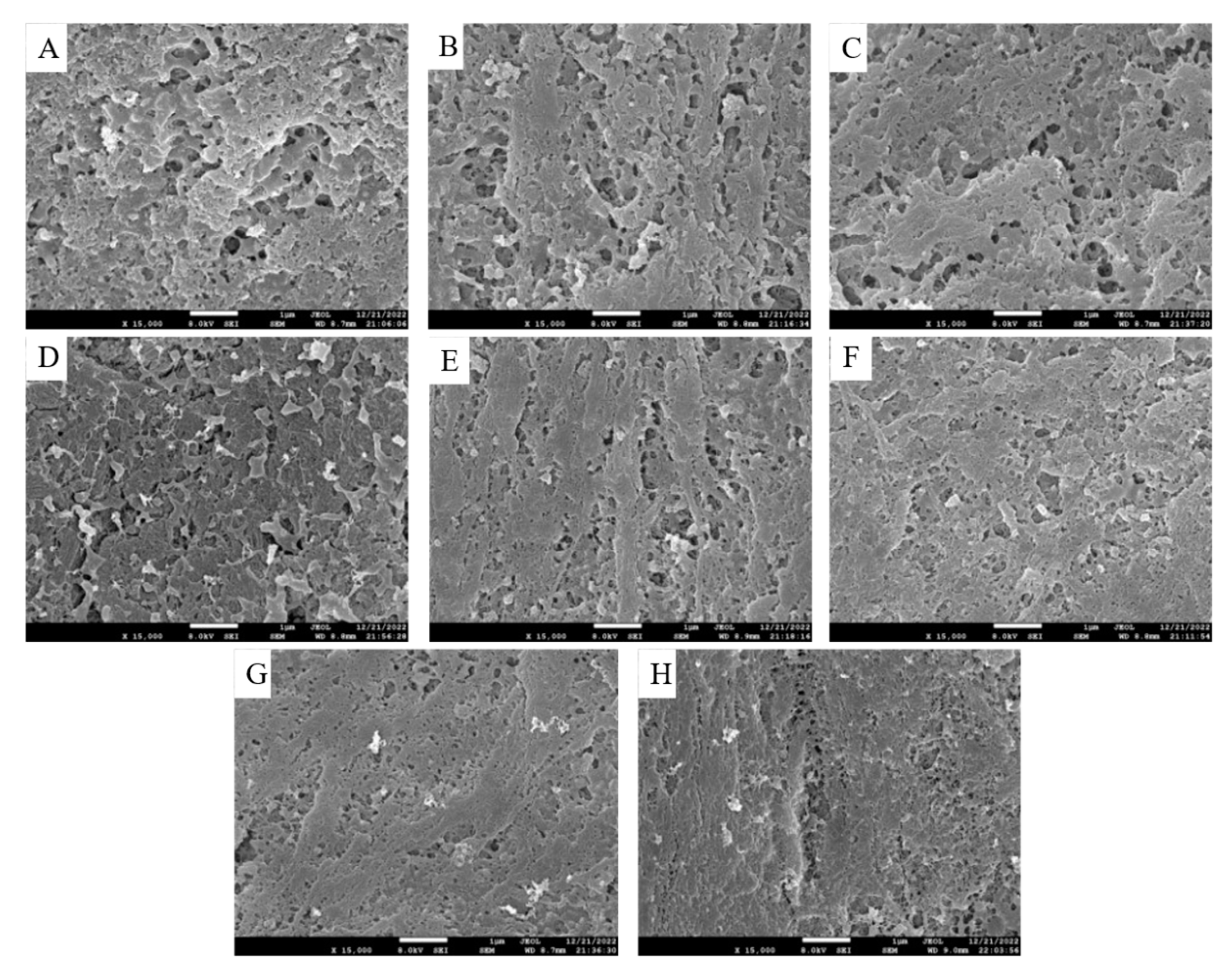

3.2.2. SEM Observation

SEM is a more intuitive analysis that can reflect the differences in the microstructure of surimi gels.

Figure 4A clearly shows that the surimi gel without tapioca starch has an extremely rough and loose surface, but surimi gels containing tapioca starch exhibit a low pore count and narrow pore size. When the tapioca starch addition reached 12%, the pores were minimal, and the gels showed a compact and uniform network microstructure. As a hydrophilic macromolecule, tapioca starch could serve as a hydrophilic filler for the network structure of surimi gels, which enhanced the physical stability of surimi gels by locking free water and interconnected water channels [

28]. In particular, tapioca starch increased the amount of water or some dry substances retained, thereby altering the microstructure [

9]. As a result, tapioca starch could lead water molecules to stabilize in the gel network structure and induce the gel to form a compact and uniform network structure. And this effect is enhanced with the increase of tapioca starch addition. Wu et al [

29] have the same conclusion that the amylopectins caused the scomberomorus phonics surimi gels to form a firm and ordered three-dimensional gel network with improved WHC. However, the gel structure did not change much at 14% of starch addition. Excessive starch competition for water in proteins can lead to protein dehydration that cannot fully unfold, resulting in some proteins not reaggregating and hindering the formation of gel network structures. SEM observations are the same as those described above by WHC and CLR. The dense network structure helps the gel to intercept water molecules and improve the WHC, while the loose network structure is not conducive to the reduction of CLR value in the gel. Consequently, when the tapioca starch addition reached 12%, the surimi gel exhibited a stable and ordered three-dimensional gel network.

3.3. Analysis of the Molecular Interactions

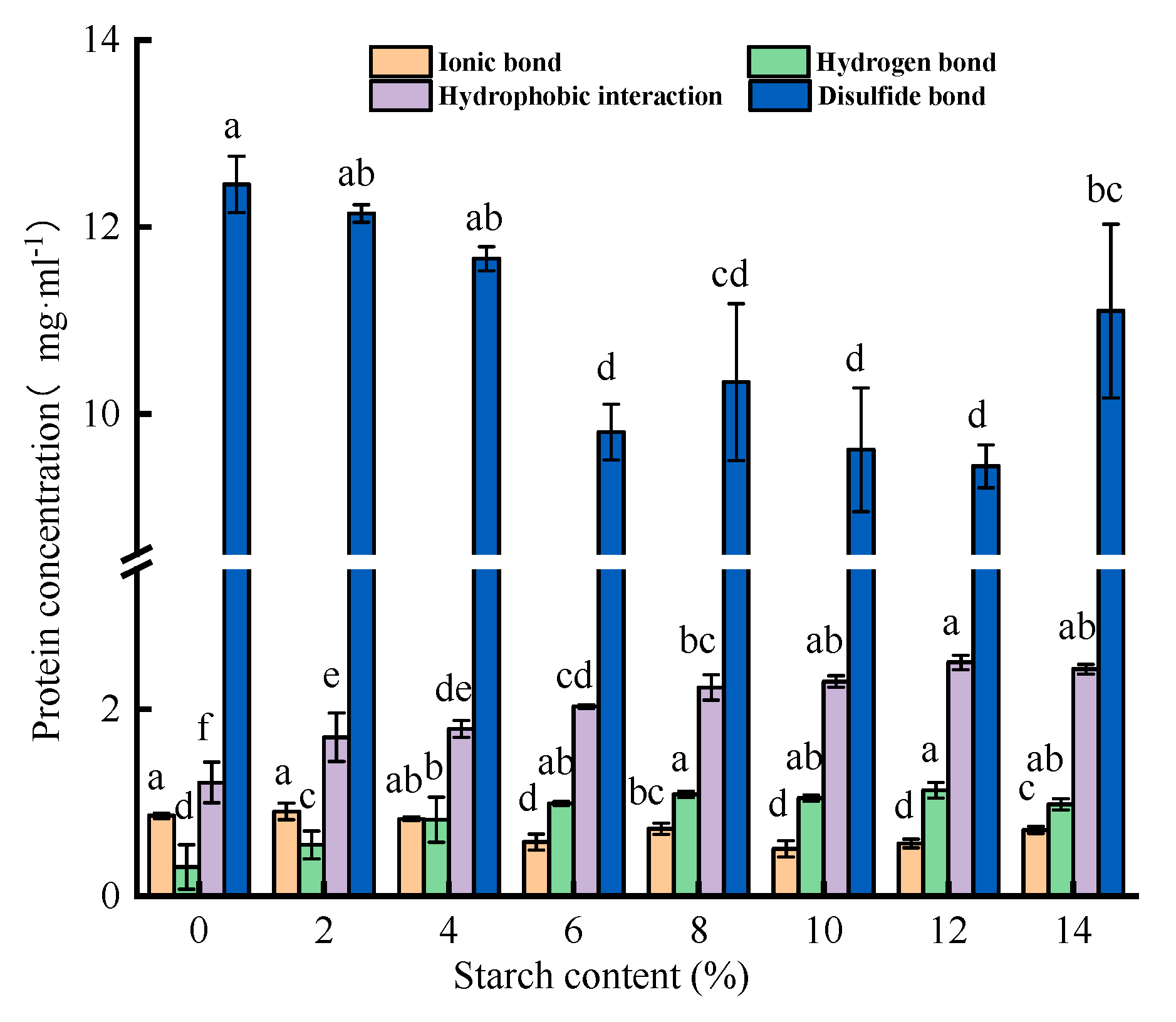

3.3.1. Chemical Interaction Forces

In general, heat exposure of myofibrillar protein induces the opening of its helical structure, with more sulfhydryl groups and hydrophobic amino acids exposed, thereby producing covalent crosslinking of disulfide bonds and hydrophobic interactions [

30].

Figure 5 shows that the disulfide bonds and hydrophobic interactions contributed more to surimi gel matrix maintenance, while ionic and hydrogen bonds contributed less. Tapioca starch decreased the disulfide and ionic bonds but promoted the hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bond formation (

P<0.05). Tapioca starch causes a loss of thiol group content by releasing hydroxyl groups and reacting with thiol groups, hindering the generation of disulfide bonds [

31]. Therefore, with the addition of tapioca starch, disulfide bonds showed a downward trend (

P<0.05). This conclusion is similar to previous findings that potato starch-induced reduction of disulfide bonds may be influenced by starch granular structure [

10]. During the heating process, tapioca starch binds to the thiol groups on myofibrillar protein and undergoes a non-disulfide bonding polymerization reaction [

32].

More importantly, exposure to hydrophobic sites in surimi proteins can enhance hydrophobic interactions, allowing proteins to aggregate with each other and thus induce gel network formation, which is significant for stabilizing the surimi matrix [

4,

10].

Figure 5 can intuitively show that the hydrophobic interaction continues to rise with the increase of tapioca starch, reaching a maximum value of surimi gel added 12% tapioca starch (from 1.21 mg/ml to 2.50 mg/ml). But when the addition of tapioca starch increased to 14%, hydrophobic interactions of surimi gel began to decline. On the one hand, the increase of tapioca starch addition results in a gradual increase in water absorption, and the water molecules in the surimi gel can be retained within a certain range, thus increasing the hydrophobic interaction. However, excessive water-absorbing prevents the dispersion or dissolution of the protein itself in water, which affects the hydrophobic interaction in the system to a certain extent [

33]. On the other hand, the hydroxyl groups in starch cross-connect with hydrophobic sites or other residues in myofibrillar protein molecules as fillers, increasing hydrophobic interactions [

4]. In addition, the amylopectin in tapioca starch can prevent the excessive unfolding of proteins and prevent the aggregation of hydrophobicity groups that lead to partial shielding of hydrophobic regions, thus increasing the surface hydrophobicity [

31]. The increase in surface hydrophobicity has a positive effect on the formation of hydrophobic interactions, prompting the gel to form a dense network structure and stronger WHC.

As shown in

Figure 5, tapioca starch enhanced the hydrogen bond in surimi gel to a certain extent (

P<0.05). As we all know, starch forms many hydrogen bonds during regeneration [

34]. However, hydrogen bonds play a major role in maintaining the steadiness of bound water and increasing the rigidity of surimi gels. Therefore, the formation of hydrogen bonds improves the texture properties in the surimi gel (

Table 1). In addition, tapioca starch weakens the production of ionic bonds. It may also be because starch hinders the formation of ionic bonds in the protein. Generally, tapioca starch addition was beneficial to increasing the hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interaction (

P<0.05), which enhanced the quality and stabilized network structure of the surimi gel.

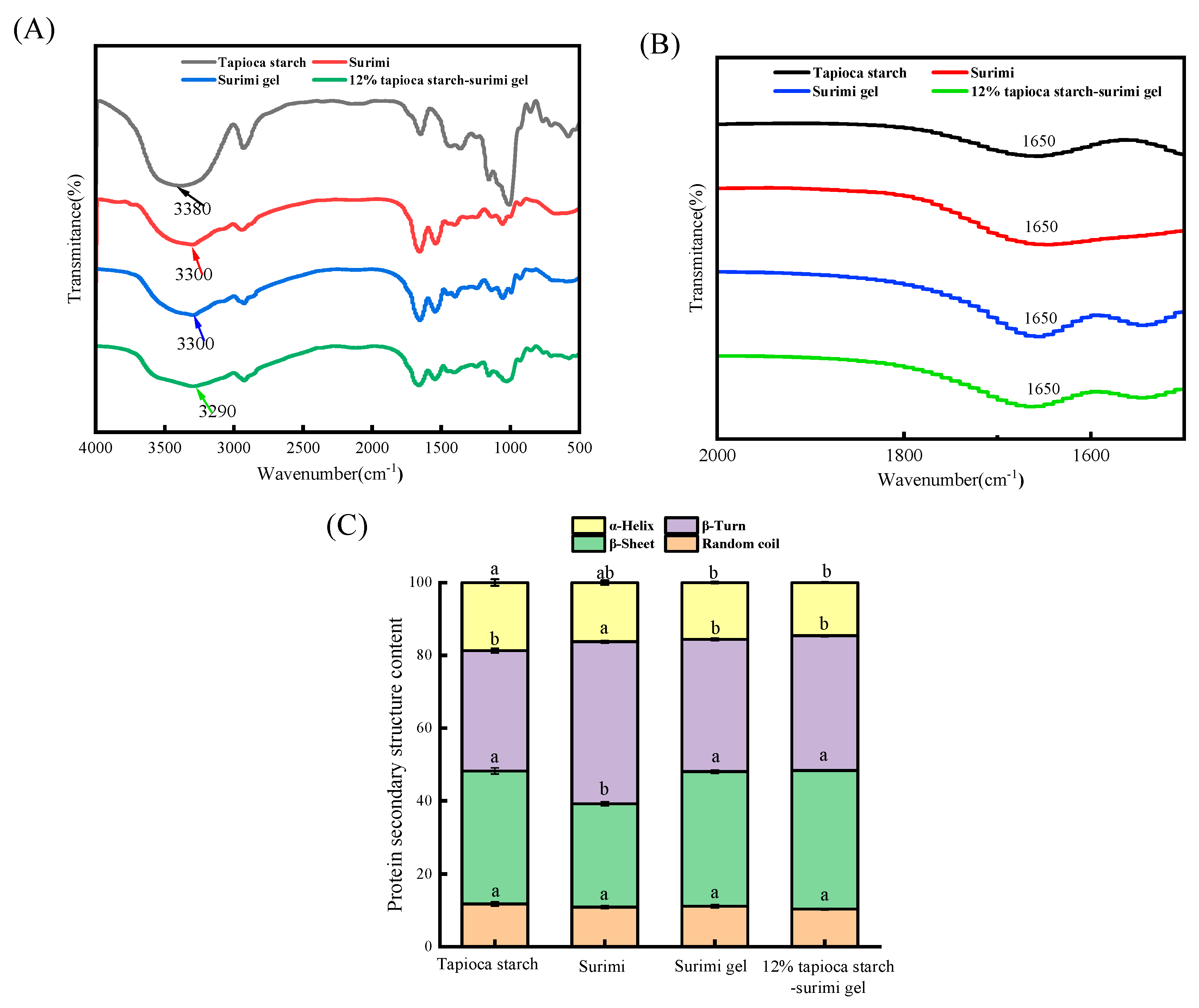

3.3.2. FT-IR Spectroscopic

Molecular interactions and structural changes in surimi gels were explored in depth using FTIR.

Figure 6A showed the FT-IR (4000-500 cm

-1) spectra of tapioca starch, surimi, surimi gel, and surimi gel supplemented with 12% tapioca starch. The 3500-3000 cm

-1 range is known as the amide A band, representing the stretching and vibrations of O-H and N-H, which are closely related to hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic bonds [

35]. The amide A band also can be used to determine the interaction between proteins and water molecules [

30]. The O-H elongation band peaks of tapioca starch, surimi, surimi gel, and surimi gel with 12% tapioca starch were located at 3387, 3300, 3300, and 3285 cm

-1, respectively. Data indicated that starch addition causes the surimi gel to move towards the lower wavenumber. Lower wavenumber is beneficial for the O-H to form intramolecular hydrogen bonds, which are closely linked to the binding ability of water molecules [

10]. Therefore, starch can change the water binding capacity in surimi gels. The conclusion echoes the rise of bound water in the surimi gel confirmed by the LF-NMR assay. On the one hand, it may be because starch heating exposes the O-H groups in the glucose molecule to bind to hydrophilic groups in the protein, thus forming more hydrogen bonds [

36]. On the other hand, during thermally induced gel, the protein structure unfolds and exposes hydrophobic amino acids, and the hydroxyl groups in the polysaccharide bind to hydrophobic amino acids (tyrosine, phenylalanine, and leucine), thus enhancing hydrophobic interactions in surimi gels [

37].

Figure 6B shows the amide II band in the range of 1600-1700 cm

-1, and the percentage content of the protein secondary structure was plotted by Peakfit 4.12 fitting (

Figure 6C). The peak bands of tapioca starch and surimi were shifted from 1650 cm

-1 wavenumber to 1670 cm

-1 and 1660 cm

-1, respectively. Surimi gel and surimi gel with 12% tapioca starch moved from 1650 cm

-1 to 1660 cm

-1 and 1670 cm

-1 wavenumber, indicating that the addition of starch into the surimi gel prompted the variation of α-helical structure into the β-turn and β-sheet. Compared to the surimi gel, the α-helix content of the surimi gel with 12% tapioca starch decreased from 15.62% to 14.61% (

P>0.05), while the relative β-turn and β-sheet content increased from 36.33% to 37.05% and 36.94% to 37.99% (

P>0.05), respectively. Thus, starch molecules induced the unfolding of the myofibrillar protein, enhanced hydrogen bonds, and hydrophobic interactions, contributed to the α-helix to β-turn and β-sheet shift of the surimi gel, finally leading to a red-shift of the peak of the amide I band in the surimi gel [

38]. It has been proved that the gel strength of myofibrillar protein is positively related to the amount of β-sheet, β-turning, and random coil but negatively related to the amount of α-helix [

39]. The cause of this change should be the interaction between myofibrillar protein molecules. The increased β-sheet and β-turn also indicate an orderly change in the protein network structure [

38]. The transformation of the protein structure in surimi gel was consistent with the results of surimi gel microstructure changes.

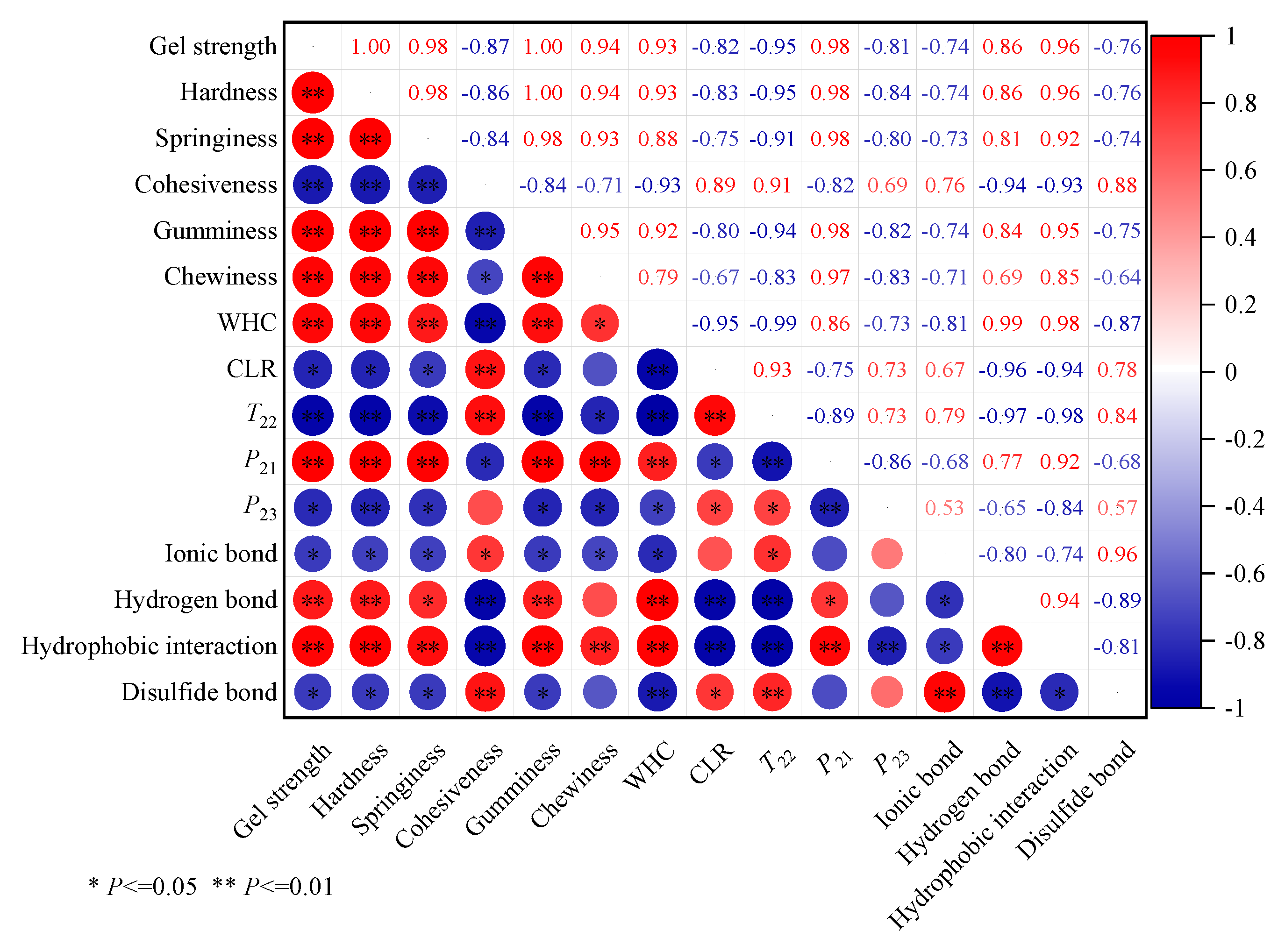

3.3. Correlation Analysis

The relationship between gel texture properties, moisture distribution status, and molecular interaction forces of tapioca starch-surimi gel was further elucidated by correlation analysis. As shown in

Figure 7, the correlation index between the gel strength, hardness, springiness, gumminess, and chewiness of surimi gel was close to 1.000, indicating a particularly pronounced positive relation between them (

P<0.01). At the same time, in terms of moisture distribution status, the correlation index between gel strength, hardness, springiness, gumminess, chewiness, and WHC and bound water were 0.930 and 0.980, reflecting a particularly pronounced positive related (

P<0.01). However, there was a pronounced negative related to CLR, free water, and relaxation time (

T22) (

P<0.05). It was further proved that tapioca starch can reduce the free water in surimi gel, and water molecules can be stably in the gel matrix to form a compact gel network structure, which helps to improve the gel quality. In addition, the gel strength, WHC, and springiness were positively correlated with hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions (R=0.900,

P<0.01) and negatively related to ionic bonds and disulfide bonds (

P<0.05). It can be concluded that the change of texture properties in surimi gel was related to the molecular interaction forces, and the increased hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions were more favorable to improving the quality of surimi gel.

4. Conclusions

The tapioca starch-filled surimi gel was developed. The tapioca starch improved the hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions in the surimi gel system and promoted the thermally induced conformational transition of surimi gels from α-helix to β-sheet. Finally, a compact and ordered three-dimensional gel network structure is obtained. The excellent gel network structure endowed surimi gels with enhanced WHC and texture characteristics. Therefore, tapioca starch filling is a useful strategy to optimize the gel quality of surimi gel. This research will provide a theoretical basis for the development of high-quality surimi gel products.

Author Contributions

Carried out experiments, wrote initial manuscript and revised the first draft in response to the comments of others, X.H.; Put forward suggestions for revision of the first draft, and proofread of the revised manuscripts, including grammar and content, C.Z. and Q.L.; Oversight and leadership responsibility for the research activity planning and execution, C.Z.; Put forward important suggestions for revision of the first draft, P.W., C.S., H.M. and P.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported financially by the Innovation and Development Project about Marine Economy Demonstration of Zhanjiang City (Nos. XM-202008-01B1); the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhanjiang) (Nos. ZJW-2019-07); Guangdong Province Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System Innovation Team Building Project (2023KJ150); Research, development and industrialization of key technologies for prefabricated golden pomfret processing in Zhanjiang City (2022A05037).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yi, M.; Hsu, K.; Wang, J.; Feng, B.; Lin, H.; Yan, Y. Genetic structure and diversity of the yellowbelly threadfin bream nemipterus bathybius in the northern south china sea. Diversity 2021, 13, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Que, F.; Li, X.; Shi, L.; Deng, W.; Fu, X.; Xiong, G.; Sun, J.; Wang, L.; Xiong, S. Effects of enzymatic konjac glucomannan hydrolysates on textural properties, microstructure, and water distribution of grass carp surimi gels. Foods 2022, 11, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Qin, Y.; Feng, A.; He, Y.; Zhou, D.; Dong, X.; Shen, X.; Cao, J.; Li, C. Sweet potato starch addition together with partial substitution of tilapia flesh effectively improved the golden pompano (Trachinotus blochii) surimi quality. J Texture Stud 2021, 52, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Yi, S.; Li, X.; Li, J. The interaction of starch-gums and their effect on gel properties and protein conformation of silver carp surimi. Food Hydrocolloid 2021, 112, 106290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Guo, C.; Lin, L.; Si, Y.; Gao, X.; Xu, D.; Jia, R.; Yang, W. Combined use of rheology, LF-NMR, and MRI for characterizing the gel properties of hairtail surimi with potato starch. Food Bioprocess Tech 2020, 13, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Katano, T.; Yoshimoto, Y.; Gao, Y.; Watanabe, Y.; Nakazawa, N.; Osako, K.; Okazaki, E. Sweet potato starch with low pasting temperature to improve the gelling quality of surimi gels after freezing. Food Hydrocolloid 2018, 81, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Chen, Q.; Xiao, N.; Du, Y.; Feng, Q.; Shi, W. Changes in gel structure and chemical interactions of hypophthalmichthys molitrix surimi gels: Effect of setting process and different starch addition. Foods 2022, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, H.; Wang, C.; Su, Q.; Li, X.; Yi, S.; Li, J. The effect of modified starches on the gel properties and protein conformation of nemipterus virgatus surimi. J Texture Stud 2019, 50, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Huang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Wang, K.; Prakash, S.; Zhu, B. Investigation of sweet potato starch as a structural enhancer for three-dimensional printing of Scomberomorus niphonius surimi. J Texture Stud 2019, 50, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhao, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, W.; Huang, J.; Fan, D.; Zhang, H. Improvement of the quality of surimi products with overdrying potato starches. J Food Quality 2017, 2017, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Kang, X.; Zhou, X.; Tong, L.; Yu, W.; Zhang, J.; Yang, W.; Lou, Q.; Huang, T. Glycosylation fish gelatin with gum Arabic: Functional and structural properties. LWT 2021, 139, 110634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisenga, S.M.; Workneh, T.S.; Bultosa, G.; Alimi, B.A. Progress in research and applications of cassava flour and starch: a review. Journal of food science and technology 2019, 56, 2799–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Fang, L.; Wang, C.; Shi, L.; Chang, T.; Yang, H.; Cui, M. Effects of starches on the textural, rheological, and color properties of surimi-beef gels with microbial tranglutaminase. Meat Sci 2013, 93, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, W.; Zhang, T.; Feng, D.; Xue, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, W.; Xue, C. Effects of modified starches on the gel properties of alaska pollock surimi subjected to different temperature treatments. Food Hydrocolloid 2016, 56, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Jia, R.; Gao, Y.; Yang, W.; Tong, J.; Xia, G. Effects of innovative gelation and modified tapioca starches on the physicochemical properties of surimi gel during frozen storage. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2022, 57, 6591–6601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Lin, Y.; Hong, P.; Liu, H.; Zhou, C. Compare with different vegetable oils on the quality of the Nemipterus virgatus surimi gel. Food Sci Nutr 2022, 10, 2935–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; Chen, N.; Gao, P.; Yu, D.; Yang, F.; Xu, Y.; Xia, W. Influence of L-arginine addition on the gel properties of reduced-salt white leg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) surimi gel treated with microbial transglutaminase. LWT 2023, 173, 114310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Jiang, Q.; Gao, P.; Yu, D.; Yang, F.; Xu, Y.; Xia, W. Gel properties, physicochemical properties, and sensory attributes of white leg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) surimi gel treated with sodium chloride (NaCl) substitutes. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2023, 58, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Katano, T.; Yoshimoto, Y.; Gao, Y.; Nakazawa, N.; Osako, K.; Okazaki, E. Effect of small granules in potato starch and wheat starch on quality changes of direct heated surimi gels after freezing. Food Hydrocolloid 2020, 104, 105732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Patino, J.M.; Pilosof, A.M.R. Protein-polysaccharide interactions at fluid interfaces. Food Hydrocolloid 2011, 25, 1925–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, S.; Kim, J.; Son, B.; You, D.H.; Han, J.M.; Oh, J.; Kim, B.; Kong, C. Effects of carrageenan on the gelatinization of salt-based surimi gels. Fisheries and aquatic sciences 2013, 16, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; He, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Ai, C.; Cao, H.; Xiao, J.; El-Seedi, H.; Chen, L.; Teng, H. Effect of carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) on some physico-chemical and mechanical properties of unrinsed surimi gels. LWT 2023, 180, 114653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.L.; Liang, Y.; Tan, C.P.; Lu, Y.M.; Cui, B. Research on the water-holding capacity of pork sausage with acetate cassava starch. Starch - Stärke 2014, 66, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Guo, X.; Lin, J.; Sun, P.; Ren, X.; Xu, W.; Tong, Y.; Li, D. Effect and synergy of different exogenous additives on gel properties of the mixed shrimp surimi (Antarctic krill and white shrimp). International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2022, 57, 5338–5348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Lin, Y.; Hong, P.; Liu, H.; Zhou, C. Low-content pre-emulsified safflower seed oil enhances the quality and flavor of the nemipterus virgatus surimi gel. Gels 2022, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang Xinbo; Han Minyi; Bai Yun; Liu Yafu; Xing Lujuan; Xu Xinglian; Guanghong, Z. Insight into the mechanism of myofibrillar protein gel improved by insoluble dietary fiber. Food Hydrocolloid 2018, 74, 219–226. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Han, M.; Jiang, X.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, C.; Xu, X.L.; Zhou, G.H. The effects of insoluble dietary fiber on myofibrillar protein gelation: Microstructure and molecular conformations. Food Chem 2019, 275, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravelle, A.J.; Marangoni, A.G.; Barbut, S. Insight into the mechanism of myofibrillar protein gel stability: Influencing texture and microstructure using a model hydrophilic filler. Food Hydrocolloid 2016, 60, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S. Effect of pullulan on gel properties of Scomberomorus niphonius surimi. Int J Biol Macromol 2016, 93, 1118–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lin, S.; Jiang, P.; Bao, Z.; Li, S.; Sun, N. Insight into the gel properties of antarctic krill and pacific white shrimp surimi gels and the feasibility of polysaccharides as texture enhancers of antarctic krill surimi gels. Foods 2022, 11, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, R.; Fan, X.; He, G.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Han, M.; Ullah, N. , et al. Changes in the quality of myofibrillar protein gel damaged by high doses of epigallocatechin-3-gallate as affected by the addition of amylopectin. Foods 2023, 12, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Du, Q.; Fan, X.; Zhou, C.; He, J.; Sun, Y.; Xia, Q.; Pan, D. Interaction between kidney-bean polysaccharides and duck myofibrillar protein as affected by ultrasonication: Effects on gel properties and structure. Foods 2022, 11, 3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu Weiwei; Wu Di; Wang LiMei; Song Geyao; Chi Rongshuo; Ma Jing; Li Zhenshun; Wang Lan; Weiqing, S. Properties of pork myofibrillar protein: A water distribution, microstructure and intermolecular interactions study. Food Chem 2023, 411, 135386. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Guo, J.; Lian, X.; Wang, H. Effects of amylopectins from five different sources on disulfide bond formation in alkali-soluble glutenin. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, R.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G.; Liu, D. Structural modification by high-pressure homogenization for improved functional properties of freeze-dried myofibrillar proteins powder. Food Res Int 2017, 100, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Barón, N.; Gu, Y.; Vasanthan, T.; Hoover, R. Plant proteins mitigate in vitro wheat starch digestibility. Food Hydrocolloid 2017, 69, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Xue, C. Effects of konjac glucomannan on heat-induced changes of physicochemical and structural properties of surimi gels. Food Res Int 2016, 83, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, W.; Hu, Q.; Qu, M.; Sun, B.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Xia, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, X. Impact of Insoluble dietary fiber and CaCl2 on structural properties of soybean protein isolate-wheat gluten composite gel. Foods 2023, 12, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou Xuxia; Jiang Shan; Zhao Dandan; Zhang Jianyou; Gu Saiqi; Pan Zhiyan; Yuting, D. Changes in physicochemical properties and protein structure of surimi enhanced with camellia tea oil. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2017, 84, 562–571. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Effect of different contents of tapioca starch on the WHC and CLR of surimi of the surimi gel.

Figure 1.

Effect of different contents of tapioca starch on the WHC and CLR of surimi of the surimi gel.

Figure 2.

Effect of different contents of tapioca starch on the spin-spin relaxation times of surimi gel (A). Relative area percentages of T21, T22, and T23 peaks (B).

Figure 2.

Effect of different contents of tapioca starch on the spin-spin relaxation times of surimi gel (A). Relative area percentages of T21, T22, and T23 peaks (B).

Figure 3.

Effect of different contents of tapioca starch on the light microscopic picture (×200) and pore size distribution of surimi gels. (A): control; (B-H): the surimi gel containing tapioca starch in concentrations of 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 per 100 g of surimi, respectively; I: Average cavities of surimi gel with different content of tapioca starch.

Figure 3.

Effect of different contents of tapioca starch on the light microscopic picture (×200) and pore size distribution of surimi gels. (A): control; (B-H): the surimi gel containing tapioca starch in concentrations of 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 per 100 g of surimi, respectively; I: Average cavities of surimi gel with different content of tapioca starch.

Figure 4.

Effects of different contents of tapioca starch on the scanning electron microscope photograph (×15 000) of the surimi gel. (A): control; (B-H): the surimi gel containing tapioca starch in the concentrations of 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 per 100 g of surimi, respectively.

Figure 4.

Effects of different contents of tapioca starch on the scanning electron microscope photograph (×15 000) of the surimi gel. (A): control; (B-H): the surimi gel containing tapioca starch in the concentrations of 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 per 100 g of surimi, respectively.

Figure 5.

Effect of different contents of tapioca starch on the chemical force of the surimi gel.

Figure 5.

Effect of different contents of tapioca starch on the chemical force of the surimi gel.

Figure 6.

FT-IR spectral of tapioca starch, surimi, surimi gel, and tapioca starch-surimi gel (tapioca starch content of 12%) (A-B), and the change of secondary structure (C).

Figure 6.

FT-IR spectral of tapioca starch, surimi, surimi gel, and tapioca starch-surimi gel (tapioca starch content of 12%) (A-B), and the change of secondary structure (C).

Figure 7.

Correlation analysis between gel strength of surimi gel and other indexes.

Figure 7.

Correlation analysis between gel strength of surimi gel and other indexes.

Table 1.

Effects of different contents of tapioca starch on texture of the surimi gel.

Table 1.

Effects of different contents of tapioca starch on texture of the surimi gel.

| Tapioca starch (g per 100 g) |

Gel strength/N |

Hardness/N |

Springiness |

Cohesiveness |

Gumminess |

Chewiness |

| 0 |

7.59±0.02g

|

12.61±0.58g

|

0.77±0.00c

|

0.66±0.00a

|

8.64±0.11f

|

6.66±0.08d

|

| 2 |

8.51±0.11f

|

13.95±0.21f

|

0.78±0.00c

|

0.65±0.00ab

|

9.07±0.43f

|

6.99±0.42d

|

| 4 |

10.13±0.22e

|

15.48±0.15e

|

0.77±0.01c

|

0.65±0.01abc

|

10.19±0.09e

|

7.90±0.17d

|

| 6 |

11.75±0.19d

|

17.64±0.36d

|

1.01±0.34bc

|

0.65±0.00bcd

|

11.47±0.41d

|

9.97±0.69c

|

| 8 |

14.06±0.20c

|

19.69±0.69c

|

1.20±0.33ab

|

0.64±0.00d

|

12.65±0.45c

|

10.77±0.38c

|

| 10 |

15.17±0.31b

|

20.69±0.29b

|

1.21±0.32ab

|

0.64±0.01cd

|

13.53±0.22b

|

18.79±0.40b

|

| 12 |

17.48±0.23a

|

24.00±0.55a

|

1.41±0.01a

|

0.64±0.00d

|

15.42±0.33a

|

21.36±1.13a

|

| 14 |

17.27±0.10a

|

23.47±0.03a

|

1.40±0.00ab

|

0.65±0.00bcd

|

15.26±0.09a

|

21.54±0.23a

|

Table 2.

Effects of different contents of tapioca starch on relaxation time (T2) of the surimi gel.

Table 2.

Effects of different contents of tapioca starch on relaxation time (T2) of the surimi gel.

| Tapioca starch (g per 100 g) |

T2B |

T22 |

T23

|

| 0 |

2.36±0.24ab

|

44.49±0.00a

|

784.70±31.81a

|

| 2 |

2.97±0.21a

|

41.50±0.00b

|

309.09±73.66c

|

| 4 |

2.12±0.64bc

|

36.12±0.00c

|

459.16±16.99b

|

| 6 |

1.48±0.10c

|

33.70±0.00d

|

472.95±65.86b

|

| 8 |

1.66±0.65bc

|

31.44±0.00e

|

483.43±37.82b

|

| 10 |

1.64±0.06bc

|

30.74±1.22e

|

322.37±18.63c

|

| 12 |

1.82±0.43bc

|

28.67±1.13f

|

460.15±39.17b

|

| 14 |

1.81±0.39bc

|

29.33±0.00f

|

465.42±43.12b

|

Table 3.

Effects of different contents of tapioca starch addition on whiteness of the surimi gel.

Table 3.

Effects of different contents of tapioca starch addition on whiteness of the surimi gel.

| Tapioca starch (g per 100 g) |

L* |

a* |

b* |

Whiteness |

| 0 |

71.68±0.17a

|

-2.51±0.03a

|

5.17±0.19a |

71.10±0.20a |

| 2 |

70.21±0.33b

|

-2.73±0.02bc

|

4.24±0.11b |

69.78±0.34b |

| 4 |

68.57±0.11c

|

-2.81±0.05cd

|

4.04±0.18bc |

68.18±0.12c |

| 6 |

66.59±0.06d

|

-2.85±0.05d

|

3.79±0.14cd |

66.25±0.06d |

| 8 |

65.31±0.06e

|

-2.83±0.06d

|

3.49±0.14e |

65.01±0.05e |

| 10 |

64.01±0.07f

|

-2.79±0.05cd

|

3.38±0.03e |

63.74±0.06f |

| 12 |

62.59±0.45g

|

-2.81±0.01cd

|

3.53±0.12de |

62.32±0.44g |

| 14 |

62.00±0.16h

|

-2.66±0.06b

|

3.48±0.27e |

61.75±0.18h |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).