1. Introduction

Dementia can be broadly classified into Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and vascular dementia based on its mechanism of occurrence. AD is the most prevalent and rapidly progressive type of dementia, mainly affecting individuals over 60 years of age, accounting for 50–60% of all dementia cases [

1]. AD can be further subdivided into subtypes triggered by environmental and physiological factors. External factors, including age, genetic determinants, and environmental factors, can lead to toxic effects, whereas internal factors involve a decline in neurotransmitters due to reduced acetylcholine (ACh) levels, neuroinflammation initiated by cytokines, cytotoxicity due to the aggregation of beta-amyloid (Aβ) protein and hyperphosphorylated tau protein, and neuronal demise induced by oxidative stress-generated free radicals. Accumulation of Aβ, an aberrant protein within nerve cells, in the brain results in synaptic damage and activation of peripheral glial cells, ultimately culminating in brain cell death mediated by various inflammatory, apoptotic, and oxidative stress responses. ACh is a neurotransmitter required for cognitive functions such as learning and memory [

2]. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors serve as therapeutic agents that alleviate the symptoms of cognitive decline in dementia by enhancing cholinergic neurotransmitters [

3]. Recent studies have investigated the potential inhibitory effects of substances derived from natural products and food materials against ACh-degrading enzymes. Scopolamine, a muscarinic cholinergic receptor antagonist, inhibits cholinergic neuronal function in the central nervous system, leading to oxidative stress and subsequent cognitive impairment [

4], offering a useful drug to stimulate cholinergic memory loss in animal models, thereby facilitating studies on the efficacy of various drugs and natural compounds on protecting memory and cognitive functions [

5].

Exercise has been shown to have a positive effect on neurodegenerative diseases through the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), inhibition of neuronal cell death, and promotion of neurogenesis, collectively enhancing cognitive functions related to memory and learning [

6,

7,

8]. Among various exercises, treadmill exercise has been shown to enhance mitochondrial function and promote autophagy, contributing to the breakdown of abnormal proteins and the maintenance of cellular homeostasis, ultimately fostering positive effects on learning and memory [

9,

10]. In particular, one study indicated that 4 weeks of endurance exercise had a positive impact on adaptation of the skeletal muscles to physical activity, thereby increasing the expression of proteins involved in mitochondrial biosynthesis and mitophagy in mice [

11].

Whey protein is a valuable by-product of the cheese-making process accounting for approximately 20% of total milk proteins. Whey protein is quickly absorbed by the body and contains a large number of branched-chain amino acids that are widely distributed in the muscles [

12]. Enzymatic hydrolysis is a common method utilized to improve the functional and nutritional properties of proteins [

13,

14]. The peptides produced by protein hydrolysis have smaller molecular weights and altered secondary structures compared to those of the intact proteins, with potential to enhance physiological functions, including digestive ability, and to mitigate allergic reactions [

15]. Whey protein hydrolysate (WPH) has been demonstrated to have a range of beneficial effects, including increasing the body’s metabolic rate, promoting intestinal health, regulating blood sugar levels, and managing blood pressure. A recent study demonstrated that WPH containing a glycine-threonine-tryptophan-tyrosine peptide improved cognitive function in mice [

16]. Nevertheless, there is a lack of research on the cognitive function improvement resulting from the combination of peptides derived from WPH and aerobic exercise.

To address this question, in this study, we evaluated the individual and synergistic effects of administration of WPH containing the LDIQK peptide and treadmill exercise on cognitive function in mice with scopolamine-induced cognitive decline and further explored the underlying mechanism.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals and Design

Six-week-old male specific pathogen-free C57BL6 mice weighing 20–25 g were purchased from OrientBio (Seongnam, Korea). The animals were housed in an environment with a temperature of 23 ± 3°C, relative humidity of 50 ± 10%, ventilation frequency of 10–15 times/h, 12-h light/dark cycle (08:00 to 20:00), and illuminance of 150–300 Lux. During the 1-week acclimatization period, the animals were allowed to consume solid laboratory-grade food (Cargil Agri Purina, Inc., Seongnam, Korea) and drinking water ad libitum. After the acclimatization period, the mice were divided into seven experimental groups with eight mice per group: the normal (NOR), scopolamine control (CON), scopolamine + exercise (EXR), scopolamine + WPH (WPH_L, WPH_H), and scopolamine + exercise + WPH groups (EWPH_L, EWPH_H). The mice in the WPH groups were orally administered 100 (WPH_L/EWPH_L) or 200 mg/kg (WPH_H/EWPH_H) WPH per day based on body weight. Mice in the exercise groups were subjected to treadmill exercise five times per week for 30 min at a speed of 15 m/min during the four-week experimental period. To induce cognitive impairment, 1 mg/kg scopolamine (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) was administered intraperitoneally 30 min before the cognitive tests.

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Korea University (KIACUC-2022-0076).

2.2. Y-Maze Test

The Y-maze test is a behavioral test commonly used to assess short-term spatial cognition [

17]. This assessment involves the use of a Y-shaped maze constructed of white plastic material. The maze used in this study comprised three arms, each measuring 50 cm in length, 20 cm in height, and 10 cm in width. These arms were folded at an angle of 120° to each other. After designating each branch as A, B, or C, the mouse was placed at the beginning of the maze and allowed to move freely through the maze for 60 s. The number and order of entries into each part of the maze were measured to evaluate the change in behavior. The scoring system for this assessment involved awarding one point when the mouse sequentially entered all three main areas (A, B, and C) in the correct order. However, no points were awarded if entries occurred in a non-sequential manner. The test conductor established the basic conditions for learning and memory assessment criteria and validated the test method in terms of rationality, accuracy, and reproducibility.

2.3. Novel Object Recognition Test

The novel object recognition test was performed in a white polyvinyl plastic box (30 × 30 × 30 cm). The mice were allowed to explore the box freely for 10 min for the first 2 days for acclimation [

18]. On the third day of the experiment, the mice were injected with WPH at 100 or 200 mg/kg 1 h before placing them in the box. All experimental groups except the NOR group were administered an intraperitoneal dose of scopolamine (1 mg/kg) dissolved in a 0.9% saline solution 30 min before the start of the experiment, placed in the front center of the box, and then presented with identical objects at equal distances (5 cm) from both diagonal vertices of the box and allowed to explore the objects freely for 5 min. After 24 h of exploration, one of the objects in the box was replaced with a new object of a different shape and the mouse was allowed to explore the object freely for another 5 min. During these 5 min, we measured the time that the mouse exhibited exploratory behaviors such as touching, sniffing, and licking familiar and novel objects. The object preference ratio and discrimination indices were then calculated by recording the number of touches between the familiar object and the novel object and comparing the total number of touches of the objects. A higher discrimination index indicates greater recognition of novel objects.

2.4. Measurement of ACh Content

The ACh content in the brain tissue was measured using the modified method of Vincent and Newsom-Davis [

19]. In brief, the harvested brain tissue was homogenized in 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), centrifuged (10,000 ×

g, 10 min), and the supernatant was obtained for analysis. Alkaline hydroxylamine reagent (3.5 N sodium hydroxide and 2 M hydroxylamine in HCl) was added to the supernatant and left to react at room temperature for 1 min, followed by the addition of 0.1 N HCl in 0.5 N HCl (pH 1.2) and 0.37 M FeCl

3. The absorbance was then measured at a wavelength of 540 nm.

2.5. Measurement of AChE Activity

AChE activity was measured using an AChE activity assay kit (BM-ACH-100; BIOMAX, SEOUL, South Korea) according to the manufacturer instructions. The brain tissue was homogenized in 1 mL of PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma Aldrich) and centrifuged (12,000 ×g 10 min) to obtain the supernatant. Subsequently, 50 μL of the supernatant was mixed with the reaction mixture containing assay buffer, enzyme mix, substrate solution, and the probe, and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm with a microplate reader in kinetic mode at 37°C for 30 min in the dark.

2.6. Determination of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Malondialdehyde (MDA) Contents

To measure ROS levels, 1 mL of 40 mM Tris–HCl buffer was added to 50 mg of brain tissue. The tissues were homogenized and centrifuged to collect the supernatant. Subsequently, 500 μL of 40 mM Tris–HCl buffer and 10 μM of the fluorescent probe 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) were added to 50 μL of the supernatant and reacted for 30 min at 37°C. Fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 482 nm and an emission wavelength of 535 nm to quantify the ROS content in the tissue by comparison with an ROS standard curve.

The MDA content in the brain tissue was analyzed using the OxitecTM TBARS Assay kit (BIOMAX Co, Ltd., UK) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 1 mL of PBS was added to 100 mg of brain tissue, which was homogenized and centrifuged to collect the supernatant. Subsequently, 200 μL of the indicator solution was added to 200 μL of the supernatant and reacted at 65°C for 45 min. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm and compared to the MDA standard curve to quantify the MDA content in the tissue.

2.7. Western Blotting

Approximately 50 mg of brain tissue was homogenized in 1000 μL of lysis buffer [200 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaF, 1% NP40, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM Na3VO4, and protease inhibitor cocktail] and centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 5 min at 4°C to recover the supernatant.

The sample was subjected to protein quantification by the bicinchoninic acid method and 30 μg of protein was subjected to electrophoresis on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel. After transfer to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane, the blots were blocked with 5% skim milk and bovine serum albumin for 1 h and probed with the following primary antibodies for 16 h at 4°C: alpha-tubulin (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Cat. #2144), Bax (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Cat. #2772), Bcl-2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Cat. #2876), PARP (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Cat. #9553), BDNF (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Cat. #47808), phosphor (p)-tau (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Cat. #29957), tau (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Cat. #4019), and choline acyltransferase (ChAT; abcam, ab183591) antibodies. After washing three times with Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20, the blot was treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Cat. #7074) and reacted for 2 h at room temperature, followed by dispensing of SuperSignal™ Western Blot Enhancer (Thermo Scientific, Cat. #46641) and protein bands were identified using the FluorChem M Fluorescent Western Imaging System (Protein Simple, California, USA). The antibodies used were diluted in 5% skim milk and bovine serum albumin, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.8. Gut Microbiome Analysis

DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene sequencing of double-stranded DNA were performed from 100 mg of cecum samples using the QIAamp Power Fecal Pro DNA Kit (QIAGEN, Frederick, MD, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The DNA concentration of all samples was adjusted to 5 ng/µL, and the uniformly concentrated DNA was subjected to two-step polymerase chain reaction using the primer set 341F and 806R to amplify the V3–V4 variable region of the 16S rRNA gene. Illumina MiSeq (Illumina) library construction was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol and sequencing was performed by Macrogen (Seoul, Korea).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

SPSS software (version 12.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to analyze the experimental data. The data of each experiment are expressed as percentages or mean ± standard error of the mean as appropriate, and all measurements were subjected to one-way analysis of variance followed by the post-hoc Tukey test to evaluate significance. Statistical significance was judged at a threshold of p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the effects of treadmill exercise and WPH intake on scopolamine-induced cognitive dysfunction in mice. Scopolamine, a muscarinic cholinergic receptor antagonist, induces cognitive impairment through cholinergic dysfunction and oxidative stress in the brain [

20]. Therefore, animal models treated with scopolamine serve as reliable representations of cognitive impairment, and play a crucial role in investigations aimed at assessing the effectiveness of substances for the prevention and treatment of AD and uncovering their underlying mechanisms [

21].

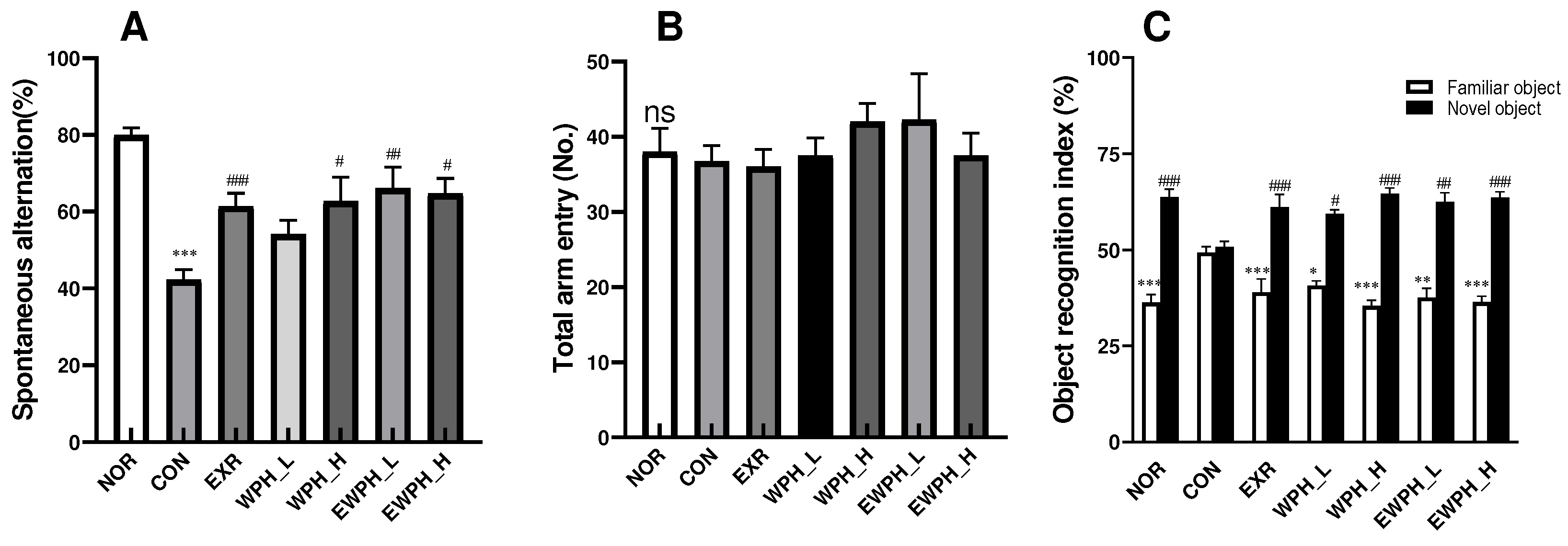

We found that WPH administration and treadmill exercise improved scopolamine-induced memory impairment in behavioral tests, including the Y-maze and novel object recognition tests. The Y-maze test is a straightforward method for assessing short-term spatial memory in experimental animals, which involves placing animals in the Y-maze and quantifying the number of sequential entries they make [

22]. We found that scopolamine treatment significantly decreased spontaneous alternation behavior compared to that of the untreated NOR group. In addition, the EXR group, which received treadmill exercise; the WPH_L and WPH_H groups, which were supplemented with WPH; and the EWPH_L and EWPH_H groups, which received both exercise and WPH, showed recovery of alternation behavior at levels similar to those in the NOR group, confirming that memory was improved. The novel object recognition test has been widely used to study behavior and brain function in rats and mice, as well as in memory research. There was no significant difference in the time required to explore the novel and familiar objects after scopolamine administration [

23]. However, the time spent exploring novel objects was significantly longer than the time spent exploring familiar objects in the EXR, WPH_L, WPH_H, EWPH_L, and EWPH_H groups. This suggests that exercise and WPH administration mitigate scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment. In our previous work (revision in progress), WPH has demonstrated its ability to protect neuronal cells from oxidative stress conditions, a finding that aligns with the current study’s data showcasing improved cognitive function. LDIQK, a WPH-derived pentapeptide (leucine-aspartate-isoleucine-glutamine-lysine), has been isolated and confirmed as an active principle for neuroprotective effect (revision in progress). The present study substantiates the positive impact of WPH containing LDIQK on cognitive function in an animal model and introduces an additional intervention: exercise. This dual approach is believed to create a synergistic effect, further enhancing ability. Exercise, a well-established contributor to overall health, is known to deliver a fresh supply of oxygen and nutrients to the brain by boosting blood flow. This physiological boost acts as a power-up for cognitive function, supporting optimal brain performance [

24]. Furthermore, exercise has been reported to promote the release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin, influencing mood and cognitive process [

25]. By comparing the neuroprotective effects of WPH with the cognitive benefits of exercise, our study suggests a synergistic relationship that could lead to a more significant improvement in cognitive ability. This dual intervention approach provides a comprehensive strategy of enhancing brain health and function.

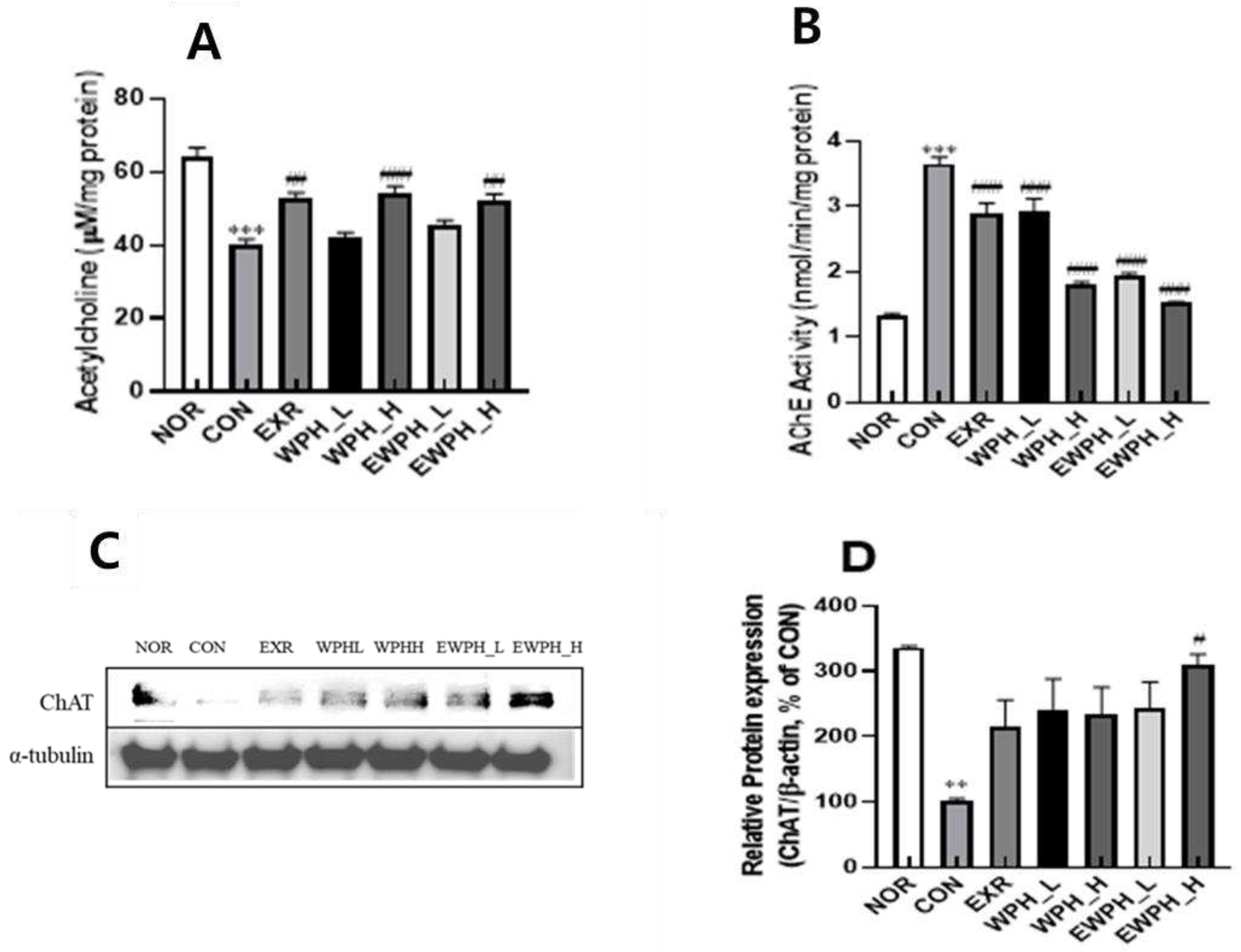

The cholinergic nervous system plays a major role in cognition and memory, and scopolamine has been shown to increase AChE levels and decrease ACh and ChAT levels [

26]. ACh is a major neurotransmitter and regulator in the nervous system, which is considered to play an important role in cognitive functions such as learning and memory at the neuromuscular junction and in the parasympathetic nervous system [

27]. Increased activity of enzymes such as AChE and butyrylcholinesterase in the brain leads to cholinergic dysfunction by breaking down the neurotransmitter ACh into choline and acetyl-coenzyme A, which contributes to impaired memory and cognitive function [

28]. In this study, we found that treadmill exercise and WPH administration significantly decreased the activity of AChE and increased the protein expression of ChAT, leading to an increase in the ACh concentration. These effects of exercise and WPH administration on ACh, AChE, and ChAT correlated with the results of the behavioral tests (Y-maze and novel object recognition), showing an increase in spontaneous alternation and the novel object discrimination index.

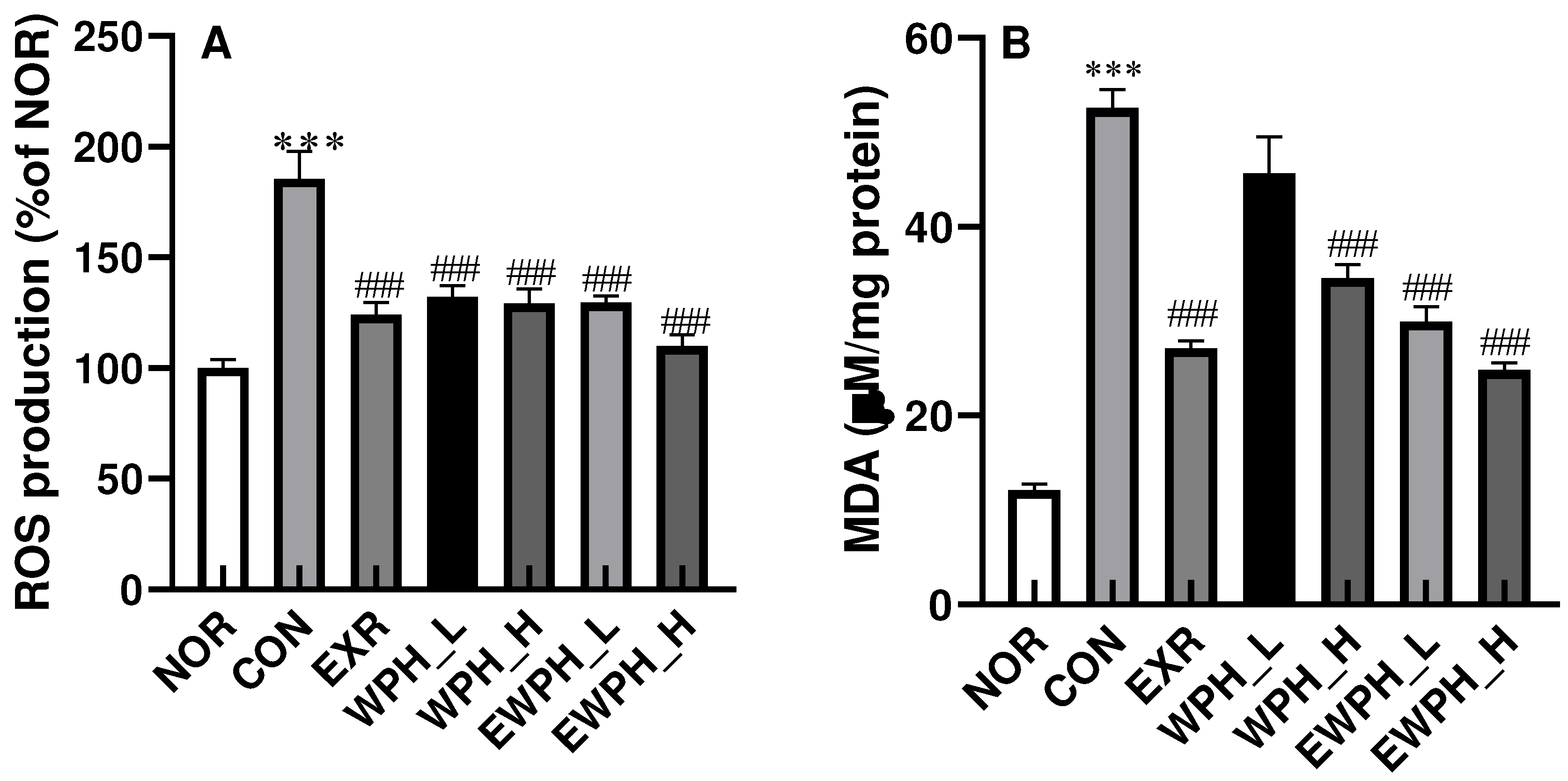

Along with its involvement in cognitive function, ACh is closely associated with oxidative stress in the brain. Given the abundance of unsaturated fatty acids in the brain tissue and their susceptibility to oxidative stress, excessive production of free radicals leads to the accumulation of lipid peroxides, protein denaturation, DNA oxidation, and subsequent cell damage, thereby hindering physiological activities [

28]. In particular, oxidative stress leads to the peroxidation of unsaturated fatty acids surrounding nerve cells and an increase in the activity of AChE, which promotes the degradation of ACh, resulting in impaired neurotransmission and, ultimately, a decrease in memory and learning ability. The findings of this study indicated that both exercise and WPH administration significantly reduced scopolamine-induced ROS and MDA levels. These results suggest that treadmill exercise and WPH improve cognitive function by inhibiting ACh degradation through a reduction of oxidative stress.

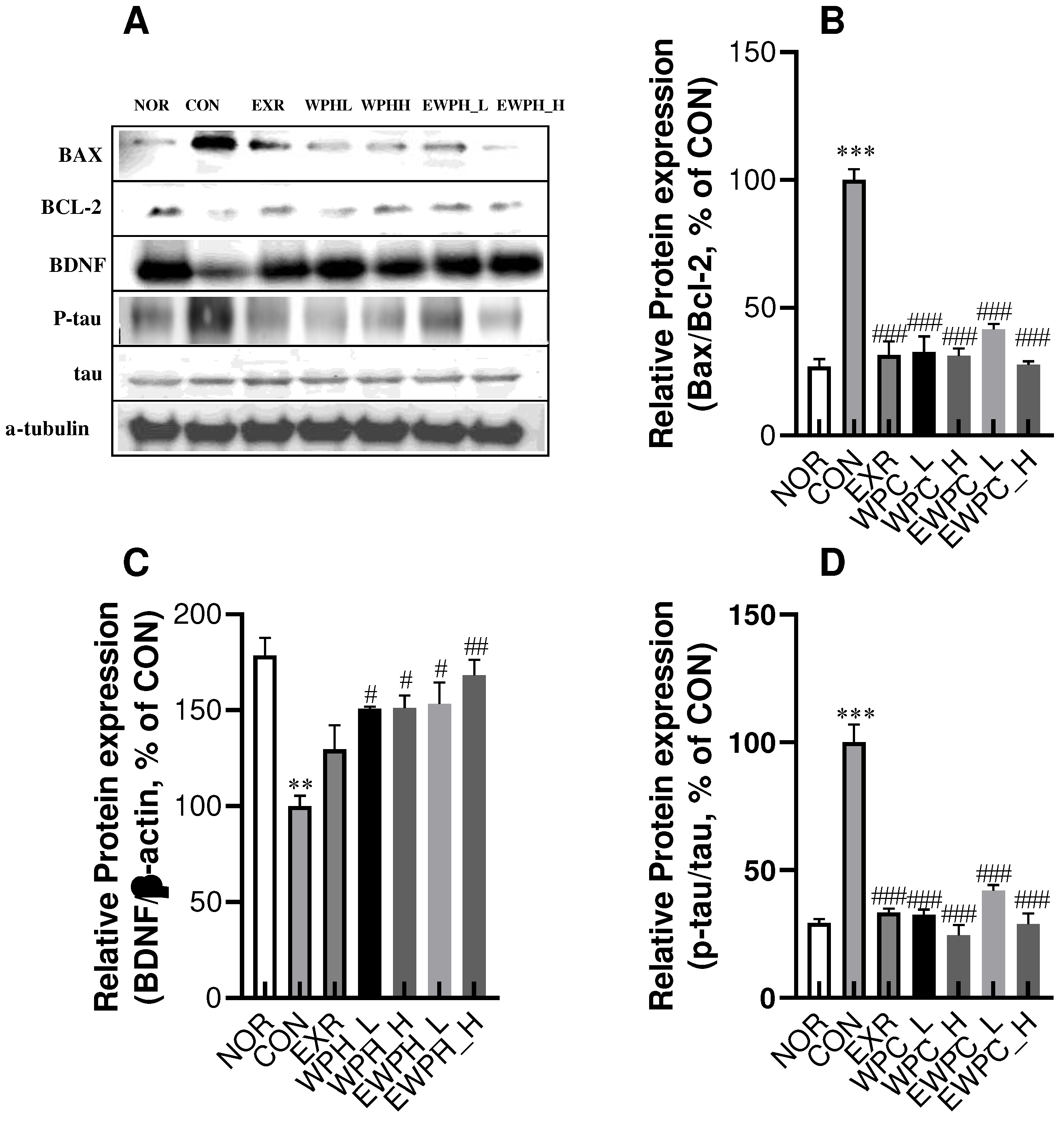

The Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, which is increased by oxidative stress, is also an important factor in the regulation of apoptosis [

29]. Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and related factors inhibit apoptosis, whereas Bax, Blk, and Bad promote apoptosis. Bax translocates to the mitochondria, where it becomes an activated monodimer and promotes apoptosis; this Bax-induced cell death pathway is inhibited by its heterodimerization with Bcl-2. Previous studies linking exercise to synaptic plasticity and cell proliferation have shown that exercise increases the expression of Bcl-2, an anti-apoptotic marker, and proteins involved in synaptic efficacy and learning in key brain regions [

30]. By contrast, exercise inhibits the expression of Bax, a member of the caspase family acting downstream of the proapoptotic pathway and a major promoter of cell death, thereby alleviating cognitive dysfunction. The results of this study demonstrated that treadmill exercise and WPH administration (100 and 200 mg/kg) significantly reduced the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio. These results implied that treadmill exercise and WPH inhibited apoptosis to exert positive effects on cognitive function.

One of the most prominent pathological features of AD is the accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles due to hyperphosphorylated tau protein in the brain, which is toxic to neurons [

31]. Additionally, the deposition of tau protein leads to oxidative stress, resulting in extensive neuronal destruction. The destruction of nerve cells in turn causes changes in brain structure and function, leading to cognitive decline [

32,

33,

34]. In particular, pronounced brain atrophy has been observed in the brains of patients with AD, and the administration of scopolamine has been reported to cause a decrease in brain weight along with a decline in overall cognitive function [

35]. A recent study showed that whey protein administration reduced the high hyperphosphorylation levels of tau protein in aged rats [

35], and another study demonstrated that treadmill exercise inhibited tau protein hyperphosphorylation in tau transgenic mouse models [

36]. The results of the present study showed that four weeks of moderate-intensity treadmill exercise and WPH administration at concentrations of 100 and 200 mg/kg significantly inhibited tau protein hyperphosphorylation. The inhibition of p-tau by exercise and WPH administration may contribute to a reduction in neuronal apoptosis.

BDNF is a neurotrophic factor that regulates neuronal growth, increases the activity of acetylcholine synthase in the central nervous system, enhances synaptic plasticity, and is directly involved in memory storage and utilization [

38,

39,

40]. Notably, transgenic mice with reduced BDNF expression showed impaired synaptic function, long-term memory, and learning, and BDNF expression in the brain was found to be reduced in patients with AD [

41]. Consistently, in the present study, we found that BDNF protein expression was significantly reduced in the CON group following scopolamine administration. However, when WPH was administered in combination with treadmill exercise, BDNF expression significantly increased. This increase in BDNF levels after exercise and WPH administration may also be associated with a reduction in apoptosis and p-tau.

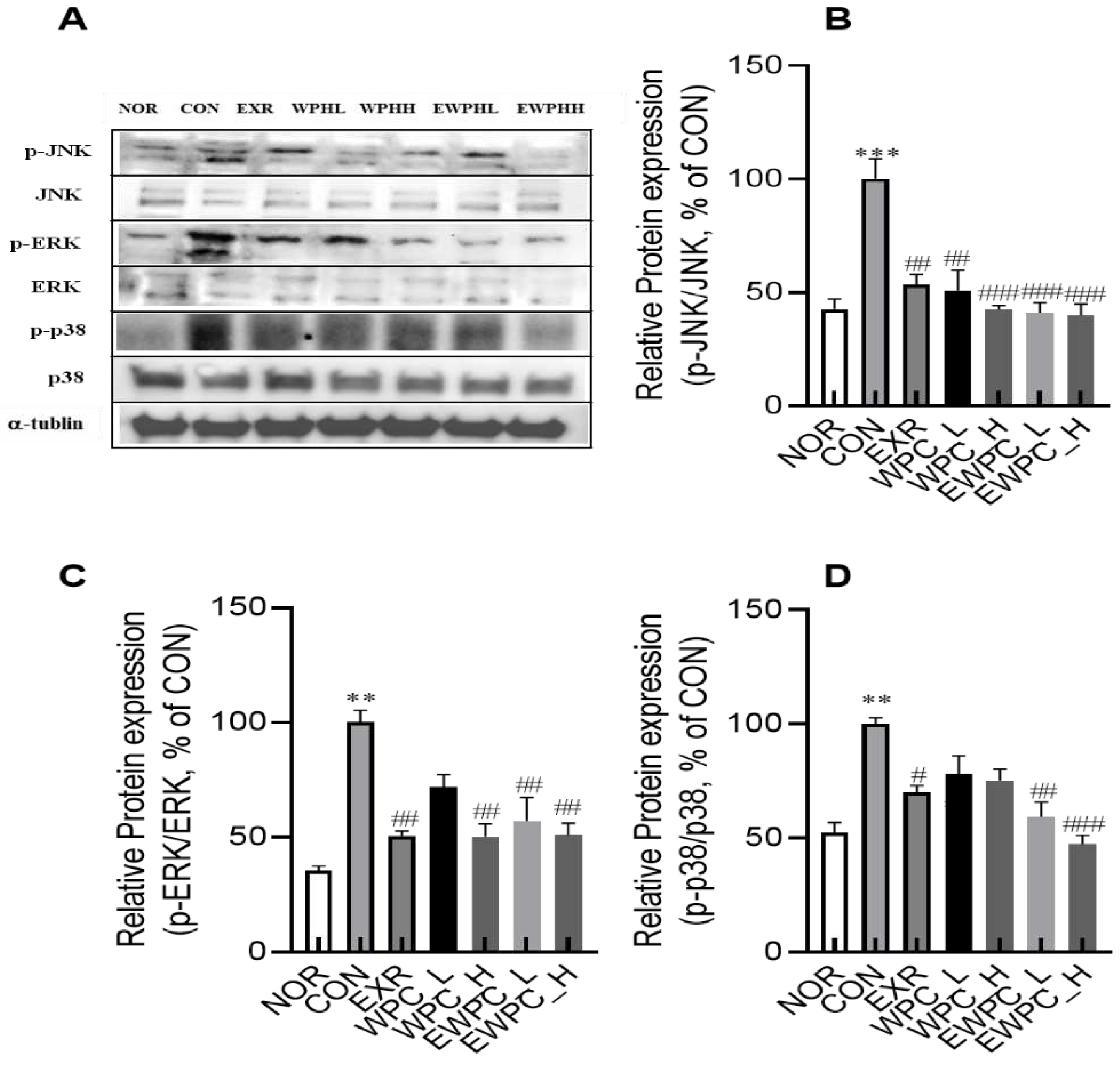

Under oxidative stress, MAPKs are signal transducers that regulate cell death [

42]. Phosphorylation of MAPK proteins by scopolamine leads to an elevated Bax/Bcl-2 ratio [

42]. Activation of the MAPK pathway (including ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 MAPK) is one of the markers observed in patients with AD [

43]. Moderate-intensity treadmill exercise and WPH administration significantly reduced MAPKs activation in scopolamine-induced mice. These results suggest that whey protein supplementation and treadmill exercise are effective in improving cognitive function by inhibiting the scopolamine-induced activation of MAPKs.

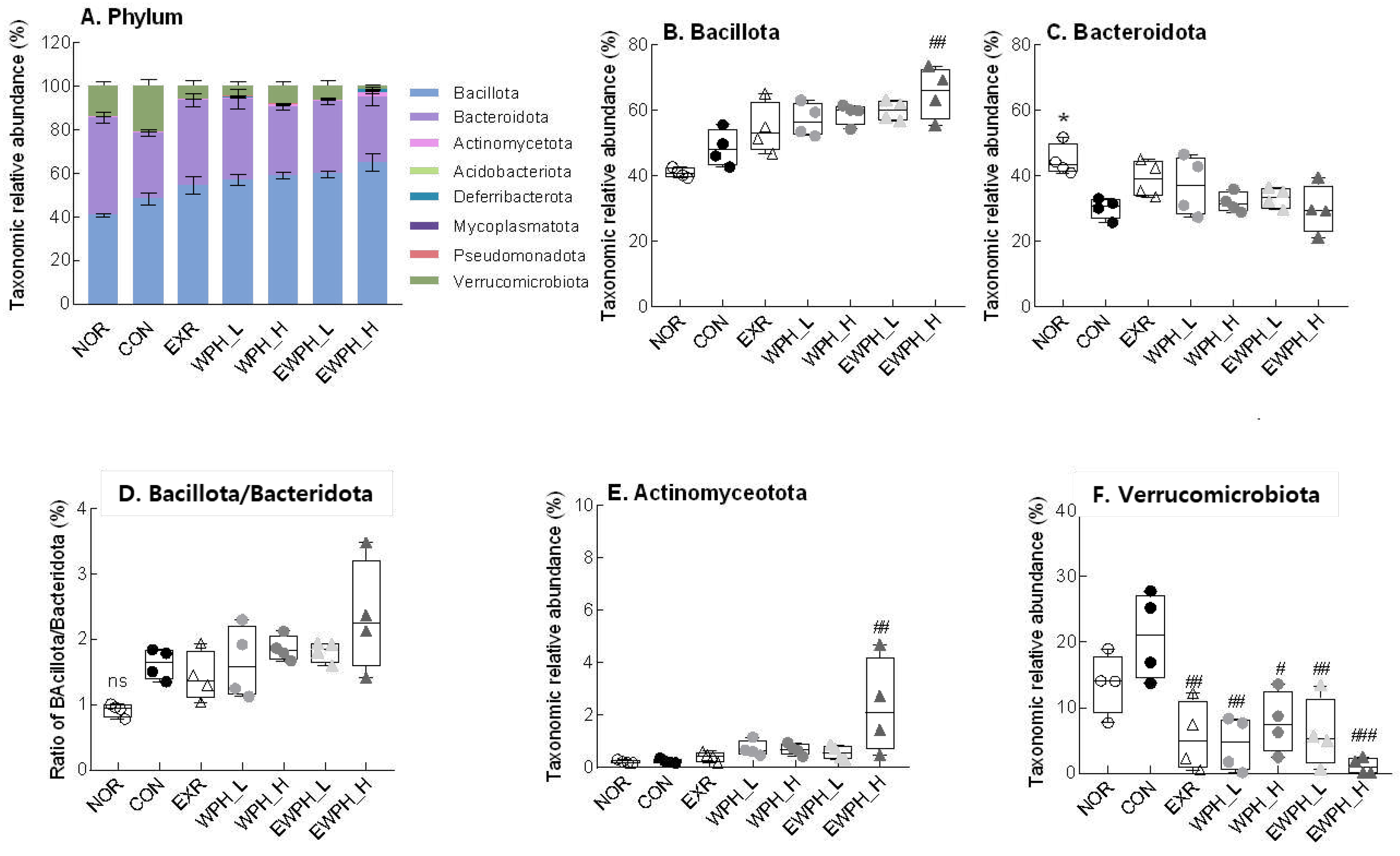

Food ingredients can enhance cognitive function by influencing the gut bacterial diversity. The gut microbiome, constituting 95% of the human microbiome, plays a vital role in the gut–brain axis [

44]. This axis links the gut microbiome to the neurological, immune, endocrine, and metabolic systems of the host, thereby playing a role in various neurological and cognitive disorders [

45].

Actinomycetes are significant contributors to these pathologies by inhibiting the activity of AChE, which breaks down ACh [

46]. We found that high doses of WPH and treadmill exercise increased the relative abundance of

Actinomycetes and reduced AChE activity. WPH administration and treadmill exercise also decreased and increased the relative abundance of

Verrucomicrobiota and

Lachnospiraceae, respectively. The relative abundance of

Lachnospiraceae has been reported to be higher in healthy populations than in patients with AD [

47].

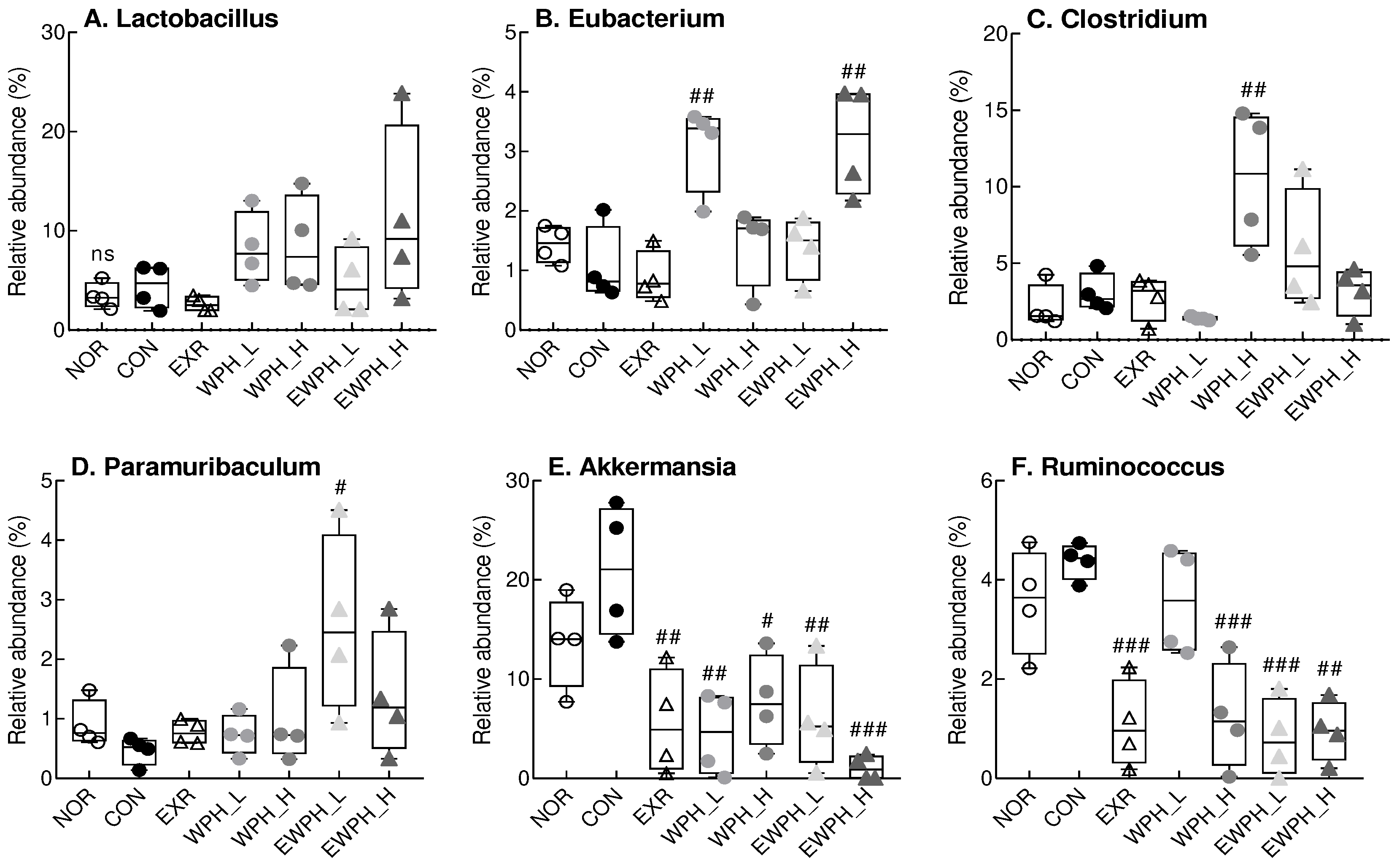

Treadmill exercise, WPH administration, and their combined treatment decreased the relative abundances of

Ruminococcus and

Akkermansia at the genus level. A decrease in

Ruminococcus abundance was also observed in the normal group during a clinical trial investigating the interaction between cognitive function and the gut flora, whereas an increase in

Ruminococcus gnavus relative abundance was reported in a scopolamine-treated model of cognitive dysfunction [

48]. These results suggest that cognitive dysfunction may be ameliorated through interactions with other microbes.

Changes in the relative abundance of

Akkermansia, a bacterial genus belonging to the phylum

Verrucomicrobiota, were similar to those of

Verrucomicrobiota detected at the phylum level.

Akkermansia was previously shown to ameliorate impaired glucose, fat metabolism, and intestinal epithelial cell damage in AD models [

49]. However, an excessive increase in

Akkermansia muciniphila did not effectively enhance memory in cognitively impaired mice. The relative abundance of

Clostridium tended to increase in all groups in this study, except for the WPH_L group, and the relative abundance increased with higher concentrations of WPH administered. An increase in

Clostridium was associated with enhanced synthesis of 3-indolepropionic acid, which scavenges free radicals, reduces neuronal cell death, and alters blood–brain barrier permeability to improve cognitive function [

50]. These results suggest that treadmill exercise and WPH improve cognitive function by modulating the gut microbiota associated with cognitive function.

Figure 1.

Effect of WPH and treadmill exercise on cognitive behaviors in mice in the Y-maze and novel object recognition test. NOR, normal; CON, control; EXR, exercise; WPH-L/H, low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; EWPH_L/H, exercise + low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. NOR group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CON group; ns, not significant (p > 0.05) (analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test).

Figure 1.

Effect of WPH and treadmill exercise on cognitive behaviors in mice in the Y-maze and novel object recognition test. NOR, normal; CON, control; EXR, exercise; WPH-L/H, low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; EWPH_L/H, exercise + low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. NOR group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CON group; ns, not significant (p > 0.05) (analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test).

Figure 2.

Effect of WPH and treadmill exercise on reactive oxygen species (ROS) and malondialdehyde (MDA) production. NOR, normal; CON, control; EXR, exercise; WPH-L/H, low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; EWPH_L/H, exercise + low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate. The levels of ROS (A) and MDA (B) were determined using DCFH-DA and TBRARS assays, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. NOR group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CON group (analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test).

Figure 2.

Effect of WPH and treadmill exercise on reactive oxygen species (ROS) and malondialdehyde (MDA) production. NOR, normal; CON, control; EXR, exercise; WPH-L/H, low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; EWPH_L/H, exercise + low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate. The levels of ROS (A) and MDA (B) were determined using DCFH-DA and TBRARS assays, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. NOR group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CON group (analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test).

Figure 3.

Effect of WPH and treadmill exercise on ACh, AChE, and ChAT. NOR, normal; CON, control; EXR, exercise; WPH-L/H, low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; EWPH_L/H, exercise + low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; ACh, acetylcholine; AChE, acetylcholine esterase; ChAT, choline acetyltransferase. The ACh content in the brain was measured using a colorimetric assay at 540 nm (A). AChE activity was examined using a specific assay kit (B). ChAT protein levels from the brain were determined using western blot (C) and quantified by ImageJ (D). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. NOR group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CON group (analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test).

Figure 3.

Effect of WPH and treadmill exercise on ACh, AChE, and ChAT. NOR, normal; CON, control; EXR, exercise; WPH-L/H, low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; EWPH_L/H, exercise + low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; ACh, acetylcholine; AChE, acetylcholine esterase; ChAT, choline acetyltransferase. The ACh content in the brain was measured using a colorimetric assay at 540 nm (A). AChE activity was examined using a specific assay kit (B). ChAT protein levels from the brain were determined using western blot (C) and quantified by ImageJ (D). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. NOR group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CON group (analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test).

Figure 4.

Effect of WPH and treadmill exercise on the relative protein ratios of Bax/Bcl-2, BDNF, and p-tau/tau. NOR, normal; CON, control; EXR, exercise; WPH-L/H, low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; EWPH_L/H, exercise + low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate. Bax, Bcl-2, BDNF, and p-tau, and tau protein levels were determined using western blot (A), and the Bax/Bcl2 (B), BDNF (C), and p-tau/tau (C) ratios were measured by ImageJ. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. NOR group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CON group (analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test).

Figure 4.

Effect of WPH and treadmill exercise on the relative protein ratios of Bax/Bcl-2, BDNF, and p-tau/tau. NOR, normal; CON, control; EXR, exercise; WPH-L/H, low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; EWPH_L/H, exercise + low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate. Bax, Bcl-2, BDNF, and p-tau, and tau protein levels were determined using western blot (A), and the Bax/Bcl2 (B), BDNF (C), and p-tau/tau (C) ratios were measured by ImageJ. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. NOR group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CON group (analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test).

Figure 5.

Effect of WPH and treadmill exercise on relative protein expression levels of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway. NOR, normal; CON, control; EXR, exercise; WPH-L/H, low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; EWPH_L/H, exercise + low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate. Relative protein levels of p-JNK/JNK (B), p-ERK/ERK (C), and p-p38/p38 (D) were determined using western blot. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. NOR group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CON group (analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test).

Figure 5.

Effect of WPH and treadmill exercise on relative protein expression levels of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway. NOR, normal; CON, control; EXR, exercise; WPH-L/H, low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; EWPH_L/H, exercise + low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate. Relative protein levels of p-JNK/JNK (B), p-ERK/ERK (C), and p-p38/p38 (D) were determined using western blot. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. NOR group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CON group (analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test).

Figure 6.

Effect of WPH and treadmill exercise on the gut microbiome composition at the phylum level. NOR, normal; CON, control; EXR, exercise; WPH-L/H, low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; EWPH_L/H, exercise + low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate. The gut microbiome at the phylum level was analyzed using rRNA gene sequencing. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. NOR group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CON group; ns, non-significant (p > 0.05) (analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test).

Figure 6.

Effect of WPH and treadmill exercise on the gut microbiome composition at the phylum level. NOR, normal; CON, control; EXR, exercise; WPH-L/H, low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; EWPH_L/H, exercise + low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate. The gut microbiome at the phylum level was analyzed using rRNA gene sequencing. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. NOR group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CON group; ns, non-significant (p > 0.05) (analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test).

Figure 7.

Effect of WPH and treadmill exercise on gut microbiome composition at the genus level. NOR, normal; CON, control; EXR, exercise; WPH-L/H, low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; EWPH_L/H, exercise + low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate. The gut microbiome at the genus level was analyzed using rRNA gene sequencing. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. NOR group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CON group; ns, non-significant (p > 0.05) (analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test).

Figure 7.

Effect of WPH and treadmill exercise on gut microbiome composition at the genus level. NOR, normal; CON, control; EXR, exercise; WPH-L/H, low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate; EWPH_L/H, exercise + low-dose/high-dose whey protein hydrolysate. The gut microbiome at the genus level was analyzed using rRNA gene sequencing. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. NOR group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CON group; ns, non-significant (p > 0.05) (analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test).