Submitted:

13 November 2023

Posted:

14 November 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

2.2. Data extraction

2.3. Data Selection & Inclusion Criteria

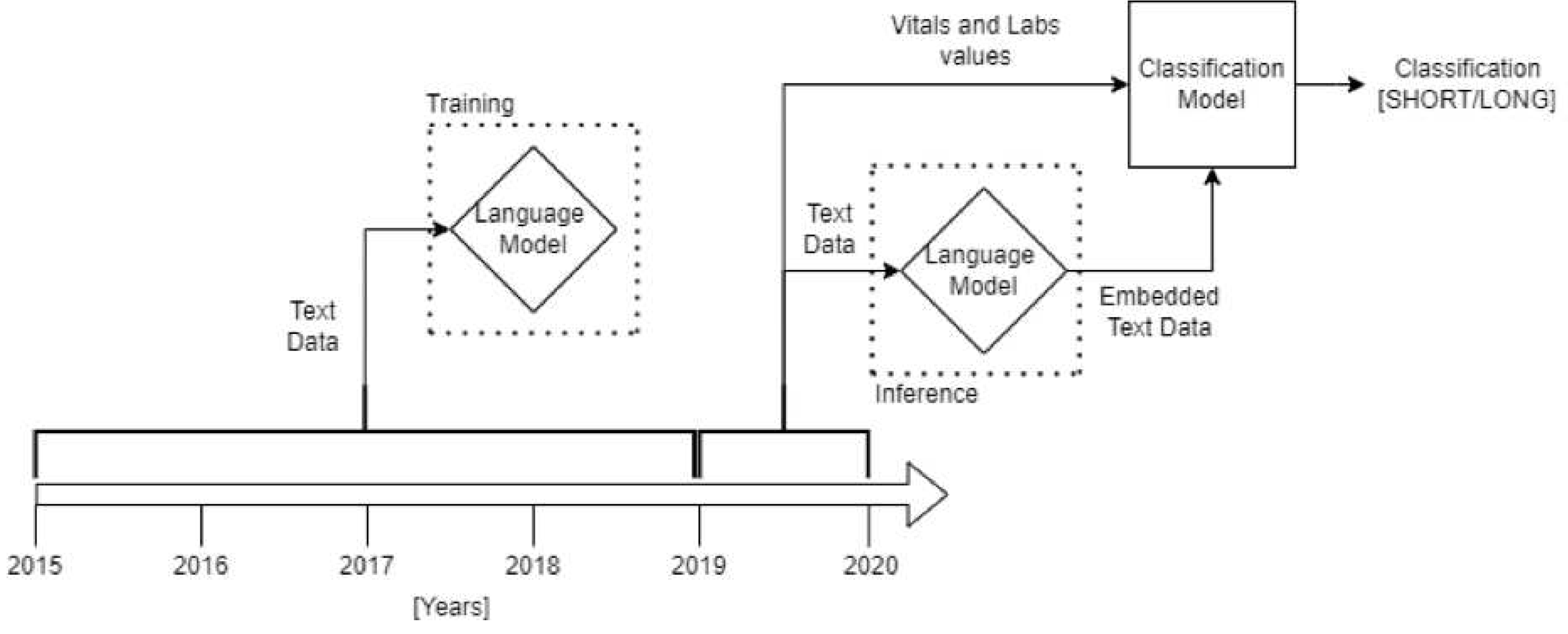

2.4. Methods

- Pandas 1.0.1 [20]: importing and managing data.

- Numpy 1.18.1 [21]: array manipulation and scientific computation.

- Scikit-learn 1.0.0 [22]: definition, training and validation of machine learning and statistical models.

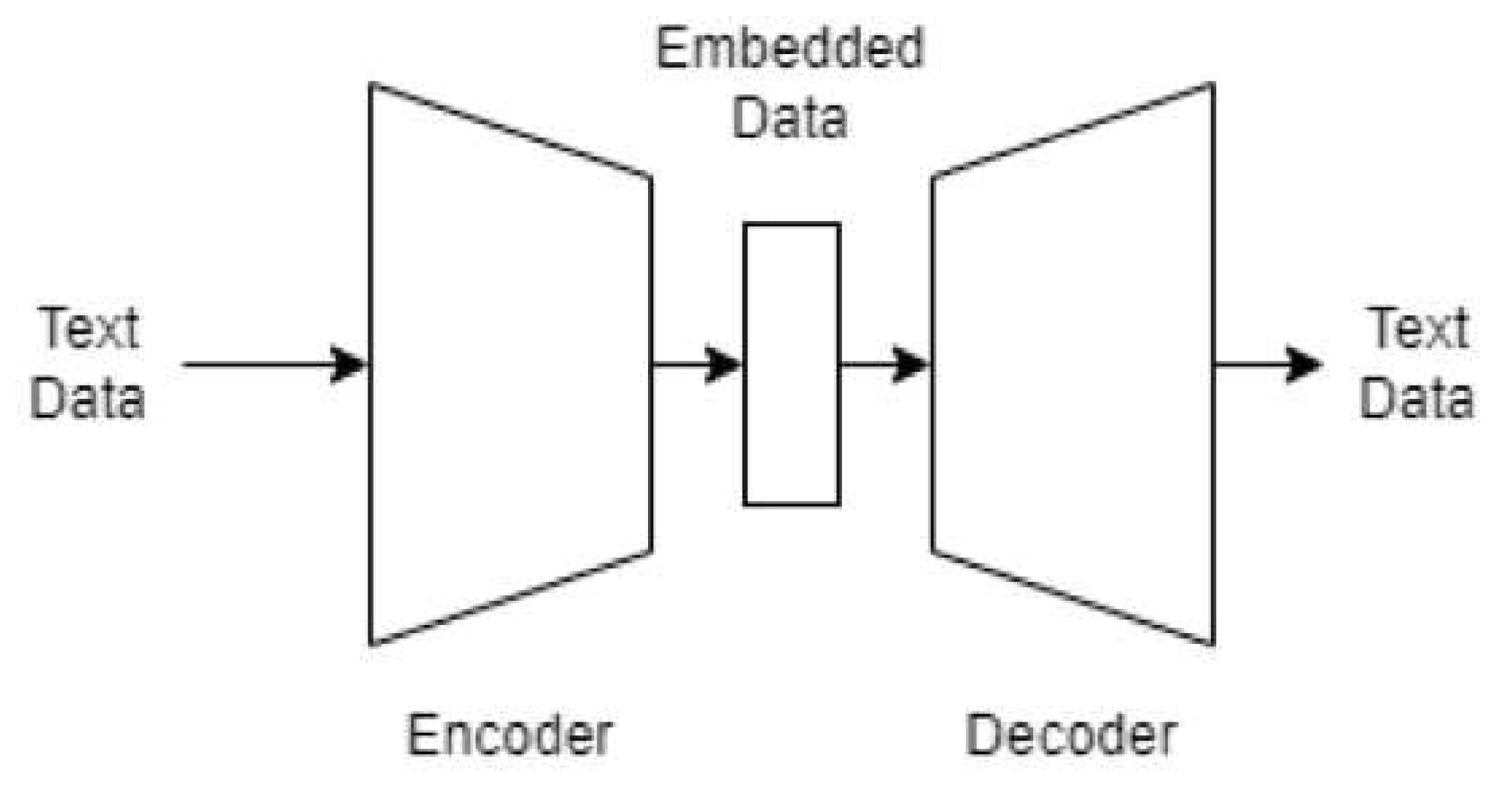

- Tensorflow 2.0.0 [23]: definition, training and validation of transformer autoencoder.

- Matplotlib 3.1.3 [24]: plotting models performances.

2.5. Text preprocessing

2.6. Classification

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Dataset and Univariate Analysis

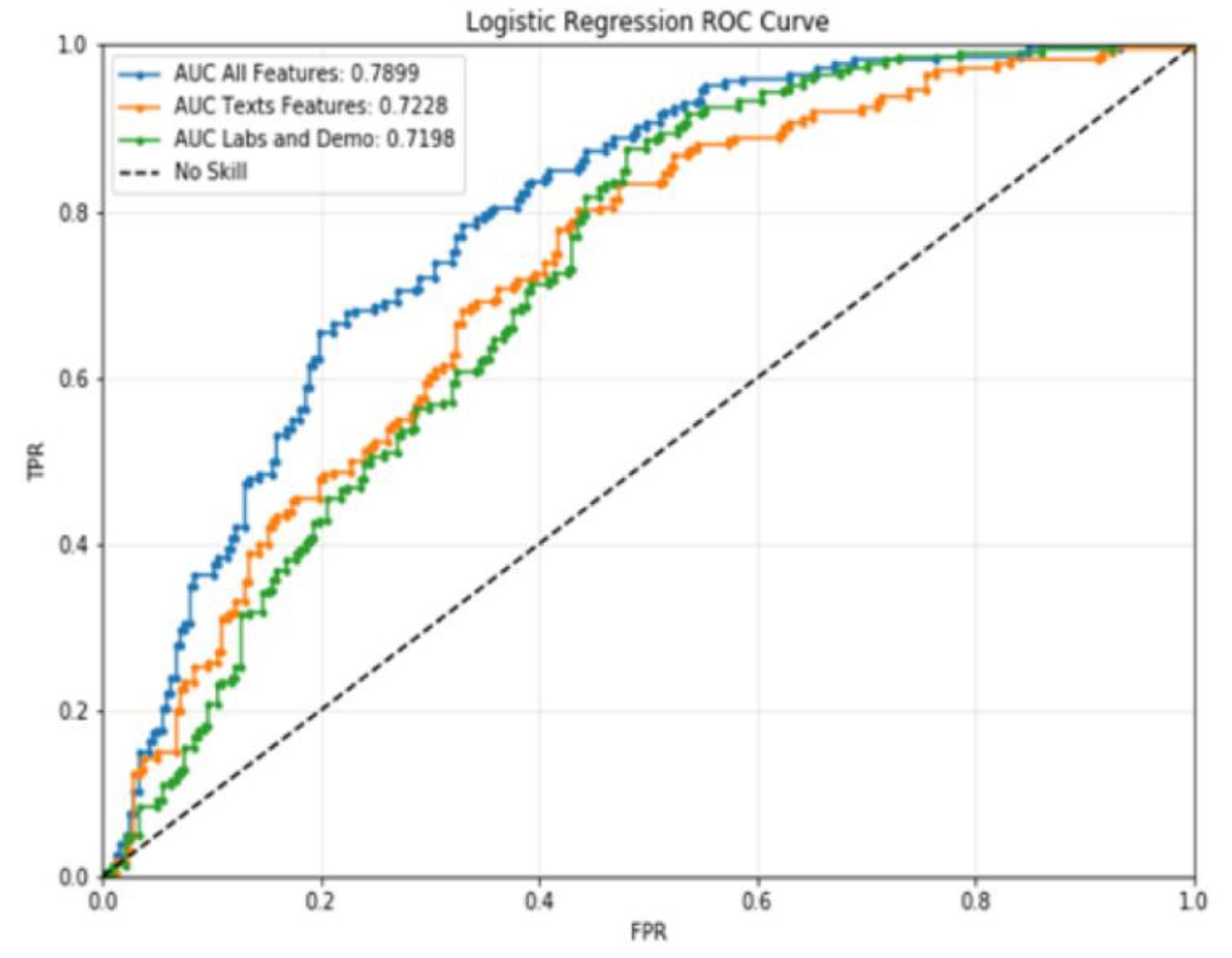

3.2. Classification

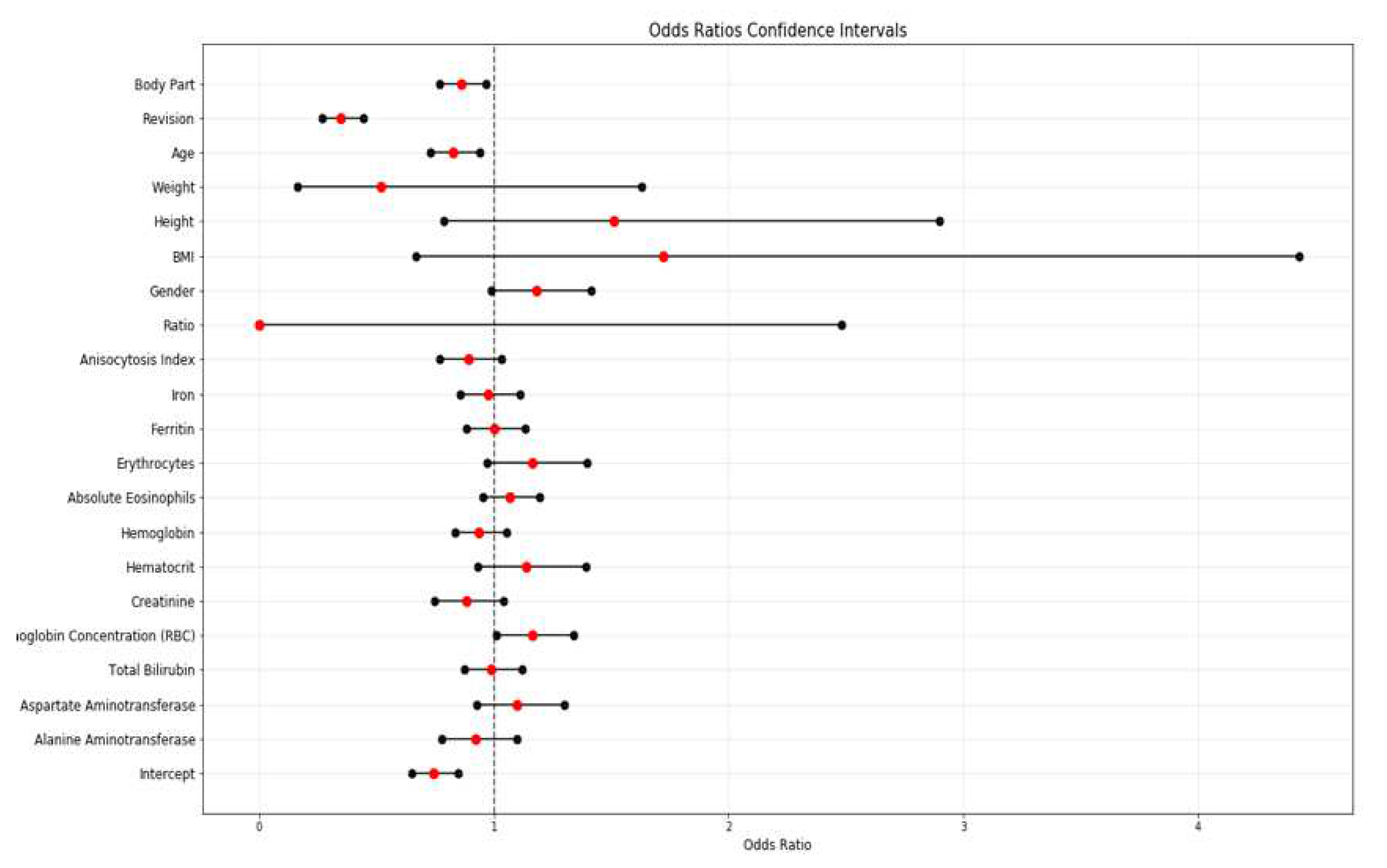

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Konopka, J.F.; Lee, Y.-Y.; Su, E.P.; McLawhorn, A.S. Quality-Adjusted Life Years After Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: Health-Related Quality of Life After 12,782 Joint Replacements. JB JS Open Access 2018, 3, e0007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedetta Report Annuale RIAP 2021 e Compendio Available online:. Available online: https://riap.iss.it/riap/it/attivita/report/2022/10/27/report-annuale-riap-2021/ (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Torre, M.; Romanini, E.; Zanoli, G.; Carrani, E.; Luzi, I.; Leone, L.; Bellino, S. Monitoring Outcome of Joint Arthroplasty in Italy: Implementation of the National Registry. Joints 2017, 5, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husted, H.; Solgaard, S.; Hansen, T.B.; Søballe, K.; Kehlet, H. Care Principles at Four Fast-Track Arthroplasty Departments in Denmark.

- Kehlet, H. Fast-Track Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. Lancet 2013, 381, 1600–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frassanito, L.; Vergari, A.; Nestorini, R.; Cerulli, G.; Placella, G.; Pace, V.; Rossi, M. Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) in Hip and Knee Replacement Surgery: Description of a Multidisciplinary Program to Improve Management of the Patients Undergoing Major Orthopedic Surgery. Musculoskelet Surg 2020, 104, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayfield, C.K.; Haglin, J.M.; Levine, B.; Valle, C.D.; Lieberman, J.R.; Heckmann, N. Medicare Reimbursement for Hip and Knee Arthroplasty From 2000 to 2019: An Unsustainable Trend. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2020, 35, 1174–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulshan, V.; Peng, L.; Coram, M.; Stumpe, M.C.; Wu, D.; Narayanaswamy, A.; Venugopalan, S.; Widner, K.; Madams, T.; Cuadros, J.; et al. Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Algorithm for Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy in Retinal Fundus Photographs. JAMA 2016, 316, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embi, P.J.; Kaufman, S.E.; Payne, P.R.O. Biomedical Informatics and Outcomes Research: Enabling Knowledge-Driven Health Care. Circulation 2009, 120, 2393–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafri, G.; Li, L.; Paxton, E.W.; Fan, J. Predicting Risk for Adverse Health Events Using Random Forest. Journal of Applied Statistics 2018, 45, 2279–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, D.; Wong, C.; Deligianni, F.; Berthelot, M.; Andreu-Perez, J.; Lo, B.; Yang, G.-Z. Deep Learning for Health Informatics. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2017, 21, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, S.M.; Wang, E.Y.; Haeberle, H.S.; Mont, M.A.; Krebs, V.E.; Patterson, B.M.; Ramkumar, P.N. Machine Learning and Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty: Patient Forecasting for a Patient-Specific Payment Model. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2018, 33, 3617–3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biron, D.R.; Sinha, I.; Kleiner, J.E.; Aluthge, D.P.; Goodman, A.D.; Sarkar, I.N.; Cohen, E.; Daniels, A.H. A Novel Machine Learning Model Developed to Assist in Patient Selection for Outpatient Total Shoulder Arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2020, 28, e580–e585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etzel, C.M.; Veeramani, A.; Zhang, A.S.; McDonald, C.L.; DiSilvestro, K.J.; Cohen, E.M.; Daniels, A.H. Supervised Machine Learning for Predicting Length of Stay After Lumbar Arthrodesis: A Comprehensive Artificial Intelligence Approach. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2022, 30, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anis, H.K.; Strnad, G.J.; Klika, A.K.; Zajichek, A.; Spindler, K.P.; Barsoum, W.K.; Higuera, C.A.; Piuzzi, N.S.; Group, C.C.O.A. Developing a Personalized Outcome Prediction Tool for Knee Arthroplasty. The Bone & Joint Journal 2020, 102-B, 1183–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, P.N.; Karnuta, J.M.; Navarro, S.M.; Haeberle, H.S.; Scuderi, G.R.; Mont, M.A.; Krebs, V.E.; Patterson, B.M. Deep Learning Preoperatively Predicts Value Metrics for Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty: Development and Validation of an Artificial Neural Network Model. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2019, 34, 2220–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramkumar, P.N. Development and Validation of a Machine Learning Algorithm After Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty: Applications to Length of Stay and Payment Models. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, R.A.; Sharma, B.S.; Doan, C.N.; Jiang, X.; Schmidt, U.H.; Vaida, F. A Predictive Model for Determining Patients Not Requiring Prolonged Hospital Length of Stay After Elective Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2019, 129, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenstein, A.S.; Teitel, J.; Mitten, D.J.; Ricciardi, B.F.; Myers, T.G. An Electronic Medical Record–Based Discharge Disposition Tool Gets Bundle Busted: Decaying Relevance of Clinical Data Accuracy in Machine Learning. Arthroplasty Today 2020, 6, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinney, W. Pandas: A Foundational Python Library for Data Analysis and Statistics.

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array Programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. MACHINE LEARNING IN PYTHON.

- Abadi, M.; Barham, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; Ghemawat, S.; Irving, G.; Isard, M.; et al. TensorFlow: A System for Large-Scale Machine Learning.

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Computing in Science and Engineering 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabold, S.; Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and Statistical Modeling with Python.; Austin, Texas, 2010; pp. 92–96.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need.

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization 2017.

- Buuren, S. van; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. Mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, Roger. Practical Methods of Optimization. John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

- Podmore, B.; Hutchings, A.; Skinner, J.A.; MacGregor, A.J.; van der Meulen, J. Impact of Comorbidities on the Safety and Effectiveness of Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Surgery. Bone Joint J. [CrossRef]

- Masaracchio, M.; Hanney, W.J.; Liu, X.; Kolber, M.; Kirker, K. Timing of Rehabilitation on Length of Stay and Cost in Patients with Hip or Knee Joint Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0178295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padegimas, E.M.; Verma, K.; Zmistowski, B.; Rothman, R.H.; Purtill, J.J.; Howley, M. Medicare Reimbursement for Total Joint Arthroplasty: The Driving Forces. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 2016, 98, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Long (Group 2) | Short (Group 1) | Measure | P-Value | ||||

| Patients | 795 | 722 | # | 0.3196 | |||

| Admissions | 812 (52.7%) | 729 (47.3%) | # | 0.0000 | |||

| Mean Age | 67.0 | 63.8 | Years | 0.0000 | |||

| Mean BMI | 27.439 | 27.709 | % | 0.2497 | |||

| Mean Height | 165.688 | 167.716 | cm | 0.0001 | |||

| Mean Weight | 75.605 | 78.181 | Kg | 0.0030 | |||

| Mean LOS | 11.7 | 5.7 | Days | 0.0000 | |||

| Mean Absolute eosinophils | 0.169 | 0.182 | mg/dL | 0.0449 | |||

| Mean Alanine aminotransferase | 19.232 | 21.213 | mg/dL | 0.0000 | |||

| Mean Anisocytosis Index | 14.292 | 13.960 | mg/dL | 0.0000 | |||

| Mean Aspartate aminotransferase | 21.380 | 22.344 | mg/dL | 0.0130 | |||

| Mean Creatinine | 0.818 | 0.804 | mg/dL | 0.0003 | |||

| Mean Erythrocytes | 4.639 | 4.762 | mg/dL | 0.0000 | |||

| Mean Ferritin | 96.240 | 108.057 | mg/dL | 0.0002 | |||

| Mean Hematocrit | 41.807 | 43.171 | mg/dL | 0.0000 | |||

| Mean Hemoglobin | 7.519 | 7.719 | mg/dL | 0.0000 | |||

| Mean INR | 1.066 | 1.023 | mg/dL | 0.0000 | |||

| Mean Iron | 80.938 | 86.495 | mg/dL | 0.0001 | |||

| Mean RBC hemoglobin concentration | 33.108 | 33.320 | mg/dL | 0.0000 | |||

| Mean Ratio | 1.067 | 1.023 | mg/dL | 0.0000 | |||

| Mean Total Bilirubin | 0.709 | 0,747 | mg/dL | 0.0057 | |||

| Hip | 639 (78.7%) | 530 (72,7%) | # | 0.0000 | |||

| Knee | 173 (21.3%) | 199 (27,3%) | # | 0.0566 | |||

| Female | 503 (61.9%) | 364 (49,9%) | # | 0.0000 | |||

| Male | 309 (38.1%) | 365 (50,1%) | # | 0.0023 | |||

| One | 6 | 4 | # | 0.3711 | |||

| Two | 60 | 59 | # | 0.8969 | |||

| Three | 2 | 1 | # | 0.4142 | |||

| Four | 2 | 1 | # | 0.4142 | |||

| Five | 11 | 3 | # | 0.0025 | |||

| Six | 560 | 481 | # | 0.0005 | |||

| Unknown | 171 | 180 | # | 0.4969 | |||

| No | 248 (25.4%) | 728 (74,6%) | # | 0.0000 | |||

| Yes | 564 (99.8%) | 1 (0,2%) | # | 0.0000 | |||

| No | 641 (47.0%) | 722 (53,0%) | # | 0.0019 | |||

| Yes | 171 (96.1%) | 7 (3,9%) | # | 0.0000 | |||

| LONG | SHORT | |||||||

| F1 Score | Precision | Recall | Support | F1 Score | Precision | Recall | Support | |

| Complete | 0.709251 | 0.741935 | 0.679325 | 237.0 | 0.720339 | 0.691057 | 0.752212 | 226.0 |

| Texts | 0.656319 | 0.691589 | 0.624473 | 237.0 | 0.673684 | 0.642570 | 0.707965 | 226.0 |

| Others | 0.642082 | 0.660714 | 0.624473 | 237.0 | 0.645161 | 0.627615 | 0.663717 | 226.0 |

| MACRO AVG | WEIGHTED AVG | |||||||

| F1 Score | Precision | Recall | Support | F1 Score | Precision | Recall | Support | |

| Complete | 0.714795 | 0.716496 | 0.715769 | 463.0 | 0.714663 | 0.717101 | 0.714903 | 463.0 |

| Texts | 0.665002 | 0.66708 | 0.666219 | 463.0 | 0.664795 | 0.667662 | 0.665227 | 463.0 |

| Others | 0.643622 | 0.644165 | 0.644095 | 463.0 | 0.643585 | 0.644558 | 0.643629 | 463.0 |

| Feature | Coefficients | Standard Errors | W values | P > |z| | Odds Ratio | [0.025 | 0.975] | ||

| 0 | Intercept | -0.2990 | 0.0680 | -4.3950 | 0.0000 | 0.7416 | 0.6490 | 0.8473 | |

| 1 | Alanine aminotransferase | -0.0785 | 0.0870 | -0.9060 | 0.3650 | 0.9245 | 0.7796 | 1.0964 | |

| 2 | Aspartate aminotransferase | 0.0931 | 0.0860 | 1.0860 | 0.2780 | 1.0976 | 0.9273 | 1.2991 | |

| 3 | Total Bilirubin | -0.0111 | 0.0630 | -0.1760 | 0.8600 | 0.9890 | 0.8741 | 1.1189 | |

| 4 | Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) | 0.1503 | 0.0720 | 2.0910 | 0.0370 | 1.1622 | 1.0092 | 1.3383 | |

| 5 | RBC hemoglobin concentration | -0.1261 | 0.0850 | -1.4880 | 0.1370 | 0.8815 | 0.7462 | 1.0413 | |

| 6 | Hematocrit | 0.1303 | 0.1020 | 1.2820 | 0.2000 | 1.1392 | 0.9327 | 1.3913 | |

| 7 | Hemoglobin | -0.0647 | 0.0600 | -1.0800 | 0.2800 | 0.9373 | 0.8334 | 1.0543 | |

| 8 | Absolute eosinophils | 0.0658 | 0.0570 | 1.1600 | 0.2460 | 1.0680 | 0.9551 | 1.1943 | |

| 9 | Erythrocytes | 0.1528 | 0.0930 | 1.6510 | 0.0990 | 1.1651 | 0.9710 | 1,3981 | |

| 10 | Ferritin | 0.0012 | 0.0630 | 0.0190 | 0.9850 | 1.0012 | 0.8849 | 1.1328 | |

| 11 | Iron | -0.0239 | 0.0670 | -0.3560 | 0.7220 | 0.9764 | 0.8562 | 1.1134 | |

| 12 | INR | 8.4158 | 4.9490 | 1.7000 | 0.0890 | 4517.8884 | 0.2769 | 73724077.5095 | |

| 13 | Anisocytosis Index | -0.1163 | 0.0760 | -1.5400 | 0.1240 | 0.8902 | 0.7670 | 1.0332 | |

| 14 | Ratio | -8.8155 | 4.9610 | -1.7770 | 0.0760 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 2.4795 | |

| 15 | Gender | 0.1667 | 0.0910 | 1.8380 | 0.0660 | 1.1814 | 0.9884 | 1.4121 | |

| 16 | One | -0.0423 | / | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9586 | 0 | / | |

| 17 | Two | 0.0191 | / | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0193 | 0 | / | |

| 18 | Three | -0.0360 | / | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9646 | 0 | / | |

| 19 | Four | -0.0491 | / | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9521 | 0 | / | |

| 20 | Five | -0.0973 | / | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9073 | 0 | / | |

| 21 | Six | 0.0011 | / | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0011 | 0 | / | |

| 22 | Unknown | 0.0257 | / | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0260 | 0 | / | |

| 23 | BMI | 0.5422 | 0.4830 | 1.1220 | 0.2620 | 1.7198 | 0.6673 | 4.4321 | |

| 24 | Height | 0.4118 | 0.3330 | 1.2380 | 0.2160 | 1.5095 | 0.7859 | 2.8993 | |

| 25 | Weight | -0.6558 | 0.5840 | -1.1220 | 0.2620 | 0.5190 | 0.1652 | 1.6304 | |

| 26 | Age | -0.1895 | 0.0640 | -2.9460 | 0.0030 | 0.8274 | 0.7298 | 0.9379 | |

| 27 | Revision | -1.0611 | 0.1260 | -8.4100 | 0.0000 | 0.3461 | 0.2703 | 0.4430 | |

| 28 | Body Part | -0.1499 | 0.0590 | -2.5560 | 0.0110 | 0.8608 | 0.7668 | 0.9663 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).