Submitted:

10 November 2023

Posted:

10 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

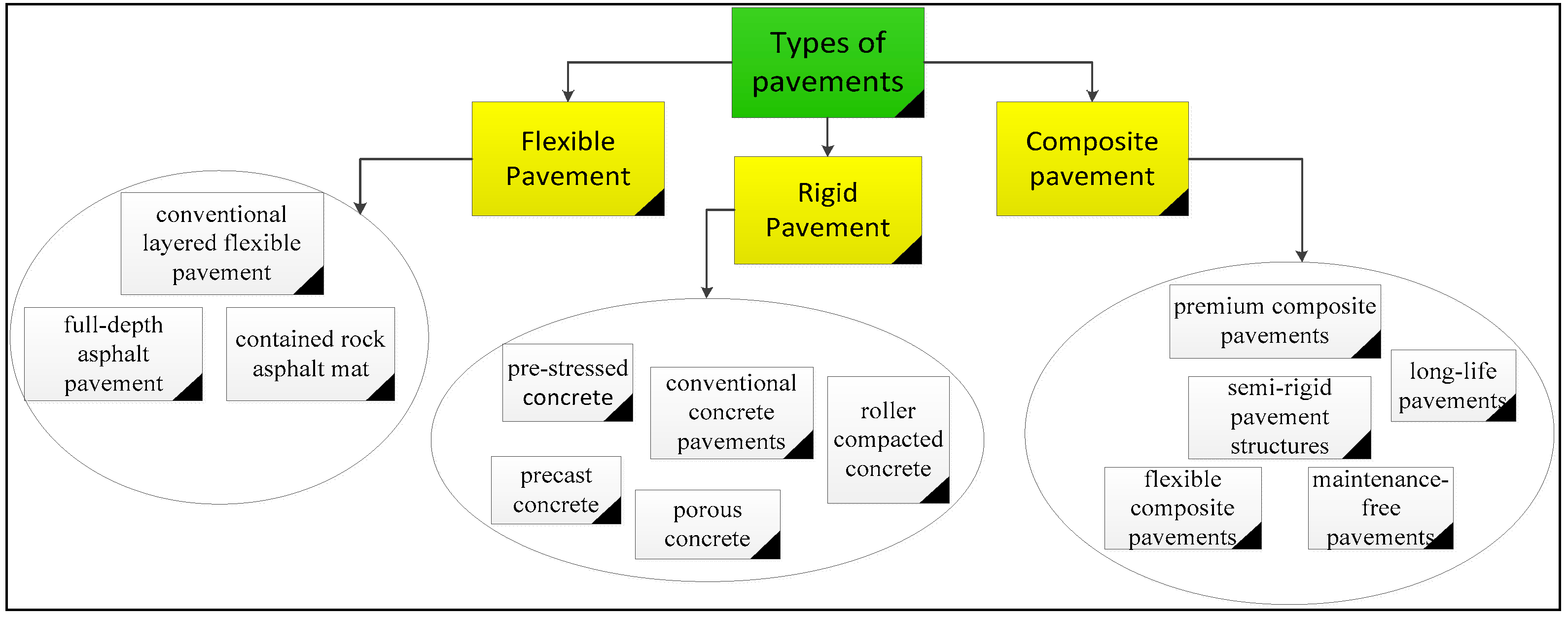

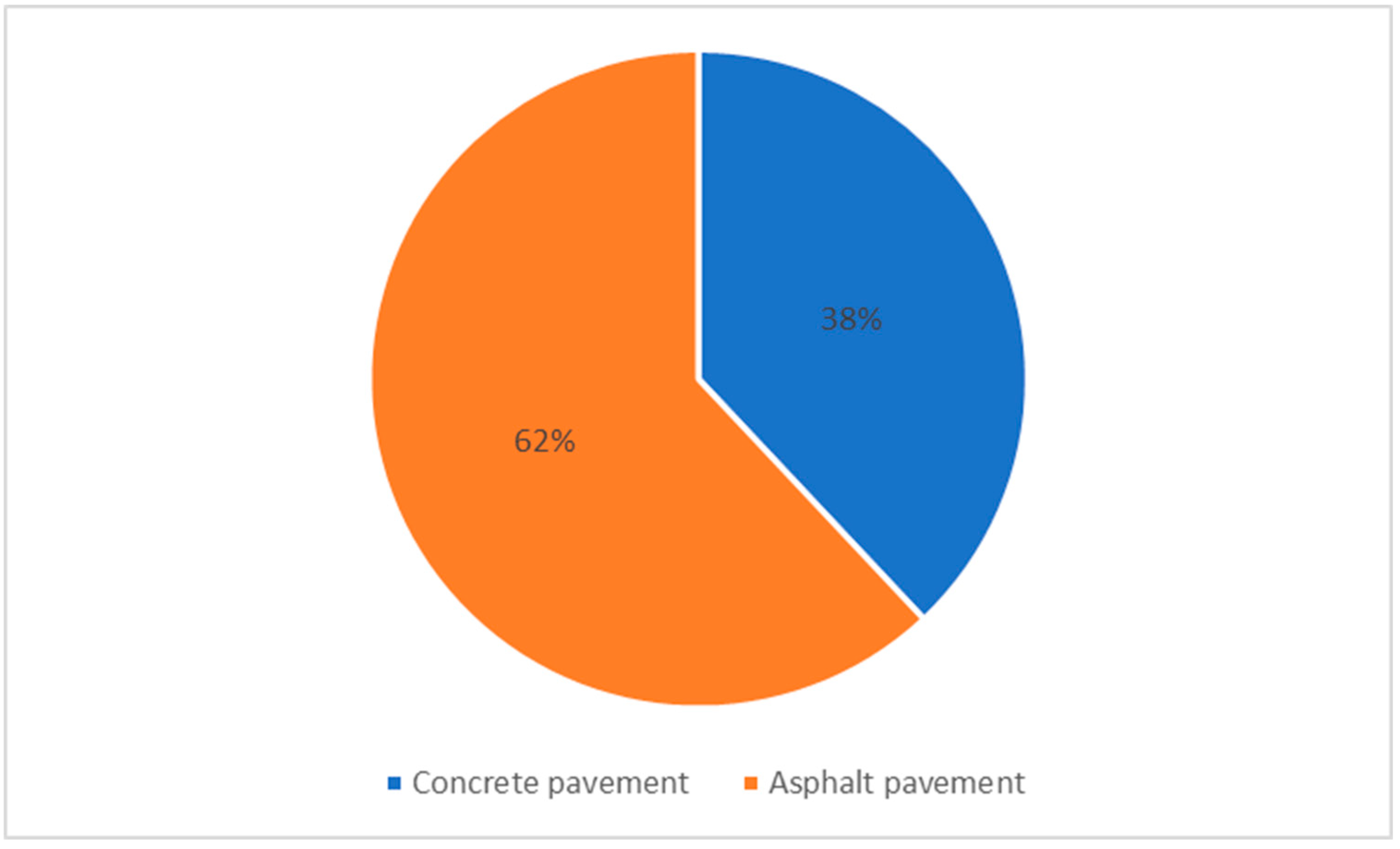

1. Introduction

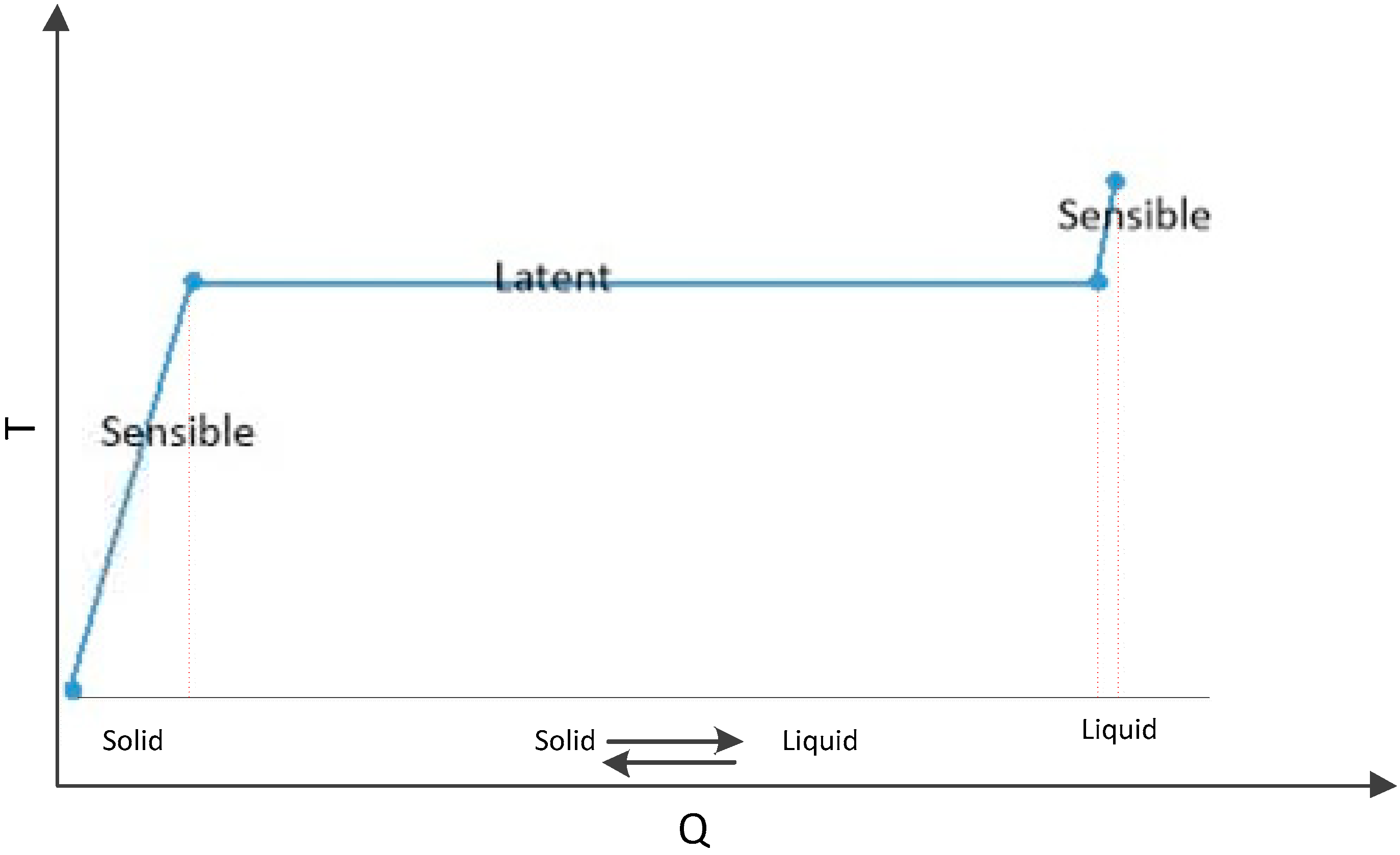

2. Phase change materials (PCMs) in concrete pavements

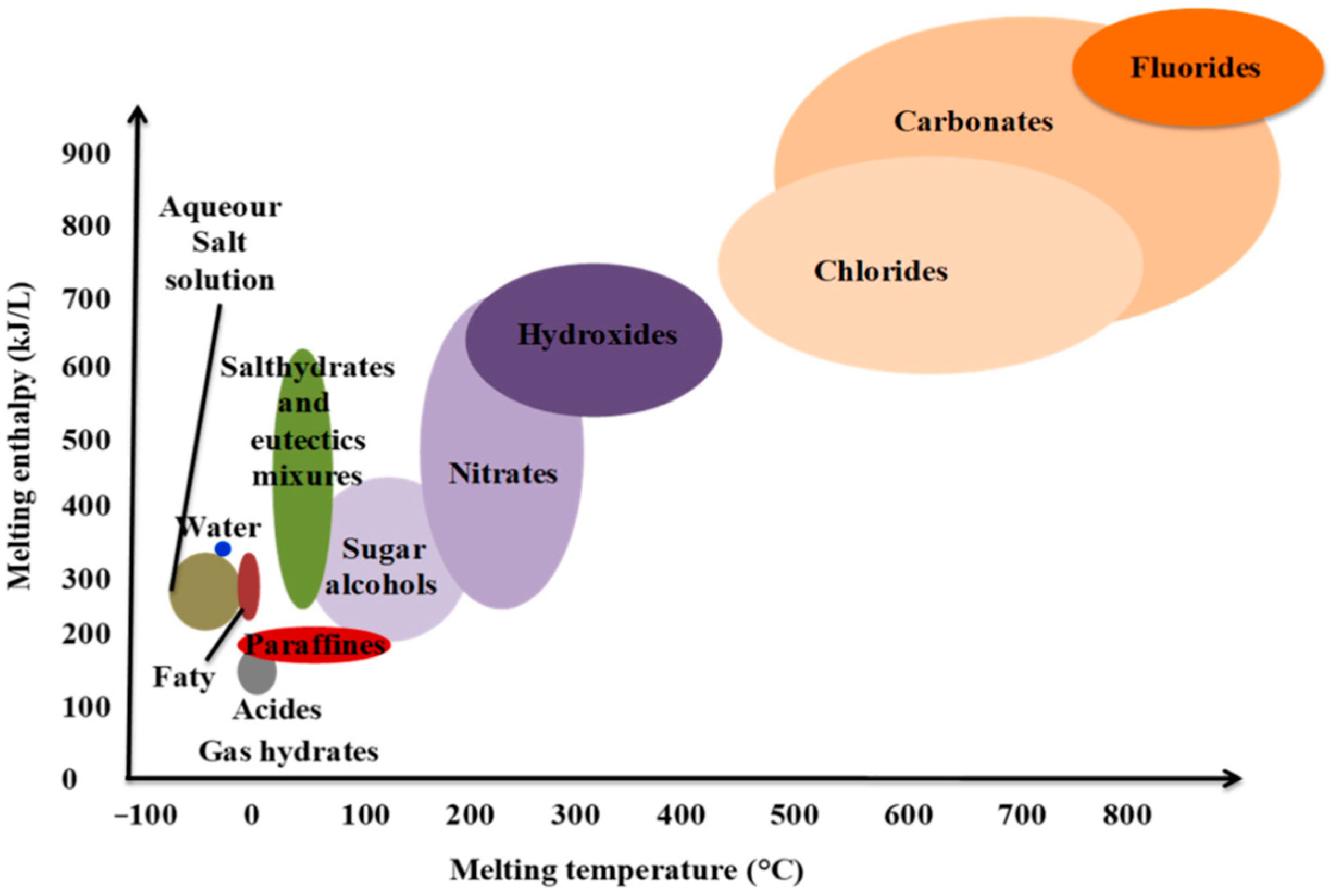

2.1. Type of PCMs in concrete pavements

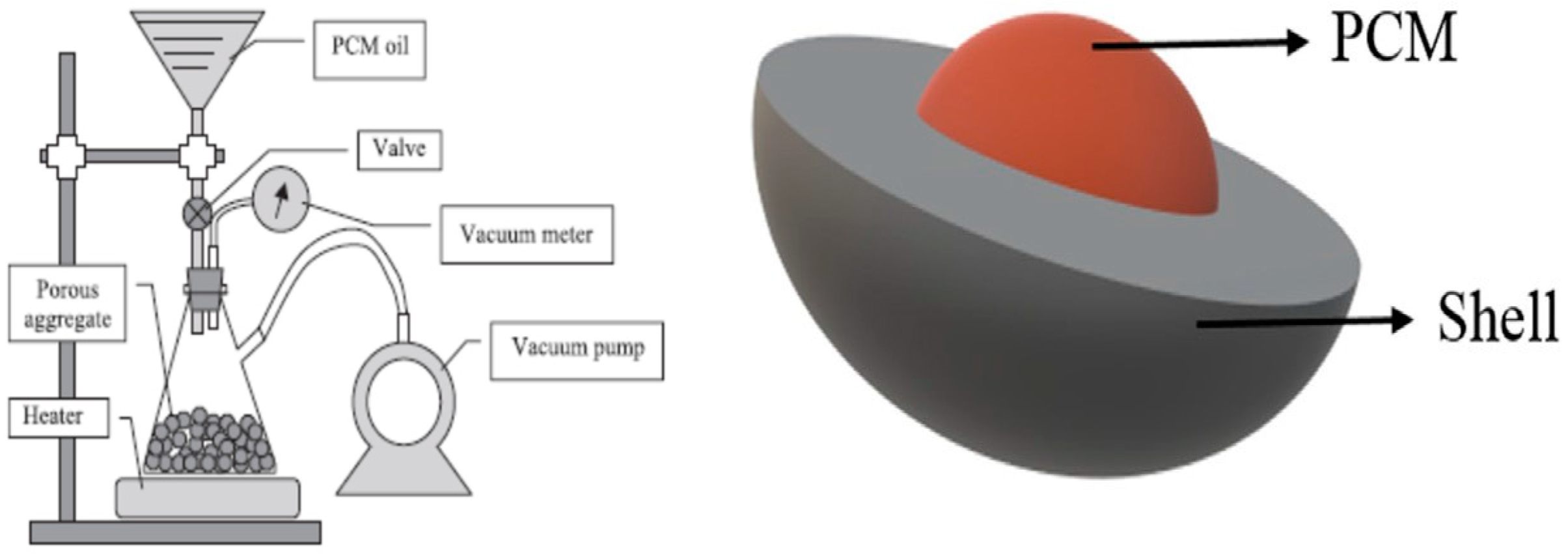

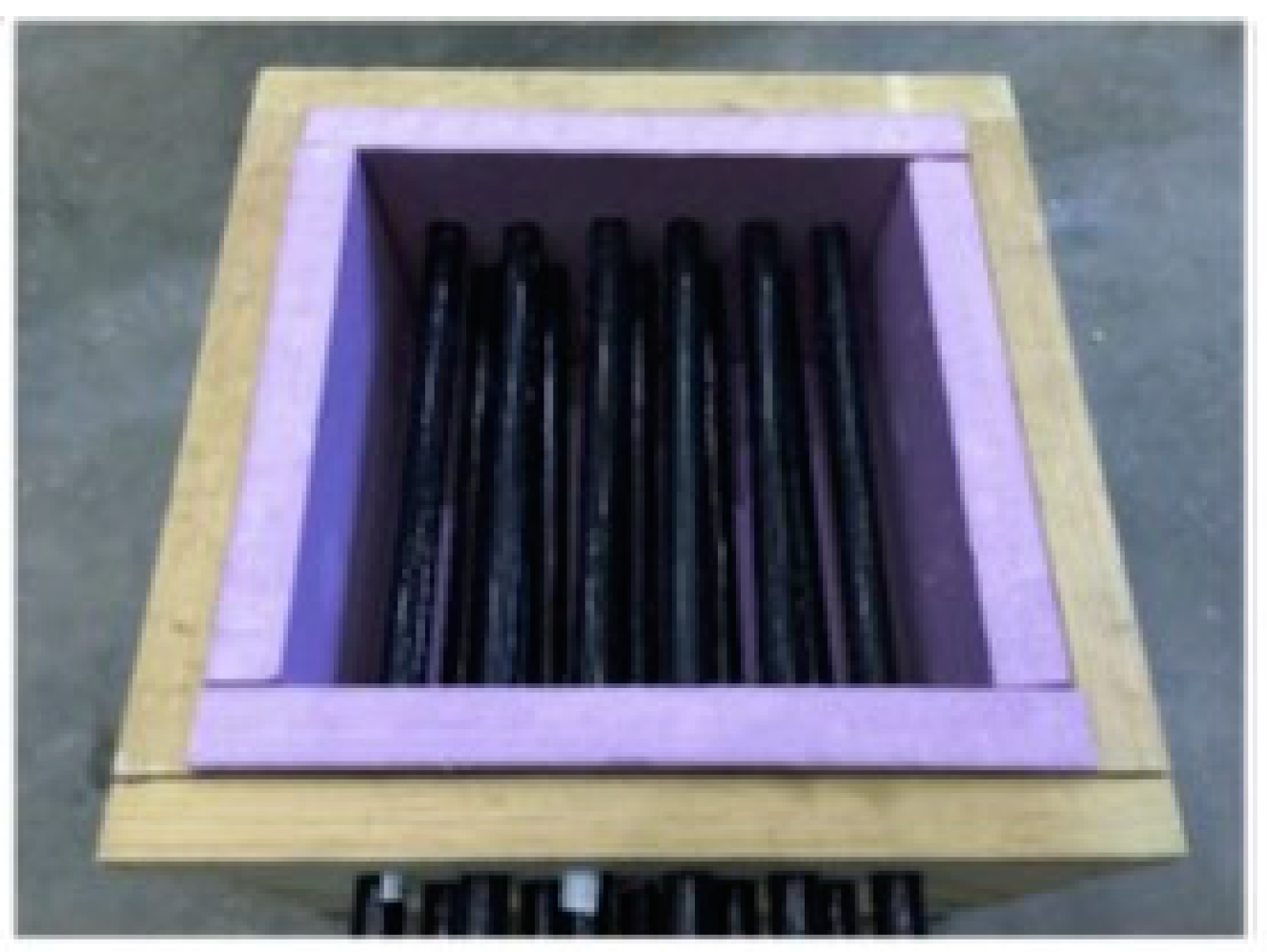

2.2. Methods of incorporation

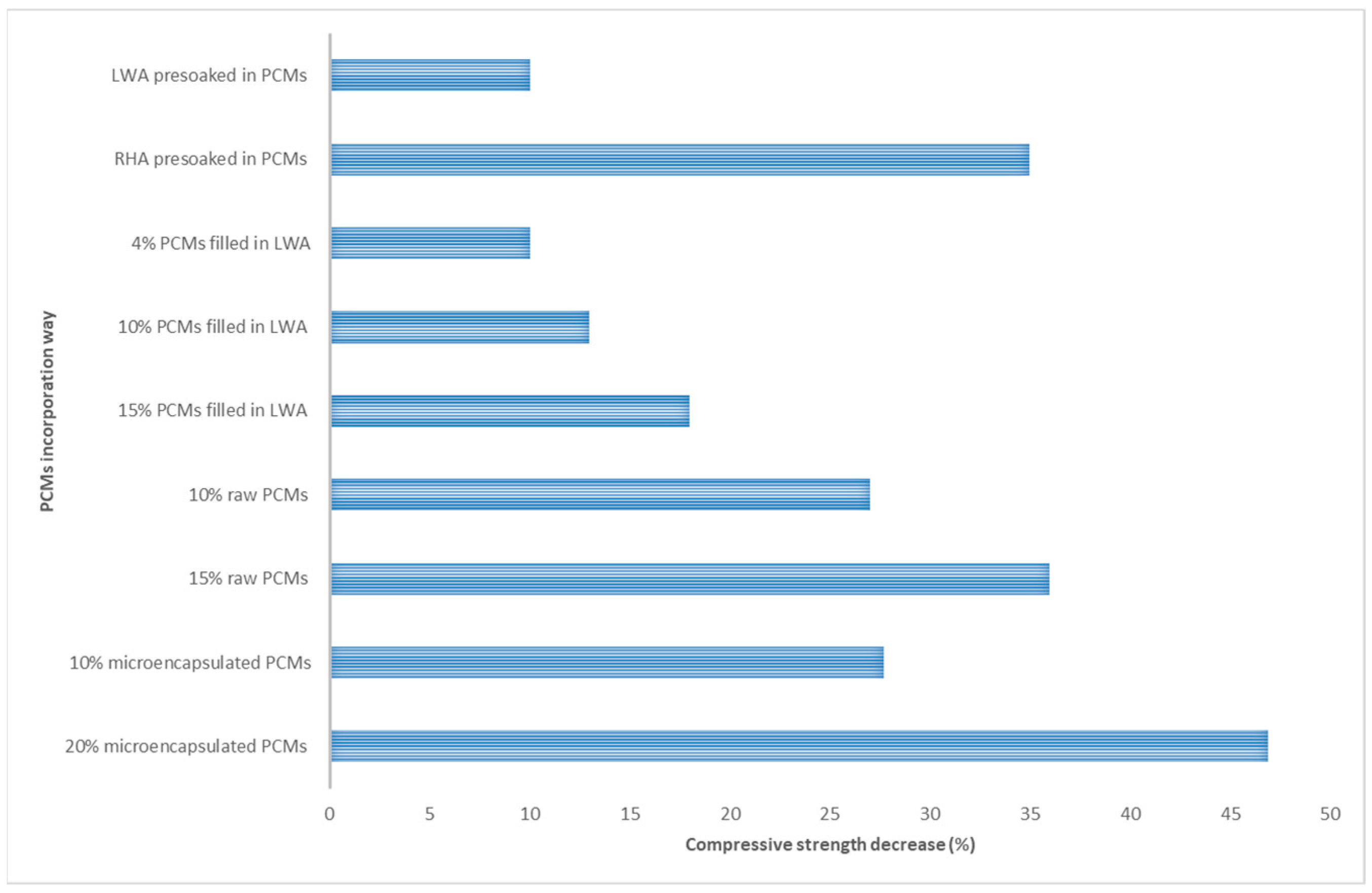

3. The effect of PCMs on the mechanical properties of concrete pavement

4. The effect of PCMs on the heat of hydration of concrete

5. Frost-resistant concrete pavement with PCMs

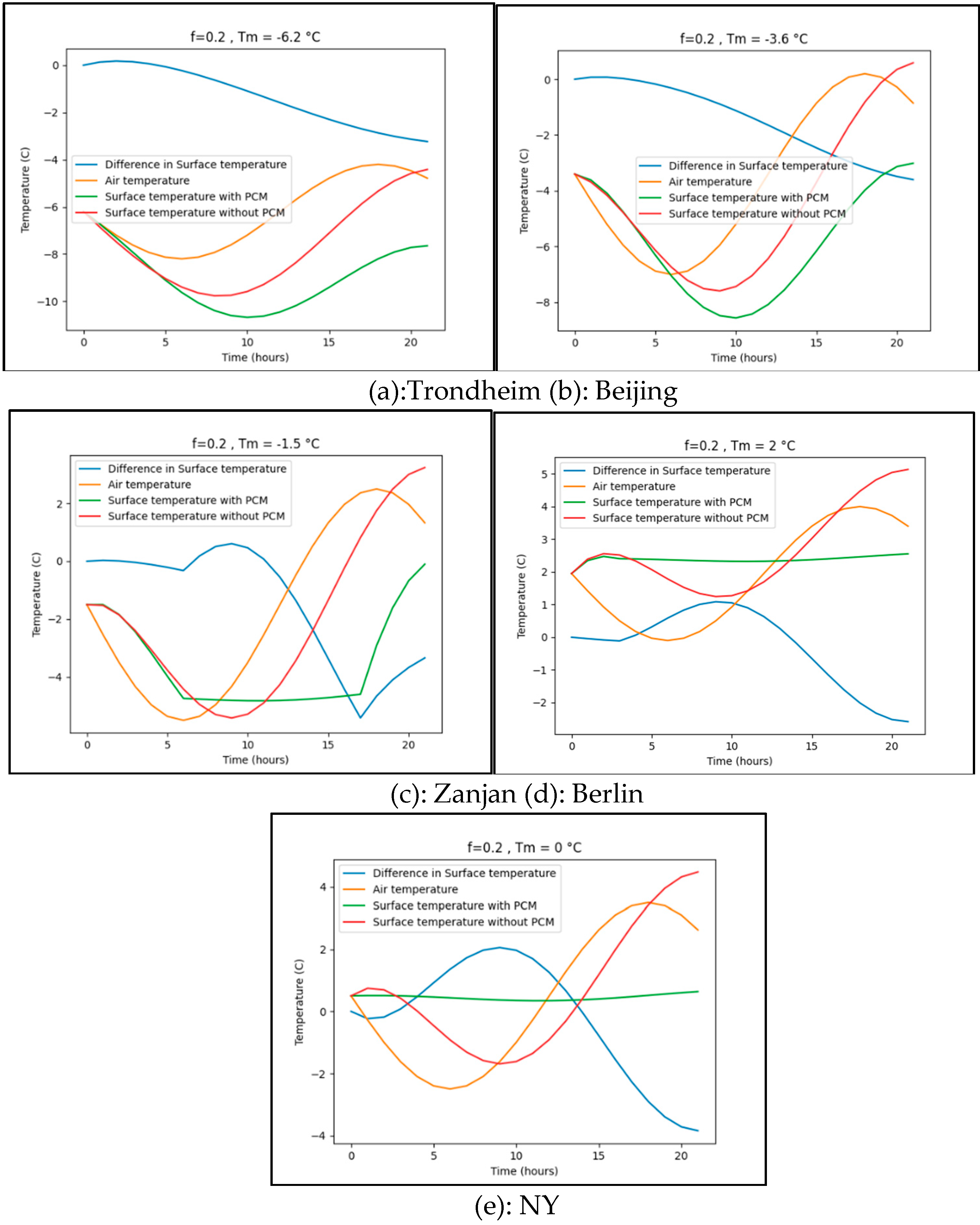

6. The effect of PCMs on the surface temperature and UHI phenomena

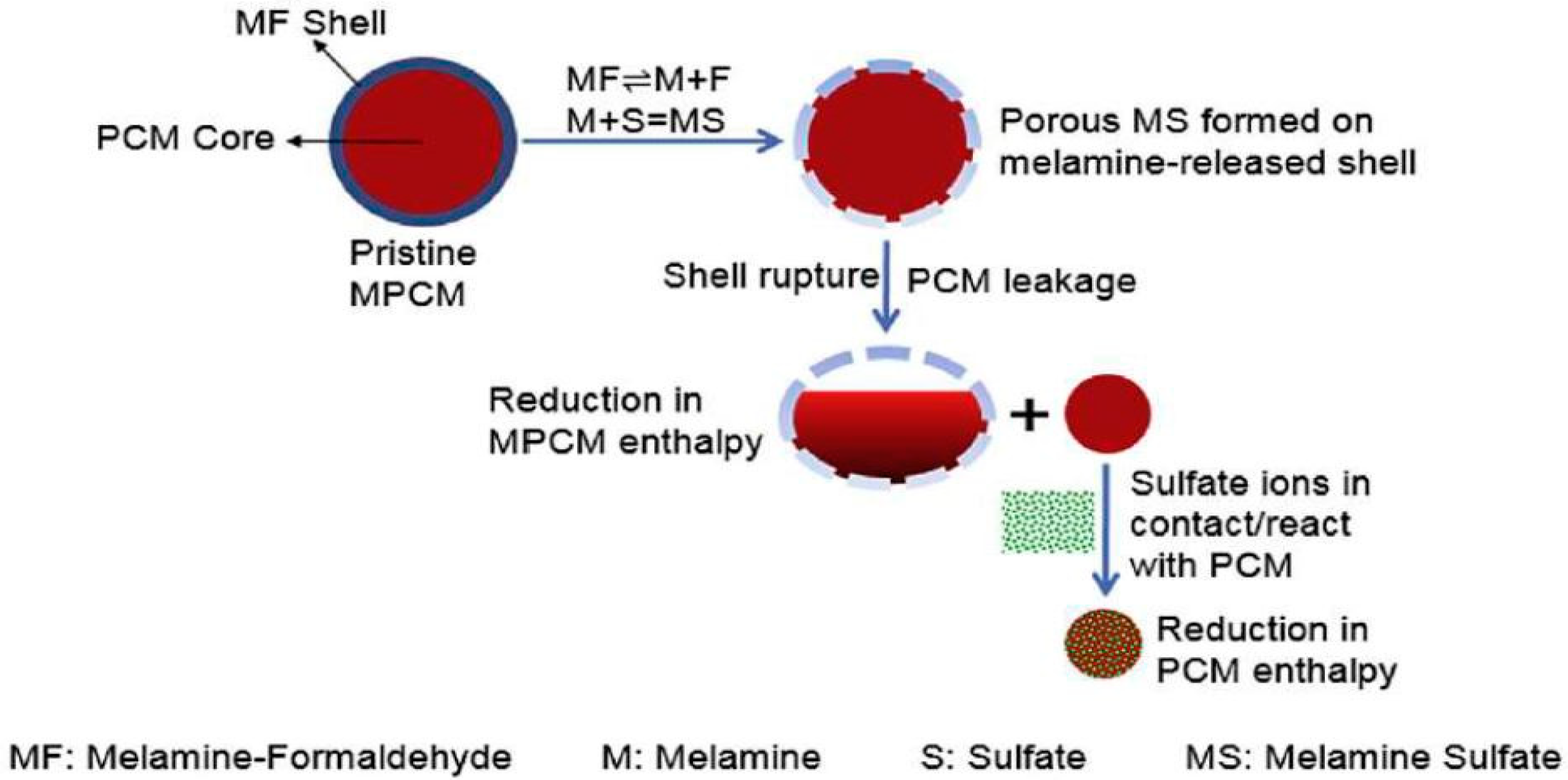

7. The chemical reaction of PCMs inside concrete

8. Discussion

9. Conclusion

Appendix A

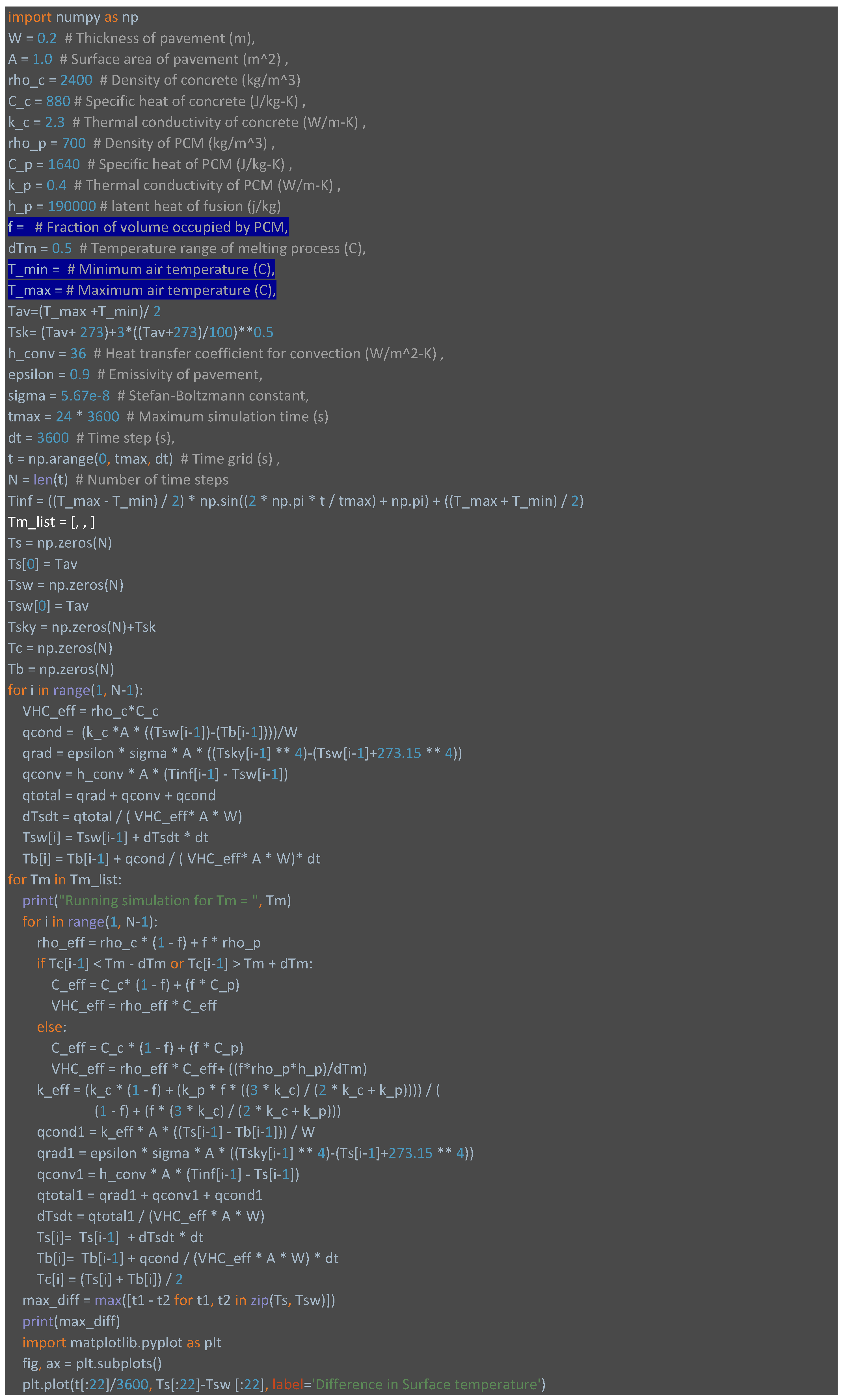

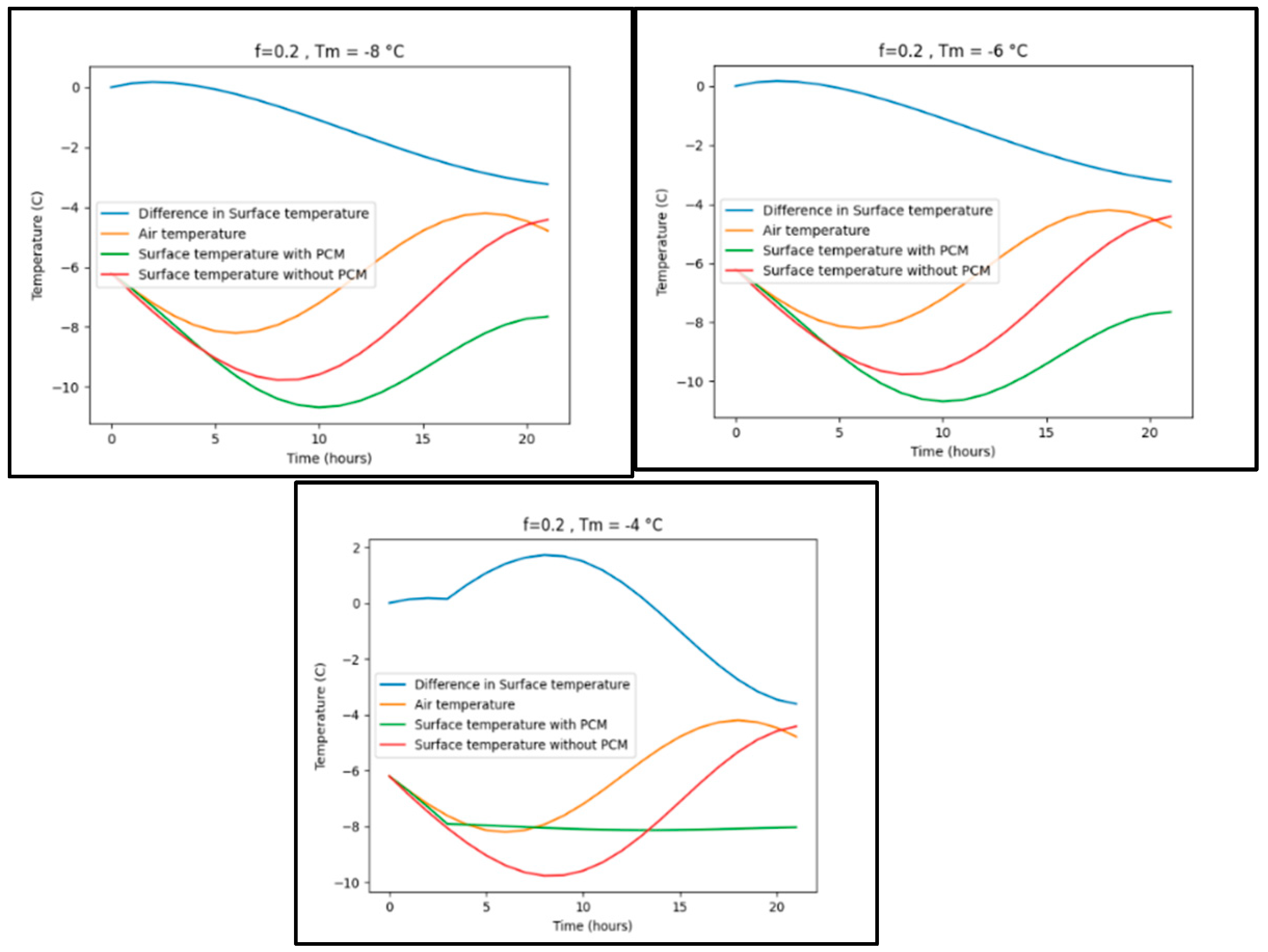

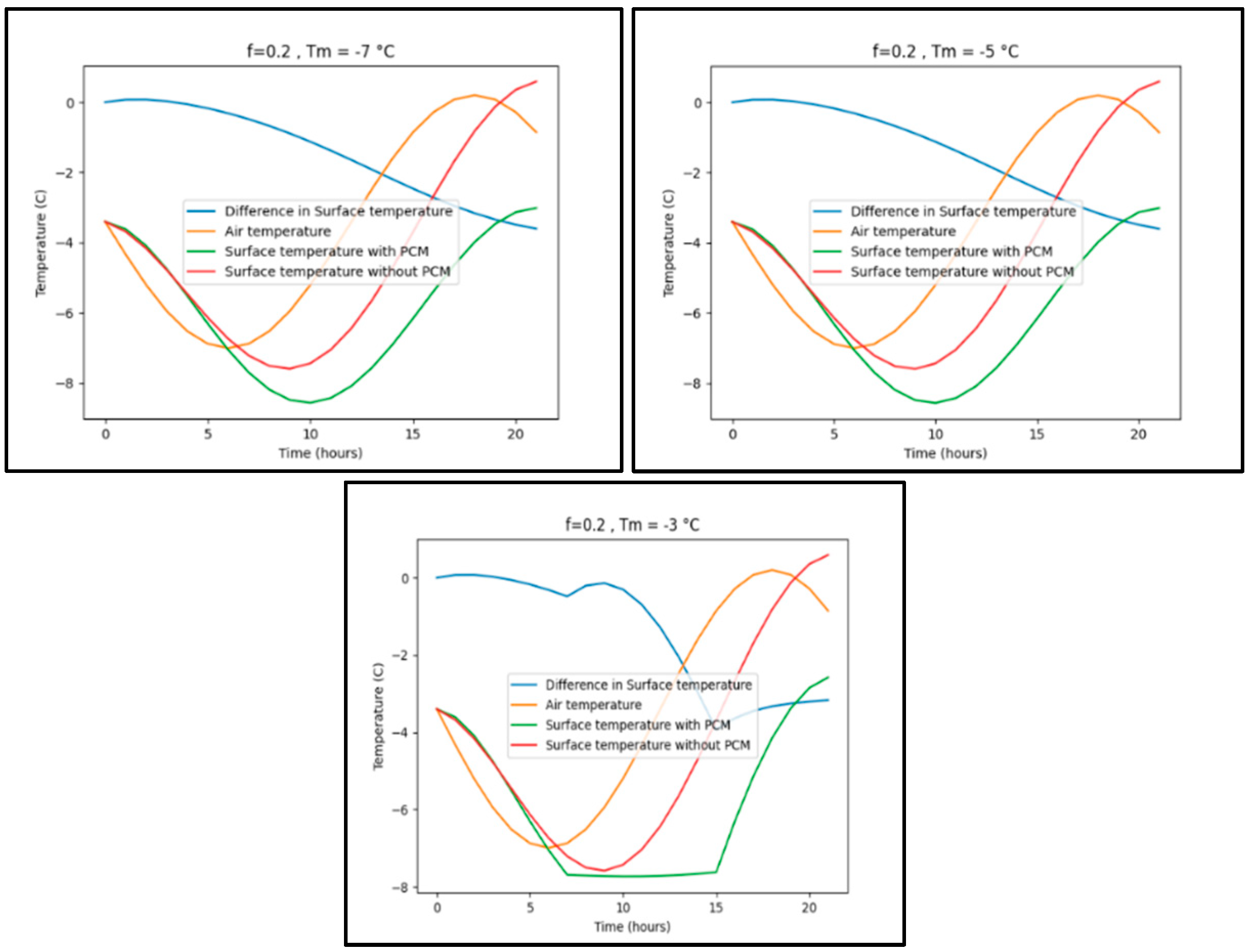

Appendix A.1. Python code

Appendix B Difference surface temperature for various phase changing temperature

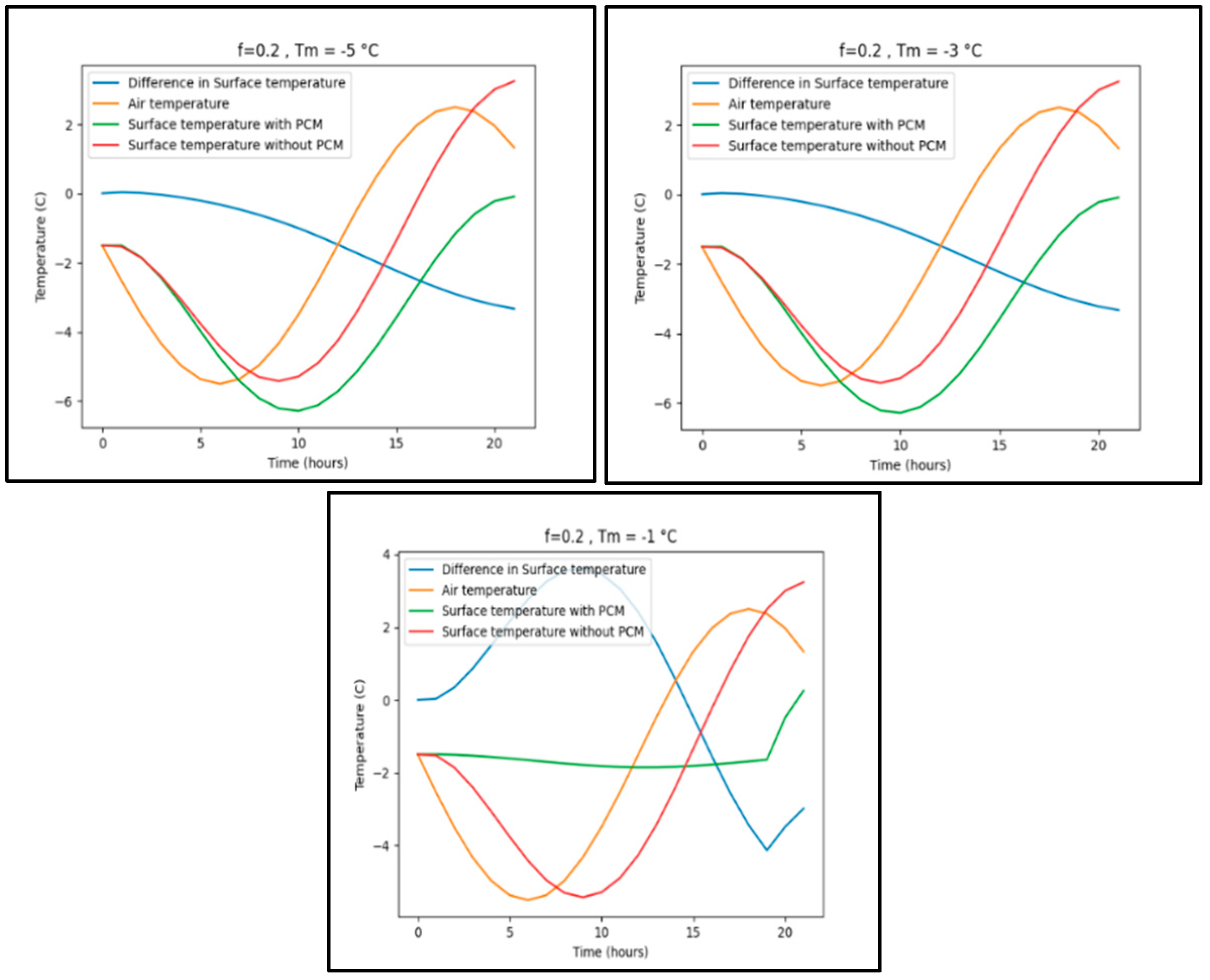

Appendix B.1. Trondheim

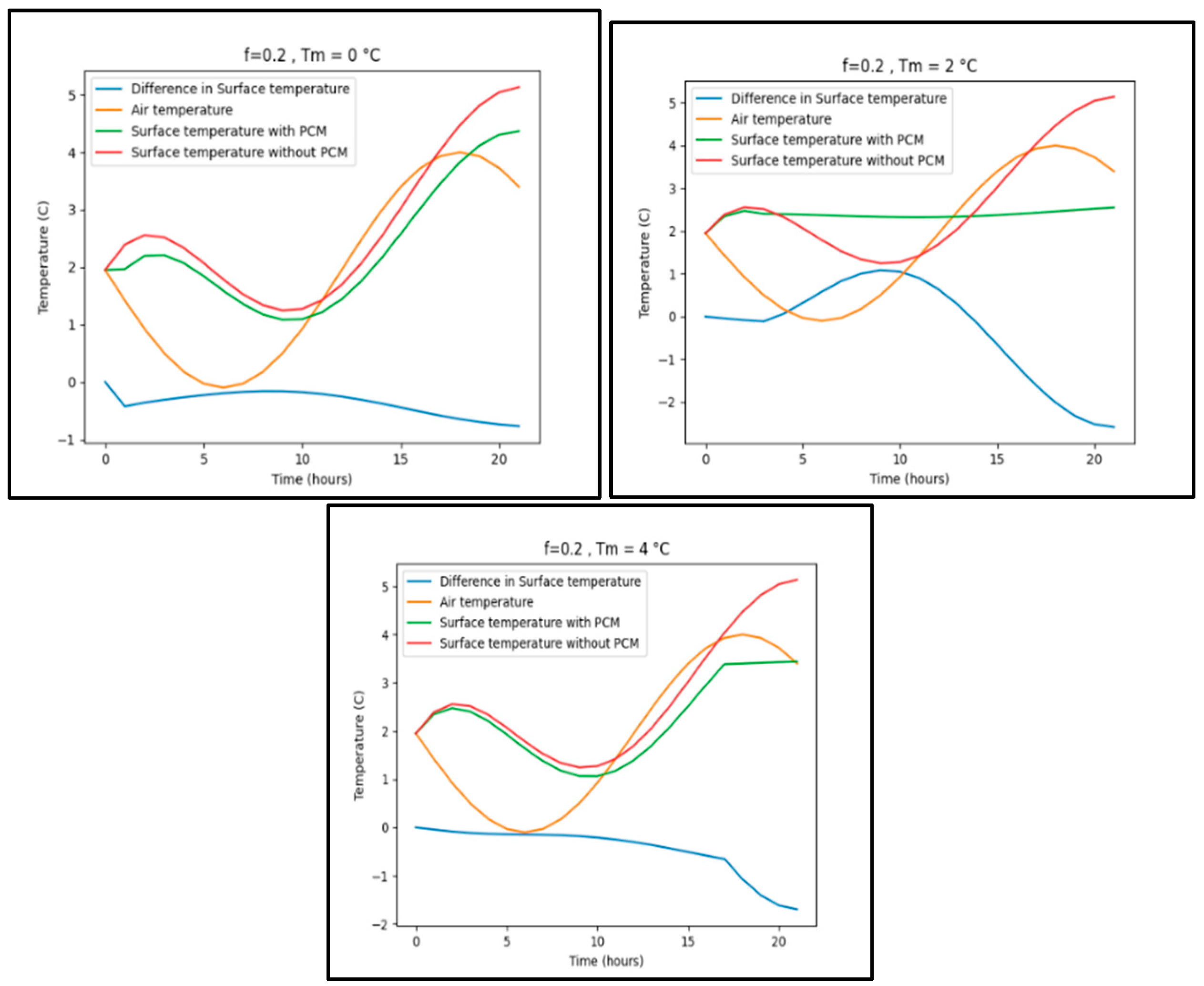

Appendix B.2. Beijing

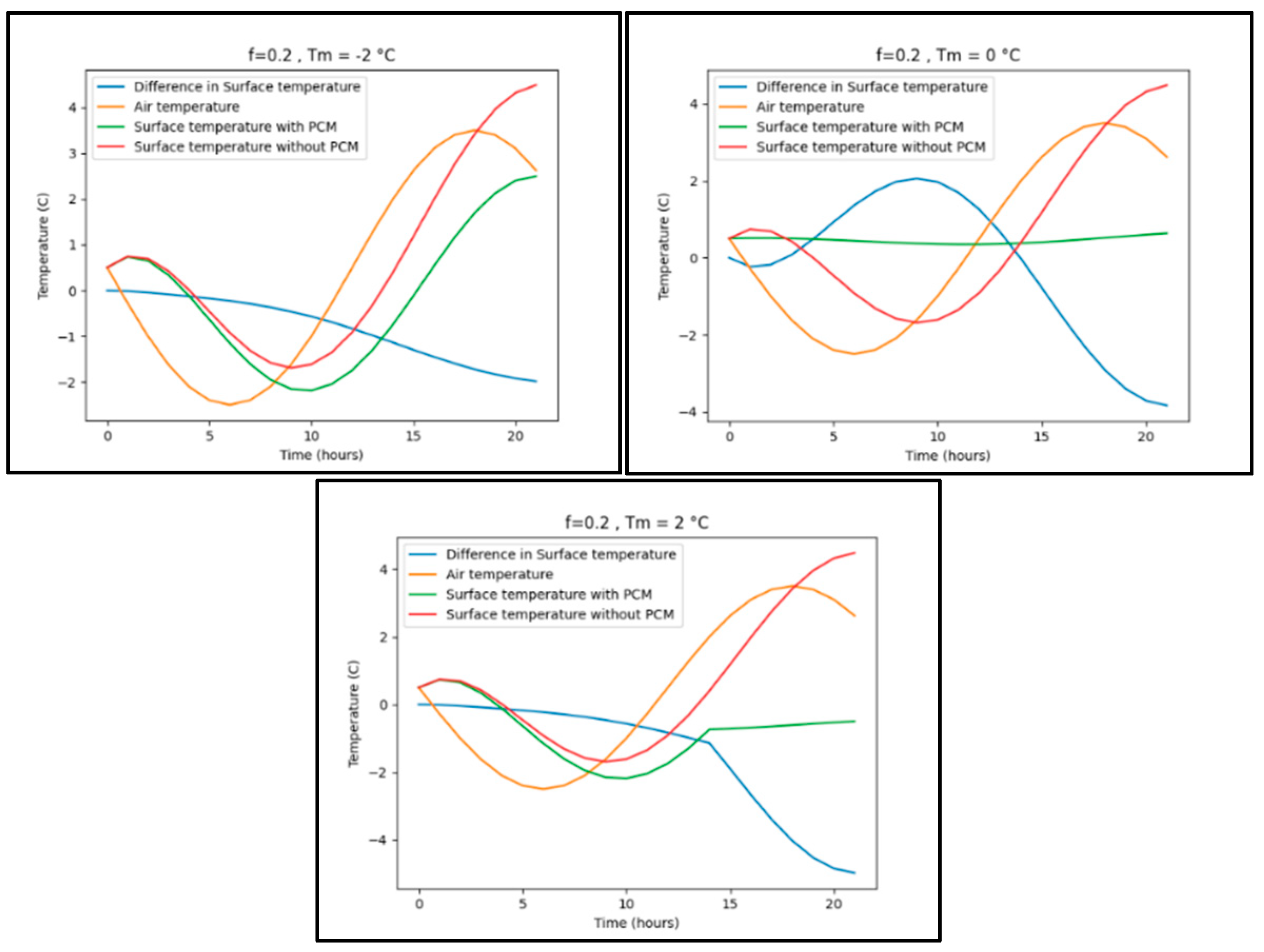

Appendix B.3. Zanjan

Appendix B.4. Berlin

Appendix B.5. New York

References

- Madhumathi, A., S. Subhashini, and J. VishnuPriya. The Urban Heat Island Effect its Causes and Mitigation with Reference to the Thermal Properties of Roof Coverings. in International Conference on Urban Sustainability: Emerging Trends, Themes, Concepts & Practices (ICUS). 2018.

- Akbari, H., S. Menon, and A. Rosenfeld, Global cooling: increasing world-wide urban albedos to offset CO 2. Climatic change, 2009. 94(3): p. 275-286. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X., Y. Yu, and F. Li, A review on thermoelectric energy harvesting from asphalt pavement: Configuration, performance and future. Construction and Building Materials, 2019. 228: p. 116818. [CrossRef]

- Mallick, R.B. and T. El-Korchi, Pavement engineering: principles and practice. 2013: CRC Press.

- Delatte, N.J., Concrete pavement design, construction, and performance. 2014: Crc Press.

- Mohod, M.V. and K. Kadam, A comparative study on rigid and flexible pavement: A review. IOSR Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering (IOSR-JMCE), 2016. 13(3): p. 84-88.

- Núñez, O., Composite Pavements: A Technical and Economic Analysis During the Pavement Type Selection Process. 2007, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

- Hashemi, M., et al., The effect of superplasticizer admixture on the engineering characteristics of roller-compacted concrete pavement. International Journal of Pavement Engineering, 2022. 23(7): p. 2432-2447. [CrossRef]

- Shafigh, P., et al., Laboratory comparison of roller-compacted concrete and ordinary vibrated concrete for pavement structures. Građevinar, 2020. 72(02.): p. 127-137.

- Asadi, I., et al., Frost-Salt Testing Non-Air Entrained High-Performance Fly-Ash Concrete: Relations Liquid Uptake-Internal Cracking–Scaling. Available at SSRN 4447555.

- Gao, Y., L. Huang, and H. Zhang, Study on anti-freezing functional design of phase change and temperature control composite bridge decks. Construction and Building Materials, 2016. 122: p. 714-720. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. and W. Hansen, Effect of hydrophobic surface treatment on freeze-thaw durability of concrete. Cement and Concrete Composites, 2016. 69: p. 49-60. [CrossRef]

- Valenza II, J.J. and G.W. Scherer, A review of salt scaling: II. Mechanisms. Cement and Concrete Research, 2007. 37(7): p. 1022-1034. [CrossRef]

- Farnam, Y., et al., The influence of calcium chloride deicing salt on phase changes and damage development in cementitious materials. Cement and Concrete Composites, 2015. 64: p. 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Farnam, Y., et al., Acoustic emission and low-temperature calorimetry study of freeze and thaw behavior in cementitious materials exposed to sodium chloride salt. Transportation Research Record, 2014. 2441(1): p. 81-90. [CrossRef]

- Arora, A., G. Sant, and N. Neithalath, Numerical simulations to quantify the influence of phase change materials (PCMs) on the early-and later-age thermal response of concrete pavements. Cement and Concrete Composites, 2017. 81: p. 11-24. [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M., Analyzing the heat island magnitude and characteristics in one hundred Asian and Australian cities and regions. Science of the Total Environment, 2015. 512: p. 582-598. [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M., Innovating to zero the building sector in Europe: Minimising the energy consumption, eradication of the energy poverty and mitigating the local climate change. Solar Energy, 2016. 128: p. 61-94. [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M. and G.Y. Yun, Recent development and research priorities on cool and super cool materials to mitigate urban heat island. Renewable Energy, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Shirani-Bidabadi, N., et al., Evaluating the spatial distribution and the intensity of urban heat island using remote sensing, case study of Isfahan city in Iran. Sustainable cities and society, 2019. 45: p. 686-692. [CrossRef]

- Taleghani, M., Outdoor thermal comfort by different heat mitigation strategies-A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2018. 81: p. 2011-2018. [CrossRef]

- Akbari, H., et al., Local climate change and urban heat island mitigation techniques–the state of the art. Journal of Civil Engineering and Management, 2016. 22(1): p. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Kyriakodis, G. and M. Santamouris, Using reflective pavements to mitigate urban heat island in warm climates-Results from a large scale urban mitigation project. Urban Climate, 2018. 24: p. 326-339. [CrossRef]

- Akbari, H. and L.S. Rose, Urban surfaces and heat island mitigation potentials. Journal of the Human-environment System, 2008. 11(2): p. 85-101. [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M., et al., Passive and active cooling for the outdoor built environment–Analysis and assessment of the cooling potential of mitigation technologies using performance data from 220 large scale projects. Solar Energy, 2017. 154: p. 14-33. [CrossRef]

- Al-Humairi, S., et al. Sustainable pavement: A review on the usage of pavement as a mitigation strategy for UHI. in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2021. IOP Publishing. M: Conference Series, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., et al., Characterizing thermal impacts of pavement materials on urban heat island (UHI) effect. DEStech Transactions on Engineering and Technology Research, 2016(ictim). [CrossRef]

- Nwakaire, C.M., et al., Urban Heat Island Studies with Emphasis on Urban Pavements; a review. Sustainable Cities and Society, 2020: p. 102476. [CrossRef]

- Anupam, B., U.C. Sahoo, and P. Rath, Phase change materials for pavement applications: A review. Construction and Building Materials, 2020. 247: p. 118553. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., et al., Effect of pavement thermal properties on mitigating urban heat islands: A multi-scale modeling case study in Phoenix. Building and Environment, 2016. 108: p. 110-121. [CrossRef]

- Fahed, J., et al., Impact of urban heat island mitigation measures on microclimate and pedestrian comfort in a dense urban district of Lebanon. Sustainable Cities and Society, 2020. 61: p. 102375. [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, L.F., et al., Materials used as PCM in thermal energy storage in buildings: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2011. 15(3): p. 1675-1695. [CrossRef]

- Kuznik, F., et al., A review on phase change materials integrated in building walls. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2011. 15(1): p. 379-391. [CrossRef]

- Ma, B., et al., Thermal-Insulation Effect and Evaluation Indices of Asphalt Mixture Mixed with Phase-Change Materials. Materials, 2020. 13(17): p. 3738. [CrossRef]

- Kakar, M.R., et al., Investigating bitumen’s direct interaction with Tetradecane as potential phase change material for low temperature applications. Road Materials and Pavement Design, 2020. 21(8): p. 2356-2363. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., et al., Antiaging Property and Mechanism of Phase-Change Asphalt with PEG as an Additive. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, 2020. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., et al., Preparation and characterization of temperature-adjusting asphalt with diatomite-supported PEG as an additive. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 2020. 32(3): p. 04020019. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., et al. Preparation and Characterization of Polyurethane Shell Microencapsulated Phase Change Materials by Interfacial Polymerization. in 2020 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Electromechanical Automation (AIEA). 2020. IEEE.

- Ma, B., et al., Preparation and Investigation of NiTi Alloy Phase-Change Heat Storage Asphalt Mixture. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 2020. 32(9): p. 04020250. [CrossRef]

- Tahami, A., M. Gholikhani, and S. Dessouky. A Novel Thermoelectric Approach to Energy Harvesting from Road Pavement. in International Conference on Transportation and Development 2020. 2020. American Society of Civil Engineers Reston, VA. 2020.

- Jia, M., et al., Laboratory evaluation of poly (ethylene glycol) for cooling of asphalt pavements. Construction and Building Materials, 2021. 273: p. 121774. [CrossRef]

- Ma, B., et al., Study on the temperature control effects of an epoxy resin composite thermoregulation agent on asphalt mixtures. Construction and Building Materials, 2020. 257: p. 119580. [CrossRef]

- Yinfei, D., et al., Effect of lightweight aggregate gradation on latent heat storage capacity of asphalt mixture for cooling asphalt pavement. Construction and Building Materials, 2020. 250: p. 118849. [CrossRef]

- Si, W., et al., Temperature responses of asphalt pavement structure constructed with phase change material by applying finite element method. Construction and Building Materials, 2020. 244: p. 118088. [CrossRef]

- Ma, B., et al., The thermoregulation effect of microencapsulated phase-change materials in an asphalt mixture. Construction and Building Materials, 2020. 231: p. 117186. [CrossRef]

- She, Z., et al., Examining the effects of microencapsulated phase change materials on early-age temperature evolutions in realistic pavement geometries. Cement and Concrete Composites, 2019. 103: p. 149-159. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., et al., Preparation and effectiveness of composite phase change material for performance improvement of Open Graded Friction Course. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2019. 214: p. 259-269. [CrossRef]

- Ma, B., et al., Analysis of thermoregulation indices on microencapsulated phase change materials for asphalt pavement. Construction and Building Materials, 2019. 208: p. 402-412. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., et al., Thermal and rheological performance of asphalt binders modified with expanded graphite/polyethylene glycol composite phase change material (EP-CPCM). Construction and Building Materials, 2019. 194: p. 83-91. [CrossRef]

- Tahami, S.A., et al., Developing a new thermoelectric approach for energy harvesting from asphalt pavements. Applied energy, 2019. 238: p. 786-795. [CrossRef]

- Bueno, M., et al., Modification of asphalt mixtures for cold regions using microencapsulated phase change materials. Scientific reports, 2019. 9(1): p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y., et al., Laboratory investigation of phase change effect of polyethylene glycolon on asphalt binder and mixture performance. Construction and Building Materials, 2019. 212: p. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Kakar, M.R., et al., Thermal and rheological characterization of bitumen modified with microencapsulated phase change materials. Construction and Building Materials, 2019. 215: p. 171-179. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.-x., et al., Thermoregulation effect analysis of microencapsulated phase change thermoregulation agent for asphalt pavement. Construction and Building Materials, 2019. 221: p. 139-150. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J., et al., Preparation and thermal performance of binary fatty acid with diatomite as form-stable composite phase change material for cooling asphalt pavements. Construction and Building Materials, 2019. 226: p. 616-624. [CrossRef]

- Wei, K., et al., Influence of NiTi alloy phase change heat-storage particles on thermophysical parameters, phase change heat-storage thermoregulation effect, and pavement performance of asphalt mixture. Renewable Energy, 2019. 141: p. 431-443. [CrossRef]

- Kakar, M.R., et al., Effects of aging on asphalt binders modified with microencapsulated phase change material. Composites Part B: Engineering, 2019. 173: p. 107007. [CrossRef]

- Wei, K., et al., Study on rheological properties and phase-change temperature control of asphalt modified by polyurethane solid–solid phase change material. Solar Energy, 2019. 194: p. 893-902. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., et al., Mechanical and thermal performance of macro-encapsulated phase change materials for pavement application. Materials, 2018. 11(8): p. 1398. [CrossRef]

- Li, F., et al., Low-temperature organic phase change material microcapsules for asphalt pavement: preparation, characterisation and application. Journal of microencapsulation, 2018. 35(7-8): p. 635-642. [CrossRef]

- Li, F., et al., Preparation of low-temperature phase change materials microcapsules and its application to asphalt pavement. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 2018. 30(11): p. 04018303. [CrossRef]

- Refaa, Z., et al., Numerical study on the effect of phase change materials on heat transfer in asphalt concrete. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 2018. 133: p. 140-150. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J., et al., Preparation and thermal properties of encapsulated ceramsite-supported phase change materials used in asphalt pavements. Construction and Building Materials, 2018. 190: p. 235-245. [CrossRef]

- Si, W., et al., Temperature responses of asphalt mixture physical and finite element models constructed with phase change material. Construction and Building Materials, 2018. 178: p. 529-541. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., et al., Preparation of expanded graphite/polyethylene glycol composite phase change material for thermoregulation of asphalt binder. Construction and Building Materials, 2018. 169: p. 513-521. [CrossRef]

- Athukorallage, B., et al., Performance analysis of incorporating phase change materials in asphalt concrete pavements. Construction and building materials, 2018. 164: p. 419-432. [CrossRef]

- Bai, G., Q. Fan, and X.-M. Song, Preparation and characterization of pavement materials with phase-change temperature modulation. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 2019. 136(6): p. 2327-2331. [CrossRef]

- Ryms, M., H. Denda, and P. Jaskuła, Thermal stabilization and permanent deformation resistance of LWA/PCM-modified asphalt road surfaces. Construction and Building Materials, 2017. 142: p. 328-341. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J., et al., Preparation and thermal properties of mineral-supported polyethylene glycol as form-stable composite phase change materials (CPCMs) used in asphalt pavements. Scientific reports, 2017. 7(1): p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Ma, B., et al., Determination of specific heat capacity on composite shape-stabilized phase change materials and asphalt mixtures by heat exchange system. Materials, 2016. 9(5): p. 389. [CrossRef]

- Asadi, I., et al., Phase change materials incorporated into geopolymer concrete for enhancing energy efficiency and sustainability of buildings: a review. Case Studies in Construction Materials, 2022. 17: p. e01162. [CrossRef]

- Cengel, Y.A., A.J. Ghajar, and H. Ma, Heat and Mass Transfer: Fundamentals & Applications, 4e. 2011: McGraw-Hill.

- Lilley, D., et al., Phase change materials for thermal energy storage: A perspective on linking phonon physics to performance. Journal of Applied Physics, 2021. 130(22): p. 220903. [CrossRef]

- Shafigh, P., I. Asadi, and N.B. Mahyuddin, Concrete as a thermal mass material for building applications-A review. Journal of Building Engineering, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk, R., et al., A state of the art review on sensible and latent heat thermal energy storage processes in porous media: Mesoscopic Simulation. Applied Sciences, 2022. 12(14): p. 6995. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., et al., Description of phase change materials (PCMs) used in buildings under various climates: A review. Journal of Energy Storage, 2022. 56: p. 105760. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., et al., Development of thermal energy storage concrete. Cement and concrete research, 2004. 34(6): p. 927-934. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T., Latent and sensible heat storage in concrete blocks. 1998, Concordia University.

- Xu, B. and Z. Li, Paraffin/diatomite composite phase change material incorporated cement-based composite for thermal energy storage. Applied Energy, 2013. 105: p. 229-237. [CrossRef]

- Entrop, A., H. Brouwers, and A. Reinders, Experimental research on the use of micro-encapsulated phase change materials to store solar energy in concrete floors and to save energy in Dutch houses. Solar Energy, 2011. 85(5): p. 1007-1020. [CrossRef]

- Sá, A.V., et al., Thermal enhancement of plastering mortars with phase change materials: experimental and numerical approach. Energy and Buildings, 2012. 49: p. 16-27. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, N.P. and A. Sakulich, Application of phase change materials to improve the thermal performance of cementitious material. Energy and Buildings, 2015. 103: p. 83-95. [CrossRef]

- Eddhahak, A., et al., Effect of phase change materials on the hydration reaction and kinetic of PCM-mortars. Journal of thermal analysis and calorimetry, 2014. 117(2): p. 537-545. [CrossRef]

- Hajilar, S. and B. Shafei, Nano-scale investigation of elastic properties of hydrated cement paste constituents using molecular dynamics simulations. Computational Materials Science, 2015. 101: p. 216-226. [CrossRef]

- Adesina, A., et al., Phase change materials in concrete: An overview of properties. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2020. 27: p. 391-395. [CrossRef]

- Adesina, A., Use of phase change materials in concrete: current challenges. Renewable Energy and Environmental Sustainability, 2019. 4: p. 9. [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.-D., et al., Thermal and mechanical behaviors of concrete with incorporation of strontium-based phase change material (PCM). International Journal of Concrete Structures and Materials, 2019. 13(1): p. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Šavija, B., Smart crack control in concrete through use of phase change materials (PCMs): a review. Materials, 2018. 11(5): p. 654.

- Sharma, B., Incorporation of Phase Change Materials into Cementitious Systems. 2013, Arizona State University Phoenix, AZ, USA.

- Tyagi, V., et al., Thermodynamics and performance evaluation of encapsulated PCM-based energy storage systems for heating application in building. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 2014. 115(1): p. 915-924. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z., et al., Preparation and thermal energy storage properties of paraffin/calcined diatomite composites as form-stable phase change materials. Thermochimica Acta, 2013. 558: p. 16-21. [CrossRef]

- Sakulich, A.R. and D.P. Bentz, Incorporation of phase change materials in cementitious systems via fine lightweight aggregate. Construction and Building Materials, 2012. 35: p. 483-490. [CrossRef]

- Bentz, D.P. and R. Turpin, Potential applications of phase change materials in concrete technology. Cement and Concrete Composites, 2007. 29(7): p. 527-532. [CrossRef]

- Farnam, Y., et al., Incorporating phase change materials in concrete pavement to melt snow and ice. Cement and concrete composites, 2017. 84: p. 134-145. [CrossRef]

- Farnam, Y., et al., Evaluating the use of phase change materials in concrete pavement to melt ice and snow. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 2016. 28(4): p. 04015161. [CrossRef]

- Yeon, J.H. and K.-K. Kim, Potential applications of phase change materials to mitigate freeze-thaw deteriorations in concrete pavement. Construction and Building Materials, 2018. 177: p. 202-209. [CrossRef]

- Urgessa, G., et al., Thermal responses of concrete slabs containing microencapsulated low-transition temperature phase change materials exposed to realistic climate conditions. Cement and Concrete Composites, 2019. 104: p. 103391. [CrossRef]

- Li, W., et al., Evaluation of the potential use of form-stable phase change materials to improve the freeze-thaw resistance of concrete. Construction and Building Materials, 2019. 203: p. 621-632. [CrossRef]

- Yeon, J.H., Thermal behavior of cement mortar embedded with low-phase transition temperature PCM. Construction and Building Materials, 2020. 252: p. 119168. [CrossRef]

- Veeraragavan, R.K., A. Sakulich, and R.B. Mallick, An Evaluation of Cool Pavement Strategies on Concrete Pavements, in Airfield and Highway Pavements 2017. 2017. p. 20-32.

- Young, B.A., et al., Early-age temperature evolutions in concrete pavements containing microencapsulated phase change materials. Construction and Building Materials, 2017. 147: p. 466-477. [CrossRef]

- Somani, P. and A. Gaur, Evaluation and reduction of temperature stresses in concrete pavement by using phase changing material. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2020. 32: p. 856-864. [CrossRef]

- BR, A., U.C. Sahoo, and P. Rath, Thermal and mechanical performance of phase change material incorporated concrete pavements. Road Materials and Pavement Design, 2021: p. 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, N.P., et al., Application of lightweight aggregate and rice husk ash to incorporate phase change materials into cementitious materials. Journal of Sustainable Cement-Based Materials, 2016. 5(6): p. 349-369. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, V., et al., Development of phase change materials based microencapsulated technology for buildings: a review. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews, 2011. 15(2): p. 1373-1391. [CrossRef]

- Jamekhorshid, A., S. Sadrameli, and M. Farid, A review of microencapsulation methods of phase change materials (PCMs) as a thermal energy storage (TES) medium. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2014. 31: p. 531-542. [CrossRef]

- Fang, G., Z. Chen, and H. Li, Synthesis and properties of microencapsulated paraffin composites with SiO2 shell as thermal energy storage materials. Chemical engineering journal, 2010. 163(1-2): p. 154-159. [CrossRef]

- Rathore, P.K.S., S.K. Shukla, and N.K. Gupta, Potential of microencapsulated PCM for energy savings in buildings: A critical review. Sustainable Cities and Society, 2020. 53: p. 101884. [CrossRef]

- Giro-Paloma, J., et al., Types, methods, techniques, and applications for microencapsulated phase change materials (MPCM): a review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2016. 53: p. 1059-1075. [CrossRef]

- Alva, G., et al., Synthesis, characterization and applications of microencapsulated phase change materials in thermal energy storage: A review. Energy and Buildings, 2017. 144: p. 276-294. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K., K.H. Kim, and J.K. Yang, Thermal analysis of hydration heat in concrete structures with pipe-cooling system. Computers & Structures, 2001. 79(2): p. 163-171. [CrossRef]

- Sakulich, A.R. and D.P. Bentz, Increasing the service life of bridge decks by incorporating phase-change materials to reduce freeze-thaw cycles. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 2012. 24(8): p. 1034-1042. [CrossRef]

- Meshgin, P. and Y. Xi, Effect of Phase-Change Materials on Properties of Concrete. ACI Materials Journal, 2012. 109(1).

- Asadi, I., et al., Thermophysical properties of sustainable cement mortar containing oil palm boiler clinker (OPBC) as a fine aggregate. Construction and Building Materials, 2021. 268: p. 121091. [CrossRef]

- Hunger, M., et al., The behavior of self-compacting concrete containing micro-encapsulated phase change materials. Cement and Concrete Composites, 2009. 31(10): p. 731-743. [CrossRef]

- Norvell, C., D.J. Sailor, and P. Dusicka, The effect of microencapsulated phase-change material on the compressive strength of structural concrete. Journal of Green Building, 2013. 8(3): p. 116-124. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z., et al., The durability of cementitious composites containing microencapsulated phase change materials. Cement and Concrete Composites, 2017. 81: p. 66-76. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Z.H. and H.S. Majdi, Study of heat of hydration of Portland cement used in Iraq. Case studies in construction materials, 2017. 7: p. 154-162. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H., et al., Development of building materials by using micro-encapsulated phase change material. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering, 2007. 24(2): p. 332-335. [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, C., et al., Effect of PCM on the hydration process of Cement-Based mixtures: A novel Thermo-Mechanical investigation. Materials, 2018. 11(6): p. 871. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F., et al., On the feasibility of using phase change materials (PCMs) to mitigate thermal cracking in cementitious materials. Cement and Concrete Composites, 2014. 51: p. 14-26. [CrossRef]

- Mihashi, H., et al., Development of a smart material to mitigate thermal stress in early age concrete. Control of cracking in early age concrete, 2002: p. 385-392.

- Choi, W.-C., et al., Feasibility of using phase change materials to control the heat of hydration in massive concrete structures. The Scientific World Journal, 2014. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ling, T.-C. and C.-S. Poon, Use of phase change materials for thermal energy storage in concrete: An overview. Construction and Building Materials, 2013. 46: p. 55-62. [CrossRef]

- Stoll, F., M.L. Drake, and I.O. Salyer, Use of phase change materials to prevent overnight freezing of bridge decks. 1996.

- Gartland, L.M., Heat islands: understanding and mitigating heat in urban areas. 2012: Routledge.

- Santamouris, M., et al., Passive cooling of the built environment–use of innovative reflective materials to fight heat islands and decrease cooling needs. International Journal of Low-Carbon Technologies, 2008. 3(2): p. 71-82. [CrossRef]

- Demirboğa, R. and R. Gül, The effects of expanded perlite aggregate, silica fume and fly ash on the thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete. Cement and concrete research, 2003. 33(5): p. 723-727. [CrossRef]

- Shafigh, P., et al., Thermal properties of cement mortar with different mix proportions. Materiales de Construcción, 2020. 70(339): p. 224. [CrossRef]

- Talebi, H.R., et al., Investigation of Thermal Properties of Normal Weight Concrete for Different Strength Classes. Journal of Environmental Treatment Techniques, 2020. 8(3): p. 908-914.

- Ferguson, B., et al., Reducing urban heat islands: compendium of strategies-cool pavements. 2008.

- Qin, Y., A review on the development of cool pavements to mitigate urban heat island effect. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews, 2015. 52: p. 445-459. [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.C., Characterization Methodologies of Thermal Management Materials, in Advanced Materials for Thermal Management of Electronic Packaging. 2011, Springer. p. 59-129.

- Zhang, W., et al., Mesoscale model for thermal conductivity of concrete. Construction and Building Materials, 2015. 98: p. 8-16. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, N.P., G.E. Freeman, and A.R. Sakulich, Using COMSOL modeling to investigate the efficiency of PCMs at modifying temperature changes in cementitious materials–case study. Construction and Building Materials, 2015. 101: p. 965-974. [CrossRef]

- Karlessi, T., et al., Development and testing of PCM doped cool colored coatings to mitigate urban heat island and cool buildings. Building and environment, 2011. 46(3): p. 570-576. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, N.P. and K.C. Mahboub, Application of a PCM-rich concrete overlay to control thermal induced curling stresses in concrete pavements. Construction and Building Materials, 2018. 183: p. 502-512. [CrossRef]

- Baetens, R., B.P. Jelle, and A. Gustavsen, Phase change materials for building applications: A state-of-the-art review. Energy and buildings, 2010. 42(9): p. 1361-1368. [CrossRef]

- Farnam, Y., et al., Evaluating the use of phase change materials in concrete pavement to melt ice and snow. J. Mater. Civ. Eng, 2015. 28(4): p. 04015161. [CrossRef]

- Bentz, D.P., A computer model to predict the surface temperature and time-of-wetness of concrete pavements and bridge decks. 2000.

- Mayercsik, N.P., M. Vandamme, and K.E. Kurtis, Assessing the efficiency of entrained air voids for freeze-thaw durability through modeling. Cement and Concrete research, 2016. 88: p. 43-59. [CrossRef]

- Polat, R., The effect of antifreeze additives on fresh concrete subjected to freezing and thawing cycles. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 2016. 127: p. 10-17. [CrossRef]

- Cai, L., H. Wang, and Y. Fu, Freeze–thaw resistance of alkali–slag concrete based on response surface methodology. Construction and Building Materials, 2013. 49: p. 70-76.

- Mechtcherine, V., et al., Effect of superabsorbent polymers (SAP) on the freeze–thaw resistance of concrete: results of a RILEM interlaboratory study. Materials and Structures, 2017. 50(1): p. 1-19.

- Santamouris, M., Using cool pavements as a mitigation strategy to fight urban heat island—A review of the actual developments. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2013. 26: p. 224-240. [CrossRef]

- Ma, B., et al., Exploration of road temperature-adjustment material in asphalt mixture. Road Materials and Pavement Design, 2014. 15(3): p. 659-673. [CrossRef]

- Liston, L., et al., Toward the use of phase change materials (PCM) in concrete pavements: Evaluation of thermal properties of PCM. 2014.

- Yuan, X., et al., Study on the Frost Resistance of Concrete Modified with Steel Balls Containing Phase Change Material (PCM). Materials, 2021. 14(16): p. 4497. [CrossRef]

- Hagentoft, C.-E., Introduction to building physics. 2001: External organization.

- Nayak, S., N.A. Krishnan, and S. Das, Microstructure-guided numerical simulation to evaluate the influence of phase change materials (PCMs) on the freeze-thaw response of concrete pavements. Construction and Building Materials, 2019. 201: p. 246-256. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., G.A. Lyngdoh, and S. Das, Influence of microencapsulated phase change materials (PCMs) on the chloride ion diffusivity of concretes exposed to Freeze-thaw cycles: Insights from multiscale numerical simulations. Construction and Building Materials, 2019. 212: p. 317-328. [CrossRef]

- Haurie, L., et al., Single layer mortars with microencapsulated PCM: Study of physical and thermal properties, and fire behaviour. Energy and Buildings, 2016. 111: p. 393-400. [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.K., M.K. Das, and P. Rath, Application of TCE-PCM based heat sinks for cooling of electronic components: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2016. 59: p. 550-582. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, A., et al., Mechanical and thermal characterization of concrete with incorporation of microencapsulated PCM for applications in thermally activated slabs. Construction and Building Materials, 2016. 112: p. 639-647. [CrossRef]

- Eddhahak-Ouni, A., et al., Experimental and multi-scale analysis of the thermal properties of Portland cement concretes embedded with microencapsulated Phase Change Materials (PCMs). Applied Thermal Engineering, 2014. 64(1-2): p. 32-39.

- Liu, F., J. Wang, and X. Qian, Integrating phase change materials into concrete through microencapsulation using cenospheres. Cement and Concrete Composites, 2017. 80: p. 317-325. [CrossRef]

| Aim of using PCM in concrete pavement | PCM | Density (g/cm3) |

Latent heat (J/g) | Phase change temperature (°C) |

Method of Incorporation | Ref |

| Anti-freezing | Polyol | 0.82 | 240.5 | 4.53 | Pipe | [11] |

| Paraffin | 0.77 | 129.4 | 2.9 | Using LWA and embedded tube | [95] | |

| Methyl laurate | 0.87 | 160.4 | 1.9 | |||

| Paraffin oil (C14-C16) |

0.77 | 157.8 | 5.7 | Impregnation | [94] | |

| Pipe | ||||||

| Paraffin (C14-H13) |

0.75 | 224.5 | 4.5 | Microencapsulate | [96] | |

| paraffin | 0.88 (solid) 0.77 (liquid) |

200 | 1-3 | Impregnation | [59] | |

| paraffin | --- | 200-225 | 4.5 | Microencapsulate | [97] | |

| Methyl laurate | 0.87 | --- | 5.2 | Impregnation | [98] | |

| Paraffin (OP2E) | 0.77 | 205 | 1-3 | |||

| Paraffin (OP3E) | 0.77 | 250 | 3-5 | |||

| paraffin | 0.75 | 193 | 4.5 | Impregnation | [99] | |

| paraffin | 0.77 | 122 | 2-2.5 | |||

| paraffin | 0.78 | 171 | -0.5 | |||

| Reduce surface temperature | paraffin | --- | 150 | 28 | Impregnation | [100] |

| paraffin | 0.86 | 180 | 45 | Microencapsulate | [101] | |

| paraffin | 0.96 | 172 | 48-51 | Direct mixing | [102] | |

| paraffin | 0.96 (solid) 0.87 (liquid) |

171 | 34-35 | Impregnation | [103] | |

| paraffin | 0.90 (solid) 0.86 (liquid) |

199 | 43-44 |

| Ref | Aggregate | Fineness modulus |

Specific density | Water absorption capacity (%) |

PCM absorption capacity (%) |

Sieve size (mm) |

| [104] | Standard Sand | - | 2.61 | - | - | - |

| Expanded shale LWA | - | 1.5 | 17.5 | - | - | |

| [11] | River sand | 2.5 | - | - | - | - |

| Macadam | - | - | - | - | 5 -20 | |

| [95] | Expanded shale LWA | 2.94 | 1.5 | 32±0.50 (vacuum) |

18.8±0.50 (ambient) |

0-5 |

| [100] | LWA | - | 1.5 | 17.5 | 13.3 | - |

| [94] | Expanded shale LWA | 2.94 | 1.5 | 32±0.50 (vacuum) |

23.7±0.50 (ambient) |

- |

| [96] | Standard sand | 2.87 | 2.65 | 1.02 | - | - |

| [59] | LWA | - | - | - | 10 | 0-8 |

| [97] | Crushed rock | 6.5 | 2.69 | 0.57 | - | ASTMC33 |

| crushed sand | 2.74 | 2.58 | 1.53 | - | ||

| [46] | quartz sand | - | 2.65 | - | - | ASTM C778 |

| [98] | Expanded clay A | - | - | 25 | 6 | 2-5 |

| Expanded clay B | - | - | 10 | 9 | 0-5 | |

| Expanded perlite | - | - | 250 | 200 | 3-5 | |

| Broken expanded shale | - | - | 9 | - | 0-5 | |

| River sand | 3.45 | - | - | - | - | |

| [99] | Standard sand | 2.87 | 2.65 | 1.02 | ||

| LWA artificially manufactured by mixing fly ash with dirt spoil | 4.49 | 1.40 | 12 | - | 0-5 | |

| [102] | River sand | 2.67 | 2.62 | 1 | - | 0-5 |

| crushed natural stone (10mm) | 5.79 | 2.70 | 0.4 | - | 5-10 | |

| crushed natural stone (20 mm) |

7.02 | 2.70 | 0.41 | - | 10-20 |

| Location | Average air temperature at the 15th January (° C) | Surface Temperature difference (° C) Maximum (Ts with PCM-Ts without PCM) |

|||

| Min | Max | ||||

| Trondheim | -8.2 | -4.2 | f= 0.05 | Tm= -3 | 1.9 |

| f= 0.1 | 2.5 | ||||

| f=0.15 | 2.6 | ||||

| f= 0.2 | 2.8 | ||||

| Beijing | -7.0 | 0.2 | f= 0.05 | Tm= -2 | 2.8 |

| f= 0.1 | 3.3 | ||||

| f=0.15 | 3.5 | ||||

| f= 0.2 | 3.6 | ||||

| Zanjan | -5.5 | 2.5 | f= 0.05 | Tm= -0.5 | 2.9 |

| f= 0.1 | 3.3 | ||||

| f=0.15 | 3.5 | ||||

| f= 0.2 | 3.6 | ||||

| Berlin | -0.1 | 4.0 | f= 0.05 | Tm= 2 | 0.9 |

| f= 0.1 | 1.0 | ||||

| f=0.15 | 1.0 | ||||

| f= 0.2 | 1.0 | ||||

| New York | -2.5 | 3.5 | f= 0.05 | Tm= 0 | 1.7 |

| f= 0.1 | 1.9 | ||||

| f=0.15 | 2.0 | ||||

| f= 0.2 | 2.0 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).