Submitted:

10 November 2023

Posted:

13 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Notations, nomenclature, and assumptions

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.1. Nomenclature

- Vector X = (x1, x2, ⋯, xm) is considered less than or equal to vector Y = (y1, y2, ⋯ , ym), denoted as X ≤ Y, if xi ≤ yi holds for all i = 1, 2, ⋯ , m. If, in addition to X ≤ Y, there exists at least one j such that xj < yj, we express it as X < Y. For instance, if we take X = (4, 2, 1), Y = (3, 1, 1), and Z = (2, 2, 2), we can observe that Y < X, Z ≮ X, X ≮ Z, Y ≮ Z, and Z ≮ Y.

- We define a vector X ∊ Ψ as a minimal vector when there is no other Y ∊ Ψ such that Y < X. For example, every vector in the set {(4, 3, 1), (2, 1, 3), (3, 4, 1), (1, 2, 2)} is a minimal vector. It is worth noting that a vector does not need to be less than or equal to all other vectors in the set to be considered minimal

- Noting that a path is a set of adjacent arcs enabling data transmission from source node 1 to destination node n, we say path P1 is a subset of path P2, denoted by P1 ⊂ P2 when P2 encompasses all the arcs present in path P1.

2.2. Assumptions

- The capacity of each arc is a random integer ranging from 0 to for , following a predefined probability distribution function. It is important to emphasize that is a known integer value, representing the maximum capacity of arc .

- The arcs’ capacities are statistically independent.

- The network adheres to the flow conservation law, which means that no other node generates or accumulates flow apart from the source and destination nodes.

- All the required flow is sent through a solitary path from node 1 to node n.

- Each node is perfectly reliable.

3. Background

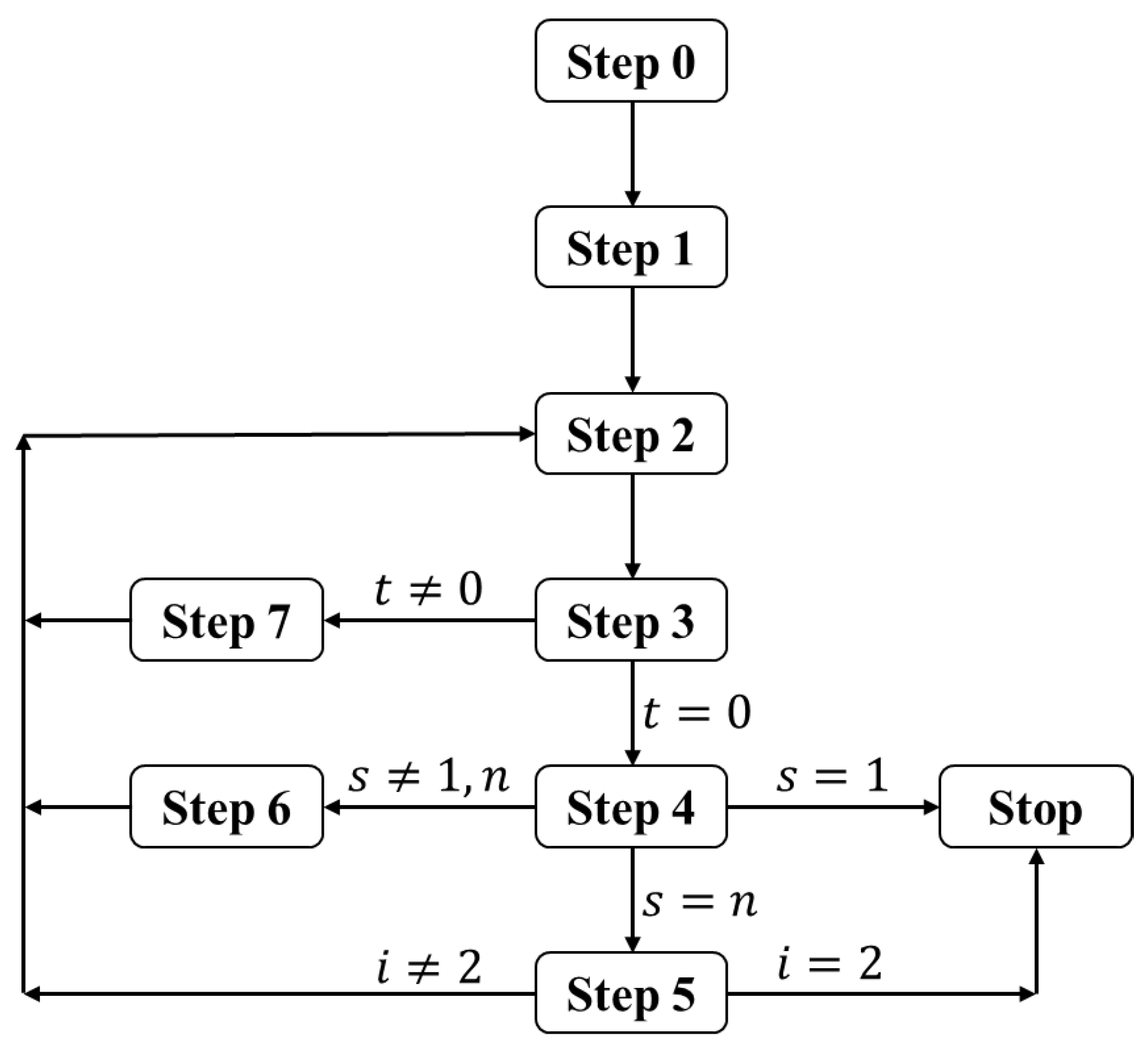

4. The NCM-based algorithm

- Input: , demand level d, budget limit b, and time limit T.

- Output: The set of all the ()-s.

5. The complexity results and an illustrative example

5.1. The complexity results

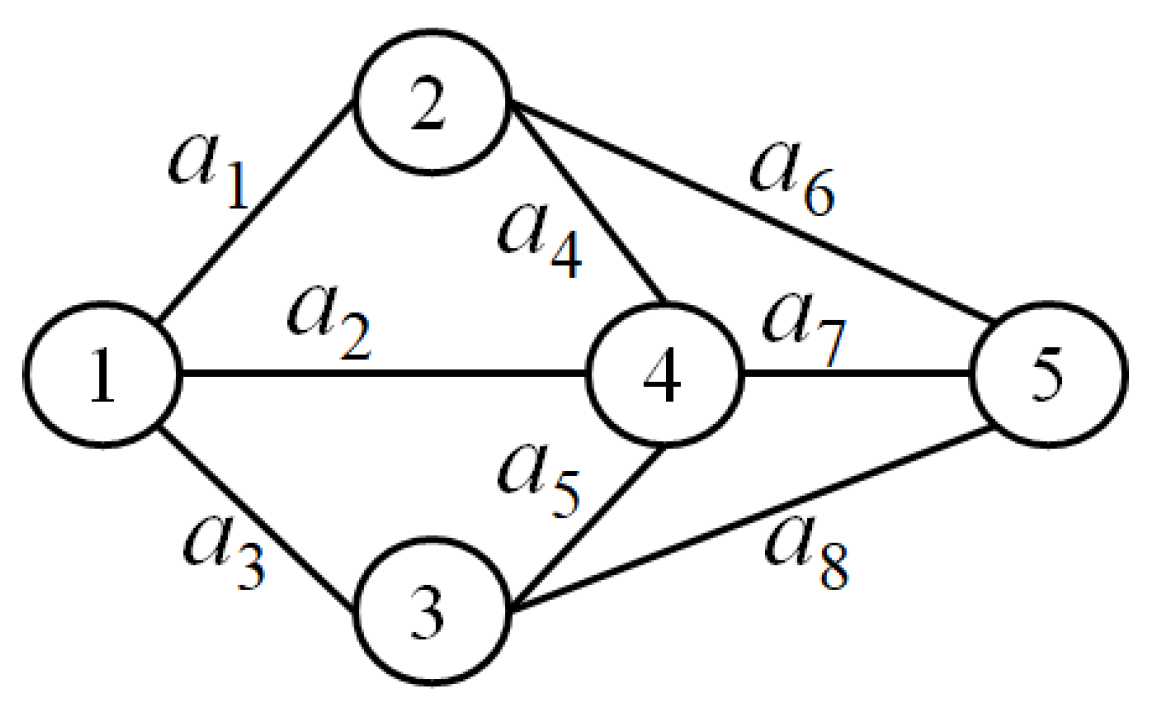

5.2. An illustrative example

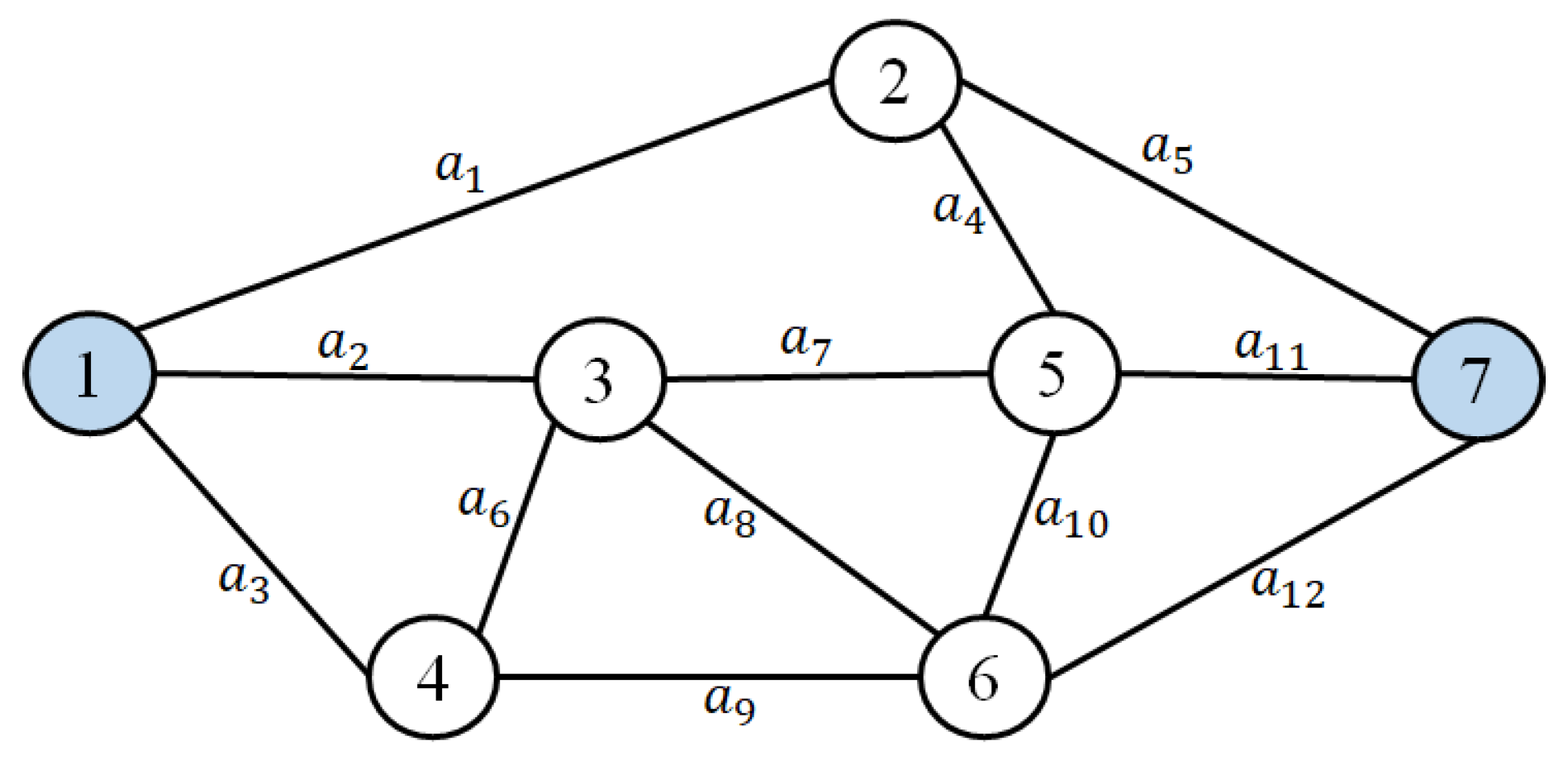

- Solution: There are nodes and arcs in the given network. We have (3, 3, 3, 3, 5, 4, 4, 5, 3, 5, 5, 4), (1, 4, 2, 3, 2, 4, 2, 3, 1, 1, 1, 3), and (8, 8, 9, 8, 7, 8, 6, 6, 7, 8, 4, 3) according to Table 2, and , , and are given.

- Step 0. We let , , , , , , and .

- Step 1. The NC matrix is equal to

- Step 2. , so we let .

- Step 3. , the transfer is made to Step 7.

- Step 7. , so . As , , and , we let , , , , , , , and go to Step 2.

- Step 2. , so we let .

- Step 3. , the transfer is made to Step 7.

- Step 7. , so . As , , and , we let , , , , , , , and go to Step 2.

- Step 2. , we let and repeat this step.

- Step 2. , so we let .

- Step 3. , the transfer is made to Step 7.

| Arcs | Lead time | Cost | Capacities/Probabilities | |||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| 1 | 8 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 8 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.94 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 9 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 8 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 0.85 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 7 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.9 | |

| 4 | 8 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.82 | 0 | |

| 2 | 6 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.74 | 0 | |

| 3 | 6 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.9 | |

| 1 | 7 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.95 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 8 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.85 | |

| 1 | 4 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.85 | |

| 3 | 3 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.84 | 0 | |

- Step 7. , so . As , we let and go to Step 2.

- Step 2. , so we let .

- Step 3. , the transfer is made to Step 7.

- The final set of solutions is obtained { (3, 0, 0, 3, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 3, 0), (2, 0, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0), (0, 0, 3, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 3, 3, 3, 0)}.

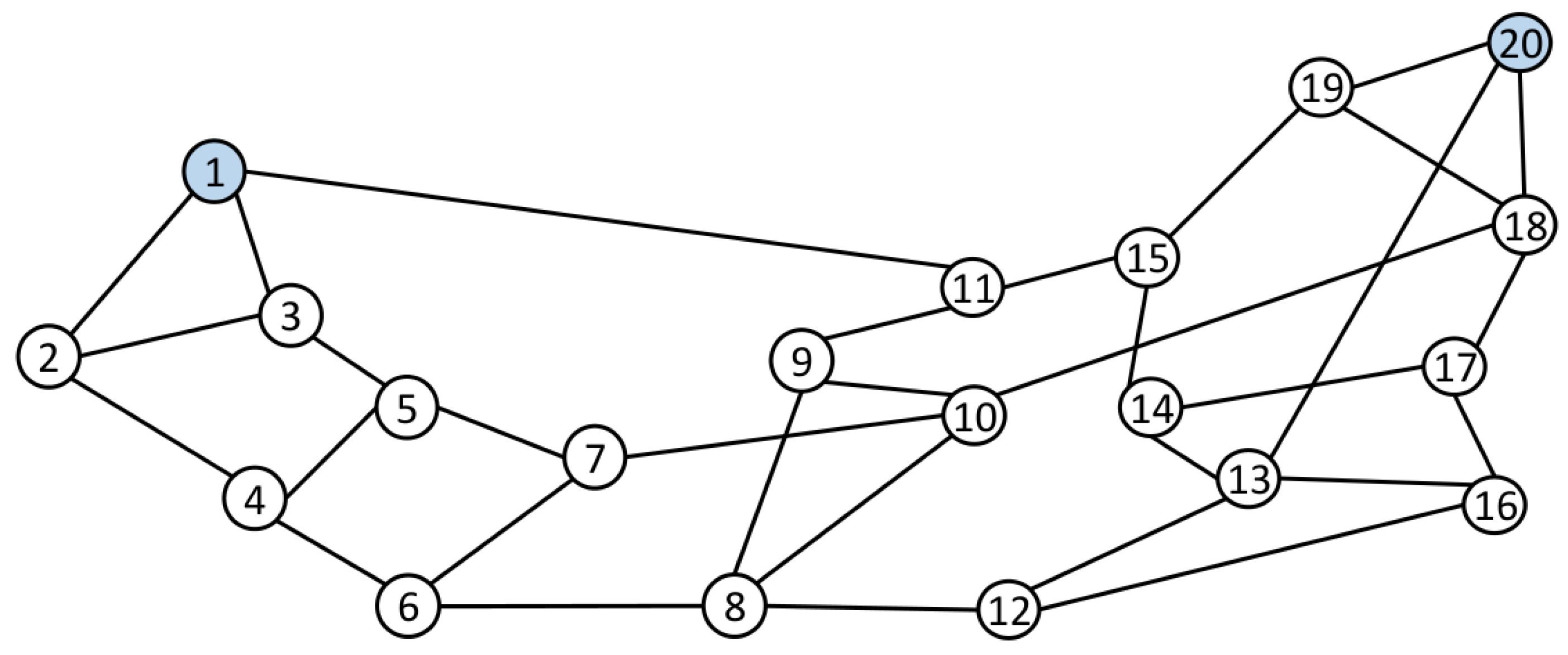

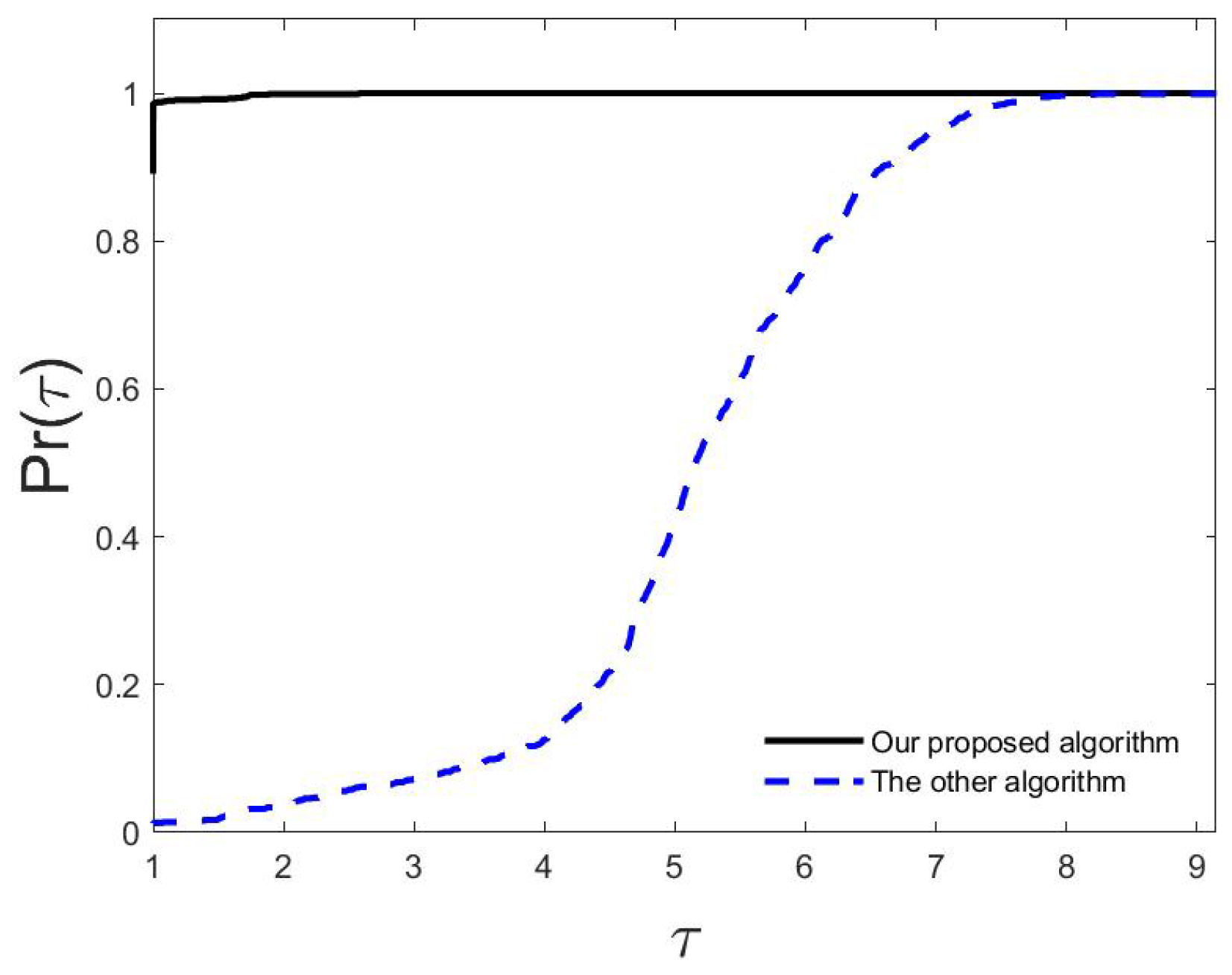

6. Experimental results

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

Abbreviations

| MFN | Multistate Flow Network |

| SSV | System State Vector |

| QPRP | Quickest Path Reliability Problem |

| MP | Minimal Path |

References

- Moore, M.H. On the fastest route for convoy-type traffic in flowrate-constrained networks. Transportation Science 1976, 10, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Chin, Y.H. The quickest path problem. Computers & Operations Research 1990, 17, 153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, B.; Khassawneh, B. On the Number of Shortest Weighted Paths in a Triangular Grid. Mathematics 2020, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forghani-elahabad, M.; Yeh, W.C. An improved algorithm for reliability evaluation of flow networks. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2022, 221, 108371. [Google Scholar]

- El Khadiri, M.; Yeh, W.C. An efficient alternative to the exact evaluation of the quickest path flow network reliability problem. Computers & Operations Research 2016, 76, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sedeño-Noda, A.; González-Barrera, J.D. Fast and fine quickest path algorithm. European Journal of Operational Research 2014, 238, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forghani-elahabad, M. A simple algorithm for reliability evaluation of stochastic-flow networks under distance limitation. Proceeding Series of the Brazilian Society of Computational and Applied Mathematics, Accepted 2023.

- Niu, Y.F.; He, C.; Fu, D.Q. Reliability assessment of a multi-state distribution network under cost and spoilage considerations. Annals of Operations Research 2021, pp. 1–20.

- Liu, H.; Song, G.; Liu, T.; Guo, B. Multitask Emergency Logistics Planning under Multimodal Transportation. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forghani-elahabad, M. An improved algorithm for the quickest path reliability problem. Proceeding Series of the Brazilian Society of Computational and Applied Mathematics 2022, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Calvete, H.I.; del Pozo, L.; Iranzo, J.A. Algorithms for the quickest path problem and the reliable quickest path problem. Computational Management Science 2012, 9, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.F.; Gao, Z.Y.; Lam, W.H. Evaluating the reliability of a stochastic distribution network in terms of minimal cuts. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2017, 100, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.F.; Wei, J.H.; Xu, X.Z. Computing the Reliability of a Multistate Flow Network with Flow Loss Effect. IEEE Transactions on Reliability 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forghani-elahabad, M.; Kagan, N. Reliability evaluation of a stochastic-flow network in terms of minimal paths with budget constraint. IISE Transactions 2019, 51, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liang, M.; Tian, R.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, X. Reliability Optimization of Hybrid Systems Driven by Constraint Importance Measure Considering Different Cost Functions. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.F.; Gao, Z.Y.; Lam, W.H. A new efficient algorithm for finding all d-minimal cuts in multi-state networks. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2017, 166, 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Jia, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, P. Reliability of high-speed electric multiple units in terms of the expanded multi-state flow network. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2022, 225, 108608. [Google Scholar]

- Fathabadi, H.S.; Forghani-elahabadi, M. A note on “A simple approach to search for all d-MCs of a limited-flow network”. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2009, 94, 1878–1880. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, W.C.; Hao, Z.; Forghani-elahabad, M.; Wang, G.G.; Lin, Y.L. Novel binary-addition tree algorithm for reliability evaluation of acyclic multistate information networks. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2021, 210, 107427. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Z.; Yeh, W.C.; Liu, Z.; Forghani-elahabad, M. General multi-state rework network and reliability algorithm. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2020, 203, 107048. [Google Scholar]

- Shier, D.R. Network reliability and algebraic structures; Clarendon Press, 1991.

- Forghani-elahabad, M.; Bonani, L.H. Finding all the lower boundary points in a multistate two-terminal network. IEEE Transactions on Reliability 2017, 66, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, W.C. An improved sum-of-disjoint-products technique for the symbolic network reliability analysis with known minimal paths. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2007, 92, 260–268. [Google Scholar]

- Forghani-elahabad, M.; Kagan, N. An approximate approach for reliability evaluation of a multistate flow network in terms of minimal cuts. Journal of Computational Science 2019, 33, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, W.C. A fast algorithm for searching all multi-state minimal cuts. IEEE Transactions on Reliability 2008, 57, 581–588. [Google Scholar]

- Mansourzadeh, S.M.; Nasseri, S.H.; Forghani-elahabad, M.; Ebrahimnejad, A. A Comparative Study of Different Approaches for Finding the Upper Boundary Points in Stochastic-Flow Networks. International Journal of Enterprise Information Systems (IJEIS) 2014, 10, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forghani-Elahabad, M. 3 The Disjoint Minimal Paths Reliability Problem. In Operations Research; CRC Press, 2022; pp. 35–66.

- Niu, Y.F.; Xu, X.Z. A new solution algorithm for the multistate minimal cut problem. IEEE Transactions on Reliability 2019, 69, 1064–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jane, C.C.; Laih, Y.W. A practical algorithm for computing multi-state two-terminal reliability. IEEE Transactions on reliability 2008, 57, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forghani-elahabad, M.; Kagan, N.; Mahdavi-Amiri, N. An MP-based approximation algorithm on reliability evaluation of multistate flow networks. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2019, 191, 106566. [Google Scholar]

- Kozyra, P.M. The usefulness of (d, b)-MCs and (d, b)-MPs in network reliability evaluation under delivery or maintenance cost constraints. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2023, 234, 109175. [Google Scholar]

- Forghani-elahabad, M.; Francesquini, E. Usage of task and data parallelism for finding the lower boundary vectors in a stochastic-flow network. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2023, p. 109417.

- Kozyra, P.M. An Innovative and Very Efficient Algorithm for Searching All Multistate Minimal Cuts Without Duplicates. IEEE Transactions on Reliability 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forghani-elahabad, M.; Francesquini, E. An Improved Vectorization Algorithm to Solve the d-MP Problem. Trends in Computational and Applied Mathematics 2023, 24, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Peng, R.; Yang, L.; Wu, T.; Liu, D.; Li, Y. Reliability evaluation of demand-based warm standby systems with capacity storage. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2022, 218, 108132. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.K. Extend the quickest path problem to the system reliability evaluation for a stochastic-flow network. Computers & Operations Research 2003, 30, 567–575. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, W.C.; Chang, W.W.; Chiu, C.W. A simple method for the multi-state quickest path flow network reliability problem. 2009 8th International Conference on Reliability, Maintainability and Safety. IEEE, 2009, pp. 108–110.

- Forghani-elahabad, M.; Mahdavi-Amiri, N. A New Algorithm for Generating All Minimal Vectors for the q SMPs Reliability Problem With Time and Budget Constraints. IEEE Transactions on Reliability 2015, 65, 828–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khadiri, M.; Yeh, W.C.; Cancela, H. An efficient factoring algorithm for the quickest path multi-state flow network reliability problem. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2023, 179, 109221. [Google Scholar]

- Forghani-elahabad, M.; Mahdavi-Amiri, N. An efficient algorithm for the multi-state two separate minimal paths reliability problem with budget constraint. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2015, 142, 472–481. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, W.C. A simple universal generating function method to search for all minimal paths in networks. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics-Part A: Systems and Humans 2009, 39, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, W.C. A fast algorithm for quickest path reliability evaluations in multi-state flow networks. IEEE Transactions on Reliability 2015, 64, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.K. Spare routing reliability for a stochastic flow network through two minimal paths under budget constraint. IEEE transactions on reliability 2010, 59, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Forghani-Elahabad, M.; Mahdavi-Amiri, N.; Kagan, N. On multi-state two separate minimal paths reliability problem with time and budget constraints. International Journal of Operational Research 2020, 37, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forghani-elahabad, M.; Mahdavi-Amiri, N. An improved algorithm for finding all upper boundary points in a stochastic-flow network. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2016, 40, 3221–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, A.O.; Traldi, L. Preprocessing minpaths for sum of disjoint products. IEEE Transactions on Reliability 2003, 52, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaff, A.; Qomarudin, M.N.; Bilfaqih, Y. Network reliability analysis: matrix-exponential approach. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2021, 212, 107591. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, M.J.; Tian, Z.; Huang, H.Z. An efficient method for reliability evaluation of multistate networks given all minimal path vectors. IIE transactions 2007, 39, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Tian, Z.; Zuo, M.J. An improved algorithm for finding all minimal paths in a network. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2016, 150, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fathabadi, H.S.; Soltanifar, M.; Ebrahimnejad, A.; Nasseri, S. Determining all minimal paths of a network. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 2009, 3, 3771–3777. [Google Scholar]

- Forghani-elahabad, M.; Bonani, L.H. An improved algorithm for RWA problem on sparse multifiber wavelength routed optical networks. Optical switching and networking 2017, 25, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, E.D.; Moré, J.J. Benchmarking optimization software with performance profiles. Mathematical programming 2002, 91, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| d | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 96 | 283 | 0.0015 | 0.0054 | 3.5430 |

| 102 | 270 | 0.0012 | 0.0052 | 4.4396 |

| 108 | 254 | 0.0012 | 0.0051 | 4.3694 |

| 114 | 224 | 0.0011 | 0.0053 | 4.9603 |

| 120 | 204 | 0.0010 | 0.0050 | 5.1865 |

| 126 | 192 | 0.0009 | 0.0051 | 5.7419 |

| 132 | 177 | 0.0009 | 0.0050 | 5.6753 |

| 138 | 167 | 0.0009 | 0.0050 | 5.6062 |

| 144 | 147 | 0.0008 | 0.0072 | 8.5036 |

| 150 | 137 | 0.0011 | 0.0050 | 4.4366 |

| Geo. Mean | 0.0011 | 0.0053 | 5.2463 | |

| n | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | 30369 | 12356 | 1.314 | 8.577 | 6.528 |

| 32 | 25518 | 10487 | 0.911 | 5.285 | 5.802 |

| 33 | 35999 | 14713 | 1.756 | 10.996 | 6.263 |

| 34 | 22646 | 9425 | 0.795 | 4.476 | 5.631 |

| 35 | 45378 | 18715 | 2.953 | 18.958 | 6.420 |

| 36 | 33208 | 13773 | 1.710 | 10.398 | 6.080 |

| 37 | 63354 | 26457 | 6.498 | 43.972 | 6.767 |

| 38 | 39762 | 16763 | 2.428 | 14.160 | 5.832 |

| 39 | 80121 | 33274 | 8.966 | 60.483 | 6.746 |

| 40 | 49725 | 20963 | 4.249 | 26.568 | 6.252 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).