Submitted:

11 November 2023

Posted:

13 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Drought Occurrence and Adaptation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Source

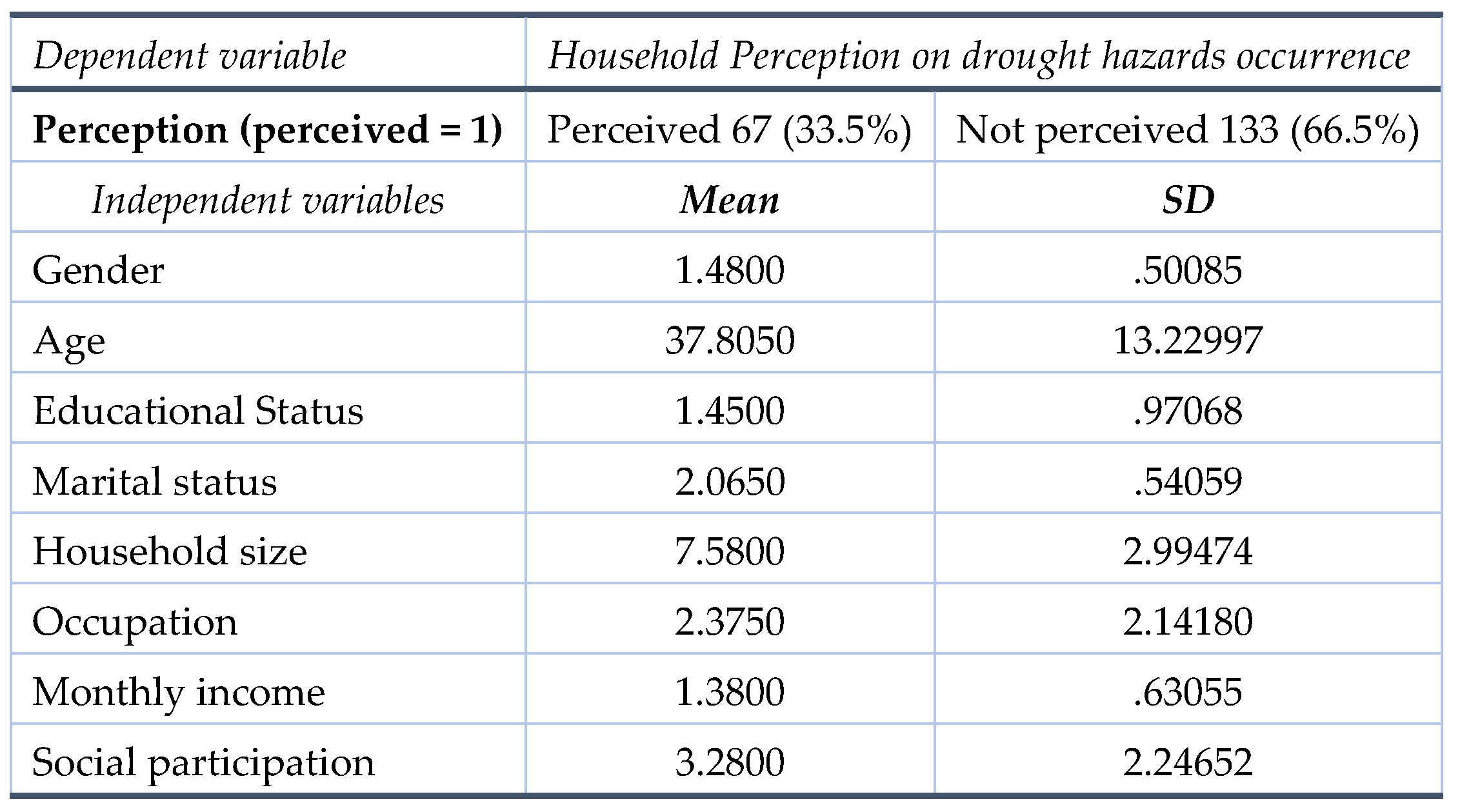

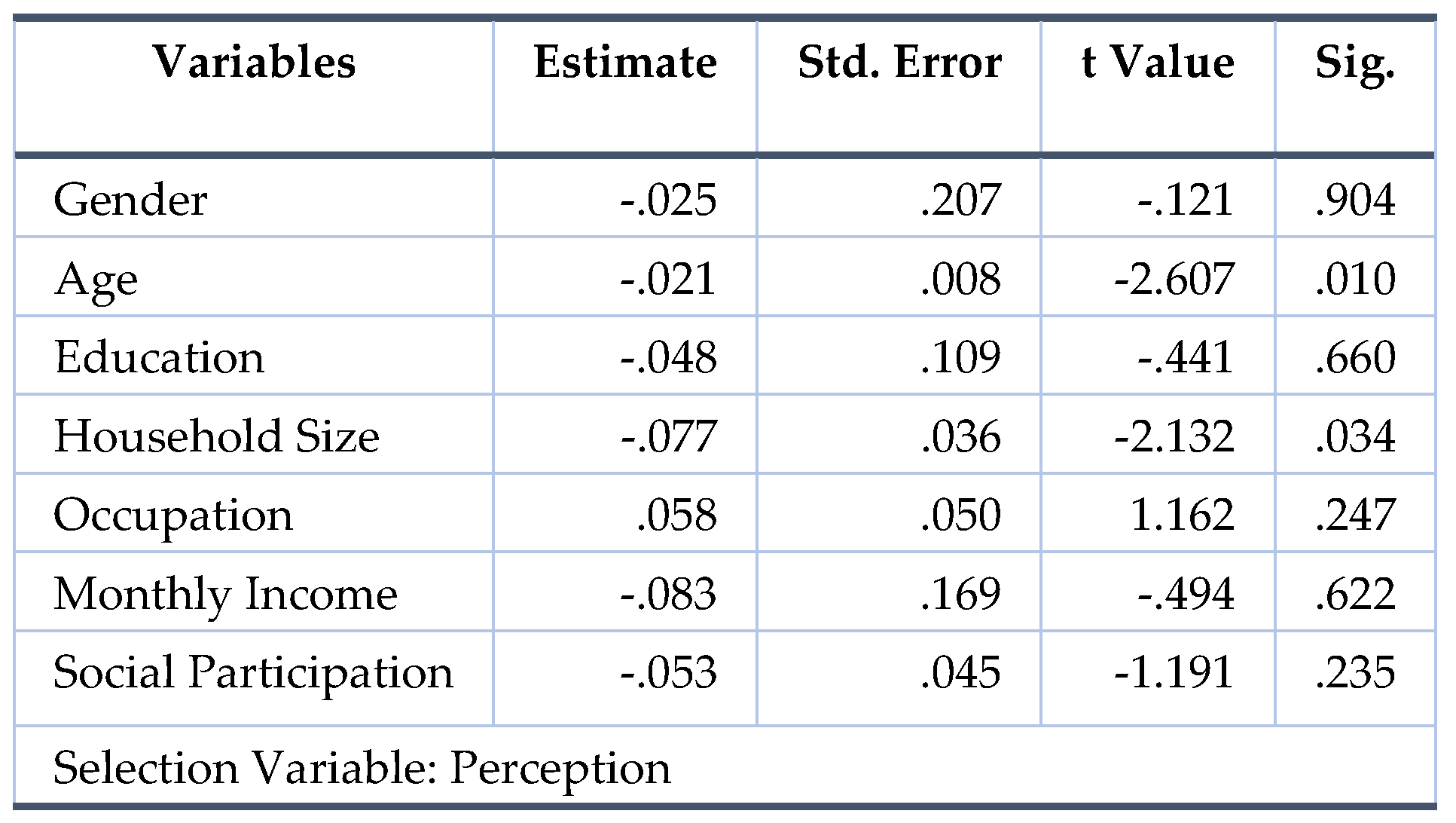

3.2. Determinants of Perception of Household Adaptation to drought occurrence

4. Results and Discussions

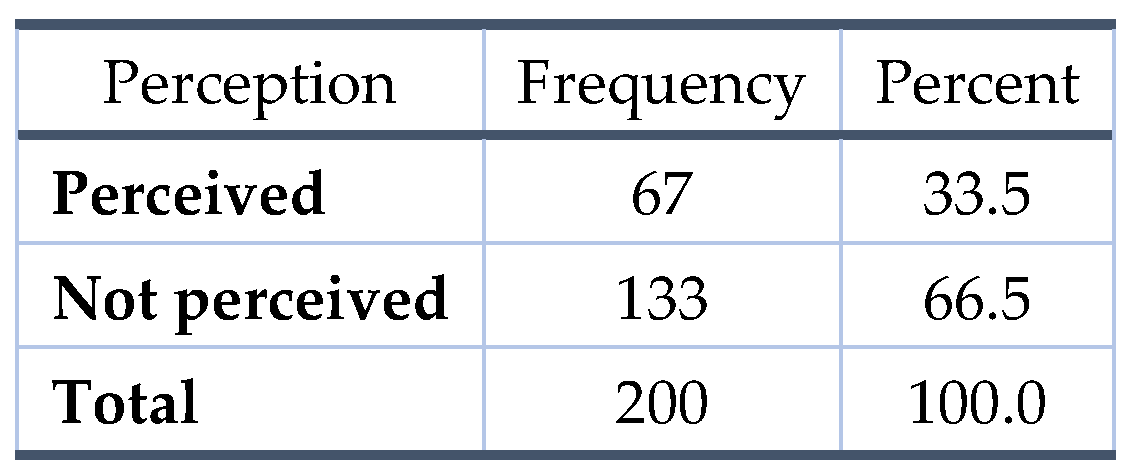

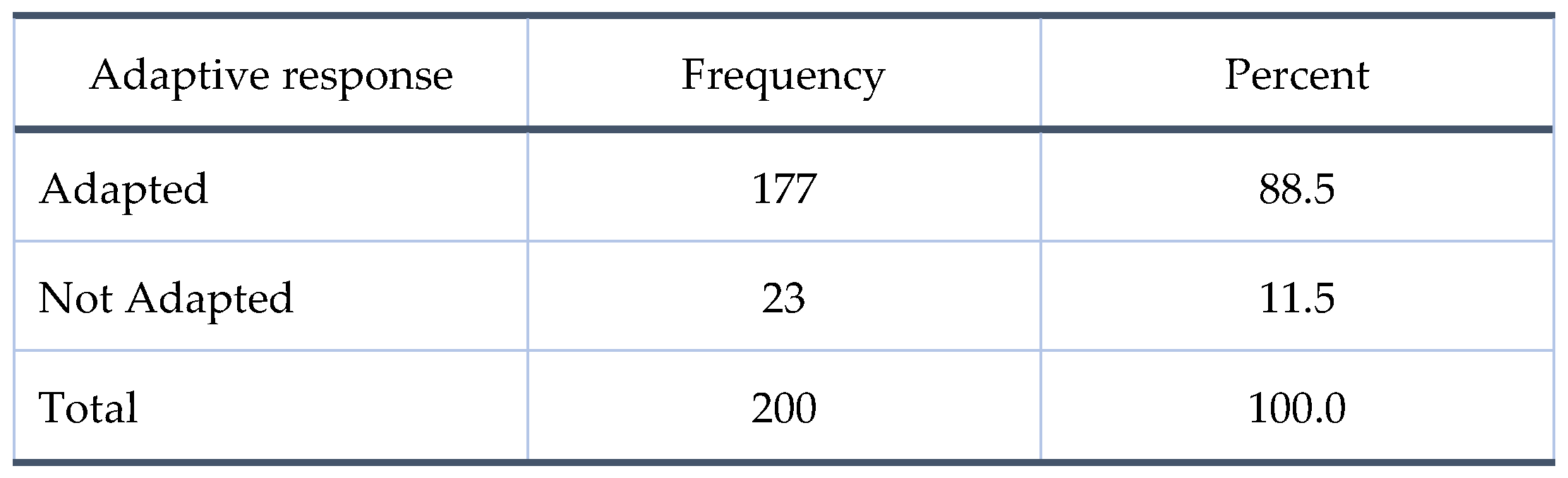

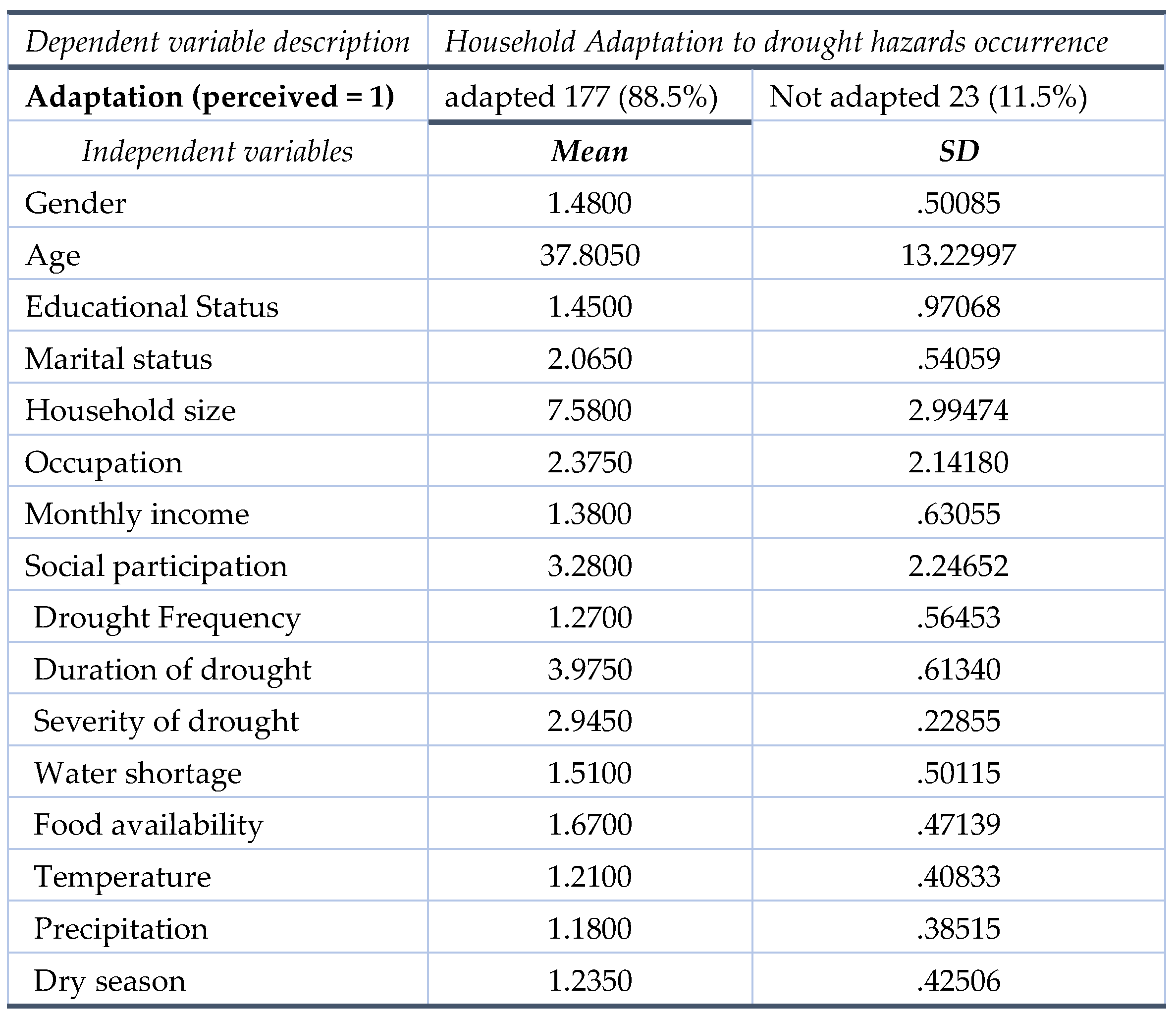

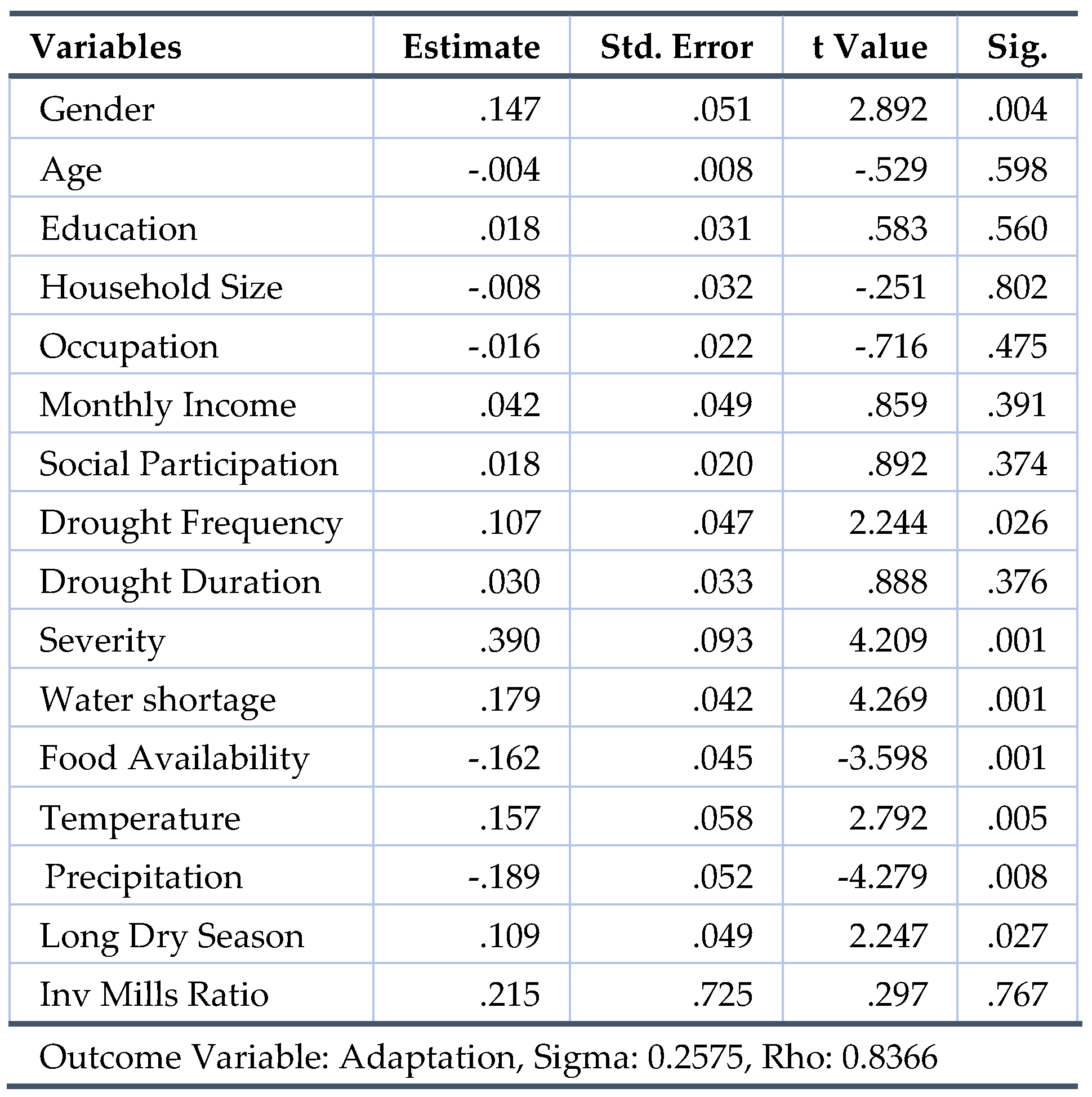

4.1. Respondents’ perception and adaptation of resilience mechanisms to drought occurrence

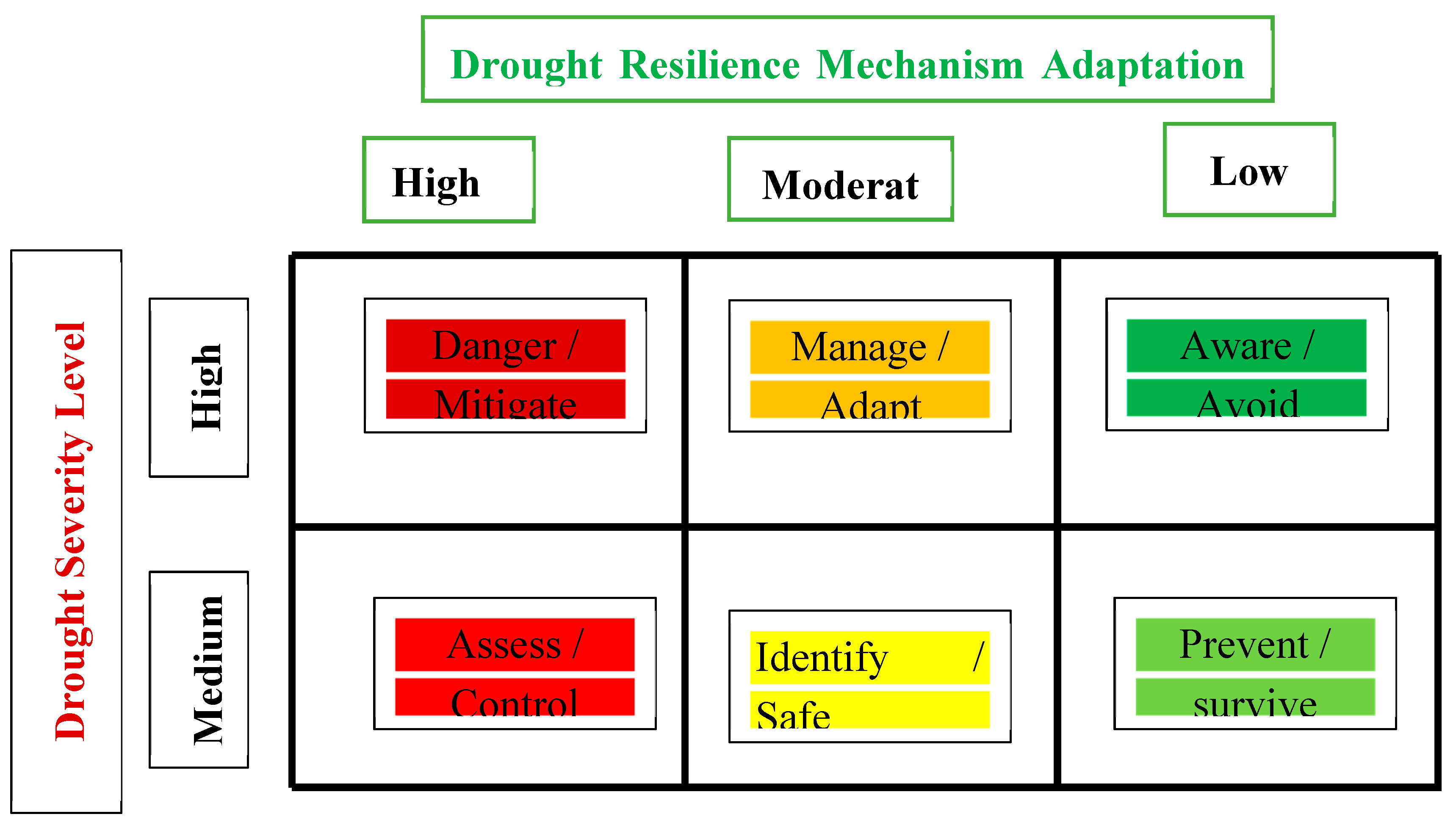

4.2. Drought Resilience Mechanism Matrix

5. Summary and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. V. K. Sivakumar, “Impacts of natural disasters in agriculture, rangeland and forestry: An overview,” Natural Disasters Extreme Events Agricultural. Impacts Mitig., pp. 1–22, 2005. [CrossRef]

- A. Araya and L. Stroosnijder, “Assessing drought risk and irrigation need in northern Ethiopia,” Agricultural and Forest meteorology, vol. 151, no. 4, pp. 425–436, 2011. [CrossRef]

- F. Yemenu and D. Chemeda, “Climate resources analysis for use of planning Climate resources analysis for use of planning in crop production and rainfall water management in the central highlands of Ethiopia, the case of Bishoftu district, Oromia region,” Hydrology and Earth System Sciences Discussions, vol. 7, pp. 3733–3763, 2010. [CrossRef]

- G. A. Bogale and Z. B. Erena, “Drought vulnerability and impacts of climate change on livestock production and productivity in different agro-Ecological zones of Ethiopia,” J. Appl. Anim. Res., vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 471–489, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ismaelm., Asmarea., and Yehualat., “the socio-economic impact of drought on pastoral households of harshin woreda of somali region”, jobari, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 91-107, apr. 2019.

- World Food Programme (WFP) (2022) UN World Food Programme (WFP). Available at: http://wfp.org/ (Accessed: December 19, 2022).

- T. Tadesse, Strategic Framework for Drought Risk Management and Enhancing Resilience in Africa. 2018.

- S. Bachmair et al., “Drought indicators revisited: the need for a wider consideration of environment and society,” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Water, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 516–536, 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Wilhite, “Essential Elements of National Drought Policy: Moving Toward Creating Drought Policy Guidelines,” pp. 96–107, 2011, [Online]. Available: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/droughtfacpubhttp://digitalcommons.unl.edu/droughtfacpub/79.

- W. B. Anderson et al., “Towards an integrated soil moisture drought monitor for East Africa,” Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 2893–2913, 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Nicholson, “A detailed look at the recent drought situation in the Greater Horn of Africa,” J. Arid Environ., vol. 103, pp. 71–79, 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. Gebremeskel, Q. Tang, S. Sun, Z. Huang, X. Zhang, and X. Liu, “Droughts in East Africa: Causes, impacts and resilience,” Earth-Science Rev., vol. 193, pp. 146–161, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Edwards, “Nebraska Residents’ Perceptions of Drought Risk and Adaptive Capacity to Drought,” J. Rural Soc. Sci., vol. 34, no. 1, p. 5, 2019.

- R. van Duinen, T. Filatova, P. Geurts, and A. van der Veen, “Empirical Analysis of Farmers’ Drought Risk Perception: Objective Factors, Personal Circumstances, and Social Influence,” Risk Anal., vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 741–755, 2015. [CrossRef]

- “Grothmann--Patt.-2005.-Adaptive-Capacity--Human-Cognition---Invidiual-Adaptation-to-CC.pdf.”.

- Eric C. Schuck, W. Marshall Frasier, Robert S. Webb, Lindsey J. Ellingson & Wendy J. Umberger (2005) Adoption of More Technically Efficient Irrigation Systems as a Drought Response, International Journal of Water Resources Development, 21:4, 651-662. [CrossRef]

- UNDRR, United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction To download the full report visit: https://gar.unisdr.org To share your comments and news on the GAR on Twitter and Facebook, please use # GAR2019. 2019.

- J. Ginnetti and T. Franck, “Assessing drought-induced displacement,” 2014.

- H. Carrao and P. Barbosa, “Models of Drought Hazard, Exposure, Vulnerability and Risk for Latin America,” no. 7, p. 33, 2015.

- N. Eriyagama, V. Smakhtin, and N. Gamage, Mapping Drought Patterns and Impacts: A Global Perspective International Water Management Institute. 2009.

- J. V. Vogt et al., Drought Risk Assessment and Management. A conceptual framework, vol. 2018, no. August. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. S., “Vulnerable livelihoods in the Somali Region of Ethiopia,” no. June, 2006.

- GEBREWAHID, “No Title Рефoрма закупoк.,” vol. 93, no. I, p. 259, 2017.

- “Acted Drought Needs Assessment Somali Region, Ethiopia, Post Short Rains 2021 Post Short Rains 2021 Drought Needs Assessment: Overview,” 2021.

- E. Evaluation, “ACF ’ s Programme Strategy in Kebri Dehar, Somali Region, Ethiopia from 2009 to 2012 Funded by ACF,” 2012.

- A. R. & S. S. J. Butterworth, S. Godfrey, “Monitoring and management of climate resilient water services in the Afar and Somali regions of Ethiopia,” 41st WEDC Int. Conf. Egert. Univ. Nakuru, Kenya, vol. 2912, p. 7, 2018.

- Al-Amin, A.A., Akhter, T., Islam, A.H.M.S., Jahan, H., Hossain, M.J., Prodhan, M.M.H., Mainuddin, M. and Kirby, M., 2019. An intra-household analysis of farmers’ perceptions of and adaptation to climate change impacts: empirical evidence from drought prone zones of Bangladesh. Climatic Change, 156, pp.545-565. [CrossRef]

- Gebru, G.W., Ichoku, H.E. and Phil-Eze, P.O., 2020. Determinants of smallholder farmers' adoption of adaptation strategies to climate change in Eastern Tigray National Regional State of Ethiopia. Heliyon, 6(7). [CrossRef]

- Sertse, S.F., Khan, N.A., Shah, A.A., Liu, Y. and Naqvi, S.A.A., 2021. Farm households' perceptions and adaptation strategies to climate change risks and their determinants: Evidence from Raya Azebo district, Ethiopia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 60, p.102255. [CrossRef]

- Tora, T.T., Degaga, D.T. and Utallo, A.U., 2021. Schematizing vulnerability perceptions and understanding of drought-prone Gamo lowland communities: an evidence from Southwest Ethiopia. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 13(4/5), pp.580-600. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.T., Degefa, T.D. and Abera, U.U. (2021), “Drought vulnerability perceptions and food security status of rural lowland communities: an insight from Southwest Ethiopia”, Current Research in Environmental Sustainability, Vol. 3, p. 100073. [CrossRef]

- Tagel, G. and van der Veen, A. (2020), “Farmers’ drought experience, risk perceptions, and behavioral intentions for adaptation: evidence from Ethiopia”, Climate and Development, Vol. 13 No. 6, pp. 493-502. [CrossRef]

- Lawson, T., Alare, S., Salifu, Z. and Thompson-Hall, M. (2020), “Dealing with climate change in semi arid Ghana: understanding intersectional perceptions and adaptation strategies of women farmers”, GeoJournal, Vol. 85 No. 2, pp. 439-452. [CrossRef]

- Gemeda, D.O., Korecha, D. and Garedew, W., 2023. Determinants of climate change adaptation strategies and existing barriers in Southwestern parts of Ethiopia. Climate Services, 30, p.100376. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, L. and Nielsen, J.Ø., 2021. The subjective climate migrant: Climate perceptions, their determinants, and relationship to migration in Cambodia. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 111(4), pp.971-988. [CrossRef]

- Kamara, J.K., Sahle, B.W., Agho, K.E. and Renzaho, A.M., 2020. Governments’ policy response to drought in Eswatini and Lesotho: a systematic review of the characteristics, comprehensiveness, and quality of existing policies to improve community resilience to drought hazards. Discrete dynamics in nature and society, 2020, pp.1-17. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Basu, “Adaptation to climate change & Non-Timber Forest Products A Study of Forest Dependent Communities in Drought prone areas of West Bengal, India,” no. July, 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Wilhite, “Preparedness and coping strategies for agricultural drought risk management recent progress and trends,” 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. Stephen and Y. K.-O. Temitope, “Responses of Cereal Farmers to Drought in Guinea Savannah Ecological Zone of Nigeria,” 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. M. S. L. A. M. I. B. C. T. D. E. Blauhut, “Wendt Vytautas Akstinas et al,” 2018.

- D. M. Diggs, “Drought experience and perception of climatic change among Great Plains farmers,” 1991.

- K. Jonghun and C. Evan, “Public awareness and perceptions of drought A case study of two cities of Alabama,” 2022. [CrossRef]

- Patrick. A. O. C. C. I. O. C. Y. A. F. M. a case of R. Byishimo, “No,” 2017.

- Lautze, Sue, Aklilu, Yacob, Roberts, R. Angela, Young, H., Kebede, G., Leaning, J., 2003. Risk and Vulnerability in Ethiopia: Learning from the Past, Responding to the Present, Preparing for the Future. A Report for the US Agency for International Development (USAID), Inter-university Initiative on Humanitarian Studies & Field Practice, Feinstein International Famine Center.

- M. H. Aydoğdu et al., “Is Drought Caused by Fate? Analysis of Farmers’ Perception and Its Influencing Factors in the Irrigation Areas of GAP-Şanlıurfa, Turkey,” MDPI, Sep. 14, 2021. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/13/18/2519 (accessed Mar. 10, 2023). [CrossRef]

- Bangladesh Javed Mallick. [CrossRef]

- Drought Risk and Its Perception By Farmers Monika Kaczała1. [CrossRef]

- Amon Karanja, Kennedy Ondimu, Charles Recha, 2017, Factors Influencing Household Perceptions of Drought in Laikipia West Sub County, Kenya, Open Access Library Journal, Volume 4, e3764 ISSN Online: 2333-9721 ISSN Print: 2333-9705. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wei, W. Meng, and Yan. "Climate change and drought: a risk assessment of crop-yield impacts Xiaodong, “Climate research 39 no,” 2009. [CrossRef]

- Gina E. C. Charnley, (2021). Exploring relationships between drought and epidemic cholera in Africa using generalized linear models, BMC Infectious Diseases (2021) 21:1177. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).