Submitted:

07 November 2023

Posted:

08 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

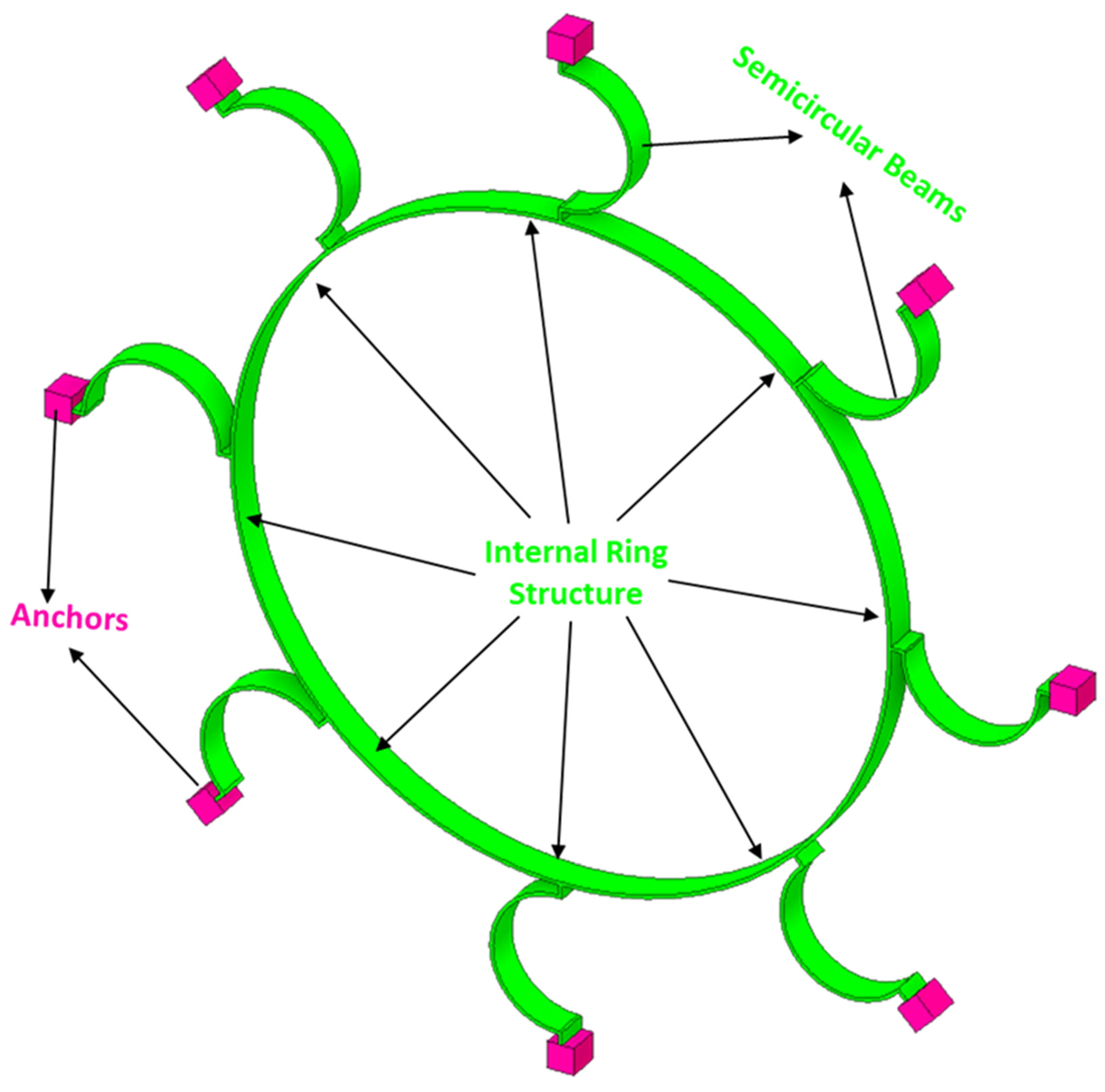

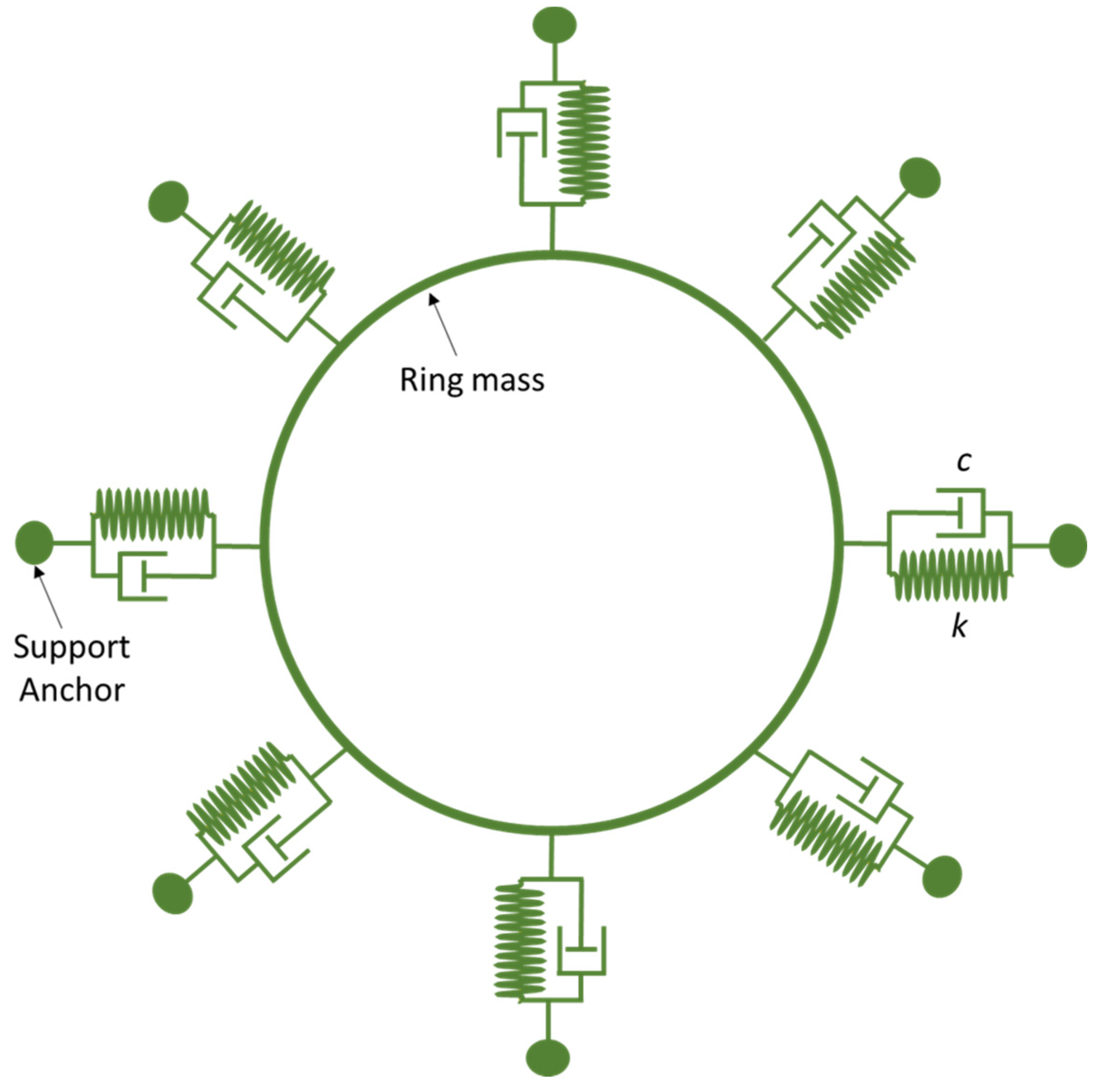

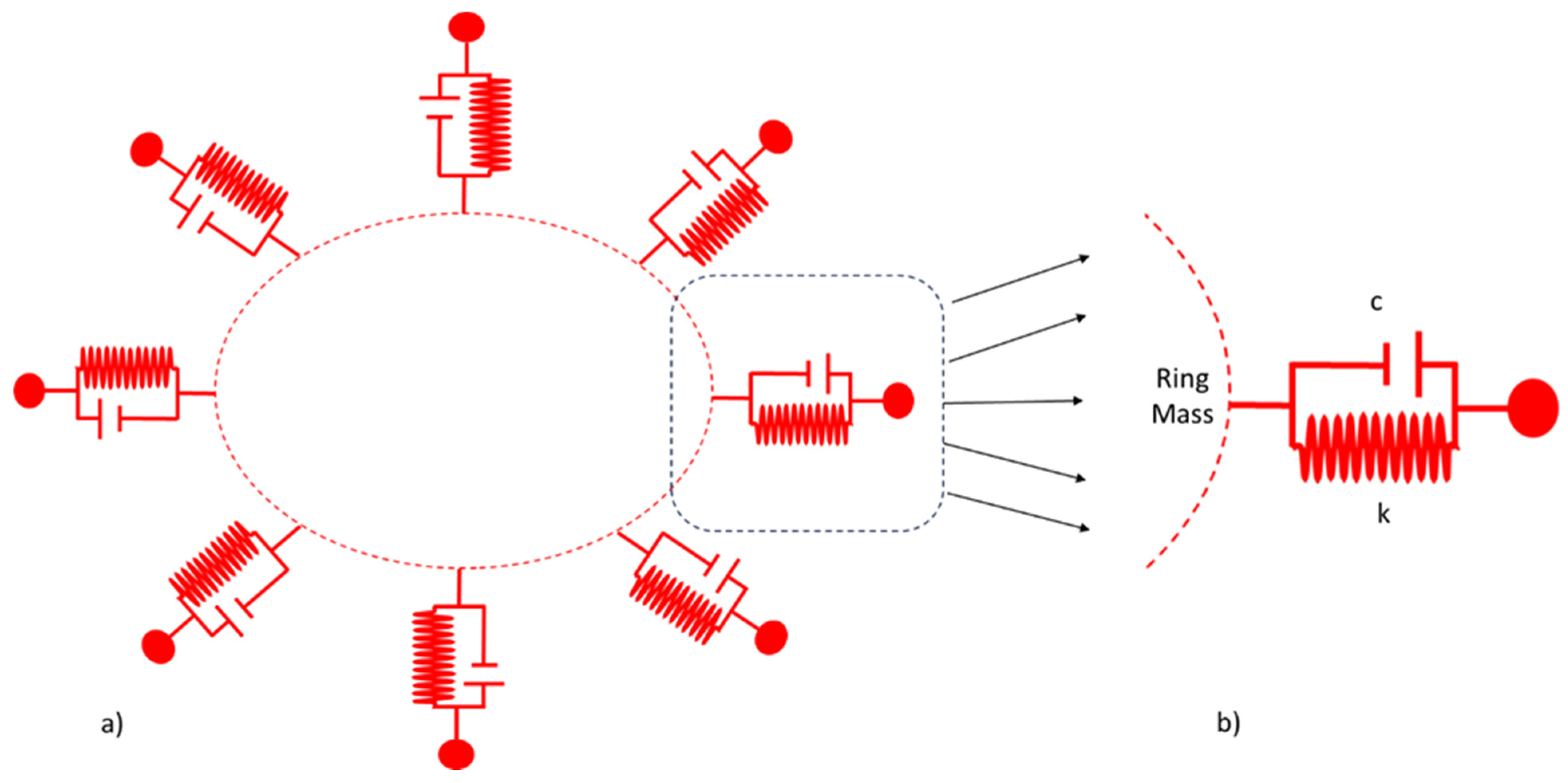

2. Dynamics of MEMS Vibrating Ring Gyroscope

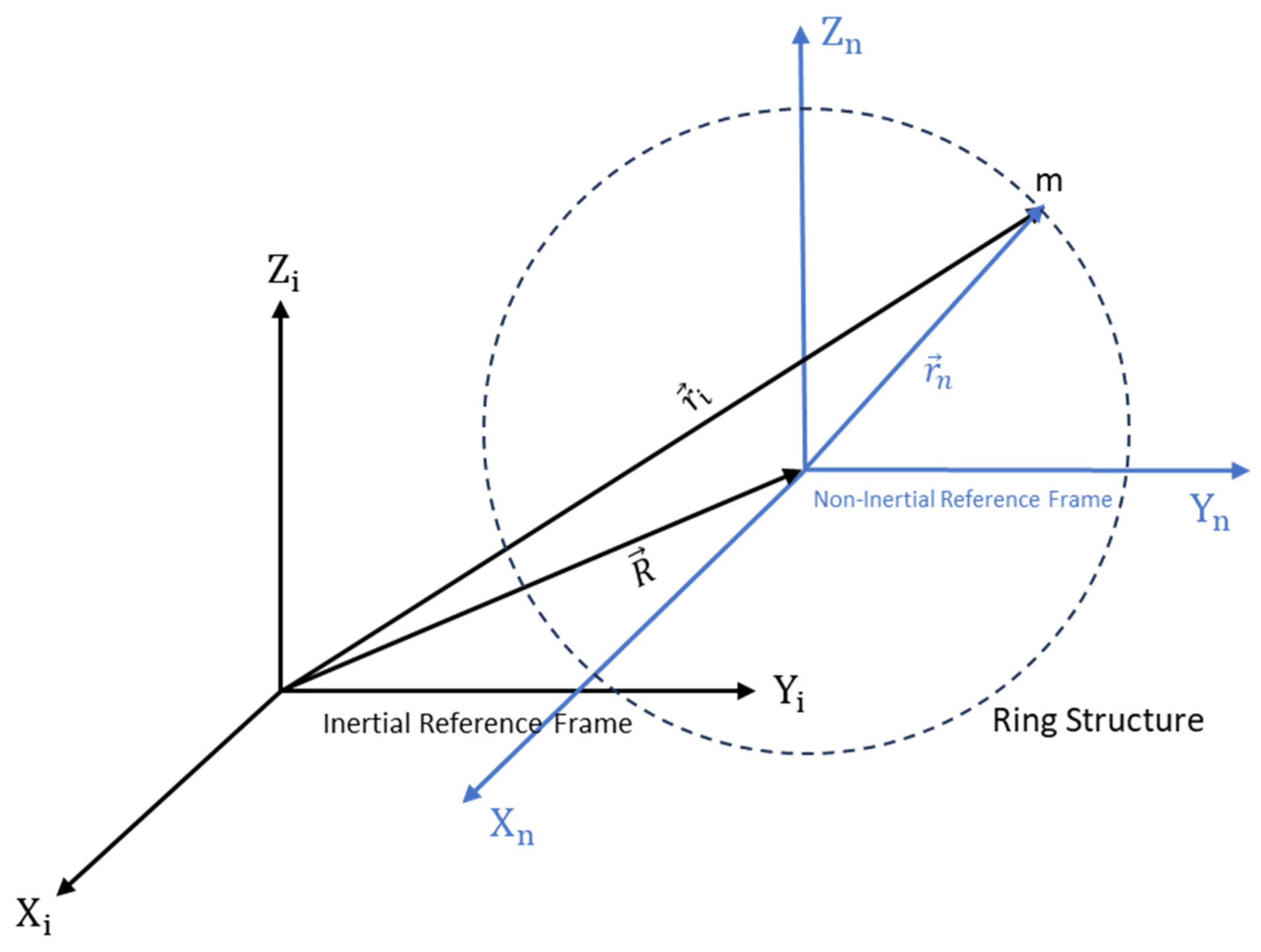

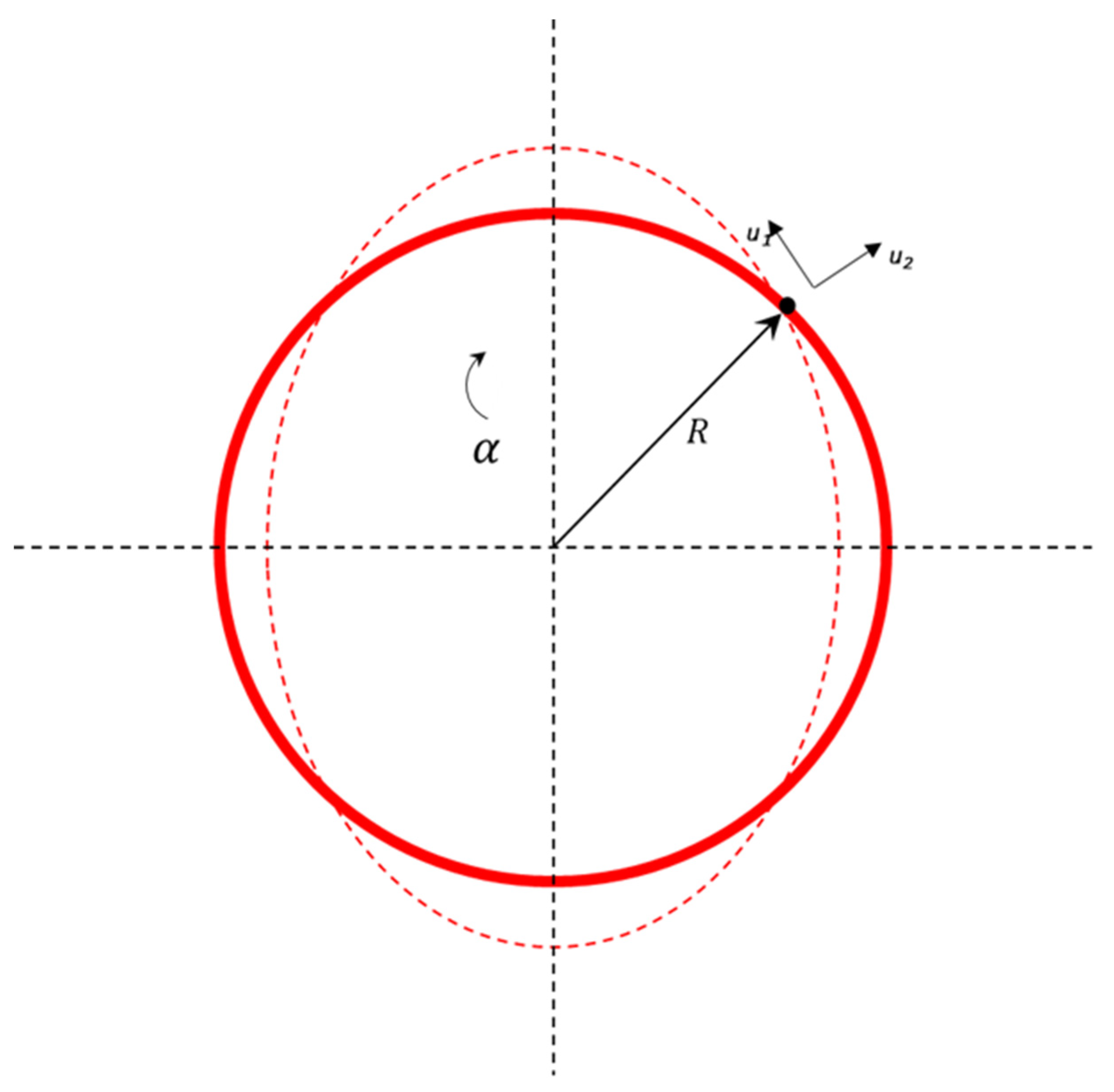

2.1. Reference Frames

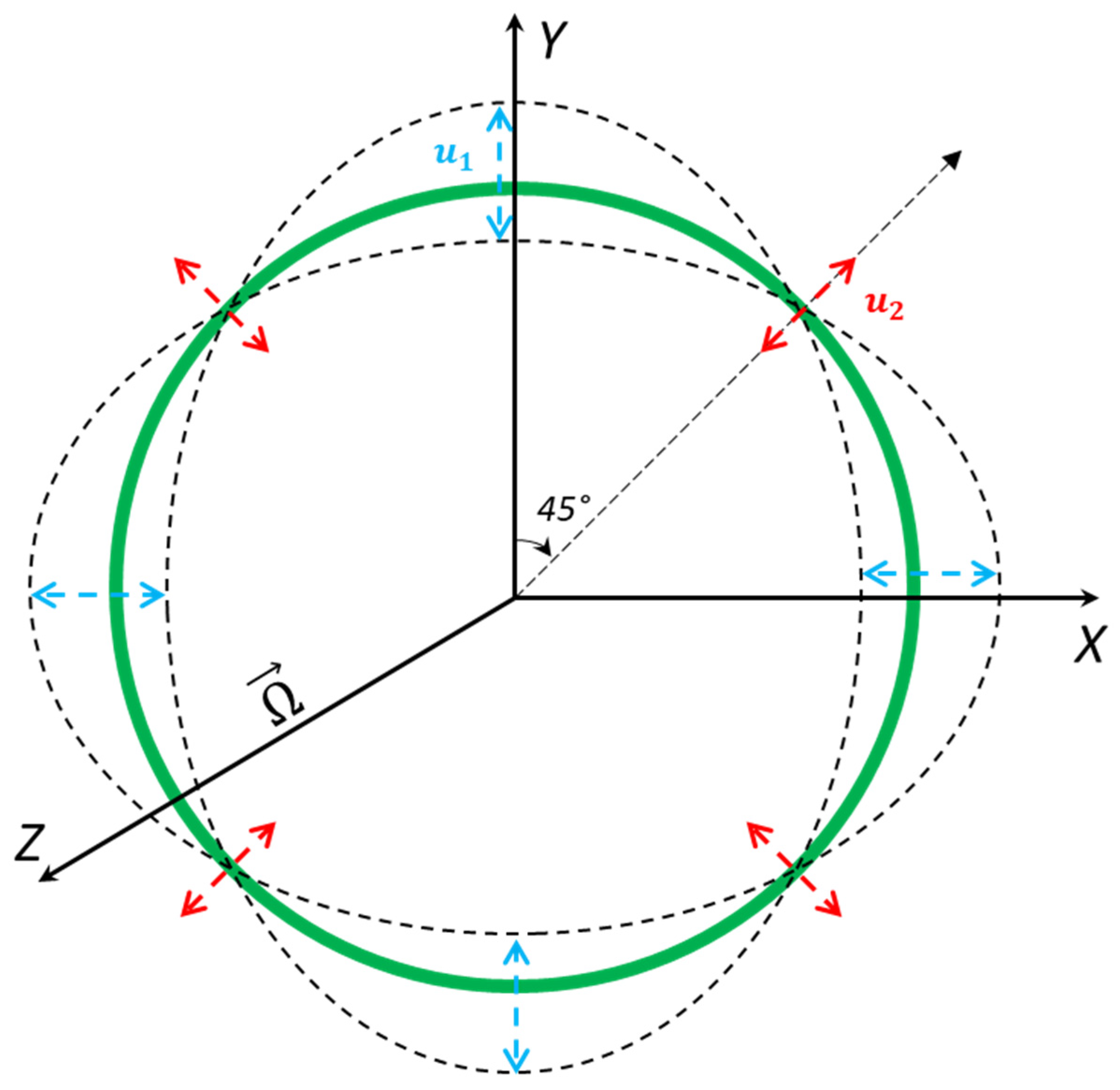

2.2. Motion Equations of Vibrating Ring Gyroscope

2.2.1. Coordinates for Vibrating Ring Gyroscope

2.2.2. Various Energies Effect

- Kinetic Energy

- Elastic Strain Energy

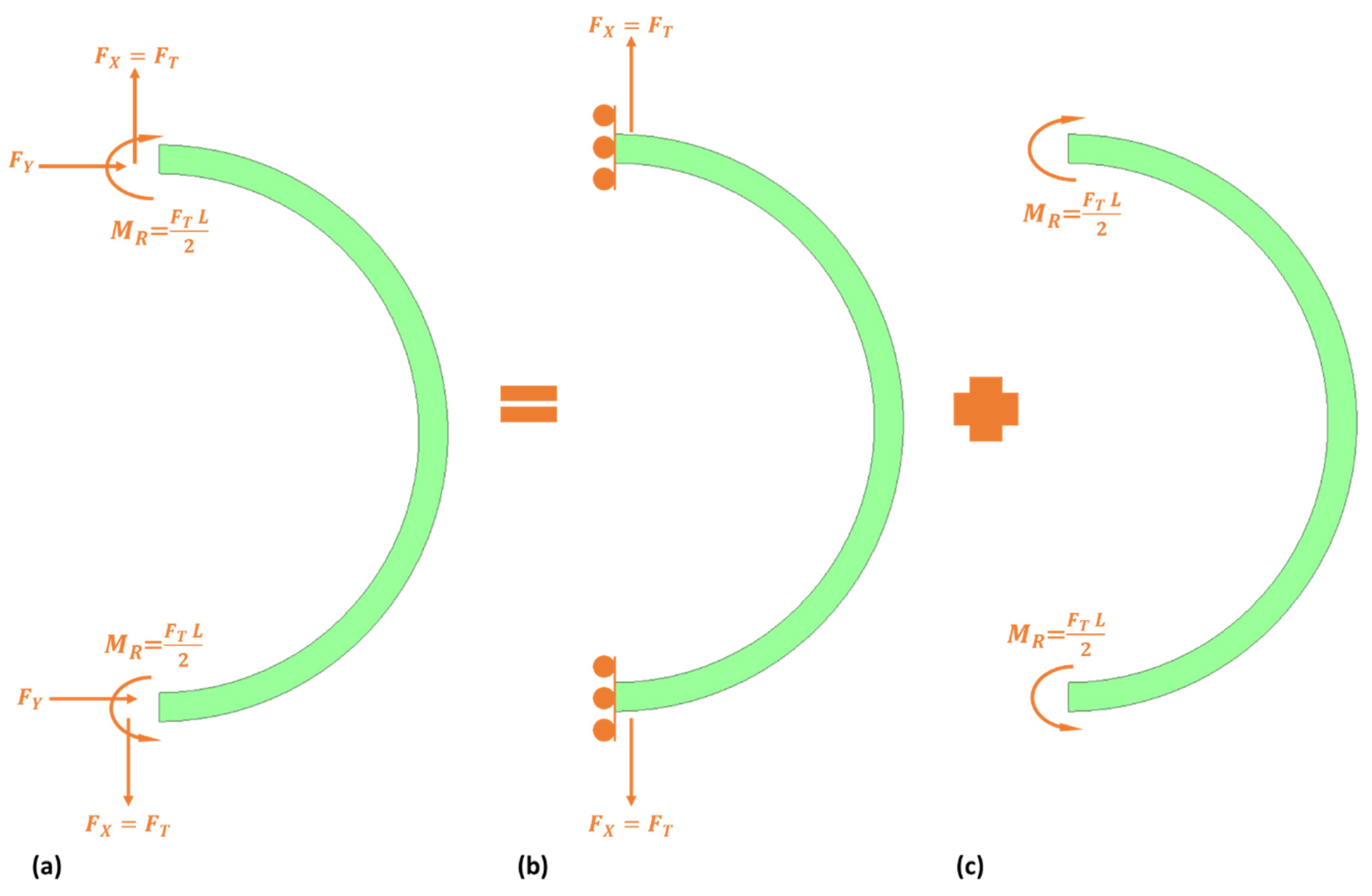

- Strain Energy of Semicircular beams

- Damping Energy

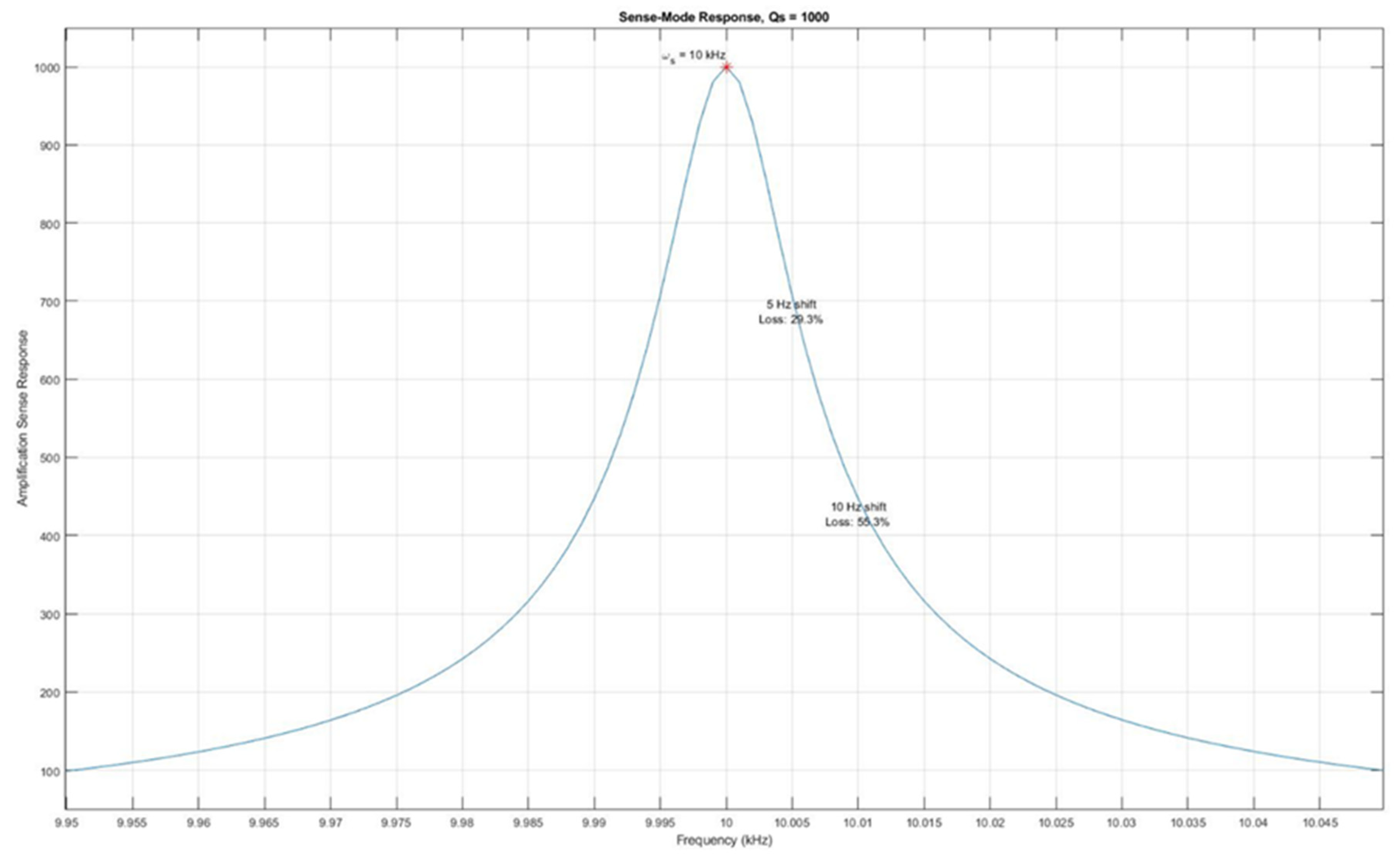

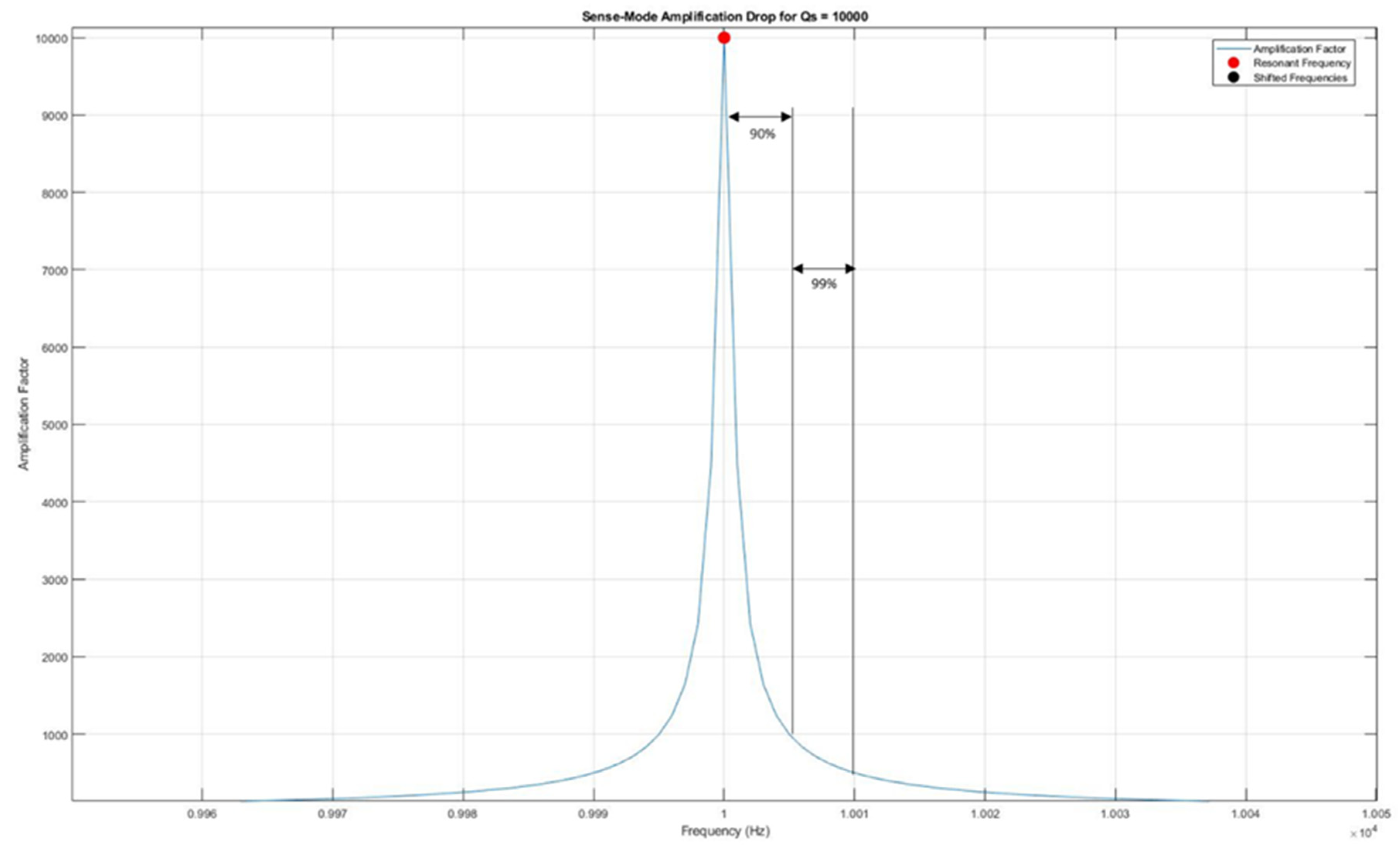

2.3. Implication of Resonance Analysis on MEMS Vibrating Ring Gyroscope Design

2.4. Mode Matching in Vibrating Ring Gyroscopes

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jia J, Ding X, Qin Z, Ruan Z, Li W, Liu X, et al. Overview and analysis of MEMS Coriolis vibratory ring gyroscope. Measurement. 2021;182:109704. [CrossRef]

- Wu X, Xi X, Wu Y, Xiao D. Cylindrical Vibratory Gyroscope: Springer; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Acar C, Shkel A. MEMS vibratory gyroscopes: structural approaches to improve robustness: Springer Science & Business Media; 2008. [CrossRef]

- Apostolyuk V. Theory and design of micromechanical vibratory gyroscopes. MEMS/NEMS: Handbook Techniques and Applications: Springer; 2006. p. 173-95. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Gao S, Jin L, Liu H, Niu S. Micromachined vibrating ring gyroscope architecture with high-linearity, low quadrature error and improved mode ordering. Sensors. 2020;20(15):4327. [CrossRef]

- Kou Z, Cui X, Cao H, Li B, editors. Analysis and Study of a MEMS Vibrating Ring Gyroscope with High Sensitivity. 2020 IEEE 5th Information Technology and Mechatronics Engineering Conference (ITOEC); 2020. Chongqing, China: IEEE.

- Syed WU, An BH, Gill WA, Saeed N, Al-Shaibah M, Al Dahmani S, et al. Sensor Design Migration: The Case of a VRG. IEEE Sensors J. 2019;19(22):10336-46. [CrossRef]

- Xia D, Yu C, Kong L. The development of micromachined gyroscope structure and circuitry technology. Sensors. 2014;14(1):1394-473. [CrossRef]

- Passaro VMN, Cuccovillo A, Vaiani L, De Carlo M, Campanella CE. Gyroscope Technology and Applications: A Review in the Industrial Perspective. Sensors. 2017;17(10):2284. [CrossRef]

- Lee JS, An BH, Mansouri M, Yassi HA, Taha I, Gill WA, et al. MEMS vibrating wheel on gimbal gyroscope with high scale factor. Microsyst Technol. 2019;25:4645-50. [CrossRef]

- Liang F, Liang D-D, Qian Y-J. Dynamical analysis of an improved MEMS ring gyroscope encircled by piezoelectric film. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences. 2020;187:105915. [CrossRef]

- Gill WA, Howard I, Mazhar I, McKee K. A Review of MEMS Vibrating Gyroscopes and Their Reliability Issues in Harsh Environments. Sensors. 2022;22(19):7405. [CrossRef]

- Liang F, Liang D-D, Qian Y-J. Nonlinear Performance of MEMS Vibratory Ring Gyroscope. Acta Mechanica Solida Sinica. 2021;34(1):65-78. [CrossRef]

- Gill WA, Ali D, An BH, Syed WU, Saeed N, Al-shaibah M, et al. MEMS multi-vibrating ring gyroscope for space applications. Microsyst Technol. 2020;26:2527-33. [CrossRef]

- Cao H, Liu Y, Kou Z, Zhang Y, Shao X, Gao J, et al. Design, fabrication and experiment of double U-beam MEMS vibration ring gyroscope. Micromachines. 2019;10(3):186. [CrossRef]

- Kou Z, Liu J, Cao H, Shi Y, Ren J, Zhang Y. A novel MEMS S-springs vibrating ring gyroscope with atmosphere package. AIP Advances. 2017;7(12). [CrossRef]

- Yoon SW, Lee S, Najafi K. Vibration sensitivity analysis of MEMS vibratory ring gyroscopes. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical. 2011;171(2):163-77. [CrossRef]

- Kou Z, Liu J, Cao H, Han Z, Sun Y, Shi Y, et al. Investigation, modeling, and experiment of an MEMS S-springs vibrating ring gyroscope. Journal of Micro/Nanolithography, MEMS, and MOEMS. 2018;17(1):015001-. [CrossRef]

- Ayazi F, Najafi K, editors. Design and fabrication of high-performance polysilicon vibrating ring gyroscope. Proceedings MEMS 98 IEEE Eleventh Annual International Workshop on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems An Investigation of Micro Structures, Sensors, Actuators, Machines and Systems (Cat No 98CH36176; 1998: IEEE.

- Ayazi F, Hsiao H, Kocer F, He G, Najafi K, editors. A High Aspect-Ratio Polysilicon Vibrating Ring Gyroscope. Solid-State Sensor and Actuator Workshop; 2000. Hilton Head Island, South Carolina: IEEE.

- Shkel AM, Horowitz R, Seshia AA, Park S, Howe RT, editors. Dynamics and control of micromachined gyroscopes. Proceedings of the 1999 American Control Conference (Cat No 99CH36251); 1999: IEEE.

- He G, Najafi K, editors. A single-crystal silicon vibrating ring gyroscope. Technical Digest MEMS 2002 IEEE International Conference Fifteenth IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (Cat No 02CH37266); 2002: IEEE.

- Gallacher BJ, Hedley J, Burdess JS, Harris AJ, Rickard A, King DO. Electrostatic correction of structural imperfections present in a microring gyroscope. J Microelectromech Syst. 2005;14(2):221-34. [CrossRef]

- Liu K, Zhang W, Chen W, Li K, Dai F, Cui F, et al. The development of micro-gyroscope technology. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering. 2009;19(11):113001. [CrossRef]

- Gill WA, Howard I, Mazhar I, McKee K. Design and Considerations: Microelectromechanical System (MEMS) Vibrating Ring Resonator Gyroscopes. Designs. 2023;7(5):106. [CrossRef]

- Duwel A, Gorman J, Weinstein M, Borenstein J, Ward P. Experimental study of thermoelastic damping in MEMS gyros. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical. 2003;103(1-2):70-5. [CrossRef]

- Wong S, Fox C, McWilliam S. Thermoelastic damping of the in-plane vibration of thin silicon rings. Journal of Sound and Vibration. 2006;293(1-2):266-85. [CrossRef]

- Tsai D-H, Fang W. Design and simulation of a dual-axis sensing decoupled vibratory wheel gyroscope. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical. 2006;126(1):33-40. [CrossRef]

- Hyun An B, Gill WA, Lee JS, Han S, Chang HK, Chatterjee AN, et al. Micro-Electromechanical Vibrating Ring Gyroscope with Structural Mode-Matching in (100) Silicon. sens lett. 2018;16(7):548-51. [CrossRef]

- Zou X, Zhao C, Seshia AA, editors. Edge-anchored mode-matched micromachined gyroscopic disk resonator. 2017 19th International Conference on Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems (TRANSDUCERS); 2017: IEEE.

- Ahn CH, Ng EJ, Hong VA, Yang Y, Lee BJ, Flader I, et al. Mode-matching of wineglass mode disk resonator gyroscope in (100) single crystal silicon. 2014;24(2):343-50. [CrossRef]

- Fan B, Guo S, Cheng M, Yu L, Zhou M, Hu W, et al. Frequency symmetry comparison of cobweb-like disk resonator gyroscope with ring-like disk resonator gyroscope. IEEE Electron Device Letters. 2019;40(9):1515-8. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).