1. Introduction

Valvular fibrosis is a histological hallmark of rheumatic heart disease, a terminal form of progressing and unresolved [

1]. Valvular interstitial cells (VIC) differentiation acts as the initial insult in fibrogenesis. Its differentiation into myofibroblast in response to profibrotic cytokines such as transforming growth factor- β 1 (TGF- β 1), potentiate its fibrosis properties [

2]. Cardiac myofibroblasts are characterized by expression of the contractile protein α-smooth muscle actin (α -SMA) [

3]. Therefore, preventing VIC differentiation into myofibroblasts could be a potential strategy in treating valvular fibrosis.

Transforming growth factor- β1 (TGF - β1) is a key pro-fibrotic cytokine in rheumatic heart disease [

4]. It can stimulate the proliferation of non-cystic fibrosis (CFs) and the differentiation of CFs into myofibroblasts, marked by the expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and the secretion of ECM proteins, such as collagen I and collagen III [

5,

6,

7]. The primary TGF- β1 signaling mechanism is the highly conserved small-mothers-against-decapentaplegic (Smad) pathway [

8]. Smads are divided into the following three major groups: 1) receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads: Smad2 and Smad3), 2) common mediator Smad (co-Smad: Smad4), and 3) inhibitory Smads (I-Smads: Smad6 and Smad7) [

9]. Activation of TGF- receptors and R-Smad proteins through phosphorylation results in formation of R-Smad-coSmad complex. Upon translocation to the nucleus, interacts with other transcription factors, and regulates target gene expression [

10]. Smad7 overexpression has been found to impede TGF- β1-induced signal transduction [

11,

12], whereas Smad2/3 activation has been demonstrated to be a critical mediator of TGF- β1-induced myofibroblast differentiation [

13,

14].

TGF1 can also trigger non-canonical signaling cascades such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways including extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), p38 MAPK, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) [

15]. A growing body of evidence suggests that MAPK signaling is vital in ECM production and VIC proliferation [

16,

17]. As a result, pharmacological treatments in these signaling pathways could be considered a promising therapeutic option for cardiac fibrosis [

6]. Therefore, in the present study, we tested the hypotheses that: TGF- β1-induced VIC differentiation based on αSMA expression was significantly reduced by atorvastatin, olmesartan, resveratrol, and its combination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

All animal procedures were in line with the ARRIVE guidelines [

18] and carried out in accordance with the laws, regulations, and administrative provisions of the U.K. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986 and associated guidelines, EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments, and the Law of Republic Indonesia Number 18 Year 2009 and Chapter 66 Law of Republic Indonesia Number 18 Year 2009 regarding the protection of animals for experimental and other scientific purposes. This research is approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experiments (Protocol Number: No.76/EC/KEPK/FKUA, date of approval 8 April 2021).

2.2. Animals

All experiments were carried out in accordance with the Animal Experimentation Guidelines of Sankyo Co., Twelve-week-old

Oryctolagus cuniculus rabbit were purchased from Stem cell laboratories (Surabaya, Indonesia), and maintained in a room under a temperature controlled at 23 C and a 12-h light–dark lighting cycle. The animals were allowed a standard pellet chow and water ad libitum [

19].

2.3. Material

Low-glucose DMEM, fetal bovine serum (FBS), Trypsin and HBSS were from Gibco Pasadena, CA (USA). Qiliqiangxin extracts were provided by Shijiazhuang Yiling Pharmaceutical Co., Shijiazhuang Ltd (China); Olmesartan (OLM) was purchased from Shanghai Sankyo Pharmaceutical Co., Shanghai Ltd. (China); Ang II was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, Missouri LLC. (USA); Rabbit anti-rat aSMA polyclonal antibody was from Bioworld Technology, Nanjing Inc. (China); Rabbit anti-rat TGF- β1 polyclonal antibody was from Santa Cruz Dallas, Texas (USA).

2.4. Valvular Interstitial Cell Isolation and Treatment

Valvular interstitial cell were isolated, as described by Lin et al [

20]. In summary, rabbit's valvular tissue was resected, chopped, and immersed in 0.08 percent trypsin. Following 4 or 5 rounds of digestion, the isolated cells were collected, centrifuged, and resuspended in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM)/F12 containing 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin in a humidified incubator with 5 percent CO2 and 95% air. Nonadherent cells and debris were aspirated, and fresh medium was added. This differential plating method produced pure cultures of first passage valvular interstitial cells. When the cells were virtually confluent, they were trypsin zed with 0.125 % trypsin and passaged. Valvular interstitial cell isolation was confirmed by positive expression of vimentin and negative for α SMA in immunoassays [

21]. After the cells were 80–90% confluent, the medium was replaced by serum-free DMEM the day before pre-treated with atorvastatin (effective intervention dose, 0.5 mg/ml), olmesartan (100 nanomol/l) for 30 min, resveratrol (50 μM/L) and exposed to TGF β1 (100 nM) for 24 hrs [

22]. Valvular interstitial cell in the second and third passages were used in this study.

2.5. Immunofluorescence quantification and analyses

PBS was used to wash the cells in the treatment groups before they were fixed with 4 percent paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1 percent Triton X-100. After 30 minutes of incubation with BSA, the cells were treated with the primary antibody specific for SMA overnight at 4°C. The cells were then treated for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark with Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) secondary antibody, followed by 30 minutes with DAPI. The cells were observed using a fluorescent microscope. The fluorescence intensity of cells was analyzed and quantified using a particular measurement included into imaging software. The intensity of fluorescence could be compared between sections of the same set of stress fibers and between cells of various treatments. The mean fluorescence intensities from ten randomly selected locations, each having a standard 50-lm

2 circular region, were used to analyze the data [

23].

2.6. Power and sample size calculation

We used a resource equation model with G*Power to determine the statistical power of a test of the null hypothesis that the population mean is indefinite, and we use a triplication and set alpha error to 0.05 for an ANOVA test.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All data were presented as means ± SEM (Standard Error of the Mean). The statistical significance was assessed by using one-way ANOVA for multiple-group comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of TGF- β1 -Induced Differentiation of VIC to Myofibroblasts

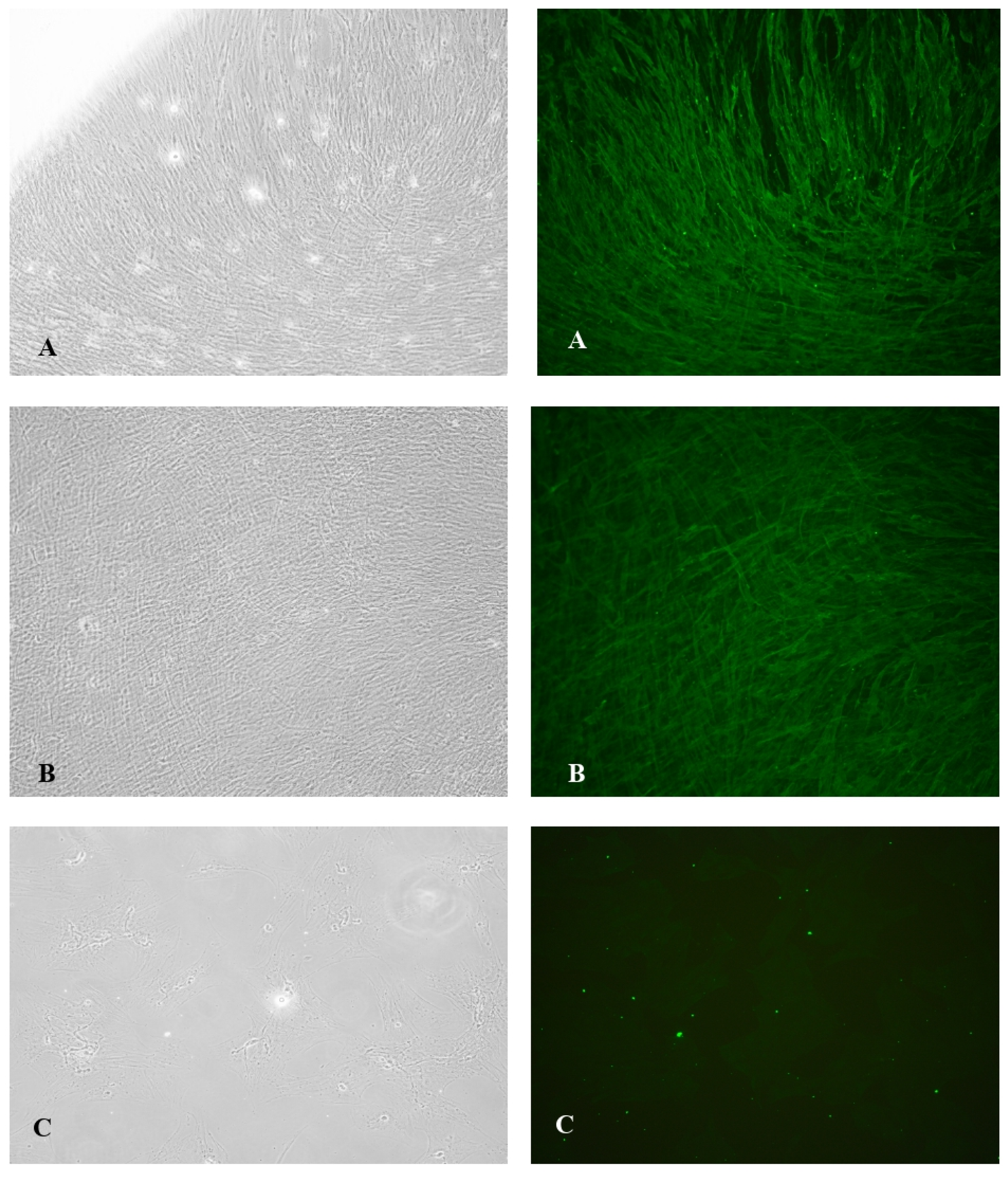

Immunochemical staining of control TGF-β1 induced VIC demonstrated that 80% of the cells were α-SMA positive with well-organized α-SMA filaments in its cytoplasm (

Figure 1A), exhibiting nearly complete differentiation of VIC to myofibroblasts with mean expression of αSMA24522.64 ± 4566.994 (

Figure 1).

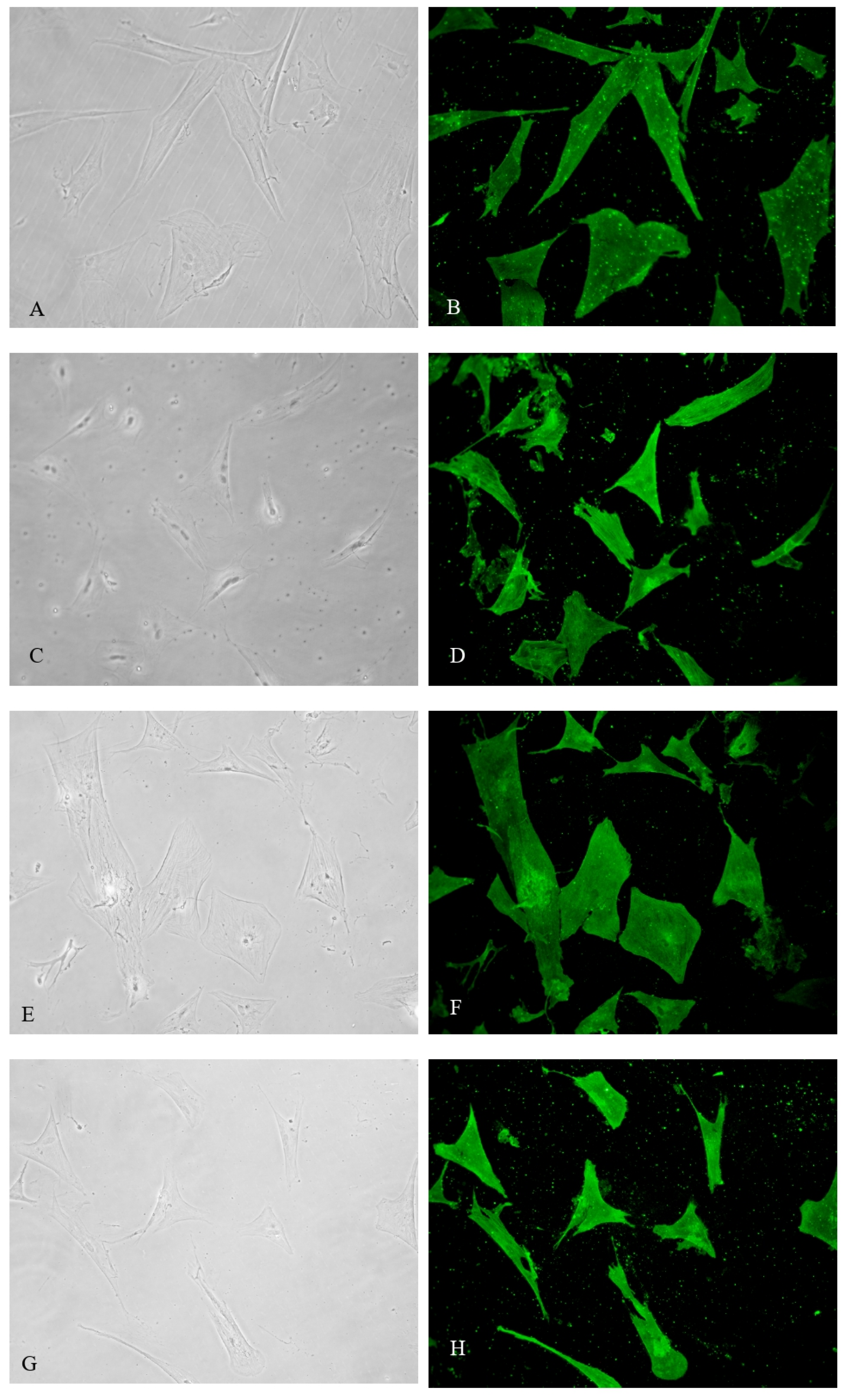

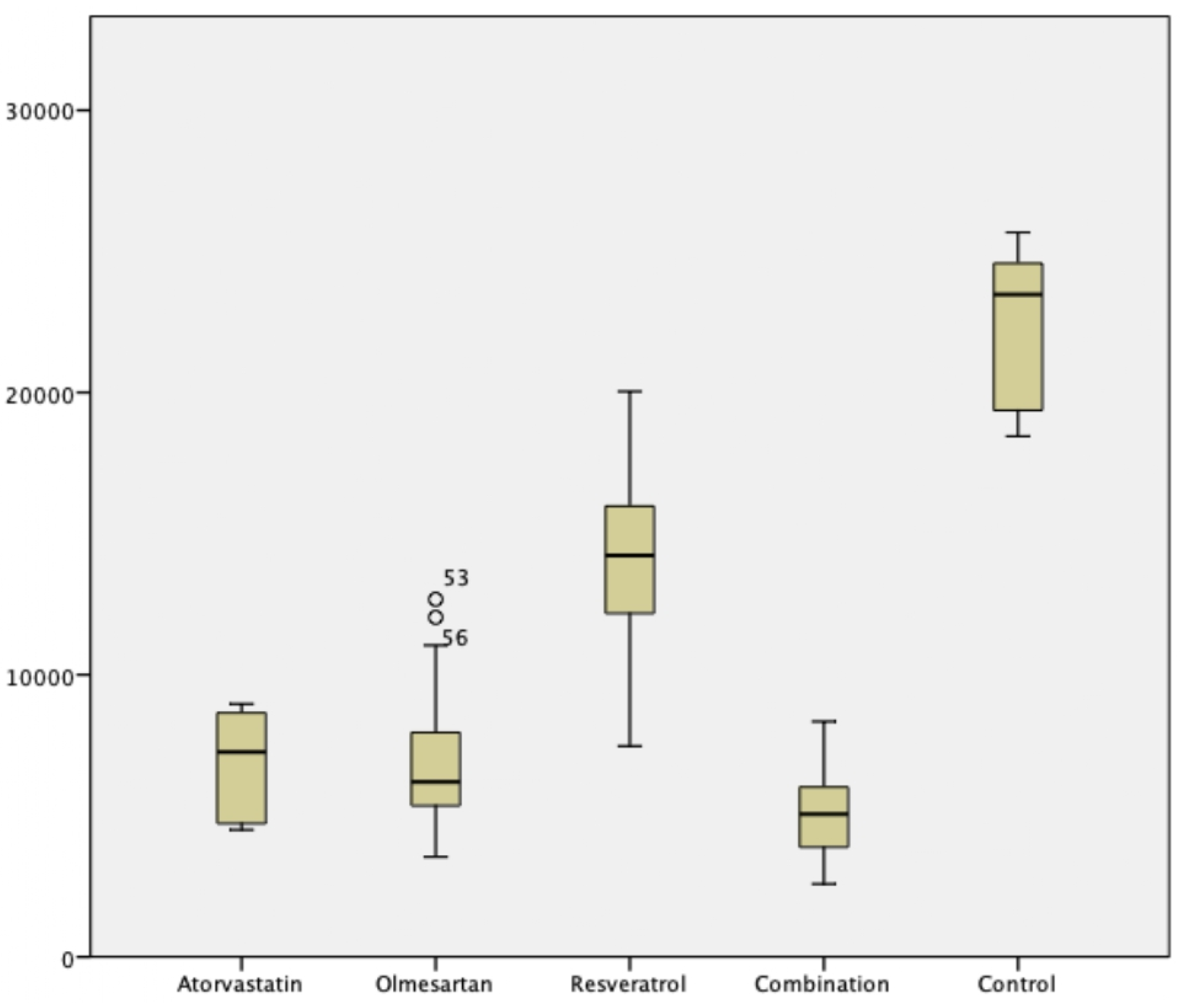

3.2. Effect of Atorvastatin, Olmesartan, Resveratrol, and Its Combination in Myofibroblast Differentiation inhibition

In comparison to control TGF- β1 -Induced VIC, atorvastatin, olmesartan, resveratrol, and its combination significantly reduced α-SMA expression compared to control. These intervention groups contain only a few of α-SMA expression, with mean expression of atorvastatin, olmesartan, resveratrol, and combination groups were 6823 ± 1735.3, 6942.7 ± 2455.9, 14176.2 ± 3343.3, 5051.8 ± 1612.2 respectively (

p < .0001). Combination of atorvastatin-olmesartan-resveratrol exhibit the most potent myofibroblast differentiation inhibition (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Post hoc analysis using Mann-Whitney test, showed no difference between atorvastatin and olmesartan groups despite its significancy.

4. Discussion

The major finding of this study was that (i) Atorvastatin inhibited TGF- β1 induced valvular interstitial cell differentiation (ii) Olmesartan inhibited TGF- β1 induced valvular interstitial cell differentiation (iii) Resveratrol inhibited TGF- β1 induced valvular interstitial cell differentiation and (iv) Combination of atorvastatin, olmesartan, and resveratrol inhibited TGF- β1 induced valvular interstitial cell differentiation. VICs, as the most common cell type in cardiac valves, contribute to valvular remodeling via a variety of mechanisms. In physiological condition, VIC perform a normal valvular repertoire and homeostasis function. However, during pathological condition, VICs can differentiate into myofibroblast in response to TGF-β1 resulting in valvular fibrosis, calcification, and stenosis [

23,

24,

25].

Fibroblast proliferation and differentiation is a key mechanism in fibrogenesis. The expression of

-SMA indicates the transition from valvular interstitial cells to myofibroblasts, followed by excessive production of inflammatory mediators, growth factors, and synthesis of extracellular matrix of collagen and fibronectin [

27]. A number of research [

27,

28,

29,

30] have found that statins reduce left ventricular hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis in hypertension and coronary artery disease. However, statin benefits in valvular interstitial cell fibrosis models has remained elusive [

31].

A growing amount of data suggests that atorvastatin stimulates PPAR-γ via a p38-MAPK pathway by inducing synthesis of 15-deoxy-delta-12,14-PGJ2 (15DPGJ2), an endogenous PPAR-γ ligand [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Angiotensin II activation via AT1R directly stimulates immune cells via NF-κB activation, resulting in the overexpression of various inflammatory mediators such as MCP-1, RANTES, IL-6, ICAM1, and VCAM1 [

36]. These findings have led the investigation of several angiotensin II pathway inhibitors and blockers, including as ACE and AT1R, in animals and other experimental models. An earlier studies revealed that a large dose of angiotensin II causes aortic valve leaflet thickening, endothelial lining discontinuities, and an increase in myofibroblasts in the ApoE-/- animal model of atherosclerosis and olmesartan, an AT1R blocker, administration attenuate these process [

37]. Olmesartan has also been demonstrated to diminish macrophage accumulation, osteopontin and ACE overexpression, and decrement in myofibroblasts differentiation in hyper cholesterol fed rabbit's aortic valves [

38,

39].

Resveratrol (RES; trans-3,4′,5-trihydroxystilbene), a phytoalexin abundant in grape skins, has been recognized as a bioactive element in red wine, has been widely studied for its antifibrosis effect [

40]. Study by Olson et al. showed the dual action of resveratrol in inhibiting fibrosis by direct inhibition of MEK activation and attenuation of ERK1/2 signalling and inhibition angiotensin II induced phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase (PI3-kinase)/Akt pathway [

41]. Our findings of resveratrol potency also supported similar with study by Zhang Y et al. In their study resveratrol decreased the levels of miR-17, miR-34a, and miR-181a in TGF-β1-treated CFs. Smad7 mRNA and protein levels were reduced when miR-17 was overexpressed, but elevated when miR-17 was silenced. Furthermore, inhibiting miR-17 or overexpression of Smad7 reduced TGF-β1-induced CF proliferation and collagen secretion [

42].

In current study the combination of atorvastatin, olmesartan, and resveratrol exhibit the most potent inhibition of myofibroblast differentiation. These combination was selectively selected due to their mechanism of inhibiting myofibrobast differentiation at various stages. Atorvastatin inhibit in distal signalling pathway of SMAD and MAPK. Olmesartan act as competitive inhibitor of angiotensin II at ATII type I receptor and inhibit downstream Ras and JAK/STAT signalling. Resveratrol increased PPAR levels and act as inhibitor and negative regulator to TNFα, IL-1, and NF-κB signalling pathway.

Limitations

There are various limitations to this study. One of them is the inability of comparing in vivo and in vitro cells since there are various cell phenotypic and behavior after separation from the organism, including the response to pharmacological stimulation. Although rabbit is the closest phylogenetic relative to humans (next to primates), it was unknown whether cells triggered with TGF β1 in the rabbit heart would trigger the same protein phosphorylation as human [

20].

5. Conclusions

These data suggest that atorvastatin, olmesartan, and resveratrol are likely exerting beneficial effects in inhibit pathological myofibroblast differentiation of valvular interstitial cell in experimental heart valve model by interacting with multiple signalling pathways.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L. and D.S.; methodology, B.B.D and R.A.N.; software, O.S.; validation, A.L., D.S. and R.A.N.; formal analysis, D.S. and R.A.N. ; investigation, D.S.; resources, D.S.; data curation, D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.H.O and A.S..; visualization, O.S.; supervision, A.S. and Y.H.O. ; project administration, D.S. and D.A.R..; funding acquisition, A.L. and Y.H.O.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research was funded by UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA, grant number 205/UN3/PT/2021. Funder has no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, all procedures comply with the ARRIVE guidelines and carried out in accordance with the laws, regulations, and administrative provisions of the U.K. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986 and associated guidelines, EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments, and the Law of Republic Indonesia Number 18 Year 2009 and Chapter 66 Law of Republic Indonesia Number 18 Year 2009 regarding the protection of animals for experimental and other scientific purposes. This research is approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ethical Committee for Animal Experiments at the Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia (Protocol Number: No.76/EC/KEPK/FKUA, date of approval 8 April 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Purwati and all staffs from Stem Cell Laboratory, Institute of Tropical Disease, Universitas Airlangga for their support resources, technical tips, and troubleshooting help related to culturing and passaging of the valvular interstitial cell.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dass C, Kanmanthareddy A. Rheumatic Heart Disease. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Rutkovskiy A, Malashicheva A, Sullivan G, Bogdanova M, Kostareva A, Stensløkken KO, et al. Valve interstitial cells: The key to understanding the pathophysiology of heart valve calcification. J Am Heart Assoc 2017. [CrossRef]

- Khan R, Sheppard R. Fibrosis in heart disease: Understanding the role of transforming growth factor-β1 in cardiomyopathy, valvular disease and arrhythmia. Immunology 2006. [CrossRef]

- Nelwan SC, Nugraha RA, Endaryanto A, Retno I. Modulating toll-like receptor-mediated inflammatory responses following exposure of whole cell and lipopolysaccharide component from Porphyromonas gingivalis in Wistar rat models. Eur J Dent 2017;11. [CrossRef]

- Wynn, TA. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol 2008. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du Y, Xiao H, Wan J, Wang X, Li T, Zheng S, et al. Atorvastatin attenuates TGF-β1-induced fibrogenesis by inhibiting Smad3 and MAPK signaling in human ventricular fibroblasts. Int J Mol Med 2020. [CrossRef]

- Eghbali M, Tomek R, Woods C, Bhambi B. Cardiac fibroblasts are predisposed to convert into myocyte phenotype: specific effect of transforming growth factor beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1991;88:795–9. [CrossRef]

- Schmierer B, Hill CS. TGFβ-SMAD signal transduction: Molecular specificity and functional flexibility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007. [CrossRef]

- Massagué J, Attisano L, Wrana JL. The TGF-β family and its composite receptors. Trends Cell Biol 1994. [CrossRef]

- Shi Y, Massagué J. Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell 2003. [CrossRef]

- Hayashida T, Decaestecker M, Schnaper HW. Cross-talk between ERK MAP kinase and Smad signaling pathways enhances TGF-beta-dependent responses in human mesangial cells. FASEB J 2003. [CrossRef]

- Nakao A, Afrakhte M, Morén A, Nakayama T, Christian JL, Heuchef R, et al. Identification of Smad7, a TGFβ-inducible antagonist of TGF-β signalling. Nature 1997. [CrossRef]

- Peng H, Carretero OA, Peterson EL, Rhaleb NE. Ac-SDKP inhibits transforming growth factor-β1-induced differentiation of human cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Am J Physiol - Hear Circ Physiol 2010. [CrossRef]

- Cucoranu I, Clempus R, Dikalova A, Phelan PJ, Ariyan S, Dikalov S, et al. NAD(P)H oxidase 4 mediates transforming growth factor-β1-induced differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Circ Res 2005;97:900–7. [CrossRef]

- Pardali E, ten Dijke P. TGFβ signaling and cardiovascular diseases. Int J Biol Sci 2012. [CrossRef]

- Chung CC, Kao YH, Yao CJ, Lin YK, Chen YJ. A comparison of left and right atrial fibroblasts reveals different collagen production activity and stress-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling in rats. Acta Physiol 2017. [CrossRef]

- Molkentin JD, Bugg D, Ghearing N, Dorn LE, Kim P, Sargent MA, et al. Fibroblast-Specific Genetic Manipulation of p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase in Vivo Reveals Its Central Regulatory Role in Fibrosis. Circulation 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010) Improving Bioscience Research Reporting: The ARRIVE Guidelines for Reporting Animal Research. PLoS Biol 8(6): e1000412.

- Kurikawa N, Suga M, Kuroda S, Yamada K, Ishikawa H. An angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist, olmesartan medoxomil, improves experimental liver fibrosis by suppression of proliferation and collagen synthesis in activated hepatic stellate cells. Br J Pharmacol 2003. [CrossRef]

- Lin C, Zhu D, Markby G, Corcoran BM, Farquharson C, Macrae VE. Isolation and characterization of primary rat valve interstitial cells: A new model to study aortic valve calcification. J Vis Exp 2017. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Cui W, Zhang HL, Hu HJ, Zhang YN, Liu DM, et al. Atorvastatin suppresses aldosterone-induced neonatal rat cardiac fibroblast proliferation by inhibiting ERK1/2 in the genomic pathway. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2013;61:520–7. [CrossRef]

- Zhou J, Jiang K, Ding X, Fu M, Wang S, Zhu L, et al. Qiliqiangxin inhibits angiotensin II-induced transdifferentiation of rat cardiac fibroblasts through suppressing interleukin-6. J Cell Mol Med 2015. [CrossRef]

- Weiss RM, Miller JD, Heistad DD. Fibrocalcific aortic valve disease: Opportunity to understand disease mechanisms using mouse models. Circ Res 2013. [CrossRef]

- Lee SH, Choi J-H. Involvement of Immune Cell Network in Aortic Valve Stenosis: Communication between Valvular Interstitial Cells and Immune Cells. Immune Netw 2016;16:26. [CrossRef]

- Wang D, Zeng Q, Song R, Ao L, Fullerton DA, Meng X. Ligation of ICAM-1 on human aortic valve interstitial cells induces the osteogenic response: A critical role of the Notch1-NF-κB pathway in BMP-2 expression. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Cell Res 2014. [CrossRef]

- Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Galli A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast: One function, multiple origins. Am J Pathol 2007. [CrossRef]

- Loch D, Levick S, Hoey A, Brown L. Rosuvastatin attenuates hypertension-induced cardiovascular remodeling without affecting blood pressure in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2006. [CrossRef]

- Saka M, Obata K, Ichihara S, Cheng XW, Kimata H, Nishizawa T, et al. Pitavastatin improves cardiac function and survival in association with suppression of the myocardial endothelin system in a rat model of hypertensive heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2006. [CrossRef]

- Ichihara S, Noda A, Nagata K, Obata K, Xu J, Ichihara G, et al. Pravastatin increases survival and suppresses an increase in myocardial matrix metalloproteinase activity in a rat model of heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 2006. [CrossRef]

- Oktaviono YH, Hutomo SA, Al-Farabi MJ, Chouw A, Sandra F. Human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cell-derived secretome in combination with atorvastatin enhances endothelial progenitor cells proliferation and migration. F1000Research 2021;9:1–23. [CrossRef]

- Zhao SP, Zhang DQ. Atorvastatin reduces interleukin-6 plasma concentration and adipocyte secretion of hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Clin Chim Acta 2003. [CrossRef]

- Francis GA, Annicotte JS, Auwerx J. PPAR agonists in the treatment of atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2003. [CrossRef]

- Ye Y, Nishi SP, Manickavasagam S, Lin Y, Huang MH, Perez-Polo JR, et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) by atorvastatin is mediated by 15-deoxy-delta-12,14-PGJ2. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 2007. [CrossRef]

- Zhang O, Zhang J. Atorvastatin promotes human monocyte differentiation toward alternative M2 macrophages through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ activation. Int Immunopharmacol 2015. [CrossRef]

- Yano M, Matsumura T, Senokuchi T, Ishii N, Murata Y, Taketa K, et al. Statins activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ through extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent cyclooxygenase-2 expression in macrophages. Circ Res 2007. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki Y, Ruiz-Ortega M, Lorenzo O, Ruperez M, Esteban V, Egido J. Inflammation and angiotensin II. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2003;35:881–900. [CrossRef]

- Fujisaka T, Hoshiga M, Hotchi J, Takeda Y, Jin D, Takai S, et al. Angiotensin II promotes aortic valve thickening independent of elevated blood pressure in apolipoprotein-E deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 2013. [CrossRef]

- Arishiro K, Hoshiga M, Negoro N, Jin D, Takai S, Miyazaki M, et al. Angiotensin Receptor-1 Blocker Inhibits Atherosclerotic Changes and Endothelial Disruption of the Aortic Valve in Hypercholesterolemic Rabbits. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007. [CrossRef]

- Agita A, Thaha M. Inflammation, Immunity, and Hypertension. Acta. Med. Indones. 2017; 49:158–165. Acta Med Indones 2017;49:158–65.

- Prakoeswa CRS, Rindiastuti Y, Wirohadidjojo YW, Komaratih E, Nurwasis, Dinaryati A, et al. Resveratrol promotes secretion of wound healing related growth factors of mesenchymal stem cells originated from adult and fetal tissues. Artif Cells, Nanomedicine Biotechnol 2020;48:1160–7. [CrossRef]

- Olson ER, Naugle JE, Zhang X, Bomser JA, Meszaros JG. Inhibition of cardiac fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation by resveratrol. Am J Physiol - Hear Circ Physiol 2005. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Lu Y, Ong’Achwa MJ, Ge L, Qian Y, Chen L, et al. Resveratrol Inhibits the TGF- β 1-Induced Proliferation of Cardiac Fibroblasts and Collagen Secretion by Downregulating miR-17 in Rat. Biomed Res Int 2018. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).