Submitted:

04 November 2023

Posted:

09 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Rural areas – facts and figures of the Alentejo

1.2. Why immigrants remain in adverse places?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Analysis

3. Results

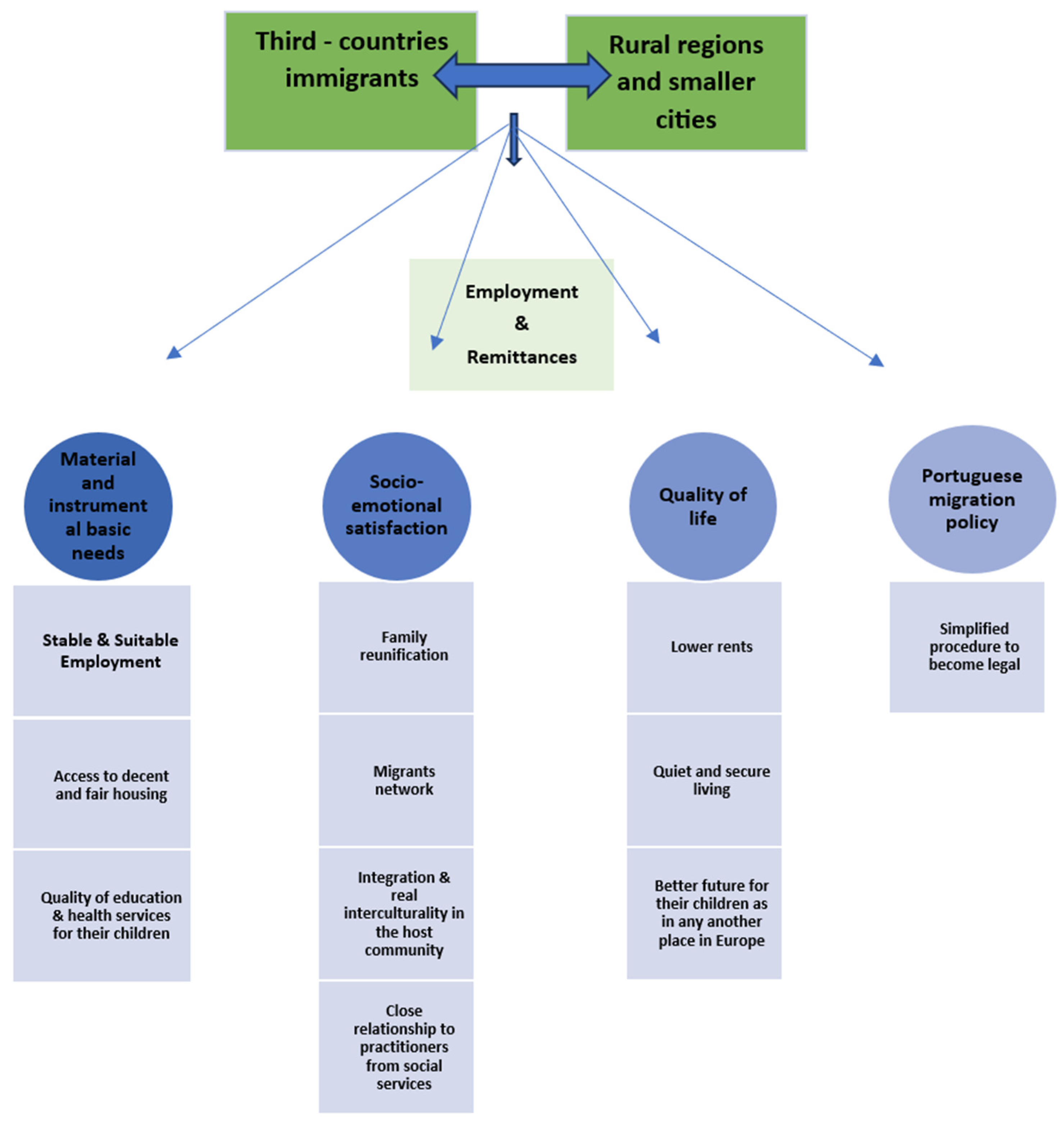

3.1. Motivations to stay long-term

3.1.1. Instrumental and material motivations

“While there is work, they [international immigrants] will continue here […] – In your opinion, what brings migrants to this specific region? – Jobs, job opportunities. They heard about a job opportunity.”[Practitioner CLAIM 1a]

“A lot of agriculture and therefore a lot of immigrants because of employment.”[Immigrant 9, Ukraine]

“they know that they can easily get a job here, in an orchard, it means, in the agricultural sector.”[Practitioner 3, municipality 2]

“there is also a shortage of manpower in other sectors beyond agriculture”[Practitioner 4, CLAIM 3]

“here they can also get jobs in hotels, construction industry, house cleaning…”[Practitioner 2, CLAIM 2]

“employment… In the hospital, we have doctors and nurses from Spain and from Brazil. They come to work here.”[Practitioner CLAIM 3]

“they work seasonally in the production of olives, and the they leave, then they come back, because there is the harvest of red fruits, and so on.”[Practitioner 2, municipality 1]

“if they cannot find a job, they leave… residual unemployed immigrants remain here. We know a family who are unemployed who are having family and friends support and our help, but the situation is becoming unbearable”.[Practitioner CLAIM 1a]

“here labour markets are not so demanding, and that is an advantage”[Immigrant 3, Brazil]

“Lisbon is a big city where employment can be gotten in civil construction or in companies where Portuguese speaking is needed. Thus, the only way to get a job is leaving Lisbon and therefore they come until here and then they stay, they remain here.”[Practitioner 4, CLAIM 3]

“in Lisbon [city], they need to speak Portuguese, the language is a problem. So, they come here to work [namely in agriculture] and then they remain.”[Practitioner 3, CLAIM 2]

“they say: if I don’t send money to my family, they don’t eat”[practitioner 4, CLAIM 3]

“they aim to work extra hours to earn more money and send it to their families”[practitioner 1, municipality 1]

“- […] not sure what could root them here, perhaps housing issues.”[Practitioner 1, municipality 1]

“there are 3 or 4 families in a 3 bedroomed house in order to share costs”[Practitioner 1, CLAIM 1]

“it is a house that even has housing license […] it was a restaurant”[Practitioner 1, municipality 1]

“here there are few conditions on housing. Houses are not furnished or are in the historic center and very damp and deprived... they rent it. They submitted themselves to those conditions […] they ask us for beds and even mattresses therefore they are sleep on the floor.”[Practitioner 3, CLAIM 2]

“the vast majority work on farms, a lot of them stay on the farm”[Practitioner 1, municipality 1]

“there is an airport, but it doesn’t operate, there is a train, but it doesn’t operate. Thus, while there isn’t an improvement in the infrastructure in the region, the municipalities are hampered.”[Practitioner 1, municipality 1]

“[…] municipal houses are occupied, therefore if there was a political investment to rebuild other houses… because there are a lot of empty old houses here, a lot of uninhabited houses […]”[Practitioner 4, CLAIM 3]

“it is possible to have family, to give education to your children, it’s possible to give it… there are health, hospitals, a good hospital, and the local health center is good as well. And schools…, there are good schools, even good universities here.”[Immigrant 5, Brazil]

“she said: I want to give my children an European education. I want my children to access health. I want them to have educational opportunities that I could never give in my home country”[Practitioner 4, CLAIM 3]

3.1.2. Emotional and social motivations

“they want to root here, bring their family, bring their wives and children who remain in the country of origin. Sometimes they bring them in dribs and drabs, now comes the wife, then one son. They come to work and later bring their families.”[Practitioner 3, CLAIM 2]

“there was a link to the local community and if there is an opportunity, they go there. That’s called integration!”[Practitioner 4, municipality 2]

“once arrived, they get to know the municipality and services, where to ask for responses. Our capacity of welcoming makes them want to stay. And then, relationships… they build their relationships as all of us, and… establish a connection to people.”[Practitioner 4, CLAIM 3]

“we work close to them, and become a reference for them, someone who they can trust. From then on, they always come here, ‘cause they know if the topic is not up to us, we refer them to the suitable service!”[Practitioner 3, municipality 2]

“immigrants once here, want to be illegal, so, if an organization exists to support them, well…[even better]. They will want to stay, and of course if they get a job!”[Immigrant 1, Guinea Bissau]

“the household pull friends. And if there is employment, they stay.”[Immigrant 3, Brazil]

“a person who comes here, is following another one.”[Immigrant 6, Brazil]

3.1.3. Motivations based on quality of life

“They stay because of the quality of life”[practitioner 2, CLAIM 2]

“I walk on the street fearless […] security, any hour night and day.”[Immigrant 10, Cape Verde]

“They tell me that after his son-in-low had been murdered on a street, it was impossible to keep living in Brazil.”[Practitioner 4, CLAIM 3]

“I was invited by my sisters to leave and move to Lisbon. I reflected on the pros and cons because of the rental costs...”[Immigrant 7, São Tomé e Príncipe]

“here is very quiet and life is pretty cheap”[Immigrant 13, Guinea Bissau]

“So, you become friends, within a calm way of life.”[Immigrant 11, Brazil]

“here is a calm place and with generous local inhabitants… the kindness that we get here… international students wouldn’t receive it in all places.”[Immigrant 13, Guinea Bissau]

3.1.4. Motivations base on political dimension

“the regularization procedure is faster. And even if they wait for three or four years, they know that they will get the document. Third country nationals since the law amendment may enter in Portugal lacking proof of legal entrance.”[Practitioner 3, municipality 2]

“the regularization procedure in Portugal is very… let’s say, more simple, less complex than in Italy, Spain or Germany.”.[Practitioner 3, municipality 2].

“I always tell an immigrant: if you want to live here, the first thing to do is have babies. Having a baby born in Portugal they may request authorization for residence by the child”[Practitioner 1, CLAIM 1]

“[immigration and boarder service] here addressed half a dozen immigrants per week and now it is half a dozen per day. […] 90%, almost 100% of the service users are from abroad.”[Practitioner 2, CLAIM 2]

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zang, Y., Yang, Y., Liu, Y. Understanding rural system with a social-ecological framework: Evaluating sustainability of rural evolution in Jiangsu province, South China. Journal of Rural Studies. Volume 86. pp. 171-180. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mota, B. A Problemática dos Territórios de Baixa Densidade: Quatro Estudos de Caso. Master’s Degree Thesis. ISCTE-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa. 2019. https://repositorio.iscte-iul.pt/bitstream/10071/19336/1/master_bruno_mendes_mota.pdf.

- Carvalho, C. and Oliveira, C. Uma leitura de género sobre mobilidades e acessibilidades em meio rural. Cidades, Comunidades e Territórios, 35, pp. 129 – 146. 2017. https://journals.openedition.org/cidades/599.

- ESPON. Transnational Observation - Fighting rural depopulation in Southern Europe. ESPON EGTC: Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Mota 20192018. https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/af-espon_spain_02052018-en.pdf.

- Deliberação n.o 55/2015, of the 1st of July 2015.

- Peixoto, J. As Teorias Explicativas das Migrações: Teorias Micro e Macrossociológicas. SOCIUS Working Papers. N.o 11/2004. Instituto Superior de Economia e Gestão – Universidade Técnica de Lisboa. 2004. https://www.repository.utl.pt/handle/10400.5/2037.

- Lumley, S. & Armstrong, P. Some of the Nineteenth Century Origins of the Sustainability Concept. Environment, Development and Sustainability. 6: 367–378. 2003. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1023/B:ENVI.0000029901.02470.a7.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Góis, P. Ainda entre periferias e um centro: o lugar de Portugal no sistema migratório global. In E. Diogo & M. Raquel (eds.). Práticas e Políticas – Inspiradoras e Inovadoras com Imigrantes. pp. 29–40. 2022. Edições Esgotadas.

- Collantes, F., Pinilla, V., Sáez, L. A., Silvestre, J. Reducing depopulation in rural Spain: The impact of immigration. Population, Space and Place, 20[7], 606–621. 2013. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257413128_Reducing_Depopulation_in_Rural_Spain_The_Impact_of_Immigration.

- Gauci, J.P. Integration of migrants in middle and small cities and in rural areas in Europe. Commission for Citizenship, Governance, Institutional and External Affairs. European Union. 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/library-document/integration-migrants-middle-and-small-cities-and-rural-areas-europe_en.

- Morén-Alegret, R., Milazzo, J., Romagosa, F., Kallis, G. ‘Cosmovillagers’ as Sustainable Rural Development Actors in Mountain Hamlets? International Immigrant Entrepreneurs’ Perceptions of Sustainability in the Lleida Pyrenees [Catalonia, Spain]. European Countryside. Vol. 13, No. 2. pp. 267-296. 2021. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353200362_’Cosmovillagers’_as_Sustainable_Rural_Development_Actors_in_Mountain_Hamlets_International_Immigrant_Entrepreneurs’_Perceptions_of_Sustainability_in_the_Lleida_Pyrenees_Catalonia_Spain.

- Pordata. Censos de Portugal em 2021 – por tema e concelho. 2023. https://www.pordata.pt/censos/resultados/populacao-alentejo-592.

- European Commission - Eurostat. Rural Development. 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/rural-development/methodology.

- INE – Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Dinâmicas territoriais. 2023a. https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_publicacoes&PUBLICACOESpub_boui=66320870&PUBLICACOESmodo=2.

- Mauritti, R., Nunes, N., Alves, J., Diogo, F. Desigualdades sociais e desenvolvimento em Portugal: um olhar à escala regional e aos territórios de baixa densidade. Sociologia Online. 2019. https://revista.aps.pt/pt/social-inequalities-and-development-in-portugal-2/. [CrossRef]

- INE – Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Estatísticas demográficas. 2023b. https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&userLoadSave=Load&userTableOrder=9956&tipoSeleccao=1&contexto=pq&selTab=tab1&submitLoad=true.

- Sistema de Segurança Interna. Relatório Anual de Segurança Interna. 2022. https://www.portugal.gov.pt/download-ficheiros/ficheiro.aspx?v=%3D%3DBQAAAB%2BLCAAAAAAABAAzNDazMAQAhxRa3gUAAAA%3D.

- SEF/ GEPF – Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras/ Gabinete de Estudos, Planeamento e Formação. Relatório de Imigração, Fronteiras e Asilo 2022. 2023. https://www.sef.pt/pt/Documents/RIFA2021%20vfin2.pdf.

- Pordata. Saldos populacionais anuais: total, natural e migratório. 2021. https://www.pordata.pt/Portugal/Saldos+populacionais+anuais+total++natural+e+migrat%C3%B3rio-657.

- Oliveira, C.R. [eds.]. Indicadores de Integração de Imigrantes - Relatório Estatístico Anual 2023. Coleção Imigração em Números do Observatório das Migrações: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. https://www.om.acm.gov.pt/documents/58428/383402/Relatorio+Estatistico+Anual+-+Indicadores+de+Integracao+de+Imigrantes+2022.pdf/eccd6a1b-5860-4ac4-b0ad-a391e69c3bed.

- Pordata. População estrangeira com estatuto legal de residente: total e por algumas nacionalidades. 2022. https://www.pordata.pt/db/municipios/ambiente+de+consulta/tabela.

- Sampedro, R.; Camarero, L. Foreign Immigrants in Depopulated Rural Areas: Local Social Services and the Construction of Welcoming Communities. Social Inclusion. Vol. 6, Issue 3, 337–346. 2018. https://www.cogitatiopress.com/socialinclusion/article/view/1530. [CrossRef]

- Natale, F., Kalantaryan, S., Scipioni, M., Alessandrini, A. and Pasa, A. Migration in EU Rural Areas. Publications Office of the European Union. 2019. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC116919.

- Flynn, M.; Kay, R. Migrants’ experiences of material and emotional security in rural Scotland: implications for longer-term settlement. Journal of Rural Studies, 52, 56–65. 2017. https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S0743016716302054?token=A5FCD9E83DABF438BD9E18F9A74261C8AD332AB9D4639B8FEBC068912A2DEA7B6599271FE75BDDF18551E065CFDEE877&originRegion=eu-west-1&originCreation=20221229140006.

- Valdez, C., Valentine, J., Padilla, B. “Why we stay”: immigrants’ motivations for remaining in communities impacted by anti-immigration policy. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 279–287. 2013. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3721425/.

- Chavez L. The power of the imagined community: The settlement of undocumented Mexicans and Central Americans in the United States. American Anthropologist. 96[1], 52–73. 1994. [CrossRef]

- Manakou, A. The phenomenon of rural depopulation in the Swedish landscape Turning the trends. Master’s Degree Thesis. Blekinge Institute of Technology Karlskrona Sweden. 2018. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1212891/FULLTEXT02.pdf.

- Blaikie, N. [2nd ed.]. Designing Social Research. Polity Press. 2010.

- Flick, U. Métodos Qualitativos na Investigação Científica. Monitor. 2005.

- Flick, U. Introdução à Metodologia de Pesquisa. Penso. 2013.

- Braun, V., and Victoria, C. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 [2]. pp. 77-101. 2006. http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~db=all~content=a795127197~frm=titlelink.

- European Commission. Action plan on the integration and inclusion. 2020. https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/migration-and-asylum/legal-migration-and-integration/integration/action-plan-integration-and-inclusion_en.

| [1] | In this paper terms migrant/ immigrant/migration are used to refer to third country nationals (TCN) people, that is any person who is not a citizen of the European Union within the meaning of Art. 20(1) of The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union – Consolidated Version of. Official Journal of the European Union. 2012. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT&from=EN. And therefore, it may include a person with or without residence permission. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).