1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a complex of interconnected metabolic, regulatory, and neuroendocrine abnormalities that culminate in the development of visceral obesity, hyperglycemia, and insulin resistance (IR). Given the pervasive prevalence of sedentary lifestyle and unhealthy dietary habits characterized by the excessive consumption of processed foods laden with excess fat and carbohydrates, and a genetic predisposition, MetS has emerged as a burgeoning global health concern, affecting an increasingly large segment of the population. Individuals afflicted with MetS face a significantly elevated risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular pathologies such as heart failure, arrhythmias, coronary and peripheral arterial complications, and stroke [

1,

2,

3,

4].

In cases of severe type 2 diabetes, morbid obesity, and other profound pathological states, researchers have documented a substantial decline in mitochondrial function through numerous investigations. This mitochondrial dysfunction is linked to insulin resistance, ectopic lipid accumulation, abnormal apoptosis, and noticeable functional impairment across various organs. Prominent factors contributing to mitochondrial dysregulation and damage include the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, impairment of DNA repair, increase in production of toxic metabolic intermediates, protein glycosylation, and the activation of many other pathological pathways [

5,

6]. Nevertheless, as individuals progress through the continuum of diabetes, MetS, and its complications, mitochondria may undergo diverse functional rearrangements that remain poorly understood. While severe complications of MetS typically correspond to decreased oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), studies conducted on mild obesity-related pathologies and experimental models have unveiled a spectrum of changes ranging from moderate impairment to a sufficient respiration increase. Furthermore, these changes exhibit regional disparities in various tissues. Special attention has been directed towards adipose tissues, as numerous studies have highlighted the pivotal role of impaired lipid storage in the development of MetS. However, due to the heterogeneous nature of models and methodologies employed, conflicting reports abound regarding tissue respiration in different organs. Respiratory function in liver and muscles, for instance, has been observed to vary from a moderate decline to a moderate enhancement [

7,

8].

It is worth noting that some research has suggested that mitochondrial stimulation leading to increased bioenergetics can ameliorate obesity-related disorders in certain MetS models [

9,

10]. In many metabolic syndrome models obesity is not present and biochemical disturbances may vary [

11,

12]. It still not completely understood, what factors could contribute to obesity resilience and further metabolic health. Mitochondrial activity could take part in key processes, as it is linked to main metabolic routes.

In the scope of our study, we decided to investigate two distinct models of obesity-related disorders: a MetS rat model induced by the replacement of water with a 20% fructose solution, representing a less complicated MetS model, and a type 2 diabetes rat model induced by a lipid-enriched diet combined with a single 25 mg/kg streptozotocin injection, replicating metabolic disorder with many complications. Typically, fructose-enriched diets do not result in a significant weight gain but do shift lipid storage towards visceral adipose tissues. Conversely, lipid-enriched diet models combined with streptozotocin injections can induce severe hyperglycemia and other metabolic disturbances, including weight gain and dyslipidemia. We picked two models with distinct metabolic pathologies to catch polar disease states that usually are linked in human diseases, according to many previous published works [

11,

12].

2. Results

2.1. Metabolic Syndrome Features

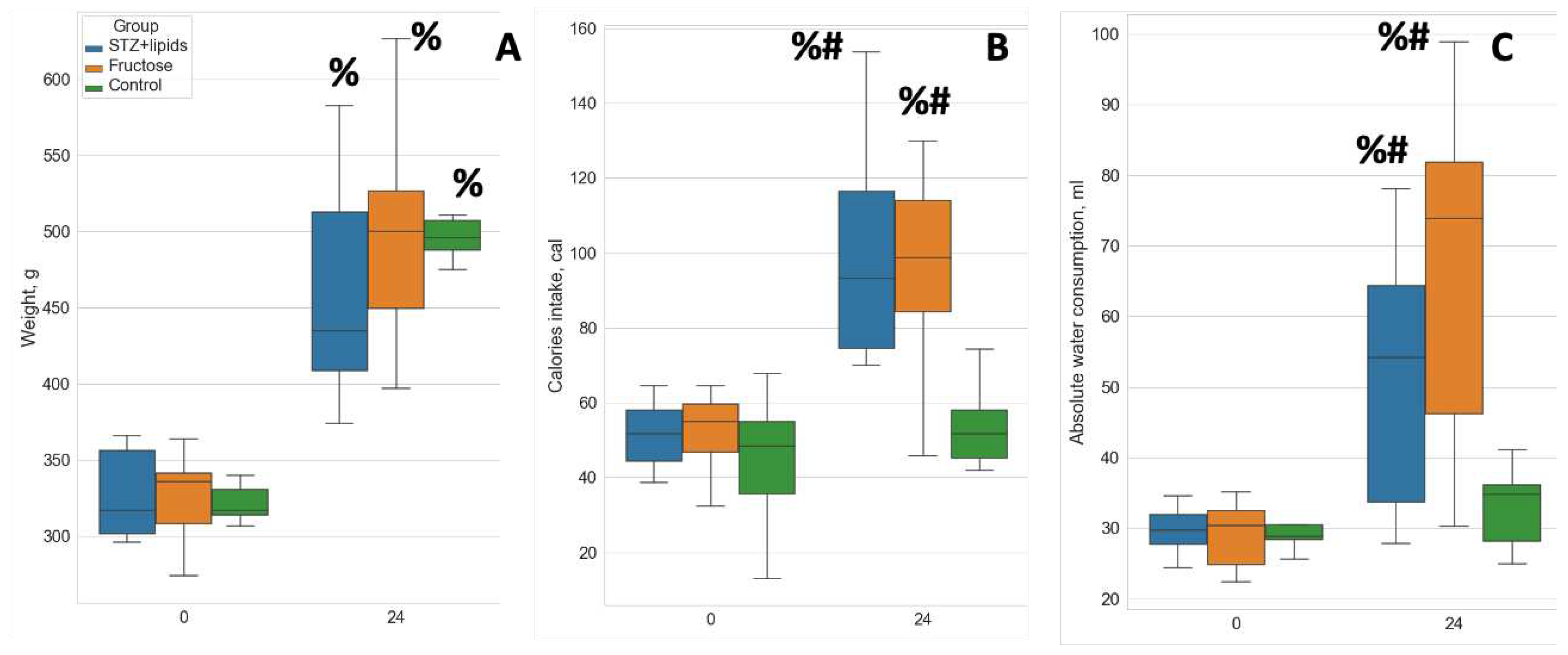

By the end of the study, all rats exhibited a notable increase in body weight. Although no statistically significant differences were observed among the groups, there was a noticeably greater dispersion in body weight within the experimental diet groups, with the STZ+lipids group showing the most evident variability (

Figure 1A). Food consumption throughout the study exhibited significant variations across all three groups. Specifically, rats in the Fructose group consumed considerably less food while receiving an equivalent calorie intake to the STZ+lipids group rats. Caloric intake was significantly higher in both experimental groups compared to the Control group (

Figure 1B). Furthermore, water intake was significantly elevated in both the STZ+lipids and Fructose groups when compared to the Control group (

Table 1).

The injection of streptozotocin induced a marked and sustained elevation in glucose levels. After 24 weeks of the experiment, glucose level was significantly higher in the STZ+lipids group when compared to both the Fructose and Control groups, with a median level of 21 mmol/l (

Figure 2A, p<0.01). Additionally, rats in the STZ+lipids group exhibited a significant increase in ketone bodies, with levels significantly higher than those in both the Fructose and Control groups, with a median level of approximately 1 mmol/l (

Figure 1D). Notably, insulin levels exhibited a significant reduction in the blood of rats in both the STZ+lipids and Control groups, with no significant differences observed between these two groups (

Figure 2B).

Based on insulin and glucose levels, the HOMA-IR index was found to be consistent across all groups at week 24, providing no evidence for insulin resistance (

Figure 2C). Dyslipidemia features were assessed by measuring venous blood triglyceride levels. Surprisingly, a significant increase was observed in all three groups, including the Control group. Triglyceride levels tended to be higher in the STZ+lipids group when compared to the Control group (p=0.068) and the Fructose group (p=0.09) (

Figure 2E). Interestingly, the TyG surrogate insulin resistance index was significantly elevated in the STZ+lipids group (

Figure 2E), although we did not conduct gold standard tests for comparing insulin resistance. Triglycerides level got higher through the experiment in all groups, though STZ+lipid group trended for higher level, but results were not statistically significant compared to control. Elevation in the Control group could be linked to aging, as the body weight in normal rats increased.

The impact of weight gain varied among the three groups and was influenced by various factors. In the Control group, weight exhibited a significant correlations only with adipocyte length (measured as Feret diameter) and BAT weight (

Table 2). As other factors were not significant, we propose that weight differences between animals in the Control group could be defined by their genetics and social interactions.

In the Fructose group, weight significantly correlated with calories intake, higher triglyceride concentration, insulin concentration, glucose level, water consumption, organs weight. Hence in the Fructose group there was a straight relationship between excessive consumption, weight gain and metabolic disturbances.

In contrast, the STZ+lipids group presented a different pattern, with higher weight observed in rats with less severe metabolic disturbances: lower glucose level, ketone bodies concentration, TyG index. At the same time rats with higher weight had larger adipocytes and increased adrenal gland weight, which overall was higher in STZ+lipids group.

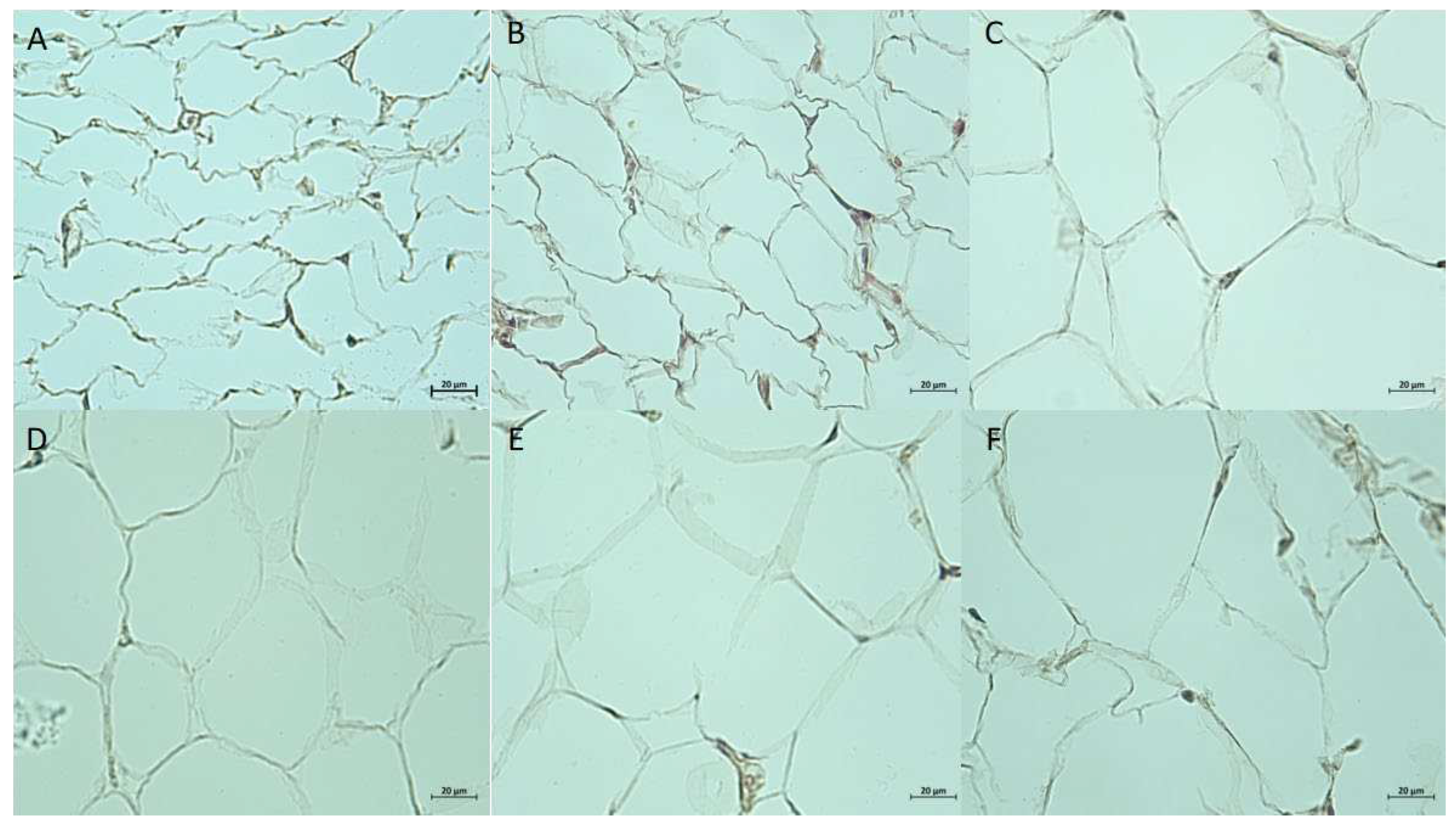

2.3. Adipose Tissue Morphology

Adipose tissue pieces from 3 depots were fixed in 4% formaldehyde solution and processed for paraffin embedding. PE slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for morphological analysis. In general SAT has more diversity in composition, with areas of connecting tissue and large vessels. VAT pieces consist almost exclusively of large size adipocytes with a minimal amount of intercellular substance and scarce capillary. BAT consists of areas with brown adipocytes or white adipocytes of intermediate size. Brown adipocytes vary in the size of lipid droplets and color intensity. Further comparative analysis was performed for SAT and VAT slides (

Figure 2).

Quantitative morphological analysis revealed significant differences in adipocyte size and density. In SAT average number of adipocytes per field of view (FOV, 100x magnification) was significantly higher in the Fructose group compared to control (21.3, IQR 20.3, 22.1 vs 18.5, IQR 16.4, 20.6, p = 0.02). Average cell area in SAT did not show significant differences despite lower median value in the Fructose group, while cell perimeter was lower in the STZ+lipids group comparing to Control (78.57 μm, IQR 77.73, 85.88 μm vs 97.2 μm, IQR 84.51, 101.78 μm, p=0.047). In VAT average cell number was significantly higher in both experimental groups compared to control (9.4, IQR 8.9, 10.1 in STZ+lipids, 9.4, IQR 9.1, 10.2 in Fructose, 7.7, IQR 6.9, 9.2 in Control, p=0.033, p=0.041). Average cell area was significantly lower in experimental groups compared to control (2534 μm

2, IQR 2327 μm

2, 2865 μm

2 in STZ+lipids, 2425 μm

2, IQR 2340 μm

2, 2807 μm

2 in Fructose, 3131 μm

2, IQR 2774 μm

2, 3653 μm

2 in Control, p=0.02, p=0.016), as well as average cell perimeter (74 μm, IQR 70.5, 78.8 μm in STZ+lipids, 73.4 μm, IQR 69.2, 78.2 μm in Fructose, 88.5 μm, IQR 75.7 μm, 108.7 μm in Control, p=0.033, p=0.031). Length of the cell was measured as a Feret diameter, and got in line with cellular perimeter and area (

Table 3).

Average capillary density per FOV was measured manually for 3 types of adipose tissues. Because BAT has several times more capillaries, for that type of tissue they were counted in grid intersections. In SAT and VAT all capillaries in FOV were identified. While median capillary density was higher in experimental groups in 3 depots, no statistical differences were found compared to control.

2.2. Respirometry Analysis

Solid tissue samples exhibit significant variability in structure, and the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) is profoundly influenced by the architectural features of the organ. The advancement of intact tissue respirometry encompasses several benefits, including sustained tissue viability, reduced time from excision to testing, preservation of cellular properties, and expedited preparation. Furthermore, we postulate that the architectural integrity of intact tissue samples mitigates the spillage of cytoplasmic components following permeabilization. This phenomenon may elucidate certain deviations from the anticipated OCR dynamics observed during the SUIT protocol. Although the enhanced dynamics enable a reduction in testing time, they do come at the cost of decreased parameter stability. Therefore, we regard this modification of respirometry as a rapid screening approach for identifying more prominent effects and relationships.

Permeabilization with saponin promptly resulted in a significant increase in respiration rate across all tissue types. However, OCR subsequently declined in state 2, and further ADP injection led to an increase in OCR via complex I. Interestingly, the addition of succinate to stimulate complex I+II respiration did not elicit a substantial increase in OCR in any of the tissues studied. We hypothesize that complex II was already sufficiently saturated in the tissue samples under investigation. Notably, even nanogram/ml doses of oligomycin efficiently induced a leak respiration state with low OCR values. The subsequent SUIT step typically involves protonophore titration. In some instances, we observed consistent OCR rates after multiple CCCP injections across different tissue samples. To expedite testing, we administered the same single CCCP dose to all tissues. Overall, the maximal electron transport system (ETS) flow was several times higher than the leak OCR but approximated the rate of state 3 respiration. This pattern aligns with observations reported by some authors, which they attribute to a high degree of permeabilization.

To evaluate complex II respiration, we employed rotenone to inhibit electron flow from complex I, revealing the rate of complex II-mediated respiration. Notably, the OCR attributed to complex II was markedly lower in comparison to that of complex I or ETS. In the control group, complex II OCR was nearly negligible in all adipose tissues. Finally, we treated the samples with the complex III inhibitor Antimycin A to uncover residual respiration, which was subsequently subtracted from all OCR values. The residual respiration rate was negligible across all adipose tissues.

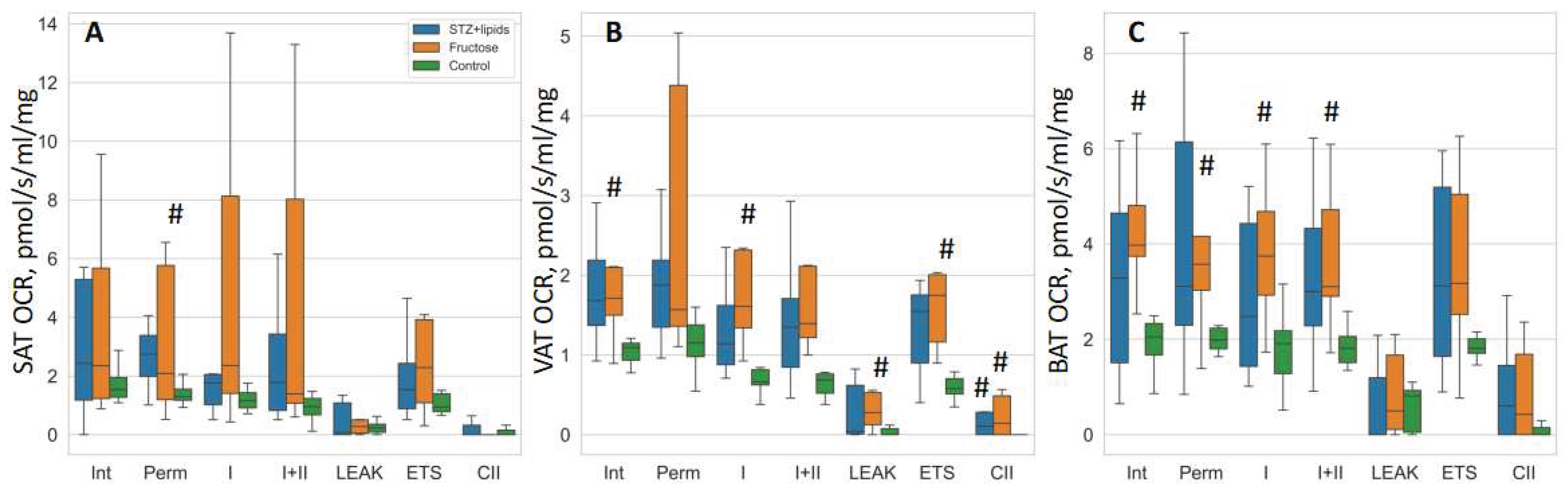

In our investigation utilizing OCR studies were conducted on isolated tissues, we observed a discernible trend of elevated respiration rates in the high-energy diet groups, although it is important to note that the statistical significance of these findings was limited due to the small sample size and considerable data spread. To assess group differences, we employed Kruskal-Wallis tests followed by DSCF post-hoc tests. While the median values indicated higher respiration rates in nearly all respiratory states across the three adipose tissues, the most notable and statistically significant differences were observed within the visceral adipose tissue.

Specifically, in the Fructose group, OCR rates were consistently higher compared to the Control group across various respiration states, including intact respiration, complex I state 3 respiration, LEAK, ETS, and CII respiration. Conversely, in the STZ+lipids group, OCR rates displayed a trend towards significant differences compared to the Control group in multiple respiration states, with significance reaching statistical significance only in the case of CII respiration within the visceral adipose tissue. In the subcutaneous adipose tissue, the Fructose group exhibited higher OCR rates in the permeabilized state when compared to the Control group. Furthermore, in the brown adipose tissue, the Fructose group demonstrated elevated OCR rates in various respiratory states, including intact, permeabilized, CI, and CI+CII respiration, when compared to the Control group.

Table 4.

OCR values in 3 types of adipose tissues. Data presented as median (IQR) in pmol/s/ml/mg.

Table 4.

OCR values in 3 types of adipose tissues. Data presented as median (IQR) in pmol/s/ml/mg.

| |

Brown Adipose Tissue |

Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue |

Visceral Adipose Tissue |

| Respiration state |

STZ+lipids |

Fructose |

Control |

STZ+lipids |

Fructose |

Control |

STZ+lipids |

Fructose |

Control |

| Intact |

3.3 (1.7,4.5) |

4.0 (3.7,4.8) |

2.1 (1.7,2.3) |

2.4 (1.2,5.1) |

2.4 (1.3,4.9) |

1.5 (1.3,2.0) |

1.7 (1.3,2.4) |

1.7 (1.5,2.1) |

1.1 (0.9,1.15) |

| Permeabilized |

3.1 (2.4,6.0) |

3.6 (3.0,4.2) |

2.0 (1.8,2.2) |

2.7 (2.0,3.3) |

2.1 (1.2,5.0) |

1.3 (1.2,1.7) |

1.9 (1.35,2.4) |

1.6 (1.4,3.7) |

1.15 (1.0,1.4) |

| Complex I |

2.5 (1.5,4.1) |

3.8 (2.9,4.7) |

1.9 (1.3,2.2) |

1.8 (1.1,2.0) |

2.4 (1.5,7.2) |

1.2 (0.9,1.5) |

1.1 (0.8,1.75) |

1.6 (1.4,2.3) |

0.7 (0.6,0.8) |

| Complex I+II |

3 (2.3,4.0) |

3.1 (2.9,4.7) |

1.8 (1.5,2.1) |

1.8 (0.9,3.1) |

1.4 (1.1,6.5) |

1.0 (0.7,1.2) |

1.3 (0.8,1.7) |

1.4 (1.2,2.1) |

0.7 (0.5,0.75) |

| LEAK |

0.01 (0,0.9) |

0.5 (0.1,1.7) |

0.8 (0.05,0.9) |

0.1 (0,1.0) |

0.3 (0.1,0.5) |

0.2 (0.05,0.4) |

0.04 (0.01,0.7) |

0.3 (0.1,0.5) |

0.01 (0,0.07) |

| Maximal ETS |

3.1 (1.8,5.1) |

3.2 (2.5,5.0) |

1.8 (1.7,2.0) |

1.5 (0.9,2.2) |

2.3 (1.1,3.7) |

0.9 (0.8,1.4) |

1.5 (0.8,1.8) |

1.8 (1.3,2.0) |

0.6 (0.5,0.7) |

| CII respiration |

0.6 (0,1.3) |

0.4 (0,1.7) |

0.01 (0,0.15) |

0.01 (0,0.2) |

0.01 (0,0.05) |

0.01 (0,0.15) |

0.1 (0,0.3) |

0.14 (0.01,0.4) |

0.01 (0,0.02) |

In summary, high-energy diets appear to elicit a substantial increase in mitochondrial respiration. The Fructose metabolic syndrome model offers a continuous influx of readily available nutrients, primarily impacting insulin-dependent tissues. Conversely, the STZ+lipids diabetes model results in reduced insulin levels, potentially leading to diminished nutrient delivery to adipose tissue and a consequent reduction in respiratory capacity. Remarkably, in both models, rats did not exhibit greater weight gain compared to the Control group, despite a significantly higher caloric intake sustained over the course of the 24-week experiment. This suggests that the heightened adipose tissue respiration observed may signify an acquired ability of fat tissue to efficiently utilize excessive nutrients, potentially through an increase in mitochondrial abundance or an upregulation of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS).

Figure 3.

Boxplot of mitochondrial respiration rates. (A) – SAT, (B) – VAT, (C) – BAT. # - p<0.05 compared to the Control. Int – intact respiration, Perm – permeabilized respiration, I – complex I respiration, I+II – complex I + complex II respiration, LEAK – uncoupled respiration, ETS – maximal electron transport system respiration, CII – isolated complex II respiration.

Figure 3.

Boxplot of mitochondrial respiration rates. (A) – SAT, (B) – VAT, (C) – BAT. # - p<0.05 compared to the Control. Int – intact respiration, Perm – permeabilized respiration, I – complex I respiration, I+II – complex I + complex II respiration, LEAK – uncoupled respiration, ETS – maximal electron transport system respiration, CII – isolated complex II respiration.

Correlation analyses have revealed that in STZ+ lipids group higher respiration was associated with larger VAT and SAT cell size, which is closer to Control group. Low respiration was also correlated with higher triglycerides level in SAT and higher heart and adrenal glands weight in VAT. Hence, metabolically unhealthy rats may have closer to baseline respiration, while increased respiration in STZ+lipids group could be compensatory. In the Fructose group higher respiration also correlated with adipocyte size, lower calories intake and weight in VAT and SAT. Interestingly, in BAT glucose concentration (which was in a normal range) also positively correlated with a tissue respiration. Negative correlation of BAT weight and BAT respiration could indicate for higher white adipocytes proportion.

Table 5.

Most significant correlations for respiratory indexes in SAT and VAT in experimental groups.

Table 5.

Most significant correlations for respiratory indexes in SAT and VAT in experimental groups.

| STZ+lipids |

Respiratory State |

R |

p |

Fructose |

Respiratory State |

R |

p |

| SAT |

|

|

|

SAT |

|

|

|

| Capillaries in FOV |

ETS |

0.64 |

0.047 |

Average cell area, SAT |

Leak |

0.79 |

0.006 |

| Average cell perimeter, SAT |

Leak |

0.84 |

0.002 |

Weight |

ETS |

-0.73 |

0.018 |

| Triglycerides concentration |

Intact |

-0.67 |

0.03 |

Calories intake |

ETS |

-0.63 |

0.048 |

| VAT |

|

|

|

VAT |

|

|

|

| Heart weight |

Intact |

-0.75 |

0.03 |

Weight |

I+II |

-0.66 |

0.036 |

| Adrenal glands weight |

Leak |

-0.78 |

0.04 |

Calories intake |

I+II |

-0.63 |

0.049 |

| |

|

|

|

Triglycerides concentration |

ETS |

-0.65 |

0.04 |

| BAT |

|

|

|

BAT |

|

|

|

| Calories intake |

I+II |

-0.68 |

0.03 |

Pancreas weight |

ETS |

-0.80 |

0.009 |

| Average cell perimeter, VAT |

I+II |

0.69 |

0.026 |

|

I+II |

-0.67 |

0.05 |

| |

Leak |

0.63 |

0.049 |

Glucose concentration,

mixed blood |

ETS |

0.75 |

0.019 |

| Average cell perimeter, SAT |

Leak |

0.64 |

0.047 |

|

I+II |

0.90 |

0.001 |

| |

|

|

|

BAT weight |

I+II |

-0.72 |

0.045 |

3. Discussion

Cellular respiration is a complex process influenced by multiple factors, including mitochondrial density, substrate availability, regulatory modifications, ROS (Reactive Oxygen Species) production, mitochondrial membrane composition, and more. Obesity and obesity-related conditions stem from an abundance of low-quality energetic substrates. Key biochemical changes occur within adipose depots, where additional substrates are stored and managed. Most lipids are stored in subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) depots, but their overload redirects nutrient flow to visceral adipose tissue (VAT), contributing to more severe obesity and Metabolic Syndrome (MetS). Brown and beige adipocytes are notable for their ability to uncouple Oxidative Phosphorylation (OXPHOS) through the specific UCP1 protein, directly converting energetic metabolites into heat. However, these adipocytes are not abundant in adults, and limited data exist regarding OXPHOS activity in adipocytes during MetS development.

In our study, we assessed cellular respiration in permeabilized adipose tissue samples from three groups of male Wistar rats: the Control group, being fed a standard chow diet; the Fructose group, which received a 20% fructose solution instead of water; and the STZ+lipids group, that were administrated a lipid-enriched diet and a single 25 mg/kg streptozotocin injection. We followed the standard SUIT protocol for assessing tissue respiration [

13]. Generally, all respiratory states (intact, permeabilized, complex I+II, maximal Electron Transport Chain activity) were strongly correlated with each other (correlation coefficient around 0.9), suggesting that none of the respiratory complexes underwent specific changes. Leak respiration showed somewhat lower correlations with other respiratory states (correlation coefficient 0.4-0.5), but intergroup changes were consistent across all respiratory states. Mean and median respiration values were higher in both the Fructose and STZ+lipids groups compared to the Control group. Notably, more rats in the Fructose group exhibited elevated cellular respiration, resulting in significantly higher median values compared to the Control group, especially in visceral and brown adipose tissues.

Several factors could contribute to the increased cellular respiration, including substrate availability, higher mitochondrial density, and activation of regulatory pathways. An important question is whether the additional energy is used for anabolic reactions, such as adipose tissue expansion, or dissipated as heat through uncoupled or leak respiration. We observed that in Control rats, leak respiration was much higher in brown adipose tissue (BAT) than in white adipose tissue (WAT) or SAT. In contrast, in experimental groups, leak respiration increased in VAT and SAT, reaching BAT levels. However, BAT showed consistent median values across all three groups.

Clearly, both substrate-related ATP-producing respiration and leak respiration increased in experimental groups in different adipose tissues. Consequently, we evaluated associated metabolic and hemodynamic changes in each group separately to identify related patterns. For SAT and VAT both experimental groups had the same factors influencing respiration. While generally experimental groups experienced changes in VAT and SAT morphology with smaller, more abundant adipocytes, larger size correlated with higher respiration, probably indicating better compensation.

In the Fructose group, rats received significantly more calories, mainly from the fructose solution, resulting in calorie overflow and nutrient imbalance. While the median weight in the Fructose group did not differ significantly from the Control group, it positively correlated with triglycerides and insulin concentrations. Perhaps, higher sugar load could lead to further body mass increase [

14]. Elevated cellular respiration in BAT positively correlated with glucose levels and BAT weight. In SAT, it correlated with triglycerides levels and weight, while in VAT, it correlated with triglycerides levels. It is plausible that increased cellular respiration, particularly leak respiration, contributes to delayed weight gain, as evidenced by the striking differences in calorie intake and weight gain between the Fructose and Control group animals. Elevated triglyceride levels may play a major role in this phenomenon, but further research is required for clarification.

In the STZ+lipids group, we also observed increased cellular respiration, but metabolic features exhibited different patterns. Often STZ+lipids model leads to significant obesity with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes features, as reported in the literature [

15,

16,

17]. Shortly after the STZ injection, rats in the STZ+lipids group experienced severe hyperglycemia, with a median level around 20 mmol/l. Insulin levels decreased but not significantly compared to other groups. Another metabolic disturbance included significant hyperketonemia, likely linked to hyperglycemia. Higher metabolic impairment (glucose and ketone body levels) correlated with lower body weight but also higher food consumption, although weight did not correlate with food consumption. Consequently, rats with high fat intake developed severe metabolic disturbances but gained less weight. As higher glucose concentration did not correlate with a respiration increase, and elevated triglycerides correlated with lower respiration, probably increased respiration retains larger cell size and better biochemical profile, and those mechanisms are not compromised by the high glucose level.

One notable difference between the STZ+lipids and fructose models were their glucose concentration dynamics. In the pure MetS model, such as the fructose model, weight gain is often not observed, although the reasons remain incompletely understood. It is possible that rodents exhibit a high level of resilience to caloric overload, or longer durations are required to achieve significant weight gain. In contrast, the STZ+lipids model mimics type 2 diabetes, and outcomes can vary widely depending on the severity of β-cell damage. In our study, rats in the STZ+lipids group developed severe hyperglycemia, which is not conducive to weight gain.

It is well-established that obesity, hyperglycemia, and insulin resistance coincide with structural and functional alterations in mitochondria, including changes in density and dynamics (fusion and fission) [

18]. Multiple studies have demonstrated decreased mitochondrial respiration in adipose tissue, skeletal muscle [

19,

20,

21], and heart myocytes in insulin-deficient, insulin-resistant states, and obesity-related conditions. In these conditions, there is often a reduction in mitochondrial respiration. Furthermore, an increase in fatty acid flux, as seen in prediabetic states involving obesity and hyperglycemia, can lead to elevated substrate delivery to mitochondria, promoting ROS production, mitochondrial dysfunction, and exacerbating hyperglycemia. Impairment in mitochondrial biogenesis may also contribute to the decrease in oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial density observed in diabetes.

On the other hand, there is evidence of increased mitochondrial function in certain forms of obesity. For instance, studies by A. Bohm et al. have demonstrated altered mitochondrial respiration in subcutaneous adipocytes of individuals with different obesity phenotypes. Adipocytes from metabolically unhealthy subjects exhibited increased basal respiration, higher proton leak, elevated ATP production, increased maximal respiration, and higher spare respiratory capacity, compared to metabolically healthy obesity. These findings were negatively correlated with the insulin sensitivity of the donors [

22]. Studies in different animal models provided variety of responses and therefore some of them could lead to protective mechanisms [

23]. Our studies in rat adipose tissue depots support these findings, although we did not observe signs of insulin resistance in the two MetS models. We used the HOMA-IR index for insulin resistance assessment, which was originally developed for humans. Therefore, it is possible that this index may not accurately reflect insulin sensitivity in rats [

20,

21]. In both MetS models, we observed increased respiration in all types of adipose tissues, but the increase was associated with rats in different metabolic states. In the Fructose model, increased respiration corresponded to rats with less severe dyslipidemia, whereas in the STZ+lipids model, it was associated with rats with higher food consumption and worse glucose and ketone body levels. By those feats, the STZ+lipids model more closely resembles the metabolically unhealthy human obesity phenotype, despite not exhibiting severe obesity. Adipocytes size is usually higher in obese people and in metabolic syndrome models with an increased body weight [

26,

27]. While in our study models had different biochemical properties, they responded very similar on an adipose tissue level.

In conclusion, our study sheds light on the intricate interplay between cellular respiration, metabolic changes, and adipose tissue morphology in different models of MetS and diabetes in rats. The findings highlight the variability in metabolic responses within and between these models. It is evident that the relationship between mitochondrial respiration, metabolic disturbances, and adipose tissue morphology is complex and context dependent. Further research is warranted to elucidate the precise mechanisms underlying these interactions and their implications for metabolic health. Both fructose and high-fat diet + streptozotocin models lead to severe morphological changes in adipose tissue and are suitable to compare.

4. Materials and Methods

Animal Handling

The experiment received approval from the local bioethics committee during its 147-d meeting held on December 16, 2022. Male Wistar rats with a body weight ranging from 300 to 325g (N=31) were obtained from a standard pathogen-free (SPF) breeding facility in Pushino, Russia. Throughout the experiment, the animals were housed in a certified vivarium with a 12-hour day/night cycle and were provided with ad libitum access to food and water. Upon arrival, the animals were categorized into their respective groups based on their body weight and placed in standard T3 cages accommodating three rats each. After an initial 2-week period of acclimatization and handling, baseline biochemical and physiological assessments were conducted over a 2-week period. The experimental diet was initiated at the beginning of the experiment, and measurements were repeated after 24 weeks to assess metabolic and hemodynamic features.

A total of 31 animals were distributed into three groups: 8 in the Control group, 11 in the Fructose group, and 12 in the Streptozotocin + Lipids (STZ+lipids) group. Rats in the Control group were fed a standard chow diet (comprising 3.8% fat, 52.1% carbohydrates, 20% protein, 4.3% fiber, and 1.3% salt based on wet weight) and had free access to tap water. In the Fructose group, water was replaced with a 20% fructose solution, while the STZ+lipids group received a micronutrient-balanced chow containing 58% of calories derived from lipids, which was achieved by mixing standard chow powder with lard, casein, and salts. Two weeks after the experiment's commencement, rats in the STZ+lipids group received an intraperitoneal injection of 25 mg/kg streptozotocin (Sigma) dissolved in 1 ml of cold citrate buffer (+4oC, pH=4.5). It's noteworthy that all rats in this group developed hyperglycemia three days after the injection and remained part of the study. Mortality was not assessed in the study, as only one rat from the Control group died due to anesthesia overdose.

Rat body weight was measured using a laboratory scale (Sartorius) with a readability of 100 mg. Food and water (or fructose solution) consumption were monitored in individual cages. Food was weighed initially and after 24 hours, including any visible remnants within the cage. Similarly, water weight was recorded in the bottle before and after 24-hour caging. Total caloric intake, nutrient and pure water consumption were calculated based on these values.

Biochemical Analysis

Blood glucose and ketone body concentrations were assessed in mixed blood samples obtained from tail tips using a glucometer (One Touch Verio Pro) and a ketone bodies analyzer (Optium Xceed), both equipped with original test strips. The samples were collected from conscious rats using a sterile scarificator. A volume of 2 ml of blood was drawn from the jugular vein under isoflurane anesthesia, with citrate anticoagulant added. The blood was then centrifuged at 1000g for 10 minutes in a refrigerated centrifuge (Eppendorf 5804R), and the plasma layer was collected. Subsequently, insulin, glucose, cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations were measured in the plasma samples. Glucose, cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations were determined using standard colorimetric kits (Vector-Best, Russia), while insulin concentration was measured using ELISA kits (Vektor-Best, Russia), following the manufacturer's protocol. Colorimetric and ELISA assays were performed at 37°C using a PerkinElmer Enspire plate reader at the appropriate wavelengths. All measurements were conducted in triplicate, and concentrations were calculated from calibration curves constructed using kit control samples.

Respirometry Study

After 24 weeks of the experiment, animals were euthanized through a stepwise overdose of chloral hydrate. Brown fat pads, heart, liver, kidneys, adrenal glands were weighed using a Sartorius balance with a readability of 10 mg, and adipose tissue samples were analyzed in the following order: brown fat sample (approximately 20 mg), visceral fat sample (approximately 50 mg from the abdominal cavity), and inguinal subcutaneous fat sample (approximately 30 mg). Tissue samples were precisely weighed using an analytical scale (Ohaus AX224) before the respirometry assays and placed in cold respiration buffer.

All oxygen consumption rate (OCR) tests were conducted using the Oxygraph module (HansaTech instruments) with a standard liquid chamber and Oxygraph software. The oxygen sensor was calibrated at the beginning of each experimental day using an internal program with sodium dithionite. Prior to the tests, tissue samples were immersed in 1 ml of Mir05 respiration buffer medium (composed of 110 mM sucrose, 60 mM potassium lactobionate, 20 mM HEPES, 10 mM KH2PO4, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, pH 7.4, reagents from Sigma) at a room temperature. The chamber and plunger were rinsed multiple times with ultrapure water between different runs. Tissue samples were kept in the cold solution for up to 10 minutes before the study. A simplified SUIT (substrate-uncoupler-inhibitor titration protocol) respiration protocol was used to conduct multiple tissue tests sequentially within one Oxygraph chamber. Each substrate and inhibitor were added only once to achieve maximum effect in a short duration, based on preliminary research on liver samples. The next step was initiated after the OCR had stabilized. Short steps were also feasible due to the relatively large size of the tissue samples, allowing for rapid absorption of inhibitors. On average, each tissue test run lasted about 10 minutes.

The following sequence of steps was employed during the respirometry assays:

Intact Respiration: Tissue samples were initially placed in the chamber to measure intact respiration.

Permeabilized Base Respiration (State 2): 5 mg/ml saponin (Macklin, China) was taken for tissue permeabilization, 5 mM sodium malate and 5 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma) were added to stimulate permeabilized base respiration (State 2).

Stimulation of State 3 Respiration Through Complex I: 2 mM ADP (magnesium stabilized, Sigma) was added to stimulate state 3 respiration through complex I.

Maximal Respiration Through Complexes I and II: 5 mM sodium succinate (Sigma) was added to achieve maximal respiration through complexes I and II.

State 4 Respiration (Leak): State 4 respiration (leak) was measured after injecting 10 nM oligomycin (Sigma).

Maximal Respiratory Capacity (Uncoupled Respiration): Maximal respiratory capacity (uncoupled respiration) was measured after adding 1 mM carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP, Sigma) in DMSO (Sigma).

Complex I-Specific Respiration Rate: Following OCR stabilization, rotenone (Sigma) was added to measure complex I-specific respiration rate.

Residual (Background) Respiration: Finally, 5 mM antimycin A (Sigma) was added to measure residual (background) respiration.

Raw oxygen concentration data were recorded and saved in .csv format for further analysis.

Histological study

Parts of adipose tissue were fixed in a 10% formaldehyde solution for 24 hours. After washing excessive formaldehyde, tissues were dehydrated through isopropyl alcohol solutions, mineral oil and liquid paraffin, then embedded in paraffin. 5 micron slides were sliced with a Thermo Scientific S355 microtome and placed on Thermo SuperFrost slides. After drying overnight at 37oC, slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin using a standard protocol. After dehydration cover slides were mounted. Images were acquired with a Zeiss AxioImager A2 microscope. Image processing was performed with an ImageJ software. Pictures were gamma-corrected, converted to grayscale, sharpen, then border finding and thresholding were performed. Binary functions were applied for small holes correction, then missing membrane segments were restored manually. Particle analysis was performed, then masks were overseen to include adipocytes only. Cell area, perimeter and Feret diameter were calculated automatically.

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

All data processing and analysis were conducted using the Python 3.8 programming language and open-source code libraries. The Pandas and Numpy libraries were utilized for converting raw data into tables and processing oxygen concentrations into OCR using a consistent algorithm. The table of oxygen concentrations was segmented based on reagent addition events, and 10-second margins were trimmed to eliminate external O2 fluctuations. Within each segment between two events, the median oxygen shift over 1 second was calculated to reduce noise. The averaged median shifts within the segment were then used to calculate raw OCR. Weight-adjusted values were computed to obtain measurements in nmol/s/ml/g dimensions. All values were corrected for residual respiration rate and converted to absolute values. The resulting data were utilized for subsequent statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statsmodels and Scipy libraries. Due to the relatively small sample sizes, non-parametric statistical tests and universal statistical models were employed. The Statsmodels library's mixed-effects generalized linear model (GLM) was used to analyze time-dependent changes. For dependent variables, the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed, followed by post-hoc multiple comparisons using the Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Fligner (DSCF) test. Screening correlation analyses were conducted using simple Pearson R calculations and heatmaps. All p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data visualization was carried out using boxplots, depicting medians, quartiles, and minimum/maximum values, with Matplotlib and Seaborn libraries facilitating plot creation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Raw data of respiratory indexes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: E.I., S.G.; methodology, E.I.; software, A.E.; validation: A.E., M.A., S.G.; formal analysis: E.I.; investigation: E.I., A.R.; resources; E.I., A.E., M.A., A.R., S.G.; data curation, E.I., A.E.; writing, original draft preparation, E.I., writing, review, and editing: E.I., A.E., M.A., A.R., S.G.; visualization, E.I., S.G.; supervision, S.G.; project administration, E.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Moscow State University (protocol code 147-d date of approval 16.12.2022).”.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Purwowiyoto, S.L.; Prawara, A.S. Metabolic Syndrome and Heart Failure: Mechanism and Management. Med Pharm Rep 2021, 94, 15–21. [CrossRef]

- Hoetama, E.; Hermawan, B. Metabolic Syndrome : An Emerging Risk Factor for Congestive Heart Failure. Indonesian Journal of Cardiology 2015, 36, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone-Filardi, P.; Paolillo, S.; Costanzo, P.; Savarese, G.; Trimarco, B.; Bonow, R.O. The Role of Metabolic Syndrome in Heart Failure. Eur Heart J 2015, 36, 2630–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.W.F.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Parise, H.; Sullivan, L.; Meigs, J.B. Metabolic Syndrome as a Precursor of Cardiovascular Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Circulation 2005, 112, 3066–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajab, B.S.; Kassab, S.; Stonall, C.D.; Daghistani, H.; Gibbons, S.; Mamas, M.; Smith, D.; Mironov, A.; AlBalawi, Z.; Zhang, Y.H.; et al. Differential Remodelling of Mitochondrial Subpopulations and Mitochondrial Dysfunction Are a Feature of Early Stage Diabetes. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gancheva, S.; Kahl, S.; Pesta, D.; Mastrototaro, L.; Dewidar, B.; Strassburger, K.; Sabah, E.; Esposito, I.; Weiß, J.; Sarabhai, T.; et al. Impaired Hepatic Mitochondrial Capacity in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Associated With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.Y.; Ge, L.H.; Zhang, K.; Chen, H.F.; Zhan, X.X.; Yang, Y.; Dang, Q.L.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, H. Bin; Lyu, J.X.; et al. Assessment of Mitochondrial Function in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease Using Obese Mouse Models. Zool Res 2020, 41, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, N.T.; Pedersen, T.M.; Rossvoll, L.; Hafstad, A.D.; Aasum, E. Diet-Induced Obese Mouse Hearts Tolerate an Acute High-Fatty Acid Exposure That Also Increases Ischemic Tolerance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2020, 319, H682–H693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, D.J.; Sims, H.F.; Yang, K.; Kiebish, M.A.; Su, X.; Jenkins, C.M.; Guan, S.; Moon, S.H.; Pietka, T.; Nassir, F.; et al. Genetic Ablation of Calcium-Independent Phospholipase A2γ Prevents Obesity and Insulin Resistance during High Fat Feeding by Mitochondrial Uncoupling and Increased Adipocyte Fatty Acid Oxidation. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 36495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudoin, M.S.; Snook, L.A.; Arkell, A.M.; Simpson, J.A.; Holloway, G.P.; Wright, D.C. Resveratrol Supplementation Improves White Adipose Tissue Function in a Depot-Specific Manner in Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2013, 305, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastías-Pérez, M.; Serra, D.; Herrero, L. Dietary Options for Rodents in the Study of Obesity. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, T.A.; Woods, S.C. Overview of Animal Models of Obesity. Current protocols in pharmacology / editorial board, S.J. Enna (editor-in-chief) ... [et al.] 2012, CHAPTER, Unit5.61. [CrossRef]

- Pesta, D.; Gnaiger, E. High-Resolution Respirometry: OXPHOS Protocols for Human Cells and Permeabilized Fibers from Small Biopsies of Human Muscle. Methods in Molecular Biology 2012, 810, 25–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, G.; Gutiérrez-Lara, E.J.; Centurión, D.; Granados-Soto, V.; Murbartián, J. Fructose-Induced Insulin Resistance as a Model of Neuropathic Pain in Rats. Neuroscience 2019, 404, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Awar, A.; Kupai, K.; Veszelka, M.; Szűcs, G.; Attieh, Z.; Murlasits, Z.; Török, S.; Pósa, A.; Varga, C. Experimental Diabetes Mellitus in Different Animal Models. J Diabetes Res 2016, 2016, 9051426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sah, S.P.; Singh, B.; Choudhary, S.; Kumar, A. Animal Models of Insulin Resistance: A Review. Pharmacological Reports 2016, 68, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleixandre de Artiñano, A.; Miguel Castro, M. Experimental Rat Models to Study the Metabolic Syndrome. British Journal of Nutrition 2009, 102, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Hu, W.; Gong, X.; Qiu, H.; Chen, H.; Xin, Y.; Li, H. The Role of Mitochondria in Metabolic Syndrome-Associated Cardiomyopathy. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivitz, W.I. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Obesity and Diabetes. US Endocrinol 2010, 6, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudina, S.; Sena, S.; Theobald, H.; Sheng, X.; Wright, J.J.; Xia, X.H.; Aziz, S.; Johnson, J.I.; Bugger, H.; Zaha, V.G.; et al. Mitochondrial Energetics in the Heart in Obesity-Related Diabetes: Direct Evidence for Increased Uncoupled Respiration and Activation of Uncoupling Proteins. Diabetes 2007, 56, 2457–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, M.; Sahlin, K.; Fernström, M.; Glintborg, D.; Vind, B.F.; Beck-Nielsen, H.; Højlund, K. Mitochondrial Respiration Is Decreased in Skeletal Muscle of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1592–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, A.; Keuper, M.; Meile, T.; Zdichavsky, M.; Fritsche, A.; Häring, H.U.; de Angelis, M.H.; Staiger, H.; Franko, A. Increased Mitochondrial Respiration of Adipocytes from Metabolically Unhealthy Obese Compared to Healthy Obese Individuals. Scientific Reports 2020 10:1 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, V.F.; Merce, A.P.; Hâncu, I.M.; Bătrân, A.D.; Kennedy, G.; Rosca, M.G.; Muntean, D.M. Impairment of Mitochondrial Respiration in Metabolic Diseases: An Overview. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, Vol. 23, Page 8852 2022, 23, 8852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Zhan, D.; Li, Z.X.; Wang, H.Y.; Xing, Y.; Luo, X.P. Effect of High-Fat Diet for Rats at Different Stages on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Offspring and Related Mechanisms. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi 2021, 23, 1174–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunes, L.C.; Elkfury, J.L.; Jornada, M.N.; Foletto, K.C.; Bertoluci, M.C. Validation of HOMA-IR in a Model of Insulin-Resistance Induced by a High-Fat Diet in Wistar Rats. Arch Endocrinol Metab 2016, 60, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.R.; Ramli, E.S.M.; Nasir, N.A.A.; Ismail, N.M.; Fahami, N.A.M. Methanolic Extract of Piper Sarmentosum Attenuates Obesity and Hyperlipidemia in Fructose-Induced Metabolic Syndrome Rats. Molecules 2021, Vol. 26, Page 3985 2021, 26, 3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osorio-Conles, Ó.; Vega-Beyhart, A.; Ibarzabal, A.; Balibrea, J.M.; Vidal, J.; de Hollanda, A. Biological Determinants of Metabolic Syndrome in Visceral and Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue from Severely Obese Women. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 2394. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).