Submitted:

06 December 2023

Posted:

07 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

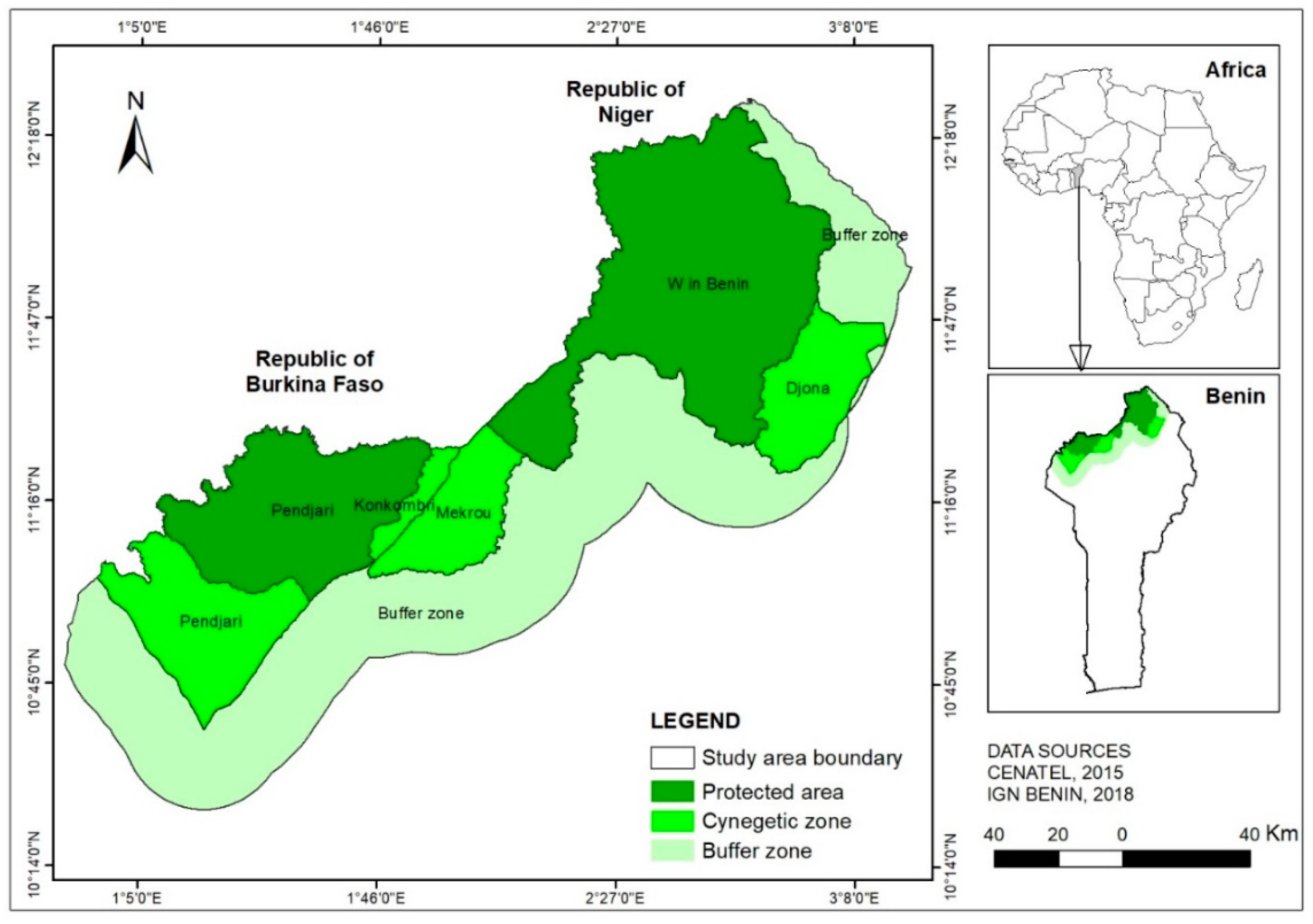

2.1. Study area

2.2. Acquisition of climatic data from 1985 to 2015

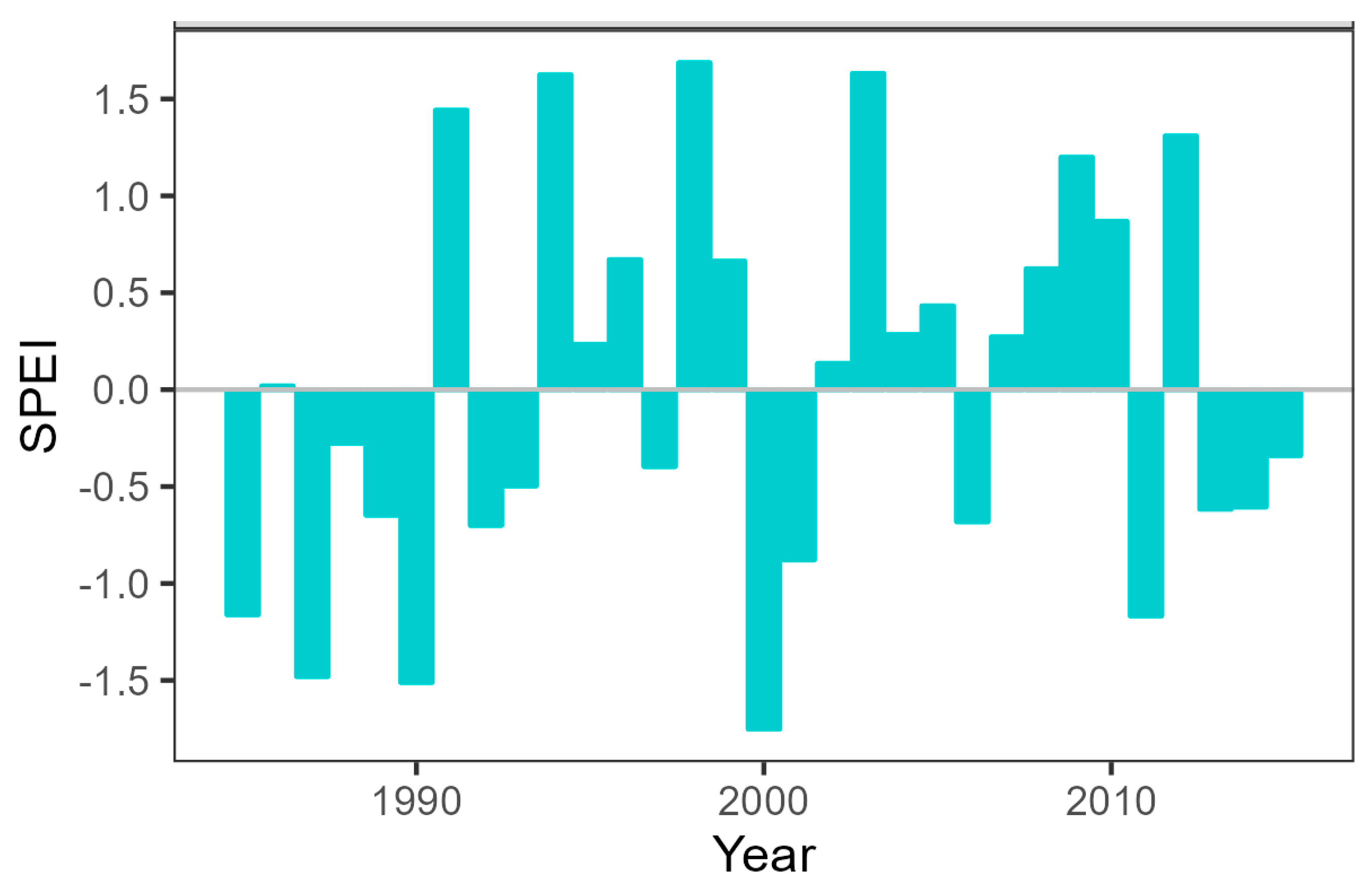

2.3. Drought frequency analysis through the application of the SPEI

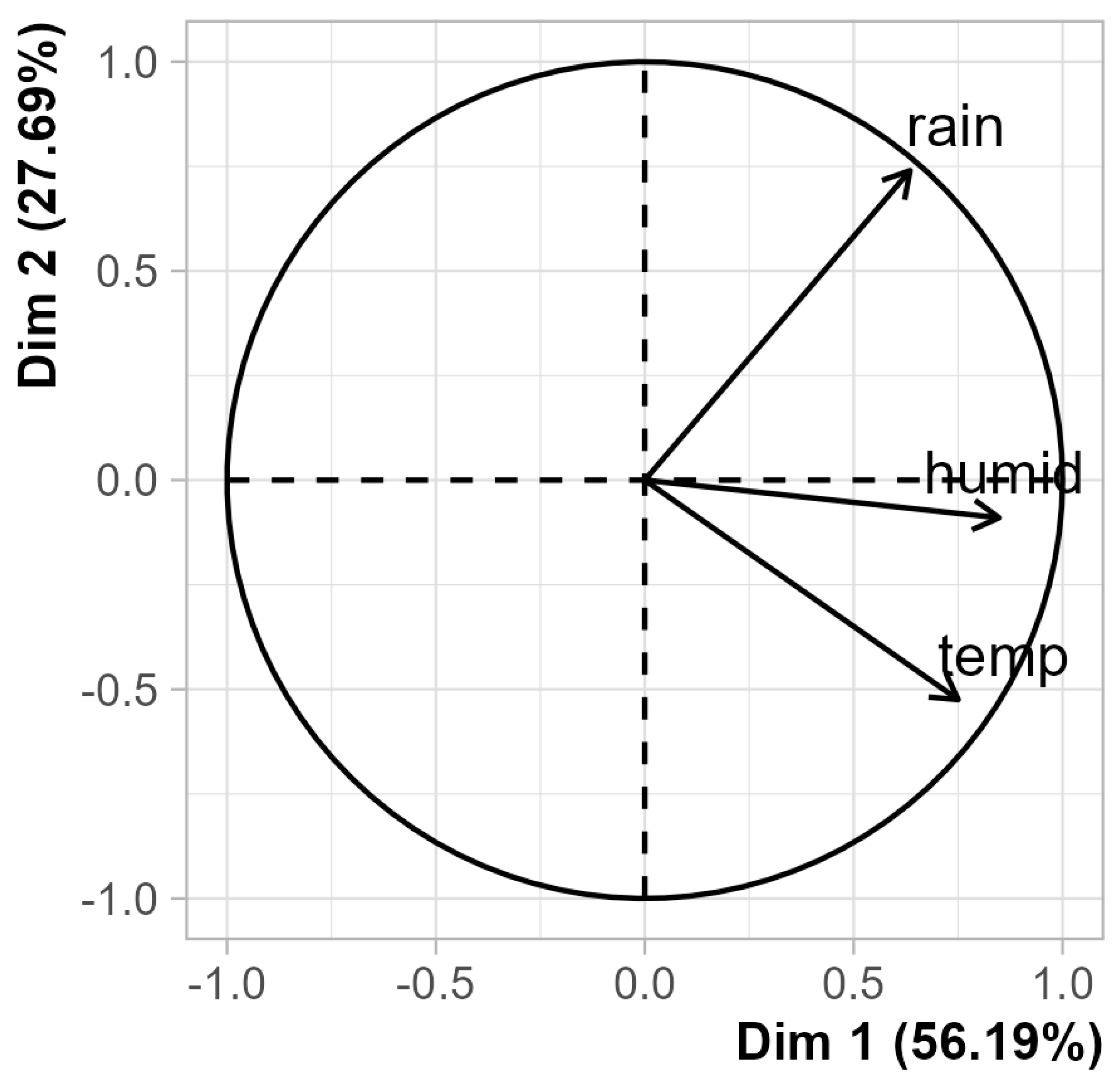

2.4. Correlation between climatic variables

| SPEI | Category |

|---|---|

| 1.83 and above | Extremely wet |

| 1.43 to 1.82 | Very wet |

| 1.0 to 1.42 | Moderately wet |

| −0.99 to 0.99 | Near Normal |

| −1.0 to −1.42 | Moderately dry |

| −1.43 to −1.82 | Severely dry |

| −1.83 and less | Extremely dry |

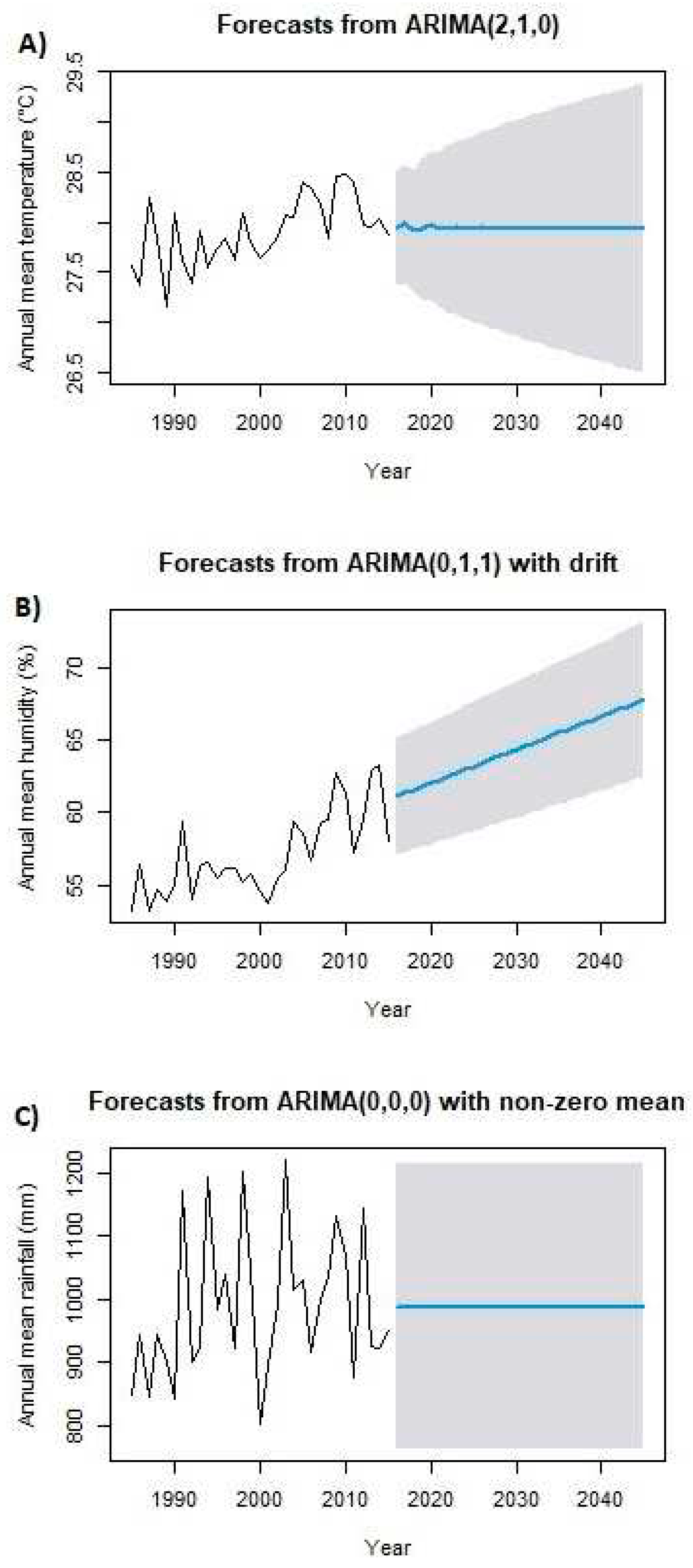

2.5. Predictive analysis of the climatic characteristics of the study for 2035

3. Results

3.1. Trends in climatic variables and drought frequency in the study area

| Temperature | Humidity | Rain | PET | BAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27.91±0.33 | 57.09±2.85 | 987.64±114.95 | 163.3±10.72 | 824.34±115.63 |

| Test statistic | n | P value | Alternative hypothesis | S | varS | tau | Sen's slop | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 3.213 | 31 | 0.001315 | two.sided | 190 | 3,461 | 0.409 | 0.02187 |

| Humidity | 4.317 | 31 | 1.581e-05 | two.sided | 255 | 3,462 | 0.5484 | 0.2222 |

| Rainfall | 1.496 | 31 | 0.1347 | two.sided | 89 | 3,462 | 0.1914 | 3.402 |

3.2. Predictive climatic characteristics in the study area for 2045

| Test statistic | df | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 0.008006 | 1 | 0.9287 |

| Humidity | 0.2378 | 1 | 0.6258 |

| Rainfall | 0.1063 | 1 | 0.7444 |

4. Discussion and implications for the conservation of the W and Pendjari Biosphere Reserves

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kowero, G.; Getting REDD right for Africa. Science and Development Network (SciDev.Net). Available online: https://www.scidev.net/global/opinions/getting-redd-right-for-africa/ (accessed on 1st September 2023).

- Osseni, A.A.; Dossou-Yovo, H.O.; Gbesso, G.H.F.; Lougbegnon, T.O. Sinsin, B. Spatial Dynamics and Predictive Analysis of Vegetation Cover in the Ouémé River Delta in Benin (West Africa). Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingbo, A.; Teka, O.; Aoudji, A.K.N.; Ahohuendo, B.; Ganglo, J.C. Climate Change in Southeast Benin and Its Influences on the Spatio-Temporal Dynamic of Forests, Benin, West Africa. Forests 2022, 13, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/species-and-climate-change (accessed on 1st September 2023).

- Sieck, M.; Ibisch, P.L.; Moloney, K.A.; Jeltsch, F. Current models broadly neglect specific needs of biodiversity conservation in protected areas under climate change. BMC Ecol. 2011, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bougouma, K.; Jaquet, S.; Bonometti, P.; Derenoncourt, E.; Schiek, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Ghosh, A.; Achicanoy, A.; Esquivel, A.; Saavedra, C.; Ramirez-Villegas, J.; Mayzelle, M.; Savelli, A.; Grosjean, G. PAM Initiative Interne Primordiale: Analyse de la Réponse pour l’Adaptation Climatique Haiti. L’Alliance de Bioversity International et le Centre International de l’Agriculture Tropicale; Programme Alimentaire Mondial, 2021.

- Dossou-Yovo, H.O.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Sinsin, B. The Contribution of Termitaria to Plant Species Conservation in the Pendjari Biosphere Reserve in Benin. Environ. Ecol. Res. 2016, 4, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kpérou Gado, B.O.; Toko, I.I.; Arouna, O.; Oumorou, M. Caractérisation des parcours de transhumance à la périphérie de la réserve de biosphère transfrontalière du W au Bénin. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2020, 14, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osseni, A.A.; Dossou-Yovo, H.O.; Hegbe, A.D.M.T.; Khan, M.N.; Sinsin, B. Assessing and modeling the vegetation cover in the W and Pendjari National parks and their peripheries using Landsat imagery and climatic data in Benin, West Africa. Faculty of Agronomic Sciences, Laboratory of Applied Ecology, University of Abomey-Calavi, Godomey, Benin. 2023, manuscript under review in Diversity Mdpi).

- Janssens, I.; de Bisthoven, L.J.; Rochette, A.J.; Kakaï, R.G.; Akpona, J.D.T.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F.; Hugé, J. Conservation conflict following a management shift in Pendjari National Park (Benin). Biol. Conserv. 2022, 272, 109598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerpa Reyes, L.J.; Ávila Rangel, H.; Herazo, L.C.S. Adjustment of the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) for the Evaluation of Drought in the Arroyo Pechelín Basin, Colombia, under Zero Monthly Precipitation Conditions. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsesmelis, D.E.; Leveidioti, I.; Karavitis, C.A.; Kalogeropoulos, K.; Vasilakou, C.G.; Tsatsaris, A.; Zervas, E. Spatiotemporal Application of the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) in the Eastern Mediterranean. Climate 2023, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, N.; Liang, B.; Wang, Z.; Cressey, E.L. Spatial and Temporal Variation, Simulation and Prediction of Land Use in Ecological Conservation Area of Western Beijing. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I.A. Multiscalar Drought Index Sensitive to Global Warming: The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrac, M.; Thao, S.; Yiou, P. Changes in temperature–precipitation correlations over Europe: are climate models reliable? Clim. Dyn. 2023, 60, 2713–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA Climate.gov. Climate Models. Available online: http://www.climate.gov/maps-data/climate-data-primer/predicting-climate/climate-models (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Houessou, L. G. Etude Sur La Caractérisation de l’occupation Des Terres et La Réalisation d’une Base de Données Sur Leur Usage Par Les Populations Riveraines Dans La Périphérie Des Réserves de Biosphère Du W et Pendjari Au Bénin; Rapport d’étude; GIZ Bénin, 2019.

- Faure, P. Notice Explicative de La Carte Pédologique de Reconnaissance de La R.P. Bénin. Feuille de Tanguiéta; ORSTOM: Paris, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Tehou, C.A.; Lougbegnon, T.O.; Houessou, L.G.; Mensanh, G.A.; Sinsin, B. Influence de la proximité des points d’eau sur l’intensité des dégâts des populations d’éléphants et sur les peuplements de Adansonia digitata L. et Acacia sieberiana DC. dans la Réserve de Biosphère de la Pendjari. Int. j. biol. chem. sci. 2019, 13, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanglè, P.C.; Yabi, J.A.; Yegbemey, N.R.; Kakai, R.G.; Sopkon, N. Rentabilité economique des systèmes de production des parcs à karité dans le contexte de l’adaptation au changement climatique du Nord-Benin. Afr. Crop Sci. J. 2012, 20, 589–602. [Google Scholar]

- Thornthwaite, C. W. An Approach toward a Rational Classification of Climate. Geogr. Rev. 1948, 38, 55–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavromatis, T. Drought index evaluation for assessing future wheat production in Greece. Int. J. Climatol. 2007, 27, 911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagge, J.H.; Tallaksen, L.M.; Xu, C.Y.; Lanen, H.A.J.V. Standardized precipitation-evapotranspiration index (SPEI): Sensitivity to potential evapotranspiration model and parameters. In Hydrology in a Changing World: Environmental and Human Dimensions, Proceedings of FRIEND-Water; Van Lanen, H.J., Demuth, S., Servat, G.L.E., Mahe, G., Boyer, J-F., Paturel, J-E., Dezetter, A., Ruelland, D., Eds.; The International Association of Hydrological Sciences: Oxfordshir, UK, 2014; pp. 367–373. [Google Scholar]

- Beguería, S.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M. SPEI: Calculation of the Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index, 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/SPEI/index.html. (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Danandeh Mehr, A.; Sorman, A.U.; Kahya, E.; Hesami Afshar, M. Climate change impacts on meteorological drought using SPI and SPEI: case study of Ankara, Turkey. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2020, 65, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing; 2022. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Braunisch, V.; Coppes, J.; Arlettaz, R.; Suchant, R.; Schmid, H.; Bollmann, K. Selecting from correlated climate variables: a major source of uncertainty for predicting species distributions under climate change. Ecography 2013, 36, 971–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, C.F.; Elith, J.; Bacher, S.; Buchmann, C.; Carl, G.; Carré, G.; Marquéz, J.R.G.; Gruber, B.; Lafourcade, B.; Leitão, P.I.; Münkemüller, T.; McClean, C.; Osborne, P.E.; Reineking, B.; Schröder, B.; Skidmore, A.K.; Zurell, D.; Sven Lautenbach, S. Collinearity: a review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography 2013, 36, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dramani, R.; Gouwakinnou, G.N.; Houdanon, R.D.; De Kesel, A.; Minter, D.; Yorou, N.S. Ecological niche modelling of Cantharellus species in Benin, and revision of their conservation status. Fungal Ecol. 2022, 60, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rstudio Core Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. RStudio, 2022. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Praveen, B.; Talukdar, S.; Shahfahad, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Mahato, S.; Mondal, J.; Sharma, P.; Islam, A.R.M.T.; Rahman, A. Analyzing trend and forecasting of rainfall changes in India using non-parametrical and machine learning approaches. Sci. Rep. 2020; 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Hooyberghs, H.; Lauwaet, D.; De Ridder, K. Urban Heat Island and Future Climate Change-Implications for Delhi’s Heat. J Urban Health 2019, 96, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Hashino, M. Long Term Trends of Annual and Monthly Precipitation in Japan1. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2003, 39, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Wang, C.Y. Applicability of prewhitening to eliminate the influence of serial correlation on the Mann-Kendall test. Water Resour. Res. 2002, 38, 4–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlert, T. Trend: Non-Parametric Trend Tests and Change-Point Detection, 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/trend/index.html (accessed on 2023-06-19).

- Sen, P. K. Estimates of the Regression Coefficient Based on Kendall’s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 63, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buma, W.G.; Lee, S.-I.; Seo, J.Y. Hydrological Evaluation of Lake Chad Basin Using Space Borne and Hydrological Model Observations. Water 2016, 8, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, M.S.; Babel, M.S.; Sharif, M. Hydro-meteorological trends in the upper Indus River basin in Pakistan. Clim. Res. 2011, 46, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Merwade, V.; Kam, J.; Thurner, K. Streamflow trends in Indiana: Effects of long term persistence, precipitation and subsurface drains. J. Hydrol. 2009, 374, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MCVDD-BENIN. Plan National d’adaptation Aux Changements Climatiques (PNA); Ministère du Cadre de Vie et de Développement Durable. Direction Générale de l’Environnement et du Climat (DGEC): Bénin, 2022.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture and Food Supply. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/climateimpacts/climate-change-impacts-agriculture-and-food-supply. (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- B Bauer, H.; Chardonnet, B.; Scholte, P.; Kamgang, S.A.; Tiomoko, D.A.; Tehou, A.C.; Sinsin, B.; Gebresenbet, F.; Asefa, A.; Bobo, K.S.; Garba, H.; Abagana, A.L.; Diouck, D.; Mohammed, A.A.; Sillero-Zubiri, C. Consider divergent regional perspectives to enhance wildlife conservation across Africa. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sylla, M.B.; Nikiema, P.M.; Gibba, P.; Kebe, I.; Klutse, N.A.B. Climate Change over West Africa: Recent Trends and Future Projections. In Adaptation to Climate Change and Variability in Rural West Africa; Yaro, J. A., Hesselberg, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, R.G.J.; Parker, D.J.; Marsham, J.H.; Rowell, D.P.; Jackson, L.S.; Finney, D.; Deva, C.; Tucker, S.; Stratton, R. How a typical West African day in the future-climate compares with current-climate conditions in a convection-permitting and parameterised convection climate model. Clim. Change 2020, 163, 267–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yang, C.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J. Spatiotemporal drought analysis by the standardized precipitation index (SPI) and standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) in Sichuan Province, China. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, D.; Babel, M.S.; Shrestha, S.; Virdis, S.G.P.; Collins, M. Multivariate and multi-temporal analysis of meteorological drought in the northeast of Thailand. Weather and Climate Extremes 2021, 34, 100399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, M.; Khan, A.; Fatima, K.; Ajaz, O.; Ali, S.; Main, K. Analysis of Temperature Variability, Trends and Prediction in the Karachi Region of Pakistan Using ARIMA Models. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, E.; Morley, P.J.; Jump, A.S.; Donoghue, D.N.M. Satellite data track spatial and temporal declines in European beech forest canopy characteristics associated with intense drought events in the Rhön Biosphere Reserve, central Germany. Plant Biology 2022, 24, 1120–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).