Submitted:

15 November 2023

Posted:

15 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

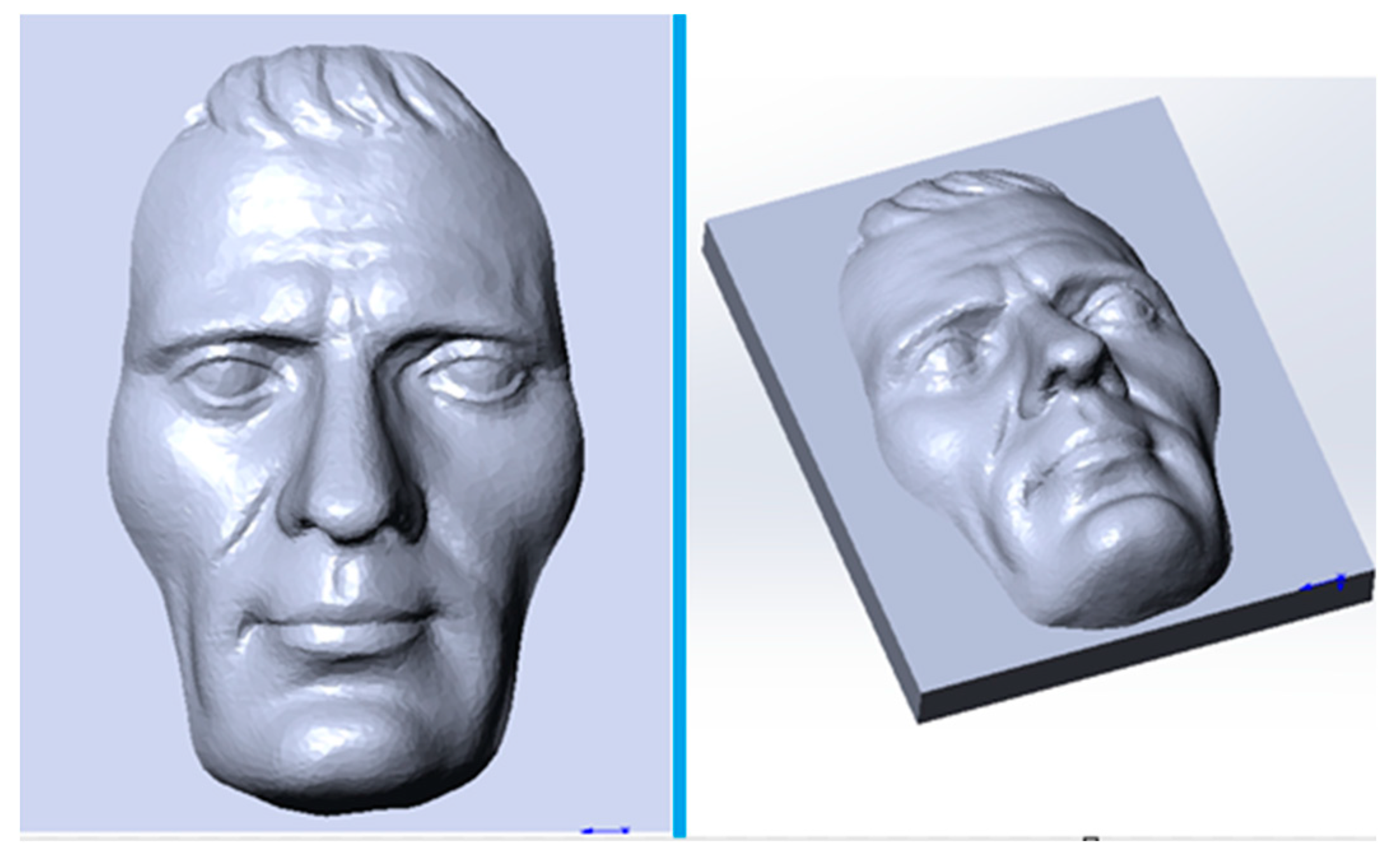

2. Materials and Methods

- Roughing—face cylindrical cutter D18 mm, axial depth of cut ap = 1 mm, radial depth of cut ae = 0.6 mm, tool path tolerance T = 0.1 mm, surface allowance P = 0.5 mm

- Pre-finishing—copy cutter D6 mm, cutting material HSS Co8, machining strategy—linear, axial depth of cut ap = 0.5 mm, radial depth of cut ae = 0.5 mm, surface allowance P = 0.2 mm

- Finishing—copy cutter D4 mm, cutting material HSS Co8, machining strategy—constant Z, radial depth of cut ae = 0.2 mm, tool path tolerance T = 0.01 mm

- Comparison of machined surfaces between CAM system and real production

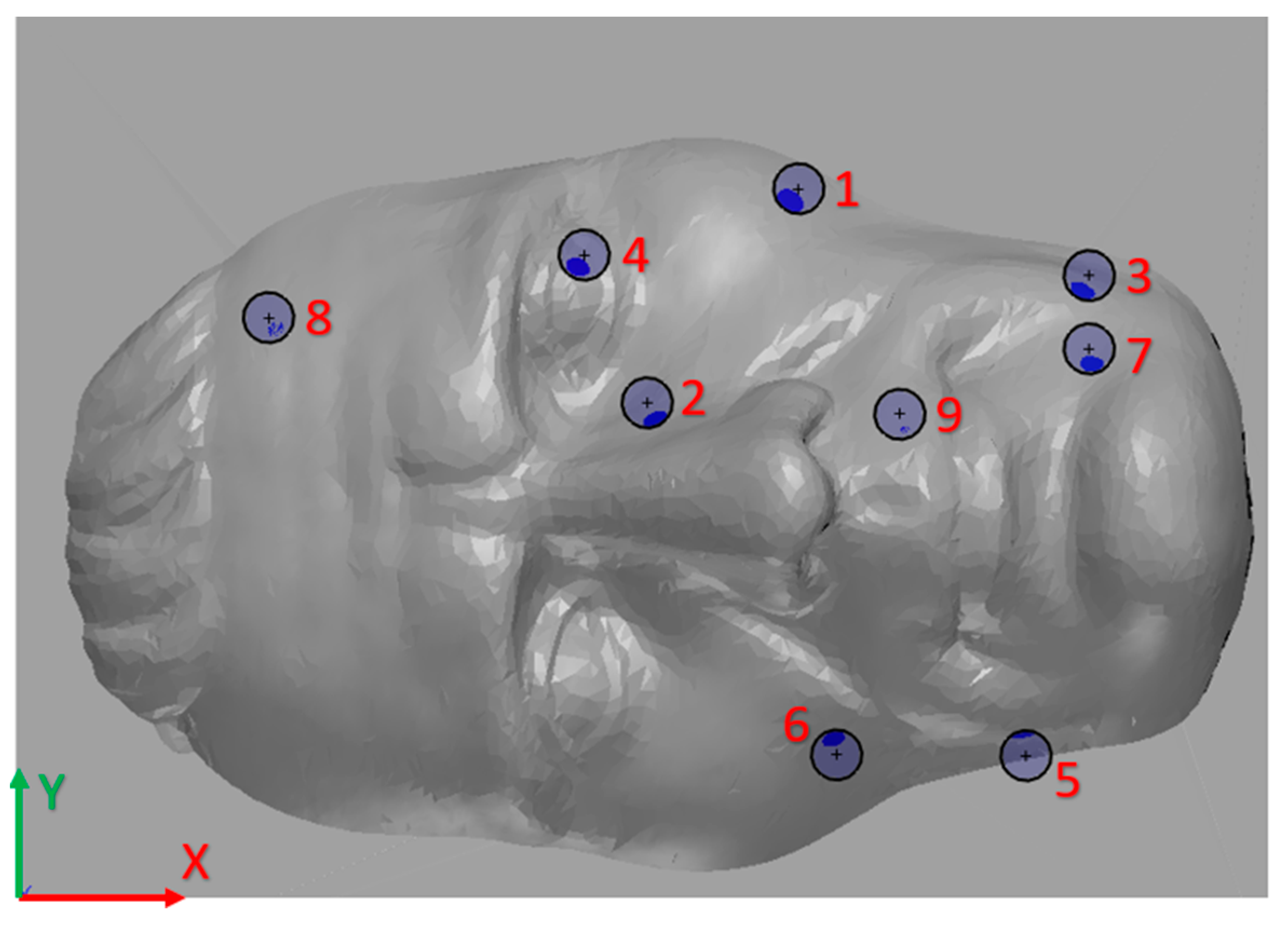

- Evaluation of the effective diameter of the tool Deff with respect to the contact of the tool and the workpiece

- Evaluation of tool surface area distribution using areal content and volume data extraction at the contact patch location

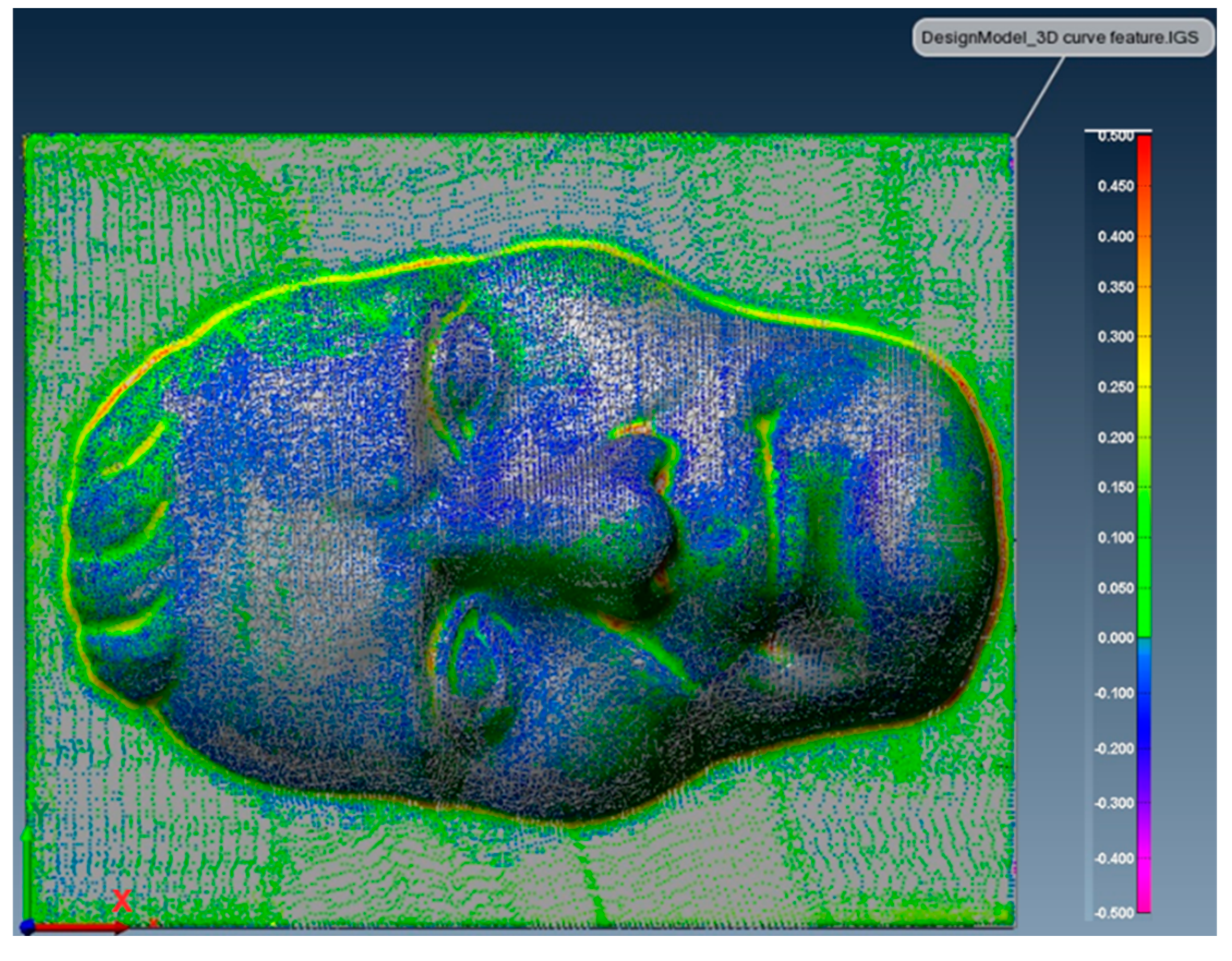

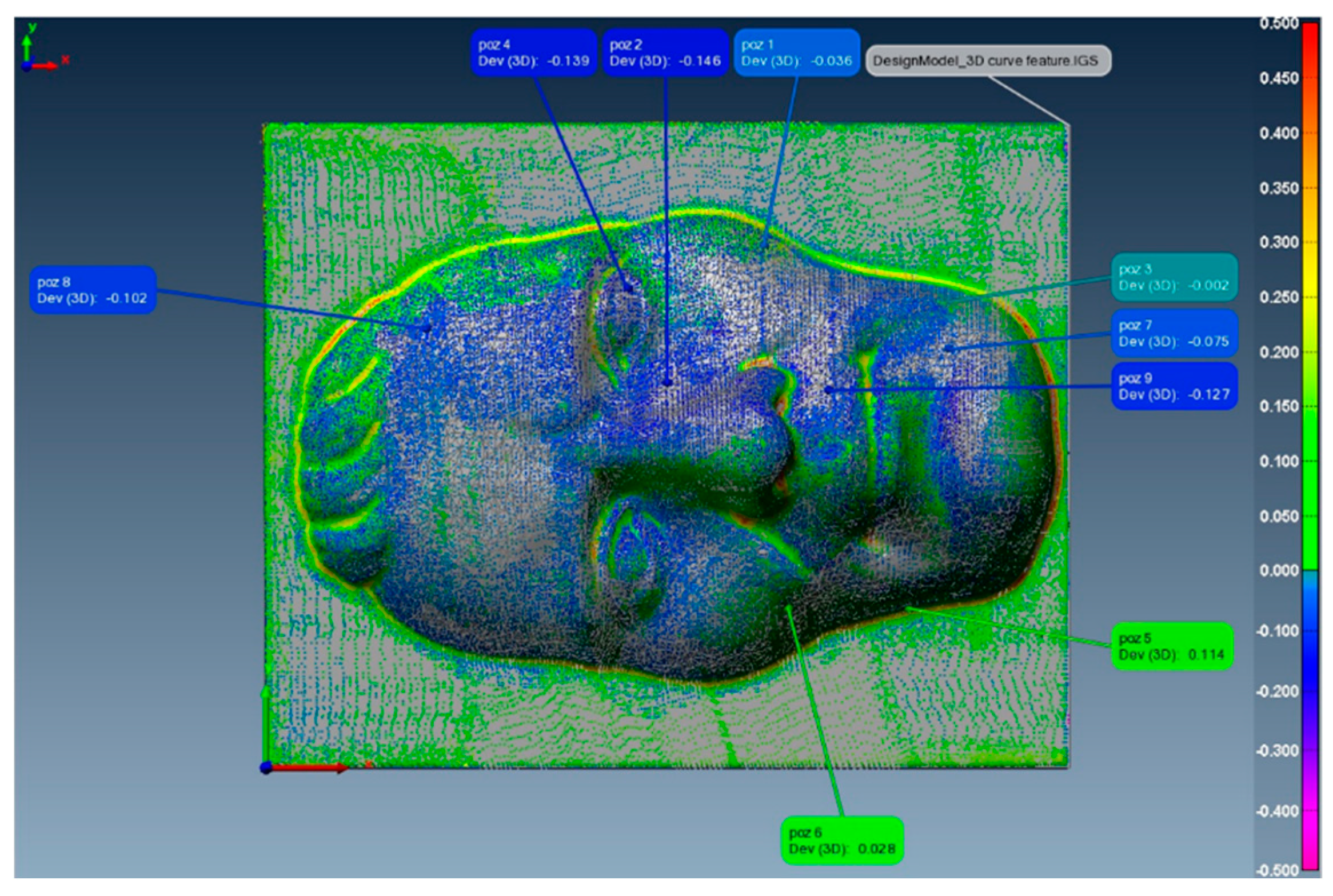

- Assessment of surface deviations by the 3D scanning method—scanner FARO Laser ScanArm V3 (FARO Technologies Italy S.r.l)

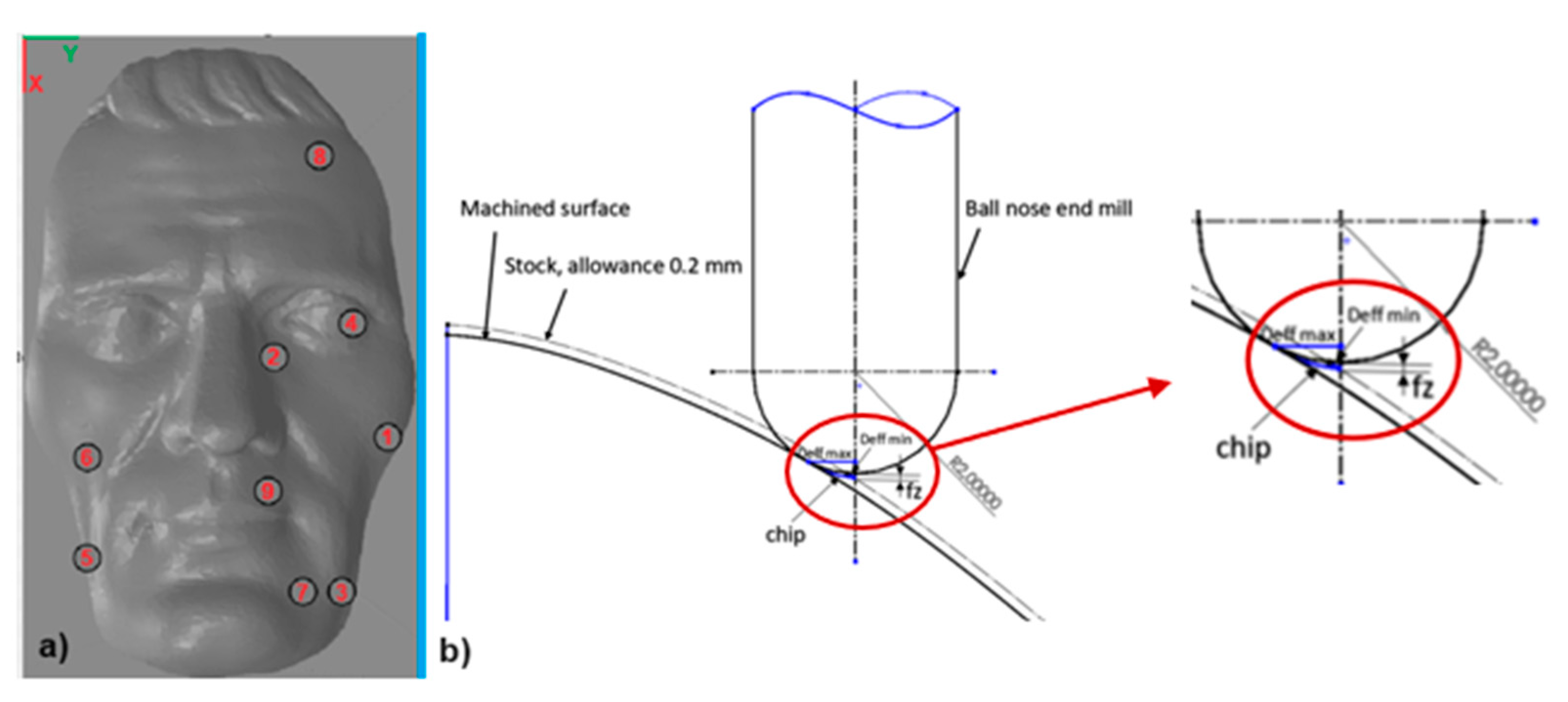

2.1. Methodology for evaluating the effective diameter of the tool with regard to the contact between the tool and the workpiece

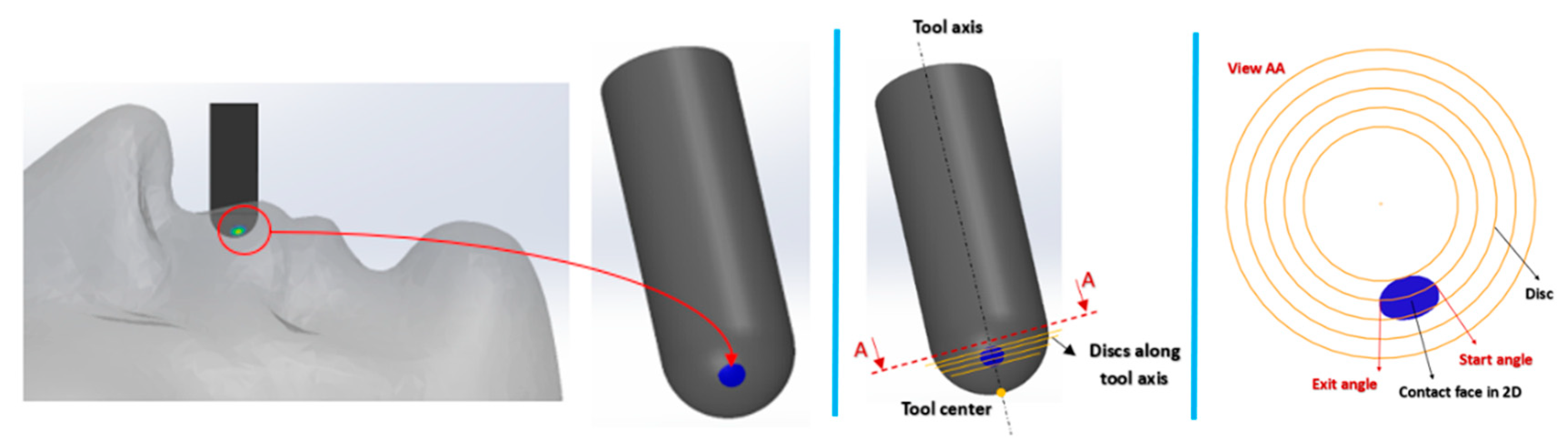

2.2. Methodology for assessing the distribution of the engagement area on the tool surface

2.3. Methodology for evaluating surface deviations using the scanning method

3. Results

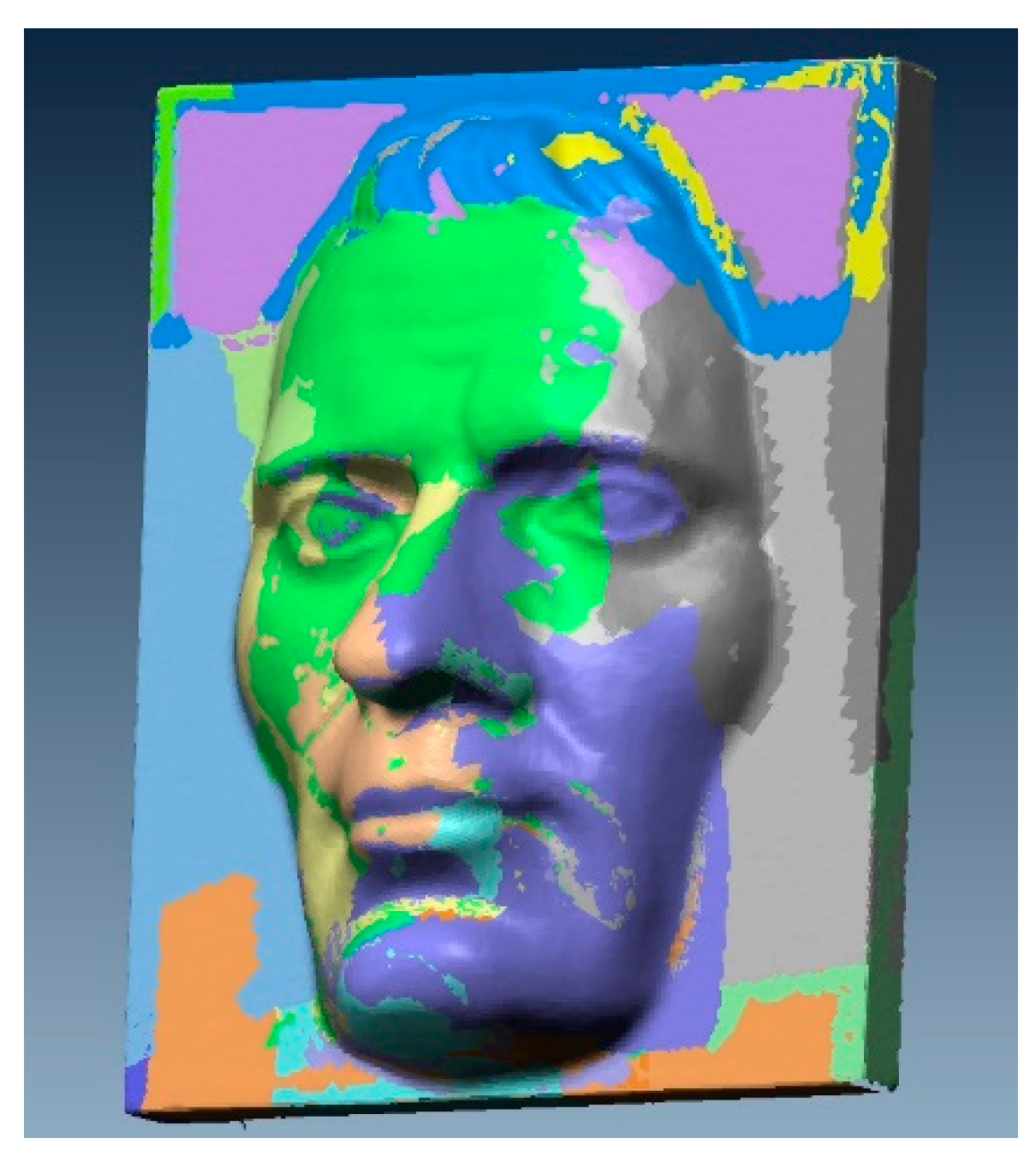

3.1. Comparison of machined surfaces between CAM system and real production

3.2. Evaluation of the effective diameter of the tool Deff with respect to the contact of the tool and the workpiece

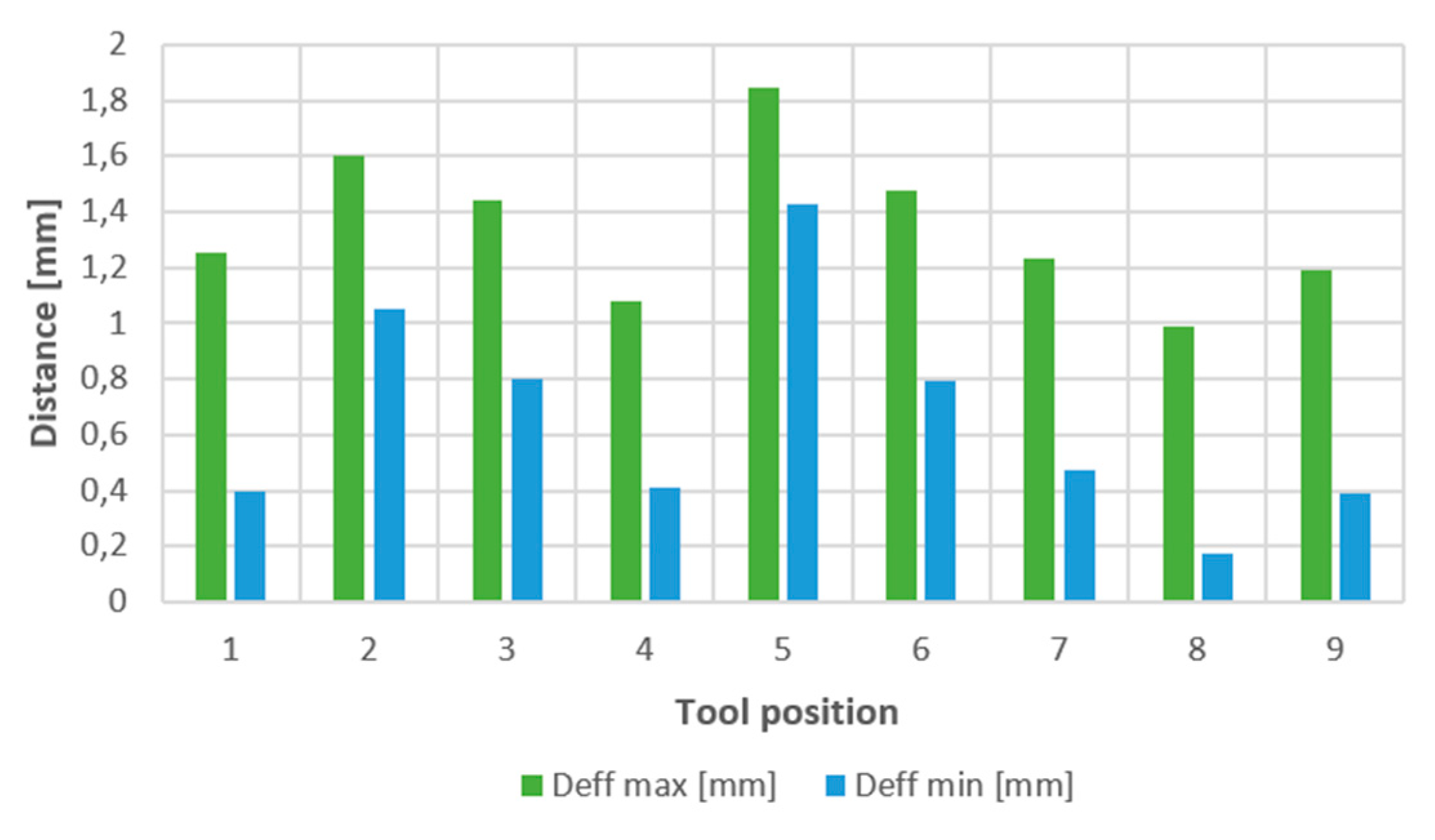

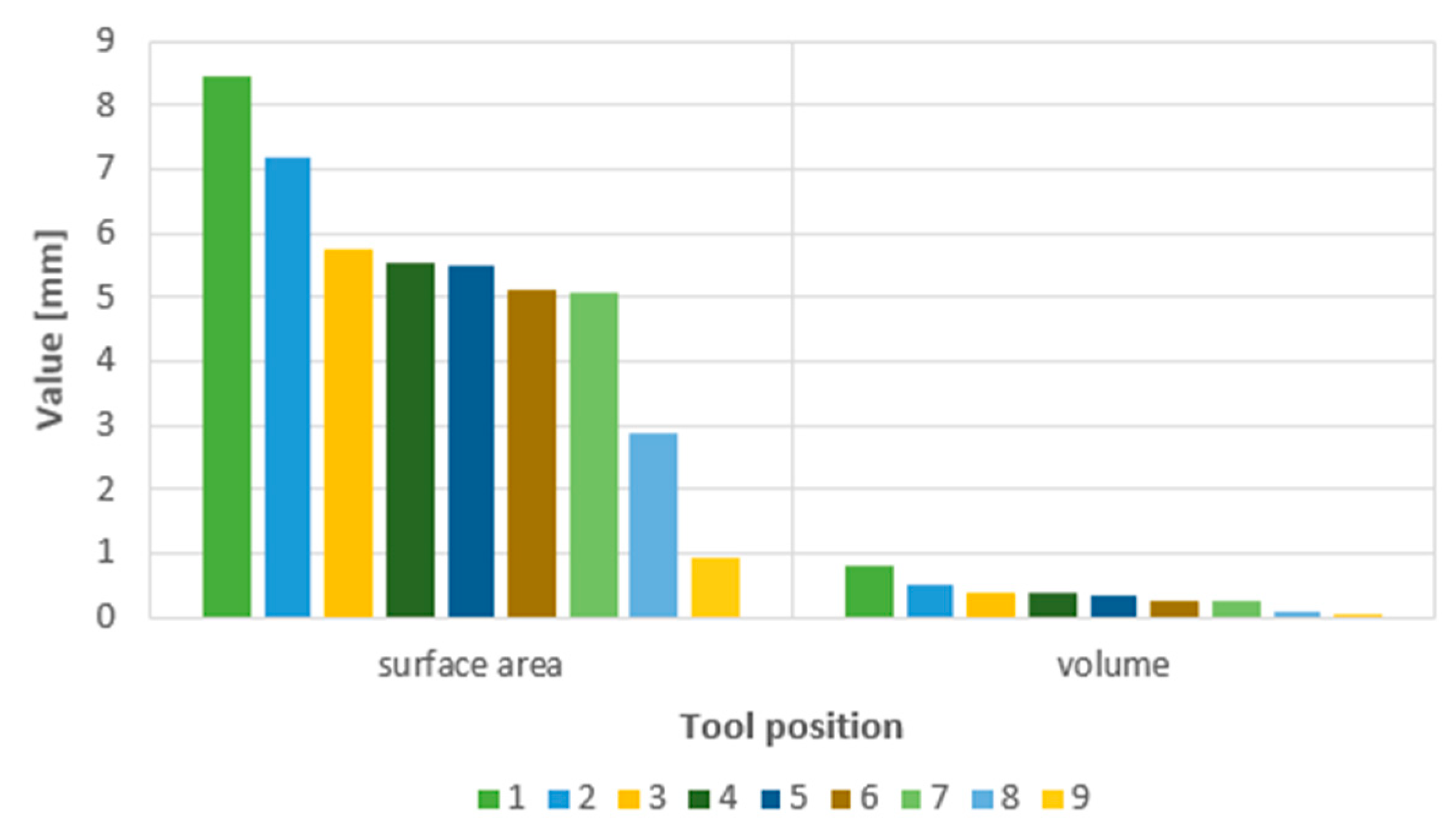

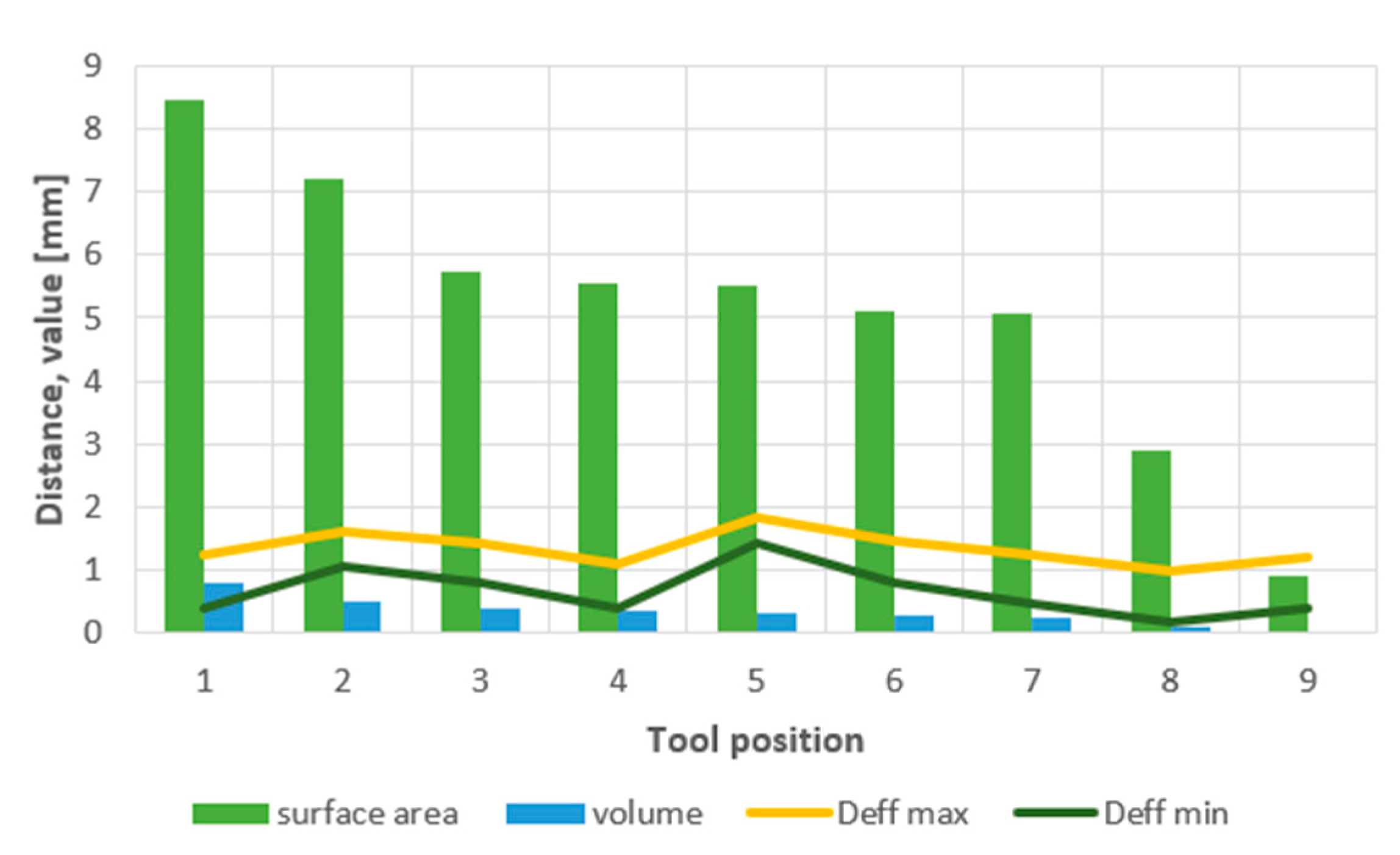

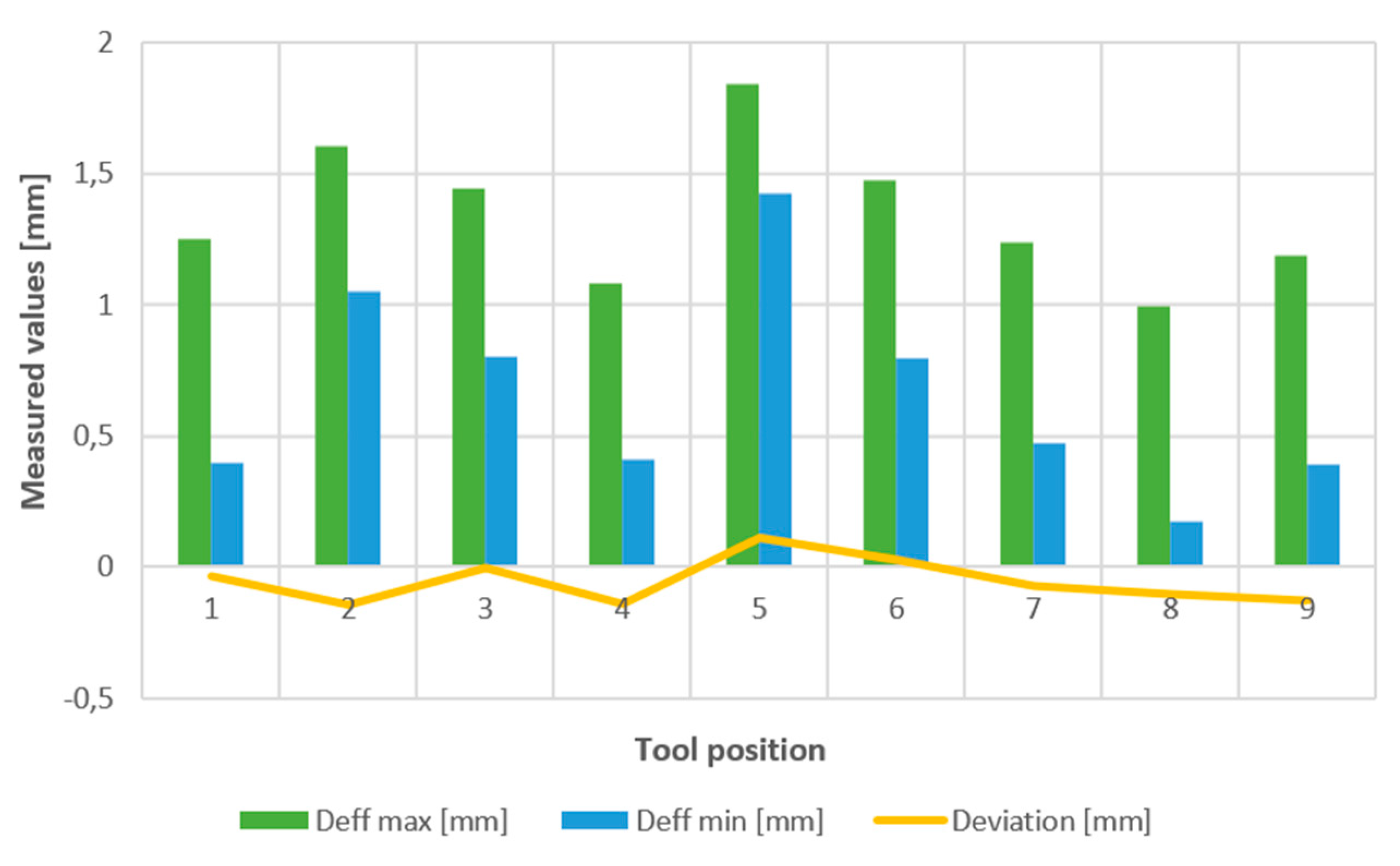

3.3. Evaluating tool surface area distribution using data extraction

3.4. Evaluation of surface deviations by the 3D scanning method

4. Discussion

- The most significant difference with respect to Deff max and Deff min for a specific position of the instrument was manifested in the position of instrument No. 8. Within this interaction of the tool with the workpiece, the Deff min parameter was almost 6 times smaller compared to the Deff max value. The smallest difference ratio was recorded in the position of tool No. 2.

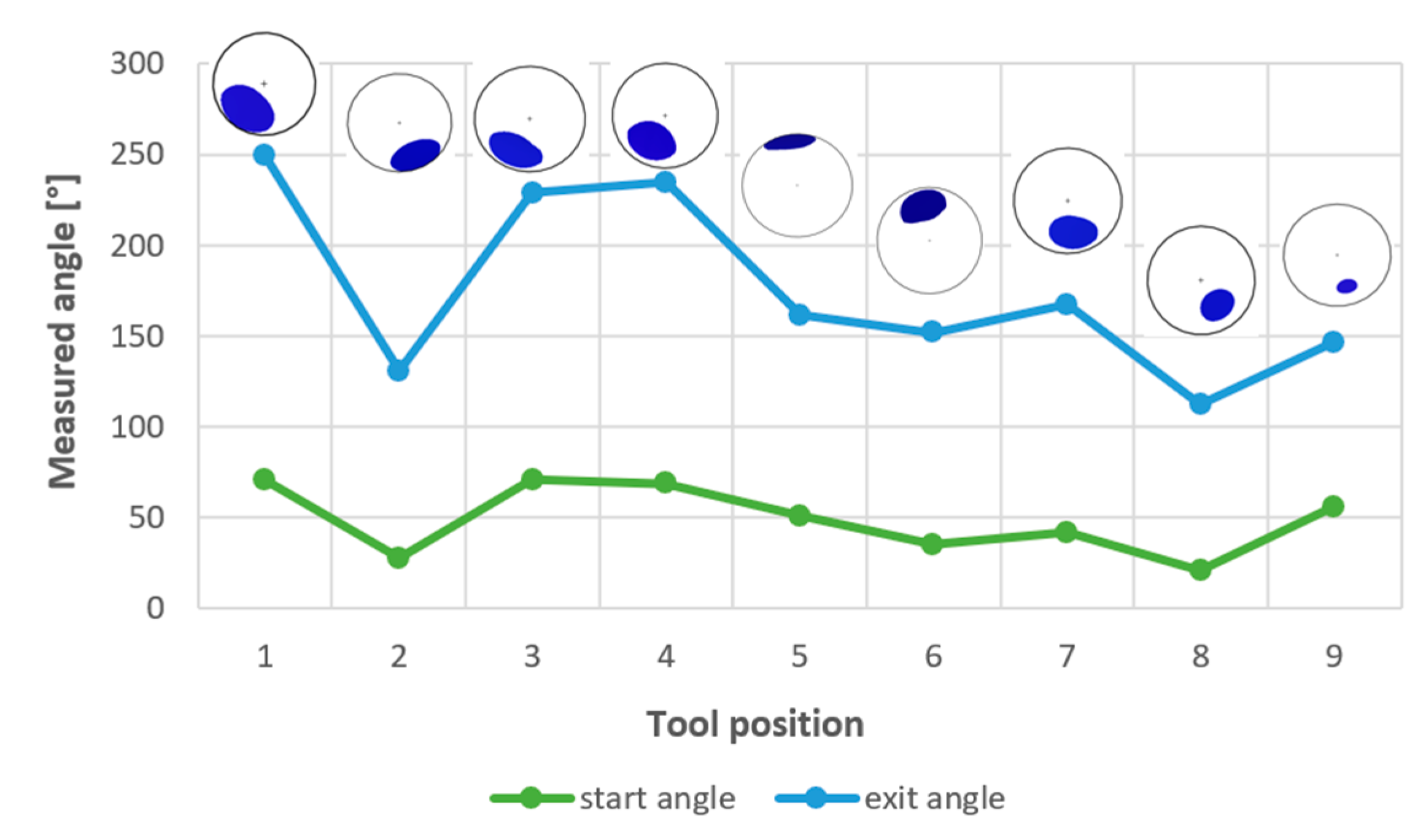

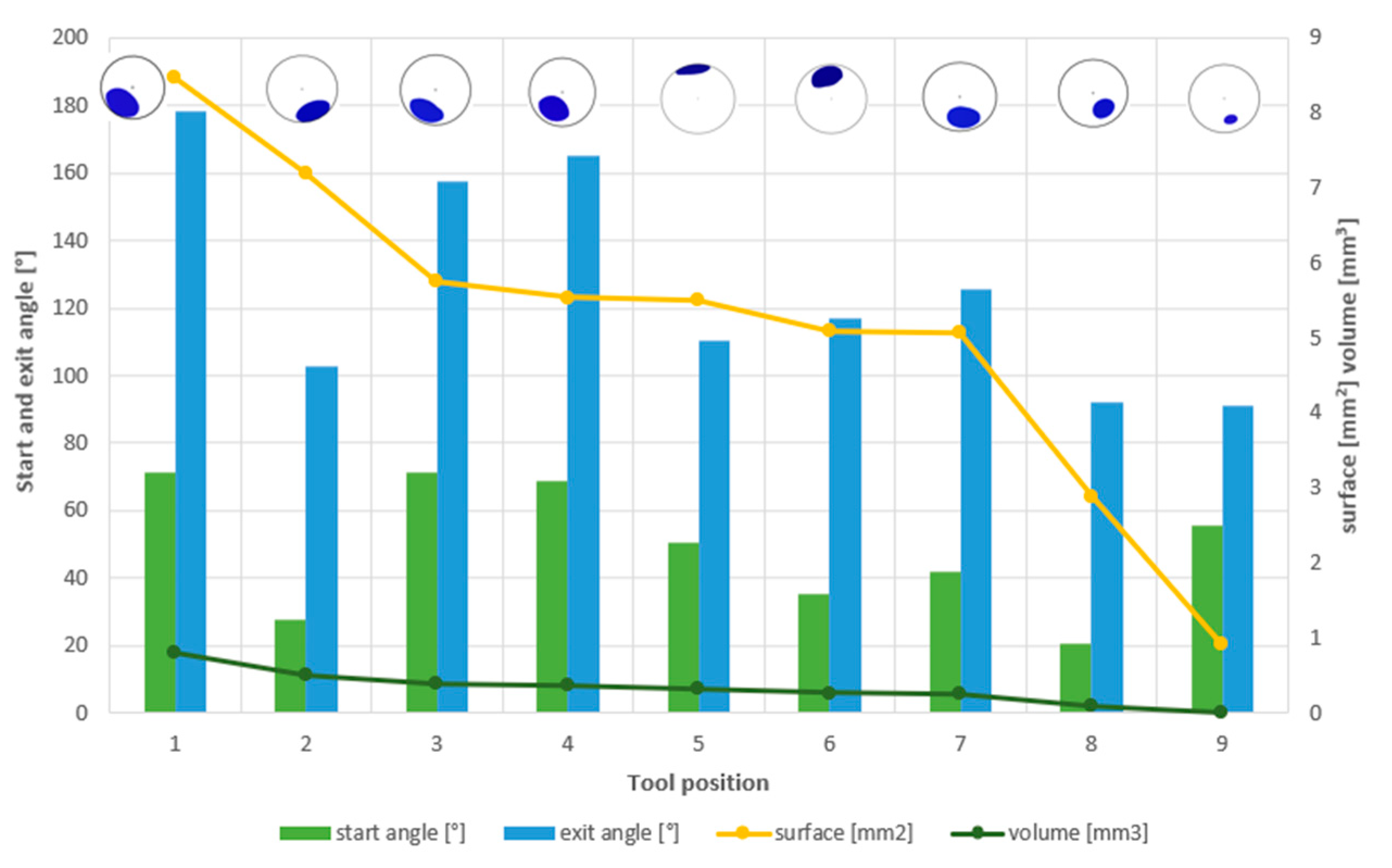

- The start and exit angle defining the tool engagement determines which part of the cutting tool actually participates in the cutting process. With respect to the curvature of the shaped surface, the smallest engagement of the tool corresponded to the position of tool no. 9 and the largest to the position of tool no. 1.

- The obtained engagement sizes also corresponded to the extracted data describing the size of the surface and volume for individual positions of the tool with respect to the curvature of the surface. For tool position no. 9, an area with a value of 0.921 mm2 was measured, which represented the smallest value among all positions, and for position No. 1, an area with a value of 8.467 mm2 was measured in comparison with the other positions. As for the volume, for position no. 9, a capture volume of 0.009 mm3 was achieved, which represented the smallest value among all positions, and for tool position No. 1, a volume of 0.806 mm3 was obtained in comparison with the other positions.

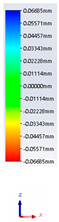

- In the process of analysing the deviations of the surface, the results showed that it was mainly the places defining the undercut in the machining process, which are characterized by negative deviations compared to the initial 3D model. The maximum negative deviation was reached at position no. 2 (value -0.146 mm) and the smallest negative at position No. 3 (value -0.002 mm). The highest positive deviation was measured at position no. 5 (value 0.114 mm) and the smallest positive at position no. 6. (value 0.028 mm). The negative deviations obtained by the scanning method were achieved due to machining near the center of the tool, which was affected by the changing effective diameter of the tool for a given position due to the curvature of the surface. As a result, this has been shown to adversely affect production accuracy. The highest negative deviations for: position no. 4 (-0.139 mm), position no. 8 (-0.102 mm), position no. 9 (-0.127 mm) corresponded to the maximum and minimum values of the Deff parameter compared to positive deviations for tool position No. 5 (0.114 mm) and for position No. 6 (0.028 mm).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| CNC | computer numerical control |

| NC | numerical control |

| CAM | computer-aided manufacturing |

| CL | cutter location |

| CAD | computer-aided design |

| HB | hardness Brinell |

| D | diameter of milling tool |

| RPM | revolutions per minute |

| ae | radial depth of cut |

| ap | depths of cut for given strategies |

| fz | feed per tooth |

| Deff max | maximum effective radius |

| Deff min | minimum effective radius |

| F | feed |

| T | tolerance |

| P | surface allowance |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| S10z | Ten-point height of surface |

| Sa | Arithmetical mean height |

| Ssk | Skewness |

| Lc | cutoff |

| vc | cutting speed |

References

- Jiang, X.J.; Scott, P.J. Fundaments for free-form surfaces. Advanced metrology. 2020, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandiffio, I.; Diniz, A.E.; Souza, A.F. Evaluating surface roughness, tool life, and machining force when milling free-form shapes on hardened AISI D6 steel. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2015, 82, 2075–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hu, G.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, N.; Wang, F. Effect of geometric feature and cutting direction on variation of force and vibration in high-speed milling of TC4 curved surface. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2018, 95, 2207–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.C.; Vickers, G.W.; Dong, Z. A New Principle of CNC Tool Path Planning for Three-Axis Sculptured Part Machining—A Steepest-Ascending Tool Path. Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering. 2004, 126, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KURT, M.; BAGCI, E. Feedrate optimisation/scheduling on sculptured surface machining: a comprehensive review, applications and future direction. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2011, 55, 1037–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurylo, P.; Frankovský, P.; Malinowski, M.; Maciejewski, T.; Varga, J.; Kostka, J.; Adrian, L.; Szufa, S.; Rusnáková, S. Data Exchange with Support for the Neutral Processing of Formats in Computer-Aided Design/Computer-Aided Manufacturing Systems. Applied Sciences. 2023, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Ballu, A. Review and comparison of form error simulation methods for computer-aided tolerancing. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2019, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BEY, M.; CHERFI, A. Finishing of freeform surfaces with an optimized Z-Constant machining strategy. 8th CIRP Conference on High Performance Cutting (HPC 2018). Procedia CIRP 77. 2018, 12, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GENG, L.; LIU, P.L.; LIU, K. Optimization of cutter posture based on cutting force prediction for five-axis machining with ball-end cutters. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2015, 78, 1289–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SOUZA, A.F.; BERKENBROCK, E.; DINIZ, A.E.; RODRIGUES, A.R. Influences of the tool path strategy on the machining force when milling free form geometries with a ball-end cutting tool. J Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2015, 37, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SOUZA, A.F.; DINIZ, A.E.; RODRIGUES, A.R.; COELHO, R.T. Investigating the cutting phenomena in freeform milling using a ball-end cutting tool for die and mold manufacturing. International Journal Advanced Manufacturing Technologies. 2014, 71, 1565–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VARGA, J.; TÓTH, T.; KAŠČÁK, Ľ.; SPIŠÁK, E. The effect of the machining strategy on the surface accuracy when milling with a ball end cutting tool of the aluminum alloy AlCu4Mg. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VARGA, J.; SPIŠÁK, E.; GAJDOŠ, I.; MULIDRÁN, P. Comparison of milling strategies in the production of shaped surfaces. Advances in Science and Technology Research Journal 2022, 16, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VARGA, J.; IŽOL, P.; VRABEĽ, M.; KAŠČÁK, Ľ.; DRBÚL, M.; BRINDZA, J. Surface Quality Evaluation in the Milling Process Using a Ball Nose End Mill. Applied Sciences. 2023, 13, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KAYMAKCI, M.; LAZOGLU, I. Tool path selection strategies for complex sculptured surface machining. Machining Science and Technology. 2008, 12 (), 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DICIUC, V.; LOBONTIU, M.; NASUI, V. The modeling of the ball nose end milling process by using cad methods. Academic Journal of Manufacturing Engineering. 2011, (4), 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- BAGCI, E.; YÜNCÜOĞLU, E.U. The Effects of Milling Strategies on Forces, Material Removal Rate, Tool Deflection, and Surface Errors for the Rough Machining of Complex Surfaces. Journal of Mechanical Engineering. 2017, 63, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WOJCIECHOWSKI, S.; WIACKIEWICZ, G.M.; KROLCZYK, G.M. Study on metrological relations between instant tool displacements and surface roughness during precise ball end milling. Measurement 2018, 129, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TUYSUZ, O.; ALTINTAS, Y.; FENG, H.Y. Prediction of cutting forces in three and five-axis ball-end milling with tool indentation effect. International Journal of Machine Tools & Manufacture. 2013, 66, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BAS, G.; DEMIRCIOGLU, P.; DURAKBASA, N.; OSANNA, P.H. A nanometrological management approach to assess the profile and the surface characteristics of the end milling tools by multi-measurement analysis. Proceedings of the XX IMEKO World Congress. Metrology for Green Growth, Busan, Korea. 2012, p. 1−5.

- MIZUGAKI, Y.; HAO, M.; KIKKAWA, K. Geometric Generating Mechanism of Machined Surface by Ball-nosed End Milling. In: CIRP Annals–Manufacturing Technology. Vol. 50, (2001), p. 69-72.

- CAPLA, R.; SOUZA, A.F.; BRANDÃO, L.C.; COELHO, R.T. Some effects of stock variations due to the use of 2 axes strategy on roughing. In: Proceedings of the 18th International Congress of Mechanical Engineering, Ouro Preto, Brazil, 2005.

- OUYANG, D.; VAN NEST, B. A.; FENG, H. Y. Automatic Ball-End Milling Tool Selection from 3D Point Cloud Data. Flexible Automation and Intelligent Manufacturing, FAIM2004, 2004, pp. 253–260, Toronto, Canada.

- CHOI, B.K.; JUN, C.S. Ball-end cutter interference avoidance in NC machining of sculptured surfaces. Computer Aided Design 1989, 21, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PARK, S.C. Tool path generation for Z-constant contour machining. Computer-Aided Design. 2003, 35, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LACALLE, L.N.L.; LAMIKIZ, A.; POLVOROSA, R.; VALDIVIELSO, A.F.; CALLEJA, A.; GONZALES, H.; ARTEXTE, E. Optimised methodology for aircraft engine IBRs five-axis machining process. International Journal of Mechatronics and Manufacturing Systems. 2016, 9, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SADÍLEK, M.; PORUBA, Z.; ČEPOVÁ, L.; ŠAJGALÍK, M. Increasing the Accuracy of Free-Form Surface Multiaxis Milling. Materials. 2021, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GREŠOVÁ, Z.; IŽOL, P.; VRABEĽ, M.; KAŠČÁK, Ľ.; BRINDZA, J.; DEMKO, M. Influence of Ball-End Milling Strategy on the Accuracy and Roughness of Free Form Surfaces. Applied Sciences. 2022, 12, 4421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TRAN, V.H.; Truong, T.T.; BUI, K.K.; Le, H.K. Quality Assessment of Freeform Surface Manufactured by CNC Milling Using Point Cloud Data Obtained from Different Scanning Devices. Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Mechanical Engineering, Automation, and Sustainable Development 2021. 2022, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MASOOD, A.; SIDDIQUI, R.; PINTO, M.; REHMAN, H.; KHAN, M.A. Tool path generation, for complex surface machining, using point cloud data. Procedia CIRP. 2015, 26, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LI, YADONG.; GU, PEIHUA, G. Inspection of free-form shaped parts. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing. 2005, 21, 421–430. [CrossRef]

- DENG, G.; WANG. G.; DUAN, J. A new algorithm for evaluating form error: the valid characteristic point method with the rapidly contracted constraint zone. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2003, 139, 247–252. [CrossRef]

- YUWEN, S.; XIAOMING, W.; DONGMING, G.; JIAN, L. Machining localization and quality evaluation of parts with sculptured surfaces using SQP method. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2009, 42, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZHANG, Y.; ZHOU, Z.; TANG, K. Sweep scan path planning for five-axis inspection of free-form surfaces. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing. 2018, 49, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHEN, X.X.; ZHAO, J.; ZHANG, W.W. Optimization analysis considering the cutting effects for high-speed five-axis down milling process by employing ball end mill. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 105, 4989–5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOZ, Y.; KHAVIDAKI, S.E.L.; ERDIM, H.; LAZOGLU, I. High Performance 5-Axis Milling of Complex Sculptured Surfaces. Machining of Complex Sculptured Surfaces. 2012, 67–125. [Google Scholar]

- SZPUNAR, M.; OSTROWSKI, R.; TRZEPIECINSKI, T.; KAŠČÁK, Ľ. Central Composite Design Optimisation in Single Point Incremental Forming of Truncated Cones from Commercially Pure Titanium Grade 2 Sheet Metals. Materials. 2021, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DÚRAVČIK, M.; KENDER, Š. Application of reverse engineering techniques in mechanics system services. Procedia Engineering. 2012, 48, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KENDER, Š.; BREZINOVÁ, J. Reverse engineering in automotive design component. International Scientific Journal. 2022, 7, 62–65. [Google Scholar]

| Tool Diameter [mm] | Cutting speed [m.min- 1] | Feed per tooth [mm] | Tooth number |

Tool code |

| End Mill D 18 | 237 | 0.25 | 4200 | AMS2018S |

| Ball End Mill D6 | 94 | 0.015 | 4900 | 273618.060 |

| Ball End Mill D4 | 63 | 0.008 | 4900 | 510418.120 |

| Position | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Position 1 |

Position 2 |

Position 3 |

Position 4 |

Position 5 |

Position 6 |

Position 7 |

Position 8 |

Position 9 |

|

| Deff max [mm] | 1.252 | 1.605 | 1.442 | 1.081 | 1.843 | 1.474 | 1.235 | 0.992 | 1.189 |

| Deff min [mm] | 0.398 | 1.049 | 0.802 | 0.410 | 1.425 | 0.796 | 0.471 | 0.174 | 0.393 |

| Position 1 |

Position 2 |

Position 3 |

Position 4 |

Position 5 |

Position 6 |

Position 7 |

Position 8 |

Position 9 |

|

| Surface [mm2] | 8.467 | 7.197 | 5.751 | 5.541 | 5.513 | 5.096 | 5.080 | 2.894 | 0.921 |

| Volume [mm3] | 0.806 | 0.513 | 0.397 | 0.373 | 0.329 | 0.269 | 0.256 | 0.092 | 0.009 |

| Position 1 |

Position 2 |

Position 3 |

Position 4 |

Position 5 |

Position 6 |

Position 7 |

Position 8 |

Position 9 |

|

| Start angle | 71.29 | 27.95 | 71.25 | 69.05 | 50.81 | 35.12 | 41.74 | 20.77 | 55.81 |

| Exit angle | 178.26 | 102.69 | 157.58 | 165.44 | 110.66 | 116.94 | 125.54 | 91.95 | 90.99 |

| Position 1 | Position 2 | Position 3 | Position 4 | Position 5 | Position 6 | Position 7 | Position 8 | Position 9 |

| -0.036 | -0.146 | -0.002 | -0.139 | 0.114 | 0.028 | -0.075 | -0.102 | -0.127 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).