1. Introduction

The cell surface concentration of polytopic plasma membrane proteins, such as receptors, transporters or ion channels is controlled by various mechanisms, including constitutive or induced endocytosis [

1] and the delivery of neo-synthesized proteins from the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) to the plasma membrane via the Golgi apparatus. Transport from the ER to the Golgi complex involves the selective capture of membrane proteins to be exported to the cell surface into COPII carrier vesicles located in specific localized areas, known as the ER exit sites (or ERES) [

2].

There is experimental evidence that G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) need to be loaded into COPII vesicles to exit the ER [

3]. GPCRs can be actively captured by COPII via specific motifs and/or direct interaction with COPII components that in turn affects their export dynamics [

4]. Whereas in many cases the vesicle recruitment and export of correctly folded GPCRs seems to occur by default as part of fluid and membrane bulk flow [

2], other receptors require oligomerization [

5] and/or interaction with specific chaperones or escort proteins [

6] to leave the ER. In addition, several GPCRs are retained within intracellular compartments, limiting or preventing their export to the cell surface. In most cases GPCR retention is caused by mutations and associated with accelerated proteasomal degradation, leading to pathological effects [

7]. However, some non-mutated GPCRs are also selectively retained within intracellular compartments, and are released to ERES upon cellular signals [

8], for a fine-tuning of their biological function.

A prototypical example of GPCR physiological intracellular retention is the GB1 subunit of the GABA

B receptor, the metabotropic receptor of the principal inhibitory neuromediator. Functional GABA

B receptors are hetero-dimers constituted of GB1 and GB2 protomers, [

9,

10,

11]. GB1 contains the GABA binding site [

9] but fails to reach the cell surface when expressed in heterologous systems or overexpressed in neurons [

12]. GB1 contains within its carboxy-terminal tail a tandem di-leucine motif and an arginine-based signal (RXR), which cause its ER retention [

13,

14]. GB2 couples to G-proteins [

15,

16] and can reach the cell surface in the absence of GB1, as a functionally inactive homo-dimer [

17]. The shielding of the GB1 retention signal via a coiled-coil interaction with the carboxy-terminal of GB2 allows the hetero-dimer to reach the cell surface [

13]. We reported that the Prenylated Rab Acceptor Family member 2 (PRAF2), a ubiquitous membrane-associated protein [

18] particularly abundant in the ER [

19], was the gatekeeper that retains GB1 in the ER via the recognition of its RXR-di-leucine signal [

20]. PRAF2 tightly controls cell-surface GABA

B density in vitro and in vivo [

20]. PRAF2 was subsequently found to interact on a stoichiometric basis with both wild-type and mutant Cystic Fibrosis (CF) Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR), preventing the access of newly synthesized cargo to ERES. The PRAF2-CFTR interaction involves a specific RXR-di-leucine motif located in the first nucleotide-binding domain of the transporter [

21].

GABA

B receptor is a class-C GPCR, particular for its unique heterodimeric organization. So far, it has not been established whether PRAF2 can regulate the export of other GPCRs. The chemokine receptor CCR5 was a good Class-A GPCR candidate, to be tested for potential regulation by PRAF2 due to several reasons. Indeed, PRAF2 was originally isolated in two-hybrid screen using the C tail of the chemokine receptor CCR5, and its overexpression in reconstituted cell systems was correlated with reduced expression of the receptor [

22]. In addition to its physiological role in chemotaxis, and in the effector functions of T lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells, CCR5 is the main co-receptor for HIV-1 cell entry, in association with CD4 [

23]. Cell surface association of CCR5 and CD4 is a prerequisite for gp120 viral protein binding [24, 25]. In resting primary T lymphocytes part of CCR5 is stored in intracellular compartments [

26] and its interaction with CD4 in the ER facilitates its export to the cell surface, CD4 acting as a “private” escort protein for CCR5 [

27]. The physiological intracellular retention of CCR5 was corroborated by experiments in THP-1 monocytes in vitro, showing that cell adhesion on fibronectin-coated slides for 10 minutes was sufficient to increase surface CCR5 5-fold, independently of CD4 [

28]. Finally, some natural mutants of CCR5 lacking the C-terminal tail are completely retained in the ER, preventing HIV-1 infection in humans [

29]. These data indicate that CCR5 retention in the ER is an important regulated phenomenon and suggest a potential mechanistic role of PRAF2 in this context. However, the lack of the PRAF2 binding motifs identified for GB1 and CFTR in the C-tail of CCR5 indicate different modes of interaction/retention.

2. Results

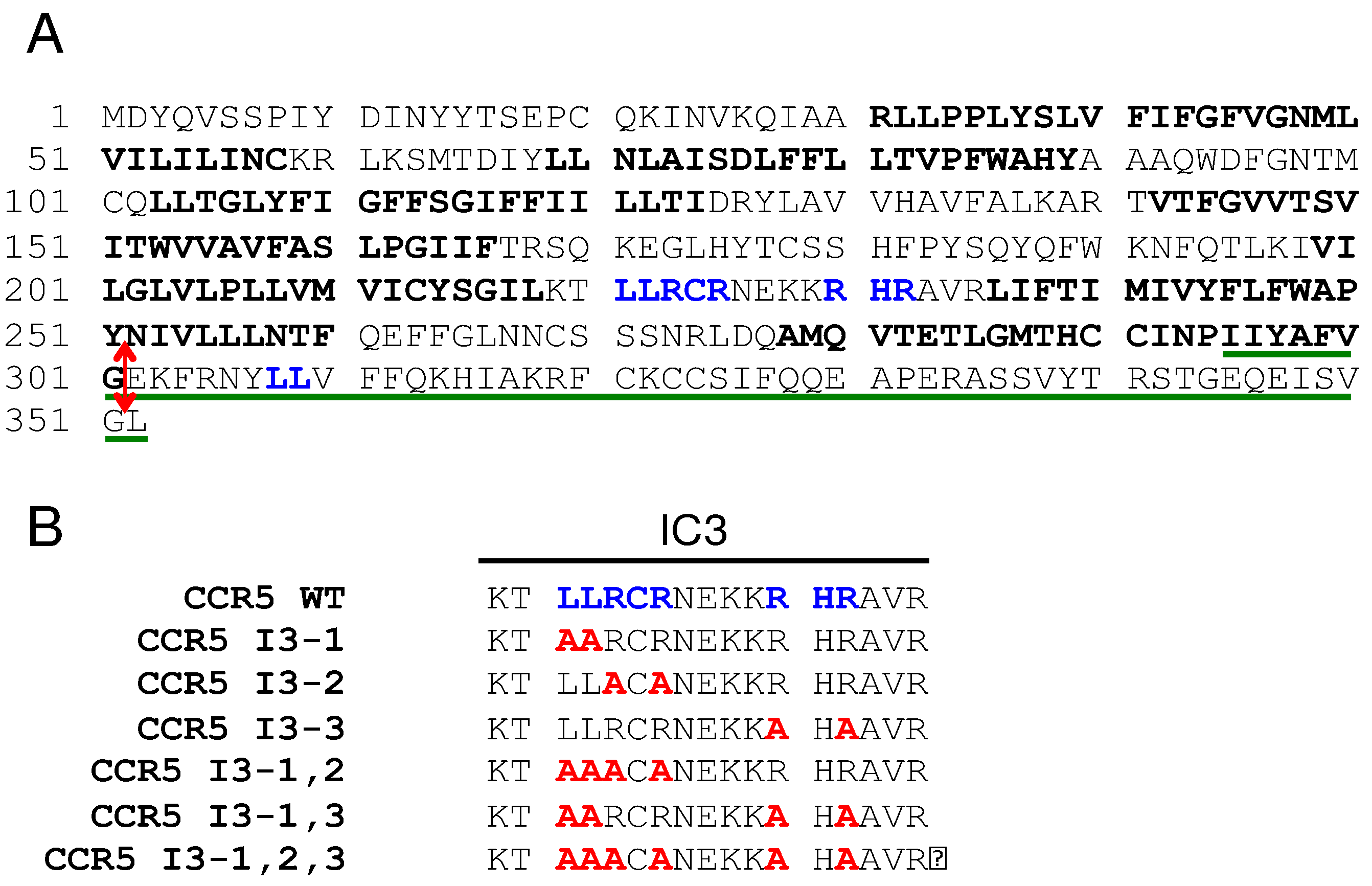

The protein sequence of human CCR5 is shown in

Figure 1A. Di-leucine (LL) motifs and arginine-based motifs (RXR) present in the third cytoplasmic loop and in the C-terminal tail of the receptor are in blue. FS299, a natural CCR5 mutant principally found in Asia consists of a single base pair deletion causing a frame shift near the end of the seventh transmembrane domain (amino acid residue position 299). A premature termination occurs causing the absence of intracellular C-terminal domain. This mutant is poorly expressed at the cell surface and retained within intracellular compartments [29, 30]. We introduced a stop codon after the glycine 301 to produce the CCR5-ΔCter mutant, which is also similarly retained intracellularly as the FS299 natural mutant [

27]. The sequence of the C-terminal CCR5 (295–352) peptide used as bait in the two-thybrid screen, which identified PRAF2 as a CCR5-interacting partner [

22], is underlined in green.

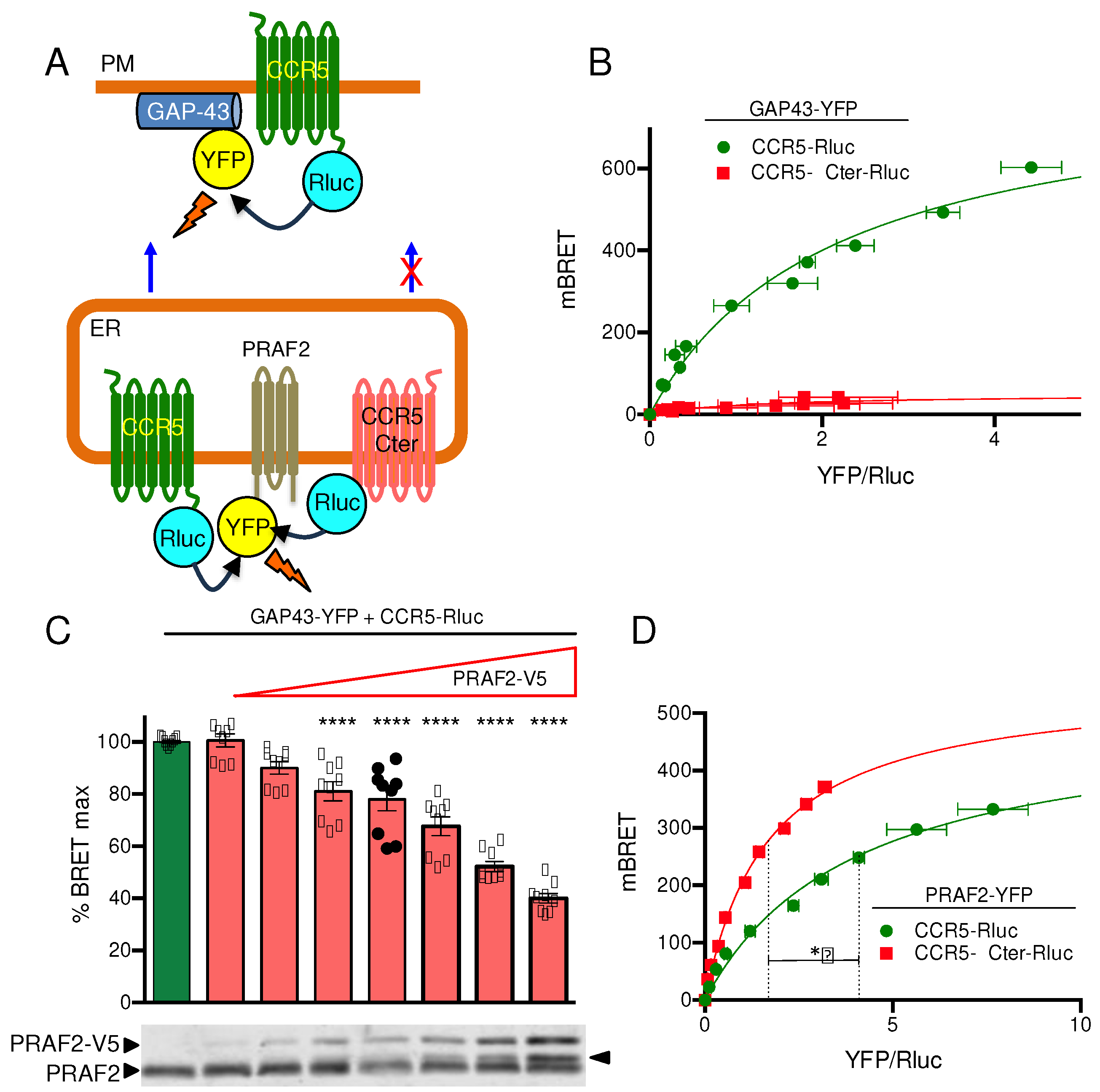

A proximity assay with a Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET)- based biosensor was used to monitor the cell surface targeting of CCR5 (

Figure 2A). GAP-43 (Growth Associated Protein 43) is a neuronal cytoplasmic protein that is attached to the inner face of the plasma membrane via a dual palmitoylation sequence on cysteine residues 3 and 4. The first 20 amino acid residues of GAP43, fused upstream of the yellow fluorescent protein (YFP), were used as energy transfer acceptor, whereas wild type or mutant CCR5 fused upstream of Renilla luciferase were the BRET donors. Upon co-transfection of relevant plasmids in HEK-293 cells, the CCR5 exported to the cell surface in the proximity of GAP-43-YFP can produce a BRET signal. BRET saturation curves were generated by increasing the concentrations of GAP-43-YFP in the presence of constant amounts of CCR5-Rluc (

Figure 2B). A saturable hyperbolic curve was obtained with CCR5-Rluc, indicative of its targeting to the cell surface. In contrast, low levels of bystander (linear) BRET were obtained with CCR5-ΔCter-Rluc, consistent with its reported almost exclusive intracellular retention [

29].

PRAF2 was reported to play a role of gatekeeper [

31], capable of physiologically retaining on a stoichiometric basis wild type GBR1 and CFTR in the ER [20, 21]. The possible control of CCR5 export by PRAF2 was then investigated by measuring the amount of CCR5 reaching the cell surface in the presence of increasing concentrations of PRAF2, with the biosensor used above (

Figure 2C). Supporting this hypothesis, the BRET signal obtained decreased as a function of increasing concentrations of exogenous epitope-tagged PRAF2 (PRAF2-V5). The highest amount of PRAF2-V5, which appeared about 2-fold higher than endogenous PRAF2 in immunoblot (lower panes,

Figure 2C), was associated with about 60% reduction of surface CCR5. To document the potential direct interaction of PRAF2 with CCR5 and CCR5-ΔCter, additional BRET-based proximity experiments were performed using PRAF2-YFP as BRET acceptor (

Figure 2A,D). In this configuration, hyperbolic curves were obtained with both donors (

Figure 2D). Interestingly, significantly lower BRET

50 values were measured for CCR5-ΔCter-Rluc, compared to CCR5-Rluc, indicating a higher propensity of the former to be in proximity of PRAF2-YFP. Thus, a possible higher affinity of PRAF2 for CCR5-ΔCter might contribute to the greater retention of this mutant. The reduced maximal BRET (BRET

max) obtained with CCR5-Rluc, compared to CCR5-ΔCter-Rluc is due to the fact that the pool of CCR5-Rluc having reached the cell surface cannot transfer any energy to the ER-associated PRAF2-YFP.

Since PRAF2 was originally identified as an interacting partner of the C-terminal tail of CCR5 [

22], which is absent in the CCR5-ΔCter mutant, additional domain(s) of interaction with PRAF2 likely exist in the CCR5 sequence. In particular, PRAF2 was reported to interact with tandem LL RXR motifs present in the GB1 C-terminal tail [

20] and in the CFTR nucleotide-binding domain NBD1 [

21]. Similar motifs appear in the third intracellular loop (I3) of CCR5. We therefore investigated whether the LL and RXR motifs of CCR5-I3 might participate in interaction with PRAF2. A series of CCR5 mutants were made, in which these motifs were substituted individually or in association (

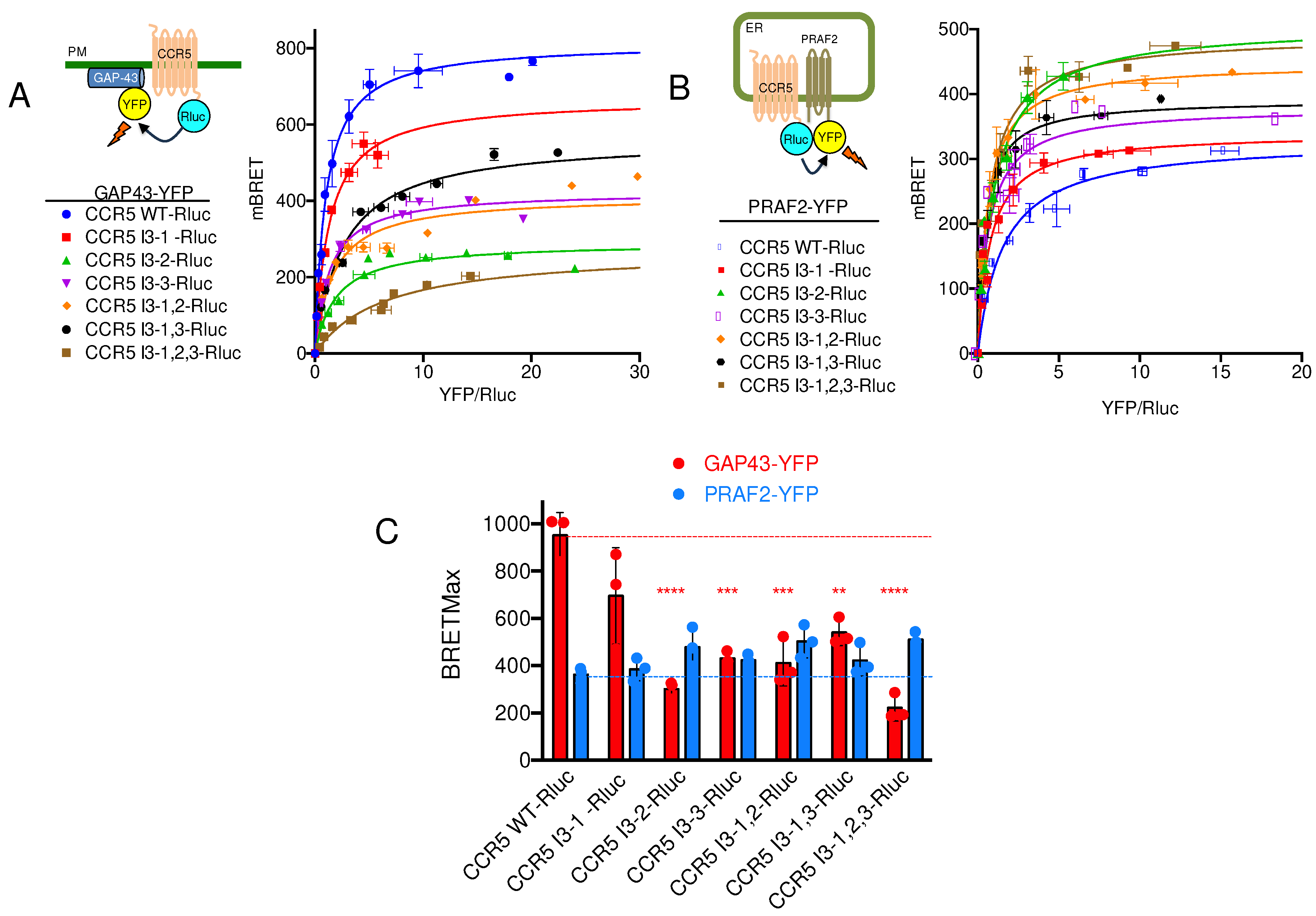

Figure 1B), and tested for their cell surface export (

Figure 3A). The substitution of each of these motifs variably affected the amount of CCR5-Rluc reaching the cell surface, reflected by the maximal BRET signal obtained with GAP-43-YFP as acceptor. Whereas the substitution of the di-leucine motif alone (CCR5 I3-1-Rluc) did not significantly modify the BRET

max value (

Figure 3C), all other mutations inhibited the surface export of CCR5, the substitution of the first RXR motif of the I3 loop (see mutant CCR5 I3-2-Rluc) accounting alone for about 70% of the inhibition. In parallel experiments measuring BRET between CCR5-Rluc or CCR5-Rluc mutants and PRAF2-YFP, neither BRET

max nor BRET

50 values were statistically different between CCR5 and CCR5 mutants (

Figure 3B,C), indicating that the LL and RXR motifs in the I3 of CCR5 are not critical for the receptor interaction with PRAF2. BRET

max value (

Figure 3C), all other mutations inhibited the surface export of CCR5, the substitution of the first RXR motif of the I3 loop (see mutant CCR5 I3-2-Rluc) accounting alone for about 70% of the inhibition. In parallel experiments measuring BRET between CCR5-Rluc or CCR5-Rluc mutants and PRAF2-YFP, neither BRET

max nor BRET

50 values were statistically different between CCR5 and CCR5 mutants (

Figure 3B,C), indicating that the LL and RXR motifs in the I3 of CCR5 are not critical for the receptor interaction with PRAF2.

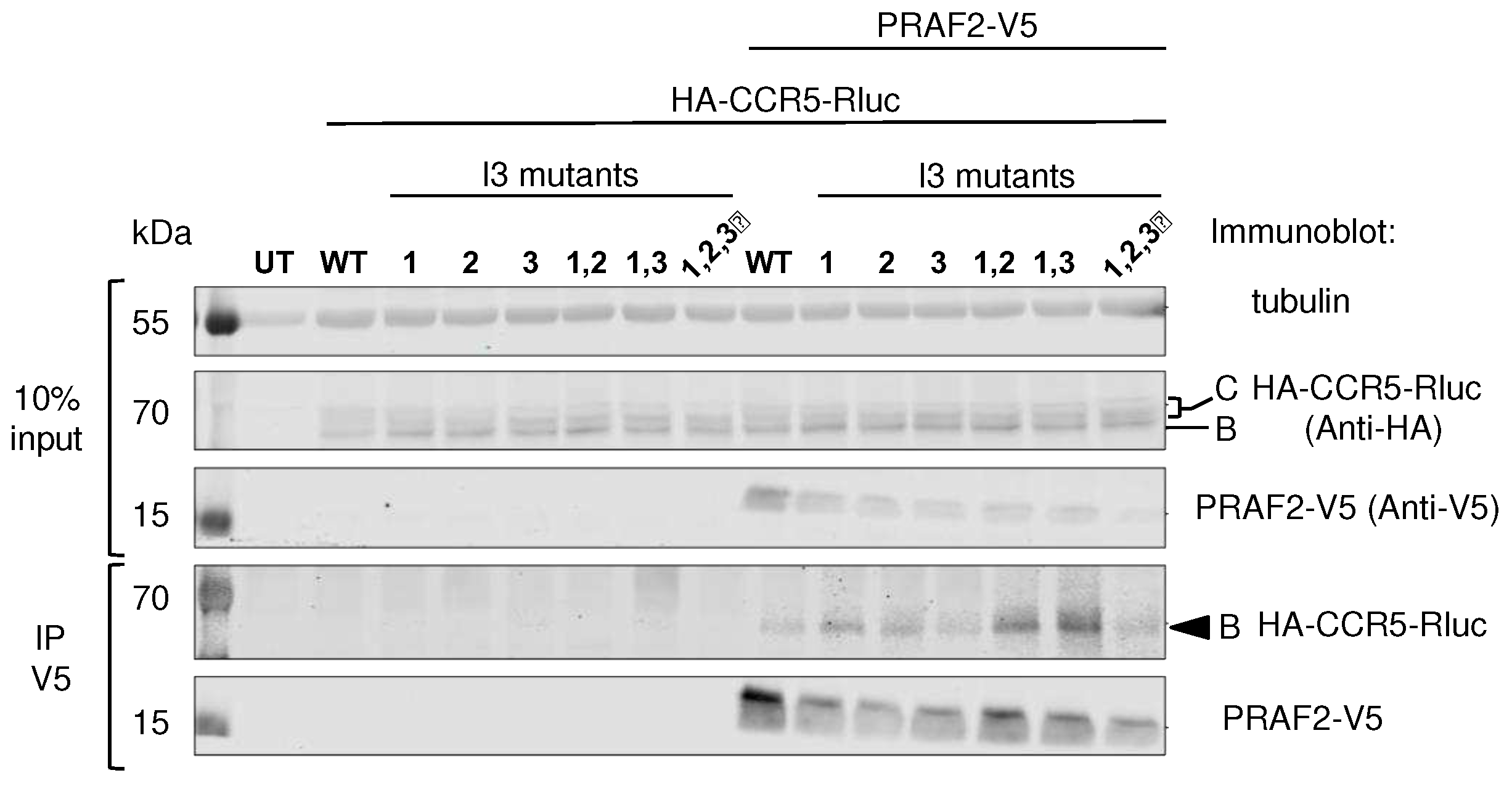

Co-immunoprecipitation experiments (

Figure 4) confirmed that PRAF2-V5 could interact with CCR5-Rluc and with all tested mutants, including CCR5 I3-1,2,3-Rluc, in which all di-leucine and arginine-based motifs were substituted.

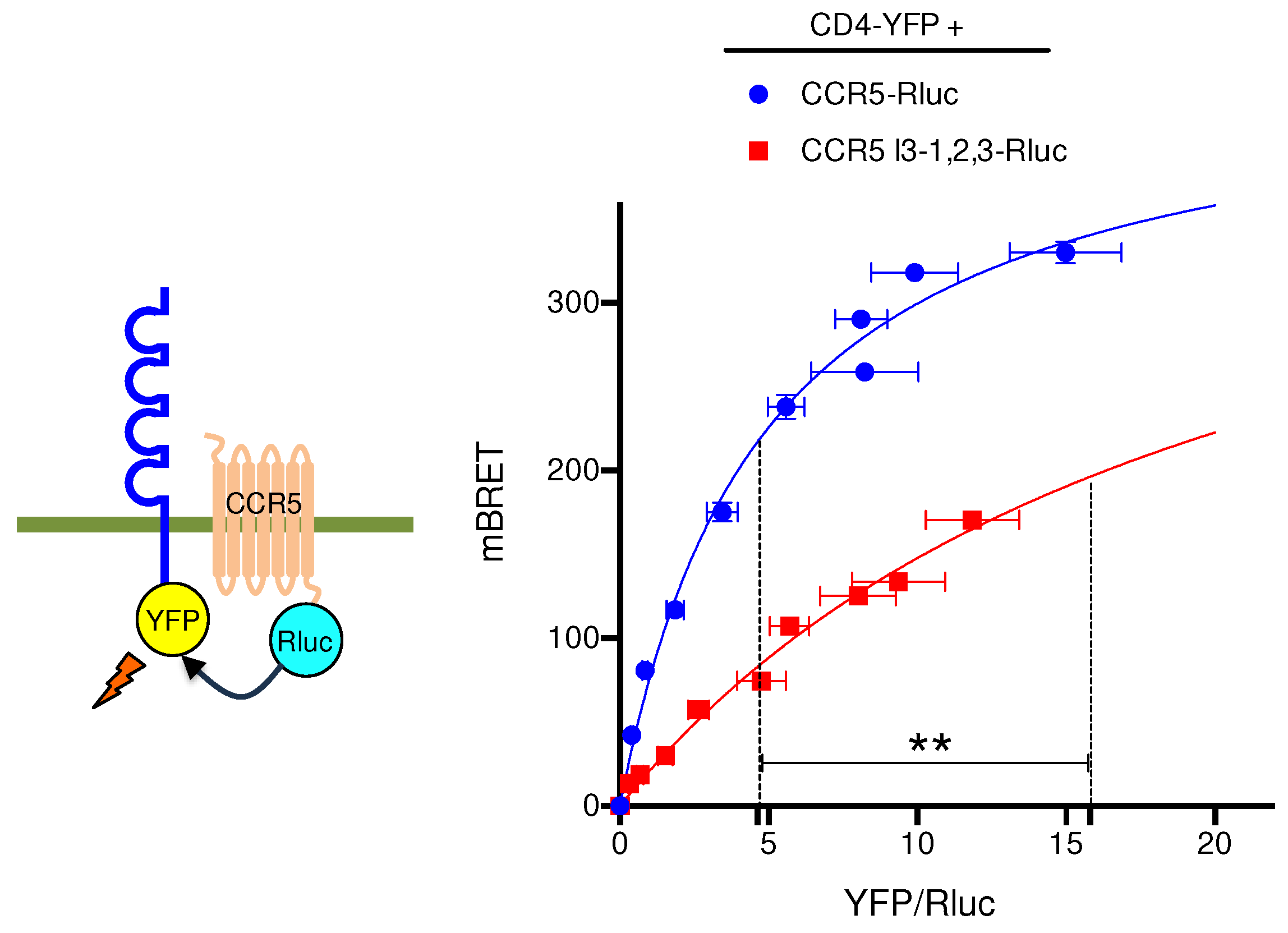

The massive retention observed with the CCR5 I3-1,2,3-Rluc mutant (

Figure 3A, brown curve) might be due to its export-incompetent conformation. Indeed, previous studies showed that CCR5 forms constitutive dimers [

32] and adopts distinct conformations, some of them allowing CCR5 dimers to be targeted to the cell surface [33, 34]. The HIV co-receptor CD4 was reported to enhance CCR5 surface delivery in primary T lymphocytes or when co-expressed in reconstituted cell systems [27, 35]. CD4-CCR5 interaction occurs within intracellular compartments suggesting that CD4 might stabilize a conformation allowing CCR5 to enter the export pathway. Based on this paradigm, we used CD4 as a conformational probe for CCR5 and CCR5 I3-1,2,3 in a BRET assay (

Figure 5). Confirming previous BRET-based studies of CCR5-CD4 interaction performed with inverted donor and acceptor pairs [

27], hyperbolic saturation of CCR5-Rluc was obtained with increasing concentrations of CD4-YFP. Using CCR5 I3-1,2,3-Rluc as BRET donor, saturation was also obtained but with a much higher BRET

50, indicative of a markedly reduced capacity of CD4 to associate with the CCR5 mutant. This result is consistent with either a reduced affinity of CD4 for CCR5 I3-1,2,3 or some segregation of CCR5 I3-1,2,3 out of the ER-exiting pathway, where CD4 is physiologically located.

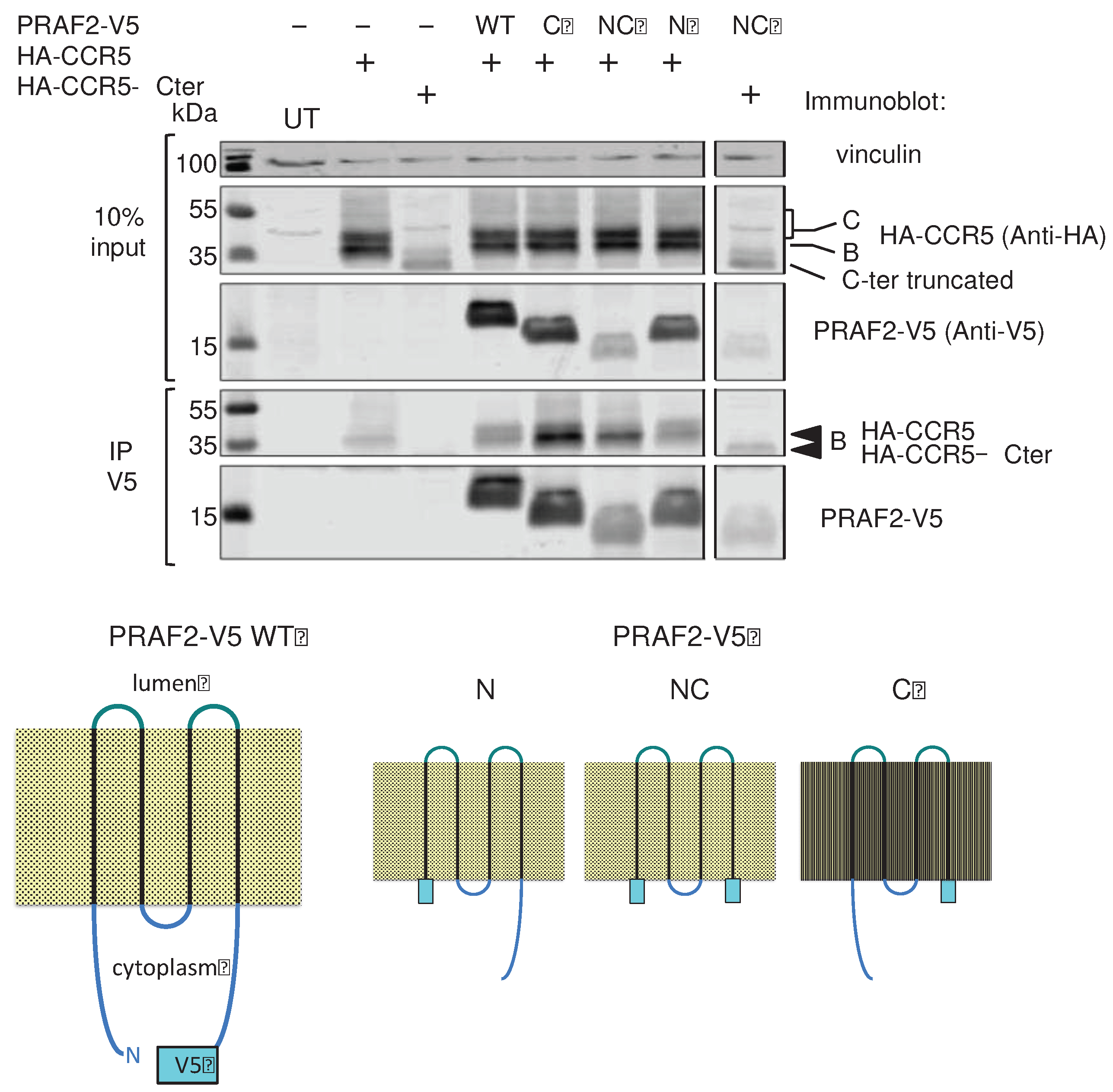

The observation that the largest intracellular loop and the C-terminus of CCR5 were not essential for the interaction with PRAF2 raised the hypothesis that the transmembrane domains of the receptor and PRAF2 might instead constitute their principal interface. Consistently, it was reported that transmembrane domains of CCR5, TM5 and TM6 in particular, were predominantly involved in the dimeric organization of the receptor, which is required for targeting CCR5 to the plasma membrane [

34]. V5-epitope-tagged PRAF2 mutants were constructed, lacking either the N- or the C-terminal intra-cytoplasmic region or both. These mutants were compared to wild type PRAF2-V5 for their interaction with CCR5 and CCR5-ΔCter in co-immunoprecipitation experiments (

Figure 6). PRAF2 and all tested truncated mutants, including the one lacking both cytoplasmic regions, could co-immunorecipitate CCR5. Moreover, the latter mutant could also co-immunorecipitate CCR5-ΔCter. Together with the observation above that LL and RXR motifs of the I3 are not involved in receptor interaction with PRAF2 (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), these data indicate that CCR5 and PRAF2 most likely interact via their TM domains.

3. Discussion

This study extends to CCR5 the range of plasma membrane polytopic proteins, whose cell surface targeting is regulated by PRAF2. As for GB1 and CFTR, CCR5 retention is dependent on PRAF2 concentration. A previous cartography of endogenous PRAF2 distribution revealed a marked variability in PRAF2 expression in the brain, PRAF2 being virtually absent in some areas, whereas other areas displayed very strong PRAF2 expression [

19]. Moreover, PRAF2 overexpression was reported in multiple cancers [18, 36]. The 60% reduction of CCR5 expression for a 2-fold enhancement of PRAF2 levels over basal values suggests a “physiological” regulation of CCR5 function through the modulation of PRAF2 concentration. Future studies will evaluate this hypothesis by measuring the regulation of endogenous PRAF2 expression in CCR5-expressing cells under different conditions of maturation or stimulation.

Inconsistent with the two-hybrid screen, which led to the identification of PRAF2 as a CCR5 interaction partner and regulator [

22], the deletion of CCR5 C-tail totally inhibited the cell surface targeting of the receptor and enhanced its propensity to associate with PRAF2. PRAF2 interaction might thus mechanistically participate in the protection against HIV infection of the individuals carrying mutant CCR5 receptors truncated of their carboxy-terminal tail [29, 30]. The substitutions of LL and RXR motifs of the I3 failed to enhance the cell surface export of CCR5, but impaired it instead. The maximal decrease of plasma membrane targeting was observed for CCR5 I3-1,2,3-Rluc, despite its propensity to associate with PRAF2-YFP, which was not significantly changed in BRET experiments, and its conserved co-immunoprecipitation with PRAF2-V5. Consequently, in contrast from what has been established for GB1 and CFTR, the interaction between CCR5 and PRAF2 likely involves their transmembrane domains instead of specific tandem LL-RXR motifs.

The HIV receptor CD4 was found constitutively associated with CCR5 in the plasma membrane of various cell types [24, 37, 38]. It was proposed that the interactions mediating this association involve the extracellular globular domain of CD4 (the first two Ig domains) and the second extracellular regions of CCR5, even in the absence of gp120 or any other receptor-specific ligands [25, 37, 39, 40]. Some studies showed the allosteric CD4-dependent regulation of the binding and signaling properties of CCR5 [

39]. Moreover, other investigations indicated that CD4 already interacts with CCR5 in the ER and plays the role of a private escort protein for this receptor, promoting its cell surface targeting [

27]. Here we found that the substitution of the di-leucine and RXR motifs of the third intracellular loop of CCR5 markedly impaired the propensity of interaction with CD4 in BRET experiments, providing a possible explanation for the markedly perturbed plasma membrane localization of the CCR5 I3-1,2,3-Rluc mutant, which is perhaps due to conformational rearrangement..

In a recent study, an enzyme-catalyzed proximity labeling experiment using the TurboID approach, aimed at characterizing the PRAF2 interactome in the ER, showed an enrichment of proteins involved in “vesicular trafficking”, with the highest enrichment being for COPII-coated vesicles components [

21]. A preferential proximity of PRAF2 with the Sec machinery was found, including the Sec23/24 heterodimer involved in SNARE and cargo molecules selection [

41], indicative of the possible control of proteins to be transported to the cell surface near ERES, from which COPII-vesicles bud. High resolution fluorescence microscopy studies confirmed the proximity of PRAF2 with a significant fraction of COPII vesicles, marked by anti-Sec31 (a COPII component) antibody but without superposition, supporting a model where PRAF2 retains cargo proteins immediately upstream of their loading into vesicles leaving at ERES [

21]. Interestingly, a mass spectrometry-based analysis of macrophage proteins interacting with CD4 identified several proteins composing COPII-vesicles or regulating their fission from ER membranes [

42]. Sec23/24 was included in this group, suggesting that CD4 might mediate the recruitment of CCR5 in COPII vesicles by bridging the receptor and the Sec23/24 cargo receptor.

In conclusion, PRAF2, likely by interacting via its TM domains with those of CCR5, inhibits its cell surface export. In cells that express (endogenous or exogenous) CD4, CCR5 establishes an interaction with it, involving its extracellular domain and its I3. The I3-mediated interaction with CD4 might be either direct or via a specific conformation stabilized by the intact I3. Physiologically, PRAF2 and CD4 have opposite roles on the same process, inhibiting or promoting the recruitment of CCR5 into COPII vesicles. It remains to be established if these regulating molecules act on the same or on distinct pools of vesicles leaving the ERES.

4. Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Human Embryonic Kidney 293 (HEK-293) cells (ATCC®) was maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma) and 1% Penicillin–Streptomycin (Gibco) at 37 °C in 5% CO2 humidified chamber.

Site-directed mutagenesis, DNA constructs

The CCR5-Rluc construct was described previously [

32]. Construction of HA-CCR5-ΔCter-Rluc, GAP43-YFP, PRAF2-YFP and PRAF2-V5 plasmids were described previously [

20]. PRAF2-V5, ΔN, ΔN and ΔNC truncated mutants were prepared by PCR amplification as follows: for ΔN the forward primer included a new ATG immediately before the first amino-acid residue of TM1. For ΔC the reverse primer included a stop codon after the last amino-acid residue of TM4. These primers were used together to generate the coding region of ΔNC.

QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Agilent) was used to perform mutagenesis following manufacturer’s protocol, and all mutated plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing. The substitution of LL and RXR motifs by alanine residues in the third intracellular loop of CCR5 were obtained using this procedure. HA-CCR5-ΔCter was obtained from the HA-CCR5-ΔCter-Rluc by the insertion in the CCR5 coding region of a STOP codon immediately after the sequence coding for the glycine at position 301.

Antibodies, reagents and drugs

The following monoclonal antibodies (mAb) or polyclonal antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation or immunoblotting experiments: Anti-JM4/PRAF2 rabbit polyclonal antibody (ab53113; Abcam), Anti-V5 mouse monoclonal antibody (R960-25; ThermoFischer), Anti-β-Tubulin rabbit monoclonal antibody (mAB #2128; Cell Signaling), Anti-Vinculin mouse monoclonal antibody (V9131; Sigma) and Anti-HA rabbit monoclonal antibody (mAb #3724; Cell signaling). The following secondary antibodies were used in Western blot experiments: IR Dye® 680 RD Donkey anti-Rabbit antibody (926–68073; Li-cor), IR Dye® 800 CW Donkey anti-Rabbit (926–32213; Li-cor), IR Dye® 800 CW Donkey anti-Mouse (925–32212; Li-cor), IR Dye® 680 RD Donkey anti-Mouse (925–68072; Li-cor).

The following reagents were used: Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (14190–094; Gibco), Hanks’s balanced salt solution (14025–050; Gibco), EcoTransfect (ET11000; OZBiosciences), coelenterazine h (R3078b; Interchim), cOmplete EDTA-free protease tablets (05056489001; Roche), Protein G Sepharose 4 fast flow (17061801; FischerScientific), Pierce™ BCA protein assay (23225; ThermoFisher).

Transfections

The indicated plasmids were transiently transfected in HEK-293 cells using the EcoTransfect (OZBiosciences) transfection reagent following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

For immunoprecipitation experiments, cells were washed twice and detached in PBS 1X. Cells were centrifuged at 1700xg at 4°C for 4min and then resuspended in a lysis buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4; adjusted with NaOH), 250 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 10% (v/v) glycerol and cOmplete protease inhibitor mix. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 18000xg at 4°C for 15 min. Cell lysates were pre-cleared with protein-G beads for 3h at 4°C and then incubated with anti-V5 antibody (ThermoFisher, R960-25) overnight at 4°C. Protein-G beads were pre-incubated for 3-5h at 4°C in Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA). Immune complexes were collected the following day by incubating with Protein-G beads for 3h at 4°C. The beads were subsequently washed three times and eluted in 2X sample loading buffer prepared from a 5X stock (250mM Tris 0,75M pH 6.8; 10% SDS; 50% glycerol; 0,1% bromophenol blue; 10% 2 mercapoethanol) at 37 °C for 15 min. The eluted samples were further analyzed by immunoblot.

For immunoblotting, the cells were lysed in the same lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4; adjusted with NaOH), 250 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 10% (v/v) glycerol and cOmplete protease inhibitor mix). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 18000xg at 4 °C for 15 min and eluted in 1X sample loading buffer.

The total amount of protein was measured using the Pierce™ BCA protein assay (Thermo Fischer, 23225), and 25–50 µg or 500-1000µg of protein, for immunoblotting or immunoprecipitation, respectively, was separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The samples were loaded in a 12% gel to separate CCR5 (≈ 35-55 kDa or ≈ 70-100kDa when fused to Rluc) and PRAF2 (≈10-20 kDa). Separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were incubated in 5% skimmed milk in Tris buffered Saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1h at room temperature, followed by incubation with the respective primary antibodies (dilution used 1:1000) at 4 °C overnight. The next day the membranes were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies from Li-cor for 1h at room temperature and labeled material visualized/analyzed in the Odyssey CLx Imager.

BRET saturation assays

The BRET procedure was fully described previously [

43]. Briefly, HEK-293 cells were transfected with a constant amount of donor plasmid and increasing amount of acceptor plasmid; the total amount of DNA was kept constant with empty vector DNA. Cells were washed in PBS and detached in HBSS. Cells were then plated in 96 well plates in triplicates and coelenterazine h (5 µM) was added. The luminescence (filter 485±10 nm) and fluorescence (filter 530±12.5nm) signals were measured simultaneously in a Mithras fluorescence-luminescence detector (Mithras2 LB 943 multimode Reader). The calculated BRET ratio is the fluorescence signal over the luminescence signal and the specific BRET is obtained by subtracting the signal from cells expressing donor alone. The specific BRET is then multiplied by 1000 to be expressed as milli-Bret. Specific BRET values were then plotted as a function of [(YFP−YFP0)/Rluc] where: YFP is the fluorescence measured after excitation at 480 nm; YFP0 is the background fluorescence measured in cells not expressing the BRET acceptor and Rluc is the luminescence measured after coelenterazine h addition. The data were analyzed in GraphPad Prism in a nonlinear regression equation assuming a single binding site, and the BRET

max and BRET

50 were calculated.

Quantifications and statistical analysis

For statistical analysis of BRET curves, the one-site specific-binding model was compared using extra sum-of squares F Test for BRETmax and BRET50. The null hypothesis is that BRETmax and BRET50 were statistically the same between each data set. The null hypothesis was rejected if the p value was less than 0.05. The exact p value is reported for each experiment. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data sets were compared with one-way ANOVA and multiple comparison test (Dunnett’s or Tukey’s) were performed in GraphPad Prism (Prism 9.0).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.; methodology, S.M., H.E., M.G.H.S., E.D.-S.; validation, S.M., E.D.-S.; formal analysis, E.D.-S.; investigation, E.D.-S.; data curation, E.D.-S; S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, S.M., H.E., M.G.H.S., E.D.-S; supervision, S.M.; project administration, S.M.; funding acquisition, S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.